Abstract

Aims: We aimed to estimate the risk of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from various antifungal treatments with azoles and echinocandins causing in real-world practice.

Methods: We performed disproportionality and Bayesian analyses based on data from the first quarter in 2004 to the third quarter in 2021 in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System to characterize the signal differences of antifungal drugs-related DILI. We also compared the onset time and mortality differences of different antifungal agents.

Results: A total of 2943 antifungal drugs-related DILI were identified. Affected patients tended to be aged >45 years (51.38%), with more males than females (49.03% vs. 38.09%). Antifungal drug-induced liver injury is most commonly reported with voriconazole (32.45%), fluconazole (19.37%), and itraconazole (14.51%). Almost all antifungal drugs were shown to be associated with DILI under disproportionality and Bayesian analyses. The intraclass analysis of correlation between different antifungal agents and DILI showed the following ranking: caspofungin (ROR = 6.12; 95%CI: 5.36–6.98) > anidulafungin (5.15; 3.69–7.18) > itraconazole (5.06; 4.58–5.60) > voriconazole (4.58; 4.29–4.90) > micafungin (4.53; 3.89–5.27) > posaconazole (3.99; 3.47–4.59) > fluconazole (3.19; 2.93–3.47) > ketoconazole (2.28; 1.96–2.64). The onset time of DILI was significantly different among different antifungal drugs (p < 0.0001), and anidulafungin result in the highest mortality rate (50.00%), while ketoconazole has the lowest mortality rate (9.60%).

Conclusion: Based on the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System database, antifungal drugs are significantly associated with DILI, and itraconazole and voriconazole had the greatest risk of liver injury. Due to indication bias, more clinical studies are needed to confirm the safety of echinocandins.

Keywords: DILI, antifungal drugs, pharmacovigilance, adverse event reporting system, epidemiology

Introduction

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a common and serious adverse drug reaction, defined as liver damage caused by a drug or herbal product resulting in abnormal liver tests or liver dysfunction, after reasonable exclusion of competing etiologies (Raschi E et al., 2014). Antifungal drugs can be classified as polyenes, antimetabolite—flucytosine (5-FC), azoles, echinocandins, the latter two being more common, which are the first-line option for the prevention and treatment of fungal infections caused by immunosuppression (Nett and Andes, 2016). In recent years, due to the epidemic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the advancement of immunosuppressive techniques, the number of patients with severely weakened immune systems has increased, and the incidence of fungal infections has continued to rise (Tverdek et al., 2016). With the wide application of antifungal drugs, the safety of antifungal drugs has been concerned.

There are many adverse reactions to antifungal drugs, such as hepatotoxicity and hormone-related effects (gynecomastia, alopecia, decreased libido, oligospermia, azoospermia and so on), among which hepatotoxicity is the most common. An article summarized that all azoles have abnormal liver function and hepatotoxicity, and the frequency of adverse reactions varies by drug and patient population (Benitez and Carver, 2019). A real-world study found that about 2.9% of all reported drug-induced liver injuries are associated with antifungal drugs (Raschi et al., 2014). Another retrospective study reported the prevalence of micafungin-associated DILI was 10.6% (Mullins et al., 2020). It can be seen that almost all antifungal drugs have certain hepatotoxicity.

However, the current studies are based on a case or retrospective study of a drug, and there are few real-world studies. The existing real-world study was in 2014, and the data need to be further updated. In this context, this study aims to characterize the liver injury induced by various antifungal drugs in a large population by using FAERS. We further examined and compared the onset-time and outcomes of liver injury with different antifungal drugs.

Methods

Data Source

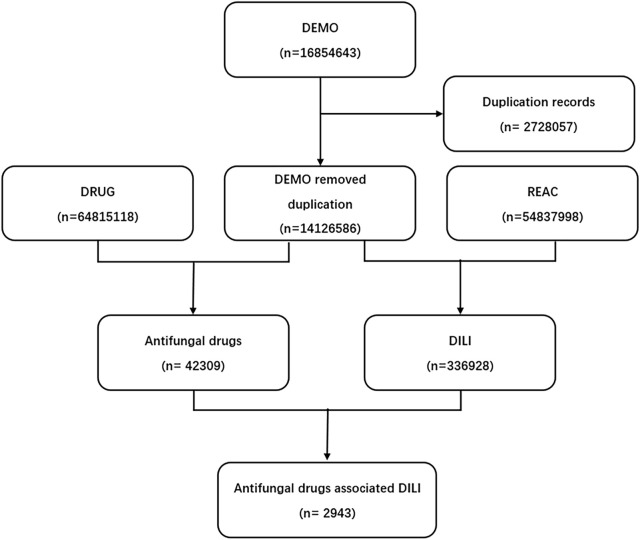

We conducted a retrospective pharmacovigilance study using the FAERS database from the first quarter of 2004 to the third quarter of 2021. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) is a database designed to support FDA’s post-marketing monitoring plan for drugs and therapeutic biological products, which includes all Adverse drug reaction (ADR) signals and medication error information collected by FDA. A FAERS data contains demographic information, drug information, adverse events, patient outcomes, indications, duration of use, time to adverse reactions, and more. Finally, a total of 16854643 reports were obtained from the FAERS database (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Process of the selection of cases of antifungal drugs-associated liver injury from the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database. DEMO, demographic information; DRUG, drug information; REAC, adverse events.

Adverse Event and Drug Identification

DILI cases were obtained by searching using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 23.0), and the preferred terms are shown in Table 1. Study drugs were antifungal triazoles (ketoconazole, miconazole, clotrimazole, fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole, isavuconazole, posaconazole) and echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin) on the market.

TABLE 1.

MedDRA preferred terms used to retrieve liver events in FAERS.

| PT |

|---|

| Liver injury |

| Liver damage |

| Liver necrosis |

| Hepatic damage |

| Hepatotoxicity |

| Hepatopathy |

| Hepatic disease |

| Hepatitis |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| Liver fatty infiltration |

| Steatohepatitis |

| Hepatic steatosis |

| Jaundice |

| Icterus |

| Cholestasis |

| Bile duct damage |

| Biliary cholangitis |

| Hepatobiliary disease |

| Hepatic encephalopathy |

| Hepatic failure |

| Hepatic vascular injury |

| Hepatic cirrhosis |

| Portal hypertension |

| DILI |

| Hepatic necrosis |

| Hepatocellular injury |

| Hepatomegaly |

| Hepatic enzyme abnormal |

| Hepatic enzyme increased |

| Transaminases increased |

| Transaminases abnormal |

| Blood bilirubin abnormal |

| Blood bilirubin increased |

| Aspartate aminotransferase abnormal |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased |

| Hepatic injury |

| Hepatic function abnormal |

| Hepatocellular damage |

| Cirrhosis |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia |

| Liver transplant |

| Alanine aminotransferase abnormal |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased |

| Ammonia increased |

| Bilirubin conjugated increased |

| Bilirubin urine |

| Blood bilirubin unconjugated |

| Increased |

| Coma hepatic |

| Hyperammonaemia |

| Liver function test abnormal |

| Mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic injury |

| Urine bilirubin increased |

PT, preferred terms.

Data Mining

Based on the principles of Bayesian analysis and disproportionality analysis, we used the reporting odds ratio (ROR), the proportional reporting ratio (PRR), the Bayesian confidence propagation neural network and the multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker algorithms to explore the associations between antifungal drugs and DILI (Evans et al., 2001; Szarfman et al., 2002; van Puijenbroek et al., 2002; Hauben et al., 2005; Norén et al., 2006; Ooba and Kubota, 2010; Szumilas, 2010). A two-by-two contingency table (Table 2) of reported event counts for specific drug and other drugs was constructed to calculate ROR, PRR, information component (IC), and empirical Bayesian geometric mean (EBGM). The former two belong to disproportionality analysis, while the latter two belong to Bayesian analysis. The calculation formula and criteria follow: Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Two-by-two contingency table for disproportional analysis.

| DILI | All other adverse drug reactions | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antifungal drugs | a | c | a + c |

| All other drugs | b | d | b + d |

| Total | a + b | c + d | a+b + c + d |

ROR = (a/b)/(c/d), ;

PRR = (a / [a + c]) / (b / [b + d]), ; ;

.

CI, indicates confidence interval; n, indicates the number of co-occurrences; χ2, indicates chi-squared; IC, indicates information component; IC025, indicates the lower limit of the 95% two-sided CI of the IC; EBGM05, the lower limit of the 90% one-sided CI of the EBGM.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to summarize the characteristics of adverse event reports on antifungal drug-related liver injuries collected from the FAERS database. We analyzed the age, sex, reporters, country, area and reporting time distribution of different antifungal agents, and compared the onset time and mortality differences of different antifungal agents.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

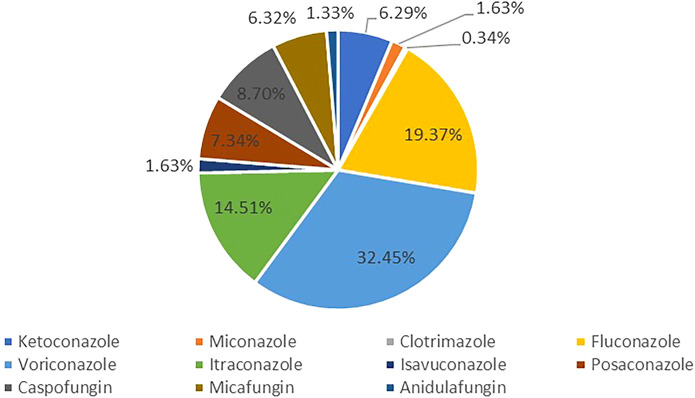

FAERS database from the first quarter in 2004 to the third quarter in 2021 contained 42309 antifungal drugs-related adverse events and 336928 DILI-related reports, among these 2943 were reported for DILI after using antifungal (Figure 1). The clinical characteristics of patients with antifungal drug-induced liver injuries were described in Table 3 and Figure 2. Most of the patients were older than 45 years (51.38%), and men accounted for a larger proportion than women in all reports (49.03% vs. 38.09%). Most cases were reported from Europe (40.88%), Asia (25.35%) and North America (23.41%), and were reported by the physician (40.47%). More and more cases were reported from 2016 (5.27%) to 2020 (9.14%), reflecting the significantly increased usage of antifungal drugs in recent years. Voriconazole ranked first in the number of cases (955), followed by fluconazole and itraconazole.

TABLE 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients with antifungal drugs-associated DILI sourced from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database (2004q1 to 2021q3).

| Characteristics | Reports, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient age (year) | |

| <18 | 218(7.41%) |

| 18–44 | 511 (17.36%) |

| 45–64 | 755(25.65%) |

| 65–74 | 432 (14.68%) |

| 75–84 | 264 (8.97%) |

| ≥85 | 61 (2.07%) |

| Unknow | 702(23.85%) |

| Reporter | |

| Consumer | 306 (10.40%) |

| Lawyer | 1 (0.03%) |

| Other health-professional | 808(27.45%) |

| Pharmacist | 345 (11.72%) |

| Physician | 1191(40.47%) |

| Unknow | 292 (9.92%) |

| Patient gender | |

| Female | 1121 (38.09%) |

| Male | 1443(49.03%) |

| Unknow | 379(12.88%) |

| Year | |

| 2004 | 136 (4.62%) |

| 2005 | 132 (4.49%) |

| 2006 | 134 (4.55%) |

| 2007 | 120 (4.08%) |

| 2008 | 117(3.98%) |

| 2009 | 137 (4.66%) |

| 2010 | 152 (5.16%) |

| 2011 | 129 (4.38%) |

| 2012 | 154 (5.23%) |

| 2013 | 156(5.30%) |

| 2014 | 124 (4.21%) |

| 2015 | 174 (5.91%) |

| 2016 | 155 (5.27%) |

| 2017 | 183 (6.22%) |

| 2018 | 231(7.85%) |

| 2019 | 262 (8.90%) |

| 2020 | 269 (9.14%) |

| 2021 | 171 (5.81%) |

| Unknow | 6 (0.20%) |

| Area | |

| Africa | 26 (0.88%) |

| Asian | 746(25.35%) |

| Europe | 1203(40.88%) |

| North America | 689 (23.41%) |

| Oceania | 39 (1.33%) |

| South America | 34 (1.16%) |

| Unknow | 206 (7.00%) |

| Antifungal drugs | |

| Ketoconazole | 188 (6.29%) |

| Miconazole | 48 (1.63%) |

| Clotrimazole | 10 (0.34%) |

| Fluconazole | 570 (19.37%) |

| Voriconazole | 955 (32.45%) |

| Itraconazole | 427 (14.51%) |

| Isavuconazole | 48 (1.63%) |

| Posaconazole | 216 (7.34%) |

| Caspofungin | 256 (8.70%) |

| Micafungin | 186 (6.32%) |

| Anidulafungin | 39 (1.33%) |

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of antifungal drugs-related liver injury.

Disproportionality Analysis and Bayesian Analysis

Data showed a strong association between antifungals and DILI, with no positive signals detected only for miconazole and clotrimazole. In addition, there were two other drugs with one or two negative signals according to the criteria of the four algorithms: which are ketoconazole in EBGM: 2.21(1.95), and isavuconazole in ROR: 1.22(0.92–1.63), PRR: 1.22(1.88) and EBGM: 1.22(0.96). The intraclass analysis of correlation between different antifungal agents and DILI showed the following ranking: caspofungin (ROR = 6.12; 95%CI: 5.36–6.98) > anidulafungin (5.15; 3.69–7.18) > itraconazole (5.06; 4.58–5.60) > voriconazole (4.58; 4.29–4.90) > micafungin (4.53; 3.89–5.27) > posaconazole (3.99; 3.47–4.59) > fluconazole (3.19; 2.93–3.47) > ketoconazole (2.28; 1.96–2.64) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Association of antifungal drugs with DILI.

| Drugs | N | ROR | PRR | IC | EBGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% Two-sided CI) | (χ2) | (IC025) | (EBGM05) | ||

| Ketoconazole | 188 | 2.28 (1.96, 2.64)* | 2.21 (127.22)* | 1.14 (0.99)* | 2.21(1.95) |

| Miconazole | 48 | 0.30 (0.23, 0.40) | 0.31 (77.37) | −1.71() | 0.31 (0.24) |

| Clotrimazole | 10 | 0.16 (0.08, 0.29) | 0.16 (44.96) | −2.64 () | 0.16 (0.10) |

| Fluconazole | 570 | 3.19 (2.93, 3.47)* | 3.03 (793.68)* | 1.60 (1.47)* | 3.03 (2.82)* |

| Voriconazole | 955 | 4.58 (4.29, 4.90)* | 4.22 (2400.98)* | 2.08 (1.94)* | 4.22 (3.99)* |

| Itraconazole | 427 | 5.06 (4.58, 5.60)* | 4.62 (1237.69)* | 2.21 (1.99)* | 4.61 (4.24)* |

| Isavuconazole | 48 | 1.22 (0.92, 1.63) | 1.22 (1.88) | 0.28 (0.21)* | 1.22 (0.96) |

| Posaconazole | 216 | 3.99 (3.47, 4.59)* | 3.72 (440.63)* | 1.90 (1.65)* | 3.72 (3.31)* |

| Caspofungin | 256 | 6.12 (5.36, 6.98)* | 5.45 (952.64)* | 2.45 (2.14)* | 5.45 (4.88)* |

| Micafungin | 186 | 4.53 (3.89, 5.27)* | 4.18 (460.10)* | 2.06 (1.77)* | 4.17 (3.68)* |

| Anidulafungin | 39 | 5.15 (3.69, 7.18)* | 4.69 (115.82)* | 2.23 (1.60)* | 4.69 (3.55)* |

ROR, reporting odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PRR, proportional reporting ratio; χ2, chi-squared; IC, information component; EBGM, empirical Bayesian geometric mean; “*” suggests that antifungal agents are associated with DILI.

Onset Times of DILI

The median onset times of DILI for each antifungal drugs are summarized in Table 5. The onset time of DILI was significantly different among different antifungal drugs (p < 0.0001). Significant differences were noted for ketoconazole vs. posaconazole (p = 0.0460), ketoconazole vs. caspofungin (p = 0.0006), ketoconazole vs. micafungin (p = 0.0018), voriconazole vs. caspofungin (p = 0.0248), itraconazole vs. caspofungin (p < 0.0001), itraconazole vs. micafungin (p = 0.0005).

TABLE 5.

Onset times of DILI associated with antifungals.

| Antifungal drugs | M(IQR)(d) |

|---|---|

| Ketoconazole | 21 (7–40) |

| Miconazole | 22 (2.5–45.75) |

| Fluconazole | 8 (3–17.25) |

| Voriconazole | 8 (2–20) |

| Itraconazole | 11 (4–32.5) |

| Isavuconazole | 7 (0–56.5) |

| Posaconazole | 6 (2–19) |

| Caspofungin | 5 (2–11) |

| Micafungin | 5 (1.5–12.5) |

| Anidulafungin | 4 (1–12) |

M, median; IQR, interquartile range; d, days.

Outcomes due to DILI

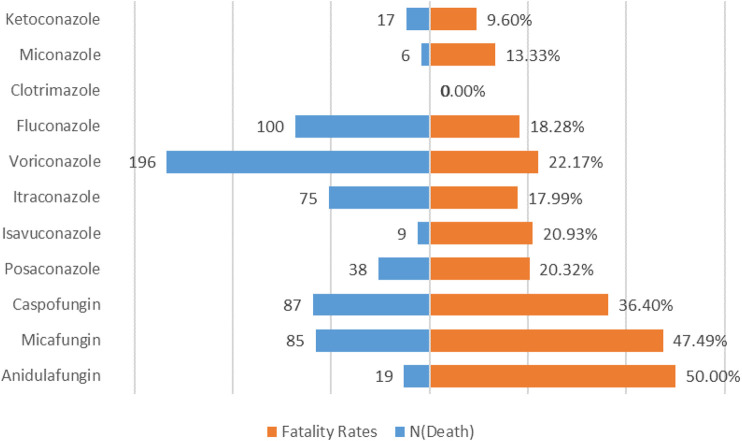

To analyze the prognosis of antifungal drugs-induced liver injuries, we calculated the proportion of outcomes (death, disability, hospitalization, life-threatening, other serious and required intervention) due to DILI after various antifungal drugs treatments, and the results are shown in Table 6. Patients with antifungal-related liver damage tended to have poor outcomes, with approximately 42.21% of patients hospitalized and 22.86% dying. In addition, a significant difference in the mortality rate of DILI was found between different antifungal drugs (p < 0.0001). Anidulafungin results in the highest mortality rate (50.00%), while ketoconazole has the lowest mortality rate (9.60%). The mortality rate for each drug is shown in Figure 3.

TABLE 6.

Outcomes events of DILI.

| Ketoconazole | Miconazole | Clotrimazole | Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Itraconazole | Isavuconazole | Posaconazole | Caspofungin | Micafungin | Anidulafungin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congenital Anomaly | 0(0.00) | 1(2.22) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 2(0.48) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) |

| Death | 17(9.60) | 6(13.33) | 0(0.00) | 100(18.28) | 196(22.17) | 75(17.99) | 9(20.93) | 38(20.32) | 87(36.40) | 85(47.49) | 19(50.00) |

| Disability | 3(1.69) | 1(2.22) | 0(0.00) | 10(1.83) | 24(2.71) | 9(2.16) | 0(0.00) | 7(3.74) | 8(3.35) | 9(5.03) | 1(2.63) |

| Hospitalization - Initial or Prolonged | 67(37.85) | 24(53.33) | 6(66.67) | 292(53.38) | 322(36.43) | 157(37.65) | 17(39.53) | 88(47.06) | 123(51.46) | 57(31.84) | 14(36.84) |

| Life-Threatening | 11(6.21) | 3(6.67) | 0(0.00) | 51(9.32) | 86(9.73) | 22(5.28) | 0(0.00) | 23(12.30) | 41(17.15) | 31(17.32) | 6(15.79) |

| Other Serious | 117(66.10) | 28(62.22) | 7(77.78) | 327(59.78) | 638(72.17) | 265(63.55) | 39(90.70) | 132(70.59) | 126(52.72) | 101(56.42) | 21(55.26) |

| Required Intervention to Prevent Permanent Impairment/Damage | 3(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 4(0.73) | 6(0.68) | 2(0.48) | 0(0.00) | 2(1.07) | 1(0.42) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) |

FIGURE 3.

Mortality rate for DILI associated with antifungal drugs.

Discussion

Drug-induced liver injury is classified as intrinsic, idiosyncratic and indirect, and the idiosyncratic type can be divided into hepatocellular injury, cholestatic liver injury and mixed liver injury (Garcia-Cortes et al., 2020). Patients with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 5 times the upper limit of normal or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) > 2 times the upper limit of normal were considered suspected DILI. If ALT/ALP ≥5, it is defined as Hepatocellular injury; if ALT/ALP ≤2, it is defined as Cholestatic liver injury; if 2 < ALT/ALP <5, it is defined as Mixed liver injury (Danan and Theschke, 2015).

Triazole drugs prevent the synthesis of ergosterol by inhibiting C14 (a sterol demethylase), thereby reducing sterol precursors and ergosterol, and destroying the integrity of the fungal cell membrane, thus achieving the antifungal effect (Nett and Andes, 2016). The exact mechanism of hepatotoxicity induced by triazole drugs remains unclear. They competitively inhibit liver oxidative metabolism by rapidly and reversibly binding CYP450 metabolic enzymes, and are both substrates and inhibitors of various CYP450 metabolic enzymes, with potential for drug interactions (Zonios and Bennett, 2008). Drug interactions increase the risk of increased toxicity leading to liver damage. Itraconazole is metabolized primarily by the CYP450 isoenzyme CYP3A4; voriconazole is metabolized by the CYP450 isoenzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 (Haria et al., 1996; Alffenaar et al., 2009). In addition, itraconazole, but not voriconazole, is an inhibitor of gastric P-glycoprotein, a transmembrane efflux pump that limits blood drug concentrations by expelling the drug into the intestinal lumen (Wang et al., 2002). Itraconazole inhibits drug efflux by inhibiting P-glycoprotein, resulting in increased plasma concentrations and increased systemic exposure of the drug, so itraconazole has a higher risk of liver damage. Fluconazole is metabolized mainly through the kidney (Shiba et al., 1990), but not extensively through the liver, so its hepatotoxicity is relatively low. The echinocandins damage fungal cell walls by inhibiting the synthesis of B-1,3 glucan, a fungal cell wall polysaccharide essential to many fungi. The echinocandins are eliminated mainly by non-enzymatic degradation to an inactive product. Although they are not significantly metabolized by CYP450 enzymes, caspofungin and micafungin are metabolized in the liver and thus have less hepatotoxicity (Nett and Andes, 2016).

This study found that almost all antifungal drugs can cause liver damage, and the association of echinocandins is significantly higher than that of triazoles. In previous studies, hepatotoxicity of echinocandins was considered to be significantly lower than that of triazoles (Tverdek et al., 2016; Kyriakidis et al., 2017). An in vitro study found that caspofungin exhibited mild hepatotoxicity, whereas fluconazole and voriconazole exhibited higher hepatotoxicity (Doß et al., 2017). Due to the low hepatotoxicity of echinocandins, some echinocandins have been used safely in patients with pre-existing liver damage, namely caspofungin in patients with chronic liver disease and post-liver transplantation (Mycamine., 2010). A retrospective study found that patients with abnormal liver enzymes at baseline had an increased overall incidence of liver injury compared with patients without elevated liver enzymes at baseline (Takeda et al., 2007). Since echinocandins are widely used in patients with liver damage themselves, if the liver damage worsens after medication, the case may be reported to FAERS as DILI. Therefore, patients with echinocandins-related liver damage will be higher than the actual liver damage caused by drugs. The basic number of patients is large, so there is a strong correlation between echinocandins and liver damage, which is also a shortcoming of this study. Due to indication bias in real-world studies, the ROR of echinocandins was higher than that of triazoles.

Of note, we also found that the correlation between different triazoles and DILI showed the following ranking: itraconazole > voriconazole > fluconazole > ketoconazole. Previous studies considered ketoconazole to be the most hepatotoxic triazole, and ketoconazole was withdrawn from the market precisely due to its hepatotoxic effect and better-evaluated alternatives, so the ROR of this study was reduced accordingly. Numerous studies have shown that voriconazole and itraconazole are more hepatotoxic than other triazoles (Kullberg et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010), possibly due to their ability to inhibit CYP450, resulting in significant drug-drug interactions, which in turn alter circulating plasma levels of concomitant drugs and increase liver toxicity.

Another finding is that the mortality rate of echinocandins was significantly higher than that of triazole. Among echinocandins, anidulafungin has the highest mortality rate. Anidulafungin is the only echinocandin that is not metabolized through the liver, and dose adjustment is not required even in patients with severe hepatic insufficiency (Patil and Majumdar, 2017), therefore, clinicians may prefer to use anidulafungin in patients with a history of hepatotoxicity. A small retrospective study found that anidulafungin was used more than micafungin in patients with liver failure, confirming real-world channel bias (van der Geest et al., 2016). Another retrospective study also found that baseline liver function impairment and other more serious comorbidities were more likely to be in patients using anidulafungin (van der Geest et al., 2016; Vekeman et al., 2018). Therefore, the highest mortality rate of anidulafungin may be affected by the patients’ condition. However, due to the significant risk of liver injury of azole drugs, clinicians will strictly grasp the indications and monitor the level of liver function when using them and stop taking them in time to relieve the condition when liver enzymes are significantly increased. In most cases using triazoles, liver enzymes returned to normal and symptoms disappeared within a few weeks after drug withdrawal (Song and Deresinski, 2005), so triazole mortality is relatively low.

We acknowledge that our research has certain limitations. First, the FAERS database is a fully open website, so the absolute authenticity of data cannot be guaranteed, and there may be duplicate samples and imperfect data. Due to underdeveloped information in some regions, a lot of data have not been recorded in the database, for example, the sample of Africa is only 0.88%. Secondly, this study selected all patients with liver damage after medication, which could not exclude further aggravation of liver damage in patients with abnormal liver function, so there was a certain bias. Finally, this paper did not use Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) to define DILI, but screened all patients with liver enzyme abnormalities or liver damage, so the data were not accurate to some extent. Therefore, the FAERS database cannot be directly used to calculate the incidence of DILI, but it can be used as a pharmacovigilance tool to remind pharmacists to use antifungals with caution.

The current study showed that antifungal drugs are significantly associated with DILI, and itraconazole and voriconazole had the greatest risk of liver injury. Clinicians are advised to monitor and consider patients’ liver function when taking antifungal drugs. At the same time, due to indication bias, more clinical studies are needed to confirm the safety of echinocandins.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to all those who helped me during the writing of this paper. My deepest gratitude goes to Huajun Sun, director of the Department of Pharmacy, Shanghai Children’s Hospital, for his support and help in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

Z-XZ analyzed and interpreted data, plotted figures, and wrote the manuscript draft. X-DY, YZ, Q-HS and X-YM participated in the interpretation of data. BZ, Y-LS and Z-LL designed and directed the research. W-JH, Y-LS and Z-LL assisted in preparing this manuscript and providing constructive suggestions.

Funding

Project Sponsored by Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 21DZ2300700), Shanghai “Rising Stars of Medical Talent” Youth Development Program “Outstanding Youth Medical Talent” (No.SHWSRS (2021)_099), Shanghai Talent Development Funding(No. 2020110), "Innovative Training Program for College Students," School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University (No. 1521Y424).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alffenaar J. W., de Vos T., Uges D. R., Daenen S. M. (2009). High Voriconazole Trough Levels in Relation to Hepatic Function: How to Adjust the Dosage? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 67 (2), 262–263. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03315.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez L. L., Carver P. L. (2019). Adverse Effects Associated with Long-Term Administration of Azole Antifungal Agents. Drugs 79 (8), 833–853. 10.1007/s40265-019-01127-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danan G., Teschke R. (2015). RUCAM in Drug and Herb Induced Liver Injury: The Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (1), 14. 10.3390/ijms17010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doß S., Potschka H., Doß F., Mitzner S., Sauer M. (2017). Hepatotoxicity of Antimycotics Used for Invasive Fungal Infections: In Vitro Results. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 9658018. 10.1155/2017/9658018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. J., Waller P. C., Davis S. (2001). Use of Proportional Reporting Ratios (PRRs) for Signal Generation from Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 10 (6), 483–486. 10.1002/pds.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cortes M., Robles-Diaz M., Stephens C., Ortega-Alonso A., Lucena M. I., Andrade R. J. (2020). Drug Induced Liver Injury: an Update. Arch. Toxicol. 94 (10), 3381–3407. 10.1007/s00204-020-02885-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haria M., Bryson H. M., Goa K. L. (1996). Itraconazole. A Reappraisal of its Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Use in the Management of Superficial Fungal Infections. Drugs 51 (4), 585–620. 10.2165/00003495-199651040-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauben M., Madigan D., Gerrits C. M., Walsh L., Van Puijenbroek E. P. (2005). The Role of Data Mining in Pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 4 (5), 929–948. 10.1517/14740338.4.5.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg B. J., Sobel J. D., Ruhnke M., Pappas P. G., Viscoli C., Rex J. H., et al. (2005). Voriconazole versus a Regimen of Amphotericin B Followed by Fluconazole for Candidaemia in Non-neutropenic Patients: a Randomised Non-inferiority Trial. Lancet 366 (9495), 1435–1442. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67490-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis I., Tragiannidis A., Munchen S., Groll A. H. (2017). Clinical Hepatotoxicity Associated with Antifungal Agents. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 16 (2), 149–165. 10.1080/14740338.2017.1270264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins C., Beaulac K., Sylvia L. (2020). Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) with Micafungin: The Importance of Causality Assessment. Ann. Pharmacother. 54 (6), 526–532. 10.1177/1060028019892587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycamine[Package_Insert] (2010). Deerfield (IL): Astellas Pharma Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nett J. E., Andes D. R. (2016). Antifungal Agents: Spectrum of Activity, Pharmacology, and Clinical Indications. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 30 (1), 51–83. 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norén G. N., Bate A., Orre R., Edwards I. R. (2006). Extending the Methods Used to Screen the WHO Drug Safety Database towards Analysis of Complex Associations and Improved Accuracy for Rare Events. Stat. Med. 25 (21), 3740–3757. 10.1002/sim.2473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooba N., Kubota K. (2010). Selected Control Events and Reporting Odds Ratio in Signal Detection Methodology. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 19 (11), 1159–1165. 10.1002/pds.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A., Majumdar S. (2017). Echinocandins in Antifungal Pharmacotherapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 69 (12), 1635–1660. 10.1111/jphp.12780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschi E., Poluzzi E., Koci A., Caraceni P., Ponti F. D. (2014). Assessing Liver Injury Associated with Antimycotics: Concise Literature Review and Clues from Data Mining of the FAERS Database. World J. Hepatol. 6 (8), 601–612. 10.4254/wjh.v6.i8.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K., Saito A., Miyahara T. (1990). Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single Oral and Intravenous Doses of Fluconazole in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Ther. 12 (3), 206–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. C., Deresinski S. (2005). Hepatotoxicity of Antifungal Agents. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 6 (2), 170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szarfman A., Machado S. G., O'Neill R. T. (2002). Use of Screening Algorithms and Computer Systems to Efficiently Signal higher-Than-expected Combinations of Drugs and Events in the US FDA's Spontaneous Reports Database. Drug Saf. 25 (6), 381–392. 10.2165/00002018-200225060-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumilas M. (2010). Explaining Odds Ratios. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 19 (3), 227–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K., Morioka D., Matsuo K., Endo I., Sekido H., Moroboshi T., et al. (2007). A Case of Successful Resection after Long-Term Medical Treatment of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Following Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Transpl. Proc 39 (10), 3505–3508. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.05.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tverdek F. P., Kofteridis D., Kontoyiannis D. P. (2016). Antifungal Agents and Liver Toxicity: a Complex Interaction. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 14 (8), 765–776. 10.1080/14787210.2016.1199272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Geest P. J., Hunfeld N. G., Ladage S. E., Groeneveld A. B. (2016). Micafungin versus Anidulafungin in Critically Ill Patients with Invasive Candidiasis: a Retrospective Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 490. 10.1186/s12879-016-1825-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Puijenbroek E. P., Bate A., Leufkens H. G., Lindquist M., Orre R., Egberts A. C. (2002). A Comparison of Measures of Disproportionality for Signal Detection in Spontaneous Reporting Systems for Adverse Drug Reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 11 (1), 3–10. 10.1002/pds.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekeman F., Weiss L., Aram J., Ionescu-Ittu R., Moosavi S., Xiao Y., et al. (2018). Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing the Risk of Severe Hepatotoxicity in Hospitalized Patients Treated with Echinocandins for Invasive Candidiasis in the Presence of Confounding by Indication. BMC Infect. Dis. 18 (1), 438. 10.1186/s12879-018-3333-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E. J., Lew K., Casciano C. N., Clement R. P., Johnson W. W. (2002). Interaction of Common Azole Antifungals with P Glycoprotein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 (1), 160–165. 10.1128/aac.46.1.160-165.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. L., Chang C. H., Young-Xu Y., Chan K. A. (2010). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Tolerability and Hepatotoxicity of Antifungals in Empirical and Definitive Therapy for Invasive Fungal Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 (6), 2409–2419. 10.1128/AAC.01657-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonios D. I., Bennett J. E. (2008). Update on Azole Antifungals. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 29 (2), 198–210. 10.1055/s-2008-1063858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.