Abstract

KlADH4 is a gene of Kluyveromyces lactis encoding a mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase activity which is specifically induced by ethanol. The promoter of this gene was used for the expression of heterologous proteins in K. lactis, a very promising organism which can be used as an alternative host to Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to its good secretory properties. In this paper we report the ethanol-driven expression in K. lactis of the bacterial β-glucuronidase and of the human serum albumin (HSA) genes under the control of the KlADH4 promoter. In particular, we studied the extracellular production of recombinant HSA (rHSA) with integrative and replicative vectors and obtained a significant increase in the amount of the protein with multicopy vectors, showing that no limitation of KlADH4 trans-acting factors occurred in the cells. By deletion analysis of the promoter, we identified an element (UASE) which is sufficient for the induction of KlADH4 by ethanol and, when inserted in the respective promoters, allows ethanol-dependent activation of other yeast genes, such as PGK and LAC4. We also analyzed the effect of medium composition on cell growth and protein secretion. A clear improvement in the production of the recombinant protein was achieved by shifting from batch cultures (0.3 g/liter) to fed-batch cultures (1 g/liter) with ethanol as the preferred carbon source.

Kluyveromyces lactis is an aerobic yeast which is able to grow on lactose as the sole carbon source. Due to this property, which is rare among yeasts, K. lactis has been used for the purification of the enzyme lactase (β-galactosidase) and for the production of low-lactose milk in the dairy industry (22), and the conditions used for cultivation of this organism on the large scale have been well established. In the last few years, K. lactis has been successfully used as an alternative host to Saccharomyces cerevisiae for heterologous gene expression, and good transformation systems and stable multicopy vectors are now available for the genetic manipulation of this yeast (for reviews, see references 16, 32, and 44). Expression of heterologous genes in K. lactis can be achieved by the use of constitutive promoters which have also been isolated in S. cerevisiae; such promoters are interchangeable between the two yeasts. However, S. cerevisiae inducible promoters are not always tightly regulated in K. lactis cells, suggesting the existence of different regulatory circuits on gene expression in the two organisms.

Regulated promoters have been obtained from the K. lactis genes lactase (LAC4) (18, 26, 33, 46) and acid phosphatase (KlPHO5) (14, 15). These genes are regulated in a very similar way to the corresponding GAL and PHO5 genes of S. cerevisiae, which are induced at the transcriptional level in the presence of lactose or galactose and of low phosphate concentrations, respectively (40, 45).

KlADH4 is a K. lactis gene induced by ethanol, encoding a mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) activity with interesting regulatory properties (35). Such regulation can be observed in Rag− (resistance to antibiotics on glucose) strains of K. lactis, which are unable to grow on glucose in the presence of mitochondrial inhibitors (19). In these strains, which are impaired in sugar fermentation and are poor producers of ethanol, the addition of ethanol specifically induced KlADH4 while the addition of glycerol and other nonfermentable carbon sources did not induce the expression of this gene. Moreover, differently from the ADH2 gene of S. cerevisiae (8–10), the induction of KlADH4 is not sensitive to glucose repression, since the gene is expressed when both glucose and ethanol are present in the culture medium (29, 34).

All these findings suggested to us the possibility of using the promoter regions of KlADH4 for ethanol-dependent expression of heterologous genes in K. lactis Rag− strains. Such strains can be either naturally isolated or constructed in the laboratory by disrupting genes which affect the glycolytic flux, such as KlPGI1 (29), the gene encoding phosphoglucoisomerase, or genes directly involved in ethanol production, such as KlPDC1, the gene encoding pyruvate decarboxylase of K. lactis (3). By contrast, in Rag+ strains, the KlADH4 promoter is also active in cells growing in glucose and other fermentable carbon sources because of the ethanol produced by cells through fermentation, but its transcriptional activity can be still increased (two- to threefold) by the addition of exogenous ethanol (data not shown).

In this paper, we report the isolation of the KlADH4 promoter and its use for the regulated expression of bacterial and human genes. We also identified a small region of the promoter which is responsible for the induction of the gene in the presence of ethanol.

In K. lactis cells, an efficient production of heterologous proteins with enzymatic activity, such as prochymosine (46) and α-galactosidase (1), and proteins of therapeutic interest, such as interleukin-1β (4, 17), hepatitis B surface antigen (28), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (21), and human serum albumin (HSA) (5, 18), have been efficiently produced (for a review, see reference 44).

To optimize the production of recombinant HSA (rHSA) under the control of the KlADH4 promoter, we focused on the medium composition and growth conditions; in preliminary attempts, we obtained good yields of rHSA in fed-batch fermentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The following K. lactis strains were used in this work. MW98-8C (α uraA lys arg rag1 pgi1 adh3) is the parental strain (2). MS1 is a derivative of MW98-8C carrying an integrated copy of plasmid P4GUS into the KlADH4 chromosomal locus (12) CMK5 (a thr lys pgi1 adh3 adh1::URA3 adh2::URA3), which expresses only KlADH4, was obtained by crossing strains that lacked single ADH activities (29). CBS 293.91 is a prototrophic natural K. lactis isolate (12). Y 721 is an isogenic derivative of CBS 293.91 carrying a disrupted copy of the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) gene (12). This strain, used for many generations in batch and fed-batch fermentations, showed a Rag+ phenotype for the presence of the PGK gene on plasmid pYG156. Since the gene is essential for the growth on fermentable carbon sources, such a host-vector combination resulted in the stabilization of the expression system.

Media and culture conditions.

YPD consists of (grams/liter) glucose, 20; yeast extract (Difco), 10; and Bacto Peptone (Difco), 20; supplemented, when required, with 100 mg of Geneticin G418 (Sigma) per liter. When indicated, ethanol (YPE), glycerol (YPG), or glucose plus ethanol (YPDE) at 20, 30, and 20 + 10 g/liter, respectively, were added instead of glucose.

M9YE consists of (grams/liter) carbon substrate, 20; yeast extract, 10; Na2HPO4, 6; KH2PO4, 3; NaCl, 0.5, NH4Cl, 1; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.015; and MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.24.

DM1 (defined medium 1) consists of (grams/liter) carbon substrate, 20; Na2HPO4, 4.4; KH2PO4, 4; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.5; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.1; sodium glutamate, 3; and ammonium acetate, 7; 1 ml of salt solution (13 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O per ml, 9 mg of MnSO4 · H2O per ml, 1.8 mg of CoCl2 · 6H2O per ml, 18 mg of ZnSO4 · 7H2O per ml, 0.9 mg of AlCl3 · 6H2O per ml, 0.22 mg of CuCl2 · 2H2O per ml) per liter, and 1 ml of vitamin solution (13.5 mg of niacin per ml, 0.036 mg of biotin per ml, 1.8 mg of calcium pantothenate per ml, 2 mg of m-inositol per ml) per liter.

Shake flask cultures.

Flasks (300 ml) containing 50 ml of medium were seeded with 0.5 ml of an inoculum grown to the stationary phase on the same medium. Cultures were grown for 3 days at 28°C on a rotary shaker (220 rpm) for rHSA production.

Fed-batch cultures.

Fermentations were carried out in a 2-liter fermentor (SETRIC France) containing 0.8 liter of medium. The fermentor was inoculated with 40 ml of a fresh preculture grown to the stationary phase on the same medium. During fermentation, the pH was automatically controlled and adjusted between 6.5 and 7.0 with 10% (wt/vol) ammonia and the temperature was maintained at 28°C. Aeration was maintained at 75 liters/h under 0.2 × 105 Pa, and the dissolved oxygen was controlled at ∼30% air saturation by the impeller speed controller and, when necessary, by enrichment of the air stream with pure O2. All the process variables (pH, temperature, agitation, dissolved oxygen, and O2 and CO2 contents in the exhaust gases) were transduced on-line and interfaced by a PH3852 unit to a Hewlett-Packard 9000 computer. The compositions of the feed media were carbon source, 340 g/liter; yeast extract, 100 g/liter; ammonium acetate, 50 g/liter; or carbon source, 340 g/liter; sodium glutamate, 40 g/liter; ammonium acetate, 70 g/liter; and vitamins for complex and defined media, respectively.

General methods.

Restriction enzyme digestions, plasmid engineering, and standard techniques were performed as specified by Sambrook et al. (37). Escherichia coli and yeast transformation was performed by electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene-Pulser apparatus as specified by the manufacturer.

PCR amplification and cloning of KlADH4 promoter fragments.

The oligonucleotides used in PCR amplifications are listed in Table 1. PCRs were performed with the GeneAmp kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), using as template a 4.0-kbp genomic DNA region of K. lactis, which contained the KlADH4 gene, cloned on a plasmid. The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 0.2 mM each primer, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1× PCR buffer, 25 ng of DNA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 U of Ampli-Taq DNA polymerase. PCR was carried out for 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min. After amplification, the DNA fragments were purified on agarose gels, digested with the appropriate enzyme, cloned into the pKSII plasmid (Stratagene cloning system), and transferred to K. lactis replicating plasmids by standard procedures.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the oligonucleotides used in PCR amplification of different regions of the KlADH4 promoter

| Nucleotide sequencea | |

|---|---|

| −1197 −1179 | |

| 1 | (SalI) ccccg/tcgacCGGCTACTAATAGAAGTTC |

| −936 −953 | |

| 2 | (SalI) cgcgg/tcgacGGAACGACGGTACATAAG |

| −758 −741 | |

| 3 | (SalI) ccccg/tcgacCGGCGCCTGAAATTTTCC |

| −741 −758 | |

| 4 | (EcoRI) cgcgg/aattcGGAAAATTTCAGGCGCCG |

| −536 −519 | |

| 5 | (SalI) ccccg/tcgacCCAGAAGTCGGAGTTTAC |

| −519 −536 | |

| 6 | (HindIII) cgcga/agcttGTAAACTCCGACTTCTGG |

| −400 −383 | |

| 7S | (SalI) ccccg/tcgacGTGTGTGCTGTGCCTTCC |

| −400 −383 | |

| 7E | (EcoRI) cgcgg/aattcGTGTGTGCTGTGCCTTCC |

| −13 −30 | |

| 8 | (HindIII) cgcga/agcttATGTTGTGTTGTTGGTGG |

Chromosomal sequences of K. lactis are in capital letters.

Vector constructions.

E. coli β-glucuronidase (GUS) and HSA expression vectors pP4-GUS, pYG132, and pYG156 (Fig. 1) were engineered as derivatives of pKD1, a natural plasmid originally isolated from Kluyveromyces drosophilarum (7, 13). pKD1 is structurally related to the S. cerevisiae plasmid 2μm and can stably replicate in K. lactis (2).

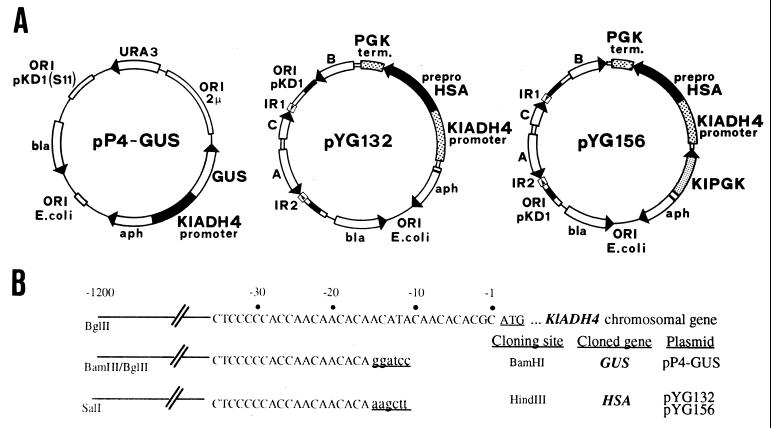

FIG. 1.

(A) pKD1-derived expression vectors for K. lactis. pP4GUS harbours the replication origin (S11) of pKD1 and the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene under the control of the KlADH4 promoter. pYG132 and pYG156 contain the entire pKD1 sequence and the human serum albumin (HSA) gene under the control of the KlADH4 promoter. A, B, and C are pKD1 genes; IR1 and IR2 indicate the inverted repeats of the plasmid. β-Lactamase (bla) and aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (aph) are the genes conferring ampicillin and geneticin (G418) resistance in bacterial and yeast cells, respectively. The uracil auxotrophic marker gene (URA3) and the promoter regions of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and killer toxin (KI) are also indicated. (B) 3′ end sequences and cloning sites of the natural and engineered promoters present in vectors pP4GUS, pYG132, and pYG156.

The details of the construction of pP4-GUS and pYG132 were described previously (12). Briefly, pP4-GUS is a vector derived from vector pSK-Kan401, which contains the pKD1 origin of replication (6). The GUS gene was isolated from plasmid pBI221 (Clontech) as a BamHI-EcoRI fragment, 2.1 kb in length, and placed under control of the KlADH4 BglII-BamHI portable promoter. The resulting expression cassette was introduced as a BglII-EcoRI fragment into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pSK-Kan401. The stability of plasmid pYG132, measured as the percentage of G418-resistant colonies, was 100% after 200 generations.

Construction of KlADH4 promoter-HSA fusion vectors.

In contrast to pP4-GUS, plasmid pYG132 contains the entire sequence of pKD1, linearized at the unique EcoRI site, as well as an HSA expression cassette consisting of the KlADH4 SalI-HindIII portable promoter, the prepro-HSA cDNA gene, and the S. cerevisiae phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) terminator. pYG156 contains the entire pKD1 and the K. lactis PGK gene that can be used as a selectable marker in pgk mutant host strains (12). The common features of all three vectors are the presence of the E. coli origin of replication, allowing the plasmids to work as shuttle vectors, and the presence of the bla and aph genes conferring ampicillin and geneticin resistance to E. coli and yeast, respectively. In addition, pP4-GUS carries the S. cerevisiae URA3 gene as an auxotrophic marker.

The vectors pYG107 and pYG108 contain the entire pKD1 sequence and the HSA cDNA fused to LAC4 and PGK promoters, respectively (18).

To construct pYG534 and pYG397, the region from −536 to −13 was obtained by PCR amplification with oligonucleotides 5 and 8, and the region from −399 to −13 was obtained with oligonucleotides 7S and 8. After SalI-HindIII digestion, these fragments were inserted into plasmid pYG108 to give pYG534 and pYG397, respectively.

To construct pYG108/700M and pYG108ΔUAS, the region from −1199 to −519 was obtained by PCR amplification with oligonucleotides 1 and 6. This SalI-HindIII fragment was cloned into the polylinker of pKSII plasmid. The HindIII site was eliminated by filling in with Klenow polymerase to give plasmid pKSII/700M. The 700-bp fragment was cut by a SalI-NotI digestion and cloned into plasmid pYG108 to give plasmid pYG108/700M. In plasmid pYG108/700M, the region of the PGK promoter from −1499 to −402 containing the upstream activation site (UAS) was replaced by the 700-bp fragment of the KlADH4 promoter. As a control, the pYG108 plasmid was digested with SalI-NotI, filled in with Klenow DNA polymerase, and religated with DNA T4 ligase. The resulting plasmid was called pYG108ΔUAS.

Plasmid pYG108/2-4 contains the promoter regions from −953 to −741 (amplified with oligonucleotides 2 and 4) cloned into the SalI-EcoRI sites of plasmid pYG108/700M.

Plasmid pCM13 carries the region of the KlADH4 promoter spanning from −399 to −13 (amplified with oligonucleotides 7E and 8). The amplified fragment was inserted into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of plasmid pYG108/700M. In this way, the PGK promoter TATA box was replaced with the KlADH4 TATA box.

Plasmid pCM15 was obtained by cloning the promoter fragment contained in plasmids pYG108/2-4 into the SalI-EcoRI sites of pCM13. The promoter regions from −758 to −519 (amplified with oligonucleotides 3 and 6) were cloned in the SalI-HindIII sites of the pKSII polylinker to yield plasmid pKS/3-6. After SalI-EcoRI digestion, the promoter fragment was cloned into pCM13 plasmid to yield plasmid pCM16.

In pCM17, two of the three UAS elements contained in the LAC4 promoter were replaced with the 200-bp fragment containing UASE.

Protein assays.

Cultures (10 ml) of K. lactis were grown to the early stationary phase in YP medium containing different carbon sources as specified in the text. The cells were broken with glass beads in Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed by electrophoresis on 5% nondenaturing acrylamide minigels. Gel preparation and buffers were essentially as described by Williamson et al., (47). Samples corresponding to 20 to 40 μg of proteins were run at 4°C for 60 min at 20 mA. For the detection of ADH activity, the gels were stained as described by Lutstorf and Megnet (27). GUS activity (39) was detected by soaking the gels in a staining solution containing 50 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0) and 50 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide (X-Glu) per ml dissolved in dimethylformamide (5 mg/ml). The gels were then incubated at 37°C until bands corresponding to the enzymatic activities became visibly stained.

Albumin detection.

To detect albumin, 5 × 105 cells/ml were inoculated into YPD or YPDE medium and supernatants were tested after 3 days of fermentation. Aliquots of the supernatants were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, and the protein was revealed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining or by Western blotting. When the latter method was used, aliquots of supernatants were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gels and proteins were electroblotted onto Immobilon P membranes (Millipore) with a Bio-Rad wet blotting system. Filters were saturated by incubation for 30 min at room temperature in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 5% nonfat dry milk. The blots were washed twice in PBST (PBS, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated for 2 h with the anti-HSA monoclonal antibody (Sigma Co.A-0433) diluted 1:16,000 in PBS. After two washes with PBST, the filters were incubated for 1 h with the secondary antibody linked to the alkaline phosphatase. After two final washes, the blots were developed with the 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium system (20).

RESULTS

Cloning of the K. lactis KlADH4 promoter.

The KlADH4 gene was isolated as an 8.4-kb BamHI fragment from a K. lactis genomic bank by using an S. cerevisiae ADH2-derived probe (36). Based on the nucleotide sequence of the KlADH4 coding region (35), we located the ATG initiation codon close to a HindIII site. Accordingly, we subcloned a 2.2-kb HindIII fragment containing the KlADH4 upstream region and the first 14 codons of the coding region into plasmid pTZ19 (Pharmacia). This construct was used to introduce a BamHI site 10 nucleotides upstream from the ATG codon by site-direct mutagenesis by using the double-primer procedures (37). The resulting plasmid allowed the isolation of a 1.2-kb BglII-BamHI portable promoter used in the construction of the pP4-GUS expression vector (Fig. 1). A promoter variant in which the BglII and BamHI sites were replaced by SalI and HindIII sites, respectively, was obtained by the PCR procedure (pBluescript, mung bean nuclease). This variant was used in the engineering of albumin expression vectors pYG132 and pYG156 (Fig. 1).

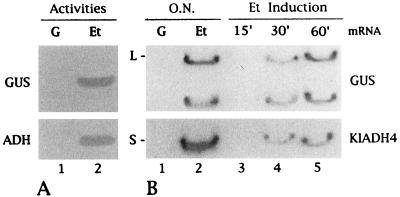

Ethanol-regulated expression of bacterial GUS.

We then wondered whether the KlADH4 promoter could be successfully used for the regulated expression of heterologous genes. First we used the E. coli GUS gene as a reporter gene under control of the KlADH4 upstream region (see Materials and Methods). The resulting plasmid, named pP4-GUS (Fig. 1), was used to transform K. lactis MW98-8C to uracil auxotrophy. This autonomously replicating sequence-containing vector, which is unstable in K. lactis, was used to select for chromosomal integration of the expression cassette. One of the isolated Ura+ transformants, named MS1, expressed GUS activity over many generations. Southern analysis revealed that integration of the expression vector occurred at the chromosomal KlADH4 locus by homologous recombination, which resulted in the duplication of the promoter region without interfering with the integrity of the KlADH4 structural gene (data not shown). In fact, as demonstrated in Fig. 2A, both genes are functionally expressed and they are coregulated in an ethanol-dependent manner. Furthermore, these results show that all elements relevant for regulation are present on the 1.2-kb portable KlADH4 promoter. Moreover, as shown by Northern analysis, GUS- and KlADH4-specific transcripts can be detected as soon as 30 min after induction by ethanol (Fig. 2B). For the GUS gene, besides the mRNA of the expected length (about 2,300 nucleotides), another, larger transcript which migrated at the level of the large rRNA was detected. This transcript, regulated in the same way as the mature mRNA, could represent a precursor molecule.

FIG. 2.

Ethanol-dependent expression of KlADH4 and GUS genes. (A) Strain MS1, carrying the GUS gene under the control of the KlADH4 promoter integrated at the chromosomal KlADH4 locus, was grown overnight on 20 g of glucose per liter (G, lane 1) and 20 g of ethanol per liter (Et, lane 2). The presence in cellular extracts of the ADH IV and GUS activities were revealed by specific staining on native acrylamide gels (see also Materials and Methods). (B) Transcription analysis of KlADH4 and GUS genes after an overnight (O.N.) growth on glucose and ethanol (lanes 1 and 2) and 15 to 60 min after the addition of ethanol to glucose-grown cells (lanes 3 to 5). L and S indicate the migration positions of the large and small rRNAs, respectively.

Production of HSA under control of the KlADH4 promoter on multicopy vectors.

Recently, increasing interest has been focused on the production of HSA in K. lactis. The HSA cDNA gene has been cloned into pKD1-derived vectors under the control of the constitutive PGK promoter of S. cerevisiae and the regulated LAC4 promoter of K. lactis, and good production of the protein has been obtained under different growth conditions (batch, fed batch, and chemostat) (5, 18).

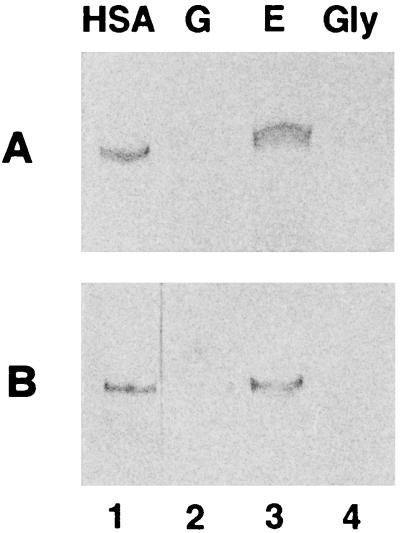

To test whether the KlADH4 promoter could be efficiently used for the biotechnological production of a protein of industrial interest, we engineered vectors carrying the HSA cDNA gene under the control of this promoter. In the first experiment, we integrated the PKlADH4–prepro-HSA expression cassette into the genome of K. lactis. Since the resulting integrants showed very low levels of secreted HSA which could be detected only by immunological methods (data not shown), we examined the production of this protein in K. lactis strains transformed with the pKD1-derived multicopy vector pYG132 (Fig. 1A), which carries 1.2 kbp of the KlADH4 promoter fused to the HSA cDNA. This plasmid was introduced into the nonfermenting strain CMK5, and after 3 days of growth in YP medium containing different carbon sources, aliquots of supernatants were analyzed for the presence of HSA by gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. The protein was revealed either by Coomassie blue staining or by Western blot analysis with an anti-HSA monoclonal antibody (Fig. 3A and B). In CMK5, as in other nonfermenting strains, the HSA was present only in the supernatant of cells grown in ethanol (lane 3) and not in the supernatant of glucose- or glycerol-grown cells (lanes 2 and 4).

FIG. 3.

pYG132-driven production of HSA with strain CMK5. Cells were grown on 20 g of glucose per liter (G), 20 g of glucose per liter plus 10 g of ethanol per liter (E), and 30 g of glycerol per liter (Gly) for three days. After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of supernatants HSA was revealed by Coomassie Blue staining (A) and by Western blotting with a monoclonal antibody, anti-HSA (B). Fifteen and 5 μl of supernatants were loaded in panels A and B, respectively. Commercial HSA was loaded in lane 1 as a marker.

In these experiments, HSA expression levels were at least 30 to 40 times higher than those observed with the single-copy integrant, which is in agreement with the average copy number of pKD1-derived vectors (40 to 60 per cell). Interestingly, these results indicate that even in the presence of multiple copies of the KlADH4 promoter, there is no limitation of trans-acting factors for the induction of the KlADH4 gene.

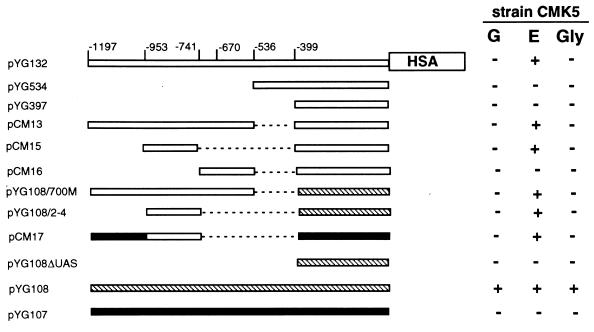

Identification of an ethanol-responsive element.

To identify possible cis-acting elements, we introduced deletions into the KlADH4 promoter and parts of it were also cloned upstream of the TATA box of the heterologous PGK promoter of S. cerevisiae. All constructions were introduced into CMK5 cells, and the level of HSA produced by transformant clones was analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The results of our analysis are reported in Fig. 4. HSA production was not observed on ethanol with KlADH4 promoter deletions upstream of position −536 (plasmids pYG534 and pYG397), suggesting that the putative activating sequences were localized within the deleted regions. On the other hand, we could observe ethanol-driven expression of the HSA cDNA when the region from bp −1197 to −536 was fused to the TATA box of both the KlADH4 (pCM13) and the PGK (pYG108/700M) genes. For this reason, we performed a more detailed analysis of this region.

FIG. 4.

HSA production with CMK5 cells carrying different regions of the KlADH4 promoter grown on 20 g of glucose per liter (G), 20 g of glucose plus 10 g of ethanol per liter (E), and 30 g of glycerol per liter (Gly). Numbers, in approximate scale, refer to the KlADH4 promoter. HSA in supernatants was detected on SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by Coomassie Blue staining and quantified by comparison to known amounts of commercial HSA. All constructions were tested in three independent fermentation experiments. + indicates HSA amounts similar to those observed with the entire KlADH4 promoter induced by ethanol; − indicates undetectable HSA levels.  , KlADH4 promoter; ▧, PGK promoter;

, KlADH4 promoter; ▧, PGK promoter;  , LAC4 promoter.

, LAC4 promoter.

The most important results were obtained with plasmids pCM15 and pYG108/2-4, which contained a region of about 200 bp spanning from −953 to −741 fused to the TATA box of the KlADH4 and PGK genes, respectively. Both plasmids allowed ethanol-dependent expression of the HSA cDNA. In contrast, when this 200-bp region was missing (plasmid pCM16), the regulatory property of the promoter was completely lost. No HSA production could be detected with the control vector pYG108ΔUAS, which contained only the TATA element of PGK.

To further confirm that the region from bp −953 to −741 contained the ethanol-responsive element(s), we substituted this fragment to the upstream activation site (UAS) region of the promoter of LAC4. This is the β-galactosidase-encoding gene of K. lactis, which is induced by lactose and is repressed in the presence of glucose (1, 26, 33, 38). The resulting hybrid LAC4-KlADH4 promoter was fused to the HSA cDNA (plasmid pCM17), and the production of HSA on different carbon sources was monitored. As shown in Fig. 4, this promoter could drive HSA production only in ethanol-grown cells and, as expected, was no longer inducible by lactose (data not shown). In control experiments (plasmid pYG107), the LAC4 promoter fused to the HSA cDNA failed to drive HSA production on glucose, glucose plus ethanol, and glycerol, whereas it allowed HSA production in lactose-grown cells (not shown).

All the above results indicate that the element(s) necessary and sufficient for the induction of KlADH4 by ethanol is located within the 200-bp fragment spanning bp −953 to −741. This element, which also proved functional when inserted in heterologous promoters, was named UASE.

pKlADH4-driven rHSA secretion in fed-batch fermentations.

In shaken-flask cultures, the production of rHSA under inducing conditions reached 200 to 250 mg/liter in defined medium and 300 mg/liter in complex medium, which corresponded to yields of 20 to 30 mg of rHSA/g of dry biomass. These values represent 5 to 7% of the yeast total proteins and 80 to 90% of the total soluble proteins (data not shown).

To improve the rHSA yields, we performed fed-batch fermentations (0.8 liter) on different media. In these experiments, the vector used was pYG156, which carries the PGK gene for selection (see Materials and Methods) and does not confer resistance to the aminoglycoside antibiotic G418. After initial batchwise growth of strain Y 721 in defined medium (DM1) and consumption of the carbon substrate, the feed medium was added to the fermentor by using a peristaltic pump coupled to a preprogrammed time-based feeding profile, deduced from previous experiments where the feeding rate was coupled to the carbon dioxide evolution rate. The carbon substrate used was a mixture of lactose and ethanol (final concentration, 20 g/liter) in different ratios: 50/50, 12/88, and 0/100.

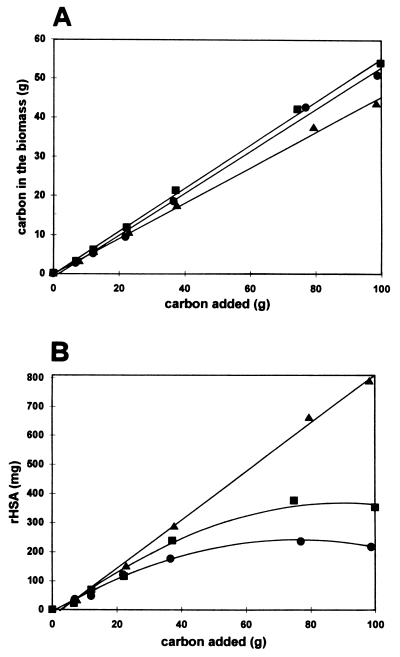

As shown in Fig. 5A, when 100 g of carbon sources was added, 45% of the carbon was recovered in the biomass when 100% ethanol was used, and this value increased to 53% when lactose plus ethanol (12/88) was used. On the other side, the best results in terms of rHSA production were obtained with ethanol as the only carbon substrate (Fig. 5B). In fact, under these conditions, about 800 mg of the protein per liter was produced, compared to 200 and 350 mg/liter obtained when different mixtures of ethanol and lactose were used. In conclusion, at the end of the fermentation time (72 h) with ethanol as the only carbon source, we obtained 71 g (dry-cell weight) of biomass per liter with a yield (Yx/s) of 45%. At the same time, 620 mg of rHSA per liter was produced, with a yield (Yp/x) of 8.7 mg of rHSA/g of biomass and a productivity of 8.7 mg of rHSA/liter · h.

FIG. 5.

Influence of carbon sources on biomass production (A) and rHSA secretion (B) in fed-batch fermentation. K. lactis Y721 (pgk, Rag+), harboring plasmid pYG156, was grown in defined medium containing 20 g of ethanol per liter or mixtures of ethanol and lactose (final concentration, 20 g/liter) as the carbon source. •, lactose-ethanol (50/50); ■, lactose-ethanol (12/88); ▴, lactose-ethanol (0/100).

Kinetics of rHSA secretion in fed-batch fermentations.

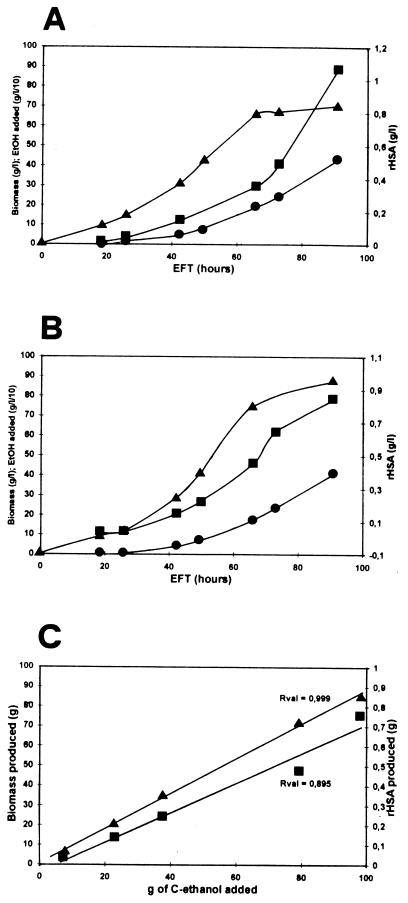

The growth and production kinetics of rHSA in complex medium (ethanol, yeast extract, and ammonium acetate) and a defined medium (ethanol, sodium glutamate, ammonium acetate, vitamins) have been compared. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, the kinetics of growth and the production levels of rHSA were very similar in the two media during the first 3 days, and we could observe an increase in the specific productivity of rHSA from 5 to 30 mg/liter · h between 24 and 72 h of fermentation. After 4 days of culture, a high biomass production occurred in both complex and defined media (70 and 80 g [dry-cell weight]/liter, respectively), with a yield of about 45% as a result of the added ethanol. In this period, the amount of rHSA produced was 1.05 g/liter in complex medium and 0.85 g/liter in defined medium, which corresponded to a productivity of 15 and 10 mg of rHSA/g of biomass, respectively. In both complex and defined media, biomass and rHSA yields were well correlated with the ethanol added during the fed-batch culture (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Kinetics of rHSA secretion, biomass production, and ethanol consumption in fed-batch cultures of K. lactis Y721 (pgk, Rag+) grown in complex medium (A) and defined medium (B and C). •, ethanol; ■, rHSA; ▴, biomass.

DISCUSSION

HSA is the most abundant protein in human plasma involved in the maintenance of a normal osmolarity and also in the transport of hydrophobic molecules. This protein has a big market requirement in that it can be used as replacement fluid during septic or traumatic shock, to compensate for blood loss, and to treat burn victims. At present, HSA is largely produced (300 tons/year) by conventional techniques involving fractionation of plasma obtained from blood donors. It would be a great advantage to be able to use genetic engineering to obtain rHSA in good yield and at lower cost, with no danger of contamination by human pathogens. For this reason, great efforts have been dedicated to the production of this protein on a large scale by genetically engineered microorganisms. For this purpose, rHSA production has been studied in E. coli (24, 25) Bacillus subtilis (38), S. cerevisiae (11, 23, 31, 42, 43), Pichia pastoris (30), and plants (41).

K. lactis is a very promising nonpathogenic organism because of its good secretory capabilities (17, 18, 44, 46), and new promoters with specific properties can be derived from this yeast for the regulated expression of heterologous proteins. In fact, we isolated a new promoter from the KlADH4 gene of K. lactis. This promoter, also present in multicopy vectors, allows regulated or constitutive expression of heterologous genes depending on the host strain used. In nonfermenting strains (Rag−), which are unable to produce intracellular ethanol from fermentable carbon sources, the transcriptional activation of the KlADH4 promoter is dependent on the addition of ethanol to the culture medium. Nonfermenting K. lactis mutants can be easily generated from fermenting strains with particular industrially relevant properties (i.e., biomass yield and secretion efficiency) by disrupting genes which affect ethanol production.

Another interesting aspect of the regulation of this promoter is its insensitivity to glucose repression. This property, combined with the specificity of ethanol as the activator, allows the expression of cloned genes after the addition of the inducer, independently of the carbon source present in the medium.

We identified an ethanol-responsive element (UASE) which is located within a 200-bp region spanning from −953 to −741 of the promoter. Deletions of UASE render the KlADH4 promoter no longer inducible in the presence of ethanol. On the other hand, UASE constitutes an interesting “transportable” cis-acting element for the construction of a regulated chimeric promoter. In fact, UASE can confer ethanol-dependent promoter activation, such as of the S. cerevisiae PGK and K. lactis LAC4 promoters, which are usually not induced by this substrate.

Finally, we studied the production of rHSA under the control of the KlADH4 promoter in K. lactis cells grown in complex and defined media under different cultivation conditions. Considering the results obtained in terms of production per liter of culture, high biomass production (70 to 80 g [dry-cell weight]/liter) was obtained either in both complex and defined media, and a significant amount of rHSA production was observed in fed-batch cultures (1 g/liter) as compared to batch cultures (0.2 to 0.3 g/liter). These values are similar to those obtained under the same conditions with the HSA gene under the control of the PGK and LAC4 promoters (18).

On the basis of other studies, it should certainly be possible to increase the level of production of rHSA to at least 2 g/liter by working on the fermentation parameters. As an example, under the culture conditions used, the oxygen uptake rate never exceeded 2 mM/min.

In conclusion, we believe that the yields of rHSA obtained can be improved and that the process can be scaled up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Michele Saliola and Cristina Mazzoni contributed equally to this work.

Cristina Mazzoni was supported by a fellowship from the Istituto Pasteur-Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti. This work was supported by EC contract BIO4-CT96-0003 and partially supported by MURST (Ministero della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica).

We would like to thank F. Castelli for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergkamp R J M, Kool I M, Geerse R H, Planta R J. Multiple-copy integration of the α-galactosidase gene from Cyamopsis tetragonoloba into the ribosomal DNA of Kluyveromyces lactis. Curr Genet. 1992;21:365–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00351696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi M M, Falcone C, Chen X J, Wesolosky M, Frontali L, Fukuhara H. Transformation of the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis by new vectors derived from the 1.6 μm circular plasmid pKD1. Curr Genet. 1987;12:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi M M, Tizzani L, Destruelle M, Frontali L, Wesolowsky-Louvel M. The “petite-negative” yeast Kluyveromyces lactis has a single gene expressing pyruvate decarboxylase activity. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:27–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.346875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blondeau K, Boutur O, Boze H, Jung G, Moulin G, Galzy P. Development of high-cell-density fermentation for heterologous interleukin-1β production in Kluyveromyces lactis controlled by the PHO5 promoter. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;41:324–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00221227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blondeau K, Boze H, Jung G, Moulin G, Galzy P. Physiological approach to heterologous human serum albumin production by Kluyveromyces lactis in chemostat culture. Yeast. 1994;10:1297–1303. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X J, Fukuhara H. A gene fusion system using the aminoglycoside 3′ phosphotransferase of the kanamycin resistance transposon Tn903: use in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1988;69:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X J, Saliola M, Falcone C, Bianchi M M, Fukuhara H. Sequence organization of the circular plasmid pKD1 from the yeast Kluyveromyces drosophilarum. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4471–4481. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciriacy M. Genetics of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Two loci controlling synthesis of the glucose repressible ADH II. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;138:157–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02428119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciriacy M. Isolation and characterization of further cis and trans acting regulatory elements involved in the synthesis of glucose repressible alcohol dehydrogenase II isozyme from the yeast S. cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;176:427–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00333107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis C L, Ciriacy M, Young E T. A positive regulatory gene is required for the accumulation of the functional messenger RNA of glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from S. cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etcheverry T, Forrester W, Hitzeman R. Regulation of the chelatin promoter during the expression of human serum albumin or yeast phosphoglycerate kinase in yeast. Bio/Technology. 1986;4:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcone C, Fleer R, Saliola M. Yeast promoter and its use. May 1997. Patent no. 5,627,046. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falcone C, Saliola M, Chen X J, Frontali L, Fukuhara H. Analysis of the 1.6 μm circular plasmid from the yeast Kluyveromyces drosophilarum: structure and molecular dimorphism. Plasmid. 1986;15:248–252. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(86)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fermiñàn E, Dominguez A. The KlPHO5 gene encoding a repressible acid phosphate in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis: cloning, sequencing and trancriptional analysis of the gene, and purification properties of the enzyme. Microbiology. 1997;143:2615–2625. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fermiñán E, Domínguez A. Heterologous protein secretion directed by a repressible acid phosphatase system of Kluyveromyces lactis: characterization of upstream region-activating sequences in the KlPH05 gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2403–2408. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2403-2408.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleer R. Engineering yeast for high level expression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1992;3:486–496. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(92)90076-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleer R, Chen X J, Amellal N, Yeh P, Founier A, Guinet F, Gault N, Faucher F, Fukuhara H, Mayaux J F. High-level secretion of correctly processed recombinant human interleukin-1β in Kluyveromyces lactis. Gene. 1991;107:285–295. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90329-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleer R, Yeh P, Amellal N, Maury I, Fournier A, Bacchetta F, Baduel P, Jung G, L’Hôte H, Becquart J, Fukuhara H, Mayaux J F. Stable multicopy vectors for high-level secretion of recombinant human serum albumin by Kluyveromyces yeast. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:968–975. doi: 10.1038/nbt1091-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffrini P, Algeri A A, Donnini C, Wesolowski-Louvel M, Ferrero I. RAG1 and RAG2: nuclear genes involved in the dependence/independence on mitochondrial respiratory function for growth on sugar. Yeast. 1989;5:99–106. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hua Z, Liang X, Zhu D. Expression and purification of a truncated macrophage colony stimulating factor in Kluyveromyces lactis. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;34:419–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussein L, Elasyed S, Fod S. Reduction of lactose in milk by purified lactase produced by Kluyveromyces lactis. J Food Prot. 1989;52:30–34. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-52.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalman M, Cserpan I, Bajszar G, Dobi A, Horvath E, Pazman C, Simoncsits A. Synthesis of a gene for human serum albumin and its expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6075–6081. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latta M, Knap M, Sarmientos P, Brefort G, Becquart J, Guerrier L, Jung G, Mayaux J F. Synthesis and purification of mature human serum albumin from Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:1309–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawn R M, Adelman J, Bock S, Franke A, Houck C, Najarian R, Seeburg P, Wion L. The sequence of human serum albumin cDNA and its expression in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:6103–6114. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.22.6103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonardo J M, Bhairi S M, Dickson R C. Identification of upstream activator sequence that regulate induction of the β-galactosidase gene in Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4369–4376. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutstorf U, Megnet R. Multiple forms of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccaromyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;126:933–944. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez E, Morales J, Aguiar J, Pineda Y, Izquierdo M, Ferbeyre G. Cloning and expression of hepatitis B surface antigen in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Biotechnol Lett. 1992;14:83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzoni C, Saliola M, Falcone C. Ethanol-induced and glucose-insensitive alcohol dehydrogenase activity in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2279–2286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtani W, Ohda T, Sumi A, Kobayashi K, Ohmura T. Analysis of Pichia pastoris components in recombinant human serum albumin by immunological assays and by HPLC with pulsed amperometric detection. Anal Chem. 1998;70:425–429. doi: 10.1021/ac970596h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okabayashi K, Nakagawa Y, Hayasuke N, Ohi H, Miura M, Ishida Y, Shimizu M, Murakami K, Hirabayashi K, Minamino H E A. Secretory expression of the human serum albumin gene in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1991;110:103–110. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanos M A, Scorer C A, Clare J J. Foreign gene expression in yeast: a review. Yeast. 1992;8:423–488. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruzzi M, Breunig K D, Ficca A G, Hollenberg C P. Positive regulation of the β-galactosidase gene from Kluyveromyces lactis is mediated by an upstream activation site that shows homology to the GAL upstream activation site of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:991–997. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saliola M, Falcone C. Two mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase activities of Kluyveromyces lactis are differentially expressed during respiration and fermentation. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249:665–672. doi: 10.1007/BF00418036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saliola M, Gonnella R, Mazzoni C, Falcone C. Two genes encoding putative mitochondrial alcohol dehydrogenase are present in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast. 1991;7:391–400. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saliola M, Shuster J R, Falcone C. The alcohol dehydrogenase system in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast. 1990;6:193–204. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders C W, Schmidt B J, Mallonee R L, Guyer M S. Secretion of human serum albumin from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2917–2925. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.2917-2925.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitz U K, Lonsdale D M, Jefferson R A. Application of the beta-glucuronidase gene fusion system to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1990;17:261–264. doi: 10.1007/BF00312618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuster J R. Regulated transcriptional system for the production of proteins in yeast: regulation by carbon source. In: Barr P J, Brake A J, Valenzuela P, editors. Yeast genetic engineering. London, United Kingdom: Butterworths; 1989. pp. 83–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sijmons P C, Dekker B M, Schrammeijer B, Verwoerd T C, van den Elzen P J, Hoekema A. Production of correctly processed human serum albumin in transgenic plants. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt0390-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sleep D, Belfield G P, Ballance D J, Steven J, Jones S, Evans L R, Moir P D, Goodey A R. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that overexpress heterologous proteins. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt0291-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sleep D, Belfield G P, Goodey A R. The secretion of human serum albumin from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae using five different leader sequences. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt0190-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swinkels B W, van Ooyen A J J, Bonekamp F J. The yeast Kluyveromyces lactis as an efficient host for heterologous gene expression. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1993;64:187–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00873027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toh-e A. Phosphorus regulation in yeast. In: Barr P J, Brake A J, Valenzuela P, editors. Yeast genetic engineering. London, United Kingdom: Butterworths; 1989. pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van De Berg J A, Van Der Laken K J, Van Ooyen J J, Renniers T C H M, Rietveldk A, Schaap A, Brake A J, Bishop R J, Schulz K, Moyer D, Richman M, Shuster J R. Kluyveromyces as a host for heterologous gene expression: expression and secretion of prochymosin. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:135–139. doi: 10.1038/nbt0290-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williamson V M, Bennetzen J, Young E T, Nasmyth K, Hall B. Isolation of the structural gene for alcohol dehydrogenase by genetic complementation in yeast. Nature. 1980;283:214–216. doi: 10.1038/283214a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]