Abstract

Purpose of review:

Environmental chemicals and toxins have been associated with increased risk of impaired neurodevelopment and specific conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Prenatal diet is an individually modifiable factor that may alter associations with such environmental factors. The purpose of this review is to summarize studies examining prenatal dietary factors as potential modifiers of the relationship between environmental exposures and ASD or related neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Recent findings:

Twelve studies were identified; five examined ASD diagnosis or ASD-related traits as the outcome (age at assessment range: 2–5 years) while the remainder addressed associations with neurodevelopmental scores (age at assessment range: 6 months to 6 years). Most studies focused on folic acid, prenatal vitamins, or omega-3 fatty acids as potentially beneficial effect modifiers. Environmental risk factors examined included air pollutants, endocrine disrupting chemicals, pesticides, and heavy metals. Most studies took place in North America. In 10/12 studies, the prenatal dietary factor under study was identified as a significant modifier, generally attenuating the association between the environmental exposure and ASD or neurodevelopment.

Summary:

Prenatal diet may be a promising target to mitigate adverse effects of environmental exposures on neurodevelopmental outcomes. Further research focused on joint effects is needed that encompasses a broader variety of dietary factors, guided by our understanding of mechanisms linking environmental exposures with neurodevelopment. Future studies should also aim to include diverse populations, utilize advanced methods to optimize detection of novel joint effects, incorporate consideration of timing, and consider both synergistic and antagonistic potential of diet.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, nutrition, pregnancy, environmental toxins

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder often diagnosed in early childhood that is characterized by deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors1. In 2018, 1 in 44 (23.0 per 1000) children age 8 years were diagnosed with ASD across 11 sites in the United States (US)2. More broadly, prevalence of any developmental disability among US children age 3–17 was 15% in 2006–20083. Development of ASD, and neurodevelopmental disorders in general, is influenced by a myriad of genetic and environmental factors4, 5.

Prenatal exposure to several classes of environmental chemicals and toxicants has been linked in ASD6, 7. Exposure to air pollutants has been examined in a large number of studies of ASD, with work suggesting increased risk of ASD with prenatal exposure to particulate matter (especially particulate matter less than 2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5)), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone specifically8–11. Prenatal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), bisphenol A (BPA), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and phthalates, have also been linked to impaired neurodevelopment and ASD12 13. Certain pesticides have also been associated with ASD14, and dietary intake is a major route of exposure15. Finally, heavy metals like mercury and lead, as well as metal mixtures16, have also been associated with developmental delays. Various broad mechanisms have been hypothesized for how these environmental factors impact neurodevelopment, including increased oxidative stress and inflammation17, disrupted hormonal signaling18, and altered DNA methylation19.

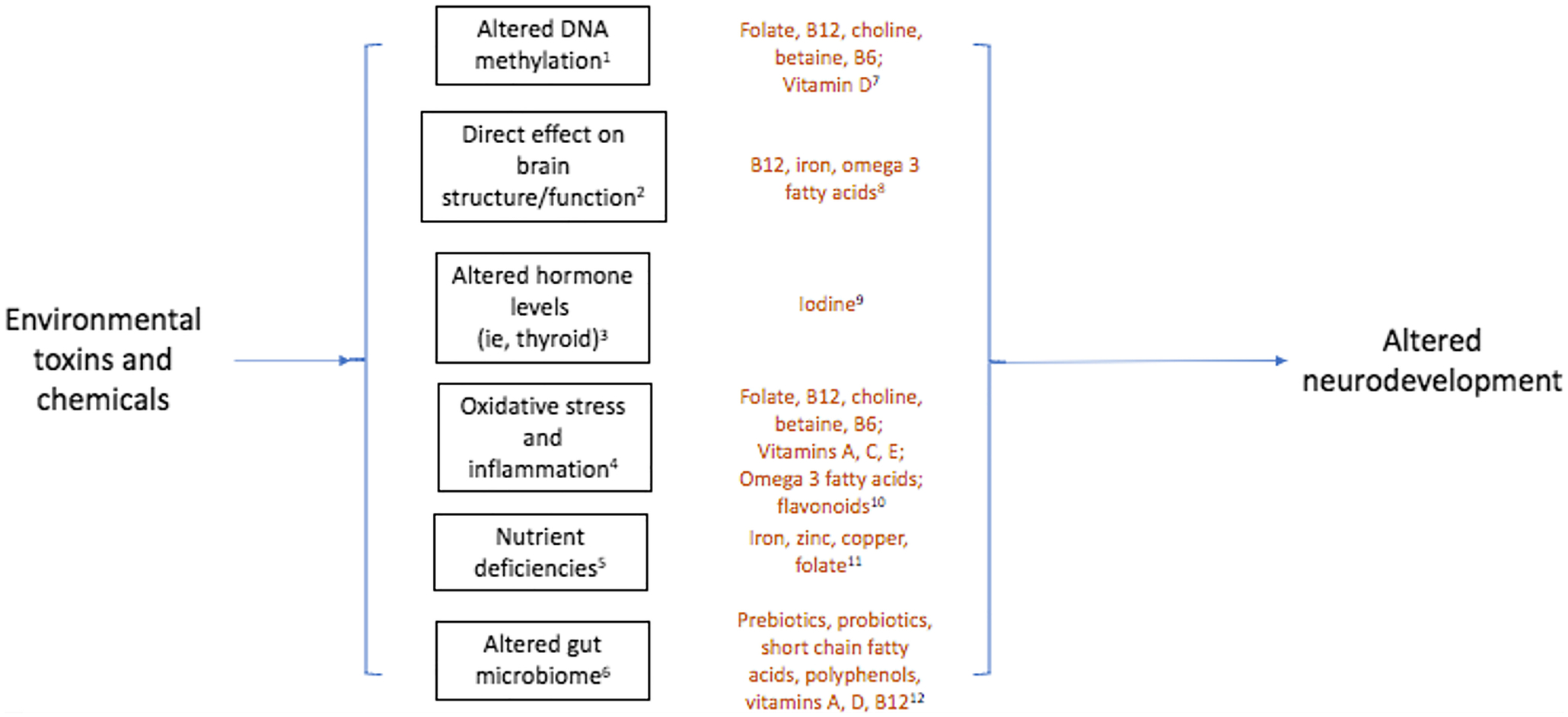

Prenatal diet may be an important modifier of the link between environmental risk factors and risk for ASD or impaired neurodevelopment, given known roles in the same critical pathways affected by above-noted environmental risk factors20–22 (see Figure 1). Modification via dietary factors may occur via protection against or mitigation of the adverse effects of other environmental exposures as a result of adequate or optimal intake, or via synergistic effects due to inadequate intake or presence of adverse components of the diet. Several prenatal dietary factors have been independently associated with ASD and neurodevelopment7, 20, 23, 24 as reviewed elsewhere20, most notably folate, with evidence for an inverse association with neurodevelopmental delays. However, concerns have also been raised related to excess nutrient intake via supplement use, which raise additional questions about how associations may differ across nutrient levels25. In addition, certain foods and food packaging are also a known direct source of exposure to metals and chemicals like phthalates, BPA, and pesticides15, 26, and thus there is also the potential for inherent combined effects within foods containing both potentially beneficial nutrients, as well as potentially harmful chemicals. Given inadequate intake of several neuroprotective nutrients, such as iron, folate, and choline, is common among pregnant women in the United States27, as is suboptimal intake of other foods and nutrients influencing key pathways, clarifying potential modifying effects of these factors is of high public health relevance. Furthermore, because individuals may be able to change their dietary habits more easily than their broad environmental exposures (which often require policy to enact meaningful changes in exposure), the role of diet as a potential modifier is a promising public health target.

Figure 1.

Key pathways that may link environmental exposures, nutrients, and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The aim of this narrative review is to summarize studies examining prenatal diet as a modifier of environmental exposures- specifically, chemicals and toxicants- associated with ASD, in order to guide future work in this area. Given limited prior work on this topic, we also secondarily considered research focused on related neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Methods

A search on PubMed, conducted in the Fall of 2021, was performed to identify research articles examining dietary exposure during pregnancy as a modifier of the risk for ASD or neurodevelopmental outcomes. Developmental outcomes included behavioral and physiological assessments and could be measured at any postnatal age. The primary risk factor must have been prenatal exposure to an environmental chemical or toxicant. Search terms included: pregnan*, maternal, prenatal; environmental, pollutant, endocrine disrupting chemical, pesticide, heavy metal, toxicant; diet*, nutrition, nutrient, food, intake; attenuate*, synergy, moderat*, interaction; autis*, neurodevelopment, developmental, brain development. A complete list of search terms is provided in the Appendix. Only human studies were included. Finally, all studies must have had a comparison group; case studies were not included. Additional papers were identified via a review of reference lists from key articles. Initially, the search was restricted publications to within the past 5 years. However, as only two additional studies were published outside of that range, all studies meeting criteria and published in English before October 27, 2021 were considered.

Current Findings

Autism Spectrum Disorder

We identified 5 studies (all conducted in North America) investigating the role of prenatal diet as a modifier of the relationship between environmental factors and risk for ASD (Table 1). Three studies examined folic acid28–30 and two examined prenatal supplements31, 32. Environmental exposures in these studies included pesticides28, air pollutants29, phthalates30, 31, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)32. Four of the 5 studies used data from California, USA28, 29, 31, 32. Most studies relied on gold standard research measures and/or clinical assessment of diagnosis at 2–5 years of age (median: 3 years). Covariates considered in adjusted models varied across studies (Table 1); all included final adjustment for some proxy for income level; most included child birth year or sex; 2 included adjustment for two other nutrients; 2 for sociodemographic factors; and 2 for pre-pregnancy BMI.

Table 1.

Studies investigating the role of prenatal diet as a modifier of the relationship between environmental factors and ASD.

| Reference | Study design and location | Sample size | Measure of ASD or autistic traits | Prenatal environmental exposure | Prenatal dietary exposure | Covariates | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt et al, 2017 | CHARGE study: case control study of children age 2–5y in California, USA | 516 mother-child pairs (296 ASD, 220 typically developing controls) | ASD diagnosis: Autism Diagnostic Interview, Revised (ADI-R) and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G) | Pesticide exposure: household (none vs any: indoor or outdoor sprays/foggers, pet flea & tick products, any); agricultural (none vs any: chlorpyrifos, organophosphates, pyrethroids, carbamates); and occupational (none vs any). | Reported maternal intake of FA (<800 μg vs ≥800 μg), vitamin B12 (<8 μg vs ≥ 8 μg), and vitamin B6 (<2.83 mg vs ≥ 2.83 mg) from foods or supplements in the first month of pregnancy | Child’s birth year; maternal vitamin B6 and vitamin D intake during 1st month of pregnancy; homeownership | Maternal FA intake attenuated association between ASD and household and agricultural pesticide exposure. Among women who consumed <800 μg FA, the OR (95% CI) for ASD related to any pesticide exposure was 2.1 (1.1, 4.1); among women who consumed ≥800 μg FA, the OR decreased to 1.7 (1.0, 2.9). |

| Goodrich et al, 2018 | CHARGE study | 760 mother-child pairs (434 ASD, 326 typically developing controls) | ASD diagnosis: ADI-R and ADOS-G | Air pollution exposure (near roadway air pollution, PM2.5, PM10, ozone, NO2) using geo-coded addresses, traffic and atmospheric data, and Air Quality System data | Reported maternal intake of FA (≤800 μg vs >800 μg) from foods or supplements in the first month of pregnancy | Child’s birth year; maternal vitamin A and zinc intake during 1st month of pregnancy; self-reported financial hardship | Maternal FA intake attenuated association between ASD and air pollutant exposure. p for interaction significant for NO2 (OR among ≤800 μg FA: 1.53 (0.91, 2.56); OR among >800 μg FA: 0.74 (0.46, 1.19); p: 0.039). |

| Oulhote et al, 2020 | MIREC study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women across Canada | 556 mother-child pairs | Autistic traits measured at 3y using the Social Responsiveness Scale-2 (SRS-2) | Phthalate exposure: phthalate monoester metabolites (MBP, MBzP, MEP, MCPP, sum of DEHP) measured in 1st trimester urine samples | Reported maternal intake of FA (<400 μg vs ≥400 μg) from supplements in the first trimester | Child sex; maternal age, education, parity, marital status, race/ethnicity; year of enrollment; study city; household income | Maternal FA intake attenuated association between ASD and phthalate exposure during pregnancy. p for interaction significant for all phthalates except MEP (p=0.17). |

| Shin et al, 2018 | MARBLES study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women at high risk for delivering a child with ASD in California, USA | 186 pregnant women and their 201 children (46 ASD, 55 non-typically developing, 100 typically developing) | ASD diagnosis: ADOS | Phthalate exposure: weighted averages of 14 phthalate metabolites measured in 2nd and 3rd trimester urine samples | Reported maternal use of prenatal vitamins (yes vs no) in the first month of pregnancy | Child’s birth year; maternal pre-pregnancy BMI; homeownership | Among prenatal vitamin users, ASD risk inversely associated with 3 phthalate metabolites: MiBP (RRR [95% CI]: 0.44 [0.21, 0.88]), MCPP (0.41 [0.20, 0.83]), and MCOP (0.49 [0.27, 0.88]). No association between metabolites and ASD among non-users. |

| Shin et al, 2020 | CHARGE study | 453 mother-child pairs (239 ASD, 214 typically developing controls) | ASD diagnosis: ADI-R and ADOS-G | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) exposure: 9 PFASs modeled based on postnatal maternal serum samples | Reported maternal use of prenatal vitamins (yes vs no) in the 1 month before and after conception | Child sex, age, birth year, gestational age at delivery; maternal age at delivery, parity, race/ethnicity, birthplace, pre-pregnancy BMI; breastfeeding duration; homeownership; study center | Maternal prenatal vitamin use did not modify association between prenatal exposure to PFAs and ASD. |

Abbreviations: EPA - Environmental Protection Agency; MiBP - mono-iso- butyl phthalate; MBP - mono-n-butyl phthalate; MBzP - mono-benzyl phthalate; MEP - mono-ethyl phthalate; MCOP - mono-carboxyisooctyl phthalate; MCPP - mono-3- carboxypropyl phthalate; DEHP - di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate; FA - Folic acid.

Each of the three studies examining maternal folic acid found attenuation of the effects of environmental exposures. Both Schmidt et al and Goodrich et al used data from the Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and the Environment (CHARGE) study, a population-based case-control study in California that enrolled children with diagnosed ASD (age 2–5 years) and age and sex matched typically developing controls. Both used self-reported, retrospective data to estimate maternal folic acid intake from foods and supplements during the first month of pregnancy, and both dichotomized folic acid intake as above or below 800 μg. Schmidt et al examined associations with household, agriculture, or occupational pesticide use, while Goodrich et al investigated the role of air pollutants (NO2, PM2.5, PM10, and ozone). Schmidt et al found that associations with ASD were highest among offspring of women with household and agricultural pesticide exposure and folic acid intake <800 μg/d, compared to those with no pesticide exposure or higher folic acid intake28. Goodrich et al similarly found that offspring of women exposed to higher levels of air pollution along with folic acid intake <800 μg/d had the highest risk of ASD, compared to lower levels of air pollution or higher folic acid intake29. Although this pattern was true for most pollutants, the interaction reached statistical significance only for NO2. Oulhote et al reported similar results for potential modification by folic acid for phthalate exposure using data from the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) Study, a longitudinal cohort study of pregnancy in Canada. The authors found a positive association between maternal urinary phthalate metabolites measured in first trimester urine samples and children’s Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2) scores, a measure of autism-related traits collected at 36–48 months in this study. This association was attenuated among women who consumed >400 μg/d of folic acid supplements in the first trimester according to prospective report30. Of note, although this study used a lower folic acid cutoff compared to the others, it only included intake from supplements.

Two studies examined prenatal supplements as modifiers of the link between environmental exposures and ASD. Shin et al, 2018, used data from the Markers of Autism Risk in Babies – Learning Early Signs (MARBLES) study, a cohort study that enrolled pregnant women at increased familial likelihood for delivering a child with ASD31. Urinary phthalate metabolites were measured during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters and ASD diagnosis was determined on clinical best estimate at 3 years. Reported prenatal vitamin use during the first month of pregnancy (yes/no) was tested as a modifier of associations between 14 phthalate metabolites and ASD, with 4 highly correlated metabolites of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) summed together. Among prenatal supplement users only, 3 metabolites (mono-isobutyl phthalate [MiBP], mono(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate [MCPP], and mono-carboxyisooctyl phthalate [MCOP]) were significantly inversely associated with ASD, although the interaction between prenatal supplement use and phthalates was statistically significant only for MCPP. In Shin et al, 202032, data from the CHARGE study was used, with prenatal exposure to PFAS modeled based on maternal serum PFAS at 2–5 years postpartum. Retrospectively reported prenatal supplement use during the months before and after conception (yes/no) was tested as a modifier of the association between 7 PFAS, considered both as natural-log transformed and untransformed variables, and ASD. PFASs were tested as independent predictors and as multiple predictors in a single model. No significant interactions between prenatal supplement use and any of the PFASs were observed at the p<0.05 level32, nor were stratified odds ratios meaningfully different between prenatal supplement users and non-users. Together, in contrast to findings for folic acid, these studies provide limited evidence for the role of prenatal supplement use as a modifier of associations between these environmental exposures and ASD.

Other neurodevelopmental outcomes

We identified 7 studies (conducted in North America, Africa, South Korea, and Europe) that examined the role of prenatal diet as a modifier of associations between environmental factors and other neurodevelopmental outcomes (Table 2). Two studies examined folic acid33, 34, 2 examined fruit and vegetable intake34, 35, and 3 examined fatty acids36–38. Environmental exposures included heavy metals33, 38, 39, EDCs36, 37, 39, and air pollutants34, 35. Though age at assessment and outcome measures used were more variable than for the studies focused on ASD, five studies measured neurodevelopment within the first 3 postnatal years using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID)33, 35, 36, 38, 39. As for the ASD studies, covariate adjustment varied across studies (Table 2), with few considering the role of other dietary factors, and variability in sociodemographic factors included.

Table 2.

Studies investigating the role of prenatal diet as a modifier of the relationship between environmental factors and neurodevelopment

| Reference | Study design and location | Sample size | Measure of neurodevelopment | Prenatal environmental exposure | Prenatal dietary exposure | Covariates | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al, 2021 | APrON study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Alberta, Canada | 394 mother-child pairs | Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III (BSID-III) at 2y | Bisphenol (BPA and BPS) and cadmium exposure: measured in 2nd trimester maternal urine and red blood cells, respectively | Maternal red blood cell Se and Cu levels during the 2nd trimester | Child sex, ethnicity; household income | Among those with <median Se, BPS negatively associated with BSID-III motor scores. Among those with >median Se, there was a positive association. |

| Kim et al, 2020 | MOCEH study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Seoul, Cheonan, and Ulsan, South Korea | 451 mother-child pairs, categorized as average/slow vs rapid growers | BSID-II at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months | Mercury exposure: measured in maternal blood during late pregnancy (28–42 weeks gestation) and in cord blood samples | Serum folate (above vs below median), measured in early pregnancy (12–20 weeks gestation) | Child sex, gestational age; maternal age, education, pre-pregnancy BMI, drinking history, occupation; duration of breast feeding; household income | Maternal folate modified association between mercury and neurodevelopment for rapid growers. Among those with <median folate, maternal and cord blood mercury was negatively associated with BSID-II scores. No association among those with >median serum folate. |

| Loftus et al, 2019 | CANDLES study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Shelby County, Tennessee, USA | 1005 mother-child pairs | Stanford Binet Intelligence Scales, edition 5 (SB-5) at 4–6y | Air pollution exposure (PM10, NO2) using geo-coded addresses and Air Quality System data | Reported maternal intake of fruits and vegetables (below vs above median, measured by food frequency questionnaire) and maternal plasma folate quartile during the 2nd trimester | Child sex, age, date of birth, birth order; maternal age, race, education, IQ; prenatal depression, smoking; breastfeeding duration; child sleep; insurance status; Childhood Opportunity Index | PM10 exposure inversely associated with Full Scale IQ for those in lowest quartile of maternal plasma folate (−6.8 points [95% CI: 1.4, 12.3] per 5 unit increase in PM10). No association among those in the highest quartiles. |

| Merida-Ortega et al, 2019 | Longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Mexico | 276 mother-child pairs | BSID-II at 1–30 mos | DDT exposure: measured during 1st trimester as DDE in maternal serum | Dietary intake of fatty acids (ALA, EPA, DPA, DHA, LA, ARA; above vs below median) during 1st and 3rd trimesters, as measured by a food frequency questionnaire | Child sex, age; maternal IQ, energy intake; duration of breastfeeding; Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment scale | No significant interactions of any fatty acid and maternal serum DDE on BSID-II scores. |

| Ogaz-Gonzalez et al, 2018 | Longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Mexico | 142 mother-child pairs | McCarthy Scales of Children’s Ability at 42–60 months | DDT exposure: measured during 3rd trimester as DDE in maternal serum | Dietary intake of fatty acids (ALA, EPA, DPA, DHA, LA, ARA; above vs below median) during 1st and 3rd trimesters, as measured by a food frequency questionnaire | Child sex, age; maternal IQ, energy intake; duration of breastfeeding; HOME scale | DHA intake in 1st trimester and ARA intake in 3rd trimester were modifiers of association of DDE with motor and memory development, respectively. Among women with <median intake for DHA and ARA, serum DDE inversely associated with neurodevelopment. |

| Strain et al, 2015 | Seychelles Child Development Study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in the Republic of Seychelles | 1265 mother-child pairs | BSID-II, Infant Behavior Record-Revised, MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDI) at 20 months | Mercury exposure: measured in maternal hair samples at delivery | Serum fatty acids (ALA, EPA, DHA, LA, ARA) collected at 28 weeks gestation, categorized into tertiles of total n3, n6, and their ratio | Child sex, age; maternal age; socioeconomic status; number of parents living with the child | Total n3s and n6:n3 ratio modified the association between mercury and psychomotor development (p for interaction <0.05). Among those in the highest tertile of n3s, mercury was positively associated with motor development. Among those in the highest tertile of the n6:n3 ratio, mercury was negatively associated with motor development. No associations among those in lower tertiles. |

| Guxens et al, 2012 | INMA study: longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women in Spain | 1889 mother-child pairs | BSID at 14 months | Air pollution exposure (NO2, benzene) using passive samplers and land use regression models | Reported maternal intake of fruits and vegetables (low tertile vs medium/high tertile, as measured by FFQ) during the 1st trimester and maternal plasma vitamin D (season-specific tertiles) | Child’s sex, age, number of siblings; maternal age, education, height, pre-pregnancy BMI, prenatal alcohol use, consumption of fish in 1st trimester; use of gas stove; and evaluating psychologist. | Maternal intake of fruits and vegetables modified the association between NO2 and benzene and mental development (p for interaction = 0.073 and 0.047, respectively). Among those with low intake, air pollutants negatively associated with mental development. Results similar but not statistically significant for maternal vitamin D status. |

Abbreviations: Se- selenium; Cu- copper; FFQ- Food Frequency Questionnaire; HOME- Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment.

A study by Liu et al in Canada examined several prenatal nutrients as potential modifiers of associations between bisphenols A and S (BPA and BPS) and neurodevelopment using data from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort study39. The Bayley III scales were used to assess child neurodevelopment at age 2 years. Maternal levels of BPA and BPS were measured in 2nd trimester urine samples, and arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury, and several nutrients (serum ferritin, plasma vitamin B12, red blood cell folate, dietary choline, serum phospholipid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid, and plasma copper, zinc, manganese, and selenium) were measured in 2nd trimester blood samples. A statistically significant interaction between BPS and selenium in association with motor development was identified (p for interaction 0.026). Among offspring of women with selenium levels below the median, higher BPS was associated with poorer motor development; among those with selenium above the median, higher BPS was associated with improved motor development39. Modification by copper and cadmium was also examined, but not identified; other nutrients and metals were not assessed as modifiers.

Two studies found that maternal serum or plasma folate significantly modified associations between environmental factors and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Kim et al used data from a longitudinal study in South Korea, Mothers and Children’s Environmental Health (MOCEH), to examine serum folate as a modifier of mercury exposure33. Maternal serum folate was measured in early pregnancy (12–20 weeks gestation), and blood mercury in late pregnancy (28–42 weeks gestation) and in cord blood. Children’s neurodevelopment was assessed with the BSID-II at 6–36 months. Additionally, children were categorized as average/slow growers and rapid growers based on a change in weight z-score >0.67 from birth to 36 months. Among rapid-growing offspring of women with serum folate below the median, blood mercury was negatively associated with neurodevelopment, whereas there was no association among women with higher serum folate. Although this pattern was observed in stratified models of maternal and cord blood mercury with mental and psychomotor development scores, the interaction reached statistical significance only for folate and cord blood mercury in association with psychomotor development33. In Loftus et al, maternal plasma folate during the 2nd trimester was tested as a modifier of the relationship between prenatal air pollutant exposure and child IQ34. Using data from the Conditions Affecting Neurocognitive Development and Learning in Early Childhood (CANDLE) cohort, they found a borderline significant interaction (p=0.07) as well as a significant negative association between PM10 and Full Scale IQ only among those in the lowest quartile of plasma folate.

Two studies (one of which also examined folate, as noted above) found conflicting results when examining maternal intake of fruits and vegetables as a modifier of environmental exposures. In Loftus et al, maternal intake of fruits and vegetables (above or below the median) in early pregnancy was not a significant modifier of air pollutants (PM10 or NO2) in association with intelligence scores as assessed by the Stanford Binet scales34. However, Guxens et al reported a significant interaction between fruit and vegetable intake and air pollution exposure using data from the Spanish Infancia y Medio Ambiente (INMA) Project35. Among offspring of women in the lowest tertile of fruit and vegetable intake during pregnancy, both NO2 and benzene were inversely associated with the BSID mental development score, while no association was observed among offspring of women in the mid or high tertiles.

Three studies examined the role of maternal long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) as modifiers of environmental exposures. PUFAs include omega 3 fatty acids (α-linoleic acid, eicosapentanoic acid, docosapentanoic acid, and DHA) and the omega 6 fatty acids (linoleic acid and arachidonic acid). Strain et al used data from the longitudinal Seychelles Child Development Study to examine effect modification related to mercury exposure38. Total omega 3, total omega 6, and the ratio of total omega 6:omega 3 fatty acids measured in mid-pregnancy maternal serum were tested as modifiers of the relationship between prenatal mercury exposure and neurodevelopment at 20 months. Although there was no overall association between mercury exposure and child cognitive scores, PUFAs were identified as significant modifiers. In the highest tertile of omega 3 levels, mercury was positively associated with psychomotor development, whereas in the highest tertile of the omega 6:omega 3 ratio, mercury was negatively associated with psychomotor development. There were no associations in the lower tertiles38. Two studies examined maternal fatty acid intake as a modifier of prenatal exposure to the pesticide 1,1,1- trichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane (DDT) and child neurodevelopment in the same longitudinal cohort study of Mexican women36, 37. Fatty acid intake and DDT exposure (as its main metabolite, 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl) ethylene (DDE)) were each measured during the 1st and 3rd trimesters. Child development was measured using the BSID-II at 1–30 months and the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Ability at 42–60 months. Using DDE levels during the 1st trimester and BSID-II scores, Merida-Ortega et al did not find significant modification by any dietary fatty acid36. However, using DDE levels during the 3rd trimester and McCarthy scores, Ogaz-Gonzalez et al found evidence for modification by two PUFAs37. Among those with 1st trimester DHA intake below the median, DDE levels were inversely associated with motor development; the association was null for those with DHA intake above the median. A similar relationship was found between arachidonic acid intake during the 3rd trimester and memory development (p for interaction with DDE for both fatty acids <0.05)37.

Discussion

In this review, we found evidence supporting a role for several prenatal dietary factors as modifiers of relationships between environmental chemicals and ASD and broader neurodevelopment. Folic acid and long chain omega-3 fatty acids, in particular, were found to attenuate associations with environmental exposures and ASD or neurodevelopmental scores in multiple studies. Less evidence was observed for a modifying role of other dietary factors examined, including prenatal supplements and maternal fruit and vegetable intake. Although the number of studies identified that focus on this topic is limited, available data suggest interactions between dietary factors and environmental exposures is a promising target for future work. To our knowledge, this is the first review focused on the joint effects of diet and environmental exposures in relationship to ASD and neurodevelopment, and we believe this highlights a need in the field for growing work in this area given the likelihood of convergence of effects in shared pathways.

Folic acid is a form of the essential nutrient folate that is used in fortified foods and supplements. In the US, women of reproductive age are recommended to consume 400 μg of folic acid per day to prevent birth defects40; to meet this recommendation, folic acid is added to refined grains such as bread and cereal. Folic acid intake during the periconceptional period has been directly associated with decreased risk of ASD7, 20; in this review, folic acid was also identified as a modifier of the relationship between several environmental exposures (including air pollutants, metals, pesticides and pthathates) and ASD and neurodevelopment in several studies. There are two main hypotheses for how folic acid may attenuate the effects of environmental exposures. First, folate’s role as a methyl donor may counteract the effects of environmental toxins on DNA methylation. Folate works with vitamin B12 to donate a methyl group to homocysteine, forming methionine and then S-adenosyl-methionine, a major methyl donor. In rodent models, perinatal BPA provision induces changes in DNA methylation patterns and behavioral deficits among offspring, and these changes are reversed with perinatal provision of a combination of methyl donors (folic acid, vitamin B12, choline, and betaine)41. Second, folate may act as an antioxidant to mitigate toxin-associated oxidative stress and inflammation. Folic acid may have direct antioxidant properties42. Additionally, folate’s involvement in the methionine cycle is linked to the creation of cysteine (a reaction which requires vitamin B6) and then glutathione, a major antioxidant in the body. In rodent models, gestational exposure to air pollutants promotes neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, which can be attenuated with prenatal provision of folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin B643. Direct evidence for the mechanisms by which folic acid attenuates the effects of environmental toxins is lacking in human studies.

In the identified studies, folic acid exposure was measured in two ways: maternal self-report of folic acid supplementation during the periconceptional period28–30 and maternal plasma/serum folate in the second trimester33, 34. Both measures were associated with reduced risk for ASD or impaired neurodevelopment according to environmental exposures. However, folic acid and folate are distinct compounds and are metabolized differently in the body. Some concern has been raised that high intake of folic acid from supplements throughout pregnancy may lead to accumulation of unmetabolized folic acid in the blood, and that this may be linked to increased likelihood of ASD44; thus, future studies further addressing potential differences in dose-response across pregnancy may be warranted.

Compared to folic acid, the evidence for modification by prenatal supplement use or intake of fruits and vegetables was relatively weaker, though fewer studies addressed these factors. Prenatal supplements and fruits and vegetables are rich sources of folic acid and natural folate, respectively, and also contain other neuroprotective compounds. It is possible that the combination of compounds may alter the specific effects as a modifier, or that differences in social or demographic factors influencing intake of these, play into these findings. The contrasting findings observed across the two studies addressing fruit and vegetable intake as a modifier of air pollution effects on neurodevelopment specifically may also be related to differences in populations, measurement of air pollutants, definition of intake categories, or outcome measures (IQ at 4–6 years in Loftus et al vs BSID score at 14 months in Guxens et al). In addition, it is worth noting considerations regarding timing; periconceptional or first month of pregnancy supplement use may also be a marker for pregnancy intent, and thereby serve as a proxy for a host of health-related factors that could also influence neurodevelopment. While most studies of folic acid and supplement use have focused on this periconceptional period, the limited studies on fruit and vegetable intake have generally not done so.

Other dietary factors also showed limited evidence for modification of exposure associations with neurodevelopmental outcomes. PUFAs are important for cell membrane structure, cell signaling, and neuronal development45 and have been suggested as protective factors in some studies for ASD and neurodevelopment23, 46. In this review, certain PUFAs were identified as modifiers of the effects of environmental exposures, though results varied across the three studies that examined maternal fatty acids. Whereas Ogaz-Gonzalez et al and Strain et al reported significant moderation by fatty acids, the specific PUFAs and the direction of the associations differed; on the other hand, Merida-Ortega et al found no evidence for modification by any PUFA. Differences across these studies could relate to different environmental exposures and/or differences in PUFA intake across study populations (in comparing Strain et al to the others), or differences in outcome timing and assessment (in comparing the two Mexican cohort studies). In Ogaz-Gonzalez et al, intake of omega 3 fatty acids was relatively low (~30 mg/day of DHA during the 3rd trimester)37, far below the recommended intake of 200 mg/day during pregnancy47. Conversely, on the island nation of the Seychelles, women consumed fish (a rich source of omega 3 fatty acids) at 8.5 meals per week on average38. It is possible that various PUFAs are able to act as modifiers only at certain intake levels.

Mechanisms that may underly PUFAs as modifiers of environmental exposures may be related to their roles in gene expression, antioxidation and inflammation, and/or direct incorporation into brain cell membranes. PUFAs may regulate gene expression in the brain by interacting with transcription factors48 or by influencing gene methylation. For example, prenatal provision of DHA influences methylation of genes related to infant growth and immune development49, 50. PUFAs may also be metabolized into bioactive lipids which influence inflammation and oxidation; for example, provision of omega 3 fatty acids during pregnancy has been shown to reduce markers of oxidation in mothers and newborns51. Further, the balance of DHA and ARA in early life is thought to be important for optimal neurodevelopment52.

Finally, vitamin D and selenium were examined as potential modifiers in only one study each. Although vitamin D was not a significant modifier of air pollution associations in Guxens et al35, maternal vitamin D deficiency was shown to alter DNA methylation across two generations in rodent models53, and has been associated with increased ASD in several studies20, 54. Vitamin D is also a known immune moderator55, and should thus be further considered in future work for potential joint effects in this pathway in particular. Selenium is a trace element that is required by a range of proteins involved in antioxidation, thyroid function, and DNA synthesis. Liu et al found that maternal selenium levels modified the association between the bisphenol BPS and motor development39. Given connections to gene methylation and antioxidation56, further study of Se and related nutrients is also warranted.

Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Directions

Although promising, the field is currently limited by a fairly narrow scope of dietary factors considered and, particularly for studies focused on ASD, relatively geographically homogeneous samples. All of the reports identified were observational studies. In the case control studies, there may be concerns regarding recall bias, or measurement error in dietary factors and supplements reported several years after pregnancy. Studies also face concerns regarding potential residual confounding by health-related behaviors that can be challenging to capture, or by other dietary factors not considered but involved in similar pathways. As summarized in our Tables, varying degrees of adjustment for demographic and sociodemographic factors, often tied to both diet and environmental exposures, have been considered across studies and represent an area for improved attention in future work. All but three studies used data from North America, and most studies took place in high-income countries. Populations in lower income countries are at higher risk of developmental delays57, in part related to poor maternal nutrition status and harmful environmental exposures58 59, and therefore conducting this work in ethnically and geographically diverse study populations is needed to better understand joint effects. The role of gene-environment and gene-nutrient interactions60, several of which have already been linked to autism risk61, 62, in these joint effect studies also represents an area of need, though these will require large samples. Likewise, while the focus of this review was on potential modification of the effects of environmental exposures in the narrow sense, a broader scope of exposures, such as gestational diabetes63 and other conditions that act on these common pathways, should also be considered for potential joint effects.

As noted, this field would benefit from the investigation of a wider variety of dietary factors, guided by advancements in our understanding of mechanisms. For example, maternal iodine status, with its connection to thyroid function, may be a likely candidate for effect modification of EDCs, which disrupt thyroid signaling pathways18. Choline, a methyl donor that can (as an alternative to folate) convert homocysteine to methionine via its metabolite betaine, should be examined for interactions with exposures demonstrating modification by folate. High doses of choline have been shown to reverse oxidative stress markers among chick embryos exposed to dibutyl phthalate64. Maternal choline consumption has also been shown to improve behavioral deficits in mouse models of autism65. Vitamin E may modify exposures in oxidative and inflammatory pathways; it is a fat soluble antioxidant, and has been shown to be a modifier of neurologic outcomes associated with the phthalate DEHP in adult mice66. In addition, pre- and probiotics may influence the composition of the gut microbiota, which has been linked to neuroinflammation and development of ASD67, and flavonoids can act as neuroprotective phytochemicals68. These factors have not been examined as modifiers of environmental associations with ASD and neurodevelopment to our knowledge. Relatedly, certain nutrients may also act as mediators of associations; it has been suggested that the inflammation caused by environmental toxins leads to prenatal deficiencies of nutrients affected by the acute phase response (iron, zinc, copper), and that these deficiencies contribute to ASD risk24, 69.

We identified no studies that investigated potential antagonistic or negative effects of the diet in association with these exposures and outcomes; thus, consideration of pro-inflammatory dietary factors, dietary patterns, and diet as a source of exposures, should be considered. Similarly, while not included in this review, investigation of single foods as sources of both protective and risk factors merits discussion. Maternal intake of fish, for example, serves as a source of both environmental toxins (mercury) and dietary protective factors (fatty acids, selenium, etc), and has been examined in studies of cognitive scores70 and linked to ASD-related traits71, 72. Fruits and vegetables are also sources of environmental toxins (ie, pesticides15) as well as beneficial nutrients. When canned or packaged, these nutritious foods may also expose consumers to BPA or phthalates. The study of whole foods may help clarify how these positive and negative factors relate to neurodevelopment and ASD when combined.

The studies reviewed here employed standard methods for identification of joint effects (interaction terms and stratified models). Use of mixture modeling approaches73, 74 may be useful in advancing the field in identification of novel individual associations and interactions in the face of many correlated exposures, while approaches designed to examine time window effects73, 75, 76 may improve detection for nutrients with more specific critical windows. A number of studies of combined effects of metals (often including lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, etc)77–80 have implemented such techniques and may be useful models. Several studies have identified novel interactions using these methods for other exposures and outcomes79, 81. One study found suggestive evidence for an interaction but not independent effects, between selenium and arsenic in relationship to autistic traits as measured by the SRS82. Thus, examination of combined effects of nutrients and foods using mixtures approaches may reveal associations and interactions with ASD-related outcomes, even where interrogation of individual factors has failed to do so.

Finally, given similarities in risk factors for ASD and other neurodevelopmental outcomes, studying a range of outcomes may help to more fully understand relationships between nutrition, environment, and neurodevelopment, and determine specificity vs generalizability of effects across neurodevelopmental diagnoses. In addition, incorporation of quantitative traits, may also help to inform on associations with severity of symptoms and add to understanding of the nature of relationships, particularly if quantitative traits that are strong markers of heritability can be used.

Conclusion

Although currently limited in number, the available studies suggest a role for prenatal dietary factors (especially folic acid and fatty acids) as protective modifiers of the link between environmental chemicals and ASD and broader neurodevelopment. Replication of findings in diverse contexts and with powerful study designs is required. Investigation of other nutrients and dietary patterns, guided by understanding of mechanisms10, will help advance the field. Alteration of maternal diet is a promising public health target for reducing risk of adverse effects related to environmental exposures.

Supplementary Material

Funding acknowledgements:

This work was supported by funding from the NIEHS under grant #R01 ES032469-01A1 (Lyall, Volk) and P30 ES000002 (Hart).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This AM is a PDF file of the manuscript accepted for publication after peer review, when applicable, but does not reflect post-acceptance improvements, or any corrections. Use of this AM is subject to the publisher’s embargo period and AM terms of use. Under no circumstances may this AM be shared or distributed under a Creative Commons or other form of open access license, nor may it be reformatted or enhanced, whether by the Author or third parties. See here for Springer Nature’s terms of use for AM versions of subscription articles: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/accepted-manuscript-terms

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent: All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed ed. Washington, D.C. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep MMWR. 2021; 70: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics. 2011; 127: 1034–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, et al. The changing epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017; 38: 81–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68: 1095–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bölte S, Girdler S and Marschik PB. The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019; 76: 1275–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyall K, Schmidt RJ and Hertz-Picciotto I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43: 443–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun HK, Leung C, Wen SW, McDonald J and Shin HH. Maternal exposure to air pollution and risk of autism in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2020; 256: 113307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imbriani G, Panico A, Grassi T, et al. Early-life exposure to environmental air pollution and autism spectrum disorder: A review of available evidence. Int J Environ Res. 2021; 18: 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X, Rahman MM, Wang Z, et al. Evidence of susceptibility to autism risks associated with early life ambient air pollution: A systematic review. Environ Res. 2021; 208: 112590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman MM, Shu YH, Chow T, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Air Pollution and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Sensitive Windows of Exposure and Sex Differences. Environ Health Perspect. 2022; 130: 17008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nesan D and Kurrasch DM. Gestational exposure to common endocrine disrupting chemicals and their impact on neurodevelopment and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020; 82: 177–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radke EG, Braun JM, Nachman RM and Cooper GS. Phthalate exposure and neurodevelopment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of human epidemiological evidence. Environ Int. 2020; 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He X, Tu Y, Song Y, Yang G and You M. The relationship between pesticide exposure during critical neurodevelopment and autism spectrum disorder: A narrative review. Environ Res. 2021; 203: 111902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riederer AM, Bartell SM, Barr DB and Ryan PB. Diet and nondiet predictors of urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid in NHANES 1999–2002. Environ Health Perspect. 2008; 116: 1015–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merced-Nieves FM, Arora M, Wright RO and Curtin P. Metal mixtures and neurodevelopment: Recent findings and emerging principles. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2021; 26: 28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei H, Feng Y, Liang F, et al. Role of oxidative stress and DNA hydroxymethylation in the neurotoxicity of fine particulate matter. Toxicology. 2017; 380: 94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghassabian A and Trasande L. Disruption in thyroid signaling pathway: A mechanism for the effect of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on child neurodevelopment. Front Endocrinol. 2018; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keil KP and Lein PJ. DNA methylation: A mechanism linking environmental chemical exposures to risk of autism spectrum disorders? Environ Epigenetics. 2016; 2: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

20.Zhong C, Tessing J, Lee BK and Lyall K. Maternal dietary factors and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of existing evidence. Autism Res. 2020; 13: 1634–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

Scoping review of maternal prenatal dietary factors associated with ASD.

Found strongest evidence for an inverse association between maternal folic acid supplementation and ASD; results were suggestive for vitamin D and less consistent for polyunsaturated fatty acids, and insufficient work conducted for other nutrients.

- 21.Kannan S, Misra DP, Dvonch JT and Krishnakumar A. Exposures to airborne particulate matter and adverse perinatal outcomes: a biologically plausible mechanistic framework for exploring potential effect modification by nutrition. Environ Health Perspect. 2006; 114: 1636–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barthelemy J, Sanchez K, Miller MR and Khreis H. New opportunities to mitigate the burden of disease caused by traffic related air pollution: antioxidant-rich diets and supplements. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyall K, Munger KL, O’Reilly ÉJ, Santangelo SL and Ascherio A. Maternal dietary fat intake in association with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 2013; 178: 209–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt RJ, Tancredi DJ, Krakowiak P, Hansen RL and Ozonoff S. Maternal intake of supplemental iron and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 180: 890–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey RL, Pac SG, Fulgoni III VL, Reidy KC and Catalano PM. Estimation of total usual dietary intakes of pregnant women in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019; 2: e195967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacyga DC, Sathyanarayana S and Strakovsky RS. Dietary predictors of phthalate and bisphenol exposures in pregnant women. Adv Nutr. 2019; 10: 803–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey RL, Pac SG, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Reidy KC and Catalano PM. Estimation of Total Usual Dietary Intakes of Pregnant Women in the United States. JAMA network open. 2019; 2: e195967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

28.Schmidt RJ, Kogan V, Shelton JF, et al.

Combined prenatal pesticide exposure and folic acid intake in relation to autism spectrum disorder. Environ Health Perspect. 2017; 125: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine joint effects of folic acid and an environmental exposure in association with ASD.

Found evidence for modification of the association between pesticide exposure and ASD by folate.

-

29.Goodrich AJ, Volk HE, Tancredi DJ, et al.

Joint effects of prenatal air pollutant exposure and maternal folic acid supplementation on risk of autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2018; 11: 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine joint effects of folic acid and air pollution in association with ASD.

Found evidence for attenuation of the association between prenatal air pollution exposure and ASD by folic acid supplementation.

-

30.Oulhote Y, Lanphear B, Braun JM, et al.

Gestational exposures to phthalates and folic acid, and autistic traits in Canadian children. Environ Health Perspect. 2020; 128: 27004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine joint effects of folic acid and prenatal phthalate exposure in association with ASD-related traits.

Found evidence for attenuation of the association between prenatal phthalate exposure and ASD-related traits by folic acid.

- 31.Shin H-M, Schmidt RJ, Tancredi D, et al. Prenatal exposure to phthalates and autism spectrum disorder in the MARBLES study. Environ Health. 2018; 17: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin H-M, Bennett DH, Calafat AM, Tancredi D and Hertz-Picciotto I. Modeled prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in association with child autism spectrum disorder: a case control study. Environ Res. 2020; 186: 109514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim B, Shah S, Park HS, et al. Adverse effects of prenatal mercury exposure on neurodevelopment during the first 3 years of life modified by early growth velocity and prenatal maternal folate level. Environ Res. 2020; 191: 109909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

34.Loftus CT, Hazlehurst MF, Szpiro AA, et al.

Prenatal air pollution and childhood IQ: preliminary evidence of effect modification by folate. Environ Res. 2019; 176: 108505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

Examined modification of association between air pollution exposure and child intelligence scores by maternal 2nd trimester plasma folate and by reported fruit and vegetable intake.

Evidence of attenuation of effects by folate; decreases in IQ scores with higher PM10 exposure were seen for those with low prenatal folate but not for those with higher folate.

-

35.Guxens M, Aguilera I, Ballester F, et al.

Prenatal exposure to residential air pollution and infant mental development: modulation by antioxidants and detoxification factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2012; 120: 144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine joint effects of prenatal dietary factors and air pollution on child neurodevelopment.

Found evidence for stronger adverse effects of air pollution exposure on cognitive scores among those with low fruit and vegetable and vitamin D intake.

-

36.Mérida-Ortega Á, Rothenberg SJ, Torres-Sánchez L, et al.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids and child neurodevelopment among a population exposed to DDT: A cohort study. Environ Health: Glob Access Sci Source. 2019; 18: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

Examined modification of pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment by PUFAs.

Did not find evidence of interactions.

-

37.Ogaz-González R, Mérida-Ortega Á, Torres-Sánchez L, et al.

Maternal dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids modifies association between prenatal DDT exposure and child neurodevelopment: A cohort study. Environ Pollut. 2018; 238: 698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine modification of prenatal pesticide exposure-neurodevelopment association by PUFAs.

Found evidence for attenuation of effects of prenatal exposure to the pesticide DDE by the PUFAs DHA and ARA; inverse association between prenatal DDE exposure and cognitive scores found only among those with <median intake of these PUFAs.

- 38.Strain JJ, Yeates AJ, Van Wijngaarden E, et al. Prenatal exposure to methyl mercury from fish consumption and polyunsaturated fatty acids: Associations with child development at 20 mo of age in an observational study in the Republic of Seychelles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015; 101: 530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

39.Liu J, Martin LJ, Dinu I, Field CJ, Dewey D and Martin JW. Interaction of prenatal bisphenols, maternal nutrients, and toxic metal exposures on neurodevelopment of 2-year-olds in the APrON cohort. Environ Int

2021; 155: 106601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];

First study to examine the relationships between cognitive scores and levels of prenatal bisphenols, maternal nutrients, and metals, measured in maternal biosamples, considering interactions of these factors.

Found evidence for modification of effects of BPA and BPS exposure by selenium on cognitive scores, with protective effects of selenium.

- 40.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, D.C.1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolinoy DC, Huang D and Jirtle RL. Maternal nutrient supplementation counteracts bisphenol A-induced DNA hypomethylation in early development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104: 13056–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshi R, Adhikari S, Patro BS, Chattopadhyay S and Mukherjee T. Free radical scavenging behavior of folic acid: evidence for possible antioxidant activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001; 30: 1390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang T, Zhang T, Sun L, et al. Gestational B-vitamin supplementation alleviates PM2.5-induced autism-like behavior and hippocampal neurodevelopmental impairment in mice offspring. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019; 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiens D and DeSoto MC. Is high folic acid intake a risk factor for autism? A review. Brain Sci. 2017; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao D, Kevala K, Kim J, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes hippocampal neuronal development and synaptic function. J Neurochem. 2009; 111: 510–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calder PC. Very long-chain n-3 fatty acids and human health: Fact, fiction and the future. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018; 77: 52–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition: report of an expert consultation. Rome, Italy: 2010, p. 1–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitajka K, Sinclair AJ, Weisinger RS, et al. Effects of dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on brain gene expression. PNAS. 2004; 101: 10931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee H-S, Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernandez-Vargas H, et al. Modulation of DNA methylation states and infant immune system by dietary supplementation with omega-3 PUFA during pregnancy in an intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013; 98: 480–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee H-S, Barraza-Villarreal A, Biessy C, et al. Dietary supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acid during pregnancy modulates DNA methylation at IGF2/H19 imprinted genes and growth of infants. Physiol Genomics. 2014; 46: 851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kajarabille N, Hurtado JA, Pena-Quintana L, et al. Omega-3 LCPUFA supplement: a nutritional strategy to prevent maternal and neonatal oxidative stress. Matern Child Nutr. 2017; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colombo J, Shaddy DJ, Kerling EH, Gustafson KM and Carlson SE. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA) balance in developmental outcomes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2017; 121: 52–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue J, Schoenrock SA, Valdar W, Tarantino LM and Ideraabdullah FY. Maternal vitamin D depletion alters DNA methylation at imprinted loci in multiple generations. Clin Epigenetics. 2016; 8: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vinkhuyzen AAE, Eyles DW, Burne THJ, et al. Gestational vitamin D deficiency and autism spectrum disorder. BJPsych Open. 2017; 3: 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becker KG. Autism, immune dysfunction and Vitamin D. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011; 124: 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Speckmann B and Grune T. Epigenetic effects of selenium and their implications for health. Epigenetics. 2015; 10: 179–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017; 389: 77–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker SP, Wachs TD, Grantham-McGregor S, et al. Inequality in early childhood: risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet. 2011; 378: 1325–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson LM. Household air pollution from cooking fires Is a global problem. Am J Nurs. 2019; 119: 61–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ritz BR, Chatterjee N, Garcia-Closas M, et al. Lessons learned from past gene-environment interaction successes. Am J Epidemiol. 2017; 186: 778–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Volk HE, Kerin T, Lurmann F, Hertz-Picciotto I, McConnell R and Campbell DB. Autism spectrum disorder: interaction of air pollution with the MET receptor tyrosine kinase gene. Epidemiology. 2014; 25: 44–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt RJ, Hansen RL, Hartiala J, et al. Prenatal vitamins, one-carbon metabolism gene variants, and risk for autism. Epidemiology. 2011; 22: 476–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jo H, Eckel SP, Chen J-C, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus, prenatal air pollution exposure, and autism spectrum disorder. Environ Int. 2019; 133: 105110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang R, Sun DG, Song G, et al. Choline, not folate, can attenuate the teratogenic effects ofdibutyl phthalate (DBP) during early chick embryo development. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019; 26: 29763–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langley EA, Krykbaeva M, Blusztajn JK and Mellott TJ. High maternal choline consumption during pregnancy and nursing alleviates deficits in social interaction and improves anxiety-like behaviors in the BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J mouse model of autism. Behav Brain Res. 2015; 278: 210–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang J, Yuan Y, Wei C, et al. Neurobehavioral changes induced by di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and the protective effects of vitamin E in Kunming mice. Toxicol Res. 2015; 4: 1006–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lombardi VC, De Meirleir KL, Subramanian K, et al. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota; future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018; 61: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spencer JP. Flavonoids and brain health: multiple effects underpinned by common mechanisms. Genes Nutr. 2009; 4: 243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nuttall JR. The plausibility of maternal toxicant exposure and nutritional status as contributing factors to the risk of autism spectrum disorders. Nutr Neurosci. 2017; 20: 209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Amarasiriwardena C, et al. Maternal prenatal fish consumption and cognition in mid childhood: mercury, fatty acids, and selenium. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016; 57: 71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vecchione R, Vigna C, Whitman C, et al. The Association Between Maternal Prenatal Fish Intake and Child Autism-Related Traits in the EARLI and HOME Studies. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2021; 51: 487–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Julvez J, Mendez M, Fernandez-Barres S, et al. Maternal Consumption of Seafood in Pregnancy and Child Neuropsychological Development: A Longitudinal Study Based on a Population With High Consumption Levels. Am J Epidemiol. 2016; 183: 169–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu SH, Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, et al. Bayesian varying coefficient kernel machine regression to assess neurodevelopmental trajectories associated with exposure to complex mixtures. Stat Med. 2018; 37: 4680–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, Valeri L and Coull BA. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ Health. 2018; 17: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bello GA, Arora M, Austin C, Horton MK, Wright RO and Gennings C. Extending the Distributed Lag Model framework to handle chemical mixtures. Environ Res. 2017; 156: 253–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Buckley JP, Hamra GB and Braun JM. Statistical Approaches for Investigating Periods of Susceptibility in Children’s Environmental Health Research. Current environmental health reports. 2019; 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang M, Liu C, Li WD, et al. Individual and mixtures of metal exposures in associations with biomarkers of oxidative stress and global DNA methylation among pregnant women. Chemosphere. 2022; 293: 133662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cowell W, Colicino E, Levin-Schwartz Y, et al. Prenatal metal mixtures and sex-specific infant negative affectivity. Environ Epidemiol. 2021; 5: e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valeri L, Mazumdar MM, Bobb JF, et al. The Joint Effect of Prenatal Exposure to Metal Mixtures on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 20–40 Months of Age: Evidence from Rural Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect. 2017; 125: 067015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bauer JA, Devick KL, Bobb JF, et al. Associations of a Metal Mixture Measured in Multiple Biomarkers with IQ: Evidence from Italian Adolescents Living near Ferroalloy Industry. Environ Health Perspect. 2020; 128: 97002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vilahur N, Bustamante M, Byun HM, et al. Prenatal exposure to mixtures of xenoestrogens and repetitive element DNA methylation changes in human placenta. Environ Int. 2014; 71: 81–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Doherty BT, Romano ME, Gui J, et al. Periconceptional and prenatal exposure to metal mixtures in relation to behavioral development at 3 years of age. Environ Epidemiol. 2020; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.