Abstract

The current study aims to examine (a) the mental well-being of university students, who were taking online classes, and (b) and test whether resilience would mediate the relationship between meaning in life and mental well-being. The sample of 302 university students (Mage = 20.25 years; 36.1% men, 63.9% women) was taken from the universities of Punjab, Pakistan. The participants were recruited online and they completed a cross-sectional survey comprising the scales of meaning in life, resilience, and mental well-being during COVID-19. Findings from the study indicated that participants had a normal to a satisfactory level of overall mental wellbeing during COVID-19. Resilience acted as a mediator for both the presence of meaning in life, the search for meaning in life, and mental well-being. Demographic variables including family size were significantly and positively related to resilience while the availability of personal room showed a significant positive relationship with mental well-being. These findings suggest that meaning in life and resilience supports mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic and that effective steps should be taken to make the lives of university students more meaningful and resilient.

Keywords: COVID-19, Meaning in life, Presence of meaning in life, Search for meaning in life, Resilience, Mental well-being, University students

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is a viral infection caused by Coronavirus that affects the respiratory system and this virus has influenced the lives of hundreds of millions of people around the globe (WHO, 2022). To control the spread of this disease, numerous changes were strictly incorporated at the government level in Pakistan. Similar to other countries, strict rules of lockdown and quarantine in Pakistan lead to the closure of educational institutions, offices, small and large businesses, and so forth. Moreover, due to this pandemic, the educational system shifted from direct classrooms to online classes which became a major stressor for students in Pakistan (Sahu, 2020). Students also reported issues with the online education system. A few examples of these issues faced by students included technological resources (e.g., unavailability of the laptop, unaffordability of internet services/smartphones, repeated disruption of internet services) or changes in student-teacher interaction (e.g. uncertain time response to student queries, and classroom discussion) (Adnan, 2020).

These rapid and unexpected changes during the first 2 years of COVID-19 were a stressor for individuals and influenced their psychological health (Fiorillo & Gorwood, 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Waris et al., 2020). Similarly, the negative events during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., uncertainty, isolation, fear, social distancing, etc.) enhanced the symptoms of anxiety and stress, consequently influencing mental health (Duan & Zhu, 2020; Satici et al., 2020). Some studies have also reported psychosocial reactions by university students such as anxiety, low mood (Aqeel et al., 2022), the feeling of uncertainty about the future, and fear of cleanliness (Mahmood et al., 2021).

Mental well-being is an important factor for the optimal functioning of society (Tennant et al., 2007). Individuals with well-being can deal with stressors of life, be creative, and work better for their society (Surya et al., 2017). In face of unanticipated situations, for example, epidemics or natural catastrophes, individuals experience substantial repercussions that reduce their mental well-being (Folkman & Greer, 2000; Maunder, 2003). Thus, the present study aims to investigate the mental well-being of university students in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic, its predictors, and the potential intervening mechanism in this association.

1.1. Meaning in life and mental well-being

During a difficult situation, meaning in life is considered one of the most vital elements to deal with stressors. It helps in finding a sense of purpose in this challenging process (Kim et al., 2005). Two components of meaning in life; the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life have been found to improve life satisfaction during COVID-19 (Karataş & Tagay, 2021; Karataş et al., 2021). The presence of meaning in life is related to a variety of positive psychological constructs like positive emotions (Zika & Chamberlain, 1992); feelings of happiness (Debats et al., 1995); life satisfaction (Kashdan & Steger, 2007); and individual development (Grouden & Jose, 2015). It can also stimulate a person's coping abilities by acting as a protective factor (Park & Ai, 2006; Taubman-Ben-Ari & Weintroub, 2008). Search for meaning in life is a reaction to stressful circumstances (Baumeister, 1991; Klinger, 1998) and is also reported to be adaptive (Davis et al., 1998; King et al., 2006; Mascaro & Rosen, 2005) except when accompanied by lower values of the presence of meaning in life. (Cohen & Cairns, 2012). However, more recently both the search for meaning in life and the presence of meaning in life have been observed to be protective factors in university students in China (Lew et al., 2020). In the same way, a study conducted during the beginning of the spread of COVID-19 in Poland reported that basic hope, high levels of meaning in life, and life satisfaction were related to lower levels of COVID-19 state anxiety and stress (Trzebiński et al., 2020). Nevertheless, as the COVID-19 pandemic is mentally challenging, whether both presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life are closely related to university students' mental health still requires more evidence.

1.2. Resilience and mental well-being

Another related factor that is protective of mental well-being in difficult life situations is resilience. The notion that a resilient person doesn't experience worry, emotional disturbance, and stress, is wrong. While some individuals associate resilience with psychological hardiness, it takes suffering and pain to demonstrate it. Resilience is an active process that is influenced by life circumstances and reactions to these circumstances (Shiner & Masten, 2012). The process of resilience includes three stages: 1) having a stable, immune, and healthy mental state during the continuous intervals of hardships; 2) Recovery or bouncing back from adversity, retrieval of the prior psychological strength after a stressful situation and 3) growth after recovery, with the individual retaining sound mental state and exhibiting improved functioning from even before the adversity (Amering & Schmolke, 2009; Ayed et al., 2019; Sood et al., 2014). In the university setting, resilience is seen to influence students, as university life can be tough, challenging and, involves the ability to deal with study/life balance, academic/coursework workload, and financial problems (Stallman, 2010). It also helps the students to adapt to their university setting (Wang, 2009). Studies demonstrate that resilience decreases the psychological distress in students, helps them in handling their studious tasks, and provides them advanced coping techniques when encountered with academic stresses (Abbott et al., 2009; Bovier et al., 2004). In general, resilience is needed for students, as it promotes their mental well-being, and helps them to settle and adapt to their life at a university (Chen, 2016; DeRosier et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2012; Wang, 2009). Especially during COVID-19 when university students are experiencing stress more than in usual circumstances it is expected that resilience would safeguard their well-being. Recent studies have recognized resilience as an approach to handling the mental well-being challenges due to COVID-19 (Prime et al., 2020). It has been reported to protect them from the perceived threat and future anxiety they feel due to COVID-19 (Paredes et al., 2021) Moreover, in regions like Palestine with ongoing stressors, people were able to retain high levels of resilience and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn protected them from mental distress (Veronese et al., 2021).

1.3. Resilience as a mediator between meaning in life and mental well-being

The role of meaning in life and resilience in well-being is evident from the above-mentioned studies. However, how resilience links meaningfulness with mental well-being is less explored. Studies have shown that meaningful living improves the level of resilience and also acts as a protective agent during adversity (Aliche et al., 2019; Du et al., 2017; Mohseni et al., 2019; Platsidou & Daniilidou, 2021). Similarly, meaning in life was found to be a positive predictor of resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic (Karataş & Tagay, 2021). Yıldırım et al. (2021) found that meaningful living protects from mental health issues through its positive impact on resilience. A similar conclusion was also drawn from a longitudinal study by Arslan and Yıldırım (2021) who observed the mediational role of resilience between meaning in life and mental well-being in university students.

A resilient individual can be considered skillful in using coping techniques to adjust to stressful circumstances, optimistic and socializing, maintaining an internal locus of control, and building a good self-image; all these things leads to a healthy mind and body (Burns et al., 2011). Considering this coping ability of resilience and its relationship with meaning in life and well-being, it may act as an essential mediator of the presence of meaning in life, search for meaning in life, and mental well-being in the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.4. The present study

The purpose of this study was to examine (a) the mental well-being level of university students, who were taking online classes, (b) the mediational role of resilience between the presence of meaning in life and mental well-being, and (c) between the search for meaning in life and mental well-being. It was hypothesized that the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life have an indirect influence on university students' mental well-being through resilience. Following are the hypotheses of the study: H1: the presence of meaning in life is positively associated with mental well-being. H2: search for meaning in life is positively associated with mental well-being. H3: the presence of meaning in life positively predicts mental well-being through resilience. H4: search for meaning in life positively predicts mental well-being through resilience.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

The present study was conducted through a cross-sectional research design.

2.2. Participants

Data were collected from February 2021 to July 2021 and a total of 302 students between the age ranges of 18 to 25 years from different public and private universities in Punjab, participated in the study. Since the option of “required” was selected for the online questionnaire i.e. participants have to answer each question of the survey to move to the next section, there were no missing values in the data. The sample size was calculated by g power based on five predictors, and linear multiple regression tests (effect size = 0.15, power of test = 0.95, and α = 0.05). It gave a sample size of 138, which meant that the current sample size was adequate to perform a mediation analysis in the present study. Overall, 302 students with an average age of 20.25 (SD = 1.45) completed the questionnaires. The participants included 109 men (36.1%), and 193 women (63.9%) with an average family size of 7 members (SD = 2.87). Among all the respondents 183 students (60.6%) had a personal room in their homes while 119 students (39.4%) didn't possess a separate room.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Meaning in life scale (MLS)

Meaning in life was evaluated using the meaning in life scale (Steger et al., 2006). Five items comprising the search for meaning in life subscale and five items comprising the presence of meaning in life subscale were rated from 1 to 7, where 1 = ‘Absolutely Untrue’, to 7 = ‘Absolutely True’. Greater scores on this scale indicate a high level of. Both subscales demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach's α = 0.82 and 0.85).

2.3.2. Survey for university students' mental well-being during COVID-19

Mental well-being was assessed by the survey developed by Martínez (Martínez et al., 2020). This survey included three sections: (i) measures for life satisfaction and wellbeing; (ii) distresses and direct effect of COVID-19; and (iii) relationships with family members, friends, and partners. For assessing life satisfaction, wellbeing, and the incidence of the most common negative emotions that affects the good MWB (worry and depression), the valid and standard central measures of wellbeing, were used (OECD: Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being, 2013). For concerns and perceptions of COVID-19, questions included COVID-19 infection concerns, government measures, pandemic's economic costs, updates and news, online learning, and work from home. For emotions and coping strategies, questions about happiness, optimism, stress, relationships, and gratitude were asked. To measure optimism and gratitude, a short form of the 10-item life orientation test (Scheier et al., 1994) and a short form of a gratitude self-reported questionnaire (McCullough et al., 2002) were used respectively. All questions were rated on a rating scale of 0–10, where 0 indicated the lowest score and 10 the highest score. This scale provided good reliability in the current study (Cronbach's α = 0.89).

2.3.3. Brief resilience scale (BRS)

Resilience was assessed using the BRS (e.g. “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”). It consisted of six items evaluating the capability to overcome stress (Smith et al., 2008). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’, and 5 = ‘strongly agree’. To calculate the total score, first, three items are reverse scored, then all 6 items are added. The obtained scores range from 6 to 30, where a high score represents more resilience. This instrument demonstrated strong internal reliability in previous research (Cronbach's α = 0.82; Arslan & Yıldırım, 2021).

In addition students were also asked about their sex (man or woman); age (years); if they have a personal room in their house (yes or no); Family size (number of family members living in their house including themselves); and if they were satisfied with their online classes (on a scale of 0 to 5 where 0 = ‘not at all satisfied’ and 5 = ‘completely satisfied).

2.4. Procedure

This research was permitted by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Applied Psychology, University of Punjab. In the current study, the inclusion criteria were (1) undergraduate university students and (2) experience in online classes for six or more months. So, only students who fulfilled this criterion participated in the study. The questionnaires were developed using google forms and distributed via a hyperlink, within the educational digital platform already adopted by each university including social media like WhatsApp, Facebook, and emails. With anonymous data collection, the confidentiality of the data was preferentially maintained.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

The descriptive information and correlation of study variables are given in Table 1 . Participants rated an average of 1.56 (SD = 1.34), indicating a lower satisfaction with their online classes. Specifically, both presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life were positively associated with each other, resilience, and mental well-being. Resilience also had a positive relationship with mental well-being. Among the other variables, only the availability of personal room and satisfaction with online classes were positively related to mental well-being. While the family size was positively associated with resilience.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexa | – | – | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 20.25 | 1.44 | −0.06 | |||||||

| 3. Family size | 7 | 2.87 | 0.04 | 0.11⁎ | ||||||

| 4. Personal roomb | – | – | −0.00 | −0.10 | −0.15⁎⁎ | |||||

| 5. Satisfaction with online classes | 1.56 | 1.34 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ||||

| 6. Presence of meaning in life | 4.66 | 1.26 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.12⁎ | 0.07 | |||

| 7. Search for meaning in life | 5.20 | 1.16 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.15⁎ | ||

| 8. Resilience | 3.41 | 0.49 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.22⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | |

| 9. Mental well-being | 6.40 | 1.01 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ |

0 = man and 1 = woman.

1 = yes and 0 = no.

p < .05.

p < .01.

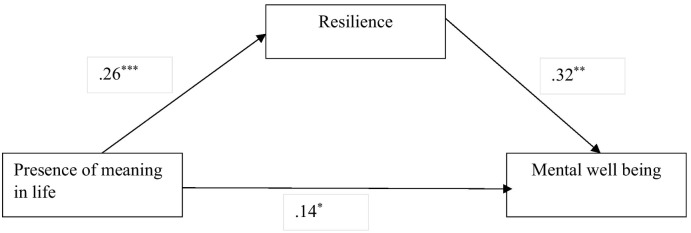

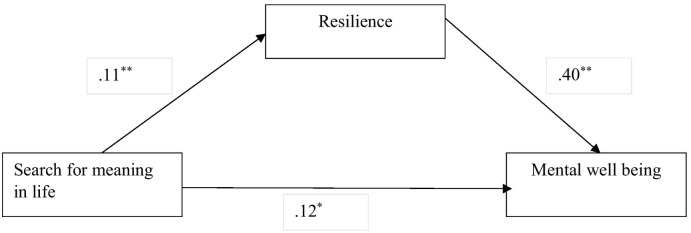

3.2. Testing the proposed model

To test the mediating role of resilience in meaning in life and mental well-being, two sets of analyses were run through Process by Hayes and Preacher (2014). Results in Table 2 demonstrate that both presence of meaning in life in Model 1 and the search for meaning in life in Model 2 positively predicted resilience and mental well-being. Further Resilience also positively predicted mental well-being. Indirect effects were also significant thus supporting the hypotheses that the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life predicted mental well-being through resilience. Both models were controlled for personal room and satisfaction with online classes as they were significantly correlated with mental well-being.

Table 2.

Results from process analyses for mediational models.

| Model | B | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: mental well-being | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Constant | 3.77 | 0.38 | 9.85 | <0.001 |

| Personal rooma | 0.24 | 0.24 | 2.29 | 0.020 |

| Satisfaction with online classes | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.78 | 0.005 |

| Presence of meaning in life | 0.26 | 0.04 | 6.24 | <0.001 |

| Resilience | 0.32 | 0.11 | 2.97 | 0.003 |

| Resilience as an outcome of the presence of meaning in life | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Constant | 4.04 | 0.42 | 9.62 | <0.001 |

| Personal rooma | 0.32 | 0.11 | 2.85 | 0.005 |

| Satisfaction with online classes | 0.13 | 0.04 | 3.11 | 0.002 |

| Search for meaning in life | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.44 | 0.020 |

| Resilience | 0.40 | 0.11 | 3.51 | <0.001 |

| Resilience as an outcome of the search for meaning in life | 0.10 | 0.02 | 4.15 | <0.001 |

| Indirect effects | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Presence of meaning in life->resilience->mental wellbeing | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.05 |

| search for meaning in life->resilience->mental wellbeing | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

Note. B = unstandardized coefficient, SE = standard error; Bootstrap sample size = 5000. LL = lower limit, CI = confidence interval, UL = upper limit.

1 = yes, and 0 = no.

Figural representations of emerged models are presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 showing the significant unstandardized regression weights for direct effects.

Fig. 1.

Mediating effect of resilience on the association between the presence of meaning in life and mental well-being.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Fig. 2.

Mediating effect of resilience on the association between the search for meaning in life and mental well-being.

Note. *p < .05, **p < 01.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the mental well-being levels of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of the study indicated that participants had an average score of 6.4 on a scale of 10 for overall mental well-being during COVID-19; which is similar to the findings of the research conducted on Italian university students; which showed that the students had a normal level of well-being and their stress levels were also not higher than the stress level of other students in prior studies (Capone et al., 2020). Additionally, the results of the current study showed a positive significant relationship for all variables, which is consistent with previous findings e.g. Karataş and Tagay (2021) found more meaning in life contributes to more resilience during COVID-19. Also, research conducted during COVID-19 revealed that resilience is a positive contributor to psychological health and subjective well-being in general (Di Monte et al., 2020; Paredes et al., 2021). Likewise, meaning in life has previously been linked with subjective well-being in other research (Doğan et al., 2012; Karaman et al., 2020; Karataş et al., 2021; Nowicki et al., 2020; Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, 2009).

The results of the mediation model revealed that resilience had a mediational role in the relationship between the presence of meaning in life and mental well-being and between the search for meaning in life and mental well-being. It seems as if resilience depends on both presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life to increase mental well-being. It can be expected that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students experienced a loss of meaning in life since they had to experience changes in their lifestyles, education, and even social relationships (de Jong et al., 2020). Similarly, during the lockdown, when every individual had to remain in their homes, the lack of activities, may result in a loss of meaning. So, in these circumstances, students needed more resources and beliefs to overcome adversity, find meaning in their dull lives, and keep their mental health in check. Thus, the findings of the current study provide support for the role of resilience in the relationship between the presence of meaning in life, search for meaning in life, and mental well-being, which is also evident from previous research conducted on different populations during the COVID-19 pandemic (Arslan & Yıldırım, 2021; Yıldırım et al., 2021).

The study also demonstrated some interesting findings. There was a positive relationship between family size and resilience. This finding is in line with the family resilience approach which involves the importance of family and familial relationships in dealing with adversity (Walsh, 2003). So, students may feel more at ease to overcome the tough circumstance by having more close individuals in their lives. Moreover, this study was conducted on university students in Pakistan, which is a collectivistic society where family ties are stronger than in other cultures. Future studies should explore this relationship in other cultures. Also, personal room and overall satisfaction with online classes were significantly positively correlated with mental well-being. Milmeister et al. (2021) also found that the learning satisfaction of students predicts students' mental well-being during the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, data were collected when institutes were closed due to COVID-19, so students had to remain at home and take online classes. In these circumstances, the availability of personal room for students may be beneficial for the mental well-being of students as evidenced by the finding of the current study.

4.1. Implication and limitations

Longitudinal methods should be used in upcoming research to understand variations in mental well-being as a result of the pandemic. Additional research may also implement observational and experimental techniques to evaluate real conduct in the pandemic (Bish & Michie, 2010). Moreover, the self-reported tools were used to collect data, which may have given biased data. Future studies should use diverse data collection methodologies (e.g., qualitative) to explore the study variables. Last, due to the pandemic, it was difficult to collect data face to face, so this study collected data online. Hence, only a limited number of students who had access to the internet were able to participate. Future research should implement other data collection methods.

Based on the outcomes of the present research, it was inferred that during challenging times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, discovering meaning in their lives, and possessing high levels of resilience positively affect the mental well-being of students. For this reason, educational settings should aim at improving the mental well-being of students by organizing training on resilience and meaning in life.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the outcomes of the current study expand our knowledge of the mental well-being of university students in the COVID-19 pandemic. These research findings suggest that the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life and resilience are positively associated with mental well-being. These results also present additional knowledge regarding the process underlying the association between both the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life, resilience, and mental well-being. It is indicated that high levels of presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life are related to more resilience, which in turn, results in better mental well-being in university students.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abbott J.-A., Klein B., Hamilton C., Rosenthal A.J. The impact of online resilience training for sales managers on wellbeing and performance. E-Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;5(1):89–95. doi: 10.7790/EJAP.V5I1.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M. Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students perspectives. Journal of Pedagogical Research. 2020;1(2):45–51. doi: 10.33902/jpsp.2020261309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aliche J.C., Ifeagwazi C.M., Onyishi I.E., Mefoh P.C. Presence of meaning in life mediates the relations between social support, posttraumatic growth, and resilience in young adult survivors of a terror attack. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2019;24(8):736–749. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2019.1624416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amering M., Schmolke M. In: Recovery in mental health: Reshaping scientific and clinical responsibilities. Stastny P., editor. Wiley Blackwell; 2009. Trans. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aqeel M., Abbas J., Shuja K.H., Rehna T., Ziapour A., Yousaf I., Karamat T. The influence of illness perception, anxiety and depression disorders on students mental health during COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan: A web-based cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare. 2022;15(1):17–30. doi: 10.1108/IJHRH-10-2020-0095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G., Yıldırım M. A longitudinal examination of the association between meaning in life, resilience, and mental well-being in times of coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayed N., Toner S., Priebe S. Conceptualizing resilience in adult mental health literature: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2019;92(3):299–341. doi: 10.1111/papt.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F. Guilford Press; 1991. Meanings of life. [Google Scholar]

- Bish A., Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(4):797–824. doi: 10.1348/135910710X485826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovier P.A., Chamot E., Perneger T.V. Perceived stress, internal resources, and social support as determinants of mental health among young adults. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(1):161–170. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015288.43768.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns R.A., Anstey K.J., Windsor T.D. Subjective well-being mediates the effects of resilience and mastery on depression and anxiety in a large community sample of young and middle-aged adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45(3):240–248. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.529604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone V., Caso D., Donizzetti A.R., Procentese F. University student mental well-being during COVID-19 outbreak: What are the relationships between information seeking, perceived risk, and personal resources related to the academic context? Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020;12(17) doi: 10.3390/su12177039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 2016;25(3):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen K., Cairns D. Is searching for meaning in life associated with reduced subjective well-being? Confirmation and possible moderators. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2012;13(2):313–331. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9265-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.G., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Larson J. Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(2):561–574. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong E.M., Ziegler N., Schippers M.C. From shattered goals to meaning in life: Life crafting in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debats D.L., Drost J., Hansen P. Experiences of meaning in life: A combined qualitative and quantitative approach. British Journal of Psychology. 1995;86(3):359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1995.tb02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier M.E., Frank E., Schwartz V., Leary K.A. The potential role of resilience education for preventing mental health problems for college students. Psychiatric Annals. 2013;43(12):538–544. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20131206-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte C., Monaco S., Mariani R., Di Trani M. From resilience to burnout: Psychological features of Italian general practitioners during COVID-19 emergency. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğan T., Sapmaz F., Tel F.D., Sapmaz S., Temizel S. Meaning in life and subjective well-being among Turkish university students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;55:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Li X., Chi P., Zhao J., Zhao G. Meaning in life, resilience, and psychological well-being among children affected by parental HIV. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2017;29(11):1410–1416. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1307923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L., Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo A., Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. European Psychiatry. 2020;63(1) doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Greer S. Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: When theory, research, and practice inform each other. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2000;9(1):11–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<11::AID-PON424>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouden M.E., Jose P.E. Do sources of meaning differentially predict search for meaning, presence of meaning, and wellbeing? International Journal of Wellbeing. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.5502/ijw.v5i1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F., Preacher K.J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2014;67(3):451–470. doi: 10.1111/BMSP.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O’Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A.K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Bullmore E.… Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman M.A., Vela J.C., Garcia C. Do hope and meaning of life mediate resilience and life satisfaction among Latinx students? British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2020;48(5):685–696. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2020.1760206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karataş Z., Tagay Ö. The relationships between the resilience of the adults affected by the COVID pandemic in Turkey and COVID-19 fear, meaning in life, life satisfaction, intolerance of uncertainty, and hope. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;172 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karataş Z., Uzun K., Tagay Ö. Relationships between the life satisfaction, meaning in life, Hope, and COVID-19 fear for Turkish adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:778. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2021.633384/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan T.B., Steger M.F. Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: Traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motivation and Emotion. 2007;31(3):159–173. doi: 10.1007/s11031-007-9068-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.H., Lee S.M., Yu K., Lee S., Puig A. Hope and the meaning of life as influences on Korean adolescent's resilience: Implications for counselors. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2005;6(2):143–152. doi: 10.1007/BF03026782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King L.A., Hicks J.A., Krull J.L., Del Gaiso A.K. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90(1):179. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger E. The search for meaning in evolutionary perspective and its clinical implications. 1998. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-06124-002

- Lew B., Chistopolskaya K., Osman A., Huen J.M.Y., Abu Talib M., Leung A.N.M. Meaning in life as a protective factor against suicidal tendencies in Chinese University students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood Z., Saleem S., Subhan S., Jabeen A. Psychosocial reactions of Pakistani students towards COVID-19: A prevalence study. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2021;37(2):456. doi: 10.12669/PJMS.37.2.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L., Valencia I., Trofimoff V. Subjective wellbeing and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Data from three population groups in Colombia. Data in Brief. 2020;32:106287. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro N., Rosen D.H. Existential meaning’s role in the enhancement of hope and prevention of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(4):985–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder R. Stress, coping and lessons learned from the SARS outbreak. Hospital Quarterly. 2003;6(4) doi: 10.12927/hcq.16480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough M.E., Emmons R.A., Tsang J.A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(1):112–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milmeister P., Rastoder M., Kirsch C., Houssemand C. Investigating the student's learning satisfaction, wellbeing, and mental health in the context of imposed remote teaching during the COVID-19 crisis. Self and Society in the CoronaCrisis. 2021;1(2) doi: 10.26298/x1z2-d065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni M., Iranpour A., Naghibzadeh-Tahami A., Kazazi L., Borhaninejad V. The relationship between meaning in life and resilience in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Health Psychology Report. 2019;7(2):133–138. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2019.85659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki G.J., Ślusarska B., Tucholska K., Naylor K., Chrzan-Rodak A., Niedorys B. The severity of traumatic stress associated with COVID-19 pandemic, perception of support, sense of security, and sense of meaning in life among nurses: Research protocol and preliminary results from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD Publishing; 2013. OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes M.R., Apaolaza V., Fernandez-Robin C., Hartmann P., Yañez-Martinez D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subjective mental well-being: The interplay of perceived threat, future anxiety, and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;170 doi: 10.1016/J.PAID.2020.110455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.L., Ai A.L. Meaning-making and growth: New directions for research on survivors of trauma. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2006;11(5):389–407. doi: 10.1080/15325020600685295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Zhang J., Li M., Li P., Zhang Y., Zuo X., Miao Y., Xu Y. Negative life events and mental health of Chinese medical students: The effect of resilience, personality, and social support. Psychiatry Research. 2012;196(1):138–141. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platsidou M., Daniilidou A. Meaning in life and resilience among teachers. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2021;5(2):97–109. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v5i2.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020;75(5):631–643. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Saricali M., Satici S.A., Griffiths M.D. Intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellbeing: Serial mediation by rumination and fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020;15:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M.F., Carver C.S., Bridges M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(6) doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R.L., Masten A.S. Childhood personality as a harbinger of competence and resilience in adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(2):507–528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood A., Sharma V., Schroeder D.R., Gorman B. Stress management and resiliency training (SMART) program among Department of Radiology Faculty: A pilot randomized clinical trial. EXPLORE. 2014;10(6):358–363. doi: 10.1016/J.EXPLORE.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallman H.M. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist. 2010;45(4):249–257. doi: 10.1080/00050067.2010.482109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger M.F., Frazier P., Kaler M., Oishi S. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Surya M., Jaff D., Stilwell B., Schubert J. The importance of mental well-being for health professionals during complex emergencies: It is time we take it seriously. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2017;5(2):188–196. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubman-Ben-Ari O., Weintroub A. Meaning in life and personal growth among pediatric physicians and nurses. Death Studies. 2008;32(7):621–645. doi: 10.1080/07481180802215627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant R., Hiller L., Fishwick R., Platt S., Joseph S., Weich S.…Stewart-Brown S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiliouine H., Belgoumidi A. An exploratory study of religiosity, meaning in life, and subjective wellbeing in Muslim students from Algeria. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2009;4(1):109–127. doi: 10.1007/s11482-009-9076-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trzebiński J., Cabański M., Czarnecka J.Z. Reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic: The influence of meaning in life, life satisfaction, and assumptions on world orderliness and positivity. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2020;25(6–7):544–557. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1765098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese G., Mahamid F., Bdier D., Pancake R. Stress of COVID-19 and mental health outcomes in Palestine: The mediating role of well-being and resilience. Health Psychology Report. 2021;9(4):398–410. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2021.104490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process. 2003;42(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/J.1545-5300.2003.00001.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. A study of resiliency characteristics in the adjustment of international graduate students at American universities. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2009;13(1):22–45. doi: 10.1177/1028315307308139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waris A., Atta U.K., Ali M., Asmat A., Baset A. COVID-19 outbreak: Current scenario of Pakistan. New Microbes and New Infections. 2020;35(20) doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update. Vol. 58. World Health Organization; 2022. pp. 1–23. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M., Arslan G., Wong P.T. Meaningful living, resilience, affective balance, and psychological health problems among Turkish young adults during coronavirus pandemic. Current Psychology. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zika S., Chamberlain K. On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology. 1992;83(1):133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]