Abstract

Objective:

In this study, we aimed to (1) assess the effectiveness of an intensive multimodal day treatment program in improving externalizing problems and function in elementary-age children and (2) examine 3 predictors of the treatment outcome (i.e., family functioning, baseline severity, and comorbid disorders).

Methods:

The sample included 261 children (80.9% boys) between ages of 5 and 12. A retrospective chart review, from 2013 to 2018, and a prospective chart review, from 2018 to 2019, were conducted to extract all relevant data for the present study. Parents and teachers provided reports on children’s externalizing problems (i.e., aggressive behavior, attention problems, and rule-breaking behavior) and their level of function across different domains. The level of family functioning was also reported by parents, while clinicians assessed children’s severity of disturbance and their diagnoses at intake.

Results:

Based on both parents’ and teachers’ reports, children showed significant improvement in their externalizing problems. Moreover, children showed functional improvement at home, at school, with peers, and in hobbies by the end of the program. Based on teacher’s reports, children with lower level of severity showed less improvement in their attention problems, and those with comorbid developmental problems showed less improvement in their aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors. Family functioning did not predict any treatment outcome.

Conclusion:

An intensive multimodal day treatment program was effective in reducing the symptoms of externalizing problems in elementary-age children. However, children with less severe difficulties and comorbid developmental problems showed less improvement in their externalizing problems.

Keywords: day treatment program, externalizing problems, family functioning, severity, comorbidity

Abstract

Objectif:

Nous visions par la présente étude à 1) évaluer l’efficacité d’un programme multimodal intensif de traitement de jour à améliorer les problèmes et la fonction d’externalisation chez les enfants d’âge primaire, et à 2) examiner trois prédicteurs du résultat du traitement (c.-à-d., le fonctionnement familial, la gravité au départ, et les troubles comorbides).

Méthode:

L’échantillon comprenait 261 enfants (80,9% des garçons) âgés entre 5 et 12 ans. Un examen rétrospectif des dossiers, de 2013 à 2018, et un autre examen prospectif des dossiers, de 2018 à 2019, ont été menés afin d’extraire toutes les données pertinentes pour la présente étude. Les parents et les enseignants ont fourni des rapports sur les problèmes d’externalisation des enfants (c.-à-d., le comportement agressif, les problèmes d’attention et le comportement de non-respect des règles) et sur leur niveau de fonctionnement dans différents domaines. Le niveau de fonctionnement familial était aussi rapporté par les parents, tandis que les cliniciens évaluaient la gravité de la perturbation chez les enfants et leur diagnostic à l’entrée dans le programme.

Résultats:

Selon les rapports tant des parents que des enseignants, les enfants manifestaient une amélioration significative de leurs problèmes d’externalisation. En outre, les enfants démontraient une amélioration fonctionnelle à la maison, à l’école, avec les camarades et dans les loisirs à la fin du programme. D’après les rapports des enseignants, les enfants dont le niveau de gravité était plus faible avaient moins d’amélioration de leurs problèmes d’attention, et ceux dont les problèmes développementaux étaient comorbides avaient moins d’amélioration de leurs comportements agressifs et de non-respect des règles. Le fonctionnement familial ne prédisait aucun résultat du traitement.

Conclusion:

Un programme multimodal intensif de traitement de jour a été efficace pour réduire les symptômes des problèmes d’externalisation chez des enfants d’âge primaire. Cependant, les enfants ayant des difficultés moins graves et des problèmes développementaux comorbides ont manifesté moins d’amélioration de leurs problèmes d’externalisation.

Introduction

Most psychiatric disorders emerge from childhood mental health problems. 1 –3 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and conduct disorder (CD) are the most frequently diagnosed childhood externalizing disorders leading to treatment referrals. 4 These disorders show moderate to high stability over time, 5,6 have a high degree of co-occurrence, 7 –9 and are associated with increased school expulsion, 10 academic underachievement, 11,12 substance abuse, 13 –15 and delinquency. 16,17 The detrimental progression of externalizing disorders has high social costs, 18 pointing to the necessity of providing early effective treatments.

Children with severe externalizing problems and global functioning difficulties in community schools require intensive treatment. Although day treatment programs have been the preferred treatment, 19,20 few studies have evaluated their effectiveness. In 1 Canadian study, Grizenko and colleagues found significant improvement in externalizing problems of children who attended their 4-month program. 21 Similar findings were found with elementary-age children, 19,22,23 preschoolers, 24,25 and adolescents. 26 –28 Some studies have found little to no effect though. 29,30 For instance, McCarthy and colleagues found no change in hyperactivity and conduct problem among children who attended a 10- to 13-week day program, possibly because of their small sample size and the limited direct therapy received by parents. 29

There is even less evidence about functional outcomes of children following day treatment programs. Although studies 21,31 report that most children returned to their community school following treatment, functional improvement levels in school and other settings remain unknown. Since mental health and well-being are measured by symptom severity and function, 32 measuring the impact of day treatment programs on function across multiple settings would highlight the additional benefits of resource-intensive treatment programs.

Little is also known about the predictors of outcome in day treatment programs, ie, baseline factors that directly impact treatment outcomes while remaining independent of specific treatment conditions. 33 Identifying these factors, especially in children with externalizing disorders who show small-to-medium treatment responses, 34,35 could inform treatment plans, programs, and outcomes. 36 Three predictors are pertinent: baseline severity, comorbidity, and family functioning. Disturbance severity is diverse in children referred to day treatment programs. Studies examining the effect of disturbance severity on treatment outcomes in children with externalizing problems are equivocal: Some found better outcomes in children with lower 27,37 or higher 38 levels of severity, while others found no effect. 39

The complexity theory postulates that more severely disturbed individuals may have decreased treatment responses. 40 For instance, disorder comorbidity, a critical and common characteristic of clinical populations, can both complicate a child’s presentation and influence treatment response. Few studies have assessed comorbidity as a predictor of day treatment outcome. One found greater behavioral improvement in children with externalizing disorders and comorbid depression, 31 while another found poorer treatment outcome in children with ADHD and comorbid oppositional defiance, 28 suggesting that comorbidity status (i.e., externalizing or internalizing) might differentially impact treatment outcomes.

Finally, family system theory suggests that behavior is best understood when studied within the family context. 41 Family dynamics are significant to children’s day-to-day functioning and fundamentally effect children’s psychological development. Although studies have shown strong associations between poor family functioning and externalizing problems, 42,43 only one has examined baseline family functioning as a predictor of day treatment outcomes: Poor family functioning was associated with greater behavioral change. 37

Given the negative and costly trajectories of untreated externalizing disorders in children, the financial cost of day treatment programs, and the limited literature on the effectiveness of and predictors of outcome for day treatment programs, the current study assessed the effectiveness of a systemic multimodal child psychiatric day treatment program by examining 3 questions: (1) Does the program reduce externalizing problems (ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms) in elementary-age children? (2) Do baseline severity, comorbid disorders, or family functioning predict changes in externalizing problems, while adjusting for age, gender, and household income? (3) Does child functioning improve at school and/or elsewhere postdischarge? We hypothesized that following treatment, children would have lower externalizing symptoms and improved functioning across several domains. Further, we hypothesized that poorer family functioning and greater baseline severity would predict greater change in externalizing symptoms, although there is limited literature on comorbidity and treatment outcomes.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Participants were 261 children (80.9% boys) aged 5 to 12 years (mean [M] = 8.15, standard deviation [SD] = 1.98) referred to a Child Psychiatry day treatment program in Montreal, Quebec, between 2013 and 2019. Children who were not responding to previous treatments and were unable to function in their community schools attended the program for 6 hrs/day, 3 to 4 days/week for approximately 9 months (M = 8.70, SD = 4.18 months, range: 2 to 23 months).

Upon referral to the program, elementary school-age children and their families are assessed by a psychiatrist to determine diagnoses and the following criteria for admission: severe externalizing and/or internalizing problems compromising global functioning; ability to participate in the language-based interventions; no active harm or compromise of child development; and motivation by the parents to participate in weekly sessions of family therapy throughout treatment. Fifty-six children are enrolled in the program at any given time, in a classroom-based milieu ranging from kindergarten to Grade 6, where they completed academic work in a classroom of 7 students, 1 teacher, and 1 childcare worker (CCW). Each child receives a combination of therapies including individual, group, occupational, speech, expressive, and/or cognitive behavioral therapies as needed. The program’s central approach is systemic and involves weekly individual or multiple family therapy sessions. Hospital staff remain in close contact with the community schools to strengthen communication and transfer knowledge, while community school staff visit the program to observe and discuss approaches used at the program. Each child returns to their community school once or twice a week with feedback on their effort to practice and generalize their therapeutic goals. Discharge, based on children’s readiness to return to their community school full time, is determined by clinical observation, functioning in the community school, and family factors.

Procedure

In this study, data collection was started in 2013, when multiple measures were introduced to formally assess treatment response. At intake, parents provided written informed consent for the clinical assessment and treatment of their children, sociodemographic information, and completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). 44,45 Community school teachers also completed the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF). 44,45 Two weeks into the program, parents completed the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD). 46 At discharge, parents completed the CBCL and the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I), 47 while the CCW and program teachers completed the CGI-I and TRF. Two weeks after the children returned to their community schools, teachers completed the CGI-I and TRF.

For the purpose of this study, ethics approval was obtained to perform a retrospective/prospective chart review. The chart review was conducted to extract data on children who attended the program between January 2013 and March 2019. All child and family data used in the present study were collected while the children were attending the program. Two research assistants entered the extracted data, and the third checked for accuracy (15% of the data) before analyses were conducted. Data reliability was approximately 99%. The participants in these analyses are those for which both pre- and post-treatment measures are available. Parent(s) will be used throughout the manuscript to represent the children’s biological parent(s) or primary caregiver(s).

Measures

Predictors

At intake, program psychiatrists assessed the children’s disturbance severity with the Child Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), 48 using a scale of 1 (least severe) to 100 (most severe). In previous studies, CGAS has shown high interrater reliability (r = 0.83). 49

At intake, the child and their family participated in the clinical psychiatric assessment which provided Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition/DSM-V diagnoses. Axis I diagnoses were used to classify children into 3 comorbidity groups: no comorbidity (1 externalizing or internalizing disorder), same-domain comorbidity (2 or more externalizing or internalizing disorders), and cross-domain comorbidity (externalizing and internalizing disorders). Developmental comorbidity included diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder, language problems, learning difficulties, and motor/sensory problems. Discharge diagnoses were extracted from the Psychiatric discharge summaries when available (149 of 261 children).

Family functioning was assessed using the general functioning subscale of the 60-item McMaster FAD. 46 Parents rated each item on a scale ranging from “1 = Strongly agree” to “4 = Strongly disagree.” Consistent with previous studies, 50 high internal consistency (α = 0.88) was observed.

Outcomes

Parents completed CBCL 6-18 attention problems, 44 aggressive behavior, and rule-breaking behavior scales which were used to assess the children’s ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms, respectively. Teachers completed the same scales on the TRF 6 to 18. 44 For younger children (n = 10), parents (n = 10) and teachers (n = 3) completed the CBCL 1.5-5 45 and Caregiver-TRF 1.5-5, 45 respectively. Conduct disorder symptoms could not be determined using the latter questionnaires resulting in a slightly smaller sample size.

An adapted 5-item version of the CGI-I 47 was first introduced in 2017 to assess the children’s functional improvement at school, at home, with peers, in hobbies, and globally. In previous studies, the original 1-item CGI-I has been shown to be a valid measure to assess functional outcome. 51 Informants were asked to rate improvement in each setting on a scale ranging from “1 = Very much improved” to “7 = Very much worse” compared to child’s function before entering the program. Ratings of “1 = Very much improved” and “2 = Much improved” indicate improvement. 52 Good internal consistency (α = 0.73 for parents and CCWs; α = 0.61 for community teachers) was observed.

Demographics

The Pre-Interview Questionnaire developed by the program was completed by parents at intake to provide information on the children’s place of birth, age, gender, history of school suspensions/expulsions, referral source, parental education, and household income.

Statistical Analyses

Participants included in the analyses had both pre- and post-treatment CBCL and/or TRF. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to measure changes in aggressive behavior, attention problems, and rule-breaking behavior T-scores over time, where effect sizes were interpreted based on Cohen 53 small (d = 0.2 to 0.5), medium (d = 0.5 to 0.8), and large (d > 0.8) categories. Frequency analyses were conducted to examine the children’s functional improvement across 5 different settings.

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted on children’s CBCL and TRF change scores (i.e., intake subtracted by discharge scores) to examine the predictiveness of family functioning, baseline severity, and comorbid disorders. In these analyses, family functioning, baseline severity, comorbidity (dummy variables: no comorbidity [reference group], same domain, cross-domain), and developmental comorbidity were entered in Step 1. Covariates (age, gender, household income) were entered in Step 2.

Although treatment duration and wait time to enter the program varied, they were not adjusted for in the analyses as no significant associations with the outcomes were observed. Furthermore, since data were unavailable for some children, analyses differed in sample sizes. Table 1 includes descriptive and predictor variables sample sizes. Table 2 includes intake and discharge CBCL and TRF scale and sample sizes. Analyses were conducted using SPSS-23.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Children Admitted at the Day Treatment Program.

| Variables | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||||

| Age | 261 | 8.15 | 1.98 | |

| Gender | 261 | |||

| Boy | 80.9 | |||

| Girl | 19.1 | |||

| Born in Canada | 250 | 96.4 | ||

| Primary care taker | 248 | |||

| Biological parent | 94.0 | |||

| Adapted/fostered | 3.2 | |||

| Other | 2.8 | |||

| Mother’s employment | 234 | |||

| Full-time job | 53.0 | |||

| Part-time job | 17.5 | |||

| Full-time student | 3.0 | |||

| Part-time student | 2.1 | |||

| Homemaker | 20.1 | |||

| Unemployed | 3.8 | |||

| Other | 5.1 | |||

| Mother’s education | 242 | |||

| Partial or completed high school | 26.4 | |||

| Commercial or trade school | 15.3 | |||

| CEGEP or partial university | 26.8 | |||

| Graduate or postgraduate university | 30.6 | |||

| Other | 0.8 | |||

| Mother reported household income | 227 | |||

| Less than $40,000 (CAD) | 38.3 | |||

| $40,000 to $80,000 (CAD) | 29.5 | |||

| $80,000 and over (CAD) | 32.2 | |||

| Separated/divorced parents | 235 | |||

| Yes | 37.0 | |||

| No | 63.0 | |||

| Source of referral | 251 | |||

| Teacher | 41.8 | |||

| Social work | 31.1 | |||

| Parent | 26.3 | |||

| Pediatrician | 21.5 | |||

| Department of youth protection | 3.2 | |||

| Court order and Law Enforcement Agency | 0.8 | |||

| Expelled/suspended from school | 251 | |||

| Yes | 18.3 | |||

| No | 75.7 | |||

| Predictors of outcome | ||||

| Family functioning (FAD) | 162 | 1.80 | .460 | |

| Baseline severity (CGAS) | 182 | 36.3 | 8.69 | |

| Comorbidity (intake psychiatric assessment) | 232 | |||

| One externalizing or one internalizing | 35.8 | |||

| Same-domain comorbidity | 50.4 | |||

| Cross-domain comorbidity | 13.8 | |||

Note. N = 261. CGAS = Child Global Assessment Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Percentage of Disorders Established by Psychiatrists at Intake and Discharge.

| Disorders | Intake (%) | Discharge (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing | |||

| ODD | 69.8 | 67.1 | <0.001 |

| ADHD | 50.3 | 67.1 | <0.001 |

| CD | 18.1 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder | 4.0 | 5.4 | =0.002 |

| Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct | 0.7 | 0.7 | =0.934 |

| Internalizing | |||

| Anxiety problems | 14.8 | 19.5 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 4.7 | 4.0 | =0.579 |

| Adjustment disorder with anxiety, depressed mood, or both | 1.3 | 4.0 | =0.771 |

| Developmental problems | |||

| Autism spectrum disorder | 4.7 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Language problems | 10.7 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Learning difficulties | 18.8 | 42.3 | <0.001 |

| Motor/sensory problem | 4.0 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Parent–child relationship difficulties | 32.9 | 34.9 | <0.001 |

| Attachment problem | 8.7 | 11.4 | <0.001 |

| Adjustment disorder—unspecified type | 0.0 | 1.3 | Not testable |

Note. N = 149. Anxiety problems include different forms of anxiety such as general anxiety, separation anxiety, specific phobia, and so on. ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder.

Data imputation

Missing data ranged between 4.4% and 11.7% for pretreatment CBCL and TRF and between 5.6% and 37.6% for predictors and covariates. For CBCL and TRF, missing items were imputed in each domain with the average score on that domain (i.e., mean imputation). Multivariate imputation 54 by chained equations algorithm 55 in R 56 was used to replace the missing values in predictors and covariates, since not all of these variables had items to be used for mean imputation.

Comparison between included and excluded participants

Independent sample t-tests, for continuous variables, and chi-square tests, for categorical variables, revealed that included and excluded children were similar in age, gender, household income, comorbidity, developmental comorbidity, baseline severity, family functioning, and CBCL and TRF T-scores at intake.

Results

Descriptive of Sample

Ninety-six percent of children were born in Canada and lived with their biological parent(s). Approximately 57% of mothers had a college or higher education, and 61.7% had a household income of $40,000 or higher (Table 1). The prevalence of primary disorders at intake was ODD (63.2%), ADHD (49.8%), parent and child relational difficulties (27.2%), anxiety (16.1%), and CD (11.9%). i Most children (79.2%) had 2 or more diagnoses. Among children in the no comorbidity category, 89.1% had externalizing disorders. In the same-domain comorbidity category, 91.5% of children had comorbid externalizing disorders. In the cross-domain category, 71.9% of children had externalizing and anxiety disorders.

Diagnosis Changes

Table 2 shows the frequency of psychiatrist-defined diagnoses at intake and discharge for 149 of the 261 children, who had both pre- and post-treatment psychiatric reports. At discharge, ADHD diagnoses significantly increased by 16.8%, while ODD and CD diagnoses decreased by 2.7% and 15.4%, respectively (Ps < 0.001).

Change in Symptoms

Table 3 presents means, SDs, and percentages for the CBCL and TRF domains. Parent-rated aggressive behavior (Z = −8.01, P < 0.001; d = 0.75, N = 115), attention problems (Z = −4.72, P < 0.001; d = 0.44, N = 117), and rule-breaking behavior (Z = −7.03, P < 0.001; d = 0.68, N = 107) discharge scores are significantly lower compared to intake. Teacher-rated aggressive behavior, attention problems, and rule-breaking behavior symptoms (Z = −11.70, −11.14, and −11.63; d = 0.80, 0.78, and 0.80; N = 209, 202, and 211; Ps < 0.001) exhibit similar decreases but with larger effect sizes.

Table 3.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Frequencies of Children’s T-scores on Aggressive Behavior, Attention Problems, and Rule-Breaking Behavior Domains of CBCL and TRF.

| Variables | CBCL | TRF | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Normal symptoms (%) | Borderline/clinical symptoms (%) | N | Mean | SD | Normal symptoms (%) | Borderline/clinical symptoms (%) | ||

| Aggressive behavior | |||||||||||

| At intake | 123 | 69.7 | 11.90 | 36.6 | 63.4 | 241 | 75.9 | 13.1 | 20.3 | 79.7 | |

| At discharge | 115 | 60.3 | 8.33 | 69.6 | 30.4 | 218 | 57.9 | 8.26 | 83 | 17 | |

| χ 2(1) = 23.6, P < 0.001 | χ 2(1) = 8.57, P = 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Attention problems | |||||||||||

| At intake | 123 | 65.1 | 10.2 | 48 | 52 | 242 | 68.1 | 10.9 | 45 | 55 | |

| At discharge | 117 | 60.9 | 7.97 | 71.8 | 28.2 | 210 | 55.2 | 6.18 | 93.8 | 6.2 | |

| χ 2(1) = 19.7, P < 0.001 | χ 2(1) = 3.27, P = 0.062 | ||||||||||

| Rule-breaking behavior | |||||||||||

| At intake | 113 | 63.6 | 7.48 | 55.8 | 44.2 | 234 | 66.4 | 7.48 | 35.5 | 64.5 | |

| At discharge | 114 | 57.7 | 6.64 | 85.1 | 14.9 | 223 | 55.2 | 6.17 | 90.6 | 9.4 | |

| χ 2(1) = 15.2, P < 0.001 | χ 2(1) = 6.48, P = 0.007 | ||||||||||

Note. Normal range: T-score 50 to 64; borderline range: T-score 65 to 69; clinical range: T-score 70 to 100. The sample size varies for each variable and from intake to discharge. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; TRF = Teacher’s Report Form; SD = standard deviation.

Predictors of Outcome

Pooled coefficients (Table 4) revealed that baseline severity significantly predicts changes in teacher-reported aggressive behavior (b = −.252, standard error [SE] = .105, P = 0.017, N = 261), attention problems (b = −.256, SE = .117, P = 0.031, N = 261), and rule-breaking behavior (b = −.117, SE = .034, P = 0.001, N = 261) scores. Moreover, after controlling for the covariates, baseline severity remains a significant predictor for changes in aggressive (b = −.357, SE = .119, P = 0.003, N = 261) and rule-breaking (b = −.131, SE = .042, P = .003, N = 261) behavior scores: children with higher intake severity levels show greater behavioral changes.

Table 4.

Pooled Unstandardized Coefficients for Change Scores in Aggressive Behavior, Attention Problems, and Rule-Breaking Behavior Reported on CBCL and TRF.

| Variables | CBCL | TRF | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive behavior | P | Attention problems | P | Rule-breaking behavior | P | Aggressive behavior | P | Attention problems | P | Rule-breaking behavior | P | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||

| Severity | .081 | 0.305 | −.054 | 0.212 | −.009 | 0.798 | −.252 | 0.017 | −.256 | 0.031 | −.117 | 0.001 |

| Family function | .860 | 0.579 | 1.43 | 0.114 | −.008 | 0.990 | −1.24 | 0.639 | −.184 | 0.936 | −.686 | 0.344 |

| Developmental comorbidity | −2.51 | 0.077 | −.370 | 0.635 | −1.03 | 0.091 | −2.43 | 0.189 | −5.39 | 0.009 | −.769 | 0.164 |

| Same-domain comorbidity | 1.07 | 0.463 | 1.01 | 0.275 | .711 | 0.295 | −2.48 | 0.209 | −1.37 | 0.504 | −.307 | 0.611 |

| Cross-domain comorbidity | 2.19 | 0.280 | 1.41 | 0.300 | 1.36 | 0.149 | −1.96 | 0.530 | .048 | 0.987 | .172 | 0.843 |

| R 2 | .079 | .081 | .053 | .055 | .058 | .086 | ||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||

| Severity | .074 | 0.454 | −.002 | 0.973 | .001 | 0.976 | −.357 | 0.003 | −.221 | 0.112 | −.131 | 0.003 |

| Family function | .843 | 0.594 | 1.31 | 0.156 | −.005 | 0.994 | −.795 | 0.748 | −.277 | 0.905 | −.578 | 0.443 |

| Developmental comorbidity | −2.47 | 0.097 | −.436 | 0.570 | −1.10 | 0.085 | −2.34 | 0.199 | −5.51 | 0.008 | −.853 | 0.129 |

| Same-domain comorbidity | 1.10 | 0.449 | .957 | 0.247 | .712 | 0.295 | −2.68 | 0.177 | −1.30 | 0.537 | −.325 | 0.596 |

| Cross-domain comorbidity | 2.58 | 0.221 | 1.49 | 0.273 | 1.47 | 0.141 | −1.03 | 0.753 | .059 | 0.985 | .473 | 0.597 |

| Gender | −.194 | 0.904 | −1.37 | 0.130 | −.359 | 0.617 | 3.33 | 0.114 | .289 | 0.902 | 1.25 | 0.064 |

| Age | −.156 | 0.705 | .238 | 0.284 | .025 | 0.896 | −.783 | 0.165 | .298 | 0.626 | −.113 | 0.541 |

| Middle income | −.288 | 0.853 | −1.71 | 0.069 | −.675 | 0.390 | 3.67 | 0.075 | −1.06 | 0.665 | −.036 | 0.962 |

| High income | −2.50 | 0.119 | −3.28 | 0.000 | −.743 | 0.352 | −1.15 | 0.563 | −.537 | 0.818 | −.678 | 0.288 |

| .031 | .137 | .025 | .062 | .005 | .040 | |||||||

Note. N = 261. Gender: girls = 1, boys = 2; middle income, high income, developmental, same-domain, and cross-domain comorbidities: yes = 1, no = 0. Family function was measured using FAD, where higher score indicates less functioning families. Severity was measured using CGAS, where higher score indicates lower level of severity. CGAS = Child Global Assessment Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device.

Developmental comorbidity (b = −5.39, SE = 2.05, P = 0.009, N = 261) predicts less change in teacher-reported attention problems and remains significant (b = −5.51, SE = 2.08, P = 0.008, N = 261) after controlling for the covariates.

High household income is associated with less change in parent-reported attention problems.

Family functioning, same-, and cross-domain comorbidities do not significantly predict behavioral changes (Table 4).

Functional Improvement: CGI-I Reported by Parents, CCW, and Community Teachers

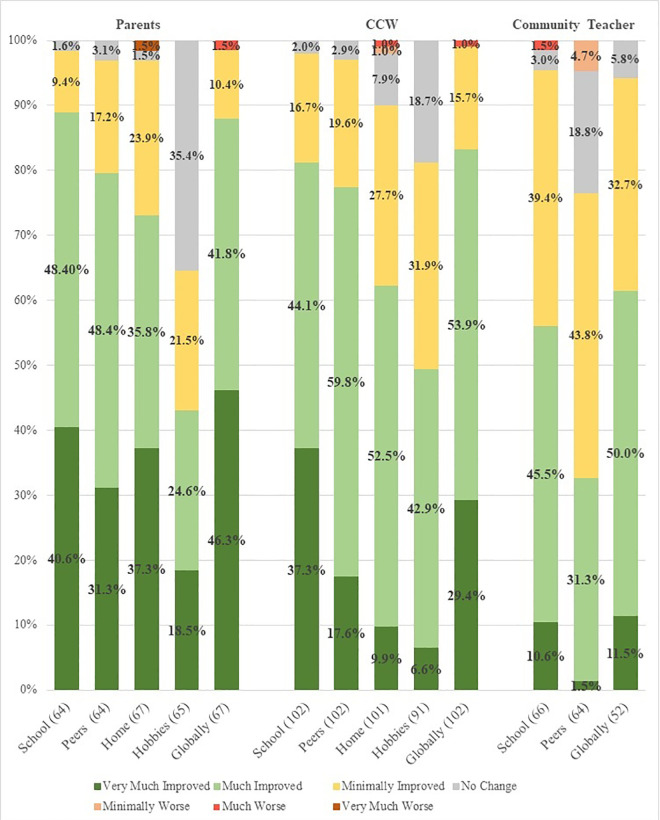

Both parents (N = 67) and CCWs (N = 102) report that over 80% of children demonstrate improvement at school and globally, and that over 70% show improvement in peer interactions (Figure 1). Community teachers (N = 73) report that 56.1% and 61.5% of children show improvement at school and globally, respectively.

Figure 1.

CGI-I reported by parents, CCW, and community school teacher. Note. The results regarding community teacher’s report of children’s improvement at home (N = 3) and in hobbies (N = 14) were not included in this study given the small sample size for these 2 domains. CCW = childcare worker; CGI-I = Clinical Global Impression of Improvement.

Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of a psychiatric day treatment program in reducing externalizing problems in elementary-age children. This study is strengthened by the use of standardized questionnaires from multiple informants, the identification of predictors of treatment outcome, and measures of improvement in the children’s functioning across different settings.

Consistent with previous studies, 19,21,22 our findings indicate that all informants reported significant reductions in the children’s externalizing symptomatology following treatment: Reductions were greatest in aggressive behavior, followed by rule-breaking behavior, and attention problems. These gains may reflect the program’s emphasis on reintegration of children into their community school by utilizing consistent communication between the program and community schools, individual care, special education, class-based behavioral plans, family and group therapies focusing on social skills, emotional regulation, and creative expression. These program components, including a focus on family therapy and inclusion of multiple informants’ ratings of children’s behavior, could account for the difference between our study and those 29,30 reporting no improvement in children’s behavior following treatment within other programs.

Significantly, children showed improvement in their functioning across different domains, with parents and CCWs reporting greater improvements relative to community teachers. Of note, this functional improvement cannot be directly explained by changes in diagnoses from intake to discharge, since while CD decreased, ADHD increased. The change in the frequency of diagnoses reflects findings from comprehensive assessments of the children and refined diagnoses and treatment, suggesting that the program’s treatment approach with symptom reduction and functional improvement led to a successful return to community school rather than disorder remission. 57

Among the outcome predictors, baseline severity and developmental comorbidity were associated with changes in externalizing symptoms, but only for teacher-reported behaviors. Contrary to most, 27,37 but not all 38 previous findings, after controlling for covariates, higher baseline severity predicted greater change in aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors. However, without information on trauma, social, and adversity variables, it is difficult to discern compounding factors for improvement. One explanation might be that this day treatment program offers an intensive multimodal intervention in a highly structured environment with a high staff-to-child ratio, providing an optimal environment in which severely disturbed children experience therapeutic gains. 38 Furthermore, our finding is consistent with the hospital triage process which prioritizes least disruptive treatment approaches: Children required severe enough problems and functional impairments to warrant referral into a day hospital setting.

While comorbid developmental problems were associated with less improvement in children’s attention problems, same- and cross-domain comorbidities were not associated with treatment outcomes. This finding could be explained by the program’s lack of focus on developmental problems as it is the internalizing and externalizing problems that keep children out of community schools. Supported by the complexity hypothesis, 40 developmental problems need to be addressed separately in day treatment programs as they can add to the therapeutic challenge and hinder the effectiveness of the program. That internalizing and externalizing comorbidities did not dampen treatment response for externalizing symptoms reflects the enmeshment of symptom profiles across disorders and the targeting of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the day hospitalization treatment.

Unlike previous studies, 37,58 –60 family functioning did not predict changes in externalizing problems, possibly because of the low number of poorly functioning families (25%) in our sample. Additionally, given that family involvement in the treatment process predicts outcomes in day treatment programs, 30,61 it is possible that the program’s unique focus on weekly family therapy sessions also explains current findings: Family interventions would support positive outcomes in children independent of baseline family function by addressing exactly such needs. This hypothesis will be examined in future studies, where changes in family functioning between intake and discharge will be used to predict treatment outcomes.

In this study, that teacher reports yielded stronger results compared to parent reports reflects the program’s primary goal of targeting children’s dysfunctional school behaviors to help them return to their community school. Program discharge was based on readiness to return to the community school, and when important family challenges remained, families were transferred to outpatient services. Accordingly, changes in children’s behavior could have been more evident in school compared to home. Likewise, the attributional bias context model, a theoretical framework explaining the observed informant discrepancies in children’s assessment, suggests that differences between informants’ reports reflect children’s distinct behavioral expressions across different settings 62 and informants. 63 Irrespective of the reason, our findings point to the importance of a multiple-informant approach in gaining a broader and deeper understanding of the conditions under which children show problematic behaviors, as well as their improvement in such behaviors.

Limitations

While wait time for admission did not predict improvement, the absence of wait-list controls precluded us from excluding that the observed improvements in the program were due to other factors, including maturation and expectation of receiving treatment. The intake and discharge TRFs were completed by different teachers, reflecting treatment duration which spanned more than 1 school year. This may have reduced their comparability. Furthermore, family functioning levels in multicultural and varied family systems may not be accurately captured in the measures used. How parenting capacity, adverse events, and intergenerational trauma may influence outcomes remain unknown. Lastly, treatment status was known by all informants.

Future Directions and Implications

The findings reported here regarding children’s functional improvement warrant replication in studies examining pre- and post-treatment function using a variety of validated standardized scales. For a more comprehensive evaluation of day treatment programs, subsequent studies should include (1) waitlist controls, (2) parental adversity or trauma measures, (3) cost-effective analyses, and (4) long-term follow-up assessments to strengthen the evidence regarding the effectiveness of day treatment programs along with informing clinical and policy decisions.

Findings of this study provide evidence that an intensive systemic multimodal-based day treatment program effectively improves children’s externalizing problems and function in multiple domains. Our findings highlight the usefulness of day treatment programs for high-risk elementary-aged children within the mental health network, with evidence that this service works on disorders with costly and lasting consequences. Furthering our understanding of predictors of outcomes allows clinicians and policy-makers to gain better insight into which children benefit more from day treatment programs.

Conclusion

An intensive multimodal day treatment program is effective in improving the symptoms and function of elementary-age children with externalizing problems. Lower baseline severity levels predict less change in attention problems, and comorbid developmental problems predict less change in aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible with the support of Drs Brendan Andrade, Lily Hechtman, Norbert Schmitz, and program staff.

Note

The percentages of disorders do not add up to 100% because of comorbidity.

Authors’ Note: Anonymized data will be made available to qualified researchers upon request and REB approval.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by the Department of Psychiatry, Jewish General Hospital, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and a Graduate Excellence Fellowship in Mental Health Research Award by the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University.

ORCID iD: Ashley D. Wazana, MD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4964-5163

References

- 1. Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):764–772. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):709–717. doi:10.1001/archpsyc. 60.7.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):56–63. doi:10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(12):1468–1484. doi:10.1097/00004583-200012000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ebejer JL, Medland SE, Werf J, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Australian adults: Prevalence, persistence, conduct problems and disadvantage. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47404. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, et al. Research review: DSM-V conduct disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):3–33. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad of Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(10):1203–1211. doi:10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loeber R, Green SM, Keenan K, Lahey BB. Which boys will fare worse? Early predictors of the onset of conduct disorder in a six-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):499–509. doi:10.1097/00004583-199504000-00017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Souza I, Pinheiro MA, Denardin D, Mattos P, Rohde LA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity in Brazil: comparisons between two referred samples. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13(4):243–248. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0402-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parker C, Tejerina-Arreal M, Henley W, Goodman R, Logan S, Ford T. Are children with unrecognised psychiatric disorders being excluded from school? A secondary analysis of the British child and adolescent mental health surveys 2004 and 2007. Psychol Med. 2019;49(15):2561–2572. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galéra C, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Bouvard MP, Fombonne EI. Childhood and adolescent hyperactivity-inattention symptoms and academic achievement 8 years later: the Gazel youth study. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1895–1906. doi:10.1017/S0033291709005510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. López-Villalobos JA, Andrés-De Llano JM, López-Sánchez V, et al. Prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder in a sample of Spanish children between six and sixteen years: teacher’s report. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2015;43(4):213–220. doi:10.1017/sjp.2013.69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghosh A, Malhotra S, Basu D. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), the forerunner of alcohol dependence: a controlled study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;11:8–12. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. The role of early childhood ADHD and subsequent CD in the initiation and escalation of adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(2):362–374. doi:10.1037/a0036585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wojciechowski TW. ADHD presentation and alcohol use among juvenile offenders: a group-based trajectory modeling approach. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2018;27(2):86–96. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2017.1411304 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Underwood LA, Washington A. Mental illness and juvenile offenders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(2):228. doi:10.3390/ijerph13020228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BS, et al. The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39(1):21–32. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9443-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen MA, Piquero AR. New evidence on the monetary value of saving high risk youth. J Quant Criminol. 2009;25(1):25–49. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1077214 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jerrott S, Clark SE, Fearon I. Day treatment for disruptive behaviour disorders: can a short-term program be effective? J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):88–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zimet SG, Farley GK. Day treatment for children in the United States. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(6):732–738. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(10)60116 -1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grizenko N, Papineau D, Sayegh L. Effectiveness of a multimodal day treatment program for children with disruptive behavior problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):127–134. doi:10.1097/00004583-199301000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hussey DL, Guo S. Behavioral change trajectories of partial hospitalization children. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(4):539–547. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.72.4.539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kotsopoulos S, Walker S, Beggs K, Jones B. A clinical and academic outcome study of children attending a day treatment program. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(6):371–378. doi:10.1177/070674379604100608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin SE, McConville DW, Williamson LR, Feldman G, Boekamp JR. Partial hospitalization treatment for preschoolers with severe behavior problems: child age and maternal functioning as predictors of outcome. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2013;18(1):24–32. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ware LM, Novotny ES, Coyne L. A therapeutic nursery evaluation study. Bull Menninger Clin. 2001;65(4):522–548. doi:10.1521/bumc.65.4.522.19841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kennair N, Mellor D, Brann P. Evaluating the outcomes of adolescent day programs in an Australian child and adolescent mental health service. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16(1):21–31. doi:10.1177/1359104509340951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Milin R, Coupland K, Walker S, Fisher-Bloom E. Outcome and follow-up study of an adolescent psychiatric day treatment school program. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(3):320–328. doi:10.1097/00004583-200003000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sibley MH, Smith BH, Evans SW, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM. Treatment response to an intensive summer treatment program for adolescents with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(6):443–448. doi:10.1177/1087054711433424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCarthy G, Baker S, Betts K, et al. The development of a new day treatment program for older children (8–11 years) with behavioural problems: the go zone. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;11(1):156–166. doi:10.1177/1359104506059134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bennett DS, Macri MT, Creed TA, et al. Predictors of treatment response in a child day treatment program. Resid Treat Child Youth. 2001;19(2):59–72. doi:10.1300/J007v19n02_05 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grizenko N, Sayegh L. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a psychodynamically oriented day treatment program for children with behaviour problems: a pilot study. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35(6):519–525. doi:10.1177/070674379003500609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dang H-M, Weiss B, Trung LT. Functional impairment and mental health functioning among Vietnamese children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemio. 2016;51(1):39–47. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Garcia AM, Sapyta JJ, Moore PS, et al. Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome in the Pediatric Obsessive Compulsive Treatment Study (POTS I). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1024–1033. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Masi G, Pietro M, Manfredi A, et al. Response to treatments in youth with disruptive behavior disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):1009–1015. doi:10.1089/cap.2010.0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bakker MJ, Greven CU, Buitelaar JK, et al. Practitioner review: Psychological treatments for children and adolescents with conduct disorder problems - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(1):4–18. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychol Bull. 1992;111(1):127–155. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grizenko N, Sayegh L, Papineau D. Predicting outcome in a multimodal day treatment program for children with severe behaviour problems. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39(9):557–562. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pearlstein SS. The effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ unpublished thesis]. 2003.

- 39. Kiser LJ, Millsap PA, Hickerson S, et al. Results of treatment one year later: Child and adolescent partial hospitalization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(1):81–90. doi:10.1097/00004583-199601000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Comorbidity, case complexity, and effects of evidence-based treatment for children referred for disruptive behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(3):455–467. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bowen M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. New York (NY): Aronson; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abu-Rayya H, Yang B. Unhealthy family functioning as a psychological context underlying Australian children’s emotional and behavioural problems. Internet J Ment Health. 2012;8(1):1–8. doi:10.5580/2c24 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roberts R, McCrory E, Joffe H, De Lima N, Viding E. Living with conduct problem youth: family functioning and parental perceptions of their child. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(5):595–604. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-1088-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms & Profiles. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop D. The McMaster family assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9(2):171–180. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976;1076:534–537. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shaffer D, Gould M, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;4(11):1228–1231. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC. Further measures of the psychometric properties of the children’s global assessment scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(9):821–824. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Byles J, Byrne C, Boyle MH, Offord DR. Ontario child health study: reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster family assessment device. Fam Process. 1988;27(1):97–104. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1988.00097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lam RW, Endicott J, Hsu MA, Fayyad R, Guico-Pabia C, Boucher M. Predictors of functional improvement in employed adults with major depressive disorder treated with desvenlafaxine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(5):239–251. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martin A, Scahill L, Charney DS. Clinical instruments and scales in pediatric psychopharmacology. Pediatric psychopharmacology: Principles and practice. 1st ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the social sciences. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 54. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi.org/10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3): 1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [Google Scholar]

- 56. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851–855. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sunseri PA. Family functioning and residential treatment outcomes. Resid Treat Child Youth. 2004;22(1):33–53. doi:10.1300/J007v22n01_03 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sunseri PA. Hidden figures: is improving family functioning a key to better treatment outcomes for seriously mentally ill children? Resid Treat Child Youth. 2019;37(1):46–64. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2019.1589405 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Green J, Kroll L, Imrie D, et al. Health gain and outcome predictors during inpatient and related day treatment in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(3):325–332. doi:10.1097/00004583-200103000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grizenko N. Outcome of multimodal day treatment for children with severe behavior problems: a five-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):989–997. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kerr D, Lunkenheimer E, Olson S. Assessment of child problem behaviors by multiple informants: a longitudinal study from preschool to school entry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(10):967–975. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]