Abstract

Background

Over the last 31 years, there have been several institutional efforts to better recognize and reward clinician teachers. However, the perception of inadequate recognition and rewards by clinician teachers for their clinical teaching performance and achievements remains. The objective of this narrative review is two-fold: deepen understanding of the attributes of excellent clinician teachers considered for recognition and reward decisions and identify the barriers clinician teachers face in receiving recognition and rewards.

Methods

We searched OVID Medline, Embase, Education Source and Web of Science to identify relevant papers published between 1990 and 2020. After screening for eligibility, we conducted a content analysis of the findings from 43 relevant papers to identify key trends and issues in the literature.

Results

We found the majority of relevant papers from the US context, a paucity of relevant papers from the Canadian context, and a declining international focus on the attributes of excellent clinician teachers and barriers to the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers since 2010. ‘Provides feedback’, ‘excellent communication skills’, ‘good supervision’, and ‘organizational skills’ were common cognitive attributes considered for recognition and rewards. ‘Stimulates’, ‘passionate and enthusiastic’, and ‘creates supportive environment’, were common non-cognitive attributes considered for recognition and rewards. The devaluation of teaching, unclear criteria, and unreliable metrics were the main barriers to the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers.

Conclusions

The findings of our narrative review highlight a need for local empirical research on recognition and reward issues to better inform local, context-specific reforms to policies and practices.

Abstract

Contexte

Depuis 31 ans, nous sommes témoins d’efforts institutionnels visant à offrir aux cliniciens enseignants une plus grande reconnaissance et à récompenser leur travail. Cependant, d’après leur perception, la valorisation de leurs réalisations en matière d’enseignement clinique demeure insuffisante. Cette revue narrative a un double objectif : d’une part, repérer les qualités qui sont prises en considération en vue de l’octroi d’une reconnaissance officielle ou de l’attribution de récompenses (prix) aux cliniciens enseignants et d’autre part recenser les éléments qui empêchent certains candidats de se voir accorder une telle reconnaissance ou récompense.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans OVID Medline, Embase, Education Source et Web of Science pour repérer les articles pertinents publiés entre 1990 et 2020. Le contenu des résultats des 43 articles sélectionnés a ensuite été analysé pour dégager les principales tendances et questions abordées.

Résultats

La plupart des articles pertinents se rapportaient au contexte des États-Unis. En revanche, peu d’articles pertinents concernaient celui du Canada. Sur le plan international, la question des qualités des cliniciens enseignants et des éléments qui peuvent les empêcher d’obtenir la reconnaissance ou une récompense suscite moins d’intérêt depuis 2010. Le fait « d’offrir de la rétroaction », d’avoir « d’excellentes habiletés de communication », d’assurer une « bonne supervision », et un bon « sens de l’organisation » sont des compétences cognitives souvent considérées pour l’octroi de la reconnaissance et l’attribution de récompenses. Parmi les compétences non cognitives, on note le fait d’être « stimulant », d’être « passionné et enthousiaste » et de « créer un environnement offrant du soutien ». La dévalorisation de l’enseignement, le manque de critères clairs et l’utilisation de mesures d’évaluation peu fiables sont les principaux obstacles à l’octroi de la reconnaissance ou à l’attribution d’une récompense aux cliniciens enseignants.

Conclusions

Les résultats de notre revue narrative mettent en évidence la nécessité de mener des recherches empiriques localement en matière de reconnaissance et de récompense afin d’éclairer les réformes locales des politiques et des pratiques dans le milieu spécifique où elles sont appliquées.

Introduction

The mission statement of many medical schools describes the teaching of students and residents as their fundamental mission.1–3 Teaching excellence is also a central theme in recognition and reward policies and guidelines in medical schools.3,4 Yet, medical schools continue to focus on rewarding faculty for research and clinical service contributions, while placing lesser prominence on teaching and educational contributions.2,5–7 This problem has contributed to the beleaguerment, poor recruitment and retention of the clinician teaching workforce.2,8–10 Professional medical organizations and academics in Canada and the US have acknowledged the presence and consequences of this recognition and reward problem,2,11,12 as evidenced by the repeated calls over the last three decades for Academic Medical Centres (AMCs) to reform recognition and reward policy and practices to better recognize and reward teaching.2,11,12

AMCs have sought ways to respond to North American calls for reform and to reduce local workforce related concerns2,6,7,13 by developing career pathways for clinicians focusing on patient care and clinical teaching and/or education activities,2,8,14–18 and developing guidelines to evaluate teaching excellence.3,19–22 There were also major increases in the use of teaching dossiers to document teaching achievements for high-stakes decisions,23,24 and the development of faculty development (FD) programs14,25,26 and teaching academies27,28 to foster clinician teachers' excellence. However, the success of such efforts to improve the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers has been limited.7

Across AMCs today, there remain suboptimal recognition and reward of clinical teaching practices for faculty.7,29,30 The persistence of this problem is a concern in the US and Canada because recognition and rewards are key predictors of faculty satisfaction,31–36 motivation,22,37 and morale.19,22 A 2013 study published in CMEJ from the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry identified the enablers and barriers to clinician tutor motivation and satisfaction.38 The authors reported that reforms, such as limiting heavy time commitments for tutoring, could help to improve clinician tutor motivation, satisfaction and ultimately their recruitment and retention at the institution.38

Anecdotal evidence from our school of medicine in Ottawa similarly suggests a need to identify and address the factors influencing dissatisfaction and disengagement among clinician teachers. Our first step is to conduct a review to deepen our understanding and in turn inform our local empirical research around the recognition, reward, and workforce related issues that clinician teachers may face. We start by looking at the literature on the attributes of the excellent clinician teachers that are critical for recognition and reward decisions. AMCs often set standards for high-quality clinical teaching, using terms such as ‘demonstrated excellence,’ in decisions to recognize and reward clinician teachers.3,22,39 However, there is no widely accepted standardized criteria or definition as to what constitutes an excellent clinician teacher.3,40 Rather, the literature often outlines the skills and behaviours that constitute teaching excellence. This review provides the first synthesis of the literature on the skills and behaviors of ‘excellent’ clinician teachers. This will give insight into how clinician teacher performance is determined for the purposes of recognition and reward decisions. Considering the persistence of the inadequate recognition and reward problem, we also provide a synthesis of the literature on the barriers that contribute to this recurring problem in Canada and abroad. The research questions for this review are as follows:

How is an excellent clinician teacher defined in the medical education literature?

What are the barriers that contribute to the problem of poor recognition and rewards for clinicians who are mainly responsible for clinical teaching and patient care?

Our narrative review findings will identify key trends and issues from the literature evidence, and help to generate research topic areas for future exploration.41 The review findings will also deepen our understanding of the nature of the recognition and reward problem internationally, and in particular within Canada. The purpose of the latter focus is to determine what contributions can be made to improving policies and practices within Canadian medical education settings.

Methods

Design

This review employed a narrative review approach.42–44 The review approach involves the synthesis of the literature on the two review topics from a diversity of sources, including primary research articles and commentary/opinion papers.43,45,46 We used several narrative review guidelines to inform the research process since the best practice guidance on composition, process, and reporting of narrative reviews has, and continues to evolve.42,43,46-49 We adapted a modified form of a narrative review to improve transparency and methodological rigour.46-48,50 First, we borrowed some systematic review methods to avoid the traditional pitfalls associated with narrative reviews.43,46–48 Specifically, we used a systematic approach for searching, selection, and analysis.46-48,50 Second, we provided an audit trail of our review methods.47 In terms of reporting, we synthesized the textual data into tables,48 organized the main texts into subsections,48 and emphasized the key trends from the findings in the text.47

Information sources and search strategies

AWF and CG undertook preliminary searches and reviewed the literature on excellence in clinical teaching and challenges in rewarding teachers for a local internal institutional white paper in July 2020. The search enabled the review team to peruse the type of information being reported and to amend the search parameters.42 We also found that no existing reviews had addressed our review questions.42 In December 2020, we performed electronic searches with support from an information specialist (KF) in the following databases: Medline, Embase, Education Source, and Web of Science. We selected these databases to overcome limitations of single database searching and to attain a reasonable breadth and depth of textual data.42,47 AWF and KF developed the search strategies for these databases using a combination of database specific subject headings and keywords. The terms included synonyms and truncations of the following: ‘physician’, ‘clinician’, ‘medical’, ‘teaching’, ‘excellent’, ‘performance’, ‘reward’, ‘recognition’, ‘promotion’. We retrieved all peer-reviewed publications from January 1990 to the date of search, December 11, 2020. This year range covers a period when AMCs increased their efforts to improve recognition and reward policy and practices.2,6,13,15

Eligibility criteria

We included documents that fulfilled the criteria displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Category | Eligibility Criteria |

|---|---|

| Focus | 1) Focused exclusively on the papers that evaluate and report the attributes of excellent clinician teacher performance for recognition and reward decisions. The medical education literature refers to excellent clinicians through a range of concepts, including high-quality, good, great, among others.51–54 Papers that report such attributes merely for the purposes of general feedback or to inform program development are excluded. 2) Focused exclusively on papers that report the barriers to institutional recognition and rewards for clinician teachers’ teaching contributions and achievements. |

| Source of information | Papers were included if they gather the perspectives of clinician teachers, organizational leaders involved in clinical education, or experts (i.e., clinicians with opinion pieces) on this topic. The terms clinical/ clinician educator and clinical/clinician teacher are often used interchangeably or generically in the medical education literature. Clinician teachers often devote most their time patient care and clinical teaching, while clinician educators tend to take on education theory/ scholarship and curriculum development in addition to some patient care and teaching responsibilities.18,55 In this review, we focus on the recognition and reward problem experienced by clinicians with major patient care and clinical teaching responsibilities.14,18,56 |

| Types of publications | A primary research article, review, or comment/ opinion paper (i.e., commentary, reflection, perspective). |

| General characteristics | 1) Published in a peer-reviewed journal since Jan 1990. 2)Written in English. 3) Available in a full-text version. Documents were accessed through the library RACER request forms if immediate full-text versions were not found. |

Screening and selection process

We imported the records retrieved from database searching into Covidence for the automatic removal of duplicates and screening. The first reviewer (AWF) first screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved records against the eligibility criteria. AWF passed records that were relevant or unclear onto full-text screening, and discarded records that clearly did not fit the eligibility criteria. AWF then screened the full-text documents of the retained records, passing documents that were relevant into the extraction phase, while excluding the documents that were irrelevant. AWF resolved uncertainties about inclusion of certain records through discussion with a second reviewer (SK) during both screening phases. In addition, AWF manually perused the reference lists of included papers to identify additional relevant records that may have been missed through database searching.57 AWF also manually perused the reference lists of ineligible reviews that had included studies that were potentially relevant.58–65

Extraction

Step 1. We developed a coding manual and a first version of an extraction sheet (coding sheet) on Microsoft Excel from the literature. The coding sheet includes the codes (categories) that we developed a priori using concepts from relevant literature.66 AWF and SK then independently piloted the coding manual and extraction sheet on three separate papers. We compared our coding results in an inter-coder reliability session and made the necessary modifications to the coding manual and extraction sheet to ensure consistency and clarity at the screening and coding stages.67 This step occurred prior to the full-text screening phase.

Step 2. The final, revised extraction sheet consists of two components. In the first component, AWF extracted the general characteristics and key demographic information from the papers (authors, publication year, publication type, research approach, source of information). The second component of the final extraction sheet consists of the coding concepts that AWF developed from the literature on attributes of excellent clinician teachers and the barriers that clinician teachers may face in receiving recognition and rewards (see Appendix A for definitions of coding concepts). AWF created a few emergent codes as addenda in cases when the a priori codes did not sufficiently capture the relevant text.66

AWF first extracted the cognitive and non-cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers from relevant papers. Our use of ‘cognitive’ and ‘non-cognitive’ attributes is informed by previous reviews, in terms of the categorization of attributes according to this binary.53,60 Cognitive attributes involve conscious intellectual effort, such as thinking and reasoning, and are related to the knowledge gain or imparting of knowledge to learners (refer to the cognitive attributes terms in the descriptive narrative results section).60 Non-cognitive or ‘soft’ attributes are generally related to clinician teachers’ personalities and attitudes. They may involve intellectual effort, but are more indirect and less consciously driven than cognitive attributes (refer to the non-cognitive attributes terms in the descriptive narrative section).60 AWF then extracted information on the barriers faced by clinician teachers in receiving recognition and rewards for their performances. AWF and SK resolved uncertainties through discussion.

Method of analysis

A narrative review can be conducted using a number of distinct methodologies.43 A content analysis is a useful method for transforming all data from various types of papers into frequencies and percentages.49,68,69 Interpretation is largely before and/or after synthesis. As per content analysis procedures, we identified the frequencies and percentages of the coding concepts across the dataset.66 This enabled the tabulation and clustering of information with similar findings and levels of evidence, revealing key trends and outliers in the data.50,70 We reported on the landscape of events71 that occurred between 1990 and 2020 in Canada, US and other regions.

Results

Study selection

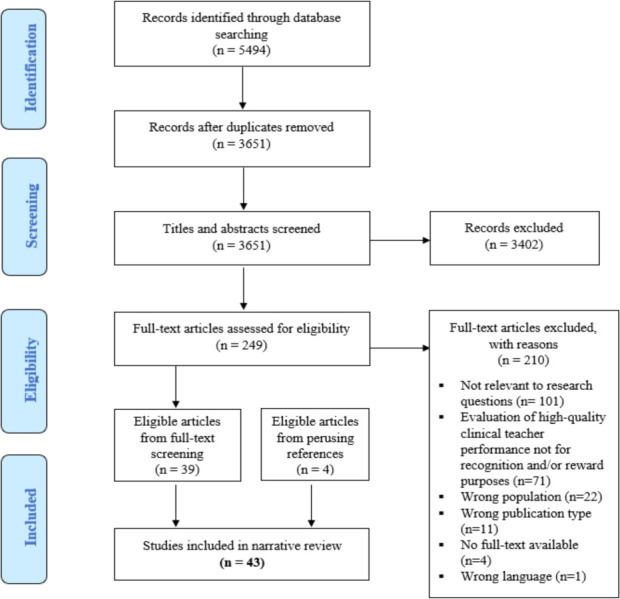

The database search yielded 5494 potentially relevant records. Following the removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, we retained 249 records that appeared relevant for full-text screening. We retained 39 records for inclusion in the review following retrieval and review of the full texts of these papers against the eligibility criteria (see Figure 1). We retrieved an additional four relevant records from perusal of the reference lists of the included papers, for a total of 43 papers.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection process

General characteristics of included papers

Period and geographic contributions: We compiled the general characteristics of the included papers in Table 2. The majority of the papers (34/43; 79.1%) included in this review originated from North America. There is a paucity of research from Canada however as only 6/43 (13.9%) papers (including 3 in both Canada and US) were part of Canadian studies or were authored by a Canadian,15,30,72–75 while 31/43 (72.1%) were from the US context.3,7,15,16,72,73,76-79,80-101 The rest of the reviewed papers originated from Asia (4/43; 9.3%),102–105 Europe (2/43; 4.7%),106,107 Africa (2/43; 4.7%),3,108 and Oceania (1/43; 2.3%).109 Eleven papers (25.6%) were published between 1990 and 1999,15,16,72,76,81,92,97,98,100,101,108 23 papers (53.5%) were published between 2000 and 2009,3,73,77-80,82-84,86–91,93–95,99,102-104,106 and nine papers (20.9%) were published between 2010 and 2020.7,30,74,75,85,96,105,107,109

Table 2.

Summary description of included studies

|

Descriptive characteristic |

Number of papers a |

|---|---|

| Year of Publication (range) | |

| 1990-1999 | 11 |

| 2000-2009 | 23 |

| 2010-2020 | 9 |

| Countryb | |

| USA | 31 |

| Canada | 6 |

| Japan | 3 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Australia | 1 |

| Qatarc | 1 |

| Singaporec | 1 |

| UAEc | 1 |

| Publication Type | |

| Opinion paper/commentd | 21 |

| Primary research article | 22 |

| Research Paradigm | |

| Quantitative | 16 |

| Qualitative | 4 |

| Mixed | 2 |

| N/A | 21 |

| Source of Informatione | |

| Clinician teachers/educators (clinical faculty with a primary focus on clinical service and teaching/education) | 12 |

| Expert opinion (e.g., faculty with clinical experiences) | 21 |

| Trainees (medical students, residents) | 7 |

| Organizational leaders/decision-makers (e.g., deans, promotion committee chairs, clinical department heads) | 5 |

aNumber of papers indicates those papers in which each characteristic was reported

bFour of the references originated out of multiple countries

cOne of the references105 includes a multi-site study that reports findings from three countries in Asia.

dNLM refers to commentary, editorial comment, viewpoint, perspective type papers as work consisting of a critical/explanatory note written to discuss, support, or dispute other works previously published

eThe source of information refers to the target participants in primary research articles (e.g., clinician teachers) and to the authors of position papers. Three of the references had more than one source of information.

We found a significant increase in the number of publications from 1990-1999 period to the 2000-2009 period (+12), but a significant decrease in the number of publications from the 2000-2009 period to the 2010-2020 period (-14) (Table 2). In the Canadian context however, there was no such trend as two papers were published in 1990-99,15,72 one paper in 2000-2009,73 and three in 2010-2020.30,74,75 Canada is tied for the most publications (3) between 2010-2020 with the USA, which conversely saw a significant decrease in publications in this period (-16) (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, primary research articles and position papers contributed a similar number of publications in each time period.

Table 3.

The contribution of papers by geographic origin and publication type

| Time Period | Geographic Region | Publication Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | Canada | Otherb | Primary research | Opinion paper | |

| T1 (1990-1999) | 9a | 2 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| T2 (2000-2009) | 19 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 11 |

| T3 (2010-2020) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

aThree of the papers originated from both Canada and the US

bAsia, Africa, Europe, Oceania

Type and source of information: Over half (22/43; 51.2%) of the papers we reviewed were primary research articles, most of which were quantitative, published in the 2000-2009 period, and originating out of the US (Table 2). These primary research articles reported information from a variety of sources: 12/22 (54.5%) from clinician teachers;15,75,76,82–84,86–88,105,107,109 7/22 (31.8%) from students and residents;76–81,106 5/22 (22.7%) from organizational leaders and decision-makers such as deans and promotion committee chairs.15,72,73,85,108 The remaining 21/43 reviewed papers (48.8%) were comment and opinion type papers from experts, such as faculty with clinical experiences or medical education researchers.3,7,16,30,74,89-104

Descriptive narrative of coding concepts

Table 4 and Table 5 summarize the distribution of the coding concepts that we developed from the literature related to 1) the attributes of excellent clinician teachers and 2) the barriers to their recognition and reward, respectively.

Table 4.

Attributes of excellent clinician teachers considered for recognition and reward decisions

| Coding Concept | Time Period | Geographic Regiona | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes of Excellent Clinician Teachers | All Included Papers (n = 9) | 1990-1999 (n = 3) | 2000-2009 (n = 6) | 2010-2020 (n = 0) | Canada (n = 2) | USA (n = 8) | Other (n = 1) |

| Cognitive Attributes (n = 10) | |||||||

| Provides feedback | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Excellent communication skills | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Good supervision | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Well-organized | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Clinical competence | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Self-evaluates | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Professional | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3a | 0 |

| Medical knowledge | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Scholarly | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Administration skills | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-cognitive Attributes (n = 7) | |||||||

| Stimulates | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Passionate and enthusiastic | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Creates supportive environment | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Adapts teaching | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Is respectful and personable | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Is approachable | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Role models | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

Table 5.

Barriers to receiving recognition and rewards for clinician teachers’ performances

| Coding Concept | Time Period | Geographic Regiona | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | All Included Papers (n = 36) | 1990-1999 (n = 9) | 2000-2009 (n = 18) | 2010-2020 (n = 9) | Canada (n = 6) | USA (n = 25) | Other (n = 8) |

| Teaching undervalued | 26 | 7 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 17 | 7 |

| Unclear criteria | 21 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 4 |

| Unreliable evaluation metrics | 19 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 4 |

| Lack of reward/recognition opportunities | 15 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 8 |

| Poor administrative support | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Inaccessibility of mentors | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-conducive clinical teaching environment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Culture clash | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| External pressure | 13 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 3 |

| Cumbersome | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Disconnection | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

Cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers: Among the nine papers that reported on “cognitive attributes” of excellent clinician teachers, we found that “provides feedback” to learners was the most frequently reported attribute (6/9; 66.7%).77–81,106 Several papers also frequently mentioned attributes related to “well-organized,”76–78,106 “excellent communication skills,”76–79,106 and “good supervision.”77,79–81,106 None of the papers identified attributes related to administration skills, while only two papers (22.2%) discussed attributes related to being a scholarly clinician teacher.76,106 Only one of these papers gathered the perspectives on the matter from clinician teachers themselves,76 while seven papers gathered this information from residents or students.76–81,106

In terms of geographical contributions, we only found two cognitive attributes, “professional” and “clinical competence,” from the Canadian context (2/9; 22.2%).72,73 With respect to periodic contributions, papers published in the 1990-1999 period mostly reported the attributes “well-organized”76,81 and “clinical competence”.72,76 The most reported cognitive attributes in the 2000-2009 period were “provides feedback,”77–80,106 “good supervision skills,”77,79,80,106 and “excellent communication skills.”77,79,80,106 There were no publications that reported on cognitive attributes between 2010-2020.

Non-cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers: The papers that reported on non-cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers (7/43; 16.3 %) most frequently discussed the coding concept “stimulates” (5/7; 71.4%).76,78–80,106 Several papers also frequently reported “passionate and enthusiastic” (4/7; 57.1%)77,79,81,106 and “creates supportive environment” (4/7; 57.1%)77,78,80,106 as non-cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers. We did not find a non-cognitive attribute in any of the Canadian papers. In terms of the periodic contributions, there were no mentions of the coding concept “creates a supportive environment” in the 1990-1999 period. However, “creates a supportive environment” was tied for the most reported non-cognitive attribute in the period of 2000-2009.77,78,80,106 There were no publications that reported on non-cognitive attributes between 2010-2020.

Barriers to receiving recognition and reward for clinician teacher performances: The majority of the included papers (36/43; 83.7%) discussed the challenges that clinician teachers face in receiving recognition and reward for their performances (Table 5). We found that “teaching undervalued” was discussed as a barrier in 26/36 papers (72.2%).3,7,15,74,75,82,83,86-89,91-93,95,97-104,107-109 We found many discussions around the issues of “unclear criteria” (21/36; 58.3%),3,15,16,72,73,84-87,89-93,96,99-101,107-109 “unreliable evaluation metrics” (19/36; 52.8%),3,15,16,30,72,74,75,85,90,92,93,94,96,99-102,104,107, and “lack of reward opportunities” (15/36; 41.7%)3,15,72,75,83,90,98,100,102-105,107-109 as well. There were also frequent discussions pertaining to “culture clash” (8/36; 22.2%)3,73, 82,94,95–98 and “external pressures” (13/36; 36.1%).3,7,15,83,90,92,93,95,96,100-102,109 No paper discussed challenges relating to the environment of the clinical settings, such as the competition between clinical practice and clinical education for space and time.

The six Canadian papers most frequently discussed barriers related to “unreliable evaluation metrics” (5/6; 83.3%),15,30,72,74,75 “teaching undervalued” (3/6; 50%),15,74,75 “unclear criteria” (3/6; 50%)15,72,73 and “lack of reward/recognition opportunities” (3/6; 50%).15,72,75 As shown in Table 5, these four barriers were also the most reported barriers in the US and other regions of the world Nine of the papers related to barriers to recognition and reward were published in the 1990s (Table 5). The most frequently mentioned barriers in the 1990s were “unclear criteria” (7/9;77.8%),15,16,72,92,100,101,108 “teaching undervalued” (7/9;77.8%),15,92,97,98,100,101,108 “unreliable evaluation metrics” (6/9; 66.7%),15,16,72,92,100,101 and “lack of reward/recognition opportunities” (5/9; 55.6%).15,72,98,100,108 Over half of the 18 barrier related papers that were published in the 2000s discussed issues related to “teaching undervalued” (14/18; 77.8%).3,82,83,86-89,91,93,95,99,102-104 We also found ongoing discussions pertaining to “unclear criteria” (10/18; 55.5%)3,73,83,84,86,89-91,93,99 and “unreliable evaluation metrics” (7/18; 38.9%)3,90,93,94,99,102,104 in the 2000s. The nine papers published in the period of 2010-2020 again showed a similar trend to earlier periods, with most of these papers discussing issues related to “unreliable evaluation metrics” (6/9; 66.7%)30,74,75,85,96,107 and “teaching undervalued” (5/9; 55.6%)7,74,75,107,109 as barriers.

Discussion

Summary of review

The purpose of this review was to synthesize the findings of papers published between 1990-2020 that examined the two following topics: 1) The attributes of excellent clinician teachers that are considered for recognition and reward decisions; 2) The barriers to the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers’ performances and achievements. Below, we provide a structured discussion of our interpretation of the results to inform our conclusions and the implications of the review findings for policy, practice, and future research.

General characteristics of included papers

The papers included in this review originate from five different continents, suggesting a breadth of knowledge on the recognition and reward problem from various contexts. However, the majority of the included papers originate from the US context. The paucity of findings from other settings, including Canada, raises questions as to whether poor recognition and reward policy and practices is a low priority problem or whether there is simply an absence of reporting on the problem. There is clearly a link between healthcare practice and training contexts that requires further investigation. The lack of attention to these issues outside of the US, in particular, requires additional forms of historical data analysis that are outside the scope of this review (i.e., contextualised healthcare and health professions history, culture and structure investigation). However, in this review the concentration of papers emanating from the US does lend itself to a partial analysis in terms of policy development around clinical teaching workforce needs.

The significant increase in the number of publications from the 1990s into the 2000s out of the US represents an increased focus on recognition and reward policy and practices of the US clinician teaching workforce. This trend parallels the rising concerns in that time period among AMCs and medical organizations, such as the AAMC, about clinician teacher satisfaction, retention and recruitment.2,10,14,55,110 Another possible explanation for the high number of publications in the 2000s are the many reforms that occurred in the period, such as the increase in career pathways for clinicians with major teaching responsibilities.2,14,89

The significant decrease in the number of publications in 2010-2020 compared to 2000-2009 raises a key question. Has the recognition and reward problem been resolved in the US or elsewhere in the last 11 years? We speculate that the problem has not been resolved, given the number of studies in the US and abroad reporting on the continued discontent and attrition of clinician teachers between 2010 and 2020.28,34,75,111–113 This raises another question as to whether the significant decline in the number of publications from 2000-2009 to 2010-2020 is perhaps due to a prioritization of other institutional issues and undergoing reforms.

Cognitive and non-cognitive attributes of excellent clinician teachers

The diverse range of cognitive and non-cognitive attributes found in this review may explain the lack of consensus in the literature as to what constitutes excellent clinical teaching. It may also explain why few or no standardized measures exist to assess clinical teaching excellence, and why criteria for clinical teaching excellence may benefit from being informed by local context-specific factors. We did find unique trends in terms of the frequency of the reporting of the attributes, which can be explained by changes in paradigm shifts in the 1990s and 2000s.

We found that organizational skills and clinical competence were the most reported cognitive attributes in the 1990s, whereas there was increased emphasis on feedback, communication and supervision related cognitive attributes during the 2000s. This trend aligns with paradigm shifts in teaching and learning, and the changes in the roles, responsibilities and required skills of clinician teachers in the same period.14,114,115 For example, the transitions away from lecture based teaching to earlier clinical teaching altered faculty job descriptions.14,114 This transition dramatically increased clinician teachers’ responsibilities and accountability to directly observe, assess and provide structured feedback to trainees.55,116 In terms of non-cognitive attributes, we found that “creating a supportive environment” in the clinic was among the most reported non-cognitive attributes in the 2000s, even though it was not reported in any of the papers from the 1990s. The increased shift to clinic-based teaching and learning from lecture-based learning in this period14,114 could be a major influencing factor resulting in the increased emphasis on a supportive clinical environment.

Seventy-one studies that defined the skills and behaviours of excellent clinician teachers for general feedback to faculty, or to inform FD programs were identified during our screening process.51,117–124 Our analysis demonstrated that there is a lack of evidence concerning the key perceived attributes of excellent clinician teachers that underpin recognition and reward decisions, with no new articles published on the topic in over a decade.77 The lack of publications that define and clearly delineate what constitutes excellence in clinical teaching for recognition and reward decisions is a clear barrier to understanding this phenomenon and its potential effects on the clinical teaching workforce.

Barriers to recognition and reward

The papers in this review revealed three major barriers that recurrently contributed to the inadequate recognition and reward problem in North America over the last 31 years: the devaluation of teaching, unclear criteria, and unreliable evaluation metrics.

One particular issue we found in the literature was the variation in the views of clinical department chairs, reward committee members and/or clinician teachers.72,73,84 This reflects a misalignment in understanding among these stakeholders of the requirements that are critical for recognition and reward decisions. We also found common discussions of other issues internationally, such as external time and financial pressures,7,90,92 and culture clashes resulting from the differing priorities of clinical departments and clinical teaching faculty.82,95 These barriers raise questions as to how recognition and reward practices are really valued across AMCs.

The inequities in the priority and support for teaching in the structures, processes, and cultures are reflected in institutional policies and practices.7 It is evident from our findings that the various barriers to the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers are indeed structural, procedural and cultural. Given the frequency of the coding concepts related to the devaluation of teaching and clashing cultures, the review findings suggest that cultural barriers are at the forefront of the recognition and reward problem. This is consistent with what is reported in the recent literature, in that medical education culture continues to value and better support research endeavors over teaching.7,29,125 We contend that structural reorganizations or process changes without cultural reforms (i.e., instituting a belief system that teaching is truly as important as research) will likely fail to alter value systems, and fail to raise the epistemic standing of clinical teaching excellence. This is a particularly difficult issue to address as cultural reform in medical education has been met with hidden curriculum challenges.126,127

We would suggest that the barriers to adequate acknowledgment of clinician teachers send messages about the institutions’ value system and commitment to fostering clinical teaching excellence.128 They are the property of a hidden curriculum which is embedded within the very structure and processes of institutional recognition and reward systems, that we argue serves to undermine the value of clinical teaching. Consequently, a major finding in this review is that clinician teachers may infer from these messages that teaching is not a rewarding or worthwhile activity.102,103,107 This perception may also serve to reduce some clinician teachers’ motivations and impetus to strive for excellent standards of clinical teaching performance and consequently, may have negative downstream effects on the quality of learning and patient care.36,55,75

Implications for the Canadian context

The review findings from the Canadian context suggest that the recognition and rewarding of clinical teaching faculty is not a well recognized nor investigated problem. We found only three papers published since 2010 from the Canadian context.30,74,75 These papers suggest some ongoing interests and concern about the need for reforming recognition and reward policies and practices of clinical teaching in Canada. The latest paper by Wisener and colleagues, a 2020 primary research study from Western Canada, found that impersonal, inefficient and poorly framed rewards caused clinician teachers to feel unvalued and disconnected.75 The implementation of rewards can be as important as the notion of the reward itself. Clinician teachers’ perspectives that rewards were impersonal and poorly framed can further reflect the unique needs of each individual clinician teacher generated in their local context. It would seem that there is no one-size fits all strategy that can adequately reward all clinician teachers, which we suggest emphasizes the importance of intensive research to understand the local perspectives and experiences of Canadian clinician teachers.

The paucity of Canadian-based research on the perspectives and experiences of clinician teachers in this review is concerning. On the one hand, it could indicate that Canada does not have a hidden curriculum in clinical teaching that devalues the practices and achievements of the teaching workforce. On the other hand, it could represent that the lack of attention to this issue is actually the result of a hidden curriculum and is a demonstration of the poor acknowledgement and understanding of the unique perspectives and needs of clinical teaching faculty within Canadian AMCs. We suspect the latter phenomenon is at play. If we are to address this problem, we suggest that recognition and reward systems should be refined by uncovering the perceptions of clinician teachers about the current system of recognition and rewards, what they truly value, and what they perceive is valued by their institution. It would seem from our review findings that this principle is not practiced to any great extent in Canada, despite the fact that the ‘Enabling Recommendation E’ from The Future of Medical Education in Canada (FMEC) Project in 2010 states that priority needs to be given to the support and recognition of teaching as part of FD initiatives.129 Our review findings, along with the FMEC recommendation to increase the recognition for teaching, should be a wakeup call to Canadian AMCs to conduct intensive, localized needs assessment research to learn about the unique needs of their clinician teachers and to generate appropriate modes of recognition and reward for their endeavours. To do otherwise might result in the creation of attraction and retention problems within the clinician teaching workforce now, and into the future.

In response to local anecdotes of clinician teacher dissatisfaction and the results of this narrative review, we plan to conduct a localized needs assessment study in the Faculty of Medicine, at the University of Ottawa. Our team will analyze local policy documents and key stakeholder interviews to generate an understanding of the perspectives of clinician teachers and organizational leaders on the policies and practices of recognizing and rewarding clinical teaching excellence. We will use the concept of hidden curriculum as a lens through which to enrich our understanding of the local barriers and facilitators, with the express purpose of guiding the production of effective local recognition and reward policy and practice reforms.

Limitations

We acknowledge a few limitations of this review. The small number of papers related to the attributes of excellent clinician teachers did not enable us to compare stakeholder perspectives. Secondly, we found more opinion/comment type papers than empirical data discussing the barriers for the recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers. Our search was limited by the exclusion of grey literature and only included papers published in English. Together, these limitations may have reduced the comprehensiveness of our review findings. Lastly, the period of January 2010 to December 2020 includes papers spanning 11 years, while 1990-1999 and 2000-2009 include 10 years each. Although this creates an unequal comparison, the key message of a declining focus from the period of 2000-2009 to 2010-2020 remains.

Conclusion

In this review, we attempted to deepen our understanding of the attributes of excellent clinician teachers and underlying barriers contributing to the recognition and reward problem. Our findings revealed the following: 1) There is a paucity of research on the recognition and reward problem outside of the US context, and a declining number of publications since 2010; 2) There are a variety of cognitive and non-cognitive attributes for excellent clinical teaching; 3) The main, recurrent barriers that contribute to the inadequate recognition and rewarding of clinician teachers include the devaluation of teaching, unclear criteria, and unreliable evaluation metrics.

For local research efforts, we recommend the triangulation of data from local policy documents and practices in order to identify (mis)alignments between what is represented by the institution and what is actually perceived by clinician teachers. Research efforts and reforms that are informed by a localized approach, with buy-in from key stakeholders (organizational leaders, reward committees, clinician teachers), can help to improve the satisfaction and engagement of teachers, and ultimately the quality of teaching, learning, and patient care.

Appendix A. Definitions of coding concepts

| Coding Conceptsa | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Attributes | |

| Provides feedback | Excellent clinician teachers assess and evaluate trainees and peers, providing clear, prompt, constructive and effective feedback.60,63,65 |

| Excellent communication skills | An excellent clinician teacher has highly developed communication skills to interact with patients, families, members of the health care team, and students. Clinician teachers with excellent communication skills also articulate their thought processes used to make clinical decisions with clarity and in language their learner understands. They are able to provide clear, simple and logical explanations. In addition, excellent clinician teachers can use effective illustrations and anecdotes.53,60–62,65 |

| Good supervision | Excellent clinician teachers provide direct and competent supervision and direction to trainees. High-performing clinician teachers delegate and actively engage trainees, giving them opportunities to carry out procedures.53,60,62,63,65,130 |

| Well-organized | An excellent clinician teacher is well organized and prepared for teaching, has sound instructional plans set out for teaching. A well-organized clinician teacher also specifies and defines objectives and expectations.53,60,131 |

| Clinical competence | An excellent clinician teacher demonstrates clinical competence and aptitude, technical expertise, ability to make good judgements and quick decisions, and clinical reasoning skills. These excellent teachers further demonstrate skills in managing patients and applying research evidence in clinical practice.53,60,62,63 |

| Self-evaluates | An excellent clinician teacher reflects on their teaching, making use of reflective processes, logs, diaries, the exchange of ideas, dialogue, and discussion. An excellent teacher is also sensitive and welcoming of student, resident and peer feedback on their teaching and clinical performance.60,130 |

| Professional | An excellent clinician teacher demonstrates professionalism and commitment to lifelong learning, training and development as both a physician and as a teacher. An excellent clinician teacher also has high standards of professional and personal values in relation to patients and their care and takes pride in their work.60,62,65,130 |

| Medical knowledge | An excellent clinician teacher demonstrates knowledge and expertise, mastery of subjects, knowledge of general medicine, and understanding of the multicultural society in which medicine is practiced.53,60,62,63 |

| Scholarly | An excellent clinician teacher effectively conducts research and understands various research methods.60,131 |

| Administration skills | An excellent clinician teacher demonstrates skills in administrative roles.53,60 |

| Non-cognitive Attributes | |

| Stimulates | An excellent clinician teacher motivates, inspires and encourages trainees to learn the practice of medicine. Excellent teachers inspire learners to think beyond facts and to ask questions. Excellent teachers also stimulate learners’ intellectual curiosity and self-directed learning. Excellent teachers further facilitate students’ clinical reasoning and encourage learners’ independence of thought.60,62 |

| Passionate and enthusiastic | Excellent clinician teachers have enthusiasm and passion for both medicine and teaching. Enthusiastic teachers are positive, maintain eye contact, nod, and are genuinely thrilled to be teaching.53,60–62,130,131 |

| Creates supportive environment | Excellent clinician teachers create a positive and supportive learning environment by being supportive. They exhibit patience, humility, openness to suggestions and questions. Excellent clinician teachers also give latitude to learners to discover their own style and develop own method of practice.53,61 |

| Adapts teaching | Excellent clinician teachers are alert to gaps and deficiencies in trainee’s education and are able/flexible to adapt teaching to learner’s specific needs and levels. They also provide individual attention and an individualized teaching approach to trainees.53,60,131 |

| Is respectful and personable | Excellent clinician teachers are friendly/polite, tactful, and do not belittle learners and patients. Excellent clinician teachers are also respectful of different cultures and backgrounds.60,63,65,131 |

| Is approachable | Excellent clinician teachers are available, approachable and willing to help. These teachers provide time to students for discussions, questions and explanations.60,61,131 |

| Role models | Excellent clinician teachers are aware that trainees are constantly watching their actions and behaviors (good and bad). For that reason, these teachers role model good professionalism, competence, and attitudes. These teachers set good examples through their behaviors and actions and behave in a manner that is consistent with what they express as good clinical care. They also explicitly articulate the process behind their actions. Excellent clinician teachers also realize the importance of modeling humanistic behaviors such as empathy and compassion.60,63,65,130,131 |

| Barriers to receiving adequate recognition and rewards for clinician teachers’ performances | |

| Teaching undervalued | The literature indicates that clinician teachers are not recognized and rewarded as well as colleagues focusing on research and patient care.29,116,125 Little or no value placed on teaching in comparison to research and clinical service, with teaching accomplishments carrying less significance.116,125 Recognition and rewards policy and practices are usually better developed for faculty who do not focus on teaching in medical schools that devalue teaching.29 |

| Unclear criteria | Poorly defined and unclear criteria are a challenge for teachers since the expectations for excellent performance tend to be vague.3,84 The criteria can be inconsistent and incongruent with the job descriptions, roles and skills/training of clinician teachers. The clarity and objectivity of recognition and reward selection processes is damaged by poor criteria and definitions of teaching excellence.3,40 Decisions about recipients of rewards for high performance can thereby appear arbitrary and/or capricious. |

| Unreliable evaluation metrics | Insufficient measures, and few valid and reliable tools to evaluate teaching.3,15,93 A common example is the reliance on student and resident ratings and testimonials as metrics to ascertain teaching excellence.15,30 These concerns are founded on findings of trainees’ struggles to separate average or competent from high-performing faculty, along with their propensity to rate based on grades and amiability.132 The lack of sensitive metrics to adequately assess performance obscures what teaching excellence is, and can complicate the pathway to teaching excellence. |

| Lack of reward/recognition opportunities | In some institutions there are no or a limited number of recognition and rewards, especially extrinsic rewards, available for teaching faculty, meaning that some excellent teachers may not get acknowledged for their accomplishments.3,108 In these institutions, recognition and rewards are mainly more common for non-teaching accomplishments, even among teaching faculty. |

| Poor administrative support | Lack of administrative support during reward application procedures, which can be complex and timely.29,30,125 |

| Inaccessibility of mentors | Absence of mentors or senior educators to guide less experienced clinicians.90,110 |

| Non-conducive clinical teaching environment | In clinical settings, clinician teachers are often required to work in tense, non-conducive environments where clinical demands and productivity are prioritized ahead of teaching.55,110 This can be reflected by the architecture of the physical space.133 |

| Culture clash | Conflicting and incongruent values, beliefs and norms between students, clinician teachers, organizational leaders, reward committee chairs, and/or the institution at large.3,82,84 For example, clinician teachers’ views of the importance of teaching may not be concordant with the views of promotion committees.84 |

| External pressure | Factors outside of the control of clinician teachers that can impact their work. Clinician teachers can experience institutional financial constraints for teaching and time constraints for participation in developmental programs.83,90,92 Clinician teachers can also experience tensions and role conflicts in the clinical environment. |

| Cumbersome | Application process for rewards can be perceived to be very time consuming and complex for already busy clinician teachers.3,30 |

| Disconnection | Clinicians can feel detached with their institution and departmental leaders, and with the recognition and reward system of their local institution.75,82,84 Some clinicians can perceive that their institution has a poor understanding of faculty needs and daily realities.75,84 |

aOur coding concepts are informed by the information presented in previous reviews, seminal primary research reports and opinion papers. However, given the overlap in the meaning of the codes across the numerous papers, the codes used in this review are adapted to reflect our interpretation of the codes.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose

Funding

There was no funding for this paper

References

- 1.Mennin S. Standards for teaching in medical schools: double or nothing. Med Teach. 1999;21(6):543-545. 10.1080/01421599978942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanson A, Anderson M. Educating medical students. Assessing change in medical education--the road to implementation. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1993;68(6 Suppl):S1-46. 10.1097/00001888-199306000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean M. Rewarding teaching excellence. Can we measure teaching “excellence”? Who should be the judge? Med Teach. 2001;23(1):6-11. 10.1080/01421590123039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean M, Cilliers F, Wyk JM Van. Faculty development: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Med Teach. 2008;30(6):555-584. 10.1080/01421590802109834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray DWR. A system of recognition for excellence in medical teaching. Med Teach. 1999;21(5):497-499. 10.1080/01421599979185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann K, Kaufman D. A response to the ACME-TRI Report: the Dalhousie problem-based learning curriculum. Med Educ. 1995;29(1):13-21. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irby DM, O’Sullivan PS. Developing and rewarding teachers as educators and scholars: remarkable progress and daunting challenges. Med Educ. 2018;52(1):58-67. 10.1111/medu.13379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley WN, Stross JK. Faculty tracks and academic success. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(8):654-659. 10.7326/0003-4819-116-8-654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aucott JC, Como J, Aron DC. Teaching awards and departmental longevity: is award-winning teaching the “Kiss of Death” in an academic department of medicine? Perspect Biol Med. 1999;42(2):280-287. 10.1353/pbm.1999.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Sackett DL. Importance of and satisfaction with work and professional interpersonal issues: a survey of physicians practicing general internal medicine in Ontario. C Can Med Assoc J 1995;153(6):755-764. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7664229 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyer EL. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges . Physicians for the twenty-first century. Report of the Project Panel on the General Professional Education of the Physician and College Preparation for Medicine. J Med Educ. 1984;59(11 Pt 2):1-208. 10.1097/00001888-198411000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Posluns E, Shafir MS, Keystone JS, Ennis J, Claessons EA. Rewarding medical teaching excellence in a major Canadian teaching hospital. Med Teach. 1990;12(1):13-22. 10.3109/01421599009010557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg L. The evolution of the clinician–educator in the United States and Canada: personal reflections over the last 45 Years. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1764-1766. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RF, Froom JD. Faculty and administration views of problems in faculty evaluation. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1994;69(6):476-483. 10.1097/00001888-199406000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovejoy FH, Clark MB. A promotion ladder for teachers at Harvard Medical School: experience and challenges. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1995;70(12):1079-1086. 10.1097/00001888-199512000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parris M, Stemmler EJ. Development of clinician-educator faculty track at the University of Pennsylvania. J Med Educ. 1984;59(6):465-470. 10.1097/00001888-198406000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherbino J, Frank JR, Snell L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014;89(5):783-789. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Searle N, Teal C, Richards B, et al. A standards-based, peer-reviewed teaching award to enhance a medical school’s teaching environment and inform the promotions process. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):870-876. 10.1097/acm.0b013e3182584130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruedrich SL, Cavey C, Katz K, Grush L. Recognition of teaching excellence through the use of teaching awards: a faculty perspective. Acad Psychiatry. 1992;16(1):10-13. 10.1007/BF03341489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brawer J, Steinert Y, St-Cyr J, Watters K, Wood-Dauphinee S. The significance and impact of a faculty teaching award: disparate perceptions of department chairs and award recipients. Med Teach. 2006;28(7):614-617. 10.1080/01421590600878051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindler N, Corcoran JC, Miller M, et al. Implementing an excellence in teaching recognition system: needs analysis and recommendations. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):731-738. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhn GJ. Faculty Development: The educator’s portfolio: its preparation, uses, and value in academic medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):307-311. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb02217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.University of Ottawa . Faculty affairs. Teaching dossier. Published May . https://med.uottawa.ca/professional-affairs/faculty/promotion-clinical/dossier-templates/teaching-dossier [Accessed May 28, 2021].

- 25.Mcleod PJ, Steinert Y. The evolution of faculty development in Canada since the 1980s: Coming of age or time for a change? Med Teach. 2010;32(1):e31-e35. 10.3109/01421590903199684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526. 10.1080/01421590600902976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berman JR, Aizer J, Bass AR, et al. Creating an academy of medical educators: how and where to start. HSS J Musculoskelet J Hosp Spec Surg. 2012;8(2):165-168. 10.1007/s11420-012-9280-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2019;94(7):963-968. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walling A. Academic promotion for clinicians: a practical guide to academic promotion and tenure in medical schools. Springer International Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penciner R. The promotion dilemma for clinician teachers. CJEM. 2019;21(1):18-20. 10.1017/cem.2018.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel L. Doctors dissatisfied with medical careers at high risk of burnout. CMAJ. 2019;191(47):e1318. 10.1503/cmaj.1095828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed N, Conn L, Chiu M, et al. Career satisfaction among general surgeons in Canada: a qualitative study of enablers and barriers to improve recruitment and retention in general surgery. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1616-1621. 10.1097/acm.0b013e31826c81b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krueger P, White D, Meaney C, Kwong J, Antao V, Kim F. Predictors of job satisfaction among academic family medicine faculty: Findings from a faculty work-life and leadership survey. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(3):e177-e185. https://www.cfp.ca/content/63/3/e177 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girod SC, Fassiotto M, Menorca R, Etzkowitz H, Wren SM. Reasons for faculty departures from an academic medical center: a survey and comparison across faculty lines. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):8. 10.1186/s12909-016-0830-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A. Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):782-785. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence and predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:37. 10.1186/1472-6920-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisener KM, Eva KW. Incentivizing medical teachers: exploring the role of incentives in influencing motivations. Acad Med. 2018;93:S52-S59. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paslawski T, Kearney R, White J. Recruitment and retention of tutors in problem-based learning: why teachers in medical education tutor. Can Med Educ J. 2013;4(1):e49-e58. 10.36834/cmej.36603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coleman MM, Richard G V. Faculty career tracks at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):932-937. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182222699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feder ME, Madara JL. Evidence-based appointment and promotion of academic faculty at the University of Chicago. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):85-95. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c64d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Archibald D, Martimianakis MA. Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews. Can Med Educ J. 2021;12(3):1-7. 10.36834/cmej.72945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101-117. 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(6). 10.1111/eci.12931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horsley T. Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2019;39(1):54-57. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Heal Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91-108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writ. 2015;24(4):230-235. 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(11):1409-1417. 10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4(1):5. 10.1186/s41073-019-0064-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews.; 2006. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf

- 50.Danilovich N, Kitto S, Price DW, Campbell C, Hodgson A, Hendry P. Implementing competency-based medical education in Family Medicine: a narrative review of current trends in assessment. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):9-22. 10.22454/FamMed.2021.453158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldie J, Dowie A, Goldie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. What makes a good clinical student and teacher? An exploratory study Approaches to teaching and learning. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):1-8. 10.1186/s12909-015-0314-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kikukawa M, Nabeta H, Ono M, Emura S, Oda Y, Koizumi S. The characteristics of a good clinical teacher as perceived by resident physicians in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:100. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bannister SL, Raszka W V, Maloney CG. what makes a great clinical teacher in pediatrics? Lessons learned from the Literature. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):863-865. 10.1542/peds.2010-0628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shysh AJ, Eagle CJ. The characteristics of excellent clinical teachers. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44(6):577-581. 10.1007/BF03015438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramani DS, Leinster S. AMEE Guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):347-364. 10.1080/01421590802061613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varpio L, Gruppen L, Hu W, et al. Working definitions of the roles and an organizational structure in health professions education scholarship: initiating an international conversation. Acad Med. 2017;92(2):205-208. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horsley T, Dingwall O, Sampson M. Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):MR000026. 10.1002/14651858.MR000026.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huggett KN, Greenberg RB, Rao D, et al. The design and utility of institutional teaching awards: A literature review. Med Teach. 2012;34(11):907-919. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fluit CRMG, Bolhuis S, Grol R, Laan R, Wensing M. Assessing the quality of clinical teachers: a systematic review of content and quality of questionnaires for assessing clinical teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1337-1345. 10.1007/s11606-010-1458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452-466. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dean B, Jones L, Garfjeld Roberts P, Rees J. What is known about the attributes of a successful surgical trainer? A systematic review. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(5):843-850. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dickinson KJ, Bass BL, Pei KY. The current evidence for defining and assessing effectiveness of surgical educators: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2020;44(10):3214-3223. 10.1007/s00268-020-05617-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kilminster SM, Jolly BC. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):827-840. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong A. Review article: teaching, learning, and the pursuit of excellence in anesthesia education. Can J Anesth Can d’anesthésie. 2012;59(2):171-181. 10.1007/s12630-011-9636-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Irby DM. Teaching and learning in ambulatory care settings: A thematic review of the literature. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 1995;70(10):898-931. 10.1097/00001888-199510000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kleinheksel AJ, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, Wyatt TR. Demystifying content analysis. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(1):7113. 10.5688/ajpe7113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Belur J, Tompson L, Thornton A, Simon M. Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociol Methods Res. 2021;50(2):837-865. 10.1177/0049124118799372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Catherine P, Nicholas M, Jennie P. synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods. McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J Dev Eff. 2012;4(3):409-429. 10.1080/19439342.2012.710641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaw L, Campbell H, Jacobs K, Prodinger B. Twenty years of assessment in WORK: a narrative review. Work. 2010;35(3):257-267. 10.3233/WOR-2010-0989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freeman M. History, narrative, and life-span developmental knowledge. Hum Dev. 1984;27(1):1-19. 10.1159/000272899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beasley BW, Wright SM, Cofrancesco J, Babbott SF, Thomas PA, Bass EB. Promotion criteria for clinician-educators in the United States and Canada. A survey of promotion committee chairpersons. JAMA. 1997;278(9):723-728. 10.1001/jama.278.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atasoylu AA, Wright SM, Beasley BW, et al. Promotion criteria for clinician-educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):711-716. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.10425.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Woods NN. Evaluation matters: Lessons learned on the evaluation of surgical teaching. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinburgh Irel. 2011;9 Suppl 1:S43-44. 10.1016/j.surge.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wisener KM, Driessen EW, Cuncic C, Hesse CL, Eva KW. Incentives for clinical teachers: on why their complex influences should lead us to proceed with caution. Med Educ. 2020;55(5):614-624. 10.1111/medu.14422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mullan P, Sullivan D, Dielman T. What are raters rating? predicting medical student, pediatric resident, and faculty ratings of clinical teachers. Teach Learn Med. 1993;5(4):221-226. 10.1080/10401339309539627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iwaszkiewicz M, DaRosa D, Risucci D. Efforts to enhance operating room teaching. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(6):436-440. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams BC, Litzelman DK, Babbott SF, Lubitz RM, Hofer TP. Validation of a global measure of faculty’s clinical teaching performance. Acad Med. 2002;77(2):177-180. 10.1097/00001888-200202000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evaluations of clinical faculty: the impact of level of learner and time of year. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(2):87-91. 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cox SS, Swanson MS. Identification of teaching excellence in operating room and clinic settings. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):251-255. 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00787-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Solomon DJ, Speer AJ, Rosebraugh CJ, DiPette DJ. The reliability of medical student ratings of clinical teaching. Eval Health Prof. 1997;20(3):343-352. 10.1177/016327879702000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aron DC, Aucott JN, Papp KK. Teaching awards and reduced departmental longevity: kiss of death or kiss goodbye. What happens to excellent clinical teachers in a research intensive medical school? Med Educ Online. 2000;5(1):4313. 10.3402/meo.v5i.4313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Woolliscroft JO, Harrison R Van, Anderson MB. Faculty views of reimbursement changes and clinical training: a survey of award-winning clinical teachers. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(2):77-86. 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beasley BW, Wright SM. Looking forward to promotion: characteristics of participants in the Prospective Study of Promotion in Academia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):705-710. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20639.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryan MS, Tucker C, DiazGranados D, Chandran L. How are clinician-educators evaluated for educational excellence? A survey of promotion and tenure committee members in the United States. Med Teach. 2019;41(8):927-933. 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1596237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buckley LM, Sanders K, Shih M, Hampton CL. Attitudes of clinical faculty about career progress, career success and recognition, and commitment to academic medicine. Results of a survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2625-2629. 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beasley BW, Simon SD, Wright SM. A time to be promoted. The prospective study of promotion in academia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):123-129. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00297.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomas PA, Diener-West M, Canto MI, Martin DR, Post WS, Streiff MB. Results of an academic promotion and career path survey of faculty at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004;79(3):258-264. 10.1097/00001888-200403000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fleming VM, Schindler N, Martin GJ, DaRosa DA. Separate and equitable promotion tracks for clinician-educators. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1101-1104. 10.1001/jama.294.9.1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lucey C. Promotion for clinician-educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):768-769. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.30701.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Passo MH. The role of the clinician educator in rheumatology. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8(6):469-473. 10.1007/s11926-006-0043-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levinson W, Branch WT, Kroenke K. Clinician-educators in academic medical centers: a two-part challenge. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(1):59-64. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-1-199807010-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levinson W, Rubenstein A. Integrating clinician-educators into Academic Medical Centers: Challenges and potential solutions. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2000;75(9):906-912. 10.1097/00001888-200009000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Glick TH. How best to evaluate clinician-educators and teachers for promotion? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2002;77(5):392-397. 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papp KK, Aucott JN, Aron DC. The problem of retaining clinical teachers in academic medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2001;44(3):402-413. 10.1353/pbm.2001.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD. Academic advancement of clinician educators: why is it so difficult? Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(11):1118-1125. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Greer DS. Faculty rewards for the generalist clinician-teacher. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(1 Suppl):S53-58. 10.1007/BF02600438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greganti M. Where are the clinical role models? Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(2):259-261. 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390140015004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hauer KE, Papadakis MA. Assessment of the contributions of clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):5-6. 10.1007/s11606-009-1186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Levinson W, Rubenstein A. Mission critical--integrating clinician-educators into academic medical centers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):840-843. 10.1056/NEJM199909093411111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reiser SJ. Linking excellence in teaching to departments’ budgets. Acad Med. 1995;70(4):272-275. 10.1097/00001888-199504000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rao RH. Perspectives in medical education-1. Reflections on the state of medical education in Japan. Keio J Med. 2006;55(2):41-51. 10.2302/kjm.55.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rao RH. Perspectives in medical education-2. A blueprint for reform of medical education in Japan. Keio J Med. 2006;55(3):81-95. 10.2302/kjm.55.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rao RH, Rao KH. Perspectives in medical education 9. Revisiting the blueprint for reform of medical education in Japan. Keio J Med. 2010;59(2):52-63. 10.2302/kjm.59.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stadler DJ, Archuleta S, Ibrahim H, Shah NG, Al-Mohammed AA, Cofrancesco J. Gender and international clinician educators. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1106):719-724. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Busari JO, Weggelaar NM, Knottnerus AC, Greidanus P-M, Scherpbier AJJA. How medical residents perceive the quality of supervision provided by attending doctors in the clinical setting. Med Educ. 2005;39(7):696-703. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Van Bruggen L, Ten Cate O, Chen HC. Developing a novel 4-C framework to enhance participation in faculty development. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(4):371-379. 10.1080/10401334.2020.1742124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Olmesdahl PJ. Rewards for teaching excellence: Practice in South African medical schools. Med Educ. 1997;31(1):27-32. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb00039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kumar K, Roberts C, Thistlethwaite J. Entering and navigating academic medicine: academic clinician-educators’ experiences. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):497-503. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Steinert Y, Basi M, Nugus P. How physicians teach in the clinical setting: the embedded roles of teaching and clinical care. Med Teach. 2017;39(12):1238-1244. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1360473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med 2012;87(7):859-869. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]