Abstract

Neural control of the heart involves continuous modulation of cardiac mechanical and electrical activity to meet the organism’s demand for blood flow. The closed-loop control scheme consists of interconnected neural networks with central and peripheral components working cooperatively with each other. These components have evolved to cooperate control of various aspects of cardiac function, which produce measurable “functional” outputs such as heart rate and blood pressure. In this review, we will outline fundamental studies probing the cardiac neural control hierarchy. We will discuss how computational methods can guide improved experimental design and be used to probe how information is processed while closed-loop control is operational. These experimental designs generate large cardio-neural datasets that require sophisticated strategies for signal processing and time series analysis, while presenting the usual large-scale computational challenges surrounding data sharing and reproducibility. These challenges provide unique opportunities for the development and validation of novel techniques to enhance understanding of mechanisms of cardiac pathologies required for clinical implementation.

Keywords: neurocardiology, sudden cardiac death (SCD), closed-loop control, cardiac nervous system, cardiac function

Introduction

Beat-to-beat control of cardiac function requires adaptive adjustments of cardiac electromechanical activity to meet the organism’s blood flow needs. The closed-loop cardiac control network hierarchy consists of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system, the sympathetic and parasympathetic arms of the autonomic nervous system, peripheral ganglia, spinal cord, brain stem, and higher centers in the central nervous system (Ardell et al., 2016; Shivkumar et al., 2016). Contrary to the viewpoint where the peripheral nervous system functions as a conduit for centrally-derived inputs (Yuste, 2015), neural control of cardiac function involves a hierarchy of interconnected neural networks that regionally control indices such as heart rate, blood pressure, or respiration (Ardell et al., 2016; Shivkumar et al., 2016).

Substantial experimental and clinical work has focused on neural contributions to heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure anomalies and associated pathologies including heart failure, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, and hypertension (Sessa et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2020). At a population level, elevated resting heart rate and blood pressure, reduced heart rate variability, and depressed baroreflex sensitivity correlate with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, mortality, arrhythmia, and negative health outcomes (Jones et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2016; Grassi et al., 2019; Fuchs and Whelton, 2020). While these biomarkers remain relevant at a population level, their usefulness to assess risk of adverse outcomes for individual patients is limited due to regionality of the control hierarchy (Huikuri and Stein, 2013; Kember et al., 2013; Ajijola, 2016; Mitrani and Myerburg, 2016; Pan et al., 2020).

The cardiac neural control network may be characterized as a closed-loop control system with the central nervous system as one component (Armour, 2004; Leenen, 2007; Hirooka, 2010; Scherbakov and Doehner, 2018). At the peripheral level of the control hierarchy, afferent and efferent activities arise from locally interconnected feedback loops of ganglia and interconnecting neurons (Ardell et al., 2016; Shivkumar et al., 2016). While the peripheral and central levels are in constant communication, the peripheral level is independently capable of maintaining basic cardiac function (Ardell et al., 1991; Smith et al., 2001a; Smith et al., 2001b). An important consequence is that autonomic control and the heart may become compromised while continuing to maintain function as indicated by measures such as heart rate and blood pressure (Armour, 2004; Kember et al., 2013).

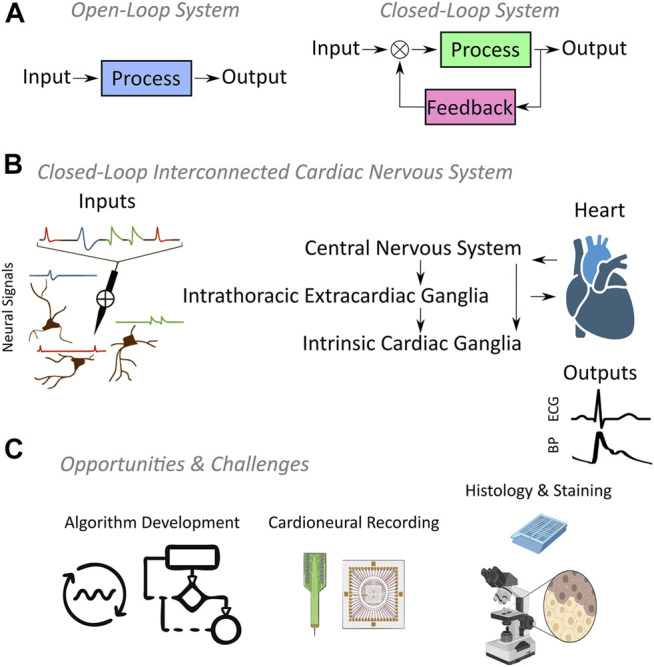

Substantial progress has been made in the description of network components down to the cellular and genomic levels (Moss et al., 2021; Rajendran et al., 2019; Hanna et al., 2021), but the principles and mechanisms governing higher level function and neuro-mechanical linkages are not well defined. This is partly due to the closed-loop nature across levels of the cardiac control hierarchy: it has no simple open-loop analogue to provide a direct linkage between neural activity and functional targets (Figure 1). A useful strategy is to de-link levels within the control hierarchy, and this has been successfully used in experimental designs to gain insight into neural contributions to cardiac function and in clinical interventions as a last resort (Ardell et al., 1991; Smith et al., 2001a; Smith et al., 2001b). A main requirement is that experimental methods must directly measure integration within the cardiac neural control system and the linkage of this system to control targets while in closed-loop operation.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Fundamental difference between open-loop and closed-loop systems is that the system output is regulated by feedback in closed-loop systems, while open-loop systems have no feedback. (B) Cardiac nervous system represents a three-tier closed-loop control hierarchy where each tier exhibits neural inputs resulting in functional outputs such as the electrocardiography (ECG) or blood pressure (BP). (C) Open source algorithm development and novel cardioneural recording technologies supported by histologic studies will propel the field of neurocardiology forward.

In this review, we will outline the fundamental studies focusing on closed-loop information processing within cardiac neural hierarchy. Our emphasis will be less on past achievements and more on identifying trends that are shaping the field. We will discuss how computational methods can help to guide improved experimental designs, quantify the value of small datasets, and become useful for attacking long-standing problems that span multiple scales in space and time. The size and complexity of these next generation cardio-neural datasets require sophisticated strategies for signal processing, time series analysis, and dimensionality reduction, while presenting the usual large-scale computational challenges surrounding data sharing and reproducibility. These challenges provide unique opportunities to further technological development and computational pipelines to drive improved understanding of mechanisms of cardiac pathologies.

Neural Recording Literature in Cardiac Nervous System

The cardiac nervous system offers untapped opportunities to understand mechanisms of cardiac disease and develop novel therapeutic strategies. Manipulation of the cardiac nervous system is a promising approach to mitigate the onset and progression of cardiac pathology. However, its implementation requires an understanding of the neural-mechanical linkages if safe and effective therapeutic strategies are to be developed. In Table 1, a representative selection of the research literature into neuro-mechanical linkages spanning the late 1960s to 2021 is provided. Earlier studies include research into anatomy and function of the stellate ganglion, right atrial ganglionated plexus, spinal cord, and nodose with single-unit recordings (Ja¨nig and Szulczyk, 1980; Armour, 1983; Armour, 1985; Armour, 1986; Gagliardi et al., 1988; Boczek-Funcke et al., 1992; Boczek-Funcke et al., 1993; Armour et al., 1998; Ardell et al., 2009; Salavatian et al., 2019a; Foreman et al., 2015; Foreman and Qin, 2009). With the advent of improved recording methods these approaches have evolved to more recent studies involving multi-unit recordings. Earlier computational methods utilized single neuron recordings and the phase relationship of a neuron’s activity to common cardiac measures were considered. Functional properties of neurons were examined through the neural response to a variety of stimuli such as rhythmicity of the neural firing pattern to functional recordings such as blood pressure and respiration, mechanical touch, electrical stimulation, and pharmacological agents.

TABLE 1.

Research literature probing into cardiac nervous system, listed as regions, recording type (single/multi unit), anesthetic agent, studied species, computational methods used, number of recording electrodes, electrode type, and software used for analysis. The reference numbers correspond to the references in the manuscript.

| Ref # | Year | Region | Recording | Anesthesia | Species | Methods used | # Electrodes | Electrode type | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreman et al. (1975) | 1975 | spinal cord | single unit | halothane, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, conduction velocity | 1 | platinum wire | N/A |

| Ja¨nig and Szulczyk, (1980) | 1980 | lumbar preganglionic neurons | single unit | ketamine hydrochloride, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate, conduction velocity | 1 | platinum wire | N/A |

| Blair et al. (1981) | 1981 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Blair et al. (1982) | 1982 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, conduction velocity | 1 | tungsten, class | N/A |

| Armour, (1983) | 1983 | stellate ganglion | single unit | sodium pentobarbital, alpha chloralose | dog | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1983a) | 1983 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1983b) | 1983 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, conduction velocity | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1984a) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1984b) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, conduction velocity | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons and Foreman, (1984) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate | 1 | carbon tipped glass | N/A |

| Blair et al. (1984b) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey and cat | firing rate | 1 | tungsten or glass | N/A |

| Blair et al. (1984a) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate | 1 | tungsten or glass | N/A |

| Foreman et al. (1984) | 1984 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1985b) | 1985 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Ammons et al. (1985a) | 1985 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Armour, (1985) | 1985 | middle cervical ganglion | single unit | Fentanyl citrate, alpha chloralose | dog | firing rate, action potential discharge pattern, duration, SNR | 1 | tungsten | N/A |

| Armour, (1986) | 1986 | stellate ganglion | single unit | alpha chloralose | dog | firing rate, firing pattern, cardiac/respiration rhythmicity | 1 | tungsten | N/A |

| Brennan et al. (1987) | 1987 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Girardot et al. (1987) | 1987 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Gagliardi et al. (1988) | 1988 | right atrial ganglionated plexus | single unit | Fentanyl citrate, alpha chloralose | dog | firing rate, firing pattern, cardiac/respiration rhythmicity | 1 | tungsten | N/A |

| Bolser et al. (1989) | 1989 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | platinum-iridium | N/A |

| Hobbs et al. (1989) | 1989 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | stainless steel | N/A |

| Chandler et al. (1991) | 1991 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament | N/A |

| Boczek-Funcke et al. (1992) | 1992 | thoracic sympathetic neurons | single unit | ketamine hydrochloride, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate, firing pattern, cardiac/respiration rhythmicity | 1 | platinum wire electrodes | N/A |

| Boczek-Funcke et al. (1993) | 1993 | thoracic preganglionic neurons | single unit | ketamine hydrochloride, alpha chloralose | cat | firing rate, firing pattern, axonal conduction velocity, spontaneous activity, segmental location in spinal cord | 1 | platinum wire electrodes | N/A |

| Zhang et al. (1997) | 1997 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, spikes per stimulus intensity | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Armour et al. (1998) | 1998 | left middle cervical and left stellate ganglion | single unit | thiopental sodium, alpha chloralose | dog | firing pattern, cross correlation (coherence), firing pattern | 1 | tungsten | N/A |

| Chandler et al. (2000) | 2000 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2001) | 2001 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Chandler et al. (2002) | 2002 | spinal cord | single unit | ketamine, alpha chloralose | monkey | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Zhang et al. (2003) | 2003 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2003a) | 2003 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2003b) | 2003 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2003c) | 2003 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2004c) | 2004 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2004a) | 2004 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2004b) | 2004 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2006) | 2006 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2007) | 2007 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2008) | 2008 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Ardell et al. (2009) | 2009 | middle cervical ganglion | single unit | thiopental sodium, alpha chloralose | dog | firing pattern | 1 | tungsten | Spike2 |

| Goodman-Keiser et al. (2010) | 2010 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Qin et al. (2010) | 2010 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Little et al. (2011) | 2011 | spinal cord | single unit | sodium pentobarbital | rat | firing rate, stimulation latency | 1 | carbon-filament glass | N/A |

| Beaumont et al. (2013) | 2013 | right atrial ganglionated plexus | multi unit | isoflurane | dog | template matching, principal component analysis, spike rate, conditional probability | 16 | platinum-iridium | Spike2 |

| Salavatian et al. (2019a) | 2019 | spinal cord | single unit | isoflurone, alpha chloralose | dog | spike sorting feature of software (not specified) | 1 | tungsten | Spike2 |

| Dale et al. (2020) | 2020 | spinal cord | multi unit | inhaled isoflurane, fentanyl, alpha chloralose | pig | firing rate, cross correlation, conditional probability | 64 | platinum-iridium | Spike2 |

| Yoshie et al. (2020) | 2020 | stellate ganglion | multi unit | inhaled isoflurane | pig | firing rate | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Omura et al. (2021) | 2021 | spinal cord | multi unit | inhaled isoflurane, fentanyl, alpha chloralose, bupivacaine | pig | firing rate | 64 | platinum-iridium | iScalDyn |

| Salavatian et al. (2019b) | 2021 | nodose | multi unit | isoflurane, alpha chloralose | pig | firing rate | 16 | platinum-iridium | Spike2, MATLAB |

| Sudarshan et al. (2021) | 2021 | stellate ganglion | multi unit | isoflurane, chloralose | pig | unsupervised spike detection, spike rate | 16 | platinum-iridium | Open source, Python |

Foreman et al. (1975), Foreman et al. (1984) was the first to investigate spinal cord neurons in monkeys using single-unit platinum wire electrodes through laminectomy. These efforts were followed by Blair et al. (1981), Blair et al. (1982), Blair et al. (1984a), Blair et al. (1984b), Ammons et al. (1983a), Ammons et al. (1983b), Ammons et al. (1984a), Ammons and Foreman (1984), Ammons et al. (1984b), Ammons et al. (1985a), Ammons et al. (1985b), Brennan et al. (1987), Girardot et al. (1987), Bolser et al. (1989), Hobbs et al. (1989), and Chandler et al. (1991) in cats and monkeys using tungsten, stainless steel, platinum-iridium, and carbon-filament glass electrodes. The effects of cardiovascular stressors, noxious stressors, vagal afferent stimulation, and pharmacological agents on T1-T5 spinal, spinothalamic, and spinoreticular neurons were studied in separate investigations. These studies laid the groundwork to understand the mechanisms of cardiac pain, roles of neurotransmitters, and multi-organ architecture of spinal neurons (Foreman et al., 2015). Another set of studies focused on C1-C2 spinal neurons (Zhang et al., 1997; Chandler et al., 2000; Qin et al., 2001; Chandler et al., 2002; Qin et al., 2003a; Qin et al., 2003b; Zhang et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2004a; Qin et al., 2004b), characterization of thoracic spinal neurons receiving inputs from the heart and lower airways (Qin et al., 2003c; Qin et al., 2004c; Qin et al., 2006; Qin et al., 2007; Qin et al., 2008), and multi-organ processing of cardiac nociception (Goodman-Keiser et al., 2010; Qin et al., 2010; Little et al., 2011).

Using similar electrode technologies and methods, peripheral investigations were carried out by other groups. Ja¨nig and Szulczyk (1980) investigated the functional properties of lumbar preganglionic sympathetic neurons in cats using single-unit platinum wire electrodes. The functional properties of the neurons were classified according to cardiac rhythmicity, reactions to different stimuli, and axon conduction velocity. Armour (1983) performed a set of experiments to study synaptic transmission in middle cervical and stellate ganglia in dogs after thoracic autonomic ganglia decentralization. Compound action potential shapes were studied based on their response to a number of pharmacological agents and electrical stimulation of an afferent cardiopulmonary nerve. In subsequent studies, extracellular neural activity of middle cervical and stellate ganglia neurons was recorded in dogs (Armour, 1985; Armour, 1986). Action potentials were identified based on pre-determined signal to noise ratios, action potential duration, action potential discharge pattern, and firing rates have been quantified. Neural classifications were performed based on cardiac cycle rhythmicity, respiration, respiration rhythmicity, response to mechanical distortion of the superior vena cava, heart, thoracic aorta, thoracic wall, neck, or foreleg skin, and response to stimulation of sympathetic and/or cardiopulmonary nerves. Gagliardi et al. (1988) similarly studied right atrial ganglionated plexus neural activity in dogs by finding neurons that showed cardiac rhythmicity, respiratory rhythmicity, and responded to mechanical stimuli.

Boczek-Funcke et al. (1992) split nerve bundles into fine filaments upon perineurium incision and utilized 167 single-unit platinum wire electrodes to classify 167 single preganglionic neurons in cats, based on three reflex criteria: cardiac rhythmicity (Group 1 neurons), response to noxious stimulation of the skin (Group 2 neurons), and the coupling of neural activity to central inspiratory drive (phrenic nerve activity, Group 3 neurons). Neurons that showed lack of cardiac rhythmicity but excitability to noxious skin stimuli were labelled Group 4 neurons. A subsequent work by the same group tested whether these four, functionally distinct groups differed in the distribution of their segmental origin within the spinal cord, spontaneous activity, and axonal conduction velocity (Boczek-Funcke et al., 1993). It was reported that neurons showing different reflex patterns differed in segmental location and axonal conduction velocity. A similar stimuli-response approach was undertaken to evaluate the differential selectivity of neurons in middle cervical or stellate ganglia versus intrinsic cardiac ganglia in dogs (Armour et al., 1998). The evaluated interventions were: temporary discontinuation of respiration, alteration of respiratory rate, inferior vena cava occlusion, aortic occlusion, pharmacological agent infusion, epicardial touch, and carotid sinus stimulation. Firing patterns and cross correlation of neural firing across ganglia showed similarity and dissimilarity in reflex patterns to a wide range of stimuli. Lastly, more recent multi-probe recordings of neurons used software (Spike 2, Cambridge Electronic Design) to filter and analyze middle cervical ganglion (Ardell et al., 2009) and dorsal root ganglion (Salavatian et al., 2019a) neural recordings. The totality of evidence led to the conclusion of a thoracic nervous system acting as a distributive processor with redundant cardio-regulatory control mechanisms exerted through multiple nested feedback loops.

With the advent of linear and multi-grid microelectrode arrays, it became feasible to evaluate neural activities within and between neurons. Beaumont et al. reported activity from multiple intrinsic cardiac neurons in the right atrial ganglionated plexus in dogs using a 16-channel linear array (Beaumont et al., 2013). Following an artifact removal process based on right atrial electrogram and stimulator signals, neural activities were compared in different time windows before/after interventions by the computation of the firing rate evolution (Gagliardi et al., 1988). A Skellam distribution (Hyun-Chool Shin et al., 2010) was employed to evaluate the differences in firing rate for each intervention while differential neural to stressors were evaluated via conditional probability and a chi-squared analysis was used to compare the response characteristics of the identified intrinsic cardiac neurons. Nodose and stellate ganglia neural activity were also recorded in a separate study using 16-channel microelectrode arrays (Salavatian et al., 2019b; Yoshie et al., 2020). Spike sorting was performed via principal component analysis and k-means clustering analysis. Afterwards, individual neural activity time series were extracted to study temporal profile, calculate firing rates, and quantify firing patterns with respect to applied cardiac stressor times.

In more recent studies, neural recording technology has used 64-channel neural data distributed over eight “shanks” using penetrating high-density microarrays (Dale et al., 2020; Omura et al., 2021). These studies involved recording from the thoracic spinal cord which serves to integrate cardiac control through intraspinal reflexes. Apparent from Table 1, single-unit spinal cord recordings could pinpoint to a limited set of questions at a single experiment (Foreman et al., 2015), making knowledge transfer between expensive studies challenging. High-density multi-shank recordings are attractive for spinal cord research as these regions include multi-function neural populations and making it difficult to pinpoint neural activity related to cardiac control. Dale et al. (2020) used multi-shank recordings along with a number of stressors to reveal dorsal horn and sympathetic preganglionic cardiac neurons in a pig model. Principal component analysis yielded a total of 1760 identified spinal neurons, and T2 paravertebral ganglion stimulation was used to identify/activate cardiac sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Firing rate and correlation analyses were performed for neuron identification, and percentages of neurons responding to one or more stimuli were reported. Recently, a similar experimental setup and computational methods were used to study the effects of spinal anesthesia (bupivacaine) on spinal network interactions (Omura et al., 2021). Cardiac spinal neurons were identified based on their response to a wide range of interventions and bupivacaine was reported to have cardioprotective effects as it attenuates short-term coordination between local afferent-effect cardiac neurons in spinal cord.

Spike Detection and Spike Sorting

Studies to date have utilized event-based analyses or snapshots of experimental data, which represent only 10% of the experimental data. Analysis of short duration event regions was possible with the use of semi-automated methods with conclusions limited to static analyses. However, development of an understanding of network interactions and space-time dynamics requires the continuous analysis of entire recordings separated into baseline and event epochs. This necessitates an order of magnitude increase in processing and has driven the construction of unsupervised spike detection and classification algorithms of large-scale datasets.

Lewicki (1998) provided the earliest exploration of the techniques and challenges encountered in spike detection and sorting from extracellular microelectrode recordings. Early spike detection was achieved via window discrimination and procedures are detailed for spike sorting based on principal component analysis and component clustering. More recent reviews (Rey et al., 2015; Lefebvre et al., 2016; Hennig et al., 2019) address common challenges and techniques that are moving closer to unsupervised algorithms needed for continuous analysis of large datasets. The algorithms are necessarily tailored to the context of specific applications and measurement equipment that present disparate features.

Our recent application is characterized by ensemble neural activity where individual neurons exhibit firing rates on the order of 1 Hz without bursting (Sudarshan et al., 2021). Neural activity detected farther from the multi-channel probe represents the superposition of attenuated activity. The superposition and attenuation eventually produce recorded signals that where individual action potentials cannot be recognized, and this is termed the “noise floor.” A primary goal in analyzing multi-channel recordings is to assess network function and this is made possible by working close to the noise floor and increasing the number of recorded spikes through several orders of magnitude. We use an unsupervised approach where spikes are detected at iterated thresholds based on a competition between the number of positive and negative spikes detected at each iteration (Sudarshan et al., 2021). Regions containing spikes detected within an iteration are masked and rendered undetectable at later iterations. This approach allowed for detailed assessment of specificity over space and time of stellate ganglion population activity to specific cycles in cardiac and pulmonary dynamics during an experiment.

Following the detection of spikes, a typical spike sorting procedure involves extracting features from detected spikes and assigning them to unique clusters where each cluster would ideally represent activity from a single neuron. Rey et al. (2015) and Lefebvre et al. (2016) outlined procedures such as projection on basis functions, principal component analysis and wavelet analysis that are commonly used for feature extraction prior to clustering from detected spikes. Various clustering algorithms such as Gaussian mixtures, k-means, and density-based clustering were reviewed along with a template matching procedure for extracting activity from single neurons from the clusters. The major challenge in using these clustering methods to isolate the activity of specific neurons within a population remains the lack of an independent means to assess cluster validity. This problem is reviewed in (Foreman et al., 1975) with respect to validating spike sorting clusters with and without human-based or synthetic ground truth validations of sorted spikes. It is also explored in (Magland et al., 2020) where automated spike sorting pipelines are built for the low-dimensional spike sorting problem and compared to other approaches.

Study Design and Data Analysis Considerations

In this section, we address experimental issues that should be considered when designing and analyzing neural recording studies to probe the cardiac nervous system and a hierarchical closed-loop controller. Table 1 lists these details for cardiac literature discussed previously.

Single-Unit vs Multi-Unit Recordings

The range of electrode technologies has also greatly diversified the type of collected neural signals. Single-unit tungsten or platinum wire single-unit electrodes have dominated the field until 2000s (Ja¨nig and Szulczyk, 1980; Armour, 1985; Boczek-Funcke et al., 1992; Armour et al., 1998). In recent years, multi-unit or multi-channel recordings have appeared in studies due to the availability of recording technologies (Beaumont et al., 2013; Dale et al., 2020; Sudarshan et al., 2021). Both single- and multi-unit electrodes have strengths and weaknesses depending on the experimental goals.

For single-unit recordings, the target neurons must be isolated and recording electrodes should be fine-tipped with low-impedance conductors for high quality recording. Single-unit recordings may record several isolated neurons with wire electrodes in separate nerve bundles (Boczek-Funcke et al., 1992). While large electrode arrays increase the amount of collected information per unit time, they may not provide sufficient isolation. The multi-unit signals involve recording of closest neural populations, rather than the closest single neuron. In the recent neuroscience literature, a shift in the experimental focus to interactions of neural populations and their ensemble behaviors (Yuste, 2015; Zamani Esfahlani et al., 2020) has led to the nearly exclusive use of multi-unit recordings.

Study reproducibility requires reporting details of electrode design, statistical analyses should consider the independence of data and the addition of electrode/neuron identity as covariates. Data collected from a multi-unit electrode array have more stringent methodological constraints compared to single-unit data analysis. Multi-unit recordings cannot be classified as independent if unit isolation was unassessed whereas multiple single-unit recordings may be considered independent datasets assuming isolated neurons are being recorded.

Reliance on Animal Models and Anesthesia

Open heart surgeries conducted in cardiac nervous system research studies require the use of anesthetic agents, a list of agents have been listed in Table 1. In large animal models such as dogs and pigs, isoflurane inhalation followed by alpha-chloralose have been dominantly employed. Ideally, the agent should not restrict the scientific interpretation while providing stable experimental conditions showing an absence of depression of cardiovascular or autonomic activity which is a disadvantage in cardiac neural recordings.

The use of open chest preparations along with the application of anesthesia in terminal animal experiments inevitably biases both study results, interpretations, and any potential extension to humans. Yet, when experiments are tightly controlled, chronic animal model studies have been proven informative to study the nature of interactions among neural populations and their evolution from normal to pathological states. Collection of neural data from human cardiac nervous system is a more difficult and constrained task as the experiment with humans cannot be regarded as terminal. Translational failure may be explained by methodological flaws and inadequate data in animal studies. To avoid translational failure, publications should clearly indicate the study details. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses play substantial role in the selection of the most promising interpretations that could be extended to humans.

Sample Sizes and Statistical Power

There has been considerable concern surrounding reproducibility of small biomedical research datasets and contamination of literature with false positive reports due to publication pressure and lack of venues that encourage publication of negative results (Ioannidis, 2005; Button et al., 2013). This might be partly due to lack of planning in experimental design and reliance on the analysis of smaller studies compared to large clinical trials that involve dedicated personnel and a more thorough analysis. It is essential for investigators to describe number of animals, specifics of neural recording channels, neural type where relevant, along with power analyses for statistical significance and effect size for practical relevance. Effect size, a standardized measure that quantifies the size of difference or association between two groups, should be provided in addition to statistical significances to facilitate meta-analysis and reproducibility (Sullivan and Feinn, 2012).

Data and Code Sharing

Combined resources surpass the capacity of individual research laboratories or institutional efforts (Ascoli et al., 2017). To date, some effort has been made to enable data reusability such as NeuroMorpho.Org (Ascoli et al., 2007), Neurodata Without Borders (Teeters et al., 2015), and PhysioNet (Goldberger et al., 2000). An instrumental effort within the context of cardiac nervous system has been the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund’s Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) platform that encourages raw data sharing with proper labeling and a listing of computational methods/models (Osanlouy et al., 2021). In addition, computational techniques such as signal processing, machine learning, statistical analyses are central in data analysis and interpretation of results. Methods sections of research papers outline essential processing flows and mathematic/statistical information, but the complete linkage between raw data and the published results requires access to small scripts for statistical manipulations and to much larger routines used to process the raw data to a useable form. Public access to research codes, complete data pipelines used to construct all results is necessary for reproducibility, transparency of data/analysis assumptions, and the further development of software (Barnes, 2010; Ince et al., 2012).

Concluding Remarks

We are in an exciting period of study of the cardiac nervous system with the availability of high-density recording technologies and advances in open-source computational pipelines and data-analytic methods suitable for closed-loop systems. The neuroscience literature offers a wide range of novel analytical tools and interventions mostly related to open-loop brain recording studies. Such experimental designs have separated inputs and outputs (Yuste, 2015), which do not extend to cardiac studies where heart in open-loop mode would have no afferent feedback and is not experimentally realizable or meaningful. The presence of afferent signals in closed-loop mode implies that efferent cardiac inputs are returned via the afferent pathway from the heart and further affects the efferent input to the heart. In this sense, inputs and outputs are unseparated and this has necessitated the development of metrics suitable for the analysis of the dynamical state of closed-loop networked control.

The requirement to analyze continuous recordings instead of focusing on stimulus-evoked regions is driving the development of unsupervised algorithms for spike detection and classification due to a large increase in data. These analyses are leading to the discovery a highly nuanced interpretation of the neural network status in normal versus diseased states that is unavailable from event-based analyses.

Moreover, reproducibility requirements are more difficult to meet for multi-unit experimental designs where changes in probe placement, animal’s autonomic status, surgical preparation, experimenter abilities, and genetic differences will lead to greater variability in experimental results. Designing elegant investigations that meet these reproducibility constraints, data, and method sharing supported by histological studies giving improved anatomical information are all required to further develop neurocardiology and improve clinical interventions.

Author Contributions

NG, GK, JA, and OA conceptualized and planned the manuscript. NG, ST, and DL organized the literature. NG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NG, KB, and GK wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Office of The Director DP2 OD024323-01 (OA), and U01EB025138 (GK), and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute HL159001 (OA). NG was funded by the NSF Engineering Fellows Postdoctoral Fellowship Award ID #2127509.

Conflict of Interest

University of California, Los Angeles has patents relating to cardiac neural diagnostics and therapeutics. OA is a co-founder of NeuCures, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ajijola O. A. (2016). Sudden Cardiac Death: We Are Not There yet. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 26 (1), 34–35. 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Blair R. W., Foreman R. D. (1984). Raphe Magnus Inhibition of Primate T1-T4 Spinothalamic Cells with Cardiopulmonary Visceral Input. PAIN 20 (3), 247–260. 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Blair R. W., Foreman R. D. (1984). Greater Splanchnic Excitation of Primate T1-T5 Spinothalamic Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 51 (3), 592–603. 10.1152/jn.1984.51.3.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Blair R. W., Foreman R. D. (1983). Vagal Afferent Inhibition of Primate Thoracic Spinothalamic Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 50 (4), 926–940. 10.1152/jn.1983.50.4.926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Blair R. W., Foreman R. D. (1983). Vagal Afferent Inhibition of Spinothalamic Cell Responses to Sympathetic Afferents and Bradykinin in the Monkey. Circ. Res. 53 (5), 603–612. 10.1161/01.RES.53.5.603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Foreman R. D. (1984). Cardiovascular and T2-T4 Dorsal Horn Cell Responses to Gallbladder Distention in the Cat. Brain Res. 321 (2), 267–277. 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90179-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Girardot M. N., Foreman R. D. (1985). Effects of Intracardiac Bradykinin on T2-T5 Medial Spinothalamic Cells. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 249 (2), R147–R152. 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.2.R147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons W. S., Girardot M. N., Foreman R. D. (1985). T2-T5 Spinothalamic Neurons Projecting to Medial Thalamus with Viscerosomatic Input. J. Neurophysiol. 54 (1), 73–89. 10.1152/jn.1985.54.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardell J. L., Andresen M. C., Armour J. A., Billman G. E., Chen P.-S., Foreman R. D., et al. (2016). Translational Neurocardiology: Preclinical Models and Cardioneural Integrative Aspects. J. Physiol. 594 (14), 3877–3909. 10.1113/JP271869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardell J. L., Butler C. K., Smith F. M., Hopkins D. A., Armour J. A. (1991). Activity of In Vivo Atrial and Ventricular Neurons in Chronically Decentralized Canine Hearts. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 260 (3), H713–H721. 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.3.H713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardell J. L., Cardinal R., Vermeulen M., Armour J. A. (2009). Dorsal Spinal Cord Stimulation Obtunds the Capacity of Intrathoracic Extracardiac Neurons to Transduce Myocardial Ischemia. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 297 (2), R470–R477. 10.1152/ajpregu.90821.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour J. A. (1985). Activity of In Situ Middle Cervical Ganglion Neurons in Dogs, Using Extracellular Recording Techniques. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 63 (6), 704–716. 10.1139/y85-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour J. A. (1986). Activity of In Situ Stellate Ganglion Neurons of Dogs Recorded Extracellularly. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (2), 101–111. 10.1139/y86-016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour J. A. (2004). Cardiac Neuronal Hierarchy in Health and Disease. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287 (2), R262–R271. 10.1152/ajpregu.00183.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour J. A., Collier K., Kember G., Ardell J. L. (1998). Differential Selectivity of Cardiac Neurons in Separate Intrathoracic Autonomic Ganglia. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 274 (4), R939–R949. 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour J. A. (1983). Synaptic Transmission in the Chronically Decentralized Middle Cervical and Stellate Ganglia of the Dog. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 61 (10), 1149–1155. 10.1139/y83-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli G. A., Donohue D. E., Halavi M. (2007). NeuroMorpho.Org: A Central Resource for Neuronal Morphologies. J. Neurosci. 27 (35), 9247–9251. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2055-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli G. A., Maraver P., Nanda S., Polavaram S., Armañanzas R. (2017). Win-win Data Sharing in Neuroscience. Nat. Methods 14 (2), 112–116. 10.1038/nmeth.4152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. (2010). Publish Your Computer Code: it Is Good Enough. Nature 467 (7317), 753. 10.1038/467753a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont E., Salavatian S., Southerland E. M., Vinet A., Jacquemet V., Armour J. A., et al. (2013). Network Interactions within the Canine Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System: Implications for Reflex Control of Regional Cardiac Function. J. Physiol. 591 (18), 4515–4533. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. W., Ammons W. S., Foreman R. D. (1984). Responses of Thoracic Spinothalamic and Spinoreticular Cells to Coronary Artery Occlusion. J. Neurophysiol. 51 (4), 636–648. 10.1152/jn.1984.51.4.636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. W., Weber R. N., Foreman R. D. (1981). Characteristics of Primate Spinothalamic Tract Neurons Receiving Viscerosomatic Convergent Inputs in T3-T5 Segments. J. Neurophysiol. 46 (4), 797–811. 10.1152/jn.1981.46.4.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. W., Weber R. N., Foreman R. D. (1984). Responses of Thoracic Spinoreticular and Spinothalamic Cells to Intracardiac Bradykinin. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 246 (4), H500–H507. 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.4.H500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. W., Weber R. N., Foreman R. D. (1982). Responses of Thoracic Spinothalamic Neurons to Intracardiac Injection of Bradykinin in the Monkey. Circ. Res. 51 (1), 83–94. 10.1161/01.RES.51.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczek-Funcke A., Dembowsky K., Häbler H.-J., Jänig W., Michaelis M. (1993). Spontaneous Activity, Conduction Velocity and Segmental Origin of Different Classes of Thoracic Preganglionic Neurons Projecting into the Cat Cervical Sympathetic Trunk. J. Auton. Nervous Syst. 43 (3), 189–200. 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90325-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczek-Funcke A., Dembowsky K., Häbler H. J., Jänig W., McAllen R. M., Michaelis M. (1992). Classification of Preganglionic Neurones Projecting into the Cat Cervical Sympathetic Trunk. J. Physiol. 453, 319–339. 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser D. C., Chandler M. J., Garrison D. W., Foreman R. D. (1989). Effects of Intracardiac Bradykinin and Capsaicin on Spinal and Spinoreticular Neurons. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 257 (5), H1543–H1550. 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan T. J., Oh U. T., Girardot M.-N., Steve Ammons W., Foreman R. D. (1987). Inhibition of Cardiopulmonary Input to Thoracic Spinothalamic Tract Cells by Stimulation of the Subcoeruleus-Parabrachial Region in the Primate. J. Auton. Nervous Syst. 18 (1), 61–72. 10.1016/0165-1838(87)90135-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button K. S., Ioannidis J. P. A., Mokrysz C., Nosek B. A., Flint J., Robinson E. S. J., et al. (2013). Power Failure: Why Small Sample Size Undermines the Reliability of Neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 (5), 365–376. 10.1038/nrn3475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. J., Hobbs S. F., Bolser D. C., Foreman R. D. (1991). Effects of Vagal Afferent Stimulation on Cervical Spinothalamic Tract Neurons in Monkeys. PAIN 44 (1), 81–87. 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90152-n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. J., Zhang J., Qin C., Foreman R. D. (2002). Spinal Inhibitory Effects of Cardiopulmonary Afferent Inputs in Monkeys: Neuronal Processing in High Cervical Segments. J. Neurophysiol. 87 (3), 1290–1302. 10.1152/jn.00079.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. J., Zhang J., Qin C., Yuan Y., Foreman R. D. (2000). Intrapericardiac Injections of Algogenic Chemicals Excite Primate C1-C2 Spinothalamic Tract Neurons. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279 (2), R560–R568. 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.2.R560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale E. A., Kipke J., Kubo Y., Sunshine M. D., Castro P. A., Ardell J. L., et al. (2020). Spinal Cord Neural Network Interactions: Implications for Sympathetic Control of the Porcine Heart. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 318 (4), H830–H839. 10.1152/ajpheart.00635.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman R. D., Applebaum A. E., Beall J. E., Trevino D. L., Willis W. D. (1975). Responses of Primate Spinothalamic Tract Neurons to Electrical Stimulation of Hindlimb Peripheral Nerves. J. Neurophysiol. 38 (1), 132–145. 10.1152/jn.1975.38.1.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman R. D., Blair R. W., Neal Weber R. (1984). Viscerosomatic Convergence onto T2-T4 Spinoreticular, Spinoreticular-Spinothalamic, and Spinothalamic Tract Neurons in the Cat. Exp. Neurol. 85 (3), 597–619. 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90034-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman R. D., Garrett K. M., Blair R. W. (2015). Mechanisms of Cardiac Pain. Compr. Physiol. 61, 929–960. 10.1002/cphy.c14003210.1002/cphy.c140032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman R. D., Qin C. (2009). Neuromodulation of Cardiac Pain and Cerebral Vasculature: Neural Mechanisms. Ccjm 76 (4), S75–S79. 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs F. D., Whelton P. K. (2020). High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 75 (2), 285–292. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi M., Randall W. C., Bieger D., Wurster R. D., Hopkins D. A., Armour J. A. (1988). Activity of In Vivo Canine Cardiac Plexus Neurons. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 255 (4), H789–H800. 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.4.H789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardot M.-N., Brennan T. J., Martindale M. E., Foreman R. D. (1987). Effects of Stimulating the Subcoeruleus-Parabrachial Region on the Non-noxious and Noxious Responses of T1-T5 Spinothalamic Tract Neurons in the Primate. Brain Res. 409 (1), 19–30. 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90737-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger A. L., Amaral L. A. N., Glass L., Hausdorff J. M., Ivanov P. C., Mark R. G., et al. (2000). PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet. Circulation 101 (23), e215–e220. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Keiser M. D., Qin C., Thompson A. M., Foreman R. D. (2010). Upper Thoracic Postsynaptic Dorsal Column Neurons Conduct Cardiac Mechanoreceptive Information, but Not Cardiac Chemical Nociception in Rats. Brain Res. 1366, 71–84. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G., D'Arrigo G., Pisano A., Bolignano D., Mallamaci F., Dell'Oro R., et al. (2019). Sympathetic Neural Overdrive in Congestive Heart Failure and its Correlates: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. J. Hypertens. 37 (9), 1746–1756. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna P., Dacey M. J., Brennan J., Moss A., Robbins S., Achanta S., et al. (2021). Innervation and Neuronal Control of the Mammalian Sinoatrial Node a Comprehensive Atlas. Circ. Res. 128 (9), 1279–1296. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig M. H., Hurwitz C., Sorbaro M. (2019). “Scaling Spike Detection and Sorting for Next-Generation Electrophysiology,” in In Vitro Neuronal Networks: From Culturing Methods to Neuro-Technological Applications. Editors Chiappalone M., Pasquale V., Frega M. (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ), 171–184. 10.1007/978-3-030-11135-9_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y. (2010). Brain Perivascular Macrophages and Central Sympathetic Activation after Myocardial Infarction. Hypertension 55 (3), 610–611. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs S. F., Oh U. T., Chandler M. J., Foreman R. D. (1989). Cardiac and Abdominal Vagal Afferent Inhibition of Primate T9-S1 Spinothalamic Cells. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 257 (4), R889–R895. 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.4.R889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huikuri H. V., Stein P. K. (2013). Heart Rate Variability in Risk Stratification of Cardiac Patients. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 56 (2), 153–159. 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun-Chool Shin H., Aggarwal V., Acharya S., Schieber M. H., Thakor N. V. (2010). Neural Decoding of Finger Movements Using Skellam-Based Maximum-Likelihood Decoding. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57 (3), 754–760. 10.1109/TBME.2009.2020791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince D. C., Hatton L., Graham-Cumming J. (2012). The Case for Open Computer Programs. Nature 482 (7386), 485–488. 10.1038/nature10836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J. P. A. (2005). Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. Plos Med. 2 (8), e124. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja¨nig W., Szulczyk P. (1980). Functional Properties of Lumbar Preganglionic Neurones. Brain Res. 186 (1), 115–131. 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90259-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. M., Quinn M. S., Minisi A. J. (2008). Reflex Control of Sympathetic Outflow and Depressed Baroreflex Sensitivity Following Myocardial Infarction. Auton. Neurosci. 141 (1), 46–53. 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kember G., Armour J. A., Zamir M. (2013). Neural Control Hierarchy of the Heart Has Not Evolved to deal with Myocardial Ischemia. Physiol. Genomics 45 (15), 638–644. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00027.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenen F. H. H. (2007). Brain Mechanisms Contributing to Sympathetic Hyperactivity and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 101 (3), 221–223. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre B., Yger P., Marre O. (2016). Recent Progress in Multi-Electrode Spike Sorting Methods. J. Physiology-Paris 110 (4), 327–335. Part A. 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki M. S. (1998). A Review of Methods for Spike Sorting: the Detection and Classification of Neural Action Potentials. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 9 (4), R53–R78. 10.1088/0954-898x_9_4_001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J. M., Qin C., Farber J. P., Foreman R. D. (2011). Spinal Cord Processing of Cardiac Nociception: Are There Sex Differences between Male and Proestrous Female Rats? Brain Res. 1413, 24–31. 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magland J., Jun J. J., Lovero E., Morley A. J., Hurwitz C. L., Buccino A. P., et al. (2020). SpikeForest, Reproducible Web-Facing Ground-Truth Validation of Automated Neural Spike Sorters. eLife 9, e55167. 10.7554/eLife.55167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrani R. D., Myerburg R. J. (2016). Ten Advances Defining Sudden Cardiac Death. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 26 (1), 23–33. 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss A., Robbins S., Achanta S., Kuttippurathu L., Turick S., Nieves S., et al. (2021). A Single Cell Transcriptomics Map of Paracrine Networks in the Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System. iScience 24 (7), 102713. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura Y., Kipke J. P., Salavatian S., Afyouni A. S., Wooten C., Herkenham R. F., et al. (2021). Spinal Anesthesia Reduces Myocardial Ischemia-Triggered Ventricular Arrhythmias by Suppressing Spinal Cord Neuronal Network Interactions in Pigs. Anesthesiology 134 (3), 405–420. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanlouy M., Bandrowski A., de Bono B., Brooks D., Cassarà A. M., Christie R., et al. (2021). The SPARC DRC: Building a Resource for the Autonomic Nervous System Community. Front. Physiol. 12, 929. 10.3389/fphys.2021.693735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Hibino M., Kobeissi E., Aune D. (2020). Blood Pressure, Hypertension and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35 (5), 443–454. 10.1007/s10654-019-00593-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Chandler M. J., Foreman R. D. (2004). Esophagocardiac Convergence onto Thoracic Spinal Neurons: Comparison of Cervical and Thoracic Esophagus. Brain Res. 1008 (2), 193–197. 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Chandler M. J., Jou C. J., Foreman R. D. (2004). Responses and Afferent Pathways of C1-C2 Spinal Neurons to Cervical and Thoracic Esophageal Stimulation in Rats. J. Neurophysiol. 91 (5), 2227–2235. 10.1152/jn.00971.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Chandler M. J., Miller K. E., Foreman R. D. (2003). Chemical Activation of Cardiac Receptors Affects Activity of Superficial and Deeper T3-T4 Spinal Neurons in Rats. Brain Res. 959 (1), 77–85. 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03728-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Chandler M. J., Miller K. E., Foreman R. D. (2001). Responses and Afferent Pathways of Superficial and Deeper C1-C2 Spinal Cells to Intrapericardial Algogenic Chemicals in Rats. J. Neurophysiol. 85 (4), 1522–1532. 10.1152/jn.2001.85.4.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Farber J. P., Foreman R. D. (2008). Intraesophageal Chemicals Enhance Responsiveness of Upper Thoracic Spinal Neurons to Mechanical Stimulation of Esophagus in Rats. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 294 (3), G708–G716. 10.1152/ajpgi.00477.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Farber J. P., Miller K. E., Foreman R. D. (2006). Responses of Thoracic Spinal Neurons to Activation and Desensitization of Cardiac TRPV1-Containing Afferents in Rats. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291 (6), R1700–R1707. 10.1152/ajpregu.00231.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Foreman R. D., Farber J. P. (2007). Characterization of Thoracic Spinal Neurons with Noxious Convergent Inputs from Heart and Lower Airways in Rats. Brain Res. 1141, 84–91. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Greenwood-Van Meerveld B., Foreman R. D. (2003). Spinal Neuronal Responses to Urinary Bladder Stimulation in Rats with Corticosterone or Aldosterone onto the Amygdala. J. Neurophysiol. 90 (4), 2180–2189. 10.1152/jn.00298.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Greenwood-Van Meerveld B., Myers D. A., Foreman R. D. (2003). Corticosterone Acts Directly at the Amygdala to Alter Spinal Neuronal Activity in Response to Colorectal Distension. J. Neurophysiol. 89 (3), 1343–1352. 10.1152/jn.00834.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Kranenburg A., Foreman R. D. (2004). Descending Modulation of Thoracic Visceroreceptive Transmission by C1-C2 Spinal Neurons. Auton. Neurosci. 114 (1), 11–16. 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Malykhina A. P., Thompson A. M., Farber J. P., Foreman R. D. (2010). Cross-organ Sensitization of Thoracic Spinal Neurons Receiving Noxious Cardiac Input in Rats with Gastroesophageal Reflux. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 298 (6), G934–G942. 10.1152/ajpgi.00312.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran P. S., Challis R. C., Fowlkes C. C., Hanna P., Tompkins J. D., Jordan M. C., et al. (2019). Identification of Peripheral Neural Circuits that Regulate Heart Rate Using Optogenetic and Viral Vector Strategies. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 1944. 10.1038/s41467-019-09770-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey H. G., Pedreira C., Quian Quiroga R. (2015). Past, Present and Future of Spike Sorting Techniques. Brain Res. Bull. 119, 106–117. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salavatian S., Ardell S. M., Hammer M., Gibbons D., Armour J. A., Ardell J. L. (2019). Thoracic Spinal Cord Neuromodulation Obtunds Dorsal Root Ganglion Afferent Neuronal Transduction of the Ischemic Ventricle. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 317 (5), H1134–H1141. 10.1152/ajpheart.00257.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salavatian S., Yamaguchi N., Hoang J., Lin N., Patel S., Ardell J. L., et al. (2019). Premature Ventricular Contractions Activate Vagal Afferents and Alter Autonomic Tone: Implications for Premature Ventricular Contraction-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 317 (3), H607–H616. 10.1152/ajpheart.00286.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherbakov N., Doehner W. (2018). Heart-brain Interactions in Heart Failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 4 (2), 87–91. 10.15420/cfr.2018.14.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa F., Anna V., Messina G., Cibelli G., Monda V., Marsala G., et al. (2018). Heart Rate Variability as Predictive Factor for Sudden Cardiac Death. Aging 10 (2), 166–177. 10.18632/aging.101386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivkumar K., Ajijola O. A., Anand I., Armour J. A., Chen P.-S., Esler M., et al. (2016). Clinical Neurocardiology Defining the Value of Neuroscience-Based Cardiovascular Therapeutics. J. Physiol. 594 (14), 3911–3954. 10.1113/JP271870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F. M., McGuirt A. S., Hoover D. B., Armour J. A., Ardell J. L. (2001). Chronic Decentralization of the Heart Differentially Remodels Canine Intrinsic Cardiac Neuron Muscarinic Receptors. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 281 (5), H1919–H1930. 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F. M., McGuirt A. S., Leger J., Armour J. A., Ardell J. L. (2001). Effects of Chronic Cardiac Decentralization on Functional Properties of Canine Intracardiac Neurons In Vitro . Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiol. 281 (5), R1474–R1482. 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarshan K. B., Hori Y., Swid M. A., Karavos A. C., Wooten C., Armour J. A., et al. (2021). A Novel Metric Linking Stellate Ganglion Neuronal Population Dynamics to Cardiopulmonary Physiology. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 321, H369–H381. 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G. M., Feinn R. (2012). Using Effect Size-Or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad Med. Educ. 4 (3), 279–282. 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters J. L., Godfrey K., Young R., Dang C., Friedsam C., Wark B., et al. (2015). Neurodata without Borders: Creating a Common Data Format for Neurophysiology. Neuron 88 (4), 629–634. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshie K., Rajendran P. S., Massoud L., Mistry J., Swid M. A., Wu X., et al. (2020). Cardiac TRPV1 Afferent Signaling Promotes Arrhythmogenic Ventricular Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction. JCI Insight 5 (3), 02–132020. 10.1172/jci.insight.124477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R. (2015). From the Neuron Doctrine to Neural Networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16 (8), 487–497. 10.1038/nrn3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamani Esfahlani F., Jo Y., Faskowitz J., Byrge L., Kennedy D. P., Sporns O., et al. (2020). High-amplitude Cofluctuations in Cortical Activity Drive Functional Connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (45), 28393–28401. 10.1073/pnas.2005531117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Shen X., Qi X. (2016). Resting Heart Rate and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in the General Population: a Meta-Analysis. Cmaj 188 (3), E53–E63. 10.1503/cmaj.150535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chandler M. J., Foreman R. D. (2003). Cardiopulmonary Sympathetic and Vagal Afferents Excite C1-C2 Propriospinal Cells in Rats. Brain Res. 969 (1), 53–58. 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02277-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chandler M. J., Miller K. E., Foreman R. D. (1997). Cardiopulmonary Sympathetic Afferent Input Does Not Require Dorsal Column Pathways to Excite C1-C3 Spinal Cells in Rats. Brain Res. 771 (1), 25–30. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00607-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]