Abstract

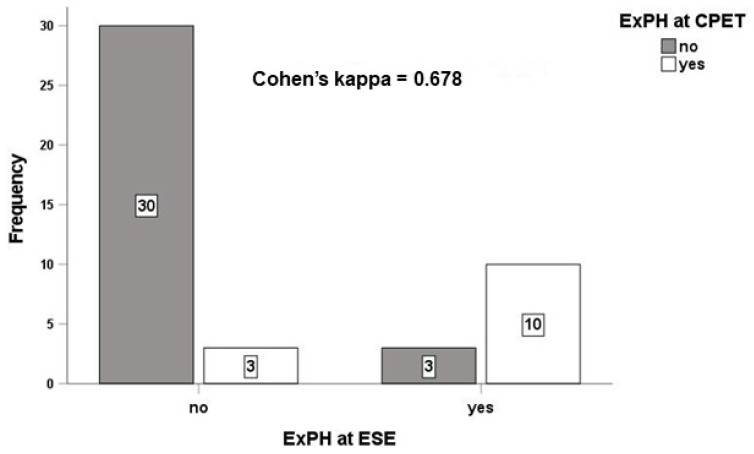

Background and Aim: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) at rest can be preceded by the onset of exercise-induced PH (ExPH). We investigated its association with the cardiovascular (CV) risk score in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Methods: In 46 consecutive patients with HIV with low (n = 43) or intermediate (n = 3) probability of resting PH, we evaluated the CV risk score based on prognostic determinants of CV risk. Diagnosis of ExPH was made by cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) and exercise stress echocardiogram (ESE). Results: Twenty-eight % (n = 13) of the enrolled patients had ExPH at both CPET and ESE, with good agreement between the two methods (Cohen’s kappa = 0.678). ExPH correlated directly with a higher CV score (p < 0.001). Patients with a higher CV score also had lower CD4+ T-cell counts (p = 0.001), a faster progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (p < 0.001), a poor immunological response to antiretroviral therapy (p = 0.035), higher pulmonary vascular resistance (p = 0.003) and a higher right atrial area (p = 0.006). Conclusions: Isolated ExPH is associated with a high CV risk score in patients with HIV. Assessment of ExPH may better stratify CV risk in patients with HIV.

Keywords: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cardiovascular risk, exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension, exercise stress echocardiography, exercise cardiopulmonary test

1. Introduction

HIV infection represents a potential risk factor for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [1]. PAH is the main cause of mortality in patients with HIV [2]. Reduced pulmonary vascular reserve may be silent at rest, while it occurs with PH during exercise. The onset of exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension (ExPH), therefore, represents the first clinical sign of pulmonary vascular disease that can progress to PAH. Similar to other clinical PAH groups, a significant number of patients with HIV may have ExPH [3,4,5,6,7]. However, the prognostic value of ExPH in patients with HIV is poorly studied and Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend further investigation [8].

Isolated ExPH is also associated with cardiovascular (CV) events in patients with valvular or ischemic heart disease [9,10], while it is associated with clinical worsening in patients with scleroderma [11].

We have recently shown that the onset of ExPH, diagnosed by exercise stress echocardiogram (ESE), is associated with poor control of HIV infection and ExPH is associated with impaired functional capacity, as measured by the World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC), suggesting that disease progression in the lung leads to a reduction in the vasodilatory reserve of pulmonary circulation and, consequently, PH triggered by exercise [12]. How ExPH correlates with CV risk in patients with HIV has never been previously studied. Here, we hypothesized that an increased CV risk in patients with HIV can be determined early through the work-out for ExPH by ESE and cardiopulmonary stress testing (CPET).

2. Methods

Study Design and Data Collection. We conducted a prospective, observational, cohort study of patients with HIV recruited from the Infectious Disease Clinic at Pisa University Hospital. The study complies with the Helsinki Declaration, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to any diagnostic test. Local investigators had full access to patient data and medical records.

All of the enrolled patients underwent evaluation of PH probability at rest by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) [9,12], followed by ExPH assessment by transthoracic exercise stress echocardiogram (ESE) and cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), as detailed in the Supplementary Materials. Patients included had either a “low” PH probability at rest (n = 43) or an “intermediate” PH probability at rest (n = 3). We excluded patients with a “high” PH probability (n = 8). Patients were then classified as either with or without ExPH at ESE or CPET. We evaluated the CV risk score by assessing the presence/absence of the prognostic determinants of cardiovascular (CV) risk, according to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) Guidelines [1] and, as detailed in the Supplementary Materials. We assigned a severity score of 1–3 to each prognostic determinant and derived an overall CV risk score [11]. We then evaluated the association of a higher CV score with the presence/absence of ExPH, and with several echocardiographic parameters [12] and immuno-virological parameters.

Mono and 2D Transthoracic Echocardiography was performed using a Philips iE33 echocardiograph (Philips iE33 xMATRIX echocardiography system, Andover, MA) [13]. The images were recorded in at least three cardiac cycles. Right atrial pressure (RAP) was assessed by evaluating the inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and collapsibility during inspirium [13]. Systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (PAPs) was calculated by adding RAP to the maximum systolic pressure gradient from tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV). Left atrial volume index (LAVi) was calculated by Simpson’s algorithm in apical four-chamber and two-chamber view [13]. Mitral, aortic and tricuspidal regurgitations were assessed by measuring the vena contracta at apical four-chamber view.

Stress echocardiography. All patients underwent a semi-supine ESE performed with a 2.5-MHz duplex transducer and a Philips iE33 echocardiograph (Philips iE33 xMATRIX echocardiography system, Andover, MA, USA) on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Ergoline, model 900 EL, Germany), according to the European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) Guidelines [13,14,15,16,17,18]. A detailed protocol of the echocardiographic procedures is reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test. We performed the CPET on an electronically-braked cycle ergometer, using Vmax 6200 Spectra Series software (SensorMedics, Hochberg, Germany), according to a graded, cycling workload increase protocol. The test was interrupted when one of the following symptoms or signs occurred: angina; electrocardiographic signs of myocardial ischemia or injury; an excessive blood pressure increase (systolic blood pressure ≥ 240 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 120 mmHg); dyspnea or maximal predicted heart rate. A detailed protocol is reported in the Supplementary Materials [19,20,21].

Statistical Analyses

Categorical data were expressed by absolute and relative frequency, and continuous data by mean and standard deviation (SD). The Chi square test and the Student’s t-test for independent (two-tailed) samples were used to compare categorial and continuous variables with ExPH, respectively. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to compare the CV score with continuous factors, while the Student’s t-test for independent samples (two-tailed) was used to compare the CV score with categorical factors. All analyses were performed with the SPSS v.26 statistical software, with statistical significance set at 0.05.

3. Results

We enrolled 54 patients from January 2020 to July 2021 in the outpatient clinic dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension, University Cardiology Division, University Hospital of Pisa.

All patients included in the study had no abnormalities on chest x-ray, lung function tests or electrocardiogram. We excluded eight patients with a high probability of PH on the resting echocardiogram. The remaining 46 were admitted to the study. Table A1 and Table A2 report the baseline characteristics, medical and drug histories of the entire study cohort with respect to the presence and absence of isolated ExPH at CPET and ESE, respectively. In our cohort, 72% (n = 33) of the enrolled population did not develop ExPH at ESE and 91% (n = 30) of these patients also did not develop ExPH at CPET, with a Cohen’s kappa = 0.678, indicating moderate agreement in the diagnosis of isolated ExPH between the two different methods (Figure 1). The mean age of the 46 participants included in the study was 53 ± 11. The age of those with ExPH diagnosed by CPET (Table A1) and ESE (Table A2) was 52 ± 14 years and 51 ± 13 years, respectively, while the age of those without ExPH at CPET and ESE was 54 ± 10 and 55 ± 10, respectively. We observed no statistically significant differences in patients with and without ExPH on CPET and ESE in terms of mean body surface index (BSA) age, sex, body mass index (BMI), heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, history of hypertension, comorbidities, CV risk factors and concomitant drug use, bio-humoral data and proinflammatory markers such as IL-6, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen (Table A1 and Table A2). Patients diagnosed with ExPH, both on CPET (Table A1) and ESE (Table A2), had reduced functional capacity compared to patients without ExPH (p < 0.001), while they did not show significant differences in terms of morphology and function of the right or left ventricle (Table A3 and Table A4). Patients with ExPH had higher values of sPAP (p < 0.001), TRV (p = 0.048), right atrial area (p = 0.008) and pulmonary vascular resistance (velocity ratio Peak TR and VTIRVOT > 0.20, p <0.003), compared to patients without ExPH (Table A4). We did not observe any correlation between the diagnosis of ExPH at CPET and the echocardiographic parameters associated with the pulmonary circulation and the right chambers, with the exception of sPAP (Table A3).

Figure 1.

Concordance of exercise stress echocardiography and the cardiopulmonary exercise test in the diagnosis of isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension. Abbreviations: ESE, exercise stress echocardiogram; ExPH, exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test.

We evaluated the CV risk score in all 46 patients. The population’s overall CV risk score ranged from 8 (low CV risk) to 14 (high CV risk), with an average of 10.2 ± 2.4. The isolated ExPH diagnosed by both CPET and ESE was directly correlated to a higher CV score (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Patients with a higher CV score also had lower CD4+ T-cell counts (p = 0.001), a higher proportion of clinical progression to AIDS (p < 0.001) and a poor immunological response to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) (p = 0.035) (Table 2) and a higher right atrial area (p = 0.006) at rest TTE compared to patients with a lower CV risk score (Table 3). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with PVRI (ratio of Peak TR velocity to VTIRVOT) > 0.20 and higher CV score was increased compared to patients with a lower CV score (p = 0.003), indicating higher total pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with higher CV risk (Table 3). No associations with time to HIV diagnosis, time to beginning ART, ART discontinuation, virological response to ART, current use of protease inhibitors and proinflammatory markers such as IL-6, ESR, CRP and fibrinogen were found (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison between score and ExPH.

| CV Score | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| ExPH at CPET | <0.001 | |

| no | 8.8 (0.7) | |

| yes | 12.9 (2.1) | |

| ExPH at ESE | <0.001 | |

| no | 8.9 (1.1) | |

| yes | 12.5 (2.4) |

CV score values are shown as mean (SD). Abbreviations: ExPH, isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; ESE, exercise stress echocardiogram.

Table 2.

Comparison between score and virological and immunological factors.

| Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to HIV diagnosis (y) | −0.155 | 0.309 |

| CD4+ T-cell count at diagnosis (cell/mmc) | −0.402 | 0.012 |

| CD4+ T-cell count at diagnosis (%) | −0.380 | 0.020 |

| CD4+ T-cell count last determination (cell/mmc) | −0.386 | 0.009 |

| CD4+ T-cell count last determination (%) | −0.480 | 0.001 |

| Clinical progression to AIDS | <0.001 | |

| no | 8.8 (1.1) | |

| yes | 12.9 (2) | |

| Development of resistance to ART | 0.451 | |

| no | 9.8 (2.1) | |

| yes | 10.4 (2.7) | |

| HIV-RNA levels at diagnosis (cp/mL) | −0.116 | 0.502 |

| HIV-RNA levels last determination (cp/mL) | 0.010 | 0.949 |

| HIV-RNA levels last determination (cp/mL) | 0.949 | |

| <20 cp/mL | 9.9 (2.3) | |

| >20 cp/mL | 10 (2.3) | |

| Time to beginning of ART | −0.182 | 0.226 |

| Current use of protease inhibitors | 0.101 | |

| no | 9.8 (2.2) | |

| yes | 11.5 (2.7) | |

| Combination of ART with booster (ritonavir or cobicistat) | 0.827 | |

| no | 10.1 (2.4) | |

| yes | 9.9 (2.4) | |

| Virologic response to ART | 0.690 | |

| <20 copies/mL | 9.7 (2.2) | |

| 20–50 copies/mL | 10.1 (2.3) | |

| 50–200 copies/mL | 11.5 (3.5) | |

| >200 copies/mL | 10.7 (2.9) | |

| Immunologic response to ART | 0.035 * | |

| optimal | 9.3 (1.8) | |

| acceptable | 10.6 (2.6) | |

| not acceptable | 12.3 (2.9) | |

| ART discontinuation | 0.536 | |

| no | 10.2 (2.4) | |

| yes | 9.7 (2.3) | |

| IL-6 | 0.289 | 0.152 |

| PCR | −0.247 | 0.224 |

| VES | 0.194 | 0.354 |

| FBG | −0.053 | 0.789 |

Statistics: Pearson’s r or mean (SD). Abbreviations: HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; ART, antiretroviral therapy; IL-6, interleukin-6; PCR, reactive C protein; VES, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FBG, fibrinogen. * only the comparison between “optimal” and “not acceptable” was statistically significant with a p = 0.040, by Dunnett correction using “not acceptable” as the reference category.

Table 3.

Comparison between score and ultrasound parameters.

| Parameter | Statistics | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Concentric remodeling | 0.557 | |

| no | 9.9 (2.2) | |

| yes | 10.3 (2.6) | |

| Normal geometry | 0.755 | |

| no | 10.1 (2.4) | |

| yes | 9.9 (2.3) | |

| Concentric hypertrophy | 0.014 | |

| no | 10.2 (2.4) | |

| yes | 8.7 (0.6) | |

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 0.383 | |

| no | 10 (2.3) | |

| yes | 11.5 (3.5) | |

| LAD | −0.055 | 0.718 |

| LAV | −0.076 | 0.620 |

| iLAV | −0.067 | 0.667 |

| LVEF | −0.164 | 0.281 |

| FwSV | −0.097 | 0.527 |

| iFwSV | −0.112 | 0.465 |

| MR | −0.102 | 0.503 |

| AO | −0.146 | 0.339 |

| MS | −0.069 | 0.651 |

| AS | −0.069 | 0.651 |

| E wave | 0.116 | 0.448 |

| A wave | 0.153 | 0.315 |

| Septal e wave | 0.025 | 0.871 |

| E/A | −0.107 | 0.485 |

| E/e | 0.178 | 0.242 |

| iRVESA | 0.133 | 0.385 |

| iRVEDA | 0.069 | 0.652 |

| iRVESV | 0.124 | 0.419 |

| iRVEDV | −0.133 | 0.385 |

| RD1 | 0.075 | 0.626 |

| RD2 | −0.215 | 0.157 |

| RD3 | −0.275 | 0.068 |

| RVOT prox. | −0.081 | 0.596 |

| RVOT dist. | 0.071 | 0.644 |

| Eccentricity index | −0.207 | 0.171 |

| RV/LV basal diameter ratio | −0.192 | 0.205 |

| TAPSE | 0.088 | 0.564 |

| FAC | 0.179 | 0.240 |

| RV E/A | −0.140 | 0.358 |

| RV E/e | −0.026 | 0.869 |

| RV S vel | 0.151 | 0.322 |

| RV S VTI | −0.245 | 0.104 |

| TR | −0.127 | 0.407 |

| sPAP | −0.018 | 0.906 |

| aPAP at exercise peak | 0.269 | 0.074 |

| mPAP | 0.036 | 0.814 |

| TRV | 0.115 | 0.454 |

| TRV at exercise peak | 0.032 | 0.834 |

| RV outflow AT | 0.207 | 0.173 |

| VCI diameter | −0.048 | 0.753 |

| RA area | 0.401 | 0.006 |

| iRAV | 0.273 | 0.070 |

| VTI at rvot | −0.583 | 0.000 |

| VRT/VTI at rvot | 0.197 | 0.196 |

| TAPSE/PAPs | 0.101 | 0.508 |

| PVRI | 0.003 | |

| <0.20 | 8.88 (1.23) | |

| >0.20 | 12.10 (2.55) |

Statistics: Pearson’s r or mean (SD). Abbreviations: LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricle end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricle end-systolic volume; iLVEDV, indexed LVEDV; iLVESV, indexed LVESV; LAD, left atrial diameter; LAV, left atrial volume; iLAV, indexed LAV; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; FwSV, forward stroke volume; iFwSV, indexed FwSV; iRVESA, indexed right ventricle end-systolic area; iRVEDA, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic area; iRVESV, indexed right ventricle end-systolic volume; iRVEDV, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic volume; RD, right diameter; RVOT, right ventricle outflow; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane excursion; FAC, fractional area change; VTI, velocity time integral; sPAP, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; mPAP, mean PAP; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; IVC, inferior vena cava; iRAV, indexed right atrial volume; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; PVRI, Pulmonary Vascular Resistance Index.

4. Discussion

We investigated whether isolated ExPH is associated with a higher CV risk score in patients with HIV without a high probability of PH at resting echocardiogram. We have found that patients who develop ExPH have a higher CV risk score, as assessed by the ESC/ERS Guidelines [1]. We have found that isolated ExPH is associated with worse WHO-FC, shorter walk distance at the 6MWT and a lower VO2 peak, indicating worse functional capacity. The worst CV risk score was actually clustered into the isolated ExPH group, suggesting the usefulness of ExPH in assessing CV risk of patients with HIV. This is supported by the fact that patients with a worse CV risk score who also had isolated ExPH showed worse echo parameters related to PH and its consequences on the right cardiac chambers, as these patients had a higher total pulmonary vascular resistance and a higher right atrial area at rest TTE. Our results suggest that the work-out of ExPH using the combined ESE and CPET approach allows for the identification of those patients with HIV who develop ExPH due to reduced pulmonary vasodilatory reserve and who have a worse CV risk profile.

Unlike the previous study, where we only used the echocardiographic approach in diagnosing ExPH [12], here we used a combined CPET-ESE approach to non-invasively assess cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to exercise. Several studies have shown that in different clinical settings, CPET is more sensitive and specific than ESE in identifying pulmonary vascular abnormalities precipitated by exercise [22]. In our cohort we could not evaluate the differential performance of CPET and ESE in detecting ExPH as we did not perform right stress cardiac catheterization, which is the reference gold standard [1]. However, we have shown that there is good agreement in diagnosis between the two different methods, as demonstrated by the high Cohen’s kappa index. However, the benefit of performing a combined CPET-ESE is the identification of concomitant left heart disease as the cause of exertional dyspnea and ExPH. Increased left ventricle filling pressure is known to lead to pulmonary venous congestion and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension, regardless of LVEF [23,24]. In our cohort, TEE at rest and ESE ruled out the existence of left heart disease as a possible cause of ExPH, regardless of the method used for diagnosis.

We have recently shown that the onset of ExPH, as diagnosed by ESE, is associated with poor immunological control of HIV infection [11]. Here we have found that those patients who have worse immunological control of the disease also have a higher CV risk score. Finally, patients with a higher CV risk score also had greater clinical progression to AIDS and poorer immunological response to ART. This confirms previous studies demonstrating the role of a weakened or dysfunctional immune system in determining CV risk and prognosis of HIV-related PAH [2,25,26]. Thus, isolated ExPH can identify patients with HIV at higher CV risk as a consequence of poorer immune control of the disease. PAH often complicates HIV infection and this leads to the increased mortality of these patients. We are now demonstrating that the development of isolated ExPH in such patients without a high PH probability at rest can be considered an early marker of a worsening outcome.

HIV proteins can trigger an inflammatory response, leading to PAH [27]. Patients with HIV have elevated levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and nitric oxide synthase (NO) inhibitors [28,29]. The inflammation theory of PAH is biologically and clinically plausible, as PAH continues to manifest significantly in patients with HIV as an expression of the persistence of this inflammatory component, despite a good response to ART [30]. However, so far there are no clinical studies that correlate high levels of these proinflammatory mediators with the development of PAH in patients with HIV. An exploratory Phase 1 clinical study, the first of its kind to our knowledge, is still ongoing to test the effects of a combination of the HIV protease inhibitors saquinavir and ritonavir on proinflammatory mediators and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with idiopathic PAH (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02023450). Therefore, the blood levels of these mediators may currently be useful biomarkers in the stratification of patients with HIV with a higher atherosclerotic CV risk, but not those who have a propensity to develop HIV-related PAH. On the other hand, these biomarkers are not included in any of the validated risk scores in patients with PAH group 1, including patients with HIV. In our cohort, we did not observe any significant association between levels of IL-6 or other proinflammatory markers and ExPH or a worse CV risk score. However, only a few patients had such biomarkers evaluated. Further investigation with more patients is needed to establish the role of proinflammatory biomarkers in the development of PAH and a worse CV risk score.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations: (1) the small sample size, for which our report should be intended as a pilot study on the role of ExPH in risk stratification of patients with HIV; (2) patients with ExPH at ESE and CPET did not undergo cardiac catheterization, which is, however, not indicated, and therefore unethical in such patients with low and intermediate probability of PH [1]. Finally, adequate follow-up could allow us to verify if patients with ExPH develop PH at rest, and if this is associated with a worsening of CV risk over time. Our research group is carrying out a long-term follow-up, which will help to clarify the prognostic significance of ExPH in the HIV population.

In conclusion: Isolated ExPH associates with a higher CV risk score in patients with HIV. Assessment of ExPH by CPET or ESE can contribute to the risk stratification of patients with HIV.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm11092447/s1, online text: methods.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographics, medical history and medication use according to presence and absence of ExPH at CPET.

| Clinical Parameter | ExPH at CPET | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | no | 54.21 | 9.76 | 0.615 |

| yes | 52.38 | 13.86 | ||

| BSA | no | 1.91 | 0.20 | 0.475 |

| yes | 1.86 | 0.24 | ||

| SAP | no | 126.36 | 12.20 | 0.652 |

| yes | 124.62 | 10.50 | ||

| DAP | no | 74.24 | 7.08 | 0.745 |

| yes | 75.00 | 7.07 | ||

| ExPH at CPET | ||||

| no | yes | |||

| Sex | F | 11 | 5 | 0.742 |

| M | 22 | 8 | ||

| Smoke | no | 16 | 3 | 0.264 |

| yes | 16 | 9 | ||

| Functional class FC-WHO | I | 32 | 3 | <0.001 |

| II | 1 | 0 | ||

| III | 0 | 10 | ||

| Chronic liver disease | no | 16 | 8 | 0.425 |

| yes | 17 | 5 | ||

| Kidney disease | no | 29 | 12 | 0.664 |

| yes | 4 | 1 | ||

| Thyroid disease | no | 29 | 11 | 0.767 |

| yes | 4 | 2 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | no | 29 | 13 | 0.189 |

| yes | 4 | 0 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | no | 10 | 6 | 0.309 |

| yes | 23 | 7 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | no | 29 | 11 | 0.767 |

| yes | 4 | 2 | ||

| Familiarity for CAD | no | 26 | 10 | 0.891 |

| yes | 7 | 3 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | no | 29 | 12 | 0.206 |

| yes | 4 | 0 | ||

| Hypoglycemic drugs | no | 10 | 6 | 0.309 |

| yes | 23 | 7 | ||

| Beta blockers | no | 32 | 13 | 0.526 |

| yes | 1 | 0 | ||

| ACE inhibitors or sartanics | no | 32 | 13 | 0.526 |

| yes | 1 | 0 | ||

| Thyroid hormones | no | 29 | 11 | 0.767 |

| yes | 4 | 2 | ||

| Lipid lowering drugs | no | 10 | 6 | 0.309 |

| yes | 23 | 7 | ||

Abbreviations: ExPH, isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; BSA, body surface area; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; F, female; M, male; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

Table A2.

Demographics, medical history and medication use according to presence and absence of ExPH at ESE.

| Factor | ExPH at ESE | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | no | 54.58 | 9.94 | 0.391 |

| yes | 51.46 | 13.33 | ||

| BSA | no | 1.90 | 0.20 | 0.932 |

| yes | 1.89 | 0.25 | ||

| Heart rate | no | 69.03 | 6.30 | 0.839 |

| yes | 68.62 | 5.98 | ||

| yes | 126.92 | 9.47 | ||

| DAP | no | 73.79 | 7.18 | 0.308 |

| yes | 76.15 | 6.50 | ||

| ExPH at ESE | ||||

| Factor | no | yes | p-value | |

| Sex | F | 12 | 4 | 0.720 |

| M | 21 | 9 | ||

| Smoke | no | 15 | 4 | 0.570 |

| ex | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 17 | 8 | ||

| Functional class FC-WHO | I | 31 | 4 | <0.001 |

| II | 1 | 0 | ||

| III | 1 | 9 | ||

| Chronic liver disease | no | 15 | 9 | 0.146 |

| yes | 18 | 4 | ||

| Kidney disease | no | 29 | 12 | 0.664 |

| yes | 4 | 1 | ||

| Thyroid disease | no | 28 | 12 | 0.499 |

| yes | 5 | 1 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | no | 30 | 12 | 0.880 |

| yes | 3 | 1 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | no | 9 | 7 | 0.088 |

| yes | 24 | 6 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | no | 28 | 12 | 0.499 |

| yes | 5 | 1 | ||

| Familiarity for CAD | no | 27 | 9 | 0.351 |

| yes | 6 | 4 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | no | 30 | 11 | 0.937 |

| yes | 3 | 1 | ||

| Hypoglycemic drugs | no | 9 | 7 | 0.088 |

| yes | 24 | 6 | ||

| Beta blockers | no | 33 | 12 | 0.107 |

| yes | 0 | 1 | ||

| ACE inhibitors or sartanics | no | 32 | 13 | 0.526 |

| yes | 1 | 0 | ||

| Thyroid hormones | no | 28 | 12 | 0.499 |

| yes | 5 | 1 | ||

| Lipid lowering drugs | no | 9 | 7 | 0.088 |

| yes | 24 | 6 | ||

Abbreviations: ExPH, isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension; ESE, exercise stress echocardiography; BSA, body surface area; F, female; M, male; CAD, coronary artery disease; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

Table A3.

ExPH at CPET vs. continuous or categorical ultrasound parameters.

| Continuous Ultrasound Parameters | ExPH at CPET | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDD | no | 43.656 | 5.522 | 0.959 |

| yes | 43.558 | 5.978 | ||

| LVESD | no | 26.656 | 6.439 | 0.442 |

| yes | 24.917 | 7.090 | ||

| LVEDV | no | 103.875 | 31.270 | 0.299 |

| yes | 93.000 | 28.451 | ||

| iLVEDV | no | 36.676 | 10.597 | 0.163 |

| yes | 31.559 | 10.808 | ||

| LVESV | no | 38.219 | 14.041 | 0.314 |

| yes | 33.167 | 16.219 | ||

| iLVESV | no | 13.416 | 4.944 | 0.384 |

| yes | 11.923 | 5.184 | ||

| LV | no | 152.884 | 48.281 | 0.443 |

| yes | 140.817 | 38.913 | ||

| iLVmass | no | 79.132 | 29.520 | 0.255 |

| yes | 68.110 | 24.111 | ||

| LAD | no | 48.359 | 8.571 | 0.919 |

| yes | 48.083 | 5.744 | ||

| LAV | no | 38.778 | 20.368 | 0.294 |

| yes | 32.317 | 7.786 | ||

| iLAV | no | 13.683 | 7.657 | 0.468 |

| yes | 12.000 | 3.149 | ||

| LVEF | no | 65.147 | 6.406 | 0.584 |

| yes | 66.500 | 9.200 | ||

| FwSV | no | 72.366 | 22.197 | 0.268 |

| yes | 63.750 | 24.000 | ||

| iFwSV | no | 25.367 | 7.810 | 0.195 |

| yes | 21.745 | 8.944 | ||

| MR | no | 0.688 | 0.780 | 0.027 |

| yes | 0.250 | 0.452 | ||

| AO | no | 0.250 | 0.672 | 1.000 |

| yes | 0.250 | 0.622 | ||

| E wave | no | 69.769 | 17.989 | 0.993 |

| yes | 69.817 | 14.658 | ||

| A wave | no | 71.397 | 30.384 | 0.783 |

| yes | 74.167 | 26.889 | ||

| Septal e wave | no | 9.959 | 3.003 | 0.837 |

| yes | 9.767 | 1.837 | ||

| E/A | no | 1.067 | 0.394 | 0.909 |

| yes | 1.085 | 0.629 | ||

| E/e | no | 6.458 | 3.408 | 0.299 |

| yes | 7.575 | 2.193 | ||

| iRVESA | no | 4.055 | 1.879 | 0.396 |

| yes | 4.578 | 1.542 | ||

| iRVEDA | no | 6.955 | 2.143 | 0.991 |

| yes | 6.947 | 2.343 | ||

| iRVESV | no | 7.161 | 4.907 | 0.908 |

| yes | 7.338 | 2.902 | ||

| iRVEDV | no | 16.048 | 6.550 | 0.220 |

| yes | 13.507 | 4.273 | ||

| RD1 | no | 36.128 | 7.270 | 0.822 |

| yes | 36.667 | 6.372 | ||

| RD2 | no | 33.472 | 5.483 | 0.116 |

| yes | 30.333 | 6.513 | ||

| RD3 | no | 20.503 | 6.485 | 0.041 |

| yes | 16.083 | 5.351 | ||

| RVOT prox. | no | 31.716 | 6.057 | 0.627 |

| yes | 30.792 | 3.905 | ||

| RVOT dist. | no | 32.353 | 7.471 | 0.166 |

| yes | 29.042 | 5.163 | ||

| eccentricity index | no | 0.941 | 0.110 | 0.475 |

| yes | 0.914 | 0.103 | ||

| RV/LV basal diameter ratio | no | 0.864 | 0.162 | 0.317 |

| yes | 0.808 | 0.162 | ||

| TAPSE | no | 21.913 | 7.104 | 0.707 |

| yes | 22.842 | 7.665 | ||

| FAC | no | 45.053 | 9.607 | 0.210 |

| yes | 49.083 | 8.554 | ||

| RV E/A | no | 4.338 | 13.318 | 0.389 |

| yes | 0.963 | 0.408 | ||

| RV E/e | no | 3.673 | 1.829 | 0.683 |

| yes | 3.938 | 1.891 | ||

| RV S vel | no | 10.993 | 4.485 | 0.630 |

| yes | 11.767 | 5.301 | ||

| RV S VTI | no | 3.608 | 4.050 | 0.024 |

| yes | 1.810 | 0.926 | ||

| TR | no | 1.219 | 0.491 | 0.862 |

| yes | 1.250 | 0.622 | ||

| sPAP | no | 22.375 | 5.752 | 0.749 |

| yes | 21.750 | 5.675 | ||

| sPAP at exercise peak | no | 32.847 | 10.602 | 0.028 |

| yes | 40.767 | 9.452 | ||

| mPAP | no | 16.333 | 3.623 | 0.969 |

| yes | 16.385 | 4.636 | ||

| TRV | no | 2.009 | 0.373 | 0.622 |

| yes | 2.075 | 0.449 | ||

| TRV at exercise peak | no | 2.544 | 0.555 | 0.557 |

| yes | 2.658 | 0.616 | ||

| RV outflow AT | no | 102.714 | 42.717 | 0.014 |

| yes | 138.167 | 34.821 | ||

| VCI diameter | no | 15.016 | 3.777 | 0.571 |

| yes | 14.158 | 5.896 | ||

| RA area | no | 14.709 | 3.227 | 0.295 |

| yes | 15.875 | 3.294 | ||

| iRAV | no | 5.356 | 2.191 | 0.410 |

| yes | 5.924 | 1.420 | ||

| VTI at rvot | no | 15.843 | 3.811 | <0.001 |

| yes | 11.167 | 2.916 | ||

| VRT/VTI at rvot | no | 0.156 | 0.142 | 0.414 |

| yes | 0.191 | 0.051 | ||

| TAPSE/PAPs | no | 1.033 | 0.347 | 0.609 |

| yes | 1.100 | 0.471 | ||

| Categorical ultrasound parameters | ExPH at ESE | no | yes | p-value |

| Concentric remodeling | no | 19 | 5 | 0.293 |

| yes | 13 | 7 | ||

| Normal geometry | no | 18 | 7 | 0.901 |

| yes | 14 | 5 | ||

| Concentric hypertrophy | no | 29 | 12 | 0.272 |

| yes | 3 | 0 | ||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | no | 31 | 12 | 0.536 |

| yes | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ExPH, isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricle end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricle end-systolic volume; iLVEDV, indexed LVEDV; iLVESV, indexed LVESV; LAD, left atrial diameter; LAV, left atrial volume; iLAV, indexed LAV; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; FwSV, forward stroke volume; iFwSV, indexed FwSV; iRVESA, indexed right ventricle end-systolic area; iRVEDA, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic area; iRVESV, indexed right ventricle end-systolic volume; iRVEDV, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic volume; RD, right diameter; RVOT, right ventricle outflow; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane excursion; FAC, fractional area change; VTI, velocity time integral; sPAP, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; mPAP, mean PAP; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; IVC, inferior vena cava, iRAV, indexed right atrial volume; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; ESE, exercise stress echocardiogram.

Table A4.

ExPH at ESE vs. continuous or categorical ultrasound parameters.

| Continuous Ultrasound Parameters | ExPH at ESE | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDD | no | 43.459 | 5.322 | 0.745 |

| yes | 44.083 | 6.445 | ||

| LVESD | no | 26.625 | 6.460 | 0.472 |

| yes | 25.000 | 7.058 | ||

| LVEDV | no | 100.938 | 31.460 | 0.992 |

| yes | 100.833 | 29.489 | ||

| iLVEDV | no | 35.857 | 10.955 | 0.568 |

| yes | 33.743 | 10.596 | ||

| LVESV | no | 36.406 | 14.555 | 0.752 |

| yes | 38.000 | 15.486 | ||

| iLVESV | no | 12.992 | 5.205 | 0.971 |

| yes | 13.054 | 4.604 | ||

| LV | no | 149.453 | 44.358 | 0.974 |

| yes | 149.967 | 51.515 | ||

| iLV mass | no | 77.544 | 28.061 | 0.593 |

| yes | 72.343 | 29.882 | ||

| LAD | no | 48.531 | 8.481 | 0.737 |

| yes | 47.625 | 6.057 | ||

| LAV | no | 38.844 | 19.955 | 0.276 |

| yes | 32.142 | 10.252 | ||

| iLAV | no | 13.895 | 7.507 | 0.290 |

| yes | 11.452 | 3.692 | ||

| LVEF | no | 66.459 | 7.437 | 0.157 |

| yes | 63.000 | 6.030 | ||

| FwSV | no | 73.022 | 24.849 | 0.155 |

| yes | 62.000 | 13.671 | ||

| iFwSV | no | 25.663 | 8.952 | 0.090 |

| yes | 20.957 | 4.347 | ||

| MR | no | 0.656 | 0.787 | 0.193 |

| yes | 0.333 | 0.492 | ||

| AO | no | 0.313 | 0.738 | 0.304 |

| yes | 0.083 | 0.289 | ||

| E wave | no | 68.084 | 18.606 | 0.284 |

| yes | 74.308 | 10.979 | ||

| A wave | no | 71.400 | 30.367 | 0.784 |

| yes | 74.158 | 26.943 | ||

| Septal e wave | no | 10.128 | 2.958 | 0.384 |

| yes | 9.317 | 1.908 | ||

| E/A | no | 1.037 | 0.397 | 0.415 |

| yes | 1.166 | 0.613 | ||

| E/e | no | 6.251 | 3.400 | 0.077 |

| yes | 8.129 | 1.778 | ||

| iRVESA | no | 4.083 | 1.862 | 0.492 |

| yes | 4.505 | 1.622 | ||

| iRVEDA | no | 7.029 | 2.113 | 0.708 |

| yes | 6.749 | 2.405 | ||

| iRVESV | no | 7.183 | 4.886 | 0.950 |

| yes | 7.278 | 3.001 | ||

| iRVEDV | no | 16.217 | 6.461 | 0.126 |

| yes | 13.058 | 4.326 | ||

| RD1 | no | 35.987 | 6.920 | 0.660 |

| yes | 37.042 | 7.344 | ||

| RD2 | no | 33.188 | 5.538 | 0.297 |

| yes | 31.092 | 6.712 | ||

| RD3 | no | 20.031 | 6.699 | 0.222 |

| yes | 17.342 | 5.520 | ||

| RVOT prox. | no | 31.119 | 5.782 | 0.505 |

| yes | 32.383 | 4.882 | ||

| RVOT dist. | no | 31.656 | 7.305 | 0.754 |

| yes | 30.900 | 6.468 | ||

| Eccentricity index | no | 0.943 | 0.112 | 0.335 |

| yes | 0.908 | 0.096 | ||

| RV/LV basal diameter ratio | no | 0.852 | 0.157 | 0.815 |

| yes | 0.839 | 0.179 | ||

| TAPSE | no | 21.707 | 6.949 | 0.495 |

| yes | 23.392 | 7.958 | ||

| FAC | no | 45.397 | 9.376 | 0.391 |

| yes | 48.167 | 9.609 | ||

| RV E/A | no | 4.333 | 13.319 | 0.391 |

| yes | 0.976 | 0.431 | ||

| RV E/e | no | 3.729 | 1.882 | 0.946 |

| yes | 3.774 | 1.739 | ||

| RV S vel | no | 10.950 | 4.497 | 0.561 |

| yes | 11.883 | 5.251 | ||

| RV S VTI | no | 3.174 | 3.328 | 0.867 |

| yes | 2.968 | 4.289 | ||

| TR | no | 1.313 | 0.471 | 0.077 |

| yes | 1.000 | 0.603 | ||

| sPAP | no | 22.344 | 6.003 | 0.794 |

| yes | 21.833 | 4.896 | ||

| sPAP at exercise peak | no | 30.909 | 8.846 | <0.001 |

| yes | 45.933 | 7.504 | ||

| mPAP | no | 16.351 | 3.802 | 0.991 |

| yes | 16.337 | 4.212 | ||

| TRV | no | 2.009 | 0.389 | 0.622 |

| yes | 2.075 | 0.409 | ||

| TRV at exercise peak | no | 2.472 | 0.502 | 0.048 |

| yes | 2.850 | 0.659 | ||

| RV outflow AT | no | 105.027 | 43.990 | 0.065 |

| yes | 132.000 | 36.352 | ||

| VCI diameter | no | 14.722 | 4.534 | 0.885 |

| yes | 14.942 | 4.191 | ||

| RA area | no | 14.253 | 3.127 | 0.008 |

| yes | 17.092 | 2.710 | ||

| iRAV | no | 5.266 | 2.186 | 0.189 |

| yes | 6.166 | 1.300 | ||

| VTI at rvot | no | 16.065 | 3.552 | <0.001 |

| yes | 10.575 | 2.703 | ||

| VRT/VTI at rvot | no | 0.153 | 0.143 | 0.289 |

| yes | 0.198 | 0.041 | ||

| TAPSE/PAPs | no | 1.024 | 0.321 | 0.448 |

| yes | 1.123 | 0.516 | ||

| Categorical ultrasound parameter | ExPH at ESE | no | yes | p-value |

| Concentric remodeling | no | 19 | 5 | 0.293 |

| yes | 13 | 7 | ||

| Normal geometry | no | 18 | 7 | 0.901 |

| yes | 14 | 5 | ||

| Concentric hypertrophy | no | 29 | 12 | 0.272 |

| yes | 3 | 0 | ||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | no | 31 | 12 | 0.536 |

| yes | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ExPH, isolated exercise pulmonary hypertension; ESE, exercise stress echocardiogram; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricle end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricle end-systolic volume; iLVEDV, indexed LVEDV; iLVESV, indexed LVESV; LAD, left atrial diameter; LAV, left atrial volume; iLAV, indexed LAV; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; FwSV, forward stroke volume; iFwSV, indexed FwSV; iRVESA, indexed right ventricle end-systolic area; iRVEDA, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic area; iRVESV, indexed right ventricle end-systolic volume; iRVEDV, indexed right ventricle end-diastolic volume; RD, right diameter; RVOT, right ventricle outflow; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane excursion; FAC, fractional area change; VTI, velocity time integral; sPAP, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; mPAP, mean PAP; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; IVC, inferior vena cava, iRAV, indexed right atrial volume; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna); methodology, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna); software, R.M. (Riccardo Morganti); validation, RDC, F.M. (Francesco Menichetti) and R.I.; formal analysis, R.M. (Riccardo Morganti); investigation, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna), F.B., S.F., L.R. and A.F.; resources, R.D.C.; data curation, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna) and S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna); writing—review and editing, R.D.C. and S.F.; visualization, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna); project administration, R.D.C. and F.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. (Rosalinda Madonna). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Comitato Etico di Area Vasta Nord Ovest (CEAVNO) (protocol code 21315_ DE_CATERINA, date of approval 15 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by from Ministero dell’Istruzione, Università e Ricerca Scientifica, grant number 549901_2020_Madonna:Ateneo. The APC was funded by 549901_2020_Madonna:Ateneo.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Galie N., Humbert M., Vachiery J.L., Gibbs S., Lang I., Torbicki A., Simonneau G., Peacock A., Vonk Noordegraaf A., Beghetti M., et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunes H., Humbert M., Sitbon O., Morse J.H., Deng Z., Knowles J.A., Le Gall C., Parent F., Garcia G., Hervé P., et al. Prognostic factors for survival in human immunodeficiency virus-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167:1433–1439. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-330OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolle J.J., Waxman A.B., Van Horn T.L., Pappagianopoulos P.P., Systrom D.M. Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;118:2183–2189. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.787101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doukky R., Lee W.Y., Ravilla M., Lateef O.B., Pelaez V., French A., Tandon R. A novel expression of exercise induced pulmonary hypertension in human immunodeficiency virus patients: A pilot study. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2012;6:44–49. doi: 10.2174/1874192401206010044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkotob M.L., Soltani P., Sheatt M.A., Katsetos M.C., Rothfield N., Hager W.D., Foley R.J., Silverman D.I. Reduced exercise capacity and stress-induced pulmonary hypertension in patients with scleroderma. Chest. 2006;130:176–181. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saggar R., Sitbon O. Hemodynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Current and future perspectives. Am. J. Cardio. 2012;110:S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis G.D., Bossone E., Naeije R., Grünig E., Saggar R., Lancellotti P., Ghio S., Varga J., Rajagopalan S., Oudiz R., et al. Pulmonary vascular hemodynamic response to exercise in cardiopulmonary diseases. Circulation. 2013;128:1470–1479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin V.V., Archer S.L., Badesch D.B., Barst R.J., Farber H.W., Lindner J.R., Mathier M.A., McGoon M.D., Park M.H., Rosenson R.S., et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2250–2294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madonna R., Bonitatibus G., Vitulli P., Pierdomenico S.D., Galie N., De Caterina R. Association of the European Society of Cardiology echocardiographic probability grading for pulmonary hypertension with short and mid-term clinical outcomes after heart valve surgery. Vasc. Pharm. 2020;125–126:106648. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2020.106648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borlaug B.A., Nishimura R.A., Sorajja P., Lam C.S., Redfield M.M. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010;3:588–595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.930701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madonna R., Morganti R., Radico F., Vitulli P., Mascellanti M., Amerio P., De Caterina R. Isolated Exercise-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Associates with Higher Cardiovascular Risk in Scleroderma Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1910. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madonna R., Fabiani S., Morganti R., Forniti A., Mazzola M., Menichetti F., De Caterina R. Exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension in HIV patients: Association with poor clinical and immunological status. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2021;139:106888. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2021.106888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicari R., Nihoyannopoulos P., Evangelista A., Kasprzak J., Lancellotti P., Poldermans D., Voigt J.U., Zamorano J.L. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC) Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2008;9:415–437. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagel C., Henn P., Ehlken N., D’Andrea A., Blank N., Bossone E., Böttger A., Fiehn C., Fischer C., Lorenz H.M., et al. Stress Doppler echocardiography for early detection of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015;17:165. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argiento P., Chesler N., Mule M., D’Alto M., Bossone E., Unger P., Naeije R. Exercise stress echocardiography for the study of the pulmonary circulation. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;35:1273–1278. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudski L.G., Lai W.W., Afilalo J., Hua L., Handschumacher M.D., Chandrasekaran K., Solomon S.D., Louie E.K., Schiller N.B. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. quiz 786–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumgartner H., Hung J., Bermejo J., Chambers J.B., Evangelista A., Griffin B.P., Iung B., Otto C.M., Pellikka P.A., Quiñones M. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.029. quiz 101–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cagnina A., Michaux S., Ancion A., Cardos B., Damas F., Lancellotti P. European guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Rev. Med. Liege. 2021;76:208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belardine R., III . Il Test da Sforzo Cardiopolmonare. Midia; Monza, Italy: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wassermann K. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing and Cardiovascular Health. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badesch D.B., Champion H.C., Gomez Sanchez M.A., Hoeper M.M., Loyd J.E., Manes A., McGoon M., Naeije R., Olschewski H., Oudiz R.J., et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:S55–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sciume M., Mattiello V., Cattaneo D., Bucelli C., Orofino N., Gandolfi L., Pettine L., Lonati S., Gianelli U., Pierini A., et al. Early detection of pulmonary hypertension in primary myelofibrosis: The role of echocardiography, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, and biomarkers. Am. J. Hematol. 2017;92:E47–E48. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guazzi M. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure preserved ejection fraction: Prevalence, pathophysiology, and clinical perspectives. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014;7:367–377. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler K.M., Willens H.J., Mallon S.M. Diastolic left ventricular dysfunction leading to severe reversible pulmonary hypertension. Am. Heart J. 1993;126:234–235. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(07)80038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quezada M., Martin-Carbonero L., Soriano V., Vispo E., Valencia E., Moreno V., de Isla L.P., Lennie V., Almería C., Zamorano J.L. Prevalence and risk factors associated with pulmonary hypertension in HIV-infected patients on regular follow-up. Aids. 2012;26:1387–1392. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354f5a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degano B., Guillaume M., Savale L., Montani D., Jaïs X., Yaici A., Le Pavec J., Humbert M., Simonneau G., Sitbon O. HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: Survival and prognostic factors in the modern therapeutic era. Aids. 2010;24:67–75. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328331c65e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feinstein M.J., Hsue P.Y., Benjamin L.A., Bloomfield G.S., Currier J.S., Freiberg M.S., Grinspoon S.K., Levin J., Longenecker C.T., Post W.S., et al. Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e98–e124. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pellicelli A.M., Palmieri F., D’Ambrosio C., Rianda A., Boumis E., Girardi E., Antonucci G., D’Amato C., Borgia M.C. Role of human immunodeficiency virus in primary pulmonary hypertension—Case reports. Angiology. 1998;49:1005–1011. doi: 10.1177/000331979804901206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parikh R.V., Scherzer R., Nitta E.M., Leone A., Hur S., Mistry V., Macgregor J.S., Martin J.N., Deeks S.G., Ganz P., et al. Increased levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine are associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension in HIV infection. Aids. 2014;28:511–519. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tcherakian C., Couderc L.J., Humbert M., Godot V., Sitbon O., Devillier P. Inflammatory mechanisms in HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013;34:645–653. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.