Abstract

Background

The COVID19 pandemic has caused a mental health crisis worldwide, which may have different age-specific impacts, partly due to age-related differences in resilience and coping. The purposes of this study were to 1) identify disparities in mental distress, perceived adversities, resilience, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic among four age groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65); 2) assess the age-moderated time effect on mental distress, and 3) estimate the effects of perceived adversities on mental distress as moderated by age, resilience and coping.

Methods

Data were drawn from a longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample (n = 7830) administered during the pandemic. Weighted mean of mental distress and adversities (perceived loneliness, perceived stress, and perceived risk), resilience, and coping were compared among different age groups. Hierarchical random-effects models were used to assess the moderated effects of adversities on mental distress.

Results

The youngest age group (18–34) reported the highest mental distress at baseline with the mean (standard error) as 2.70 (0.12), which showed an incremental improvement with age (2.27 (0.10), 1.88 (0.08), 1.29 (0.07) for 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 groups respectively). The older age groups reported lower levels of loneliness and perceived stress, higher perceived risk, greater resilience, and more relaxation coping (ps < .001). Model results showed that mental distress declined slightly over time, and the downward trend was moderated by age group. Perceived adversities, alcohol, and social coping were positively,whereas resilience and relaxation were negatively associated with mental distress. Resilience and age group moderated the slope of each adversity on mental distress.

Conclusions

The youngest age group appeared to be most vulnerable during the pandemic. Mental health interventions may provide resilience training to combat everyday adversities for the vulnerable individuals and empower them to achieve personal growth that challenges age boundaries.

Keywords: Mental health, Health disparity, Resilience, Coping, Age disparity, COVID-19, Pandemic

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global mental health crisis (e.g., Saladino et al., 2020). Older adults (age ≥65 years) have been found to be more vulnerable to the infection due to their increased comorbidities and weakened immunity compared to their younger counterparts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). However, it has been found that individuals at younger age are more vulnerable to stress, negative affect, depression, and anxiety in general or among those with certain health conditions such as cancer (Cohen et al., 2014; Hinz et al., 2009; Hopwood et al., 2010; McCleskey and Gruda, 2021; Varma et al., 2021). During the pandemic, younger adults (18–30 years of age) in multiple countries have reported the greatest increase in psychological distress compared to other age groups (Jung et al., 2020; McGinty et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Rossell et al., 2021; Varma et al., 2021). Some researchers have attributed the age disparities in mental health to younger adults' social roles, such as greater career demands, parenting duties, and economic burdens (Arndt et al., 2006; Kornblith et al., 2007) as well as older adults’ increased experiences in coping with challenges and adversities with effective coping strategies (Brandtstädter, 1999). Despite the age disparities in social roles and coping resources, older adults may nevertheless experience an unprecedented degree of social isolation and loneliness due to COVID-19 (World Health Organization, 2020) that may adversely impact their mental health (Kowal et al., 2020, Robb et al., 2020).

Resilience is defined as positive adaptation in the context of significant risk of adversity (Cohen et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2009; Wood and Bhatnagar, 2015). It refers to the capacity to recover or bounce back from adverse life events through adjusting to changing situational demands (Cohen et al., 2014; Dyer and McGuinness, 1996; Ong et al., 2009; Richardson, 2002). Human beings cultivate resilient qualities to experience growth through adversities and to build resilient reintegration (Rutter, 1985). Resilience mitigates the negative effects of stressors on mental health (Wagnild, 2009; Wagnild and Young, 1993). For example, it has been found that a higher level of perceived personal control (an aspect of resilience) is related to a lower level of negative affect (Diehl and Hay, 2010), lower reactivity to daily life stressors (Hahn, 2000; Neupert et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2005), and reduced stress-anxiety association (Neupert et al., 2007). Resilience factors, such as meaningfulness and self-reliance, are inversely related to the level of depression, anxiety, and stress (Lenzo et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience is especially important in that individuals with lower resilience reported a greater increase in psychological distress (Killgore et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2021).

Empirical evidence shows that resilience is a learned dynamic process or a skill set that grows with age (Leys et al., 2020; Nygren et al., 2005) and may be improved with education and therapeutic interventions (Loprinzi et al., 2011; Richardson and Waite, 2002). Resilience in older adults is especially demonstrated in emotional regulation and problem solving (Gooding et al., 2012), as they are more effective than young adults at regulating negative emotions, rationally assessing situations, applying prior knowledge, and predicting outcomes (Mather, 2006). Thus older adults typically experience lower anxiety than their younger counterparts (McCleskey and Gruda, 2021).

The concept of resilience is closely related to active coping, which is conductive to stress reduction and mental health amelioration. The resistance to social defeat stress may be considered as an adaptation that occurs with repeated exposures to stress (Wood and Bhatnagar, 2015). Active coping is characterized by behavioral responses using one's own resources to minimize the physical, psychological or social harm of a situation, such as creating a sense of coherence, exercising self-control, developing a sense of identity and purpose in life (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980). An active coping style was shown to be protective against psychotic symptomatology during the pandemic, independent of demographic factors (Song et al., 2020). Conversely, passive coping is characterized by feelings of helplessness, reliance on others for stress resolution, and behaviors such as avoidance, substance use, and blaming (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980; Billings and Moos, 1984, Yi et al., 2005). Passive or maladaptive coping is associated with psychopathology. Previous research has revealed that psychosis is positively associated with avoidant coping, but inversely associated with adaptive coping (Mian et al., 2018; Ventura et al., 2004). However, whether a specific coping strategy is adaptive is a fluid concept: it varies with situations and types of stressors (Wood and Bhatnagar, 2015). For example, passive coping can be sometimes adaptive and increases chance of survival when time is limited or the stressor cannot be altered (such as past events).

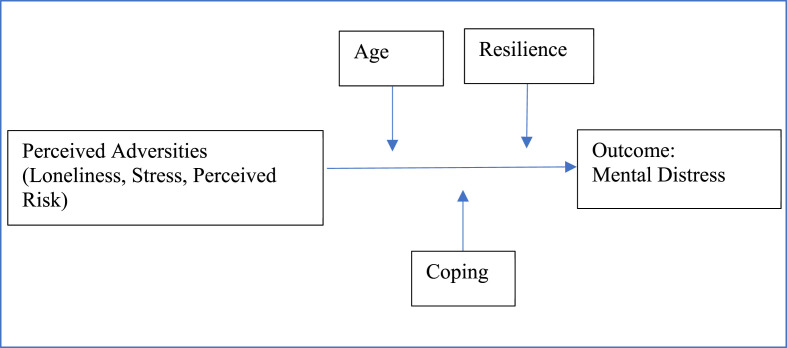

Efficient coping during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic would be critical for mental health protection. The objectives of this study were: 1) to identify disparities in mental distress, perceived adversities, resilience, and coping behaviors by age group; 2) to assess the time effect on mental distress as moderated by age group, and 3) to examine whether and how age, resilience and coping behaviors moderated the detrimental effects of perceived adversities on mental health. Fig. 1 displays the conceptual model.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual model of age, resilience, and coping modified association of adversity with mental distress.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data were drawn from Understanding America Study's (UAS) longitudinal online survey related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Understanding America Study, 2020). The UAS is a probability-based internet panel representative of the US population of adults excluding institutionalized individuals and military personnel (Angrisani et al., 2019). The UAS was first launched by the University of Southern California (USC) in 2014 and adopted a multi-phase (mail, web) recruitment of households through an address-based sampling frame. The UAS panel is an open cohort, which recruits new participants on a fixed schedule. A UAS panel of 8815 individuals was invited to participate in the COVID-19 survey and 7145 of them participated in the first wave of the study in March 2020 (Understanding America Study, 2020). Respondents were subsequently assessed every two weeks. To minimize the bias associated with inequitable Internet access, the USC provided Internet access and a tablet to the participants who did not have their own Internet access or devices (Center for Economic and Social Research, N.D.). The surveys were delivered in English and Spanish. The core COVID-19 module included questions on such topics as personal experiences with COVID-19, risk perceptions, adoption of preventive behaviors, coping behaviors, and mental health. To address selective nonresponses and consequent bias of the sample characteristics, post-stratification weights were created to correct sampling probabilities and match distribution of demographic characteristics to external distributions.

The present study used de-identified, publicly available data collected by UAS, and it was exempt from the ethics approval of the Institutional Review Board. Details on the UAS COVID data are available on their website (https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php). The current study included 18 survey waves (Wave 4 to 21) over the period from April 2020 to January 2021, with 112,054 observations from 7830 unique participants. The first three waves were excluded due to the lack of key questions assessing resilience, loneliness, and certain coping behaviors.

2.2. Outcome variable

Mental distress was assessed by the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ4) (Kroenke et al., 2009), which asked the respondents how often they had been bothered by each of the four problems over the past 14 days: 1) Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge; 2) Not being able to stop or control worrying; 3) Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless; 4) Little interest or pleasure in doing things. Responses were based on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3): not at all (0), several days (1), more than half of the days (2), and nearly every day (3). Cronbach's alpha for this construct was 0.91. The sum score was used to index mental distress (range 0–12).

2.3. Independent variables: perceived adversities

Perceived stress was measured with the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS4, Cohen et al., 1983), which asked how often the respondents felt stressed in the past 14 days: 1) unable to control the important things in your life; 2) confident about your ability to handle your personal problems; 3) that things were going their way; and 4) difficulties were piling up so high that they could not overcome them. Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale: never (1), almost never (2), sometimes (3), fairly often (4), and very often (5). Responses were reverse coded whenever appropriate so that a higher score would indicate greater stress. Cronbach's alpha for this construct was 0.65. Perceived stress was indexed by the sum score (ranged 4–20).

Loneliness was measured by a single item: “In the past 7 days, how often have you felt lonely?” Respondents rated loneliness on a 4-point Likert scale: not at all or less than 1 day (1), 1–2 days (2), 3–4 days (3), and 5–7 days (4). The exact score was used to index loneliness.

Perceived risk was assessed by perceived risk of death and hospitalization from COVID-19, contracting COVID-19, and running out of money in the next three months. Each item was rated based on a scale of 0%–100%. Cronbach's alpha for this construct was 0.72. The total risk was calculated as the average of these items and divided by 10, to keep its scale largely comparable to other independent variables (range 0–10).

2.4. Moderators

Age group was categorized as four groups: 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and 65 and above.

Resilience was assessed with the six questions from the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS, Smith et al., 2008). Example items were “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”; “I have a hard time making it through stressful events”; “It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event.” Respondents rated each question on a 5-point Likert scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.86. The Resilience was indexed by the sum score (range 6–30).

Coping behaviors included social coping, relaxation, and alcohol use. For social coping, respondents were asked to estimate the number of days that they did each of the following activities in the past seven days (range 0–7): connecting socially with friends or family (either online or in-person); posting or browsing social medias (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat); having a phone or video call with a family member or a friend; messaging/emailing a family member or friend; interacting with a family member or friend in-person. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.70. For relaxation, the respondents estimated the number of days they made time to relax out of the past seven days (range 0–7). Alcohol use was indexed by the product of the number of days of alcohol consumption in the past seven days and the average amount of consumption each day (range 0–210).

2.5. Covariates/confounders

Covariates included gender (male vs. female), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college or 2-year college, and Bachelor's degree and above), household income (four quartiles), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian and Pacific Islander, Non-Hispanic mixed race), marital status (married vs. unmarried), presence of a disability (yes vs. no), and chronic conditions (yes vs. no) including asthma, high blood pressure, cancer (other than skin cancer), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, autoimmune disease, and obesity.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The weighted mean and standard error of the outcome variable mental distress, three independent adversity variables (perceived stress, loneliness, and perceived risk), resilience, and three coping behaviors were plotted over time (by survey wave) for each age group. Weighted distributions of all covariates (sociodemographics, chronic conditions, and disability), independent variables, and the outcome variable were derived from the initial wave and compared across age groups with the Chi-Square test for categorical variables and ANOVA test for continuous variables. Weighted correlations among all independent variables and the outcome were derived from the initial wave. Hierarchical random-effects models (random intercept) were employed to assess the theoretical effects of covariates on mental distress. Of all the variables included in the models, age group, gender, race/ethnicity were time-invariant and assessed in the initial wave (wave 4) or the first wave for those newly added individuals, and the other variables were time-variant. To assess the linear effect of time, survey wave was entered into all models as a continuous variable. We implemented the sandwich estimator to generate robust standard errors in all the random-effects models. Error covariance matrix was specified as unstructured. Model 1 included the age group as the independent variable, adjusted for survey wave, and covariates including sociodemographics, chronic conditions, and disability; Model 2 added each adversity variable, resilience, and three coping variables (alcohol, social coping, and relaxation) as independent variables, adjusted for survey wave and other covariates; Model 3 further added two-way interactions between 1) age group and survey wave, 2) age group and each adversity variable, 3) age group and each coping strategy, and three-way interactions between 1) age group, resilience, and each adversity, 2) age group, each coping strategy, and each adversity, and 3) age group, resilience and each coping strategy. To keep Model 3 parsimonious, only the significant interactions remained in the model. With a focus on linear relationships, no quadratic terms were added. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis including age as a continuous variable in all three models was conducted to assess the generalizability of our findings. All above analyses incorporated survey weights and were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Our random-effects model results were derived from complete observations from any single wave. The complete data on all covariates in any wave included 109,424 observations, accounting for 97.65% of all available observations from 7755 unique respondents. About 46.8% of respondents participated in all 18 waves. The number of actual waves completed by each respondent ranged from 1 to 18, with a mean of 14.1 waves per person. The proportion of missing observations out of available observations due to the inclusion of only complete data was 4.05%, 2.52%, 1.66%, and 1.39% for age group 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 respectively. With the assumption of missing at random (MAR), we implemented a multiple imputation procedure (n = 10) within the Bayesian framework in Blimp 2 as a sensitivity analysis for the random-effects models. The model-based multiple imputation procedure was demonstrated in simulations to accurately estimate the interaction effects for multilevel (repeated measures) models (Enders et al., 2020). The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was employed to obtain the parameters of the models for the multiple imputation.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

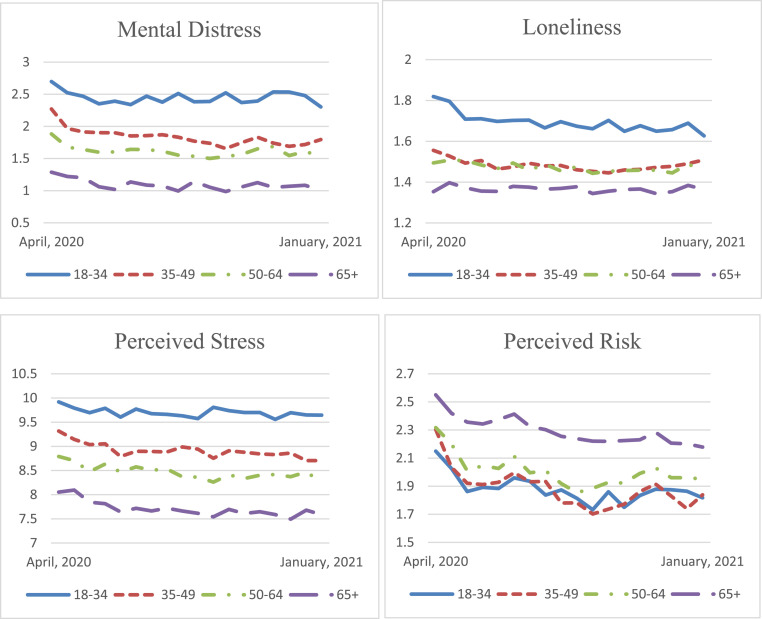

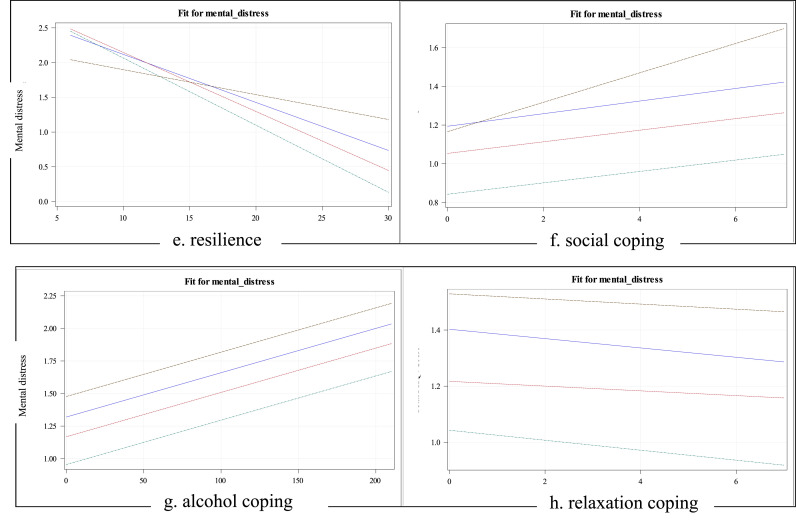

The first set of results (Fig. 2 ) shows the mean level of mental distress, perceived adversities, resilience and each coping strategy over time by age group. Note that the Y-axes in Fig. 2 were truncated to better contrast the four age groups. Table 1 shows the covariate and outcome distribution by age group in the initial wave (April 2020). Age disparities were consistent both in the initial wave and over time: the youngest age group (18–34) showed the greatest mental distress, the highest levels of loneliness and perceived stress, and the lowest level of resilience. For instance, in the initial wave, the youngest age group showed the greatest mental distress compared to the other age groups, with mean (standard error) as 2.70 (0.12), 2.27 (0.10), 1.88 (0.08), and 1.29 (0.07) for the youngest to the oldest age groups, respectively. The oldest age group perceived the highest COVID risk. In terms of coping, the younger groups (18–34, 35–49) used more social and less relaxation coping. There was no significant overall difference in alcohol coping across all age groups in the initial wave (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Series. Distribution of outcome and independent variables over time (April 2020 to January 2021) by age group.

Table 1.

Distribution of covariates and outcome by age group in the initial wave (N = 6403).

| Variable | Class | Total | Age group |

Age group |

Age group |

Age group |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 |

35–49 |

50–64 |

≥65 |

||||

| n = 1212 | n = 1823 | n = 1924 | n=1439 | ||||

| Mental Distress | 2.07 (0.05) | 2.70 (0.12) | 2.27 (0.10) | 1.88 (0.08) | 1.29 (0.07) | <.0001 | |

| Loneliness | 1.56 (0.02) | 1.82 (0.04) | 1.56 (0.03) | 1.49 (0.03) | 1.35 (0.02) | <.0001 | |

| Perceived Stress | 9.07 (0.05) | 9.92 (0.12) | 9.32 (0.1) | 8.79 (0.1) | 8.05 (0.1) | <.0001 | |

| Perceived Risk | 2.32 (0.03) | 2.15 (0.07) | 2.30 (0.07) | 2.32 (0.06) | 2.55 (0.07) | .0006 | |

| Resilience | 21.32 (0.08) | 20.24 (0.18) | 21.06 (0.15) | 21.67 (0.14) | 22.51 (0.13) | <.0001 | |

| Social Coping | 4.31 (0.03) | 4.44 (0.07) | 4.34 (0.06) | 4.33 (0.05) | 4.11 (0.06) | .0023 | |

| Relaxation Coping | 4.54 (0.04) | 4.00 (0.1) | 3.98 (0.08) | 4.81 (0.08) | 5.67 (0.07) | <.0001 | |

| Alcohol Coping | 4.43 (0.19) | 3.70 (0.33) | 4.38 (0.28) | 4.84 (0.51) | 4.82 (0.42) | .1056 | |

| Gender | Female | 3734 (51.7) | 816 (61.6) | 1095 (52.2) | 1125 (50.0) | 698 (41.2) | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 4259 (62.7) | 552 (53.9) | 1103 (56.2) | 1396 (64.1) | 1208 (81.3) | <.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 483 (11.9) | 85 (11.4) | 164 (14.5) | 167 (12.6) | 67 (8.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 996 (16.7) | 401 (23.4) | 355 (20.5) | 181 (15.3) | 59 (4.7) | ||

| Native American | 53 (0.4) | 11 (0.5) | 14 (0.4) | 21 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | ||

| AAPI | 342 (5.3) | 112 (7.0) | 108 (5.3) | 79 (4.9) | 43 (3.7) | ||

| Mixed race | 256 (3.0) | 51 (3.7) | 78 (3.2) | 78 (2.7) | 49 (2.1) | ||

| Education | <HS | 317 (8.4) | 62 (8.2) | 92 (7.5) | 104 (9.3) | 59 (9.0) | .0018 |

| HS graduate | 1059 (29.5) | 231 (28.3) | 279 (27.2) | 326 (32.4) | 223 (30.8) | ||

| Some college | 2361 (27.7) | 439 (30.5) | 624 (26.6) | 768 (29.2) | 530 (24.1) | ||

| Bachelor's degree | 2661 (34.3) | 480 (33.0) | 828 (38.7) | 726 (29.1) | 627 (36.0) | ||

| Income | 1st QT | 1491 (26.9) | 370 (31.9) | 357 (23.2) | 441 (26.4) | 323 (27.0) | <.0001 |

| 2nd QT | 1616 (26.6) | 319 (25.3) | 394 (24.1) | 474 (27.8) | 429 (30.1) | ||

| 3rd QT | 1598 (23.9) | 280 (23.3) | 477 (25.4) | 450 (21.9) | 391 (25.0) | ||

| 4th QT | 1681 (22.7) | 242 (19.5) | 594 (27.3) | 553 (23.9) | 292 (17.9) | ||

| Married | Yes | 3574 (55.7) | 407 (38.0) | 1128 (61.8) | 1140 (59.4) | 899 (63.1) | <.0001 |

| Asthma | Yes | 732 (11.7) | 142 (13.5) | 226 (12.5) | 212 (10.3) | 152 (10.1) | .0935 |

| Auto immune diseases | Yes | 387 (5.5) | 43 (3.9) | 95 (4.3) | 141 (6.8) | 108 (7.3) | .0022 |

| Cancer | Yes | 448 (5.9) | 11 (0.5) | 49 (1.8) | 147 (7.5) | 241 (16.4) | <.0001 |

| COPD | Yes | 258 (4.4) | 5 (0.3) | 24 (1.7) | 97 (5.7) | 132 (11.3) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | Yes | 774 (12.4) | 28 (2.5) | 129 (8.1) | 310 (18.3) | 307 (22.6) | <.0001 |

| Heart disease | Yes | 418 (6.5) | 9 (0.8) | 31 (2.2) | 131 (6.8) | 247 (19.3) | <.0001 |

| High Blood Pressure | Yes | 2027 (31.6) | 97 (9.5) | 353 (20.7) | 780 (44.6) | 797 (57.0) | <.0001 |

| Kidney disease | Yes | 169 (2.7) | 7 (0.8) | 20 (1.5) | 49 (2.9) | 93 (6.3) | <.0001 |

| Obesity | Yes | 1140 (16.7) | 149 (12.3) | 320 (17.3) | 389 (18.7) | 282 (18.4) | .0012 |

| Disability | Yes | 533 (9.0) | 22 (2.4) | 120 (7.3) | 290 (17.4) | 101 (8.5) | <.0001 |

Note. For continuous variables, each cell shows the weighted mean and standard error in the parathesis; for categorical variables, each cell shows the raw number and weighted percentage. HS=High School; QT=Quartile; AAPI=Asian American and Pacific Islanders; COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Table 2 reports the weighted correlations among mental distress, perceived adversities, and resilience by age group in the initial wave. All correlations were significant (p < .0001). The correlations between these variables and coping behaviors were small (r < 0.2) or not significant and thus not displayed in the table. As shown in Table 2, mental distress had moderate and positive correlations with loneliness and perceived stress, similar across age groups. Mental distress had a weak and positive correlation with perceived risk, and its magnitude was weakest in the youngest group. Mental distress had a moderate and negative correlation with resilience, with similar magnitude across age groups. Resilience was also negatively correlated with each adversity perception, with strongest correlations in the youngest group.

Table 2.

Correlations among mental distress, adversity variables, and resilience in the initial wave by age group.

| Mental Distress | Loneliness | Perceived Stress | Perceived Risk | Resilience | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Distress | 1 | |||||

| Loneliness | Total | 0.56 | 1 | |||

| 18–34 | 0.57 | 1 | ||||

| 35–49 | 0.54 | 1 | ||||

| 50–64 | 0.53 | 1 | ||||

| ≥65 | 0.56 | 1 | ||||

| Perceived Stress | Total | 0.59 | 0.46 | 1 | ||

| 18–34 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 1 | |||

| 35–49 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 1 | |||

| 50–64 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 1 | |||

| ≥65 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 1 | |||

| Perceived Risk | Total | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 1 | |

| 18–34 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 1 | ||

| 35–49 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 1 | ||

| 50–64 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 1 | ||

| ≥65 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 1 | ||

| Resilience | Total | −0.48 | −0.40 | −0.56 | −0.20 | 1 |

| 18–34 | −0.45 | −0.43 | −0.56 | −0.26 | 1 | |

| 35–49 | −0.48 | −0.37 | −0.55 | −0.21 | 1 | |

| 50–64 | −0.49 | −0.37 | −0.54 | −0.20 | 1 | |

| ≥65 | −0.46 | −0.32 | −0.47 | −0.19 | 1 | |

Note. For all correlations, p's < .0001.

3.2. Random-effects model results

Table 3 reports the fixed and random effects and model fit from three hierarchical random-effects models to assess the adjusted associations of independent variables with the outcome variable mental distress. These hierarchical models showed incremental model improvement with model complexity. Model 3 indicated the best fit. The random effect of the intercept was significant in each model. For fixed effects, Model 1 regression coefficients decreased with older age groups, suggesting mitigated mental distress with increasing age bracket. This was consistent with the mental distress graph in Fig. 2. Survey wave had a negative association with mental distress, suggesting improved mental health over time. For a complete set of covariate estimates from Model 1, see Appendix Table 1. Being male, married, Non-Hispanic Black or Native American race, making higher income, and not having certain chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, asthma, autoimmune disease, obesity, or disability, were associated with lower mental distress. Our finding on Non-Hispanic Blacks faring better in mental health during the pandemic was consistent with a previous finding using UAS data (Owens and Saw, 2021).

Table 3.

Associations of mental distress with age groups, adversities, resilience, and coping from the hierarchical random effects models.

| Model 1 Fixed Effects | Model 2 Fixed Effects | Model 3 Fixed Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B (SE) | P | B (SE) | P | B (SE) | P | |

| Intercept | 3.43 (0.19) | <.0001 | 0.94 (0.21) | <.0001 | −8.36 (0.44) | <.0001 | |

| Wave | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | −0.004 (0.002) | .0215 | 0.005 (0.004) | .2972 | |

| Age Group | 18–34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 35–49 | −0.58 (0.11) | <.0001 | −0.20 (0.07) | .0052 | 0.72 (0.22) | .0013 | |

| 50–64 | −1.03 (0.12) | <.0001 | −0.33 (0.07) | <.0001 | 0.81 (0.23) | .0004 | |

| ≥65 | −1.65 (0.12) | <.0001 | −0.55 (0.08) | <.0001 | 1.04 (0.23) | <.0001 | |

| Loneliness | 1.01 (0.03) | <.0001 | 1.48 (0.12) | <.0001 | |||

| Perceived Stress | 0.20 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.69 (0.03) | <.0001 | |||

| Perceived Risk | 0.09 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.28 (0.04) | <.0001 | |||

| Resilience | −0.12 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.25 (0.02) | <.0001 | |||

| Social Coping | 0.05 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.25 (0.04) | <.0001 | |||

| Alcohol Coping | 0.004 (0.001) | .0049 | 0.003 (0.001) | .0105 | |||

| Relaxation | −0.01 (0.01) | .0321 | 0.22 (0.03) | <.0001 | |||

| Wave*age group | 18–34 | 0 | |||||

| 35–49 | −0.02 (0.01) | .0080 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.01 (0.01) | .2941 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.01 (0.01) | .0290 | |||||

| Loneliness* Age group* Resilience |

18–34 | −0.01 (0.01) | .2228 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.02 (0.01) | .0031 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.02 (0.01) | <.0001 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.03 (0.01) | <.0001 | |||||

| Perceived Stress* Age group* Resilience |

18–34 | −0.02 (0.002) | <.0001 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.02 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.02 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.02 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| Perceived Risk* Age group* Resilience |

18–34 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.01 (0.002) | .0002 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.01 (0.002) | .0001 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | |||||

| Loneliness* Age group* Relaxation |

18–34 | −0.04 (0.01) | .0010 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.04 (0.01) | .0010 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.04 (0.01) | .0010 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.06 (0.01) | <.0001 | |||||

| Social Coping* Age Group* Resilience |

18–34 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.01 (0.002) | <.0001 | |||||

| Relaxation * Age group* Resilience |

18–34 | −0.01 (0.001) | <.0001 | ||||

| 35–49 | −0.01 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| 50–64 | −0.01 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| ≥65 | −0.01 (0.001) | <.0001 | |||||

| Model Fit | Model 1 Fit Index | Model 2 Fit Index | Model 3 Fit Index | ||||

| BIC | 421,514.8 | 395,276.8 | 393,305.3 | ||||

| Random Effects | Model 1 Random Effects | Model 2 Random Effects | Model 3 Random Effects | ||||

| Var (SE) | VAR(SE) | VAR(SE) | |||||

| Intercept | 5.24 (0.19) | 1.92 (0.07) | 1.83 (0.08) | ||||

| Residual | 2.19 (0.07) | 1.84 (0.05) | 1.82 (0.05) | ||||

Note. Var(SE) stands for variance (standard error). All models were adjusted for sociodemographics including gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, disability, and chronic conditions including asthma, high blood pressure, cancer, COPD, diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, autoimmune disease, and obesity.

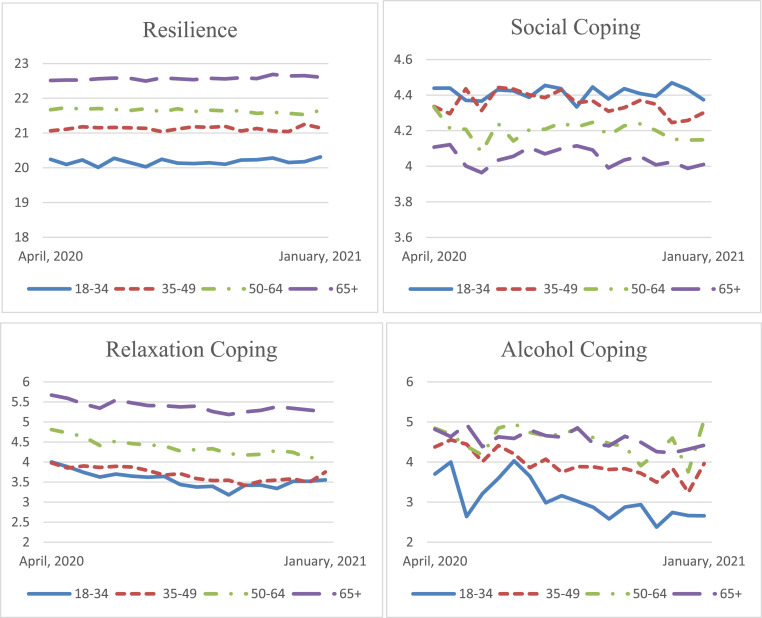

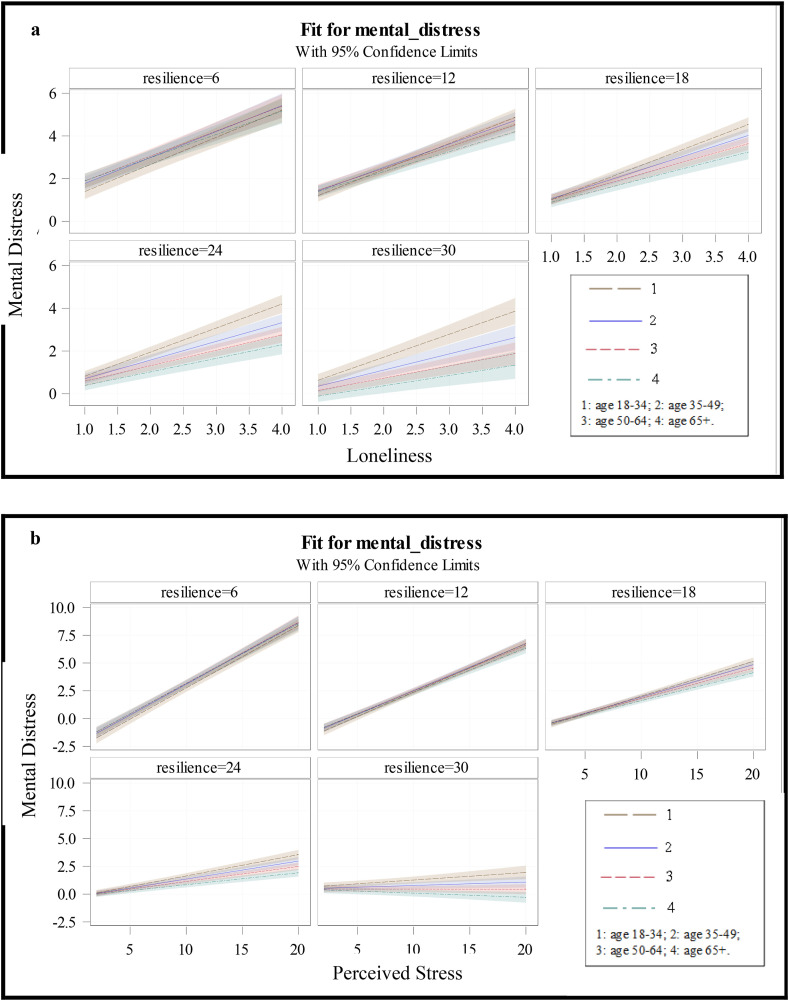

The age group effect and wave effect remained significant in Model 2 after adding perceived adversities, resilience, and coping strategies. Adversities (loneliness, stress, and risk perception) and maladaptive coping (e.g., alcohol use) were positively associated with mental distress, whereas resilience and relaxation were negatively associated with mental distress. Model 3 further included two-way and three-way interaction effects, but only the significant (p < .05) interactions were kept. Moderation effects derived from Model 3 are also displayed in Fig. 3 series and in Table 4 .

Fig. 3.

Age-moderated associations (fixed effects) of mental distress with wave (3a), loneliness (3b), perceived stress (3c), perceived risk (3d), resilience (3e), social coping (3f), relaxation coping (3g), and alcohol coping (3h).

Table 4.

Slope estimates (B) and standard errors (SE) of independent variables with significant interaction effects on mental distress, corresponding to Fig. 3 series.

| Age Group | Wave |

Loneliness |

Perceived Stress |

Perceived Risk |

Resilience |

Social Coping |

Relaxation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | |

| 18–34 | 0.005 (0.004) | .2972 | 1.13 (0.06) | <.0001 | 0.25 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.06 (0.03) | .0260 | −0.05 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.08 (0.02) | <.0001 | −0.01 (0.01) | .3010 |

| 35–49 | −0.01 (0.003) | .0034 | 0.91 (0.05) | <.0001 | 0.22 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.11 (0.02) | <.0001 | −0.08 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.03 (0.01) | .0075 | −0.02 (0.01) | .0383 |

| 50–64 | −0.001 (0.003) | .7538 | 0.78 (0.05) | <.0001 | 0.20 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.12 (0.02) | <.0001 | −0.10 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.03 (0.01) | .0480 | −0.01 (0.01) | .1730 |

| ≥65 | −0.01 (0.002) | .0081 | 0.68 (0.06) | <.0001 | 0.17 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.07 (0.01) | <.0001 | −0.11 (0.01) | <.0001 | 0.03 (0.01) | .0115 | −0.02 (0.01) | .0394 |

Fig. 3 series shows age-moderated associations of mental distress with time / wave (3a), loneliness (3 b), perceived stress (3c), perceived risk (3d), resilience (3e), social coping (3f), alcohol coping (3g), relaxation coping (3h). The slope estimates and standard errors are shown in Table 4. Over time, mental distress did not change among the youngest group and age group 50-64, but showed a slight decrease among age groups 35–49 and ≥ 65. Across all age groups, loneliness, stress, perceived risk, and both social and alcohol coping were associated with higher mental distress, whereas resilience was associated with lower mental distress. The youngest group had a slightly elevated slope of loneliness [B(SE) = 1.13 (0.06), p < .0001] and perceived stress [B(SE) = 0.25 (0.01), p < .0001] and the slope gradually decreased with older age, suggesting the effects of loneliness and stress were most detrimental on the youngest age group. The youngest group had a flattened slope of perceived risk [B(SE) = 0.06 (0.03), p = .0260] but an elevated baseline fixed (average) intercept on mental distress. This suggests that when perceived risk was zero and other variables were held constant, the youngest group showed highest mental distress, but their distress level tended to be least affected by perceived risk. The protective effect of resilience was smallest in the youngest group [B(SE) = −0.05 (0.01), p < .0001] and became stronger with older age [B(SE) = −0.08 (0.01), −0.10 (0.01) and −0.11 (0.01), all ps < .0001, for age groups 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 respectively]. For social coping, the youngest age group had a steeper slope [B(SE) = 0.08 (0.02), p < .0001] compared to other age groups. For alcohol coping, the slope was the same across age groups [B(SE) = 0.003 (0.001), p = .0105]. Relaxation coping had no effect for the youngest age group and the age group of 50–64, but it decreased mental distress for the other two age groups.

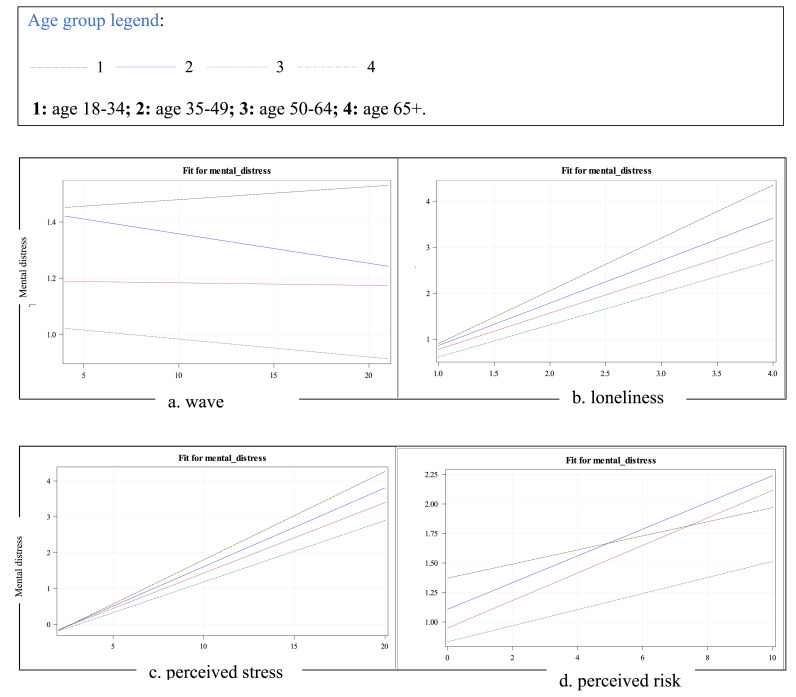

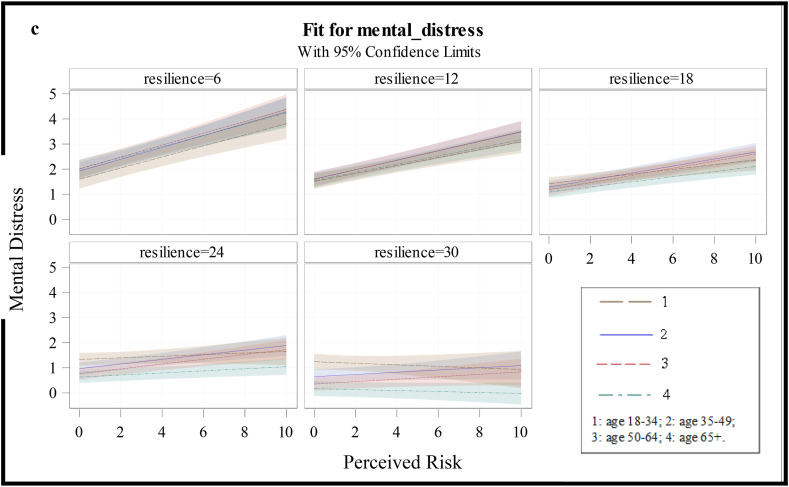

To correctly interpret the modification effects of resilience on three adversity variables – loneliness, perceived stress and perceived risk, please refer to Table 5 (i.e., significant slope estimates by increasing resilience) together with Fig. 4 (i.e., the combined effects of the fixed intercepts and slopes). Table 5 shows the predicted slope estimates of loneliness, perceived stress and perceived risk on mental distress across different levels of resilience (rows) and age groups (columns). Most slopes were significantly different from 0. The slope of loneliness on mental distress consistently decreased with resilience level for all age groups, suggesting a buffering effect of higher resilience. This is also shown in Fig. 4a. The youngest age group had the highest slope of loneliness at each fixed resilience level, indicating the greatest effect of loneliness on mental distress for this group. For perceived stress, greater resilience unanimously and consistently reduced its effect on mental distress across all age groups, indicating a consistent buffering effect of resilience. This is also shown in the gradually flattened slopes with higher resilience in Fig. 4b. Similarly, the slopes of perceived risk decreased with higher resilience across age groups, and Fig. 4c confirmed this finding as indicated in the combined effects of slopes and their fixed intercepts. Taken together, resilience was an effective buffer for the three adversity variables on mental health for all age groups.

Table 5.

Slope estimates (B) and standard errors (SE) of loneliness, perceived stress, and perceived risk on mental distress by resilience levels, corresponding to Fig. 4 series.

| Adversity and coping | Age | Slope Coefficient (B) and Standard Error (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience = 6 B(SE) |

Resilience = 12 B(SE) |

Resilience = 18 B(SE) |

Resilience = 24 B(SE) |

Resilience = 30 B(SE) |

||

| Loneliness | 18–34 | 1.26 (0.09) | 1.21 (0.06) | 1.16 (0.05) | 1.11 (0.07) | 1.07 (0.10) |

| 35–49 | 1.20 (0.09) | 1.09 (0.06) | 0.98 (0.04) | 0.86 (0.06) | 0.75 (0.09) | |

| 50–64 | 1.16 (0.09) | 1.01 (0.06) | 0.86 (0.04) | 0.71 (0.05) | 0.56 (0.08) | |

| ≥65 | 1.07 (0.09) | 0.92 (0.06) | 0.77 (0.05) | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.09) | |

| Perceived Stress | 18–34 | 0.56 (0.02) | 0.44 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.02) |

| 35–49 | 0.55 (0.02) | 0.42 (0.02) | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | |

| 50–64 | 0.55 (0.02) | 0.41 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.01) | n.s. | |

| ≥65 | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.40 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.01) | −0.04 (0.01) | |

| Perceived Risk | 18–34 | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.16 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.02) | n.s. | n.s. |

| 35–49 | 0.24 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | n.s | |

| 50–64 | 0.24 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | n.s | |

| ≥65 | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | n.s. | |

Note. n.s. Refers to not significant at p = .05 as compared to slope coefficient = 0.

Fig. 4.

Fixed effects of loneliness (4a), perceived stress (4 b), and perceived risk (4c) on mental distress, as moderated by age groups and resilience levels, corresponding to Table 5.

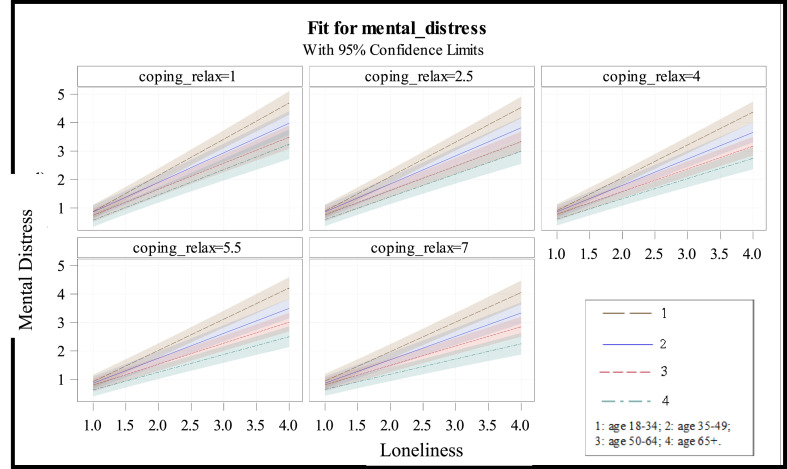

In terms of the modifying effect of coping on perceived adversities, there was only one significant interaction, which was between loneliness, relaxation, and age. With greater relaxation, the slope of loneliness on mental distress become smaller across all age groups, as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 6 . Thus, relaxation was an effective buffer for the detrimental effect of loneliness on mental distress during the pandemic. Social coping and alcohol coping did not moderate the effect of perceived adversity on mental distress.

Fig. 5.

Fixed effects of loneliness on mental distress, as moderated by age groups and relaxation levels, responding to Table 6.

Table 6.

Slope estimates (B) and standard errors (SE) of loneliness on mental distress as modified by relaxation level and age group, corresponding to Fig. 5.

| Age Group | Relaxation Level |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relax = 1 B(SE) | Relax = 2.5 B(SE) | Relax = 4 B(SE) | Relax = 5.5 B(SE) | Relax = 7 B(SE) | |

| 18–34 | 1.27 (0.07) | 1.21 (0.06) | 1.15 (0.06) | 1.10 (0.06) | 1.04 (0.07) |

| 35–49 | 1.04 (0.06) | 0.98 (0.05) | 0.93 (0.05) | 0.87 (0.05) | 0.82 (0.05) |

| 50–64 | 0.91 (0.07) | 0.85 (0.05) | 0.80 (0.05) | 0.74 (0.05) | 0.68 (0.05) |

| ≥65 | 0.89 (0.08) | 0.80 (0.07) | 0.71 (0.06) | 0.62 (0.05) | 0.53 (0.06) |

Note. Relax=Relaxation.

In the multiply-imputed data, the parameter results from 3 models were very close to those from the complete data analysis (see Appendix Table 2). In the sensitivity analysis where age was entered into the models as a continuous variable, age was also negatively associated with mental distress (see Appendix Table 3). Although the interaction effects did not completely overlap with Model 3 in which age was entered as a categorical variable, some main results remained unchanged, such as the effects of loneliness and perceived stress on mental distress as moderated by age and resilience.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify age disparities in mental health, perceived adversities, resilience and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to assess the moderation of resilience and coping behaviors on the detrimental effects of perceived adversities on mental health among different age groups. Taken together, the results largely identified the youngest age group (aged 18–34) as the most vulnerable group for mental distress, with the highest perceived adversities and lowest resilience relative to other age groups. Resilience had an age-moderated negative association with mental distress and it also effectively buffered the relationship between perceived adversities and mental health. Maladaptive coping such as alcohol use increased with mental distress, and the relationship was not moderated by age group. Similar to resilience, adaptive coping such as relaxation had both a direct negative relationship with mental distress and mitigated the age-moderated association of loneliness with mental distress. Greater social coping, usually framed as adaptive, however had an age-moderated positive association with mental distress, and it did not moderate the link between adversity and mental distress.

4.1. Age disparities in mental health, perceived adversities, resilience, and coping

The results of the current study consistently identified the youngest age group (18–34) as the most vulnerable age group, with the highest mental distress, loneliness, and stress. All of these were reported to be associated with poor psychological well-being (Beutel et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Kwag et al., 2011; Mushtaq et al., 2014; Wiegner et al., 2015). Additionally, the slope analysis suggested that loneliness is psychologically most detrimental for the youngest adults. These are consistent with previous findings of a differentially stronger inverse relationship between negative affect and perceived personal control for younger adults (Diehl and Hay, 2010) and poorer psychological outcomes in younger age groups than their older counterparts (Cohen et al., 2014; Hinz et al., 2009; Hopwood et al., 2010; Varma et al., 2021). Due to the lockdown measures implemented during the pandemic, it is not surprising that there is an elevated level of loneliness due to disconnections from real-life social networks. According to Statistics Canada, the number of people living alone has drastically increased, mostly among adults aged 35 to 64 years (Tang et al., 2019). Unlike some middle-aged and older adults who are accustomed to living alone, younger adults may experience greater impacts of social isolationduring the pandemic. The poorer mental health outcomes in younger adults could be driven by their higher career demands, parental duties, and economic needs (Arndt et al., 2006; Kornblith et al., 2007). The pandemic has led to a high unemployment rate, surpassing that of the Great Recession in the United States, according to the data reported by the Congressional Research Service (Falk et al., 2021). Thus, social disconnection, the toll of COVID-19, and financial and employment insecurity combined may explain why younger adults were most psychologically distressed and perceived the highest adversities in the present study.

We found that older adults perceived highest COVID risk, which may be due to their elevated susceptibility to the virus, such as infection, complications, and death. Nevertheless, older adults showed a generally more positive mental health profile out of all age groups, in line with earlier findings that older adults fare better during the pandemic in terms of depressive symptoms and affective experiences (Carstensen et al., 2020; Zach et al., 2021).

Consistent with earlier research (MacLeod et al., 2016; Zach et al., 2021), our study demonstrated a gradual increase in resilience with older age, which supports the conceptualization of resilience as a process instead of a personal trait, and thus could be modified and gained through experience with aging (Zach et al., 2021). In our study, resilience was negatively correlated with all three perceived adversities, suggesting that highly resilient individuals (such as some older adults) also perceive low adversities during the pandemic. Thus, it is expected that intervention programs aiming at building resilience in vulnerable individuals (such as young adults) may also reduce their perceived severity of adversities. The conjunction of increased resilience and reduced perceived adversities may provide an optimal protection for mental health outcomes. Evidence-based interventions, such as attention training, interpretation exercises directed away from fixed prejudices, and cultivation of skills such as gratitude, compassion, acceptance, forgiveness, and purpose in life, have been reported to increase resilience and decrease stress and anxiety (Loprinzi et al., 2011).

In terms of coping strategies, older age groups were more likely to adopt relaxation as a coping strategy and the youngest group used more social coping relative to other age groups. This age disparity in different coping strategies might be linked to the age-related differences in perception of the pandemic and in the availability and ease of use of different coping resources. Younger individuals perceived COVID-19 infection as less of a threat so they were still differentially more socially engaged as measured by the social coping scale, whereas older adults perceived the infection as more severe and may reduced social interactions to minimize infection risk. In addition, compared to older adults, younger adults may have a greater need for socialization and greater access to social resources (such as social media platforms) and advanced technology which became critical during the pandemic. Older adults, mostly retired, tend to engage in more relaxation, potentially due to their flexible schedule and reduced workload. Although alcohol use had no overall significant difference across all age groups in the initial wave, with further analysis, we found a downward trend of alcohol use over time and a significant interaction between age group and time. The decline was significantly slower in older age groups (50–64, ≥65) compared to the youngest group. Multiple studies worldwide found that alcohol use decreased from the pre- to post-COVID-19 period among young adults (Vera et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2021; Ryerson et al., 2021). Specific to the US, the reasons for alcohol consumption reduction among college students above legal drinking age were stipulated as loss of access to establishments (e.g., bars and restaurants) that sold alcohol and relocation from the campus to the family home setting during the pandemic (Ryerson et al., 2021).

4.2. The moderation effects of resilience and coping

The current study largely supports the protective effect of resilience and adaptive coping such as relaxation. In contrast, perceived adversities, social coping, and alcohol use showed detrimental effect on mental health. These results are consistent with past research that denotes maladaptive or passive coping as linked to psychopathology (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980), whereas adaptive coping could be beneficial to mental health (Song et al., 2020).

In the current study, we quantified and visualized the buffering effects of resilience and relaxation on mental distress. Resilience greatly mitigates the effect of perceived adversities on mental distress for all age groups, consistent with the earlier findings (Killgore et al., 2020; Wagnild, 2009). Relaxation unanimously buffers the detrimental effects of loneliness on mental distress. Consistent with literature (Gao et al., 2019), this suggests that an adaptive coping strategy could reduce the negative impact of stressors on psychological health.

However, in a time when social isolation is required and beneficial to health, social coping may not be as protective for mental health as expected from pre-pandemic literature (Mian et al., 2018; Ventura et al., 2004). Our results concur with a U.K. study (Fluharty and Fancourt, 2021) that found worries related to finances, basic needs, and the coronavirus during the pandemic were positively associated with endorsement of social coping. The lack of consistently beneficial effects of social coping may be intrinsic to the infectious nature of the pandemic and the prevention measures that discouraged socialization. In other words, social coping may not be perceived as adaptive and could even be perceived as discomforting or risky during the pandemic compared to other situations. Nevertheless, we should note that this study did not intend to assess the causal relationship between social coping and mental distress, and the result should be interpreted as correlational, with potential residual confounding.

4.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. The study results should be interpreted as associations, not causal relationships. The results were derived from a nationally representative online sample, and thus this study has inherent limitations of drawing data from an established database, such as unmodifiable data collection strategies and measurements. Although administrative procedures were taken to minimize the sampling bias, such as providing tablets and Internet access if needed, the sample may still show selection bias especially for the older adults. As shown in Table 1, the oldest age group had relatively low disability prevalence as compared to age group 50–64, which was at odds with literature. A report based on the data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System found that the prevalence of any type of disability (vision, cognition, mobility, self-care, and independent living) was higher among those aged 65 and above (35.5%) than those aged between 45 and 64 years (26.2%) and 18–44 years (15.7%, Courtney-Long et al., 2015). Thus, the prevalence of disability may be underestimated for all age groups, especially for the oldest one, presumably due to sample selection bias and lack of clear definition of disability in the survey question. Generalizability of the study can be improved by including individuals who are not regularly online, but this may only represent a small segment of the population, given the prevalence of online communication. According to Pew Research, the percentage of Internet use was 96% among US adults aged 50–64 and 75% among those aged 65 and above in 2021 (Pew Research Center, 2021). Given that all responses were self-reported and collected online, there could be some generational differences (e.g., comfort with self-disclosure and technology and mental health stigma) confounded with age differences. The social coping scale can be further refined to reduce redundancy and increase reliability. Future studies may consider including other coping behaviors such as religious coping and substance use.

5. Conclusions and implications

Despite of the limitations of the current study, the results nevertheless revealed pronounced age disparities in mental distress, perceived adversities, resilience and coping, as well as highlighted how resilience and coping could adaptively mitigate mental distress in this unprecedented pandemic. The results provide important insights into the mental health status and associated factors in different age groups at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. This study used timely reported longitudinal data from a nationally representative sample. The validity of the results was confirmed by further analysis with multiple imputation of missing data points. Our study is informative for mental health practitioners and policy makers to design interventions to mitigate mental distress and ameliorate psychological risk factors during a public health crisis, especially for the most vulnerable individuals. It will be important to continuously monitor and evaluate resilience and coping as the effects of COVID-19 continue to evolve and hopefully dissipate.

Author contribution

Ling Na has contributed to the conceptualization, methods, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Lixia Yang and Peter Mezo have contributed to methods, results interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Rong Liu has contributed to multiple imputation and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final revision.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115031.

Note. Each of the above graphs was plotted while continuous covariates were held at mean and dichotomous covariates at reference level.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Angrisani M., Kapteyn A., Meijer E., Wah S.H. 2019. Sampling and Weighting the Understanding America Study.https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502405 CESR-Schaeffer Working Paper(004). Available at: SSRN: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt V., Merx H., Stegmaier C., Ziegler H., Brenner H. Restrictions in quality of life in colorectal cancer patients over three years after diagnosis: a population based study. Eur. J. Cancer. 2006;42(12):1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel M.E., Klein E.M., Brähler E., Reiner I., Jünger C., Michal M., Lackner K.J. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatr. 2017;17(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings A.G., Moos R.H. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984;46(4):877–891. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J. In: Social Cognition and Aging. Hess T.M., Blanchard-Fields F., editors. Elsevier; 1999. Sources of resilience in the aging self: toward integrating perspectives; pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L.L., Shavit Y.Z., Barnes J.T. Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020;31(11):1374–1385. doi: 10.1177/0956797620967261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Economic and Social Research. (N.D.) Understanding America study. 2021. https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php?r=eNpLtDKyqi62MrFSKkhMT1WyLrYyslwwskuTcjKT9VLyk0tzU_NKEksy8_NS8svzcvITU0BqgMrzEnPByg3NrJRCHYMVnIrykzNKi1L1ClLSlKxrAQ89HTk Retrieved October 5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2021. COVID-19.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html Retrieved April 22 from. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M., Baziliansky S., Beny A. The association of resilience and age in individuals with colorectal cancer: an exploratory cross-sectional study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2014;5(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney-Long E.A., Carroll D.D., Zhang Q.C., Stevens A.C., Griffin-Blake S., Armour B.S., Campbell V.A. Prevalence of disability and disability type among adults—United States, 2013. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015;64(29):777–783. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6429a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M., Hay E.L. Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: the role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Dev. Psychol. 2010;46(5):1132–1146. doi: 10.1037/a0019937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer J.G., McGuinness T.M. Resilience: analysis of the concept. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1996;10(5):276–282. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(96)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K., Du H., Keller B.T. A model-based imputation procedure for multilevel regression models with random coefficients, interaction effects, and nonlinear terms. Psychol. Methods. 2020;25(1):88–112. doi: 10.1037/met0000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S., Alkan E., Bhangoo J.K., Tenenbaum H., Ng-Knight T. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatr. Res. 2021 Apr;298:113819. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819. Epub 2021 Feb 23. PMID: 33640864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk G., Carter J., Nicchitta I., Nyhof E., Romero P. Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: in brief. Congr. Res. Serv. 2021;46554:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty M., Fancourt D. How have people been coping during the COVID-19 pandemic? Patterns and predictors of coping strategies amongst 26,016 UK adults. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00603-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.-L., Wang L.-H., Yin X.-Q., Hsieh H.-F., Rost D.H., Zimmerman M.A., Wang J.-L. The promotive effects of peer support and active coping in relation to negative life events and depression in Chinese adolescents at boarding schools. Curr. Psychol. 2019:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding P., Hurst A., Johnson J., Tarrier N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2012;27(3):262–270. doi: 10.1002/gps.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S.E. The effects of locus of control on daily exposure, coping and reactivity to work interpersonal stressors:: a diary study. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2000;29(4):729–748. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz A., Krauss O., Stolzenburg J.-U., Schwalenberg T., Michalski D., Schwarz R. Anxiety and depression in patients with prostate cancer and other urogenital cancer: a longitudinal study. Urol. Oncol. 2009;27(4):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P., Sumo G., Mills J., Haviland J., Bliss J.M. The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: results from the UK Standardisation of Radiotherapy Trials (START) Breast. 2010;19(2):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S.J., Yang J.S., Jeon Y.J., Kim K., Yoon J.-H., Lori C., Kim H.C. SSRN Preprint; 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Psychological Health in Korea: A Mental Health Survey in Community Prospective Cohort Data. [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D., Taylor E.C., Cloonan S.A., Dailey N.S. Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;291:113216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim A.W., Nyengerai T., Mendenhall E. Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms in urban South Africa. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith A.B., Powell M., Regan M.M., Bennett S., Krasner C., Moy B., et al. Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psycho Oncol.: J. Psychol. Soc. Behav. Dimens. Cancer. 2007;16(10):895–903. doi: 10.1002/pon.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal M., Coll‐Martín T., Ikizer G., Rasmussen J., Eichel K., Studzińska A., Ahmed O. Who is the most stressed during the COVID‐19 pandemic? Data from 26 countries and areas. Appl. Psychol.: Health Well-Being. 2020;12(4):946–966. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwag K.H., Martin P., Russell D., Franke W., Kohut M. The impact of perceived stress, social support, and home-based physical activity on mental health among older adults. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2011;72(2):137–154. doi: 10.2190/AG.72.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzo V., Quattropani M.C., Musetti A., Zenesini C., Freda M.F., Lemmo D., Castelnuovo G. Resilience contributes to low emotional impact of the COVID-19 outbreak among the general population in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:576485. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leys C., Arnal C., Wollast R., Rolin H., Kotsou I., Fossion P. Perspectives on resilience: personality trait or skill? Eur. J. Trauma Dissoc. 2020;4(2):100074. [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi C.E., Prasad K., Schroeder D.R., Sood A. Stress Management and Resilience Training (SMART) program to decrease stress and enhance resilience among breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2011;11(6):364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod S., Musich S., Hawkins K., Alsgaard K., Wicker E.R. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2016;37(4):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. In: When I'm 64. National Research Council (US) Committee on Aging Frontiers in Social Psychology, Personality, and Adult Developmental Psychology. Carstensen L., Hartel R., editors. National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2006. A review of decision-making processes: weighing the risks and benefits of aging.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83778/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey J., Gruda D. Risk-taking, resilience, and state anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a coming of (old) age story. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;170:110485. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian L., Lattanzi G.M., Tognin S. Coping strategies in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis: a systematic review. Early Intervent. Psychiatr. 2018;12(4):525–534. doi: 10.1111/eip.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq R., Shoib S., Shah T., Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.: J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014;8(9):WE01–WE04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert S.D., Almeida D.M., Charles S.T. Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007;62(4):P216–P225. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren B., Aléx L., Jonsén E., Gustafson Y., Norberg A., Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment. Health. 2005;9(4):354–362. doi: 10.1080/1360500114415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A.D., Bergeman C., Bisconti T.L. Unique effects of daily perceived control on anxiety symptomatology during conjugal bereavement. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2005;38(5):1057–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Ong A.D., Bergeman C.S., Boker S.M. Resilience comes of age: defining features in later adulthood. J. Pers. 2009;77(6):1777–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens V., Saw H.-W. Black Americans demonstrate comparatively low levels of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center Internet/broadband fact sheet. 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/ Retrieved from January 17, 2022 from.

- Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., McManus S. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(10):883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G.E. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002;58(3):307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G.E., Waite P.J. Mental health promotion through resilience and resiliency education. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health. 2002;4(1):65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehm K.E., Brenneke S.G., Adams L.B., Gilan D., Lieb K., Kunzler A.M., Kalb L.G. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;282:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb C.E., de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari S., Giannakopoulou P., Udeh-Momoh C., McKeand J., Price G., Car J., Majeed A., Ward H., Middleton L. Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of older adults in London, UK. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11:591120. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossell S.L., Neill E., Phillipou A., Tan E.J., Toh W.L., Van Rheenen T.E., Meyer D. An overview of current mental health in the general population of Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;296:113660. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1985;147(6):598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson N.C., Wilson O., Pena A., Duffy M., Bopp M. What happens when the party moves home? The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. college student alcohol consumption as a function of legal drinking status using longitudinal data. Translat. Behav. Med. 2021;11(3):772–774. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladino V., Algeri D., Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Yang X., Yang H., Zhou P., Ma H., Teng C., Mathews C.A. Psychological resilience as a protective factor for depression and anxiety among the public during the outbreak of COVID-19. Running Title: protective factor of the public during COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:4104. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.618509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Galbraith N., Truong J. 2019. Insights On Canadian Society: Living Alone in Canada. Statistics Canada.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2019001/article/00003-eng.pdf?st=CTn5j5EP Retrieved May 4, 2021 from. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding America Study . 2020. Understanding Coronavirus in America.https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php Retrieved Feb 3, 2021, from. [Google Scholar]

- Varma P., Junge M., Meaklim H., Jackson M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatr. 2021;109:110236. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J., Nuechterlein K.H., Subotnik K.L., Green M.F., Gitlin M.J. Self-efficacy and neurocognition may be related to coping responses in recent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;69(2–3):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera B., Carmona-Márquez J., Lozano-Rojas Ó.M., Parrado-González A., Vidal-Giné C., Pautassi R.M., Fernández-Calderón F. Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic among young adults: the prospective effect of anxiety and depression. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10(19):4468. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild G. A review of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 2009;17(2):105–113. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild G., Young H. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993;1(2):165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegner L., Hange D., Björkelund C., Ahlborg G. Prevalence of perceived stress and associations to symptoms of exhaustion, depression and anxiety in a working age population seeking primary care-an observational study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S.K., Bhatnagar S. Resilience to the effects of social stress: evidence from clinical and preclinical studies on the role of coping strategies. Neurobiol. Stress. 2015;1:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak, 18 March 2020.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf Retrieved February 20, 2021 from. [Google Scholar]

- Yi J.P., Smith R.E., Vitaliano P.P. Stress-resilience, illness, and coping: a person-focused investigation of young women athletes. J. Behav. Med. 2005;28(3):257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-4662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zach S., Zeev A., Ophir M., Eilat-Adar S. Physical activity, resilience, emotions, moods, and weight control of older adults during the COVID-19 global crisis. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Activ. 2021;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s11556-021-00258-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.