Abstract

Background

Latinx family caregivers of individuals with dementia face many barriers to caregiver support access. Interventions to alleviate these barriers are urgently needed.

Objective

This study aimed to describe the development of CuidaTEXT, a tailored SMS text messaging intervention to support Latinx family caregivers of individuals with dementia.

Methods

CuidaTEXT is informed by the stress process framework and social cognitive theory. We developed and refined CuidaTEXT using a mixed methods approach that included thematic analysis and descriptive statistics. We followed 6 user-centered design stages, namely, the selection of design principles, software vendor collaboration, evidence-based foundation, caregiver and research and clinical advisory board guidance, sketching and prototyping, and usability testing of the prototype of CuidaTEXT among 5 Latinx caregivers.

Results

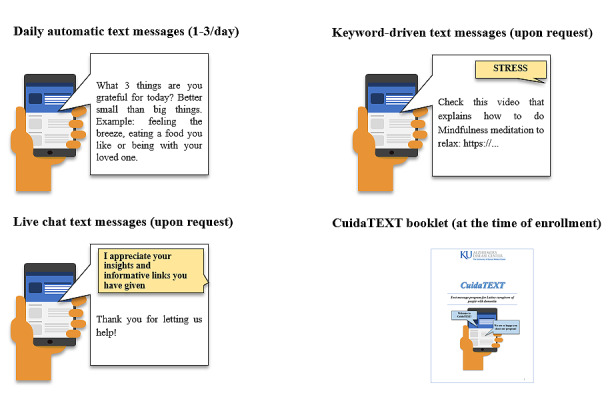

CuidaTEXT is a bilingual 6-month-long SMS text messaging–based intervention tailored to caregiver needs that includes 1-3 daily automatic messages (n=244) about logistics, dementia education, self-care, social support, end of life, care of the person with dementia, behavioral symptoms, and problem-solving strategies; 783 keyword-driven text messages for further help with the aforementioned topics; live chat interaction with a coach for further help; and a 19-page reference booklet summarizing the purpose and functions of the intervention. The 5 Latinx caregivers who used the prototype of CuidaTEXT scored an average of 97 out of 100 on the System Usability Scale.

Conclusions

CuidaTEXT’s prototype demonstrated high usability among Latinx caregivers. CuidaTEXT’s feasibility is ready to be tested.

Keywords: Latinx individuals, mHealth, dementia, caregiving

Introduction

Background

Family caregiving for individuals with dementia has a serious emotional, physical, and financial toll [1-8]. Most individuals with dementia live at home and are cared for by their relatives [9]. As the US health care system focuses mainly on acute care, relatives provide >80% of the long-term care for individuals with dementia [4,5]. For these reasons, caregiver support is a key component of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act [10].

Most family caregiver interventions have been designed for non-Latinx White individuals, and the results might not generalize to other groups because of linguistic, cultural, and contextual reasons [11-13]. The number of Latinx individuals with dementia is projected to increase from 379,000 in 2012 to 3.5 million by 2060, more than any other group [14]. Latinx individuals are more likely to become family caregivers than non-Latinx White individuals [15]. Latinx individuals also provide more intense and longer caregiving and experience higher levels of caregiver depression and burden [8,15-21]. However, despite their high interest in participating in caregiver support interventions [22], Latinx caregivers of individuals with dementia are less likely to use caregiver support services [23,24]. This disparity is partly due to Latinx caregivers’ more frequently experienced barriers related to transportation, financial, language, and cultural aspects compared with non-Latinx White caregivers [23,24]. Therefore, the need for targeted caregiver support interventions among Latinx individuals is crucial. This need is in line with the National Institute on Aging’s call to address health disparities in aging research [25].

SMS text messaging offers distinct advantages over websites and apps for delivering interventions [26-28]. Although nearly all Latinx individuals engage in SMS text messaging, Latinx individuals’ low use of websites and apps could perpetuate disparities in access to caregiving support [29]. Caregiver interventions for Latinx individuals need to capitalize on SMS text messaging, as SMS text messaging interventions (1) are effective in treating or preventing other health conditions such as tobacco addiction or diabetes; (2) can be used anywhere at any time; (3) are more cost-effective than other delivery systems; (4) can be personalized to caregivers’ preferences and characteristics including language, culture, and needs; (5) are highly scalable among Latinx individuals, as most own a cell phone with SMS texting capabilities, more than other groups; and (6) have been specifically shown to engage Latinx individuals [30-35].

Objectives

To address Latinx individuals’ disparities in access to caregiving support, we developed CuidaTEXT (a Spanish play on words for self-care and texting). To our knowledge, this is the first SMS text messaging intervention for caregiver support of individuals with dementia among Latinx individuals or any other ethnic group. Only one other SMS text messaging intervention exists in the context of dementia [36]. However, that intervention was designed to increase dementia literacy among non-Latinx Black users and is not geared toward Latinx individuals or caregivers specifically. The aim of this study was to describe the development of CuidaTEXT, a tailored SMS text messaging intervention to support Latinx family caregivers of individuals with dementia. This development corresponds to Stage 1a of the National Institutes of Health Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development (intervention generation) [37]. This intervention will later be feasibility-tested (Stage 1b) among Latinx family caregivers of 20 individuals with dementia (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04316104).

Methods

Overview

This was a mixed methods project guided by user-centered design principles [38]. The basis for user-centered design is that gathering and incorporating feedback from users into product design will lead to a more usable and acceptable product. Mixed methods are required, given the lack of literature on SMS text messaging interventions for Latinx family caregivers of individuals with dementia and the strengths of a combined qualitative and quantitative approach [39]. We followed 6 user-centered design stages informed by previous research used to develop successful behavioral intervention software [40]. The user-centered design stages are described in the next sections.

Ethics Approval

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Kansas Medical Center (STUDY00144478). All participants provided written informed consent.

Stage 1: Selection of Design Principles

A total of 2 design principles were specified. First, we selected the social cognitive theory as the main behavior change principle [41]. This principle has been successfully used in previous SMS text messaging interventions [30]. The social cognitive theory informs the identification of barriers to desired behaviors, setting of realistic goals, encouragement of gradual practice to achieve performance accomplishments of healthy behaviors (eg, relaxation techniques or exercising), integration of testimonials and videos to promote vicarious learning, integration of praise to elicit social persuasion, and education to increase dementia knowledge. Second, we chose the stress process framework [42] to guide the development of messages to encourage coping and social support behaviors (mediators), which are aimed at improving role strains (eg, perceived income adequacy and family interaction), intrapsychic strains (eg, mastery, self-esteem, and loss of self), and, ultimately, outcomes (eg, caregiver depression, affect, and self-perceived health).

Stage 2: Vendor Collaboration for Text Messaging Design and Delivery

This stage aimed to materialize the vision and design specifications of CuidaTEXT. We developed a checklist of necessary features to identify potential vendors, including message personalization, 2-way SMS text messaging, scheduling, conditional branching logic for SMS text message responses, information tracking, technical support, and cost. We identified 3 vendors based on our previous experiences and a basic internet search. The 3 identified vendors met all the features, and we selected the one with the most affordable cost. Their services also included configuration, account setup, initial onboarding, training guides and videos, access to the vendor system, mobile number support, and bug fixes during the intervention. We contracted with them early in the project to avoid delays (eg, developing the scope of work, registering as a vendor, contracts, and software programming).

Stage 3: Evidence-Based Foundation

This stage aimed to identify core content categories based on previous successful behavioral interventions. We searched specifically for general caregiver support interventions considered evidence-based informed by the Administration for Community Living [43], PubMed literature results using the Medical Subject Headings terms Caregivers, Dementia, and Hispanic Americans, and recommendations on behavioral interventions from the research team. Content categories included dementia education, problem-solving skills training, social network support, care management, and referral to community resources [1,26,27,44-58].

Stage 4: Advisory Board Guidance

Advisory board guidance provided expert opinion to inform the SMS text messaging intervention based on Latinx caregiver needs [22,40,59,60]. We conducted 5 parallel advisory board meetings with up to 6 Latinx caregivers and 16 clinicians and researchers (health professionals), each lasting 60 minutes. We used purposive sampling for the Latinx caregivers and quota sampling for the health professionals (including at least one person with expertise in psychiatry, social work, neurology, dementia care interventions, Latinx research, SMS text messaging intervention development, or behavioral health). We conducted the caregiver advisory board sessions in Spanish and the health professional group sessions in English. We held all sessions via videoconference from December 2020 to May 2021 and recorded each to facilitate notetaking and analysis. The process for each meeting was similar: the research team showed the groups a step-by-step explanation of the components of the study, asked specific questions pertinent to the phase of the study, and then facilitated open discussion about the project. The research team took detailed notes of all sessions, which were used for further analysis. We organized the notes for qualitative review using a pragmatic approach, a qualitative description methodology, and thematic analysis methods [61-63]. We coded the content of the notes using Microsoft Word by identifying codes and themes within the text [64]. In addition, 2 researchers (JPP and MAR) independently reviewed the codes and resolved coding disagreements through discussion and consensus.

Stage 5: Sketching and Prototyping

On the basis of the previous stages, 3 researchers (JPP, MAR, and PEK) brainstormed a pool of potential SMS text messages in English on a shared spreadsheet and later sorted the messages by topic (initial draft keywords). We edited messages following the Seven Principles of Communication: completeness, concreteness, courtesy, correctness, clarity, consideration, and conciseness [65]. This theory is popular in business communications and has been used in patient reporting [66,67]. Bilingual, bicultural members of the research team translated the messages into the primary Spanish dialects represented in the United States (Mexican and Caribbean).

In addition to the SMS text message libraries, we developed a reference booklet for participants that summarized the purpose of the intervention and its functions. The booklet is not necessary to use CuidaTEXT. However, the research team considered it to be useful for those who want to learn about the intervention faster or increase personal sense of agency. On the basis of our previous development experience with the Latinx community [22,30], we made the booklet available in both English and Spanish and used lay language and a pictorial format. A total of 7 research team members tested the SMS text messaging prototype powered by the vendor on their own cell phones from early June to August 2021 and provided feedback that was used for message refinement iteratively, as suggested by the literature [68,69]. We recorded the feedback via SMS text message responses within the vendor platform and emails from the research team to the vendor’s programmer. We organized the data (SMS text messages and emails) for qualitative review using a process identical to that described in Stage 4.

Stage 6: Usability Testing

Usability testing aimed to test a short prototype of the SMS text messaging intervention and assessments among actual Latinx caregivers. We used the vendor’s platform to preview the behavior and opinions of diverse Latinx caregivers in a variety of key scenarios (ie, reading specific messages, using keywords, sending SMS text messages, opening links to websites and videos, and downloading PDF files). The testing sessions were conducted via videoconference in June 2021, lasted approximately 90 minutes per person, and were conducted in English and Spanish based on participant preferences. We took detailed notes of the observations during the usability testing sessions and participants’ comments at the end.

Sample and Assessment

We recruited 5 individuals, as suggested by software development cost-benefit analyses [70]. In this framework, the first participant discovers most flaws, and after the fifth user, findings tend to repeat without learning much new. Participants were recruited from 3 previous projects at the research center using purposive sampling. Eligibility criteria included Spanish- or English-speaking individuals who were aged 18 years or older, identified as Latinx, reported providing care for a relative with a clinical or research dementia diagnosis, and with an Ascertain Dementia 8cognitive screening score ≥2, indicating cognitive impairment [71,72]. Participants also had to report owning a cell phone and being able to use it to read and send SMS text messages. Participants received US $20 prepaid gift cards for completing assessments. We used 3 usability evaluation modalities. First, direct observation of task completion (eg, texting keywords) with the intervention prototype via monitoring of participants’ SMS text message responses was conducted. Second, open-ended interviews of user experience with the different tasks and suggested changes to improve the intervention (see Multimedia Appendix 1 for a sample) were conducted. Third, the caregiver participants completed the System Usability Scale about their experience with the prototype [73]. The System Usability Scale is a valid and reliable 10-item, 5-point Likert scale. According to the developers of the scale, scores >68 out of 100 indicate higher levels of usability. We modified the design features iteratively after each participant and provided the new version to the following participant, as suggested by the literature [74]. After 2 consecutive participants reviewed and approved an SMS text message, the following participant received an SMS text message with different features. In addition to the usability evaluation, we administered a survey to gather baseline characteristics.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the qualitative data (detailed notes) from the open-ended interviews using a process identical to that described in Stage 4. We analyzed quantitative baseline characteristics using central tendency estimates, frequencies, and percentages on SPSS software (IBM Corp) [75].

Results

Overview

This section focuses on Stages 4 to 6 of the user-centered design proposed in this project. First, we summarize the findings from each stage. Second, we explain how these findings informed the intervention development within each stage. Third, we describe the final version of the intervention.

Findings From Advisory Board Guidance (Stage 4)

Table 1 shows the themes, subthemes, and descriptions of the aspects to be considered in the development of CuidaTEXT, according to the advisory boards. Both Latinx caregivers and health professionals contributed to all the themes. Building on the evidence-based foundation established in Stage 3, feedback from this stage informed the sketching and prototyping of CuidaTEXT. First, the advisory board emphasized that messages should include specific content on logistics (eg, guidance on CuidaTEXT’s functions and motivation messages), social support, caregiver needs, care recipient needs, preparation for the care recipient’s death, and reminders for physician visits or medicines. This feedback informed the addition of the suggested SMS text message content. Second, advisory board members highlighted the importance of allowing the inclusion of >1 relative within the family to reduce burden and increase social support. This feedback informed the decision to enroll >1 caregiver per individual with dementia in future studies. Third, the advisory board suggested that the domains of SMS text messages sent to caregivers should alternate often and be tailored to the needs of caregivers. This feedback informed the inclusion of high-priority message content at the beginning of the intervention (eg, who to contact in case of elder abuse or suicidal thoughts and removing weapons in the home) and the frequent alternation of domains. This feedback also reinforced the need to use 2-way SMS text messaging, as originally planned. Fourth, the preferences of caregiver advisory board members varied widely with respect to the number of messages per day CuidaTEXT should send participants. A participant emphasized that they would abandon the intervention if they received >1 message per day except at the beginning, which required more messaging. Others wanted to receive 5 or more messages per day. Eventually, a consensus was reached that CuidaTEXT should tailor the number of messages to the preferences of caregivers. This feedback informed the decision to send few daily automatic messages per day to participants (generally 1). Fifth, the advisory board emphasized the need to make keyword names as simple and recognizable as possible and suggested several edits in line with this idea. This feedback informed the refinement of some keyword names. Sixth, the advisory board suggested adding diverse information regarding COVID-19. However, after some discussion, a consensus was met not to develop automatic SMS text messages for CuidaTEXT, given the rapid evolution of COVID-19 information. This feedback informed the exclusion of COVID-19 automated information into CuidaTEXT. Seventh, an advisory board member, guided by her experience, highlighted the scarce existing resources for caregivers with hearing issues and suggested that CuidaTEXT was made as hearing impairment friendly as possible. This feedback reinforced the idea of delivering the intervention via SMS text messaging. This feedback also informed the use of hearing impairment–inclusive messaging, including SMS text messaging–based contact information of all shared resources (eg, text telephone contact numbers) and video links with closed caption subtitles. Eighth, the advisory board suggested several CuidaTEXT reference booklet edits for simplification. This feedback informed the refinement of the CuidaTEXT reference booklet.

Table 1.

Themes, subthemes, and descriptions of topics elicited during the advisory board sessions with Latinx caregivers and health professionals.

| Themes and subthemes | Description | |

| Messages should include specific content | ||

|

|

Logistics | Motivate participants to be in the program |

|

|

Dementia education | Address the whole family to be all on the same page; dementia stages and variation between individuals; signs and symptoms; address stigma by normalizing dementia |

|

|

Social support | Communication with the individual with dementia; include concrete examples (eg, allowing individuals with dementia enough time to answer) and resources (eg, Alzheimer’s Association, health professionals, services in Spanish, support groups, and legal assistance); communication with the health provider (eg, expectations, what to report, encouraging clinical diagnosis, and requesting interpreters); improve family communication (eg, understanding family roles and find strengths, knowing importance of family support, and disclosing the diagnosis to the family); and develop active listening skills (eg, reflecting and nonverbal language) |

|

|

Caregiver needs | Cope with depression, anxiety, and stress (eg, relaxation); choose one’s battles; use sense of humor; find positive aspects of caregiving; address loneliness; cope with loneliness; capitalize on spirituality; and maintain a healthy lifestyle |

|

|

Care recipient needs | Address behavioral symptoms as specifically as possible; address aggressive behavior (eg, understanding the disease causing it, distraction techniques, and communication when the person is aggressive); address anxious behavior (distraction techniques and prevention); help the individual with dementia; address daily care of the individual with dementia, including healthy eating, dressing, hygiene, and doing fulfilling activities |

|

|

Preparation for the care recipients’ death | Information about what to expect at the end of the life of the individual with dementia; grieving strategies and tips |

|

|

Appointments for the physician or medicine | Set notifications to remind caregivers of medications or physician visits |

| Need to integrate other family members | More than 1 family member should be allowed to participate, to share responsibilities, avoid burdening a caregiver by having to educate the rest, promote collective understanding about what the individual with dementia is experiencing, and reduce the isolation of the caregiving process | |

| Messages should follow a certain order | Alternate content often (eg, educational, caregiver tips, and resources) and tailor content to caregivers’ needs | |

| Messages should have a certain dose | Limit mandatory message frequency to 1 per day (in general) and tailor frequency and timing to caregivers’ preferences | |

| How to integrate COVID-19 into CuidaTEXT | Reliable education about caring during COVID-19, including what to do if infected, risks, vaccines, and vaccine locations and resources for those experiencing technological divide. As changes in COVID-19 evolve quickly, it was decided not to automate messages and send only ad hoc information as needed | |

| Some keyword names need editing | Use simple and recognizable keyword names if possible; allow platform recognition of alternative spellings and typos; and edit specific keywords: STRESS vs RELAX, GRIEF vs ENDOFLIFE or LOSS, BANO vs ORINAR, DUELO vs FINDEVIDA, PACIENTE vs SERQUERIDO | |

| CuidaTEXT could benefit people with hearing impairment | Given that SMS text messages are visual, this intervention can be optimized for people with hearing impairment | |

| Reference booklet needs editing | Shorten booklet and include fewer and more realistic examples by including a matrix of the different keyword messages | |

Findings From Sketching and Prototyping (Stage 5)

Table 2 shows the themes, subthemes, and descriptions of aspects considered in the development of CuidaTEXT based on the feedback from SMS text messages from the team during the testing of the prototype and suggestions provided by the vendor’s programmer. These aspects led to several solutions. First, we allowed the platform to recognize common misspelling or alternative spellings for keywords (eg, for the keyword Behavior, the platform should also accept Behaviour, Behaviors, Behaviours, and Behavour). Second, we edited words to eliminate misspellings or replace words that required high literacy levels or specialized knowledge (eg, glutes vs rear). Third, we used a vendor-owned link shortener to save SMS text message characters, as using a third-party link shortener could lead to phone carriers identifying messages as spam and subsequently blocking them. Fourth, we added code to embed the participant’s first name in SMS text messages to personalize them. Fifth, we adjusted the time of delivery of each daily automatic SMS text message to account for participants’ time zone. Sixth, we requested that the vendor allow keyword libraries to loop back to the first SMS text message after reaching the last one on the list.

Table 2.

Themes, subthemes, and descriptions of topics elicited during the sketching and prototyping stage, gathered via SMS text message responses from the team and correspondence with the SMS text messaging vendor.

| Themes and subthemes | Description | |

| Testing actions | ||

|

|

Testing keyword responses | Ensuring the platform responded with an automatic SMS text message instantly upon sending a specific keyword |

|

|

Testing live chat | Ensuring the platform received SMS text messages other than keywords, intended for the coach, such as “thank you!” |

|

|

Testing alternative spellings of keywords | Ensuring alternative spellings and misspellings of keywords are recognized by the platform as such |

|

|

Testing links and PDF downloads | Ensuring links to websites directed to the right place and downloaded PDF files |

|

|

Testing SMS text message reminders | Ensuring reminders for medications or physician appointments were sent at the specified date and time |

|

|

Testing other logistics | Ensuring no cross-project contamination and other features (eg, nonbusiness hours response and START keyword to enroll) |

| Concerns | ||

|

|

Messages need editing | Alerting the presence of misspellings in the SMS text message sent by the platform or suggesting editing the wording |

|

|

Need to use a different link shortener | The link shortener the team had used would be identified as spam by the cell phone carrier and blocked |

|

|

Need to embed first names in messages | The team wanted a function that automatically embedded the first name at the beginning of some SMS text messages |

|

|

Need to tailor timing to time zone | The team wondered how messages could be sent at specific times depending on participants’ time zone |

|

|

Need keyword libraries to loop | Keywords stopped sending after they reached the bottom of the library |

|

|

Need to edit out of business hours timing | The response on sending a message out of business hours was not set correctly |

|

|

Preference to embed links within words | The team wondered if links could be embedded within words that would open upon clicking on them |

Findings From Usability Testing (Stage 6)

Of the 5 participating caregivers in the usability testing, 4 (80%) were women. The mean age was 44.6 (SD 6.8; range 33-50) years. All participants were insured, and their mean level of education was 15.6 (SD 2.2; range 12-18) years. All 5 participants identified as Latinx, 40% (2/5) as Native American, 20% (1/5) as White, and 40% (2/5) as >1 race. All participants were born outside of the United States, including Mexico (1/5, 20%), Central America (2/5, 40%), and South America (2/5, 40%). All but one participant completed the intervention and assessments in Spanish, and their self-perceived level of spoken English was medium (2/5, 40%), high (1/5, 20%), and very high (2/5, 40%). Participants were daughters (3/5, 60%), a son (1/5, 20%), and a granddaughter (1/5, 20%) of an individual with dementia. Their average care recipient’s age was 77.0 (SD 5.1; range 72-83) years.

In general, participants completed the surveys and texting tasks without any major issues (eg, reading specific messages, using keywords, sending SMS text messages, opening links to websites and videos, and downloading PDF files). Observations of participants’ reactions during the usability testing and comments at the end of the testing revealed some minor concerns and generally positive feedback (Table 3). We addressed the concerns in various ways. First, we replaced expressions that were hard to understand (eg, 24/7 for Spanish speakers with at any time). Second, we added context to several SMS text messages to improve understanding. For example, we explained that a caregiver forum is a web platform to share experiences with other caregivers, that the content of a PDF file of a Latin American healthy recipe book alternated pages in English and Spanish, the function of specific keywords, the keyword options using simple graphics, that keywords can be sent more than once for additional messages, and that websites and other resources had a Spanish-language option. Third, we tailored the response to the keyword STOP (discontinuing the intervention). We also tailored the notification CuidaTEXT automatically sends out when a participant texts outside of business hours by including both languages within the same message because the platform did not allow separate messages in English and Spanish.

Table 3.

Themes, subthemes, and descriptions of topics elicited during the pilot test with 5 Latinx caregiver participants via observation or comments.

| Themes and subthemes | Description | ||

| Participants’ concerns | |||

|

|

Expressions are hard to understand | Expressions such as 24/7 or the + sign for more were hard to understand, especially for Spanish-speaking Latinx individuals | |

|

|

CuidaTXT is hard to read in Spanish | Spanish-speaking participants had issues pronouncing the original name CuidaTXT and suggested CuidaTEXT | |

|

|

Context is needed for understanding | Some SMS text messages required additional context or an explanation to be understood, for example, for the word forum | |

|

|

Branching did not work | In one instance, responding YES or NO to a specific question was not followed by a preconfigured response | |

|

|

Need to edit language of functions | The response on discontinuing the program or sending a message out of business hours was only in English | |

|

|

Need for caregiver lifestyle messages | A participant suggested adding nutrition as a healthy lifestyle action for caregivers | |

| Other comments from participants | |||

|

|

Satisfaction with the intervention | Satisfaction with the intervention in general, content, logistics, and simplicity | |

|

|

Gratitude for the intervention | Expressions of gratitude for developing the intervention | |

|

|

Highlighting need for this intervention | Highlighting the need for this intervention among Latinx individuals and themselves | |

Participants shared mostly positive feedback at the end of the interview, including the following. First, satisfaction with the intervention in terms of general content, logistics, and simplicity was high. Comments included the following: “I think the program is great,” “I love the information and the testimonials,” “The messages made me feel like I’m not alone and put things into perspective,” and “The messages are simple, and the gratitude-theme messages helped.” Second, participants expressed their gratitude to the CuidaTEXT team for developing the intervention. Comments included the following: “Thank you for creating this type of program!” Third, they expressed their need and that of the community to use this intervention. Comments included the following: “I hope we can use it soon because we need it” and “I think it’s going to be very helpful for caregivers emotionally and personally.” The mean System Usability Scale score was 97 and ranged from 90 to 100, which is above the standard cutoff of 68. These scores indicate that the intervention’s usability holds promise.

Final Product

Figure 1 summarizes the final CuidaTEXT product, including an example of the 3 types of SMS text messaging interaction modalities (daily automatic, keyword-driven, and live chat messages) and the reference booklet. The final version of CuidaTEXT includes 244 English- and 244 Spanish-language messages within the daily automatic SMS text message library. These messages will be automatically sent to all participants, starting with approximately 3 messages per day for the first 2 weeks, 2 per day for the following 2 weeks, and 1 per day for the remainder of the intervention. This daily automatic SMS text message library includes logistics messages that greet the participant on starting and completing the intervention, explain the intervention functions (eg, reminding participants of the keywords they can use for help with specific topics), and reinforce participants for being in the intervention after 2 weeks initially and monthly. The remainder of the daily automatic library includes the messages that the research team and advisory board considered the core from each domain. These domains include messages for (1) dementia education, (2) caregiver self-care messages, (3) support to and from others, (4) education about the dying and grief processes, (5) generic problem-solving strategies for behavioral symptoms, (6) specific strategies to help with the daily care of individuals with dementia, and (7) specific strategies to help address or cope with the behavioral symptoms of individuals with dementia.

Figure 1.

Final CuidaTEXT product: SMS text messaging interaction modalities and booklet.

CuidaTEXT also contains messages for 2 types of keyword-driven messages, the content keywords and menu keywords. Content keywords automatically send tips, resources, or other types of content in response to SMS text messages that include a specific keyword (eg, STRESS and RESOURCES). These keywords reflect the same domains as the daily automatic SMS text message library, except that their content is not considered core but rather an in-depth expansion for those who need further support with those domains. Menu keywords simply remind the participant which content keywords are in that category. For example, texting the menu keyword CAREGIVER will drive an automatic response reminding participants that content keywords within that domain include STRESS, WELLBEING, and LIFESYLE. Table 4 shows the function and an example of each content keyword, the menu keyword they belong to, and the number of messages in each content keyword library.

Table 4.

Keywords and their function and size of each keyword library in number of messages (n).

| Content keyword (English and Spanish) | Menu keyword (English and Spanish) | Function of content keyword | Messages, n |

| EDUCATION and EDUCACION | None | Basic dementia information: types, stages, and impact | 54 |

| STRESS and CALMA | CAREGIVER and CUIDADOR | Strategies to cope with stress, such as relaxation | 33 |

| WELLBEING and BIENESTAR | CAREGIVER and CUIDADOR | Strategies and tips to improve well-being, such as gratitude and cognitive restructuring | 30 |

| LIFESTYLE and SALUDABLE | CAREGIVER and CUIDADOR | Tips to maintain a healthy lifestyle, such as exercising | 21 |

| FAMILY and FAMILIA | SUPPORT and APOYO | Tips to improve family communication | 19 |

| DOCTOR and MEDICO | SUPPORT and APOYO | Tips to improve communication with health providers | 15 |

| PATIENT and PACIENTE | SUPPORT and APOYO | Tips to improve communication with the individual with dementia | 37 |

| CHILDREN and NINOS | SUPPORT and APOYO | Tips to communicate with children about dementia | 17 |

| LISTENING and ESCUCHA | SUPPORT and APOYO | Strategies to improve listening skills | 33 |

| RESOURCES and RECURSOS | SUPPORT and APOYO | Contact information of resources such as support groups, legal and financial assistance, or food delivery | 26 |

| SOLVE and SOLUCION | None | General strategies to solve challenging behaviors | 19 |

| GRIEF and DUELO | None | Education on end-of-life care and tips for grieving | 30 |

| ACTIVITITES and ACTIVIDADES | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to think of fun activities and adjust them to the abilities of individual with dementia | 52 |

| EATING and COMER | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to make eating easier and healthier for the individual with dementia | 36 |

| DRESSING and VESTIR | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to help the individual with dementia get dressed and groomed | 18 |

| BATHING and DUCHA | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to help the individual with dementia take a bath or shower | 24 |

| TOILET and BANO | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to manage the incontinence or constipation of the individual with dementia | 24 |

| MEDICATIONS and MEDICAMENTO | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to improve medication adherence | 27 |

| HOME and CASA | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to keep the home safe | 50 |

| DRIVE and CONDUCIR | CARE and CUIDADO | Tips to detect when it is no longer safe for the individual with dementia to drive and how to manage it | 22 |

| ANGER and ENFADO | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the aggressive behavior of the individual with dementia | 31 |

| NERVOUS and NERVIOS | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the anxious behavior of the individuals with dementia | 33 |

| DEPRESSION and TRISTE | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the depressed mood of the individual with dementia | 19 |

| DELUSIONS and DELIRIOS | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the psychotic symptoms of the individual with dementia | 22 |

| REPEAT and REPETIR | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the repetitive behaviors of the individual with dementia | 20 |

| SLEEP and DORMIR | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to improve the sleep quality of the individual with dementia | 18 |

| WANDER and DEAMBULAR | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the wandering behavior of the individual with dementia | 23 |

| INAPPROPRIATE and INAPROPIADO | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the inappropriate sexual behaviors of the individual with dementia | 18 |

| HOARDING and ACUMULAR | BEHAVIOR and CONDUCTA | Tips to cope with manage the hoarding behavior of the individual with dementia | 12 |

Any SMS text message other than keywords sent by participants will be received as a live chat by a bilingual and culturally proficient coach trained in dementia care. The coach will be available during business hours and will assist participants in whatever their need is (eg, additional information about a caregiver grant and programming 3-way calls with a clinic). The coach will have a bachelor’s degree or higher in a behavioral health-related area, will be trained in dementia care, and will be given a list of general contacts to find local resources (eg, Alzheimer’s Association hotline and Eldercare Locator). The final version of the CuidaTEXT reference booklet includes 19 pages with nine chapters: (1) What Is Dementia, (2) Signs and Symptoms of Dementia, (3) Why Focus on Latino Caregivers, (4) CuidaTEXT (Automatic Messages), (5) Assistant, (6) Notifications, (7) Keywords, (8) Materials, and (9) Contact Information.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study aimed to describe the development of CuidaTEXT, an SMS text messaging intervention, to support Latinx family caregivers of individuals with dementia. We followed user-centered design principles to ensure the intervention’s tailoring and usability among Latinx caregivers of individuals with dementia. After a series of user-centered design stages, CuidaTEXT’s prototype showed a very high usability score, indicating great promise for the intervention’s feasibility and acceptability.

Comparison With Previous Work

To our knowledge, this is the first SMS text messaging intervention for caregiver support of individuals with dementia among Latinx individuals and any other ethnic group. Very few evidence-based and culturally tailored caregiver support interventions have been developed for Latinx individuals. These interventions include fotonovelas, webnovelas, support groups, care management, and psychoeducational programs [28,45,56,57,76]. The modality of all these interventions has been individual or group face-to-face, computer-based, telephone-based, or mail-based. CuidaTEXT has the potential to address implementation gaps in these interventions by (1) increased accessibility compared with face-to-face or web-based interventions; (2) improved acceptability compared with phone-based interventions; (3) tailoring the content to the needs of caregivers rather than using rigid curricula; (4) addressing stigma by privately sending SMS text messages to the caregivers’ cell phone; and (5) reduced demand on the health care workforce to deliver the intervention, therefore improving fidelity and facilitating future scale-up of the intervention. Although CuidaTEXT was developed for Latinx individuals, similar interventions may be beneficial for other ethnic groups, especially those in rural areas, given the nearly universal cell phone ownership of most populations in the United States [31].

The advisory board suggested SMS text message content related to dementia education, social support, care, caregiver needs, community resources, and appointment reminders. These domains are most frequently included in multidomain caregiver support interventions, which have been shown to be more efficacious than single-domain interventions [1,26]. As mentioned in a recent federally commissioned report, of all interventions to improve caregiver well-being, multicomponent interventions use the most targeted components, and they possibly address at least one critical need across a wide range of individual caregiver needs, thus improving outcomes for caregiver and individuals with dementia [77].

The advisory board encouraged the inclusion of >1 family member per individual with dementia. This idea is in line with the fact that caregiving tasks and decision-making among Latinx individuals are more likely to be shared by multiple relatives of the individuals with dementia [78,79]. In fact, interventions rarely include other family members, which is likely a reflection of centering interventions on non-Latinx White caregivers [77,80]. According to our advisory board, the potential benefits of including more >1 family member may include improving caregiving quality and reducing caregiver burden.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, most participants in the usability testing stage identified as the adult children of individuals with dementia, were women, were relatively highly educated, were medically insured, and had at least a medium level of English proficiency. This sample may have placed a higher focus of the refinement of the intervention on these groups than on men, spousal caregivers, and those with lower educational attainment, who lack of medical insurance, with limited English proficiency, or who may have uniquely different needs. However, most caregivers are women, and individuals from many of these other groups were represented in other stages of the development of CuidaTEXT (eg, advisory board). Second, the eligibility to participate in the caregiver advisory board sessions and the usability testing was based on self-report of the care recipient’s dementia status. In addition, we excluded individuals who could not read and send SMS text messages. Although the size of this group is minimal [31], future efforts could include this group by developing training to those without texting experience. Third, CuidaTEXT does not consider caregivers’ baseline characteristics to tailor the automated content of SMS text messages and does not tailor the timing at which SMS text messages are sent, as suggested by some advisory board participants. We consider that including keyword-driven messages addresses many of the same concerns and reduces the reliance on a baseline assessment. Any need beyond those addressed by the keyword-driven messages can also be addressed via live chat with a coach. Fourth, this study assessed the usability of the CuidaTEXT prototype. Although this prototype included the most relevant aspects of CuidaTEXT, future studies need to assess the usability of the entire intervention.

Implications and Future Directions

This study has implications for public health, clinical practice, and research. Regarding the public health implications, CuidaTEXT or similar interventions have high potential for implementation, given their ubiquitous accessibility and reliance on technology rather than on human labor. Experts in dementia caregiver interventions highlight the importance of designing interventions with implementation in mind from the beginning of the intervention for its future success [81]. The user-centered design used to develop this intervention will increase the chances of this intervention being usable, acceptable, feasible, and effective in the future. Regarding clinical practice, usability testing participants described the prototype as something that was needed by them and the Latinx community. If CuidaTEXT proves to be effective in future studies, this intervention could be easily implemented in clinics and community organizations, by having the caregivers send an SMS text message to enroll or by having staff enter their phone numbers and names on a website. The SMS text messaging modality may be combined with other modalities to enhance its effectiveness. For example, coaches or social workers could, in addition to interacting via live chat SMS text messages, conduct ad hoc visits or calls with the caregiver. Other findings from this study might also be useful to clinicians, including the need to consider shared caregiver roles within Latinx families and other preferences. The findings reported in this manuscript may also inform future research. Future SMS text messaging studies (whether they are dementia-related or not) might decide to address the content or logistics of their interventions based on the feedback we received from the advisory board sessions or usability testing feedback. Caregiver studies might want to test the efficacy of the same caregiver support intervention to only the primary caregiver versus multiple caregivers within the same family. Future studies will test the feasibility and acceptability of CuidaTEXT among a diverse sample of Latinx caregivers, including variations in regional, linguistic, age, socioeconomic status, relationship to the individual with dementia, hearing functioning, and other important characteristics. This diverse representation will allow further intervention refinement, informed by qualitative analysis of SMS text messaging interactions and open-ended questions about their experiences using CuidaTEXT. If the future feasibility study is successful, we will conduct a fully powered randomized controlled trial to assess its efficacy.

Conclusions

This study describes the development of CuidaTEXT, the first tailored SMS text messaging intervention specifically designed to support family caregivers of individuals with dementia in the Latinx community. The prototype of CuidaTEXT has shown very high usability, addresses Latinx caregiver needs, and has the potential for widespread implementation. The findings from several stages of the user-centered design provide useful information to guide the development and refinement of caregiver support interventions for Latinx individuals and other groups. This information contributes to efforts to address dementia disparities among Latinx individuals and gaps in the implementation of caregiver support interventions for this sizable population. We will soon test the feasibility and acceptability of this promising intervention (CuidaTEXT) in a 1-arm trial among Latinx family caregivers of 20 individuals with dementia (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04316104).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grants R21 AG065755, K01 MD014177, and P30 AG072973. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, interpretation of data for the work, and drafting and critically revising the work for important intellectual content. JPP thanks the national and local organizations that have partnered with him to conduct this and other research projects since 2015. JPP also thanks the research participants included in all stages of this research as well as anyone who has contributed directly and indirectly to this research.

Sample usability testing interview.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. pp. 1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer's Association 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016 Apr;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001.S1552-5260(16)00085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertrand RM, Fredman L, Saczynski J. Are all caregivers created equal? Stress in caregivers to adults with and without dementia. J Aging Health. 2006 Aug 30;18(4):534–51. doi: 10.1177/0898264306289620.18/4/534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman EM, Shih RA, Langa KM, Hurd MD. US prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015 Oct;34(10):1637–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26438738 .34/10/1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015 Oct;34(10):1642–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26438739 .34/10/1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon H, Townsend AL, Dilworth-Anderson P, Whitlatch CJ. Predictors of discrepancy between care recipients with mild-to-moderate dementia and their caregivers on perceptions of the care recipients' quality of life. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016 Sep 09;31(6):508–15. doi: 10.1177/1533317516653819. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1533317516653819?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .1533317516653819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ory MG, Hoffman RR, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999 Apr 01;39(2):177–85. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005 Feb;45(1):90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90.45/1/90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasper J. Disability and care needs of older Americans by dementia status: an analysis of the 2011 national health and aging trends study. ASPE. [2022-04-19]. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/disability-care-needs-older-americans-dementia-status-analysis-2011-national-health-aging-trends-1 .

- 10.National plan to address Alzheimer's disease: 2016 update. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [2022-04-20]. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2016-update .

- 11.Pendergrass A, Becker C, Hautzinger M, Pfeiffer K. Dementia caregiver interventions: a systematic review of caregiver outcomes and instruments in randomized controlled trials. Int J Emergency Mental Health Human Resilience. 2015;17(2):459–68. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.903.911&rep=rep1&type=pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin L, Marx K, Stanley I, Hodgson N. Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: state-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist. 2015 Apr;55(2):210–26. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu123. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26035597 .gnu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Johnson R, Walljasper L, Block L, Werner N. Underreporting of gender and race/ethnicity differences in NIH-funded dementia caregiver support interventions. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2018 May 27;33(3):145–52. doi: 10.1177/1533317517749465. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1533317517749465?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu S, Vega WA, Resendez J, Jin H. Latinos & Alzheimer’s disease: New numbers behind the crisis. Los Angeles, California: USC Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging and the LatinosAgainstAlzheimer’s Network; 2016. p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evercare® Study of Hispanic family caregiving in the U.S. National Alliance for Caregiving. [2022-04-19]. https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/content/dam/UHG/PDF/2008/Evercare_HispanicStudyFactSheet.pdf .

- 16.Napoles AM, Chadiha L, Eversley R, Moreno-John G. Reviews: developing culturally sensitive dementia caregiver interventions: are we there yet? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010 Aug;25(5):389–406. doi: 10.1177/1533317510370957. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1533317510370957?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .1533317510370957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Guy D, Rupert M, Argüelles T, Zeiss LM, Long C, Tennstedt S, Ory M. Tailoring psychological interventions for ethnically diverse dementia caregivers. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(4):423–38. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cultural competency in working with Latino family caregivers. Family Caregiver Alliance. 2004. [2022-04-19]. https://vdocument.in/cultural-competency-in-working-with-latino-family-caregivers-cultural-competency.html .

- 19.Garcia EM. Caregiving in the context of ethnicity: Hispanic caregiver wives of stroke patients. University of California, Irvine. 1999. [2022-04-22]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304509134?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true .

- 20.Hinton L, Haan M, Geller S, Mungas D. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Latino elders with dementia or cognitive impairment without dementia and factors that modify their association with caregiver depression. Gerontologist. 2003 Oct;43(5):669–77. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinton L, Chambers D, Velásquez A, Gonzalez H, Haan M. Dementia neuropsychiatric symptom severity, help-seeking patterns, and family caregiver unmet needs in the Sacramento area Latino study on aging (SALSA) Clin Gerontol. 2006 Jun 20;29(4):1–15. doi: 10.1300/j018v29n04_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perales J, Moore WT, Fernandez C, Chavez D, Ramirez M, Johnson D, Resendez J, Bueno C, Vidoni ED. Feasibility of an Alzheimer's disease knowledge intervention in the Latino community. Ethn Health. 2020 Jul 18;25(5):747–58. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1439899. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29457466 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monahan DJ, Greene VL, Coleman PD. Caregiver support groups: factors affecting use of services. Soc Work. 1992 May;37(3):254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharlach AE, Giunta N, Chow JC, Lehning A. Racial and ethnic variations in caregiver service use. J Aging Health. 2008 Apr 01;20(3):326–46. doi: 10.1177/0898264308315426.20/3/326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goal F: understand health disparities related to aging and develop strategies to improve the health status of older adults in diverse populations. National Institute on Aging. [2022-04-19]. https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/aging-strategic-directions-research/goal-health-disparities-adults .

- 26.Grossman MR, Zak DK, Zelinski EM. Mobile apps for caregivers of older adults: quantitative content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Jul 30;6(7):e162. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9345. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/7/e162/ v6i7e162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waller A, Dilworth S, Mansfield E, Sanson-Fisher R. Computer and telephone delivered interventions to support caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review of research output and quality. BMC Geriatr. 2017 Nov 16;17(1):265. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0654-6. https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-017-0654-6 .10.1186/s12877-017-0654-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, Humber MB, Thompson LW. Helping hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018 Dec 13;41(3):209–16. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1377797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson M. Technology device ownership: 2015. Pew Research Center. [2022-04-19]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/10/29/technology-device-ownership-2015/

- 30.Cartujano-Barrera F, Sanderson Cox L, Arana-Chicas E, Ramírez M, Perales-Puchalt J, Valera P, Díaz FJ, Catley D, Ellerbeck EF, Cupertino AP. Feasibility and acceptability of a culturally- and linguistically-adapted smoking cessation text messaging intervention for Latino smokers. Front Public Health. 2020 Jun 30;8:269. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00269. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mobile fact sheet. Pew Research Center. 2021. [2022-04-19]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 32.Text messaging in healthcare research toolkit. University of Colorado School of Medicine. [2022-04-19]. https://www.careinnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Text_Messaging_in_Healthcare_Research_Toolkit_2.pdf .

- 33.Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015 Mar 18;36:393–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122855. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25785892 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerriero C, Cairns J, Roberts I, Rodgers A, Whittaker R, Free C. The cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation support delivered by mobile phone text messaging: Txt2stop. Eur J Health Econ. 2013 Oct 9;14(5):789–97. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0424-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22961230 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zurovac D, Larson BA, Sudoi RK, Snow RW. Costs and cost-effectiveness of a mobile phone text-message reminder programmes to improve health workers' adherence to malaria guidelines in Kenya. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052045. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052045 .PONE-D-12-30752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lincoln KD, Chow TW, Gaines BF. BrainWorks: a comparative effectiveness trial to examine Alzheimer's disease education for community-dwelling African Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;27(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.09.010.S1064-7481(18)30487-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014 Jan 01;2(1):22–34. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497932. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25821658 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ISO 9241-210:2010 Ergonomics of human-system interaction — Part 210: human-centred design for interactive systems. International Organization for Standardization. [2022-04-19]. https://www.iso.org/standard/52075.html .

- 39.Creswell J, Clark V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2006. pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilardaga R, Rizo J, Zeng E, Kientz JA, Ries R, Otis C, Hernandez K. User-centered design of learn to quit, a smoking cessation smartphone app for people with serious mental illness. JMIR Serious Games. 2018 Jan 16;6(1):e2. doi: 10.2196/games.8881. https://games.jmir.org/2018/1/e2/ v6i1e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bandura A. Recent Trends in Social Learning Theory. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1972. Modeling theoryome traditions, trends, and disputes; pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontol. 1990 Oct 01;30(5):583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knowles M, Gould E. Grantee-implemented evidence-based and evidence-informed dementia interventions: prepared by the National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center for the U.S. Administration on Aging. National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center for the U.S. Administration on Aging. 2019. [2022-04-19]. https://www.rti.org/publication/grantee-implemented-evidence-based-and-evidence-informed-dementia-interventions .

- 44.Hilgeman MM, Durkin DW, Sun F, DeCoster J, Allen RS, Gallagher-Thompson D, Burgio LD. Testing a theoretical model of the stress process in Alzheimer's caregivers with race as a moderator. Gerontologist. 2009 Apr;49(2):248–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp015. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19363019 .gnp015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang M, Hinton L, Alvarez P, Rengifo J, Valverde I, Chen N, Emrani T, Thompson LW. Effectiveness of a fotonovela for reducing depression and stress in Latino dementia family caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(2):146–53. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000077. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25590939 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitzpatrick KK, Darcy A, Vierhile M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2017 Jun 06;4(2):e19. doi: 10.2196/mental.7785. https://mental.jmir.org/2017/2/e19/ v4i2e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerra M, Ferri CP, Fonseca M, Banerjee S, Prince M. Helping carers to care: the 10/66 dementia research group's randomized control trial of a caregiver intervention in Peru. Braz J Psychiatry. 2011 Mar 02;33(1):47–54. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010005000017. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-44462010005000017&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en .S1516-44462010005000017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, McCormick W, Larson EB. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003 Oct 15;290(15):2015–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2015.290/15/2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gitlin L, Piersol C. A Caregiver's Guide to Dementia Using Activities and Other Strategies to Prevent, Reduce and Manage Behavioral Symptoms. Philadelphia, United States: Camino Books; 2014. pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumel A, Tinkelman A, Mathur N, Kane JM. Digital peer-support platform (7Cups) as an adjunct treatment for women with postpartum depression: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Feb 13;6(2):e38. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9482. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/2/e38/ v6i2e38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baruah U, Varghese M, Loganathan S, Mehta KM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Zandi D, Dua T, Pot AM. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of an online training and support program for caregivers of people with dementia in India: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021 Apr 08;36(4):606–17. doi: 10.1002/gps.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, Bonasera SJ, Chiong W, Lee K, Hooper SM, Allen IE, Braley T, Bernstein A, Rosa TD, Harrison K, Begert-Hellings H, Kornak J, Kahn JG, Naasan G, Lanata S, Clark AM, Chodos A, Gearhart R, Ritchie C, Miller BL. Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the care ecosystem randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Dec 01;179(12):1658–67. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4101. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31566651 .2751946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Institute on Aging. [2022-04-19]. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers .

- 54.Family Caregiver Alliance homepage. Family Caregiver Alliance. [2022-04-19]. https://www.caregiver.org/

- 55.Alzheimer's Association homepage. Alzheimer's Association. [2022-04-19]. https://www.alz.org/

- 56.Llanque SM, Enriquez M. Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: a review of the literature. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012 Feb 30;27(1):23–32. doi: 10.1177/1533317512439794. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1533317512439794?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .27/1/23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonyea JG, López LM, Velásquez EH. The effectiveness of a culturally sensitive cognitive behavioral group intervention for Latino Alzheimer's caregivers. Gerontologist. 2016 Apr 22;56(2):292–302. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu045. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24855313 .gnu045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parra-Vidales E, Soto-Pérez F, Perea-Bartolomé MV, Franco-Martín MA, Muñoz-Sánchez JL. Online interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2017 May;45(3):116–26. https://www.actaspsiquiatria.es/repositorio//19/107/ENG/19-107-ENG-116-26-887591.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cartujano-Barrera F, Arana-Chicas E, Ramírez-Mantilla M, Perales J, Cox LS, Ellerbeck EF, Catley D, Cupertino AP. “Every day I think about your messages”: assessing text messaging engagement among Latino smokers in a mobile cessation program. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019 Jul;Volume 13:1213–9. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s209547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cupertino AP, Cartujano-Barrera F, Perales J, Formagini T, Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Ellerbeck EF, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Reynales-Shigematsu LM. Feasibility and acceptability of an e-health smoking cessation informed decision-making tool integrated in primary healthcare in Mexico. Telemed J E Health. 2019 May;25(5):425–31. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0299. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30048208 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basch CE. Focus group interview: an underutilized research technique for improving theory and practice in health education. Health Educ Q. 1987 Sep 04;14(4):411–48. doi: 10.1177/109019818701400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 1984. pp. 1–263. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009 Jul 16;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 .1471-2288-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research. Piscataway, New Jersey: Aldine Transaction; 1967. pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cutlip S, Center CH. Effective Public Relations Pathways to Public Favor. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: Prentice-Hall; 1952. pp. 166–168. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sureka B, Garg P, Khera PS. Seven C's of effective communication. Am J Roentgenol. 2018 May;210(5):W243. doi: 10.2214/ajr.17.19269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aggarwal V, Gupta V. Handbook of Journalism and Mass Communication. New Delhi, India: Concept; 2001. pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buxton B, Buxton W. Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2010. pp. 25–400. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cooper A, Reimann R, Cronin D. About Face 3 The Essentials of Interaction Design. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. pp. 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielson J, Landauer TK. A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems. Proceedings of the INTERACT '93 and CHI '93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; INTERCHI93: Conference on Human Factors in Computing; Apr 24 - 29, 1993; Amsterdam The Netherlands. 1993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, Miller JP, Storandt M, Morris JC. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005 Aug 23;65(4):559–64. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a.65/4/559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carnero Pardo C, de la Vega Cotarelo R, López Alcalde S, Martos Aparicio C, Vílchez Carrillo R, Mora Gavilán E, Galvin J. Assessing the diagnostic accuracy (DA) of the Spanish version of the informant-based AD8 questionnaire. Neurologia. 2013 Mar;28(2):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2012.03.012. http://www.elsevier.es/en/linksolver/ft/pii/S0213-4853(12)00082-5 .S0213-4853(12)00082-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sauro J. A Practical Guide to the System Usability Scale: Background, Benchmarks & Best Practices. California, US: Createspace Independent Publishing; 2011. pp. 11–51. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubin J, Chisnell D. Handbook of Usability Testing How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- 75.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. pp. 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chodosh J, Colaiaco BA, Connor KI, Cope DW, Liu H, Ganz DA, Richman MJ, Cherry DL, Blank JM, Carbone RD, Wolf SM, Vickrey BG. Dementia care management in an underserved community: the comparative effectiveness of two different approaches. J Aging Health. 2015 Aug;27(5):864–93. doi: 10.1177/0898264315569454.0898264315569454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Butler M, Gaugler J, Talley K, Abdi HI, Desai PJ, Duval S, Forte ML, Nelson VA, W N, Ouellette JM, Ratner E, Saha J, Shippee T, Wagner BL, Wilt TJ, Yeshi L. Care Interventions for People Living With Dementia and Their Caregivers. Rockville, MD: Effective Health Care Program, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Areán P. Recruitment and retention of latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist. 2003 Feb 01;43(1):45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Apesoa-Varano E, Tang-Feldman Y, Reinhard S, Choula R, Young H. Multi-cultural caregiving and caregiver interventions: a look back and a call for future action. Generations. 2015;39(4):39–48. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1764312946?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=z0Uz9maV3vS68qCNNp88yUSuAjmTedpETpixp8M0Fdo%3D . [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021. pp. 163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gaugler JE, Gitlin LN, Zimmerman S. Aligning dementia care science with the urgent need for dissemination and implementation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 Oct;22(10):2036–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.08.026. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34579933 .S1525-8610(21)00765-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sample usability testing interview.