Abstract

BACKGROUND

Mesh plug (MP) erosion into the intra-abdominal organs is a rare but serious long-term complication after inguinal hernia repair (IHR), and may lead to aggravation of symptoms if not treated promptly. It is difficult to diagnose MP erosion as there are no obvious specific clinical manifestations, and surgery is often needed for confirmation. In recent years, with the increased understanding of postoperative complications, MP eroding into the intra-abdominal organs has been a cause for concern among surgeons.

CASE SUMMARY

A 50-year-old man was referred to the Department of General Surgery with the complaint of abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant for 2 d. He had a surgical history of right open IHR and partial thyroidectomy performed 20 years and 15 years ago, respectively. Computed tomography revealed a circinate high-density image with short segmental thickening of the ileum stuck to the abdominal wall, and no evidence of recurrent inguinal hernia. Laparoscopic abdominal exploration confirmed adhesion of the middle segmental portion of the ileal loop to the right inguinal abdominal wall; the rest of the small intestine was normal. Further exploration revealed migration of the polypropylene MP into the intraperitoneal cavity and formation of granulation tissue around the plug, which eroded the ileum. Partial resection of the ileum, including the MP and end-to-side anastomosis with an anastomat, was performed.

CONCLUSION

Surgeons should aim to improve their ability to predict patients at high risk for MP erosion after IHR.

Keywords: Mesh plug, Inguinal hernia repair, Migration, Erosion, Complication, Case report

Core Tip: Mesh plug (MP) erosion into the intra-abdominal organs is a rare but serious long-term complication after inguinal hernia repair. We report a rare case of MP erosion into the small intestine to improve surgeons’ knowledge regarding this complication. MP erosion should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with a history of inguinal hernia repair who present with abdominal pain and the need for longer follow-up to detect MP erosion. When MP erosion is diagnosed, the most effective treatment is removal of the mesh and resection or repair of the involved organs.

INTRODUCTION

In 1974, Lichtenstein reported using a piece of mesh rolled into a cylindrical shape to form a plug for the repair of femoral and recurrent inguinal hernias[1]. Gilbert changed the shape of the mesh plug (MP) into an umbrella or a cone to keep the MP fixed to the anterior abdominal wall to prevent slippage. In 1989, Rutkow repaired a Gilbert type III hernia on the basis of Gilbert’s approach by discontinuous suture of the MP fixed to the edge of a dilated internal ring. Inguinal hernia repair (IHR) using an MP reduced the recurrence rate to 0.1% and became one of the most widely used approaches for IHR[2]. However, as the implanted MP is a foreign body, it is prone to infection, degeneration, shrinkage, migration, and erosion[3-5].

Mesh erosion is a term frequently used in the literature to describe any invasion of an organ by an entire or partial piece of mesh[3]. The sigmoid colon, urinary bladder and small bowel are the three most common sites of erosion. Rectal bleeding, colocutaneous fistula and sigmoiditis are the most frequent clinical indicators of digestive tract involvement; recurrent urinary tract infection and hematuria represent the most common symptoms of mesh-related bladder complications[5]. In recent years, with the increased understanding of postoperative complications, MP erosion into the intra-abdominal organs has been a cause for concern among surgeons. Herein, we report a rare case of MP erosion into the small intestine to improve the knowledge of surgeons regarding this complication.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 50-year-old man (BMI of 24.3 kg/m2) was referred to the Department of General Surgery in January 2021 with the complaint of abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms started 2 d previously with abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant, which had worsened in the last 2 h.

History of past illness

He had a surgical history of right open IHR and partial thyroidectomy performed 20 years and 15 years ago, respectively.

Personal and family history

He performed light work and did not smoke.

Physical examination

Physical examination showed only tenderness in the right lower abdomen near the groin. There were no signs of peritonitis or reports of vomiting and fever.

Laboratory examinations

The laboratory examinations included assessment of tumor markers (alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen [CA] 125, CA15-3, CA19-9, and CA72-4); routine tests for blood and urine biochemistry; and stool tests. All test results were normal.

Imaging examinations

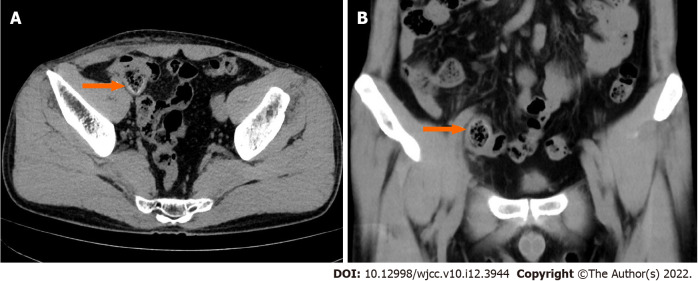

Ultrasonography identified a locally discontinuous band of strong echo in the abdominal wall of the right inguinal area. An inhomogeneous echo mass (dimensions: 3.9 cm × 1.5 cm) was detected on its deep surface (Figure 1). A weak blood flow signal was detected within the mass via color Doppler flow imaging. Computed tomography revealed a circinate high-density image with a short segmental thickening of the ileum stuck to the abdominal wall, and no evidence of recurrent inguinal hernia (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography identified a locally discontinuous band of strong echo in the abdominal wall of the right inguinal area. An inhomogeneous echo mass (dimensions: 3.9 cm ×1.5 cm) was detected on its deep surface.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography revealed a circinate high-density image with short segmental thickening of the ileum stuck to the abdominal wall (orange arrow) with no evidence of recurrent inguinal hernia.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

MP erosion into the small intestine was diagnosed based on the reported clinical symptoms, laparoscopic abdominal exploration and postoperative pathology.

TREATMENT

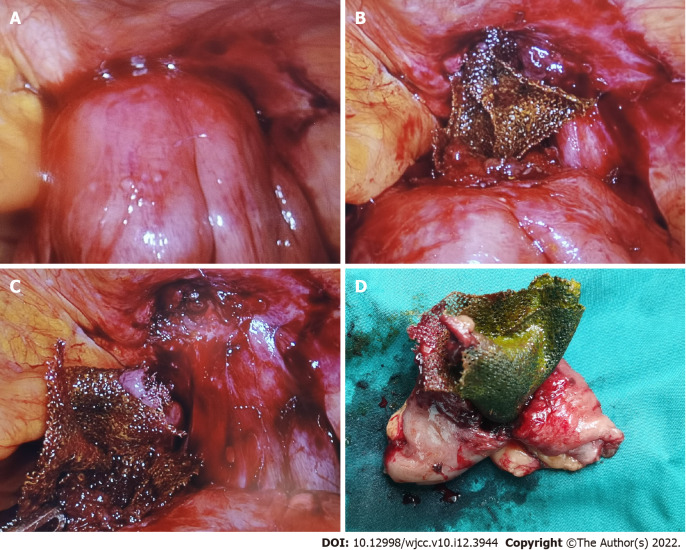

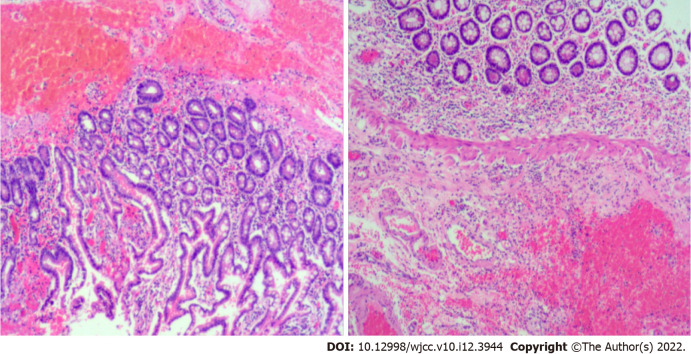

Laparoscopic abdominal exploration confirmed adhesion of the middle segmental portion of the ileal loop to the right inguinal abdominal wall (Figure 3A); the rest of the small intestine was normal. Further exploration revealed migration of the polypropylene MP into the intraperitoneal cavity and formation of granulation tissue around the plug, which eroded the ileum (Figure 3B). The internal ring was 1.0 cm in diameter, but no hernia sac was found (Figure 3C). There was no leakage of intestinal fluid at the site of erosion, thus we did not consider that there was a perforation of the intestine. Based on the findings of the preoperative ultrasound, we considered the MP method used previously to be responsible for the patient’s current complaints and complications. The flat mesh was in the correct position and did not need to be removed. Partial resection of the ileum, including the MP and end-to-side anastomosis with an anastomat, was performed. The dilated internal ring was repaired by a direct continuous suture of the surrounding peritoneum. Specimen examination revealed erosion of the iliac wall from the MP (Figure 3D). Postoperative pathology showed chronic inflammatory changes in the mucosa of the small intestine, with focal granulomatous tissue formation and focal abscess in the serosa (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

During surgery. A: Adhesion of the ileum loop to the right inguinal abdominal wall; B: Migration of the polypropylene mesh plug (MP) into the intra-peritoneal cavity; C: The internal ring was 1.0 cm in diameter, but no hernia sac was found; D: Specimen examination revealed erosion of the iliac wall due to the MP.

Figure 4.

Postoperative pathology showed chronic inflammatory changes in the small intestine mucosa, with focal granulomatous tissue formation, and focal abscess in the serosa.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The postoperative course of the patient was uneventful, and he was well at the 6-mo follow-up. There was no evidence of relapse of postoperative hernia.

DISCUSSION

MP erosion into the intra-abdominal organs is a rare but serious long-term complication after IHR that can lead to aggravation of symptoms if not treated promptly. In a review of the literature from 2000 to 2021, 19 cases of complications related to MP erosion into the intestines were reported (Supplementary Table 1). In this case, MP erosion could have led to small bowel perforation without immediate intervention and was life-threatening.

The timescale from previous IHR to the appearance of clinical symptoms (time to event) was from 10 days to 26 years, with a median of 6.3 years[5]. Given the long time since the previous surgery, patients typically tend to go to a different hospital than the one where they first underwent IHR. This could explain why the follow-up data in previous studies only considered factors such as hernia recurrence, chronic pain, and foreign body sensation and not long-term complications. The clinical presentation is not a characteristic of MP erosion, which makes it difficult to relate to the previous IHR, and the follow-up evaluation may neglect these details and consider it another new disease. MP erosion may be found more frequently in some large centers than reported in the literature, but because of medical-legal issues and authors' indifference or lack of awareness, the true rate could be underestimated.

MP erosion is often accompanied by MP migration. As described by Agrawal et al[6], mesh migration after IHR may be classified primarily as mechanical or secondarily due to the erosion of surrounding tissue. Primary mechanical migration mainly refers to the displacement of the MP along the original anatomical space that offers the least resistance and is likely caused by inadequate fixation or external displacing forces. Secondary migration refers to the adjacent or distant migration of tissue structure across anatomical levels owing to the erosion and destruction of tissue structure caused by foreign body reaction between the MP and tissue.

It is still unclear whether a relationship exists between MP migration and the method used to fix the mesh. However, many studies have shown that there is no difference in hernia recurrence between fixed and unfixed mesh in either open or endoscopic surgery[7]. Unfortunately, most of the literature on MP migration did not describe the fixation method during anterior IHR. Therefore, we could not infer its effect on MP migration. Perhaps, future reports focusing on this aspect will help to understand this phenomenon.

In terms of the time to event, the complication in this case occurred 20 years after IHR, which shows that MP erosion is a long-term and chronic process. Based on anatomical considerations, a left-sided MP is more likely to involve the sigmoid colon, while a right-sided MP more frequently involves the small intestine or cecum. The three most vulnerable organs are the sigmoid colon, small intestine, and bladder. The clinical manifestations of an eroded sigmoid colon are hematochezia, colocutaneous fistula, and abdominal pain; of an eroded small intestine is intestinal obstruction[8]; and of an eroded bladder is hematuria[5].

We believe that the possible causes of our patient’s complication are as follows: (1) The peritoneum was damaged during the intraoperative separation of the preperitoneal space or the hernia sac, without defects of the peritoneum being detected, and the MP adhered to the internal organs through the peritoneum; (2) Even if the peritoneum was intact, the conical design of the MP and long-term direct contact with the peritoneum could have easily caused peritoneal erosion; and (3) Polypropylene developed significantly more adhesions[9], and erosion was related to the production process of the MP and the static pressure between the MP and tissue[10].

To avoid MP erosion, attention should be given to the following aspects: (1) The integrity of the peritoneum should be maintained when separating the hernia sac and preperitoneal space, if a peritoneal defect is found, the defect should be repaired immediately; and (2) The MP should fit the hernia ring. If it is too small, the effectiveness of the IHR is not guaranteed. In contrast, if the MP is too large and the hernia sac is relatively small, this can lead to excessive tension between the MP and surrounding tissue, in which case MP erosion into the peritoneum may be exacerbated. To prevent this, the MP should be properly trimmed to ensure that it has a certain degree of mobility.

Removal of the mesh and resection or repair of the involved organs were required in 96% of cases of MP erosion[5]. Is there a recurrence of IHR after MP removal? A previous study showed that there were more fibroblasts and scar tissue in the area around the mesh due to inflammatory intervention and fibroblast immersion[11]. If there is sufficient fibrous scar tissue, the hernia is unlikely to recur.

CONCLUSION

MP erosion is a rare and long-term complication of IHR that can cause severe problems. It is difficult to diagnose MP erosion because there are no obvious specific clinical manifestations, and surgery is often needed for confirmation. MP erosion should also be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with a history of inguinal hernia repair who present with abdominal pain and the need for longer follow-up to detect MP erosion. Surgeons should aim to reduce the risk of such complications and improve their awareness of and ability to predict patients at high risk for MP erosion after IHR. The selection of appropriate repair materials, standardized surgical procedures, and maintenance of peritoneal integrity are important ways to prevent MP erosion. When MP erosion into the small intestine and intra-abdominal organs is diagnosed, the most effective treatment is removal of the mesh and resection or repair of the involved organs.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written consent for publication was acquired from the patient, and the signed consent will be provided upon request.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 21, 2021

First decision: December 17, 2021

Article in press: March 6, 2022

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akbulut S, Turkey; Yap RV, Philippines S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Tian-Hao Xie, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Qiang Wang, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Si-Ning Ha, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Shu-Jie Cheng, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Zheng Niu, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Xiang-Xiang Ren, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Qian Sun, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China.

Xiao-Shi Jin, Department of General Surgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding 071000, Hebei Province, China. doctorjinxiaoshi@126.com.

References

- 1.Lichtenstein IL, Shore JM. Simplified repair of femoral and recurrent inguinal hernias by a "plug" technic. Am J Surg. 1974;128:439–444. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(74)90189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robbins AW, Rutkow IM. The Mesh-Plug Hernioplasty. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1993;73:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham HB, Weis JJ, Taveras LR, Huerta S. Mesh migration following abdominal hernia repair: a comprehensive review. Hernia. 2019;23:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Cheng T. Mesh erosion into urinary bladder, rare condition but important to know. Hernia. 2019;23:709–716. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gossetti F, D'Amore L, Annesi E, Bruzzone P, Bambi L, Grimaldi MR, Ceci F, Negro P. Mesh-related visceral complications following inguinal hernia repair: an emerging topic. Hernia. 2019;23:699–708. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01905-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal A, Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HerniaSurge G. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie TH, Fu Y, Ren XX, Zhang J. Incarcerated hernia of the hypogastric linea alba accompanied by intestinal obstruction. Asian J Surg. 2020;43:870–871. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews BD, Pratt BL, Pollinger HS. Assessment of adhesion formation to intra-abdominal polypropylene mesh and polytetrafluoroethylene mesh. J Surg Res. 2003;114:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt A, Taylor D. Erosion of soft tissue by polypropylene mesh products. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;115:104281. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akyol C, Kocaay F, Orozakunov E. Outcome of the patients with chronic mesh infection following open inguinal hernia repair. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:287–291. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.84.5.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]