Abstract

It is frequently assumed that populations of genetically modified microorganisms will perform their intended function and then disappear from the environment due to inherent fitness disadvantages resulting from their genetic alteration. However, modified organisms used in bioremediation can be expected to adapt evolutionarily to growth on the anthropogenic substrate that they are intended to degrade. If such adaptation results in improved competitiveness for alternative, naturally occurring substrates, then this will increase the likelihood that the modified organisms will persist in the environment. In this study, bacteria capable of degrading the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) were used to test the effects of evolutionary adaptation to one substrate on fitness during growth on an alternative substrate. Twenty lineages of bacteria were allowed to evolve under abundant resource conditions on either 2,4-D or succinate as their sole carbon source. The competitiveness of each evolved line was then measured relative to that of its ancestor for growth on both substrates. Only three derived lines showed a clear drop in fitness on the alternative substrate after demonstrable adaptation to their selective substrate, while five derived lines showed significant simultaneous increases in fitness on both their selective and alternative substrates. These data demonstrate that adaptation to an anthropogenic substrate can pleiotropically increase competitiveness for an alternative natural substrate and therefore increase the likelihood that a genetically modified organism will persist in the environment.

Biological traits that are not important components of fitness in a particular environment may nonetheless evolve by a variety of mechanisms. Such mechanisms include pleiotropic side effects of adaptive mutations on unselected traits (43), the random fixation of effectively neutral alleles by genetic drift (19), and “hitchhiking” of neutral mutations due to genetic linkage with an adaptive mutation (16, 31). Along with adaptation by natural selection, these more indirect mechanisms of evolution are relevant to such issues as the genetic divergence of populations within a species (8, 43) and the fate of genetically modified organisms in natural environments (25, 36, 37, 40).

Several studies have shown that isolated populations of the same species may evolve different adaptations even to the same selective conditions. Some of the clearest evidence for this phenomenon comes from laboratory experiments using fruitflies (9, 18) and bacteria (42, 43). Alternative pathways of adaptation to a particular selective environment may lead to heterogeneous changes in traits that are not important for fitness in that environment. For example, several populations of organisms that are under selective pressure to use a particular substrate more efficiently may each find a different physiological mechanism to do so. The effects of these different adaptations on the ability of organisms to use some alternative substrate may be positive in some cases, neutral in others, and negative in yet others. As a consequence of these different correlated responses, some populations may be fortuitously well adapted and others may be poorly adapted to environments that contain this alternative substrate.

Of particular relevance to these concerns is the effect that evolutionary adaptation by bioremediative organisms to their intended anthropogenic substrate has on their abilities to grow on, and compete for, naturally occurring substrates. If adaptation to an anthropogenic substrate always leads to a reduction in fitness on natural substrates, then this reduced fitness provides a measure of safety for the release of organisms modified for bioremediation. If, however, such adaptation indirectly enhances fitness on natural substrates, then this enhanced fitness increases the likelihood that the released organisms (and any adverse effects they may cause) will persist in the environment.

In this study, evolving populations of bacteria were used to investigate the effect of adaptation to one carbon source on competitive performance on an alternative substrate. The bacterial strains employed were two natural isolates of the β-proteobacteria (genus Burkholderia), each capable of degrading the anthropogenic herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (32, 41). Experimental evolution occurred in two separate stages, one in which succinate was the sole carbon source and one in which 2,4-D was the limiting substrate (Fig. 1). This two-stage design was employed to allow a period during which any major adaptations to general selective conditions other than the carbon substrate could occur (stage I on succinate) prior to subsequent evolution on the selective substrate of primary interest, 2,4-D. Allowing any such general adaptation first should maximize the degree of substrate-specific adaptation on 2,4-D. Previous evolution experiments also using 2,4-D-degrading bacteria have been conducted to investigate the role of environmental structure in adaptation and the genetic divergence of multiple populations evolving independently in identical habitats (21, 22, 23).

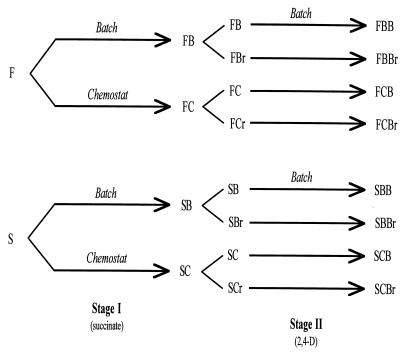

FIG. 1.

Derivation of bacterial strains. Horizontal lines indicate periods of evolution, with the selective regimen and sole carbon source indicated above and below, respectively. Each horizontal line represents two independently evolved replicate populations. F and S represent the fast and slow ancestral strains, respectively. For stage I-derived strains, the first letter (F or S) indicates the ancestor and the second letter (B or C) indicates whether stage I evolution occurred in batch (B) or chemostat (C) cultures. The letter r indicates streptomycin resistance (see Materials and Methods). The first two letters for stage II evolution strains indicate their stage I-proximate ancestor, and the third letter (B) indicates stage II evolution in batch culture.

In stage I of the experimental evolution, two ancestral strains were used to found replicate lines that were propagated in batch culture with succinate (a naturally occurring substrate) as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1). One of these strains (strain F) grows relatively fast under laboratory conditions, whereas the other (strain S) grows more slowly (42). In stage II of the evolution experiment, clonal isolates derived from the stage I batch culture lines were used to found replicate lines that were further propagated in batch culture with 2,4-D as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1). Additional stage II batch lines were founded with clones from stage I lines that had undergone evolution in a different selective regimen, chemostat culture (45). (These stage I lines were also involved in a sibling study of the effects of adaptation to either batch culture [an abundant-resource regimen] or chemostat culture [a scarce-resource regimen] on fitness in the alternative selective regimen) (45). The competitive performances of all of these derived lines were then measured relative to those of their immediate ancestors on both succinate and 2,4-D. The results of these experiments demonstrated that adaptation to either substrate can be associated with both improvements and losses in competitive performance on the alternative substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

For simplicity, the designations of the two ancestral strains in this study were changed from those used in previous literature (strain F was TFD3, and strain S was TFD20), in which their 2,4-D catabolic pathways were genetically and phylogenetically characterized (32, 41).

Evolution experiments. (i) Stage I batch evolution.

Two clones each from strains F and S were inoculated independently into 10 ml of a mineral salts medium (45) containing 500 μg of succinate per ml and grown to stationary phase while being shaken at 120 rpm. These lines were designated FB1, FB2, SB1, and SB2, with the first and second letters indicating ancestral strain (F or S) and selective regimen (batch), respectively, and with the numbers distinguishing replicate lines (Fig. 1). The four lines were then diluted daily into fresh medium for 75 days (see Table 1 for dilution factors and numbers of generations evolved for all selection experiments). Dilution factors were set to allow complete population replacement in 24 h with minimal time spent in stationary phase. All cultures were maintained at 25°C in all experiments.

TABLE 1.

Dilution factors for batch evolution and competition experiments and numbers of generations evolved (during the most recent stage of evolution)a

| Line set | Daily dilution factor | No. of generations evolved |

|---|---|---|

| FB | 0.01 | 500 |

| SB | 0.20 | 185 |

| FBB | 0.01 | 500 |

| FCB (FCBr) | 0.01 (0.08) | 500 (275) |

| SBB | 0.20 | 175 |

| SCB | 0.33 | 120 |

Daily dilution factors and numbers of generations evolved are shown for each set of replicate lines. Dilution factors indicate the proportion of day-old cultures that were transferred daily into fresh medium (to a final volume of 10 ml). Except for the FCBr lines, values for streptomycin-resistant replicate lines within a set are identical to values for streptomycin-sensitive lines.

(ii) Stage I chemostat evolution.

Two initially clonal lines from each ancestor were also evolved in chemostats for 75 days during stage I, where fresh medium containing succinate as the sole carbon source continually flowed into culture vessels and culture volume was kept constant by continuous vacuum removal of excess culture (45). These lines were designated FC1, FC2, SC1, and SC2, where C indicates a chemostat selection history. These chemostat-evolved lines were competed against their ancestors in a different study (which tested for a trade-off between fitness at high and low substrate concentrations [45]) but not in this study. For logistical reasons, only strains that experienced the batch culture regimen during their most recent stage of evolution were competed against their ancestors in this study. Thus, the stage I chemostat-evolved strains served as the proximate ancestors for half of the stage II batch lines but not as evolved strains for analysis in their own right. Use of these strains as stage II ancestors (rather than simply initiating more replicate lines from the stage I batch clones) allowed a greater chance of detecting patterns of adaptation specific to distinct selective histories.

(iii) Stage I clones.

Single clones were isolated from each of the eight stage I evolved lines. The four batch-evolved clones (FB1, FB2, SB1, and SB2) were compared to their ancestors in competition experiments described below. In addition, a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant sister clone was selected from each of the four clones FB1, FC1, SB1, and SC1 (denoted by the letter r). Each of these eight clones (FB1, FBr, FC1, FCr, SB1, SBr, SC1, and SCr) was then used to initiate two new lines (distinguished by the numbers 1 and 2) for stage II evolution.

(iv) Stage II batch evolution.

Stage II batch lines were propagated as described above for stage I lines except that the growth medium contained 500 μg of 2,4-D per ml rather than succinate and dilution factors varied. After evolution, single clones from each line were isolated for use in competition experiments. Stage II clones were named by adding the letter B to the name of their stage I-proximate ancestor, indicating stage II evolution in batch culture (Fig. 1; Table 2). All strains were stored in medium containing 10% glycerol at −80°C. The identity of each clone as a true evolved descendant of the founding clone (rather than as a contaminant) was confirmed both by streptomycin marker type and by repetitive-extragenic-palindromic-PCR diagnostic fingerprints (46).

TABLE 2.

Results of competition experiments for evolved lines from stage I selection in succinate and stage II selection in 2,4-D

| Line | Selective substrate | SRC (per day)a on:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective substrate | Alternative substrate | ||

| FB1 | Succinate | 0.0260 | 0.0236 |

| FB2 | Succinate | 0.0910 | −4.6052* |

| SB1 | Succinate | 0.2531 | 0.0366 |

| SB2 | Succinate | 0.3759 | 0.1582 |

| FBB1 | 2,4-D | 0.4026 | −0.0929 |

| FBB2 | 2,4-D | 0.9675 | 0.0147 |

| FBBr1 | 2,4-D | 0.3116 | 0.3932 |

| FBBr2 | 2,4-D | 0.3439 | −0.8023 |

| FCB1 | 2,4-D | 0.4171 | −2.7843 |

| FCB2 | 2,4-D | 0.6390 | −1.1000 |

| FCBr1 | 2,4-D | 0.6788 | 1.9561 |

| FCBr2 | 2,4-D | −0.6600 | −0.5012 |

| SBB1 | 2,4-D | 0.0379 | −0.0287 |

| SBB2 | 2,4-D | 0.1073 | 0.1892 |

| SBBr1 | 2,4-D | 0.2230 | −0.0880 |

| SBBr2 | 2,4-D | 0.0701 | −0.0762 |

| SCB1 | 2,4-D | 0.6924 | 0.2455 |

| SCB2 | 2,4-D | 0.7670 | 0.0291 |

| SCBr1 | 2,4-D | 0.4899 | 0.4913 |

| SCBr2 | 2,4-D | 0.3680 | −1.3205 |

SRCs of evolved lines (relative to those of their appropriate ancestors) for both the substrate in which evolution occurred and the alternative substrate are presented. SRC values that are significantly different from those of the appropriate ancestor are presented in boldface type (two-tailed t test, P < 0.05). The asterisk marking strain FB2 for performance on 2,4-D indicates that the maximum SRC for FB2 on 2,4-D was inferred, rather than measured directly. The value is based on the ability of FB2’s competitor (FBr) to grow at least 100-fold per day on 2,4-D, since FB2 is unable to grow on 2,4-D.

Competition experiments.

The competitive performance of each clone that evolved in batch culture during its most recent stage of evolution was measured by directly competing a clone with its proximate ancestor of the opposite marker type. These experiments were performed on both selective and alternative substrates under the same conditions in which the clone evolved. Both strains in each pairwise competition were preconditioned for two growth cycles in the competition medium. The strains were then mixed and grown together for several generations (one to three daily dilution cycles). Initial and final relative frequencies of competing strains were estimated by dilution plating onto selective and nonselective agar plates. These frequencies were then used to calculate the selection rate constant (SRC) for each evolved clone (see below), which expresses the amount of change in competitive performance undergone by a clone relative to the competitive performance of its proximate ancestor (see reference 45 for a more detailed description of competition experiments).

Control competition experiments were also performed to factor out any effect of streptomycin resistance on competitive performance (45). For example, for comparison of a stage II strain with its stage I-proximate ancestor (e.g., FBB1 versus FB1), the stage I reciprocally marked ancestor (FBr) was competed both against its oppositely marked sister clone (FB1) and the stage II clone (FBB1). The SRC of the direct proximate ancestor relative to that of its sister clone (FB1 versus FBr) was then subtracted from the SRC of the stage II clone relative to that of its reciprocally marked ancestor (FBB1 versus FBr). This process gives the SRC for the stage II strain relative to that of its direct proximate ancestor (FBB1 versus FB1). Therefore, the SRC values shown for each evolved strain (Table 2) reflect the amount of performance change by each strain relative to the performance of its immediate proximate ancestor of the same marker type (e.g., SB1 relative to S, FCB1 relative to FC1, and FBBr2 relative to FBr2). A positive SRC indicates competitive superiority of a strain over its ancestor, whereas a negative value indicates inferiority. The SRC between two competitors, i and j, (sij) is the difference between their actualized Malthusian parameters: sij = (1/t)(ln[Ni(t)/Ni(0)] − ln[Nj(t)/Nj(0)]), where t is the number of 24-h transfer cycles in the competition, Ni(0) and Nj(0) are the initial population densities, and Ni(t) and Nj(t) are the final population densities (measured at the same point in the daily growth cycle) (see references 28, 42, and 45 for more detailed descriptions and derivations of SRCs). Each SRC value reported in Table 2 is a mean value obtained from results of multiple independent replicate competitions (usually five, but a minimum of three) performed in parallel for each strain. Ninety-five percent significance levels were determined by t tests.

RESULTS

Adaptation to selective substrate.

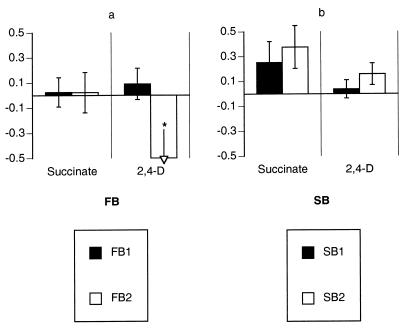

Of the stage I lines propagated on succinate in batch culture, the two S-derived lines showed significantly greater adaptation than did the two F-derived lines (Table 2; Fig. 2). Moreover, this difference is conservative, since the S-derived lines underwent fewer than half the number of doublings (185 generations) during stage I as did the F-derived lines (500 generations). This suggests that slower-growing strain S had more room for improvement in the batch regimen than did strain F.

FIG. 2.

Performance changes of stage I lines. (a) FB lines; (b) SB lines. Mean SRC values are shown, along with 95% confidence intervals, for both the selective substrate (succinate, left column) and the alternative substrate (2,4-D, right column). *, see Table 2.

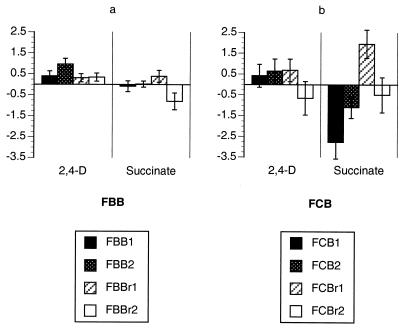

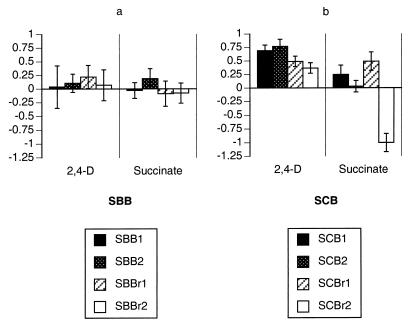

Six of the eight stage II F-derived lines significantly improved their competitiveness on 2,4-D, which was the substrate supplied during stage II (Table 2). In one set of lines (FBB) all four lines demonstrably improved (Table 2; Fig. 3). Similarly, five of the eight S-derived stage II lines show significant fitness increases (Table 2; Fig. 4). All four SCB lines (which were subjected to changes in both culture regimen and growth substrate between stages I and II) improved significantly during stage II.

FIG. 3.

Performance changes of stage II F-derived lines. (a) FBB lines; (b) FCB lines. Mean SRC values are shown, along with 95% confidence intervals, for both the selective substrate (2,4-D, left column) and the alternative substrate (succinate, right column).

FIG. 4.

Performance changes of stage II S-derived lines. (a) SBB lines; (b) SCB lines. Mean SRC values are shown, along with 95% confidence intervals, for both the selective substrate (2,4-D, left column) and the alternative substrate (succinate, right column).

Competitive performance on alternative substrate.

Among the 13 lines that showed significant improvement on their selective substrate, 5 also improved significantly on the alternative substrate (Table 3). Three additional lines had nonsignificant performance increases on the alternative substrate. In contrast, 3 of the 13 significantly adapted lines experienced significant losses of competitive ability on the alternative substrate and two others were suggestive of such losses (Table 3). Overall, 10 lines either showed or suggested correlated improvements on both substrates while 9 showed or suggested fitness losses on the alternative substrate (Table 3). Among the six sets of evolved lines, only the two SB replicate lines exhibited a homogeneous pattern of performance on both selective and alternative substrates. The other five sets showed (or suggested) both performance losses and performance gains among their lines on the alternative substrate.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of trade-off versus non-trade-off patterns of adaptation

| Adaptive pattern | No. of lines showinga:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Trade-off | Non-trade-off | |

| Significant responses in both selective and alternative regimens | 3 | 5 |

| Significant response in selective regimen only | 2 | 3 |

| Significant response in alternative regimen only | 2 | 1 |

| Significant response in neither regimen | 2 | 1 |

Substrate-specific adaptation.

The lines in this study may have increased their fitness by adaptations largely specific to their growth substrate during evolution, or alternatively, they may have improved by adapting to some other aspect of the selective regimen, such as the concentrations of various minerals in the medium. The latter possibility is especially relevant to the stage I lines. If most adaptation was not substrate specific, then evolved strains should be approximately equally superior to their ancestors on both selective and alternative substrates. In this study, however, many lines showed negative responses on their alternative substrate, indicating that their adaptation was largely substrate specific. Moreover, among those lines that improved on both substrates, in several cases the degrees of improvement were quite different for the two substrates, which also belies the general adaptation hypothesis.

DISCUSSION

Population dynamics of adaptation.

The evolutionary changes in competitive performance on nonselective substrates (resulting from adaptation to a specific selective substrate) may be caused either by pleiotropic effects of adaptive mutations (43) or by the random drift of effectively neutral alleles (19). The latter possibility can be readily dismissed with respect to these experiments. Only a very small minority of mutations that affect fitness in a given environment are expected to be beneficial rather than harmful. It is much easier to disrupt than to improve the performance of a complex entity. That is, if one considers mutations that are selectively neutral in one environment (say, 2,4-D medium) but that affect fitness in an alternative environment (say, succinate medium), then the vast majority of the mutations should reduce, rather than improve, fitness in the alternative environment.

In this study, however, a majority of lines (five of eight) that underwent significant competitive changes (positive or negative) on both their selective and alternative substrates actually improved on both substrates. This outcome is extremely unlikely under the drift hypothesis. Even after performance of a sequential Bonferroni correction (a very conservative measure that corrects both for significance attributions due to chance and for any nonindependence of data points [38]), there remained four cases in which both performance responses were significant, and these were split evenly between trade-off and non-trade-off patterns. These data indicate that improvements in the alternative substrates for most lines were not due to substitution of random mutations by drift but instead were caused by the same mutations responsible for improvements in the selective regimens. In other words, the selected mutations were often beneficial in both regimens, indicating positive pleiotropy. This being the case, it seems likely that the cases of significant performance loss on the alternative substrate (associated with significant performance improvement on the selective substrate) were also due to pleiotropy, in this case negative pleiotropy.

It is also likely that each line’s improvement in its selective environment was due to only one or a few adaptive mutations. This small number is because the duration of experimental evolution in this study was relatively short (maximum of 500 generations during either stage of evolution). Mathematical models indicate that many generations (often several hundred) are required for each beneficial mutation to sweep sequentially through a large, clonal population (28). The results of previous evolution experiments with E. coli support the predictions of these models (14, 29).

Multiple adaptive pathways.

The results of this study clearly show that replicate evolving populations often achieved adaptation to their selective substrate by different mechanisms. This inference follows from the facts that in three of the four stage II sets (each containing four independent replicate lines), at least one line showed significant correlated improvements on both the selective and the alternative substrate and that at least one other line showed a significant loss of performance on its alternative substrate after adaptation to its selective substrate (Table 2; Fig. 3 and 4). In other words, the variation in competitive fitness among replicate populations on alternative substrates (standard deviation = 1.3394) was significantly greater (F = 14.581, 38 df, P < 0.0001 [F test statistic to compare variances]) than such variation on selective substrates (standard deviation = 0.3508) (43).

Even for replicate lines within a set that showed the same pattern of performance changes on both the selective and the alternative substrate, there was sometimes additional evidence that these changes were caused by different underlying physiological mechanisms. For example, lines SCB1 and SCBr1 both adapted significantly to their selective substrate (2,4-D) and they both showed significant correlated improvements on their alternative substrate (succinate). However, data presented by Velicer and Lenski (45) suggest that one of these lines, SCB1, had improved performance in the chemostat culture regimen during adaptation to the batch regimen but that the other strain, SCBr1, appeared to have reduced performance in chemostat culture. (The difference in chemostat performance between each strain and its proximate ancestor was not significant, but the resulting difference between the two evolved strains was highly significant [t = 8.298; 8 df; two-tailed t test, P < 0.0001] [Student’s t test statistic]). Assuming that these changes in chemostat performance reflect the pleiotropic effects of mutations that were adaptive in the batch regimen, then these data imply that dual improvements of SCB1 and SCBr1 had occurred by different underlying mechanisms.

The stage I selection history of clones used to initiate stage II lines does not appear to have had a significant effect on the pattern of adaptive changes for stage II lines. Thus, among the eight stage II lines with a stage I batch history, three lines showed or suggested improvement on their alternative substrate (succinate) after stage II evolution whereas five showed or suggested performance decreases. Similarly, among stage II lines with a stage I chemostat history, four lines improved and four became worse on their stage II alternative substrate. (There were not enough line replicates during stage I evolution to test for an ancestor effect on adaptation patterns.)

The replicate lines that indicate different mechanisms of adaptation to 2,4-D in batch culture were founded from base populations that were initially isogenic. This finding corroborates the results of Travisano et al. (43), which showed that natural selection can cause significant divergence of populations within a species even when the populations are founded from the same progenitor and experience identical environments. Such divergence is presumably due to the fact that the replicate lines incur different sequences of random mutations during evolution, thus providing distinct patterns of genetic variation across populations upon which natural selection may act. Potential physiological mechanisms of adaptation have been discussed by Velicer (44).

Relevance to the adaptation of genetically modified organisms in natural habitats.

In the discussion of relative benefits and risks of releasing genetically modified organisms into nature, it has often been argued that genetically altered microorganisms will not persist because they are inherently less fit than indigenous competitors (6, 10, 11). Lenski (25) reviewed various arguments for why genetically modified organisms might theoretically be less fit than their natural counterparts, and he summarized some experiments with bacteria that bear on those arguments.

Most of the studies reviewed by Lenski (25) support the view that modified microorganisms are competitively inferior to the strains from which they are derived. Mutations that alter basic metabolic functions (20), the expression of additional functions (1, 12, 24), the carriage of accessory genetic elements (27), and the domestication of bacteria as they adapt to laboratory conditions (11, 36) all tend to decrease the fitness of modified organisms relative to that of their progenitors under natural conditions, although important exceptions to this generality exist (2, 3, 13, 17). Beyond the immediate fitness effects of genetic manipulations that occur prior to release, there is the further possibility that genetically modified organisms adapt evolutionarily to the local ecosystem in which they are released. Such postrelease adaptation seems more likely than fortuitous preadaptation prior to release, and it may lead to the indefinite persistence of modified organisms in the environment (along with any adverse effects they might cause).

Several studies, including three with bacteria in the laboratory (4, 24, 34) and one with insects in the field (33), indicate that organisms may evolve so as to mitigate the fitness costs associated with other genetic changes. In one case, a population of E. coli carried a plasmid, pACYC184, that bore genes that encoded resistance to two antibiotics but that reduced the bacterium’s fitness in the absence of antibiotic (4). These plasmid-bearing cells were then propagated in medium that contained antibiotic, in order to prevent spontaneous plasmid-free segregants from outcompeting the plasmid-bearing cells and taking over the population. After only 500 generations, the plasmid-bearing cells were, surprisingly, more fit than both their plasmid-free progenitor and their isogenic plasmid-free derivatives even in the absence of antibiotic (4, 26). In other words, evolution of a genetically modified organism in one environment (with antibiotic) led to a correlated improvement in fitness in an alternative environment (without antibiotic).

The above results point towards a second concern over the evolution of microorganisms that have been genetically modified for bioremediation in the environment. What is the effect of adaptation to an anthropogenic substrate, such as 2,4-D, on their competitive fitness for naturally occurring substrates, such as succinate? If such adaptation may have pleiotropic benefits for growth on natural substrates, then this increases the likelihood that these genetically modified organisms will persist in the environment. For example, adaptations that enhance bacterial growth on exogenous 2,4-D in the rhizosphere (5) may simultaneously improve bacterial fitness during growth on succinate, an endogenous exudate of nitrogen-fixing nodules (30). The results of this study clearly show that evolutionary adaptation of bacteria to growth on the common toxic herbicide 2,4-D often improves their competitive fitness on the natural substrate succinate. This outcome may have been facilitated by the fact that succinate and 2,4-D are catabolically linked (the 2,4-D catabolic pathway enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle via succinate). If so, a similar evolutionary scenario can be expected for bacterial adaptation to other xenobiotics that also are degraded via an intermediate compound that also occurs as a natural growth substrate.

The strains employed in this investigation were already capable of degrading 2,4-D, without genetic modification in the laboratory. However, there is no obvious reason that qualitatively similar results might not be obtained for strains that are genetically modified to degrade chlorinated aromatic compounds (or perform some other bioremediation function) more efficiently than natural strains (7, 35). In fact, such modified organisms may have even more opportunities for general improvements in their overall vigor, owing to the fitness costs associated with their modification (see above). Therefore, when considering the fate of genetically modified organisms released into the environment for bioremediation of anthropogenic substrates, it seems unrealistic to assume that these organisms will simply do their job and then disappear.

The use of environmentally important substrates increases the relevance of these results to concerns about the evolutionary adaptation of genetically modified organisms subsequent to their release in the environment. One concern is that certain environmental conditions may cause bacteria that are degrading a toxic substrate to produce an even more toxic metabolite in the process. For example, bacteria may produce highly toxic vinyl chloride during the biodegradation of tetrachloroethylene under methanogenic conditions (47). In a similar vein, genetically modified bacteria that are used to degrade some toxic compound may evolve novel degradative pathways that yield a more toxic metabolite even as they continue to degrade the intended substrate. Concerns over these and other potential adverse effects are magnified if there is a significant likelihood that the released organisms may persist indefinitely in the environment (25, 37, 40). And as the organisms adapt to the natural environment in which they were released, the likelihood that they can persist will increase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank E. Smalley for assistance with the experiments. I also thank R. Lenski, M. Travisano, A. de Visser, and an anonymous reviewer for advice and comments.

This research was funded by the NSF Center for Microbial Ecology (DEB-9120006).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews K J, Hegeman G D. Selective disadvantage of nonfunctional protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Mol Evol. 1976;8:317–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01739257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biel S W, Hartl D L. Evolution of transposons: natural selection for Tn5 in Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1983;103:581–592. doi: 10.1093/genetics/103.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blot M, Hauer B, Monnet G. The Tn5 bleomycin resistance gene confers improved survival and growth advantage on Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:595–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00285283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouma J E, Lenski R E. Evolution of a bacteria/plasmid association. Nature. 1988;335:351–352. doi: 10.1038/335351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle J J, Shann J R. Biodegradation of pheno, 2,4-DCP, 2,4-D, and 2,4,5-T in field collected rhizosphere and nonrhizosphere soils. J Environ Qual. 1995;24:782–785. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brill W J. Safety concerns and genetic engineering in agriculture. Science. 1985;227:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.11643810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhry G R, Chapalamadugu S. Biodegradation of halogenated organic compounds. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:59–79. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.59-79.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohan F M. Can uniform selection retard random genetic divergence between isolated conspecific populations? Evolution. 1984;38:495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohan F M, Graf J-D. Latitudinal cline in Drosophila melanogaster for knockdown resistance to ethanol fumes and for rates of response to selection for further resistance. Evolution. 1985;39:278–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb05666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies J. Genetic engineering: processes and products. Trends Ecol Evol. 1988;3:S7–S11. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(88)90129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis B D. Bacterial domestication: underlying assumptions. Science. 1987;235:1329–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dykhuizen D E. Selection for tryptophan auxotrophs of Escherichia coli in glucose limited chemostats as a test of the energy conservation hypothesis of evolution. Evolution. 1978;32:125–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1978.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edlin G, Tait R C, Rodriguez R L. A bacteriophage Lambda cohesive ends (cos) DNA fragment enhances the fitness of plasmid-containing bacteria growing in energy-limited chemostats. Bio/Technology. 1984;2:251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elena S F, Cooper V S, Lenski R E. Punctuated evolution caused by selection of rare beneficial mutations. Science. 1996;272:1802–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forney, L. 1997. Personal communication.

- 16.Guttman D S, Dykhuizen D E. Detecting selective sweeps in naturally occurring Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1994;138:993–1003. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartl D L, Dykhuizen D E, Miller R D, Green L, deFramond J. Transposable element IS50 improves growth rate of E. coli cells without transposition. Cell. 1983;35:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman A A, Cohan F M. Genetic divergence under uniform selection. III. Selection for knockdown resistance to ethanol in Drosophila pseudoobscura populations and their replicate lines. Heredity. 1987;58:425–433. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1987.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch A L. The protein burden of lac operon products. J Mol Evol. 1983;19:455–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02102321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korona R. Adaptation to structurally different environments. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1996;263:1665–1669. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korona R. Genetic divergence and fitness convergence under uniform selection in experimental populations of bacteria. Genetics. 1996;143:637–644. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korona R, Nakatsu C H, Forney L J, Lenski R E. Evidence for multiple adaptive peaks from populations of bacteria evolving in a structured habitat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9037–9041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenski R E. Experimental studies of pleiotropy and epistasis in Escherichia coli. I. Variation in competitive fitness among mutants resistant to virus T4. Evolution. 1988;42:425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb04149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenski R E. Evaluating the fate of genetically modified microorganisms in the environment: are they inherently less fit? Experientia. 1993;49:201–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01923527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenski, R. E. 1997. Personal communication.

- 27.Lenski R E, Bouma J E. Effects of segregation and selection on instability of plasmid pACYC184 in Escherichia coli B. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5314–5316. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5314-5316.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenski R E, Rose M R, Simpson S C, Tadler S C. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. I. Adaptation and divergence during 2,000 generations. Am Nat. 1991;138:1315–1341. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenski R E, Travisano M. Dynamics of adaptation and diversification: a 10,000 generation experiment with bacterial populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6808–6814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton D S, Blanchar R W, Blevins D G. Citrate, malate, and succinate concentration in exudates from phosphorus-sufficient and phosphorus-stressed Medicago sativa L. seedlings. Plant Physiol (Bethesda) 1987;85:315–317. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maynard-Smith J. The population genetics of bacteria. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1991;245:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGowan C. Interspecies gene transfer in the evolution of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate degrading bacteria. Ph.D. dissertation. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKenzie J A, Whitten M J, Adena M A. The effect of genetic background on the fitness of diazinon resistance genotypes of the Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina. Heredity. 1982;49:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modi R I, Adams J. Coevolution in bacteria-plasmid populations. Evolution. 1991;45:656–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb04336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos J L, Wasserfallen A, Rose K, Timmis K N. Redesigning metabolic routes: manipulation of TOL plasmid pathway for catabolism of alkylbenzoates. Science. 1987;235:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.3468623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Regal P J. The adaptive potential of genetically engineered organisms. Trends Ecol Evol. 1988;3:S36–S38. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(88)90138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regal P J. The true meaning of ‘exotic species’ as a model for genetically engineered organisms. Experientia. 1993;49:225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01923530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice W R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989;43:223–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sassanella, T. 1997. Personal communication.

- 40.Tiedje J M, Colwell R K, Grossman Y L, Hodson R, Lenski R E, Mack R N, Regal P J. The planned introduction of genetically engineered organisms: ecological considerations and recommendations. Ecology. 1989;70:298–315. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonso N L, Matheson V G, Holben W E. Polyphasic characterization of a suite of bacterial isolates capable of degrading 2,4-D. Microb Ecol. 1995;30:3–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00184510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Travisano M, Lenski R E. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. IV. Targets of selection and the specificity of adaptation. Genetics. 1996;143:15–26. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Travisano M, Vasi F, Lenski R E. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. III. Variation among replicate populations in correlated responses to novel environments. Evolution. 1995;49:189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velicer G J. Ph.D. thesis. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Velicer, G. J., and R. E. Lenski. Evolutionary tradeoffs under conditions of resource abundance and scarcity: experiments with bacteria. Ecology, in press.

- 46.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogel T M, McCarty P L. Biotransformation of tetrachloroethylene to trichloroethylene, dichloroethylene, vinyl chloride, and carbon dioxide under methanogenic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1080–1083. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.5.1080-1083.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]