Abstract

Growth inhibition of Lactococcus lactis provoked by increasing osmolarity is reversed when glycine betaine (GB) or its analogs are added to a defined medium. Lacticin 481 production increased sharply with growth medium osmolarity in the absence of osmoprotectant but remained unaffected when GB was supplied in media of increasing osmolarity.

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 produces a bacteriocin, called lacticin 481 (17), that acts in particular against the food spoilage bacterium Clostridium tyrobutyricum. The use of this lantibiotic to prevent late blowing of cheese has been previously suggested (18). Cheese making involves the growth of lactic acid bacteria in high-osmotic-strength media. Knowing the effects of environmental conditions on the relationship between the growth of the producer strain and bacteriocin production could allow the optimization of cheese making.

Thus, we investigated the physiological response of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 in salt-enriched defined medium. Under these conditions, we determined the osmoprotective effect of glycine betaine (GB) on bacterial growth and also on lacticin 481 production.

Effect of increased osmotic strength on growth of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30.

The growth of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 was assayed on chemically defined medium (CDM) (10) containing increasing concentrations of NaCl. The growth rate and the growth yield decreased with the increasing osmolarity of the medium (Table 1). Growth was abolished with NaCl contents higher than 0.5 M. In the presence of 0.4 M NaCl, both parameters were reduced by 70% of their value in the absence of NaCl. Therefore, this salt condition was used for further studies. Growth inhibition was also observed when other osmotica, such as sucrose or KCl, were used to increase the osmolarity of the medium (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Effect of NaCl concentration on growth parameters of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 on CDM

| [NaCl] (M) | Osmolality (osM · kg of H2O−1)a | Growth rate (h−1) | ODmax (570 nm)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 1.30 |

| 0.1 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 1.20 |

| 0.2 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 1.17 |

| 0.3 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.92 |

| 0.4 | 0.83 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| 0.5 | 1.01 | <0.10 | 0.15 |

Osmolality was determined by using an osmometer.

Growth yield was estimated by following turbidimetry at 570 nm; values obtained in stationary phase represent ODmax. The growth rate and ODmax are the means of triplicate determinations, and the standard deviation was less than 5%. Similar results were obtained by using KCl or sucrose to increase the osmolality of the medium.

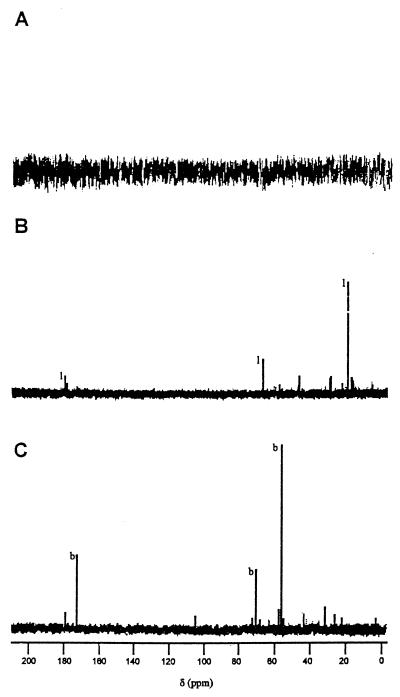

To determine the major solutes accumulated under hyperosmotic strength, cells grown on CDM alone or with 0.4 M NaCl were harvested in exponential growth phase and ethanol-soluble fractions were analyzed by natural-abundance 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (6). As expected, no major intracellular compound was accumulated in unstressed cells (Fig. 1A). In the presence of 0.4 M NaCl, the main accumulated solute was lactic acid (Fig. 1B). Lactic acid does not have the characteristics required for an osmoprotectant (2), so its accumulation could not efficiently counterbalance the osmotic pressure and was deleterious for bacterial metabolism. Thus, no accumulation of efficient osmolyte was detected by natural abundance 13C-NMR in stressed cells. This could explain the lower osmotolerance of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 compared to other strains of lactic acid bacteria (11).

FIG. 1.

Natural-abundance 13C-NMR spectra of ethanol-soluble fractions of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 grown on CDM without NaCl (A), with 0.4 M NaCl (B), and with 0.4 M NaCl added to 1 mM GB (C). The peaks were identified in comparison with reference spectra of commercial compounds: GB (b) and lactic acid (l).

Effect of compatible solutes on growth of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30.

When present in salt-containing medium, GB is efficiently accumulated by most of the lactic acid bacteria studied (4, 5, 8, 16). Therefore, GB and other compounds known to act as bacterial osmoprotectants (2) were tested on osmotically stressed cells of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 (Table 2). All of the methylated onium compounds structurally related to GB (i.e., dimethylsulfonioacetate [DMSA], dimethylsulfoniopropionate [DMSP], l-carnitine, and arsenobetaine) allowed the growth rate and the growth yield to increase by 60%. By contrast, no effect of choline, proline, or pipecolate on growth parameters was observed (Table 2). Many bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus, were able to oxidatively convert choline to GB (1, 7, 13). However, even under aerobic conditions, choline was unable to improve the growth of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Influence of osmolarity of the medium on accumulation of different osmoprotectants by L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30

| Additivea | Growth rateb (h−1)

|

Accumulation levelb (μmol · g [dry weight]−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 M NaCl | 0.4 M NaCl | 0 M NaCl | 0.4 M NaCl | |

| None | 0.33 | 0.10 | ||

| GB | 0.33 | 0.25 | 35 | 560 |

| DMSA | 0.33 | 0.25 | 20 | 420 |

| DMSP | 0.33 | 0.25 | 35 | 620 |

| l-Carnitine | 0.33 | 0.25 | 30 | 500 |

| Choline | 0.33 | 0.10 | 10 | 30 |

| Proline | 0.33 | 0.10 | 20 | 120 |

| Pipecolate | 0.33 | 0.10 | 25 | 180 |

Each osmoprotectant was added to CDM at a final concentration of 1 mM, as previously described (6).

Values are means of triplicate determinations; standard deviation was less than 20%. Similar results were obtained by using KCl or sucrose to increase the osmolality of the medium.

13C-NMR experiments were performed on cells grown in 0.4 M NaCl CDM supplemented with 1 mM GB. GB was the main solute observed on the spectrum (Fig. 1C), whereas lactate accumulation was abolished. The maximum accumulation levels of osmoprotectants were measured with and without 0.4 M NaCl. In salt-containing medium, bacteria were able to transport GB, DMSA, DMSP, l-carnitine, choline, proline, and pipecolate. The accumulation levels were correlated with the efficiencies of the osmoprotectants at improving growth (Table 2). Presumably, the structures of the osmoprotectants could play a role in their efficient uptake and accumulation. This hypothesis was previously suggested to account for the efficiency of choline transport by S. aureus (9) and for l-carnitine accumulation by Lactobacillus plantarum (12). Thus, GB and its analogs were accumulated at elevated levels in stressing medium, restablishing a positive turgor pressure, which is one of the effects usually attributed to osmoprotectants (2).

Effect of NaCl and GB on lacticin 481 production.

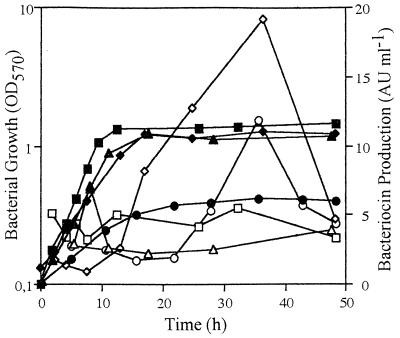

We evaluated bacteriocin production by cells grown on CDM with and without NaCl. Lacticin 481 was obtained as previously described and assayed against the indicator strain L. lactis IL1837 (15, 17). In CDM without NaCl, bacteriocin production remained constant during all stages of growth and did not exceed 5 arbitrary units (AU) ml−1 (Fig. 2). When NaCl was supplied, production increased from the beginning of stationary phase, reaching a maximal value of 20 and 12 AU ml−1 in the presence of 0.2 and 0.4 M NaCl, respectively (Fig. 2). In all conditions, a decrease of bacteriocin production was observed in late stationary phase. Proteolytic activity was assayed (3) but was not detected. This result was in agreement with the fact that no decrease of optical density at 570 nm (OD570) was observed in stationary phase (Fig. 2), indicating that no cells lysis occurred. Thus, this decline could not be due to proteolytic enzymes released during cell lysis. The adsorption of bacteriocin to producer cells was also assayed (19) and was detected. This phenomenon would explain the decline of lacticin 481 production, as was described for amylovorin L471 (3).

FIG. 2.

Effect of NaCl and GB on lacticin 481 production during the growth of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30. Cells were cultivated at 30°C without shaking on CDM with increasing NaCl concentrations or with 0.4 M NaCl added to 1 mM GB. Turbidimetry was monitored at 570 nm, and bacteriocin production (expressed in arbitrary units per milliliter) was evaluated. To quantify lacticin 481, twofold dilutions of produced bacteriocin were assayed by the supernatant diffusion method (15). The supernatants were dialyzed against CDM without NaCl and concentrated against solid polyethylene glycol 8000 for 48 h at 4°C in dialysis membranes with a molecular mass cutoff of 500 Da. The values are the means of triplicate experiments; the standard deviation was less than 20%. The solid symbols represent bacterial growth for each condition, and the open symbols represent bacteriocin production. Square, 0 M NaCl; diamond, 0.2 M NaCl; circle, 0.4 M NaCl; triangle, 0.4 M NaCl with 1 mM GB.

When 1 mM GB was added to CDM containing 0.4 M NaCl, lacticin 481 production was close to that obtained on nonstressing CDM (Fig. 2). The decrease could be explained by GB accumulation, which would allow a positive turgor pressure to be reestablished and would protect intracellular macromolecules (2). Thus, the failure of turgor or the alteration of macromolecules could be the inducers of bacteriocin production. This suggestion is supported by the results obtained with amylovorin L471, which demonstrated that unfavorable growth conditions stimulated bacteriocin production (3).

In this study, we demonstrated that GB improves the growth parameters of L. lactis ADRIA 85LO30 under hyperosmotic constraints but provokes the decrease of bacteriocin production. Also, as with nisin Z production by L. lactis I0-1 (14), optimal conditions for growth seem to be quite different from those for lacticin 481 production. Therefore, to improve bacteriocin production, it is important to know the differential effects of environmental factors on L. lactis growth and bacteriocin production.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie. P.U. is the recipient of a doctoral fellowship from the Région Bretagne.

V. Pichereau is acknowledged for analysis of 13C-NMR spectra.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boch J, Kempf B, Bremer E. Osmoregulation in Bacillus subtilis: synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine from exogenously provided choline. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5364–5371. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5364-5371.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csonka L N, Hanson A D. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:569–582. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vuyst L, Callewaert R, Crabbé K. Primary metabolite kinetics of bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus amylovorus and evidence for stimulation of bacteriocin production under unfavourable growth conditions. Microbiology. 1996;142:817–827. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaasker E, Konings W N, Poolman B. Osmotic regulation of intracellular solute pools in Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:575–582. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.575-582.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glaasker E, Tjan F S B, Ter Steeg P F, Konings W N, Poolman B. Physiological response of Lactobacillus plantarum to salt and nonelectrolyte stress. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4718–4723. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4718-4723.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gouesbet G, Blanco C, Hamelin J, Bernard T. Osmotic adjustment in Brevibacterium ammoniagenes: pipecolic acid accumulation at elevated osmolalities. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:959–965. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Staphylococcus aureus osmoregulation: roles of choline, glycine betaine, proline, and taurine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2711–2716. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2711-2716.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutkins R W, Ellefson W L, Kashket E R. Betaine transport imparts osmotolerance on a strain of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2275–2281. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2275-2281.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaenjak A, Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Choline transport activity in Staphylococcus aureus induced by osmotic stress and low phosphate concentrations. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2400–2406. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2400-2406.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kets E P W, Galinski E A, de Bont J A M. Carnitine: a novel compatible solute in Lactobacillus plantarum. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kets E P W, Teunissen P J M, de Bont J A M. Effect of compatible solutes on survival of lactic acid bacteria subjected to drying. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:259–261. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.259-261.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kets E P W, de Bont J A M. Effect of carnitines on Lactobacillus plantarum subjected to osmotic stress. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landfald B, Strom A R. Choline-glycine betaine pathway confers a high level of osmotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:849–855. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.849-855.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsusaki H, Hendo N, Sonomoto K, Ishizaki A. Lantibiotic nisin Z fermentative production by Lactococcus lactis I0-1: relationship between production of the lantibiotic and lactate and cell growth. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:36–40. doi: 10.1007/s002530050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayr-Harting H, Hedges J A, Berkeley R L W. Methods for studying bacteriocins. Methods Microbiol. 1972;7:315–422. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molenaar D, Hagting A, Alkema H, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Characteristics and osmoregulatory roles of uptake systems for proline and glycine betaine in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5438–5444. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5438-5444.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rincé A, Dufour A, Uguen P, Le Pennec J P, Haras D. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4252–4260. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4252-4260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thuault D, Beliard E, Le Guern J, Bourgeois C M. Inhibition of Clostridium tyrobutyricum by bacteriocin-like substances produced by lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:1145–1150. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R, Johnson M C, Ray B. Novel method to extract large amounts of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3355–3359. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3355-3359.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]