Abstract

The decimal reduction times of Streptococcus faecium, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis, and Aeromonas hydrophila corresponding to heat treatment at 62°C were 7.1, 0.34, 0.024, and 0.0096 min, and those corresponding to manosonication treatment (40°C, 200 kPa, 117 μm) were 4.0, 1.5, 0.86, and 0.90 min, respectively. The manosonication decimal reduction times of the four species investigated decreased sixfold when the amplitude was increased from 62 to 150 μm and fivefold when the relative pressure was raised from 0 to 400 kPa. In L. monocytogenes, S. enteritidis, and A. hydrophila, the lethal effect of manothermosonication was the result of the addition of the lethal effects of heat and manosonication, whereas in S. faecium it was a synergistic effect.

Heat is the most widely used sterilization method. To avoid unwanted effects of heat, many attempts have been made, especially in the last decade, to develop alternative procedures of bacterial inactivation (6).

The inactivation of microorganisms by ultrasonic waves (UW) was reported in the early 1930s (7), but its scant lethal effect has prevented its use as a sterilization method. However, the improvements in UW generation technology of the last few decades have stimulated the interest of investigators in microbial inactivation by UW.

In 1964, Neppiras and Hughes (10) reported that static pressure increased the inactivating effect of UW on yeasts. However, the lethality of these treatments was still low because of the low UW power used by those researchers. The combination of heat and high-power UW (20 kHz) (thermoultrasonication) was first explored by Ordóñez et al. (11). According to them, the inactivating effect of thermoultrasonication was greater than that of UW at room temperature. In 1992, Sala et al. (16) designed and built a resistometer to apply high-power UW under pressure at nonlethal (manosonication [MS]) and lethal (manothermosonication [MTS]) temperatures. Results obtained with this instrument demonstrated that the rate of vegetative-cell inactivation by MS increased drastically when the static pressure was raised. However, the increments in the inactivation rate increase decreased progressively the higher the static pressure (13, 12). It was also observed that the inactivation rate by MS increased exponentially with the amplitude of UW (13, 12). At nonlethal temperatures (MS), the inactivation rate by UW under pressure was always the same independently of temperature. At higher temperatures (MTS), it increased drastically. Raso et al. (13) concluded that the rate of Yersinia enterocolitica inactivation by MTS was an additive effect: the result of the inactivation rate of heat added to the inactivation rate of UW under pressure. However, in Bacillus subtilis spores, this lethal effect was a synergistic effect in the range of 70 to 90°C (14). Pagán (12) observed that the factors that increased the heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes hardly changed its resistance to MS treatments. That researcher (12) concluded that the advantage of using MS instead of heat to inactivate bacteria would be greater the greater the heat resistance shown by the microorganisms. No more data have been published on bacterial inactivation by MS and MTS since those of Raso et al. (13) on Y. enterocolitica and Pagán (12) on L. monocytogenes. Therefore, no general assumption can be made about the MS and MTS resistance of bacterial species.

In this research, the resistance of Streptococcus faecium, L. monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis, and Aeromonas hydrophila to heat, MS, and MTS treatments was investigated and compared. The influence of the amplitude of UW, static pressure, and temperature on the rate of inactivation by MS and MTS was also studied.

Bacterial culture and media.

The strains of S. faecium (STCC 410), L. monocytogenes (STCC 4031), S. enteritidis (STCC 4300), and A. hydrophila (STCC 839) used in this investigation were supplied by the Spanish Type Culture Collection. A suspension of each microorganism was prepared by inoculating 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of sterile tryptic soy broth (Biolife, Milan, Italy) with 0.6% yeast extract (Biolife) added to a final concentration of 106 cells ml−1. These flasks were incubated at 37°C until the culture reached the stationary growth phase and maximum heat resistance (data not shown).

Determination of resistance to heat, MS, and MTS.

Resistance to heat, MS, and MTS was determined with a specially designed resistometer as already described (13). Once the treatment temperature had attained stability, 0.2 ml of an adequately diluted cell suspension was injected into the 23-ml treatment chamber containing McIlvaine citrate-phosphate buffer at pH 7 (4). At least five 0.1-ml samples were collected at preset intervals in test tubes containing melted, sterile tryptic soy agar-yeast extract medium (Biolife). These tubes were immediately plated and incubated at 37°C for 48 h (S. faecium, S. enteritidis, and L. monocytogenes) or at 30°C for 24 h (A. hydrophila). Previous experiments showed that longer incubation times did not influence survivor counts (data not shown). CFU were counted with an improved Image Analyser Automatic Counter (Protos, Analytical Measuring Systems, Cambridge, United Kingdom) as previously described (3). The inactivation rate was measured by determining the decimal reduction time (D value; DT for heat, DMS for MS, and DMTS for MTS) calculated from the slope of the straight portion of the survival curve. DRTC curves were obtained by plotting log D values versus the corresponding treatment temperatures. For heat treatments, z values (°C increase in temperature required for the DT value to drop 1 log cycle) were calculated from the slope of the corresponding DRTC. Correlation coefficients (ro) and 95% confidence limits (CL) were calculated by the appropriate statistical package (StatView SE + Graphics, Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, Calif.). The statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) of differences between the D and z values was tested as described by Steel and Torrie (18). Regression lines of the influence of static pressure and UW amplitude were fitted and parameters were derived by using the Excel 5.0 package (Microsoft, Seattle, Wash.). The individual contributions of heat and UW to the lethal effect of MTS treatment at different temperatures was evaluated by determining how experimental values matched the theoretical DRTC. Theoretical DMTS values were calculated as described by Raso et al. (13), with the equation DMTS = (DT × DMS)/(DT + DMS).

Resistance to heat and MS treatments.

The DT and z values of our strains were in the range of most published data. For the most heat-resistant species (S. faecium), the D value for heat treatment at 62°C was approximately 700 times that of the last thermotolerant (A. hydrophila) (Table 1). Therefore, the intensity of a heat treatment designed to sterilize a given product contaminated with these species could vary up to 1,000-fold. On the contrary, resistance of the same species to MS treatment only varied approximately fivefold (Table 1) and the intensities of treatment required should not be very different. As shown by Table 1, gram-positive and coccal forms were, as found with heat (21) and UW (1, 2) inactivation, the most MS-resistant microorganisms. The greater the bacterial heat resistance, the lower the ratio of the heat inactivation rate to the MS inactivation rate.

TABLE 1.

Resistance of S. faecium, S. enteritidis, L. monocytogenes, and A. hydrophila to heat and MSa treatmentsb

| Species | D62c (95% CL) (min) | z (°C) | DMS (95% CL) (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. faecium | 7.1 (6.1–8.6) | 6.0 (4.9–7.7) | 4.0 (3.9–4.2) |

| S. enteritidis | 0.024 (0.021–0.028) | 4.4 (3.9–5.0) | 0.86 (0.76–0.98) |

| L. monocytogenes | 0.34 (0.31–0.37) | 5.9 (5.5–6.1) | 1.5 (1.5–1.6) |

| A. hydrophila | 0.0096 (0.0080–0.012) | 5.9 (5.6–6.1) | 0.90 (0.78–1.1) |

MS conditions: 40°C, 200 kPa, 117 μm.

Survival curves corresponding to these data always showed r0 ≥ 0.98.

D62, D value for heat treatment at 62°C.

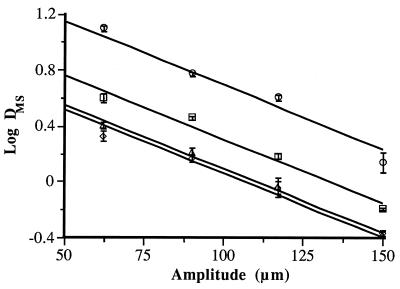

Effect of amplitude on MS inactivation rate.

At 200 kPa and 40°C, the DMS values of all of the species investigated decreased exponentially with UW amplitude increases between 62 and 150 μm (Fig. 1). No statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) were found among the slopes of the regression lines shown in Fig. 1. For all of the species investigated, the DMS value decreased by one-sixth when the amplitude was increased 100 μm. Therefore, in the range of UW amplitudes investigated, this relationship followed the general equation log DMS = log D0 − 0.0091 × (A − 62), where, DMS is the decimal reduction time for each MS treatment, D0 is the decimal reduction time of MS treatments at an amplitude of 62 μm, and A is the UW amplitude. The goodness of fit of this general equation for the four sets of experimental data is demonstrated by the high correlation between the theoretical and experimental values (r2 = 0.984). The inactivation of microorganisms suspended in a liquid medium by UW is thought to be due to cavitation (9). Bacterial inactivation by UW seems to be due to the very high pressures developed during cavitation (5, 17) and/or the release of free radicals in the medium (8, 15). Raso et al. (13) demonstrated that addition of free-radical scavengers to the medium did not influence the rate of Y. enterocolitica inactivation and concluded that vegetative cells were probably inactivated as a consequence of the mechanical disruption of the cell membranes. The higher inactivation rate at greater amplitudes could be due to an increase in the number of bubbles liable to implode per unit of time in a given volume and/or to an increase in the volume of liquid in which cavitation is liable to occur (20). The magnitude of the influence of UW amplitude on S. faecium, L. monocytogenes, S. enteritidis, and A. hydrophila was the same, independently of the individual resistance to MS treatment. These results indicated that differences in cell wall structure between the different species investigated did not modify the influence of the UW amplitude.

FIG. 1.

Influence of UW amplitude on the rate of inactivation by MS treatment (200 kPa, 40°C) of S. faecium (○), L. monocytogenes (□), S. enteritidis (▵), and A. hydrophila (◊).

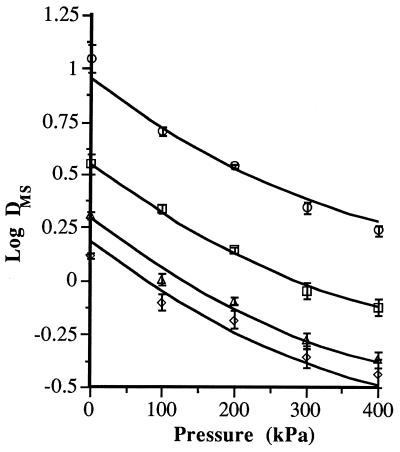

Effect of pressure on MS inactivation rate.

The rate of vegetative-cell inactivation by MS increased drastically with a rise in static pressure. However, as the pressure was raised, the magnitude of this increase decreased progressively (Fig. 2). This performance is described by the general equation log DMS = log D0 − 0.0026 × P + 2.2 · 10−6 × P2, where DMS is the decimal reduction time corresponding to MS treatments at an amplitude of 117 μm and 40°C, D0 is the D value corresponding to MS treatment at 117 μm and 40°C at ambient pressure, and P is the static relative pressure. The goodness of fit of this general equation for the four sets of experimental data is demonstrated by the high correlation between the theoretical and experimental values (r2 = 0.989). The magnitude of the effect of static pressure was the same for all of the species investigated. When the pressure was raised from 0 to 100 kPa, the DMS (117 μm and 40°C) dropped to one-half of its original value. However, a further pressure rise from 300 to 400 kPa only made this value decrease by approximately 20%. Static pressure during ultrasonic treatment increases the intensity of cavitation (19). The increase in the inactivation rate when the pressure was raised was probably due to an increase in bubble implosion intensity. The lower response to static pressure increases at higher pressures was probably due to the reduction in the number of bubbles undergoing cavitation (19). Overall, these physical changes affected all of the species investigated to the same extent.

FIG. 2.

Influence of pressure on the rate of inactivation by MS treatment (117 μm, 40°C) of S. faecium (○), L. monocytogenes (□), S. enteritidis (▵), and A. hydrophila (◊).

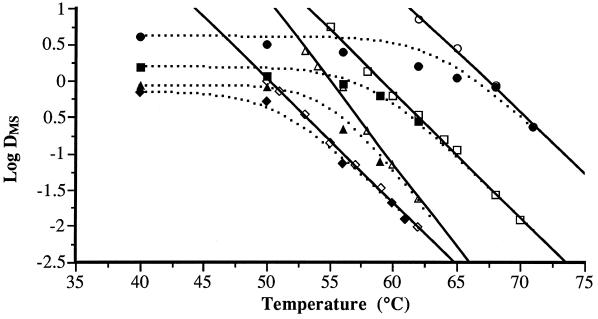

Effect of temperature on MS and MTS inactivation rates.

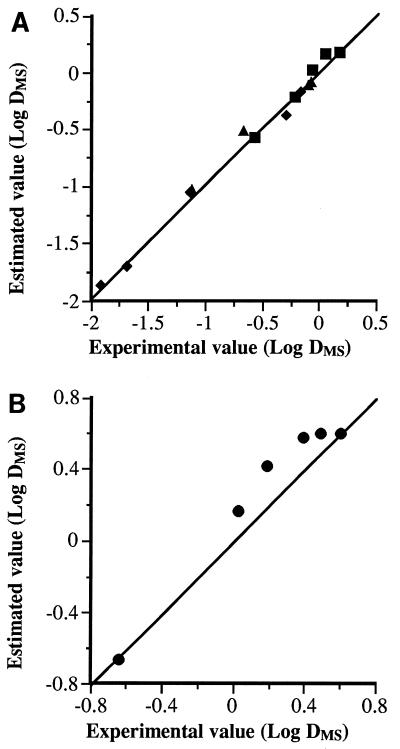

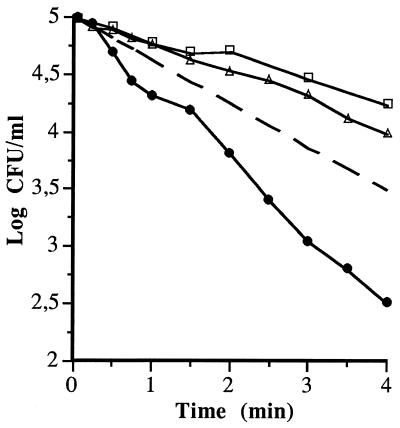

Figure 3 shows the experimental D values of MS and MTS treatments at different temperatures for the four bacterial species investigated. The theoretical DRTC corresponding to MTS treatments (dotted line), calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and the DRTC corresponding to heat treatments have also been included. The relationship between the experimental and theoretical MTS values is illustrated for S. enteritidis, L. monocytogenes, and A. hydrophila in Fig. 4A and for S. faecium in Fig. 4B. In the range of 40 to 68°C, the experimental values of S. faecium did not match the theoretical values (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the rate of S. faecium inactivation by MTS in this range seemed to be a synergistic instead of an additive effect. The magnitude of this synergistic effect at 62°C is illustrated in Fig. 5, which shows the survival curves of S. faecium corresponding to heat (62°C), MS (200 kPa, 117 μm, 40°C), and MTS (200 kPa, 117 μm, 62°C) treatments, as well as the theoretical survival curve (dotted line) that should be obtained if the effect of MTS is additive. The number of survivors after MTS treatment was lower (approximately 1 log cycle after 4 min of treatment) than that of the theoretical survival curve. The rate of inactivation by UW under pressure was independent of temperature until a maximum temperature was reached (MS). This maximum temperature was different for each bacterial species investigated (Fig. 3). At values above these maximum values, the inactivation rate increased drastically with temperature (MTS). Similar behavior was observed in Y. enterocolitica by Raso et al. (13), who hypothesized that this profile was the result of the addition of the inactivation rate of heat to the inactivation rate of UW under pressure. Our results obtained with L. monocytogenes, S. enteritidis, and A. hydrophila confirmed this hypothesis (Fig. 4A). On the contrary, we observed a disagreement between the theoretical values and experimental values obtained with S. faecium (Fig. 4B). As shown by Fig. 3, the experimental rate of S. faecium inactivation by MTS was higher than that calculated theoretically between 50 and 68°C. These results demonstrated that in this range of temperatures, the rate of S. faecium inactivation by MTS was the result of a synergistic instead of an additive effect (Fig. 5). A similar synergistic effect has also been observed in the inactivation by MTS of B. subtilis spores (14). Raso et al. (14) suggested that this synergistic effect could be due to disruption of the bacterial spore cortex, causing protoplast rehydration and loss of heat resistance. Perhaps similar damage in the cell wall peptidoglycan could explain this synergistic effect on S. faecium.

FIG. 3.

Influence of temperature on the rate of inactivation by heat (open symbols) and by UW under pressure (117 μm, 200 kPa) (closed symbols) of S. faecium (○, •), L. monocytogenes (□, ■), S. enteritidis (▵, ▴), and A. hydrophila (◊, ⧫). Theoretical D values (■) were calculated by the equation DMTS = (DMS × DT)/(DMS + DT).

FIG. 4.

Correlation between experimental and theoretical DMTS values, calculated by the equation DMTS = (DMS × DT)/(DMS + DT), for L. monocytogenes (■), S. enteritidis (▴), and A. hydrophila (⧫) (A) and for S. faecium (•) (B).

FIG. 5.

Survival curves of S. faecium subjected to heat (62°C) (□), MS (40°C, 200 kPa, 117 μm) (▵), and MTS (62°C, 200 kPa, 117 μm) (•) treatments. The dotted line represents the theoretical survival curve obtained by the equation DMTS = (DMS × DT)/(DMS + DT).

Conclusions.

We can conclude that the differences in vegetative cell resistance to MS were much smaller than those observed in resistance to heat treatment. The rate of bacterial cell inactivation by UW increased with increases in amplitude and static pressure, the magnitude of the increase being the same for all of the bacterial species investigated. Therefore, the influence of these factors can be predicted. The rate of L. monocytogenes, S. enteritidis, and A. hydrophila inactivation by MTS was the result of the additive effects of heat and UW under pressure, but a synergistic effect on S. faecium was found.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the CICYT (project ALI93-0360) and the Ministerio Español de Educación y Ciencia, which provided R. Pagán with a grant to carry out this investigation.

Our thanks to S. Kennelly for her collaboration in correcting the English of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed F I K, Russell C. Synergism between ultrasonic waves and hydrogen peroxide in the killing of micro-organisms. J Appl Bacteriol. 1975;39:31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1975.tb00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alliger H. Ultrasonic disruption. Am Lab. 1975;10:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Condón S, Palop A, Raso J, Sala F J. Influence of the incubation temperature after heat treatment upon the estimated heat resistance values of spores of Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson R M C, Elliot D C, Elliot W H, Jones K M. Data for biochemical research. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford at the Clarendon Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frizzell L A. Biological effects of acoustic cavitation. In: Suslick K, editor. Ultrasound: its chemical, physical, and biological effects. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers, Inc.; 1988. pp. 287–306. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould G W. New methods of food preservation. London, England: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey E N, Loomis A L. The destruction of luminous bacteria by high frequency sound waves. J Bacteriol. 1929;17:373–376. doi: 10.1128/jb.17.5.373-376.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs S E, Thornley M J. The lethal action of ultrasonic waves on bacteria suspended in milk and other liquids. J Appl Bacteriol. 1954;17:38–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neppiras E A. Acoustic cavitation. Phys Rep. 1980;61:159–251. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neppiras E A, Hughes D E. Some experiments on the disintegration of yeast by high intensity ultrasound. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1964;4:247–270. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ordóñez J A, Aguilera M A, García M L, Sanz B. Effect of combined ultrasonic and heat treatment (thermoultrasonication) on the survival of a strain of Staphylococcus aureus. J Dairy Sci. 1987;54:61–67. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900025206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagán R. Resistencia frente al calor y los ultrasonidos bajo presión de Aeromonas hydrophila, Yersinia enterocolitica y Listeria monocytogenes. Ph.D. thesis. Zaragoza, Spain: University of Zaragoza; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raso J, Pagán R, Condón S, Sala F J. Influence of temperature and pressure on the lethality of ultrasound. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:465–471. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.465-471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raso, J., A. Palop, R. Pagán, and S. Condón. Inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores by combining ultrasonic waves under pressure and mild heat treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Riesz P, Kondo T. Free radical formation induced by ultrasound and its biological implications. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13:247–270. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sala F J, Burgos J, Condón S, López P, Ordoñez J A, Raso J. Procedimiento para la destrucción de microorganismos y enzimas: proceso MTS. Spanish patent 93/00021; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherba G, Weigel R M, O’Brien J W D. Quantitative assessment of the germicidal efficacy of ultrasonic energy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2079–2084. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.2079-2084.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steel R G D, Torrie J H. Principles and procedures of statistics. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Book Co.; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suslick K S. Homogeneous sonochemistry. In: Suslick K S, editor. Ultrasound. Its chemical, physical, and biological effects. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers, Inc.; 1988. pp. 123–163. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suslick K S. Sonochemistry. Science. 1990;247:1439–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.247.4949.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomlins R I, Ordal Z J. Thermal injury and inactivation in vegetative bacteria. In: Skinner F A, Hugo W B, editors. Inhibition and inactivation of vegetative microbes. London, England: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 153–191. [Google Scholar]