Abstract

Common measures facilitate the standardization of assessment practices. These types of measures are needed to develop instruments that can be used to assess the overall effectiveness of the U54 Comprehensive Partnerships to Advance Cancer Health Equity (CPACHE) funding mechanism. Developing common measures requires a multi-phase process. Stakeholders used the nominal group technique, a consensus development process, and the Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM) platform to identify evaluation constructs and measures of those constructs. Use of these instruments will ensure the implementation of standardized data elements, facilitate data integration, enhance the quality of evaluation reporting to the National Cancer Institute, foster comparative analyses across centers, and support the national assessment of the CPACHE program.

Keywords: Common evaluation measures, National Cancer Institute, Underrepresented minority (URM), U54 Comprehensive Partnerships to Advance Cancer Health Equity (CPACHE), Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM)

Introduction

The purpose of the U54 Comprehensive Partnerships to Advance Cancer Health Equity (CPACHE) funding mechanism is to develop and maintain comprehensive, long-term, and mutually beneficial partnerships between institutions serving underserved populations, underrepresented students (ISUPS), and the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers. The aim of this partnership program is to foster and support collaborations that result in developing stronger cancer programs, which in turn promote an understanding of how cancer health disparities disproportionately affect underserved populations, including racial and ethnic minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, and rural populations. The goals of the CPACHE program are to (1) increase the cancer research and cancer research education capacity of ISUPS; (2) increase the number of underrepresented minority (URM) students and investigators engaged in cancer research; (3) improve cancer center effectiveness in developing and sustaining research programs focused on cancer health disparities; (4) increase the number of investigators and students conducting cancer health disparities research; and (5) develop and implement cancer-related activities that benefit the surrounding underserved communities.

The CPACHE program, initiated in 2001, historically has relied on the evaluation of site-specific grant-related indicators. The NCI has given sites considerable autonomy over the process and outcome indicators they elect to track and measure. Evaluation practice is grounded by an awareness of partnership foci, program initiatives, and contextualized influences and demands. However, efforts to document the overall CPACHE impacts have been limited by a lack of shared outcomes and measures across sites. Recently, the NCI and individual CPACHE sites have undertaken a concerted effort to implement a more robust approach to program evaluation.

During the first phase of this project (2018–2019), the NCI and partnership evaluators developed and recommended use of a harmonized set of indicators across all sites. To initiate that process, all partnerships were encouraged to submit site-specific outcome and impact indicators associated with the CPACHE program goals; 56% (9/16) sites participated. The submissions enabled the development of a program evaluation matrix with common indicators that aligned with the CPACHE objectives listed above. The evaluators, Principal Investigators of each site, and NCI reached consensus on these indicators [1]. Phase 2, the main focus of this manuscript, was initiated in the summer of 2019. This phase included the creation of two Special Interest Groups (SIG) led by a subset of CPACHE evaluators and an NCI representative. The SIGs focused their work on developing shared measures specific to the aforementioned first, second, fourth, and fifth CPACHE objectives. Specifically, they worked to develop two types of constructs and measures. The first set was related to research educational practices, which were intended to prepare underrepresented individuals for engagement in cancer or cancer disparity research and to promote their transition into leadership roles. The second set of constructs and measures were related to community outreach and engagement which focused on reducing cancer-related health disparities among underserved populations. This paper describes the processes that CPACHE evaluators used to develop and standardize a set of constructs, indicators, and survey items while integrating locally driven definitions to ensure the utility of cross-institutional datasets and analyses to address both NCI and institutional site requirements.

Background

The practice of evaluation is guided by systematic activities that are designed to assess the extent to which specified objectives are met. For federally funded programs, evaluation is intended to provide stakeholders with information and accountability related to how awards are utilized. Procedurally, evaluation offers real-time assessments to depict to what extent grant objectives are met and to offer insight into how best to address the challenges associated with unmet objectives.

Evaluators are trained to observe, document, and analyze datasets that are grounded by the dynamics of person, place, time, and activities. Often, evaluation findings are used to inform programmatic changes. For example, to ensure attainment of pre-determined performance levels, personnel may need to implement changes in resource allocation and training methods, or modify the activities that are provided to trainees. Assessments used in evaluation can focus on the following: (a) processes that yield outputs, (b) how inputs influence outputs, (c) the impacts associated with outputs, or (d) offering insight into how and why outcomes occur. Irrespective of the foci that are the subject of inquiry, evaluators strive to demonstrate and explain the ways in which process may drive outcomes and provide feedback to inform programmatic changes.

Efforts to impose standardization on the evaluation practices across programs that are funded by the same federal mechanism may instigate tension. On the one hand, those who fund multi-site initiatives have many reasons to request standardized indicators and methods of data collection across sites. The generation of data based on common measures can aid in assessing the degree to which the intended impact of initiatives has been met and advance cross-site comparisons [2]. Shared metrics can be useful in articulating a shared set of values, goals, and intended outcomes while showcasing the efficacy of related educational and outreach activities across sites [3]. The development of shared metrics, via sharing harmonized data that uses common measures, can also promote the usability of measurement tools that have been vetted and tested in public health research environments, thereby improving reliability and validity of process and outcome measurement. Additionally, the use of common measures facilitates data sharing between institutions and systems that catalog scientific measures and constructs [4]. The development of shared metrics across grantee sites has been a characteristic of several federal grant programs, including the Center for Translational Sciences Award program [5–7], and the Institute of Medicine’s Core Metrics initiative [8].

Standardized approaches to data collection can lead to undesirable scenarios. Using pre-selected indicators or amassing data that responds to funder’s evaluation needs may avert an individual site’s ability to communicate their unique contribution, on-going improvement, or strategic mission [9]. The proliferation of shared metrics can also add reporting burdens to individual sites and detract from efforts to use site-specific metrics that evaluators intended to measure [8]. However, developing processes that promote multi-site evaluation while also honoring the goals, strategies, and particularities of individual sites is needed to move the evaluation of federal initiatives beyond site specificity towards a national-centric or system perspective. Blumenthal and McGinnis [8] suggested the strategic use of consensus building to mediate negative outcomes related to shared metrics while supporting the overarching goal of program improvement and accountability. Below, we describe our work as an example of one such process.

Methods

Special Interest Groups (SIGs)

In the second phase of the CPACHE evaluator initiative, two Special Interest Groups (SIGs) led by a subset of CPACHE evaluators and an NCI representative were established. The CPACHE evaluators agreed to sharing the group’s leadership via rotating responsibilities following each phase. At the end of the academic year in 2019, the CPACHE evaluation workgroup leader sought volunteers to assume leadership for the CPACHE evaluator group. Evaluation core leaders from the University of Florida-University of Southern California-Florida Agricultural and Mining University partnership; the Northern Arizona University-University of Arizona partnership; and the Meharry-Vanderbilt-TSU Cancer Partnership, and a representative from the National Cancer Institute volunteered to co-lead the CPACHE evaluator group for the upcoming academic year. Two work groups were identified: the Research Education SIG steered by the evaluation core leaders from the University of Florida and Vanderbilt University and the Outreach SIG, steered by the evaluation core leader from the Northern Arizona University and the National Cancer Institute representative. The SIG co-leaders met monthly during from late spring until early fall and discussed potential processes aimed at developing shared measures specific to the aforementioned first, second, fourth, and fifth of the CPACHE objectives. They presented a rationale to support this initiative during a September 2019 meeting with the entire CPACHE evaluator group. The evaluator group decided to expand previous work by identifying systematic approaches and examining how and why outcomes occur. During the 2-step process used in phase two, the SIGs proposed to develop standardized data collection methods, and more importantly, common measures that could be validated to facilitate comparative analyses across center outcomes. All CPACHE evaluators (representing the 16 partnerships) were invited to participate in one or both SIGS. Collectively, the partnerships comprised 16 cancer centers (CC) and 18 ISUPS. Eleven partnerships, including 11 (69%) CC and 13 (72%) ISUPS, were represented in Research Education. Seven centers (44%) including seven CC and eight (44%) ISUPS participated in Outreach. Across both SIGS, 11 (69%) center evaluators and one NCI contract evaluator participated. The evaluators represented their partnership and not the specific institution in which they reside.

Definition of Consensus

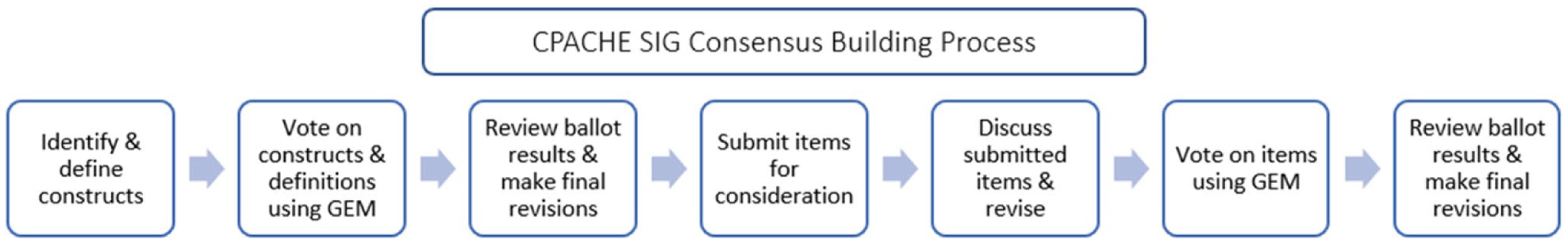

Drawing upon the instrument development process described by Jones & Hunter [10], the Research Education and Outreach SIGs used a modified version of the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) to develop a shared set of constructs and measurement items. We defined constructs as discrete types of phenomena (e.g., mentor characteristics, population characteristics) or outcomes (e.g., research knowledge, knowledge of cancer screening). Measurement items were defined as individual questions (typically survey questions) intended to measure the construct in question. Each SIG met monthly via Zoom, which had the added advantage of recorded meetings. This facilitated our process by providing documentation (in addition to SIG co-lead notetaking) and provided the opportunity for people to watch recordings of any meetings they were unable to attend. Each SIG first agreed on a set of constructs, and then went back and identified or developed measurement items for each construct. Consensus, or agreement, was reached through a 2-step process, described in more detail below. Both steps were facilitated by the instrument creation and voting tools available in the NIH’s Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM) system [11]. Step 1 activities consisted of inviting SIG members to vote on constructs and definitions (during construct development), and item development (during item development). Consensus was defined by an affirmative vote result of 80% or greater. When voting members voted against an item as written, they were given the opportunity to provide suggested revisions (see Appendices A and B). During step 2, the SIG co-leaders shared voting results with members. In instances where revisions pertained to wordsmithing, SIG co-leaders made these minor changes and shared the edited version with the group. Feedback received during voting was recorded and discussed during SIG meetings. Each group member was invited to indicate agreement with suggested revisions. Members reached agreement about changes in construct or item definitions before proceeding with the subsequent definitions and finalizing revisions. Figure 1 illustrates the consensus building process.

Fig. 1.

CPACHE SIG consensus building process, adapted from [10]

Construct Identification and Item Development

To identify common evaluation constructs (for both the Research Education and Outreach SIGs), the evaluators re-examined the outcome and impact measures from nine sites that had previously submitted a site-specific evaluation matrix (outlined in phase 1 above). Following their review, they developed an initial list of constructs. SIG members were invited to collect additional feedback from their site program staff/leadership. For example, the Outreach SIG invited Outreach leads across sites to review the Outreach constructs and definitions, to identify any potential gaps, and to clarify any items. Following the identification of constructs and the development of definitions, each SIG team member was invited to share institutional instruments and/or related items in the Dropbox folder for each construct. SIG co-leaders culled contributions and developed a set of items for the group’s consideration. While gathering contributions, the SIG co-leaders looked for overlap among submitted instruments. The goal was to develop items that would likely be applicable across all CPACHE centers. The list of proposed items was discussed at subsequent meetings. To ensure the proper attribution, each partnership was asked to indicate if items came from their partnership, a publication, or other source. Out of consideration for intellectual property rights, members were asked not to borrow any of the tools placed into the Dropbox without consent or appropriate acknowledgement. This process took place over the course of nearly 18 months as the SIGs reviewed the items aligned with a specified set of constructs during each meeting, until all constructs had been identified and defined and items developed for each of the constructs.

Prior to each meeting, the SIG co-leaders sent the list of harmonized items to the SIG members. Members were asked to review the recommended items and come prepared to suggest any changes for the group’s consideration at the next meeting. During SIG meetings, a significant amount of time was devoted to discussing all suggested revisions and to ensuring that items were inclusive. For example: Was appropriate language used? Does each item consider the breadth of the CPACHE portfolio such as sites differing specific aims? Are regional/population differences accounted for? Following each meeting, the revised working document was distributed to the SIG. Members were given a deadline to submit any additional revisions. This period of time enabled SIG members to review and process the items on their own time rather than within the 1-h scheduled SIG meeting period.

Similar to the construct voting process, a ballot was developed and sent via the GEM website to preserve the confidentiality of each member and sought member input regarding their agreement with the item. Members were asked to select “yes” to signify their agreement or select “no” if they did not agree. For any items where a voting member selected “no,” they were asked to suggest a revision. Prior to each balloting period voting, the SIG co-leaders sent advance notice indicating when the ballot would open and close. The review and discussion of construct items were sequenced (e.g., several items were covered at each monthly meeting). To decrease burden, the voting process was broken into several ballots, with each ballot including a subset of the items that were discussed at the most recent SIG meeting. Sites were encouraged to engage in internal discussions with their respective Research Education Core (REC) and Outreach Core (OC) leads regarding the items that were submitted for consideration and the ballot feedback. The revised construct items were sent out to the SIG for a final review and approval.

Results

This section includes the consensually agreed upon CPACHE Research Education and Outreach evaluation constructs and definitions (Tables 1 and 2). Corresponding items have been developed for each construct and packaged into CPACHE Evaluation Toolkits for Research Education and Outreach and will be reported in subsequent manuscripts.

Table 1.

Research education constructs and definitions

| Research education evaluation constructs | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Trainee/ ESI Demographics | Name Training level Date of completion of highest degree Trainee/ESI: Current and future cancer research foci—research type, cancer type, population of interest, specific cancer research focus (open-ended) Career interest Age Gender Race Ethnicity Background (refers to someone who comes from a low-income background, or who grew up in a social/cultural/educational environment in which s/he did not have access to the knowledge, skills, or abilities that facilitate opportunities to participate in research careers) First generation college student Institutional Affiliation |

| Trainee/ESI Context | Types of training opportunities across PACHE Perceived value of engagement/training opportunities |

| Mentor Characteristics | Mentor Demographics Mentor Institution Mentor Date of completion of highest degree Mentor Current cancer research focus—research type, cancer type, population of interest, & specific cancer research focus (open-ended) |

| Researcher Efficacy: Trainee/ESI perceptions of competency in capacity | Trainee/ESI’s perceived competence and independence in conducting rigorous and ethical cancer research (aligned with trainee/ESI’s level of education and/or professional position) |

| Researcher Efficacy: Mentor perceptions of trainee/ESI competency in capacity | Mentor’s perception of trainee/ESI competence and independence in conducting rigorous and ethical cancer research (aligned with Trainee/ESI’s level of education and/or professional position) |

| Trainee/ESI research knowledge | Trainee/ESI proficiency in research investigation |

| Trainee/ESI competency attribution | Contributions of mentoring relationships to trainee/ESI skill and knowledge advancement |

| Trainee/ESI social development | Contributions of mentoring relationships to trainee/ESI anticipatory socialization of chosen profession |

| Trainee/ESI mentor interactions | Quality of interactions (time, respect, acknowledgement) |

| Trainee/ESI perceived benefits of mentoring | Expected vs. actual benefits of mentoring |

| Trainee/ESI mentoring context | Meeting frequency, number of hours per week spent in research experiences, person(s) doing mentoring, duration of experience |

| Mentor Competency | Mentor’s perceptions of their own work and competency when mentoring trainees/ESIs |

| Mentor Competency: Trainee/ESI | Trainee/ESIs perception of mentor’s competency |

| URM Supportive Policies | Creation or change of policies that support URM (trainee/ESI/other faculty) |

| URM Supportive Practices | Creation or change of practices that support URM (trainee/ESI/other faculty) |

| URM Supportive Partnerships | Development of institutional partnerships that compliment and/or enhance the work of the U54 |

Table 2.

Outreach constructs and definitions

| Outreach evaluation construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Demographic and population Characteristics | Identification of the population (community members or members of community organizations) engaged |

| Cancer priorities | Identification of cancer priorities and needs |

| Cancer-related policy development | Fidelity of written vs enacted cancer policy |

| Cancer-related policy implementation | Intended or unintended consequences (positive/negative) of policy implementation |

| Cancer knowledge and awareness | Change in participant familiarity with cancer types, risks, prevention, screening, caretakers, quality of life, precision medicine, clinical trials, or bio-banking |

| Investigator knowledge/skills | Changes in investigator knowledge/skills regarding culturally responsive community engagement or patient practices in research and effective strategies for disseminating results to lay audiences |

| Investigator engagement | Changes in investigator community-oriented research practice |

| Cancer services | Types of cancer-related resources available through CPACHE programming |

| Service barriers | Identification of barriers to access for cancer services/delivery needs and strategies or modalities for the removal of those barriers |

| Access to and utilization of cancer data | Population’s ability to access information and utilization of cancer data for decision making |

| Utilization of cancer services | Use of prevention, screening, diagnostic/treatment services |

| Cancer clinical trials | Enrollment in cancer-related trials |

| Biospecimen donations | Education about biospecimen donations |

| Dissemination of research findings to communities | Sharing community-centric findings in a culturally responsive manner |

| Community engagement | Bi-directional communication in cancer research topic identification, shared decision making and trust building and new partnership development |

| Community capacity building | Fostering community contributions to cancer-related research, outreach or cancer programming, and negotiating IRB/data ownership and return on investment (ROI) |

Dissemination of CPACHE Evaluation Resources: Grid-Enabled Measures (GEM)

Once the groups reached consensus on all survey items, the SIG co-leaders organized them into survey instruments based on the content of the questions as well as expectations of when the survey items would be administered. For example, the Research Education SIG developed instruments that would be given at the beginning of a trainee’s or ESI’s cancer research experience—a demographic survey and a demographic survey given to the mentor. Trainee/ESI and mentor pre- and post-test surveys were developed to assess trainee/ESI and mentor’s expected impact and actual impact of research education activities, and a post-test only survey designed to assess the institutional impact on changes in policies, practices, and partnerships that are supportive of underrepresented minorities (URMs). During this process, there were some additional revisions to specific survey questions (in most cases, removing survey questions that were redundant or unlikely to lead to actionable knowledge), and minor revisions to constructs and definitions. Although evaluators did not return to voting during the survey creation process, each change was discussed during monthly evaluator meetings; changes were made when consensus was reached. For the purposes of this paper, we have included the initially agreed upon constructs and definitions that were developed through the consensus process. Surveys were packaged in a toolkit to aide any CPACHE site intending to implement the measures as to how, when, and with whom to implement them. These toolkits (as well as the surveys) will be made available in a public format to all current and future grantees. Institutional sites will be able to adapt and create site-specific questionnaires into the platforms that they use to collect data. Furthermore, a data dictionary for each of the REC instruments was developed by Vanderbilt University, with the support of NIH funding, in Vanderbilt’s REDCap platform—a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases. The REDCap Consortium comprises thousands of active institutional partners in over one hundred countries, including many of the CPACHE site institutional partners. Although not all sites use REDCap, for those that do, there is a data dictionary that can be uploaded into the REDCap platform. Institutional sites will be able to create electronic versions of the surveys for ready administration with limited edits and setup. The creation of the data dictionary also allows for the setup of standardized data collection methods and naming conventions that allow for facile integration of datasets from individual sites.

Discussion

The CPACHE evaluation SIGs developed and implemented a process while integrating NCI funded CPACHE program goals, evaluation priorities identified by individual CPACHE sites, and using literature from the fields of education and community engagement to inform constructs and measurement tools. The process yielded constructs and instruments agreed upon by multiple sites with multiple priorities and different foci. The SIGs developed evaluation tools and shared measures that allow for flexibility and minimize respondent and evaluator burden, to address cross-site variability.

The consensus-based approach, although more time intensive than a unilateral approach, likely strengthened the quality of the work and subsequent toolkit. Inviting participation from evaluators across career stages, with varied expertise, and geographic variability also brought a wealth of information. Although the consensus process was formalized by agreed upon procedures, monthly meetings allowed for meaningful discussion about what specific activities sites were currently implementing to acquire CPACHE goals. Working together in a collaborative setting enabled members to feel comfortable to question how data would be used to inform program change or measure outcomes or demonstrate impact. The SIG members also raised questions about who would be responsible for reporting or completing an instrument, the frequency for data collection, and how outcomes would relate to program context.

This collaborative process resulted in the identification of Research Education and Outreach-specific evaluation constructs that will yield standardized measures for the U54 CPACHE centers to (1) foster data integration, standardization of data elements, and data interoperability to enhance the quality of evaluation reporting to NCI; (2) promote a robust understanding of how funding benefits trainees/ESIs, community locales, patient advocates, and others that are served; (3) initiate comparative inquiries across centers; and (4) support an expansion of the NCIs’ portfolio analysis while enriching the national assessment of the CPACHE program impact. Standardization in data collection will enhance an understanding of what works well across the centers, and lead to answering questions about training processes and community outreach initiatives that heretofore remain unexplored. However, future studies are needed to assess center adherence in use of these measures and to assess their efficacy.

This consensus-based approach achieved two major goals. First, the process allowed for input from all participating CPACHE sites. This process acknowledged the unique characteristics of the sites, while emphasizing the value of shared common constructs and measures. In addition, participating evaluators were encouraged to share the SIG’s work with their site’s Research Education and Outreach cores to obtain their input as the process unfolded. Second, the process resulted in a common set of measures that all sites could utilize. The value in the use of common measures cannot be understated. In order to evaluate a program like CPACHE, common measures facilitate the evaluation process by allowing for pooling of data across partnerships and making valid comparisons between sites as necessary. To be sure, the identification of best practices is limited when sites use unique measures; “best practices” can only truly be identified when there is replication of the practices across multiple sites that are measured similarly. Program evaluation, as opposed to a site evaluation, requires pooling of data that is clearly facilitated by the use of shared constructs and measures. Federally funded programs such as the CPACHE have long histories, with variation in funding timelines across sites. Given the complexity of implementing new metrics or adapting existing tools that have already been established at various CPACHE sites, the use of these evaluation instruments is not required. Nevertheless, the Research Education and Outreach Evaluation Toolkits offer an opportunity to increase the power of our findings and the ability to compare outcomes across sites. The NCI continues to encourage the use of site-specific evaluation constructs in addition to adopting common metrics and measures. We hope the process will lead to evaluators working together on cross-site studies. This collaborative, cross-site process fostered a community of practice for refining shared measures with the potential to grow into other areas (e.g., sharing ideas about community engagement initiatives). The process of common measures has the potential to ensure standardized common data collection and result sharing that may accelerate knowledge accumulation [4].

Limitations

During phase 1, all actively funded partnerships were invited to participate; however, only 56% (9/16) of sites participated. Again, during phase 2, all actively funded partnerships were invited to participate; however, only 11 of 16 (69%) partnerships engaged in the SIG. Thus, other evaluation constructs and measures used by non-participating sites for CPACHE activities may not be included in the respective Toolkits. Despite this limitation, however, non-participating sites are encouraged to adopt the common measures while still allowing for their site-specific measures.

Recommendations for Further Study

Validation of Instruments

Some of the measurement instruments identified during the consensus process have been in use; however, most are site-specific instruments that have not been validated. Pooling data from these instruments will facilitate psychometric studies and may lead to further recommended use. Studies, conducted at the national level, could lead to exploring potential differences based on target populations and geographic area that otherwise could not be undertaken.

Opportunities for Multi-site Projects

Adopting common constructs and measures will facilitate cross-partnership studies to, among other objectives, identify best practices. Best practices are unlikely to be identified at a single site as they are likely limited to site-specific particularities which are guided by specific target groups and processes. Cross-partnership collaborations with specific research questions could help identify these best practices and any nuances that may need to be considered when adopting such practices.

Conclusion

In this methods paper, we have presented an approach to developing common measures for the U54 CPACHE funding mechanism. The subsequent adoption and use of these common measures will likely yield an improved understanding of how funding benefits trainees, communities, patients, advocates, and practitioners. This approach will promote comparative inquiries across centers while fostering a better understanding of what works well across the centers and answer other questions about research education and community outreach initiatives that heretofore remain unexplored.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank members of the CPACHE Evaluation Special Interest Groups (SIGs): Anthony Barrios; Hali Robinette, MPH; Jessica McIntyre, BA; Kevin Cassel, DrPH; Kimberly Harris, PhD; Kristi Holmes, PhD; Lecarde Webb, MPH; Leo Spychala, MPH; Mirza Rivera Lugo, MS, MT; Sherri De Jesus, PhD, MHA; Tanya Penn, MPH, CPH (in alphabetical order). The authors extend their gratitude to Isabel C. Scarinci, PhD, MPH, for her leadership during phase 1 of this endeavor. Finally, David Garner, Ashley Eure, and the Westat team developed the ballots for the consensus building process and prepared the results via GEM.

Finally, the authors extend their gratitude to the National Cancer Institute team for their continued support of this national collaboration. The authors express gratitude to the following NCI team members for their continued interest and engagement in the project: LeeAnn Bailey, M.B.B.S, Ph.D., M.S. (Chief, Integrated Networks Branch); H. Nelson Aguila, D.V.M. (Deputy Director); Emmanuel A. Taylor, M.Sc., Dr.P.H. (Program Director), and Richard P. Moser, Ph.D. (Training Director and Research Methods Coordinator in the Behavioral Research Program’s Office of the Associate Director).

Funding

This work received funding from the National Institutes of Health CPACHE: The Florida-California NCI U54 CaRE2 Center, University of Florida U54CA233444, University of Southern California U54CA233465, and Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University U54CA233396; The Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention, University of Arizona U54CA143924 and Northern Arizona University U54CA143925; Meharry Medical College (MMC), Tennessee State University (TSU); and Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) Partners in Eliminating Cancer Disparities U54 U54CA163072.

Appendix A. CPACHE Research Education SIG GEM Ballot Sample Items

Only one vote may be cast per CPACHE partnership. Please communicate with your partner institution(s) before submission to ensure only one vote is submitted on behalf of your program.

![]()

Appendix B. CPACHE Outreach SIG GEM Ballot Sample Items

Only one vote may be cast per CPACHE partnership. Please communicate with your partner institution(s) before submission to ensure only one vote is submitted on behalf of your program.

![]()

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

We have presented an approach to developing common measures for the U54 CPACHE funding mechanism.

We used a consensus-based process to identify constructs and instruments agreed upon by multiple sites with multiple priorities and different foci.

We identified Research Education and Outreach specific evaluation constructs that will yield standardized measures for the U54 CPACHE centers.

References

- 1.McIntyre J, Peral S, Dodd SJ, Behar-Horenstein LS, Madanat H, Shain A, DeJesus S, Laurila K, Robinett H, Holmes K, Aguila N, Marzan M, Spychala L, Barrios A, Rivers D, Loest H, Drennan M, Suiter S, Richey J, Brown T, Webb L, Hubbard K, Scarinci IC. Abstract D041: efforts to implement a participatory evaluation plan for comprehensive partnerships to advance cancer health equity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 10.1158/1538-7755.DISP19-D041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straw R, Herrell J (2002) A framework for understanding and improvingmultisite evaluations. New Dir Eval 94:5–16 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elder MM, Carter-Edwards L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, Wallerstein N (2013) A logic model for communityengagement within the ctsa consortium: can we measure what we model? Acad Med 88(10): 1430–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moser RP, Hesse BW, Shaikh AR,Courtney P, Morgan G, Augustson E, Kobrin S, Levin KY,Helba C, Garner D, Dunn M, Coa K (2011) Grid-enabled measures: using science 2.0 to standardizemeasures and share data. Am J Prev Med 40(5 Suppl 2):S134–S143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel T, Rainwater J, Trochim WM,Elworth JT, Scholl L, Dave G, Members of the CTSA EvaluationGuidelines Working Group (2019) Opportunities for strengthening CTSAevaluation. J Clin Transl Res Sci 3(2/3):59–64. 10.1017/cts.2019.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubio DM, Blank AE, Dozier A, Hites L, Gilliam VA, Hunt J, Rainwater J, Trochim WM (2015) Developing common metrics for the clinical and translational science awards(CTSAs): lessons learned. Clin Transl Sci 8(5):451–69. 10.1111/cts.12296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sy A, Hayes T, Laurila K, Noboa C, Langwerden RJ, Andújar-Pérez DA, Stevenson L, RandolphCunningham SM, Rollins L, Madanat H, Penn T, Mehravaran S (2020) Evaluating research centers in minority institutions: framework,metrics, best practices, and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(22):8373. 10.3390/ijerph17228373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal D, McGinnis JM (2015) Measuringvital signs: an IOM report on core metrics for health and health care progress. JAMA 313(19): 1901–1902. 10.1001/jama.2015.4862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snibbe AC (2006) Drowning in data. Stanf Soc Innov Rev 39–15. Retrieved from http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/drowning_in_data [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones J, Hunter D (1995) Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 311(7001):376–80. 10.2164/jandrol.111.015065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grid Enabled Measures(GEM) (No date). https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/grid-enabled-measures-database