Abstract

This cross-sectional study of 2231 Japanese adults described food choice values and food literacy in relation to sex, age, and body mass index. We assessed eight food choice values (accessibility, convenience, health/weight control, tradition, sensory appeal, organic, comfort, and safety, using a 25-item scale), as well as food literacy, which was characterized by nutrition knowledge (using a validated 143-item questionnaire), cooking and food skills (using 14- and 19-item scales, respectively), and eight eating behaviors (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, enjoyment of food, satiety responsiveness, emotional undereating, food fussiness, and slowness in eating, using the 35-item Adult Eating Behavior Questionnaire). Females had higher means of all the variables than males, except for food fussiness. Compared to participants aged 19–39 and/or 40–59 years, those aged 60–80 years had low means of some food choice values (accessibility, convenience, sensory appeal, and comfort), nutrition knowledge, and all the food approach behaviors (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, and enjoyment of food) and high means of other food choice values (tradition, organic, and safety) and slowness in eating. Age was inversely associated with cooking and food skills in males, whereas the opposite was observed in females. The associations with body mass index were generally weak. These findings serve as both a reference and an indication for future research.

Keywords: diet, nutrition, food, value, literacy, knowledge, skill, behavior, sex, age, Japan

1. Introduction

According to a global estimate, dietary factors are responsible for 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life years (22% and 15% of total numbers, respectively) annually [1]. Not only because this magnitude is larger than any other risk factor, including tobacco smoking, but also because diet is modifiable, improving the quality of diet is now a global priority [2]. Unfortunately, “one-size-fits-all” dietary guidelines do not achieve the changes in dietary behavior needed to achieve healthier dietary patterns [3]. Considering the complex and varied nature of individual characteristics that are related to dietary behaviors [4], there is great interest in investigating and understanding factors that shape food choices and eating behaviors. What is intriguing in this context is the concept of food choice values, defined as factors that individuals consider when deciding which foods to purchase and/or consume [5]. On the basis of the food choice process model [6], food choice values are supposed to represent the proximal influences on food choice and eating behaviors, conveying the effects of more distal determinants, including life course factors (such as socioeconomic factors), sociocultural resources, and cognitive resources [5].

Another concept recently emerging is food literacy. Although there are a number of definitions of food literacy in the literature [7,8,9], the most widely cited definition is that developed by Vidgen and Gallegos [10]. In their definition, food literacy is described as “a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviors required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat food to meet needs and determine intake” [10]. Thus, food literacy is not just nutrition knowledge but also includes skills and behaviors, from knowing where food comes from to the ability to select and prepare these foods and behave in ways that meet dietary guidelines [11].

Measurement and investigation of food choice values [5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] and food literacy [7,8,9,10,11,20,21,22] have been almost exclusively conducted in Western countries, with no information available in Japan. Although it is widely perceived that the diet consumed by the Japanese population is healthy, recent evidence suggests that the overall diet quality in Japanese adults is far from optimal and that there are different nutritional concerns between Japan and Western countries [23,24,25]. To formulate meaningful dietary guidelines and public health messages and develop effective intervention strategies to promote healthy eating, a comprehensive report on food choice values and food literacy among the general population is imperative.

Therefore, the aim of the present cross-sectional study was to describe food choice values and food literacy in a nationwide sample of Japanese adults aged 19–80 years, with a particular focus on their associations with sex, age, and body mass index (BMI). Informed by the definition mentioned above [10], food literacy was characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, food skills, and eating behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Procedure and Participants

This cross-sectional analysis was based on a nationwide questionnaire survey conducted between October and December 2018. The target population consisted of adult participants in the MINNADE (MINistry of health, labor and welfare-sponsored NAtionwide study on Dietary intake Evaluation) study, a nationwide dietary survey, in which an 8-day weighed dietary record was collected [26]. Participants were apparently healthy Japanese adults living in private households in Japan. Inclusion criteria consisted of willingness to participate and community-dwelling (free-living) individuals. Exclusion criteria were dietitians, individuals living with a dietitian, those working with a research dietitian, those who had received dietary counseling from a doctor or dietitian, those taking insulin treatment for diabetes, those receiving dialysis treatment, and pregnant or lactating women. Participation of only one person per household was permitted. Initially, 32 (of 47) prefectures, accounting for >85% of the total population of Japan, were selected on the basis of geographical diversity and feasibility of the survey. After being recruited in person or by email, a total of 475 research dietitians agreed to support the study by collecting data. They then recruited participants from local communities. The non-random sampling procedure was performed to reflect the proportion of the overall Japanese population in each region but with the intention to recruit an equal number of males and females.

Of 2983 adult participants in the MINNADE study (n = 126 for age 19 years, 480 for age 20–29 years, 476 for age 30–39 years, 475 for age 40–49 years, 474 for age 50–59 years, 479 for age 60–69 years, and 473 for age ≥ 70 years), 2248 individuals participated in the present study (response rate: 75%). For analysis, we excluded participants with missing information related to the variables of interest (n = 5) and those aged outside the 19–80 year age range (n = 12), leaving 2231 participants aged 19–80 years.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine (protocol code: 12031; date of approval: 17 July 2018). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and from a parent or guardian for participants aged <20 years.

2.2. Basic Characteristics

All information was collected by questionnaires specially designed for this survey. Responses to all questions (except for those with regard to nutrition knowledge) were checked by staff at the study center. If any responses were missing, the participant was asked to complete the questions again in person or by telephone. Sex was self-reported. Age at the time of the study was calculated based on birth date of the participant and the date the questionnaires were answered. BMI (in kg/m2) was calculated using self-reported body height and weight.

2.3. Food Choice Values

Food choice values were assessed by the Japanese version of the food choice values scale. First, the original English version of the food choice values scale [5] was translated into Japanese by a member of the research team (consisting of doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers in nutritional epidemiology) with a high level of English proficiency. Second, back translation was conducted by another member of the research team. A researcher with expertise in nutritional epidemiology and eating behaviors oversaw the translation process and approved the Japanese version and its back-translated version. The backward translations were then reviewed by researchers involved in the development and validation of the original English version of the food choice values scale [5]. Furthermore, the forward and backward translations were reviewed by an independent person who is fluent in both English and Japanese. Based on their feedback, relevant modifications were made such that the translated version better reflected the original scale.

The food choice values scale is a 25-item, self-administered questionnaire measuring eight factors of food choice values: accessibility, convenience, health/weight control, tradition, sensory appeal, organic, comfort, and safety [5]. The validity of the original English version has been described elsewhere [5]. Participants were asked to answer how important each item is when deciding what foods to buy or eat on a daily basis. The possible responses, based on a Likert scale, ranged from 1 to 5 (1: not at all, 2: a little, 3: moderately, 4: quite a bit, and 5: very). The score for each factor was calculated by the sum of the scores divided by the number of items (4 items for organic and 3 items for the other factors), with possible scores ranging from 1 to 5. In the present study population, the Cronbach’s alpha for the assessment of internal consistency was 0.69 for accessibility, 0.87 for convenience, 0.82 for health/weight control, 0.69 for tradition, 0.61 for sensory appeal, 0.85 for organic, 0.74 for comfort, and 0.78 for safety, which was comparable to observations in previous studies (range: 0.54 to 0.89) [5,12].

2.4. Food Literacy

In this study, food literacy was characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors. This was based on the most widely used description of food literacy: “a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviors required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat food to meet needs and determine intake” [10].

2.4.1. Nutrition Knowledge

To assess nutrition knowledge, we used the Japanese general nutrition knowledge questionnaire (JGNKQ) [27]. As details of the structure, validity, and reliability of the JGNKQ are available elsewhere [27], only a brief description is provided here. Originally, the JGNKQ was a 147-item, self-administered questionnaire consisting of 5 sections: dietary recommendations, sources of nutrients, choosing everyday foods, diet-disease relationships, and reading a food label. The JGNKQ used in this study is a 143-item version in which 4 items with a very low prevalence of correct answers in the original version were removed. For each item, the correct response was assigned 1 point, whereas an incorrect or missing response was assigned 0 point. Thus, the possible total score ranged from 0 to 143, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of nutrition knowledge. In the present study population, the Cronbach’s alpha for the 143 items was 0.96, which was comparable to that observed in the development process of the JGNKQ (0.95) [27].

2.4.2. Cooking and Food Skills

Cooking skills and food skills were assessed by the Japanese version of the English scale for cooking and food skills [28]. The development process of the Japanese scale was similar to that for the food choice values scale described above; thus, the final back-translated version was reviewed by researchers involved in the development and validation of the original English version [28].

The cooking and food skills scale is a self-administered questionnaire, which consists of 14 questions on the former and 19 questions on the latter [28]. Questions on cooking skills ask about cooking methods and food preparation techniques, whereas those on food skills ask about meal planning and preparation, shopping, budgeting, resourcefulness, and label reading/consumer awareness. The validity of the original English version has been described elsewhere [28]. Based on a 7-point Likert scale, participants were asked to rate how well they felt they performed each of the skills described (1: very poor, 7: very good). An option of “never/rarely do it” was also available for participants who considered that a skill is not used; a score of zero was assigned when this response was selected. The scores of cooking skills and food skills were calculated as the sum of all the items, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 98 for the former and from 0 to 133 for the latter. In the present study population, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for the 14 cooking skill items and 0.96 for the 19 food skill items, which was higher than those observed in previous studies (range: 0.78 to 0.94) [28].

2.4.3. Eating Behaviors

Eating behaviors were assessed by the Japanese version of the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (AEBQ) prepared based on the original English version [29]. The development process of the Japanese AEBQ was similar to that for the food choice values scale described above; thus, the final back-translated version was reviewed by researchers involved in the development and validation of the original English version [29].

The AEBQ is a 35-item, self-administered questionnaire, measuring 4 food approach scales, namely hunger (5 items), food responsiveness (4 items), emotional overeating (5 items), and enjoyment of food (3 items), as well as 4 food avoidance scales, namely satiety responsiveness (4 items), emotional undereating (5 items), food fussiness (5 items), and slowness in eating (4 items) [29]. The validity of the original English version has been described elsewhere [29]. Item responses were rated based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, and a mean score was calculated for each scale (possible score ranging from 1 to 5). In the present study population, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.69 for hunger, 0.68 for food responsiveness, 0.86 for emotional overeating, 0.87 for enjoyment of food, 0.68 for satiety responsiveness, 0.89 for emotional undereating, 0.79 for food fussiness, and 0.65 for slowness in eating, which was, except for slowness in eating, comparable to those observed in previous studies (range: 0.67 to 0.97) [29,30,31,32,33].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between food choice values and food literacy (characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors). Differences in these variables between sex and across age categories (19–39, 40–59, and 60–80 years) were examined based on an independent t-test and analysis of variance (followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test), respectively. Associations of food choice values and food literacy with BMI were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients. These associations were also examined using BMI categories (≤18.5, >18.5 to <25, and ≥25 kg/m2), but the general impressions were similar to those obtained from correlation analyses; thus, we decided to present only correlation analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We considered two-tailed p values <0.05 statistically significant.

3. Results

The present analysis included 2231 Japanese adults (1068 males and 1163 females aged 19–80 years) with a mean age of 50 years (Table 1). The mean BMI (kg/m2) was 23.7 (standard deviation: 3.3) for males and 22.3 (standard deviation: 3.5) for females.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population 1.

| Variable | All (n = 2231) | Male (n = 1068) | Female (n = 1163) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.2 ± 17.3 | 50.4 ± 17.2 | 50.0 ± 17.5 |

| Body height (cm) 2 | 162.6 ± 8.9 | 169.4 ± 6.3 | 156.3 ± 5.9 |

| Body weight (kg) 2 | 60.9 ± 12.1 | 68.0 ± 10.9 | 54.4 ± 9.0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) 3 | 22.9 ± 3.5 | 23.7 ± 3.3 | 22.3 ± 3.5 |

1 Values are means ± standard deviations. 2 Based on self-report. 3 Calculated using self-reported body height and weight.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for food choice values and food literacy variables (nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors). For food choice values (maximum score: 5), the highest mean score was observed in safety (3.32), followed by sensory apparel (3.28) and accessibility (3.19), whereas the lowest mean score was observed in tradition (2.09). The mean score of nutrition knowledge was 70.2 (maximum score: 143), whereas the mean score of cooking and food skills was 43.3 (maximum score: 98) and 62.5 (maximum score: 133), respectively. Among eating behaviors (maximum score: 5), the highest mean score was observed in enjoyment of food (4.02), whereas the lowest mean score was observed in emotional overeating (2.37).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of food choice values and food literacy variables characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors (n = 2231) 1.

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Food choice values | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessibility (1) | 3.19 ± 0.78 | --- | ||||||||||||||||||

| Convenience (2) | 3.09 ± 0.85 | 0.55 | --- | |||||||||||||||||

| Health/weight control (3) | 2.82 ± 0.91 | 0.33 | 0.39 | --- | ||||||||||||||||

| Tradition (4) | 2.09 ± 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.35 | --- | |||||||||||||||

| Sensory appeal (5) | 3.28 ± 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.32 | --- | ||||||||||||||

| Organic (6) | 2.95 ± 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.40 | --- | |||||||||||||

| Comfort (7) | 2.33 ± 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.43 | --- | ||||||||||||

| Safety (8) | 3.32 ± 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.81 | 0.39 | --- | |||||||||||

| Nutrition knowledge (9) | 70.2 ± 24.6 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.24 | --- | ||||||||||

| Cooking and food skills | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cooking skills (10) | 43.3 ± 26.0 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.34 | --- | |||||||||

| Food skills (11) | 62.5 ± 34.6 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.84 | --- | ||||||||

| Eating behaviors | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hunger (12) | 2.77 ± 0.70 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | --- | |||||||

| Food responsiveness (13) | 2.74 ± 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.54 | --- | ||||||

| Emotional overeating (14) | 2.37 ± 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.43 | --- | |||||

| Enjoyment of food (15) | 4.02 ± 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.19 | --- | ||||

| Satiety responsiveness (16) | 2.59 ± 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.18 | --- | |||

| Emotional undereating (17) | 2.73 ± 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.30 | --- | ||

| Food fussiness (18) | 2.59 ± 0.78 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.19 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.16 | −0.23 | −0.23 | −0.06 | −0.23 | 0.02 | −0.38 | 0.16 | 0.04 | --- | |

| Slowness in eating (19) | 2.57 ± 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.15 | −0.05 | --- |

SD, standard deviation. 1 Possible scores range from 1 to 5 for each of the food choice values and eating behaviors, from 0 to 143 for nutrition knowledge, from 0 to 98 for cooking skills, and from 0 to 133 for food skills. In this sample size (n = 2231), Pearson correlation coefficients are statistically significant when values are greater than 0.0823 or less than −0.0823 at the level of p < 0.0001 (marked in yellow), greater than 0.0696 or less than −0.0696 at the level of p < 0.001 (marked in pink), greater than 0.0545 or less than −0.0545 at the level of p < 0.01 (marked in blue), and greater than 0.0415 or less than −0.0415 at the level of p < 0.05 (marked in orange).

Pearson correlation coefficients between these variables are also shown in Table 2. The eight food choice value scores were modestly and positively correlated with each other (>0.30), with a few exceptions (between accessibility and tradition and between convenience and tradition). The highest correlation was 0.81 between organic and safety scores. Nutrition knowledge was modesty and positively correlated with both cooking and food skills (0.34 and 0.36, respectively), whereas its correlations with each of the food choice values (0.11 to 0.27) and eating behaviors (−0.16 to 0.12) were generally weak.

There was a strong correlation between cooking and food skills (0.84). Cooking and food skills were, in general, modestly correlated with each of the food choice values (0.12 to 0.41). Conversely, the correlations between cooking and food skills and each of the eating behavior scores were generally weak (−0.23 to 0.19).

The correlations between eating behavior scores varied. Positive and modest correlations were observed between the food approach scales, i.e., hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, and enjoyment of food (0.19 to 0.54). Positive and modest correlations were also observed between some food avoidance scales (0.30 between satiety responsiveness and emotional undereating; 0.28 between satiety responsiveness and slowness in eating). There was a modest and inverse correlation between enjoyment of food and food fussiness (−0.38). Other correlations were rather weak (−0.18 to 0.21). The correlations between each eating behavior and each food choice value were also rather weak (−0.16 to 0.26). When correlation coefficients were calculated for males (Table S1) and females (Table S2) separately, the general interpretation and conclusion were not altered materially.

3.2. Association with Sex and Age

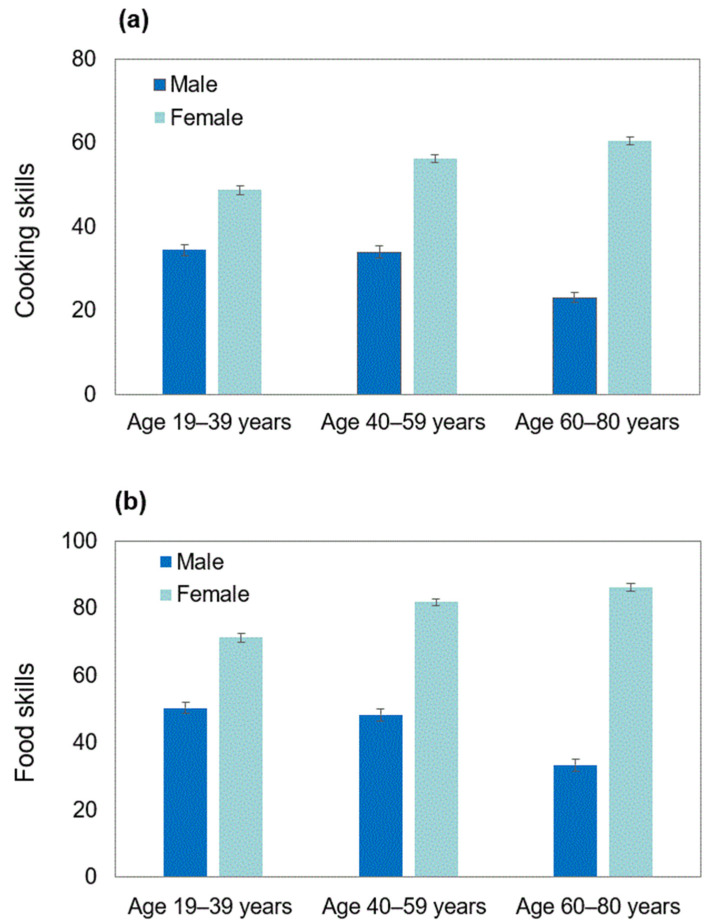

Table 3 shows food choice values, nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors according to sex and age categories. Compared to males, females had high mean values of all the scores examined, except for food fussiness. These sex differences were also observed when analyses were stratified by three age categories or BMI tertiles (data not shown). Age was associated with all the food choice value scores, except for health/weight control, with low scores for accessibility, convenience, sensory appeal, and comfort and high scores for tradition, organic, and safety observed in adults aged 60–80 years compared with those aged 19–39 years, those aged 40–59 years, or both. Nutrition knowledge was higher in adults aged 19–39 years and 40–59 years than in those aged 60–80 years, whereas cooking and food skills were higher in adults aged 40–59 years than in the other age groups. For eating behaviors, all the food approach scales (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, and enjoyment of food) were lower in the oldest age group. Conversely, age was not associated with the food avoidance scales (satiety responsiveness, emotional undereating, and food fussiness), except for a higher score of slowness in eating in the oldest age group. These age differences were also observed when analyses were stratified by sex or BMI tertiles (data not shown), except for food and cooking skills in sex-stratified analyses. As shown in Figure 1, both cooking and food skill scores were inversely associated with age in males, whereas these scores were positively associated with age in females.

Table 3.

Food choice values and food literacy variables characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors according to sex and age categories (n = 2231) 1.

| Variable | Male (n = 1068) |

Female (n = 1163) |

p Value for Sex (t-Test) |

Age 19–39 Years (n = 707) |

Age 40–59 Years (n = 751) |

Age 60–80 Years (n = 773) |

p Value for Age Categories (ANOVA) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food choice values | |||||||

| Accessibility | 3.06 ± 0.84 | 3.32 ± 0.71 | <0.0001 | 3.34 ± 0.75 a | 3.18 ± 0.78 b | 3.07 ± 0.80 c | <0.0001 |

| Convenience | 2.94 ± 0.91 | 3.23 ± 0.76 | <0.0001 | 3.29 ± 0.82 a | 3.09 ± 0.85 b | 2.89 ± 0.83 c | <0.0001 |

| Health/weight control | 2.67 ± 0.95 | 2.97 ± 0.84 | <0.0001 | 2.84 ± 0.94 | 2.83 ± 0.88 | 2.80 ± 0.90 | 0.60 |

| Tradition | 1.98 ± 0.75 | 2.19 ± 0.74 | <0.0001 | 1.94 ± 0.73 a | 2.09 ± 0.75 b | 2.23 ± 0.76 c | <0.0001 |

| Sensory appeal | 3.17 ± 0.73 | 3.38 ± 0.65 | <0.0001 | 3.39 ± 0.68 a | 3.30 ± 0.68 b | 3.16 ± 0.71 c | <0.0001 |

| Organic | 2.72 ± 0.87 | 3.16 ± 0.76 | <0.0001 | 2.73 ± 0.77 a | 2.95 ± 0.82 b | 3.15 ± 0.88 c | <0.0001 |

| Comfort | 2.19 ± 0.82 | 2.45 ± 0.79 | <0.0001 | 2.40 ± 0.84 a | 2.36 ± 0.81 a | 2.23 ± 0.79 b | <0.0001 |

| Safety | 3.14 ± 0.95 | 3.48 ± 0.82 | <0.0001 | 3.15 ± 0.89 a | 3.31 ± 0.88 b | 3.47 ± 0.90 c | <0.0001 |

| Nutrition knowledge | 63.9 ± 25.8 | 76.0 ± 21.8 | <0.0001 | 72.4 ± 23.2 a | 71.3 ± 25.0 a | 67.2 ± 25.2 b | 0.0001 |

| Cooking and food skills | |||||||

| Cooking skills | 30.3 ± 25.9 | 55.2 ± 19.5 | <0.0001 | 42.1 ± 23.3 a | 45.5 ± 25.7 b | 42.2 ± 28.3 a | 0.02 |

| Food skills | 43.6 ± 34.1 | 79.8 ± 24.4 | <0.0001 | 61.4 ± 30.6 a | 65.7 ± 32.8 b | 60.3 ± 39.2 a | 0.005 |

| Eating behaviors | |||||||

| Hunger | 2.67 ± 0.66 | 2.87 ± 0.72 | <0.0001 | 2.92 ± 0.71 a | 2.85 ± 0.68 a | 2.57 ± 0.66 b | <0.0001 |

| Food responsiveness | 2.58 ± 0.64 | 2.88 ± 0.67 | <0.0001 | 2.93 ± 0.72 a | 2.76 ± 0.64 b | 2.53 ± 0.60 c | <0.0001 |

| Emotional overeating | 2.24 ± 0.77 | 2.48 ± 0.80 | <0.0001 | 2.48 ± 0.87 a | 2.42 ± 0.80 a | 2.22 ± 0.69 b | <0.0001 |

| Enjoyment of food | 3.94 ± 0.76 | 4.09 ± 0.72 | <0.0001 | 4.14 ± 0.77 a | 4.01 ± 0.72 b | 3.90 ± 0.71 c | <0.0001 |

| Satiety responsiveness | 2.46 ± 0.66 | 2.72 ± 0.72 | <0.0001 | 2.59 ± 0.74 | 2.60 ± 0.69 | 2.59 ± 0.68 | 0.89 |

| Emotional undereating | 2.56 ± 0.90 | 2.87 ± 0.80 | <0.0001 | 2.67 ± 0.87 | 2.76 ± 0.86 | 2.74 ± 0.86 | 0.14 |

| Food fussiness | 2.63 ± 0.78 | 2.54 ± 0.77 | 0.0006 | 2.60 ± 0.79 | 2.55 ± 0.79 | 2.61 ± 0.74 | 0.21 |

| Slowness in eating | 2.44 ± 0.72 | 2.69 ± 0.70 | <0.0001 | 2.55 ± 0.77 a | 2.48 ± 0.68 a | 2.69 ± 0.69 b | <0.0001 |

ANOVA, analysis of variance. 1 Values are means ± standard deviations. Possible scores range from 1 to 5 for each of the food choice values and eating behaviors, from 0 to 143 for nutrition knowledge, from 0 to 98 for cooking skills, and from 0 to 133 for food skills. 2 When the overall p from ANOVA was <0.05, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed; mean values within a row with unlike superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Cooking skills (a) and food skills (b) according to age category in each sex. Values are means ± standard errors. The possible score is 0 to 98 for cooking skills and 0 to 133 for food skills. The number of males is 332, 359, and 377 for age 19–39, 40–59, and 60–80 years, respectively. The number of females is 375, 392, and 396 for age 19–39, 40–59, and 60–80 years, respectively. In males, both cooking and food skills in the 60–80-year group are significantly different from the two other age groups (p < 0.05 by Bonferroni’s post hoc test). In females, both cooking and food skills are significantly different between three age groups (p < 0.05 by Bonferroni’s post hoc test).

3.3. Association with BMI

Table 4 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients of BMI with each of the food choice values, nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors. In the total sample, the correlations for food choice values, nutrition knowledge, and cooking and food skills were quite weak (−0.08 to 0.11). The correlations for eating behavior scores were also not strong, ranging from −0.19 (satiety responsiveness) to 0.21 (emotional overeating). Analyses stratified by sex or age categories did not change the results materially.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients of body mass index with each of the food choice values and food literacy variables characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors 1.

| Variable | All (n = 2231) |

Male (n = 1068) |

Female (n = 1163) |

Age 19–39 Years (n = 707) |

Age 40–59 Years (n = 751) |

Age 60–80 Years (n = 773) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food choice values | ||||||

| Accessibility | −0.08 *** | −0.07 * | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.08 * |

| Convenience | −0.05 * | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Health/weight control | 0.11 **** | 0.15 **** | 0.16 **** | 0.12 ** | 0.08 * | 0.15 **** |

| Tradition | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 ** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Sensory appeal | −0.04 * | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| Organic | −0.07 *** | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.11 ** | −0.10 ** |

| Comfort | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.07 * |

| Safety | −0.07 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.09 * | −0.11 ** |

| Nutrition knowledge | −0.02 | 0.06 * | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| Cooking and food skills | ||||||

| Cooking skills | −0.05 * | 0.07 * | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.08 * |

| Food skills | −0.08 *** | 0.07 * | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.11 ** | −0.09 * |

| Eating behaviors | ||||||

| Hunger | −0.03 | 0.10 *** | −0.09 ** | −0.08 * | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Food responsiveness | 0.06 ** | 0.16 **** | 0.06 * | 0.04 | 0.15 **** | 0.06 |

| Emotional overeating | 0.21 **** | 0.25 **** | 0.26 **** | 0.20 **** | 0.26 **** | 0.21 **** |

| Enjoyment of food | 0.08 *** | 0.15 **** | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.12 *** | 0.12 *** |

| Satiety responsiveness | −0.19 **** | −0.12 **** | −0.18 **** | −0.23 **** | −0.17 **** | −0.16 **** |

| Emotional undereating | −0.08 *** | 0.01 | −0.09 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.03 |

| Food fussiness | −0.02 | −0.06 * | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| Slowness in eating | −0.18 **** | −0.17 **** | −0.12 **** | −0.23 **** | −0.16 **** | −0.15 **** |

1 Body mass index (kg/m2) was calculated as self-reported weight (kg) divided by the square of self-reported height (m). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive report on food choice values and food literacy (nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors) in Japanese adults. Consistent with previous Western studies using the same [12,13] or similar [14] scales of food choice values, the three most important values were safety, sensory appeal, and accessibility. The mean score and standard deviation of nutrition knowledge in this study were astonishingly similar to those observed in a previous Japanese study (mean: 69.3; standard deviation: 23.7) [34]. Our mean estimate of cooking skills and food skills was lower and higher, respectively, than that in a nationally representative sample of the island of Ireland (47.8 and 45.8, respectively) [28]. Finally, the mean of eating behavior scores was generally similar to that reported in previous studies [29,30,31,32,33], particularly in that the highest score was obtained for enjoyment of food. These basic findings confirm the validity of the measures in the present study.

The correlations between each of the food choice values [5,12] and between each of the eating behaviors [29,30,31,32,33] were generally similar to those reported in previous studies. The strong correlation between cooking and food skills observed here is consistent with the results of previous studies [28,35]. The present study also found modest and positive associations of cooking and food skills with nutrition knowledge, which is plausible. However, as we are unaware of previous studies in this regard, further research is needed.

We found that females had higher means of food choice values [17,18], nutrition knowledge [34,36,37], and cooking and food skills [35,38], all of which is consistent with several Western studies. These findings may reflect that women still have the main responsibility for cooking and probably grocery shopping in many households in Japan [39]. A study also suggested that women tend to be exposed to stronger sociocultural norms for body shape [40]. These factors may lead to greater involvement and preoccupation with food among women [19]. For eating behaviors, sex differences have not been extensively examined using the same questionnaire. However, in a French-speaking Canadian population, emotional overeating, satiety responsiveness, and emotional undereating were higher in females than in males [32], which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

Generally, previous studies [14,19,41] have suggested that older individuals tend to value more “long-term-oriented” motives (e.g., health/weight control, organic, and safety), whereas younger individuals tend to emphasize more “short-term-oriented” motives (e.g., accessibility, convenience, and sensory appeal). We observed consistent associations. As suggested by Konttinen and colleagues, the emergence of diverse health problems and the phase of the life course (e.g., having children and more stabilized life and financial situation) are likely to contribute to more long-term and health-conscious orientation in middle-aged and older adults [19]. Nevertheless, we found no association between age and health/weight control in this study. The exact reason is unknown, but this may be due to higher health consciousness in younger individuals, lower health consciousness in older individuals, or both, as well as the general lean nature of the Japanese population. Further studies are warranted.

In this study, nutrition knowledge was higher in adults aged 19–39 years and 40–59 years than in those aged 60–80 years, although the difference was not large. The associations between nutrition knowledge and age varied in previous studies. For example, there was no significant association between nutrition knowledge and age in an analysis of Japanese adults aged 18–64 years (mean age 44 years) [34]. Conversely, nutrition knowledge was positively associated with age among Belgian women aged 18–39 years [42] and Australian adults aged 18–74 years (41% of participants aged 18–34 years) [36]. A study conducted in England showed that the youngest (18–34 years) and the oldest (≥65 years) age groups had a lower nutrition knowledge score than people in the middle years (35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years) [37]. Considering the differences in age range of the populations between studies, these observations do not necessarily conflict with the findings of the present study.

One of the most important findings in this study is that age was inversely associated with cooking and food skills in males, whereas the opposite was observed in females, in addition to much higher scores for both skills in females than in males. Similar findings with regard to cooking skills have been reported in a series of Japanese studies [39,43]. This may be explained by the fact that older males had limited opportunities to learn cooking and food skills because home economics classes were conducted only for females until 1993 in junior high schools and 1994 in high schools in Japan [44]. Additionally, older males (and older females) may tend to persist in a belief in gender roles ideology that dictates that men should work outside the home and women should do housework at home [39]. Conversely, the narrower gap between sex in food and cooking skills observed in younger age groups may suggest more opportunities to learn cooking and food skills for younger males in schools, as well as gender role ideology gradually becoming obsolete. In any case, future studies should carefully consider these sex and age differences in cooking and food skills.

For eating behaviors, we observed that all the food approach scales (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, and enjoyment of food) were lower in the oldest age group. Similar findings were reported in a study of 197 French-speaking Canadian adults, although only food responsiveness reached statistical significance [32]. Consistent with the Canadian study [32], we observed no association of age with the food avoidance scales (except for slowness in eating). The higher score of slowness in eating observed in the oldest age group does fit well with our previous observation that time spent eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner was longer in the oldest age group (60–79 years) than younger age groups (20–39 and 40–59 years) [26].

In this study, the correlations of food choice values, nutrition knowledge, and cooking and food skills with BMI were generally weak. This is consistent with a few reports in which the association of food choice values [18], cooking and food skills [35], and nutrition knowledge [42] with BMI or weight status was, if present, not strong. A number of studies have reported associations between eating behaviors assessed by AEBQ and BMI (or weight status) [29,30,31,32,33]. The most consistent findings are a positive association for emotional overeating [29,30,32,33] and inverse associations for satiety responsiveness [29,30,31,33] and for slowness in eating [29,30,31,32,33], which is consistent with observations of the present study.

The strengths of the present study include the simultaneous focus on food choice values and food literacy (nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors) and the use of well-established scales for these variables (particularly nutrition knowledge), as well as a large nationwide sample with almost the equal proportions for sex and age categories. However, there are also several limitations. First, although sampling was conducted so that regional differences in population proportion are reflected, the study population is not a nationally representative sample of the general Japanese population but rather volunteers. It is conceivable that the participants were more representative of health-conscious individuals. Nevertheless, an analysis conducted in the context of the MINNADE study [26], from which our participants were recruited (with a response rate of 75%), showed that the distribution of annual household income was similar to that in a national representative sample, although education level was somewhat higher. Furthermore, mean (standard deviation) values of body height, body weight, and BMI in the present participants were also similar to those in a national representative sample aged ≥20 years (males: 167.6 (7.0) cm, 67.0 (11.5) kg, and 23.8 (3.4) kg/m2, respectively; females: 154.1 (6.9) cm, 53.6 (9.4) kg, and 22.6 (3.7) kg/m2, respectively) [45]. Thus, there may be no strong reason for considering that the present participants largely differ from the general Japanese population. Nevertheless, we could not compare basic characteristics between study participants and individuals who declined to participate in this study (both are participants in MINNADE study) because the use of data obtained within the MINNADE study is not permitted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan [26]. Further research in a more representative sample is thus warranted.

Second, the present analysis could not take any socioeconomic variables into account because of a lack of information. However, in a previous study of 1165 Japanese adults aged 18–64 years, nutrition knowledge was not significantly related to education or household income [34]. It is generally acknowledged that education is a strong determinant of future employment and income, and that knowledge and skills are attained through education, affecting a person’s cognitive functioning [46]. Previous Western studies have also indicated that the associations of age and sex with food choice values [17,18], except for values related to price cheapness of food [19], as well as cooking and food skills [35,38], were stronger than those for education, whereas nutrition knowledge was strongly associated with education [36,37,42]. Taken together, it is unlikely that socioeconomic factors entirely explain the findings observed here. Nevertheless, future research should incorporate the assessment of socioeconomic variables to obtain more comprehensive pictures.

Third, we calculated BMI based on self-reported body weight and height, which might be biased. However, previous studies have shown that BMI calculated from self-reported weight and height is highly correlated with BMI calculated from measured values [47,48]. It is thus considered that BMI calculated from self-reported weight and height is a reliable measure, at least for use in correlation analysis.

Finally, during the development process of the Japanese versions of assessment tools for food choice values, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors, we did not take into account cultural differences between Japan and Western countries. This was because our main intention was to maximize the comparability of our Japanese versions with the original English versions. Consequently, the tools may not be optimal for use in the Japanese population. However, it should be noted that the internal consistency of all the scores, except for slowness in eating, was comparable to that observed in previous studies, as mentioned above. Additionally, the associations observed here are not only plausible but also generally comparable with previous Western studies, which confirms, to a certain extent, the validity of the measures in the present study. Nevertheless, future refinement or modification of the assessment tools specially designed for the Japanese population would be of interest.

In conclusion, we provided comprehensive pictures of food choice values (accessibility, convenience, health/weight control, tradition, sensory appeal, organic, comfort, and safety) and food literacy, which was characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, enjoyment of food, satiety responsiveness, emotional undereating, food fussiness, and slowness in eating) in a large nationwide sample of Japanese adults aged 19–80 years. The major findings are as follows: compared to males, females had high means of all the variables, except for food fussiness; compared to participants aged 19–39 and/or 40–59 years, those aged 60–80 years had low means of some food choice values (accessibility, convenience, sensory appeal, and comfort), nutrition knowledge, and all the food approach behaviors (hunger, food responsiveness, emotional overeating, and enjoyment of food), as well as high means of other food choice values (tradition, organic, and safety) and slowness in eating; age was inversely associated with cooking and food skills in males, whereas the opposite was observed in females; the associations with BMI were generally weak. These observations in Japanese adults are generally consistent with those in Western countries, which is interesting, considering the widespread perception of the Japanese diet as healthful; further research is warranted. The present findings serve as both a reference and an indication for future research on food choice values and food literacy in Japan.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research dietitians who conducted the data collection: Tamotsu Noshiro, Ikuko Kato, Yoshie Awa, Erika Takayama, Mari Sakurai, Mihoko Yanase, Masae Kato, Mihoko Furukawa, Yuna Nodera, Kazue Fukushi, Miwako Onodera, Yoshie Sato, Megumi Yoshida, Masako Shimooka, Kaori Takahashi, and Fuki Kudo (Hokkaido); Yumiko Sato, Yutaka Shojiguchi, Kazunori Kimoto, Saori Kikuchi, Megumi Maeta, Mayumi Sugawara, Shinogu Muraoka, Kanako Takahashi, Noriko Suzuki, Yoko Fujihira, and Megumi Onodera (Iwate); Yukiko Takahashi, Kaoru Honda, Chie Yamada, Miki Sato, Katsue Watanabe, Akemi Konno, and Reina Kato (Miyagi); Akiko Sato, Hiromi Kawaguchi, Miyuki Awano, Chigusa Miyake, Ayako Konno, Ayumi Goto, Shizuko Taira, Yuka Takeda, Akiko Matsunaga, Nao Konta, Yumi Miura, Satoshi Numazawa, Chiemi Ito, Sachie Yokosawa, Manami Endo, and Hiromi Seki (Yamagata); Yoko Tsukada, Tomoko Oga, Satoko Fujita, Hitomi Sonobe, Hanayo Kadoi, Toshie Nakayama, Hiromi Takasawa, Yoko Ichikawa, Yuko Takano, Junko Hanzawa, Kiyomi Seki, Emi Kamoshita, Yuri Kawakami, and Hisako Watahiki (Ibaraki); Reiko Ishii, Yoshiyuki Tatsuki, Daisuke Mogi, Akiko Nakamura, Suguru Yagi, Yumiko Furushima, Noriko Ogiwara, Kiyomi Kimura, Kinue Takahashi, Kikue Tomaru, Kana Tsukagoshi, Fumiko Fujiu, Kyoko Maehara, and Yuki Kobayashi (Gunma); Kaoru Goto, Yuka Inaba, Michiko Koresawa, Tomoko Tsuchida, Naoko Sakakibara, Fumika Shimoyama, Akiko Kato, Miki Hori, Rika Kurosaki, Hiroko Yamada, Hitomi Sasaki, Keiko Arai, Yuka Arai, Manami Honda, Akiko Utsumi, Asako Hamada, Keiko Sekine, Akiko Yamada, Mami Ono, Satoko Maruyama, Emiko Kajiwara, Taeko Takahashi, Hitomi Kawata, Satoru Arai, Ryoko Hirose, Madoka Ono, and Mihoko Ainai (Saitama); Masako Shinohara, Noriko Nakamura, Mitsuko Ito, Yuka Takahara, Minako Fukuda, Masae Ito, Yayoi Sueyoshi, Hiroko Shigeno, Tomohiro Murakami, Masako Kametani, Kyoko Wada, Mika Ueda, Jun Kouno, Hiroyo Yamaguchi, Mariko Oya, Junko Suegane, Yumiko Asai, Miyuki Ono, Mitsuko Uekusa, Chieko Sunada, Yumi Tanada, Mariko Shibata, Emi Tsukii, Kae Terayama, Hiroko Iwasaki, Keiko Yokoyama, Haruna Kayano, Kazuyo Shimota, Keiko Ifuku, and Keiko Honma (Chiba); Yoshiko Saito, Megumi Suzuki, Eiko Kobayashi, Yoshiko Katayama, Sonoko Yamaguchi, Tomoko Kita, Naoko Yuasa, Hitomi Okahashi, Shinobu Matsui, Yurina Arai, Sanae Togo, Eiko Horiguchi, Juri Sato, Takehiro Komatsu, Yumi Matsuura, Junko Higashi, Ayaka Nakashita, Takako Sakanashi, Yoko Kono, Naomi Nakazawa, and Yukiko Shibata (Tokyo); Machiko Tanaka, Ikue Sahara, Yasue Watanabe, Kanako Yoshijima, Yuko Harashima, Yoshiko Iba, Haruko Irisawa, Junko Inose, Reiko Okui, Taeko Endo, Mayuko Sakitsu, Ikuko Endo, Haruko Terada, Chiaki Nishikawa, Ai Yasudomi, Suzuyo Takeda, Kaori Shimizu, Mari Ikeda, Yuko Okamoto, Keiko Yamada, Fumiko Nemoto, Shinobu Katayama, Yuki Takakuwa, Michiru Goukon, Megumi Koike, Masae Kamiya, Takako Okada, Yayoi Hayashi, Etsuko Abe, Akiko Hamamoto, Kumiko Ono, Kazumi Takagi, Sachiko Ito, Yuki Kumagai, Noriko Ozaki, Haruka Sato, Hisae Takahashi, Masuko Komazaki, Akiko Nako, Tatehiro Inamoto, and Kimiyo Matsumoto (Kanagawa); Masako Koike, Reiko Kunimatsu, Keiko Kuribayashi, Hiroko Adachi, Yuri Shikama, Yurika Seida, Ryouko Ito, Satoko Kimura, Yoko Sato, Michiyo Nakamura, Hisako Kaneko, Hatsuyo Ikarashi, Mamiko Karo, Keiko Hirayama, Ikumi Torigoe, and Fumiko Gumizawa (Niigata); Natsuko Mizuguchi, Aki Sakai, Hisako Noguchi, Chie Tanabe, Yokako Osaki, Ikiko Kawasaki, Nobuko Yoshii, Yumiko Nishihara, Izumi Takahara, Mika Minato, Yuuki Okamoto, Yukiyo Sakai, Shitomi Nakamura, Kanako Kobayashi, Emi Hano, and Megumi Emori (Toyama); Kazumi Horiguchi, Michiyo Kubota, Naoya Mochizuki, Miyuki Yokokoji, Kazuko Koizumi, Megumi Ariizumi, Hozumi Kakishima, Mayumi Kawakubo, Chisato Nakajima, Yasuko Ishii, Yukie Shiogami, Yukiko Uchida, Ikuko Kayanuma, and Kikuyo Moriya (Yamanashi); Noriko Sumi, Noriko Takahashi, Kuniko Watanabe, Yoko Ido, Akiko Adachi, and Manami Tauchi (Gifu); Naoya Terada, Chisato Suwa, Toshihiro Tamori, Natsuko Osakabe, Toshiyuki Serizawa, Akiko Seki, Izumi Mochizuki, Nagako Matsui, Eiko Watanabe, Kyoko Yui, Yuki Murakami, Tomomi Iwasaki, and Tomoko Sugiyama (Shizuoka); Keiko Kawasumi, Masako Tanaka, Kayoko Ishida, Megumi Yamatani, Shihoko Yama, Miyuki Otono, Mie Kojima, Tamaki Kobayashi, Hiroe Komaki, Miki Yanagida, Yumiko Fukaya, Syoko Sawaki, Tomomi Ota, Yasuko Kito, Mei Tobinaga, Takashi Yasue, Kuniko Hatamoto, Toru Ono, Takako Minami, Akemi Kumazawa, Masami Kato, Miyuki Kondo, Kyoko Shimizu, Sayoko Tanaka, and Shizue Masuda (Aichi); Hiromi Ashida, Shintaro Hinaga, Yoshiko Shoji, Ryusuke Yamaguchi, Hiroka Morita, and Atsuko Nakabayashi (Mie); Erika Shioi, Sawa Mizukawa, Miwako Ohashi, Eriko Taniguchi, Yuri Mitsushima, Mariko Teraya, Kazuko Ogawa, Yoko Minami, Megumi Ito, Yasuhiro Morimoto, Shizuka Kurokawa, and Manami Hayashi (Kyoto); Yumiko Noutomi, Yoshiko Iwamoto, Junko Ikukawa, Shinobu Fujiwara, Tami Irei, Keiko Takata, Yasuka Tabuchi, Naoko Murayama, Kaori Maruyama, Hiromi Tashiro, Miki Tanaka, Miho Nomura, Shizuyo Umezawa, Minori Shintani, Ikuyo Maruishi, Atsuko Toyokawa, Rumi Kitada, Yuka Takashima, Eriko Nakatani, Wakana Tsujimoto, Yumi Koori, Emi Iwamoto, and Masumi Yamada (Osaka); Atsuko Konishi, Yoshiko Nakamori, Yumi Ikawa, Junko Shimizu, Mie Atsumi, Atsuko Fukuzaki, Akemi Yamamoto, Yasuko Inoue, Miyuki Nakahara, Reiko Fujii, Yumi Tanaka, Rika Miyachi, Mari Matsuyama, Ayana Honda, Tomoka Nakata, Miho Inagaki, Mikiyo Ueno, Mami Kamei, Kiyomi Kawachi, Yasuyo Hasegawa, and Masayo Fukumoto (Hyogo); Sachiyo Otani, Tomomi Sugimoto, Kanako Mizoguchi, Tomomi Shimada, Shima Takahashi, Yoshiko Okuno, Takahide Kijima, Masayo Ueda, Yuko Sakamoto, Hitoshi Matsuda, Yumie Shimizu, Rie Hataguchi, Junko Nohara, Yuko Sakakitani, Hatsuki Matsumoto, Sakiko Tanaka, Moe Yoshikawa, and Rena Yuki (Nara); Yurika Adachi, Akiko Notsu, Keiko Uzuki, Atsuko Umeda, Hiroko Nishio, Chikako Takeshita, and Sayuri Omoso (Tottori); Hiromi Watanabe, Nami Sakane, Nao Hino, Sakiko Sonoyama, Yukiko Katagiri, Kaori Nagami, Tsunemi Moriyama, and Yoshiko Kirihara (Shimane); Sachiko Terao, Akemi Inoue, Mieko Imanaka, Noriyuki Kubota, Sachiko Sugii, Yuri Fujiwara, and Tomoko Miyake (Okayama); Youko Fujii, Hiroko Tamura, Kimie Tanaka, Izumi Hase, Etsuko Kimura, Akiko Hamada, Tomoko Kawai, Masako Ogusu, and Emi Isomichi (Hiroshima); Kyoko Ueda, Atsuko Nakanishi, Tomoko Ishida, Nobuko Morishita, Hitomi Nakata, and Takako Yagi (Yamaguchi); Yuriko Doihara, Toyoko Kitadai, Hideyo Yamada, Mariko Nakamura, Nanako Honda, Eri Ikeuchi, Kayo Hashimoto, Azusa Onishi, and Manami Iwase (Tokushima); Machiko Ueda, Ayano Kamei, Reiko Motoie, Yoko Moriki, Nobumi Yoshida, and Kiyoko Kubo (Ehime); Kyoko Kaku, Emi Ibushi, Miho Otsuka, Kiyoko Katayama, Hisami Kumagai, Chizuru Shibata, Miki Hamachi, Yuko Hayashida, Akiko Matsuzaki, Mika Yoshioka, Yoshie Yanase, Yoshiko Yahagi, and Tomomi Ota (Fukuoka); Junko Kiyota, Hiromi Ide, Takako Fukushima, Shiho Tominaga, Satsuki Miyama, Yoko Okamura, Kayoko Kurahara, Tomomi Nagamori, Chika Shino, Akiko Taira, Yuki Kuwajima, and Miyuki Matsushita (Kumamoto); Miki Hamada, Kiyomi Aso, Toshie Eto, Mitsue Kodama, Miyoko Sato, Mutsuko Shuto, Yuko Soga, Taeko Nagami, Machiko Hirayama, Mika Moribe, Junko Yamamoto, Hideko Yoshioka, Yuko Kawano, Rika Matsuoka, and Satomi Sato (Oita); and Hisami Yamauchi, Satomi Moromi, Satoko Tomari, Kaoru Miyara, Chikako Murahama, Yukiko Furugen, Kana Awano, Hiromi Arakaki, Suzumi Uema, Yasuko Tomori, Nariko Mori, Ayako Iho, Michiru Hokama, Yasue Higa, and Chigusa Chibana (Okinawa). The authors would also like to thank the research team staff at the survey center (University of Tokyo): Tomoko Doi, Hitomi Fujihashi, Akiko Hara, Nana Kimoto, Nanako Koe, Eri Kudo, Fumie Maeda, Keika Mine, Akemi Nakahara, Hiroko Onodera, Hiroko Sato, Chifumi Shimomura, and Fusako Tanaka.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu14091899/s1, Table S1: Pearson correlation coefficients between food choice values and food literacy variables characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors in 1068 males, Table S2: Pearson correlation coefficients between food choice values and food literacy variables characterized by nutrition knowledge, cooking and food skills, and eating behaviors in 1163 females.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and N.S.; methodology, K.M., N.S., X.Y., R.T., M.M. and S.S.; software, K.M.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, K.M.; resources, K.M. and S.M.; data curation, K.M., N.S., X.Y., R.T., M.M. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, N.S., X.Y., R.T., M.M. and S.S.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, K.M.; project administration, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Medicine (protocol code: 12031; date of approval: 17 July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and from a parent or guardian for participants aged <20 years.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Medicine, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The questionnaires used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by a Challenging Research (Exploratory) grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K.M.; grant number: 18K19727). The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393:1958–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willett W., Rockstrom J., Loken B., Springmann M., Lang T., Vermeulen S., Garnett T., Tilman D., DeClerck F., Wood A., et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jinnette R., Narita A., Manning B., McNaughton S.A., Mathers J.C., Livingstone K.M. Does personalized nutrition advice improve dietary intake in healthy adults? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 2021;12:657–669. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ordovas J.M., Ferguson L.R., Tai E.S., Mathers J.C. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:k2173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyerly J.E., Reeve C.L. Development and validation of a measure of food choice values. Appetite. 2015;89:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furst T., Connors M., Bisogni C.A., Sobal J., Falk L.W. Food choice: A conceptual model of the process. Appetite. 1996;26:247–265. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truman E., Lane D., Elliott C. Defining food literacy: A scoping review. Appetite. 2017;116:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azevedo Perry E., Thomas H., Samra H.R., Edmonstone S., Davidson L., Faulkner A., Petermann L., Manafo E., Kirkpatrick S.I. Identifying attributes of food literacy: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:2406–2415. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amouzandeh C., Fingland D., Vidgen H.A. A scoping review of the validity, reliability and conceptual alignment of food literacy measures for adults. Nutrients. 2019;11:801. doi: 10.3390/nu11040801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidgen H.A., Gallegos D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite. 2014;76:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaitkeviciute R., Ball L.E., Harris N. The relationship between food literacy and dietary intake in adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:649–658. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyerly J.E. Ph.D. Thesis. University of North Carolina at Charlotte; Charlotte, NC, USA: 2015. Associations between Food Choice Values of Parental Guardians, Socioeconomic Status, Home Food Availability, and Child Dietary Intake. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steptoe A., Pollard T.M., Wardle J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite. 1995;25:267–284. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha L.M., Cabral D., de Moura A.P., Vaz de Almeida M.D. Application of the Food Choice Questionnaire across cultures: Systematic review of cross-cultural and single country studies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018;64:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescott J., Young O., O’Neill L., Yau N.J.N., Stevens R. Motives for food choice: A comparison of consumers from Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia and New Zealand. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002;13:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(02)00010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetherill M.S., Williams M.B., Hartwell M.L., Salvatore A.L., Jacob T., Cannady T.K., Standridge J., Fox J., Spiegel J., Anderson N., et al. Food choice considerations among American Indians living in rural Oklahoma: The THRIVE study. Appetite. 2018;128:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konttinen H., Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S., Silventoinen K., Mannisto S., Haukkala A. Socio-economic disparities in the consumption of vegetables, fruit and energy-dense foods: The role of motive priorities. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:873–882. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schliemann D., Woodside J.V., Geaney F., Cardwell C., McKinley M.C., Perry I. Do socio-demographic and anthropometric characteristics predict food choice motives in an Irish working population? Br. J. Nutr. 2019;122:111–119. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konttinen H., Halmesvaara O., Fogelholm M., Saarijarvi H., Nevalainen J., Erkkola M. Sociodemographic differences in motives for food selection: Results from the LoCard cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021;18:71. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poelman M.P., Dijkstra S.C., Sponselee H., Kamphuis C.B.M., Battjes-Fries M.C.E., Gillebaart M., Seidell J.C. Towards the measurement of food literacy with respect to healthy eating: The development and validation of the self perceived food literacy scale among an adult sample in the Netherlands. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018;15:54. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0687-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park D., Park Y.K., Park C.Y., Choi M.K., Shin M.J. Development of a comprehensive food literacy measurement tool integrating the food system and sustainability. Nutrients. 2020;12:3300. doi: 10.3390/nu12113300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fingland D., Thompson C., Vidgen H.A. Measuring food literacy: Progressing the development of an International Food Literacy Survey using a content validity study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:1141. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murakami K., Livingstone M.B.E., Fujiwara A., Sasaki S. Application of the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and the Nutrient-Rich Food Index 9.3 for assessing overall diet quality in the Japanese context: Different nutritional concerns from the US. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0228318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami K., Shinozaki N., Livingstone M.B.E., Fujiwara A., Asakura K., Masayasu S., Sasaki S. Characterisation of breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks in the Japanese context: An exploratory cross-sectional analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:689–701. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugimoto M., Murakami K., Fujiwara A., Asakura K., Masayasu S., Sasaki S. Association between diet-related greenhouse gas emissions and nutrient intake adequacy among Japanese adults. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0240803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami K., Livingstone M.B.E., Masayasu S., Sasaki S. Eating patterns in a nationwide sample of Japanese aged 1–79 y from MINNADE study: Eating frequency, clock time for eating, time spent on eating and variability of eating patterns. Public Health Nutr. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M., Tanaka R., Ikemoto S. Validity and reliability of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Japanese adults. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2017;63:298–305. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.63.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavelle F., McGowan L., Hollywood L., Surgenor D., McCloat A., Mooney E., Caraher M., Raats M., Dean M. The development and validation of measures to assess cooking skills and food skills. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14:118. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0575-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunot C., Fildes A., Croker H., Llewellyn C.H., Wardle J., Beeken R.J. Appetitive traits and relationships with BMI in adults: Development of the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Appetite. 2016;105:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallan K.M., Fildes A., de la Piedad Garcia X., Drzezdzon J., Sampson M., Llewellyn C. Appetitive traits associated with higher and lower body mass index: Evaluating the validity of the adult eating behaviour questionnaire in an Australian sample. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017;14:130. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0587-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J., Sun S., Zickgraf H.F., Ellis J.M., Fan X. Assessing appetitive traits among Chinese young adults using the Adult Eating Behavior Questionnaire: Factor structure, gender invariance and latent mean differences, and associations with BMI. Assessment. 2021;28:877–889. doi: 10.1177/1073191119864642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob R., Tremblay A., Fildes A., Llewellyn C., Beeken R.J., Panahi S., Provencher V., Drapeau V. Validation of the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire adapted for the French-speaking Canadian population. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021;27:1163–1179. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunot-Alexander C., Arellano-Gomez L.P., Smith A.D., Kaufer-Horwitz M., Vasquez-Garibay E.M., Romero-Velarde E., Fildes A., Croker H., Llewellyn C.H., Beeken R.J. Examining the validity and consistency of the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire-Espanol (AEBQ-Esp) and its relationship to BMI in a Mexican population. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021;27:651–663. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto M., Ishige N., Sakamoto A., Saito A., Ikemoto S. Nutrition knowledge related to breakfast skipping among Japanese adults aged 18–64 years: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:1029–1036. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavelle F., Bucher T., Dean M., Brown H.M., Rollo M.E., Collins C.E. Diet quality is more strongly related to food skills rather than cooking skills confidence: Results from a national cross-sectional survey. Nutr. Diet. 2020;77:112–120. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrie G.A., Coveney J., Cox D. Exploring nutrition knowledge and the demographic variation in knowledge levels in an Australian community sample. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:1365–1371. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parmenter K., Waller J., Wardle J. Demographic variation in nutrition knowledge in England. Health Educ. Res. 2000;15:163–174. doi: 10.1093/her/15.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGowan L., Pot G.K., Stephen A.M., Lavelle F., Spence M., Raats M., Hollywood L., McDowell D., McCloat A., Mooney E., et al. The influence of socio-demographic, psychological and knowledge-related variables alongside perceived cooking and food skills abilities in the prediction of diet quality in adults: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016;13:111. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0440-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tani Y., Fujiwara T., Kondo K. Cooking skills related to potential benefits for dietary behaviors and weight status among older Japanese men and women: A cross-sectional study from the JAGES. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020;17:82. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00986-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buote V.M., Wilson A.E., Strahan E.J., Gazzola S.B., Papps F. Setting the bar: Divergent sociocultural norms for women’s and men’s ideal appearance in real-world contexts. Body Image. 2011;8:322–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renner B., Sproesser G., Strohbach S., Schupp H.T. Why we eat what we eat. The Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS) Appetite. 2012;59:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Vriendt T., Matthys C., Verbeke W., Pynaert I., De Henauw S. Determinants of nutrition knowledge in young and middle-aged Belgian women and the association with their dietary behaviour. Appetite. 2009;52:788–792. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tani Y., Isumi A., Doi S., Fujiwara T. Associations of caregiver cooking skills with child dietary behaviors and weight status: Results from the A-CHILD study. Nutrients. 2021;13:4549. doi: 10.3390/nu13124549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Secretariat of the Round Table Conference on International Educational Cooperation, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. On the Educational Experience of Our Country: Home Economics Education. 2002. [(accessed on 27 February 2022)]. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chousa/kokusai/002/shiryou/020801ef.htm#top. (In Japanese)

- 45.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare National Health and Nutrition Survey 2017. [(accessed on 26 February 2022)];2018 Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/h29-houkoku.html. (In Japanese)

- 46.Galobardes B., Shaw M., Lawlor D.A., Lynch J.W., Smith G.D. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1) J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorber S.C., Tremblay M., Moher D., Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2007;8:307–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wada K., Tamakoshi K., Tsunekawa T., Otsuka R., Zhang H., Murata C., Nagasawa N., Matsushita K., Sugiura K., Yatsuya H., et al. Validity of self-reported height and weight in a Japanese workplace population. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2005;29:1093–1099. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Medicine, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The questionnaires used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.