Abstract

Xylosma G. Forst. is a genus of plants belonging to the Salicaceae family with intertropical distribution in America, Asia, and Oceania. Of the 100 accepted species, 22 are under some level of conservation risk. In this review, around 13 species of the genus used as medicinal plants were found, mainly in Central and South America, with a variety of uses, among which antimicrobial is the most common. There is published research in chemistry and pharmacological activity on around 15 of the genus species, centering in their antibacterial and fungicidal activity. Additionally, a variety of active phytochemicals have been isolated, the most representative of which are atraric acid, xylosmine and its derivatives, and velutinic acid. There is still ample field for the validation and evaluation of the activity of Xylosma extracts, particularly in species not yet studied, and concerning uses other than antimicrobial and for the identification and evaluation of their active compounds.

Keywords: Xylosma, ethnopharmacology, phytochemicals, Salicaceae, biological activity

1. Introduction

The use of medicinal plants is not exclusive to humans, but is also reported in superior apes and other animal species [1,2]; it is therefore not surprising that humans have used medicinal plants since the earliest antiquity [3,4,5]. Until recently, the approach was purely empirical [6], but today, this knowledge is being validated and refined by modern research methodology that accelerates the generation of knowledge and its applications [7]. Today, natural products are an important source of new drugs and treatments, either directly or through chemical modifications [8].

In this article we performed a systematic review of the phytochemical composition, pharmacological, medical, and veterinary applications on the species in the genus, gathering the existing information in scientific literature about the ethnomedical knowledge, the active molecules identified and isolated from them, and the research studies that validate their potential efficacy. The objective of the study is to identify gaps in the knowledge about the genus and find study lines that may guide future research.

2. Genus

The Salicaceae Mirb. family, to which the Xylosma genus belongs, is famously medicinal because of the Salix genus (willow), the pharmacological properties of which were already used in ancient Mesopotamia, and were extolled in the first century CE, in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica [8,9].

The Xylosma genus is one of the 55 that conform the Salicaceae family [9], and is composed of 100 accepted species [10], although others list 45 [11]. Until recently, it was included in the now-deprecated Flacourtiaceae family, but has now been assigned to Salicaceae [12]. The name stems from the Greek words for “wood” and “smell” in reference to odoriferous quality of the wood of some Pacific species of the genus [11], presumably X. orbiculata and X. suaveolens used to perfume coconut oil by early South Pacific inhabitants [13]. At first, the genus was named Myroxylon (myrrh-wood) but was changed to Xylosma to avoid confusion with South American balsam trees [14]. Not all species in the genus are sweet-smelling: X. maidenii timber, for example, is foul-smelling. Xylosma species are described in detail by Woodson et al. [15].

In shrubs or small trees, often with axillary spines, the branchlets commonly lenticellate. Leaves alternate, sometimes borne in fascicles, usually short-petiolate, estipulate, the blade is often ±coriaceous, usually glandular-dentate, penninerved, rarely entire-margined, without pellucid-glands. Inflorescences axillary, fasciculate or contracted-racemose, and are rarely racemose. Flowers are small, dioecious, or rarely polygamous; pedicels are articulated above the base, and the bracts are minute; sepals 4-5(-6), imbricate, usually scale-like, slightly connate at the base, often ciliolate along the margins, usually persistent; petals none; stamens ∞ (8–35 in Panamanian spp.), usually surrounded by an annular or glandular, fleshy disc, the filaments free, filiform, short- to usually long-exserted, the anthers minute, basifixed, extrose, longitudinally dehiscent; ovary sessile, inserted on an annular disc, 1-locular, with 2–3, rarely 4–6, parietal placentas, each placenta with 2, sometimes 4–6, ovules, the style entire or ±divided, sometimes very short, the stigmas scarcely dilated to dilated; rudimentary ovary wanting in male flowers. Fruits baccate, rather dry, indehiscent, surmounted by the persistent style, the pericarp rather thin-coriaceous, the seeds 2–8, +angular by mutual pressure, the testa thin; endosperm copious; embryo large, the cotyledons broad.

Species in the Xylosma genus have several uses and properties, from landscaping (Xylosma congesta (Lour.) Merr.), beekeeping (Xylosma venosa N. E. Br. [16]), timber, firewood, to food and medicine; notably Xylosma longifolia Clos. Due to the thorns that some species of the genus have, common names such as “do not touch me” (Xylosma coriacea (Poit.) Eichler) or “deer antlers” (Xylosma spiculifera (Tul.) Triana and Planch.) are used for them [17]. Eleven species of the genus, particularly Xylosma vincentii Guillaumin, are known to be nickel hyperaccumulators [18,19] which presents potential for phytoremediation and phytomining [20].

3. Distribution and Localization

Species belonging to the Xylosma genus are present in subtropical America, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Of the 100 species listed in the genus [10], 61 are found in America, 8 in Asia, and 31 in Oceania. Figure 1 shows examples of species of the genus. The map in Figure 2 shows the intertropical, and to a lesser extent, temperate, distribution of Xylosma species, by country.

Figure 1.

Xylosma flexuosa (Kunth) Hemsl. leaves and berries, left. Xylosma congesta (Lour.) Merr. inflorescence, right. Image sources: left, Public Domain (CC0); right, Miwasatosi, GDFL license.

Figure 2.

Worldwide Xylosma distribution, by country, after [10].

Of the 100 species of the genus, 7 are listed as vulnerable, 9 as endangered, and 6 as critically endangered. In total, 22% of the species in the genus are considered as species of concern [21]. This should be considered when evaluating potential industrial uses for these species.

4. Methodology

Published works—articles and patents—were searched in Dimensions [22] for bibliometric data, and in scientific databases—Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Scopus—both using a browser interface and through Harzing’s “Publish or Perish” software [23] for each species of the genus, using inverted commas for an exact match, e.g., “Xylosma benthamii”. Relevant articles were selected after removing search terms unrelated to the area of interest, such as reforestation or drought resistance. When abundant results were obtained, the search was refined with more specific terms, for example “Xylosma longifolia medicinal” or “Xylosma longifolia ethnopharmacology”. Duplicate articles were removed, and the remaining articles were reviewed with focus in ethnopharmacological uses, phytochemical composition, and biological activity. When possible, the latest articles—no older than 10 years—have been cited. Preprints were not included. Due to the scarcity of sources, gray documentation such as books and thesis dissertations were included when they provided information not available in other sources.

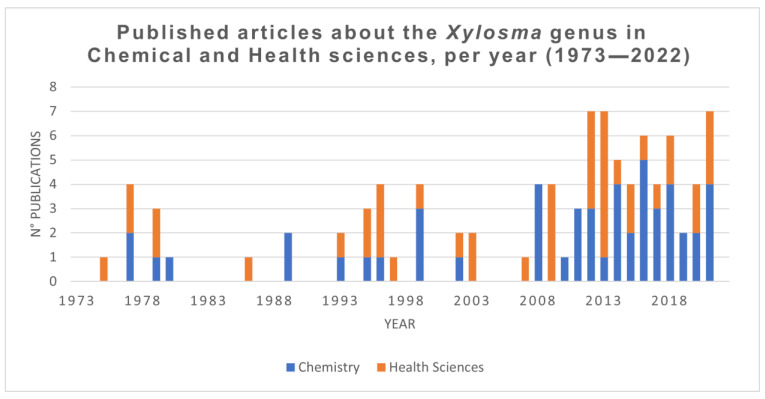

The research interest in Xylosma species in medical and health sciences has increased slowly during the last fifty years. Figure 3 shows the number of publications that include the word Xylosma in the document text in the fields mentioned. Even though the genus shows low research interest, a steady increase in appearances can be seen, with the last decade garnering much of the publication volume.

Figure 3.

Publications containing the word Xylosma since the year 1973 in Medical and Health sciences, and in Chemistry. Data source: [22].

Genus Xylosma shares several secondary metabolite compounds and structures with Flacourtia. Both were recently reassigned into the Salicaceae family from Flacourtiaceae. Indeed, they share genetical characters between them and with other genera from Salicaceae, such as Scolopia, Dovyalis, and Oncoba [24].

5. Ethnopharmacological and Ethnoveterinary Usage

Of the 100 species of the genus, few appear in the scientific literature, and even fewer are mentioned from an ethnopharmacological or ethnoveterinary perspective. Notwithstanding, Xylosma species are a part of the traditional Chinese medicinal system, with documented uses of X. congesta appearing as early as the XVI century CE [25].

Few of the Xylosma species are recognized as medicinal. Table 1 summarizes the species with reported medicinal use along with their stated ethnopharmacological uses, when available. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification by the World Health Organization (WHO) is used to classify the uses for each species [26]. Not all species are identified in the literature, with general mentions as “Xylosma sp.” in some cases.

Table 1.

Medicinal and veterinary use of Xylosma species, listed in alphabetical order.

| No. | Species | Region | Plant Organs Used | Use | Form of Usage |

ATC Category |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xylosma benthamii (Tul.) Triana and Planch. | Brazil | NS | Medicinal (not specified) |

NS | NS | [27] |

| 2 | Xylosma characantha Standl. | Nicaragua | Leaves | Placentary retention in cattle | Decoction | Vet. | [28] |

| 3 | Xylosma chlorantha Donn. Sm. | Costa Rica | Bark | Medicinal (not specified) |

NS | NS | [29] |

| 4 | Xylosma ciliatifolia (Clos) Eichler | Brazil | Root bark | Antibacterial | NS | V | [30] |

| 5 | Xylosma congesta (Lour.) Merr. | China Japan Korea |

Bark Leaves |

NS Anti-inflammatory Disease prevention in suckling piglets Birthing aid |

Bark ashes Poultice |

NS D G Vet. |

[31] [32] [33] [34] |

| 6 | Xylosma controversa Clos. | Guangxi, China | Roots Leaves |

NS | NS | NS | [35] |

| 7 | Xylosma flexuosa (Kunth) Hemsl. | Mexico | NS | Antipyretic Anti-tuberculosis |

NS | N R |

[36,37] |

| 8 | Xylosma horrida Rose. | Mexico Nicaragua Costa Rica |

Bark | Kidneys | Decoction | G | [38] |

| 9 | Xylosma intermedia (Seem.) Triana and Planch. | Bolivia | Bark | Toothache | NS | N | [39] |

| 10 | Xylosma longifolia Clos | India China |

Leaves Stem bark |

Antifungal Antispasmodic Antidiarrheic Anti-tuberculosis Muscle sprains Narcotic |

Paste Decoction Extract |

D A A R M N |

[40] [41] [42] [43] [44] |

| 11 | Xylosma panamensis (Turcz) | Panama Mexico |

Bark Leaves |

Cough Bronchitis |

Dried | R | [45] |

| 12 | Xylosma spiculifera (Tul.) Triana and Planch | Colombia, Venezuela | Leaves | Ulcers, Dermatitis | Decoction | D | [46] |

| 13 | Xylosma tessmanii Sleumer | Ecuador | Leaves | Medicinal (NS) | NS | NS | [47] |

| 14 | Xylosma sp. (not specified) | Panama | Stem Root |

Spider bites | Infusion | V | [48] |

| 15 | Xylosma sp. (not specified) | Perú | Bark | Bronchitis (with other plant species) | Decoction | R | [49] |

NS: Not specified. ATC categories are as follows. A: Alimentary tract and metabolism, B: Blood and blood forming organs, C: Cardiovascular system, D: Dermatological, G: Genito urinary system and sex hormones, H: Systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins, J: Anti-infective for systemic use, L: Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents, M: Musculo-skeletal system, N: nervous system, P: Antiparasitic products, insecticides, and repellents, R: Respiratory system, S: Sensory organs; V: Various [26]; STDs: Sexually transmitted diseases, Vet: veterinary.

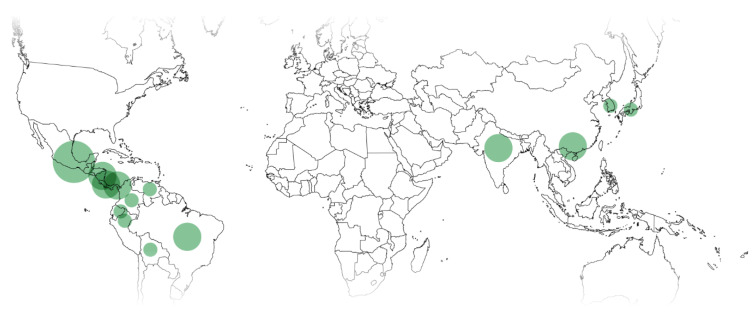

Most Xylosma species in use are from Central and South America (38% and 31%), followed by China (23%) and India (8%). This is roughly in accordance with the local abundance of species. There are no reports of ethnomedicinal uses of Xylosma in Oceania. Uses by country are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Ethnopharmacological and ethnoveterinary uses of Xylosma spp. Circle diameter proportional to use reports for the country.

According to the ATC classification, the most frequent uses of Xylosma spp. in ethnopharmacology are dermatological, nervous system, and respiratory system, with 17% of the uses each, alimentary tract and metabolism with 11%, and genitourinary system and sex hormones with 6%. Additionally, 11% of the uses are veterinary.

As to the morphological structures used, the most common are leaves and barks with 33% each, and both stems and roots with 11% each.

6. Biological Activity

Biological activity tests of Xylosma have been carried out mostly in vitro, with no reported in vivo research, with plant extracts, be they leaf, root, bark, or the whole plant. Different solvents and solvent mixtures have been used for the extracts, mainly methanol and ethanol.

In Vitro Activity

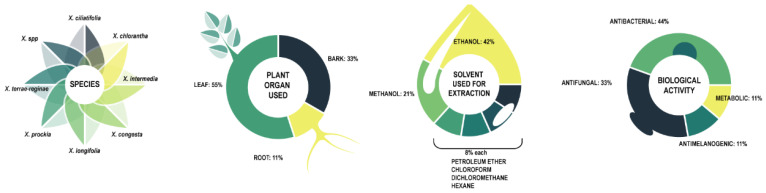

In vitro research on biological activity of Xylosma species centers around 7 identified species and one unspecified one. The research figures are summarized in Figure 5, and the research is detailed in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Summary of in vitro activity of Xylosma species.

Table 2.

In vitro activity of Xylosma extracts. Species are in alphabetical order.

| Species | Extract | Plant Organs Used | Biological Activity |

Biological Model |

Effect | Methodology | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X. ciliatifolia | Ethanol/Hexane partition | Root bark | Antibacterial |

S. aureus

S. epidermis S. typihimurium E. coli |

Effective against S. aureus S. epidermis MIC (µg/mL) 250, 500 |

Disk diffusion assay | [30] |

| X. clorantha | Ethanol | Leaves | Metabolic syndrome | HepG2 cells | LXR 2.14 ± 0.11: 100 µg/mL |

LXR transcriptional activity | [50] |

| X. congesta | Ethanol | Leaves | Anti-melanogenic | B16F10 cells | Melanin synthesis inhibition: up to 57.9% | α-MSH | [32] |

| X. intermedia | DCM/Ethanol | Bark | Antibacterial |

Bacillus cereus

S. aureus |

MIC (ppm) 156 512 |

Microbroth dilution | [51] |

| X. longifolia | Petroleum ether Chloroform Methanol |

Leaves, Stem bark | Antifungal |

Microsporum boullardii,

M. canis, M. gypseum Trichophyton ajelloi T. rubrum |

MIC (mg/mL) 0.141–9.0 |

Agar diffusion Micro wells diffusion |

[40] |

| X. prockia | Ethanol | Leaves | Antifungal | Cryptococcus spp. | MIC (ppm) 8–64 |

Antifungal microdilution susceptibility standard test | [52] |

| X. terrae reginae | Methanol | Root | Antibacterial Antifungal |

S. aureus

C. albicans |

MIC (mg/mL) 2.5 1.2 |

Dilution method | [53] |

| X. sp II | Methanol | Leaves | Antibacterial | Flavobacterium columnae | MIC 375 µg/mL |

Agar diffusion assay | [54] |

DCM: Dichloromethane; MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; α-MSH: melanocyte-stimulating hormone. LXR: LXRα Fold Activation.

In vitro biological activity tests devote the most attention to leaves (55%), with bark (33%) and root (11%) used to a lesser extent. Extraction solvents are ethanol (42%), methanol (21%), and to a lesser extent petroleum ether, chloroform, dichloromethane, and hexane, with 8% each. The solvent choices support the assumption that most active compounds are polar, and are thus extracted with polar solvents.

Testing centers on antibacterial (44%) and antifungal (44%) activity reflects the main ethnopharmacological use but appears to leave other traditional uses unexplored.

Cytotoxicity assays involving Xylosma extracts show no significant cytotoxicity for Xylosma prockia nor for Xylosma congesta leaf extracts [52,55]. Moderate cytotoxicity was reported for methanol Xylosma terrae reginae extracts [53]. 2,6-dimethoxybenzoquinone (33) isolated from Xylosma velutina is reported as cytotoxic [56].

Even though there is no in vivo research concerning Xylosma species in the literature, there are several patents that include Xylosma extracts for cosmetic, veterinary, and traditional medicinal uses, such as hangover cures [33].

7. Phytochemical Composition

Phytochemical studies allow for the identification, separation, and isolation of compounds of interest [57]. Based on phytochemical screenings and other results published in the literature, the most common metabolites are alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics, among which flavonoids and the distinctive, often glycosylated, dihydroxyphenyl alcohol derivatives (xylosmin, xylosmacin etc.) abound [58,59]. These are also abundant in Flacourtia (Salicaceae) spp extracts, and several flacourtins have been isolated [60], which have shown antimalarial [61] and antiviral [62] activity.

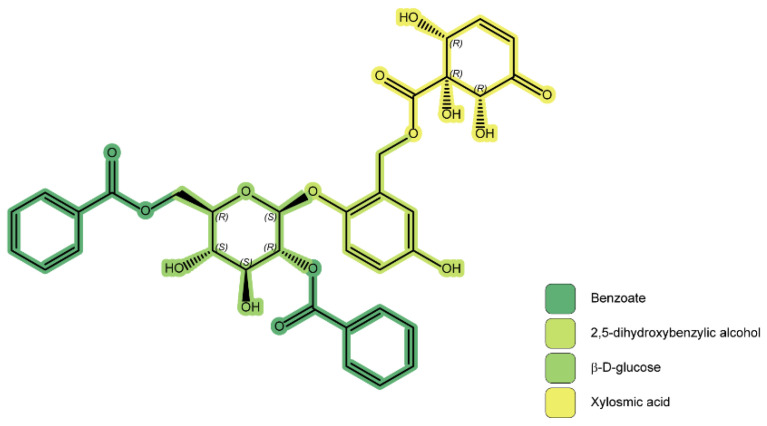

First isolated from the Central and South American Xylosma velutina (Tul.) Triana and Planch and considered an “iconic compound” of the genus [63], xylosmin (1) is composed of a glucose unit, two esterified benzoic acid units, a 2,5-dixydroxybenzilic alcohol, and a (1R,2R,6R)-1,2,6-trihydroxy-5-oxocyclohex-3-ene-1-carboxylic acid, often named “xylosmic acid”. Figure 6 shows the structure of 1, with the units highlighted in color.

Figure 6.

Xylosmin (1) structure. Moieties are highlighted as follows: xylosmic acid in yellow, benzoates in teal, d-β-glucose in light green, 2,5-dihydroxybenzylic alcohol in yellow-green.

After the isolation and identification of 1, several related compounds from Xylosma and Flacourtia genera, among others, have been isolated, some of which have been found to present antiplasmodial and antiviral activity [61,64]. Xylosmin also exhibits phosphodiesterase inhibitory activity [65] which could explain the use of a non-specified Xylosma sp. against spider bites [48].

Xylocosides are phenylpropanoid compounds and phenolic glycosides isolated from the Asian Xylosma controversa Clos [35]. Xylocoside G (11) shows neuroprotective effect against β-amyloid neurotoxicity [66].

Atraric acid or methyl 2,4-dihydroxy-3,6-dimethylbenzoate (16) was isolated from Xylosma velutina [67] and presents antifungal [40,68], anti-inflammatory [69], and antiandrogenic activity [70], which has led to the patenting of the acid and its alkylated derivatives in the treatment of prostate hyperplasia, carcinoma, and spinobulbar muscular atrophy [71].

Some compounds found in plants belonging to the Xylosma genus, classified according to their chemical structure, are listed in Table 3. Where applicable, the biological activity of the identified compound has been mentioned.

Table 3.

Compounds isolated/identified in Xylosma extracts and oils and their biological effect.

| No. | Compound | Identified/Isolated | Species | Collection Area | Plant Organ Used | Use | Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xylosmin | Y/Y |

X. velutina

X. flexuosa |

Colombia Guanacaste, Costa Rica |

Aerial parts | Antiviral Anti venom |

RNA polymerase inhibition PDE inhibition |

[72] [73] [62] [65] |

| 2 | 2′-benzoylpoliothrysoside | Y/Y | X. flexuosa | Guanacaste, Costa Rica | Aerial parts | [73] | ||

| 3 | Xylosmaloside | Y/Y | X. longifolia | North-east India | NS | Antioxidant | [42] | |

| 4 | Xylosmacin | Y/Y | X. velutina | NS | Stem bark | [67] | ||

|

5

6 7 8 9 10 |

Xylocosides A-F | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | [35] | ||

| 11 | Xylocoside G | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | Neuroprotective | [35] [66] |

|

| 12 | 3-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propane-1,2-diol | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | [35] | ||

| 13 | Salireposide | Y/Y | X. flexuosa | Guanacaste, Costa Rica | Aerial parts | [73] | ||

| 14 | 1-caffeoyl-β-d-glucose | Y/ | X. prockia | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Leaves | Antifungal | [52] | |

| 15 | 8-hydroxy-6-methoxy-3-pentylisocoumarin | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Cuc Phuong, Vietnam | Stem bark | Antituberculosis | MIC: 40.5 µg/mL | [41] |

| 16 | Atraric acid | Y/Y |

X. longifolia

X. velutina |

Manipur, India NS |

Leaves Bark |

Antifungal Antiproliferative |

[40] [70] |

|

| 17 | Catechin | Y/Y |

X. longifolia

X. controversa |

Manipur, India China |

Leaves | Antifungal PDE inhibitor |

[40] [65] |

|

| 18 | Genkwanin | Y/Y | X. velutina | Colombia | leaves, twigs and inflorescences | Immunomodulator | [72] [74] |

|

| 19 | Kaempferol | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Dehradun, India | Leaves | Antiproliferative | [75] [76] |

|

| 20 | Kaempferol-3-rhamnoside | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Dehradun, India | Leaves | Antioxidant | [75] | |

| 21 | Kaempferol-3-β-xylopyranoside-4′-α-rhamnoside | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Dehradun, India | Leaves | Antioxidant | [75] | |

| 22 | Quercetin | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Dehradun, India | Leaves | Antioxidant | [75] [77] |

|

| 23 | Quercetrin-3-rhamnoside | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Dehradun, India | Leaves | Antioxidant | [75] | |

| 23 | Rutin | Y/ | X. longifolia | Manipur, India | Leaves | Antifungal Antioxidant |

[40] | |

| 25 | Velutin | Y/Y | X. velutina | Colombia | Leaves, twigs and inflorescences | [72] | ||

| 26 | β-sitosterol | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Delhi, India | Leaves | Benign prostate hyperplasia symptom relief | [78] [79] |

|

| 27 | Lupeol | Y/Y | X.flexuosa | Guerrero, Mexico | Leaves | Anti-inflammatory | [80] [81] |

|

| 28 | Ugandensidial | Y/Y | X. ciliatifolia | Curitiba, Brazil | Root bark | Antibacterial S. aureus S. epidermis |

MIC 62.5µg/mL | [30] |

| 29 | Friedelin | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | Antioxidant Hepatoprotective |

[82] [83] |

|

| 30 | Velutinic acid | Y/Y | X. velutina | Colombia | leaves, twigs and inflorescences | [72] | ||

| 31 | n-hentriacontane | Y/Y | X. longifolia | Delhi, India | Leaves | [78] | ||

| 32 | Chaulmoogric acid | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | Antibacterial (leprosy) Neuroprotective |

[82] [84] [85] [86] |

|

| 33 | 2,6-dimethoxybenzoquinone | Y/Y | X. velutina | Colombia | Stem bark | Antibacterial Cytotoxic |

[67] | |

| 34 | (−) Syringaresinol | Y/Y | X. controversa | Guangxi, China | Stems | Bacteriostatic (H. pylori) | [82] [87] |

Y: Yes; NS: Not Specified; PDE: phosphodiesterase; MIC: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration.

Compounds have been isolated almost exclusively using chromatographic techniques, and have been identified through spectroscopical and spectrometric methods and by comparison with existing samples and published data [57].

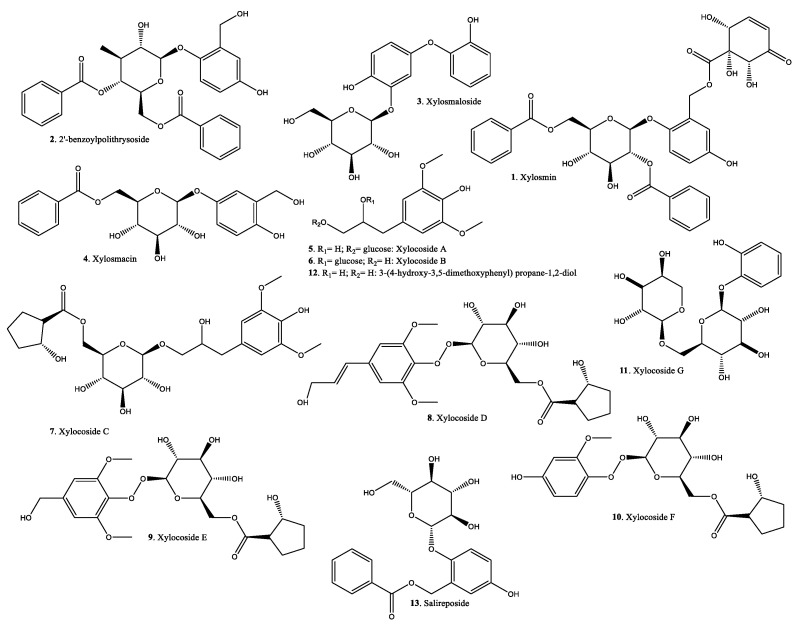

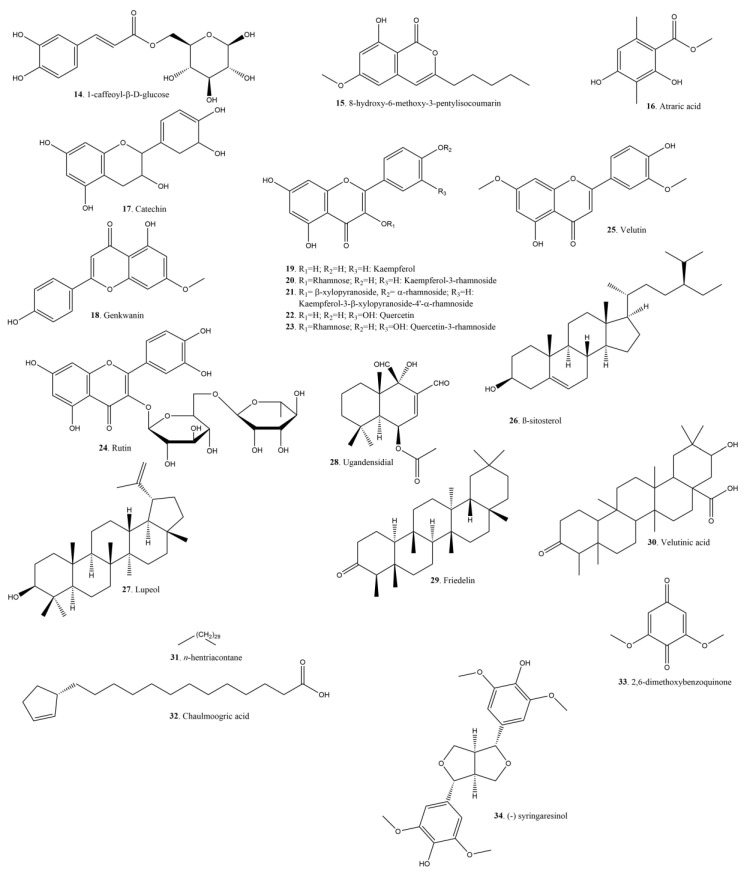

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the structure of some of the compounds identified in Xylosma spp. extracts. As expected in plant extracts, there is a variety of secondary metabolites in the form of terpenoids and flavonoids. There is a series of less usual phenolic compounds in the shape of dihydroxybenzyl alcohols and their glycosylated derivatives, esters, and ethers.

Figure 7.

Characteristic compounds identified in Xylosma extracts.

Figure 8.

Flavonoids, terpenoids, and other compounds identified in Xylosma extracts.

A strength of the genus is the potential for research it still holds: not many of its species have been systematically analyzed and interesting bioactivity can be found in previously unresearched species, as is the case with X. prockia [52]. A weakness is the conservation threat several of its species are under, particularly those from Oceania.

8. Conclusions

Species belonging to the Xylosma genus have several uses as food, medicine, wood, bird and pollinator attractors, etc. Among the medical uses, the ongoing research centers around the antibacterial, antifungal, anti-melanogenic, and antioxidant activity of Xylosma extracts, and other ethnopharmacological uses appear to have received less attention. This is seen as an opportunity for further study.

Several bioactive compounds have been isolated from Xylosma species, some of which have pharmacological potential, such as atraric acid, used in cancer treatments.

There are several species of the genus—more than 80%—that have not been systematically studied, especially in America. This presents a research opportunity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) for supporting this research and open access publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.R.-B. and R.D.-C.; investigation, R.D.-C.; resources, J.C.R.-B.; writing, R.D.-C.; review and editing, J.C.R.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hardy K. Paleomedicine and the Evolutionary Context of Medicinal Plant Use. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2021;31:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s43450-020-00107-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domínguez-Martín E.M., Tavares J., Ríjo P., Díaz-Lanza A.M. Zoopharmacology: A Way to Discover New Cancer Treatments. Biomolecules. 2020;10:817. doi: 10.3390/biom10060817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solecki R.S. Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq. Science. 1975;190:880–881. doi: 10.1126/science.190.4217.880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ur Rehman F., Kalsoom M., Adnan M., Fazeli-Nasab B., Naz N., Ilahi H., Ali M.F., Ilyas M.A., Yousaf G., Toor M.D., et al. Importance of Medicinal Plants in Human and Plant Pathology: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Biomed. Rese. 2021;8:1–11. doi: 10.18782/2394-3726.1110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrelli M. Medicinal Plants. Plants. 2021;10:1355. doi: 10.3390/plants10071355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamshidi-Kia F., Lorigooini Z., Amini-Khoei H. Medicinal Plants: Past History and Future Perspective. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2018;7:1–7. doi: 10.15171/jhp.2018.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katiyar C., Kanjilal S., Gupta A., Katiyar S. Drug Discovery from Plant Sources: An Integrated Approach. AYU Int. Q. J. Res. Ayurveda. 2012;33:10–19. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.100295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calixto J.B. The Role of Natural Products in Modern Drug Discovery. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2019;91:e20190105. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201920190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salicaceae Mirb.|Plants of the World Online|Kew Science. [(accessed on 25 January 2022)]. Available online: http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30002644-2.

- 10.Xylosma G. Forst.|Plants of the World Online|Kew Science. [(accessed on 25 January 2022)]. Available online: http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:332071-2.

- 11.WFO Xylosma G. Forst. [(accessed on 25 January 2022)]. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000041044;jsessionid=402EBB0471E61A8E4D367F550003835E.

- 12.The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Classification for the Orders and Families of Flowering Plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uphof J. The Dictionary of Economic Plants. Cramer; Lehre, Germany: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry S.S., Chapman J., Jones G., Jones J., Pass J., Roper C.F.E., Wilkes J. Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature: Comprehending, under One General Alphabetical Arrangement, All the Words and Substance of Every Kind of Dictionary Extant in the English Language: In Which the Improved Departments of the Mechanical Compiled, Digested, and Arranged, by John Wilkes, of Milland House…; Assisted by Eminent Scholars of the English, Scotch, and Irish, Universities. Champante and Whitrow; London, UK: 1810. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodson R.E., Schery R.W., Robyns A. Flora of Panama. Family 128. Flacourtiaceae. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1968;55:93. doi: 10.2307/2394875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vossler F.G. Flower Visits, Nesting and Nest Defence Behaviour of Stingless Bees (Apidae: Meliponini): Suitability of the Bee Species for Meliponiculture in the Argentinean Chaco Region. Apidologie. 2012;43:139–161. doi: 10.1007/s13592-011-0097-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García R., Pegüero B., Jiménez F., Veloz A., Clase T. Lista Roja de La Flora Vascular en República Dominicana. Ministerio de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (MESCyT); Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves R.D., Baker A.J.M., Jaffré T., Erskine P.D., Echevarria G., Ent A. A Global Database for Plants That Hyperaccumulate Metal and Metalloid Trace Elements. New Phytol. 2018;218:407–411. doi: 10.1111/nph.14907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seregin I.V., Kozhevnikova A.D. Physiological Role of Nickel and Its Toxic Effects on Higher Plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2006;53:257–277. doi: 10.1134/S1021443706020178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaney R.L., Angle J.S., Broadhurst C.L., Peters C.A., Tappero R.V., Sparks D.L. Improved Understanding of Hyperaccumulation Yields Commercial Phytoextraction and Phytomining Technologies. J. Environ. Qual. 2007;36:1429–1443. doi: 10.2134/jeq2006.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IUCN The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [(accessed on 1 February 2022)]. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/en.

- 22.Digital Science Dimensions [Software] [(accessed on 18 June 2021)]. Available online: https://app.dimensions.ai/analytics/publication/overview/timeline.

- 23.Harzing A.W. Publish or Perish. Tarma Software Research, Ltd.; Hertfordshire, UK: 2021. Version 8.2. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z.-S., Zeng Q.-Y., Liu Y.-J. Frequent Ploidy Changes in Salicaceae Indicates Widespread Sharing of the Salicoid Whole Genome Duplication by the Relatives of Populus L. and Salix L. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:535. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye H., Li C., Ye W., Zeng F., Liu F., Liu Y., Wang F., Ye Y., Fu L., Li J. Medicinal Angiosperms of Flacourtiaceae, Tamaricaceae, Passifloraceae, and Cucurbitaceae. In: Ye H., Li C., Ye W., Zeng F., editors. Common Chinese Materia Medica. Springer; Singapore: 2021. pp. 51–130. [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. [(accessed on 8 June 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification.

- 27.Van den Berg M.E., da Silva M.H.L., da Silva M.G. Plantas Aromáticas Da Amazônia; Proceedings of the 1er Simpósio do Trópico Úmido; 1986; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez-Flores O., Torréz-Centeno E., Valenzuela-Betanco R. Ph.D. Thesis. Universidad Católica Agropecuaria del Trópico Seco Pbro, Francisco Luis Espinoza Pineda; Estelí, Nicaragua: 2005. Plantas Utilizadas Para el Tratamiento de Enfermedades en los Animales Domésticos, Reserva Natural El Tisey, Estelí. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juep A. Master’s Thesis. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Educación y Enseñanza; Turrialba, Costa Rica: 2008. Rescate del Conocimiento Tradicional y Biológico Para el Manejo de Productos Forestales no Maderables en la Comunidad Indígena Jameykari, Costa Rica. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philippsen A.F., Miguel O.G., Miguel M.D., de Lima C.P., Kalegari M., Lordello A.L.L. Validation of the antibacterial activity of root bark of Xylosma ciliatifolia (Clos) Eichler (Flacourtiaceae/Salicaceae sensu lato) Rev. Cuba. Plantas Med. 2013;18:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shizhen L. Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume II: Waters, Fires, Soils, Metals, Jades, Stones, Minerals, Salts. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA, USA: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J.Y., Ahn E.-K., Ko H.-J., Cho Y.-R., Ko W.C., Jung Y.-H., Choi K.-M., Choi M.-R., Oh J.S. Anti-Melanogenic, Anti-Wrinkle, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Effects of Xylosma congesta Leaf Ethanol Extract. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2014;57:365–371. doi: 10.3839/jabc.2014.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yungui W. A Disease Control Method for Suckling Piglets. CN108235969A. Patent. 2018 July 3;

- 34.Duke J.A., Ayensu E.S. Medicinal Plants of China. Medicinal Plants of the World; Reference Publications; Algonac, MI, USA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Z.-R., Chai X.-Y., Bai C.-C., Ren H.-Y., Lu Y.-N., Shi H.-M., Tu P.-F. Xylocosides A-G, Phenolic Glucosides from the Stems of Xylosma controversum. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2008;91:1346–1354. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200890146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornejo-Báez A. Master’s Thesis. Universidad Veracruzana; Xalapa, Mexico: 2016. Evaluación de la actividad antibacteriana de los extractos y fracciones de Bidens pilosa L. y Xylosma flexuosum (H. B. & K.) Hemsl y estudio quimiométrico de la actividad antituberculosa de los perfiles cromatográficos de Bidens pilosa L. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grijalva Pineda A. In: Flora útil: Etnobotánica de Nicaragua. Ministerio del Ambiente y Recursos Naturales de Nicaragua, editor. MARENA; Managua, Gobierno de Nicaragua: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez-Torres F. Manual de Plantas Medicinales más Comunes del Occidente de Nicaragua. Universidad Autónoma de Nicaragua; León, Spain: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grandtner M.M. Elsevier’s Dictionary of Trees: With Names in Latin, English, French, Spanish and Other Languages. 1st ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: San Diego, CA, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devi W.R., Singh S.B., Singh C.B. Antioxidant and Anti-Dermatophytic Properties Leaf and Stem Bark of Xylosma longifolium Clos. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;13:155. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Truong B.N., Pham V.C., Mai H.D.T., Nguyen V.H., Nguyen M.C., Nguyen T.H., Zhang H., Fong H.H.S., Franzblau S.G., Soejarto D.D., et al. Chemical Constituents from Xylosma longifolia and Their Anti-Tubercular Activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2011;4:250–253. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2011.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swapana N., Noji M., Nishiuma R., Izumi M., Imagawa H., Kasai Y., Okamoto Y., Iseki K., Singh C.B., Asakawa Y., et al. A New Diphenyl Ether Glycoside from Xylosma longifolium Collected from North-East India. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017;12:1934578X1701200. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1701200832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salam S. Medicinal Plant Used for the Treatment of Muscular Sprain by the Tangkhul Tribe of Ukhrul District, Manipur, India. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2020;8:167–170. doi: 10.21474/IJAR01/12138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khare C.P. Indian Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated Dictionary. Springer Reference; Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joly L.G., Guerra S., Séptimo R., Solís P.N., Correa M., Gupta M., Levy S., Sandberg F. Ethnobotanical Inventory of Medicinal Plants Used by the Guaymi Indians in Western Panama. Part I. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1987;20:145–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(87)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García-Barriga H. Flora Medicinal de Colombia: Botánica Médica. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales; Bogotá, Colombia: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cerón C., Montalvo C. Reserva Biológica Limoncocha: Formaciones Vegetales, Diversidad y Etnobotánica. Cinchonia. 2000;1:20. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caballero-George C., Gupta M. A Quarter Century of Pharmacognostic Research on Panamanian Flora: A Review. Planta Med. 2011;77:1189–1202. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1271187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown M. Una paz Incierta: Comunidades Aguarunas Frente al Impacto de la Carretera Marginal. CAAAP; Magdalena, Perú: 1984. (Serie Antroplógica). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasquez Y. Biological and Chemical Investigation of Panamanian Plants for Potential Utility against Metabolic Syndrome. University of Mississippi; Oxford, MS, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Setzer M.C., Moriarity D.M., Lawton R.O., Setzer W.N., Gentry G.A., Haber W.A. Phytomedicinal Potential of Tropical Cloudforest Plants from Monteverde, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2003;51:647–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Folly M.L.C., Ferreira G.F., Salvador M.R., Sathler A.A., da Silva G.F., Santos J.C.B., dos Santos J.R.A., Nunes Neto W.R., Rodrigues J.F.S., Fernandes E.S., et al. Evaluation of In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Xylosma prockia (Turcz.) Turcz. (Salicaceae) Leaves Against Cryptococcus spp. Front. Microbiol. 2020;10:3114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mosaddik M.A., Banbury L., Forster P., Booth R., Markham J., Leach D., Waterman P.G. Screening of Some Australian Flacourtiaceae Species for in vitro Antioxidant, Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castro S.B.R., Leal C.A.G., Freire F.R., Carvalho D.A., Oliveira D.F., Figueiredo H.C.P. Antibacterial Activity of Plant Extracts from Brazil against Fish Pathogenic Bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2008;39:756–760. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822008000400030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuete V., Seo E.-J., Krusche B., Oswald M., Wiench B., Schröder S., Greten H.J., Lee I.-S., Efferth T. Cytotoxicity and Pharmacogenomics of Medicinal Plants from Traditional Korean Medicine. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:341724. doi: 10.1155/2013/341724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones E., Ekundayo O., Kingston D.G.I. Plant Anticancer Agents. XI. 2,6-Dimethoxybenzoquinone as a Cytotoxic Constituent of Tibouchina pulchra. J. Nat. Prod. 1981;44:493–494. doi: 10.1021/np50016a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altemimi A., Lakhssassi N., Baharlouei A., Watson D., Lightfoot D. Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts. Plants. 2017;6:42. doi: 10.3390/plants6040042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nassar M., Sáenz J.A., Galvez N. Phytochemical Screening of Costa Rican Plants: Alkaloid Analysis. V. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1980;28:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhattacharyya R., Boruah J., Medhi K., Borkataki S. Phytochemical Analysis of Leaves of Xylosma longifolia Clos.: A Plant of Ethnomedicinal Importance. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2020;11:2065–2074. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.11(5).2065-74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhaumik P.K., Guha K.P., Biswas G.K., Mukherjee B. (−)Flacourtin, a Phenolic Glucoside Ester from Flacourtia indica. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:3090–3091. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84606-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sashidhara K.V., Singh S.P., Singh S.V., Srivastava R.K., Srivastava K., Saxena J.K., Puri S.K. Isolation and Identification of β-Hematin Inhibitors from Flacourtia indica as Promising Antiplasmodial Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;60:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bourjot M., Leyssen P., Eydoux C., Guillemot J.-C., Canard B., Rasoanaivo P., Guéritte F., Litaudon M. Flacourtosides A–F, Phenolic Glycosides Isolated from Flacourtia ramontchi. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:752–758. doi: 10.1021/np300059n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prangé T., Lavaud C., Massiot G. A Reappraisal of the Structure of Xylosmin. Phytochem. Lett. 2021;41:123–124. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2020.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ghavre M., Froese J., Murphy B., Simionescu R., Hudlicky T. A Formal Approach to Xylosmin and Flacourtosides E and F: Chemoenzymatic Total Synthesis of the Hydroxylated Cyclohexenone Carboxylic Acid Moiety of Xylosmin. Org. Lett. 2017;19:1156–1159. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiao-Ping P. Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase Activity by Chemical Constituents of Xylosma controversum Clos and Scolopia Chinensis(Lour.) Clos. Chin. J. New Drugs. 2010;19:147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu Y., Zhou L., Sun M., Zhou T., Zhong K., Wang H., Liu Y., Liu X., Xiao R., Ge J., et al. Xylocoside G Reduces Amyloid-β Induced Neurotoxicity by Inhibiting NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway in Neuronal Cells. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:263–275. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-110779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cordell G.A., Chang P.T., Fong H.H.S., Farnsworth. Xylosmacin, a New Phenolic Glucoside Ester from Xylosma velutina (Flacourtiaceae) Lloydia-J. Nat. Prod. 1977;40:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X., Yu W., Lou H. Antifungal Constituents from the Chinese Moss Homalia trichomanoides. Chem. Biodivers. 2005;2:139–145. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mun S.-K., Kang K.-Y., Jang H.-Y., Hwang Y.-H., Hong S.-G., Kim S.-J., Cho H.-W., Chang D.-J., Hur J.-S., Yee S.-T. Atraric Acid Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Effect in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells and Mouse Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7070. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papaioannou M., Schleich S., Prade I., Degen S., Roell D., Schubert U., Tanner T., Claessens F., Matusch R., Baniahmad A. The Natural Compound Atraric Acid Is an Antagonist of the Human Androgen Receptor Inhibiting Cellular Invasiveness and Prostate Cancer Cell Growth. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:2210–2223. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoffmann H.-R., Matusch R., Baniahmad A. Isolation of Atraric Acid, Synthesis of Atraric Acid Derivatives, and Use of Atraric Acid and the Derivatives Thereof for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, Prostate Carcinoma and Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy. 8,481,519. U.S. Patent. 2013 July 9;

- 72.Chang P.T.O., Cordell G.A., Fong H.H.S., Farnsworth N.R. Velutinic Acid, a New Friedelane Derivative from Xylosma velutina (Flacourtiaceae) Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1443–1445. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)88804-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gibbons S., Gray A.I., Waterman P.G., Hockless D.C.R., Skelton B.W., White A.H. Benzoylated Derivatives of 2-β-Glucopyranosyloxy-2,5-Dihydroxybenzyl Alcohol from Xylosma flexuosum: Structure and Relative Configuration of Xylosmin. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:554–559. doi: 10.1021/np50118a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nasr-Bouzaiene N., Sassi A., Bedoui A., Krifa M., Chekir-Ghedira L., Ghedira K. Immunomodulatory and Cellular Antioxidant Activities of Pure Compounds from Teucrium ramosissimum Desf. Tumor Biol. 2016;37:7703–7712. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parveen M., Ghalib R.M. Flavonoids and Antimicrobial Activity of Leaves of Xylosma longifolium. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2012;57:989–991. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072012000100007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang Y., Chen A.Y., Li M., Chen C., Yao Q. Ginkgo biloba Extract Kaempferol Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J. Surg. Res. 2008;148:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu D., Hu M.-J., Wang Y.-Q., Cui Y.-L. Antioxidant Activities of Quercetin and Its Complexes for Medicinal Application. Molecules. 2019;24:1123. doi: 10.3390/molecules24061123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sultana S., Ali M., Jameel M. Aliphatic Constituents from the Leaves of Dillenia indica L., Halothamus bottae Jaub. and Xylosma longifolium Clos. Chem. Res. J. 2018;3:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilt T.J., Ishani A., MacDonald R., Stark G., Mulrow C.D., Lau J. Beta-Sitosterols for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1999;2011:CD001043. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Acton P., Ashton Q. Advances in Chlorophyll Research and Application. Scholarly Media LLC; Atlanta, GA, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu K., Zhang X., Xie L., Deng M., Chen H., Song J., Long J., Li X., Luo J. Lupeol and Its Derivatives as Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Efficacy. Pharmacol. Res. 2021;164:105373. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hong-Yan R., Ya-Nan L., Xing-Yun C., Peng-Fei T., Zheng-Ren X. Chemical Constituents from Xylosma controversum. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2007;16:218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sunil C., Duraipandiyan V., Ignacimuthu S., Al-Dhabi N.A. Antioxidant, Free Radical Scavenging and Liver Protective Effects of Friedelin Isolated from Azima tetracantha Lam. Leaves. Food Chem. 2013;139:860–865. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levy L. The Activity of Chaulmoogra Acids against Mycobacterium leprae. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1975;111:703–705. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.111.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cabot M.C., Goucher C.R. Chaulmoogric Acid: Assimilation into the Complex Lipids of Mycobacteria. Lipids. 1981;16:146–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02535690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cher C., Tremblay M.-H., Barber J.R., Chung Ng S., Zhang B. Identification of Chaulmoogric Acid as a Small Molecule Activator of Protein Phosphatase 5. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010;160:1450–1459. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miyazawa M., Utsunomiya H., Inada K., Yamada T., Okuno Y., Tanaka H., Tatematsu M. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori Motility by (+)-Syringaresinol from Unripe Japanese Apricot. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006;29:172–173. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]