ABSTRACT

A 10-year-old girl presented with left-eye esotropia and fixed mydriasis. Previously, she had been diagnosed with cerebellar ataxia and mild intellectual disability. Her parents were healthy. She was found to have partial aniridia of the pupillary sphincter bilaterally. A next-generation sequencing test for the inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate type 1 receptor (ITPR1) gene was performed, revealing a previously unreported homozygous variant of uncertain significance at c.7610. Computational (In Silico) predictive models predicted this variant to be disease causing. With the arrival of DNA sequencing, aniridia can be genetically classified. In this case report, we present a patient with phenotypic features of Gillespie’s syndrome with a homozygous variant in the ITPR1 gene that has not previously been reported.

KEYWORDS: Aniridia, Gillespie syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, ITPR1 gene

Introduction

Gillespie’s syndrome (OMIM 206700) is a rare disease characterised by bilateral iris hypoplasia, congenital hypotonia, cerebellar ataxia, and variable intellectual disability with damage to the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum.1 It was first described in 1965. Its prevalence is unknown, but there have been reports of 50 cases worldwide.2 It is an autosomal disease and can be dominant or recessively inherited by way of mutations in the inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate type 1 receptor (gene ITPR1) in chromosome 3p26.1. that codes one of the many inositol receptors in the cerebellar cells that make up part of the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1) and the calcium ATPase receptor.3,4 The most common ophthalmological symptoms include fixed and unresponsive to light dilated pupils.

Case report

A 10-year-old girl presented with left-eye esotropia and fixed mydriasis. Her previous clinical history included an adequate gestational weight, poor neonatal development due to hypotonia, as well as delayed speech and language with dysarthria and learning difficulties. At 5-years-old, she was diagnosed with cerebellar ataxia and mild intellectual disability. Previous ocular studies included an ultrasound showing bilateral optic nerve drusen and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that showed cerebellar vermis and hemisphere atrophy. Her family history was notable for consanguinity – her parents were third-degree relatives but were healthy.

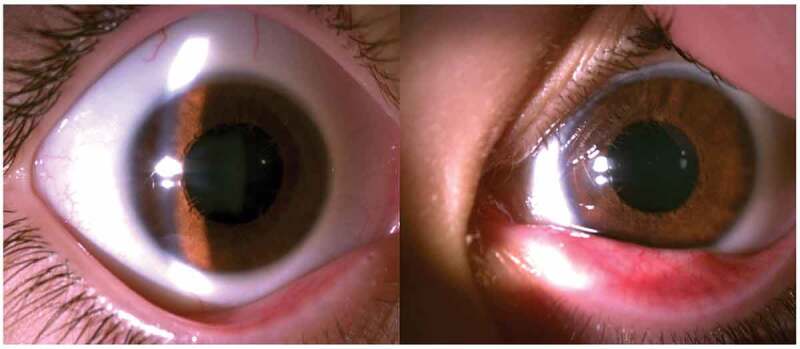

On physical examination, her visual acuity was 20/40 with a normal Ishihara test in both eyes. The left-eye esotropia was measured at +30 prism dioptres with normal ocular motility. Her pupils were fixed at 6 mm that did not change in the dark. On slit-lamp examination, there was a partial absence of the iris, with iris threads towards the anterior lens chamber (Figure 1). The optic discs were tilted, pink, and had small excavations without superficial drusen. Foveal hypoplasia was not present. Upon neurological examination, she had an ataxic gait, hyper-reflexia in all extremities, bilateral dysdiadochokinesia, and finger-nose dysmetria. There were no findings of facial dysmorphia.

Figure 1.

Partial aniridia can be observed in both eyes, with absence of the pupil margin and iris sphincter. In the left eye, iris threads can be observed in line with the anterior lens chamber.

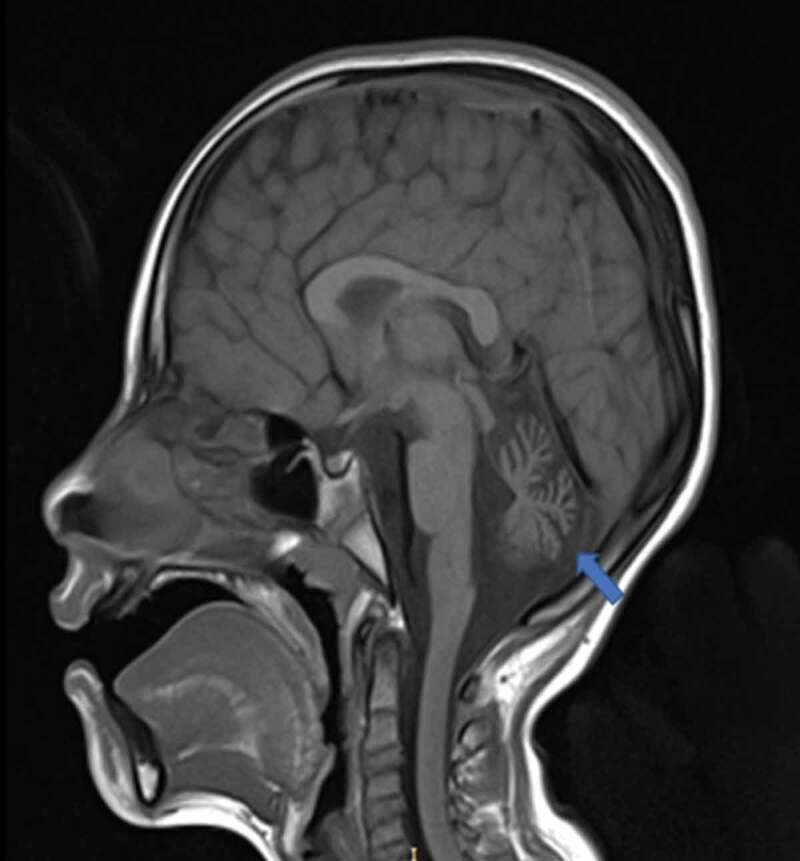

In collaboration with the genetic department, Gillespie’s syndrome was suspected and a next-generation gene-sequence test (NGS) was ordered for ITPR1 as well as a new brain MRI with contrast. The genetic results revealed a homozygous missense mutation c.7610 G > A (p.Arg2537Gln) in the ITPR1 gene. This variant had not been reported before in ClinVar or the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). According to the GnomAD database, its allelic frequency is less than 0.001. Analysing the results on PredictSNP, Polyphen 2 y Mutation Taster, the c.7610 G > A variant was classified as possible deleterious to an uncertain significance. Brain MRI revealed cerebellar atrophy (Figure 2). In the case of this reported patient, given her clinical features and history and having two of the same variants in the ITPR1 gene, it is highly suspicious that this is causative of her phenotype. Genetic testing of the parents was not possible to identify if she had received one variant from each of her parents.

Figure 2.

T1-weighted sagittal brain magnetic resonance imaging. The cerebellar vermis is atrophic (blue arrow). No other structural anomalies can be observed.

Discussion

A clinical diagnosis of Gillespie’s syndrome should be suspected in a patient with major clinical features including aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and developmental delay. Given the limited reports in the literature of this condition,5 this report of a Colombian patient with Gillespie syndrome further contributes to the understanding of the phenotype of this condition. Because of the limited cases and rarity of the condition, our case highlights that variants of uncertain significance may be identified through genetic testing of the ITPR1 gene. It is important to use clinical suspicion and assessment along with the genetic information in making a diagnosis as it will likely take time for enough data to accrue so that variants of uncertain significance are reclassified as pathogenic or conclusively disease causing.

In terms of other clinical signs associated with Gillespie’s syndrome, systemic signs have been reported including facial dysmorphism, pectoralis muscle agenesis, spinal fusion, kyphosis, and vesicoureteral reflux. Less commonly, reports have shown hypertelorism, ptosis, horizontal nystagmus, microdiscs, and foveal hypoplasia.6 There have also been previous reports of valvular stenosis with varying degrees of haemodynamic effects.7,8 Of note, these features were not present in our patient, and particularly, our patient's cardiovascular system was normal. Despite the NSG testing, diagnosis of Gillespie syndrome can be clinical upon diagnosis of cerebellar ataxia and partial aniridia. Other conditions to be considered include spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), which can also produce non- or slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia. Interestingly, there have been published reports identifying SCA type 29 associated with mis-sense variants in the ITPR1 gene that is associated with Gillespie’s syndrome. In contra-distinction to Gillespie’s syndrome, there are no ocular features in SCA type 29.9

In this case report, complementary gene studies were not performed for other aniridia-producing genes such as PAX6, FOXC1, and PITX2 because these mutations are not related to the observed phenotype. PAX6 mutations do not produce cerebellar hypoplasia but can present with pineal gland agenesis, olfactory bulb hypoplasia, fornix hypoplasia, and polymicrogyria.10

We report the first case of a novel ITPR1 homozygous genetic mutation in a Colombian patient who met the primary criteria for Gillespie’s syndrome. No testing was available for the parents, but they were evaluated and were healthy.

There remains uncertainty with respect to the chronic implications of this disease. It appears that the ataxia is non-progressive and the visual acuity remains resonable without deterioration, compared with PAX6 mutations that present with cataracts, limbal insufficiency, and varying degrees of progressive and severe glaucoma.11 It is believed that life expectancy and fertility in Gillespie’s syndrome patients is almost normal; however, there remains no definitive treatment for the disease or its clinical manifestations.12

We believe that an ophthalmological evaluation in patients with suspected genetic disorders is essential to detect ocular anomalies and to ensure a proper disease and severity classification.

Funding Statement

The authors reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors reveal they have no conflict of interests. This report was not financed by any organisation.

Patient consent and ethics statement

The patient’s parents consented to the publication of this case report.

References

- 1.Stendel C, Wagner M, Rudolph G, Klopstock T.. Gillespie’s syndrome with minor cerebellar involvement and no intellectual disability associated with a novel ITPR1 mutation: report of a case and literature review. Neuropediatrics. 2019;50(6):382–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Silva D, Williamson KA, Dayasiri KC, et al. Gillespie syndrome in a South Asian child: a case report with confirmation of a heterozygous mutation of the ITPR1 gene and review of the clinical and molecular features. BMC Pediatr. 2018; 18(1):308. Published September 24, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1286-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansari M, Rainger J, Hanson IM, et al. Genetic analysis of ‘PAX6-negative’ individuals with aniridia or Gillespie syndrome. PLoS One. 2016; 11(4):e0153757. Published April 28, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paganini L, Pesenti C, Milani D, et al. A novel splice site variant in ITPR1 gene underlying recessive Gillespie syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(6):1427–1431.doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ticho BH, Hilchie-Schmidt C, Egel RT, Traboulsi EI, Howarth RJ, Robinson D.. Ocular findings in Gillespie-like syndrome: association with a new PAX6 mutation. Ophthalmic Genet. 2006;27(4):145–149. doi: 10.1080/13816810600976897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho DR, Medeiros JEG, Ribeiro DSM, Martins BJAF, Sobreira NLM. Additional features of Gillespie syndrome in two Brazilian siblings with a novel ITPR1 homozygous pathogenic variant. Eur J Med Genet. 2018;61(3):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezende Filho FM, Pedroso JL, Freitas JL, Teixeira LF, Barsottini OGP. Aniridia as a clue for the diagnosis of Gillespie syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2020;78(6):383. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ando H, Hirose M, Mikoshiba K. Aberrant IP3 receptor activities revealed by comprehensive analysis of pathological mutations causing spinocerebellar ataxia 29. Proc National Acad Sci. 2018;115:12259–12264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811129115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zambonin JL, Bellomo A, Ben-Pazi H, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 29 due to mutations in ITPR1: a case series and review of this emerging congenital ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017; 12(1):121. Published June 28, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0672-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dentici ML, Barresi S, Nardella M, et al. Identification of novel and hotspot mutations in the channel domain of ITPR1 in two patients with Gillespie syndrome. Gene. 2017;628:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lima Cunha D, Arno G, Corton M, Moosajee M. The spectrum of PAX6 mutations and genotype-phenotype correlations in the eye. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(12):1050. Published December 17, 2019. doi: 10.3390/genes10121050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Defreyn A, Maugery J, Chabrier S, Coullet J. Syndrome de Gillespie: un cas rare d’aniridie congénitale [Gillespie syndrome: an uncommon presentation of congenital aniridia]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30(1):e1. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(07)89554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]