Abstract

Exercise rehabilitation has been proposed for the management of Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (NTOS). To date there have been no reviews of the literature regarding exercise rehabilitation for NTOS and their proposed clinical rationale. Understanding various exercise protocols and their clinical rationale may help guide rehabilitation clinicians in their exercise selection when managing NTOS. A scoping review was conducted on exercise rehabilitation for NTOS from inception to March 2021 in the PubMed database. Forty-seven articles consisting of literature reviews, non-randomized control trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case series, case studies and clinical commentaries met the inclusion criteria. This scoping review provides a broad overview of the most common exercise protocols that have been published and examines the purported clinical rationale utilized in the management of NTOS.

Keywords: exercise, neurogenic, rehabilitation, scoping review, thoracic outlet syndrome

Abstract

La rééducation par l’exercice a été proposée pour la prise en charge du syndrome neurologique du syndrome du défilé thoraco-brachial neurologique (SDTB). À ce jour, il n’y a eu aucune publication concernant la rééducation par l’exercice pour le SDTB et leur justification clinique proposée. Comprendre divers protocoles d’exercices et leur justification clinique peut aider à guider les cliniciens en réadaptation dans leur sélection d’exercices lors de la gestion du SDTB. Un examen de la portée a été effectué sur la rééducation par l’exercice pour le SDTB depuis sa création jusqu’en mars 2021 dans la base de données PubMed. Quarante-sept articles composés de revues littéraires, d’essais contrôlés non randomisés, d’études de cohorte prospectives et rétrospectives, de séries de cas, d’études de cas et de commentaires cliniques répondaient aux critères d’inclusion. Cet examen de la portée fournit un large aperçu des protocoles d’exercice les plus courants qui ont été publiés et examine la prétendue justification clinique utilisée dans la gestion du SDTB.

MOTS CLÉS: exercice, neurogène, rééducation, examen de la portée, syndrome du défilé thoracique

Introduction

The term Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) was first coined by Peet et al.1 in 1956 to describe a compromise of blood vessels or brachial plexus fibers at one or more sites between the base of the neck and axilla. TOS can further be clinically classified into vascular, arterial or neurogenic in nature.2,3 Neurogenic TOS (NTOS) is thought to be caused by compression of the brachial plexus at the interscalene triangle, the sub-coracoid space, or both, resulting in symptoms which may include pain in the neck and/or arm and paresthesia into the fingers.4 NTOS can be further classified as “true” or “disputed,” in which true NTOS presents with objective findings such as muscle wasting, motor weakness, sensory loss, electrophysiological changes, or radiological evidence of bony abnormalities attributable to the symptoms such as the presence of cervical ribs, whereas disputed NTOS lacks any objective findings.1–3 There has been much controversy in the field of musculoskeletal medicine surrounding disputed NTOS due to the lack of objective findings associated with the condition. Due to this controversy, some argue that this condition is over-diagnosed2, with an estimated reported incidence rate of two to three cases per 100,000 people per year4. Furthermore, there is a lack of consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria of NTOS among different expert groups, including the Society for Vascular Surgery and the Consortium for Research and Education on Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (CORE-TOS), adding onto the controversy of NTOS.5–6

The management of NTOS has typically focused on conservative approaches including exercise rehabilitation, manual therapy, hot/cold therapy, electrophysical modalities, and supportive devices such as strapping/taping as shown by a 2011 systematic review by Lo et al.7 Exercise therapy for NTOS has been hypothesized to decrease symptoms by increasing the thoracic outlet space through stretching and strengthening of certain muscles groups leading to increase joint space and decrease pressure on the brachial plexus.8 However, despite exercise rehabilitation being a cornerstone in the conservative management of NTOS, there are currently no reviews which aim to specifically describe the various types of exercise protocols that exists in the literature while examining their proposed theories and rationale.

Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to analyze the literature, from inception to March 2021, on rehabilitative exercises for true and disputed NTOS, to provide a broad and comprehensive overview of different exercise protocols that have been published and to provide an update to the literature from the systematic review by Lo et al.7 Our secondary aim was to review the clinical reasoning behind different exercise protocols which will help guide rehabilitation clinicians such as chiropractors and physiotherapists in their clinical decision-making and exercise prescription in the management of NTOS.

Methods

A scoping review of the literature was conducted using the framework of Levac et al.9 Our research question aimed to capture the breadth of literature regarding rehabilitative exercises for NTOS and their proposed clinical rationale from inception to March 2021. In order to gather a preliminary understanding of the literature, authors DL, RS, and KD briefly searched the literature and team meetings were held to refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria consisted of peer-reviewed English language primary and secondary articles which included narrative/literature reviews, systematic reviews, Cochrane reviews, randomized controlled and non-randomized controlled trials, retrospective and prospective cohort studies, case series, case reports, clinical commentaries, and consensus development statements. Case series, case reports and clinical commentaries were included as the aim of this scoping review was to capture the breadth of the existing literature on this topic and to examine the rationales that different authors have proposed in the literature. Articles that included a diagnosis of true or disputed NTOS and provided a description of rehabilitative exercises were included. Articles that included arterial or vascular TOS, post-operative rehabilitation, cadaveric or animal studies, or did not sufficiently describe the exercise intervention in detail (i.e., only reporting stretching but did not indicate the specific muscle or body region) were excluded.

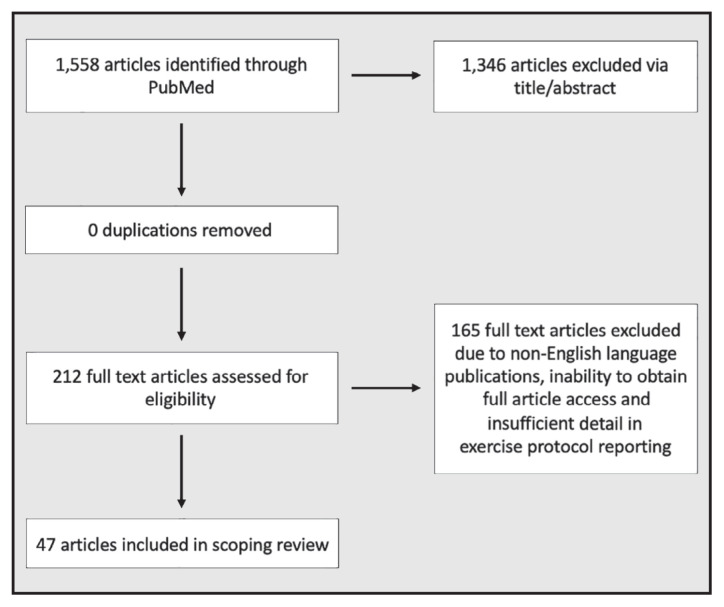

Team meetings were held with all authors and a health research librarian (KM) to refine the search strategy. The final search strategy (Appendix 1) was eventually formed by combining keywords related to exercise (concept A) and thoracic outlet syndrome (concept B) using both MeSH terms and title/abstract. The search strategy was inputted into the PubMed database on March 22, 2021 and yielded one thousand five hundred and fifty-eight articles. At the time, we believed that utilizing PubMed as our single search database was sufficient to address our research question due to our comprehensive search strategy and the fact that any additional articles included would not likely have changed the results of our findings. After screening for title and abstract, two hundred and twelve articles were eligible for individual article screening. Disagreements on inclusion based on title and abstract were resolved by discussion among the authors DL, RS, and KD. Two reviewers (DL and RS) then screened two hundred and twelve articles individually and any disagreements were settled by a third reviewer (KD). Articles were excluded due to a lack of sufficient detail in describing the exercise intervention, inability to obtain full access or due to articles not being published in English. An overview of our article screening process can be seen in Figure 1. Authors DL, RS and KD reviewed all forty-seven papers and extracted the information in Appendix 2. The extracted data included author and year of the publication, study design, types of treatments that were recommended along with exercise, description of the exercise protocol, and if appliable, the clinical rationale for the exercises chosen. The information in Appendix 2 was extracted by analyzing and combining the common themes of each exercise type and their rationale. Exercises were categorized by their purpose or intent in changing the biomechanics or properties of a particular tissue as described by the author. For example, studies that included stretching and strengthening exercises were included into Peet’s protocol8 as the intent and clinical rationale were similar among studies with slight variations in the protocols, whereas studies that looked specifically at exercises designed to address the physiological relationship between neural and non-neural tissue were categorized into neurodynamic exercises.14,20,46,53,32 Further detail can be seen in Appendix 2.

Appendix 1.

Search strategy keywords

| Concept A | Concept B |

|---|---|

| (thoracic outlet syndrome[Title/ Abstract]) OR (((“Thoracic Outlet Syndrome”[Mesh]) OR ((aperture syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR superior thoracic aperture syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR costoclavicular syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR cervical rib syndrome[MeSH] OR cervical rib syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR neurogenic syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR scalene syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR double crush syndrome[MeSH] OR double crush syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR crush syndromes[Title/Abstract] OR thoracic outlet syndromes[Title/Abstract] OR thoracic outlet neurovascular syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Superior Thoracic Aperture Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Costoclavicular Syndromes[Title/Abstract] OR Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Scalenus Anticus Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Thoracic Outlet Nerve Compression Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Venous Thoracic Outlet Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Arterial Thoracic Outlet Syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR Thoracic Outlet Neurologic Syndrome[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((thoracic outlet aperture syndrome[Title/Abstract] OR thoracic outlet aperture syndromes[Title/Abstract]))) |

(((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((( (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((physical therapists[MeSH]) OR (physical therapists[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical therapy modalities[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical therapy modalities[MeSH])) OR (physical therapist assistants[MeSH])) OR (physical therapist assistants[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical therapy specialty[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical therapy specialty[MeSH])) OR (rehab*[MeSH])) OR (rehab*[Title/Abstract])) OR (management[MeSH])) OR (management[Title/Abstract])) OR (stretch*[MeSH])) OR (stretch*[Title/Abstract])) OR (chiropract*[MeSH])) OR (chiropract*[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopath*[MeSH])) OR (osteopath*[Title/Abstract])) OR (postur*[MeSH])) OR (postur*[Title/Abstract])) OR (range of motion[MeSH])) OR (range of motion[Title/Abstract])) OR (physiatr*[MeSH])) OR (physiatr*[Title/Abstract])) OR (treatment[MeSH])) OR (treatment[Title/Abstract])) OR (exercise[MeSH])) OR (exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (compression/decompression[MeSH])) OR (compression/decompression[Title/Abstract])) OR (traction[MeSH])) OR (traction[Title/Abstract])) OR (rehabilitation[MeSH])) OR (rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (activities of daily living[MeSH])) OR (activities of daily living[Title/Abstract])) OR (exercise therapy[MeSH])) OR (exercise therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (motion therapy, continuous passive[MeSH])) OR (motion therapy, continuous passive[Title/Abstract])) OR (muscle stretching exercises[MeSH])) OR (muscle stretching exercises[Title/Abstract])) OR (plyometric exercise[MeSH])) OR (plyometric exercise[Title/Abstract])) OR (resistance training[MeSH])) OR (resistance training[Title/Abstract])) OR (neurological rehabilitation[MeSH])) OR (neurological rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (occupational therap*[MeSH])) OR (occupational therap*[Title/Abstract])) OR (recreation therapy[MeSH])) OR (recreation therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (myofunctional therapy[MeSH])) OR (myofunctional therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical therapy modalities [MeSH])) OR (physical therapy modalities [Title/Abstract])) OR (musculoskeletal manipulations[MeSH])) OR (musculoskeletal manipulations[Title/Abstract])) OR (hydrotherapy[MeSH])) OR (hydrotherapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (self-management[MeSH])) OR (self-management[Title/Abstract])) OR (self-care[MeSH])) OR (self-care[Title/Abstract])) OR (disease management[MeSH])) OR (disease management[Title/Abstract])) OR (pain management[MeSH])) OR (pain management[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative treatment[MeSH])) OR (conservative treatment[Title/Abstract])) OR (posture[MeSH])) OR (posture[Title/Abstract])) OR (postural balance[MeSH])) OR (postural balance[Title/Abstract])) OR (bed rest[MeSH])) OR (bed rest[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient positioning[MeSH])) OR (patient positioning[Title/Abstract])) OR (combined modality therapy[MeSH])) OR (combined modality therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (complementary therapies[MeSH])) OR (complementary therapies[Title/Abstract])) OR (manipulation, orthopedic[MeSH])) OR (manipulation, orthopedic[Title/Abstract]) OR ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((therapeutic[Title/Abstract]) OR (condition*[Title/Abstract])) OR (isometric[Title/Abstract])) OR (isotonic[Title/Abstract])) OR (isokinetic[Title/Abstract])) OR (plyometric[Title/Abstract])) OR (train*[Title/Abstract])) OR (warm up[Title/Abstract])) OR (warm-up[Title/Abstract])) OR (warming up[Title/Abstract])) OR (warming up[Title/Abstract])) OR (cool down[Title/Abstract])) OR (cool-down[Title/Abstract])) OR (cooling down[Title/Abstract])) OR (activit*[Title/Abstract])) OR (sport[Title/Abstract])) OR (pilate[Title/Abstract])) OR (yoga[Title/Abstract])) OR (yoga[Title/Abstract])) OR (pre-operative[Title/Abstract])) OR (post-operative[Title/Abstract])) OR (weight-lift*[Title/Abstract])) OR (weight lift*[Title/Abstract])) OR (program[Title/Abstract])) OR (weight bear*[Title/Abstract])) OR (weight-bear*[Title/Abstract])) OR (static[Title/Abstract])) OR (dynamic[Title/Abstract])) OR (ballistic[Title/Abstract])) OR (PNF[Title/Abstract])) OR (propriocep*[Title/Abstract])) ) OR (zone therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapies, zone[Title/Abstract])) OR (zone therapies[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapy, zone[Title/Abstract])) OR (massage therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (massage therapies[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapies, massage[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapy, massage[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative treatments[Title/Abstract])) OR (treatment, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (treatments, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative management[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative managements[Title/Abstract])) OR (management, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (managements, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative therapy[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative therapies[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapies, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (therapy, conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical medicine[Title/Abstract])) OR (physiatrics[Title/Abstract])) OR (physiatry[Title/Abstract])) OR (physical medicine and rehabilitation[Title/Abstract])) OR (medicine, physical[Title/Abstract])) OR (conservative[Title/Abstract])) OR (nonoperative[Title/Abstract])) OR (strength[Title/Abstract])) OR (resistance[Title/Abstract])) OR (aerobic[Title/Abstract])) OR (isometric[Title/Abstract])) OR (isotonic[Title/Abstract])) OR (athletic therap*[Title/Abstract])) OR (massage therap*[Title/Abstract])) OR (concentric[Title/Abstract])) OR (eccentric[Title/Abstract])) OR (anaerobic[Title/Abstract])) OR (circuit[Title/Abstract])) OR (high intensity[Title/Abstract])) OR (low intensity[Title/Abstract])) OR (physician, osteopathic[Title/Abstract])) OR (physicians, osteopathic[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopaths[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopathic physician[Title/Abstract])) OR (doctor of osteopathy[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopathy doctor[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopathy doctors[Title/Abstract])) OR (osteopath[Title/Abstract])) OR (joint range of motion[Title/Abstract])) OR (joint flexibility[Title/Abstract])) OR (flexibility, joint[Title/Abstract])) OR (range of motion[Title/Abstract])) OR (passive range of motion[Title/Abstract]) |

Figure 1.

Article flow through review process

Appendix 2.

Evidence summary table of author, year of publication, study design, treatment type, description of exercises and rationale.

| Author, year | Study design | Treatment (exercise alone or combined with other modalities) | Description of exercises (type, sets/reps, duration) | Rationale for exercise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abe et al. 1999 | Narrative review | Exercise followed by orthopaedic bracing | Serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and erector spinae muscle isometric strengthening. | Isometric shoulder girdle exercises in positions of relief. |

| Aktas et al. 2019 | Case report | Ultrasound-guided botulinum toxin injection to pectoralis minor | “Stretching exercises to the pectoral muscles were added to the rehabilitation program” | No rationale listed. |

| Aligne and Barral 1992 | Narrative review | Physical therapy utilizing mobilizations and exercise therapy | Isometric sternocleidomastoid, serratus anterior and superior trap exercises. Physical therapy sessions: 3x week for 1st month, twice weekly for the 2nd month, 6–8 sessions as needed in the future. | Enlarge the costoclavicular passage to decrease the constraints of the neurovascular elements. |

| Balderman et al. 2019 | Retrospective cohort study of prospectively collected data, 130 participants with nTOS undergoing physical therapy. | N/A | Scalene and pectoralis muscle stretching and relaxing exercises, with a focus on shoulder girdle and scapular mobility, mechanics, postural improvement, and diaphragmatic breathing, using caution with strengthening, weight training, and the use of resistance bands | No rationale listed. |

| Boezart et al. 2010 | Narrative review + case report | No treatment administered, just opinion | Nerve gliding exercises, 4–6 months of conservative therapy for specific neck and shoulder exercises. Strength training, weightlifting, and neck traction | Nerve gliding relieves tension on nerves of brachial plexus during arm and neck movements. 4–6 months of conservative therapy recommended by Kenny et al. 1993. |

| Brown 1983 | Narrative review | Physical therapy | Shoulder shrugs with 10lb weights in each hand. Bilateral arm abduction with pronated hands with weight in each hands. Wall push-ups | Restoration of normal postures. |

| Campbell 1996 | Case series | Case 1: exercises, posture repositioning strategies, ice and heat, discontinuing upper extremity exercise, soft tissue mobilizations, strengthening exercises. Case 2: Noritriptyline was prescribed and referral to occupational therapy |

Case 1: Cervical side bend stretches, and pelvic tilt exercises combined with deep breathing Prone middle and lower trapezius strengthening and latissimus strengthening of 5 repetitions each with 10s hold without weight. Told to increase repetitions to 10 after 3 days if tolerated without a return of symptoms. Progression involved a 1lb weight was added to this exercise and decreasing to 5 repetitions Case 2: physical therapy involved exercise program of middle trapezius, lower trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and rhomboid strengthening – 5 repetitions with 10 second hold. Told to increase this to 8 repetitions with 10 second holds within 7 days. Increased to a 2lb weight for 5 repetitions |

No rationale listed. |

| Christo & McGreevy 2011 | Narrative review | Behavioural/ergonomic modification, massage therapy. | Postural correction and shoulder girdle strengthening exercises, relaxation exercises, stretching, biofeedback exercises and nerve glides. | These interventions focus on decompressing the brachial plexus, restoring muscle balance in the neck, and providing neural mobility |

| Crawford 1980 | Narrative review | Postural education | Exercises designed to strengthen the muscles of the shoulder girdle are outlined and begun as follows: 10 times, twice a day Shoulder shrug + scapular retraction then protraction (2lbs each hand, progressing to 5–10lbs). Lateral raises with weights with 2lbs progressing to 5–10lbs. Standing leaning wall push-up. Lateral cervical flexion ROM isotonic contractions. Prone-lying chin tucks. Supine-lying pectoral stretch with towel between shoulder blades. |

No rationale listed. |

| Crosby et al. 2004 | Narrative review | Authors suggest pain control with medication, therapeutic modalities, injections, edema control with massage therapy, patient education on posture and ergonomics, and relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, mild aerobic exercise, contract-relax exercise, and hot showers/heat packs. | Tendon and nerve gliding exercises. Cervical spine ROM exercises, chin tucks – 5 sets 5 seconds. Shoulder ROM exercises, pendulum exercise with 1 lb weight to 1–2mins, shoulder shrugs with 1–3lbs. Relax shoulder girdle via upper trapezius, scalene and pectoralis stretching. Strengthening cervical extensors, scapular adductors. and shoulder retractors. |

Conservative treatment focuses on decreasing extrinsic pressure and reducing intrinsic irritation. By reducing inflammation in the thoracic outlet and shortening or lengthening the surrounding musculature for proper balance, pressure against the neurovascular bundle is decreased. Decreased intraneural pressure and minimize scarring (author noted not based on factual basis and on author preferences). |

| Dale and Lewis 1975 | Retrospective study | Exercise program followed by surgery if exercise not relieving. | 10 reps, two times per day. Shoulder shrugs with 2lb weights in each hand. Lateral raises starting at 90 degrees abduction to touching overhead with 2lbd weight in each hand. Pec stretch in corner of a wall. Neck lateral flexion B/L without shoulder shrugging. Prone thoracic spine extension with chin tucking, hold for three seconds then relax. Supine shoulder flexion above head with rolled up towel between shoulder blades. |

No rationale listed. |

| Dobrusin 1989 | Narrative review | Osteopathic treatment consisting of avoidance of aggravating factors, weight loss, manipulation, exercise, counselling, medication, trigger point therapy, physical therapy and surgery. | Peet protocol. 2lb per hand weighted shoulder shrugs and abduction manoeuvres. Prone thoracic and cervical spine extension exercises. Repetitions and weight increased as patient can tolerate |

Increasing strength and flexibility of shoulder and scapula elevators. Increase strength and flexibility of thoracic and cervical musculature. |

| Fitzgerald 2012 | Case report | Manual force to muscle, joint manipulation, home stretch, and home rehabilitation | Home stretch for pectoralis minor muscle – do not hyperabduct and trigger symptoms Home rehabilitation – stretching pectoralis minor and upper trapezius + strengthening serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi and rhomboid muscles | No rationale listed. |

| Hanif et al. 2007 | Quasi-experimental trial, 50 participants with nTOS | Prescribed tablet paracetamol & NSAIDs (e.g., Ibuprofen) for pain relief during the study. | Active strengthening exercises of paraspinal, scapular and trapezius muscles and stretching exercises of sternocleidomastoid, scalene anterior and pectoralis major muscles. 1x/day for 4 days per week, 6 consecutive months. |

No rationale listed. |

| Huang et al. 2004 | Narrative review | Modification of behaviors by avoiding provocative activities and arm positions, | Individually tailored physical therapy programs that strengthen the muscles of the pectoral girdle and help to restore normal posture. | Postural restoration. |

| Karas 1990 | Narrative review | No treatment administered, just opinion, and clinical experience | Trapezius, rhomboid, and levator scapulae muscles can be strengthened using elastic bands or free weights with arms elevated less than 90 degrees and with avoidance of bracing of scapulae. Some patients may start the exercise program with simple shoulder shrugs and progress to movements with increasing flexion in diagonal patterns. | Treatment of TOS should be guided by underlying pathogenesis and contributory factors. Cornerstone of conservative therapy is carefully regulated program of muscle strengthening and postural re-education exercises. |

| Smith 1979 | Single cohort trial + case study |

|

Shoulder girdle circumduction exercise + specific shoulder girdle and upper trunk exercises on a case-by-case basis. 1–3 weeks for maximum of 8–14 treatments. |

Exercises for specific shoulder girdle muscles and/or upper trunk are given only when there is evidence of musculoskeletal defect due to a postural fault, muscle weakness, or muscle tightness. Treatment objective is to:

|

| Kenny et al. 1993. | Prospective study | Physiotherapy | Graduates resisted shoulder elevation exercises for 3 weeks. Elevate shoulders and hold for a count of 5 then relax shoulders. Progress through 3 weeks increasing weight and reps every week. 15–20 repetitions, 5–6 times per day. | Decompress the brachial plexus with exercise. |

| Kuhn et al. 2015 | Narrative review | N/A | Physical therapy involves stretching, ROM exercises, and tendon and nerve gliding techniques. | No rationale listed. |

| Laulan J. 2016 | Narrative review | N/A | Initially, muscle relaxation and stretching exercises are performed to alleviate muscle tightening, followed by postural correction exercises for the cervical spine and shoulder girdle. In the last stage, an exercise program is used to strengthen the weak shoulder muscles. | The aim of rehabilitation is mainly to correct muscle imbalances in the cervicoscapular region. |

| Levine and Rigby 2018 | Narrative review | No treatment administered, just opinion |

|

Important to initially target scapular muscles to stabilize the shoulder. Strengthening the serratus anterior is important but horizontal adduction should be minimized to prevent further injury. Emphasis on proper scapular function during upper-body movements, breathing techniques, and head and pelvis alignment during various tasks. |

| Lindgren 1997 | Descriptive study | Exercise supervised by physiotherapists. | Shoulder girdle exercises consisted of movements where the patient brought the shoulders backward and up (left), flexed the upper thoracic spine, brought the shoulders forward and down (middle), and then straightened the back and brought the shoulders backward (right). These exercises were repeated 5 to 10 times. Chin tucks- The movement of the upper cervical spine can be effectively normalized by keeping the back and head firmly against a wall and then lowering the chin against the chest with the back of the head still touching the wall. The exercise can be made more effective by pressing the head down by hands. The exercise is repeated 5 to 10 times. Resisted scalene strengthening- Normal function of the first ribs and the upper aperture can be achieved by activation of the scalene muscles by the patient. The patient first activates the anterior scalene muscles by pressing the forehead against the palm, with the cervical spine being all the time in a neutral position (left). The middle scalene muscles are activated by pressing sidewards against the palm (middle), and the posterior scalene muscles by pressing the back of the head against the palm (right). The exercises are done five or six times for a duration of 5 seconds each and with about 15 seconds between the exercises. The exercises are done to both sides. Levator scapulae stretching- by grabbing a chair with the left hand and then bending the upper part of the body to the right. The head is then turned towards the ceiling. This position should be held for 5 to 10 seconds. The patient then relaxes and repeats the exercise five times. (B) An effective stretching exercise involving mainly the levator scapulae |

Shoulder exercises to restore full shoulder movement and provide more space for neurovascular components |

| Lindgren et al. 1995 | Case report | Physical therapy | Isometric scalene strengthening with force applied against hands. Hand placed at front, side and back of head and resists head movement. | Restore function of the upper thoracic aperture. Correct malfunctions of the first ribs. |

| Lindgren and Rytkonen 1997 | Controlled trial | Therapy administered in rehab ward | Shoulder exercises followed by cervical spine exercises for anterior, middle, and posterior scalenes, stretching of muscles of shoulder girdle, trapezius, levator scapulae, sternocleidomastoid, and small pectoral muscles. Further stretching administered as needed. Exercises advised to be done 4–6 times a day for 5–10 repetitions. Instructed to do for a year (3,6,12month follow-up) | Restore movement of whole shoulder girdle. Scalene exercises shown to correct malfunction of upper thoracic aperture. |

| Masocatto et al. 2019 | Narrative review | No treatment administered | Specific exercises aimed at strengthening and lengthening postural muscles of the back and shoulder. | Conservative management aims to alleviate neurovascular strain to reduce symptom severity and frequency through non-invasive means. Has shown to be effective in reducing pain. |

| McGough et al. 1979 | Narrative review | Physical therapy | Shoulder girdle strengthening and postural correction. Shoulder shrugs 5–10 times per day, 7–15 repetitions held for 3–4 seconds per repetition. Weight placed into plastic buckets and were lifted using shoulder girdle elevator muscles (plane of motion not indicated) 2–3 times per day | Basis of elevated and slightly abducted shoulder girdle decreases compressive forces on the neurovascular bundle |

| Nichols 2009 | Narrative review | Physical therapy | Gentle rehabilitation exercises. | No rationale listed. |

| Novak 2003 | Narrative review | Patient education on postural awareness and activity modification to minimize provocative positions. Physical modalities (heat, ultrasound, TENS). | Cervical retraction exercises, McKenzie method. Stretching pectoralis muscles. Strengthening/resistance exercises beginning gravity-assisted positions with an emphasis on motor re-education as to not over-recruit scapular elevators and to focus on lower scapular stabilizers. Diaphragmatic breathing. Aerobic conditioning program such as walking. |

Postural correction exercises to address elongated and weak lower scapular stabilizers and overuse of scapular elevators. Janda’s hypothesis of tight muscles; sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, upper trapezius, pectoral muscles, and weak muscles; deep neck flexors and lower scapular stabilizers. Treatment should be directed toward the restoration of normal muscle length and then toward increasing strength. The primary goal of therapy should be to correct postural abnormalities and muscle imbalance. |

| Novak et al. 1996 | Retrospective Study | Night splinting and exercises including ROM, stretching, strengthening and aerobic conditioning. | Upper trapezius, levator scapulae, scalene, and sternocleidomastoid stretching. Chin retraction. Strengthening middle/lower trapezius, serratus anterior, lower rhomboids. Diaphragmatic and lateral costal breathing. Progressive walking. |

Correcting poor posture to relieve pressure on neurovascular components and reversing obesity in patients. |

| Novak et al. 1995 | Retrospective study | Physical therapy including exercise program | Gradual stretching of trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, scalenes, suboccipitals and pectorals. Strengthening of middle and lower traps and serratus anterior. Diaphragmatic breathing and aerobic conditioning (walking). | Stretching and strengthening of shortened muscles. |

| Nichols and Seiger 2013 | Case report | Physical therapy consisting of exercises, manual therapy, and orthoses. | Shoulder and scapular resistance and stabilization training. Simulated boxing on the Nintendo Wii and shadow boxing. Exercise program consisting of: Cervical stabilization supine, shoulder banded ROM exercises in all planes, unilateral supermans, middle rows on yoga ball, body blade exercises, standing: arm by side, in front and behind held for 30 seconds B/L. Isometric contraction of levator scapulae, sternocleidomastoid and cervical extensor musculature. Wall push ups and arm bike: 5 minutes at 2.5 resistance level. | Stabilize sternoclavicular joints and improve upper extremity muscle performance. |

| Patetta et al. 2020 | Narrative review | No treatment, just opinion | Physical therapy focused on scalene stretching | No rationale listed |

| Pesser et al. 2021 | Prospective cohort study |

|

Posture evaluation and improvement, shoulder girdle therapy, scapular mobility therapy for 6–12 weeks (at least 1/week) physiotherapy and daily unsupervised training. | Treatment pathway based on North American SVS published in 2016. |

| Press and Young 1994 | Narrative Review | No treatment, just opinion | Physical therapy should address pectoral and scalene muscle stretching, scapular mobilization, and scapulothoracic mobility. Side-bending and cervical retraction exercises Thoracic extension and brachial plexus stretching Advancement to cervicothoracic stabilization exercises |

“opening up” the thoracic outlet by correcting abnormal structure and posture side-bending and cervical retraction exercises – can correct forward-head posture by stretching the soft tissues of the lateral cervical spine. |

| Richardson 1999 | Case series and review | Physiotherapy | Postural correction exercises. | Avoidance of swimming postures that contribute to TOS, increased thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis |

| Robey and Boyle 2009 | Case report | Shoulder strengthening and stretching + postural restoration institute (2 different treatments) | Intervention 1 - Shoulder strengthening and stretching: 2 times a day, 7 days a week: 3 times 30s of self stretching for bilateral neck, shoulder and chest muscles (scalenes, upper trapezius, pectoralis major muscles) + strengthening with tubing for the rotator cuff (internal + external rotators), deltoid, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, supraspinatus, biceps, and upper trapezius muscles for 3 by 15reps twice a day every day for 4 weeks. Intervention 2 – Postural Restoration Institute protocol. 1. 90/90 hip shift with hemibridge and balloon to activate hamstring, TA, internal and external intercostals, and abdominals) 2. sternal positional swiss ball release for 5 breaths done twice daily Intervention 3 – Postural Restoration Institute – seated resisted serratus punch with left hamstring muscles, standing resisted bilateral serratus press through, standing serratus squat, paraspinals release with left hamstrings, two-point stance on left and right sides, all 4 belly lift reach, long sitting press downs and latissimus dorsi hang with low trap activation. Done twice in one day. Done 5x each. |

Intervention 1 – improve posture via stretching and strengthening of shoulder girdle muscles. Intervention 2 – exercises beneficial for those with faulty posture, faulty respiration, and over-developed musculature. Exercises done to put pelvis in posterior tilt that causes ribs to depress → discourages paraspinal and neck muscles from firing. Goal is to reduce overactivation of paraspinal muscles and encourage rib depression and abdominal muscles to work in a shortened position. |

| Sadat et al. 2008. | Narrative review | Physical therapy (moist heat and massage) and exercise program | Pectoral stretching, levator scapulae strengthening and postural correction exercises. | Increase space between first rib and clavicle. Improve posture and muscular stability. |

| Sanders and Annest 2017 | Narrative review | No treatment, just opinion | Pectoral minor stretching – 3 times a day for 15–20 seconds, rest for the same length of time and do 3 times at each session. | No rationale listed. |

| Sheon et al. 1997 | Commentary | No treatment administered (just opinion stated) | Exercises to strengthen shoulder elevator and neck-extensor muscles. | No rationale listed. |

| Strukel et al. 1978 | Case series | Case 1: wrist curl + stretching exercise + oral steroids → after 1 year revisited and did rehabilitation of the shoulder Case 2: strengthening exercises Case 3: rehabilitation program Case 4: rehabilitation program |

Special exercises to strengthen the upper, mid, and lower trapezius, along with serratus anterior and erector spinae muscles, coupled with attention to correcting the drooping shoulder Case 1: strengthening suspensory musculature of the shoulder Case 2: strengthening program of the shoulder suspensory muscles Case 3: rehabilitation program (no specifics) + discouraged from neck strengthening exercises Case 4: rehabilitation program (no specifics) |

Based off of Britt’s recommendations (Britt LP 1967) and that this protocol ‘has brought good results in our patients’ Case 1: see reference 26 of this paper Case 2: no rationale Case 3: no rationale Case 4: no rationale |

| Sucher 1990 | Narrative review | Analgesic or anti-inflammatory medication. Muscle relaxants. Heat, ultrasound, electrical muscle stimulation. Osteopathic manipulative myofascial release to restricted or contracted muscles. Postural awareness and correction. |

Vigorous progressive stretching 5–10 times per day, holding for 10–30 seconds. Stretching of anterior/middle scalene, pectorals | Re-energizing of tissues and reprogramming of central engram for the particular muscle length. |

| Sucher and Heath. 1993. | Narrative review | Osteopathic treatment including myofascial release | Strengthening of parascapular muscles. High repetition, light weight exercises with bands. | Decrease shortening of muscles and prevent recurrence of trigger points causing pain in patient |

| Thevenon et al. 2020 | Retrospective single-centered hospital based study of 63 patients for 3 weeks (15 sessions, 3–5 times a week) | A daily physiotherapy session, a pool exercise session, and an occupational therapy session and optional psychological support. passive mobilization of the cervical spine and the scapula, and relaxation of the neck and shoulder muscles via massage, stretching, and hold-relax exercises | Diaphragmatic breathing. Strength training focusing on shoulder girdle elevators consisting of supine-lying shoulder elevation, single-arm scapular protraction, and isometric contractions of neck extensors. Pectoral stretching |

No rationale listed. |

| Vanti et al. 2007 | Literature review of 8 open non-controlled studies, 1 retrospective non-controlled study, and 1 prospective clinical trial ranging from 8 to 119 participants. | Studies had a combination of patient education, manual therapy including joint mobilizations, soft tissue and massage treatment, heat, ultrasound, adhesive bandages, and/or strapping device. | Peet’s exercises (strengthening posterior spine muscles, isometric exercises for serratus anterior and pectoralis minor, exercises aimed at targeting muscles that depress the first rib) at home, daily with weights up to 1kg each hand. Graduated resisted shoulder elevation for count of 5 (weights ranged from 0–5lbs) for 3 weeks, 5 times daily. Britt’s method; shoulder girdle exercises involving strapping device to elevate shoulders. Graduated stretching program for shoulder girdle elevators, chin retraction exercises, strengthening lower scapular stabilizers, and aerobic conditioning program. Exercises targeting anterior, middle and posterior scalenes, strengthening of shoulder girdle elevators and small pectoral muscles, scapular stabilizers for 5–10 times a day. Shoulder resisted adduction and extension, cervical isometric and stabilization. |

Restore muscle balance; strengthening muscles that open the thoracic outlet by raising the shoulder girdle (e.g – trapezius, sternocleidomastoid), stretching muscles that close the thoracic outlet (e.g. – lower trapezius, scalene muscles). Postural correction. |

| Walsh. 1994. | Narrative review | Home exercise program. Conditioning and strengthening of muscles necessary to maintain postural correction. |

Peet protocol for exercises. Scalene stretching, cervical protraction and retraction, diaphragmatic breathing, pec stretching, shoulder circle exercises. | Improve the flexibility of the entire thoracic outlet area. |

| Watson et al. 2010 | Narrative review | Authors recommend ‘axillary sling’ or taping to create scapular elevation and upward rotation during exercises if exercises are too provocative in symptoms. | Scapular control phase: upward rotation shrug in 20–30 degrees of abduction in standing, progressing functional movement patterns (abduction in external rotation) and breaking isolated movements down if necessary. 20 reps 3x/day in which patient can maintain control. Progressed starting with 0.5kg in hand increased until 2kg to 20 repetitions. Load phase: resisted upper trapezius (upward rotation shrugs), external rotation (usually side-lying), posterior deltoid (extension standing), subscapularis (supine internal rotation) and anterior deltoid (supine flexion), Prone horizontal extension drills are also very good drills for developing posterior deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor. Resisted exercises: once per day 2kg for women, 3kg for men, endurance repetition range. Hypertrophy phase: >3kg, 6–8 repetitions, 4 sets, once per day. |

Exercises are focused on addressing “drooping shoulder” (shoulder girdle depression) as it leads to altered scapular kinematics and possible traction stress on the neurovascular bundle of the thoracic outlet. The rehabilitative approach is to elevate the shoulder girdle to “decompress” the thoracic outlet and restore scapular control. Focus on establishing normal scapular muscle recruitment and control in resting position. Once this is achieved then the program is progressed to maintaining scapula control while both motion and load are applied. The programme begins in lower ranges of abduction and is gradually progressed further up into abduction and flexion range until muscles are being re-trained in functional movement patterns at higher ranges of elevation. Emphasis is on facilitating and encouraging sufficient firing in any muscles that may be weak, inhibited or slow to switch on in the normal movement strategies. |

| Wehbe and Schlegel. 2004. | Narrative review | Nerve gliding exercises | Diagrams of upper and lower plexus nerve gliding, median nerve at elbow and wrist nerve gliding, ulnar nerve at elbow, dorsal wrist and plantar wrist and radial nerve at spiral groove, elbow and wrist nerve gliding. | Nerve gliding to help accommodate joint motion to prevent injury. |

N/A = not applicable; lb = pound; ROM = range of motion; B/L = bilaterally; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; kg = kilogram; TENS = transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; SVS = Society for Vascular Surgery; TA = transverse abdominus

Results

A total of forty-seven articles from 1975 to 2021 met our inclusion criteria and were extracted into Appendix 2. Of the forty-seven articles, twenty-six were narrative and literature reviews, five were retrospective studies, three were prospective studies, three were non-randomized control trials, three were case series, five were case studies, and two were clinical commentaries.8,10–57 The results of our findings are presented in the following order: exercise alone versus exercise with other treatment modalities, clinical rationale of exercise protocols, and a description of the exercise protocols themselves.

Exercise alone versus exercise with other treatment modalities

A total of twenty-one articles included exercise in addition to other treatment options such as analgesic or anti-inflammatory medications, botox injections, hot/ cold therapy, electrophysical modalities such as TENS and ultrasound, manual therapy (joint mobilizations, manipulation, massage and other soft tissue therapy techniques), orthoses, night splinting, and patient education regarding ergonomics and postural awareness.8,11,13–14,16–17,19–22,24–25,29–31,36,49–50,52,55–56 One quasi-experimental trial looked at combining paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medication with exercise14, one retrospective study looked at the effects of exercise and manual therapy with optional psychological support19, and another retrospective study looked at a combination of a night splint with exercise.26 One case report looked at combining manual therapy with exercise.36 Two retrospective studies12,26, one prospective cohort study28, two case reports34,37, and one case series35 looked at the effects of exercise alone on NTOS symptoms.

Clinical rationale of exercise protocols

Thirty-three articles purported the following clinical rationale: i) postural correction, ii) “decompression” of the thoracic outlet by strengthening the muscles responsible for shoulder girdle elevation, iii) establishing normal scapular control, iv) facilitation of weak or inhibited muscles, v) decreasing pressure on the neurovascular bundle by lengthening the surrounding musculature to restore proper muscular balance, vi) decreasing intraneural pressure, vii) “re-energizing” tissues and “reprograming” the central engram to normalize muscle length, viii) enlarging the costoclavicular passage by improving muscular flexibility and joint stability, ix) restoring normal joint motion, and x) decreasing the shortening of muscles to prevent recurrence of trigger points.8,11,13,15–17,20–22,24–39,40–41,43–47,49,51,53 A detailed outline of each article and the author’s rationale for their exercise selection can be seen in Appendix 2.

Exercise protocols

Peet’s protocol

Peet was the first to design an exercise protocol for managing NTOS in 1956 and his protocol has been used and modified by several others.57 The protocol by Peet included strengthening of the levator scapulae muscle, stretching of the pectoralis minor and postural correction exercises.8 A literature review by Vanti et al.8 reviewed several articles that presented modifications of Peet’s protocol, including exercises aimed at depressing the first rib and strengthening of the posterior spinal muscles, and isometric exercises for the serratus anterior and pectoralis minor. The exercise protocols varied in their dosages, with one study recommending that the protocol to be done daily with weights up to 1kg in each hand while another study recommended the exercises be done with 0–5lbs for three weeks, five times daily, and a different study recommended daily home exercises be done two to three times per week.8

The clinical rationale behind Peet’s protocol is to restore muscle balance and achieve postural correction by strengthening muscles that open the thoracic outlet by raising the shoulder girdle (e.g., trapezius, sternocleidomastoid) and stretching muscles that close the thoracic outlet (e.g., lower trapezius, scalene muscles).8 However, as Vanti et al.8 noted in their review, there was no agreement between authors on which muscles needed strengthening and which muscles needed stretching, with some authors arguing for strengthening muscles responsible for shoulder elevation whereas others argued for stretching muscles of shoulder elevation.

Britt’s method

Britt’s method involves a similar rationale to Peet’s with the addition of shoulder girdle exercises involving a strapping device to elevate the shoulders.8 Britt’s method also includes cervical retraction exercises, a graded stretching program for shoulder girdle elevators, resisted shoulder adduction and extension exercises, and strengthening of the lower scapular stabilizers, shoulder girdle elevators, and small pectoral muscles.8 It was recommended that exercises be done five to ten times a day in addition to an aerobic conditioning program.8

Addressing scapular kinematics

In a narrative review by Watson et al.11, the authors recommended exercises to address the “dropping shoulder” (shoulder girdle depression) that can sometimes be seen in NTOS, as this can lead to altered scapular kinematics and traction stress on the neurovascular bundle of the thoracic outlet. This rehabilitative approach was designed to elevate the shoulder girdle in order to “decompress” the thoracic outlet and restore scapular control.11 The first stage focused on establishing normal scapular muscle recruitment and control in the resting position.11 Once this had been achieved, then the program progressed to adding movement and load while maintaining scapular control.11 The exercise program begins with lower ranges of shoulder abduction and gradually progresses to larger ranges of shoulder abduction and flexion with the goal of re-training the muscles in more functional movement patterns.11 The authors noted that there should be an emphasis on facilitating and encouraging sufficient firing in any muscles that may be weak, inhibited, or slow to switch on in their normal movement strategies.11 However, the authors noted themselves that this was based on their own clinical opinion and that scientific data was lacking to support their views.11

Nerve gliding exercises

Crosby et al.14 highlighted the use of tendon and nerve gliding exercises in combination with cervical spine range of motion exercises, shoulder pendulum exercises, stretching of the upper trapezius, scalene group and pectorals, and strengthening of the cervical extensors, scapular adductors and shoulder retractors. The authors proposed that these exercises would help to decrease intraneural pressure, minimize scarring, decrease extrinsic pressure and reduce intrinsic irritation of the surrounding neurovascular structures.14 However, the authors noted that this was based on clinical opinion and not on any scientific evidence.14 Christo and McGreevy20 also proposed nerve gliding exercises with the aim of providing neural mobility in combination with postural correction exercises, shoulder girdle strengthening, relaxation via biofeedback and stretching exercises to help with decompression of the brachial plexus and restoration of muscle balance in the neck. Boezart et al. 46 recommended four to six months of conservative therapy with specific neck and shoulder exercises including strength training, neck traction, and nerve gliding exercises which aimed to relieve neural tension on the brachial plexus during arm and neck movements. Press and Young53 described physical therapy for NTOS with the goal of “opening up” the thoracic outlet by correcting abnormal posture with side-bending and cervical traction exercises, advancing to cervicothoracic stabilization exercises and brachial plexus stretching. Lastly, Wehbe and Schlegal32 provided a clinical commentary on upper and lower plexus nerve gliding, median nerve gliding at the elbow and wrist, ulnar nerve gliding at the elbow and wrist, and radial nerve gliding at the humeral spiral groove, elbow and wrist. The authors emphasize the importance of slacking one end of the nerve while pulling on the opposite end to avoid tensioning the nerve on both ends and so that “gliding” could ensure.32

Restoration of breathing mechanics

Several articles recommended an aerobic conditioning program such as walking or diaphragmatic breathing exercises in combination with stretching and strengthening exercises.12,16,19,24,26–27,55 Robey and Boyle41 described a protocol from the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI), where the aim was to restore over-developed faulty respiratory muscles by positioning the pelvis into posterior tilt while encouraging rib depression during breathing exercises to help discourage over-involvement of the paraspinal and neck musculature. Specific exercises and progressions can be seen in Appendix 2

Exercise dosage

Exercise dosage such as frequency, sets and repetitions varied considerably across studies with no agreed upon dosage. For example, Peet’s protocol was recommended fives times daily for three weeks, while Britt’s method was recommended five to ten times per day.8 The scapular focused protocol proposed by Watson et al.11 recommended twenty repetitions three times per day for the initial scapular control phase, then once per day with resistance during the loading phase and then four sets of six to eight repetitions once per day for the final hypertrophy phase. A quasi-experimental trial by Hanif et al.14 consisted of strengthening exercises that were prescribed to patients once per day, four times per week for six months, while Crawford et al.18 recommended strengthening exercises of ten repetitions twice per day and Sucher et al.21 recommended stretching five to ten times per day, holding each stretch for ten to thirty seconds. Whereas a case report by Robey and Boyle41 prescribed three sets of thirty-secondlong stretching exercises twice per day for seven days a week and three sets of fifteen repetitions twice per day, daily for four weeks. A non-randomized controlled trial by Lindgren et a.l37 administered NTOS exercises to be done four to six times a day for five to ten repetitions and instructed the patients to continue the exercises for one year. Sanders and Annest48 recommended pectoral minor stretching to be done three times per day for three sets of fifteen to twenty second holds. A prospective cohort study by Pesser et al.51 prescribed scapular mobility exercises for six to twelve weeks at least once per week during in-person physiotherapy sessions and daily at-home exercises.

Discussion

In reviewing the literature on exercise rehabilitation for the treatment of NTOS, there were several concerns that are important for clinicians to consider – namely the different clinical rationales that were proposed and the variation in exercise dosage. The clinical rationale proposed by most authors involved postural “correction” and “decompression” of the thoracic outlet via restoring proper muscular balance.8,11,13,15–17,20–22,24–39,40–41,43–47,49,51,53 However, there appeared to be inconsistencies and at times even contradictions in the clinical reasoning between authors. This was evident from the literature review by Vanti et al.8, in which there was no agreement on which muscles needed strengthening and which muscles needed stretching, where some argued for strengthening muscles responsible for shoulder elevation whereas others argued for stretching muscles of shoulder elevation. This begs the question as to whether specific muscle stretching and strengthening protocols play an important role in the management of NTOS or if exercise in general is a sufficient modality for this condition.

Another concern was the scapular focused program aimed at restoring normal scapular control, proposed by Watson et al. 11 To date, there have been no clinical trials examining scapular focused exercises on NTOS compared to other forms of exercise, and it is not known if changing scapular kinematics leads to a change in NTOS symptoms. The authors noted themselves that a scapular focused exercise protocol was based on their own clinical opinion and not on any scientific data.11 It should also be noted that the literature regarding scapular assessment for dyskinesia in relation to shoulder pain has shown poor interrater reliability and low methodological quality.60–62 Additionally, several studies have also shown that scapular focused exercises for shoulder pain did not alter scapular kinematics, despite patients demonstrating an improvement in shoulder pain.63–64 This information calls into question the utility of scapular focused exercises and their ability to alter scapular kinematics in the management of NTOS.

In regard to exercise dosage, there was considerable inconsistency across studies, as is commonly seen in the exercise rehabilitation literature for musculoskeletal pain.58 However, clinicians can use the variability of the different exercise dosages from this review as a guide to incorporate shared decision making to fit the individual needs and goals of the patient.59

Lastly, a majority of articles included in the scoping review advocated for postural correction exercises in the management of NTOS. However, the studies included in the scoping review did not measure or evaluate whether or not postural changes actually occurred despite prescribing exercises with the intent of changing posture. Therefore, changes in pain and function may have been independent from any postural changes.8,15–16,20–21,24,49,53,56 Additionally, the literature regarding posture and its association with common musculoskeletal disorders such as neck and low back pain have been challenged in the past.65–69 Therefore, the rationale proposed by many authors regarding restoration of “postural balance” and terms such as “re-energize” and “reprogramming the central engram to restore muscle length”8,15–16,20–21,24,49,53,56, should be challenged due to the lack of supporting evidence that postural changes actually occur in the management of NTOS.

The purported clinical rationales from the studies in this scoping review have all been developed from a biomechanical viewpoint (e.g., restoring proper posture, correcting muscular imbalances, restoring normal joint motion and correcting faulty breathing patterns). However, we believe that embracing a biopsychosocial approach based on the existing literature for common musculoskeletal disorders such as low back pain, may also help to explain why exercise rehabilitation may be effective for the management of NTOS. These reasons may include, improvements in pain self-efficacy, better pain coping strategies, decrease in fear avoidance behavior, increase in “affordances” or action opportunities that the individual has to perform daily activities, desensitization of nociceptive structures by temporarily avoiding provocative positions, improvements in tissue tolerance and capacity through progressive overload and gradual exposure, exercise-induced analgesia via descending noxious inhibitory control mechanisms and positive contextual factors related to the clinician-patient interaction.60,70–73

Limitations

There were several limitations of this scoping review that are important to consider. Articles that were not published in the English language and articles that involved a post-operative rehabilitation program were not included. Therefore, some articles may have been missed. Additionally, there were disagreements between authors during the article screening processes as to what was deemed “sufficient detail” in the description of exercises for papers to be included in this study. Although this was settled by a third reviewer, there may have been some useful articles not included due to the vague description of exercises provided. Lastly, our search strategy although comprehensive, was done only in the PubMed database. More robust evidence from randomized controlled trials is needed to establish the efficacy of exercise intervention for the management of NTOS. Future research may also seek to compare different exercise dosages, compare the efficacy of one exercise type to another and consider other rationales such as improvements in fear-avoidance behavior, pain coping strategies or contextual factors that may explain the mechanisms behind exercise therapy for the management of NTOS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our scoping review included forty-seven articles that described various exercise protocols for the treatment of NTOS which included stretching and strengthening of the surrounding thoracic outlet musculature, postural training, nerve gliding, scapular focused exercises, aerobic conditioning and breathing exercises. As the studies in this review consisted mainly of literature reviews, retrospective and prospective cohort studies, case series, case studies, and clinical commentaries with no randomized control trials found, clinicians remain limited to utilizing clinical opinion when formulating and prescribing exercise protocols for the management of NTOS. Future randomized controlled trials are necessary to help delineate whether one form of exercise is superior to another, as well as to determine preferred exercise dosage with respect to the management of NTOS or whether movement in general, coupled with behavior modification and pain coping strategies suffice.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge and thank Mr. Kent Murnaghan for his assistance in the search strategy and Dr. Brian Budgell and Dr. Gagandeep Aheer in their guidance for this scoping review.

Footnotes

The authors have no disclaimers, competing interests, or sources of support or funding to report in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic outlet syndromes: a plea for conservatism. Neurosurgery Clin North Am. 1991;2(1):235–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilbourn AJ. The thoracic outlet syndrome is overdiagnosed. Arch Neurol. 1990;47(3):328–330. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530030106024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mailis A, Papagapiou M, Vanderlinden RG, Campbell V, Taylor A. Thoracic outlet syndrome after motor vehicle accidents in a Canadian pain clinic population. Clin J Pain. 1995;11(4):316–324. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199512000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Illig KA, Rodriguez-Zoppi E, Bland T, Muftah M, Jospitre E. The incidence of thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;70:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illig KA, Donahue D, Duncan A, Freischlag J, Gelabert H, Johansen K, Thompson R. Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(3):23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balderman J, Holzem K, Field BJ, Bottros MM, Abuirqeba AA, Vemuri C, Thompson RW. Associations between clinical diagnostic criteria and pretreatment patient-reported outcomes measures in a prospective observational cohort of patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66(2):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo CC, Bukry SA, Alsuleman S, Simon JV. Systematic review: The effectiveness of physical treatments on thoracic outlet syndrome in reducing clinical symptoms. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2011;29(2):53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhn JE, Lebus VGF, Bible JE. Thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(4):222–232. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-13-00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. A review of the literature. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43(1):55–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson LA, Pizzari T, Balster S. Thoracic outlet syndrome part 2: conservative management of thoracic outlet. Man Ther. 2010;15(4):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balderman J, Abuirqeba AA, Eichaker L, et al. Physical therapy management, surgical treatment, and patient-reported outcomes measures in a prospective observational cohort of patients with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2019;70(3):832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosby CA, Wehbé MA. Conservative treatment for thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand Clin. 2004;20(1):43-vi. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(03)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanif S, Tassadaq N, Rathore MF, Rashid P, Ahmed N, Niazi F. Role of therapeutic exercises in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2007;19(4):85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laulan J. Thoracic outlet syndromes. The so-called “neurogenic types”. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2016;35(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novak CB. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30(2):175–188. doi: 10.1016/s0094-1298(02)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JH, Zager EL. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):897–903. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000137333.04342.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford FA., Jr Thoracic outlet syndrome. Surg Clin North Am. 1980;60(4):947–956. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thevenon A, de la Barge de Certeau AC, Wieczorek V, Allart E, Tiffreau V. Efficacy of intensive, hospital-based rehabilitation in cases of thoracic outlet syndrome that failed to respond to private-practice physiotherapy. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2020;33(4):545–552. doi: 10.3233/BMR-170906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christo PJ, McGreevy K. Updated perspectives on neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome [published correction appears in Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011 Apr; 15(2): 85–7] Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(1):14–21. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sucher BM. Thoracic outlet syndrome – a myofascial variant: Part 2. Treatment. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1990;90(9):810–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aligne C, Barral X. Rehabilitation of patients with thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 1992;6(4):381–389. doi: 10.1007/BF02008798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale WA, Lewis MR. Management of thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Surg. 1975;181(5):575–585. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197505000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novak CB. Conservative management of thoracic outlet syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;8(2):201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobrusin R. An osteopathic approach to conservative management of thoracic outlet syndromes. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1989;89(8):1046–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak CB, Collins ED, Mackinnon SE. Outcome following conservative management of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20(4):542–548. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh MT. Therapist management of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Hand Ther. 1994;7(2):131–144. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(12)80083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindgren KA. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome: a 2-year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(4):373–378. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abe M, Ichinohe K, Nishida J. Diagnosis, treatment, and complications of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Orthop Sci. 1999;4(1):66–69. doi: 10.1007/s007760050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadat U, Weerakkody R, Varty K. Thoracic outlet syndrome: an overview. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2008;69(5):260–263. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2008.69.5.29356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sucher BM, Heath DM. Thoracic outlet syndrome – a myofascial variant: Part 3. Structural and postural considerations [published correction appears in J Am Osteopath Assoc 1993 Jun; 93(6): 649] J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93(3):334–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehbé MA, Schlegel JM. Nerve gliding exercises for thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand Clin. 2004;20(1):51-vi. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(03)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGough EC, Pearce MB, Byrne JP. Management of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1979;77(2):169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenny RA, Traynor GB, Withington D, Keegan DJ. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a useful exercise treatment option. Am J Surg. 1993;165(2):282–284. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson AB. Thoracic outlet syndrome in aquatic athletes. Clin Sports Med. 1999;18(2):361–378. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nichols D, Seiger C. Diagnosis and treatment of a patient with bilateral thoracic outlet syndrome secondary to anterior subluxation of bilateral sternoclavicular joints: a case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29(7):562–571. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2012.757684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindgren KA, Manninen H, Rytkönen H. Thoracic outlet syndrome – a functional disturbance of the thoracic upper aperture? Muscle Nerve. 1995;18(5):526–530. doi: 10.1002/mus.880180508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichols AW. Diagnosis and management of thoracic outlet syndrome. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8(5):240–249. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181b8556d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown C. Compressive, invasive referred pain to the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(173):55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strukel RJ, Garrick JG. Thoracic outlet compression in athletes a report of four cases. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6(2):35–39. doi: 10.1177/036354657800600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robey JH, Boyle KL. Bilateral functional thoracic outlet syndrome in a collegiate football player. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2009;4(4):170–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheon RP. Repetitive strain injury. 2. Diagnostic and treatment tips on six common problems. The Goff Group Postgrad Med. 1997;102(4) doi: 10.3810/pgm.1997.10.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindgren KA, Rytkönen H. Thoracic outlet syndrome: A functional dysfunction of the upper thoracic aperture? J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 1997;8(3):191–197. doi: 10.3233/BMR-1997-8303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li N, Dierks G, Vervaeke HE, et al. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):962. doi: 10.3390/jcm10050962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leffert RD. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2(6):317–325. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boezaart AP, Haller A, Laduzenski S, Koyyalamudi VB, Ihnatsenka B, Wright T. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2010;4(2):27–35. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.70817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine NA, Rigby BR. Thoracic outlet syndrome: biomechanical and exercise considerations. Healthcare (Basel) 2018;6(2):68. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanders RJ, Annest SJ. Pectoralis minor syndrome: subclavicular brachial plexus compression. Diagnostics (Basel) 2017;7(3):46. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics7030046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith KF. The thoracic outlet syndrome: a protocol of treatment*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1979;1(2):89–99. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1979.1.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aktas I, Kaya E, Akpinar P, et al. Spasticity-induced pectoralis minor syndrome: a case-report. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2020;27(4):316–319. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2019.1691807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pesser N, Goeteyn J, van der Sanden L, et al. Feasibility and outcomes of a multidisciplinary care pathway for neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome: a prospective observational cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021;61(6):1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fitzgerald G. Thoracic outlet syndrome of pectoralis minor etiology mimicking cardiac symptoms on activity: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(4):311–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Press JM, Young JL. Vague upper-extremity symptoms? Phys Sportsmed. 1994;22(7):57–64. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1994.11947668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patetta MJ, Naami E, Sullivan BM, Gonzalez MH. Nerve compression syndromes of the shoulder. J Hand Surg Am. 2021;46(4):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campbell RM. Thoracic outlet syndrome in musicians – an approach to treatment. Work. 1996;7(2):115–119. doi: 10.3233/WOR-1996-7206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karas SE. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Clin Sports Med. 1990 Apr;9(2):297–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peet RM, Henriksen JD, Anderson TP, Martin GM. Thoracic-outlet syndrome: evaluation of a therapeutic exercise program. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1956;(9):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Booth J, Moseley GL, Schiltenwolf M, Cashin A, Davies M, Hübscher M. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskel Care. 2017;15(4):413–421. doi: 10.1002/msc.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parsons S, Harding G, Breen A, Foster N, Pincus T, Vogel S, Underwood M. Will shared decision making between patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and physiotherapists, osteopaths and chiropractors improve patient care? Fam Pract. 2011;29(2):203–212. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hickey BW, Milosavljevic S, Bell ML, Milburn PD. Accuracy and reliability of observational motion analysis in identifying shoulder symptoms. Man Ther. 2007;12(3):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright AA, Wassinger CA, Frank M, Michener LA, Hegedus EJ. Diagnostic accuracy of scapular physical examination tests for shoulder disorders: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;47(14):886–892. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lange T, Struyf F, Schmitt J, Lützner J, Kopkow C. The reliability of physical examination tests for the clinical assessment of scapular dyskinesis in subjects with shoulder complaints: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;26:64–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shoulder function and 3-dimensional kinematics in people with shoulder impingement syndrome before and after a 6-week exercise program. Phys Ther. 2004;84(9):832–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turgut E, Duzgun I, Baltaci G. Effects of scapular stabilization exercise training on scapular kinematics, disability, and pain in subacromial impingement: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(10):1915–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christensen ST, Hartvigsen J. Spinal curves and health: a systematic critical review of the epidemiological literature dealing with associations between sagittal spinal curves and health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(9):690–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Damasceno GM, Ferreira AS, Nogueira LAC, Reis FJJ, Andrade ICS, Meziat-Filho N. Text neck and neck pain in 18–21-year-old young adults. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):1249–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghamkhar L, Kahlaee AH. Is forward head posture relevant to cervical muscles performance and neck pain? A case–control study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019;23(4):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jun D, Zoe M, Johnston V, O’Leary S. Physical risk factors for developing non-specific neck pain in office workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In Arch Occup Environ Health. 2017;90(5):373–410. doi: 10.1007/s00420-017-1205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Slater D, Korakakis V, O’Sullivan P, Nolan D, O’Sullivan K. “Sit up straight”: time to re-evaluate. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther”. 2019;49(8):562–564. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stilwell P, Harman K.Contemporary biopsychosocial exercise prescription for chronic low back pain: questioning core stability programs and considering context J Can Chiropr Assoc 2017.Mar6116–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coninx S, Stilwell P. Pain and the field of affordances: an enactive approach to acute and chronic pain. Synthese. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Macedo LG, Smeets RJEM, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Graded activity and graded exposure for persistent nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):860–879. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Powell J, Lewis JS. Rotator cuff-related shoulder pain: is it time to reframe the advice, you need to strengthen your shoulder? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(4):156–158. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2021.10199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]