Abstract

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and their ethical obligation as researchers, the authors of this paper report the following disclosures. Dr. Asarnow receives grant, research, or other support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the American Psychological Foundation, the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Division 53 of the APA), and the Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. She has consulted on quality improvement for suicide/self-harm prevention and depression, serves on the Scientific Council of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and the Scientific Advisory Board of the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation. Drs. Asarnow, Goldston, Tunno, and Inscoe receive funding from a SAMHSA UCLA-Duke National Child Traumatic Stress Network Center grant, the purpose of which is to train, implement, and disseminate the intervention described in this report. There are no commercial conflicts of interest. Drs. Pynoos and Tunno receive funding from the National Center of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, SAMHSA. Lastly, Dr. Robert Pynoos is the Chief Medical Officer of Behavioral Health Innovations, LLC, which licenses and receives payment for the use of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5.

Suicide was the second leading cause of death for adolescents and young adults, ages 10 to 24, in the United States in 2017; and in contrast to other leading causes of death, youth suicide rates increased by 56% from 2007 to 2017 (from 6.8 per 100,000 to 10.6 per 100,000) (Curtin & Heron, 2019). Suicide attempts (SAs) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) are among the strongest predictors of future SAs (Asarnow et al., 2011b; Wilkinson et al., 2011), and SAs and self-harm are associated with higher risk of suicide death (Ribeiro et al., 2016), underscoring the importance of effective care for self-harm (SAs, NSSI, and self-harm with unclear intent) for suicide prevention.

Individuals, including adolescents, who die by or attempt suicide and those who engage in NSSI have elevated rates of traumatic stress exposure, underscoring the importance of a trauma-informed approach to suicide prevention (Harford, Yi, & Grant, 2014; Martin, Dykxhoorn, Afifi, & Colman, 2016; Stein et al., 2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). In a general population study, for example, it was estimated that the prevalence of SAs would have been reduced approximately 50% among women and 33% among men if childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and witnessing domestic violence had not occurred (Afifi et al., 2016). Furthermore, evidence suggests that SA risk increases as the number of traumas experienced increases, which is also partially mediated by depressive and substance use symptoms (Dube et al., 2001; Duke et al., 2010). Rates of traumatic stress exposure are also elevated among individuals who die by suicide (Castellví et al., 2017), and among youths presenting to Emergency Departments with suicide attempts and/or ideation with results of one study indicating that over half of these youths (52.6%) screened positive for post-traumatic stress reactions (Asarnow et al., 2008).

This article highlights key issues to consider in developing and delivering effective, trauma-informed suicide prevention services for children and adolescents (hereafter referred to as youth). Rooted in the evidence on suicide prevention and care for traumatic stress (SAMHSA, 2014; National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force, 2012), and our experience as clinicians and researchers working with this population, the current manuscript bridges these literatures to offer clinical guidance on trauma-informed suicide prevention. We begin with brief reviews of our approach to trauma-informed care and acute care for youths presenting with suicidal ideation or behavior, proceed to a case illustration, and conclude by highlighting how acute interventions aimed at decreasing suicide and self-harm risk can be enhanced through a trauma-informed approach. While originally developed for emergency department (ED) services, our approach can be used in outpatient, school, crisis, or other community services when there is a need to assess and address suicide/self-harm risk.

Trauma-Informed Suicide Prevention

Due to frequent co-occurrence of traumatic stress and suicidal/self-harm thoughts and behavior, ideally SAFETY-A is delivered within the context of a trauma-informed clinic/organization or service system (see Figure 1). Trauma-informed services are defined as those in which providers and organizational systems promote an awareness of the widespread impact of trauma and the potential paths for recovery (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2016). Clinicians working within such trauma-informed systems are able to recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma, respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into their practices, and seek to prevent re-traumatization and exposure to secondary stresses. Figure 1 highlights key steps in developing a trauma-informed approach to emergency/acute care for suicidal ideation, behavior, or self-harm. This collaborative approach aims to: establish safety for the youth and family members; recognize and address signs of traumatic stress; mobilize youth, family, and community resources to ensure optimal care; and when needed, link to specific assessment and therapeutic approaches to address trauma (SAMHSA, 2014; National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force, 2012). Although we describe the steps in a sequential manner, attention to each step is crucial throughout the integrated assessment and intervention process. This trauma-informed approach aims to promote safety and prevent any potential unintended re-traumatization (SAMHSA, 2014).

Figure 1.

Key steps and considerations in trauma-informed care for youths presenting with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-harm.

Acute Care: SAFETY-Acute (A)/The Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP)

SAFETY-A, also known as the FISP, offers a useful tool for further evaluating and caring for youths who may be suffering from suicidal thoughts/behavior and trauma exposure.1 Similar to emergency care for asthma and other medical illnesses where response to emergency treatment is used to determine subsequent care strategies (Pollart, Compton, Elward, 2011), SAFETY-A provides a brief youth and family-centered therapeutic assessment that aims to treat the emergency/presenting problem, strengthen youth safety, and consistent with objective 8.4 of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), increase the likelihood that the youth will receive needed follow-up care. SAFETY-A also provides further assessment of “imminent risk” to inform clinical decision-making regarding disposition and further treatment, notably whether the youth is safe to be discharged to home or requires hospitalization.

SAFETY-A is a developmentally informed approach to safety planning that begins by assessing and building upon youth and family strengths, providing education regarding emotions and how they can escalate and become painful and dangerous, and then turns to strategies for down-regulating unsafe behavior and reactions while protecting the youth. The clinician presents a series of tasks or challenges and works to “drag out” behaviors from the youth and parents that are incompatible with SAs and self-harm (including SAs and NSSI). These challenges include the ability to: 1) identify three strengths in the youth and family/environment; 2) consider emotional reactions using an emotional thermometer; 3) engage in safety planning in which the youth identifies skills/strategies that can be used instead of self-harm; 4) identify at least three individuals that the youth can go to for help staying safe; and 5) commit to using the safety plan instead of self-harm behavior. Because we find that some youths have negative reactions to the concept of a “safety plan” based on prior experiences with the term (e.g. used because they were “bad”), we encourage clinicians to use their best judgments regarding whether to call the plan a “safety plan,” “personal plan,” or some other term that the youth considers helpful. The goal is to provide a blueprint to guide the youth through difficult times safely and skillfully; it is important that youths view the approach as helpful and work collaboratively with the clinician to develop a plan they can and will use.

Recognizing the importance of parents/caregivers (hereafter referred to as parents) in protecting the youth, SAFETY-A also assesses family protective processes and the degree to which parents are able to keep the youth safe given the variety of risk and protective factors that may be present (e.g. bullying, traumatic stress exposure, threats of violence, parent depression). Considerations include whether parents can: 1) recognize three strengths in the youth and family/environment; 2) commit to restricting access to dangerous self-harm methods (e.g. firearms, medicines and poisons) and increasing supportive monitoring to provide protective supervision when it is not possible to reduce access to potentially deadly self-harm methods (e.g. ligatures that could be used in hanging); and 3) evidence the ability to support the youth in safety plan use. If a parent is listed on the safety plan, this may involve direct responses that are viewed by the youth and parent as increasing safety (e.g. walking the dog together). However, there are times when youths are unwilling to include the parent on the safety plan due to family conflict, shame, and/or past history of trauma or neglect. In these instances, the parent’s role may be to respond with support, avoid responding in ways that make the youth feel more intense unsafe emotions, and when appropriate assist the youth in reaching other responsible adults who can help the youth to stay safe (e.g. aunt, grandma, therapist, emergency services). Since traumatic stress and other risk factors affect both youths and families, sensitivity to signs of traumatic stress or other risk factors in both youths and parents is important, as is observation for signs of traumatic stress in other settings (extended family, school, peers, internet, neighborhood). Suicide and suicidal behavior also run in families (Brent & Mann, 2005; Melhem et al., 2007). Consequently, it is important to assess and monitor for suicide risk in parents and other involved family members.

SAFETY-A uses a cognitive-behavioral model and incorporates principles from Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993; Miller, Rathus & Linehan 2007). Importantly, there is an emphasis on finding a balance between acceptance and change strategies, with an emphasis on accepting the youth and family, helping them to radically accept what has occurred (the past), while focusing on the “present” and building lives they want to live despite traumatic and/or other stresses they may have suffered. At the same time, there is an emphasis on changing behaviors and strengthening skills to respond safely and effectively, protecting the youth, and strengthening healing resources (e.g. obtain follow-up mental health treatment). When youth are not offered guaranteed access to follow-up treatment, or do not attend scheduled care visits, caring contacts (usually by phone) are used to motivate and support linkage to treatment and problem-solve barriers to treatment attendance.

Randomized controlled trials have shown that SAFETY-A (referred to as the FISP in this literature) is associated with improved rates of linkage to follow-up care after treatment for a suicidal episode in the Emergency Department (ED; Asarnow et al., 2011a). This is a critical first step for receiving effective treatment, and when combined with free access to an evidence-informed outpatient treatment, is associated with lower rates of subsequent SAs and improved clinical outcomes (Asarnow, Hughes, Babeva, & Sugar, 2017; Babeva, Klomhaus, Hughes, Fitzpatrick, & Asarnow, 2019; Rotheram-Borus, Piacentini, Cantwell, Belin, & Song, 2000; Asarnow, Berk, Hughes, & Anderson, 2015). Data from two independent groups evaluating early intervention effects further support clinical improvements after intervention delivery. In a quasi-experimental trial evaluating an earlier version of SAFETY-A (called the Specialized Emergency Room Intervention; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1996), post-intervention assessments conducted at ED discharge indicated significantly lower levels of suicidal ideation and depression in youths, compared to youths receiving Usual ED care during an earlier time period. Similarly, in an open trial, we found that after SAFETY-A significant improvements (moderate to large effect sizes) were seen in: youths’ confidence that they could keep themselves safe; parents’ confidence that they could keep the youth safe; and youth self-harm urges, intent to attempt suicide, unhappiness, and hopefulness (Zullo et al., 2020).

In the section below, we provide a case example of a youth with a history of trauma who presents to the ED after a suicide attempt and is treated using SAFETY-A in a trauma-informed manner. To ensure confidentiality, this example is developed as a point of illustration to highlight key steps and challenges in providing trauma-sensitive acute care for suicidal behavior and self-harm.

Case Illustration.

Brianna is a 15-year-old female who presented to the ED accompanied by her mother following a SA by overdose. She had a history of sexual assault at age 13 by her mother’s ex-boyfriend. At age 14, Brianna made a SA by overdose, after which it was discovered that she had been engaging in cutting/NSSI since the assault. Brianna participated in a 6-month course of supportive psychotherapy combined with medication treatment (fluoxetine) for major depressive disorder. Symptoms resolved and medication treatment was discontinued the summer before presenting with this second SA. Her symptoms re-emerged when school started. Brianna became increasingly withdrawn as she lost interest in spending time with friends and family, was cutting/NSSI, had difficulties concentrating and sleeping, and experienced increased anxiety and headaches. These symptoms adversely impacted Brianna’s academic performance.

The presenting overdose/SA occurred after school when Brianna was alone at home. When Mother came home from work she thought Brianna was sleeping, but when she had difficulty waking, Mother called 911 and Brianna was brought to the ED. Following medical treatment and clearance for the overdose, the ED mental health clinician conducted the standard hospital risk assessment, then proceeded to a therapeutic assessment and intervention using SAFETY-A in a trauma-informed manner.

The youth and mother were seen together to set the agenda and review confidentiality limits. See Table 1 for list of session components/tasks. Consistent with a trauma-informed approach, the clinician greeted Brianna and Mother in an empathic and welcoming manner and checked on how Brianna and Mother were doing while providing orientation to the room and process (e.g., showed bathroom locations, set agenda/expectations for session, described session goals) to increase predictability, transparency, and a collaborative approach. The clinician briefly reviewed the session plan, letting them know that he would be seeing each of them individually followed by some time together, and reviewed confidentiality issues. Since Mother indicated that she hadn’t had a chance to eat, the clinician suggested that Mother go to the cafeteria for about 30 minutes while he met with Brianna providing directions to the cafeteria.

Table 1.

Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP) - Checklist of Tasks

|

FAMILY TOGETHER Agenda Setting with Youth & Parents/Significant Others □ Introduce self, provide contact info (if appropriate) □ Set agenda □ Review limits of confidentiality □ Obtain contact information for family (use Locator Form) □ Provide emergency contact numbers (clinicians and emergency services) |

|

YOUTH ALONE Help youth to: □ Generate self-strengths □ Generate family strengths (if applicable) □ Identify risk situations & understand emotional responses using feeling thermometer □ Develop Personal/SAFETY Plan □ Identify and problem-solve barriers to safety plan use □ Limit access to self-harm/lethal methods □ Counsel regarding disinhibiting effects of substance use |

|

PARENTS ALONE (if applicable) □ Elicit any concerns from parents □ Counsel regarding restricting access to dangerous/potentially lethal self-harm methods □ Counsel regarding importance of protective support, parental monitoring, and supervision □ Counsel regarding disinhibiting effects of substance use □ Discuss supporting youth in using safety plan □ Counsel regarding risk factors for suicide/self-harm □ Generate youth strengths □ Generate family strengths |

|

FAMILY TOGETHER

Increasing Family Support and Positive Interaction □ Elicit youth strengths from youth and parent(s) □ Elicit family strengths from youth and parent(s) □ Review Action/SAFETY Plan □ Identify and problem-solve barriers to safety plan use □ Obtain commitment to use SAFETY Plan/Support youth in using plan |

|

Establish Initial Commitment to Treatment

□ Address any identified treatment barriers □ Obtain commitment to attend next session |

| □ Schedule Next Session or provide information for scheduling

□ Follow-up contacts to support attendance in follow-up treatment, continue until successfully linked to care |

After Mother left, Brianna appeared apprehensive and averted eye contact. The clinician shared that he knew this had been a difficult time and asked if there was anything he could do to make her more comfortable. When she did not respond, he assured Brianna that if at any point she felt upset, wanted to take a break or didn’t want to answer a question, she should let him know. He explained that his goal was to work with Brianna as a “team” to find ways to help turn things around for her so that she could feel safe and could have the kind of life she wanted to live, while acknowledging that sometimes life can be painful and unfair. The clinician again reminded Brianna of the limits of confidentiality, and stressed that if there was anything she was uncomfortable sharing, she should let him know.

Consistent with the goal of building on youth and family strengths and promoting hope and reasons for living, the clinician stated that he knew this had been a very tough day and he wanted to begin by getting to know her a bit. He asked Brianna to describe herself, the kinds of things she enjoys, and any personal attributes or accomplishments that she feels good about. Brianna indicated that she knew she was smart and was able to do well at school when she was not feeling so depressed. Brianna said that she felt “really bad” and that this was making it hard to focus in school. The clinician noted that difficulty focusing in school can make things really hard, and also noted that he could see that Brianna was a sensitive observer of feelings and the way feelings impacted her. Brianna acknowledged this indicating that she was very sensitive. The clinician asked if this sensitivity was ever helpful and allowed her to be particularly supportive and caring with friends. Brianna said she had a close girlfriend, Ali, who she cared a lot about, adding that she and Ali had good talks and they both knew a lot about music. The clinician gently asked if Brianna was saying that she is a sensitive and good friend and that she also knows her music, leading to a moment of joining with Brianna in a discussion of her latest favorite song. Brianna acknowledged these strengths.

The clinician then asked if there were strengths in Brianna’s family. Brianna indicated that her Mom worked hard, she knew her Mom loved her, and that they had good times together watching movies or television. The clinician shared that despite how tough things had been, Brianna had strengths and things she valued in herself and family. Brianna shyly agreed.

Next, the clinician introduced the emotional thermometer as a tool to discuss and develop awareness of emotions, and how different feeling states are experienced in terms of body signs, thoughts, and actions or behaviors. Together they examined Brianna’s emotions and how her emotions escalate and move her towards a “danger zone” where Brianna might be at risk for hurting herself like when she took the overdose. The clinician asked Brianna to show him where she was on the emotional thermometer right now, explaining the anchors of the emotional thermometer: 0 was as calm and good as she could feel; 10 was as upset as she could feel; and 5 was in the middle. (See Figure 2 for Brianna’s emotional thermometer.) Brianna indicated that she had been up higher earlier but now she was somewhere between a 6 and 7. She described feeling tension in her body and kept thinking that she had added to her mother’s problems by taking the pills. Earlier when she took the pills, Brianna stated that she was at a 10, felt like she couldn’t stand it, like she wanted to crawl out of her body, her head was throbbing and she was feeling guilty about everything. She took the pills and hoped that the pain would stop, she didn’t care if she died and thought the pills might kill her. The clinician acknowledged how painful this must have felt and asked Brianna to describe how she felt earlier in the morning before she went to school. Brianna noted that she hadn’t slept well and had a hard time getting up, describing her emotional state in the morning at about a 7– a little worse then she feels now. When she started to think about going to school she felt more tension, her stomach and head hurt, and she was thinking “all I want is to go back to bed and sleep.” Her mother made her get up and go to school and when she got to school, she saw her friend Ali and felt a little better, maybe a 5, as they were talking and making plans for the weekend. Then Brianna went into class and saw this boy who had been bothering her. She started to feel tense again, her headache came back, and she couldn’t focus. Brianna made it through the day but then when she went home, she was alone. She looked online and saw someone had posted a nasty comment about her. This made her emotional temperature shoot up, she couldn’t get the comment out of her mind. She felt like she was useless, no good, and just made extra problems for her family. She tried cutting, but that made her feel worse. Memories of the sexual assault by her mother’s ex-boyfriend emerged and she felt even more worthless. Brianna just wanted the headache and everything else to stop, to go to sleep, and make everything go away. She went into the bathroom to get some pills for her headache, and she found herself taking one pill after another until she had taken the whole bottle.

Figure 2.

Brianna’s Feeling Thermometer

Gently, the clinician guided Brianna in describing what happened after she took the pills. Brianna indicated that she went to her bed and lay down, hoping she would fall asleep and never wake up as this would stop the pain. She fell asleep and woke up when she was in the hospital; there were nurses around who told her that she was in the hospital and that they would take care of her. Brianna was disappointed. She had hoped that the pills would end it, but she was still alive and in the hospital. Her mother was sitting on a chair crying. She asked Brianna why she had taken the pills. Brianna felt ashamed and could feel tears welling up. Brianna said she felt awful that she caused pain for her mother.

The clinician turned to the period when Brianna transitioned from school to home and said: “So when you first got to school your temperature was at a 7, when you talked to your friend Ali and made plans for the weekend, your temperature went down to a 5, and then when you saw the boy your temperature went back up to a 7. Where was your temperature when you got home?” Brianna indicated that her temperature had started climbing and was probably near an 8; she was feeling lonely, her head hurt, and she had so much homework. She went online because she didn’t feel like doing her homework, and when she saw what Jason had posted about her, her temperature shot up to a 9. She felt like she couldn’t take it anymore, her head was throbbing, and all she wanted was for the pain to stop. She remembered this movie she had watched where a girl had killed herself and this seemed like it stopped the pain. The pills were there and Brianna took all the pills in the bottle.

Next, the clinician asked: “I know this has been a rough time and some time has passed. How are you feeling now about taking the pills? How much do you feel like you want to live?” Brianna indicated that she wasn’t really sure. If things were going to be as bad as they were, it might be better off if she were dead, but she knew that this would be awful for her mother. The clinician then inquired about whether Brianna was willing to see if they could find a way to make things better and build a life that Brianna would want to live. Brianna said she wasn’t sure, but she was willing to give it a try.

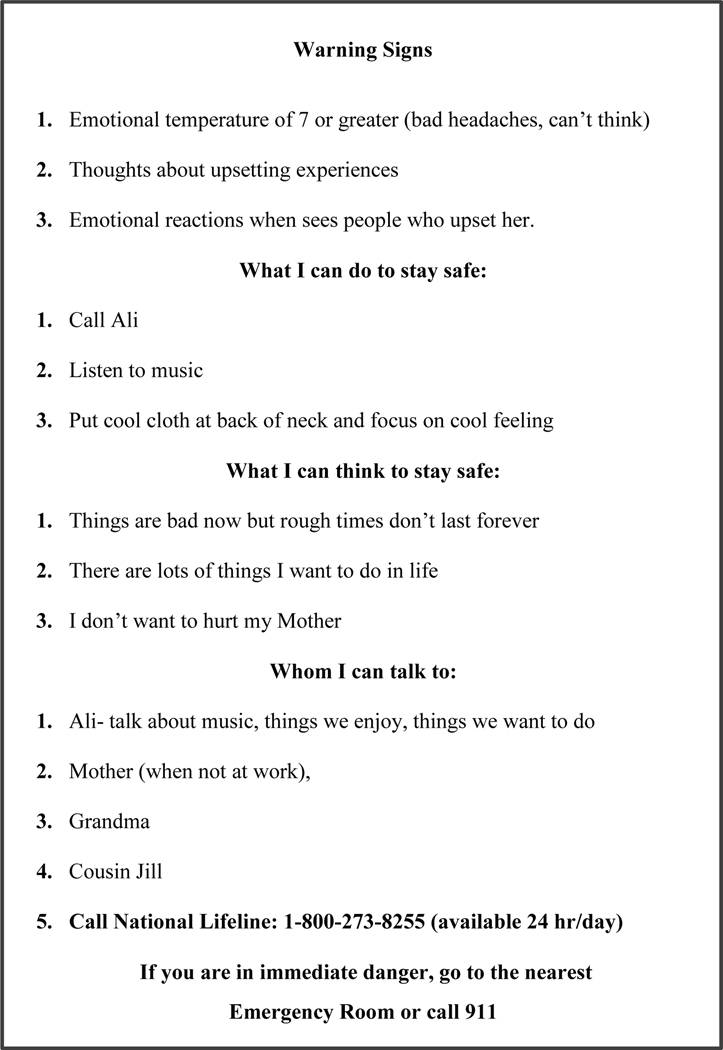

The clinician brought out the “safety plan card” (Figure 3) and asked Brianna if she would be willing to work with him to find ways that she could cope when her emotional temperature was rising to a danger point. Brianna agreed. Mindful of Brianna’s potential discomfort with physical proximity, particularly as the clinician was a male and her assault had been by a male, the clinician asked permission before sitting next to her to collaboratively work on her plan. The clinician said, “So it sounds like when your temperature starts to move towards a 7, that means things are really rough. I wonder if we could come up with some things that you can do at those times that would help?” He reminded Brianna that when her temperature was a 7 at school and she talked to her friend about plans for the weekend, her temperature went down to a 5. He asked Brianna if talking to a friend or someone else would work at these times. Brianna said that talking to her friend Ali might help. The clinician asked whether talking about anything with Ali would help her feel better, or whether there were certain topics that helped. Brianna indicated that talking to Ali about anything other than the problem and boy at school usually helped. They then went to the safety plan card and listed Ali as the first person she could contact and noted - talk about things they enjoyed, like music, or things they wanted to do. The clinician acknowledged that it was great that she had a friend like Ali, but also stressed the importance of talking with an adult if she started to have suicidal urges again, as they would be in a better position to know how to help her. He asked Brianna if there were other people, especially adults, who she could contact when she was alone and her temperature was moving towards an unsafe point. Brianna indicated that she could call her Grandmother who lived nearby or her mother – but only if she wasn’t at work. Brianna was concerned that she shouldn’t bother her mother at work. The clinician asked if Brianna couldn’t reach Ali or her grandmother, and mother was at work, who else she might call. Ali had difficulty thinking of anyone, but added a 20-year-old cousin that was close to the family. The clinician added the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, letting her know that this is a number that she can call any time of the day or night and someone will be there who can help.

Figure 3.

Brianna’s Safety Plan

Next, the clinician and Brianna reviewed things that could get in the way of Brianna contacting these individuals. Brianna indicated that she might not call because she wouldn’t want to bother Ali, her mother, or grandmother, leading to a discussion of how Brianna might approach these calls and things she could do (e.g. offering to help with dinner so mother would have less to do when she came home). The clinician also reminded Brianna that the National Lifeline was always there for her, and that the people who answered were there to help.

Considering other actions and thoughts that could help Brianna to lower her emotional temperature, Brianna noted that when she had a bad headache placing a cool cloth at the back of her neck sometimes helped, and listening to music can help. These were added to the action section of the safety plan.

Next, the clinician asked about thoughts that could help Brianna get through rough times, noting that there were lots of different ways to think about things and while Brianna’s thoughts were perfectly natural, there might be other ways of thinking about things that would also be true and could help her to focus on thoughts that helped her get through stressful times. Together they collaborated on identifying “safe thoughts” that would help Brianna to lower her emotional temperature and decided on: “things are bad now, but rough times don’t last forever,” “there are lots of things I want to do in life,” and “I don’t want to hurt my mother like that.” These thoughts were listed on the safety plan card.

Brianna then said, “sometimes I think about things I did in the past that I feel bad about.” Adopting a trauma-informed stance, the therapist noted that this can be difficult and hard to talk about, and asked whether talking about these thoughts made her temperature go up. Brianna said she didn’t like talking about these thoughts as it makes her feel bad. The clinician asked where her temperature was now. Brianna indicated a 7 but stated “I feel like if I talk about the thoughts my temperature will shoot up to a 9 or 10.” The clinician suggested that these thoughts could be warning signs for Brianna to use her safety plan, noting that with time these kinds of thoughts can be easier to deal with as really they are only “thoughts” as tough as they are. He explained that most of us have things we did or happened to us that we feel bad about. Brianna noted that for her these thoughts were really bad and these thoughts were one of the things that led her to take the pills. The clinician and Brianna decided that these kinds of thoughts were warning signs that Brianna’s temperature was about to reach the danger zone and given how tough these thoughts were right now, it would be best if Brianna went to her safe people at those times and was not alone.

The clinician gently noted that he was aware of her history that she mentioned in passing, specifically that when Brianna was younger she had been sexually assaulted. He suggested that the kinds of thoughts she was having often occurred when individuals have been victims of assault, adding that he was sorry that this had happened to Brianna and that his hope was that with treatment Brianna would be better able to cope with these sorts of thoughts and reminders. He added that he knows others who have suffered in ways similar to Brianna and with time and working with a therapist they came to feel stronger and went on to build lives they wanted to live. The clinician respectfully noted that Brianna is the only one who really knows what she experiences, and he wants her to know that it is possible to heal, and he will do what he can to help that healing happen.

At this point, Brianna noted that the boy who had upset her at school, which led to her temperature rising to a 7, had come on to her sexually at a party in an aggressive way and this had really upset and frightened her. Observing for signs of distress and agitation, the clinician listened to Brianna as she described the incident and her suicidal thoughts and urge. Brianna explained that she frequently had feelings of guilt and disgust, and when these feelings came up, she tended to withdraw from friends and family. The clinician was mindful of his own reactions, maintaining a nonjudgmental and safe environment while simultaneously avoiding asking unnecessary questions. He validated Brianna’s distress while acknowledging the strength she had to share her feelings and reaction. Using the emotional thermometer, he checked with Brianna about her current distress level using a matter-of-fact approach. Because Brianna indicated that her temperature had increased to a 7, the clinician led Brianna in practicing a brief coping skill from her personal plan (e.g., putting a wet cloth on the back of her neck while focusing mindfully on the cool feeling of the cloth on her neck). After this practice, Brianna said her temperature was now at 5, she felt better, but was worried that she could have these reactions again, as her reaction to the boy was fast and unexpected. Brianna stated that she knew that she could keep herself safe at school, but she still felt upset when she saw this boy. She stated that whenever she saw him, she was reminded of the party and her history. The clinician acknowledged that these thoughts and memories can be really hard and at the same time it was good to know that she did know how to keep herself safe so that she could continue to be a caring and sensitive friend, continue to develop her knowledge of music, and help her mother out and share good times together.

Returning to the safety card, the clinician guided Brianna in considering what some other warning signs might be. Brianna indicated that when she had thoughts about what happened to her or saw certain boys she had these intense reactions and thoughts of suicide. Together, the clinician and Brianna listed “reactions that occurred when she saw people who upset her,” “thoughts about upsetting experiences,” an “emotional temperature of 7 or above,” and “bad headache” as warning signs on Brianna’s safety plan. Care was taken to carefully choose wording that would not be a problem if her mother or others saw her safety plan, and a decision was made to write “upsetting thoughts and situations” on the emotional thermometer rather than a specific reference to thoughts of abuse or situations that reminded her of the abuse.

Grounded in the emotional thermometer work, the clinician and Brianna went through the safety plan card. The clinician worked to draw out the strategies from Brianna, checked with Brianna on whether these strategies would really work, and barriers to using listed strategies were discussed and problem-solved. Throughout the session, the clinician worked to acknowledge and reinforce effective actions, adaptive coping, strengths, and safe and skillful decision-making while also striving to understand Brianna’s situation and experiences and empower and support Brianna in building a life that she wants to live. Before concluding the safety plan work, the clinician checked on Brianna’s commitment to using the safety plan rather than hurting herself or attempting suicide. Unlike the “safety contracts” that have little evidence supporting efficacy (Garvey et al., 2009), the goal here was to realistically consider with Brianna whether she was willing to try to use a safety plan rather than self-harm if her emotional thermometer reached a danger point. Brianna indicated that she would use the safety plan, as she really didn’t want to die. The clinician then asked how long a commitment to safety she could make. Brianna thought about this and then said three months. When the clinician inquired about what could get in the way, she stated that she might cut, indicating that sometimes cutting helped stop her suicidal thoughts. The clinician responded that he understood, yet it was also clear that cutting had actually resulted in her feeling worse on the day of the overdose. He then asked whether Brianna would be willing to use the safety plan when she had the urge to cut, as well as at times when she felt suicidal, indicating that this would help her to discover what strategies worked best for staying safe. Briana agreed. The clinician asked what might get in the way of her using the safety plan if the urge to cut became strong, and after reviewing the safety plan Brianna decided that when the urge got too strong she would call or go to Ali or one of the people on her card. Brianna also indicated that she might lose the card. This was problem-solved and Brianna decided to take a photo of the safety plan with her phone, as Brianna “always had her phone with her.” The clinician asked Brianna about her comfort level in sharing her plan with her mother, noting that Brianna’s mother was on the plan. Brianna agreed that sharing the safety plan with her mother could make it easier for her to go to her mother when she was upset.

The clinician explained that therapy could help her to stay safe and build the kind of life she wants to have. Brianna stated that she would like to have someone to talk to, and the clinician said he would help her to find someone to work with in therapy. He also noted that he knew that alcohol and drugs tended to be around, and that it was important, given how she had been feeling, that she keep a clear head as she was still having painful emotions, urges to cut, and thoughts of suicide, noting that even a little bit of alcohol or marijuana could make it harder for her to control her emotions and behavior. Brianna said she understood and would not use. When asked for a time commitment, Brianna said three months same as the safety plan.

Leaving Brianna under staff observation, the clinician went to the mother and began the parent-only part of the session. He set the agenda and identified concerns that the mother wanted to discuss. Brianna’s mother said she was frightened by what happened and she really wanted to know why Brianna would do this. The clinician wrote down the mother’s concern, stating that he could see how frightening this must be for the mother and that the goal today was to understand what had happened and to work together to do what they could to make sure that Brianna did not take pills again, or try to hurt herself, while helping her to see that she can have a life that she wants to live. The mother said she wondered whether the problem was due to the sexual assault, stating that she felt so guilty for not knowing that her ex-boyfriend was a “bad man,” what had happened was awful, and she felt it was her fault. Tearfully, the mother said, “I should have known.” The clinician handed mother a box of tissues and said “I can see how much you care for your daughter and how badly you wish you could have prevented this from happening; however, it is not possible to prevent all bad things from happening as much as we try.” At the advice of a family friend, the mother said she reported the incident to the Department of Social Services, although by that time, her ex-boyfriend had already moved out of the area. The clinician praised her for this action and noted that Brianna did tell her what happened, which indicated that Brianna viewed her mother as someone who would protect her. Importantly, when Brianna told her mother what happened she believed her, protected her, got her help, made sure this man was out of their lives and couldn’t hurt Brianna, and helped to prevent him from hurting others by reporting the incident.

Next, the clinician stated “It is often helpful to start with what is going well and the strengths that you see in Brianna,” and asked Mother what strengths she could identify in her child. She indicated that Brianna was a “good girl,” smart, always tried hard, and helps her around the house. After writing down these strengths on a card, the clinician asked Mother about strengths in the family. She responded by saying that it was really just the two of them now, but they did things together when there was time, like cooking, shopping, and watching movies or television. The clinician wrote down the listed family strengths and thanked Mother for sharing this information. He noted that this would help them to build on Brianna’s strengths and help her to focus on what was going well in her life, to feel hopeful about the future, and reasons for staying safe and alive. Further, the clinician stated that it sounds like sometimes Brianna turns to Mother for help as she did after the assault, which is another very important strength, and one that was important to encourage as if she had told Mother how she was feeling before she took the pills, he was sure that Mother would have protected and supported her. Mother tearfully said: “Yes, I still don’t understand why she would do such a thing.” The clinician noted that it is hard to understand and asked Mother if it would be helpful to focus today on what could be done to prevent Brianna from taking pills or hurting herself again. Mother nodded yes as she wiped her eyes. The clinician explained that he and Brianna had worked together to develop what we call a “safety plan” that listed things Brianna could do if she felt unsafe in the future to prevent dangerous behavior like taking the pills. The clinician emphasized that a major goal today was to work with Brianna to allow Mother to support her in using the safety plan and staying safe. Mother indicated that this was what she wanted to do and that she didn’t understand why Brianna hadn’t called her. The clinician said that this can be hard for parents and at the same time it is not uncommon for teenagers to try to handle things on their own, adding: “We learned today that Brianna does need your help and our goal is to help Brianna to ask for and accept your help.”

The clinician indicated that he didn’t want to frighten Mother, but that we know that once kids make a suicide attempt, like Brianna did, they are at risk for future suicide attempts and even death if they use a deadly method like firearms. Mother quickly said there were no firearms in the home, stating that her ex-boyfriend who had hurt Brianna had guns but thankfully he is gone and there were no guns. The clinician indicated that this was reassuring and asked about medications and other potentially dangerous methods of self-harm in the home. Mother indicated there were medicines around, stating that even if she locked everything up Brianna could buy medicines or find them at her friend’s houses. Respectfully, the clinician agreed and reinforced mother for her attention to this risk, while also noting that it is important to make it harder for Brianna to get access to medicines or other dangerous methods at a time when she is feeling really bad and thinking of killing herself. He noted that most of the time, suicidal feelings pass with time, and by making it hard for Brianna to get to dangerous and potentially deadly suicide methods quickly, she would be safer. Together, the clinician and mother considered what medicines and household poisons (e.g. pesticides, bleach) could be eliminated and which would need to be secured. The mother committed to securing all dangerous prescription and over the counter medications and poisons, as she did not want Brianna to overdose again or hurt herself in another way. Mother agreed to locking up these items in a location that Brianna would not know about. The clinician also reminded mother that it was a good idea to limit plastic bags, ropes, or other items that could be potentially deadly. Mother agreed to eliminate or lock up as feasible, but again noted that she couldn’t possibly find everything that could be dangerous and that Brianna could hide things in her room. The clinician agreed that this was true and that staying close to Brianna and watching her, much as you would with a younger child can also help to keep her safe. Mother indicated that Brianna often wanted to go to her room alone and got upset if the mother knocked on the door. The clinician stated that this was not uncommon, and at the same time given the overdose that brought Brianna to the ED, it seemed like Mother’s only real option is to watch her closely and supportively, and perhaps enlist others to help with the monitoring. Together, the clinician and mother thought through danger points during the day when Brianna might be unsupervised, reminding mother that the overdose occurred when Brianna was alone at home because mother gets home from work later than Brianna returns from school. A plan was developed to enlist other family members (Grandmother, Aunt, older Cousin) to assist with supportive monitoring, as Brianna enjoyed being with these other family members and particularly enjoyed spending time with her Grandmother and older cousin.

The clinician then said that another thing mother could do to help Brianna to recover and be safe was to bring her to treatment after the appointment today. Mother indicated that Brianna had been to therapy in the past and it had helped, but she was worried that she couldn’t find a therapist, explaining that Brianna’s previous therapist had left and she had been hard to find. The clinician indicated that he would help them get an appointment, underscored the seriousness of Brianna’s suicide attempt, and that therapy was important for helping to keep Brianna safe. Clearly grateful for the clinician’s help, Mother thanked the clinician for the help arranging an appointment and assured him that she would get Briana to the therapy appointment.

Next, the clinician noted the importance of watching for signs of substance use. He explained that alcohol and drug use were common in kids Brianna’s age and because these substances make it harder to control your emotions and behavior, if Mother saw any signs of substance use she would want to engage in more protective actions and communicate with the therapist about this. The clinician reviewed the strengths Mother had identified in Brianna, handed her the card summarizing the strengths identified in Brianna and the family, and let Mother know that the plan was for Mother to share these strengths with Brianna in the next family part of the session. The clinician asked Mother whether she was ready to have Brianna join the session, share these strengths with Brianna, and help work with Brianna to develop and use the safety plan. Mother indicated she was ready. After checking with Mother to confirm that her concerns had been adequately addressed for now, they went to join Brianna.

The family part of the session began with the clinician greeting Brianna warmly and stating that he wanted to begin by asking Mother to share some strengths that she has noticed in Brianna. Mother shared that Brianna is a caring and smart girl, who worked hard, and was very helpful. Mother added that she loved Brianna and wanted to be there for her. Brianna smiled shyly. The clinician encouraged Mother to look at the card listing the strengths. She then added, “Brianna it is good that you are able to ask for help. I like that you go to me or Grandma, people you can count on to help.” The clinician then asked Brianna to share some strengths she saw in the family. Brianna stated that she knew her mother cared about her, was there for her, and they had good times together watching movies and television.

Next, the clinician asked Brianna to share what she felt comfortable sharing from her safety plan, explaining that he and Brianna had worked at identifying times when her feelings became very distressing and finding things she could do to feel better and respond safely. He explained that we use an emotional thermometer kind of like a regular thermometer to watch for dangerous emotional states and for Brianna, a 7 or above on a 10-point thermometer, with 10 being the worst she could feel, is a sign that Brianna needs to use her safety plan. He asked Brianna to share what she could do at those times and placed the safety plan card face-down on a table in front of Brianna. Without referring to the safety plan card, Brianna described activities (listen to music, call someone, put a cool cloth on the back of her neck) and thoughts (e.g. things will get better, there are lots of things I want to do in life) as listed on the safety plan. She turned over the safety plan card and described the thought “I don’t want to do that to my mother.” Her mother said: “Yes, I am glad to hear that. I would never be the same. I would be devastated.” Brianna went on to describe people she could go to (the last section of the safety plan card) and stated: “I can call Ali or another friend, and Mom I know I can go to you if you are not at work, or Grandma, and if I can’t get in touch with you, I can always call cousin Jill.” Mother added: “Brianna you can call me any time even if I am at work.” Brianna expressed her concern that Mother would get in trouble at work. Mother responded: “No I won’t. My boss will understand. I want you to call if you need me. I am always there for you.” Brianna, and her mother practiced using the safety plan in session and problem solved barriers to implementation, Brianna told her mother what she would and would not like her to do if she came to her for support. “Don’t ask questions; if you are at home help me get involved in something- like watching a movie together. If you are at work and can’t talk tell me. I will feel better just having talked to you and will call Grandma.” With the clinician’s support, Brianna role-played going to mother. Brianna decided that she could say “yellow” to communicate that she was moving towards a danger point and asking for mother’s help with distraction, and mother then listed a series of movies to watch. They then practiced watching a video on the phone mindfully, with the therapist noting that thoughts can drift and when they do the idea is to simply notice the drift and bring her attention back to the movie. The clinician asked whether this seemed like a plan that Brianna could use and Brianna confirmed her commitment to using the plan rather than trying to hurt herself. Brianna and mother were reminded of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, explaining that either of them could call and that someone was there all the time. He said he knew other people who had used these emergency lines and found them helpful. Brianna and mother decided that they would let Grandma know that she might call and if she did Grandma should stay with her until mother got home. They were both reminded that until Brianna was feeling better and had lots of practice using the safety plan to get through rough moments, medicines would be locked up to keep Brianna safe, and that Brianna could ask mother if she needed a medicine. Brianna reluctantly agreed. The session ended by scheduling a follow up appointment the next day at the outpatient clinic, with the clinician again emphasizing the importance of follow-up treatment. After the scheduled outpatient session, the clinician called and mother reported that both she and Brianna had liked the therapist and weekly therapy was planned.

Discussion

The frequent co-occurrence of traumatic stress exposure and suicidal behavior underscores the need for trauma-informed suicide prevention. As in many youths presenting with suicidal behavior, Brianna’s suicide attempt was associated with reminders of the traumatic stress. In Brianna’s case, interactions with a boy at school triggered thoughts of the sexual assault. The emphasis on evaluating and mobilizing strengths in the youth and family at the start of the intervention likely made it easier for Brianna to share thoughts regarding the assault and enhanced the clinician’s ability to sensitively support Brianna, activate her strengths, and build hope that treatment could help her to feel less helpless should she experience similar reactions in the future.

Issues in the parent-youth relationship related to Brianna’s assault by the mother’s ex-boyfriend were also addressed through the family focused nature of the intervention and the in-session role play. Mother continued to experience guilt that she was not able to protect her daughter, and feared that Brianna’s difficulties were her fault. Through reinforcing strengths in the mother-daughter relationship, encouraging Mother to play a key role in Brianna’s safety plan, and practicing this within the session, the intervention offered healing opportunities where Mother was able to begin to repair her fear/concern that she could not protect her daughter. Conversely, at the beginning of the session, Brianna expressed a concern about burdening Mother if she went to her for protection, which places Brianna at increased risk for danger. The intervention offered an opportunity for Brianna to seek and obtain protection from Mother, as Brianna explained what she needed to stay safe (safety plan) and Mother demonstrated an ability to help in ways that Brianna felt were helpful. This approach allowed a “corrective” interaction where Briana sought and Mother provided protection. The focus on protective support, supervision, and restricting access to dangerous self-harm methods gave Mother additional opportunities to demonstrate to herself and Brianna that she could and would protect and support Brianna.

By expanding the assessment to the broader social support system, Mother and Brianna were able to consider others who could help with protection and support, recognizing that Mother’s work schedule was a real barrier to her being home when Brianna finished school - a high risk time for Brianna. Fortunately, both Brianna and Mother felt comfortable with the grandmother and older cousin as additional protective adults and they were included in the safety plan. This can be challenging when the social support system is limited, yet there are often providers (primary care, mental health), school personnel (teachers, counselors), and other community contacts (e.g. religious leaders, coaches) who can help to strengthen protective influences. While youth often list peers as individuals they would go to for support, research has underscored the importance of support from responsible adults (King et al., 2019; Wyman et al., 2019)

The developmentally-informed safety planning process in SAFETY-A builds on knowledge of youth and family strengths, and collaborative learning between the youth and clinician regarding the youth’s emotional reactions. Through the emotional thermometer task, Briana recognized that a temperature of 7 was her danger point, or yellow zone, when using her safety plan was important for staying safe. Understanding how emotions are experienced and the ability to label and respond to potentially dangerous emotional reactions can facilitate use of the safety plan, as well as recognition of times when emotions are so intense (in the red zone) that the strategy is to go to someone for protection. The emotional thermometer also provided a quick way of communicating that she needed help staying safe (I’m at yellow-7) which does not require explanations and discussion of stressors which could intensify emotional distress.

From a developmental perspective, incorporating learning about emotional reactions into the safety planning process is particularly important for adolescents and younger children who can have difficulty recognizing and responding adaptively to intense rapid emotional escalations. While this provides an additional step compared to approaches tested in adults (Stanley, Brown et al., 2018), the emotional thermometer task flows into safety planning, leading to better understanding and ability to use the safety plan with little to no additional time. Discussion of youth and family strengths also provides information for identifying strategies and family members or other protective adults that can be included in the safety plan, while setting a caring and validating tone at the start of the session. This may be particularly important with youth given the power differential between youth and adults. Finally, our strong focus on parents and other adults for protective support and monitoring acknowledges that youth need protection and nurturing.

SAFETY-A provides a structured approach for considering and addressing risk factors while working to enhance protective processes with the goal of preventing future suicidal/self-harm behavior. This intervention structure (Table 1) highlights key areas to be considered and also includes a number of clinical choice points, specifically: how much time to allot to youth versus parent and family work, whether to include other individuals within the session, and how much time to spend in role plays to practice using the Safety Plan and trouble-shooting barriers to care. Time often dictates how sessions will flow and in Brianna’s case, time was not an issue. Therefore, time was balanced across time with Brianna and Mother individually, and time with Brianna and Mother together. When possible, clinicians use in-session role plays and trouble-shoot obstacles to safety plan use with the goal of increasing the likelihood that the safety plan will be used in times of risk. While we could have had Brianna or Mother contact her grandmother or cousin to strengthen the safety planning process, given the commitment and plan for Brianna and Mother to follow-up with Grandma, this was not pursued in session.

As noted above, time is a major consideration in acute evaluations of suicide risk, particularly in emergency settings where time and staffing is often limited, and there is a need for a quick assessment of whether the youth requires hospitalization. SAFETY-A can generally be completed within 50–90 minutes, and there are billing codes for crisis psychotherapy (Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) 90839 and 90840) that allow extended time. However, SAFETY-A is most helpful for youths who are assessed as moderate to low risk based on initial evaluation; as some youths initially assessed as moderate risk and in need of hospitalization, may be assessed as safe to go home with a strong follow-up plan after the SAFETY-A intervention. Indeed, Brianna’s initial description of wanting to be dead when she woke up and her uncertainty about whether she wanted to live would likely have led to hospitalization without the intervention. Through SAFETY-A, however, Brianna shifted towards greater hopefulness, an expressed desire to live, and commitment to using the safety plan rather than suicidal behavior; and her mother demonstrated a commitment to keeping Brianna safe. This case illustration is consistent with data from our dissemination efforts indicating that following SAFETY-A clinicians have increased comfort sending some youth home, parents report feeling more confident about their abilities to keep their children safe, and youth report increased ability to keep themselves safe. Still, it is important to note that Brianna was discharged home with a follow-up appointment within 48 hours and the safety plan included emergency procedures for youth and Mother (Figure 3).

When SAFETY-A is not delivered in conjunction with guaranteed access to follow-up care, a major consideration is linkage to follow-up treatment. Briana is at high-risk for repeat suicidal behavior after two suicide attempts. Consistent with life-threatening behavior as the top treatment priority (Linehan, 1993; Miller et al., 2007; Asarnow et al., 2017), therefore, there is a need for evidence-based suicide prevention care. Briana also suffers from traumatic stress reactions and reminders of her sexual assault were part of the chain leading up to her SA, underscoring the importance of evidence-based trauma-informed care and interventions aimed at addressing her response to reminders and other traumatic stress symptoms. Because a large proportion of youth presenting with suicide risk never link to follow-up care after an emergency visit, SAFETY-A uses caring follow-up phone contacts to motivate and support linkage to care. We found that nearly all youths (92%) receiving SAFETY-A were linked to follow-up treatment and attended more treatment sessions, compared to usual care (Asarnow et al., 2011a).

Finally, although our case illustration involves a youth presenting to the ED, SAFETY-A has been used across a variety of service settings (outpatient, school, crisis services, hospital) and with patients with varying levels of suicide-risk. This requires some adaptation. For instance, in schools contact with parents is often limited, resulting in less intensive assessment and intervention with parents which may lead to more youth triaged to emergency services for further evaluation. With youths where risk is lower (e.g. youth with no active suicidal ideation and NSSI), SAFETY-A has been conducted across two sessions: an initial session to assess youth safety, build hope, engage in safety planning, and commit to safety plan use to stay safe, plus assessment of parents ability to keep youth safe and counseling regarding reducing access to potentially dangerous self-harm methods; and a second session involving further assessment of safety and the youths ability to effectively use the safety plan, refinement of the safety plan, and work with the youth and parent together to support safety plan use and build hope and reasons for living.

Concluding Remarks

Our developmentally and trauma-informed approach to acute care for suicidal and/or self-harm episodes builds on strengths in youth and families, works to mobilize hope and reasons for living, and emphasizes a balance between acceptance and change, with clinicians supporting youth and parents in radically accepting what has happened in the past and the need to turn to the present and build a life that they want to live. At the same time, change strategies are needed to enhance safety through identifying and practicing strategies for safe coping, and helping parents take actions to protect their children such as restricting access to potentially dangerous self-harm methods and increasing protective and supportive monitoring/supervision. This developmentally-informed approach recognizes that youth are embedded in families and dependent on their parents and other adults in their environments for protection. Recognizing that working with youth who suffer from suicidal tendencies, self-harm, and traumatic stress can create burn out and secondary stress in clinicians, we also call for embedding care within trauma-informed service systems and organizations that attend to the needs of the clinicians who care for these youth as well as the youth we serve.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Disclosures: The work in this paper was partially supported by the UCLA-Duke Center for Trauma-Informed Adolescent Suicide, Self-Harm, and Substance Abuse Treatment & Prevention (ASAP Center), a partner in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). The ASAP Center and NCTSN are funded by the Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (SM #080041). Dr. Pynoos is Co-Director of the UCLA-Duke National Center within the NCTSN. Partial support of Dr. Asarnow’s time was provided by NIMH R01 MH112147. Points of view in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions or policies of the listed funding agencies.

Footnotes

In the literature we previously used the name “Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP) for the intervention, but referred to the intervention as SAFETY with patients to convey our focus on maximizing safety. We feel that it is preferable to refer to the intervention as SAFETY-Acute (A) for the following reasons. 1) The intervention is an acute care/emergency intervention focused on safety, making the SAFETY-Acute (A) name more informative. 2) SAFETY-A/FISP is the first session of the more intensive 12-session SAFETY intervention which has been shown to be associated with reduced suicide attempt risk in two treatment development trials (Asarnow et al, 2015; Asarnow et al., 2017), and SAFETY-A refers to this first acute treatment session. 3) Some children live with non-family caregivers (e.g. children presenting from residential treatment centers), making the title Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP) inaccurate in some cases where family members are unavailable and other adults participate in the intervention.

References

- Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, & Sareen J (2008). Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), 946–952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, Grob C, Devich-Navarro M, Suddath R, … & Tang L. (2008). Pediatric emergency department suicidal patients: two-site evaluation of suicide ideators, single attempters, and repeat attempters. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 958–966. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799ee8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, Grob CS, Devich-Navarro M, Suddath R, … Tang L (2011a). An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 62(11), 1303–1309. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Berk M, Hughes J, & Anderson N (2015). The SAFETY Program: A Treatment-Development Trial of a Cognitive-Behavioral Family Treatment for Adolescent Suicide Attempters. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 194–203. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.940624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, & Sugar CA (2017). Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Vitiello B, Keller M, Birmaher B, … Brent DA (2011b). Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(8), 772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babeva KN, Klomhaus AM, Sugar CA, Fitzpatrick O, & Asarnow JR. (2020).. Adolescent suicide attempt prevention: Predictors of response to a cognitive-behavioral family and youth centered intervention. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brent D & Mann J (2005). Family genetic studies, suicide, and suicidal behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 133(1), 13–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellví P, Miranda‐Mendizábal A, Parés‐Badell O, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, … Alonso J. (2017). Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(3), 195–211. doi: 10.1111/acps.12679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC & Heron M (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 352. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH (2001). Childhood abuse household dysfunction and risk of attempted suicide throughout the lifespan: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Journal of American Medical Association, 286(24), 3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, & Borowsky IW (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), e778–e786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey KA, Penn JV, Campbell AL, Esposito-Smythers C, & Spirito A (2009). Contracting for safety with patients: Clinical practice and forensic implications. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37(3), 363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Yi HY, & Grant BF (2014). Associations between childhood abuse and interpersonal aggression and suicide attempt among US adults in a national study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Arango A, Kramer A, Busby D, Czyz E, Foster C, & Gillespie B (2019). Association of the Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents with 11- to 14-year mortality outcomes: Secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 492–498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for bordering personality disorder. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Dykxhoorn S, Afifi J, & Colman T (2016). Child abuse and the prevalence of suicide attempts among those reporting suicide ideation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(11), 1477–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1250-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem N, Brent D, Ziegler M, Iyengar S, Kolko D, Oquendo M, … Mann J. (2007). Familial Pathways to Early-Onset Suicidal Behavior: Familial and Individual Antecedents of Suicidal Behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(9), 1364–1370. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Rathus J, & Linehan MM (2007). Dialectical Behavior Therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force. (2012). Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. Core curriculum on childhood trauma. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2016). What is a trauma-informed child and family service system? Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- Pollart SM, Compton RM, & Elward KS (2011). Management of acute asthma exacerbations. American Family Physician, 84(1). 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleinman EM, Chang BP, & Nock MK (2016). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 225–236. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Piacentini J, Cantwell C, Belin TR, & Song J (2000). The 18-month impact of an emergency room intervention for adolescent female suicide attempters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 1081–1093. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown G, Brenner L, Galfalvy H, Currier G, Knox K, … Green K (2018). Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention With Follow-up vs Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(9), 894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Hwang I, Kessler RC, Sampson N, Alonso J, … Nock MK (2010). Cross-national analysis of the associations between traumatic events and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. PLOS One, 5(5), e10574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. SMA 14–4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). 2012 national strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, & Goodyer I (2011). Clinical and Psychosocial Predictors of Suicide Attempts and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman P, Pickering T, Pisani A, Rulison K, Schmeelk‐Cone K, Hartley C, … Valente T (2019). Peer‐adult network structure and suicide attempts in 38 high schools: Implications for network‐informed suicide prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1065–1075. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullo L, Meza JI, Rolon-Arroyo B, Vargas S, Venables C, Miranda J, & Asarnow JR (2020). Enhancing safety: Acute and short-term treatment strategies for youths presenting with suicidality and self-harm. The Behavior Therapist.