Abstract

Background. Infective Endocarditis (IE) is a severe condition. Diabetes mellitus (DM) has been associated with a poor prognosis in other settings. Our aim was to describe the profile and prognosis of IE with and without DM and to analyze the prognostic relevance of DM-related organ damage. Methods. Retrospective analysis of the Spanish IE Registry (2008–2020). Results. The cohort comprises 5590 IE patients with a mean age of 65.0 ± 15.5 years; 3764 (67.3%) were male. DM was found in 1625 patients (29.1%) and 515 presented DM-related organ damage. DM prevalence during the first half of the study period was 27.6% vs. 30.6% in the last half, p = 0.015. Patients with DM presented higher in-hospital mortality than those without DM (521 [32.1%] vs. 924 [23.3%], p < 0.001) and higher one-year mortality (640 [39.4%] vs. 1131 [28.5%], p < 0.001). Among DM patients, organ damage was associated with higher in-hospital (200 [38.8%] vs. 321 [28.9%], p < 0.001) and one-year mortality (247 [48.0%] vs. 393 [35.4%], p < 0.001). Multivariate analyses showed an independent association of DM with in-hospital (odds ratio [OR] = 1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.16–1.55, p < 0.001) and one-year mortality (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.21–1.59, p < 0.001). Among DM patients, organ damage was independently associated with higher in-hospital (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.06–1.76, p = 0.015) and one-year mortality (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.26–2.01, p < 0.001) Conclusions. The prevalence of DM among patients with IE is increasing and is already above 30%. DM is independently associated with a poor prognosis, particularly in the case of DM with organ damage.

Keywords: infective endocarditis, diabetes mellitus, prognosis, in-hospital mortality, one-year mortality, organ damage

1. Introduction

Infective Endocarditis (IE) is a severe disease with high in-hospital mortality [1,2]. Almost one third of IE patients present diabetes mellitus (DM) [2,3,4,5]. DM has been associated with a poor prognosis in sepsis [6,7,8]. An association of DM with prognosis in IE patients has also been described [1,4]. However, DM is associated with advanced age, comorbidities, atypical clinical presentation, and longer IE diagnosis time, among other characteristics that have a strong prognostic influence in IE [2,3,4,5]. Due to that reason, the independent association of DM with IE mortality is unclear [3,4]. Some authors have suggested an independent association [1] while other data do not support it [3].

Our aim was to describe the profile and prognosis of IE with and without DM and to analyze the prognostic relevance of DM-related organ damage. We also studied the evolution of the yearly prevalence of DM in these patients.

2. Methods

The Spanish Collaboration on Endocarditis—GAMES (Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la Endocarditis Infecciosa en España)—is a national observational registry that has been previously described [9,10,11]. Multidisciplinary teams that compose this group, including infectious disease physicians, cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, microbiologists, echocardiographers, and other imaging specialists, prospectively completed standardized case report forms with information regarding IE episodes and follow-up data. A complete list of GAMES members is shown in Acknowledgments. IE patients were consecutively included at 38 Spanish hospitals between January 2008 and December 2020. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of definite or probable IE by modified Duke criteria [12]. IE management, including the decision to perform surgery and the type of surgery, was done by the local medical team following the 2009 and 2015 European Society of Cardiology recommendations [13]. DM was diagnosed based on the American Diabetes Association criteria [14]. DM-associated organ damage was considered to be present after analyzing clinical and laboratory techniques, as well as image data. For instance, renal disease with albuminuria and/or reduced glomerular filtration rate in the absence of signs or symptoms of other primary causes of kidney damage, neuropathy with loss of protective sensation, and neovascularization and/or vitreous/preretinal bleeding (in addition to non-proliferative retinopathy) [15].

This study complies with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of participating centers.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are summarized as means ± standard deviations (SD) or medians, and interquartile ranges, when a normal distribution was not observed, as per the Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test; categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Student‘s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, or paired t-test were used to compare continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses (backward selection) were performed to determine mortality predictors and to assess the independent association of DM, with and without organ damage, with mortality. All variables with p value < 0.10 in univariate analyses were included in the multivariable analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

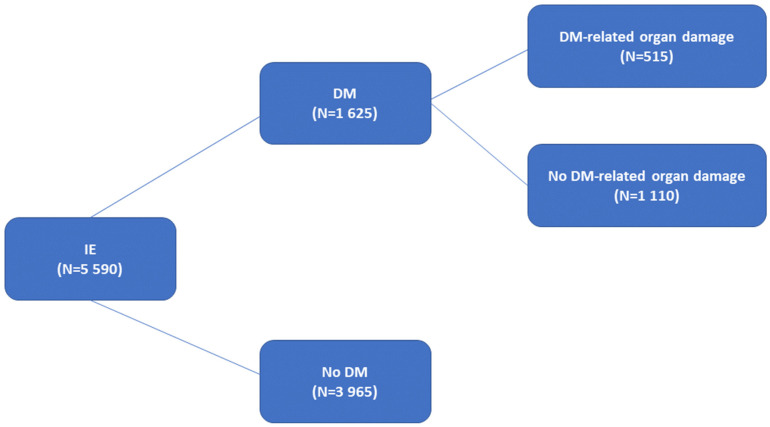

The cohort comprises 5590 IE patients with a mean age of 65.0 ± 15.5 years; 3764 (67.3%) were male. DM was found in 1625 patients (29.1%) and 515 presented DM-related organ damage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study overview. IE: infective endocarditis. DM: diabetes mellitus.

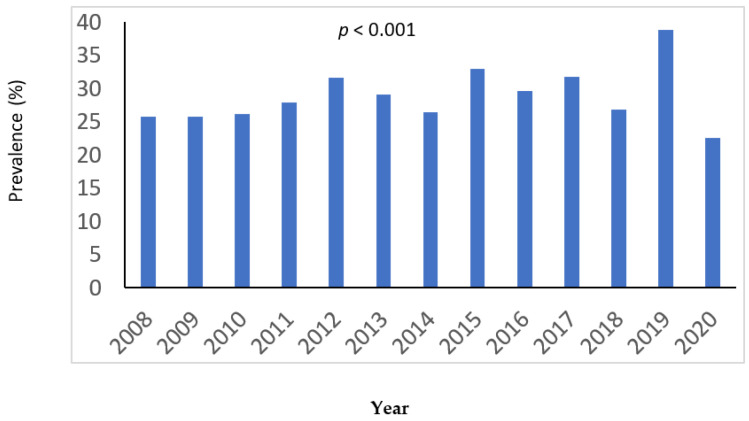

Figure 2 shows the yearly prevalence of DM during the study period. The prevalence of DM during the first half of the study period was 27.6% vs. 30.6% in the last half, p = 0.015.

Figure 2.

Yearly prevalence of diabetes during the study period.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of patients with and without DM. Compared with those without DM, DM patients presented more frequently advanced age, cardiac implantable electronic device location, nosocomial origin, cardiovascular and renal disease, and had a higher Charlson Comorbidity index. Mean age on the first 6.5 years of the study period was lower than in the last 6.5 years, both in the global population and in diabetic patients (65.0 ± 15.6 years vs. 66.2 ± 15.3 years, p = 0.004; 69.3 ± 11.2 vs. 71.0 ± 10.5, p = 0.003, respectively).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis (IE) according to the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM).

| No DM (3965) | DM (1625) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 67 (54–77) | 72 (64–78) | <0.001 |

| Male Gender (%) | 2679 (67.5) | 1085 (66.7) | 0.564 |

| Nosocomial IE (%) | 1041 (26.3) | 535 (32.9) | <0.001 |

| Health care-associated IE (%) | 306 (7.7) | 158 (9.7) | 0.014 |

| Vegetation present (%) | 2893 (73.0) | 1150 (70.8) | 0.096 |

| New heart murmur (%) | 1349 (34.0) | 477 (29.3) | 0.001 |

| Location (%) | |||

| Aortic | 2060 (52.0) | 830 (51.1) | 0.551 |

| Mitral | 1688 (42.6) | 670 (41.2) | 0.356 |

| Tricuspid | 215 (5.4) | 79 (4.9) | 0.394 |

| Pulmonary | 71 (1.8) | 8 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| PM/ICD | 349 (8.8) | 213 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Others | 113 (2.8) | 37 (2.3) | 0.229 |

| Multiple | 570 (14.4) | 227 (14.0) | 0.693 |

| Unknown | 66 (1.7) | 24 (1.5) | 0.613 |

| Native IE | 2459 (62.0) | 941 (57.9) | 0.004 |

| Prosthetic IE | 1213 (30.6) | 528 (32.5) | 0.164 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| Respiratory disease | 668 (16.8) | 379 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 877 (22.1) | 625 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 1179 (29.7) | 691 (42.5) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 286 (7.2) | 315 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 441 (11.1) | 277 (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 642 (16.1) | 254 (15.6) | 0.604 |

| Renal disease | 844 (21.3) | 586 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 370 (9.4) | 163 (10.1) | 0.443 |

| Congenital heart disease | 303 (7.6) | 38 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Native heart valve disease | 1794 (45.2) | 773 (47.5) | 0.113 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson score, median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 6 (5–8) | <0.001 |

IQR = Interquartile range; PM = Pacemaker; ICD = Implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

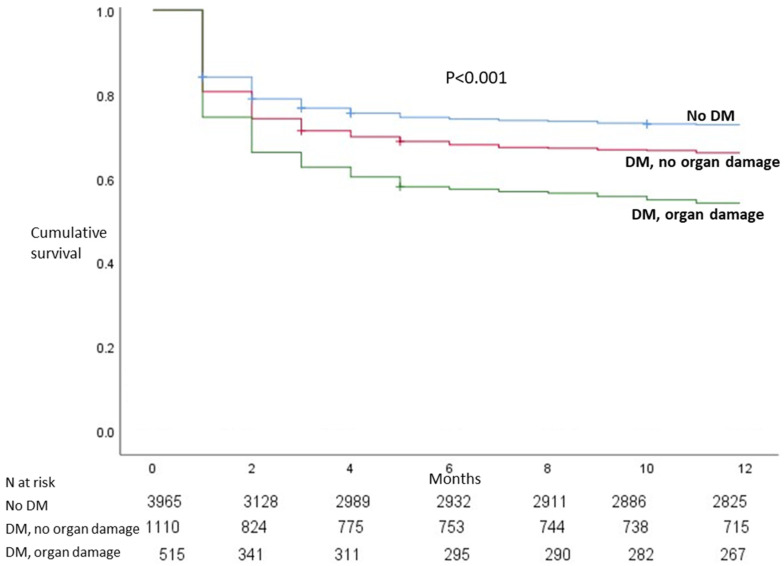

Staphylococcus and enterococcus etiology were more common among diabetics (Table 2). Table 3 shows the clinical outcome according to the presence of diabetes. Compared with those without DM, DM patients presented complications more frequently and had higher in-hospital and one-year mortality. Among diabetics, patients with DM-related organ damage were a high-risk population with a poor prognosis (Table 4 and Figure 3). Multivariate analyses showed an independent association of DM with in-hospital and one-year mortality (Table 5). In addition, among diabetics, organ damage was an independent predictor of mortality.

Table 2.

Infective endocarditis etiology according to the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM).

| Etiology (%) | No DM (3965) | DM (1625) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 836 (21.1) | 413 (25.4) | <0.001 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococcus | 680 (17.2) | 322 (19.8) | 0.018 |

| Enterococcus | 519 (13.1) | 268 (16.5) | 0.001 |

| Streptococcus | 1081 (27.3) | 346 (21.3) | <0.001 |

| Candida | 68 (1.7) | 20 (1.2) | 0.187 |

| Other Fungi | 11 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 0.837 |

| Unknown | 345 (8.7) | 112 (6.9) | 0.025 |

| Anaerobe | 52 (1.3) | 16 (1.0) | 0.311 |

| Polymicrobial | 65 (1.6) | 21 (1.3) | 0.338 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 167 (4.2) | 60 (3.7) | 0.372 |

| Other etiologies | 112 (2.8) | 34 (2.1) | 0.119 |

Table 3.

Clinical Course according to the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM).

| No DM (3965) | DM (1625) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracardiac complications (%) | 1264 (31.9) | 500 (30.8) | 0.715 |

| Valve perforation | 581 (14.6) | 203 (12.4) | 0.035 |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 248 (6.2) | 90 (5.5) | 0.308 |

| Abscess | 639 (16.1) | 283 (17.4) | 0.235 |

| Fistula | 105 (2.6) | 35 (2.1) | 0.283 |

| Vascular events (%) | 340 (8.5) | 98 (6.0) | 0.001 |

| Heart Failure (%) | 1554 (39.1) | 699 (43.0) | 0.008 |

| Persistent bacteremia (%) | 402 (10.1) | 204 (12.5) | 0.008 |

| Central nervous system involvement (%) | 750 (18.1) | 350 (21.5) | 0.025 |

| Embolism (%) | 888 (22.3) | 316 (19.4) | 0.015 |

| Renal Failure, new or worsening (%) | 1341 (33.8) | 654 (40.2) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis (%) | 632 (15.9) | 300 (18.4) | 0.022 |

| Septic shock (%) | 468 (11.8) | 226 (13.9) | 0.03 |

| Cardiac Surgery (%) | 1905 (48.0) | 707 (43.5) | 0.002 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 924 (23.3) | 521 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| One-year mortality (%) | 1131 (28.5) | 640 (39.4) | <0.001 |

Table 4.

Main differences seen in patients with diabetes according to the presence of diabetes-related organ damage.

| No Organ Damage (1110) | Organ Damage (515) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nosocomial IE (%) | 330 (29.7) | 205 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Health care-associated IE (%) | 67 (6.0) | 91 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Native IE (%) | 617 (55.6) | 324 (62.9) | 0.005 |

| Prosthetic IE (%) | 392 (35.3) | 136 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 394 (35.4) | 231 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 428 (38.5) | 263 (51.0) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease (%) | 116 (10.4) | 199 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| Stroke (%) | 168 (15.1) | 109 (21.1) | 0.003 |

| Cancer (%) | 197 (17.7) | 57 (11.0) | 0.001 |

| Renal disease (%) | 267 (24.1) | 319 (61.9) | <0.001 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson score, median (IQR) | 6 (4–7) | 8 (6–9) | <0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (%) | 219 (19.7) | 194 (37.7) | <0.001 |

| Streptococcus (%) | 278 (25.0) | 68 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac Surgery (%) | 523 (47.1) | 184 (35.7) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 321 (28.9) | 200 (38.8) | <0.001 |

| One-year mortality (%) | 393 (35.4) | 247 (48.0) | <0.001 |

IQR = Interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival according to the presence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and DM-related organ damage.

Table 5.

Independent predictor of mortality. (A) All population, in-hospital mortality. (B) All population, one-year mortality. (C) Diabetics, in-hospital mortality. (D) Diabetics, one-year mortality.

| (A) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Diabetes | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 2.6 (2.3–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 0.005 |

| S. aureus | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.002 |

| (B) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Diabetes | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) | 0.027 |

| Heart failure | 2.4 (2.1–2.8) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2.0 (1.8–2.3) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac surgery not done | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.005 |

| S. aureus | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.002 |

| (C) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Diabetes-related organ damage | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.01 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.007 |

| Female sex | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 3.2 (2.5–4.1) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2.3 (1.8–2.9) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | <0.001 |

| S. aureus | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.01 |

| (D) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Diabetes-related organ damage | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) | 0.024 |

| Heart failure | 2.7 (2.1–3.3) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | <0.001 |

OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence Interval.

4. Discussion

Our data show that the prevalence of DM among patients with IE is increasing and about 30% of patients with IE have DM. Diabetics had a poor prognosis, particularly in the case of DM with organ damage. Compared with non-diabetics, diabetic patients had comorbidities more frequently, mainly cardiovascular and renal disease. Diabetics also had a high-risk profile with more nosocomial and healthcare-related IE and more frequent S. aureus etiology. As expected, diabetics had a poor prognosis. Even after correcting for confounding factors, the association of DM with in-hospital and one-year mortality remained significant.

The prevalence of DM in the general population is increasing [16]. In our country the prevalence of DM in the general population aged 65–75 years increased from 17% in 2006 to 21% in 2017 [17]. Our study also found a similar trend in IE patients. Previous authors have suggested an increase in DM prevalence in IE patients [3,5]. Abe et al. [5] found a prevalence of 22% in 2004 that increased to 30% in 2014. The reasons that explain the increase in the prevalence of DM are unknown. Population aging may play a role. In our sample, the mean age on the last half of the study period was higher than in the first half, and this was also true in diabetic patients.

Although some previous studies suggested an association of DM with IE mortality [1,4], others did not identify DM as a prognostic factor [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The independent association of DM with prognosis is unclear and a significant age interaction could be a confounding factor [4]. On the other hand, even prediabetes has been associated with a higher mortality risk [25,26]. Although no previous studies have focused on the prognostic implications of DM-related organ damage, DM has been associated with higher rates of heart and renal failures [26] and more advanced DM stages, such as longer DM duration, insulin-treated DM [25], and higher Diabetes Complications Severity Index [27], which have been related to higher IE risk and a poor prognosis.

The relation of DM with the prognosis of IE might have several explanations. DM is associated with endothelial dysfunction which can promote stronger bacterial adhesion [28,29]. In addition, diabetics have an impaired immune response [30] and more common bacteremia with aggressive bacteria such as S. aureus [31]. Moreover, diabetics have defects of neutrophil activities [32,33,34]. Immune system dysfunction due to chronic low-grade inflammation seen in DM favors micro-organism growth, a process that contributes to sepsis progression [6,7,8].

Our work could have relevant clinical implications. Due to the poor prognosis of IE in diabetics, it might be reasonable to consider earlier and more aggressive treatments and interventions in these patients, particularly in those with previous DM-related organ damage. Close follow-up and correct glycaemia control might improve the outcome.

The limitations of this study should be noted. The retrospective design justifies that relevant variables such as type of DM, DM duration, level of glycated hemoglobin, presence of diabetic cardiomyopathy, and DM-therapy were not collected systematically. Local medical teams were responsible for IE management, including deciding on surgery, and any judgements may have been influenced by factors not registered in this study. Finally, cause of death during follow-up was not available for a large number of patients.

In any case, our data come from a large national database and show a clear association of DM with IE prognosis. Moreover, ours is the first study to compare the prognosis of IE in diabetics with and without organ damage.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of DM among patients with IE is increasing and is already above 30%. DM is independently associated with a poor prognosis, particularly in the case of DM with organ damage.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript are grateful for the collaboration of the researchers of the GAMES: Hospital Costa del Sol, (Marbella): Fernando Fernández Sánchez, Mariam Noureddine, Gabriel Rosas, Javier de la Torre Lima; Hospital Universitario de Cruces, (Bilbao): Roberto Blanco, María Victoria Boado, Marta Campaña Lázaro, Alejandro Crespo, Josune Goikoetxea, José Ramón Iruretagoyena, Josu Irurzun Zuazabal, Leire López-Soria, Miguel Montejo, Javier Nieto, David Rodrigo, Regino Rodríguez, Yolanda Vitoria, Roberto Voces; Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, (Málaga): Mª Victoria García López, Radka Ivanova Georgieva, Guillermo Ojeda, Isabel Rodríguez Bailón, Josefa Ruiz Morales; Hospital Universitario Donostia-Policlínica Gipuzkoa, (San Sebastián): Ana María Cuende, Tomás Echeverría, Ana Fuerte, Eduardo Gaminde, Miguel Ángel Goenaga, Pedro Idígoras, José Antonio Iribarren, Alberto Izaguirre Yarza, Xabier Kortajarena Urkola, Carlos Reviejo; Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, (Alicante): Rafael Carrasco, Vicente Climent, Patricio Llamas, Esperanza Merino, Joaquín Plazas, Sergio Reus; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, (A Coruña): Nemesio Álvarez, José María Bravo-Ferrer, Laura Castelo, José Cuenca, Pedro Llinares, Enrique Miguez Rey, María Rodríguez Mayo, Efrén Sánchez, Dolores Sousa Regueiro; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Huelva, (Huelva): Francisco Javier Martínez; Hospital Universitario de Canarias, (Canarias): Mª del Mar Alonso, Beatriz Castro, Teresa Delgado Melian, Javier Fernández Sarabia, Dácil García Rosado, Julia González González, Juan Lacalzada, Lissete Lorenzo de la Peña, Alina Pérez Ramírez, Pablo Prada Arrondo, Fermín Rodríguez Moreno; Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, (Málaga): Antonio Plata Ciezar, José Mª Reguera Iglesias; Hospital Universitario Central Asturias, (Oviedo): Víctor Asensi Álvarez, Carlos Costas, Jesús de la Hera, Jonnathan Fernández Suárez, Lisardo Iglesias Fraile, Víctor León Arguero, José López Menéndez, Pilar Mencia Bajo, Carlos Morales, Alfonso Moreno Torrico, Carmen Palomo, Begoña Paya Martínez, Ángeles Rodríguez Esteban, Raquel Rodríguez García, Mauricio Telenti Asensio; Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS, Universidad de Barcelona, (Barcelona): Manuel Almela, Juan Ambrosioni, Manuel Azqueta, Mercè Brunet, Marta Bodro, Ramón Cartañá, Carlos Falces, Guillermina Fita, David Fuster, Cristina García de la Mària, Delia García-Pares, Marta Hernández-Meneses, Jaume Llopis Pérez, Francesc Marco, José M. Miró, Asunción Moreno, David Nicolás, Salvador Ninot, Eduardo Quintana, Carlos Paré, Daniel Pereda, Juan M. Pericás, José L. Pomar, José Ramírez, Irene Rovira, Elena Sandoval, Marta Sitges, Dolors Soy, Adrián Téllez, José M. Tolosana, Bárbara Vidal, Jordi Vila; Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, (Madrid): Iván Adán, Javier Bermejo, Emilio Bouza, Daniel Celemín, Gregorio Cuerpo Caballero, Antonia Delgado Montero, Ana García Mansilla, Mª Eugenia García Leoni, Víctor González Ramallo, Martha Kestler Hernández, Amaia Mari Hualde, Mercedes Marín, Manuel Martínez-Sellés, Patricia Muñoz, Cristina Rincón, Hugo Rodríguez-Abella, Marta Rodríguez-Créixems, Blanca Pinilla, Ángel Pinto, Maricela Valerio, Pilar Vázquez, Eduardo Verde Moreno; Hospital Universitario La Paz, (Madrid): Isabel Antorrena, Belén Loeches, Alejandro Martín Quirós, Mar Moreno, Ulises Ramírez, Verónica Rial Bastón, María Romero, Araceli Saldaña; Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, (Santander): Jesús Agüero Balbín, Carlos Armiñanzas Castillo, Ana Arnaiz, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Manuel Cobo Belaustegui, María Carmen Fariñas, Concepción Fariñas-Álvarez, Rubén Gómez Izquierdo, Iván García, Claudia González Rico, Manuel Gutiérrez-Cuadra, José Gutiérrez Díez, Marcos Pajarón, José Antonio Parra, Ramón Teira, Jesús Zarauza; Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, (Madrid): Jorge Calderón Parra, Marta Cobo, Fernando Domínguez, Alberto Forteza, Pablo García Pavía, Jesús González, Ana Fernández Cruz, Elena Múñez, Antonio Ramos, Isabel Sánchez Romero; Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, (Madrid): Tomasa Centella, José Manuel Hermida, José Luis Moya, Pilar Martín-Dávila, Enrique Navas, Enrique Oliva, Alejandro del Río, Jorge Rodríguez-Roda Stuart, Soledad Ruiz; Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, (Granada): Carmen Hidalgo Tenorio; Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, (Sevilla): Manuel Almendro Delia, Omar Araji, José Miguel Barquero, Román Calvo Jambrina, Marina de Cueto, Juan Gálvez Acebal, Irene Méndez, Isabel Morales, Luis Eduardo López-Cortés; Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, (Sevilla): Arístides de Alarcón, Emilio García, Juan Luis Haro, José Antonio Lepe, Francisco López, Rafael Luque; Hospital San Pedro, (Logroño): Luis Javier Alonso, Pedro Azcárate, José Manuel Azcona Gutiérrez, José Ramón Blanco, Antonio Cabrera Villegas, Lara García-Álvarez, José Antonio Oteo, Mercedes Sanz; Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, (Barcelona): Natividad de Benito, Mercé Gurguí, Cristina Pacho, Roser Pericas, Guillem Pons; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, (A Coruña): M. Álvarez, A. L. Fernández, Amparo Martínez, A. Prieto, Benito Regueiro, E. Tijeira, Marino Vega; Hospital Santiago Apóstol, (Vitoria): Andrés Canut Blasco, José Cordo Mollar, Juan Carlos Gainzarain Arana, Oscar García Uriarte, Alejandro Martín López, Zuriñe Ortiz de Zárate, José Antonio Urturi Matos; Hospital SAS Línea de la Concepción, (Cádiz): García-Domínguez Gloria, Sánchez-Porto Antonio; Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia): José Mª Arribas Leal, Elisa García Vázquez, Alicia Hernández Torres, Ana Blázquez, Gonzalo de la Morena Valenzuela; Hospital de Txagorritxu, (Vitoria): Ángel Alonso, Javier Aramburu, Felicitas Elena Calvo, Anai Moreno Rodríguez, Paola Tarabini-Castellani; Hospital Virgen de la Salud, (Toledo): Eva Heredero Gálvez, Carolina Maicas Bellido, José Largo Pau, Mª Antonia Sepúlveda, Pilar Toledano Sierra, Sadaf Zafar Iqbal-Mirza; Hospital Rafael Méndez, (Lorca-Murcia): Eva Cascales Alcolea, Ivan Keituqwa Yañez, Julián Navarro Martínez, Ana Peláez Ballesta; Hospital Universitario San Cecilio (Granada): Eduardo Moreno Escobar, Alejandro Peña Monje, Valme Sánchez Cabrera, David Vinuesa García; Hospital Son Llátzer (Palma de Mallorca): María Arrizabalaga Asenjo, Carmen Cifuentes Luna, Juana Núñez Morcillo, Mª Cruz Pérez Seco, Aroa Villoslada Gelabert; Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (Zaragoza): Carmen Aured Guallar, Nuria Fernández Abad, Pilar García Mangas, Marta Matamala Adell, Mª Pilar Palacián Ruiz, Juan Carlos Porres; Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía (Cartagena): Begoña Alcaraz Vidal, Nazaret Cobos Trigueros, María Jesús Del Amor Espín, José Antonio Giner Caro, Roberto Jiménez Sánchez, Amaya Jimeno Almazán, Alejandro Ortín Freire, Monserrat Viqueira González; Hospital Universitario Son Espases (Palma de Mallorca): Pere Pericás Ramis, Mª Ángels Ribas Blanco, Enrique Ruiz de Gopegui Bordes, Laura Vidal Bonet; Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete (Albacete): Mª Carmen Bellón Munera, Elena Escribano Garaizabal, Antonia Tercero Martínez, Juan Carlos Segura Luque; Hospital Universitario Terrassa: Cristina Badía, Lucía Boix Palop, Mariona Xercavins, Sónia Ibars. Hospital Universitario Negrín (Gran Canaria): Eloy Gómez Nebreda, Ibalia Horcajada Herrera, Irene Menduiña Gallego. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria): Héctor Marrero Santiago, Isabel de Miguel Martínez, Elena Pisos Álamo. Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Madrid): Carmen Díaz Pedroche, Fernando Chaves, Santiago de Cossío, Francisco López Medrano, Mª Jesús López, Javier Solera, Jorge Solís. Hospital Universitari Bellvitge (Barcelona): Carmen Ardanuy, Guillermo Cuervo Requena, Sara Grillo, Alejandro Ruiz Majoral.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-S.; Formal analysis, M.I.B. and M.M.-S.; Investigation, P.M., S.D.l.V., M.C.F.-Á., F.A.d.l.R., E.G.-C., A.D.A., R.R.-G., J.L., M.Á.G., A.G.-V., A.P., L.V. and M.M.-S.; Supervision, M.M.-S.; Writing—original draft, M.I.B.; Writing—review & editing, M.I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Comunidad de Madrid (protocol code18/07, approval date 11 January 2008).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data available under request from SEICAV.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lin C.J., Chua S., Chung S.Y., Hang C.L., Tsai T.H. Diabetes mellitus: An independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality in patients with infective endocarditis in a new era of clinical practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:2248. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olmos C., Vilacosta I., Fernández-Pérez C., Bernal J.L., Ferrera C., García-Arribas D., Pérez-García C., San Román J.A., Maroto L., Macaya C., et al. The evolving nature of infective endocarditis in Spain. A population-based study (2003 to 2014) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:2795–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Miguel-Yanes J.M., Jiménez-García R., Hernández-Barrera V., de Miguel-Díez J., Méndez-Bailón M., Muñoz-Rivas N., Pérez-Farinós N., López-de-Andrés A. Infective endocarditis according to type 2 diabetes mellitus status: An observational study in Spain, 2001–2015. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019;18:161–174. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0968-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benvenga R.M., De Rosa R., Silverio A., Matturro R., Zambrano C., Masullo A., Mastrogiovanni G., Soriente L., Ascoli R., Citro R., et al. Infective endocarditis and diabetes mellitus: Results from a single-center study from 1994 to 2017. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0223710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe T., Eyituoyo H.O., De Allie G., Olanipekun T., Effoe V.S., Olaosebikan K., Mather P. Clinical outcomes in patients with native valve infective endocarditis and diabetes mellitus. World J. Cardiol. 2021;13:11–20. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v13.i1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frydrych L.M., Bian G., O’Lone D.E., Ward P.A., Delano M.J. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus drive immune dysfunction, infection development, and sepsis mortality. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018;104:525–534. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5VMR0118-021RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costantini E., Carlin M., Porta M., Brizzi M.F. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and sepsis: State of the art, certainties and missing evidence. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58:1139–1151. doi: 10.1007/s00592-021-01728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trevelin S.C., Carlos D., Beretta M., da Silva J.S., Cunha F.Q. Diabetes mellitus and sepsis: A challenging association. Shock. 2017;47:276–287. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armiñanzas C., Fariñas-Alvarez C., Zarauza J., Muñoz P., González Ramallo V., Martínez-Sellés M., Miró J.M., Pericás J.M., Goenaga M.A., Ojeda G. Role of age and comorbidities in mortality of patients with infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019;64:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Sellés M., Munoz P., Arnáiz A., Moreno M., Gálvez J., Rodriguez-Roda J., de Alarcón A., García E., Fariñas M., Miró J.M., et al. Valve surgery in active infective endocarditis: A simple score to predict in-hospital prognosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;175:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mateos R., Boix-Palop L., Muñoz P., Mestres C.A., Marín M., Pedraz A., de Alarcón A., Gutiérrez E., Hernández M., Goenaga M.A. Infective endocarditis in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: A nationwide study. Europace. 2020;22:1062–1070. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J.S., Sexton D.J., Mick N., Nettles R., Fowler V.G., Ryan T., Bashore T., Corey G.R. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000;30:633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habib G., Lancellotti P., Antunes M.J., Bongiorni M.G., Casalta J.P., Del Zotti F., Dulgheru R., El Khoury G., Erba P.A., Iung B. ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) Eur. Heart J. 2015;36:3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain J.J., Rhinehart A.S., Shaefer C.F., Jr., Neuman A. Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes: Synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016;164:542–552. doi: 10.7326/M15-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Draznin B., Aroda V.R., Bakris G., Benson G., Brown F.M., Freeman R., Green J., Huang E., et al. Retinopathy, neuropathy, and foot care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45((Suppl. 1)):S185–S194. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovic D., Piperidou A., Zografou I., Grassos H., Pittaras A., Manolis A. The growing epidemic of diabetes mellitus. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020;18:104–109. doi: 10.2174/1570161117666190405165911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministerio de Sanidad Consumo y Bienestar Social. Encuestas Nacionales de Salud La Diabetes en España y en el Mundo, en datos y Gráficos (epdata.es) [(accessed on 5 March 2022)]. Available online: https://www.epdata.es/datos/diabetes-espana-datos-graficos/472.

- 18.Sy R.W., Kritharides L. Health care exposure and age in infective endocarditis: Results of a contemporary population-based profile of 1536 patients in Australia. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:1890–1897. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olmos C., Vilacosta I., Pozo E., Fernández C., Sarriá C., López J., Ferrera C., Maroto L., González I., Vivas D. Prognostic implications of diabetes in patients with left-sided endocarditis: Findings from a large cohort study. Medicine. 2014;93:114–119. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leone S., Ravasio V., Durante-Mangoni E., Crapis M., Carosi G., Scotton P.G., Barzaghi N., Falcone M., Chinello P., Pasticci M.B. Epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome of infective endocarditis in Italy: The Italian Study on Endocarditis. Infection. 2012;40:527–535. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedeli U., Schievano E., Buonfrate D., Pellizzer G., Spolaore P. Increasing incidence and mortality of infective endocarditis: A population-based study through a record-linkage system. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duval X., Alla F., Doco-Lecompte T., Le Moing V., Delahaye F., Mainardi J.L., Plesiat P., Célard M., Hoen B., Leport C. Association pour l’Etude et la Prévention de l’Endocardite Infectieuse (AEPEI). Diabetes mellitus and infective endocarditis: The insulin factor in patient morbidity and mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2007;28:59–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunes M.C.P., Guimarães-Júnior M.H., Murta Pinto P.H.O., Coelho R.M.P., Souza Barros T.L., Faleiro Maia N.P.A., Madureira D.A., Padilha Reis R.C., Costa P.H.N., Bráulio R. Outcomes of infective endocarditis in the current era: Early predictors of a poor prognosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;68:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joffre J., Dumas G., Aegerter P., Dubée V., Bigé N., Preda G., Baudel J.L., Maury E., Guidet B., Ait-Oufella H. CUB-Réa Network. Epidemiology of infective endocarditis in French intensive care units over the 1997–2014 period-from CUB-Réa Network. Crit. Care. 2019;23:143. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei X.B., Liu Y.H., Huang J.L., Chen X.L., Yu D.Q., Tan N., Chen J.Y., He P.C. Prediabetes and diabetes are both risk factors for adverse outcomes in infective endocarditis. Diabet. Med. 2018;35:1499–1507. doi: 10.1111/dme.13761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno R., Zamorano J., Almería C., Villate A., Rodrigo J.L., Herrera D., Alvarez L., Morán J., Aubele A., Mataix L. Influence of diabetes mellitus on short- and long-term outcome in patients with active infective endocarditis. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2002;11:651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Østergaard L., Mogensen U.M., Bundgaard J.S., Dahl A., Wang A., Torp-Pedersen C., Gislason G., Køber L., Køber N., Dejgaard T.F. Duration and complications of diabetes mellitus and the associated risk of infective endocarditis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;278:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tousoulis D., Kampoli A.M., Stefanadis C. Diabetes mellitus and vascular endothelial dysfunction: Current perspectives. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2012;10:19–32. doi: 10.2174/157016112798829797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eringa E.C., Serne E.H., Meijer R.I., Schalkwijk C.G., Houben A.J., Stehouwer C.D., Smulders Y.M., van Hinsbergh V.W. Endothelial dysfunction in (pre)diabetes: Characteristics, causative mechanisms and pathogenic role in type 2 diabetes. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2013;14:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delamaire M., Maugendre D., Moreno M., Le Gof M.C., Allannic H., Genetet B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet. Med. 1997;14:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199701)14:1<29::AID-DIA300>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chirillo F., Bacchion F., Pedrocco A., Scotton P., De Leo A., Rocco F., Valfrè C., Olivari Z. Infective endocarditis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:312–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alba-Loureiro T.C., Munhoz C.D., Martins J.O., Cerchiaro G.A., Scavone C., Curi R., Sannomiya P. Neutrophils function and metabolism in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Braz. J. Med. Res. 2007;40:1037–1044. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006005000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonidou L., Mouzaki A., Michalaki M., DeLastic A.L., Kyriazopoulou V., Bassaris H.P., Gogos C.A. Cytokine production and hospital mortality in patients with sepsis-induced stress hyperglycemia. J. Infect. 2007;55:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.05.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad R., Haque M. Oral health messiers: Diabetes mellitus relevance. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021;14:3001–3015. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S318972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available under request from SEICAV.