Abstract

Although the practice of composting animal wastes for use as biofertilizers has increased in recent years, little is known about the microorganisms responsible for the nitrogen transformations which occur in compost and during the composting process. Ammonia is the principle available nitrogenous compound in composting material, and the conversion of this compound to nitrite in the environment by chemolithotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria is an essential step in nitrogen cycling. Therefore, the distribution of ammonia-oxidizing members of the β subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in a variety of composting materials was assessed by amplifying 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and 16S rRNA by PCR and reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), respectively. The PCR and RT-PCR products were separated by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and were identified by hybridization with a hierarchical set of oligonucleotide probes designed to detect ammonia oxidizer-like sequence clusters in the genera Nitrosospira and Nitrosomonas. Ammonia oxidizer-like 16S rDNA was detected in almost all of the materials tested, including industrial and experimental composts, manure, and commercial biofertilizers. A comparison of the DGGE and hybridization results after specific PCR and RT-PCR suggested that not all of the different ammonia oxidizer groups detected in compost are equally active. amoA, the gene encoding the active-site-containing subunit of ammonia monooxygenase, was also targeted by PCR, and template concentrations were estimated by competitive PCR. Detection of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in the composts tested suggested that such materials may not be biologically inert with respect to nitrification and that the fate of nitrogen during composting and compost storage may be affected by the presence of these organisms.

Nitrogen is one of the most important elements in plant nutrition, and the high crop yields obtained by modern agriculture have been greatly facilitated by the application of nitrogen-rich fertilizers. Traditionally, chemical fertilizers have been the major source of nitrogen amendment in agricultural systems, but recently the use of biofertilizers, derived from animal excretia, has become increasingly important. Manure production has increased considerably during recent years, and in some countries animal production is limited by the manure disposal regulations (6, 18). As manure contains a large proportion of the nutrients ingested by an animal, it has the potential to be a valuable source of nutrients for plants when it is recycled and used as a biofertilizer. Although manure may be treated as waste in regions where the levels of animal production are high, it can also be regarded as a valuable resource and used either directly or after processing. In addition to providing nutrients for agricultural crops and helping alleviate the problem of excess animal waste, biofertilizers can also improve soil fertility and suppress pathogenic microflora, and the effects can last for up to several seasons (2, 53).

Composting is one of the oldest and simplest methods of organic waste stabilization (34). The major goal of composting is to provide a stable product that is high in nutrients which are easily accessible by plants. Due to the rapid hydrolysis of urea and the deamination of unincorporated peptides, ammonia (or ammonium in its undissociated form) is the most important nitrogenous compound available in composting materials (18). This form of nitrogen is often not taken up by plants very readily and can act as a substrate for nitrification. Nitrification in the environment can lead to pollution of groundwater due leaching of nitrate (3) or can be coupled with denitrification, which results in a loss of nitrogen from the system or the production the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide via incomplete denitrification (32). Moreover, when nitrogen is applied in the form of ammonia, there is potential loss due to ammonia volatilization, which may give rise to eutrophication or acidification of both surface water and groundwater (9, 17, 27, 48). Strict controls on the amounts of nutrients that are spread on agricultural land require an ability to track deposited nitrogen, which makes stabilization of animal manure products through composting an essential step in the use of these products as biofertilizers.

Although workers have examined nitrogen balance during composting (22, 30), this parameter has not been described well yet. Inbar et al. (18) qualitatively characterized nitrification as a normal process in compost that depends on the composting conditions used. Nodar et al. (28) reported the presence of “very few ammonium oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers” belonging to undetermined genera in a poultry dung-pine sawdust mixture, and the number of nitrifiers decreased after prolonged storage of poultry slurry (29). Thus, although nitrifiers have been recognized as potentially important organisms in composts and composting materials, their species composition, distribution, and activity have not been assessed yet.

The lack of data concerning ammonia oxidizers in compost may be due to the difficulties encountered in studying this specialized group of organisms by conventional culture-based techniques. Ammonia oxidizers have low maximum growth rates and produce low biomass yields, and pure-culture isolation is extremely time-consuming and unrepresentative (36).

The ammonia-oxidizing bacteria comprise the following two monophyletic lineages within the class Proteobacteria, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences: the genus Nitrosococcus in the γ subgroup and the genera Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira (containing the former genera Nitrosovibrio and Nitrosolobus) in the β subgroup (15, 47, 54, 55). Whereas it is thought that the genus Nitrosococcus is restricted to marine habitats (52), the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers appear to occur in a broad range of environments (4). The monophyletic nature of the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers has facilitated the design of PCR primers and oligonucleotide probes that target the 16S rRNA gene in this group at different taxonomic levels, and the use of these primers and probes has led to recent progress in the analysis of ammonia oxidizer populations (16, 24, 43, 50).

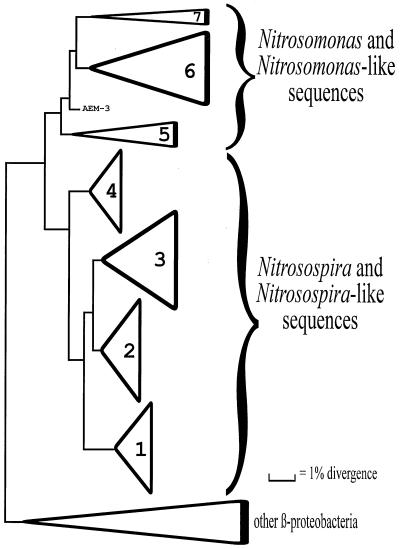

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) is a powerful tool for analyzing microbial communities. It has been used to separate mixed PCR products after amplification of 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) fragments (25), and this technique has been adapted to the study of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (19). DGGE band patterns can be characterized by hybridization with specific oligonucleotides that target internal sites, as demonstrated for broad taxonomic groups within the domain Bacteria (46) and the seven recognized sequence clusters within the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers (Fig. 1) (42, 43). The structural gene for the active subunit of ammonia monooxygenase, amoA, has also recently been the target of PCR-based studies (17), and competitive PCR can be used to estimate the concentration of a target sequence in a given sample (44).

FIG. 1.

Schematic phylogenetic tree for the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers. The construction of the tree was based on a distance matrix and neighbor-joining analysis, as described by Stephen et al. (42). The height of each triangle represents the number of sequences in the sequence cluster used for tree construction, and the length of each triangle is proportional to the sequence diversity within the cluster. The cluster designations, as proposed by Stephen et al. (42), are indicated inside the triangles. AEM-3 is a sequence that was recovered from marine sediment and does not fall into any of the sequence clusters described (23). The group labeled “other β-proteobacteria” was included as an outgroup and represents only a small sample of the available β-subgroup proteobacterial 16S rDNA sequences.

Our goal was to study the distribution and community composition of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers in different types of compost and composting materials in order to determine to what extent these organisms might be responsible for nitrogen transformations in these substrates. The method that was most suitable for community analysis of multiple samples was separation of specifically amplified 16S rDNA fragments by DGGE, followed by membrane transfer and hybridization with specific oligonucleotide probes (43). 16S rRNA was simultaneously targeted by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to determine which of the ammonia oxidizer populations detected were most active in the composting materials tested (11, 35, 51). PCR amplification of the amoA gene helped confirm that ammonia-oxidizing bacteria were present, and competitive PCR was used to estimate the number of target molecules present per gram of material in the various samples. A most-probable-number (MPN) analysis was also performed with some samples in order to compare culture-dependent detection and molecular detection of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in manure and compost.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling procedures.

The chemical compositions of the samples used are shown in Table 1. The samples were obtained between October 1996 and January 1997 at the locations described below, and they were transported at 4°C and kept at this temperature until they were used. The samples were processed within 1 week of collection. All of the samples except the activated sludge sample were homogenized prior to DNA isolation with a model PT laboratory sample divider (Retsch, Haan, Germany) adapted with a 3-mm-grid sieve. The activated sludge sample was thoroughly mixed prior to DNA isolation.

TABLE 1.

Physical characteristics of the samples testeda

| Sample | pH | Amt (g/kg) of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter | Ash | Nkj | NH4+ | P (total) | K+ | ||

| Compost used for mushroom cultivation | |||||||

| t=0 | 7.7 | 252 | 48.2 | 4.69 | 1.35 | 0.78 | 4.35 |

| t=4 | 7.3 | 176 | 42.8 | 3.29 | 1.12 | 0.68 | 3.36 |

| t=6 | 7.3 | 258 | 65.1 | 4.72 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 5.95 |

| 6d+ | 7.2 | 228 | 52.9 | 4.07 | 1.33 | 1.03 | 5.65 |

| end | 7.1 | 286 | 94.4 | 6.19 | 0.07 | 1.55 | 4.30 |

| Experimental pig and chicken composts | |||||||

| top | 7.2 | 188 | 60.8 | 4.93 | 0 | 5.08 | 2.47 |

| bot | 8.4 | 218 | 54.9 | 7.56 | 3.26 | 4.72 | 4.58 |

| aer | 8.0 | 294 | 148 | 8.94 | 1.57 | 11.1 | 1.64 |

| Chicken and pig manures | |||||||

| pig man | 8.0 | NDb | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| chi man | 7.6 | 340 | 112 | 16.8 | 3.34 | 4.52 | 7.75 |

| chi bed | 8.4 | 650 | 166 | 17.4 | 2.07 | 6.73 | 13.4 |

| chi fre | 8.0 | 295 | 94.4 | 17.0 | 2.76 | 4.72 | 6.65 |

| Dry biofertilizers | |||||||

| BAM | 6.2 | 888 | 164 | 49.9 | 3.46 | 22.0 | 3.05 |

| ECU | 9.1 | 902 | 510 | 13.8 | 4.37 | 32.6 | 9.26 |

| BIO | 7.5 | 925 | 228 | 33.0 | 5.47 | 11.5 | 16.6 |

| AcS | 7.7 | 30.4 | 17.1 | 1.23 | 0.12 | 1.14 | 3.58 |

Using qualitative experiments to determine the presence of nitrate and nitrite (39), we did not detect either of these compounds (>0.1 mM NO3− plus NO2−) in any of the samples.

ND, not determined.

Industrial compost used for mushroom cultivation.

Samples were obtained from an industrial composting plant designed to produce substrate for cultivation of the edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus (Lange) Imbach. At this plant the process is fully automated and has a throughput of approximately 10,000 metric tons of compost per week. Straw-rich horse manure, livestock manure slurries, and wheat straw are the raw materials, and gypsum and water are added to the composting mixture during the initial stages of the process. The composting process takes approximately 2 weeks. During the first week the temperature is kept within the range from 65 to 75°C, after which a 1% inoculum consisting of the end product is added to the mixture, and the compost is allowed to mature for an additional 1 week at the ambient temperature. Samples were obtained from five different stages of the process, as follows: at the beginning of the composting process (t=0 sample), after 4 days of composting (t=4 sample), after 6 days of composting (t=6 sample), after the end product was added to the 6-day-old compost (6d+ sample), and at the end of the 2-week process (end sample).

Experimental pig manure and chicken manure composts.

Pig and chicken manure composts were obtained from the Wageningen Agricultural University Department of Environmental Technology (Wageningen, The Netherlands) and the All-Russia Institute of Agriculture (Moscow, Russia). The starting material for the compost obtained from the Wageningen Agricultural University was pig manure mixed with straw. This mixture was allowed to mature and stabilize for 6 months in small, dense composting piles, and the temperature was not monitored. Samples were taken simultaneously after 6 months of composting from both the top (top sample) and bottom (bot sample) of a composting pile.

The Moscow sample (aer sample) was obtained from an experimental compost production plant in which chicken manure slurry and peat were used. The chicken manure slurry was premixed with peat, and the moisture content was adjusted to 70%. The aerobic composting process took place in specially fitted 10-m3 containers which had floor slots that allowed air to be supplied to the composting mixture. The compost was aerated six times each day by forcing air through the floor slots for 5 min. The composting process was conducted at 65 to 75°C, and the total treatment time was 7 days. The compost was stored for 5 months prior to sampling.

Chicken manure and pig manure samples.

The pig manure sample (pig man sample) was obtained from the solid fraction below the stall slats at a pig farm in Wageningen, The Netherlands. The manure was mixed with straw and then stored for 1 week prior to sampling.

The material from which the chicken bedding sample (chi bed sample) was obtained had been in place for 3 weeks before sample was obtained. The chicken dropping sample (chi man sample) was collected 2 weeks after the previous waste collection, and the fresh chicken manure sample (chi fre sample) was collected just after deposition by laying hens and therefore had minimal contact with the outside environment prior to collection. These three samples were obtained from a commercial farm in Heesch, The Netherlands, which was used for chicken egg production.

Dry bioorganic fertilizers.

Commercial dry bioorganic fertilizer samples were obtained from St. Petersburg, Russia; these samples were products of treatment of agricultural animal excretia. Bamil (BAM) is a fertilizer derived from activated sludge and primary settler sediments obtained from purification plants used to process pig farm slurry. The activated sludge and sediment are mixed at a 1:1 ratio and dried at 70 to 80°C for approximately 1 h in order to obtain a moisture content of 10%. ECUD (ECU) is a product derived from anaerobic fermentation of chicken slurry. Chicken manure (moisture content, 75%) is diluted with water to a moisture content of 85% and loaded into anaerobic tanks, where manure fermentation takes place at 40°C continuously for 7 to 8 days. The solid fraction obtained is subsequently dried at 70 to 80°C to reduce its moisture content to 10%. BIOGUM (BIO) is obtained in a similar fashion but after aerobic treatment of chicken slurry.

Activated sludge.

As chemolithotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are known to occur in high numbers in aerobic activated sludge, a calf slurry-fed activated sludge sample (AcS sample) was used as a positive control in this study (50). The AcS sample, which consisted of two 1-liter samples that were subsequently pooled, was obtained from the manure treatment plant of the Gelderland Organization for Manure Treatment in Ede, The Netherlands.

Enumeration of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and characterization of highest positive MPN dilutions.

Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria were enumerated by using the MPN method of Verhagen and Laanbroek (49), as modified by Bodelier et al. (5). The medium used was the medium described by Schmidt and Belser (39), and positive cultures and cell counts were determined by the methods described by Verhagen and Laanbroek (49). One-half of the dilutions were examined after 8 weeks of incubation at 28°C, and the other half were examined after 20 weeks of incubation. MPN analyses were performed with only six samples (Table 2). Nitrification activity was determined by the presence of nitrate and/or nitrite (>0.1 mM NO3− plus NO2−), as detected with a model Traacs 800 autoanalyzer (Technicon Instruments Corp., Tarrytown, N.Y.). Culture medium (1 μl) from each highest positive dilution was used directly as a template for ammonia oxidizer-specific PCRs. For the analysis of recovered 16S rDNA, we used the PCR, DGGE, and hybridization conditions described below for compost samples.

TABLE 2.

Detection of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers in compost by PCR, RT-PCR, MPN, and oligonucleotide hybridization

| Sample | β-Subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers as determined by:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct PCR | Nested PCR | RT-PCR | amoA PCR (no. of cells/g)a | MPN method (no. of cells/g) | Hybridizationb | |

| Compost used for mushroom cultivation | ||||||

| t=0 | +c | + | + | 2.3 × 105 ± 0.9 × 105 | 7.0 × 102 ± 3.5 × 102, 8.3 × 103 ± 2.4 × 103d | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4 |

| t=4 | − | + | − | − | NDe | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4 |

| t=6 | − | + | − | − | − | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| 6d+ | − | + | − | 2.4 × 103 ± 1.8 × 103 | ND | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| end | + | + | − | 2.7 × 104 ± 1.6 × 104 | <100, 1.2 × 102 ± 0.2 × 102d | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4 |

| Experimental pig and chicken composts | ||||||

| top | + | + | + | 4.5 × 105 ± 0.8 × 105 | ND | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4, Nitrosomonas cluster 6af |

| bot | − | − | − | − | ND | |

| aer | + | + | + | 2.3 × 105 ± 0.9 × 105 | ND | Nitrosospira cluster 3, Nitrosomonas cluster 6a |

| Chicken and pig manures | ||||||

| pig man | + | + | − | 4.1 × 104 ± 1.0 × 104 | ND | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4 |

| chi man | − | + | − | − | − | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| chi bed | − | + | − | 3.3 × 103 ± 1.9 × 103 | − | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| chi fre | − | + | − | − | ND | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| Dry biofertilizers | ||||||

| BAM | − | + | − | 2.8 × 103 ± 0.8 × 103 | ND | Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4 |

| ECU | − | + | − | − | ND | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| BIO | − | + | − | 1.4 × 103 ± 0.6 × 103 | ND | Nitrosospira cluster 3 |

| AcS | + | + | + | 1.7 × 1012 ± 1.1 × 1012 | 8.8 × 1011 ± 3.2 × 1011, 9.0 × 1011 ± 3.3 × 1011d | Nitrosospira cluster 3, Nitrosomonas clusters 6 and 7f |

The values are based on the results of three separate competitive PCRs.

+, positive reaction; −, no product was recovered or no growth occurred.

The first value is the value obtained after 8 weeks of incubation, and the second value is the value obtained after 20 weeks of incubation. A value of <100 indicates that some cultures were positive but there were too few positive cultures to calculate an MPN value.

ND, not determined.

The cluster bands were detected only by DNA analysis and not by the RT-PCR analysis. The PCR assays targeted 16S rDNA or 16S rRNA unless indicated otherwise.

Nucleic acid extraction, PCR, RT-PCR, and competitive PCR.

DNAs were extracted from all of the samples by using the method described by Stephen et al. (42), as modified by Kowalchuk et al. (19). Direct specific amplification of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer 16S rDNA was performed by using primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r and the conditions described by Kowalchuk et al. (19). The PCR products were separated by standard agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose, 0.5× TBE [1× TBE is 0.04 M Tris base plus 0.02 M acetic acid plus 1.0 mM EDTA, pH 7.5]) and were visualized by the ethidium bromide fluorescence method. For the nested PCR we first performed a eubacterium-specific PCR with primers pA and pH (8) and then performed a second PCR with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r. The first PCR was performed by using approximately 50 ng of template DNA and Tbr polymerase (Dynazyme; Finnzymes, Iploo, Finland) as recommended by the manufacturer, and the following thermocycling program was used: one cycle consisting of 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 60 s at 55°C, and 75 s at 72°C (with the time increasing 1 s/cycle); and one cycle consisting of 5 min at 72°C. The reaction volume was of 25 μl. The PCR products (25 μl each) were examined by electrophoresis in a 0.5× TBE–1% low-melting-point agarose gel (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), followed by ethidium bromide staining. For all of the samples, the product of the expected size (1.5 kb) was excised from the gel (100 mg of gel material). The gel fragment was melted by heating it for 5 min at 65°C, and 1 μl of the resulting preparation was used as the template in the second PCR performed with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r as described above.

rRNA preparations were obtained by using the ribosome isolation technique of Felske et al. (11). Reverse transcription was performed with rTth DNA polymerase and a Reverse Transcriptase buffer kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Foster City, Calif.) by using 30 pmol of primer CTO654r and the reaction conditions described by Felske et al. (11). Then a PCR was performed as described above after the reaction mixture and primer CTO189f-GC were added. For general eubacterial RT-PCRs, which were conducted to determine levels of RNA recovery and purity, we used primers F968 and R1401 as described previously (10, 11).

amoA gene fragments were amplified by using the primers of Rotthauwe et al. (37), as modified by Stephen et al. (44), and the DNA preparations that were used for the 16S rDNA analysis. For competitive PCR we used the amoA deletion construct p428-NAB_8_23 and the size difference conversion factor (1.11) described by Stephen et al. (44). PCR signals were quantified from digitized gel images (The Imager System; Ampligene, Illkirch, France) by using the ImageMaster Elite software package (Pharmacia).

To assess the sensitivities of the various PCR assays, sterilized sand and sterilized bot compost samples were inoculated with known numbers of log-phase Nitrosomonas europaea cells (doubling time, 8.5 h) 15 min before DNA was isolated. The preparations were sterilized with 50 kGy of UV irradiation (Gammaster B.V., Ede, The Netherlands). When the reaction conditions described above were used, no eubacterial PCR signal was detected after sterilization.

DGGE, blotting, and hybridization analysis.

The PCR products examined by DGGE included the products obtained after specific nested PCR and RT-PCR, as described above. The fragment used spanned 465 bp of the 16S rRNA gene and included a 36-bp GC clamp (41) introduced during the PCR. DGGE was performed with a D-Gene system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) by using the protocol of Muyzer et al. (26) as adapted for analysis of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers (19). DNA fragments with known ammonia oxidizer sequence cluster affinities (Fig. 1) (42) were also electrophoresed on DGGE gels (38 to 50% denaturant) as controls for subsequent hybridization analyses (data not shown). The DNA was stained with ethidium bromide and rinsed twice in deionized water prior to UV transillumination.

DNA was transferred from the polyacrylamide gels to Hybond-N+ nucleic acid transfer membranes (Amersham International, Bucks, United Kingdom) by using a Bio-Rad model SD semidry transblotter as described by Muyzer et al. (26). The DNA was subsequently denatured (DNA side down) and simultaneously cross-linked to a membrane by soaking it in 0.4 M NaOH–0.6 M NaCl on 3MM filter paper (Whatman, Kent, United Kingdom). The membranes were similarly neutralized with 1 M NaCl–0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8). Hybridization analyses were conducted by using the oligonucleotide probes and hybridization conditions described by Stephen et al. (43) (Fig. 1 shows the sequence clusters). No attempts were made to quantify the intensities of the hybridization signals obtained.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Recovery of ammonia oxidizer DNA by PCR and RT-PCR.

The PCR and RT-PCR results obtained for the 15 compost and manure samples and one activated sludge sample tested are summarized in Table 2. Direct amplification with the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer-specific primers yielded PCR product for only six of the compost or manure samples. Although some samples contained significant amounts of humic substances, PCR inhibition was not observed, and all samples yielded products of the expected size with the eubacterium-specific primers pA and pH (8; results not shown). Addition of 5 × 103 N. europaea cells g−1 to sterilized sand and addition of 104 cells g−1 to the sterilized bot compost sample resulted in positive PCR signals. The latter level of inoculation was sufficient to produce positive PCR signals in samples which were originally negative.

The eubacterial 16S rDNA PCR product was used as the template in a nested PCR analysis performed with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r, which yielded positive results for all of the samples except the bot sample, which was obtained from the anoxic bottom of the pig manure composting pile. It should be noted that nested PCR resulted in only very weak signals for the t=4, t=6, 6d+, chi man, and chi fre samples, and three separate PCR mixtures had to be pooled in these cases to provide enough material for DGGE analysis (see below). The minimum numbers of N. europaea cells required to produce positive results in this nested PCR analysis were 5 × 102 cells g−1 for sterilized sand and 103 cells g−1 for the sterilized bot sample.

rRNA was extracted from all of the samples analyzed, as confirmed by RT-PCR performed with F968 and R1401, although the signals obtained with the three dry biofertilizers were much weaker than all of the other signals (results not shown). RT-PCRs performed with only primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r yielded detectable products with the t=0, top, aer, and AcS samples (Table 2). Unfortunately, the fragment produced by amplification with primers F968 and R1401 did not contain the region spanned by primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r and could not be used as a template in a nested PCR analysis. RT-PCRs performed with primers pA and pH also yielded unsatisfactory results, perhaps due to the length of the fragment, so that no nested RT-PCR analysis could be carried out. The minimum numbers of log-phase N. europaea cells required to produce positive RT-PCR signals with the sterilized sand and bot samples were 103 and 3 × 103 cells g of soil−1, respectively. Addition of 3 × 103 log-phase N. europaea cells g of soil−1 to samples which were negative for the RT-PCR performed with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r yielded detectable RT-PCR signals.

Table 2 also shows the results obtained when the PCR targeted the amoA gene, and competitive PCR performed with a deletion construct, p428-NAB_8_23 (44), allowed us to estimate the target concentrations in the samples analyzed. The minimum numbers of linear amoA deletion fragments per reaction mixture which resulted in positive PCR signals were 10 when the fragments were added to water or DNA extracted from sterilized sand and 20 when the fragments were added to DNA extracted from the sterilized bot sample; 5 × 102 and 103 N. europaea cells g of soil−1 were the minimum numbers of cells which resulted in positive amoA PCR results for the sterilized sand and bot samples, respectively. It is not yet known how efficiently the amoA primers recognize all of the lineages within the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer clade (37). Incomplete coverage of all of the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer targets by the amoA primers might explain why this assay had an intermediate level of sensitivity compared to the direct and nested 16S rDNA PCR assays (Table 2) despite the fact that it was as sensitive as the nested 16 rDNA PCR assay when controls were used.

DGGE and hybridization analysis.

For consistency, DGGE analyses were performed with products obtained with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r after the nested PCR analysis. Directly amplified products were compared with the products obtained by nested PCR when possible, and the DGGE band patterns were similar; there were only minor differences in the intensities of some bands (data not shown). In the four cases in which RT-PCR products were obtained with primers CTO189f-GC and CTO654r, the fragments that were recovered were also subjected to DGGE in order to compare the results with results obtained when 16S rDNA was targeted.

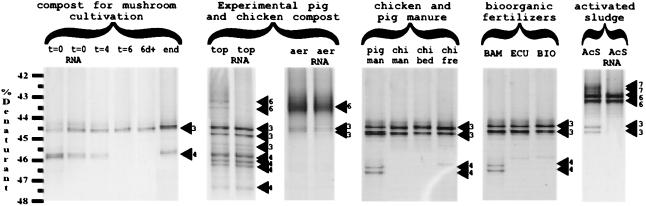

DGGE produced bands with 43 to 47% denaturant (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the results of previous DGGE analyses of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers (19, 44). Double band patterns were obtained in many cases, as reported previously, due to an ambiguous position in primer CTO654r (19). After membrane transfer and a hybridization analysis, performed with the hierarchical set of probes used for the β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizers (44), all of the visible bands could be identified to the sequence cluster level. Four of the seven sequence clusters proposed by Stephen et al. (42) (Fig. 1) were detected, although the four clusters were never detected in one sample. These sequence clusters were Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4, which have previously been detected in soil environments, and Nitrosomonas clusters 6 and 7, which have been observed in various environments (23, 42, 50).

FIG. 2.

DGGE separation of PCR and RT-PCR products from compost and manure. The numbers next to the arrowheads are sequence cluster designations, as determined by hybridization analysis (Fig. 1) (43). The hybridization results for the target sequences obtained from all of the samples are given in Table 2 and are discussed in the text.

The compost used for mushroom cultivation appeared to contain Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4, although the latter cluster was not detected in the t=6 and 6d+ samples. RT-PCR products obtained from the t=0 sample contained rRNAs from members of both of these groups. The fact that the nested PCR results were positive for the t=4 and t=6 samples suggests that some of the ammonia oxidizers present in the starting material were able to remain intact at temperatures up to 75°C. There are no known examples of thermophilic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, and cell activity is probably impaired or destroyed by high temperatures (12). Cell survival at high temperatures may be facilitated, however, by the formation of microniches (7), and the moisture content may also be an important factor in cell survival (13). The cell numbers and activity, if present, were probably quite low as all of the other PCR assays were negative when these samples were examined. Ammonia oxidation may still occur by other processes, such as heterotrophic nitrification by thermophilic methanotrophs (31, 33), during composting at high temperatures, although appreciable ammonia consumption was not observed. Nitrosospira cluster 4 was not detected in the t=6 and 6d+ samples and may be more susceptible to high temperatures than Nitrosospira cluster 3 is. The fact that Nitrosospira cluster 4 was detected in the final product both by PCR and by the MPN method (Table 3) suggests that ammonia oxidizer cell growth occurred during the second week of composting at the ambient temperature, the time of greatest ammonia consumption (Table 1). Whether this growth resulted from cells that survived the high-temperature composting stage or from cells that were introduced when the final product (1%) was added is not clear. Despite the presumed growth and activity, RT-PCR failed to detect a product in the end sample. This result was surprising given the positive results obtained for this sample when the direct PCR assay was used (Table 2). The dynamics of ammonia oxidizer populations during the composting process were reproducible. Samples obtained from the same stages from other batches of compost at a later date produced the same results (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Ammonia oxidizer sequence clusters in enrichment culturesa

| Sample | Incubation time (weeks) | No. of culturesb

|

No. of cultures examined | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrosospira cluster 3 | Nitrosospira cluster 4 | Nitrosomonas cluster 6 | Nitrosomonas cluster 7 | |||

| t=0 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 16 |

| t=0 | 20 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| end | 4 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| end | 20 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| AcS | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 30 |

β-Subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer 16S rDNAs were analyzed as described in the text by using the highest positive dilutions of the enrichment cultures used for the MPN analysis.

Cultures were classified on the basis of ammonia oxidizer sequence clusters (43).

The availability of oxygen, facilitated by aeration, may be an important regulatory factor for ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in composts. The top sample, which was obtained from the well-aerated portion of the pig manure compost pile, was positive in all of the PCR assays conducted, and all of the available ammonia was consumed (Table 1). This sample contained Nitrosospira clusters 3 and 4, as well as Nitrosomonas cluster 6, although rRNA related to Nitrosomonas cluster 6 could not be detected, suggesting that this group was not very active in the sample (Fig. 2). The sample obtained from the bottom of the same compost pile (bot sample), where conditions were anoxic, was the only sample in which no β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer-like sequences were detected (Table 2). The aer sample contained Nitrosospira cluster 3 and Nitrosomonas cluster 6, and both groups produced detectable levels of 16S rRNA when RT-PCRs were performed. This sample was obtained after 5 months of compost storage, and it is not clear if the sequences detected came from descendants of cells that had survived the high-temperature phase, perhaps facilitated by microsites within the peat structure (56), or cells that had subsequently colonized the compost.

The chi fre sample had minimal contact with the outside environment prior to collection, and the presence of Nitrosospira cluster 3 cells in this material suggests that some cells may remain intact even after they pass through a hen’s digestive tract. Whether these cells were viable is not known, and the ammonia oxidizer activity was below the detection limit of the RT-PCR assay for all of the manure samples tested. The other PCR-based assays were also negative for the chicken manure samples (chi fre and chi man samples), suggesting that the numbers of ammonia oxidizers were probably low. The pig man sample also contained only Nitrosospira sequences, including both cluster 3 and cluster 4 Nitrosospira sequences.

Ammonia oxidizer-like 16S rDNA sequences from Nitrosospira cluster 3 and 4 organisms were detected in the BAM dry fertilizer, and only Nitrosospira cluster 3 was detected in the ECU and BIO samples. Both the direct 16S rRNA-targeted PCR and the RT-PCR were negative when BAM and ECU fertilizer samples were examined, whereas the amoA-directed PCR was positive. These dried fertilizer products were designed to retain their nutrient contents even after long periods of storage. Whether low levels of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, such as those detected here, might significantly influence nitrogen transformations in these fertilizers or fertilizer-treated soil is not known.

The AcS sample contained sequences related to Nitrosospira cluster 3, as well as Nitrosomonas clusters 6 and 7. RT-PCR revealed a predominance of Nitrosomonas cluster 6 rRNA, suggesting that this group is chiefly responsible for the autotrophic ammonia oxidizer activity in the sludge examined. rRNA from members of Nitrosomonas cluster 7, which contains perhaps the most culturable ammonia oxidizer species (36) (see below), was not detected. Only a very faint signal, which was detected only after hybridization, was observed for Nitrosospira cluster 3, suggesting that the relative activity of this group was also very low in this sample. The activity of ammonia oxidizers in the sludge product, which is used as an agricultural fertilizer, might also play a role in postprocessing nitrogen transformation and nitrogenous gas emission (32).

Cell enumeration by the MPN method.

The cell counts determined by the MPN analysis for autotrophic nitrifying bacteria are presented for the six samples tested in Table 2. The cell counts were below the detection limit for the t=6, chi man, and chi bed samples. Moderate numbers of ammonia-oxidizing cells were detected in the t=0 sample, and levels just above the limit of detection were detected in the end sample. The AcS sample contained extremely high numbers of culturable ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (>1011 cells/g of fresh material). Although high culturability for ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge was expected (1), the cell numbers were approximately 2 orders of magnitude higher than the cell numbers reported for a different animal waste-fed activated sludge, as determined by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining and in situ hybridization after disruption of aggregates by Ultraturrax blending (50). It may be that the shaking method used for the MPN analysis more successfully disrupts sludge flocs or causes fewer cells to be damaged than blending. Alternatively, the sludge examined may simply have contained a higher number of ammonia oxidizer cells.

16S rDNA characterization of the highest positive MPN dilutions.

A comparison of the ammonia oxidizer 16S rDNA sequences in MPN enrichment cultures (Table 3) with hybridization results obtained after nested PCR performed with directly extracted DNA (Fig. 2) revealed differences in the ammonia oxidizer sequences detected by the two methods. The culture-based method detected proportionately more ammonia oxidizers affiliated with Nitrosospira cluster 3 and Nitrosomonas cluster 7, the two sequence clusters best represented in pure-culture collections. The number of ammonia-oxidizing cells detected in the t=0 and end samples was greater when the longer incubation period was used, suggesting that some cells were either very slow growing or required an extensive period of adaptation to the growth medium. The fact that the proportion of Nitrosospira cluster 4 organisms relative to Nitrosospira cluster 3 organisms increased with a longer incubation time (Table 3) suggests that the members of the former group may require a longer period of time to become active in the culture medium. Although previous studies produced no evidence suggesting that there was preferential amplification of the groups most frequently detected by the direct PCR-based approaches used in this study (19), it is still not possible to conclude to what extent culture (36) or PCR (45) biases contributed to these differences.

Conclusions.

β-Subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer-like sequences were detected in almost all of the composting materials analyzed, although the sensitivities of the different PCR methods used varied. It is not known yet to what extent the ammonia-oxidizing bacteria detected might affect nitrogen transformations before, during, and after composting. However, the detection of nucleic acids from nitrifying bacteria in these materials may have important implications for both compost processing and storage, as well as for the use of compost in agriculture. The main goal of composting is to produce a stable, highly nutritious substrate. As ammonia oxidation is often the rate-limiting step during the loss of nitrogen from systems due to denitrification, conditions which are favorable for the activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in compost may affect the net nitrogen balance. The potential for nitrification has previously been considered in connection with the construction and installation of some compost production plants (21, 38). In contrast to application of mineral fertilizers, application of biofertilizers and manure inoculates the soil with allochthonic microflora, and results presented here suggest that composts and even dried bioorganic fertilizers may inoculate soils with nitrifying bacteria. Several studies have examined nitrification in soils after the soils have been amended with compost (14, 20, 32, 40), but they have done so mostly within the context of activation of the indigenous nitrifying community. The ability to identify and track the presence and activity of specific groups of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria should aid in our overall understanding of nitrogen balance problems in the production, storage, and use of a variety of composting materials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Netherlands/Russian joint initiative Development of Biotechnological Methods for Manure Treatment Focused on Fertilizer Production, which was financed by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). G.A.K. was supported by an NWO grant to the Netherlands Graduate School of Functional Ecology. J.R.S. was supported by grant GR3/8911 from the United Kingdom Natural Environment Research Council.

We thank Carol Phillips for help with the hybridization analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer B-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arkhipchenko I, Barbolina I. Proceedings of the International Conference of Biotechnology. 1994. Bamil—new biofertilizer and plant protective agent; pp. 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauhus J, Melwes K J. Nitrate leaching following organic refuse application in forests. Mitt Dtsch Boden Kundl Ges. 1991;66:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belser L W. Population ecology of nitrifying bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1979;33:309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.33.100179.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodelier P L E, Libochant J A, Blom C W P M, Laanbroek H J. Dynamics of nitrification and denitrification in root-oxygenated sediments and adaptation of ammonia-oxidising bacteria to low oxygen or anoxic habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4100–4107. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4100-4107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton C H, Martinez J. Animal manures and environment in Europe. Ingenieries special issue. Antony Cedex, France: Cemagref-Dicova; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derikx P J L, Op Den Camp H J M, Van der Drift C, Van Griensven L J L D, Vogels G D. Biomass and biological activity during the production of compost used as a substrate in mushroom cultivation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3029–3034. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.10.3029-3034.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards U, Rogall T, Blöcker H, Emde M, Böttger E C. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:7843–7853. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eghball B, Power J F. Beef cattle feedlot manure management. J Soil Water Conserv. 1994;49:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelen B, Heuer H, Felske A, Nübel U, Smalla K, Backhaus H. Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft. Germany: Braunschweig; 1995. Protocols for the TGGE; pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felske A, Engelen B, Nübel U, Backhaus H. Direct ribosome isolation from soil to extract bacterial rRNA for community analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4162–4167. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4162-4167.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Focht D D, Verstraete W. Biochemical ecology of nitrification and denitrification. In: Alexander M, editor. Advances in microbial ecology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1977. pp. 135–214. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gromov B V, Pavlenko G V. Bacterial ecology. Leningrad, USSR: Leningrad University Press; 1989. Autoecology of bacteria: water activity; pp. 78–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings R C, Ceccherini M T, Miclaus N, Saunders J R, Bazzicalupo M, McCarthy A J. Direct molecular biological analysis of ammonia oxidising bacteria populations in cultivated soil plots treated with swine manure. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Head I M, Hiorns W D, Embley T M, McCarthy A J, Saunders J R. The phylogeny of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria as determined by analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1147–1153. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiorns W D, Hastings R C, Head I M, McCarthy A J, Saunders J R, Pickup R W, Hall G H. Amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA genes of autotrophic ammonia-oxidising bacteria. Microbiology. 1995;141:2793–2800. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn H H V, Wilkie A C, Powers W J, Nordsted R A. Components of dairy manure management systems. J Dairy Sci. 1994;77:2008–2030. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inbar Y, Hadar Y, Chen Y. Recycling of cattle manure: the composting process and characterization of maturity. J Environ Qual. 1993;22:857–863. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalchuk G A, Stephen J R, De Boer W, Prosser J I, Embley T M, Woldendorp J W. Analysis of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the beta subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in coastal sand dunes by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S ribosomal DNA fragments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1489–1497. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1489-1497.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laanbroek H J, Gerards S. Effects of organic manure on nitrification in arable soils. Biol Fertil Soils. 1991;12:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahimairaja S, Bolan N S, Hedley M J. Absorption of ammonia released from poultry manure to soil and bark and the use of absorbed ammonia in solubilizing phosphate rock. Compost Sci Util. 1993;1:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahimairaja S, Bolan N S, Hedley M J, Macgregor A N. Losses and transformation of nitrogen during composting of poultry manure with different amendments: an incubation experiment. Bioresource Technol. 1994;47:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCaig A E, Embley T M, Prosser J I. Molecular analysis of enrichment cultures of marine ammonia oxidisers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;120:363–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mobarry B K, Wagner M, Urbain V, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Phylogenetic probes for analyzing abundance and spatial organization of nitrifying bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2156–2162. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2156-2162.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muyzer G, De Waal E C, Uitterlinden A G. Profiling complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muyzer G, Hottentrager S, Teske A, Wawer C. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA. A new molecular approach to analyze the genetic diversity of mixed microbial communities. In: Akkermans A D L, Van Elsas J D, De Bruijn F J, editors. Molecular microbial ecology manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1996. pp. 3.4.4.1–3.4.4.22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen V C, Voorburg J H, L’Hermite P, editors. Volatile emissions from livestock farming and sewage operations. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier Applied Science; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nodar R, Acea M J, Carballas T. Microbial population of poultry pine-sawdust litter. Biol Wastes. 1990;33:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nodar R, Acea M J, Carballas T. Poultry slurry microbial population: composition and evolution during storage. Bioresource Technol. 1992;40:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Dwyer B, Morgan M A, O’Toole P. Changes in physical and chemical properties of composts based on cattle slurry and milled peat during incubation. Acta Hortic (The Hague) 1989;238:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Neill J G, Wilkinson J F. Oxidation of ammonia by methane-oxidizing bacteria during thermophylic composting of sewage sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;49:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul J W, Beanchamp E G, Zhang X. Nitrous and nitric oxide emissions during nitrification and denitrification from manure-amended soil in the laboratory. Can J Soil Sci. 1993;73:539–553. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pel R, Oldenhuis R, Brand W, Vos A, Gottschal J C, Zwart K B. Stable-isotope analysis of a combined nitrification-denitrification sustained by thermophilic methanotrophs under low-oxygen conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:474–481. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.474-481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poincelot R P. The biochemistry and methodology of composting. Conn Agric Exp Stat Bull. 1975;754:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poulsen L K, Ballard G, Stahl D A. Use of rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization for measuring the activity of single cells in young and established biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1354-1360.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prosser J I. Autotrophic nitrification in bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1989;30:125–181. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotthauwe J-H, Witzel K-P, Liesack W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4704–4712. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4704-4712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saether T, Skjelhaugen O J, Lilleng H, Rognerud B. International Seminar of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Technical Section of CIGR on Environmental Challenges and Solutions in Agricultural Engineering. 1991. Biofilter as ammonia controller in an aerobic treatment plant for livestock slurry; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt E L, Belser L W. Autotrophic nitrifying bacteria. In: Weaver R W, Angle J S, Bottemley P S, editors. Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Microbiological and biochemical properties. Madison, Wis: Soil Science Society of America, Inc.; 1994. pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sempere A, Gomez I, Burlo F, Mataix J. Influence of potassium on nitrogen mineralization in two calcareous soils amended with earthworm humus. Agrochimica. 1995;39:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheffield V C, Cox D R, Myers R M. Attachment of a 40-base pair G+C-rich sequence (GC-clamp) to genomic DNA fragments by the polymerase chain reaction results in improved detection of single-base changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:232–236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephen J R, McCaig A E, Smith Z, Prosser J I, Embley T M. Molecular diversity of soil and marine 16S rRNA gene sequences related to beta-subgroup ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4147–4154. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4147-4154.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephen J R, Kowalchuk G A, Bruns M-A V, McCaig A E, Phillips C J, Embley T M, Prosser J I. Analysis of β-subgroup proteobacterial ammonia oxidizer populations in soil by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis and hierarchical phylogenetic probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2958–2965. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2958-2965.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephen J R, Chang Y-J, Macnaughton S J, Kowalchuk G A, Leung K T, Flemming C A, White D C. Effect of toxic metals on the indigenous β-subgroup ammonia oxidizer community structure and protection by inoculated metal-resistant bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:95–101. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.95-101.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki M T, Giovannoni S J. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:625–630. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.625-630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teske A, Wawer C, Muyzer G, Ramsing N B. Distribution of sulfate-reducing bacteria in a stratified fjord (Mariager Fjord, Denmark) as evaluated by most-probable-number counts and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified ribosomal DNA fragments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1405–1415. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1405-1415.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teske A, Elm E, Regan J M, Toze S, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Evolutionary relationships among ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6623–6630. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6623-6630.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Amstel A R, Swart R J. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions: an introduction. Fert Res. 1994;37:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verhagen F J M, Laanbroek H J. Competition for limiting amounts of ammonium between nitrifying and heterotrophic bacteria in dual energy-limited chemostats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3255–3263. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3255-3263.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner M, Rath Q, Amann R, Koops H-P, Schleifer K-H. In situ identification of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:251–264. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner R. The regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis and bacterial cell growth. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:100–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00276469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward B B, Carlucci A F. Marine ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria: serological diversity determined by immunofluorescence in culture and in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:194–201. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.194-201.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams G H, Guido G, Hermite P L, editors. Longterm effects of sewage sludge and farm slurries applications. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier Applied Science; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woese C R, Weisburg W G, Hahn C M, Paster B J, Zalben L B, Lewis B J, Macke T J, Ludwig W, Stackebrandt E. The phylogeny of the purple bacteria: the gamma subdivision. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1985;6:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woese C R, Weisburg W G, Paster B J, Hahn C M, Tanner R S, Kreig N R, Koops H-P, Harms H, Stackebrandt E. The phylogeny of the purple bacteria: the beta subdivision. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(84)80034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zvyagintsev D G, Dobrovol’skaya T G, Golovchenko A V, Zenova G M, Smagina M V. The structure of a saprotrophic microbial complex in the peatbogs. Microbiology. 1991;60:155–164. [Google Scholar]