Abstract

The aim was to evaluate hospitalization rates for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) within an interdisciplinary multicenter neurovascular network (NVN) during the shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic along with its modifiable risk factors. In this multicenter study, admission rates for SAH were compared for the period of the shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany (calendar weeks (cw) 12 to 16, 2020), the periods before (cw 6–11) and after the shutdown (cw 17–21 and 22–26, 2020), as well as with the corresponding cw in the years 2015–2019. Data on all-cause and pre-hospital mortality within the area of the NVN were retrieved from the Department of Health, and the responsible emergency medical services. Data on known triggers for systemic inflammation, e.g., respiratory viruses and air pollution, were analyzed. Hospitalizations for SAH decreased during the shutdown period to one-tenth within the multicenter NVN. There was a substantial decrease in acute respiratory illness rates, and of air pollution during the shutdown period. The implementation of public health measures, e.g., contact restrictions and increased personal hygiene during the shutdown, might positively influence modifiable risk factors, e.g., systemic inflammation, leading to a decrease in the incidence of SAH.

Keywords: aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, aneurysm, inflammation, neurosurgery, stroke, COVID-19, Poisson regression

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic due to the novel coronavirus 2 (CoV2) caused a worldwide sudden and substantial increase in hospitalizations for pneumonia with and without multiorgan disease, which prompted the worldwide implementation of public health measures in order to reduce viral transmission. The German government response was a public shutdown, where several facilities including schools/day care, malls, and restaurants were closed, and people were encouraged to stay at home. This led to an overall reduction in emergency department visits, especially of patients with low acuity, as demonstrated among others by data from 29 university clinics and 7 large centers within Germany [1]. While this phenomenon served as an explanation for the decrease in admissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians were concerned about an increase in the case fatality and complication rates of AMI [2]. This led to the conclusion that countermeasures must be implemented in order to avoid further social impact.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases such as aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) share the same modifiable risk factors, including arterial hypertension and smoking [3]. Increasing evidence points to inflammation as the leading factor in the development of intracranial aneurysms (IA), as well as in destabilization of the aneurysm wall leading to aneurysm rupture and SAH [4,5,6]. Systemic inflammation and inflammatory cascades promote endothelial dysfunction, plaque instability, as well as platelet and coagulation activity, leading to cardio- and cerebrovascular events [7]. Systemic inflammation in turn is known to be induced by smoking, infections (e.g., acute respiratory infections, influenza), and air pollution [6,8]. Therefore, guidelines for the treatment of AMI and cerebrovascular diseases recommend the reduction in modifiable risk factors, e.g., by cessation of smoking, and influenza vaccination in order to prevent the inflammatory trigger [9,10]. SAH is a devastating condition with high morbidity and mortality. The clinical hallmark of SAH is a history of severe headache with sudden onset. Half of the patients develop unresponsiveness for a period of time, and one third develop focal deficits, so that SAH patients were usually referred to hospital by emergency medical services [11,12,13]. Therefore, the rate of hospital admissions for SAH is not expected to vary due to the patients’ fear of COVID-19 transmission in the hospitals.

The aim of the present study was to analyze the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown on admission rates of SAH, as well as on its modifiable risk factors driving systemic inflammation as a trigger for aneurysmal instability and rupture.

2. Materials and Methods

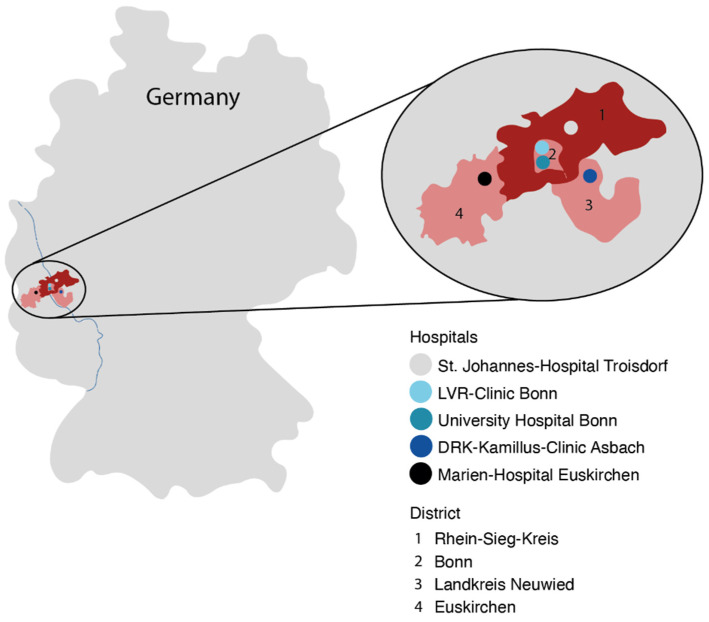

We performed a multicenter study within the neurovascular network “NeuroVask Bonn/Rheinland” (NVN) with a predefined catchment area. In order to improve access for neurovascular diseases (e.g., interventional recanalization therapies, endovascular and neurosurgical aneurysm treatment), the NVN was initiated by neurology departments with acute stroke units, neuroradiology departments, cardiology departments, vascular surgery departments, and a neurosurgical department for neurosurgical intervention and treatment of patients with SAH, in the metropolitan area Bonn/Rhein-Sieg with 1.1 million inhabitants (Figure 1). All patients with suspicious SAH were examined in the local centers of the NVN and triaged to the neuro emergency department (NED) of the University of Bonn when SAH was diagnosed or clarification in the primary hospital was not possible. Patients were stratified according to the Manchester Triage System (MTS) into five groups of urgency and dichotomized into “high urgency” (level red, orange, and yellow) and “low urgency” (level green and blue) [1]. All patients with diagnosed SAH within this network were categorized into “high urgency” and assigned to the neuro-intensive care unit (NICU) of the neurosurgical department of the university hospital Bonn via the NED.

Figure 1.

The neurovascular network “NeuroVask Bonn/Rheinland” (NVN) in Germany, consisting of neurology departments with acute stroke units, neuroradiology departments, cardiology departments, vascular surgery departments, and a neurosurgical department for neurosurgical intervention and treatment of patients with SAH in a metropolitan area with approximately 1.1 million inhabitants.

SAH was diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) or lumbar puncture. All patients with spontaneous SAH underwent four-vessel digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Patients with traumatic origin of SAH were not included in this study.

Clinical data, including patient characteristics on admission and during treatment course, radiological features, and functional neurological outcome were prospectively collected and entered into a computerized database (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) scale was used in order to grade patients on admission. Consistent with the known incidence of SAH ranging between 4–10 per 100,000 patient years [14,15], the hospitalization rates for SAH within the catchment area of the NVN is around 7 per 100,000 patient years from 2013 to 2019, assessed within the prospectively conducted SAH database [5,16]. Baseline characteristics of SAH patients admitted in 2019 and 2020 are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

| 2019 Calendar Weeks 6–26 |

2020 Calendar Weeks 6–26 |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 32 | 15 |

| Mean age (years) | 55 ± 12 | 56 ± 12 |

| WFNS grade | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 |

| Fisher grade 3 | 30 (94%) | 14 (93%) |

| Female gender | 18 (56%) | 9 (60%) |

| Tobacco use | 16 (50%) | 7 (47%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 16 (50%) | 6 (40%) |

| Mean aneurysm size (mm) | 6.7 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 0.5 |

| Aneurysm location | ||

| AComA + ACA | 13 (41%) | 7 (47%) |

| ICA | 5 (16%) | 3 (20%) |

| MCA | 11 (34%) | 3 (20%) |

| Posterior circulation | 3 (9%) | 2 (13%) |

| Time from ictus to hospitalization (h) | 7 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

Values represent number of patients unless otherwise indicated. WFNS = World Federation of Neurological Surgeons; ACA = anterior cerebral artery; AcomA = anterior communicating artery; ICA = internal carotid artery; MCA = middle cerebral artery.

2.1. Time Periods

The public shutdown in Germany started in calendar week 12, 2020, with an impact on public life by extended health measures and social distancing in order to reduce viral transmission, and lasted until the end of calendar week 16. The calendar weeks 6 to 11, 2020, were defined as the weeks prior to the shutdown, but with increasing awareness including hygiene measures and social distancing.

The calendar weeks 17–21 and 22–26, 2020, were defined as the weeks after the public shutdown with relaxing shutdown measures.

2.2. Mortality

Data on mortality in the NVN area was derived from the Department of Health for comparable periods (1 February–30 April) in 2019 and 2020.

2.3. Preclinical Data

In the region of the NVN “NeuroVask Bonn/Rheinland”, patients with acute neurovascular events (e.g., stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage) are managed by an emergency medical service (EMS) coordinated by synchronized and uniquely acting dispatch centers. Patients with neurovascular events are referred to the stroke units of the NVN nearby for primary diagnosis and treatment. In case of diagnosed SAH within the NVN, patients were referred to the neurosurgical department of the university of Bonn via NED.

Within the NVN, the transfer pathways for patients with potential neurovascular diseases are established, and an initial training was performed for the EMS in 2017. There was no change in the system configuration during the study period and the pandemic. In order to identify pre-hospital findings and mortality, as well as the assumed cause of death, the operational documents of the responsible EMS within the network were analyzed retrospectively within the corresponding periods of 2019 and 2020.

2.4. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses

Surveillance data on influenza, influenza-like-illness (ILI), and acute respiratory infections (ARI)—excluding SARS-CoV-2 infection—for the calendar weeks 6–26 were derived from the internet-based syndromic monitoring system “GrippeWeb” [17] of the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the federal public health institute in Germany. The number of confirmed influenza reports submitted to the RKI were retrieved from Survstat (SurvStat@rki.de).

2.5. Air Pollution

Air quality data of the NVN area for the calendar weeks 6–26 2020 were derived from the State Agency for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection of North Rhine Westphalia (LANUV). All measurements were based on hourly readings. The data included pollutants known to drive systemic inflammation: NOx, NO2, and particulate matter (PM10).

2.6. Statistics

Categorial variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) and compared by the Mann−Whitney U test. Hospitalization rate of SAH-patients was modeled by Poisson regression with log-link adjusted by time (year, weeks) using R software 4.0.4. The contrasts were estimated based on generalized linear hypothesis. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for all other analyses.

2.7. Ethic

The present study was approved by the local ethic committee.

3. Results

Between 1 January 2018 and 17 May 2020, 164 patients with SAH were treated in the neurosurgical department of the University of Bonn/within the NVN.

3.1. SAH before Shutdown

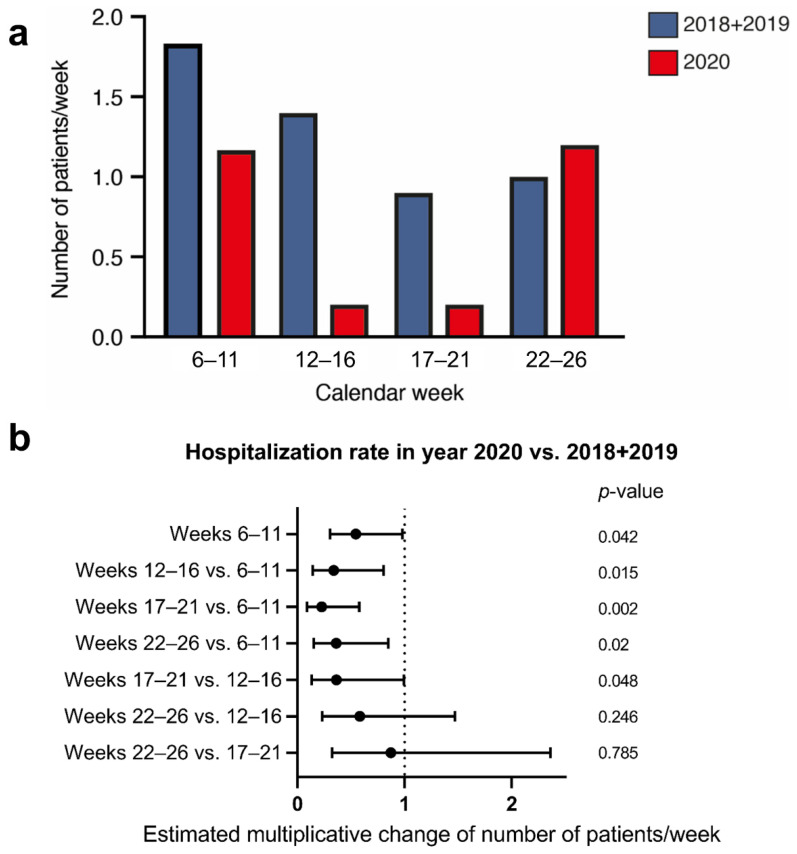

There was no difference in hospitalization rates for SAH in the calendar weeks 6–11, 2020, before the shutdown (n = 7, 1.2 ± 0.7 patients/week) compared to the hospitalization rates in the corresponding calendar weeks of the years 2018 + 2019 (n = 22, 1.8 ± 1.3 patients/week) (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Columns demonstrating hospitalization rates for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) within the calendar weeks 6 to 26 in the years 2018 + 2019 (blue) and in the year 2020 (red). The public shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic was announced for calendar weeks 12–16. The calendar weeks 6–11 were before, and the weeks 17–21 and 22–26 after, the public shutdown. (b) Forest plot visualizing the Poisson regression. The x-axis represents the multiplicative change of the hospitalization rate of SAH-patients at a given time period. Upper bounds of the confidence intervals below one correspond to p-values < 0.05.

3.2. SAH during the Shutdown

The hospitalization rate for SAH during the shutdown in the calendar weeks 12–16 and 17–21, 2020 (p = 0.015 and p = 0.002), was significantly lower compared to the corresponding calendar weeks in the years 2018 + 2019 according to the Poisson regression (Figure 2b).

3.3. Case Severity in the Neuro Emergency Department

The number of patients—MTS levels green and blue (low urgent)—admitted via the NED decreased in the corresponding calendar weeks of 2020, compared to 2019 (data not shown).

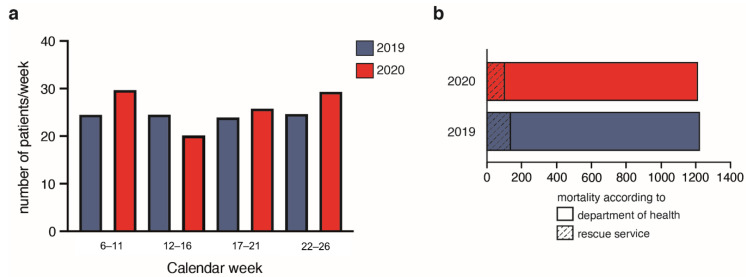

The number of patients—MTS levels red, orange, and yellow (high urgent)—admitted via NED did not differ between the years 2019 and 2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Number of patients in the neuro emergency department (NED) admitted in the years 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red) with Manchester Triage Scale levels red, orange, and yellow (high urgent). (b) Mortality according to the Department of Health for the periods 1 February to April 30 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red). Out-of-hospital mortality is indicated as dashed lines within the columns.

3.4. Mortality

According to the Department of Health, 1218 people died between 1 February 2019 and 30 April 2019 compared to 1205 between 1 February 2020 and 30 April 2020. There was no excess mortality within the area of the neurovascular network within these compared periods (Figure 3).

According to the data from the responsible rescue service and the fire department, out of hospital deaths were noted in 137 cases between 1 February 2019 and 30 April 2019, compared to 101 cases between 1 February 2020 and 30 April 2020 (Figure 3). According to the operational protocols of the emergency physicians, no patient died with the suspicion of subarachnoid hemorrhage (e.g., due to prior acute onset headache) in the time periods 1 February 2019 and 30 April 2019, as well as between 1 February 2020 and 30 April 2020.

3.5. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses

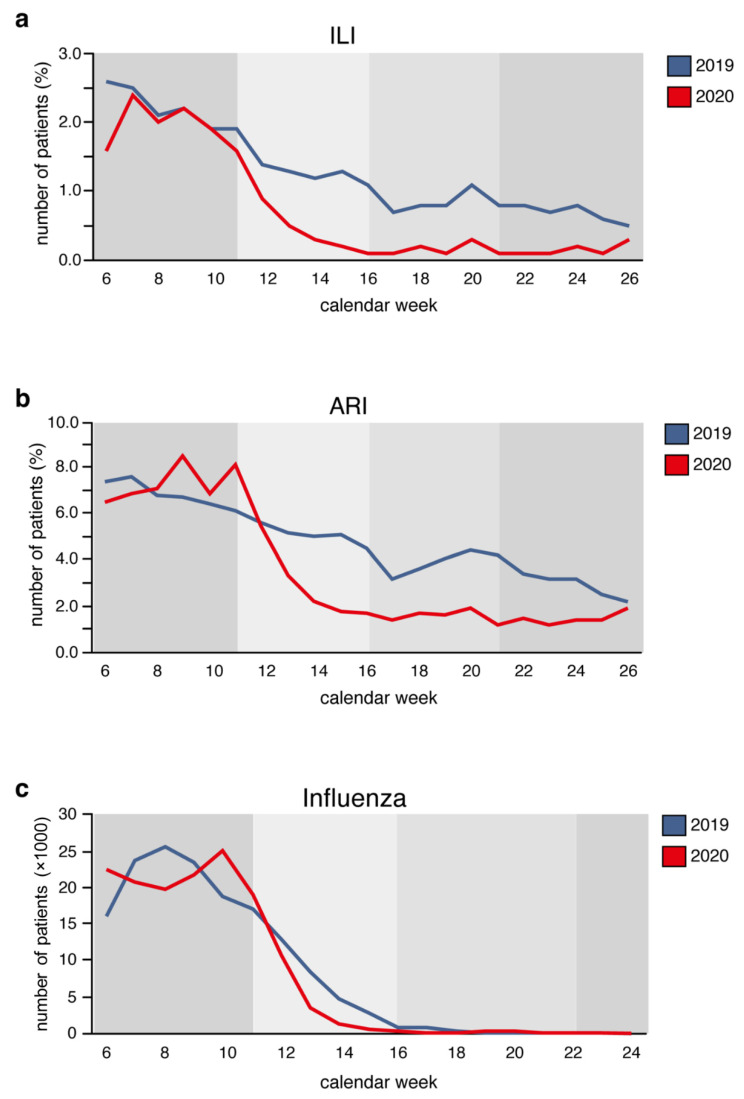

According to the internet-based syndromic monitoring system (Grippeweb), and data retrieved from Survstat, the reported rates of influenza, influenza-like-illness (ILI), and acute respiratory infections (ARI) have fallen substantially during the shutdown period compared to the year 2019 in Germany (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The rate of (a) influenza-like illness (ILI) and (b) acute respiratory illness (ARI) measured by GrippeWeb, excluding SARS-CoV-2 infections, as well as the number of (c) influenza reports submitted to the Robert Koch Institute within the weeks 6–26 in the years 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red). The public shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic was announced for calendar weeks 12–16. The calendar weeks 6–11 were before, and the weeks 17–21 and 22–26 after, the public shutdown.

3.6. Air Pollution

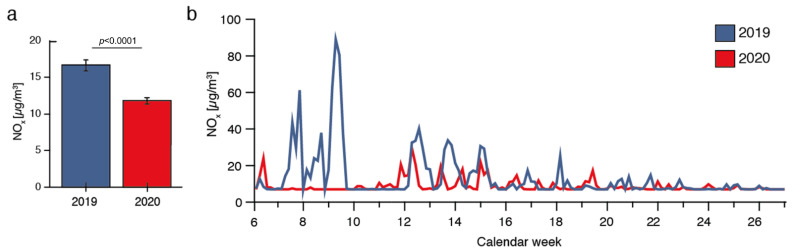

According to the State Agency for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection of North Rhine Westphalia (LANUV), air pollution, including NOx, NO2, and PM10 decreased during the shutdown period compared to the year 2019 and is exemplified for NOx of the measuring station within the city of Bonn in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Air pollution within the calendar weeks 6–26 in the years 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red) during the public shutdown, exemplified for NOx of the measuring station within the city of Bonn (data according to the State Agency for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection of North Rhine Westphalia (LANUV)). Boxplots for mean values (a) and distribution of NOx for the weeks 6–26 in the years 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red) (b).

4. Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that admission rates for SAH decreased to one-tenth during the shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic within a multicenter NVN in Germany.

While the proposed explanation leading to the reduced admission rates for SAH is speculative, it is evident that the public health measures in order to reduce viral transmission, i.e., public shutdown, contact restrictions, increasing awareness, and hygiene measures, reduced the risk factors for systemic inflammation, which in turn is a modifiable risk factor for cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases such as SAH.

There is growing evidence that SAH is the result of a chronic cerebrovascular inflammatory disease that leads to the development of aneurysms if other factors, e.g., arterial hypertension and genetic predisposition, among others, are present [6,18]. Aneurysms that go on to rupture might do so relatively early after formation when the aneurysm wall is weak and before healing processes begin, e.g., stimulated by an inflammatory trigger. Aneurysms that do not rupture at the initial stage, may reach a stable condition with a lower risk of rupture [4,6,19].

Therefore, the lower rates of hospital admissions for SAH might be the result of a lower rate of aneurysm formation, or of aneurysm rupture, both of which are thought to be the result of an inflammatory trigger.

Cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases share similar risk factors. Acute infections increase the risk of vascular events, i.e., AMI and Stroke [20]. For AMI, meta-analysis indicates the effectiveness of influenza vaccination up to 45%, being similar to smoking cessation [9,10]. For the prevention of cerebral infarction, vaccination for influenza is associated with lower risk of stroke events [21]. There is evidence that nearly all types of infectious agents increase the incidence of stroke [22]. ILI is associated with stroke events [23]. For SAH, one case-control study identified an association of recent respiratory infections and aneurysmal SAH [24]. Backes et al. [25] found an increased incidence of SAH during cold temperatures and epidemic influenza. The systemic inflammatory response induced by influenza accelerates endothelial injury by impairing vasodilatation by metabolic derangements, and enhances thrombotic tendencies through altered clotting factors and platelet dysfunction [26]. The substantial and early decreased rates of influenza, ILI, and ARI during the shutdown period in 2020 compared to the year 2019 might therefore be one part of an explanation for the decreased admission rates of SAH in the same period in 2020.

4.1. Neuro Emergency Department and Referral within the Neurovascular Network

Hospital admissions of patients—Manchester Triage Scale levels red, orange, and yellow (high urgent)—via NED did not differ between the years 2019 and 2020. Within the NVN, the transfer pathways for patients with potential neurovascular diseases are established, and an agreement between the hospitals exists for direct referrals and contemporaneous image transfer, if applicable. Within this area-wide network, the rescue services were urged to transfer patients between the treating centers, depending on the primary diagnosis. All patients with diagnosed SAH or the strong suspicion of SAH were referred to the neurosurgical center via NED. After retrospective review of the operational documents of the responsible EMS within the network, there was neither a difference in the referral of patients within the network, nor a higher pre-hospital mortality, which also promotes the assumption that the incidence of SAH decreased during the shutdown for the pandemic. This is also corroborated by the fact that there was no increase in overall mortality within the NVN area according to the Department of Health.

4.2. Air Pollution

Air pollution is a known environmental modulator of cardiac function [27] by systemic and pulmonary inflammation and oxidative stress, as well as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [28,29]. Furthermore, evidence concerning the association of air pollution and brain pathology is growing [30]. Air pollutants (e.g., PM10, NOx, and others) were associated with increased hospitalization and adverse outcomes of stroke in a meta-analysis [31]. The pathophysiological mechanisms remain unclear; however, even short-term exposure to air pollution leads to an inflammatory response with increased levels of, e.g., C-reactive protein and IL-6 [32,33]. This systemic inflammation is held responsible for acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events such as ischemic stroke [31,34] and might also be a trigger for SAH [6,8].

Therefore, the reduced rates of admission for SAH might be explained by the environmental and behavioral changes during the pandemic; lower levels of air pollution and less physical and emotional strain at work may reduce the incidence of SAH [31,35].

Air pollution decreased markedly within the area of the NVN during the pandemic, as it was described for many countries world-wide [36,37]. Furthermore, the effect of wearing facial masks could also have provided protection from pollutants in addition to reduced air pollution by reduced traffic.

While there are no data on potential changes in tobacco use within the NVN, there are data in the literature indicating that the knowledge of COVID-19 is associated with a reduction in cigarette and e-cigarette use, as well as an increase in motivation to quit smoking [38]. In an online survey, researchers found that the desire to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection prompted a quarter of respondents to reduce their cigarette consumption and more than one-third to increase their motivation to quit. It is unclear how successful and how stable this motivation for the reduction in smoking was or will be.

While one of the possible explanations for reduced rates of hospitalization for AMI might be the fear of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there is evidence that the reduced rates of hospitalization for SAH might be due to the reduction in modifiable risk factors driving systemic inflammation, which is a known risk factor for aneurysm rupture and SAH.

Patients with SAH might also be afraid of viral transmission, such as patients with AMI. However, in contrast to AMI, we did not observe delayed referral after SAH or excess mortality according to data from the Department of Health. Furthermore, there was no increase out of hospital mortality and no patient found dead with evidence of SAH in the time periods of 2019 and 2020 according to the data of the EMS.

Altogether, we provide data on reduced rates of hospitalization for SAH within a multicenter NVN during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesize that the reduction in modifiable risk factors driving systemic inflammation (e.g., respiratory infections, air pollution, less physical strain at work) may play a key role in the reduction in SAH admissions by decreasing the risk of aneurysm rupture (see Graphical Abstract). Due to the similar risk factors for cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases, reduced systemic inflammation might also be a part of the explanation for reduced rates of hospital admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic for ischemic stroke and AMI.

The secondary increase in SAH admissions after the end of the shutdown to the same rates compared to the period before the pandemic might reflect the return of some of the modifiable risk factors for SAH. It is obvious that complex pathophysiological processes might not be turned on and off like a light switch, especially when SAH may result from a preexisting or a newly developed aneurysm that might differ in its risk factors or thresholds for rupture. Furthermore, we identified only a few of the known risk factors for SAH. We have no data on hypertension, smoking, and genetic predisposition of the population, as well of their stability or changes during the pandemic, within the NVN.

5. Conclusions

Hospitalization rates for SAH were reduced during the shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic within a multicenter neurovascular network in Germany. The implementation of public health measures, e.g., contact restrictions and increased personal hygiene during the shutdown, might positively influence modifiable risk factors, e.g., systemic inflammation, leading to a decrease in the incidence of SAH.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Udo Buchholz from the Robert Koch-Institute for sharing the surveillance data on ILI and ARI, as well as for the very helpful discussions and interpretations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and I.G.; methodology, E.G. and I.G.; data curation, E.G., I.G., M.S. (Matthias Seidel), H.B., C.C., C.D. (Christian Diepenseifen), C.D. (Christian Dohmen), S.E., A.H., U.H., I.H., T.L., S.P., G.P., D.P., C.P., M.S. (Matthias Schneider), P.S., J.T. and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, E.G., I.G., M.S. (Matthias Seidel), H.B., C.C., C.D. (Christian Diepenseifen), C.D. (Christian Dohmen), S.E., A.H., U.H., I.H., T.L., S.P., G.P., D.P., C.P., M.S. (Matthias Schneider), P.S., J.T., M.V., J.W. and T.W.; visualization E.G., I.G. and T.W.; supervision H.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Bonn (ID 107/20).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient informed consent was not necessary according to the retrospective character of the study and after approval from our Ethics Committee Approval.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Slagman A., Behringer W., Greiner F., Klein M., Weismann D., Erdmann B., Pigorsch M., Möckel M. Medical Emergencies During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020;117:545–552. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C., Calabrò M.P., Curcio A., Filardi P.P., Mancone M., Mercuro G., Muscoli S., Nodari S., et al. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasen T.H., Bartek J., Andresen M., Springborg J.B., Romner B. Modifiable risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:3607–3612. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shao L., Qin X., Liu J., Jian Z., Xiong X., Liu R. Macrophage Polarization in Cerebral Aneurysm: Perspectives and Potential Targets. J. Immunol. Res. 2017;2017:8160589. doi: 10.1155/2017/8160589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Güresir E., Coch C., Fimmers R., Ilic I., Hadjiathanasiou A., Kern T., Brandecker S., Güresir Á., Velten M., Vatter H., et al. Initial inflammatory response is an independent predictor of unfavorable outcome in patients with good-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Crit. Care. 2020;60:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalouhi N., Hoh B.L., Hasan D. Review of cerebral aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture. Stroke. 2013;44:3613–3622. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J., Yalkun G., Wang M., Wang A., Wangqin R., Zhang X., Chen Z., Mo J., Meng X., Li H., et al. Impact of Infection on the Risk of Recurrent Stroke Among Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:2395–2403. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han M.-H., Yi H.-J., Ko Y., Kim Y.-S., Lee Y.-J. Association between hemorrhagic stroke occurrence and meteorological factors and pollutants. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:59. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes M., Heywood A.E., Mahimbo A., Rahman B., Newall A.T., MacIntyre C.R. Acute myocardial infarction and influenza: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. Heart. 2015;101:1738–1747. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacIntyre C.R., Mahimbo A., Moa A.M., Barnes M. Influenza vaccine as a coronary intervention for prevention of myocardial infarction. Heart. 2016;102:1953–1956. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeulen M.J., Schull M.J. Missed diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the emergency department. Stroke. 2007;38:1216–1221. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259661.05525.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Gijn J., Rinkel G.J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: Diagnosis, causes and management. Brain. 2001;124:249–278. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hop J.W., Rinkel G.J., Algra A., van Gijn J. Initial loss of consciousness and risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:2268–2271. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.11.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walendy V., Strauss C., Rachinger J., Stang A. Treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in Germany: A nationwide analysis of the years 2005–2009. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42:90–97. doi: 10.1159/000355843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Rooij N.K., Linn F.H.H., van der Plas J.A., Algra A., Rinkel G.J.E. Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: A systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2007;78:1365–1372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.117655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaremba S., Albus L., Schuss P., Vatter H., Klockgether T., Güresir E. Increased risk for subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients with sleep apnea. J. Neurol. 2019;266:1351–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayer C., Remschmidt C., an der Heiden M., Tolksdorf K., Herzhoff M., Kaersten S., Buda S., Haas W., Buchholz U. Internet-based syndromic monitoring of acute respiratory illness in the general population of Germany, weeks 35/2011 to 34/2012. EuroSurveill. 2014;19:20684. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.4.20684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saand A.R., Yu F., Chen J., Chou S.H.-Y. Systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic strokes—A novel neurological sign and therapeutic target? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39:959–988. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19841443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Güresir E., Vatter H., Schuss P., Platz J., Konczalla J., de Du Rochement R.M., Berkefeld J., Seifert V. Natural history of small unruptured anterior circulation aneurysms: A prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2013;44:3027–3031. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smeeth L., Thomas S.L., Hall A.J., Hubbard R., Farrington P., Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2611–2618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee K.R., Bae J.H., Hwang I.C., Kim K.K., Suh H.S., Ko K.D. Effect of Influenza Vaccination on Risk of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000478017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grau A.J., Urbanek C., Palm F. Common infections and the risk of stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010;6:681–694. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehme A.K., Luna J., Kulick E.R., Kamel H., Elkind M.S.V. Influenza-like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018;5:456–463. doi: 10.1002/acn3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunze A.K., Annecke A., Wigger F., Lichy C., Buggle F., Schnippering H., Schnitzler P., Grau A.J. Recent infection as a risk factor for intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhages. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2000;10:352–358. doi: 10.1159/000016090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Backes D., Rinkel G.J.E., Algra A., Vaartjes I., Donker G.A., Vergouwen M.D.I. Increased incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage during cold temperatures and influenza epidemics. J. Neurosurg. 2016;125:737–745. doi: 10.3171/2015.8.JNS151473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naghavi M., Wyde P., Litovsky S., Madjid M., Akhtar A., Naguib S., Siadaty M.S., Sanati S., Casscells W. Influenza infection exerts prominent inflammatory and thrombotic effects on the atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2003;107:762–768. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000048190.68071.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorr M.W., Falvo M.J., Wold L.E. Air Pollution and Other Environmental Modulators of Cardiac Function. Compr. Physiol. 2017;7:1479–1495. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brook R.D., Rajagopalan S., Pope C.A., Brook J.R., Bhatnagar A., Diez-Roux A.V., Holguin F., Hong Y., Luepker R.V., Mittleman M.A., et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen A.J., Brauer M., Burnett R., Anderson H.R., Frostad J., Estep K., Balakrishnan K., Brunekreef B., Dandona L., Dandona R., et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calderón-Garcidueñas L., Azzarelli B., Acuna H., Garcia R., Gambling T.M., Osnaya N., Monroy S., Del Tizapantzi M.R., Carson J.L., Villarreal-Calderon A., et al. Air pollution and brain damage. Toxicol. Pathol. 2002;30:373–389. doi: 10.1080/01926230252929954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah A.S.V., Lee K.K., McAllister D.A., Hunter A., Nair H., Whiteley W., Langrish J.P., Newby D.E., Mills N.L. Short term exposure to air pollution and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W., Dorans K.S., Wilker E.H., Rice M.B., Ljungman P.L., Schwartz J.D., Coull B.A., Koutrakis P., Gold D.R., Keaney J.F., et al. Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Biomarkers of Systemic Inflammation: The Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017;37:1793–1800. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y., Rittenhouse-Olson K., Scheider W.L., Mu L. Effect of particulate matter air pollution on C-reactive protein: A review of epidemiologic studies. Rev. Environ. Health. 2012;27:133–149. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2012-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X.-Y., Yu X.-B., Liang W.-W., Yu N., Wang L., Ye X.-J., Chen K., Bian P.-D. Meta-analysis of association between particulate matter and stroke attack. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012;18:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kivimäki M., Jokela M., Nyberg S.T., Singh-Manoux A., Fransson E.I., Alfredsson L., Bjorner J.B., Borritz M., Burr H., Casini A., et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603 838 individuals. Lancet. 2015;386:1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menut L., Bessagnet B., Siour G., Mailler S., Pennel R., Cholakian A. Impact of lockdown measures to combat COVID-19 on air quality over western Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741:140426. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen K., Wang M., Huang C., Kinney P.L., Anastas P.T. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Lancet Planet. Health. 2020;4:e210–e212. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klemperer E.M., West J.C., Peasley-Miklus C., Villanti A.C. Change in Tobacco and Electronic Cigarette Use and Motivation to Quit in Response to COVID-19. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22:1662–1663. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.