Abstract

A non-contact, non-invasive monitoring system to measure and estimate the heart and breathing rate of humans using a frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) mm-wave radar at 77 GHz is presented. A novel diagnostic system is proposed which extracts heartbeat phase signals from the FMCW radar (reconstructed using Fourier series analysis) to test a three-layer artificial neural network model to predict the presence of arrhythmia in individuals. The effect of person orientation, distance of measurement and movement was analyzed with respect to a reference device based on statistical measures that include number of outliers, mean, mean squared error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), median absolute error (medAE), skewness, standard deviation (SD) and R-squared values. The individual oriented in front of the radar outperformed almost all other orientations for most distances with an expected d = 90 cm and d = 120 cm. Furthermore, it was found that the heart rate that was measured while walking and the breathing rate which was measured for a motionless individual generated results with the lowest SD and MSE. An artificial neural network (ANN) was trained using the MIT-BIH database with a training accuracy of 93.9 % and an R2 value = 0.876. The diagnostic tool was tested on 15 subjects and achieved a mean test accuracy of 75%.

Keywords: mm-wave radar, artificial neural network, vital signs, machine learning

1. Introduction

Developing continuous vital sign monitoring systems has been identified by healthcare institutes as necessary to safeguard the health of seriously ill patients or infants in hospitals or at home [1,2,3,4]. Current systems of monitoring heart rate variability (HRV) involve the usage of electrocardiography (ECG) electrodes, pulse oximeter, photoplethysmography (PPG) and wearable devices such as the OMRONTM 10 series. Breathing rate is measured manually using a timer or using oronasal sensors, which measure fluctuations in air pressure due to respiration [5]. These traditional methods can be inaccurate due to random body movements (RBM) and can cause discomfort for users, especially when used for ambulatory monitoring. Recently, radar-based solutions have been proposed for non-contact measurement of heart rate and respiration rate. The most popularly used radars include continuous-wave (CW) Doppler radars [6,7,8,9,10,11], impulse radio ultra-wideband (IR UWB) radars [12,13] and frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) Doppler radars [14,15,16,17]. Lazaro et al. [18] presented a feasibility study on an IR-IWB radar-based vital sign monitoring system. However, the weak heart signal was difficult to isolate from external noise, respiratory harmonics and third-order intermodulation products, which can lead to inaccurate heart rate readings. In [19], a novel radar hardware system is proposed that utilizes a sweeping correlation method, which applies a small-frequency difference to the received impulse train, thereby increasing repetition frequency and measurement accuracy. However, the proposed method has only been used to detect respiratory waves. Additionally, IR UWB radars have long been used in several wireless sensing use cases, such as people counting and detection [20], human detection through walls [21], home monitoring and remote care systems [22] and classification of humans and animals based on vital signs [23]. Since the power transmitted by the pulse (the IR-UWB radars transmit multiple short Gaussian pulses without a carrier frequency) increases the signal-to-noise ratio, it also necessitates a high-frequency analogue-to-digital converter (ADC), which increases the cost, power consumption and complexity of design [24]. CW radars are only capable of detecting relative displacements using phase differences; hence, they are incapable of localizing objects when multiple moving objects are around. However, FMCW radars are capable of localizing objects based on changes in frequency and phases between transmitted and received chirps [25,26].

FCMW radars overcome the shortcomings of CW radars, as extremely high frequency (EHF) radar systems operating in the 110–300 GHz frequency band can detect displacements in the order of cm-mm and become absorbed on the skin of an individual without causing any harmful biological effects [27,28]. Moreover, the MIMO antenna framework allows us to localize multiple targets; hence, we are able to monitor multiple moving targets simultaneously using beamforming techniques [17]. In [29], a TI-AWR1443 FMCW radar operating in the 77 GHz band is utilized to detect vital signs for a person lying on a bed using the phase-unwrapping algorithm proposed in [30]. It was found that the regression coefficient values of BR and HR values were 0.883 and 0.64 when compared to the reference hexoskin contact sensor [31].

In most studies, radars are solely used for monitoring heart rate and breathing rate. In this work, we used a three-layered artificial neural network to predict the onset of arrhythmia based on statistical features extracted from the phase signals of a localized range bin using an FMCW radar. Additionally, a signal reconstruction module is proposed that helps generate phase signals with higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) values. The radar was also tested in comparison to a reference device, i.e., OMRON, to analyse and compare the effect on vital signs’ detection due to varying person orientation, distance of measurement and random body movements.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the mathematical background, algorithmic workflow of the system and the proposed prediction flow for arrhythmia are described. The results of the experiments are discussed in detail in Section 3. Finally, the advantages and potential future work is outlined in Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

The system setup consisted of Texas Instrument (TI) IWR1443BOOST FMCW radar-based evaluation module, Omron device connected to a personal computer (PC) as shown in Figure 1. TI IWR IWR1443BOOST operates in the 76–81 GHz band with 3 transmitting antennas and 4 receiving antennas.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the proposed mm-wave radar system: an mm-wave radar is fixed at front of the subject while an Omron sphygmomanometer is attached, which simultaneously extracts pulse readings for verification. The radar data are recorded on a PC through a USB connection.

2.1. FMCW Radars

Frequency-modulated signals are robust against additive noise such as thermal noise unlike amplitude-modulated waves. In [17], FMCW transmitted and received chirps were modelled as increasing ramp functions as shown in Figure 2. The transmitted signal is given by:

| (1) |

where are the amplitude of the transmitted signal, chirp start frequency and bandwidth of chirp and chirp duration, respectively.

Figure 2.

Transmitted and received chirp signals where each chirp is a sinusoidal signal with a slope S and time delay between transmitted and received chirp when the sweeping bandwidth is S.

Since we are measuring vital signs of a single target within the field of view, we assume a single reflection model where the received chirp given by Equation (2) is scaled by factor and time shifted by .

| (2) |

Here, is the time delay from the subject. is the time-dependent radar range.

The intermediate frequency signal after I/Q mixing is approximated as

| (3) |

where beat frequency , is residual phase noise, which can be neglected for our short range (<1.5m) detection experiments due to the range correlation effect [32]. Additionally, the additional term is negligible, so it can be neglected. Hence, the IF signal for the ADC sample and chirp is given by:

| (4) |

where , , are the received signal power, beat frequency, sampling time of fast-time axis and sampling time of slow-time axis, respectively. To improve the angular resolution, a time division multiplex multiple-input multiple-output (TDM-MIMO) radar system is used that consists of 2 transmitting and 4 receiving antennas. Since and assuming a planar wavefront, the received wave must travel an additional distance of as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A MIMO radar with two transmitting antennas (Tx) and four receiving antennas (Rx) where distance between two receiving antennas is and is the angle of arrival.

Thus, an additional phase shift between the receivers and the beat signal is given by:

| (5) |

where the receiving antennas are distance apart. Hence, the phase shift at receiver is given by:

| (6) |

As we measure displacements of < 5 mm, frequency < 2 Hz and a single target in the same range bin, there would be no change in phase across the fast-time axis, i.e., phase change will be constant. Therefore, gives us:

| (7) |

| (8) |

where is constant. We are mainly concerned with phase changes along the slow-time axis. However, changes in can adversely affect our results so all our experiments (except Section 3.3) were carried out for stationary subjects only.

2.2. Process Flow for the Detection of Vital Signs

The process flow for the detection of the vital signs is shown in Figure 4. As described in [17], each chirp signal sampled at the beat frequency is converted to a complex range profile by applying the range fast Fourier transform (FFT). Range profiles of multiple chirp signals are stacked on top of each other and converted into a matrix with i number of rows (fast time samples) and j columns (slow-time samples). As summarized in Table 1, the slow-time axis rate is 20 chirps/sec where the duration of the chirp is 50 µs. Since vital signs are detected for a stationary person, the phase change across the slow-time axis is extracted from a single range bin. The phase-unwrapping algorithm is then implemented to unwrap the phase beyond (−).

Figure 4.

Signal processing workflow: after applying the range FFT, for a single range bin, the angle FFTs are computed, upon which the phase shift is used to extract the heartbeat and breathing waves.

Table 1.

Vital signs measurement parameters.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Starting frequency | 77 GHz |

| Slow axis sampling | 20 Hz (chirps/s) |

| Chirp duration | 50 µs |

| ADC sampling rate | 2 Msps |

| Range resolution | 4.3 cm |

| Transmitted power | 10 dBm |

Next, the phase values are filtered using a serially cascaded Bi-Quad Infinite impulse response (IIR) filter into the cardiac frequency spectrum of (0.8–2) Hz and the breathing frequency spectrum of (0.1–0.5) Hz. The motion denoising module computes the energy of the waveform for a window size of 1 sec and discards the windowed waveform if it exceeds a threshold of Eth = 0.04. The maximum and minimum peak-to-peak distance threshold is automatically computed based on the mean of all distances. A peak is rejected if it is out of 1 standard deviation from the mean. Finally, the breathing rate and heart rate are computed based on the frequency of filtered peaks within their respective frequency spectrums as mentioned earlier. Additionally, for our experiment, we propose a QRS complex generation module, which extracts the signal peaks and base period of the heartbeat phase signal to mimic QRS-based radar heartbeat signals using Fourier series representation of triangular waveforms, thus eliminating signal overshoots, aperiodicity and improving the SNR value of the extracted signal as described in the next section. The QRS complex refers to a combination of Q, R and S waves, which represent the ventricular depolarization of the heart. The QRS complex is the most vital part of an ECG signal because it contracts the ventricles as the oxygenated blood from the left ventricle is pumped out from the heart to other parts of the body, which corresponds to maximum electrical activity (highest voltage amplitude). Our proposed system detects R peaks that have the largest amplitude within a QRS complex to extract statistical features based on the peak-to-peak interval (RR interval) of the ECG signal sequence.

2.3. Heartbeat Signal Generation

An ECG signal is a periodic wave signal that satisfies the Dirichlet conditions. It can be modelled as a combination of scaled amplitude and multiples of fundamental frequency of sinusoidal and cosine functions using Fourier series expansion. The QRS components can be modelled by a symmetric triangular wave function as shown in Figure 5. Consider the even symmetric triangular wave function given by (9):

| (9) |

where T is the time period, A is the amplitude, and B is the factor which determines the QRS interval.

Figure 5.

Symmetric triangular wave function to model the QRS components of an ECG signal.

Since is an even function, . Fourier series coefficients are formulated as:

| (10) |

| (11) |

Hence, Fourier series coefficients can be substituted in (12).

| (12) |

where which is the multiple of fundamental frequency.

2.4. Arrhythmia Detection Using Neural Networks

This work proposes a cardiac disorder diagnostic scheme using a 3-layer neural network model. The model is trained using ECG signals which lie in the frequency range 0.05~100 Hz, and its maximum amplitude is 5 mV. ECG signals are extracted using electrodes mounted on the body. Hence, some artifacts are filtered out before statistical features can be extracted from the ECG signal database. Artifacts include but are not limited to muscle tremor, electromagnetic interference (EMI) and base-line wander. Muscle tremor artifacts caused due to shivering or sudden body movements (usually in the elderly) are high-frequency signals at 30~300 Hz that are removed by Butterworth low-pass filters. The 50 Hz electromagnetic interference is suppressed by a Butterworth band-stop filter. Lastly, baseline wander is an ultra-low frequency signal that ranges between 0 and 0.8 Hz that can be eliminated using a high-pass filter.

As outlined in Figure 6, after filtering out low- and high-frequency noise, R peaks are detected as shown in Figure 7. The non-rhythmic ECG can be detected by extracting RR-interval-based features that include:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

Figure 6.

Predict the onset of arrhythmia based on statistical features extracted from the phase signals of a localized range bin using an FMCW radar.

Figure 7.

ECG signal pre-processing (left to right): ECG signals are extracted using electrodes mounted on the body. Hence, some artifacts are filtered out before statistical features can be extracted from the ECG signal database. Artifacts include muscle tremor, electromagnetic interference (EMI) and base-line wander. Muscle tremor artifacts caused due to sudden body movements are high-frequency signals (30~300 Hz) that are removed by Butterworth low-pass filters. The 50 Hz electromagnetic interference is suppressed by a Butterworth band-stop filter. Baseline wander is an ultra-low frequency signal that ranges between 0 and 0.8 Hz that can be eliminated using a high-pass filter. Finally, the resultant R peaks of a QRS complex are detected, and only RR interval-based features are extracted since the radar-generated heartbeat phase signals are QRS equivalent signals.

In addition to the above features, age and gender are included as training features. The dataset is then trained using a 3-layer neural network as described in Table 2, which consists of 8 and 16 neurons in the input and hidden layer, respectively. Weights are randomly initialized from the normal distribution function, and sigmoidal activation function is used. The mean square error is the loss function employed, which is backpropagated using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm to train the weights.

Table 2.

Model architecture where Kfold = 5, random seed = 42, loss function = MSE, optimizer = Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, momentum = enabled, early stopping = 10 rounds, autotuning objective function = MSE, autotuning algorithm: grid search, BatchNorm = disabled.

| Autotuned Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Input dense layer | 8 nodes |

| Hidden dense layer | 16 nodes |

| Output dense layer | 1 node |

| Learning rate | 0.01 |

| L1 Regularization | 0 |

| L2 Regularization | 0 |

| Epochs | 10 |

After peak detection of heartbeat phase signals obtained from the radar, training features given by (13)–(17) are extracted to test the trained model. Since we do not have a readily available radar-based signal database, it is important to note that we have restricted the application of our experiments solely to healthy individuals. However, to test the model for positive cases of arrhythmia, unseen signals from the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia dataset were used.

3. Results and Discussion

Our experiments were carried out using TI’s IWR1443BOOST FMCW radar-based evaluation module (EVM), which operates in the 76–81 GHz band with a total bandwidth of 4 GHz. The range profile, chest displacement, heartbeat and respiratory phase differences in addition to the heart rate (HR) and breathing rate (BR) values were displayed on a graphical user interface (GUI) designed using MATLAB R2020a. The radar was placed some distance apart in front of an individual, directly pointed towards their chest. Each observation lasting 25.6 s consisted of 128 data samples. Before we tested the radar for arrhythmia detection, the effect of orientation, distance from radar and movements were analysed and reported.

3.1. Measured Data Validation

Firstly, the heart rate values of the radar were validated based on their deviation from the HR values from our reference cuff-based OMRON device. The radar was placed 50 cm away from the individual and 20 observations were registered, i.e., for every 128 data samples generated by the radar, a corresponding OMRON HR value was registered. After every observation, 1 min of resting time was allotted before another observation was taken. The validation was evaluated based on the metrics described in Table 3. It was observed that the mean HR values were almost same for both the devices. The variance and standard deviation values of HR obtained by the OMRON device were lower than those of the radar. However, it is worth noting that the mean absolute error was only 3.85, i.e., HR values estimated by the radar only deviated by nearly 4.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics to compare cuff-based and radar-based HR monitoring.

| Metric | OMRON | Radar |

|---|---|---|

| Avg HR | 74 | 74 |

| Variance | 13.95 | 8.5 |

| STD | 3.83 | 2.99 |

| R2 | 0.164 | |

| Root mean square error (RMSE) | 2.81 | |

| Mean absolute error (MAE) | 1.9 | |

| Median absolute error (MedAE) | 2 |

3.2. Effect of Orientation and Distance on Measurement

The radar was tested for different orientations, namely, front, back, right and left. For each orientation, the individual was seated in a stationary position at different distances away from the radar at 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 cm. The 10 observations for HR and BR values were recorded for each orientation at varying distances. The number of outliers, mean, MSE, MAE, medAE, skewness and standard deviation were estimated to analyse the effect of orientation and distance. As shown in Table 4, boxes highlighted in orange and green are the best values obtained for HR and BR, respectively. The following observations were made:

Range = 30 cm: As highlighted in green, the number of outliers for front and back were nil, while for right and left orientations the outliers had the greatest values. HR values (highlighted in yellow) when estimated in the front faired the best while analysis shows that BR was least skewed when obtained on the right side with minimized MSE and SD.

Range = 60 cm: Again, the number of outliers for the front and back were nil while both the right and left suffered maximum skewness. The MSE and SD values of HR and BR were the least for the front, which performed the best.

Range = 90 cm: Front and back orientations produced better results in terms of minimum outliers and lower SD values with an exception for the left position, which minimized skewness better.

Range = 120 cm: Following the previous trend, right and left orientations produced poor results with the maximum number of outliers and highly skewed data. Again, individuals oriented in front of the radar outperformed other orientations.

Range = 150 cm: We observed that some of the HR and BR values were estimated to be 0 as the radar was unable to pick up any chest displacements when the person was seated to the left or right. This is reflected in the analysis, which shows the presence of outliers and maximum skewness and SD.

Table 4.

Statistical evaluation of effect of orientation and distance on measurement.

| Distance (cm) | Orientation | Vital Sign | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Outliers | Mean | MSE | MAE | medAE | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | front | HR | 85.375 | 78.375 | 0 | 81.8 | 0.296 | 2.1 | 2 | 1.8 |

| BR | 13.25 | 7.25 | 0 | 10.6 | 0.124 | 0.96 | 0.9 | 1.2 | ||

| right | HR | 87.375 | 58.375 | 0 | 72.3 | 3.741 | 4.9 | 4 | 6.4 | |

| BR | 8 | 8 | 3 | 8.1 | 0.029 | 0.36 | 0.1 | 0.6 | ||

| left | HR | 86.625 | 57.625 | 0 | 72.4 | 2.904 | 4.6 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| BR | 10.5 | 6.5 | 2 | 9.7 | 1.061 | 2.12 | 1.5 | 3.4 | ||

| back | HR | 90.75 | 58.75 | 0 | 75.6 | 2.704 | 4.24 | 5 | 5.5 | |

| BR | 32.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 17.6 | 3.424 | 4.76 | 3.9 | 6.2 | ||

| 60 | front | HR | 92.125 | 67.125 | 0 | 80.1 | 3.129 | 4.46 | 4 | 5.9 |

| BR | 14 | 6 | 0 | 10.4 | 0.144 | 1.12 | 1.4 | 1.3 | ||

| right | HR | 103.25 | 39.25 | 0 | 72 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 10 | |

| BR | 15.875 | 4.875 | 1 | 10.7 | 0.701 | 2.24 | 1.7 | 2.8 | ||

| left | HR | 91 | 63 | 1 | 76 | 4.42 | 5.2 | 4 | 7 | |

| BR | 19.625 | 2.625 | 1 | 11.9 | 2.009 | 3.66 | 2.9 | 4.7 | ||

| back | HR | 81.75 | 67.75 | 3 | 74.1 | 4.269 | 4.7 | 2 | 6.9 | |

| BR | 29.5 | 3.5 | 0 | 16.5 | 1.905 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 4.6 | ||

| 90 | front | HR | 89.5 | 63.5 | 0 | 75.5 | 3.285 | 4.6 | 4 | 6 |

| BR | 10.5 | 6.5 | 1 | 8.8 | 0.076 | 0.64 | 0.5 | 0.9 | ||

| right | HR | 91.375 | 54.375 | 1 | 72.2 | 6.956 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 8.8 | |

| BR | 16.5 | 4.5 | 2 | 12.9 | 4.649 | 5.24 | 3.9 | 7.2 | ||

| left | HR | 94.375 | 63.375 | 0 | 78.6 | 3.004 | 4.92 | 3.6 | 5.8 | |

| BR | 24.75 | −3.25 | 1 | 12.1 | 7.029 | 6.54 | 4.6 | 8.8 | ||

| back | HR | 86.125 | 61.125 | 0 | 73.7 | 1.721 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.4 | |

| BR | 30.375 | −4.625 | 0 | 13.2 | 1.996 | 3.76 | 4.8 | 4.7 | ||

| 120 | front | HR | 104.25 | 56.25 | 0 | 78.6 | 8.624 | 7.72 | 5.1 | 9.8 |

| BR | 14 | 6 | 0 | 9.9 | 0.129 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||

| right | HR | 86.375 | 55.375 | 0 | 71.5 | 2.705 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 5.5 | |

| BR | 19.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 11 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 3 | 4.1 | ||

| left | HR | 93.5 | 57.5 | 1 | 73.7 | 9.841 | 7.42 | 5.5 | 10 | |

| BR | 23.25 | −0.75 | 2 | 12.9 | 5.169 | 5.86 | 4.4 | 7.6 | ||

| back | HR | 87.875 | 52.875 | 0 | 69 | 4.56 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 7.1 | |

| BR | 36.25 | −5.75 | 0 | 15.2 | 2.636 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 5.4 | ||

| 150 | front | HR | 88.875 | 63.875 | 0 | 75.9 | 1.949 | 3.88 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| BR | 12.75 | 6.75 | 0 | 9.6 | 0.144 | 1.04 | 0.6 | 1.3 | ||

| right | HR | 87.125 | 54.125 | 1 | 70.8 | 8.296 | 7.4 | 4.5 | 9.6 | |

| BR | 19.875 | −9.125 | 0 | 7.3 | 3.041 | 4.44 | 4.5 | 5.8 | ||

| left | HR | 92.375 | 61.375 | 1 | 74.8 | 6.056 | 5.96 | 5 | 8.2 | |

| BR | 31.25 | −18.75 | 0 | 7.9 | 6.509 | 6.5 | 7 | 8.5 | ||

| back | HR | 91.25 | 57.25 | 0 | 73.7 | 2.721 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.5 | |

| BR | 34.625 | −2.375 | 0 | 16.8 | 5.156 | 6.16 | 5 | 7.6 |

To summarize, the results statistically prove that the left and right orientations are unsuitable for monitoring HR and BR. The radar performed well for the front and back orientation. However, the maximum range for monitoring an individual should be restricted to 120 cm as the problem of missing data arises beyond this range.

3.3. Effect of Movements on Measurement

The radar was placed at multiple distances from the individual, who was made to walk on a treadmill at 4.8 kmph (lowest speed). After one observation, a 1 min resting period was taken, after which the radar recorded the HR and BR values for the same individual while standing. The process was continued for nine more observations. As shown in Table 5, boxes highlighted in orange and green are the best values obtained for HR and BR, respectively. Based on the statistical analysis, the following observations were made:

Range = 20 cm: The HR values while walking produced better results than standing as it generated no outliers and lesser standard deviation. While standing, the number of outliers, SD and MSE was lesser than that of values obtained when walking.

Range = 40 cm: In this case, for both BR and HR, it is quite clear that best results were obtained when the person was standing.

Range = 60 cm: Surprisingly, this range was observed to be the optimal distance for monitoring a moving person. The number of outliers was 0, and values were less skewed. Though BR values while walking had a higher deviation, it is important to note that the skewness value was almost negligible.

Table 5.

Statistical evaluation of effect of movement.

| Distance (cm) | Activity | Vital Sign | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Outliers | Mean | MSE | MAE | MedAE | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | standing | HR | 74.88 | 71.88 | 4 | 72 | 62.8 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 8.35 |

| BR | 10.5 | 6.5 | 1 | 9 | 1.04 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.07 | ||

| walking | HR | 85.5 | 59.5 | 0 | 73 | 14.6 | 3.48 | 3.5 | 4.03 | |

| BR | 28.88 | 3.875 | 2 | 18 | 52.3 | 5.68 | 4.4 | 7.62 | ||

| 40 | standing | HR | 77.5 | 65.5 | 0 | 72 | 6.56 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| BR | 16.13 | 3.125 | 1 | 11 | 18.6 | 3.32 | 2.8 | 4.54 | ||

| walking | HR | 74.5 | 62.5 | 2 | 70 | 23.7 | 3.36 | 2.1 | 5.13 | |

| BR | 34.5 | −3.5 | 0 | 17 | 49.6 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 7.42 | ||

| 60 | standing | HR | 88 | 64 | 2 | 74 | 38.4 | 4.84 | 4.2 | 6.53 |

| BR | 16.5 | 4.5 | 1 | 11 | 13.8 | 2.56 | 2 | 3.92 | ||

| walking | HR | 81.88 | 68.88 | 0 | 75 | 10.5 | 2.66 | 1.9 | 3.41 | |

| BR | 29.63 | 0.625 | 0 | 14 | 23 | 3.88 | 4.5 | 5.06 |

To summarize, we observed that the sensor could perform efficiently in generating low-skewed HR and BR values at a range of 60 cm when the person was moving. At range = 20 cm, results were inconclusive as one of the vital signs performed poorly for each activity. However, when patients moved to an optimum measuring distance of 40 cm, it became clear that individuals achieved better test results while standing without any movements as their MSE, MedAE, SD and skewness were lower.

3.3.1. Validating Heart Rate Values during Movement

To make the performance analysis clearer, the HR values measured while standing and walking were compared to our reference OMRON device as described in Table 6. Where, the orange background indicates best HR values. After taking HR values for both scenarios, 1 min of resting time was given followed by measurement using OMRON. Hence, all measurements were taken with equal amounts of resting time.

Table 6.

Performance analysis of heart rate with respect to Omron device.

| Distance | Activity | Vital Sign | Mean | MSE | MAE | medAE | SD | R Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | standing | HR | 72 | 97.61 | 7.72 | 4.9 | 8.353 | 0.285137 |

| walking | HR | 73 | 42.73 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 4.033 | 0.6193151 | |

| 40 | standing | HR | 72 | 43.77 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 0.833473 |

| walking | HR | 70 | 84.53 | 8.22 | 7.9 | 5.131 | 0.688605 | |

| 60 | standing | HR | 74 | 55.17 | 5.36 | 2.5 | 6.529 | 0.2274384 |

| walking | HR | 75 | 18.33 | 3.22 | 1.9 | 3.414 | 0.3641268 |

As discussed before, HR values for the 40 cm range performed as expected, and MSE, MAE, medAE and SD values were lower and hence better than OMRON. It is now clearly observed that walking produced better results for the 20 cm and 60 cm range, which was previously inconclusive. Furthermore, a higher coefficient of determination (R-squared) proves that the radar can detect HR values which better fit the regression line. Here, R-squared value refers to the percentage of variation in the OMRON device’s HR readings that the radar can collectively explain as defined in (18)

| (18) |

where is the residual sum of squared errors, is the total sum of squared errors, is a radar HR observation, is the corresponding OMRON reading, and is the mean of all radar observations.

3.3.2. Validating Breathing Rate Values

Table 7 clearly concludes that BR values were best when a person was standing without making any movements for all distances measured in our experiment.

Table 7.

Performance analysis of breathing rate (with and without moving).

| Distance | Activity | Vital Sign | Mean | MSE | MAE | medAE | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | standing | BR | 9 | 1.04 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.07497 |

| walking | BR | 18 | 52.29 | 5.68 | 4.4 | 7.62234 | |

| 40 | standing | BR | 11 | 18.56 | 3.32 | 2.8 | 4.54117 |

| walking | BR | 17 | 49.6 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 7.42369 | |

| 60 | standing | BR | 11 | 13.81 | 2.56 | 2 | 3.9172 |

| walking | BR | 14 | 23.04 | 3.88 | 4.5 | 5.05964 |

Hence, Table 6 and Table 7 show that HR values recorded during movements had better correlation with the reference device while BR values had large deviations from the mean. Since our radar measurement system only measures phase change within the same range bin, it is possible that bodily movements induced a change in the phase along the fast-time axis. Hence, phase changes due to breathing chest displacements (0.1–0.6 Hz) was easily discarded as noise.

3.4. Signal Processing and Arrhythmia Detection

3.4.1. ECG Signal Processing

The MIT-BIH normal sinus dataset [33] consists of 18 single-lead ECG recordings, which includes five men between the age of 26 and 45 and women between 20 and 50. The MIT-BIH arrhythmia dataset [34] consists of two-lead ECG recordings of 47 subjects. Of the 47 readings, 15 readings were selected for training the ANN model. Both sets of signals were 10 s long, and each sample was subtracted by the baseline, whose result was divided by the gain. The signal specifications of the generated dataset are outlined in Table 8. Outputs of the signal processing steps as described in the previous section are plotted in Figure 6.

Table 8.

ECG signal specifications of the training dataset.

| Specifications | Normal Sinus Dataset | Arrhythmia Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling frequency (Hz) | 128 | 360 |

| Number of samples | 1280 | 3600 |

| Gain (adu/mV) | 200 | 200 |

| Baseline | 0 | 1024 |

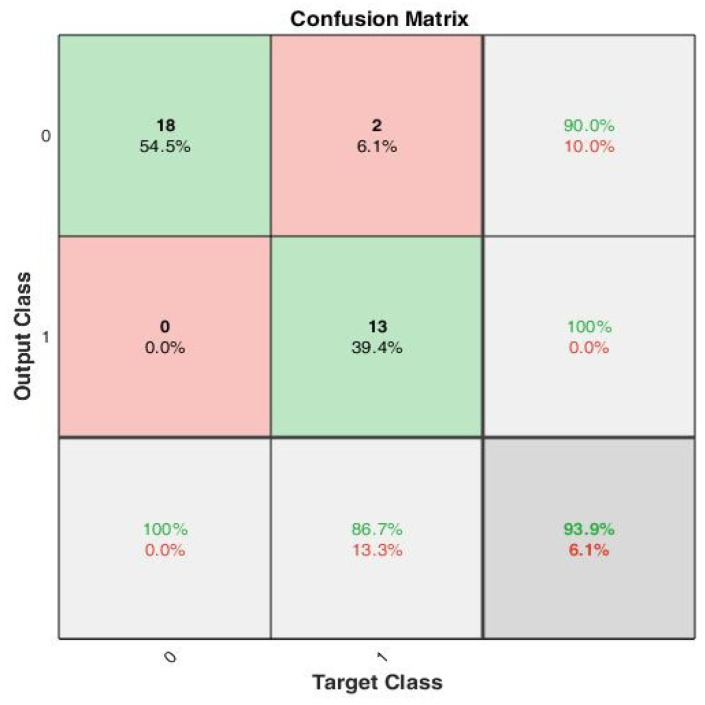

The peak-to-peak interval-based features were estimated using (13)–(17) to create the training set, which consists of 33 training examples. The data are split 70–30, i.e., 70% training, 15% validation and 15% test data for 10 epochs. The confusion plot in Figure 8 reveals that out of the 33 training examples, 18 were true negatives (TN), 2 false positives (FP), 13 true positives (TP) and 0 false negatives (FN).

Figure 8.

A confusion matrix that summarizes the model performance with true positivity rate and true negativity rate, with accuracy of 100%, 90% and 93.9%, respectively.

Figure 9 depicts the gradual minimization of mean square error (MSE) during training. It was found that at the third epoch, MSE was minimized to 0.025 during validation. Figure 10 shows that the gradient value gradually decreased to nearly 0 at epoch nine, which signifies that the weights cannot be trained further.

Figure 9.

The mean squared error during training reduced to a very low value at the 9th epoch. However, with early stopping enabled, the best performance was obtained at the 3rd epoch when the validation MSE = 0.025.

Figure 10.

Gradient optimization using gradient descent and momentum.

The value (momentum) was reduced gradually to adaptively decrease the value of the gradient. To prevent the model from gradient overshooting, the momentum should reduce the rate at which the gradient value decreases when the MSE is approaching local minima.

3.4.2. Radar Heartbeat Signal Processing

The periodogram in Figure 11 signifies that the signal consisted of components in the frequency range 0.6–2 Hz.

Figure 11.

Periodogram of input heartbeat phase signal.

However, the exact frequency at which the maximum power was estimated was unclear. Since our training dataset was formed based on-RR interval-based features only and the R peak amplitudes, while modelling our radar signal (as described in Section 2), we can simply set each phase value equal to its mean. Hence, only the time duration of each peak phase value was extracted.

A total of 100,000 data samples were utilized to model each triangular wave component. For the input radar signal as shown in Figure 12, n peaks were detected; hence, there were 100,000 × n data samples. Therefore, the sampling frequency was set as . The signal was then down sampled to the desired sampling frequency, Fs = 5 Hz. The periodogram of the modelled signal as shown in Figure 13 clearly shows that the power spectral density (PSD) lay at frequency = 1.133 Hz, which lies within the expected frequency range of a heartbeat phase signal, i.e., 0.8–2 Hz. Hence, a well-constructed signal was generated whose peak values can be easily detected for testing the trained arrhythmia detection model.

Figure 12.

Signal reconstruction using symmetric triangular wave function, which was then down sampled to 5 Hz to match the sampling frequency of the ECG signals used in the training dataset.

Figure 13.

Periodogram of reconstructed phase signal shows that maximal power spectral density (PSD) lies in the frequency = 1.133 Hz.

In addition to the result obtained in Figure 14, a considerable improvement in the SNR value from −0.1 dB to 8.72 dB can be observed in Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Signal-to-noise ratio (a) SNR of input signal, (b) SNR of reconstructed signal using symmetrical triangular QRS wave function.

3.4.3. Arrhythmia Detection Test

The trained neural network model was tested on unseen data generated by eight individuals. For every subject, 10 sets of observations were taken from the radar, and further peak-interval-based statistical features were extracted. The results are summarized in Table 9. However, it is important to note that our experiments were limited to testing only healthy individuals. The remaining seven subjects were tested on unseen ECG data from the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database.

Table 9.

Testing accuracies of 15 subjects: the average test accuracy was estimated to be 75% for 15 subjects. The coefficient of determination of 0.876 for the trained dataset is justified.

| Subject ID | Age | Gender | Testing Accuracy |

Predicted | Actual | False Positives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | male | 60% | Normal | Normal | 4 |

| 2 | 24 | male | 90% | Normal | Normal | 1 |

| 3 | 23 | male | 60% | Normal | Normal | 4 |

| 4 | 30 | female | 80% | Normal | Normal | 2 |

| 5 | 20 | male | 100% | Normal | Normal | 0 |

| 6 | 25 | male | 60% | Normal | Normal | 4 |

| 7 | 50 | female | 90% | Normal | Normal | 1 |

| 8 | 45 | female | 100% | Normal | Normal | 0 |

| 9 | 68 | male | 60% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 4 |

| 10 | 69 | male | 80% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 2 |

| 11 | 69 | male | 70% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 3 |

| 12 | 51 | female | 20% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 8 |

| 13 | 83 | female | 80% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 2 |

| 14 | 51 | male | 80% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 2 |

| 15 | 63 | female | 90% | Arrhythmia | Arrhythmia | 1 |

4. Conclusions

An mm-wave FMCW radar-based non-contact vital signs monitoring system was implemented that continuously monitors the heart and respiratory rate. Based on the experiments carried out using the system, it was found that HR values estimated by the radar only deviated from our reference device by 4. The effect of orientation and distance was statistically analysed (using number of outliers, SD, MSE and skewness) based on HR and BR values, and conclusive results show that right and left orientations were unsuitable for monitoring and the distance of measurement should be restricted to 120 cm. Furthermore, experiments on the effect of movement interestingly revealed that the HR recorded while walking had a better overall performance (in terms of MSE, SD, R-squared) than those recorded while the individual was stationary with respect to the reference device. However, standing in a stationary position is more favourable while recording breathing rates. To improve the overall reliability of arrhythmia detection, the heartbeat signal was rectified by representing them as triangular wave functions using Fourier series expansions. The resulting signals of the improved SNR value was then utilized to test an ECG-trained neural network model whose training features are statistical metrics based on RR-interval values. A 75% mean test accuracy was obtained for 15 observations that classify whether the heartbeat signals from a test subject were positively or negatively cardiac arrhythmic.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted the at Singtel Cognitive and Artificial Intelligence Lab for Enterprises (SCALE@NTU), which is a collaboration between Singapore Telecommunications Limited (Singtel) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I. and M.F.K.; validation, S.I.; formal analysis, M.P.M.; investigation, J.J., A.A. and M.F.K.; data curation, S.I. and M.P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.; writing—review and editing, L.Z., M.Y.S. and M.F.K..; visualization, M.P.M.; supervision, L.Z., J.J., M.Y.S., A.A. and M.F.K.; project administration, M.F.K.; funding acquisition, M.F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the RIE2020 Industry Alignment Fund—Industry Collaboration Projects (IAF-ICP) Funding Initiative, as well as cash and in-kind contributions from Singapore Telecommunications Limited (Singtel), through Singtel Cognitive and Artificial Intelligence Lab for Enterprises (SCALE@NTU).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not needed for this study, as: “This is a non-invasive experiment with very low power which is not harmful to humans”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The normal sinus and arrhythmia datasets were taken from the open-source MIT-BIH repository from https://archive.physionet.org/physiobank/database/nsrdb/ (accessed on 1 November 2019) and https://physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 1 November 2019), respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Prgomet M., Cardona-Morrell M., Nicholson M., Lake R., Long J., Westbrook J., Braithwaite J., Hillman K. Vital signs monitoring on general wards: Clinical staff perceptions of current practices and the planned introduction of continuous monitoring technology. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2016;28:515–521. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burch V.C., Tarr G., Morroni C. Modified early warning score predicts the need for hospital admission and inhospital mortality. Emerg. Med. J. 2008;25:674–678. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.057661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weenk M., van Goor H., Frietman B., Engelen L.J., van Laarhoven C.J., Smit J., Bredie S.J., van de Belt T.H. Continuous Monitoring of Vital Signs Using Wearable Devices on the General Ward: Pilot Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5:e91. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villarroel M., Guazzi A., Jorge J., Davis S., Watkinson P., Green G., Shenvi A., McCormick K., Tarassenko L. Continuous non-contact vital sign monitoring in neonatal intensive care unit. Health Technol. Lett. 2014;1:87–91. doi: 10.1049/htl.2014.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsburg A.S., Lenahan J.L., Izadnegahdar R., Ansermino J.M. A Systematic Review of Tools to Measure Respiratory Rate in Order to Identify Childhood Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:1116–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2233CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv Q., Chen L., An K., Wang J., Li H., Ye D., Huangfu J., Li C., Ran L. Doppler Vital Signs Detection in the Presence of Large-Scale Random Body Movements. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2018;66:4261–4270. doi: 10.1109/TMTT.2018.2852625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Droitcour A., Lubecke V., Lin J., Boric-Lubecke O. A microwave radio for Doppler radar sensing of vital signs; Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Sympsoium Digest (Cat. No.01CH37157); Phoenix, AZ, USA. 20–24 May 2001; pp. 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubecke O., Ong P.-W., Lubecke V. 10 GHz Doppler radar sensing of respiration and heart movement; Proceedings of the IEEE 28th Annual Northeast Bioengineering Conference (IEEE Cat. No. 02CH37342); Philadelphia, PA, USA. 21 April 2002; pp. 55–56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J., Wang X., Chen L., Huangfu J., Li C., Ran L. Noncontact Distance and Amplitude-Independent Vibration Measurement Based on an Extended DACM Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014;63:145–153. doi: 10.1109/TIM.2013.2277530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu W., Zhao Z., Wang Y., Zhang H., Lin F. Noncontact Accurate Measurement of Cardiopulmonary Activity Using a Compact Quadrature Doppler Radar Sensor. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013;61:725–735. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2288319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu J., Lin J. Fast Acquisition of Heart Rate in Noncontact Vital Sign Radar Measurement Using Time-Window-Variation Technique. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015;65:112–122. doi: 10.1109/TIM.2015.2479103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schires E., Georgiou P., Lande T.S. Vital Sign Monitoring Through the Back Using an UWB Impulse Radar With Body Coupled Antennas. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2018;12:292–302. doi: 10.1109/TBCAS.2018.2799322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y., Park J.-Y., Choi Y.-W., Park H.-K., Cho S.H., Cho S.H., Lim Y.-H. A Novel Non-contact Heart Rate Monitor Using Impulse-Radio Ultra-Wideband (IR-UWB) Radar Technology. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31411-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang G., Munoz-Ferreras J.-M., Gu C., Li C., Gomez-Garcia R. Application of Linear-Frequency-Modulated Continuous-Wave (LFMCW) Radars for Tracking of Vital Signs. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2014;62:1387–1399. doi: 10.1109/TMTT.2014.2320464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S., Pohl A., Jaeschke T., Czaplik M., Kony M., Leonhardt S., Pohl N. A novel ultra-wideband 80 GHz FMCW radar system for contactless monitoring of vital signs; Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); Milan, Italy. 25–29 August 2015; pp. 4978–4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He M., Nian Y., Gong Y. Novel signal processing method for vital sign monitoring using FMCW radar. Biomed. Signal Proc. Control. 2017;33:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2016.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad A., Roh J.C., Wang D., Dubey A. Vital signs monitoring of multiple people using a FMCW millimeter-wave sensor; Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Radar Conference; Oklahoma City, OK, USA. 23–27 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazaro A., Girbau D., Villarino R. Analysis of vital signs monitoring using an IR-UWB radar. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 2010;100:265–284. doi: 10.2528/PIER09120302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schleicher B., Nasr I., Trasser A., Schumacher H. IR-UWB radar demonstrator for ultra-fine movement detection and vital-sign monitoring. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2013;61:2076–2085. doi: 10.1109/TMTT.2013.2252185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X., Yin W., Li L., Zhang L. Dense People Counting Using IR-UWB Radar With a Hybrid Feature Extraction Method. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018;16:30–34. doi: 10.1109/LGRS.2018.2869287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang X., Zhang H., Ye S., Fang G., Aaron Gulliver T. Improved Denoising Method for Through-Wall VitalSign Detection Using UWB Impulse Radar. Digit. Signal Process. 2018;74:72–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dsp.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana S.P., Dey M., Ghavami M., Dudley S. Signature Inspired Home Environments Monitoring System Using IR-UWB Technology. Sensors. 2019;19:385. doi: 10.3390/s19020385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P., Zhang Y., Ma Y., Liang F., An Q., Xue H., Yu X., Lv H., Wang J. Method for Distinguishing Humans and Animals in Vital Signs Monitoring Using IR-UWB Radar. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:4462. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D., Yoo S., Cho S.H. Experimental Comparison of IR-UWB Radar and FMCW Radar for Vital Signs. Sensors. 2020;20:6695. doi: 10.3390/s20226695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto T., Imasaka R., Taki H., Sato T., Yoshioka M., Inoue K., Fukuda T., Sakai H. Feature-based Correlation and Topological Similarity for Interbeat Interval Estimation using Ultra-Wideband Radar. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015;63:747–757. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2470077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu C. Short-Range Noncontact Sensors for Healthcare and Other Emerging Applications: A Review. Sensors. 2016;16:1169. doi: 10.3390/s16081169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabriel S., Lau R.W., Gabriel C. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: II. Measurements in the frequency range 10 Hz to 20 GHz. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996;41:2251–2269. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/41/11/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Electromagnetic Fields and Public Health: Radars and Human Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. [(accessed on 1 January 2020)]. Available online: https://www.jeic-emf.jp/assets/files/Fact%20Sheets/facrt_sheet_226.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh M., Shaker G., De Almeida J.C.M., Morita P.P., Safavi-Naeini S. Remote Monitoring of Human Vital Signs Using mm-Wave FMCW Radar. IEEE Access. 2019;7:54958–54968. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2912956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alizadeh M., Shaker G., Safavi-Naeini S. Experimental study on the phase analysis of FMCW radar for vital signs detection; Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP); Krakow, Poland. 31 March–5 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villar R., Beltrame T.B., Hughson R.L. Validation of the Hexoskin wearable vest during lying, sitting, standing, and walking activities. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015;40:1019–1024. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Budge M., Burt M. Range correlation effects in radars; Proceedings of the The Record of the 1993 IEEE National Radar Conference; Lynnfield, MA, USA. 20–22 April 1993; pp. 212–216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberger A., Amaral L., Glass L., Hausdorff J., Ivanov P.C., Mark R., Stanley H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2020;101:e215–e220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moody G.B., Mark R.G. The impact of the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2001;20:45–50. doi: 10.1109/51.932724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The normal sinus and arrhythmia datasets were taken from the open-source MIT-BIH repository from https://archive.physionet.org/physiobank/database/nsrdb/ (accessed on 1 November 2019) and https://physionet.org/content/mitdb/1.0.0/ (accessed on 1 November 2019), respectively.