Abstract

The growth modulating effects of the ovarian steroid hormones 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (PRG) on endocrine-responsive target tissues are well established. In hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer, E2 functions as a potent growth promoter, while the function of PRG is less defined. In the hormone-receptor-positive Luminal A and Luminal B molecular subtypes of clinical breast cancer, conventional endocrine therapy predominantly targets estrogen receptor function and estrogen biosynthesis and/or growth factor receptors. These therapeutic options are associated with systemic toxicity, acquired tumor resistance, and the emergence of drug-resistant cancer stem cells, facilitating the progression of therapy-resistant disease. The limitations of targeted endocrine therapy emphasize the identification of nontoxic testable alternatives. In the human breast, carcinoma-derived hormone-receptor-positive MCF-7 model treatment with E2 within the physiological concentration range of 1 nM to 20 nM induces progressive growth, upregulated cell cycle progression, and downregulated cellular apoptosis. In contrast, treatment with PRG at the equimolar concentration range exhibits dose-dependent growth inhibition, downregulated cell-cycle progression, and upregulated cellular apoptosis. Nontoxic nutritional herbs at their respective maximum cytostatic concentrations (IC90) effectively increase the E2 metabolite ratio in favor of the anti-proliferative metabolite. The long-term exposure to the selective estrogen-receptor modulator tamoxifen selects a drug-resistant phenotype, exhibiting increased expressions of stem cell markers. The present review discusses the published evidence relevant to hormone metabolism, growth modulation by hormone metabolites, drug-resistant stem cells, and growth-inhibitory efficacy of nutritional herbs. Collectively, this evidence provides proof of the concept for future research directions that are focused on novel therapeutic options for endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer that may operate via E2- and/or PRG-mediated growth regulation.

Keywords: breast carcinoma, steroid hormone metabolism, cancer stem cells, natural products

1. Introduction

In the development of breast cancer, the ovarian steroid hormones 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (PRG) represent important growth-regulatory hormones [1]. Although the growth-promoting effects of E2 are well-established, the cellular effects of PRG are divergent and mostly context dependent. The receptors for both these hormones function as ligand-regulated nuclear transcription factors that bind to specific DNA response elements and operate via co-activators and co-repressors to affect the transcriptional modulation of down-stream target genes. The critical molecular processes responsible for the cellular effects of E2 and PRG include complex autocrine and paracrine pathways involving specific cell-cycle regulators and NFkB-mediated growth modulation. Thus, two steroid hormones effectively interact via well-defined molecular cross-talk to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and breast carcinogenesis [2,3,4]. The molecular interaction of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) signaling in hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer results in a modulatory effect of PR on the action of ER to attenuate tumor growth via multiple pathways. In addition to ER- and PR-mediated signaling, the receptor-independent cellular metabolism of these hormones generates metabolites with distinct cellular effects relevant to the process of carcinogenesis [5,6,7,8].

The hormone-receptor-positive Luminal A and Luminal B molecular subtypes of clinical breast cancer respond to selective estrogen-receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors, and to HER-2 targeted therapeutics. However, long-term anti-estrogen therapy and human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER-2)-based targeted therapy is associated with intrinsic and/or acquired drug resistance that compromises the therapeutic efficacy and favors progression of therapy-resistant disease. The progression of therapy-resistant disease is frequently associated with the emergence of drug-resistant stem cell populations [9]. These limitations of current therapy for breast cancer emphasize an unmet need to identify stem cell targeting testable alternatives. Drug-resistant stem cell models have been developed for HER-2-enriched and triple-negative breast cancer subtypes [10,11].

The expression status of select hormone and growth-factor receptors has provided a basis for the clinically relevant classification of the cellular models for breast cancer subtypes [12,13]. Furthermore, stable expressions of the clinically relevant HER-2 oncogene [14,15,16] or the gene for aromatase enzyme [17,18] have provided valuable models to examine the role of oncogenes and estrogens in breast cancer.

The human mammary carcinoma-derived MCF-7 cell line that is ER/PR positive and expresses non-amplified HER-2, represents a model for the Luminal A molecular subtype of clinical breast cancer [12,13]. Several mechanistically distinct Chinese nutritional herbs have documented preferential growth-inhibitory efficacy in the isogenic MCF-7 phenotypes that exhibit a modulated ER-α function [19]. However, little evidence is available on the effects of nutritional herbs, either on PRG activity or function. Based on the evidence of negative growth regulation by PRG, the potential therapeutic utility of progestogens and progesterone receptor (PR) agonists may represent beneficial treatment options. It is conceivable that the non-toxic nutritional herbs may also be effective in the hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer via PR function.

The goal of the present review is to provide (i) a systematic discussion of the published literature relevant to the development and characterization of the MCF-7 model; (ii) mechanistic leads for the significance of anti-proliferative metabolites of E2 and PRG; and (iii) growth-inhibitory efficacy of dietary phytochemicals and nutritional herbs as stem-cell-targeting testable alternatives for the chemo-endocrine therapy-resistant Luminal A molecular subtype of breast cancer.

2. Cellular Models

In the mouse mammary gland organ culture model, the ovarian steroid hormones E2 and PRG are critical for the induction of normal ductal morphogenesis. Lactogenic hormones, prolactin and hydrocortisone, induce lobulo-alveolar growth and mammary-specific differentiation [20]. In response to treatment with chemical carcinogens, the mammary gland organ cultures develop lactogenic hormone-independent pre-neoplastic alveolar lesions [21], and the transplantation of cells from 7–12 dimethyl benzanthracene (DMBA)-induced alveolar lesions produce rapidly growing tumors [22]. However, the impact of similar interactions between steroid and polypeptide hormones on the initiation or progression of human mammary carcinogenesis remains to be fully elucidated.

Global gene-expression profiling of clinical breast cancer has facilitated the molecular classification of breast cancer subtypes [23]. Cellular models developed from human breast carcinoma-derived cell lines continue to represent valuable resources to identify clinically relevant mechanistic pathways and molecular targets for therapeutic efficacy [12,13].

MCF-7 cells expressing mutant HER-2 represent an additional model for the Luminal B breast cancer subtype [14]. The CYP19 A1 aromatase enzyme is critical for peripheral and intra-tumoral estrogen biosynthesis. This enzyme converts adrenal androstenedione to estrone (E1) and testosterone to E2. E1 is converted to E2 by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [5,6]. MCF-7 cells expressing the aromatase gene represent a model for aromatase-positive post-menopausal breast cancer [17,18]. Furthermore, the stable expression of the HER-2 oncogene in human mammary epithelial 184-B5 cells induces tumorigenic transformation [15,16]. The 184-B5/HER cell line represents a valuable model to examine the role of the HER-2 oncogene in the initiation and progression of human breast cancer.

Collectively, the molecular characteristics of various cellular models provide relevant quantitative end-point parameters for the preventive/therapeutic efficacy of dietary phytochemicals and nutritional herbs directly on the target cells of breast cancer. The data on the characteristics of clinically relevant cellular models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cellular models for breast cancer subtypes.

| Model | Receptor Status | Subtype | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | PR | HER-2 | |||

| MCF-7 | + | + | − | Luminal A | [12,13] |

| T47D | + | + | − | Luminal A | [12,13] |

| BT474 | + | + | + | Luminal B | [12,13] |

| MDA-MB-361 | + | + | + | Luminal B | [12,13] |

| MCF-7 HER | + | + | + | Luminal B | [14] |

| MCF-7AROM | + | + | − | Aromatase positive | [15,16] |

| SKBr-3 | − | − | + | HER-2 enriched | [12,13] |

| 184-B5/HER | − | − | + | HER-2 enriched | [17,18] |

| MDA-MB-231 | − | − | − | Triple negative | [12,13] |

ER, estrogen receptor-α; PR, progesterone receptor; and HER-2, human epidermal growth-factor receptor-2.

2.1. The Growth Characteristics of the MCF-7 Model

Carcinoma-derived cell lines commonly exhibit hyper-proliferation and persistence anchorage-independent growth in vitro, and tumor formation in vivo. Table 2 compares the growth pattern of human breast epithelium-derived non-tumorigenic 184-B5 cells and human breast carcinoma-derived tumorigenic MCF-7 cells. The MCF-7 cells exhibit hyper-proliferation, as evidenced by a decrease in the population doubling time, increase in the saturation density, and accelerated cell cycle progression. Additionally, MCF-7 cells exhibit downregulated cellular apoptosis, decreased estrogen metabolite ratio, and a robust increase in anchorage-independent colony formation, the latter being a specific in vitro surrogate end point for in vivo tumor formation. These data suggest that MCF-7 cells exhibit a loss of homeostatic growth control and persistent cancer risk.

Table 2.

Growth pattern of the Luminal A MCF-7 model.

| End-Point Biomarker | Experimental Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 184-B5 | MCF-7 | Relative to 184-B5 | |

| Population doubling (h) | 34.0 ± 1.8 | 15.2 ± 0.9 | −55.3% |

| Saturation density (×105) | 22.3 ± 1.2 | 26.6 ± 1.7 | +19.3% |

| G1:S + G2/M ratio | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | −39.1% |

| Sub G0 population (%) | 14.8 ± 2.3 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | −81.1% |

| 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1 ratio | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | −93.7% |

| AI colonies | 0/18 | 18/18 | +100% |

184-B5, non-tumorigenic breast epithelial cells; MCF-7, tumorigenic breast carcinoma cells; 2-OHE1; 2-hydrroxyestrone; 16α-OHE1, 16α-hydroxyestrone; and AI, anchorage independent.

2.2. Growth Modulation by Estradiol and Progesterone

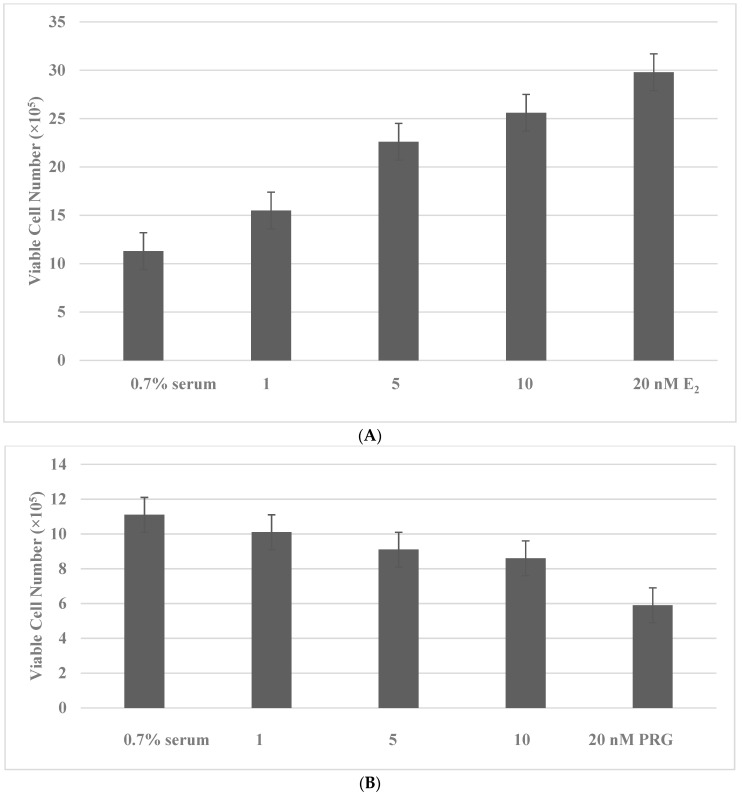

The distinct growth modulatory effects of E2 and PRG at the physiologically relevant concentrations were examined on MCF-7 cells maintained in a culture medium supplemented by 0.7% serum (serum concentration of E2 and PRG < 0.01 nM in the culture medium). Treatment with E2 at the physiological concentration range of 1 nM to 20 nM, resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in the viable cell number (Figure 1A). In contrast, treatment with PRG at the equimolar concentration range displayed a concentration-dependent decrease in the viable cell number (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Growth modulatory effects of E2 and PRG. (A): Treatment with E2 exhibits a dose-dependent increase in the viable cell number. (B): Treatment with PRG exhibits a dose-dependent decrease in the viable cell number. E2, 17β-estradiol; PRG, progesterone.

2.3. Cell Cycle Progression and Cellular Apoptosis

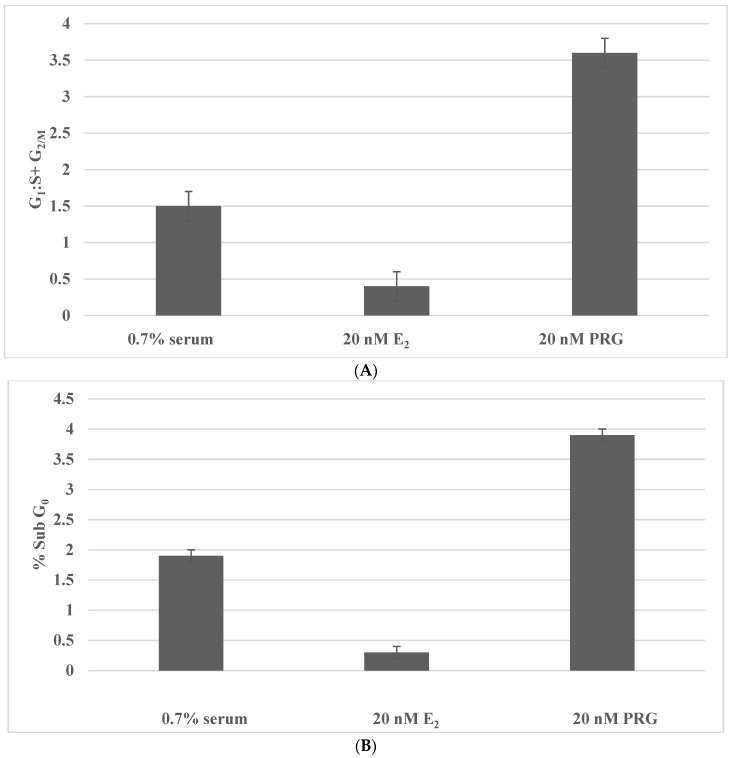

The data provided in Figure 2 provide evidence for the potential mechanistic leads that are responsible for the effects of E2 and PRG. As illustrated in Figure 2A, treatment with E2 decreases the G1:S + G2/M ratio due to an increase in the S phase of the cell cycle. In contrast, treatment with PRG increases the G1:S + G2/M ratio due to G1 arrest and a decrease in the S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. As illustrated in Figure 2B, treatment with E2 inhibits cellular apoptosis, while treatment with PRG increases cellular apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Effects of E2 and PRG on cell cycle progression and cellular apoptosis. (A): Treatment with 20 nM E2 inhibits the G1:S + G2/M ratio. Treatment with 20 nM PRG increases the G1:S + G2/M ratio. (B): Treatment with 20 nM E2 inhibits % SubG0 apoptotic cell population. Treatment with 20 nM PRG induces % Sub G0 apoptotic cell population. E2, 17β-estradiol; PRG, progesterone.

ER and PR belong to a superfamily of ligand-regulated nuclear transcription factors that are responsible for the expression of cognate downstream target genes. These genes include pS2, GRB2, and cyclin D1 for E2 [3,24], and a receptor activator of nuclear factor kB (RANK) and its ligand RANK-L for PRG [2,3,4]. In addition to the genomic mechanisms, the cellular metabolism of E2 and PRG plays a significant modulatory role in breast carcinogenesis. For example, the metabolites generated from E2 and PRG have documented divergent growth-modulatory effects on breast cancer cells.

3. Hormone Metabolism

3.1. Cellular Metabolism of Estradiol

The CYP450-mediated enzymatic metabolism of E2 generates mechanistically distinct metabolites that exert specific biological effects on the non-tumorigenic or tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells. During E2 metabolism, 4-hydroxylated E2 and 16α-hydroxylated E1 function as proliferative agents, while 2-hydroxylated E2 and 2-hydroxyalted E1 function as anti-proliferative agents [5,6]. These metabolites, because of their distinct biological effects, alter the ratio of anti-proliferative to proliferative metabolites. Similar metabolic alterations have also been documented in mammary epithelial cells that exhibit a tumorigenic transformation induced by stable transfection with Ras, Myc, and HER-2 oncogenes [25,26,27]. Thus, the altered 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1 ratio may represent a novel experimentally modifiable endocrine biomarker for the efficacy of testable alternatives for breast cancer prevention/therapy.

The published data supports the concept that genotoxic E2 metabolites 4-hydroxy estradiol (4-OHE2), 2-hydroxy estradiol (2-OHE2), and 16α-hydroxy estradiol (16α-OHE2) induce neoplastic transformation in the non-tumorigenic human mammary epithelial MCF-10F model [5]. In the hormone responsive MCF-7 model, E2 has been documented to generate genotoxic adenine and guanine DNA adducts, leading to error-prone DNA repair and/or DNA mutations; and, in the hormone responsive T47D model, 16α-hydroxylated metabolite and 2-hyrdroxylated metabolite of E2 exhibit estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activities, respectively [6,28]. Furthermore, it is also notable that the E2 metabolite 16α-OHE1 induces DNA damage and repair and transformation in non-tumorigenic C57MG cells, while 2-OHE1 fails to induce these genotoxic effects [29]. In the MCF-7 model, 16α-OHE1 enhances, while 2-OHE1 inhibits in vivo tumor growth [30]. Thus, in addition to ER-α-dependent growth-promoting effects on breast cancer cells, genotoxic E2 metabolites may function as initiators of carcinogenesis.

Because of the distinct effects of hydroxylated metabolites of E1, a ratio of these metabolites may represent a valuable end-point marker. Table 3 compares the status of the 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1 ratio in cellular models for breast cancer that differ in their relative risk for cancer development. These data demonstrate that, depending on the relative risk of developing cancer, the estrogen metabolite ratios are substantially decreased.

Table 3.

Status of the estrogen metabolite ratio.

| Model | Relative Cancer Risk | 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1

Ratio |

Relative to Low Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| TDLU reduction mammoplasty |

Low | 4.8 ± 0.6 | - |

| TDLU breast cancer |

High | 0.3 ± 0.1 | −93.7% |

| 184-B5 breast epithelial cells |

Low | 6.4 ± 0.8 | - |

| 184-B5/HER HER-2 positive |

High | 0.6 ± 0.3 | −90.6% |

| MCF-7 breast carcinoma |

High | 0.3 ± 0.1 | −95.3% |

| MMEC mouse mammary epithelial Cells |

Low | 2.2 ± 0.3 | - |

| MMEC-Ras Ras positive |

High | 0.2 ± 0.1 | −90.9% |

| MMEC-Myc Myc positive |

High | 0.3 ± 0.1 | −86.4% |

TDLU, terminal duct lobular unit; HER-2, human epidermal growth-factor receptor-2; 2-OHE1, 2-hydroxyestrone; and 16α-OHE1, 16α-hydroxyestrone.

3.2. The Cellular Metabolism of Progesterone

During PRG metabolism, 5α-hydroxylated metabolite functions as a proliferative agent, while 3α-hydroxylated metabolite functions as an anti-proliferative agent [7,8]. Thus, in the tumorigenic cells, the ratio of anti-proliferative:proliferative metabolites of PRG is altered in favor of the proliferative metabolites.

Similar to the E2 metabolites, PRG metabolites 5α-dihydro progesterone (5α-PRG) and 3α-dihydro progesterone (3α-PRG) have documented growth-modulatory divergent effects in the MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T47D, and MCF-10A models. At the mechanistic levels, growth promotion by the 5α metabolite is associated with increased DNA synthesis and the mitotic index and the downregulation of apoptosis, while growth inhibition by the 3α metabolite is associated with a decrease in these end points [7,31,32]. The growth modulating effects of PRG metabolites have also been documented in vivo in the tumors produced by transplanted MDA-MB-231 cells. [8].

The divergent effects of E2 and PRG have been documented in T47D, ZR75-1, and MCF-7 cells. For example, the E2-mediated inhibition of cellular apoptosis is associated with the increased expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2. In contrast, the PRG-mediated induction of cellular apoptosis is associated with the decreased BCL-2: BAX ratio, predominantly due to the increased expression of pro-apoptotic BAX [7]. In tissue explants of ER-positive tumors, E2 increases, while PRG decreases, cell proliferative activity [32,33].

The autocrine growth-modulatory effects of PRG involve the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p18 and p27 [34], and the modulation of ER-α and RNA polymerase III [35]. In addition to these autocrine effects, the paracrine cellular effects of PRG involve the NFkB pathway via modulation in the expression of RANK and its ligand RANKL [36], and the downregulated select interferon-stimulated genes [37]. Since E2 metabolites 4-OHE2 and 2-OHE2, E1 metabolites 16α-OHE1 and 2-OHE1, and PRG metabolites 5α-PRG and 3α-PRG exhibit opposing growth-regulatory effects, molecular/metabolic pathways for E2 and the PRG function may provide potential mechanistic leads responsible for E2- and PRG-mediated growth modulation.

Collectively, the evidence for the enzymatic conversion of E2 and PRG that generate metabolites with divergent growth-modulatory effects supports the significance of the ratio of proliferative and anti-proliferative metabolites. Thus, the experimental upregulation of anti-proliferative metabolites may provide mechanistic leads for novel therapeutic interventions.

4. Efficacy of Natural Products

Dietary phytochemicals, including gluco-brassinins, polyphenols, isoflavones, and terpepnoids induce cell cycle arrest via G1 phase arrest, inhibit pHER-2 expression, induce cellular apoptosis, modulate the expressions of apoptosis-specific BCL-2 and BAX, and alter the cellular metabolism of E2 in cellular models for breast cancer [38,39,40,41,42]. Mechanistically distinct Chinese nutritional herbs Cornus officinalis (CO), Psoralea corylifolia (PC), and Dipsacus apsperoides (DA) function as effective growth-inhibitory agents in MDA-MB-231 cells, a cellular model for triple-negative breast cancer [42,43,44,45].

The published data on inhibitory efficacy Chinese nutritional herbs Epimedium grandiflorum (EG), Lycium barbarum (LB), and Cornus officinalis (CO) on MCF-7 cells, a model for Luminal A breast cancer, provide mechanistic leads to identify nontoxic testable alternatives. The anti-proliferative effects of these herbs are associated with the altered cellular metabolism of E2 in favor of the formation of the non-proliferative metabolite 2-OHE1 [46,47,48].

The data provided in Table 4 illustrates that treatment with CO, EG, and LB induces the upregulation of the 2-hydroxylation pathway, leading to an increase in 2-OHE1 formation and the downregulation of the 16α-hydroxylation pathway leading to a decrease in the 16α-OHE1 formation.

Table 4.

Altered metabolism of 17β-estradiol by nutritional herbs.

| Treatment | Source | Concentration | 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1 Ratio | Relative to E2 Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 control | 20 nM | 0.4 ± 0.2 | - | |

| E2 + EG | Leaf/stem | 20 nM + 9.0 µg/mL | 1.9 ± 0.2 | +3.7x |

| E2 + LB | Bark | 20 nM + 0.5 µg/mL | 5.2 ± 0.7 | +12.0x |

| E2 + CO | Fruit | 20 nM + 5.0 µg/mL | 6.8 ± 0.8 | +16.0x |

2-OHE1, 2-hydroxyestrone; 16α-OHE1, 16α-hydroxyestrone; E2, 17β-estradiol; EG, Epimedium grandiflorum; LB, Lycium barbarum; and CO, Cornus officinalis.

The CYP19 A1 Aromatase enzyme represents a critical enzyme for peripheral and intra-tumoral estrogen biosynthesis in post-menopausal breast cancer, and thereby provides growth-promoting estrogens via the conversion of E2 and E1 from testosterone and androstenedione, respectively [49,50]. In this context, it is notable that the progesterone metabolite 20α-DHP, predominantly detected in normal breasts, functions as a potent inhibitor of aromatase [51]. An extract from the inner bark of the South American Tabebuia avellanedae (TA) tree displays pro-apoptotic and anti-aromatase activity in the MCF-7 AROM model for aromatase expressing post-menopausal breast cancer. In this model, the TA-mediated induction of cellular apoptosis is associated with the upregulated expression of the pro-apoptotic BAX gene and downregulated expression of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 gene. Treatment with TA is also associated with downregulated expressions of several E2 responsive genes, such as ESR-1, AORM, PR, PS2, GRB2, and cyclin D1. The potency of aromatase inhibition by TA, based on the content of the active agent naphthofuran dione, is substantially higher than the pharmacological inhibitors of aromatase, letrozole, and exemestane [52]. Collectively, these data on aromatase inhibition provide evidence for aromatase as a potential target for experimental modulation.

5. Drug-Resistant Stem Cells

Stem cells are responsible for preserving the regulated program of epithelial proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, which are critical for cellular homeostasis in normal breasts via Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and NFkB signaling pathways, wherein the interactive influence of E2 and PRG plays an important role [53]. In drug-resistant cancer stem cells, these signaling pathways are dysregulated, and RAS-, PI3K-, AKT-, and mTOR-mediated survival pathways are activated [9,54,55].

Acquired resistance to conventional chemo-endocrine therapy and molecularly targeted therapy results in the emergence of drug-resistant cancer stem cells. Reliable stem cell models provide valuable experimental approaches to identify stem cell targeting testable alternatives. The tamoxifen-resistant (TAM-R) stem cell model for Luminal A breast cancer, the lapatinib-resistant (LAP-R) stem cell model for HER-2-enriched breast cancer, and the doxorubicin-resistant (DOX-R) stem cell model for triple-negative breast cancer exhibit upregulated expressions of select stem cell markers [10]. These models may provide clinically relevant experimental approaches to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of stem-cell-targeting natural herbal products, including dietary phytochemicals and Chinese nutritional herbs.

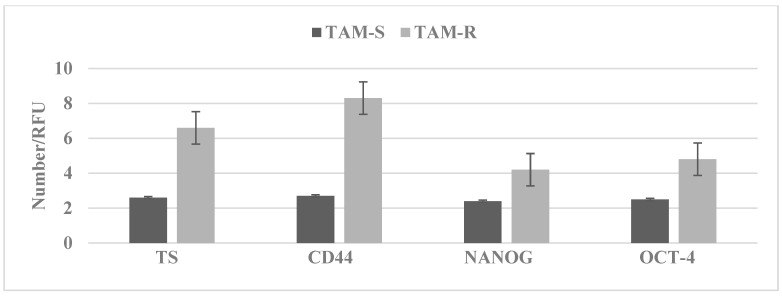

In the Luminal A molecular subtype of breast cancer selective estrogen-receptor modulator tamoxifen (TAM) has wide clinical applications. However, long-term treatment with TAM is associated with acquired tumor resistance. The data in Figure 3 illustrate that the tamoxifen-resistant stem cell model derived from MCF-7 cells exhibits an increased expression of select stem cell markers, such as TS, CD44, NANOG, and OCT-4.

Figure 3.

Stem cell marker expression in TAM-R cells. TAM-R cells exhibit increased expressions of TS, CD44, NANOG, and OCT-4 relative to the TAM-S cells. TAM-R, tamoxifen resistant; TAM-S, tamoxifen sensitive; TS, tumor spheroid number; CD44, cluster of differentiation; NANOG, DNA-binding transcription factor; OCT-4, octamer-binding transcription factor-4; and RFU, relative fluorescent unit.

This model may provide clinically relevant experimental approaches to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of natural herbal products targeted towards breast cancer stem cells.

6. Stem Cell Targeting Agents

In the LAP-R model for HER-2-enriched breast cancer, vitamin A derivative all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and a natural terpenoid carnosol (CSOL) downregulate stem cell markers [10]. In a model for TNBC, sulforaphane documented stem-cell-selective inhibitory efficacy [56] and benzyl isothio cyanate inhibits mammary stem-like cells functioning via the Klf-4/p21 CIP1 axis [57]. Additionally, Chinese medicines and their constitutive active components [58], dietary phytochemicals [59], and natural products [60,61] have been considered as potential stem-cell-targeting agents.

7. Conclusions

The present review discussed the published evidence relevant to the roles of E2 and PRG in breast cancer biology, the significance of reliable stem cell models for therapy-resistant breast cancer, and the mechanistic evidence for the growth-inhibitory efficacy of natural products, including dietary phytochemicals and nutritional herbs. Collectively, this review provides a proof concept that natural products may represent testable alternatives for therapy-resistant breast cancer.

A comprehensive overview of the conceptual background of the cellular models for Luminal A, Luminal B, and aromatase-expressing post-menopausal breast cancer subtypes, current targeted therapeutic options, therapy-resistant stem cells, naturally occurring dietary phytochemicals, and nutritional herbs as therapeutic alternatives for therapy-resistant breast cancer and future research directions are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overview: Luminal breast cancer.

| Targeted Therapy | Cellular Model | Therapeutic Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| SERM, SERD, AI, CDKI, HERI | Luminal A: HR+ HER-2−

MCF-7 Luminal B: HR+ HER-2+ MCF-7/HER Post-menopausal: aromatase positive MCF-7 AROM |

Natural phytochemicals nutritional herbs Documented human consumption Lack of detectable systemic toxicity |

| Systemic toxicity, acquired tumor resistance, drug-resistant stem cell population | Luminal B: HR+ HER-2+ MCF-7/HER Post-menopausal: aromatase positive MCF-7 AROM |

Inhibited proliferation. Increased 2-OHE1 |

| Proliferation: increased by E2 Decreased by PRG |

||

| E2 metabolites: proliferative metabolites increased, anti-proliferative metabolites decreased PRG metabolites: proliferative metabolites decreased, anti-proliferative metabolites increased |

||

| TAM-R stem cells: TS increased CD44, NANOG, and OCT-4 increased | ||

| Future directions: novel pharmacological inhibitors specific for RAS, PI3K, and AKT signaling pathways. Efficacy of small molecule inhibitors on developed stem cell models. Safety and efficacy in Phase 0 clinical trials | Future directions: stem cell models from therapy-resistant PDTX and PDTO. Cellular and molecular characterization of developed stem cell models |

Future directions: efficacy of natural phytochemicals and nutritional herbs on PDTX- and PDTO-derived stem cell models. |

Overview: Luminal Breast Cancer. This overview summarizes all the aspects that are discussed in the present review. SERM, selective estrogen-receptor modulator; SERD, selective estrogen-receptor degrader; AI, aromatase inhibitor; CDKI, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; HERI, human epidermal growth-factor receptor inhibitor; HR, hormone receptor; HER-2, human epidermal growth-factor receptor-2; HER, human epidermal-growth factor; AROM, aromatase; E2, 17β-estradiol; PRG, progesterone; 2-OHE1, 2-hydroxyestrone; TAM-R, tamoxifen resistant; TS, tumor spheroid; CD44; cluster of differentiation 44; NANOG, DNA-binding transcription factor; OCT-4, octamer-binding transcription factor-4; PI3K, phospho-inositidyl-3 kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; PDTX, patient-derived tumor xenograft; and PDTO, patient-derived tumor organoid.

8. Future Prospects

By extending the evidence provided in the present review, future research directions will involve patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDTX) and organoid (PDTO) models [62,63,64,65,66]. Additionally, future investigations will develop reliable stem cell models from therapy-resistant breast cancer subtypes. The outcome of these investigations on patient-derived samples is expected to provide strong evidence for clinically relevant data and their potential for clinical translation.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the productive collaborations and active participation of former colleagues from the Weill-Cornell Medical College of Cornell University, the Strang Cancer Prevention Center, and the American Foundation for Chinese medicine in the research program “Cellular models for molecular subtypes of clinical breast cancer: Molecular approaches for lead compound efficacy”. This review is dedicated to fond memories of Jack Fishman and Leon Bradlow who introduced me to hormonal carcinogenesis and molecular endocrinology and encouraged the relevant research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no competing interest.

Funding Statement

This research program has received initial research support from the US National Cancer Institute FIRST award (grant #CA 44741), the US Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program IDEA award (grant #DAMD-17-94-J-4208), the NCI Contract Research Master Agreement (grant #CN 75029-63), and philanthropic funds from the Strang Cancer Prevention Center.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.King R.J.B. Estrogen and progestin effects in human breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1993;27:3–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00683189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisken C. Progesterone signalling in breast cancer: A neglected hormone coming into the limelight. Nat. Cancer. 2013;13:385–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moy B., Goss P.E. Estrogen receptor pathway: Resistance to endocrine therapy and new therapeutic approaches. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:4790–4793. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll J., Hickey T., Tarulli G., Williams M., Tilley W. Deciphering the divergent roles of progestogens in breast cancer. Nat. Cancer. 2017;17:54–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo J., Russo I.H. The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;102:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santen R.J., Yue W., Wang J.-P. Estrogen metabolites and breast cancer. Steroids. 2015;99:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiebe J.P., Beausoleil M., Zhang G., Cialacu V. Opposing actions of the progesterone metabolites, 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-P) and 3α-dihydroprogesterone (3α-P) on mitosis, apoptosis and expression of BCL-2, BAX and p21 in human breast call lines. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;118:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiebe J.P., Zhang G., Welch I., Cadieux-Pitre H.-A.T. Progesterone metabolites regulate induction, growth, and suppression of estrogen- and progesterone receptor-negative human breast cell tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R38. doi: 10.1186/bcr3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey P., Rathod M., De A. Targeting stem cells in the realm of drug-resistant breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press) 2019;11:115–135. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S189224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telang N. Stem cell targeted therapeutic approaches for molecular subtypes of clinical breast cancer (Review) World Acad. Sci. J. 2019;1:20–24. doi: 10.3892/wasj.2018.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telang N. Targeting drug resistant stem cells in a human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-enrched breast cancer model. World Acad. Sci. J. 2019;1:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neve R.M., Chin K., Fridlyand J., Yeh J., Baehner F.L., Fevr T., Clark L., Bayani N., Coppe J.-P., Tong F., et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subik K., Lee J.-F., Baxter L., Strzepak T., Costello D., Crowley P., Xing L., Hung M.-C., Bonfiglio T., Hicks D.G., et al. The expression patterns of ER, PR, HER-2, CK5/6, EGFR, Ki 67 and AR by immuno-histochemical analysis in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2010;4:35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croessmann S., Formisano L., Kinch L.N., Gonzalez-Ericson P.I., Sudhan D.R., Nagy R., Mathew A., Bernicker E.H., Cristofanilli M., He J., et al. Combined blockade of activating ERBB2 mutations and ER results in synthetic lethality of ER+/HER2 mutant breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:277–289. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce J.H., Arnstein P., DiMarco E., Artrip J., Kraus M.H., Lonardo F., Di Fiore P.P., Aaronson S.A. Oncogenic potential of erbB-2 in human mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1991;6:1189–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhai Y.F., Beittenmiller H., Wang B., Gould M.N., Oakley C., Esselman W.J., Welsch C.W. Increased expression of specific protein tyrosine phosphatases in human breast epithelial cells neoplastically transformed by the neu oncogene. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2272–2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabnis G., Brodie A. Understanding resistance to endocrine agents; Molecular mechanisms and potential for intervention. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2010;10:E6–E15. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hole S., Pedersen A.M., Hansen S.K., Lundqvist J., Yde C.W., Lykkesfeldt A.E. New cell culture model for aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer shows sensitivity to fulvestrant treatment and cross-resistance between letrozole and exemestsane. Int. J. Oncol. 2015;46:1481–1490. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telang N., Li G., Katdare M., Sepkovic D., Bradlow L., Wong G. Inhibitory effects of Chinese nutritional herbs in isogenic breast carcinoma cells with modulated estrogen receptor function. Oncol. Lett. 2016;12:3949–3957. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee M.R. Responses of mammary cells to hormones. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1976;47:1–97. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonelli Q.J., Custer R.P., Soroff S. Transformation of cultured mouse mammary glands by aromatic amines, amides and their derivatives. Cancer Res. 1979;39:1784–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telang N.T., Banerjee M.R., Iyer A.P., Kundu A.B. Neoplastic transformation of epithelial cells in whole mammary gland organ culture in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:5886–5890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sørlie T., Perou C.M., Tibshirani R., Aas T., Geisler S., Johnsen H., Hastie T., Eisen M.B., van de Rijn M., Jeffrey S.S., et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Hara J., Vareslija D., Mc Brian J., Bane F., Tibbits P., Byrne C., Conroy R.M., Hao Y., Gaorra P.O., Hill A.D.K., et al. AIB1: ER-α transcriptional activity is selectively enhanced in aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:3305–3315. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telang N.T., Narayanan R., Bradlow H.L., Osborne M.P. Coordinated expression of intermediate biomarkers for tumorigenic transformation in RAS-transfected mouse mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1991;18:155–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01990031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telang N.T., Arcuri F., Granata O.M., Bradlow H.L., Osborne M.P., Castagnetta L. Alteration of oestradiol metabolism in myc oncogene-transfected mouse mammary epithelial cells. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;77:1549–1554. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telang N.T., Katdare M., Bradlow H.L. Osborne MP and Fishman J: Inhibition of proliferation and modulation of estradiol metabolism: Novel mechanisms for breast cancer prevention by the phytochemical indole-3-carbinol. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1997;216:246–252. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta M., McDougal A., Safe S. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activities of 16α and 2–hydroxy metabolites of 17β-estradiol in MCF-7 and T47D human breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998;67:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(98)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telang N.T., Suto A., Wong G.Y., Osborne M.P., Bradlow H.L. Induction by estrogen metabolite 16α-hydroxyestrone of genotoxic damage and aberrant proliferation in mouse mammary epithelial cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1992;84:634–638. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.8.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suto A., Telang N.T., Tanino H., Takeshita T., Ohmiya H., Osborne M.P., Kubota T. In vitro andin vivo modulation of growth regulation in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by estradiol metabolites. Breast Cancer. 1999;6:87–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02966913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiebe J.P. Progesterone metabolites in breast cancer. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer. 2006;13:717–738. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gompel A., Somaï S., Chaouat M., Kazem A., Kloosterboer H.J., Beusman I., Forgez P., Mimoun M., Rostène W. Hormonal regulation of apoptosis in breast cells and tissues. Steroids. 2000;65:593–598. doi: 10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohammed H., Russell A.I., Stark R., Rueda O.M., Hickey T.E., Tarulli G.A., Serandour S.A., Birell S.N., Bruna A., Saadi A., et al. Progesterone receptor modulates estrogen receptor-α action in breast cancer. Nature. 2015;523:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature14583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swarbrick A., Lee C.S., Sutherland R.L., Musgrove E.A. Co-operartion of p27Kip1 and p18INK4c in progestin mediated cell cycle arrest in T-47D breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:2581–2591. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.7.2581-2591.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finlay-Schultz J., Gillen A.E., Brechbuhl H.M., Ivie J.J., Matthews S.B., Jacobsen B.M., Bentley D.L., Kabos P., Sartorius C.A. Breast Cancer Suppression by Progesterone Receptors Is Mediated by Their Modulation of Estrogen Receptors and RNA Polymerase III. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4934–4946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoldi G., Pellegrini P., Trinidad E.M., Cordero A., Gomez-Miragaya J., Serra-Musach J., Dougall W.C., Munoz P., Pujana M.A., Planelles L., et al. RANK Signaling Blockade Reduces Breast Cancer Recurrence by Inducing Tumor Cell Differentiation. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5857–5869. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walter K., Goodman M.L., Singhal H., Hall J.A., Li T., Holloran S.M., Trinca G.M., Gibson K.A., Jin V.X., Greene G.L., et al. Interferon-Stimulated Genes Are Transcriptionally Repressed by PR in Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:1331–1340. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bak M.J., Das Gupta S., Wahler J., Suh N. Role of dietary bioactive natural products in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016;40–41:170–191. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Telang N. Growth inhibitory efficacy of natural products in a model for triple negative molecular subtype of clinical breast cancer. Biomed. Rep. 2017;7:199–204. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poschner S., Maier-Salamon A., Thalhammer T., Jäger W. Resveratrol and other dietary polyphenols are inhibitors of estrogen metabolism in human breast cancer cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;190:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Valdeolivar C.A., Alvarez-Fitz P., Zacapala-Gomez A.E., Acevedo-Quiroz A., Caytana-Salazar L., Olea-Flores M., Castillo-Reyes J.U., Navarro-Tito N., Ortuno-Pineda C., Leyva-Vázquez M.A., et al. Phytochemical profile and anti-proliferative effect of Ficus crocata extracts on triple-negative breast cancer cells. BMC-Complement Med. Ther. 2020;20:19. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-02993-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Telang N. Natural phytochemicals as testable therapeutic alternatives for HER-2-enriched breast cancer (Review) World Acad. Sci. J. 2020;2:19. doi: 10.3892/wasj.2020.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telang N.T., Nair H.B., Wong G.Y. Growth inhibitory efficacy of Cornus officinalis in a cell culture model for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019;17:5261–5266. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Telang N.T., Nair H.B., Wong G.Y. Growth inhibitory efficacy of the nutritional herb Psoralea corylifolia in a model of triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Funct. Nutr. 2021;2:8. doi: 10.3892/ijfn.2021.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Telang N., Nair H., Wong G. Anti-Proliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Dipsacus Asperoides in a Cellular Model for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Arch. Breast Cancer. 2022;9:66–75. doi: 10.32768/abc.20229166-75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Telang N., Li G., Sepkovic D., Bradlow H.L., Wong G.Y.C. Comparative Efficacy of Extracts from Lycium Barbarum Bark and Fruit on Estrogen Receptor Positive Human Mammary Carcinoma MCF-7 Cells. Nutr. Cancer. 2013;66:278–284. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.864776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Telang N.T., Li G., Sepkovic D.W., Bradlow H.L., Wong G.Y. Anti-proliferative effects of Chinese herb Cornus officinalis in a cell culture model for estrogen receptor-positive clinical breast cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2011;5:22–28. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Telang N.T., Li G., Katdare M., Sepkovic D.W., Bradlow H.L., Wong G.Y. The nutritional herb Epimedium grandiflorum inhibits the growth in a model for the Luminal A molecular subtype of breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017;13:2477–2482. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston S.R.D., Dowsett M. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: Lessons from the laboratory. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:821–831. doi: 10.1038/nrc1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma C.X., Reinert T., Chmielewska I., Ellis M.J. Mechanisms of aromatase inhibitor resistance. Nat. Cancer. 2015;15:261–275. doi: 10.1038/nrc3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pasqualini J.R., Chetrite G. The anti-aromatase effect of progesterone and its natural metabolites 20α- and 5α-dihydroprogesterone in the MCF-7aro breast cancer cell line. Anticancer. Res. 2008;28:2129–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Telang N., Nair H.B., Wong G.Y. Growth inhibitory efficacy and anti-aromatase activity of Tabebuia avellanedae in a model for post-menopausal Luminal A breast cancer. Biomed. Rep. 2019;11:222–229. doi: 10.3892/br.2019.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soteriou D., Fuchs Y. A matter of life and death: Stem cell survival in tissue regeneration and tumor formation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:187–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cenciarini M.E., Proietti C.J. Molecular mechanisms underlying progesterone receptor action in breast cancer: Insights into cell proliferation and stem cell regulation. Steroids. 2019;152:108503. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2019.108503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Recouvreux M.S., Bessone M.I.D., Taruselli A., Todaro L., Huvelle M.A.L., Sampayo R.G., Bissell M.J., Simian M. Alterations in progesterone receptor isoform balance in normal and neoplastic breast calls modulates the stem cell population. Cells. 2020;9:2074. doi: 10.3390/cells9092074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castro N.P., Rangel M.C., Merchant A.S., MacKinnon G.M., Cuttitta F., Salomon D.S., Kim Y.S. Sulforaphane Suppresses the Growth of Triple-negative Breast Cancer Stem-like Cells In vitro and In vivo. Cancer Prev. Res. 2019;12:147–158. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S.-H., Singh S.V. Role of Kruppel-like factor4-p21 CIP1 axis in breast cancer stem-like cell inhibition by benzyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2019;12:125–134. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong M., Tan H.Y., Li S., Cheung F., Wang N., Nagamatsu T., Feng Y. Cancer Stem Cells: The Potential Targets of Chinese Medicines and Their Active Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:893. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manogaran P., Umapathy D., Karthikeyan M., Venkatachalam K., Singaravelu A. Dietary Phytochemicals as a Potential Source for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Investig. 2021;39:349–368. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2021.1894569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naujokat C., Mc Kee D.L. The “Big Five” phytochemicals targeting cancer stem cells: Curcumin, EGCG, Sulforaphane, Resveratrol and Genistein. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021;28:4321–4342. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200228110738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meerson A., Khatib S., Mahjna J. Natural products targeting cancer stem cells for augmenting cancer therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:13044. doi: 10.3390/ijms222313044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabos P., Finlay-Schultz J., Li C., Kline E., Finlayson C., Wisell J., Manuel C.A., Edgerton S.M., Harrell J.C., Elias A., et al. Patient-derived luminal breast cancer xenografts retain hormone receptor heterogeneity and help define unique estrogen-dependent gene signatures. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012;135:415–432. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cottu P., Bieche I., Assayag F., EL Botty R., Chateau-Joubert S., Thuleau A., Bagarre T., Albaud B., Rapinat A., Gentien D., et al. Acquired Resistance to Endocrine Treatments Is Associated with Tumor-Specific Molecular Changes in Patient-Derived Luminal Breast Cancer Xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:4314–4325. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruna A., Rueda O.M., Greenwood W., Batra A.S., Callari M., Batra R.N., Pogrebniak K., Sandoval J., Cassidy J.W., Tufegdzic-Vidakovic A., et al. A biobank of breast cancer explants with preserved intra-tumor heterogeneity to screen anti-cancer compounds. Cell. 2016;167:260–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sachs N., De Ligt J., Kopper O., Gogola E., Bounova G., Weeber F., Balgobind A.V., Wind K., Gracanin A., Begthel H., et al. A Living Biobank of Breast Cancer Organoids Captures Disease Heterogeneity. Cell. 2018;172:373–386.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pan B., Zhao D., Liu Y., Li N., Song C., Li N., Zhao Z. Breast cancer organoids from malignant pleural effusion-derived tumor cells as an individualized medicine platform. Vitr. Develop. Biol. Anim. 2021;57:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s11626-021-00563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.