Abstract

Purpose

Assess the impact of viral load estimated by cycle threshold (Ct) of reverse transcription real time-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) and the days from symptoms onset on mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID19.

Methods

Retrospective observational study of 782 patients with a positive rRT-PCR from a nasopharyngeal swab was performed within the first 24 h from admission. Demographic data, clinical manifestations and laboratory parameters were collected. Uni- and multivariate analyses were performed to identify factors associated with mortality at 60 days.

Results

Ct was divided into three groups and the mortality rate decreased from 27.3 to 20.7% and 9.8% for Ct values of ≤ 20, 21–25 and > 25, respectively (P = 0.0001). The multivariate analysis identified as predictors of mortality, a Ct value < 20 (OR 3.13, CI 95% 1.38–7.10), between 21–25 (OR 2.47, CI 95% 1.32–4.64) with respect to a Ct value > 25. Days from symptoms onset is a variable associated with mortality as well (DSOA) ≤ 6 (OR 1.86, CI 95% 1.00–3.46), among other factors. Patients requiring hospital admission within 6 DSOA with a Ct value ≤ 25 had the highest mortality rate (28%).

Conclusions

The inclusion of Ct values and DSOA in the characterization of study populations could be a useful tool to evaluate the efficacy of antivirals.

Keywords: COVID-19, Viral load, Ct value, Days of symptoms, Mortality

Introduction

At this point, more than 200 million cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been detected around the world with more than 4 million related deaths. A recent analysis of 44.415 confirmed cases in China described that 81% were asymptomatic or have a mild disease, 14% have a severe disease and 5% a critical disease with an overall mortality of 2.3% [1]. Among patients that require hospitalization, both the rate of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality are around 20% [2–4]. Risk factors for ICU admission and mortality have been associated with host factors (age, comorbidity), clinical manifestations (dyspnea, respiratory rate, need for oxygen therapy), and laboratory parameters (creatinine, C-reactive protein, lymphocytes cell count, ferritin, LDH serum concentrations or d-dimer parameters) at the moment of admission [5, 6]. Less attention has been paid to the potential influence of viral load on the progression and outcome of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19). A higher viral load, calculated from real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) adjusted by standard curves, has been associated with mortality (mean log10 viral load of 5.2 copies per mL in survivals versus 6.4 copies per mL in non-survivals) [7], however, this technique is time-consuming and not available everywhere.

The rRT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value represents the number of amplification cycles at which the fluorescent signal crosses a threshold level for positivity. The Ct is a semi-quantitative value inversely related to the initial amount of genetic material in the sample and therefore, can be used as an indirect estimate of the viral load. Several studies have shown a significant correlation between lower Ct values, meaning higher viral load, and COVID-19 severity and disease progression [8], however, fewer articles have analysed the correlation of the Ct value at admission with mortality showing contradictory results [9–13]. In addition, differences in the Ct cut-off values were reported in these articles being necessary to enlarge the knowledge to clarify the potential role of Ct value from nasopharyngeal swabs and how to interpret this value. Moreover, the viral load is higher within the first week of symptoms but the interpretation of the Ct values according to the days from symptoms onset needs to be defined.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the impact of viral load measured by the Ct value obtained at hospital admission and the days from symptoms onset on the mortality rate of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Study population and setting

Retrospective observational study based on patients with a definitive diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection by a positive rRT-PCR from a nasopharyngeal swab performed within the first 24 h from hospital admission at Hospital Clínic of Barcelona from March 1 to July 30, 2020. Patients were admitted due to respiratory symptoms and radiological evidence of pneumonia (uni or bilateral interstitial infiltrates) or with respiratory symptoms without pneumonia but with high-risk comorbidities. NP swabs were transferred to the laboratory using viral transport media.

Viral load assessment

76% of samples RNA were extracted with the MagNa Pure Compact (Roche, Penzberg, Germany) and rRT-PCR was performed using LightMix ModularDx Kit SARS-CoV (COVID19) E-gene (Tib Molbiol, Roche Diagnostics) with Roche LightCycler® 480 II according to manufacturer’s instructions. The other 24% were performed using, Cobas®6800 (Roche Diagnostic, Germany) which detected E and ORF1b genes. A positive result was defined when Ct value of gen E was ≤ 38. This information was not released to the clinicians therefore, it did not influence on clinical decisions.

Data collection

Data were retrospectively collected for all patients included in the study from the electronic health records (EHR). An intelligent system was used to retrieve the high-quality data from EHRs (SILDv1.0 system, S34M@) as previously described [14]. Variables used to adjust the potential influence of Ct value on the mortality were: age, sex, days from symptom onset to hospital admission (DSOA), co-morbidities (hypertension, chronic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, haematological neoplasia and solid neoplasia), air ambient oxygen saturation (SaO2) at admission, creatinine, lymphocyte count, C-reactive protein (C-RP), ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and d-dimer values within the first 24 h from hospital admission. The primary endpoint was mortality at 60 days. Variables were categorized according to the median except the Ct value.

The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona approved the study and due to the nature of the retrospective chart review, waived the need for informed consent from individual patients (Comité Ètic d’Investigació Clínica; HCB/2020/0273). All data are available prior request to the corresponding author.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described using the absolute number and percentage and continuous variables using the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using a Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. The cumulative probability of survival at 60 days after hospital admission by the 3 strata of Ct values is shown using a Kaplan–Meier plot and the differences were evaluated using a log-rank test. For multivariable analysis, variables with a P value ≤ 0.2 in the univariable analysis were subjected to further selection by using a forward logistic regression method. Interactions between variables were explored. The calibration of the model was assessed by means of the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to the measured predictive ability of the model. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value < 0.05. The analysis was performed in SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 782 patients admitted to Hospital Clínic with COVID-19 and an rRT-PCR positive test at the moment of admission were included in the study. The median (IQR) age was 66 (53–77) years old and 41.3% were females. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (44.2%), chronic heart disease (25.9%), diabetes mellitus (20.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (19.5%) and chronic kidney disease (13%). ICU admission was necessary in 17.4% of cases and the mortality rate at 60 days of the entire cohort was 14.5%.

The main characteristics of patients according to the outcome (mortality at 60 days) are depicted in Table 1. Age, comorbidity (hypertension, chronic heart diseases, diabetes mellitus, and haematological and solid neoplasia), oxygen saturation, serum creatinine, lymphocyte count, inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein, ferritin) and d-dimer were significantly associated with mortality. The Fisher exact test was applied to the follow variables: liver cirrhosis, solid organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus and non-invasive mechanical ventilation. Chi-square test was used for the rest of the variables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients according to mortality at day 60

| variable | Alive (n = 668) | Death (n = 114) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 66 years (%) | 277 (41.5) | 101 (88.6) | 0.0001 |

| Female sex (%) | 278 (41.6) | 45 (39.5) | 0.668 |

| Co-morbidity (%) | |||

|

Hypertension Chronic heart disease Diabetes mellitus Chronic liver disease Chronic kidney disease Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Hematological neoplasia Solid neoplasia Solid organ transplant |

268 (40.1) 142 (21.3) 122 (18.3) 27 (4) 69 (10.3) 128 (19.2) 37 (5.5) 91 (13.6) 16 (2.4) 14 (2.1) |

78 (68.4) 61 (53.5) 37 (32.5) 7 (6.1) 33 (28.9) 25 (21.9) 14 (12.3) 27 (23.7) 4 (3.5) 4 (3.5) |

0.0001 0.0001 0.001 0.319 0.0001 0.491 0.007 0.006 0.516 0.317 |

| DSOA ≤ 6a (%) | 298 (51.6) | 70 (71.4) | 0.0001 |

| SaO2 ≤ 94%b (%) | 266 (42) | 65 (58.6) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine > 1 mg/dLc (%) | 71 (10.7) | 42 (36.8) | 0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte count ≤ 800 × 109/L (%) | 317 (47.5) | 78 (68.4) | 0.0001 |

| C-reactive protein > 7 mg/dLd (%) | 269 (40.6) | 83 (72.8) | 0.0001 |

| Ferritin > 517 ng/mLe (%) | 235 (47.7) | 53 (63.9) | 0.006 |

| LDH > 293 U/Lf (%) | 283 (46.8) | 69 (67) | 0.0001 |

| d-dimer > 700 ng/mLf (%) | 251 (41.4) | 78 (76.5) | 0.0001 |

| Cycle threshold (%) | |||

|

≤ 20 21–25 > 25 |

72 (10.8) 146 (21.9) 450 (67.4) |

27 (23.7) 38 (33.3) 49 (43) |

0.0001 |

| Intensive care unit admission (%) | 103 (15.4) | 33 (28.9) | 0.0001 |

DSOA days from symptoms onset to admission, SaO2 oxygen saturation at ambient air

aMeasured in 676

bMeasured in 745

cMeasured in 780

dMeasured in 777

eMeasured in 576

fMeasured in 708

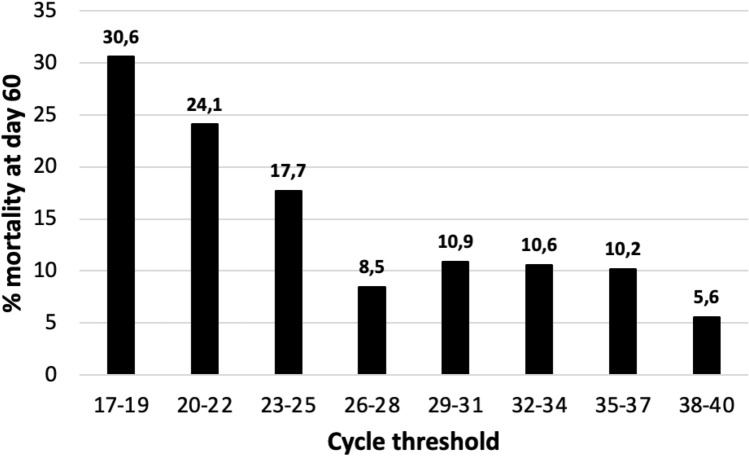

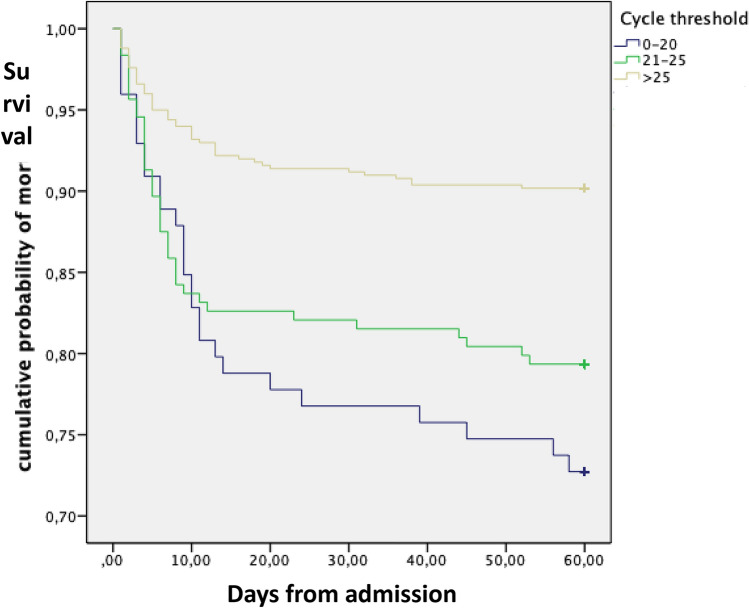

Since the increase in 3.3 points in the Ct value usually represents a tenfold reduction of viral RNA in efficient rRT-PCR assays we have represented the mortality rate for groups of 3 consecutive Ct values (Fig. 1). We have considered a difference of at least a 5% in the mortality rates to determine the cut-off to divide the whole samples into three groups. The mortality rate progressively decreased from 27.3% when the Ct values were ≤ 20 to 20.7% and 9.8% for values of 21–25 and > 25, respectively (P = 0.0001). The cumulative probability of non-survival at 60 days by the Ct strata is shown in Fig. 2 and the comparison of the curves using the Log-Rank test was statistically significant (P = 0.0001). The multivariate analysis identified age, older than 66 years, chronic heart disease, the number of DSOA ≤ 6, C-RP > 7 mg/dL, d-dimer > 700 ng/mL and Ct value < 20 and between 21 and 25 with respect to Ct values > 25 as predictors of mortality (Table 2). The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (P = 0.59), and the area under the ROC curve was 0.88 (95%CI, 0.86–0.91) showing a good ability to predict mortality at 60 days.

Fig. 1.

The mortality rate at 60 days by the Ct value from ≤ 19 to ≥ 38

Fig. 2.

Cumulative probability of survival at day 60 according to the cycle threshold at admission

Table 2.

Variables independently associated with mortality at day 60

| variable | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age > 66 years | 9.56 (3.87–23.62) | 0.0001 |

| Chronic heart disease | 2.55 (1.41–4.64) | 0.002 |

| DSOA ≤ 6 | 1.86 (1.00–3.46) | 0.047 |

| d-dimer > 700 ng/mL | 2.41 (1.29–4.53) | 0.006 |

| C-reactive protein > 7 mg/dL | 2.37 (1.25–4.49) | 0.008 |

| Cycle threshold | ||

|

> 25 21–25 ≤ 20 |

1 2.47 (1.32–4.64) 3.13 (1.38–7.10) |

0.006 0.005 |

DSOA days from symptoms onset to admission

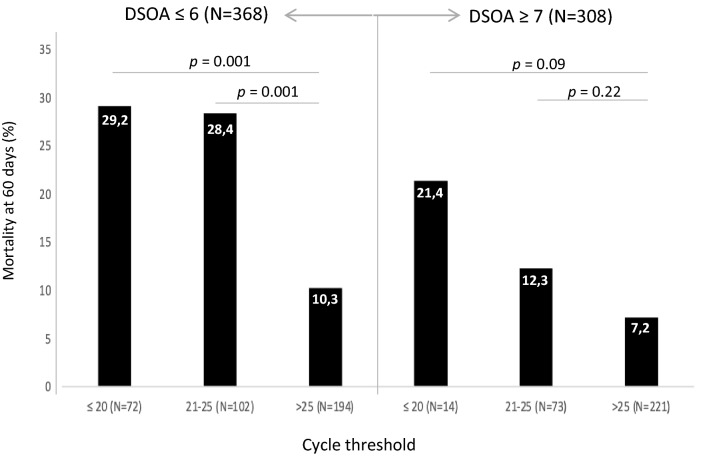

The number of DSOA is a non-previously evaluated variable. The multivariate analysis from our cohort highlights its importance. The mortality rate among those patients that required hospital admission, according to our hospital criteria (see “Methods”), within the first 6 days from symptoms onset was 19% while it was 9.1% for those that had ≥ 7 days of symptoms when the hospitalization was considered necessary. In Fig. 3, we show the mortality rate by DSOA (≤ 6 days vs. ≥ 7 days) among the 3 groups of Ct values. Patients with a severe infection requiring hospital admission within the first 6 days from symptoms onset with a Ct value ≤ 25 had a significantly higher mortality than those with a Ct value > 25. For patients with ≥ 7 DSOA, the differences were not statistically significant, but the mortality rate was higher in patients with low Ct, particularly among those with Ct values ≤ 20.

Fig. 3.

Mortality rate at 60 days according to the number of days from symptoms onset to admission (DSOA) and the cycle threshold

Discussion

This study endorses that the Ct value obtained from a NP at admission is an independent predictor of mortality and that the cut-off point is ≤ 20 for a threefold increased risk and 21–25 for a twofold increased risk with respect to a Ct > 25 (Fig. 2). This cut-off agrees with prior data showing that the probability of successfully cultivating SARS-CoV-2 on Vero cells culture lines was significantly lower from Ct values > 24[15]. Ct is inversely related to viral load; therefore, our data support the direct effect of high and sustained viral load on the outcome of COVID-19, probably as a crucial trigger for a dysregulated immune response that finally leads to a higher mortality. Two previous studies identified a positive correlation between the Ct values and mortality [9, 10], but the median Ct values in both studies varied significantly, from 27.9 in the one from the United States to 36.9 in the one from China. This difference might be related to a different performance of the rRT-PCR assays used, but we consider that the most likely explanation is the different populations evaluated. The high Ct value and the low mortality rate in the Chinese study (5.2%) suggest that patients were admitted after a long period from symptoms onset. Unfortunately, we could not confirm this hypothesis since the information about days from symptoms onset was not provided. In contrast, the mortality rate and the median Ct values from our study (14.5% and 28) were similar to the ones from the US (19.2% and 27.9), which probably suggests a high similarity between both cohorts. Magleby et al. [9] evaluated different cut-offs, < 25, 25–30 and > 30. Mortality clearly increased from a Ct value of 25–14 as it happened in our cohort (Fig. 1). This cut-off is in line with results from Bullard et al. [15] showing a clear correlation between lower Ct values and a higher probability of isolating infectious SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture.

As it was previously described [15], Ct values are lower (meaning high viral load) around the onset of symptoms, but there is no prior data showing whether the Ct value is equally effective in predicting mortality according to DSOA. By doing this analysis, we observed that the number of DSOA is an important variable associated with mortality. The multivariate analysis identified that patients admitted within the first 6 days from symptoms onset had almost twofold higher mortality (Table 2). In addition, the highest mortality rate in our cohort was observed among patients with a short duration from symptoms onset to severity and a Ct value ≤ 25 (28%). Taken together, these results uphold patients unable to early control viral replication due to different factors including age, co-morbidity or genetics, are at a higher risk of triggering an early dysregulated inflammatory response that enhances the possibility of hospital admission and death. This evidence indicates that the three well-differentiated phases established by Siddiqui et al. are indeed overlapped. Therefore, early hospitalized patients with pneumonia and laboratory markers of inflammation (e.g., high C-RP) require combination therapy with antivirals and anti-inflammatory therapies.

On the other hand, although the mortality was lower among those patients with ≥ 7 DSOA, we observed a non-significant trend towards a higher mortality among patients with low Ct values, most especially at values ≤ 20 (Fig. 3). This is in line with the studies showing that in patients with mild infection viable virus could not be cultured after day 8 [16] but it could be longer (15–20 days) in severe patients [17]. Prebensen et al. [13] did not find a correlation between Ct value from upper respiratory sample and ICU admission and mortality, however, the mean number of days from symptoms onset to admission was 9, the total number of patients evaluated was low (n = 123), and they did not explore the impact of very low Ct values. Recent articles performed in patients mainly during the second week of the illness show a potent prediction of mortality among those with RNAmia [13, 18–20], therefore, we can conclude that Ct from upper respiratory samples is helpful for predicting the outcome mainly among patients within the first week of COVID-19 while RNAmia could be the best predictor during the second week. In addition, ours results could impact the evaluation of antiviral therapy. As an example, the double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of remdesivir vs. placebo clearly showed that the major benefit occurred when it was administered within the first 10 days from symptoms onset [21] although some benefits remained beyond 10 days. In the future, it will be necessary to evaluate the efficacy of antivirals not only according to the clinical picture and DSOA but also to the viral load using the Ct value from upper respiratory samples and RNAmia.

The major limitation of our study is that the platform used for PCR performance was not homogeneous. This was due to the difficulties of material supply during pandemics and the consequent need to diversify the methods. Although 76% of samples were done using the same system, we cannot rule out potential variations due to the 24% samples performed with other platform, however, our results match well with other authors’ experience [9] and most important, there is data showing an excellent correlation in the Ct value (r2 = 0.96) between the 2 kits used in our study [22]. On the other hand, we used E gene since it has the highest sensitivity [23], although not specific for SARS-CoV-2, there is no cross reactivity with the commonly circulating human coronaviruses, and SARS-CoV is not circulating. Thus, detection of the E gene indicates the presence of SARS-CoV-2. The second limitation is that we analyzed mortality at 60 days based on our electronic health records, therefore, missing deaths are possible if some patients were transferred to other centers.

From our point of view, another limitation of our study is that we only included hospitalized patients. However, a recent clinical trial made in COVID19 outpatients showed sustained low Ct values from day 3 to 7 of symptoms onset among the population that required hospitalization [24], supporting the concept that severity of COVID-19 is associated with poor viral replication control.

In conclusion, the Ct value is an independent predictor of mortality at 60 days and the most reliable cut-off point is ≤ 25. The analysis also suggests that the influence of the Ct value is greater within the first week from symptoms onset as we would expect from the already known viral dynamics. Therefore, to properly evaluate the efficacy of antivirals it would be useful to include the Ct value and the DSOA in the parameters used to define the study population [25].

Acknowledgements

“This work has been financed by funds for research ad hoc COVID-19 from citizens and organizations patronage to Hospital Clínic de Barcelona-Fundació Clínic per a la Recerca Biomèdica”.

Hospital Clinic of Barcelona COVID-19 Research Group: Infectious Diseases’ Research Group: Blanco JL, Mallolas J, Martínez E, Martínez M, Miró JM, Moreno A, Del Rio A, Solá M, Torres M, Ugarte A, Cozar-Lladó A, Linares L and all the staff members. Medical Intensive Care Unit: Tellez A, Fernandez S, Nicolas JM and all the staff members. Department of International Health: Campubri D, de Alba MT, Fernandez M, Ferrer E, Grau B, Marti H, Muelas M, Pinazo MJ, Rodriguez N, Roldan M, Subira C, Vera I, Williams N, Almuedo-Riera A and all the staff members. Department of Internal Medicine: Aldea A, Camafort M, Calvo J, Capdevila A, Cardellach F, Carbonell I, Coloma E, Foncillas A, Estruch R, Feliu M, Fernández-Solá J, Fuertes I, Gabara C, Grafia I, Ladino A, López-Alfaro R, López-Soto A, Masanés F, Matas A, Navarro M, Marco-Hernández J, Miguel L, Milisenda JC, Moreno P, Naval J, Nicolás D, Oberoi H, Padrosa J, Prieto-González S, Pellicé M, Ribot J, Rodríguez-Núnez O, Sacanella E, Seguí F, Sierra C, Tomé A, Torres M, Ventosa H, Zamora-Martínez C, and all the staff members. Department of Microbiology: Almela M, Alvarez M, Bosch J, Costa J, Cuesta G, Fidalgo B, Gonzàlez J, Marco F, Narvaez S, Pitart C, Rubio E, Vergara A, Valls ME, Zboromyrska Y Casals C, Mosquera M and all the staff members. Department of Pharmacy: López E, Tuset M and all the staff members.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by VR-C, MF, JCH, CC, GD, IM, GC, FM, JAM, GS, JM and AS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by VR-C, MAM, JM and AS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Writing—original draft: VR, MF and AS; writing—review and editing: all authors; conceptualization: AS; investigation: all authors; methodology: VR, JAM, and AS; formal analysis: VR, MF, JAM and AS.

Funding

No funding resources were obtained for the elaboration of this study.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The license of the software used for the statistical analysis is given by the University of Barcelona to all its investigators for free.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

CGV has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Science, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Jannsen, and Lilly, as well as a grant from Gilead Science and MSD. PPA has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Gilead Science and MSD. JM has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Novartis, and Angellini. AS has received honoraria for talks on behalf of Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Novartis, and Angellini, as well as grant support from Pfizer. Other authors do not declare conflict of interest. All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest applying to this study.

Ethical standards

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethical Committee of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona has approved the design of this study (Comité Ètic d’Investigació Clínica; HCB/2020/0273) and have wavered the need of obtained informed consent from the participants.

Informed consent

The need for informed consent has been wavered from the Ethical Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applying.

Footnotes

The members of COVID-19-Researcher Group are listed in Acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Alex Soriano, Email: asoriano@clinic.cat.

COVID-19-Researcher Group:

J. L. Blanco, J. Mallolas, E. Martínez, M. Martínez, J. M. Miró, A. Moreno, A. Del Rio, M. Solá, M. Torres, A. Ugarte, A. Cozar-Lladó, L. Linares, A. Tellez, S. Fernandez, J. M. Nicolas, D. Campubri, M. T. de Alba, M. Fernandez, E. Ferrer, B. Grau, H. Marti, M. Muelas, M. J. Pinazo, N. Rodriguez, M. Roldan, C. Subira, I. Vera, N. Williams, A. Almuedo-Riera, A. Aldea, M. Camafort, J. Calvo, A. Capdevila, F. Cardellach, I. Carbonell, E. Coloma, A. Foncillas, R. Estruch, M. Feliu, J. Fernández-Solá, I. Fuertes, C. Gabara, I. Grafia, A. Ladino, R. López-Alfaro, A. López-Soto, F. Masanés, A. Matas, M. Navarro, J. Marco-Hernández, L. Miguel, J. C. Milisenda, P. Moreno, J. Naval, D. Nicolás, H. Oberoi, J. Padrosa, S. Prieto-González, M. Pellicé, J. Ribot, O. Rodríguez-Núnez, E. Sacanella, F. Seguí, C. Sierra, A. Tomé, M. Torres, H. Ventosa, C. Zamora-Martínez, M. Almela, M. Alvarez, J. Bosch, J. Costa, G. Cuesta, B. Fidalgo, J. Gonzàlez, F. Marco, S. Narvaez, C. Pitart, E. Rubio, A. Vergara, M. E. Valls, Y. Zboromyrska, C. Casals, M. Mosquera, E. López, and M. Tuset

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in china summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1240–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area. JAMA. 2020;323:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Vidal C, Moreno-García E, Hernández-Meneses M, et al. Personalized therapy approach for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;74:127–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, et al. Risk factors of critical and mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang JJY, Lee KS, Ang LW, Leo YS, Young BE. Risk factors of severe disease and efficacy of treatment in patients infected with COVID-19: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2199–2206. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujadas E, Chaudhry F, McBride R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e70. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao SN, Manissero D, Steele VR, Pareja J. A systematic review of the clinical utility of cycle threshold values in the context of COVID-19. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:573–586. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magleby R, Westblade LF, Trzebucki A, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory sindrome coronavirus 2 viral load on risk of intubation and mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e4197–e4205. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J-T, Ran R-X, Lv Z-H, et al. Chronological changes of viral shedding in adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan. China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2158–66. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westblade LF, Brar G, Pinheiro LC, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts mortality in patients with and without cancer who are hospitalized with COVID-19. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:661–671.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faíco-Filho KS, Passarelli VC, Bellei N. Is higher viral load in SARS-CoV-2 associated with death? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2019–2021. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prebensen C, Hre PLM, Jonassen C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in plasma is associated with ICU admission and mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. CID. 2020.

- 14.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Puerta-Alcalde P, Moreno-García E, Soriano A. Artificial intelligence to support clinical decision-making processes. EBioMedicine. 2019;46:27–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, et al. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples. CID. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Rhee C, Kanjilal S, Baker M, Klompas M. Duration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infectivity: when is it safe to discontinue isolation? CID. 2020;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.van Kampen JJA, van de Vijver DAMC, Fraaij PLA, et al. Shedding of infectious virus in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): duration and key determinants. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;1–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Xu D, Zhou F, Sun W, et al. Relationship Between serum SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid (RNAemia) and organ damage in COVID-19 patients: a cohort study. CID. 2020.

- 19.Hagman K, Hedenstierna M, Gille-Johnson P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in serum as predictor of severe outcome in COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. CID. 2021;73(9):e2995–e3001. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veyer D, Kernéis S, Poulet G, et al. Highly sensitive quantification of plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA shelds light on its potential clinical value. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73 (9):e2890–e2897. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poljak M, Korva M, Gašper NK, et al. Clinical evaluation of the cobas SARS-CoV-2 test and a diagnostic platform switch during 48 hours in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(6):e00599–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00599-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman H, Carter I, Basile K, et al. Interpret with caution: an evaluation of the commercial AusDiagnostics versus in-house developed assays for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104374. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim PS, Read SW, Fauci AS. Therapy for early COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(21):2149–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The license of the software used for the statistical analysis is given by the University of Barcelona to all its investigators for free.