Abstract

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the delivery of life-saving and life-prolonging health services for oncology care and supporting services was delayed and, in some cases, completely halted, as national health services globally shifted their attention and resources towards the pandemic response. Prior to March 2020, telehealth was starting to change access to health services. However, the onset of the global pandemic may mark a tipping point for telehealth adoption in healthcare delivery. We conducted a systematic review of literature published between January 2020 and March 2021 examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult cancer patients. The review’s inclusion criteria focused on the economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients and the availability of telehealth services emerged as a key theme. The studies reviewed revealed that the introduction of new telehealth services or the expansion of existing telehealth occurred to support and enable the continuity of oncology and related services during this extraordinary period. Our analysis points to several strengths and weaknesses associated with telehealth adoption and use amongst this cohort. Evidence indicates that while telehealth is not a panacea, it can offer a “bolstering” solution during a time of disruption to patients’ access to essential cancer diagnostic, treatment, and aftercare services. The innovative use of telehealth has created opportunities to reimagine the delivery of healthcare services beyond COVID-19.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, telehealth, COVID-19, pandemic, patients, systematic review

1. Introduction

Health systems worldwide pivoted towards telehealth when the COVID-19 pandemic started [1]. This means that a range of consultations and services was delivered via telephone, video conferencing, and other messaging services [2], extending from consultations with general practitioners in primary care to specialist consultants in hospitals across medical areas, including cancer care [3]. This was particularly pertinent for cancer patients and survivors who are at greater risk of infection and developing more severe health complications compared to the general population, due to their weakened immune systems [3]. Globally, telehealth combined with other public health guidelines and initiatives, such as dedicated pathways and hubs, helped protect cancer patients and survivors from exposure to COVID-19.

In the current literature, a range of terms is used to describe the use of information and communication technology (ICT) to either deliver health services, transfer information, and/or provide education to patients and healthcare professionals at a distance [4]. For this study, we use the term “Telehealth” to characterise two-way communications among stakeholders [5] and their use of ICT [6,7] to enable the delivery of healthcare, exchange of health data, and dissemination of health-related education across geographically dispersed locations [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Research indicates that telehealth primarily focuses on the delivery of healthcare services [7,13,14], including the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries [8]. The terms telehealth, telemedicine, and telecare are often used interchangeably. Telehealth is an overarching term involving clinical and non-clinical applications and encompasses both telecare and telemedicine [9]. Telecare occurs when a health-related request for assistance is made; a disease is not necessary to prompt such a request, and the other actor is not necessarily a healthcare professional [9]. Whereas telemedicine is typically more clinical, focusing on patient assessment, diagnosis, and treatment [9]. Colucci et al. [9] classify both telehealth and telemedicine as communication strategies whereby an action is taken remotely for the purpose of providing care or a cure. Telehealth also encompasses tele-radiology, tele-stroke, tele-ICU, tele-psychiatry, tele-burn, tele-prescription, and virtual care [15]. The role of healthcare professionals is core to the delivery of telehealth services [8].

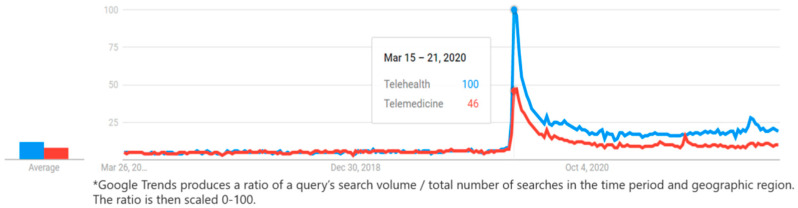

Data from Google Trends (an online tool for comparison of the popularity of terms searched by users of Google Search and their trends over time) (Figure 1) illustrate the relative number of searches (based on the total volume of searches over time by geographic region) for the terms “Telehealth” and “Telemedicine” since 2017. As evidenced, these terms were widely searched for during March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, with Google Trends highlighting telehealth as the more popular search term.

Figure 1.

Google Trends search for “Telehealth” and “Telemedicine” (2017–2022).

The pattern illustrated in Figure 1 supports Edwards et al.’s [6] assertion that healthcare professionals are more familiar with the term telehealth compared with telemedicine. Indeed, March 2020 marks a time when frontline healthcare professionals scrambled to identify new ways to communicate with and deliver healthcare services to the most vulnerable patients [16].

There are many benefits associated with telehealth adoption; these include reported high levels of patient satisfaction with the telehealth experience [17], efficiency, privacy, comfort [18], and improved convenience, particularly for patients with physical limitations [19] as they can access important services from their own home. Other studies identify reduced fuel and parking costs and the cost of work absence [20] as financial benefits for patients. While, in their study of telehealth neonatal services, Ballantyne et al. [21] highlight avoiding traffic, not being late for appointments, and not having to arrange childcare as motivators for telehealth adoption. Advantages for healthcare providers include being able to access patients from their home offices [22] and reducing patient no-shows [23]. However, some studies identify challenges such as equipment costs, patient privacy, insufficient training, and limited communication between clinicians and information technology specialists [24].

We conducted a systematic literature review examining the social, psychological, health, and economic impacts of COVID-19 on cancer patients. This review captured the first wave of the pandemic, exploring the immediate responses of stakeholders to the crisis, thus revealing how healthcare services were taking steps to mitigate the effects of the pandemic for the most vulnerable patients. Telehealth emerged as a key theme; findings are presented here. This article is structured as follows; the next section describes the research materials and methods used and the systematic literature review execution. The following section reports the results and discussion. Finally, the conclusion considers limitations, implications arising from this study, and opportunities for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology for this systematic review was guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [25] and the population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, context, studies (PICOCS) framework was employed [26] (Table 1). The review’s inclusion criteria were limited to studies that focus on the economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients/survivors; studies written in English and published between January 2020 and March 2021. The following types of studies were excluded: letters to the editor, editorials, case studies, reports, protocols, commentaries, short communications, reviews, opinions, perspectives, and discussions (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021246651). The search strategy was developed using a combination of free text words and subject headings relevant to CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, and EMBASE platforms and was refined using Boolean operators. The search was conducted on 31 March 2021.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria and search terms.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Search Terms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult population (>18 years old) Current cancer patients and survivors (2 years post-diagnosis) |

Caregivers, nursing and medical staff, and paediatric cancer patients | “cancer” OR “oncology” OR “malignant” OR “tumour” OR “metastasis” OR “neoplasm” |

| Intervention | COVID-19 pandemic | - | “COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “2019-ncov” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “cov-19” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2” OR “pandemic” |

| Outcome | economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients/survivors | - | “financial toxicity” OR “out-of-pocket” OR “productivity” OR “absenteeism” OR “unemployment” OR “cost” OR “waiting time” OR “expenses” OR “financial stress” OR “inconvenience” OR “opportunity cost” OR “income” OR “wellbeing” OR “social isolation” OR “exclusion” OR “loneliness” OR “happiness” OR “life satisfaction” OR “fatigue” OR “insomnia” OR “psychological distress” OR “emotional distress” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “psychological” OR “quality of life” OR “health-related quality of life” OR “survival” OR “mortality” OR “disease progression” OR “diagnosis” OR “screening” OR “recurrence” OR “disease stage” OR “delay” OR “support” OR “surgery” OR “treatment” OR “target therapy” OR “radiotherapy” OR “chemotherapy” OR “immunotherapy” OR “hormone therapy” OR “survivorship programme” OR “follow-up-care” |

| Context | Hospital and community setting | - | |

| Studies | Full-text articles Patient perspective, Observational, Cross-sectional, Prospective, Longitudinal Retrospective |

Letters to the editor, editorials, case studies, reports, protocols, commentaries, short communications, reviews, opinions, perspectives, and discussions |

Data extraction is presented in a tabular format to assist in reporting uniformity and reproducibility and minimise bias. Included elements: general information: title, author(s), year of publication, country; study characteristics: aim/objective, perspective, study design, reason for inclusion; population characteristics: sample size, type of cancer, age, gender, patient, or survivor group; methods: context/setting, data source, study timeframe, data collection methods, data analysis methods; and outcome variables: economic impact, social impact, health-related impact, psychosocial impact. The JBI critical appraisal tools for cross-section, prevalence, qualitative, and cohort [27] as appropriate and CHEC list [28] for cost analyses were used to assess quality. The evidence was pooled and summarised to create an inventory of results with a narrative synthesis. Two authors (AL and AK) independently performed quality assessment. If there was conflict or uncertainty, a third author (AM) was consulted. Risk of bias in a study was considered high if the “yes” score was ≤4; moderate if 5–6; and low risk if the score was ≥7 on the JBI tools. Quality review results are presented in Appendix A.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Search Results

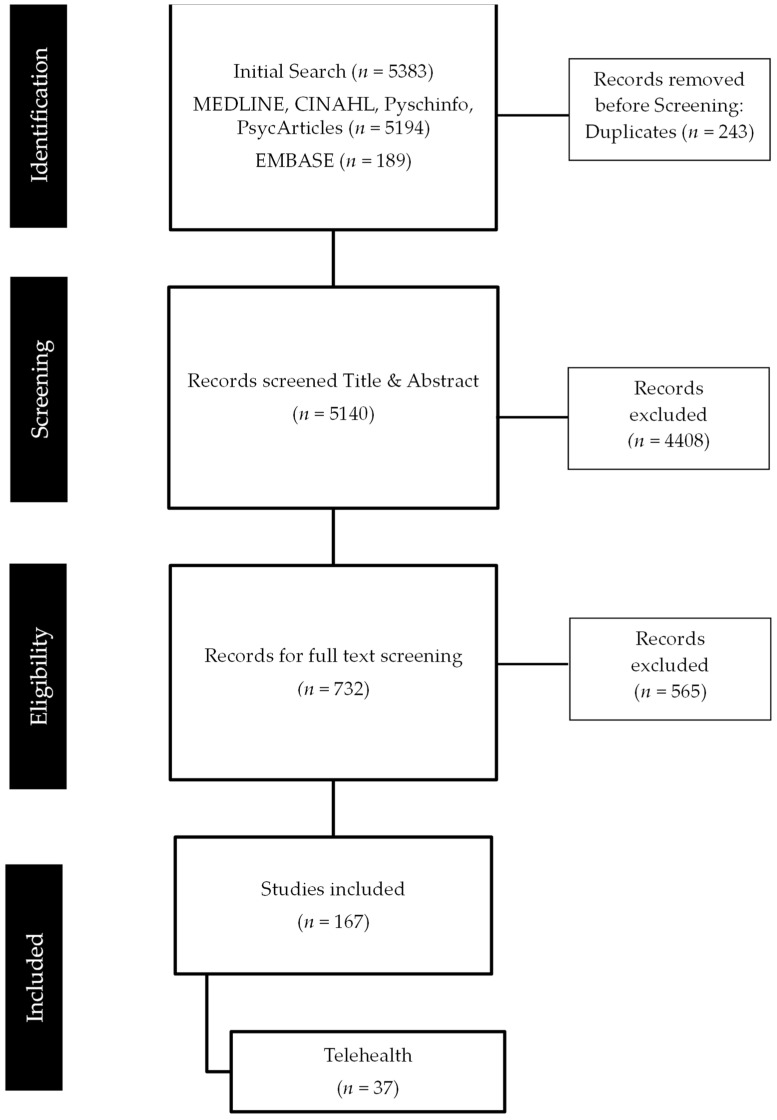

The search initially yielded 5383 studies, of which 167 were considered for full text review (see Murphy et al. [29] for further information). The review’s inclusion criteria focused on the economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients and the availability of telehealth services emerged as a key theme (See Appendix B). Overall, 37 of the 167 articles reported on the use of telehealth in delivering oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2). In this collection, many papers detailed experiences of telehealth in the USA (35%) and referred to services available for multiple/all cancer types (67%). Most of which were in a hospital setting (92%), two were in the community (5%), and one was web-based (3%).

Figure 2.

Search results.

Telehealth services were employed in various stages of cancer treatment, including screenings/referrals [30]; radiation oncology [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]; surgical oncology [38,39,40,41]; follow-ups and counselling services [42,43,44,45,46,47,48]; rehabilitation services [49]; and palliative care [50,51,52]. Other studies considered telehealth across the delivery of oncology services in specific institutions [15,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Several studies assessed satisfaction/acceptability of telehealth services introduced standalone or as part of organisational changes during the pandemic [43,50,51,52,53,55,57,59,60]. One study considered the costs of delivering and accessing telehealth [61]. A range of study designs was reported, including retrospective, prospective, cross-sectional, and observational and a mix of primary and secondary data sources was employed (see Table 2 for study details).

Table 2.

Overview of Review Papers (See Appendix C for further information).

| Author Year Country | Aim | Telehealth Tool | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akhtar et al. (2021) [38] India | Describe the hospital experience during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Akuamoa-Boateng et al. (2020) [33] Germany | Compare hospital management in 2019 & 2020 | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients Video conferencing for staff |

|

| Alterio et al. (2020) [34] Italy | Report organisation strategies at a radiation oncology department, focusing on procedures and scheduling (i.e.: delays, interruptions) | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Araujo et al. (2020) [56] Latin America | Evaluate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patient volume in a cancer centre in an epidemic of the pandemic | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients Video conferencing for staff |

|

| Atreya et al. (2020) [50] India | (1) Assess changes in the hospital-based practice of palliative care during the pandemic (2) Report patient/caregivers perception about the provision of palliative telehealth services (established 2014) |

Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Biswas et al. (2020) [51] India | (1) Assess expansion of service telemedicine in the palliative unit in the department of oncology (2) Assess patient satisfaction. |

Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone, texts and video) for patients |

Patient satisfaction: 56 very satisfied; 152 satisfied; 59 partially satisfied; 47 unsatisfied; 42 patients believed that face-to-face consultations may be more useful for them |

| Brenes Sanchez et al. (2021) [39] Spain | Anlayse management breast cancer patients during the pandemic | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Caravatta et al. (2020) [35] Italy | Report the experience and organisational planning of radiotherapy during pandemic | Telephone consultations. Telematics laboratory results Staff meetings on a telematic platform |

|

| Clark et al. (2021) [48] England | Assess the national impact of COVID-19 on the prescribing of systemic anti-cancer treatment | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| De Marinis et al. (2020) [36] Italy | Examine proactive management to minimise contagion among patients with lung cancer | Telephone consultations Telematics laboratory results |

|

| Earp et al. (2020) [40] USA | Examine the early effect of hospital and state mandated restrictions on an orthopedic surgery department | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone and video) for patients |

|

| Frey et al. (2020) [62] USA | (1) Evaluate the quality of life (QoL) of women with ovarian cancer during the pandemic (2) Evaluate the effects of the pandemic on cancer-related treatment. |

Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients Online counselling Online networks |

|

| Goenka et al. (2021) [31] USA | Review implementation of patient access to care & billing implications | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone and video) for patients |

|

| Kamposioras et al. (2020) [59] England | (1) Investigate the perceptions of service changes imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. (2) Identify the determinant of anxiety in patients with colorectal cancer |

Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone and video) for patients |

|

| Kotsen et al. (2021) [42] USA | Examine the effect of rapid scaling to tobacco treatment telehealth for tobacco dependent cancer patients | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Kwek et al. (2021) [47] Singapore | Describe outpatient attendances and treatment caseloads during COVID-19 compared to pre COVID-19. | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients and family members. Tele-counselling& psychosocial support. Medication delivery. |

|

| Lonergan et al. (2020) [15] USA | Analyse the change in video visit volume | Video consultations |

|

| Lopez et al. (2021) [49] Canada | Describe adaptions to implement virtual cancer rehabilitation at the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone and video) for patients |

Re: Meeting support needs: sense of reassurance and felt supported, helped cope with worries, some felt isolated by telemedicine. Re: Confidence with assessment and care plan: lack of in-person examination, relying on self-report/assessment of patients, worried about accuracy of describing symptoms, agreed video better than telephone visits, Both agreed preference for an initial in-person assessment. |

| Maganty, et al. (2020) [30] USA | Evaluate differences in patient populations being evaluated for cancer before and during the COVID-19 pandemic | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Mahl et al. (2020) [63] Brazil | Evaluate delays in care for patients with head and neck cancer in post-treatment follow-up or palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic | - |

|

| Merz et al. (2021) [43] Italy | Assess breast cancer survivors perceptions electronic medical record-assisted telephone follow-up | Electronic medical record-assisted telephone consulation/appointment. |

|

| Mitra, et al. (2020) [64] India | Study the challenges faced by cancer patients in India during the COVID-19 pandemic | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Narayanan et al. (2021) [44] USA | Report on the feasibility of conducting Integrative Oncology physician consultations via telehealth | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Parikh, et al. (2020) [61] USA | Evaluate changes in resource use associated with the transition to telemedicine in a radiation oncology department | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Patt et al. (2020a) [65] USA | Gain insights into the impact of COVID-19 on the US senior cancer population | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Patt, et al. (2020b) [54] USA | (1) Describe onboarding and utilization of telemedicine across a large statewide community oncology practice (2) Evaluate trends, barriers, and opportunities in care delivery during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic |

Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients Virtual support groups (social workers provided) & tele-pharmacy |

|

| Patt et al (2021) [53] USA | Assess the implementation of multidisciplinary telemedicine in community oncology; providers and patients satisfaction; changes in clinic operations; opportunities and barriers | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Rodler et al (2020) [57] Germany | Determine patients’ perceptions on adoption of telehealth as a response to the pandemic and its sustainability in the future | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients Video conferencing |

|

| Romani et al. (2021) [32] Canada | Examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the operation of satellite radiation oncology facility and patient satisfaction | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Sawka, et al. (2021) [37] Canada | Describe the management of small low risk papillary thyroid cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic | Telephone and video communciations. |

|

| Shannon, et al. (2020) [45] USA | Determine how visit and genetic testing volume was impacted by new telephone genetic counselling and home testing. | New telephone genetic counselling and home testing. |

|

| Smrke, et al. (2020) [55] UK | Evaluate the impact of telemedicine on patients, clinicians, care delivery | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments for patients |

|

| Somani et al. (2020) [58] UK | Assess outpatient and telemedicine (phone and video) volume during the pandemic. | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone and video) for patients |

|

| Sonagli et al. (2021) [46] Brazil | Demonstrate how telemedicine was an efficient tool to maintain outpatient appointments for breast cancer patients follow up and surveillance | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (video) for patients |

|

| Wai et al. (2020) [41] USA | Explore the impact on surgical care of head & neck cancer patients |

|

|

| Wu et al. (2020) [52] Taiwan | Assess smartphone enabled telehealth model for palliative care family conferences | Video conferencing |

|

| Zuliani et al. (2020) [60] Italy | Analyse COVID-19 related organisational changes. | Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (telephone) for patients |

|

3.2. Range of Telehealth Services Employed

In some instances, hospitals and health centres used and/or expanded existing telehealth services during the pandemic [15,32,40,50,51,53,54]. However, many studies demonstrated the development of new telehealth services in response to the pandemic. These telehealth initiatives facilitated the delivery of existing services [31,37,42,45,46,48,49,55,57,58] or development of new services [43,44,52]. The types of telehealth employed varied from video calls [52] or phone consultations [37,38,42,43,45,46,48,53,54,55] to a combination of phone, video, and texts [15,31,49,51,57,58].

Telehealth was employed as part of oncology services redesigned to ensure continuity of care and reduce risk of COVID-19 transmission [33,34,36,37,41,47,56]. Included in this were efforts to evaluate patients’ side effects/symptoms, avoid unnecessary hospital visits post-surgery [39], and reduce outpatient department workloads during the pandemic [38]. Where available, telehealth facilitated consultations for a variety of activities including, for patients seeking information regarding their oncological treatments, symptom management and replenishing opioid medications [51] or post-surgery to evaluate patients’ side effects [39]. In one instance, telehealth was employed to deliver tobacco treatment for tobacco-dependent cancer patients during the pandemic in New York City, which resulted in higher attendance and increased completion odds compared to in-person visits [42].

3.3. Satisfaction with Telehealth

The review demonstrates the rapid uptake of telehealth overall, and many studies found a high satisfaction rate amongst patients, caregivers, and clinicians [32,43,48,50,51,52,53,55,59]. Some patients expressed the desire to continue telehealth visits in the future [37,50,54,55]. Several studies outlined the advantages of using telehealth, which included increased access for patients and their families with regards to attendance at appointments [42,49,52,54] and decreased waiting lists [49]. Several authors suggested telemedicine was feasible given the circumstances of the pandemic, as it minimises disruptions to care and reduces patient risk of COVID-19 exposure [42,44,46,49,51,58], including avoiding visits to emergency departments [54] and saved time and costs from the hospital’s perspective [37,61]. Moreover, from a patient’s perspective, telehealth reduced travel time and expenses and increased convenience [45,54,55,58,61].

However, some patients preferred in-person visits and had no desire to continue telemedicine in the future, especially for staging results or treatment decisions [55,57]. Some studies highlight concerns about the accuracy and adequacy of virtual examinations (Canada [49] and Italy [60]) and their inconsistent use [31]. Others highlight that telehealth was not a substitute for treatment; for example, the use of telehealth did not mitigate the reductions in diagnosis and surgery (USA [65]). From the patients’ perspective, concerns about access barriers were also discussed. These included technical difficulties with internet access [42,46,53,54,64], costs of technologies/hardware [63], and communication barriers [49]. Several studies reported that telemedicine was less feasible for older patients as they tended to encounter more difficulties with technology [31,42,53,54,55]. Moreover, for specific activities such as genetic testing, requiring at-home sampling non-adherence was high [45]. Patient access barriers associated with telehealth were reported in developing economies such as network issues in India [64] and Brazil [46], and costs of technologies in Brazil [63]. Nevertheless, some institutions in developed countries also had access and adoption issues (USA, [65]) and concerns regarding the financial sustainability of providing telehealth (USA, [31]).

The review suggests some cancer patients and caregivers were very satisfied with telehealth and were comfortable using it as it offered them “support and connectedness” (India, [50], helped cope with worries [49], and reduced distress [53]. However, these favourable experiences were not universal and for some, the switch to telehealth was associated with higher levels of cancer worry and feelings of isolation (USA, [62]; Canada [49]). While some patients indicated a desire to continue with telehealth [37,55] and even expressed their willingness to pay for telehealth service in the future (India [50]), others indicated they were not inclined to continue using it. This was the case especially for staging results and treatment decisions [57], or it was only seen as a temporary measure until post-lockdown when the clinics reopened [35]. However, even those who were interested in continuing telehealth indicated a blend of telehealth and in-person visits is most desirable and suggested avoiding telehealth when providing results or prognoses [55]. As well as clinical appropriateness, adherence could become an issue for online course/programme delivery when COVID-19 restrictions are removed and people are no longer working from home [42]. To facilitate successful future virtual care, several factors should be considered. For example, appointments need to be scheduled in a pragmatic and logical way; with suitable detailed instructions, to manage expectations; with sufficient time for questions and with a cautious approach to self-care [49].

4. Discussion

This systematic review focused on the economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients and the rapid expansion of telehealth services emerged as a key theme in response to the pandemic. Use of telehealth during the pandemic was particularly important for cancer patients and survivors who, due to their weakened immune system, were at greater risk of contracting infections and of developing more severe infections compared to the general population [3]. So, employing telehealth along with other public health guidelines and initiatives provided protection for this cohort. Despite the adoption of telehealth and other efforts, most healthcare systems paused essential inpatient and outpatient services during phase one of the pandemic. The result was missed or delayed cancer diagnosis and disrupted treatment leading to worsening health outcomes, quality of life, and in some cases mortality [29].

In the study, we briefly outlined the benefits and implications of telehealth with the purpose of mitigating the impact of the pandemic through reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure for cancer patients and their families. The results showed that telehealth adoption seemed to “bolster” the delivery of healthcare services, providing a level of continuity of care during this highly uncertain time. However, it is evidenced that a “one size fits all” approach to telehealth is not appropriate to support the delivery of essential healthcare services for cancer patients. Albeit for its continued use, consideration of constraints is warranted to determine which patients and services may be successfully enabled by telehealth.

From an economic perspective, there were costs and benefits associated with the adoption of telehealth. Healthcare professionals’ emergency response to maintaining a line of communication with cancer patients and their families meant pragmatic decisions were made to ensure some level of service was provided at a time when patient protection against COVID-19 infection was a priority. Telehealth emerged as one key valuable tool available to healthcare providers, in an extremely limited toolkit of possible responses to the pandemic. During the early phase of the pandemic, for some service providers, telehealth adoption consisted of using existing available technologies such as telephone consultations and video calls [38]. This was the case for approximately 61% of the studies presented here. For the remainder, there are costs associated with setup and maintenance of telehealth technology [53], including data protection. Following the early phase, strategic investments were made in hardware and software solutions to support the delivery of telehealth beyond the initial emergency response [66].

The cost of telehealth to national health systems, healthcare professionals, patients, and their families differs across jurisdictions, owing to variations in financial reimbursement models for health services. While some articles included in this review briefly consider cost in terms of reducing the cost of travel, access, and quality of care for cancer patients, future research could establish the time and cost savings for cancer patients accessing telehealth services. While studies indicated that patients were prepared to pay for telehealth services in the future [51], to ensure sustainability going forward, as telehealth shifts to becoming more embedded as part of routine services, appropriate reimbursement mechanisms will be necessary. This will require research to move beyond traditional approaches to support this emerging model of care delivery to answer questions such as: who will pay, where, and for what services? The latter could also consider potential savings arising from fewer appointment “no-show” incidents.

Patients’ access to essential services via telehealth reduced the need for face-to-face interactions, when were stretched to capacity with COVID-19 patients or in anticipation of a surge of COVID-19 patients needing specialist care. The availability of telehealth services minimised the need for emergency admissions to acute services [65]. Reductions in non-attendance [42,49,52,54] also enabled the latter. Telehealth enabled the continuity of multidisciplinary decision-making for cancer patients with “virtual tumour boards” bringing together a range of medical disciplines for discussions on how to best care for a patient with cancer [33,35,56].

Telehealth provides beneficial spillovers for patients and their families. These include reduced travel time and efficiency gains with reduced waiting times from performing consultations from home with a loved one present. However, there are also costs and access barriers, including network issues and technology costs [46,63,64], which disproportionately impact vulnerable groups. The latter can include older adults [31,42,53,54,55], those with poorer literacy skills, and those from lower economic backgrounds. Additionally, for those with cancers at sites which could impact cognition and other functions, for example, brain tumours, telehealth may not be as beneficial.

From a social perspective, while some cancer patients and their families extolled the benefits of telehealth, the pandemic exacerbated existing challenges around equitable digital access and utilisation of healthcare services. This “digital divide” has disproportionately affected vulnerable patient populations, for example older groups [53]. In addition, the attitude of staff, patients, and their families to the adoption and diffusion of telehealth technology differs, owing to several factors. Perceived skill gaps and lack of available hardware, software, internet access, and technical support can impact successful telehealth adoption. If telehealth is retained in the delivery of routine oncology services, understanding the adoption barriers and facilitators is necessary to ensure that the lessons learned are not left behind. Researchers, healthcare decision makers, and policy makers should explore new opportunities to tackle these challenges. One option is to assess the potential of telehealth hubs as an approach to centralising telehealth services, thus overcoming issues relating to access and support.

Finally, from a psychological perspective, the switch to telehealth for some was associated with higher levels of cancer worry and feelings of isolation [49,62], whereby the lack of in-person access created mental health strain for patients and survivors who were forced to solely rely on telehealth communication. For some patients, this outweighs the comfort and support benefits of being at home. While this review only captured the first wave of COVID-19, if oncology telehealth were to continue, efforts to minimise these adverse psychological impacts are warranted. A user-centred approach is necessary to design and develop telehealth that supports quality patient-healthcare professional communication and relationship development in a virtual environment. New opportunities to co-create telehealth services should be identified to ensure the design of usable and accessible services for cancer patients. This is particularly important when a patient is newly referred to a service. Additional research should explore clinical workflows and opportunities to incorporate telehealth to complement existing services, so patients experience the benefits that were accrued during COVID-19 and healthcare professionals are formally and explicitly allocated the time necessary to deliver quality personalised telehealth services. This research should include key efficiency and effectiveness indicators of cancer services.

New telehealth solutions should be designed to adapt to the changing needs and preferences of patients and their families. For example, appointments need to be scheduled appropriately and with sufficient time to allow for questions and consideration of information with appropriate health care practitioners and sufficient support information [49]. Likewise, patients’ preferences for format matter must be considered as well, for example, telephone versus video calls. Moreover, the types of consultations for which telehealth is used need further exploration and consideration. For example, telehealth is suitable for some settings and services, such as counselling [42,47], replenishing medications, and for patients seeking information regarding their oncological treatments [51]. However, it is unsuitable for others, such as staging results and treatment decisions [55,57], which carry a significant psychological burden which could be exacerbated by telehealth. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques could be used to predict a patient’s changing healthcare needs, incorporating factors such as their living arrangement and ability to communicate in a private space, their mental and spiritual wellbeing, etc.

A more intelligent blended approach to designing services that incorporate both telehealth and traditional face-to-face consultations may be needed to ensure quality of care and positive patient outcomes. These findings correspond with existing research assertions that telehealth is not a panacea. While telehealth is not a universal solution to delivering cancer services during a pandemic or beyond, it facilitated continuity of care during a highly uncertain time for some.

5. Conclusions

This paper provides a systematic literature review to identify the economic, social, health, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients during wave one, with the availability of telehealth services for cancer patients emerging as a key theme. This review is not without limitations. Most of the studies included in the review are single institutional studies, where telehealth was employed for a variety of reasons in various settings, with small sample sizes, so wide-scale adoption and satisfaction of telehealth cannot be determined. Furthermore, the methodologies employed yield potential biases. These include selection biases arising from convenience sampling [44] and observation bias owing to data collection methods [52]. However, some studies lacked outcome data [15], where collected self-reported data were relied upon [44] and validated instruments were lacking [43].

The time and scope of this review means only the first wave of the pandemic was assessed. While some initiatives have persisted and, in many cases, helped to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on adult cancer patients, it is likely other temporary measures have waned. This study reveals that there have been telehealth successes and failures; the lessons learned present a significant opportunity to reimagine the delivery of healthcare, leveraging telehealth as a complement rather than a substitute. This approach will enable healthcare systems globally to future-proof their operations by better preparing for unique unexpected disruptive events such as pandemics and natural disasters.

Appendix A. Quality Review

I PREVALENCE STUDIES [27]

| |||||||||

| Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 |

| Atreya et al. (2020) [50] | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Alterio et al. (2020) [34] | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Biswas et al. (2020) [51] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC |

| de Marinis et al. (2020) [36] | NA | NA | NA | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Frey et al. (2020) [62] | N | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC |

| Kwek et al. (2021) [47] | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Mahl et al. (2020) [63] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | UC |

| Merz et al. (2021) [43] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | UC |

| Mitra et al. (2020) [64] | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Patt et al. (2021) [53] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | UC |

| Patt et al. (2020b) [54] | Y | NA | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC |

| Rodler et al. (2020) [57] | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Sawka et al. (2021) [37] | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC |

| Smrke et al. (2020) [55] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Somani et al. (2020) [58] | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Sonagli et al. (2021) [46] | UC | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA |

| Zuliani et al. (2020) [60] | Y | UC | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC |

II CROSS SECTIONAL ANALYTICAL STUDIES [27]

| ||||||||

| Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 |

| Goenka et al. (2021) [31] | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kamposioras et al. (2020) [59] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kotsen et al. (2021) [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lonergan et al. (2020) [15] | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

III QUALITATIVE STUDIES [27]

| ||||||||||

| Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

| Lopez et al. (2021) [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Wu et al. (2020) [52] | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

IV COHORT STUDIES [27]

| |||||||||||

| Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

| Akhtar et al. (2021) [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Akuamoa-Boateng et al. (2020) [33] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Araujo et al. (2020) [56] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Brenes Sanchez et al. (2021) [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Caravatta et al. (2020) [35] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | UC | Y | Y | UC | Y |

| Clark et al. (2021) [48] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Earp et al. (2020) [40] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Maganty et al. (2020) [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Narayanan et al. (2021) [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Patt et al. (2020a) [65] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Romani et al. (2021) [32] | UC | Y | NA | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shannon et al. (2020) [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Wai et al. (2021) [41] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| V Cost Analysis: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC)-List (Evers, Goossens, De Vet, Van Tulder, and Ament, 2005) [28] | Parikh et al. (2020) [61] |

| 1. Is the study population clearly described? | Y |

| 2. Are competing alternatives clearly described? | Y |

| 3. Is a well-defined research question posed in answerable form? | Y |

| 4. Is the economic study design appropriate to the stated objective? | Y |

| 5. Is the chosen time horizon appropriate to include relevant costs and consequences? | Y |

| 6. Is the actual perspective chosen appropriate? | Y |

| 7. Are all important and relevant costs for each alternative identified? | Y |

| 8. Are all costs measured appropriately in physical units? | Y |

| 9. Are costs valued appropriately? | Y |

| 10. Are all important and relevant outcomes for each alternative identified? | NA |

| 11. Are all outcomes measured appropriately? | NA |

| 12. Are outcomes valued appropriately? | NA |

| 13. Is an incremental analysis of costs and outcomes of alternatives performed? | NA |

| 14. Are all future costs and outcomes discounted appropriately? | NA |

| 15. Are all important variables, whose values are uncertain, appropriately subjected to sensitivity analysis? | Y |

| 16. Do the conclusions follow from the data reported? | Y |

| 17. Does the study discuss the generalisability of the results to other settings and patient/client groups? | N |

| 18. Does the article indicate that there is no potential conflict of interest of study researcher(s) and funder(s)? | Y |

| 19. Are (a) ethical and (b) distributional issues discussed appropriately? | (a) N (b) Y |

| N = No, NA = Not applicable, UC = unclear, Y = Yes. | |

Appendix B. Thematic Overview

| Author | Highly Satisfied with Telehealth/Acceptance | Desire to Continue Telehealth | No Desire to Replace in-Person Visits with Telehealth | Increased Access to Care | Increased Use of Telehealth | Maintenance of Increased Attendance/Engagement | Challenges | TELEHEALTH Feasible |

| Akhtar et al. (2021) [38] | ✓ | |||||||

| Akuamoa-Boateng et al. (2020) [33] | ✓ | |||||||

| Alterio et al. (2020) [34] | ✓ | |||||||

| Araujo et al. (2020) [56] | ✓ | |||||||

| Atreya et al. (2020) [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Biswas et al. (2020) [51] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Brenes Sánchez et al. (2021) [39] | ✓ | |||||||

| Caravatta et al. (2020) [35] | ✓ | |||||||

| Clark et al. (2021) [48] | ✓ | |||||||

| De Marinis et al. (2020) [36] | ✓ | |||||||

| Earp et al. (2020) [40] | ✓ | |||||||

| Frey et al. (2020) [62] | ✓ | |||||||

| Goenka et al. (2021) [31] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Kamposioras et al. (2020) [59] | ✓ | |||||||

| Kotsen et al. (2021) [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kwek et al. (2021) [47] | ✓ | |||||||

| Lonergan et al. (2020) [15] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lopez et al. (2021) [49] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Maganty, et al. (2020) [30] | ✓ | |||||||

| Mahl et al. (2020) [63] | ✓ | |||||||

| Merz et al. (2021) [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Mitra, et al. (2020) [64] | ✓ | |||||||

| Narayanan et al. (2021) [44] | ✓ | |||||||

| Parikh, et al. (2020) [61] | ✓ | |||||||

| Patt et al. (2020a) [65] | ✓ | |||||||

| Patt, et al. (2020b) [54] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Patt et al. (2021) [53] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Rodler et al. (2020) [57] | ✓ | |||||||

| Romani et al. (2021) [32] | ✓ | |||||||

| Sawka, et al. (2021) [37] | ✓ | |||||||

| Shannon, et al. (2020) [45] | ✓ | |||||||

| Smrke, et al. (2020) [55] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Somani et al. (2020) [58] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sonagli et al. (2021) [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Wai et al. (2020) [41] | ✓ | |||||||

| Wu et al. (2020) [52] | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Zuliani et al. (2020) [60] | ✓ |

Appendix C. Description of Review Papers

|

Author Year

Country |

Aim |

Study Design

Sample Size, Age |

Context and Setting

Study Timeframe |

Data Source |

Data Collection

Data Analysis |

Results |

| Akhtar et al. (2021) [38] India | To describe the hospital experience during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic including the functioning of the department, clinical outcomes, problems faced by patients, and lessons learned | Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital COVID-19 period: April to Sept 2020. Pre-COVID-19 period: April to Sept, 2019. |

Secondary data; hospital record database Primary data; questionnaire |

|

|

| Akuamoa-Boateng et al. (2020) [33] Germany | To compare hospital management of 2019 and 2020 |

Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: 18/03/19–10/05/19 COVID-19 period: 16/03/20–8/05/20 |

Secondary data; hospital records |

|

|

| Alterio et al. (2020) [34] Italy | To report organisation strategies at a radiation oncology department, focusing on procedures and scheduling (i.e.: delays, interruptions) | Retrospective N = 1 institution N = 43 patients 57–74 years |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: 01/03 to 30/04/19 COVID-19 period: 01/03 to 30/04/20 |

Secondary data; Electronic medical charts |

|

|

| Araujo et al. (2020) [56] Latin America | To evaluate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patient volume in a cancer centre in an epidemic of the pandemic | Provider Retrospective N = 1 institution NA | Hospital Pre-COVID-19: Mar–May 2019 COVID-19 period: Mar–May 2020 |

Secondary data; electronic health record database |

|

|

| Atreya et al. (2020) [50] India | (1) To assess changes in the hospital-based practice of palliative care during the pandemic (2) Patient/caregivers perception about the provision of palliative telehealth services (which were in place since 2014) |

Patient & caregivers Cross-sectional N = 50 >18 years old |

Hospital 01/01–19/05/20 |

Primary data; interview Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Biswas et al. (2020) [51] India | (1) To assess expansion of telemedicine service in the palliative unit in the department of oncology (2) To assess patient satisfaction |

Patient Prospective N = 314 Adults |

Hospital 25/03/–13/05/20 |

Primary data; Telephone calls | Telephone calls were recorded to collect data on:

|

|

| Brenes Sanchez et al. (2021) [39] Spain | To analyse the management of patients with breast cancer during the pandemic | Patients Retrospective observational N = 57 patients NA |

Hospital Group A: 15/03/20–21/04/20 Group B: 22/04/20–06/05/20 |

Primary data; questionnaire Secondary data; hospital data | Telephone questionnaire using:

|

|

| Caravatta et al. (2020) [35] Italy | To report the experience and organisational planning of radiotherapy during the first two phases of the emergency, lockdown phase 1 and post-lockdown phase II | Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: 09/03–04/05/19 COVID-19 period: 09/03–04/05/20 Lockdown I: 09/03 –04/05/20 Lockdown II: 25–31/05/20 |

Secondary data; hospital records |

|

|

| Clark et al. (2021) [48] England | To assess the national impact of COVID-19 on the prescribing of systemic anti-cancer treatment | Retrospective NA NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: September, 2019, to February, 2020. COVID-19 period: April–June, 2020 |

Secondary data; electronic health registry system |

|

Uptake of teleconsultations at national level. Initially the number of registrations of new systemic anti-cancer treatments decreased but average monthly registrations had exceeded pre-pandemic levels by June, 2020, due to other risk-reducing measures such as telephone consultations, facemasks, and physical distancing. |

| De Marinis et al. (2020) [36] Italy | To prove that such proactive management allowed for the minimisation of contagion among patients with lung cancer through the maximisation of preventive measures | Patient and provider Prospective N = 1 institution N = 477 patients, 23–89 years old |

Hospital 1 month; March 2020 |

Secondary data; hospital records |

|

|

| Earp et al. (2020) [40] USA | Examine the early effect of hospital and state-mandated restrictions on orthopaedic surgery department | Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital COVID-19 period: 16/03–12/04/20 Study period: 14/02/–15/03/20 Control period: 16/03–12/04/19 |

Secondary data; Billing database |

|

Surgical department:

|

| Frey et al. (2020) [62] USA | (1) To evaluate the quality of life (QoL) of women with ovarian cancer during the pandemic (2) Evaluate the effects of the pandemic on cancer-related treatment. |

Cross-sectional N = 555 20–85 years old |

Web-based 30/03–13/04/20 |

Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Goenka et al. (2021) [31] USA | Review implementation (1) Patient access to care (2) Billing implication |

Provider Observational N = 1 institution 22–93 years old |

Hospital 01/01–01/05/20 |

Secondary data; hospital data |

|

|

| Kamposioras et al. (2020) [59] England | (1) To investigate the perceptions of service changes imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. (2) To identify the determinant of anxiety in patients with colorectal cancer |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 143 ≥18 years |

Hospital 18/05–01/07/20 |

Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Kotsen et al. (2021) [42] USA | To examine the effect of rapid scaling to tobacco treatment telehealth for tobacco-dependent cancer patient | Patient and provider Retrospective N = 418 Adults |

Hospital: 01/01–30/04/20 |

Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Kwek et al. (2021) [47] Singapore | To describe outpatient attendance and treatment caseloads during COVID-19 compared with the corresponding period pre-COVID-19. | Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital COVID-19 period 03/02–23/05/20 Pre-COVID-19 period 03/02–23/05/19 |

Secondary data; health records |

|

|

| Lonergan et al. (2020) [15] USA | To analyse the change in video visit volume | Provider Cross-sectional N = 17 departments NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID period: 01/01–14/03/20 Post-COVID-19 period: 15/03– 05/04/20 |

Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Lopez et al. (2021) [49] Canada | To describe the adaptions made to implement virtual cancer rehabilitation at the onset of coronavirus disease 2019 | Multi-method N = 12 patients, N = 12 providers Adults |

Hospital 16/03–12/06/20 |

Primary data; interviews Secondary data; hospital data |

|

Re: Meeting support needs: sense of reassurance and felt supported, helped cope with worries, some felt isolated by telemedicine. Re: Confidence with assessment and care plan: lack of in-person examination, relying on self-report/assessment of patients, worried about accuracy of describing symptoms, agreed video better than telephone visits, both agreed preference for an initial in-person assessment |

| Maganty, et al. (2020) [30] USA | To evaluate differences in patient populations being evaluated for cancer before and during the COVID-19 pandemic | Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19 period: 3–5 months prior to 17/03/20 COVID-19 period: 3 to 5 months after 17/03/20 |

Secondary data; electronic health records |

|

|

| Mahl et al. (2020) [63] Brazil | To evaluate delays in care for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) in post-treatment follow-up or palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e.: self-perception of anxiety or sadness, fear of COVID-19 infection, cancer-related complications during social isolation, self-medication, diagnosis of COVID-19, and death between patients with and without delayed cancer care | Cross-sectional N = 1 institution N = 31 patients Adults |

Hospital 01/01/–30/07/20 |

Primary data; interview Secondary data; medical records |

|

|

| Merz et al. (2021) [43] Italy | To assess how breast cancer survivors perceived electronic medical record-assisted telephone follow-up | Prospective N = 137 34–89 years old |

Hospital 09/03–02/06/20 |

Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Mitra, et al. (2020) [64] India | To study the challenges faced by cancer patients in India during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional N = 36 ≥18 years old |

Hospital 01–15/05/20 |

Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Narayanan et al. (2021) [44] USA | To report the feasibility of conducting integrative oncology (IO) physician consultations via telehealth in 2020 compared to the same period of the previous year. | Retrospective N = 1352 ≥18 years old |

Hospital Cohort 1 (in person): 21/04–21/10/19 Cohort 2 (telehealth): 21/04–21/10/20 |

Primary data; questionnaire Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Parikh, et al. (2020) [61] USA | To evaluate the overall change in resource use associated with the transition to telemedicine in a radiation oncology department | Descriptive N = 1 patient NA |

Hospital Using a patient undergoing 28-fraction treatment course, exact timeframe not specified. |

Primary data; interviews and surveys of personnel |

|

|

| Patt et al. (2020a) [65] USA | To gain insight into the impact of COVID-19 on the US senior cancer population | Retrospective NA NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: March–July 2019 COVID-19 period: March–July 2020 |

Secondary data; database |

|

|

| Patt, et al. (2020b) [54] USA | (1) To describe onboarding and utilisation of telemedicine across a large statewide community oncology practice (2) To evaluate trends, barriers, and opportunities in care delivery during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic |

Cross-sectional N = 640 clinicians at 221 sites of service. N = 80 survey NA |

Community setting February to April 2020 Survey: August 2020 |

Secondary data; telehealth platform Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Patt et al. (2021) [53] USA | To assess the: (1) Implementation of multidisciplinary telemedicine in community oncology: (2) Level of satisfaction in providers and patients (3) Changes in clinic operations (4) Opportunities and barriers |

Cross-sectional N = 640 clinicians at 221 sites of service N = 34 survey NA |

Community setting March–September, 2020 |

Secondary data; telehealth platform Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Rodler et al. (2020) [57] Germany | To determine patients’ perceptions on adoption of telehealth as a response to the pandemic and its sustainability in the future | Patient Cross-sectional N = 92 33–88 years old |

Hospital 1 week |

Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Romani et al. (2021) [32] Canada | (1) To examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the operation of satellite radiation oncology facility run completely virtually from April to May 2020 (2) Patient satisfaction |

Patient Retrospective observational N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19 period April–May 2019 COVID-19 period April–May 2020 |

Secondary data; health records Primary data; survey |

|

|

| Sawka, et al. (2021) [37] Canada | Describe the management of small low-risk papillary thyroid cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic | Prospective observational N = 181 >18 years old |

Hospital 12/03–30/10/20 |

Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Shannon, et al. (2020) [45] USA | To determine how visit and genetic testing volume was impacted by new telephone genetic counselling and home testing. | NA Observational N = 1 institution NA |

Hospital 6 weeks |

Secondary data; electronic medical records, log entries |

|

|

| Smrke, et al. (2020) [55] UK | To evaluate the impact of telemedicine on patients, clinicians, care delivery | Patient and provider Cross-sectional N = 316 >18 years old |

Hospital 23/03–24/04/20 |

Primary data; survey Secondary data; electronic medical records |

|

|

| Somani et al. (2020) [58] UK | To assess outpatient and telemedicine (phone and video) volume during the pandemic. | NA Observational N = 1 institution NA | Hospital 13/03–07/05/20 |

Secondary data; hospital data |

|

|

| Sonagli et al. (2021) [46] Brazil | To demonstrate how the use of telemedicine was an efficient tool to maintain outpatient appointments for breast cancer patients follow-up and surveillance | Patient Retrospective cohort N = 87 >18 years old |

Hospital 05/06–10/10/20 |

Secondary data; hospital data |

|

|

| Wai et al. (2020) [41] USA | To understand how the surgical care of head and neck cancer patients was affected, specifically assessing surgical case volume, time to care, safety of the patients, and clinical team | Retrospective N= 1 institution NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: 16/03–13/04/19 COVID-19 period: 16/03–16/04/20 |

Secondary data; medical notes and database |

|

|

| Wu et al. (2020) [52] Taiwan | To assess smartphone-enabled telehealth model for palliative care family conferences | Patient and family members Pilot observational N = 14 (13 cancer patients, 1 stroke patient) >18 years old |

Hospital February to April 2020 |

Primary data; Discussion |

|

|

| Zuliani et al. (2020) [60] Italy | To analyse how organisational changes related to COVID-19 have impacted: (i) Volume of oncological activity (compared to same period of 2019) (ii) Hospital admissions of “active” oncological patients for SARS-CoV-2 |

Retrospective N = 1 institution N = 241 surveyed NA |

Hospital Pre-COVID-19: 01/01–31/03/19 COVID-19 period: 01/01–31/03/20 |

Secondary data; health records Primary data; questionnaire |

|

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.M., A.K. and F.J.D.; methodology, A.M., A.K. and F.J.D.; validation, A.M., A.K., A.L. and F.J.D.; formal analysis, A.M. and A.L.; investigation, C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, C.H., A.K. and F.J.D.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Table 2 and [29].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the MSD Global Oncology Policy grant programme.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Basu A., Kuziemsky C., de Araújo Novaes M., Kleber A., Sales F., Al-Shorbaji N., Flórez-Arango J.F., Gogia S.B., Ho K., Hunter I., et al. Telehealth and the COVID-19 pandemic: International perspectives and a health systems framework for telehealth implementation to support critical response. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2021;30:126–133. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1726484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: A systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simcock R., Thomas T.V., Estes C., Filippi A.R., Katz M.S., Pereira I.J., Saeed H. COVID-19: Global radiation oncology’s targeted response for pandemic preparedness. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020;22:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zonneveld M., Patomella A.-H., Asaba E., Guidetti S. The use of information and communication technology in healthcare to improve participation in everyday life: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020;42:3416–3423. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1592246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanlon P., Daines L., Campbell C., McKinstry B., Weller D., Pinnock H. Telehealth interventions to support self-management of long-term conditions: A systematic metareview of diabetes, heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19:e6688. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards L., Thomas C., Gregory A., Yardley L., O’Cathain A., Montgomery A.A., Salisbury C. Are people with chronic diseases interested in using telehealth? A cross-sectional postal survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16:e3257. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Cathain A., Drabble S.J., Foster A., Horspool K., Edwards L., Thomas C., Salisbury C. Being human: A qualitative interview study exploring why a telehealth intervention for management of chronic conditions had a modest effect. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18:e163. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford N., Caffery L., Smith A. Correction: Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: A systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural. Remote Health. 2016;16:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colucci M., Baldo V., Baldovin T., Bertoncello C. A “matter of communication”: A new classification to compare and evaluate telehealth and telemedicine interventions and understand their effectiveness as a communication process. Health Inform. J. 2019;25:446–460. doi: 10.1177/1460458217747109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeRouge C.M., Garfield M.J., Hevner A.R. Patient perspectives of telemedicine quality. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2015;9:25. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S67506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindgreen A. Corruption and unethical behavior: Report on a set of Danish guidelines. J. Bus. Ethics. 2004;51:31–39. doi: 10.1023/B:BUSI.0000032388.68389.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moffatt J.J., Eley D.S. Barriers to the up-take of telemedicine in Australia—A view from providers. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:116–121. doi: 10.22605/RRH1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade V.A., Eliott J.A., Hiller J.E. Clinician acceptance is the key factor for sustainable telehealth services. Qual. Health Res. 2014;24:682–694. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steindal S.A., Nes A.A.G., Godskesen T.E., Dihle A., Lind S., Winger A., Klarare A. Patients’ experiences of telehealth in palliative home care: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e16218. doi: 10.2196/16218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonergan P.E., Iii S.L.W., Branagan L., Gleason N., Pruthi R.S., Carroll P.R., Odisho A.Y. Rapid Utilization of Telehealth in a Comprehensive Cancer Center as a Response to COVID-19: Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e19322. doi: 10.2196/19322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.March C.A., Flint A., DeArment D., Gilliland A., Kelly K., Rizzitano E., Chrisman A., Muzumdar R.H., Libman I.M. Paediatric diabetes care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned in scaling up telemedicine services. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2021;4:e00202. doi: 10.1002/edm2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Reilly D., Carroll H., Lucas M., Sui J., al Sendi M., McMahon D., Darwish W., McLaughlin R., Khan M.R., Sullivan H.O. Virtual oncology clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021;190:1295–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11845-020-02489-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell R.E., Henstenburg J.M., Cooper G., Hollander J.E., Rising K.L. Patient perceptions of telehealth primary care video visits. Ann. Fam. Med. 2017;15:225–229. doi: 10.1370/afm.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdez R.S., Rogers C.C., Claypool H., Trieshmann L., Frye O., Wellbeloved-Stone C., Kushalnagar P. Ensuring full participation of people with disabilities in an era of telehealth. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021;28:389–392. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bator E.X., Gleason J.M., Lorenzo A.J., Kanaroglou N., Farhat W.A., Bägli D.J., Koyle M.A. The burden of attending a pediatric surgical clinic and family preferences toward telemedicine. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015;50:1776–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballantyne M., Benzies K., Rosenbaum P., Lodha A. Mothers’ and health care providers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to attendance at C anadian neonatal follow-up programs. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41:722–733. doi: 10.1111/cch.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusinko C. IT responses to COVID-19: Rapid innovation and strategic resilience in healthcare. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020;37:332–338. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2020.1820637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drerup B., Espenschied J., Wiedemer J., Hamilton L. Reduced no-show rates and sustained patient satisfaction of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed. e-Health. 2021;27:1409–1415. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albarrak A.I., Mohammed R., Almarshoud N., Almujalli L., Aljaeed R., Altuwaijiri S., Albohairy T. Assessment of physician’s knowledge, perception and willingness of telemedicine in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutton B., Catala-Lopez F., Moher D. The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA. Med. Clin. 2016;147:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies K.S. Formulating the evidence based practice question: A review of the frameworks. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2011;6:75–80. doi: 10.18438/B8WS5N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.JBI Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. [(accessed on 10 December 2021)]. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- 28.Evers S., Goossens M., de Vet H., van Tulder M., Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2005;21:240–245. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy A., Lawlor A., Kirby A., Drummond F.D. A Systematic Review of the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer Patients and Survivors from an Economic and Social Perspective. University Colelge Cork; Cork, Ireland: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maganty A., Yu M., Anyaeche V.I., Zhu T., Hay J.M., Davies B.J., Yabes J.G., Jacobs B.L. Referral pattern for urologic malignancies before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2020;39:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goenka A., Ma D., Teckie S., Alfano C., Bloom B., Hwang J., Potters L. Implementation of Telehealth in Radiation Oncology: Rapid Integration during COVID-19 and Its Future Role in Our Practice. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2021;6:100575. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romani C., Conlon M., Oliver M., Leszczynski K., Hunter M., Lam K., Spadafora S., Pearce A. The Operation of Canada’s Only Virtually Operated Radiation Oncology Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2021;6:100634. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.100634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akuamoa-Boateng D., Wegen S., Ferdinandus J., Marksteder R., Baues C., Marnitz S. Managing patient flows in radiation oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Reworking existing treatment designs to prevent infections at a German hot spot area University Hospital. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2020;196:1080–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00066-020-01698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alterio D., Volpe S., Marvaso G., Turturici I., Ferrari A., Leonardi M.C., Lazzari R., Fiore M.S., Bufi G., Cattani F., et al. Head and neck cancer radiotherapy amid COVID-19 pandemic: Report from Milan, Italy. Head Neck. 2020;42:1482–1490. doi: 10.1002/hed.26319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caravatta L., Rosa C., di Sciascio M.B., Scaringi A.T., di Pilla A., Ursini L.A., Taraborrelli M., Vinciguerra A., Augurio A., di Tommaso M., et al. COVID-19 and radiation oncology: The experience of a two-phase plan within a single institution in central Italy. Radiat. Oncol. 2020;15:226. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01670-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Marinis F., Attili I., Morganti S., Stati V., Spitaleri G., Gianoncelli L., del Signore E., Catania C., Rampinelli C., Salè E.O., et al. Results of Multilevel Containment Measures to Better Protect Lung Cancer Patients From COVID-19: The IEO Model. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:665. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawka A.M., Ghai S., Ihekire O., Jones J.M., Gafni A., Baxter N.N., Goldstein D.P., on behalf of the Canadian Thyroid Cancer Active Surveillance Study Group Decision-making in surgery or active surveillance for low risk papillary thyroid cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancers. 2021;13:371. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akhtar N., Rajan S., Chakrabarti D., Kumar V., Gupta S., Misra S., Chaturvedi A., Azhar T., Parveen S., Qayoom S., et al. Continuing cancer surgery through the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic at an academic university hospital in India: A lower-middle-income country experience. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021;123:1177–1187. doi: 10.1002/jso.26419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenes Sánchez J.M., Picado A.L., Crespo M.E.O., Sáenz J.Á.G., Merlo R.M.d., de la Muela M.H. Breast Cancer Management during COVID-19 Pandemic in Madrid: Surgical Strategy. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2021;21:e128–e135. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Earp B.E., Zhang D., Benavent K.A., Byrne L., Blazar P.E. The Early Effect of COVID-19 Restrictions on an Academic Orthopedic Surgery Department. Orthopedics. 2020;43:228–232. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20200624-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wai K.C., Xu M.J., Lee R.H., El-Sayed I.H., George J.R., Heaton C.M., Knott P.D., Park A.M., Ryan W.R., Seth R., et al. Head and neck surgery during the coronavirus-19 pandemic: The University of California San Francisco experience. Head Neck. 2021;43:622–629. doi: 10.1002/hed.26514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotsen C., Dilip D., Carter-Harris L., O’Brien M., Whitlock C.W., de Leon-Sanchez S., Ostroff J.S. Rapid Scaling up of Telehealth Treatment for Tobacco-Dependent Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Outbreak in New York City. Telemed. J. e-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2021;27:20–29. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merz V., Ferro A., Piras E.M., Zanutto A., Caffo O., Messina C. Electronic Medical Record-Assisted Telephone Follow-Up of Breast Cancer Survivors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single Institution Experience. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021;17:e44–e52. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narayanan S., Lopez G., Powers-James C., Fellman B.M., Chunduru A., Li Y., Bruera E., Cohen L. Integrative Oncology Consultations Delivered via Telehealth in 2020 and In-Person in 2019: Paradigm Shift during the COVID-19 World Pandemic. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2021;20:1534735421999101. doi: 10.1177/1534735421999101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shannon K.M., Emmet M.M., Rodgers L.H., Wooters M., Seidel M.L. Transition to telephone genetic counseling services during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Genet. Couns. 2020;30:984–988. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonagli M., Neto R.C., Leite F.P.M., Makdissi F.B.A. The use of telemedicine to maintain breast cancer follow-up and surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021;123:371–374. doi: 10.1002/jso.26327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwek J.W., Chan J.J., Kanesvaran R., Wang M.L.C., Neo P.S.H., Chia C.S., Tham C.K., Chew L.S.T., Tan H.K., Yap S.P., et al. Early Outcomes of a National Cancer Center’s Strategy Against COVID-19 Executed Through a Disease Outbreak Response Taskforce. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021;17:e343–e354. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clark J.J., Dwyer D., Pinwill N., Clark P., Johnson P., Hackshaw A. The effect of clinical decision making for initiation of systemic anticancer treatments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in England: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:66–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30619-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez C.J., Edwards B., Langelier D.M., Chang E.K., Chafranskaia A., Jones J.M. Delivering Virtual Cancer Rehabilitation Programming during the First 90 Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multimethod Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021;102:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atreya S., Kumar G., Samal J., Bhattacharya M., Banerjee S., Mallick P., Chakraborty D., Gupta S., Sarkar S. Patients’/Caregivers’ perspectives on telemedicine service for advanced cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory survey. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2020;26:40–44. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_145_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biswas S., Adhikari S., Gupta N., Garg R., Bharti S., Kumar V., Mishra S., Bhatnagar S. Smartphone-based telemedicine service at palliative care unit during nationwide lockdown: Our initial experience at a tertiary care cancer hospital. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2020;26:31–35. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_161_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Y.-R., Chou T.-J., Wang Y.-J., Tsai J.-S., Cheng S.-Y., Yao C.-A., Peng J.-K., Hu W.-Y., Chiu T.-Y., Huang H.-L. Smartphone-Enabled, Telehealth-Based Family Conferences in Palliative Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Pilot Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e22069. doi: 10.2196/22069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patt D.A., Wilfong L., Toth S., Broussard S., Kanipe K., Hammonds J., Allen V., Mautner B., Campbell N., Dubey A.K., et al. Telemedicine in Community Cancer Care: How Technology Helps Patients With Cancer Navigate a Pandemic. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021;17:e11–e15. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patt D., Wilfong L., Kanipe K., Paulson R.S. Telemedicine for cancer care: Implementation across a multicenter community oncology practice. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2020;26:SP330–SP332. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.88560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smrke A., Younger E., Wilson R., Husson O., Farag S., Merry E., Macklin-Doherty A., Cojocaru E., Arthur A., Benson C., et al. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Care for Rare Cancers. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020;6:1046–1051. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araujo S.r.E.A., Leal A., Centrone A.F.Y., Teich V.D., Malheiro D.T., Cypriano A.S., Neto M.C., Klajner S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on care of oncological patients: Experience of a cancer center in a Latin American pandemic epicenter. Einstein. 2020;19:eAO6282. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2021AO6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodler S., Apfelbeck M., Schulz G.B., Ivanova T., Buchner A., Staehler M., Heinemann V., Stief C., Casuscelli J. Telehealth in Uro-oncology Beyond the Pandemic: Toll or Lifesaver? Eur. Urol. Focus. 2020;6:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Somani B.K., Pietropaolo A., Coulter P., Smith J. Delivery of urological services (telemedicine and urgent surgery) during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience and lessons learnt from a university hospital in United Kingdom. Scott. Med. J. 2020;65:109–111. doi: 10.1177/0036933020951932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamposioras K., Saunders M., Lim K.H.J., Marti K., Anderson D., Cutting M., McCool D., Connell J., Simpson L., Hasan J., et al. The Impact of Changes in Service Delivery in Patients with Colorectal Cancer during the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2020;20:e120–e128. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuliani S., Zampiva I., Tregnago D., Casalil M., Cavalierel A., Fumagallil A., Merlerl S., Rival S.T., Rossil A., Zacchil F., et al. Organisational challenges, volumes of oncological activity and patients’ perception during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 epidemic. Eur. J. Cancer. 2020;135:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]