Abstract

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of mutual aid groups were established on social media and operated as platforms through which people could offer or request social support. Considering the importance of Facebook mutual aid groups during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom but also the lack of empirical research regarding the trajectories and types of social support rendered available through the groups, our aims in this paper are threefold; first, to examine the trajectory of social support-related activity during the period between March–December 2020; second, to compare offers and requests of support during the peaks of the first and second waves; third to provide a rich analysis of the types of social support that were offered or requested through the online mutual aid groups. Quantitative findings suggest that online social support activity declined soon after the peak of the first pandemic wave and, at least in Facebook mutual aid groups, did not reach the levels observed during the first wave. Also, the number of offers of support during the first wave was higher compared to offers during the second wave, and similar was the case for requests for support. Additionally, offers for support were higher compared to requests for support during both the first and second waves. Finally, qualitative analysis showed that people used the Facebook mutual aid groups to offer and request various types of practical, emotional, and informational support. Limitations as well as implications of our study are considered.

Keywords: Social support, Social media, COVID-19, Mutual aid, Online groups, Community solidarity

Funding

The research presented here was supported by a UKRI grant (ES/V005383/1).

1. Introduction

Extreme events can have dramatic consequences for those affected, creating new needs, and requiring both resources as well as individual and collective action and support in order to have their negative effects ameliorated. One way in which the negative outcomes of extreme events can be mitigated is through mutual aid and the provision of social support that is often mobilized by emerging communities at the onset of disasters [[1], [2], [3]]. Like other disasters, mutual aid was also abundant at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 4000 mutual aid groups being set up – often online on Facebook or WhatsApp [4,5] – and providing those in need with social support [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. However, mutual aid and the availability of social support do not endure indefinitely and often decline soon after the main impact of the extreme event [1,3,11,12] at a time when people's needs might still remain high. Reports from the context of the COVID-19 pandemic corroborate such observations by showing a decline in volunteers after the first pandemic wave [13] as well as a general reduction in social cohesion [14] and perceptions of unity [15].

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic provides us with the opportunity to expand previous findings in two important ways. First, most previous research has examined patterns of mobilization and deterioration after extreme events such as floods and earthquakes [2,11,16] that are not characterized by multiple waves such as in the case of pandemics like COVID-19. Whether there is a remobilization of social support in subsequent waves is a question that has yet to be addressed. Second, social media can play a key role in extreme events [17]. The widespread use of social media by the public and the ability of some social media platforms such as Facebook to provide a platform for online groups to be set up allowed for rapid mutual aid actions and the bottom-up mobilization of social support. However, how social support activity changes over time, as well as what types of support were offered or requested through online groups specifically in the context of COVID-19 has yet to be examined.

Considering the above, this paper examines the trajectories and types of social support that were mobilized through Facebook mutual aid groups in the United Kingdom. More specifically, our aims are the following: First, to document the trajectories of social support-related activity in Facebook mutual aid groups in the United Kingdom over time. Second, to document the levels of requests and offers of social support in the same groups during the peak of the first and second waves. Third, to provide a qualitative account of the various types of social support that were offered and requested through the groups. Previous research has documented a deterioration of social support over time, which can have a negative impact on mental health [11,16]. A closer investigation and better understanding of how social support is provided through social networks over time can be of vital importance for effective disaster risk reduction.

1.1. The emergence and decline of mutual aid and social support in extreme events

The onset and direct aftermath of extreme events such as hurricanes, floods, or earthquakes among others is often characterized by the rapid rise of disaster communities [[1], [2], [3],11,18]. Previous findings show that in times of crisis, people with [19] or without [18,20] pre-existing bonds can come together in groups and mobilize social support towards those in need. Social support can be defined as “those social interactions or relationships that provide individuals with actual assistance or that embed individuals within a social system believed to provide love, caring, or sense of attachment to a valued social group or dyad” (p. 121) [21] and it can be practical (e.g., tools, money, food), emotional (e.g., compassion, care) or informational (e.g., advice, guidance) [11,22]. Considering the above, it was not surprising when at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic we witnessed communities emerging to support those in need [10,23]. In fact, similar patterns of support mobilization have been observed across a range of epidemic and pandemic incidents throughout history [24].

To protect against the impact of the pandemic and to reduce the risk of infection due to increasing numbers of reported cases of COVID-19, in March 2020 the United Kingdom's government implemented restrictions in movement and introduced a range of protection measures including mask-wearing, ‘shielding’ (for those who were vulnerable) or self-isolating in cases where people were infected or came in contact with others that might have been infected [25]. However, although adherence to many of these measures (such as handwashing) was high [26], it was reportedly lower on self-isolation [27]. Due to its financial cost (i.e., inability to work and limited compensation) and practical considerations (e.g., the need for shopping, medicine etc.), self-isolation can be difficult without the availability of social support [[28], [29], [30]], the presence of which can facilitate adherence to protection measures [31].

Fortunately, and similarly to previous cases of pandemics [24], at the early stages of the pandemic in the United Kingdom there was a huge increase in the number of people volunteering. Over 750,000 people registered to volunteer with the National Health Service [32] and more than 4000 mutual aid groups emerged [6,8,33] and supported those ‘shielding’ or self-isolating. As we explain in greater detail in the following section, “mutual aid” was the name that these groups used to define themselves. The non-hierarchical, reciprocal and horizontal character of those groups falls within previous definitions of mutual aid as “self-organizing groups where people come together to address a shared health or social issue through mutual support” (p. 391) [34]. Support for those in need among others included delivering goods, distributing food, fundraising, providing information, supporting with pets, or shopping and collecting food, prescriptions, and other necessary items [6,35,36]. Community organizing and volunteering were facilitated by factors such as trust, local knowledge, and social connections [35]. The social support that is rendered available for those in need can be beneficial both materially as well as in terms of increasing expectations of support and having a positive impact on mental wellbeing [22]. However, participating in disaster communities or mutual aid groups can also be beneficial for the participants themselves [34,[37], [38], [39]].

Unfortunately, disaster communities that often appear at the early stages of extreme events are typically short-lived [3,11]. Fritz [1] and Fritz and Williams [12] argue that such a decline occurs because of the absence of a persistent threat to be experienced collectively and a subsequent process of differentiation that characterizes the return to everyday life. Empirical findings [40] from the context of flooding show that emergent community identity declined for a range of reasons. For example, minority groups received unequal treatment from the authorities compared to majority groups which led to a sense of alienation; some survivors experienced an identity shift and stopped perceiving themselves in collective terms; and some survivors felt an absence of common fate originating in the shared experience of a particular stressor. Stallings and Quarantelli also argue that emergent groups often only exist temporarily and that barriers to their existence include factors such as the lack of recognition of their efforts by authorities and other organizations (and the associated visibility and legitimacy that stem from this recognition) [41]. The decline of disaster communities can cause group differences to re-emerge and pre-disaster problems to re-appear [3]. Crucially, the decline of disaster communities can also reduce the availability of social support. Social support might be depleted due to a disruption of the networks that provide it, due to needs exceeding availability, because the providers of support might be victims themselves and not be able to assist others in need, or because of interpersonal conflicts [42]. Kaniasty and Norris [11] similarly argue that when the sense of community that characterizes the early stages of disasters declines, people can come to realize the levels of loss and destruction which can be detrimental for mental health.

1.2. The functions of social media in extreme events

Major disaster risk reduction frameworks advocate for the effective utilization of social media during extreme events. For example, the authors of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction [43] explicitly state that countries should enhance their use of media including social media and communicate crucial information or national policies through online channels. Similarly, the United Kingdom's Community Resilience Development Framework [44] states that official responders should consider voluntary capabilities as parts of the official response to extreme events and ‘engage with communities that might be self-organizing on social media’ (p. 14).

At the onset of COVID-19, social media became platforms for mutual aid groups to be established and operate. The groups' names varied but most often included terms like “COVID action”, “Mutual Aid”, “Isolation Support”, “Virus Support”, “COVID support group”, “helpers” or “pandemic response” among others, often accompanied by the group's location. Websites such as https://www.mutual-aid.co.uk/ 1 or https://covidmutualaid.org/ 2 compiled lists of the mutual aid groups together with advice such as guidance on how to set up, register and maintain a support group or how to access community resources. These lists included the groups' names, websites, or social media pages (e.g., Facebook) and contact details (e.g., e-mail addresses). Users were able to access these webpages to find local groups and access resources, offer or request social support, or have their questions answered. Considering the thousands of self-organized online mutual aid groups that emerged at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to better understand the nature of activities that take place within such groups, providing further empirical evidence to support aforementioned strategies for disaster risk reduction strategies.

Researchers have documented the range of activities that can be performed through social media and their benefits regarding disaster risk reduction [45,46]. The main functions of social media in times of crisis are associated with information dissemination, collective problem solving and decision making, collection and collation of information from various platforms and by the public, offering support to those affected, and receiving victim requests for assistance [47,48]. Similarly, Reuter and Kaufhold [17] provide an extensive review of the role of social media in emergencies via an analysis of published cases of social media in emergencies and patterns of their usage, users, and perceptions. The authors show that social media provide crucial platforms for facilitating collective coordination and mutual aid between citizens that come together in emergent groups. Groups established through social media serve to provide social support, share information, engage in wider relief activities as well as provide the means for people to ask for particular types of support [17]. While various activities are carried out by groups set up via social media platforms, our focus in this paper is on the social support functions enabled through such platforms.

1.3. The present paper

At the onset of extreme events there is often an outpouring of social support [1,3]. Also, online groups often play a crucial role in its mobilization [45,46]. However, as previously highlighted, disaster communities and the support they mobilize can decline over time [3,11]. Considering, the above, our aims in this paper are threefold. First, we aim to examine the trajectories of social support-related activity in online mutual aid groups over time. Drawing on previous research that has highlighted a pattern of decline [3,11] soon after the main impact, we are interested in the trajectory of social support-related activity in extreme events characterized by multiple waves such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and how it is manifested through groups established in social media platforms. Second, considering the documented decline in the availability of social support but also taking into account that needs can remain high, we are interested in examining patterns of offers of and requests for social support at the peak of two pandemic waves. Third, Kaniasty and Norris [11,22] argue that during extreme events people need practical (e.g., tools, resources), informational (knowledge), and emotional support (sympathy, affection). Considering the novelty of the pandemic as well as the major role that social media platforms played in the mobilizing mutual aid, our final aim is to examine the types of social support that social media users requested or offered through online groups.

Our analysis is based on data acquired from online mutual aid groups set up on Facebook. We chose Facebook as a) the links to the online groups were provided on the mutual aid databases that were compiled at the early stages of the pandemic and thus were available to us to join, and b) because we could track both offers and requests for support, providing us an indicator of demand and supply over time.

Ethical clearance for all studies reported in this paper was obtained by the Ethics Review Board of Canterbury Christ Church University (ETH2021-0335). Considering the online nature of groups and the thousands of posts available, obtaining consent from all users was not feasible. However, to protect the anonymity of the users, one condition for obtaining ethical approval was that the data would be fully anonymized and any identifying information such as references to users or people outside the online platforms, locations, other online or offline groups, telephone numbers or email addresses among others would be removed. The anonymized quantitative dataset is available at the following link: https://osf.io/mvzec/?view_only=043c91dcf9694517b2dc7e3dd5ac1160. The qualitative dataset cannot be made publicly available as despite its anonymization, the sheer number of quotes per group can help identify the groups as well as users themselves.

Our results are presented in three parts. First, we present results on the trajectory of social support activity in Facebook mutual aid groups during the first ten months of the pandemic (March–December 2020). Second, we describe differences in requests and offers of support in the mutual aid groups during two specific timepoints, the peak periods of the first and second waves of the pandemic. Third, we present a qualitative analysis of the types of social support that were offered or requested through the groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling population

Various websites such as https://www.mutual-aid.co.uk/or https://covidmutualaid.org/among others compiled lists of the mutual aid groups together with advice such as guidance on how to set up, register and maintain a support group or how to access community resources. These lists included the groups’ names, websites (e.g., Facebook pages) or contact details (e.g., e-mail addresses), and were publicly available (for example, see https://www.policecoders.org/home/covid-19/communities). We identified one such list3 which at the time included over 4000 support groups and through it we collected our samples for the quantitative and qualitative analyses. We will now describe the data collection and data analysis procedures.

2.2. Data collection for quantitative analyses

Our quantitative analyses comprised a) the exploration of the trajectory of social support activity in the online mutual aid groups over time, and b) differences in offers and requests for support at the peaks of the first and second waves respectively.

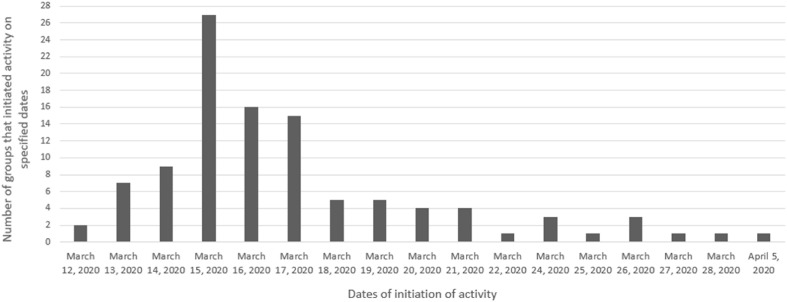

Our goal was to explore approximately 100 groups (around 4%) of the sampling population as this would likely provide a large and diverse yet manageable sample. The final sample consisted of 105 groups. The coders arbitrarily selected groups from the list as long as the groups came from a variety of geographical locations across the United Kingdom. No strict criteria for group size were set but the coders tried to include groups that had both relatively low and high numbers of members. The groups varied in terms of the number of their members (Mean number of members = 794, SD = 1,019, Median = 379, Mode = 2,600, Minimum = 5, Maximum = 5,400, Total = 83,465). First posts in relation to social support in these groups predominantly appeared in the second and third week of March 2020 (Mean = March 17th, Median = March 16th, Mode = March 15th). More specifically, initial social-support related activity ranged between March 12th, 2020 and April 5th, 2020. More details in relation to when social support activity was initiated in the online groups are presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Dates when first social support-related posts first appeared in the sample of Facebook mutual aid groups.

To join a Facebook group, coders had to click a button titled ‘Join Group’. If coders were not accepted in the group or received no response to their request (e.g., in cases that an admin had to approve the request), they selected another group.

First, to explore the trajectory of social support activity over time, we looked at the entire timeline of the Facebook groups. The coding period spanned from the second week of March 2020 when advice regarding self-isolation started being circulated by the government until the first week of December 2020 when the second wave of COVID-19 had stabilized and was at that time in a slow decline until a subsequent steep increase in infections. At the end of the first week of December 2020, the “lockdown” which had been imposed in November also came to an end. Two co-authors (TD and JoK) reviewed the sample in mid-November and early December 2020 and coded the number of posts per week since the creation of the groups. They coded for posts related to social support in general (offered and requested combined) and excluded posts irrelevant to social support (e.g., users sharing music, advertising products, etc.).

Second, in order to examine how requests and offers of support varied between the first two waves of pandemic activity, three co-authors (TD, JoK, and JaK) went over the groups’ timelines in July 2021 and coded for offers and requests for support separately.4 Needs for support can be very high at the peak of extreme events. Thus, rather than examining offers and requests across the entire timeline of groups, we decided to focus on two specific periods which were the peaks of the first and second waves (March 15 – April 14, and October 15 – November 14 respectively), as it is in these periods that the groups would be more active and therefore the demands and offers of support would be at their highest.

2.3. Data collection and analytic procedure for qualitative analysis

To explore the types of social support mobilized in online support groups, one co-author (JaK) selected 10 online groups from the initial list of 105 groups. Considering that some groups had been set up but had no members or activity, the only criterion for inclusion in the qualitative sample was that the groups were active and had members other than the coordinators posting. The sample of 10 groups identified had a total of 15,778 members (Min = 377, Max = 2,600, Mean = 1,577, Median = 1,450, SD = 765).

JaK went through the entire timeline of the groups and coded all specific requests or offers of social support. Through coding we identified 1338 social support-related posts. Subsequently, EN applied a codebook analysis on the data [49] to identify patterns in the types of social support that were requested or provided. Our analysis had a contextual, mapping function since its aim was to identify the range of social support types that were offered or requested through the groups [49]. The first stage of the analysis was to familiarize ourselves with the data through multiple readings. Reading and subsequent coding into themes was informed by the studies by Kaniasty and Norris [11,22] who have categorized social support as practical, informational, or emotional. Reflecting on the results of those 10 groups we observed that the types of support requested or offered (as outlined below) corresponded to this typology.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative results (i): Tracking the trajectory of social support activity in online mutual aid groups

Following the collation of our dataset, we explored how social support-related activity in the online groups changed over time following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data on the number of COVID-19 cases made available by the United Kingdom's government (https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases) we also plotted social support online activity against the COVID-19 cases to examine how social support mobilization progressed as infections increased or decreased over time. As we can see in Fig. 2 , the early stages of the pandemic were characterized by a steep increase in social support-related activity as the reported infection rates also increased.

Fig. 2.

United Kingdom's COVID weekly cases and total number of social support-related posts per week between March and December 2020.

Overall (and as we present in greater detail in Table 1 ), the total number of posts per week spiked in the first weeks of March which coincided with the increase of COVID-19 cases in the United Kingdom. This extremely high level of activity remained during the fourth week of March before sharply declining in late March and April. The gradual decline continued in May, June, July, August, and September 2020. As shown in Fig. 2, the number of cases in the United Kingdom started increasing in late September 2020, but during September no increases in social support posts were observed. The first three weeks of October were also characterized by a similar number of social support posts, whereas the fourth week of October was characterized by an increase and a general increase in the mean number of posts for October as a whole. During November the posts were slightly increased but stable, but these numbers declined in the first week of December. Interestingly though, compared to the first wave where there was a rapid rise of social support activity in Covid mutual aid groups on Facebook as the number of COVID cases increased, during the second wave of the pandemic there was no such increase in support-related activity despite the very high number of cases.5

Table 1.

Mean number of posts per month and total number of posts per week.

| Month (Mean number of posts per month) | Week | Number of posts per week |

|---|---|---|

| March (5426) | 2 | 290 |

| 3 | 7916 | |

| 4 | 8073 | |

| April (2854) | 1 | 3913 |

| 2 | 2713 | |

| 3 | 2461 | |

| 4 | 2332 | |

| May (1403) | 1 | 1709 |

| 2 | 1331 | |

| 3 | 1230 | |

| 4 | 1344 | |

| June (878) | 1 | 915 |

| 2 | 893 | |

| 3 | 784 | |

| 4 | 920 | |

| July (633) | 1 | 631 |

| 2 | 593 | |

| 3 | 549 | |

| 4 | 760 |

| Month (Mean number of posts per month) | Week | Number of posts per week |

|---|---|---|

| August (451) | 1 | 480 |

| 2 | 433 | |

| 3 | 443 | |

| 4 | 451 | |

| September (413) | 1 | 324 |

| 2 | 386 | |

| 3 | 407 | |

| 4 | 535 | |

| October (498) | 1 | 339 |

| 2 | 387 | |

| 3 | 408 | |

| 4 | 858 | |

| November (602) | 1 | 749 |

| 2 | 572 | |

| 3 | 480 | |

| 4 | 608 | |

| December (−) | 1 | 197 |

To explore whether there were statistically significant differences in the number of social support posts from week to week, we carried out a repeated measures ANOVA. Test results with Huynh-Feldt correction showed that there were significant differences in the mean score of social support-related posts over time, F(1.592, 153.119) = 43.884, p < .001, η 2 = 0.30. Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction showed that there was a significant increase in the total number of posts between the second and third week of March (mean difference 73 posts, p < .001). The rapid decrease in posts between the last week of March and the first week of April was also significant (mean difference 40 posts, p < .001), and so was that between the first and second week of April (mean difference 11 posts, p < .001). There was a significant but nevertheless small increase in posts between the last week of April and the first week of May (mean difference 6 posts, p < .005). Similarly, there was a very small significant increase in the mean number of posts between the last week of June and the first week of July (mean difference 2.8 posts, p < .05). There was also a very small but statistically significant decrease in posts between the last week of July and the first week of August (mean difference 2 posts, p < .05).

Following that period there were no significant differences between each week for the period between the first week of August and the last week of November. The small increase in the number of social support-related posts when the second lockdown was announced between the third and the fourth week of October only marginally reached statistical significance (mean difference 4.4 posts, p = .053). Subsequently, there was a minor but still statistically detectable decrease in the mean number of posts between the last week of November and the first week of December (mean difference 3.9 posts, p = .001) as well as between the first and the second week of December (mean difference 1.5 posts, p < .001).

Our analysis of the data suggests that the massive increase in social support activity in Facebook mutual aid groups only occurred during the first wave and was not repeated during the second wave of the pandemic in the United Kingdom. When the cases were rising in early March 2020, we witnessed a 2629% increase in social support-related activity between March week 2 and week 3. However, with the cases rising sharply again in the period between September–October 2020, we only witnessed an increase of 110% between October week 3 and week 4 with the overall numbers being much lower compared to those witnessed in March 2020.

3.2. Quantitative results (ii): Offers and requests of support during the peak of the first and second waves

We coded and quantified group activity related to offers and requests for social support during the peak of the first (March 15 – April 14) and second wave (October 15 – November 14). The data is summarized in Table 2 below. An inspection of the data shows that the number of offers in Wave 1 was 1.85 times higher than requests. Similarly, offers in Wave 2 were 1.76 times higher compared to requests for support. Moreover, the number of offers in Wave 1 was 12.7 times higher than the number of offers in Wave 2, and the number of requests in Wave 1 was 11.7 times higher compared to Wave 2.

Table 2.

Offers and requests of social support on Facebook mutual aid groups during waves 1 and 2.

| Offers | Requests | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | ||

| March Week 3 | 1622 | 632 |

| March Week 4 | 1484 | 862 |

| April Week 1 | 816 | 566 |

| April Week 2 | 507 | 331 |

| Total = 4429 | Total = 2391 | |

| Wave 2 | ||

| October Week 3 | 89 | 53 |

| October Week 4 | 105 | 63 |

| November Week 1 | 109 | 58 |

| November Week 2 | 56 | 29 |

| Total = 359 | Total = 203 | |

Overall, from the data, we can distinguish a pattern whereby offers for support in Facebook mutual aid groups were much higher compared to requests for support across both waves, as well as a general decline in both offers and requests between the two waves. The pattern of overall decline seems to cover all support-related activity but offers seem to have decreased significantly between Waves 1 and 2. Interestingly, the ratios between requests and offers of support largely remain very similar across the two waves. The reasons behind the decline will be considered in the discussion.

3.3. Qualitative results: Types of social support requested and offered through mutual aid Facebook groups

First, we discuss the types of social support that people offered through the online COVID-19 support groups. Our analysis will continue by discussing what types of social support were requested through the COVID-19 support groups. To substantiate our points, we will provide examples through quotes from the posts themselves. Usernames, group names, or references to specific locations have been removed. A summary of the different types of social support offered or requested can be found in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Types of social support offered or requested through the Facebook COVID-19 support groups.

| Offered Social Support | |

|---|---|

| Offered practical support | Food shopping & collecting prescriptions |

| Food donations & support for food banks | |

| Support with pets | |

| Provision of transport | |

| Offers of items (sanitary items, household items, items for babies) | |

| Making masks and visors | |

| Support with translations and languages | |

| Offered informational support | Provision of information (on deliveries and availability of products) |

| Signposting to groups and support services | |

| Creating leaflets | |

| Sharing mental health resources | |

| Offered emotional support | Phone calls |

| Leisure activities | |

| Mental health activities & sessions |

|

|

Requested Social Support | |

| Requested practical support | Food shopping & collecting prescriptions & medical items |

| Support with food parcels & food banks | |

| Support with transport | |

| Requests for volunteering | |

| Donations to charities | |

| Household items | |

| Language support | |

| Requested informational support | Requests for advice (on deliveries, collecting prescriptions, signposting to professionals or volunteers, accommodation) |

| Advice on medical issues and governmental guidance | |

| Linking to other groups | |

| Requested emotional support | Phone calls |

3.3.1. Types of social support offered

3.3.1.1. Offers of practical support

The demands posed by the pandemic (e.g., the need to self-isolate, potential temporary scarcity of products) rendered online support groups as invaluable platforms for practical support to be offered to those in need. Volunteers supported others with food shopping and collecting prescriptions, donated food to others and to food banks, helped with pet care (e.g., dog walking), provided support with transporting people and goods, offered various types of items, assisted by making masks and visors, supported with translations and other language-related issues, and organized leisure activities to facilitate connectedness during lockdown. Primarily, the mutual aid groups assisted with activities such as food shopping or collecting prescriptions for those in need:

Hi, I’m in [location removed] and working from home with immediate effect. If anyone knows any elderly people who need help, please let me know and I’ll gladly do their groceries for them or go to the pharmacy if they need it. Send me a message and we can exchange details!

The support groups also operated as platforms for people to donate food to individuals, or food or financial assistance to food banks:

We are in self-isolation due to pre-existing conditions. We have items we would like to donate to the food bank. Is there anyone collecting items at this time? Thx in advance.

Group members also offered various types of items that might have been of use to people that were self-isolating. Among others, these items included items for babies (e.g., baby milk or nappies), household items such as TVs or children's toys, or female sanitary items:

Hope this isn’t too much of a random question for this group. Does anyone know of someone who could make use of a TV. Anyone having to isolate in different rooms in the same house for example. I have an oldish tv that I don’t need but still works great. LG, 32inch, ×1 HDMI port. Can deliver locally if needed.

Considering the shortage of medical grade masks as well as an absence of cloth masks for non-medical use at the early stages of the pandemic, some people offered to either donate or to design visors or facemasks:

Hi, I know face masks aren't recommended yet in the UK but they have just been recommended by the CDC in America and plenty of people are choosing to wear them in the UK any way. Would there be any interest in home made cloth face masks to give out to vulnerable groups or anyone else that wants them? I am happy to make some, and there is also a simple pattern here

Some group members offered support with transport by making available their vehicles to carry out a range of tasks such carrying people or items:

Hi there, I live in [location removed] have a car, and now suddenly find myself with a lot more free time than before …. would be happy to help in any way I can.

Owning a pet and having to attend to its needs during the pandemic could be very hard for those that were vulnerable or that had to self-isolate. Thus, many people offered to take care of others’ pets by providing activities such as dog-walking or by providing them with pet food:

I am an experienced dog owner, with plenty of time on my hands. I am very happy to walk elderly/vulnerable and ill people's dogs in the [removed] area.

Considering that the pandemic affected a very large and diverse proportion of the population, one of the needs that appeared concerned issues of communication. Thus, people with knowledge of different languages or with experience in translation offered their services through the mutual aid groups:

I am translating NHS information into Slovak, Czech etc. We [name removed] and I getting them printed as big posters.

3.3.1.2. Offers of informational support

The emergence of the pandemic not only mobilized people to offer practical assistance (e.g., grocery shopping, collecting prescriptions) but also to support others by providing them with important information in relation to various aspects of everyday life. Such support included information on delivery services and the availability of products, signposting to other support groups, or creating leaflets with information on where to seek support.

Considering that people's needs during the early stages of the pandemic increased, especially for those self-isolating or vulnerable, online group members provided crucial information on delivery services provided by various companies. Additionally, some group members created publicly available databases of various companies that were providing delivery services:

[Company name] are doing a delivery service for the over 70’s and vulnerable, you just phone up and press option 5. My parents did this week and had an order delivered the following afternoon, you can also add items that aren’t on the list. Great service.

Group members also provided information on where people could find specific products as well as what items were hard to come by:

Been to [company name]and [company name] in [location] today, late lunchtime and both were a lot better. Lots of fruit and veg and other shelves much better ([company name] better than [company name]) but still no toilet roll, pasta etc. [company name]I didn't even have to queue) So if you do need some essential, other than those things, then might be worth giving them a visit.

As of 14:30 today big [company name]in [location] is well stocked.

Some group members used the groups as platforms through which to signpost other group members to the existence of local support groups:

If you are self-isolating for a reason or other and live in [location] or [location] gardens we have created a neighbours support whatsapp group to help you! Please email [address removed] to be included in the group. Best wishes to all

Some users provided information associated with support provided by official resources (e.g., government, city councils):

If you're in need of help, there are now several services available:

-

-

[Location removed] Council have a dedicated helpline for vulnerable residents which you can call on [removed]

-

-

[Location removed] County Council also have a 24 h helpline, and an online form where you can register yourself or someone else as a person in need. Tel: [removed] Web: [removed]

-

-

[Location removed] Coronavirus Assistance are a volunteer run group who can put you in touch with volunteer supporters in your area [website removed]

-

-

There is a list of services such as shopping delivery/pickup, telephone counselling, food parcel delivery etc here [Facebook link removed]

If you'd like to join the [Location removed]Mutual Aid WhatsApp group, please click here: [website removed]

Other group members contributed by sharing resources associated with mental health related information to support children and adults alike:

Hi everyone. I am a clinical psychologist working (full-time) for the NHS so I don’t think that I could do any voluntary work on top of what I do at present, but I would be more than happy to share free resources on here such as on anxiety management for adults and children, ideas on how to connect with others etc. Also if you or anyone else you know is struggling to process what is going on at the mo, just drop me a private msg and I will tailor the information to the affected individual. Please, stay at home but connected.

Finally, considering that a large proportion of the population affected might not have access to or knowledge of how to use technology and access support provided online, some members of the support groups offered to create and distribute leaflets with information on where and how to access support:

Hey, I've delivered 50 leaflets mainly to bungalows and houses along [location removed] and a little bit of [location removed] Road where the roads meet - if people have time to do other parts of [location removed] that would be wonderful so people know where to go for help if they need it! Leaflet is in my earlier post.

3.3.1.3. Offers of emotional support

The emergence of the pandemic created a need for emotional support for those experiencing distress. Thus, the groups became platforms for emotional support to be offered. Offered support took the form of phone calls or organizing mental health activities and sessions. The situation was particularly hard for those that did not have access to technology and for example were not able to have online video calls [50]. Considering those needs, group members offered to have phone calls with people in need:

If you, or anyone you know would benefit from a daily phone call and a friendly ear, inbox us < 3

The lockdown was a novel experience for the vast majority for those affected, and physical distancing rules or the need to self-isolate meant that new ways of socialization had to be established. The online groups operated as a platform for people to organize leisure activities such as reading or music activities, fitness classes, or child play activities, and support both adults and children with the lockdown:

Hello all, my housemates and I have set up a website called ‘Lockdown Library’ where all sorts of people will be reading bits from great books, speeches, essays etc. We’re hoping to bring people together to listen to and discuss some great literature.

All donations will be going to [charity name removed] - a charity helping lonely and isolated elderly people.

Finally, some group members designed and ran activities and sessions related to mental health such as laughter clubs, mindfulness sessions, workshops, and emotional support sessions:

Hi, I'm offering free daily mindfulness sessions everyday at 7pm via FB live.

I've created a Facebook page and daily events and everyone is welcome to join.

I'll be present and happy to offer this space to breath in, connect and find a moment of peace in these times of uncertainty.

Overall, the online support groups operated as platforms for various types of social support to be mobilized. People provided support associated with practical (e.g., food shopping, collecting prescriptions), information (e.g., information on deliveries and products, signposting to support services), and emotional (e.g., phone calls, mental health support) needs. Considering that available social support should ideally correspond to the existing needs, we will now discuss the types of social support that were requested through the online support groups.

3.3.2. Types of social support requested

3.3.2.1. Requests for practical support

Users used the groups to request assistance with shopping for food and other items or with collecting prescriptions or other medical items (sterilized wipes, thermometers, painkillers) for themselves or others:

Good morning, my mum lives in [location] and has a lung condition so is high risk. I would like to set up some help with prescriptions and shopping if anyone can help? I did contact the council but have not had a reply. Thanks so much

The need to self-isolate meant that many poorer people relied on food parcels. Thus, some users used the groups to request support in relation to food parcels or foodbanks. More specifically, the support requested took the forms of either food donation or delivery of food parcels to those self-isolating:

Hello I am self isolating due to health issues and I have a food parcel waiting for me near [location] food bank. I am in [location removed] and cannot get there. Is anyone a round there that could help. Much appreciated.

In some occasions, people requested support with transport. For example, some users needed support to leave their accommodation and transport goods to a different location. In other cases, vulnerable residents did not want to use taxis or buses as means of transport and requested lifts through private cars:

Hi! I was wondering if anyone could help me out. I am meant to be moving and need to vacate my flat. This was due to happen on Tuesday and we had all plans in place but as I have a chronic health condition I have been advised by my Dr I need to self-isolate before that. I am desperately trying to sort out my move but have been let down with transportation and a van that my boyfriend was trying to hire. Does anyone have a van or car and could give a lift from [location] to [location]tonight with a few bags of stuff in your car? Any help would be much appreciated

The need for volunteers at the early stages of the pandemic was urgent. Thus, requests not only came from individuals seeking support for themselves, but also from organizers or representatives of organizations (e.g., charities) requesting volunteers to support them with various tasks:

[name removed] Mutual Aid are still looking for volunteers for their street teams to help with deliveries for those self-isolating and vulnerable.. If you live within this ward particularly in the pink and orange, fill out the volunteer form and email: [removed]

Apart from volunteers, organizations were also looking for donations of material resources in order to carry out necessary tasks. Thus, the groups were helpful in notifying other members about donations related to important items such as food, money for equipment, or other cooking materials (e.g., paper boxes or bags):

[charity name removed] are providing grab bag lunches for the homeless. They need food bags with handles (apparently [company name removed] sell them in packs of 35 if you're headed that way) as well as things like sandwich bags/wrappers. Food-wise they need sandwich fillers - ham, cheese, eggs etc and snack items like crisps, biscuits and small cartons of juice, bottled water and drinks, cans. They are currently providing lunches for around 18 people a day. Donations to: [removed]

The need to self-isolate meant that in some occasions people were not able to buy or access various household items. The groups then became a platform for various items such as mattresses or cooking utensils among others to be requested:

Anyone got a spare single mattress going spare? I’m supporting a homeless family who have just moved into town. They have two kids sleeping on camp beds at the moment and I am trying to sort them out. I have a van and can collect this morning. I have one and now need another.

Finally, another type of practical support that was requested was related to support with languages and translations. This was particularly important when considering that the pandemic affected very diverse populations at a time when uninterrupted communication was most crucial:

Hey all, anyone on here speak Arabic? Got a request from [organization] to help one of their members based in [location], WhatsApp me.

3.3.2.2. Requests for informational support

Group members requested information in relation to a wide range of issues including deliveries, product collections and medical items, medical advice, accommodation, or signposting to other people that can offer support or to various professionals (e.g., dentists).

One of the most requested types of support was for information in relation to deliveries or collections of food or where to buy medical items or prescriptions:

Hello I'm looking for some help please. My partners father is vulnerable and has not received any letters from the NHS as expected. Both parents are over 70. How does one go about getting registered with a supermarket for priority deliveries etc & getting prescriptions collected? Many thanks x

Finding a place to stay during the pandemic could be particularly tricky due to lockdown or self-isolation measures, so some group members asked for support in relation to finding accommodation.

Hi! Not sure if this group can help but myself, my partner and our little chihuahua are looking for temporary accommodation for 2/3 months starting end of April if anyone knows of any vacant properties or rooms etc to rent? Unable to house share as I am still working and wouldnt want to put others at risk. This is due to us having planned on moving house, our buyer cant extend his mortgage offer and the people we are buying from arent ready! Thanks!

Some group members were looking for information regarding specific professionals (e.g., contact details of doctors) or for volunteers that could support specific individuals:

Looking for support for an elderly lady who is self isolating and symptomatic in [location]. Who might be best placed to help?

Are there any dentists still open to patients.

Considering that the early stages of the pandemic were characterized by uncertainty and a lack of information, many group members requested advice in relation to medical issues and governmental guidance through the groups:

Hi all just your thoughts please, I have family returning from [location] tomorrow, they are travelling via [location], when they get back do they need to self isolate, can’t see on any government websites about this, they are both showing any symptoms, thanks guys

Hi. Can anyone recommend a good place to buy masks, and would like to know which masks are recommended against Covid19. Thank you

Apart from requesting advice, group members also used the groups as means of finding information about and linking to other groups. This included requests for contact details of specific groups as, or to identify whereas any third groups are responsible for particular areas:

Has anyone got the best link for the [location] group that covers [location]? We are [group name removed], but people are coming to us who live in the [location] area on the other side of the [location]. Is there an active group we can pass them on to?

Overall, people used the groups to seek a wide range of information associated with various types of advice (e.g., in relation to deliveries, medical advice, accommodation) or links to other groups. We will now discuss the emotional support that was mobilized through the groups.

3.3.2.3. Requests for emotional support

The only type of emotional support that was requested in our sample was not requested by people themselves in need but was associated with phone calls towards third users. Group members or representatives of organizations were often seeking individuals who would be able to chat with specific people or with those that did not have access to or were not familiar with using computers and technology in general [50]:

If anyone feels lonely and has free time would you be OK to have chats during the day? One of the [charity name] is asking for someone to talk too and I am sure they are not the only one

Are there any telephone-based support groups for those who are not over 70 and not computer literate?

Overall, the groups operated as platforms for users to request support either for themselves or on behalf of organizations (e.g., requesting volunteers). For instance, people requested help with practical issues (e.g., support with shopping food and medical items, transport, donations), regarding information (e.g., requesting advice in relation to accommodation, prescriptions) as well as emotional support.

4. Discussion

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 4000 mutual aid groups were set up in the United Kingdom to provide social support to those in need. Considering the restrictions posed by the pandemic (e.g., mandates for “lockdowns” and social distancing), social media platforms such as Facebook and Whatsapp, which also allow for groups and group activities to be set up, played a key role in allowing people to request or provide social support. The support mobilized through disaster communities and mutual aid groups has been shown to be beneficial for the wellbeing of people who both receive and provide it [22,34,[37], [38], [39]]. Crucially however, disaster communities and the availability of social support often decline in the period that follows the main impact of extreme events at a time when needs remain high [3,11]. Considering that pandemics are characterized by multiple waves of infections and are not one-off incidents like other extreme events such as earthquakes, as well as that social media played a central role in mobilizing social support during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, our aims in this paper were threefold: We focused on online mutual aid groups established on Facebook to examine the trajectory of social support-related activity over the first and second waves of the pandemic in the United Kingdom, the patterns of offers and requests for support at the peak of the first and second wave, and the types of social support that were offered or requested through the groups.

Data from 105 Facebook groups show a trajectory of steep increases in social support activity at the onset of the first wave in March 2020, which is in line with evidence showing that social support is abundant at the early stages of extreme events [2,3,12,24]. The mobilization of social support can be triggered by the collective experience of common fate that gives rise to a shared social identity, causing change to social relations [18]. However, the eventual ending of the liminal phase, or communitas, that the early period of a disaster constitutes [51], can lead to the return to a pre-disaster mode of “everyday life” often structured around the pre-existing status quo [52]. Stallings and Quarantelli argue that emergent groups endure for short periods after a disaster that can range from between a few hours to a few days [41]. In their research, Kaniasty and Norris observed reductions in flooded residents' expectations of support between 3 and 6 days after the disaster [16]. In our data, support activity in Facebook mutual aid groups started declining around 3 weeks after its rapid emergence, supporting previous findings [3,11,18,40]. However, the groups continued to operate throughout the first and second waves, albeit at a reduced level. What our data cannot confirm though, as we also explain in the ‘Limitations’ section, is whether the decline is a function of social support actually stopping or whether users moved to different platforms (e.g., Whatsapp) or to interpersonal modes of support.

Despite cases during the second wave (and by extension the needs for support) being very high and similar to the first wave, our data do not show a re-mobilization of social support similar to the March–April 2020 period. This could be due to a range of reasons. For instance, people that provided others with social support during the first wave were not able to do so anymore. Alternatively, after the first pandemic wave or at the onset of the second wave people might not have experienced a sense of unity that became the basis for social support. This might have happened for a range of reasons. For example, following the first wave, and during the summer of 2020, some people might have returned to experiencing some sense of normality. Others might have come to feel familiar with the pandemic and with restrictions such as lockdowns, resulting in not re-experiencing the novelty and the sense of camaraderie and community that characterized the first pandemic wave.

All those reasons perhaps caused the public mobilization of support to be lower compared to the first wave. However, it is possible that those in need had already established connections and had identified sources of support, rendering the Facebook mutual aid groups largely unnecessary. According to Kaniasty and Norris [11,42], social support is primarily provided by primary groups such as family and friends and then extends to wider groups and organizations. Thus, the current Facebook dataset might be revealing a change in the mode of the provision and requests of social support from large scale online groups to more interpersonal sources not captured in the data.

Apart from the general trajectory of social support activity in Facebook mutual aid groups over time, a novel aspect of our study was the examination of whether and how offers and requests for support changed between the first and second waves. This analysis was important in that it would allow us to investigate with greater precision where potential differences in mutual aid group activity between the two waves might lie. For example, do offers of support decline while requests of support through the groups remain high, posing problems for those in need? Or do people continue offering support while requests for it decline? Based on the general decline in social support activity that we observed through the first analysis, a reduction in both offers and requests was expected. However, what stands out from our second analysis is that despite a steep decline in both offers and requests for support between waves 1 and 2, the ratios between offers and requests remain largely the same. These findings are useful as they indicate that the groups did not cease their operation during the second wave, but rather they continued to function, albeit to a smaller degree. Requests for support were also made through the groups but offers remained higher, similar to the first wave. These findings also show the patterns of support that might be observed in extreme events that might be repeated over time – that is, both offers and requests for support are higher at the early stages of an extreme event and both decline in subsequent incidents, but offers of support appear to be steadily higher compared to requests.

Our study provides insights in relation to the types of social support were mobilized through the Facebook mutual aid groups. The groups were crucial in people offering or requesting practical, informational, and emotional support. For instance, group members were able to provide practical support such as resources and actions (e.g., food shopping), transport, help with pets, or even support with translations, as well as informational support such as signposting, mental health resources or leaflets, and finally emotional support in the form of phone calls, leisure activities, or mental health activities. Crucially, such offers of support largely matched what was requested through the groups. For instance, people requested mostly practical support such as food shopping, donations, household items or language support, and some of this support was requested after people could not have their needs met through official sources (e.g., support from local authority). Our analysis verifies the analytical usefulness of the typology provided by Kaniasty and Norris regarding the patterns of support observed in previous disasters [11,22].

Some users also used the groups on behalf of third organizations to act for support. The groups were also very useful in people requesting informational support. Importantly, people also turned to these groups to seek information related to medical issues (e.g., the appropriateness of different masks) or in relation to the governmental guidance (e.g., in relation to self-isolation). However, despite the groups being crucial in mobilizing support, there are dangers when it comes to the dissemination of some types of information, and particularly related to information related to medical issues or official guidance. That is because group members might not be familiar with the latest or most accurate information on governmental guidance, or might simply not possess specialized medical knowledge, thus potentially putting others in danger. Thus, it is imperative that groups set up rules regarding the type of information that can be shared with others and signpost their users to official resources or contacts (e.g., governmental websites, local councils).

4.1. Limitations and future research

Our study has a range of limitations. Our quantitative sample constitutes only around 4% of the mutual groups included in the list of such groups operating within the United Kingdom. The use of a larger number of groups would potentially give us a more accurate estimation of the trajectories of social support during the various pandemic waves.

Another issue regarding our quantitative analysis concerns the rapidly changing nature of the pandemic and people's means of coping with it in terms of seeking support. Our study cannot explain the reasons behind the decline of social support following the initial upsurge in the first period of the covid pandemic for three reasons. First, such a quantitative sample can only offer insights into the trajectory of activity rather than on the motivations and perceptions of those who offer or request it (or do not). Second, some group members have dropped out, but such data are impossible to be captured in the dataset. Third, Facebook groups were not the only means through which social support was offered or requested, and groups were also formed on different platforms. However, our sample only concerns Facebook groups. Other apps and platforms could operate as platforms for people to request or receive support. However, in some cases this could only happen on an individual basis. For example, Instagram does not include a group chat function and users can only interact with others individually. Websites in the form of public forums could also help people organize and offer or request support. One such example is Reddit (https://www.reddit.com/), which includes both a ‘mutual aid’ section (https://www.reddit.com/r/MutualAid/) as well as a ‘COVID-19 support’ section (https://www.reddit.com/r/COVID19_support/). However, upon closer inspection, these sections are not structured around local areas like the Facebook mutual aid groups, and are mostly platforms where people can express their worries and concerns rather than to request specific support. One other platform which allowed mutual aid groups to operate was Whatsapp, as it incorporates a group chat function in its design. However, the main reason why we could not include Whatsapp groups in our analysis was because such groups are private and thus impossible to identify and join, as well as because new users are only added by existing users through a phone number. Considering the novelty of the pandemic and therefore the lack of pre-existing pandemic-related online groups, it is very likely that people first searched for publicly available, local Facebook groups through which they could request and offer support. Subsequently, some might have been redirected to other platforms such as WhatsApp which only requires a phone number and offers a more direct request/response system and thus increased immediacy. Others could have switched to peer-to-peer support without the need for groups acting as intermediaries (e.g., the website ‘Next Door’ [https://www.nextdoor.com]).

Based on the points raised above, while the heavy use of Facebook during the first wave might reflect the novelty of the pandemic and the lack of other more personalized means of connecting (e.g., WhatsApp which requires a phone number), the decline of support activity on Facebook groups in Wave 2 might also reflect not an actual decline but a change in platforms or people having created supportive relationships during the first wave that they could contact without the need for social media to operate as mediators. Future research needs to use larger samples from a range of platforms (e.g., WhatsApp, Twitter) and map patterns of social support over time more accurately.

Another limitation of the study concerns potential sampling biases. Coders selected Facebook groups arbitrarily from the list, only making sure that they included groups from various geographical locations and with varying numbers of members. However, this was not a randomized approach and thus the sample used could affect the findings. Additionally, coders could only obtain data only after being accepted in each group. Thus, we cannot be sure that there are no different patterns in groups that would not accept members of the team. However, results from the 105 groups reported indicate that groups carried out similar activities and operated in similar ways, and thus the chance of our findings being affected either by selection issues or due to the administrators’ decisions to accept the coders or not remains minimal.

Finally, our qualitative analysis focuses on 10 Facebook groups. The fact that the results are consistent across groups and also in line with previous literature [42] is reassuring, but future research could use automatic extraction methods and explore patterns of support in larger samples. Also, future research should quantify the various types of social support-related activity in online groups (e.g., do users offer or request more practical, informational, or emotional support?) as such findings will help to better understand how users engage with these groups and thus help to harness their potential for disaster risk reduction.

5. Conclusion

Our study highlights the important role of social media in pandemics. Social media operate as platforms for people to seek and offer social support, and particularly at the early stages of pandemics when more stable support structures (e.g., personal networks) might not yet exist while novel needs keep arising. Considering that the availability of social support and the presence of social networks are core aspects of community resilience [53], policy makers and practitioners should consider the importance of bottom-up community organizing for effective disaster risk reduction in order to effectively harness the support that mutual aid groups can mobilize. More specifically:

-

•

Local authorities should be familiar with the (online) mutual aid groups that might operate in their areas, and attempt to establish good relationships with the organizers/coordinators.

-

•

Local authorities should provide the organizers of the online mutual aid groups with credible information regarding medical issues or official guidelines. This measure will help to tackle the spread of misinformation or outdated guidance.

-

•

Considering the difficulties in matching support demand to supply as well as in organizing offers of support effectively, the availability of forums, especially at the early stages of extreme events, where users can post their offers and requests can be very useful.

-

•

Recognition of mutual aid groups by authorities and other organizations can potentially imbue the former with legitimacy and establish them as credible sources of support, preventing the deterioration of the availability of social support.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Last accessed on 11/1/2022.

Last accessed on 11/1/2022.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/18P898HWbdR5ouW61sAxW_iBl3yiZlgJu0nSmepn6NwM/edit#gid=1451634215 (last accessed in 30/5/2021).

In July 2021 however we could only access 83 from the 105 groups that we examined originally. We could no longer access 11 of them and another 11 had closed their Facebook pages.

During the first wave (and by extension to the graph presented in Fig. 2), infection levels were undercounted. On March 12, 2020, the UK government moved away from community tests and contact tracing (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52545662). However, testing capacity started increasing in late April 2020 (https://www.hsj.co.uk/quality-and-performance/government-counts-mailouts-to-hit-100000-testing-target/7027544.article). Thus the difference in the number of cases between the first and second waves is in large part a function of differences in the number of tests administered. Positivity rate figures (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/uk-covid-positivity?time=2020-03-05..latest&country=∼England) and death rate figures (https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/deaths) by contrast suggest that the first wave was at least as big as the wave in Autumn 2020.

References

- 1.Fritz C. Historical and Comparative Disaster Series #10 (Written in 1961) University of Delaware: Disaster Research Center; 1996. Disasters and mental health: therapeutic principles drawn from disaster studies. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solnit R. Penguin Books; 2009. A Paradise Built in Hell: the Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quarantelli E.L. University of Delaware Disaster Research Center; 1999. Disaster Related Social Behavior: Summary of 50 Years of Research Findings.http://dspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/289 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus: Hundreds Join Brighton Facebook Support Group [Internet] BBC News; 2020 Mar 14. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-51887733 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Help The Hungry: More than 4,000 ‘mutual aid’ groups set up across UK to help struggling neighbours get food, The Independent, 2020, Apr 8. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-help-the-hungry-campaign-food-covid-19-mutual-aid-uk-a9453216.html. Accessed 14 May 2022.

- 6.Tiratelli L, Kaye S. Communities vs. Coronavirus - the rise of mutual aid. New local government network. 1-38. Available from: https://www.newlocal.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Communities-Vs-Corona-Virus-The-Rise-of-Mutual-Aid.pdf.

- 7.Pleyers G. The Pandemic is a battlefield. Social movements in the COVID-19 lockdown. J. Civ. Soc. 2020;16(4):295–312. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2020.1794398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Community aid groups set up across UK amid coronavirus crisis. The Guardian. 2020 http://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/16/community-aid-groups-set-up-across-uk-amid-coronavirus-crisis [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.UK volunteering soars during coronavirus crisis. The Guardian. 2020 http://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/may/26/uk-volunteering-coronavirus-crisis-community-lockdown [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ntontis E., Rocha C. Together Apart: the Psychology of COVID-19. Sage; London: 2020. Solidarity; pp. 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaniasty K., Norris F. In: Response to Disaster: Psychosocial, Community, and Ecological Approaches [Internet] Gist R., Lubin B., editors. Bruner/Mazel; London: 1999. The experience of disaster: individuals and communities sharing trauma; pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritz C., Williams H. The human being in disasters: a research perspective. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 1957;309(1):42–51. doi: 10.1177/000271625730900107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montano S. Disaster fatigue is real—and the coronavirus could make it worse [Internet]. Gizmodo. [cited 2021 Jul 28]. Available from: https://gizmodo.com/disaster-fatigue-is-real-and-the-coronavirus-could-make-1844079719. Accessed 14 May 2022.

- 14.Borkowska M., Laurence J. Coming together or coming apart? Changes in social cohesion during the Covid-19 pandemic in England. Eur. Soc. 2021;23:S618–S636. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1833067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams D. What has happened to trust and cohesion since Tier 4 restrictions and the third national lockdown (December 2020 – March 2021)? Further evidence from national surveys (2021). The British Academy. Available at https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/covid-decade-what-happened-trust-cohesion-tier-4-restrictions-third-national-lockdown/.

- 16.Kaniasty K., Norris F. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993;64(3):395–408. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuter C., Kaufhold M.-A. Fifteen years of social media in emergencies: a retrospective review and future directions for crisis Informatics. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2018;26(1):41–57. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drury J., Carter H., Cocking C., Ntontis E., Guven S.T., Amlot R. Facilitating collective resilience in the public in emergencies: twelve recommendations based on the social identity approach. Front. Public Health. 2019;7:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aldrich D.P., Meyer M.A. Social capital and community resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014:1–16. doi: 10.1177/0002764214550299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ntontis E., Drury J., Amlôt R., Rubin G.J., Williams R. What lies beyond social capital? The role of social psychology in building community resilience to climate change. Traumatology. 2019:253–265. doi: 10.1037/trm0000221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobfall S.E. Hemisphere; Washington, DC: 1988. The Ecology of Stress. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norris F.H., Kaniasty K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: a test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996;71(3):498–511. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drury J., Carter H., Ntontis E., Guven S.T. Public behaviour in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding the role of group processes. BJPsych open. 2021;7(1):e11. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn S.K. Epidemics: Hate and Compassion from the Plague of Athens to AIDS. 2018. Epidemics: hate and compassion from the plague of athens to AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prime Minister's statement on coronavirus (COVID-19) GOV.UK. 23 March 2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020 [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain - Off. Nat. Stat. [Internet]. 1-17. [cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/30april2021#main-indicators.

- 27.Smith L.E., Potts H.W.W., Amlôt R., Fear N.T., Michie S., Rubin G.J. Adherence to the test, trace, and isolate system in the UK: results from 37 nationally representative surveys. BMJ. 2021;372:n608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SPI-B . GOV.UK; 16 September 2020. Impact of Financial and Other Targeted Support on Rates of Self-Isolation or Quarantine.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spi-b-impact-of-financial-and-other-targeted-support-on-rates-of-self-isolation-or-quarantine-16-september-2020 [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel J., Fernandes G., Sridhar D. How can we improve self-isolation and quarantine for covid-19? BMJ. 2021;372:n625. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reicher S., Drury J., Michie S. The BMJ; 2021. Contrasting Figures on Adherence to Self-Isolation Show that Support Is Even More Important than Ever.https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/04/05/why-contrasting-figures-on-adherence-to-self-isolation-show-that-support-to-self-isolate-is-even-more-important-than-we-previously-realised/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerkhoff A.D., Sachdev D., Mizany S., Rojas S., Gandhi M., Peng J., et al. Evaluation of a novel community-based COVID-19 ‘Test-to-Care’ model for low-income populations. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A Million Volunteer to Help NHS and Others during Covid-19 Outbreak [Internet] The Guardian; 2020. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/13/a-million-volunteer-to-help-nhs-and-others-during-covid-19-lockdown Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Horror Films Got it Wrong. This Virus Has Turned Us into Caring Neighbours [Internet] The Guardian; 2020. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/31/virus-neighbours-covid-19 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seebohm P., Chaudhary S., Boyce M., Elkan R., Avis M., Munn-Giddings C. The contribution of self-help/mutual aid groups to mental well-being. Health Soc. Care Community. 2013;21(4):391–401. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao G., Fernandes-Jesus M., Ntontis E., Drury J. What have we learned about COVID-19 volunteering in the UK? A rapid review of the literature. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21(1):1470. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11390-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neighbors mobilize to help each other during coronavirus pandemic. Gothamist. 2020 https://gothamist.com/news/neighbors-mobilize-help-each-other-during-coronavirus-pandemic [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaniasty K. Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: the role of postdisaster social support. Psychol. Trauma: Theor., Res., Pract. Pol. 2012;4(1):22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao G., Drury J., Fernandes-Jesus M., Ntontis E. How participation in Covid-19 mutual aid groups affects subjective well-being and how political identity moderates these effects. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy. 2021;21(1):1082–1112. doi: 10.1111/asap.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowe M, Wakefield JRH, Kellezi B, Stevenson C, McNamara N, Jones BA, et al. The mental health benefits of community helping during crisis: coordinated helping, community identification and sense of unity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022;32(3):521–535. doi: 10.1002/casp.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ntontis E., Drury J., Amlôt R., Rubin G.J., Williams R. Endurance or decline of emergent groups following a flood disaster: implications for community resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020;45:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stallings R.A., Quarantelli E. Emergent citizen groups and emergency management. Publ. Adm. Rev. 1985;45:93–100. doi: 10.2307/3135003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]