Abstract

Background.

The ability to rate delirium severity is key to providing optimal care for persons with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD). Such ratings would allow clinicians to assess response to treatment, recovery time and prognosis, nursing burden and staffing needs, and to provide nuanced, appropriate patient-centered care. Given the lack of existing tools, we defined content domains for a new delirium severity instrument for use in individuals with mild to moderate ADRD, the DEL-S-AD.

Methods.

We built upon our previous study in which we created a content domain framework to inform development of a general delirium severity instrument, the DEL-S. We engaged a new expert panel to discuss issues of measurement in delirium and dementia and to determine which content domains from the prior framework were useful in characterizing delirium severity in ADRD. We also asked panelists to identify new domains. Our panel included eight interdisciplinary members with expertise in delirium and dementia. Panelists participated in two rounds of review followed by two surveys over two months.

Results.

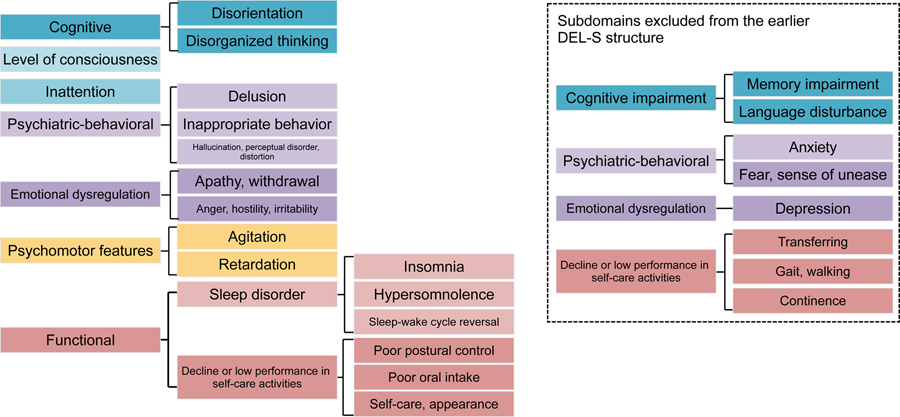

Panelists endorsed the same content domains as for general delirium severity, including Cognitive, Level of Consciousness, Inattention, Psychiatric-Behavioral, Emotional Dysregulation, Psychomotor Features, and Functional; however, they excluded six of the original subdomains which they considered unhelpful in the context of ADRD: cognitive impairment; anxiety; fear/sense of unease; depression; gait/walking; and incontinence. Debated measurement challenges included assessment at one point in time versus over time, accounting for differences in clinical settings, and accurate assessment of symptoms related to delirium versus dementia.

Conclusions.

By capturing a range of characteristics of delirium severity potentially present in patients with ADRD, a population that may already have attention, functional, and emotional changes at baseline, the DEL-S-AD provides a novel rating tool that will be useful for clinical and research purposes to improve patient care.

Keywords: delirium, dementia, ADRD, expert panel, instrument

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is an acute decline in cognitive function and attention,1 while dementia is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that causes decline in cognitive function, reasoning, and memory,2 represented by Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias (ADRD). In 14 cohort studies examining occurrence of delirium in adults age 65 and older, the prevalence of delirium superimposed on ADRD ranged from 22–89%.3 Delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) is associated with poor long-term outcomes, including accelerated cognitive decline, re-hospitalization, institutionalization, and death.4–6 Quantification of delirium severity has become increasingly important to examine changes over time, monitor treatment response, and inform prognosis.1,7 However, delirium severity in older persons with ADRD has not been fully examined, in part due to the lack of validated instruments that can be used in clinical care and translational research to examine this vulnerable population.

We describe a rigorous expert panel process used to develop content domains for a delirium severity instrument, the DEL-S-AD, that is intended to be used in individuals with mild to moderate ADRD. The DEL-S-AD instrument is based on the DEL-S8 and on our prior work developing content domains for a general delirium severity instrument.9 The previously identified domains of delirium severity9 were Cognitive (subdomains: disorientation, disorganized thinking, cognitive impairment), Level of consciousness, Inattention, Psychiatric-Behavioral (subdomains: delusions, inappropriate behavior, hallucination/perceptual disorder/distortion), Emotional Dysregulation (subdomains: anxiety/fear/sense of unease, depression/apathy/withdrawal, anger/hostility/irritability), Psychomotor Features (subdomains: psychomotor agitation, psychomotor retardation), and Functional (subdomains: sleep disorder, decline or low performance in self-care activities). The charge of the expert panel was to determine which of these domains and subdomains were useful in characterizing delirium severity in ADRD and to identify any additional domains using an online rating form over two rounds of review. Our goal was to develop the DEL-S-AD as an instrument to objectively rate delirium severity in a population that may already have attention, functional, and emotional changes at baseline, and which will advance the field of DSD.

METHODS

We performed this work as part of the Better Assessment of Illness (BASIL) study,10 a prospective cohort study of hospitalized older adults designed to examine delirium severity and related outcomes. The goal of this sub-project was to develop and test measures of delirium severity, focusing on individuals with mild to moderate ADRD. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Hebrew SeniorLife, the study coordinating center.

Expert panels are used to reach consensus on a topic.11 We defined experts as individuals with clinical and/or research expertise in delirium, dementia, and/or DSD. Our multidisciplinary expert panel included eight national and international experts who participated in a modified Delphi approach.12 Delphi methodology is used when topical data are sparse or rapidly evolving, as with DSD.12 This expert panel process was overseen and coordinated by the BASIL study team/leaders (RNJ, SKI) who provided guidance and instructions and ensured alignment with BASIL study goals. We conducted panel discussions online using a teleconference platform and following recommended practices for online panels.11 The surveys and ratings completed following each meeting were also conducted online.

We engaged our expert panel to define how to best define the construct of delirium severity in ADRD and to identify content domains related to delirium severity symptoms. The guiding questions for our construct definition were: What is the meaning of delirium severity in the context of dementia? What are the important domains of delirium severity in the context of dementia? What are the threats to the validity of assessing the important domains of delirium severity in the context of dementia?

Expert Review of Content Domains

Round 1.

We convened the expert panelists via teleconference in November 2020. Prior to the virtual meeting, the BASIL study team provided panelists with background materials on the BASIL study and conceptual framework as well as articles from a literature review on delirium severity relevant to dementia. The goal of the teleconference was to discuss the construct of delirium severity in ADRD, including defining what should be measured, among whom, and for what purpose, in preparation for rating of the initially proposed content domains.

Following the teleconference, we provided the expert panelists the initially proposed domains online along with a rating form that listed each domain, its subdomains, and their working definitions based on established sources.13–19 Directions were to: 1) indicate if each domain and subdomain should be included, excluded, or if they were uncertain; 2) suggest additional domains or subdomains; 3) comment on domains and subdomains, their definitions, and potential measurement challenges. Consensus decisions were based on mean Likert scale ratings of agreement (1 = strongly agree, 9 = strongly disagree). Mean scores less than or equal to 3 or greater than or equal to 7 were considered consensus, no consensus was defined as a mean rating between 3.5 and 6.5, and other scores were considered near consensus.20

Round 2.

We convened a second teleconference in December 2020. Panelists discussed rating results for the content domains as well as comments, particularly for domains for which there was lack of consensus to include or exclude. Panelists discussed revisions to indicated content domains which were then implemented by the BASIL study team to produce rating forms for Round 2. Following the virtual meeting, the BASIL study team provided the revised content domains to panelists with the new online rating form and processed responses to arrive at final content domains and subdomains.

RESULTS

Eight panelists (see Supplemental Material) participated in both teleconferences. One panelist was unable to complete the Round 2 rating form due to urgent clinical responsibilities related to Covid-19. We present ratings of content domains and subdomains for both rounds in Table 1 and their final definitions in Table 2. In Figure 1, we detail the final domains and subdomains and note changes from the previous structure for the DEL-S.8

Table 1.

Expert Panel Ratings of Delirium Severity in Dementia Content Domains and Subdomains across Rounds of Review

| Round 1 (n=8) |

Round 2 (n=7) |

Final Decision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Subdomain |

I | E | U | I | E | U | I/E/U |

| Level of consciousness |

8 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | Include |

| Inattention |

6 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | Include |

| Cognitive: Disorientation |

1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Include |

| Cognitive: Disorganized thinking |

2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | Include |

| Cognitive: Cognitive impairment |

3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1** | Exclude |

| Psychiatric-Behavioral: Delusions |

5 | 0 | 3 | - | - | - | Include |

| Psychiatric-Behavioral: Inappropriate behavior |

6 | 0 | 2 | - | - | - | Include |

| Psychiatric-Behavioral: Hallucination/perceptual disorder/distortion |

7 | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | Include |

| Emotional Regulation: Anxiety |

4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | Exclude |

| Emotional Regulation: Fear, sense of unease |

4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | Exclude |

| Emotional Regulation: Depression |

4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | Exclude |

| Emotional Regulation: Apathy |

4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Include |

| Emotional Regulation: Withdrawal |

4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | Include |

| Emotional Regulation: Anger, hostility, irritability |

6 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | Include |

| Psychomotor: Agitation |

7 | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | Include |

| Psychomotor: Retardation |

7 | 1 | 0 | - | - | - | Include |

| Functional: Sleep Disorder - Insomnia |

5 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | Include |

| Functional: Sleep Disorder - Hypersomnolence |

3 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | Include |

| Functional: Sleep Disorder – Sleep wake cycle |

5 | 0 | 3 | - | - | - | Include |

| Functional: Performance - Transferring |

3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 0 | Exclude |

| Functional: Performance - Posture |

4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | Include |

| Functional: Performance – Gait, walking |

2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | Exclude |

| Functional: Performance – Poor oral intake |

3 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | Include |

| Functional: Performance - Incontinence |

2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | Exclude |

| Functional: Performance – Self-care, appearance | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | Include |

I = Include count; E = Exclude count; U = Uncertain count

Included= Items for which there was consensus or near consensus that ultimately were retained by reviewers and the study team/leaders

Excluded= Items for which consensus was not achieved and which were not included in the final content domain structure

If 2 or more counts in Uncertain category, required further discussion in Round 2

BASIL Study team decided to Exclude

Table 2.

Final Definitions of Domains and Subdomains for Delirium Severity in ADRD

| Domain/Definition | Subdomain | Subdomain Definition |

|---|---|---|

| LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS Consciousness that is other than alert, typically reduced (such as difficulty keeping awake during examination or difficult to arouse), but also vigilant or hyperalert (overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startles very easily).13 |

-- | -- |

| INATTENTION Reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain and shift attention,14 typically manifested by the patient being easily distractible, having difficulty keeping track of what was being said,13 or needing to repeat questions because attention wanders.16 |

-- | -- |

| COGNITIVE Impairments in cognitive abilities identified by specific cognitive tests.16 |

Disorientation | Lack of orientation to time, place or person.16 Typically manifested by errors on orientation items in cognitive testing, thinking they are somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day.13 |

| Disorganized thinking | Thinking that is disorganized or incoherent13 as manifested by rambling, irrelevant, or incoherent speech or conversation,16 unclear or illogical flow of ideas, unpredictable switching from subject to subject,13 or that demonstrates faulty reasoning.17 | |

| PSYCHIATRIC-BEHAVIORAL Symptoms characteristic of abnormal thoughts and behavior patterns. |

Delusions | Fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. |

| Inappropriate behavior | Behaviors that (i) interfere with patient care and (ii) would not be considered within the norms of appropriate or safe behavior in the hospital setting. These behaviors often reflect confusion or agitation. Examples include: pulling at tubes or dressings; repeatedly attempting unsafe behaviors (such as climbing over side rails); undressing inappropriately; combative behavior; calling out; and yelling loudly or swearing. | |

| Hallucinations, perceptual disorder, distortions | Perception-like experiences that occur with (perceptual disorder, distortion) or without (hallucination) an external stimulus.18 | |

| EMOTIONAL DYSREGULATION Dysregulation in the form of atypical symptom patterns related to anxiety, fear, apathy, depression, and anger. |

Apathy, withdrawal | Hallmark symptoms include anhedonia (decreased ability to experience pleasure from positive stimuli or a degradation in the recollection of pleasure previously experienced18 and dysphoria (general dissatisfaction). |

| Anger, hostility, irritability | Angry mood (e.g. irritability, reactivity), and aggression (verbal and physical). Negative social cognitions (e.g. interpersonal sensitivity, envy, disagreeableness), verbal aggression, and efforts to control anger. Anger is distinguished by attitudes of hostility and cynicism and is often associated with experiences of frustration impeding goal-directed behavior.19 | |

| PSYCHOMOTOR FEATURES Unusually increased or decreased level of motor activity.13 |

Psychomotor agitation | An unusually increased level of motor activity compared with the norm, indicating restlessness or agitation, repetitive movements (such as grasping/picking at bedclothes, or tapping fingers), or making frequent sudden shifting of position.13 |

| Psychomotor retardation | An unusually reduced or slowed level of motor activity compared with the norm, such as sluggishness, staring into space, staying in one position for a long time, or moving very slowly. Decreased spontaneity of movement, and decreased verbal and motor responses are characteristic.13 | |

| FUNCTIONAL Dysfunction or decline in sleeping, performance of self-care activities, and continence. |

Sleep Disorder | Inability to sleep, stay asleep or excessive or inappropriate sleepiness. |

| Insomnia | Inability to fall asleep, waking up too early and being unable to get back to sleep, or restless, interrupted sleep. | |

| Hypersomnolence | Excessive sleep, manifested by late awakening, early sleep onset, or daytime sleeping. | |

| Sleep-wake cycle reversal | Prolonged awakening at night, excessive sleeping during the day, often associated with confusion about time of day. | |

| Decline or low performance in self-care activities | Usually manifested by an acute decline in an activity for which the patient was previously independent. For each of these activities, the decline could be either avolitional (inability to initiate the activity) or attentional (inability to effectively attend to the activity). Note that this acute decline should also not be better explained by a new foal disorder (e.g. gait difficulty due to a new hip fracture). | |

| Postural control | Inability to maintain a comfortable posture in bed, evidenced by a contorted posture (e.g. limbs under the body), limbs or head hanging off the bed, or falling out of bed. | |

| Poor oral intake | Acute decline in feeding, drinking and swallowing mechanisms that make it difficult to maintain nutrition or hydration, and increase risk of aspiration (choking). | |

| Self-care, appearance | Poor maintenance of grooming/hygiene as evidenced by acute inability to wash, brush teeth, comb hair or shave (men). |

Figure 1:

Final DEL-S-AD Content Domains for Delirium Severity in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias

Round 1.

Following Round 1, there were four items with consensus (Likert scores ≥ 7) for rating delirium severity in ADRD: Level of Consciousness; hallucination/perceptual disorder/distortion (Psychiatric-Behavioral); agitation (Psychomotor); and retardation (Psychomotor). There were six items with near consensus (mean Likert scores 3.5–6.5), including Inattention, delusions (Psychiatric-Behavioral), inappropriate behavior (Psychiatric-Behavioral), anger/hostility/irritability (Emotional Regulation), sleep disorder- insomnia (Functional) and sleep disorder- sleep wake cycle. There were 15 domains with no consensus (Likert scores ≤3). These included in the Cognitive domain disorientation, disorganized thinking, and cognitive impairment, in the Emotional Regulation domain, anxiety, fear/sense of unease, depression, apathy, and withdrawal, in the Functional- Sleep Disorder domain, hypersomnolence, and in the Functional- Performance domain, transferring, posture, gait/walking, poor oral intake, incontinence, and self-care/appearance. No new domains or subdomains were added during Round 1. We describe key discussion points from Round 1 (see Supplemental Material).

Round 2.

For Round 2, the domains and subdomains for which there was consensus or near consensus in Round 1 were not rated again (and were ultimately all included), with the exception of Sleep disorder- insomnia (Functional) which the BASIL study team/leaders returned for additional discussion/rating, bringing the number of domains and subdomains under consideration in Round 2 to 16. Following Round 2, there was consensus on one domain, Sleep disorder- hypersomnolence (Functional). There was near consensus on seven domains: disorganized thinking (Cognitive), depression (Emotional Regulation), withdrawal (Emotional Regulation), Sleep disorder- insomnia (Functional), and Performance- transferring (Functional), Performance- poor oral intake (Functional) and Performance- self/care appearance (Functional). There was no consensus on eight domains, including in the Cognitive domain, disorientation and cognitive impairment, in the Emotional Regulation domain, anxiety, fear/sense of unease, and apathy, and in the Functional domain posture, gait/walking, and incontinence.

With the follow-up survey, panelists ultimately decided to exclude seven subdomains: cognitive impairment in the Cognitive domain; anxiety, fear/sense of unease, and depression in the Emotional Regulation domain; and Performance- transferring, Performance- gait/walking, Performance-incontinence in the Functional domain. We illustrate panelists’ rationale for inclusion/exclusion of domains and subdomains as well as discussion of excluded domains (see Supplemental Material).

Three overarching discussion points arose with regard to design of the DEL-S-AD. One was temporality, specifically, whether the instrument would be designed to have assessors look at one point in time or at change over time. Panelists noted that acute and/or new changes are more consistent with delirium versus mild-moderate dementia alone. Another point was that the clinical setting should be considered, e.g., a hospital versus a rehabilitation or nursing home setting, but that it could be difficult to integrate setting into the instrument. Third was that there is a challenge to measurement in DSD: we may think we are measuring delirium severity, but if the instrument includes many symptoms of dementia, the result could be an instrument that would have high reliability and that would be strongly correlated with poor outcomes, but this would be because the instrument would be a dementia severity measure and not a delirium severity measure. Panelists noted that it was important to identify “the right” delirium symptoms among patients who may also have dementia so that when testing the DEL-S-AD, the proper constructs are measured.

DISCUSSION

We have described the process of our expert panel in identifying domains and subdomains to inform a new instrument for assessment of delirium severity among individuals with mild to moderate dementia, the DEL-S-AD. The final content domains endorsed by our panelists were Cognitive (subdomains: disorientation and disorganized thinking), Level of Consciousness, Inattention, Psychiatric-Behavioral (subdomains: delusion, inappropriate behavior, and hallucination/perceptual disorder/distortion), Emotional Dysregulation (subdomains: apathy/withdrawal and anger/hostility/irritability), Psychomotor Features (subdomains: psychomotor agitation and psychomotor retardation), and Functional (subdomains: sleep disorder with its own subdomains of insomnia, hypersomnolence, and sleep-wake cycle reversal; and decline or low performance in self-care activities with its own subdomains of poor postural control, poor oral intake, and self-care/appearance). These content domains differ from those identified for the DEL-S to assess general delirium severity with the exclusion of seven subdomains, including cognitive impairment in the Cognitive domain, anxiety, fear/sense of unease, and depression in the Emotional Regulation domain, and Performance- transferring, Performance- gait/walking, and Performance-incontinence in the Functional domain. These exclusions were made on the basis of not being able to definitively attribute them to delirium versus dementia.

Panelists debated how to accurately capture severity of delirium as it presents amidst dementia, a chronic, progressive disease with a clear symptom profile. For example, depression in ADRD has a different mix of clinical features than major depression in cognitively normal adults with more agitation and anxiety and fewer symptoms of hopelessness and suicidality. Issues of temporality and clinical setting add to this complexity. The DEL-S-AD includes those characteristics of delirium severity that can be assessed when persons have ADRD. In contrast, some other delirium features are frequently present with ADRD and are probably not useful for determining delirium severity when there is underlying ADRD. For example, function was discussed as an element that could set the DEL-S-AD apart from the DEL-S given that the nature of ADRD is functional decline as cognitive impairment progresses.

The strengths of this work include the broad interdisciplinary and international nature of our expert panel, the consistent participation of panelists in both review rounds, and use of a strong foundation of expert-identified domains of delirium severity. A limitation is that our expert panel could have been more diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and sex and did not include nursing home staff or family caregivers to offer input on delirium in ADRD; however, five panelists reported caring for family members with delirium and/or dementia.

The final content domains will inform item construction for the DEL-S-AD. With the expert panelists having defined what ought to be measured, our next steps are for the BASIL local expert panel to determine how to operationalize measurement in terms of item construction, response options, the time frame for assessment, and who should respond to each item (i.e., patient, family, nurse, assessor). We will test the instrument’s predictive validity for clinical outcomes. Ultimately, this instrument will be useful for providing person-centered clinical care for persons with ADRD who develop delirium— to develop domain-specific interventions, monitor response to treatment, estimate prognosis, communicate with families, minimize nursing burden, and optimize staffing-- and to advance research in this important area.

Supplementary Material

Key points:

Creation of a new instrument to assess delirium severity in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) is needed to better capture symptoms of delirium severity in a population that may already have attention, functional, and emotional changes at baseline.

Our expert panel identified content domains of delirium severity in ADRD to inform item development for the DEL-S-AD, a new instrument to measure delirium severity in individuals with mild to moderate dementia.

While experts endorsed the same content domains as for general delirium severity, they excluded six of the subdomains for general delirium severity on the basis of not being able to definitively attribute them to delirium versus dementia.

Why does this matter?

While our goal was to develop the DEL-S-AD, the expert panel process enabled rich discussion of the diverse views and challenges of identifying factors indicating delirium severity in AD. The DEL-S-AD can be used for both research and clinical purposes to improve the care of individuals with ADRD and will advance the field of delirium superimposed on dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is dedicated to the memory of Joshua B.I. Helfand.

Funding:

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging, grants #R01AG044518 and R33AG071744 to S.K. Inouye & R. Jones, MPIs.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, preparation, or decision to submit the paper.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dimitrios Adamis, Michael Avidan, Dan Blazer, Donna Fick, Tammy Hshieh, Richard Jones, Alessandro Morandi, Esther Oh, Catherine Price, Eva Schmitt, and Dena Schulman-Green have no conflicts. Catherine Price is supported by the National Institute on Aging, grant #K07AG066813. Joe Verghese has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and is an Editorial Board Member of JAGS and the Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material: Expert Panel Description and Discussion Points from Review Rounds 1&2

REFERENCES

- 1.Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–1174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns A, Iliffe S. Dementia. BMJ. 2009;338:b75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong TG, Davis D, Growdon ME, Albuquerque A, Inouye SK. The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(8):823–832. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong TG, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER, et al. Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):848–856, W296. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and Long-term Cognitive Trajectory Among Persons With Dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1324–1331. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inouye SK, Kosar CM, Tommet D, et al. The CAM-S: development and validation of a new scoring system for delirium severity in 2 cohorts. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(8):526–533. doi: 10.7326/M13-1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasunilashorn SM, Schulman-Green D, Tommet D, et al. New Delirium Severity Indicators: Generation and Internal Validation in the Better Assessment of Illness (BASIL) Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2020;49(1):77–90. doi: 10.1159/000506700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulman-Green D, Schmitt EM, Fong TG, et al. Use of an expert panel to identify domains and indicators of delirium severity. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(9):2565–2578. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02201-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hshieh TT, Fong TG, Schmitt EM, et al. The Better Assessment of Illness Study for Delirium Severity: Study Design, Procedures, and Cohort Description. Gerontology. 2019;65(1):20–29. doi: 10.1159/000490386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Conducting online expert panels: a feasibility and experimental replicability study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorm AF. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(10):887–897. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). User Manual for the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL) Measures, Version 2.0. Published online March 2015.

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition - Revised) (DSM-III-R). 3 Ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00316-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NIMH » Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/

- 19.Intro to PROMIS. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis

- 20.Rosenfeld RM, Nnacheta LC, Corrigan MD. Clinical Consensus Statement Development Manual. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(2 Suppl):S1–S14. doi: 10.1177/0194599815601394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.