Abstract

Cervical clear cell carcinoma (CCC) is a rare HPV-independent adenocarcinoma. While recent studies have focused on gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma (GTA), little is known about CCC.

58 (CCCs) were collected from 14 international institutions and retrospectively analyzed using univariable and multivariable methods and compared to 36 gastric type adenocarcinomas and 173 HPV-associated (HPVA) ECA regarding overall (OS) and recurrence free survival (RFS).

Most cases were FIGO stage I (72.4%), with Silva C pattern of invasion (77.6%), and the majority were treated with radical surgery (84.5%) and adjuvant therapy (55.2%). Lympho-vascular invasion was present in 31%, while lymph node metastasis (LNM) was seen in 24.1%; 10.3% were associated with abdomino-pelvic metastases at the time of diagnosis; 32.8% had recurrences and 19% died of disease. We did not find statistically significant differences in OS and RFS between CCC and GTA at 5 and 10 years (p=0.313 and p=0.508 respectively), but there were significant differences in both OS and RFS between CCC and HPVA ECA (p=0.003 and p=0.032, respectively). Also, OS and RFS in stage I clear cell and GTA were similar (p=0.632 and p=0.692 respectively). Multivariate analysis showed that OS is influenced by the presence of recurrence (p=0.009), while RFS is influenced by FIGO stage (p=0.025).

Cervical CCC has poorer outcomes than HPVA ECA and similar outcomes to HPV-independent GTA. Oncologic treatment significantly influences RFS in univariate analysis but is not an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis suggesting that alternative therapies should be investigated.

Keywords: clear cell carcinoma, gastric type, cervix, stage, prognosis

Introduction

There has been a recent paradigm shift in the classification of endocervical adenocarcinomas (ECA), with a move toward categorizing tumors by their etiologic link to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, as well as morphology. This new system has been adopted by the 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the female genital tract1,2. While nearly all squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix are caused by high-risk HPV infection, only approximately 85% of cervical adenocarcinomas are caused by HPV. The remaining 15% are caused by other factors independent of HPV2. HPV-independent (HPVI) ECA are comprised of gastric type (most common), clear cell, mesonephric and endometrioid carcinomas. Clear cell carcinoma (CCC) of the cervix is rare, accounting for less than 5% of all ECA1. While recent studies have focused on the poor outcomes of gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma (GTA), little is known about the outcomes of cervical CCC.

Clear cell carcinoma of the cervix and vagina have been linked to in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic estrogen derivative given to millions of pregnant women from the 1940s to 1970s3, 4. While a bimodal age distribution has been described in CCC, with peaks at 26 and 71 years, DES-exposed patients tend to be younger with peak age of 19 years; however, even with DES exposure, not all patients develop malignancies5–7. It is also well established that cervical CCC is not caused by HPV infection1,8–10. These data suggest that factors other than DES and HPV play an important role in the carcinogenesis of CCC, especially in older patients. However, the etiology and pathogenesis of these tumors are not well established, and no clear-cut precursor lesion has been identified, though a few reports suggest that some CCCs may develop from cervical endometriosis or tubo-endometrioid metaplasia11–13.

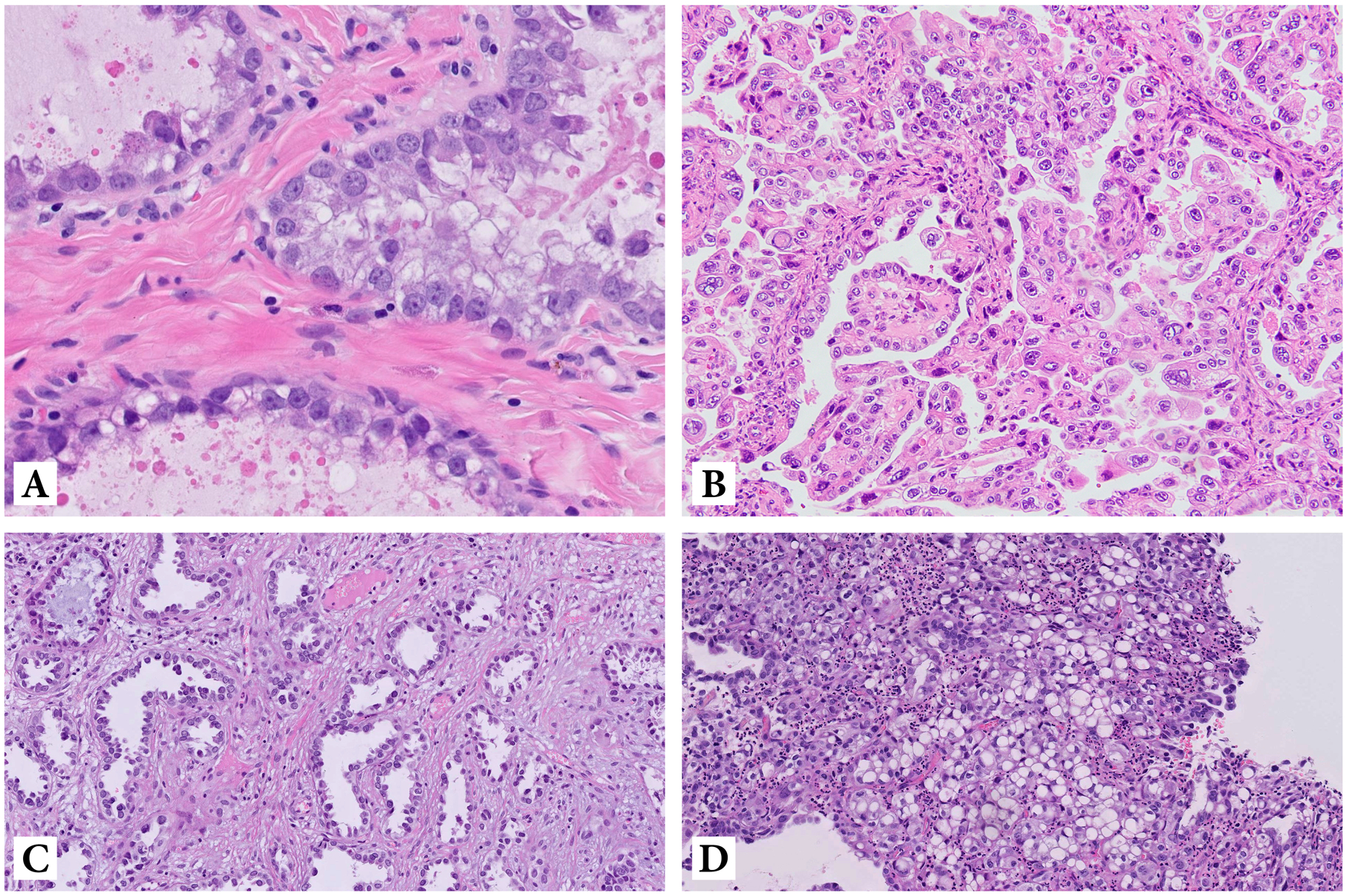

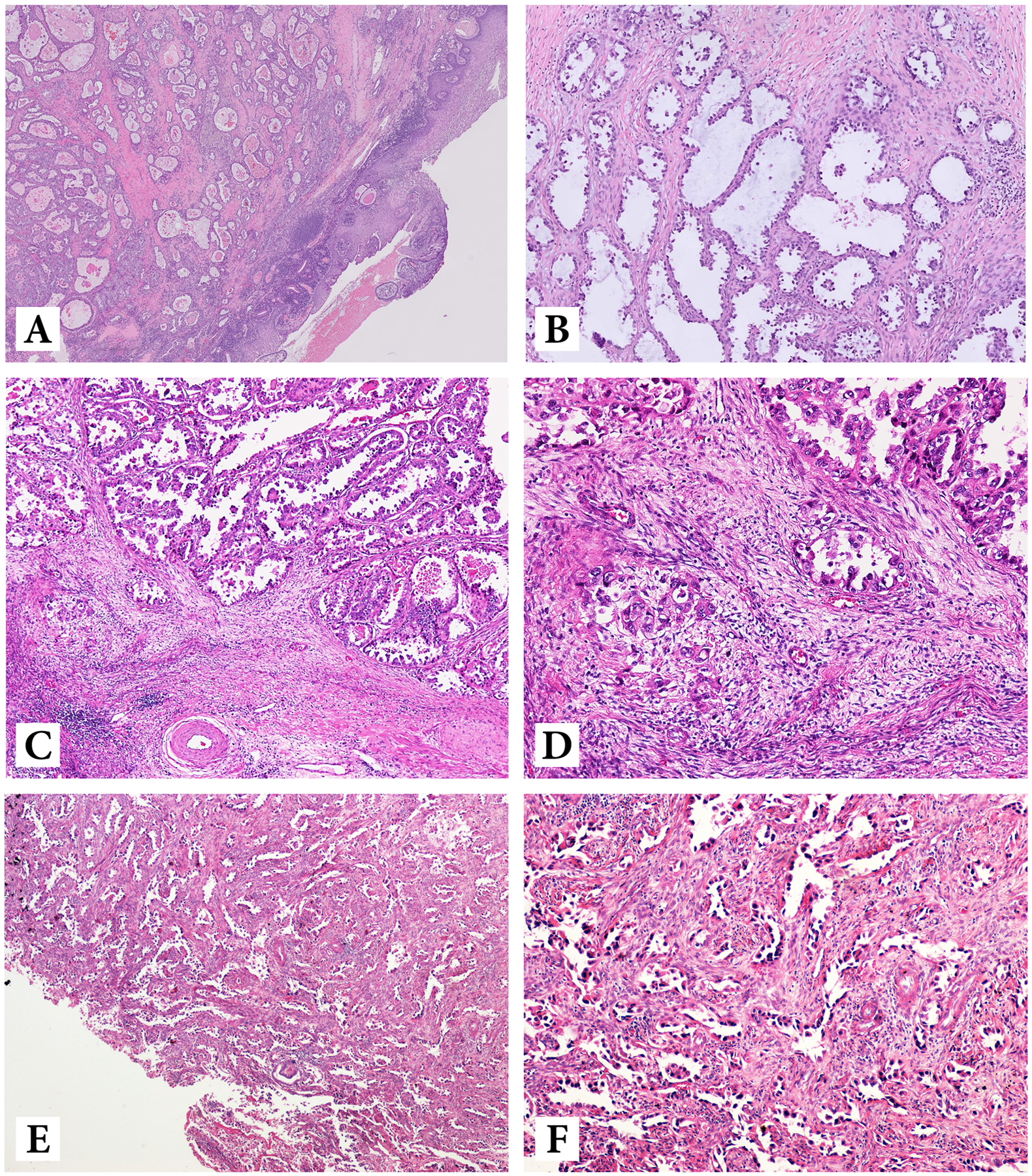

Morphologically, cervical CCC is identical to the endometrial and ovarian counterparts, with solid, tubulocystic and papillary architecture, often admixed within the same tumor. The tumor cells are characterized by abundant clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm with prominent cell membranes, hyperchromatic nuclei and low mitotic rate, and an oxyphilic variant with abundant eosinophilic, rather than clear cytoplasm has also been described as well as cases with tumor cells presenting with a signet-ring appearance (Figure 1). A recent study demonstrated that all HPVI ECA, including CCCs, have Silva pattern C destructive stromal invasion, though the data were limited for CCC14. In addition, we have observed Silva pattern A and B in cervical CCCs, particularly in small, early-stage tumors, as well as exophytic lesions. This has important implications regarding the differential diagnosis and management of CCC since application of the Silva pattern classification system to HPV-independent ECA is currently not recommended by the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists (ISGyP)15.

Figure 1:

Clear cell carcinoma: tubular structures lined by atypical tumor cells with abundant clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm (A); oxyphilic variant of clear cell carcinoma with tumor cells presenting with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (B); clear cell carcinoma with hobnail-type tumor cells (C) and with signet-ring tumor cells (D)

The prognosis of cervical CCC is stage dependent, yet the inherent risk associated with this histology is not well established. While recent work has demonstrated that HPVI ECA have worse prognosis than HPVA ECA, no study has looked specifically at a large cohort of CCC as compared to GTA16. Some case series have shown that CCCs have poor prognosis in terms of overall survival (OS), disease specific survival (DSS) and progression free survival (PFS). The largest series of cases published thus far included 34 patients with CCC comprised of 71% stage I, 6% stage II, 17% stage III and 6% stage IV17. That study focused on the optimal management of CCCs and showed that stage I and II CCCs demonstrated superior OS compared to advanced stage, but pelvic lymph node involvement was noted in 25% across all stages (stage I-IV). Moreover, while OS was 75% at 5 years, positive lymph nodes had a negative impact on 5-year OS and PFS in stage I and IIA17. The second largest study published by Jiang et al in 2014 analyzed 32 cases, demonstrating a 5-year PFS of 72.2% and with early stage (I-IIA) patients having a better 5-year PFS than those with advanced stage (IIB-IVB) (81.5% versus 40.0%)18. However, at present little is known regarding the prognosis of CCC compared to HPVA and other HPVI ECA such as GTA.

In this study, we aimed to analyze the clinico-pathologic parameters and outcomes of CCC compared to other HPV-independent (gastric type) and HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating center.

Case selection

CCCs were collected from 14 international institutions and retrospectively analyzed (University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology, Targu Mures, Romania; University Hospital of Saint-Etienne, France; Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge-IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain; Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; Vall d’Hebron Hospital, Barcelona, Spain; Universitair Medisch Centrum, Groningen, The Netherlands; Instituto Portugues de Oncologia, Lisbon, Portugal; University of Cagliari, Italy; Centro hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal; Hospital Universitario La Paz, IdiPaz; Center for Biomedical Research in the Cancer Network (CIBERONC); Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid; Madrid, Spain; University of Chicago, USA; Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto ON Canada; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, USA). Cases were also retrieved from International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC) database published in 20181. A live shared spreadsheet was created listing various clinico-pathologic parameters into which all participants of this study entered their own data. The study included biopsies (from patients without resection specimens but rather treated with chemo/radiotherapy), as well as loop electrocautery excision procedure (LEEP), conizations, trachelectomies, and simple/radical hysterectomies with or without lymph node samples. In addition, 36 GTA and 173 HPVA ECA (usual and mucinous types) were retrieved from the IECC database for survival comparisons1. In the previously reported IECC cases, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides containing tumor (an average of 12 slides per case) were examined at a multi-headed microscope and consensus diagnosis reached among three pathologists (RAS, KJP, and SS) in each case. In cases submitted by the various authors of this study, representative slides of each case were reviewed by the first and senior authors (SS and KJP) on either glass slides or digitally scanned images provided by the contributors. Each contributor reviewed full slides sets of their individual cases.

Morphologic assessment

All cases were classified according to WHO 2020 (derived from the IECC system) as HPVA and HPVI ECA1,2. Briefly, HPVA ECA harbor apical mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies easily seen at scanning magnification, while in HPVI ECA these features are lacking or limited. CCC was diagnosed by classic morphologic features - solid, papillary and/or tubulocystic architecture with uniformly atypical polygonal cells harboring clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm with hobnail features and dense stromal hyalinization1.

Tumors were also assessed for Silva pattern of invasion19. Briefly, pattern A tumors are composed of well-demarcated glands with rounded contours arranged in a vaguely lobular configuration without destructive stromal invasion, single cells, or lymphovascular invasion (LVI); pattern B tumors have only “early/limited” destructive stromal invasion (less than 5mm in diameter) in a background of pattern A, defined as small clusters or individual tumor cells in a focally desmoplastic stroma, and can have LVI; pattern C shows diffusely destructive stromal invasion by glands associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction and may be associated with LVI. The original Silva pattern classification study was restricted to HPVA ECA and therefore excluded CCC. While subsequent studies have shown HPVI ECAs to be uniformly classified as Pattern C, the data are limited for CCC and we wanted to study a larger cohort of these tumors to determine if they always show Pattern C invasion14,20.

In the course of routine work up, various immunohistochemical markers (HNF1beta, Napsin A, p53, p16, Vimentin, p63, ER, PR, DNA mismatch repair proteins), as well as HPV testing, were performed as deemed appropriate by the submitting pathologist (Table 1). The HPV in-situ hybridization testing method used in the IECC cases has been previously described in detail (1). The other cases tested for HPV used the same RNA-based technique or PCR-based testing. The following clinical parameters were retrieved from the data files of each institution: age at diagnosis, past medical history, 2009 FIGO stage, surgical treatment, adjuvant treatment, lymph node metastases (LNM), metastases in abdomino-pelvic organs, local recurrences, presence of distant metastasis, and survival data. OS was defined as the time from surgery until death by any cause. RFS was defined as the length of time the patient survived without any signs or symptoms of cervical cancer after completion of primary treatment. Each contributor reviewed full slide sets of their cases to determine Silva pattern and LVI.

Table 1:

Immunohistochemical profile and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) status in clear cell carcinomas

| Positivity (number of cases) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| HNF 1beta | 12/15 | 80% |

| Napsin A | 6/6 | 100% |

| MMR | 6/6 | 100% |

| p53 | 2/19 (aberrant) | 10.5% |

| p16 | 2/26 (diffuse, strong) | 7.7% |

| Vimentin | 0/1 | 0% |

| p63 | 0/1 | 0% |

| ER | 1/6 | 16.7% |

| PR | 0/7 | 0% |

| HPV | 0/16 | 0% |

Statistical analysis

Data were tabulated using Microsoft Excel software and analyzed using SPSS for Microsoft Windows, version 20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). The Kaplan-Meier test was used for survival curve estimates; and the log-rank Mantel Cox test was used for group comparisons. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, in univariate and multivariate analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Fifty-eight cases of CCC were retrospectively analyzed; 10 were retrieved from the original IECC study, while the remaining were submitted from individual authors. Mean age was 55.5 years (median 57.5; standard deviation: 19.93; range 10–84) with 19 patients (32.8%) ≤50 years and 39 patients (67.2%) >50 years old. In utero DES exposure was documented in only one 34-year-old patient.

Most patients (49, 84.5%) were treated surgically (cone, trachelectomy, hysterectomy with or without lymph node sampling), while 5 (8.6%) received definitive chemo/radiotherapy. No data was available regarding surgical treatment in 4 cases (6.9%). Most patients were also treated with adjuvant therapy (33 cases, 55.2%), while 21 (37.9%) were not. There was no data regarding adjuvant treatment in 4 cases (6.9%).

The FIGO (2009) stage breakdown of the 58 cases was as follows: 42 (72.4%) stage I; 9 (15.5%) stage II; 3 (5.2%) stage III; 3 (5.2%) stage IV; stage was not available (N/A) in 1 case.

While prior studies have shown that HPVI ECA always show Silva pattern C invasion, we found 5 (8.6%) pattern B and 2 (3.4%) pattern A cases of CCC, with the remaining (45, 77.6%) being pattern C (Figure 2). The CCCs with pattern A or B were early stage (I-IIA), some with exophytic growth. Silva pattern was not determined in 6 cases (N/A) due to biopsy only specimens. The impact of Silva pattern on prognosis was further analyzed (see below).

Figure 2:

Low- and high-power of Silva A (A, B), Silva B (C, D) and Silva C (E, F) pattern of invasion

Lympho-vascular invasion was present in 18 (31%), absent in 34 (55.2%) and not determined in 6 cases (10.3%). Lymph node metastasis (LNM) at the time of diagnosis was present in 14 (24.1%), absent in 42 (72.4%) and not reported in 2 (3.4%).

Mean follow up was 64.5 months (1–304 months). Abdomino-pelvic metastases at the time of diagnosis occurred in 6 (10.3%), while there were no metastases in 41 (70.7%); metastasis status was not reported in 11 cases (19%). Sites of synchronous metastases included ovary (1), uterine corpus (1), pelvis (1), vagina (1), spleen (1), omentum (1), sacrum (1), bladder wall (1), perirectal soft tissue (1), rectal mucosa (1) and para-aortic lymph nodes (1) with several patients having multisite involvement (omentum/spleen, ovary/pelvis, and bladder/perirectal/uterine corpus in three different patients). Nineteen patients (32.8%) recurred and 34 (58.6%) did not, while no information was available in 5 (8.6%). Eleven (19%) died of disease. Recurrences occurred in the lungs (6), liver (3), bones (3), brain (1), peritoneum (6), retroperitoneum (1), mediastinal lymph nodes (2), vagina (3) and sigmoid colon (2) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association analysis between clinico-pathologic parameters in 58 cases of clear cell carcinomas of the cervix

| Clear Cell Carcinomas | |

|---|---|

| Number of cases, (%) | |

| Total | 58 |

| Age Mean, Median (years) | 55.5 (57.5) |

| Std. Deviation, Range | 19.93 (10–84) |

| Age <50 years | 19 (32.8%) |

| ≥50 years | 39 (67.2%) |

| Surgical Treatment | |

| No | 5 (8.6%) |

| Yes | 49 (84.5%) |

| N/A | 4 (6.9%) |

| Adjuvant treatment | |

| No | 21 (37.9) |

| Yes | 33 (55.2%) |

| N/A | 4 (6.9%) |

| FIGO Stage | |

| Stage 1 | 42 (72.4%) |

| Stage 2 | 9 (15.5%) |

| Stage 3 | 3 (5.2%) |

| Stage 4 | 3 (5.2%) |

| N/A | 1 (1.7%) |

| Silva pattern | |

| A | 2 (3.4%) |

| B | 5 (8.6%) |

| C | 45 (77.6%) |

| N/A | 6 (10.3%) |

| LVI status | |

| Present | 18 (31%) |

| Absent | 34 (55.2%) |

| N/A | 6 (10.3%) |

| Presence of LNM | |

| Yes | 14 (24.1%) |

| No | 42 (72.4%) |

| N/A | 2 (3.4%) |

| Metastasis in abdomino-pelvic organ | |

| Yes | 6 (10.3%) |

| No | 41 (70.7%) |

| N/A | 11 (19%) |

| Recurrences | |

| Yes | 19 (32.8%) |

| No | 34 (58.6%) |

| N/A | 5 (8.6%) |

Abbreviations: LVI: lympho-vascular invasion; LNM: lymph node metastases; N/A: not available

The immunohistochemical profile of cervical CCC was as expected with most cases positive for Napsin A (100%) and HNF1Beta (80%); p16 was negative or showed patchy positivity in most cases with only 2 of 26 (7.7%) showing diffuse strong expression (aberrant). These cases were subsequently tested and negative for HPV by in situ hybridization and the aberrant p16 expression is likely due to an HPV-independent mechanism. While ER was negative in most cases, 16.7% showed some ER expression; 10.5% showed aberrant p53 expression (diffuse strong), while no cases showed “null” expression pattern. All tested cases were negative for vimentin, p63, PR and high-risk HPV (by in-situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction-PCR or both methods), while DNA mismatch repair proteins were retained in all cases (100%) (see Table 1 for details).

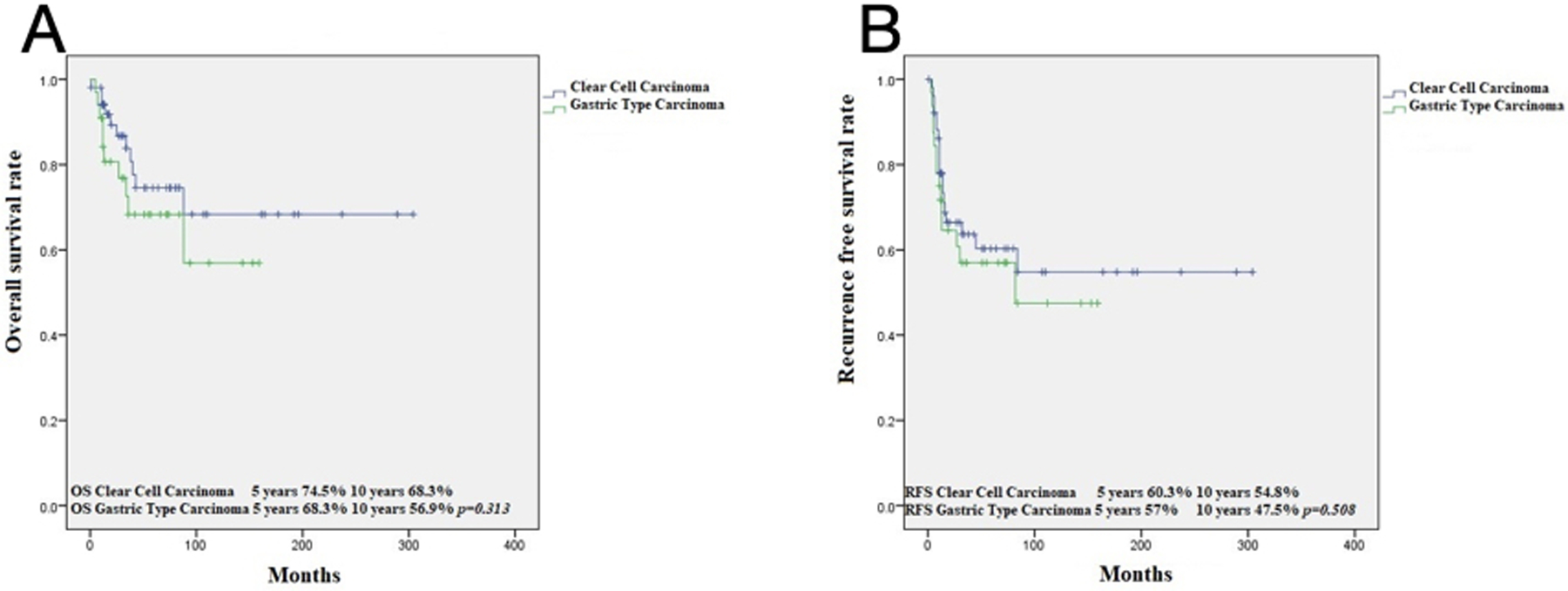

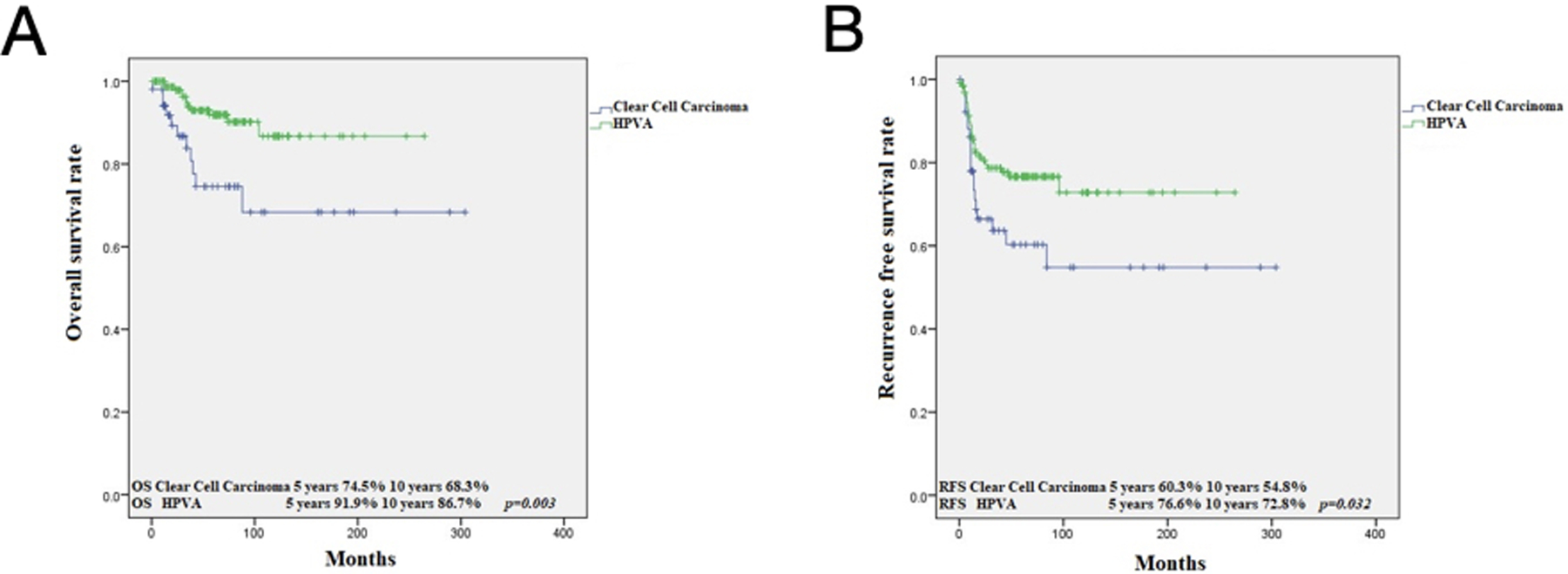

Comparison of survival outcomes between CCC and other ECA using Kaplan Meier analysis showed no statistically significant differences in 5- and 10-year OS or RFS between CCC and GTA; in contrast, there were significant differences between CCC and HPVA ECA.

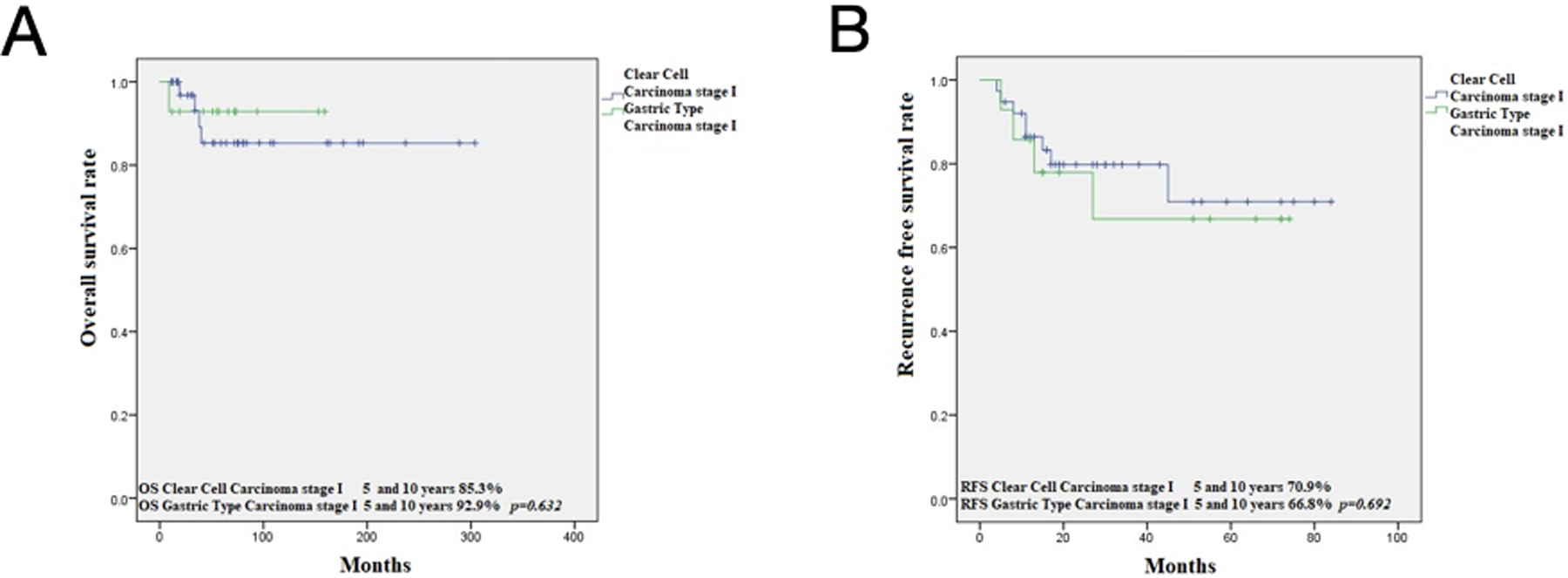

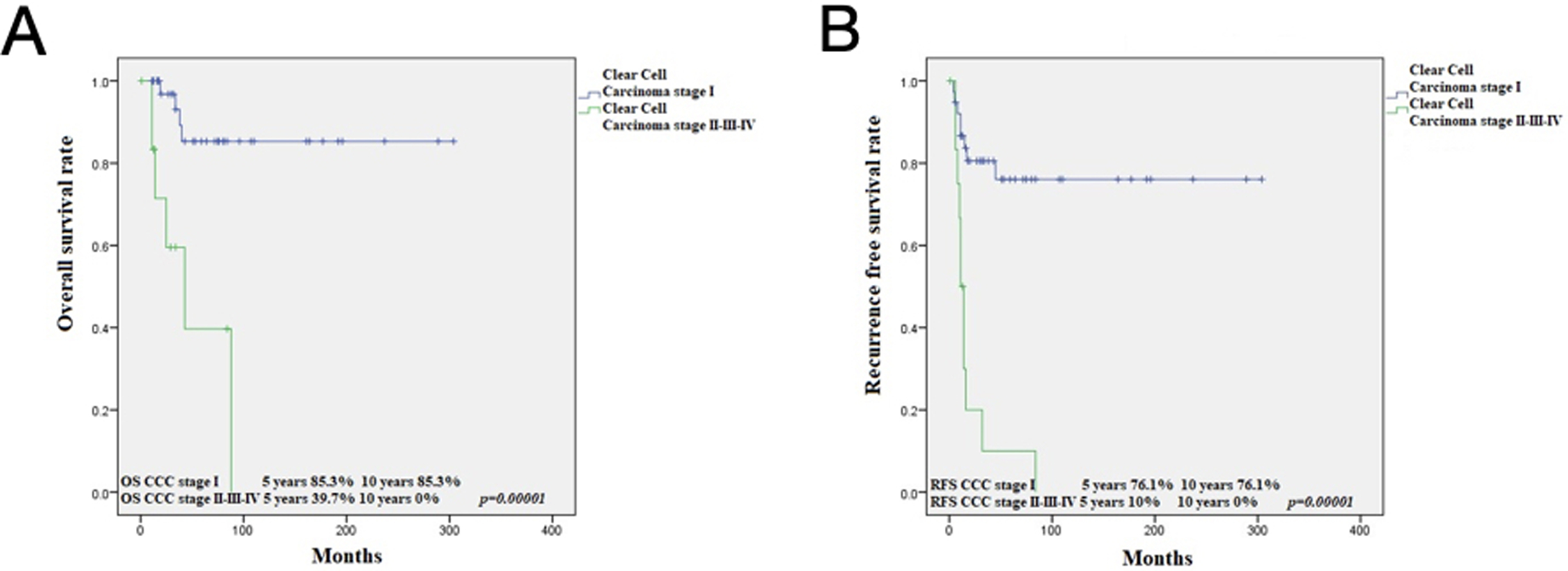

OS at 5 and 10 years for CCC was 74.5% and 68.3%, respectively, while for gastric type, it was 68.3% and 56.9% (p=0.313) (Figure 3). RFS at 5 and 10 years in CCC was 60.3% and 54.8%, respectively, while for GTA, it was 57% and 47.5% (p=0.508) (Figure 1). This is in contrast to 91.9% and 86.7%, 5- and 10-year OS in HPVA ECA, respectively (p=0.003) (Figure 4). Similarly, RFS for HPVA ECA at 5 and 10 years was 76.6% and 72.8% (p= 0.032) (Figure 4). In addition, OS and RFS in stage I CCC and GTA were similar (OS at 5 and 10 years 85.3% for CCC and 92.9% for gastric type, p=0.632; RFS at 5- and 10-years for CCC 70.9% and for gastric type 66.8% (p=0.692) (Figure 5). Moreover, OS in stage I CCC was 85.3% at both 5 and 10 years, while in stage II-IV it was 39.7% at 5 years and 0% at 10 years (p=0.00001) (Figure 6). RFS in stage I CCC was 76.1% at both 5 and 10 years, while in stage II-IV was 10% at 5 years and 0% at 10 years (p=0.00001) (Figure 6).

Figure 3:

Kaplan Meier analysis: OS in Clear Cell Carcinomas versus Gastric type ECA (A); RFS in Clear Cell Carcinomas versus Gastric type ECA (B)

Figure 4:

Kaplan Meier analysis: OS in CCC versus HPVA related ECA (A); RFS in CCC versus HPVA related ECA (B)

Figure 5:

Kaplan Meier analysis in FIGO stage I CCC versus stage I Gastric type ECA (A); FIGO stage I CCC versus stage I Gastric type ECA (B)

Figure 6:

Kaplan Meier analysis: OS in CCC stage I versus CCC stage II-IV (A); RFS in CCC stage I versus CCC stage II-IV (B)

Cox univariate analysis comparing clinico-pathologic parameters demonstrated that OS is influenced by whether or not the patient was treated surgically (HR=5.31; 95%CI=1.11–25.48; p=0.037), FIGO stage (HR=8.71; 95% CI=2.41–31.56; p=0.001), presence of LNM (HR=3.49; 95% CI=1.02–12.51; p=0.05) and presence of recurrences (HR=18.68; 95% CI=2.36–148.07; p=0.006), while RFS is influenced by receiving adjuvant treatment (HR=3.66; 95% CI=1.21–11.11; p=0.022), FIGO stage (HR=7.65; 95%CI=2.97–19.67; p=0.00001), presence of LVI (HR=2.98; 95%CI=1.06–8.34; p=0.038) and LNM (HR=9.06; 95% CI=3.46–23.75; p=0.00001) (Table 3). Multivariate analysis showed that OS is influenced by presence of recurrence (HR=25.4; 95% CI=2.24–288.42; p=0.009), while RFS is influenced by FIGO stage (HR=8.56; 95%CI=1.31–55.94; p=0.025) (Table 4, 5).

Table 3.

Survival analysis by Cox regression (univariate analysis) of parameters that influence overall survival (OS) and recurrence free survival (RFS) in 58 cases of CCC

| OS | RFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI 95% | p | HR | CI 95% | p | |

| Age | 2.1 | (0.45–9.76) | 0.346 | 1.21 | (0.46–3.18) | 0.71 |

| Surgical treatment (performed vs not) | 5.31 | (1.11–25.48) | 0.037 | 1.83 | (0.42–7.97) | 0.423 |

|

Adjuvant treatment

(received vs not) |

1.84 | (0.47–7.14) | 0.38 | 3.66 | (1.21–11.11) | 0.022 |

| FIGO Stage I vs II-IV | 8.71 | (2.41–31.56) | 0.001 | 7.65 | (2.97–19.67) | 0.00001 |

| Silva pattern A/B vs C | 1.11 | (0.14–9.16) | 0.921 | 2.21 | (0.29–16.78) | 0.443 |

| Presence of LVI | 1.18 | (0.29–4.81) | 0.82 | 2.98 | (1.06–8.34) | 0.038 |

| Presence of LNM | 3.49 | (1.02–12.51) | 0.05 | 9.06 | (3.46–23.75) | 0.00001 |

| Metastasis in abdomino-pelvis | 3.72 | (0.74–18.73) | 0.111 | 1.89 | (0.42–8.54) | 0.408 |

| Recurrences | 18.68 | (2.36–148.07) | 0.006 |

Abbreviations: LVI: lympho-vascular invasion; LNM: lymph node metastases

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors that influence overall survival (OS) in 58 cases of CCC by Cox regression

| HR | CI 95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical treatment | 8.00 | (0.97–66.33) | 0.054 |

| FIGO stage | 2,04 | (0.40–10.39) | 0.389 |

| Presence of LNM | 1.81 | (0.38–8.69) | 0.458 |

| Recurrences | 25.4 | (2.24–288.42) | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: LNM: lymph node metastases

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of factors that influence recurrence free survival (RFS) in 58 cases of CCC by Cox regression

| HR | CI 95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant treatment | 2.60 | (0.51–13.43) | 0.254 |

| FIGO stage | 8.56 | (1.31–55.94) | 0.025 |

| Presence of LVI | 1.26 | (0.40–4.00) | 0.696 |

| Presence of LNM | 1.39 | (0.29–6.72) | 0.683 |

Abbreviations: LVI: lympho-vascular invasion; LNM: lymph node metastases

Discussion

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignancy among women worldwide and is largely represented by squamous cell carcinoma, a tumor driven by high-risk HPV infection21. In contrast, adenocarcinomas comprise up to 25% of all cervical cancers and are a heterogeneous group of tumors, approximately 15% of which are HPV-independent1,2. These HPV-independent tumors have different morphologies, prognoses and molecular pathogenesis and this etiology-based classification has now been incorporated into the 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Female Genital Tract2. While there have been some recent studies looking at outcomes of HPV-independent tumors like gastric-type and mesonephric cervical adenocarcinomas, there have been no comparable studies evaluating cervical clear cell carcinomas22,23. In this study, we have demonstrated that rarely CCCs can have Silva A or B pattern of invasion (mostly in early stage and exophytic tumors), though due to the small number of cases, we cannot comment on whether this affects outcomes in this cohort. We did show that CCC outcomes are more similar to gastric-type adenocarcinoma, being worse than that of HPVA ECAs.

CCC is the second most common HPV-independent ECA, representing 3% of all cases in the IECC database1. These tumors can be associated with in-utero exposure to DES but can also occur sporadically. There is a bimodal age distribution with mean age of 19 in DES-exposed patients and 40 in non-DES-exposed patients1,24. However, CCC is rare even among DES exposed women (with an absolute risk of 1.9 to 2.3 per 1000); therefore, while DES exposure is an established cause of CCC, it may be an incomplete carcinogen and other genetic and environmental factors likely play an important role in tumor development24. In the present study, only one 34-year-old patient had a history of DES exposure.

Not much is known regarding the etiology and molecular underpinnings of CCCs. Boyd et al. showed that microsatellite instability was detected in all DES-exposed and half of non-DES exposed CCCs, while no mutations were detected in KRAS, HRAS, WT1, ER or TP5325. Mills et al. did not detect any association with Lynch syndrome, while in an immunohistochemistry-based study, Ueno at el. identified loss of PTEN, positive pAKT and p-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and HER2 amplification but without molecular correlation9,26.

All CCC have been classified as Silva pattern C to date and recent recommendations from ISGyP suggest that pattern of invasion should be applied only to HPVA ECA14. In our study, we did find 5 (8.6%) pattern B and 2 (3.4%) pattern A CCCs corresponding to small size, early-stage or exophytic polyp, without lymph node metastases. Four of the 7 cases were not associated with recurrences or death from disease and 2 patients died of other causes; however, there was one Silva pattern A that developed multiple recurrences within the abdomen, pelvis, retroperitoneal and mediastinal lymph nodes, bone and brain 5 months after the initial diagnosis. Moreover, the pattern of invasion was not found to be an independent prognostic parameter in both univariate and multivariate analysis, supporting that pattern classification of CCC is not clinically relevant, albeit our numbers were small.

Most studies have reported that CCC is a tumor associated with LVI and LNM. In the largest study by Thomas et al, pelvic lymph node involvement was noted in 25% of cases17. Similarly, we found LVI in 31% and LNM in 24.1% of our cases. In addition, 10.3% were associated with abdomino-pelvic metastases, 32.8% had recurrences and 19% died of disease. The sites of recurrence in our CCC were also very similar to gastric or mesonephric type, represented by lung, liver, bone, brain, peritoneum, retroperitoneum, mediastinal lymph nodes, vagina and sigmoid colon22,23.

There are no published data on the differences in prognosis between CCC and GTA and CCC and HPVA ECA. Other than case reports demonstrating that CCC have worse prognosis than usual HPVA ECA, the two largest studies did not correlate CCC survival with those of HPVA and/or with gastric type ECA since these studies were performed prior to the introduction of the etiology-based classification system17,18. The paper by Huo et al suggested that the prognoses of CCC and usual type are similar when controlled for stage24.

We did not find statistically significant differences in OS and RFS between CCC and GTA at 5 and 10 years but there were significant differences in both OS and RFS between CCC and HPVA ECA. OS and RFS in stage I clear cell and gastric type ECA were similar.

Cox univariate analysis demonstrated that OS is influenced by FIGO stage, presence of LNM, association with surgical treatment (inextricably linked to stage since early-stage patients have surgery and late stage get chemotherapy/radiotherapy), and presence of recurrences, while RFS is influenced by FIGO stage, presence of LVI, LNM and association with adjuvant treatment. However, multivariate analysis showed that OS is influenced by recurrence, while RFS is influenced by FIGO stage. As previously reported, we confirm that stage is an important predictor of OS and RFS, as all patients with II-IV CCCs were dead of disease at 10 years.

Conclusions

Cervical CCCs have poorer outcomes than HPVA ECAs and similar outcomes to HPV-independent gastric type adenocarcinoma. Stage is an important factor in prognosis with advanced stage having significantly worse outcomes than stage I. Oncologic treatment (definitive chemotherapy/radiotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy post-surgery) significantly influences RFS and surgical treatment influence OS in univariate analysis but are not independent prognostic factors in multivariate analysis. Since current treatments do not improve outcomes in patients with advanced stage CCCs, further studies on more targeted therapies should be pursued in future studies.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank to Gratian Boros and Monica Boros (Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Oradea, Romania) for performing the statistical analysis. Also, we would like to thank to Takako Kiyokawa (The Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) for providing some of the pictures related to Silva pattern of invasion.

Funding:

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 (Dr. Soslow, Dr. Park, Dr. Abu-Rustum).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L, et al. International endocervical adenocarcinoma criteria and classification (IECC): a new pathogenetic classification for invasive adenocarcinomas of the endocervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42: 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrington CS, Kim KR, Kong C, et al. Tumours of the uterine cervix. W. C. o. T. E. B. F. g. tumours. Lyon (France), International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020: 336–389. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbst AL, Scully RE. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina in adolescence. A report of 7 cases including 6 clear-cell carcinomas (so-called mesonephromas). Cancer, 1970; 25(4): 745–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman WJ, Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, et al. Registry of clear-cell carcinoma of genital tract in young women. N Engl J Med. 1971; 285(7): 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminski PF, Maier RC. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix unrelated to diethylstilbestrol exposure. Obstet Gynecol. 1983; 62:720–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanselaar A, van Loosbroek M, Schuurbiers O, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix. An update of the central Netherlands registry showing twin age incidence peaks. Cancer. 1997; 79: 2229–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbst AL. Behaviour of estrogen-associated female genital tract cancer and its relation to neoplasia following intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Gynecol Oncol. 2000; 76:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holl K, Nowakowski AM, Powell N, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type-distribution in cervical glandular neoplasias: results from a European multinational epidemiological study. Int J Cancer. 2015; 137(12): 2858–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueno S, Sudo T, Oka N, et al. Absence of human papillomavirus infection and activation of PI3K-AKT pathway in cervical clear cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013; 23(6):1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park KJ, Kyiokawa T, Soslow RA, et al. Unusual endocervical adenocarcinomas: an immunohistochemical analysis with molecular detection of human papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol, 2011; 35 (5): 633–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiromura T, Tanaka YO, Nishioka T, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix arising from a background of cervical endometriosis. The British Journal of Radiology, 2009; e20–e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stolnicu S, Talia K, McCluggage WG. The evolving spectrum of precursor lesions of cervical adenocarcinomas. Adv Anat Pathol, 2020; 27(5): 278–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talia KL, Arora R, McCluggage WG. Precursor Lesions of Cervical Clear Cell Carcinoma: Evidence For Origin From Tubo-Endometrial Metaplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2021; Mar 24. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000785. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L, et al. Stromal invasion pattern identifies patients at lowest risk of lymph node metastasis in HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas but is irrelevant in adenocarcinomas unassociated with HPV. Gynecol Oncol, 2018; 150 (1): 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarado-Cabrero I, Parra-Herran C, Stolnicu S, et al. The Silva pattern-based classification for HPV-associated invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma and the distinction between in situ and invasive adenocarcinoma: relevant issues and recommendations from the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2021; 40: S48–S65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stolnicu S, Hoang L, Chiu D, et al. Clinical outcomes of HPV- associated and unassociated endocervical adenocarcinomas categorized by the international endocervical adenocarcinoma criteria and classification (IECC). Am J Surg Pathol 2019; 43:466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas MB, Wright JD, Leiser AL, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the cervix: A multiinstitutional review in post-DES era. Gynecol Oncol, 2008; 109 (3): 335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Jin Y, Li Y, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: clinical characteristics and feasibility of fertility-preserving treatment. OncoTargets and Therapy, 2014. 7: 111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz De Vivar A, Roma AA, Park KJ, et al. Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma: proposal for a new pattern-based classification system with significant clinical implications: a multi-institutional study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013; 32:592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stolnicu S, Boros M, Hoang L, et al. FIGO 2018 stage IB endocervical adenocarcinomas: a detailed international study of clinical outcomes informed by prognostic biomarkers, including human papillomavirus (HPV) status. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2021; 31(2): 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8 (2):e191–e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karamurzin YS, Kiyokawa T, Parkash V, et al. Gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma: an aggressive tumor with unusual metastatic patterns and poor prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015; 39(11):1449–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pors J, Segura S, Chiu DS, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of mesonephric adenocarcinomas and mesonephric-like adenocarcinomas in the gynecologic tract: a multiinstitutional study. Am J Surg Pathol 2021; 45(5): 498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huo D, Anderson D, Palmer JR, et al. Incidence rate and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear- cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix: update after 40-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol, 2017; 146: 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd J, Takahashi H, Waggoner SE, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of clear cell adenocarcinomas of the vagina and cervix associated and unassociated with diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero. Cancer. 1996; 77(3): 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills AM, Liou S, Kong CS, et al. Are women with endocervical adenocarcinoma at risk for lynch syndrome: evaluation of 101 cases including unusual subtypes and lower uterine segment tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2012; 31(5):463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]