Abstract

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) pandemic has created significant and new challenges for the conduct of clinical research involving older adults with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD). It has also stimulated positive adaptations in methods for engaging older adults with ADRD in research, particularly through the increased availability of virtual platforms. In this paper, we describe how we adapted standard in‐person participant recruitment and qualitative data collection methods for virtual use in a study of decision‐making experiences in older adults with ADRD. We describe key considerations for the use of technology and virtual platforms and discuss our experience with using recommended strategies to recruit a diverse sample of older adults. We highlight the need for research funding that supports the community‐based organizations on which improving equity in ADRD research participation often depends.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, COVID‐19, qualitative research, racial and ethnic minorities

Key Points

COVID‐19 related restrictions on in‐person interactions with vulnerable populations, including older adults, create special challenges for reaching, engaging, and recruiting older adults with ADRD for clinical research studies.

We describe how we successfully transitioned to virtual technologies to recruit participants during the pandemic and conduct qualitative interviews with older adults with ADRD; these strategies hold promise for future research with this population.

Why does this matter?

Virtual approaches can be used effectively to reach, engage, and recruit older adults with ADRD for clinical research, but may require certain adaptations to standard practices. Community engagement and efforts to address disparities in access to technology will be especially important to ensure equitable participation in research.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 2 years, governmental and institutional policies 1 , 2 , 3 to mitigate the spread of COVID‐19 have dramatically affected clinical research. A key change has been the transition from in‐person to remote recruitment methods in accordance with physical distancing requirements. For research involving older adults with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD), this change has introduced new challenges to reaching, engaging, and recruiting participants. Moreover, for qualitative studies with older adults with ADRD, the transition to virtual technologies poses additional challenges in light of participants' cognitive impairment and potential difficulties with comprehension and expression.

As the pandemic was hitting Washington State in Spring 2020, we were beginning a five‐year R01 study funded by the National Institute on Aging to explore decision‐making regarding transitions to more supportive care (e.g., moving to a residential facility, hiring caregivers) among older adults with ADRD. The first phase of the study called for in‐person interviews with older adults with ADRD, their caregivers, and staff in clinical, residential, and community settings, with the goal of including participants across a range of cognitive abilities and sociodemographic characteristics. The second phase of the study aims to develop, design, and test a novel tool, based on discrete choice experiments, to identify the preferences of individuals with ADRD. This research seeks to find ways to foster the inclusion of individuals with ADRD in decision‐making about their own future care as their dementia progresses.

In this paper, we describe our experience navigating established approaches to research with older adults with ADRD within the context of the uncertain and unstable research environment that resulted from COVID, and the ways in which we adapted recruitment strategies, study protocols, and data collection procedures. Our goal is to reflect on lessons learned for engaging individuals with dementia and their caregivers in future research using virtual technologies and to share strategies that were effective and those that were less so. These insights may help inform the development of effective and robust research approaches for this population.

Recruiting and enrolling older adults with ADRD in the context of COVID‐19

General strategies

Given the increasing prevalence of dementia in the U.S. (estimated 18 million people by 2060) 4 – there is a critical need for research that incorporates the perspectives and experiences of individuals with ADRD to improve person‐centered care. Although the 2011 National Alzheimer Project Act fueled a dramatic increase in funding for research to address gaps in dementia care, few affected individuals are included or choose to participate in this research. 5 This is particularly true for racial and ethnic minorities. 6 , 7 , 8 Diverse representation is especially relevant for research on care decisions, as all populations affected by ADRD face similar primary challenges (e.g., increasing functional impairment and caregiving needs) but differ in the care they receive, reflecting the influences of race, ethnicity, income, access, and other social factors in addition to personal preferences. 9 , 10

Current recommendations to facilitate recruitment of older adults with ADRD in clinical research emphasize the need to leverage and improve existing ADRD registry infrastructure and to further develop community partnerships. 11 , 12 Additional strategies have been proposed to improve the recruitment of study participants from racial and ethnic minority groups and include: building trust through long‐term community partnerships; communicating information through trusted community partners; developing study initiatives that focus on community empowerment, needs, and priorities; minimizing barriers to participation (e.g., free transportation); and tailoring approaches to different groups and recognizing the heterogeneity within groups (e.g., Latinx, Asian American). 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Outreach and recruitment challenges

Informed by the recommended strategies described above, our original recruitment plan involved recruiting older adults with ADRD through clinical and non‐clinical settings such as outpatient clinics, senior centers, community organizations, nursing facilities, and memory care settings; places where we had pre‐existing relationships within the healthcare system and the community. Additionally, we had planned to recruit from venues that were located in more diverse neighborhoods, utilize partnerships with community‐based organizations, and build new relationships with organizations and senior centers that served local Black, Latinx, and Asian American communities, approaches that have been used successfully by ourselves and others 18 pre‐COVID.

However, restrictions on in‐person contact, particularly with older adults who were at especially high risk for illness and death from COVID‐19, 19 , 20 significantly limited access to our planned recruitment sites. The decline in outpatient clinical volumes, coupled with visitor restrictions at clinics, decreased the number of older adults and caregivers coming in for clinical visits and therefore opportunities to recruit from clinical settings. Senior centers and community organizations that serve adults with ADRD were either closed or had greatly reduced their services. Similarly, nursing facilities, assisted living facilities, memory care settings, and retirement communities restricted in‐person access.

While these challenges affected the recruitment of our study sample in general, additional challenges emerged related to the recruitment of participants from racial and ethnic minority groups in the context of disproportionately high rates of COVID‐19 related morbidity and mortality within these groups, 21 community organization staff layoffs, and economic hardship. Leaders of several community‐based organizations we had worked with previously described facing new financial and staffing challenges during the pandemic, while also experiencing increased requests to assist with study recruitment as a byproduct of increased federal funding for ADRD‐related research. Those serving minority communities also described being overwhelmed with requests to address transmission of COVID‐19 and, after vaccines were developed, access to vaccination. Additionally, the closure of community centers, faith centers, and day programs resulted in decreased access to many venues that serve larger racial and ethnic minority populations.

Strategies for recruitment: Engaging recruitment partners

To address these challenges to in‐person recruitment, we shifted focus from our proposed clinical and community settings to pre‐existing relationships (Figure 1). The University of Washington's Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC) was critical to providing access to older adults with ADRD and their caregivers who had already shown interest in participating in research and could be reached via phone or electronic means. Over half of older adults (17/33) and their caregivers (16/28) who were approached through the ADRC registry enrolled in the study and this comprised 70% of our older adult and 48% of our caregiver study sample.

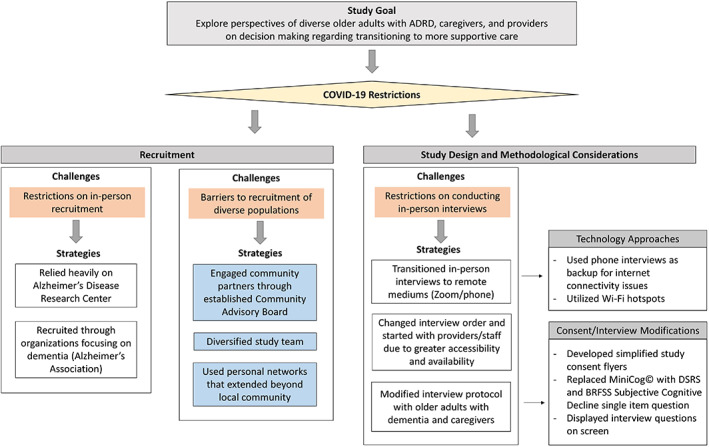

FIGURE 1.

Strategies and study modifications to address COVID‐19 related challenges

We utilized relationships with the Alzheimer's Association and other local organizations that had connections with individuals with ADRD and their caregivers through prior workshops and service provision. We also drew on prior relationships with staff from retirement communities with graduated levels of care to identify potential participants, disseminate information about the study, and promote snowball recruitment.

Heavy reliance on the ADRC registry had limitations in terms of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity. Participants in the ADRC registry are primarily white (84.5%), well‐educated (98.5% with at least a high school education), and required to be English‐speaking. Of the strategies to enhance recruitment of people from racial and ethnic minority groups that have been described previously, 18 the three that were at least partially successful for our study were: (1) accessing established relationships with community partners, (2) diversifying the study team, and (3) targeted outreach to personal networks (Figure 1).

Our existing partnership with the Community Advisory Board (CAB) at the University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center (https://depts.washington.edu/hprc/about/partners/community-advisory-board/), a CDC prevention research center established in 1986, provided an opportunity for us to engage with community leaders from African American, Latinx, Asian American, and Indigenous communities. This strategy for community engagement was key as we experienced challenges building new relationships with organizations that were overburdened and understaffed due to COVID‐19. Second, we sought to hire study staff from specific racial and ethnic minority communities with the goals of working together to develop sensitive and culturally‐appropriate recruitment strategies, building relationships with different communities, facilitating trust through racial concordance between study staff and participants, and increasing the diversity of perspectives within our study team. Hiring freezes due to COVID‐19 added further complexity to navigating an already limited pool of African American, Latinx, Asian American, and Indigenous research staff and researchers, but we were able to temporarily hire a bilingual Latinx research assistant, who had existing relationships with Latinx older adults in the context of a separate research study, to bolster our efforts with the recruitment of Latinx study participants. This approach was less successful in recruiting Asian American participants despite representation on our study team. A missed opportunity with this group was that we did not have the resources or expertise to conduct interviews in the languages spoken by many of the Asian populations served by our community partners. Our experience highlights the importance of designing studies with the resources needed to support the necessary work of adapting and translating study materials to include older adults with limited‐English proficiency. Lastly, we leveraged personal networks to identify eligible participants with diverse sociodemographic backgrounds, including contacts in other parts of the country. Being able to use these networks to recruit participants outside our geographic location was an unexpected benefit of the transition to virtual interviews.

Screening, consent, and conduct of interviews

Several changes needed to be made to the study protocol to address physical distancing restrictions that made in‐person interviews infeasible (Figure 1). We transitioned to conducting video interviews over Zoom, or to phone interviews in cases where using Zoom was not possible. We originally planned to begin our interviews with older adults with ADRD to ensure we heard their stories first. However, given the challenges to recruiting older adults described above, we chose to start with interviews with providers and staff (e.g., physicians, resident services coordinators) from clinic sites and residential facilities as they were more accessible. We were able to subsequently use some of these connections to identify eligible older adult and caregiver participants. This approach enabled our research team to become comfortable with phone and video consent and interview procedures with participants who were familiar with technology and without cognitive impairments.

We made several adaptations to facilitate the consent process for participants with ADRD for the virtual interviews. Input obtained from our CAB, and in particular from an older adult with ADRD and his family member who both serve on the CAB, were critical to informing these changes. We first developed an electronic flyer that supplemented the consent form but provided a simpler explanation of the study's purpose, activities, risks, and benefits in a more visual form; this flyer was reviewed by CAB members and revised accordingly. CAB members also suggested that we send written consent materials (via mail or email), which was viewed to be particularly important for those with hearing impairments in the context of video interaction, to participants prior to the interview. Next, after screening participants for eligibility over the phone or Zoom, we arranged a separate meeting over Zoom to review the consent form. During this meeting, research staff shared their screen, displaying the consent form in REDCap. Oftentimes, the participant would print out the consent form and flyer beforehand to have additional visual support during this process. Throughout the consent process, research staff implemented the “teach‐back” method 22 (i.e., after each section of the consent form) to ensure participant understanding; this was particularly helpful given the potential to miss certain non‐verbal or emotional cues over video. After reviewing the consent form and addressing all participant questions, the research staff obtained verbal consent in lieu of a signature. The research staff then selected the “I consent” option in REDCap and typed the participant's name into the appropriate field on the REDCap consent form.

Because many cognitive function screening instruments are designed for in‐person administration and have not yet been adequately validated in remote administration, we also had to reevaluate our choice of measures to assess cognitive deficit. We used a single question from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Subjective Cognitive Decline module 23 to identify awareness of cognitive changes and the proxy‐reported Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS) as a staging tool that can be administered via the phone or web. 24

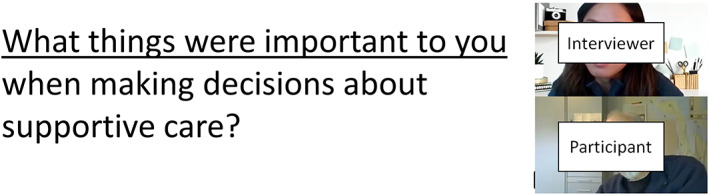

Lastly, based on input from our CAB, we made modifications to the protocol for video interviews. For example, we typed our questions in a large font on slides that we shared with the participant via Zoom (Figure 2), enabling them to reread the question and reorient themselves if needed as they were talking.

FIGURE 2.

Screenshot of interview with question displayed

Technological challenges and opportunities

Access to technology and technologic requirements for research using virtual mediums

We also needed to consider some of the technological challenges that exist for older adults to participate in research using virtual mediums. For example, many older adults lack videoconferencing capable devices or experience using them, 25 , 26 and people from racial and ethnic minority groups and those with lower socioeconomic status have lower rates of internet access (i.e., the “digital divide”) . 27 Even for those with internet access, many may not have the broadband speeds at home to utilize videoconferencing applications without buffering 28 and others may have unreliable internet connections. Lastly, not all devices have webcams, limiting the ability of the interviewer to see the participant.

We experienced some of these challenges in conducting video (Zoom) interviews. Participants who relied on public computers in their residential building had difficulty accessing these devices and the internet because COVID‐19 restrictions had closed shared spaces. Additionally, for participants who resided in independent retirement communities, staff who would normally step in to help with access and use of technology were often unable to assist due to staffing shortages and physical distancing requirements. Residents that had previously relied on communal computers prior to the pandemic were unable to access these shared spaces with computers and internet access. Finally, there were a variety of minor connectivity issues, for example, one participant temporarily lost the Zoom connection during the interview before realizing that the power cord was disconnected and reconnecting it. Issues of connectivity and clarity of the video and audio were not reserved to participants and occurred on occasion with the study staff who were also dependent on their home internet. High ping or lag times and network instability resulted in delays and instances when the connection was suddenly dropped. To address these challenges, we learned to discuss alternate plans ahead of time, including switching to phone interviews and utilizing Wi‐Fi hot spots to ensure reliable internet connection.

Familiarity and comfort with technology

Because of the technical knowledge necessary to navigate a videoconferencing platform in the home setting, we often had to rely on caregivers to assist participants with cognitive impairment. We thus had to weigh the tradeoffs between the importance of privacy for free sharing of participant experiences and the possible need for caregiver assistance to resolve technology issues. For example, in one interview, the caregiver stepped out of the room at the start of the interview, but when a pop‐up message appeared indicating the meeting was being recorded, the participant could not figure out how to close the message. Since the pop‐up remained on the screen during the entire meeting, the presentation slides with the interview questions could not be shared. Alternatively, when caregivers remained in the room for the interview, several participants turned to their caregivers to answer interview questions or caregivers interjected their own comments, altering participant responses. To mitigate this issue, study staff reminded participants at the beginning of the interview that the goal was to hear the older adult's perspective and experiences. Still, because caregiver interjections did occur, we employed several methodologic approaches to deal with these statements. Individual speakers were specified in interview transcripts (i.e., older adult, caregiver) so those caregiver interjections were marked as “caregiver” and they were also coded as “caregiver interjection.” Within the analysis of the interviews, then, we were able to decipher which themes were expressed by the older adult versus the caregiver, even if it was from an older adult transcript.

Privacy and security considerations

There were several privacy and security issues that we considered in the context of conducting remote interviews through Zoom. When we began our interviews in September 2020, Zoom had weak security protocols in place and did not offer end‐to‐end encryption for all accounts. To decrease the risk of unauthorized access to the interview session (i.e., “Zoom‐bombing”), we had research staff enable the “waiting room” feature on Zoom to control who was admitted to the session. In addition to considering the risk for these types of breaks in security protocol, particularly when interacting with participants who may share confidential information during the interview, we also needed to consider how to securely record interviews and store the recordings. A key consideration was that because platforms such as Zoom may retain recordings of the interview on their cloud‐based servers according to their terms of service, and data can be stored on servers around the world, these data could be subject to requests by government authorities. 29 We chose to save our interview recordings to our University's secured server instead of using cloud‐based storage. This approach, though, required that study staff, who were working remotely, be able to access the secured server at the time of the interview.

Key opportunities and considerations for future research

Our experiences navigating the challenges of COVID‐19 highlight several important areas in which the rapid increase in the use of technology and videoconferencing can facilitate future research with older adults with ADRD. Being able to conduct interviews virtually allows researchers to recruit from larger geographic regions in a more efficient and economical way, adding opportunities for diversified inclusion of harder‐to‐reach populations with low access to study sites, assuming a successful push to widen internet access. Virtual platforms can also remove some logistical barriers to recruitment and simplify scheduling and conducting interviews, as accommodation for transit time and access to and cost of transportation and parking is no longer needed for the older adult, caregiver, and interviewer. These efficiencies can facilitate the feasibility of conducting a larger number of interviews without significant increases in cost.

Additionally, the use of virtual mediums eliminates the need to travel to a clinical site and allows participation from home, 30 the environment in which older adults with ADRD are often most comfortable and familiar, without requiring study staff to physically come into the home which may be uncomfortable for some. This eliminates potential impediments to participation that arise from ADRD‐related difficulty adjusting to unfamiliar surroundings. In our study, several participants volunteered that doing the interview over Zoom made it much easier to participate and at least one stated that he would not have been able to participate otherwise. Furthermore, caregivers are able to help the older adults with ADRD during the interview if needed, from the comfort of home, though issues related to privacy and influence need to be considered. The use of video technology also overcomes some of the challenges to building rapport and exchanging non‐verbal communication that occurs with telephone interviews. Finally, the use of videoconferencing platforms has made it easier than ever to video‐record interviews. Compared to audio recordings, the use of video recordings can provide the opportunity to analyze non‐verbal behaviors in addition to verbal interview responses.

CONCLUSION

Our experience applying and adapting previously established research approaches to a qualitative study of older adults with ADRD yielded multiple insights. We found that virtual technologies could successfully be used in light of physical distancing restrictions to conduct qualitative research with older adults with ADRD but required careful planning and multiple modifications to the study protocol. We used several strategies to address the complexity of navigating videoconferencing technology with this population including providing reminders throughout the interview for how to navigate the technology, using screen share to show questions, and partnering with caregivers to assist if needed. Although we did experience some challenges, we found that the majority of interviews went smoothly and those older adults with early to moderate ADRD were able to participate successfully.

While the use of videoconferencing platforms potentially enables researchers to reach more diverse populations around the country in an efficient and economical way compared to the traditional approach of multi‐site studies, additional ways to overcome disparities in access to technology will need to be addressed to improve equity in research participation. Short‐term solutions could include budgeting for devices and data plans as part of research expenses, as well as ensuring that study staff has knowledge of local programs and services for low‐cost broadband and can assist participants with access to these programs.

Our experience also illustrates ways in which the pandemic has created additional challenges to recruiting diverse populations for research involving older adults with ADRD, and highlights the critical role of having strong pre‐existing relationships with community partners. Given the rapid growth of ADRD‐related research, explicit support by research funders is needed to develop and sustain partnerships with community‐based organizations that serve diverse populations. Institutional investment is needed for strong academic‐community partnerships and building and maintaining under‐utilized resources such as Community Advisory Boards with funds to compensate people for their time. Finally, opportunities remain for centers such as the ADRCs, which are an especially important resource for advancing ADRD research, to employ more robust strategies to increase recruitment of participants from groups that are underrepresented in research. While COVID‐19 will hopefully be in our rear‐view mirror in the near future, we believe the lessons learned during this time will have important implications for approaches to advance research with older adults with ADRD and their families.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed to manuscript conception, drafting, revision, and final approval.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG066957. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study participants, study team members and students, study community advisory board, and participating organizations. The authors also wish to thank Alyssa Bosold for providing edits to the manuscript.

Sharma RK, Teng A, Asirot MG, Taylor JO, Borson S, Turner AM. Challenges and opportunities in conducting research with older adults with dementia during COVID‐19 and beyond. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(5):1306‐1313. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17750

Funding informationResearch reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG066957.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Omary MB, Eswaraka J, Kimball SD, Moghe PV, Panettieri RA, Scotto KW. The COVID‐19 pandemic and research shutdown: staying safe and productive. J Clin Investig. 2020;130(6):2745‐2748. doi: 10.1172/JCI138646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harper L, Kalfa N, Beckers GMA, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 on research. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(5):715‐716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tuttle KR. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on clinical research. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(10):562‐564. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-00336-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(2):121‐129. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reuben DB. The voices of persons living with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(4):443‐444. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabinowitz YG, Gallagher‐Thompson D. Recruitment and retention of ethnic minority elders into clinical research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(Suppl 1):S35‐S41. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f12869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Provencher V, Mortenson WB, Tanguay‐Garneau L, Bélanger K, Dagenais M. Challenges and strategies pertaining to recruitment and retention of frail elderly in research studies: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(1):18‐24. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mooldijk SS, Licher S, Wolters FJ. Characterizing demographic, racial, and geographic diversity in dementia research: a systematic review. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(10):1255. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharma RK, Kim H, Gozalo PL, Sullivan DR, Bunker J, Teno JM. The Black and White of invasive mechanical ventilation in advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(9):2106‐2111. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richardson VE, Fields N, Won S, et al. At the intersection of culture: ethnically diverse dementia caregivers' service use. Dementia. 2019;18(5):1790‐1809. doi: 10.1177/1471301217721304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute on Aging . Together We Make the Difference. National Strategy for Recruitment and Participation in Alzheimer's and Related Dementias Clinical Research. 2018. https://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-10/alzheimers-disease-recruitment-strategy-final.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Bartlett R, Milne R, Croucher R. Strategies to improve recruitment of people with dementia to research studies. Dementia. 2019;18(7‐8):2494‐2504. doi: 10.1177/1471301217748503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Denny A, Streitz M, Stock K, et al. Perspective on the “African American participation in Alzheimer disease research: effective strategies” workshop, 2018. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(12):1734‐1744. doi: 10.1002/alz.12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Massett HA, Mitchell AK, Alley L, et al. Facilitators, challenges, and messaging strategies for Hispanic/Latino populations participating in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias clinical research: a literature review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(1):107‐127. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haley SJ, Southwick LE, Parikh NS, Rivera J, Farrar‐Edwards D, Boden‐Albala B. Barriers and strategies for recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities: perspectives from neurological clinical research coordinators. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(6):1225‐1236. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0332-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDougall GJ, Simpson G, Friend ML. Strategies for research recruitment and retention of older adults of racial and ethnic minorities. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41(5):14‐23. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20150325-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span study. Gerontologist. 2011;51 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S33‐S45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilmore‐Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, et al. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer's disease research: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;5(1):751‐770. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand JA, Treggiari MM. COVID‐19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1742. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09826-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926‐929. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muñoz‐Price LS, Nattinger AB, Rivera F, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcomes among patients with COVID‐19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2021892. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sudore RL, Seth Landefeld C, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867‐873. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Published online 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2019-BRFSS-Questionnaire-508.pdf

- 24. Moelter ST, Glenn MA, Xie SX, et al. The Dementia Severity Rating Scale predicts clinical dementia rating sum of boxes scores. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(2):158‐160. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anderson M, Perrin A. Tech Adoption Climbs Among Older Adults. Published online May 17, 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/

- 26. Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1386‐1389. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoon H, Jang Y, Vaughan PW, Garcia M. Older adults' internet use for health information: digital divide by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(1):105‐110. doi: 10.1177/0733464818770772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drake C, Zhang Y, Chaiyachati KH, Polsky D. The limitations of poor broadband internet access for telemedicine use in rural America: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(5):382. doi: 10.7326/M19-0283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aiken A. Zooming in on privacy concerns: video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think. Index Censorship. 2020;49(2):24‐27. doi: 10.1177/0306422020935792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harrison KL, Leff B, Garrigues SK, et al. Virtual research stakeholder groups with isolated homebound elders and caregivers: lessons learned relevant to research during pandemics. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(4):481‐483. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]