Abstract

Background:

One in five older adults (age 65+) uses an antidepressant medication. However, little is known about how fall risk differs between commonly prescribed medications. We examine the comparative association between individual selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and self-reported falls in older adults.

Methods:

We used data from 2010–2017 Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries. We included participants from three different panels surveyed over two successive years. Participants were limited to community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries 65+, enrolled in Medicare Part D, and taking an SSRI (n=1023) during baseline years. Participants were asked about demographic and health characteristics, medication use (including dose, frequency, duration of use) and self-reported falls as any fall or recurrent falls in the past year. We compared individual SSRI (citalopram or escitalopram vs sertraline) use by the average monthly total standardized daily dose (TSDD) and self-reported falling, controlling for potential confounders. Descriptive analysis and multivariable logistic regressions were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN.

Results:

Citalopram/escitalopram (n=460 users; 45.0% of all SSRI users) and sertraline (n=294 users; 28.7% of all SSRI users) were the most commonly prescribed SSRIs. Overall, 36.3% of citalopram/escitalopram users and 39.4% of sertraline users reported a fall in the year following medication use. There were no statistically significant differences between sertraline and citalopram/escitalopram users of either low or medium TSDD levels in the risk of self-reported any or recurrent falls. However, users of high TSDD of sertraline (>75 mg) had a lower risk of recurrent falls compared to high TSDD citalopram (>30 mg) or escitalopram (>15 mg) daily for 30 days.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest a potential comparative safety benefit of sertraline compared to citalopram/escitalopram at high doses related to recurrent falls. Additional comparative studies of individual antidepressants may better inform fall risk management and prescribing for older adults.

Keywords: Older Adults, falls, antidepressants, SSRIs

Introduction

Clinically significant depressive symptoms affect approximately 15% of community-dwelling older adults (65 years and older) in the United States.1,2 Older adults with medical comorbidities have even higher rates of depressive symptoms; for example, those diagnosed with stroke (up to 60%) or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (up to 40%).3 Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for falls in older adults, increasing the risk of falling by approximately 50%.4,5 While depression is associated with falls, treatment with certain antidepressant medications has also been associated with increased risk of falls in older adults.6–9

One in five older adults uses an antidepressant, and the most commonly used sub-class is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI).6,10,11 Despite the frequent use of antidepressants by older adults, little is known about how fall risk differs between commonly prescribed individual antidepressants. Previous studies examining the association between antidepressant users and non-users (e.g., SSRI use vs. no SSRI use) reported an increased fall risk in older adults.8,9 Studies comparing antidepressant users versus non-users are susceptible to confounding by indication, meaning that the fall event may have been due to the underlying depression for which the drug was prescribed rather than to the drug itself.

The 2019 American Geriatric Society (AGS) Beers Criteria recommend against using SSRIs, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in older adults with a history of falls or fracture.9 This makes pharmacological treatment of depression in older adults at risk of falling challenging. Treating depression with antidepressant medications remains the mainstay in clinical practice,2 and SSRIs are commonly used as first-line treatment for depression in older adults due to greater tolerability compared to highly anticholinergic TCAs.12,13 One way to further explore the risk or benefits of one pharmacological treatment compared to others is to conduct a comparative analysis within the SSRI subclass. Comparative studies compare two or more active (non-placebo) interventions for efficacy, safety, and side effect profiles.

In this study, we examined the comparative association between commonly prescribed individual SSRIs and self-reported falls in community-dwelling older Americans, controlling for potential confounding.

Methods

We used the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). MCBS is an ongoing panel survey of a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries who are selected from Medicare enrollment files. Survey participants are interviewed in-person three times per year over a four-year period. We combined data from multiple survey waves between 2010 and 2017 to maximize sample size and increase analytic power. Demographic, functional, health, and medication use data are collected from each participant or a proxy using computer-assisted in-person interviews conducted by a panel survey interviewer. Demographic data are collected at enrollment when older adults join the study. Health conditions and functional characteristics are collected at enrollment and once a year during the autumn months’ survey. Medication use data are collected three times a year.14

Study Design & Participants

Subjects were included in this study if they were surveyed in successive years (2010–2011 or 2012–2013 or 2016–2017). The survey years 2014–2015 were not included in this study, as 2014 data was not released by CMS due to a change in MCBS data collection process in 2014.15 The response rate for baseline years as reported from MCBS was 62.4% for 2010, 62.3% for 2012, and 72.0% for 2016.16 We included adults who were aged 65 years or older at baseline year (2010, 2012, 2016), community dwelling and alive in the next year, used an SSRI during the medication exposure window of the study period (January to August of baseline years 2010, 2012, 2016), and had a participating Medicare Part D plan for prescription data. We limited eligibility to Medicare Part D enrollees because medication use variables such as day supply, quantity received, and prescription date were only available for these Medicare beneficiaries.

Demographic characteristics and health status were collected between September and December of baseline years. Health characteristics were assessed as a report of ever having a condition or in the past year (Supplemental Figure 1). We limited medication use data to the months of January to August in the baseline years 2010, 2012, 2016, including only psychoactive medications associated with increased risk of falls as described by the AGS’s Beers Criteria.9 SSRIs were the primary exposure of interest.

Outcome

MCBS only asks questions about falls in the autumn months’ surveys of odd years. For our study, fall outcome information was ascertained in the years of 2011, 2013, and 2017 from September to December. Responses to the questions, “Have you fallen down in the past year?” and “How many times have you fallen down in the past year?” were used to measure our two primary outcomes of interest - any fall in the past year (henceforth referred to as any fall following medication exposure) and recurrent falls in the past year (henceforth referred to as recurrent falls following medication exposure). Thus, the fall questions posed in the autumn months of successive years captured any fall that had occurred from September of the previous year (i.e., baseline year), which was when the measurement of SSRI use ended (Supplemental Figure 1). This design was used to establish an appropriate temporal relationship for the exposure (SSRI use) to come before the outcome (self-reported falls) assessment.

Measures

MCBS participants are asked to save prescription containers and payment receipts to show the panel survey interviewer at the time of the survey. This minimizes underreporting of medication use and increases validity of self-reported medication use. To measure medication use, MCBS classifies medications by their generic and commercial names. Medications were categorized into pharmacologic class by a pharmacist using Lexicomp and package inserts. We identified six SSRIs used during the study years (citalopram, escitalopram, paroxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and sertraline). Due to the small number of participants using some of these SSRIs, we limited our analysis to sertraline and a group combining citalopram and escitalopram as they are structurally similar chemicals known as enantiomers (mirror images) with similar mechanisms of action.

Using the following steps, we calculated an average monthly total standardized daily dose (TSDD) for every participant using the SSRI of interest during the medication exposure window. First, a standardized daily dose (SDD) was calculated for each medication prescribed. The SDD was calculated as [(dose prescribed for medication * the number of tablets prescribed) / minimum initial effective geriatric dose of the medication], as described in previous studies.17,18 We used 10 mg citalopram, 5 mg escitalopram, and 25 mg sertraline for the initial effective geriatric dose.19 A TSDD was then calculated by summing the SDDs for all prescriptions an older adult received for that medication between the months of January to September. The average monthly TSDD was obtained by dividing the TSDD by the number of months the SSRI was prescribed between January to September. In order to facilitate dose level interpretation and due to the lack of ascertained dose/duration levels on monthly TSDD in the literature, we categorized the continuous average monthly TSDD variable by examining its data distribution. The cut-off points in the average monthly TSDD data were determined by first identifying tertiles in the data distribution. The 33rd and 66th percentiles in the average monthly TSDD of citalopram/escitalopram use were 57 and 70. The 33rd and 66th percentiles in the average monthly TSDD of sertraline use were 59 and 96. In order to facilitate easy interpretation and comparison between the two groups, the cut-off points of 60 or less (low), 60.1–90 (medium), and 90.1 and more (high) were chosen. Among citalopram/escitalopram users, 40% had low average monthly TSDD (equivalent to ≤20 mg citalopram daily for 30 days; or ≤10 mg escitalopram daily for 30 days), 31% had medium TSDD (equivalent to >20 to 30 mg citalopram daily for 30 days; or >10 to 15 mg escitalopram daily for 30 days), and 28% had high TSDD (equivalent to >30 mg citalopram daily for 30 days; or >15 mg escitalopram daily for 30 days). Among sertraline users, 39% had low average monthly TSDD (equivalent to ≤50 mg sertraline daily for 30 days), 25% had medium TSDD (equivalent to >50 to 75 mg sertraline daily for 30 days), and 36% had high TSDD (equivalent to >75 mg daily sertraline for 30 days) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Equivalent monthly doses for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors of interest -– Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, 2010–2017.

| Average Monthly Total Standardized Daily Dose (TSDD) categories1 | Monthly equivalent dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | Escitalopram | Sertraline | |

| Low TSDD ≤60 | ≤20 mg daily for 30 days | ≤10 mg daily for 30 days | ≤50 mg daily for 30 days |

| Medium TSDD = 60.1–90 | >20 to 30 mg daily for 30 days | >10 to 15 mg daily for 30 days | >50 to 75 mg daily for 30 days |

| High TSDD >90 | >30 mg daily for 30 days | >15 mg daily for 30 days | >75 mg daily for 30 days |

Total standardized daily dose (TSDD) = (Sum of Standardized daily dose (SDD) during exposure window/total months taken during exposure window).

Standardized daily dose (SDD) = (dose prescribed for medication * the number of tablets prescribed) / minimum initial effective geriatric dose of the medication.

In addition to SSRIs, we identified six other psychoactive medication classes: opioids, benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics (non-benzodiazepines limited to zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone), antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and other antidepressants. We created a separate count variable with the total number of different psychoactive medications (excluding SSRIs) used by each participant to serve as a covariate.

The following additional variables served as covariates based on current evidence of factors associated with falls in older adults: age, sex, race, past year self-reported health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), fall history, and ever being diagnosed with certain health conditions (depression, diabetes, and stroke).5,20 The mean number of other psychoactive medications used during the medication exposure window of January to August in baseline years was also used as a covariate. Psychoactive medications were used as a covariate because they are independently associated with an increased risk of falls in older adults.9

Statistical Analysis

The three cohorts were combined into a single analytic dataset. We conducted descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses, taking into consideration the complex survey design elements using replicate and 2-year longitudinal weights.15 We reported weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the descriptive analyses. Chi-square tests were used to compare differences between citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline users by demographic and health characteristics. We computed unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs using logistic regression. Adjusted risk ratios were produced by controlling for demographics (age, sex, race), and health characteristics (self-reported health status, fall history, select health conditions (diabetes, depression, stroke)), and concurrent psychoactive medication use as the mean number of psychoactive medications excluding SSRIs. Any respondents with missing values or responses of “Don’t know” or “Refused” for a variable were excluded from analyses using those variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 11; RTI International).

Results

In our sample of older adult SSRI users (n=1,023), 45.0 % (n=460) used citalopram or escitalopram and 28.7 % (n=294) used sertraline. Table 2 shows demographic and health characteristics of the sample, comparing citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline users. Among both citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline users, more respondents were female. For citalopram/escitalopram users, 77.4% were female; for sertraline users, 71.3% were female. Among citalopram/escitalopram users, 58.0% were 65–74 years old, 31.3% were 75–84 years old, and 10.7% were 85 years and older. For sertraline users 57.1% were 65–74 years old, 31.7% were 75–84 years old, and 11.3% were 85 years and older. Other than sex (p<0.05), there were no significant differences between citalopram/escitalopram users and sertraline users by demographic, health characteristics or concurrent psychoactive medication use.

Table 2:

Characteristics of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at baseline years (2010, 2012, 2016) – Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, 2010–2017.

| Citalopram or escitalopram (n=460) |

Sertraline (n=294) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | na | Weighted %b | 95% CIc | na | Weighted %b | 95% CIc |

| Age | ||||||

| 65–74 | 222 | 58.0 | 54.8–61.1 | 140 | 57.1 | 52.1–62 |

| 75–84 | 170 | 31.3 | 28.3–34.5 | 111 | 31.7 | 27.6–36.1 |

| 85+ | 68 | 10.7 | 9.2–12.4 | 43 | 11.3 | 8.9–14.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 106 | 22.6 | 19.8–25.7 | 85 | 28.7 | 24.9–32.8 |

| Female | 354 | 77.4 | 74.3–80.2 | 209 | 71.3 | 67.2–75.1 |

| History of falls | ||||||

| No | 262 | 58.3 | 55.0–61.6 | 158 | 54.8 | 50.1–59.4 |

| Yes | 181 | 41.7 | 38.4–45.0 | 128 | 45.2 | 40.6–49.9 |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 412 | 89.5 | 87.0–91.6 | 264 | 86.3 | 81.7–89.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 25 | 6.0 | 4.4–8.1 | * | * | * |

| Hispanic | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Other/Unknown | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Self-reported health status | ||||||

| Excellent | 41 | 9.8 | 7.4–12.7 | 36 | 12.9 | 10.0–16.5 |

| Very Good | 140 | 32.2 | 28.6–36.1 | 76 | 26.1 | 22.3–30.4 |

| Good | 149 | 33.5 | 29.7–37.4 | 88 | 32.9 | 28.3–37.9 |

| Fair | 94 | 19.3 | 16.7–22.1 | 60 | 18.6 | 15.4–22.3 |

| Poor | 25 | 5.3 | 3.8–7.3 | 26 | 9.4 | 7.0–12.5 |

| Health Conditions | ||||||

| Depression | ||||||

| No | 143 | 32.1 | 28.3–36.1 | 96 | 33.2 | 28.3–38.5 |

| Yes | 306 | 67.9 | 63.9–71.7 | 192 | 66.8 | 61.6–71.7 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 316 | 69.9 | 65.2–74.2 | 191 | 66.4 | 61.3–71.2 |

| Yes | 133 | 30.1 | 25.8–34.8 | 97 | 33.6 | 28.8–38.7 |

| Stroke | ||||||

| No | 377 | 86.0 | 83.7–88.1 | 243 | 83.4 | 79.5–86.7 |

| Yes | 72 | 14.0 | 11.9–16.3 | 45 | 16.6 | 13.3–20.5 |

| Number of psychoactive medications d | ||||||

| 0–8 (mean) | 460 | 1.32 | 1.21–1.43 | 294 | 1.25 | 1.10–1.39 |

Data not available due to small sample size

Bold = Chi-square test significant at p<0.05

n = unweighted number

% = weighted percent to the US Medicare population of characteristic

CI = 95% confidence interval

Included opioids, benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics (non-benzodiazepines limited to zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone), antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and other antidepressants (excluding SSRIs).

Approximately one in three older adults prescribed citalopram/escitalopram or sertraline reported any fall following medication exposure (citalopram/escitalopram: 36.3%, and sertraline: 39.4%). One in five older adults reported recurrent falls following medication exposure (citalopram/escitalopram: 21.4%, and sertraline: 22.3%) (Table 3). A greater percentage of older adults using sertraline at medium monthly TSDD (48.5%) and high monthly TSDD (40.3%), reported at least one fall in the year following medication exposure compared to those using citalopram/escitalopram at the same levels - medium TSDD (41.4%) and high TSDD (35.4%). Equivalent monthly doses are shown in Table 1. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Similar percentages of older adults using sertraline and citalopram/escitalopram reported two or more falls across the three average monthly TSDD levels.

Table 3:

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 by fall status – Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, 2010 −2017.

| Fall outcome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not report fall | Reported 1 or more falls | Reported 2 or more falls | |||||||

| Medication exposure | na | Weighted %b | 95% CIc | na | Weighted %b | 95% CIc | na | Weighted %b | 95% CIc |

| Citalopram/escitalopram | |||||||||

| Overall | 277 | 63.7 | 60.3–67.0 | 170 | 36.3 | 33.0–39.7 | 102 | 21.4 | 19.1–23.9 |

| Low TSDDd | 129 | 66.6 | 61.3–71.5 | 68 | 33.4 | 28.5–38.7 | 42 | 20.4 | 16.6–24.9 |

| Medium TSDDd | 72 | 58.6 | 50.7–66.0 | 53 | 41.4 | 34.0–49.3 | 28 | 20.6 | 15.9–26.4 |

| High TSDDd | 76 | 64.6 | 58.2–70.5 | 49 | 35.4 | 29.5–41.8 | 32 | 23.7 | 18.6–29.8 |

| Sertraline | |||||||||

| Overall | 172 | 60.6 | 55.7–65.4 | 112 | 39.4 | 34.6–44.3 | 66 | 22.3 | 18.7–26.3 |

| Low TSDDd | 75 | 66.3 | 59.4–72.6 | 47 | 33.7 | 27.4–40.7 | 33 | 23.3 | 18.4–29.0 |

| Medium TSDDd | 35 | 51.5 | 40.5–62.4 | 26 | 48.5 | 37.6–59.5 | * | * | * |

| High TSDDd | 62 | 59.7 | 51.6–67.3 | 39 | 40.3 | 32.7–48.4 | 20 | 20.2 | 14.1–28.0 |

Data not available due to small sample size

n = unweighted number

% = weighted percent to the US Medicare population of characteristic

CI = 95% confidence interval

TSDD = Average monthly total standardized daily dose categorized into low (60 or less), medium (60.1–90), and high (more than 90). For citalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤20 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >20 mg to 30 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >30 mg daily for 30 days. For escitalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤10 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >10 mg to 15 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >15 mg daily for 30 days. For Sertraline: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤50 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >50 mg to 75 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >75 mg daily for 30 days.

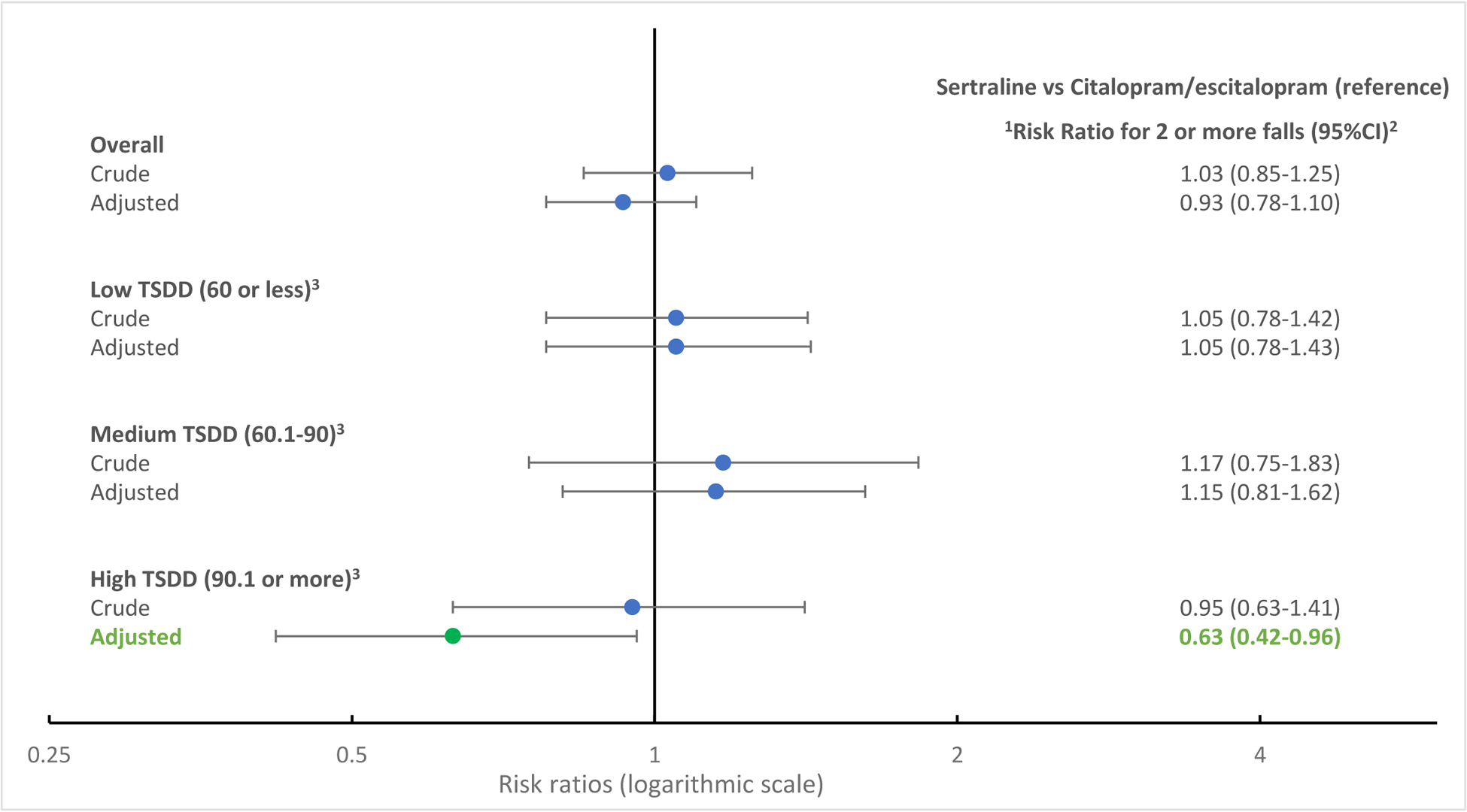

Table 4 shows the crude and adjusted risk ratios for reported falls in the year following medication exposure as any fall or recurrent falls comparing sertraline users to citalopram/escitalopram users across the average monthly TSDD categories. There were no statistically significant differences between sertraline and citalopram/escitalopram users across low or medium TSDD categories for any fall or recurrent falls. However, after adjusting for covariates, older adults prescribed high TSDD of sertraline (>75 mg daily for 30 days) had a lower risk of recurrent falls (two or more falls) compared to those prescribed high TSDD citalopram (>30 mg daily for 30 days) or escitalopram (>15 mg daily for 30 days) (adjusted RR=0.63, 95% CI 0.42–0.96) (Figure 1). Additionally, approximately 25% of citalopram users were on doses exceeding the maximum recommended dose of citalopram (equivalent to >20mg citalopram) during baseline years 2010, 2012, 2016 (Data not shown).

Table 4:

Crude and adjusted risk ratios of average monthly total standardized daily dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and falls – Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, 2010 −2017.

| Sertraline vs Citalopram/escitalopram (reference) | Reported 1 or more falls vs No falls (reference) | Reported 2 or more falls vs No falls (reference) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | RRb | 95% CIc | na | RRb | 95% CIc | |

| Overall | ||||||

| Crude | 723 | 1.08 | 0.93–1.26 | 609 | 1.03 | 0.85–1.25 |

| Adjustede | 700 | 1.01 | 0.88–1.15 | 592 | 0.93 | 0.78–1.10 |

| Low TSDD d | ||||||

| Crude | 314 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.27 | 274 | 1.05 | 0.78–1.42 |

| Adjustede | 303 | 1.04 | 0.82–1.33 | 266 | 1.05 | 0.78–1.43 |

| Medium TSDD d | ||||||

| Crude | 184 | 1.18 | 0.85–1.62 | 146 | 1.17 | 0.75–1.83 |

| Adjustede | 175 | 1.14 | 0.84–1.55 | 139 | 1.15 | 0.81–1.62 |

| High TSDD d | ||||||

| Crude | 225 | 1.16 | 0.90–1.49 | 189 | 0.95 | 0.63–1.41 |

| Adjustede | 222 | 0.87 | 0.67–1.13 | 187 | 0.63 | 0.42–0.96 |

n = sample size

RR = relative risk

95% CI = 95% confidence interval

TSDD = Average monthly total standardized daily dose categorized into low (60 or less), medium (60.1–90), and high (more than 90). For citalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤20 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >20 mg to 30 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >30 mg daily for 30 days. For escitalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤10 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >10 mg to 15 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >15 mg daily for 30 days. For Sertraline: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤50 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >50 mg to 75 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >75 mg daily for 30 days.

Adjusted for demographic characteristics (age, sex, race), and health characteristics (self-reported health status, fall history, health conditions limited to diabetes, depression, stroke), and concurrent psychoactive medication use as mean number of medications during medication exposure window.

Figure 1:

Crude and adjusted risk ratios of average monthly total standardized daily dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and recurrent falls – Medicare Current Beneficiary Surveys, 2010 −2017

1Risk ratios are adjusted for demographic characteristics (age, sex, race), and health characteristics (self-reported health status, fall history, health conditions limited to diabetes, depression, stroke), and concurrent psychoactive medication use as mean number of medications during medication exposure window.

2CI = 95% confidence interval

3TSDD = Average monthly total standardized daily dose categorized into low (60 or less), medium (60.1–90), and high (more than 90). For citalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤20 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >20 mg to 30 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >30 mg daily for 30 days. For escitalopram: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤10 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >10 mg to 15 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >15 mg daily for 30 days. For Sertraline: Low TSDD is equivalent to ≤50 mg daily for 30 days; Medium TSDD is equivalent to >50 mg to 75 mg daily for 30 days; High TSDD is equivalent to >75 mg daily for 30 days.

Discussion

Using a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries, we found that citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline are the most commonly used SSRIs. At least one-third of older adults using citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline reported any fall, and approximately one in five older adults reported recurrent falls. Our main finding was that there were no comparative differences in risk of falls between users at low or medium average monthly total standardized doses of sertraline vs. citalopram/escitalopram. However, users with a high average monthly dose of sertraline had a lower risk of recurrent falls compared to those with a high average monthly dose of citalopram/escitalopram users. Equivalent monthly doses are shown in Table 1. Additional research comparing safety profiles in relation to fall risk between individual antidepressants may better inform clinical decision making for antidepressant prescribing in older adults. Sufficient data are unlikely to be generated by clinical trials due to limitation in sample sizes and generalizability of results, so robust analyses using nationally representative data that include prescription drug use and dosage are important. Healthcare providers can assess their patient’s health status and current medication needs prior to initiating any changes.

Our findings around prevalence of medication use are consistent with previous studies. In a multinational cohort study estimating frequency of new antidepressant use in older adults, citalopram and sertraline were the most commonly used among the SSRIs (for the USA cohort, citalopram and sertraline were the most commonly prescribed antidepressants at 19.9% and 13.9% of patients, respectively).11 Moreover, risk of falls associated with antidepressant use, including SSRI, is well documented.7,21,22 In a longitudinal cohort study exploring antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes including falls in older adults, SSRI use was associated with the highest adjusted hazard ratio for falls (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.59–1.73) relative to other antidepressant subclasses when compared to no antidepressant use.21 Within the SSRI group, citalopram was associated with the highest adjusted hazard ratio for falls among the SSRIs.21

We found that a high dose of citalopram/escitalopram was associated with a higher risk of recurrent falls compared to high dose sertraline, however, this relationship was not observed at low or medium doses. Guidance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) restricts use of high dose citalopram (defined as over 20 mg daily) in adults over the age of 60 due to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms.23,24 These FDA restrictions were issued in 2012 during the time our second MCBS cohort was surveyed (2012–2013). While these restrictions were issued in 2012, a similar proportion of participants in our study used high dose citalopram (>20 mg/day) in 2016 compared to before and shortly after the FDA restrictions (2010 and 2012) which may suggest that these restrictions are not being implemented. High dose citalopram could be associated with abnormal heart rhythms, such as QT prolongation, which often result in dizziness, fainting spells, and an erratic heartbeat, all risk factors for falls. While citalopram has been implicated in QT interval prolongation on electrocardiogram (ECG),25 there is limited evidence linking it to adverse cardiac outcomes.23 However, falls and QT prolongation have shared risk factors including female sex, advancing age, and comorbidities such as stroke and diabetes.25 Therefore, disentangling causal pathways among antidepressant use, QT prolongation, and falls is challenging. In addition, doses of approximately 30 mg/day of citalopram have been associated with cognitive worsening in older adults with Alzheimer’s related agitation.26 Given our data, it is important to note that we were unable to determine potential underlying mechanisms for the differential risk in recurrent falls between high dose citalopram/escitalopram compared to sertraline.

While guidance from the 2019 update to the American Geriatrics Society Beer’s Criteria suggests avoiding use of SSRI in older adults with a history of falls or fracture,9 these medications are beneficial for certain patients.2,27 Depression in older adults is associated with cognitive impairment, functional decline, and decreased quality of life.2 If left untreated, depression can result in psychomotor deconditioning resulting in gait and balance abnormalities and increased risk of falls.22,28 Non-pharmacological treatment for depression such as cognitive behavioral therapy has comparable effectiveness to antidepressant therapy,2,29 however, treatment with antidepressant medications remains the mainstay in clinical practice,2 and SSRIs are commonly used as first-line treatment for depression in older adults.12

Older adult falls pose a significant burden to older adults, their caregivers, and healthcare systems. Every year, older adult falls result in more than three million emergency department visits and more than 950,000 hospitalizations.30 Common injuries from falls include traumatic brain injuries and hip fractures, often requiring specialized care and increasing the risk of placement in long-term care or nursing homes.31–33 Although common, falls can be prevented by targeting modifiable risk factors including strength and balance issues, and household hazards. Evidence-based clinical fall prevention interventions such as gait, strength, and balance exercises and home modifications exist and should be consistently offered to older adults who screen at risk for falls.34,35 This is especially important for older adults with depressive symptoms or those being prescribed antidepressant or other psychoactive medications.

Medication management and deprescribing is another fall prevention intervention which allows for routine evaluation of medication regimens for potential discontinuation or dose reductions.34 Discontinuation of psychoactive medications under supervision of a healthcare provider can reduce fall risk in older adults.36,37 Healthcare providers can assess their patient’s health status and current medication regimens, weighing risk and benefits of each medication and initiating deprescribing for non-essential or potentially inappropriate medications. Current research offers guidance on medication management tools in older adults, including but not limited to the Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions and Screening Tool to Alert Clinicians to Right treatment (STOPP/START) criteria that enable prescribers to avoid potentially inappropriate medications and help reduce polypharmacy in older adults.38 A newly developed screening tool, Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Older Adults with high fall risk (STOPPFall), may be used to identify medications with increased risk of falls in older adults with fall or fracture history.39 The STOPPFall tool highlights psychoactive medication classes, such as antidepressants, and provides deprescribing guidance for providers to assist with clinical decision making.39 Comparative safety research between individual medications within psychoactive classes, similar to our finding of a potential comparative benefit of sertraline vs citalopram/escitalopram at high doses, could help inform and improve these deprescribing tools. Future implementation studies might examine how best to utilize such tools in clinical practice.

There are limitations for our study. First, the data on functional and health characteristics and history of falls are self-reported which may result in recall bias for these fields especially for the outcome measure of falls. However, previous studies have estimated the prevalence of falls and fall injuries using comparable self-reported data collection.5 Self-reported falls in the previous 12 months have similar specificity as compared to more frequent fall assessments.40 Additionally, while medication use is ascertained by a panel survey interviewer verifying prescription bottles and payment receipts, actual medication ingestion cannot be ensured. Second, due to limitation in sample size, we were only able to examine select SSRIs, citalopram/escitalopram, and sertraline. While these are the most commonly used SSRIs, there are additional SSRIs and antidepressants from other sub-classes (e.g., SNRIs) that may contribute to fall risk. Third, while we controlled for common fall risk confounders such as demographic and health characteristics, the possibility of unmeasured confounding exists. To explore this, we calculated an E-value. The observed risk ratio for the association between high monthly dose of citalopram/escitalopram vs sertraline of 0.63 could be explained away by an unmeasured confounder that was associated with both the exposure and outcome with a risk ratio of 2.55.41–43 Additionally, the statistically significant risk ratio of 0.63 for high TSDD could have occurred as an artifact due to sparse data (n<50). The outcome events per variable (EPV) for this adjusted model is 5, therefore results should be cautiously interpreted with less than 10 EPV.44,45

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline are the most commonly used SSRIs by older Medicare beneficiaries. More than a third of older adults using citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline reported one or more falls, and approximately one in five older adults reported two or more falls in the year following medication exposure. Our analysis found a significant association of high average monthly total standardized dose of citalopram/escitalopram use with increased risk of recurrent falls compared to similar standardized doses of sertraline use. However, due to limitations of the dataset, results should be interpreted with caution. Information on the comparative safety of antidepressants in older adults is limited.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline are the most commonly used SSRIs among older Medicare beneficiaries.

There were no statistically significant differences in risk of falls between sertraline and citalopram/escitalopram at low or medium average monthly doses. Users of high average monthly dose citalopram/escitalopram had a higher risk of recurrent falls as compared to high dose sertraline users.

Why does this matter?

Our findings suggest a potential comparative safety benefit of sertraline as compared to citalopram/escitalopram, at higher cumulative doses, with regard to recurrent fall risk. Additional comparative studies of individual SSRIs may better inform antidepressant prescribing and fall risk.

Sponsor’s Role:

ZA Marcum was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K76AG059929). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

None of the authors have relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, or affiliations, or other potential conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003. Mar;58(3):249–65. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kok RM, Reynolds CF 3rd. Management of Depression in Older Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2017. May;317(20):2114–2122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5706.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birrer RB, Vemuri SP. Depression in later life: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Am Fam Physician. 2004. May;69(10):2375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iaboni A, Flint AJ. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: a clinical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013. May;21(5):484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergen G, Stevens MR, Kakara R, Burns ER. Understanding Modifiable and Unmodifiable Older Adult Fall Risk Factors to Create Effective Prevention Strategies. Am Journal of Lifestyle Med. October 2019. doi: 10.1177/1559827619880529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad YK, Luo F, Bergen G, Legha JK, Atherly A. Special Report from the CDC: Antidepressant subclass use and fall risk in community-dwelling older Americans. J Safety Res. 2021. Feb;76:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2020.11.008.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcum ZA, Perera S, Thorpe JM, Switzer GE, Castle NG, Strotmeyer ES, Simonsick EM, Ayonayon HN, Phillips CL, Rubin S, Zucker-Levin AR, Bauer DC, Shorr RI, Kang Y, Gray SL, Hanlon JT; Health ABC Study. Antidepressant Use and Recurrent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Findings From the Health ABC Study. Ann Pharmacother. 2016. Jul;50(7):525–33. doi: 10.1177/1060028016644466.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobieraj DM, Martinez BK, Hernandez AV, Coleman CI, Ross JS, Berg KM, Steffens DC, Baker WL. Adverse Effects of Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. Aug;67(8):1571–1581. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15966.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. Apr;67(4):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haddad YK, Luo F, Karani MV, Marcum ZA, Lee R. Psychoactive medication use among older community-dwelling Americans. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019 Sep-Oct;59(5):686–690. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2019.05.001.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamblyn R, Bates DW, Buckeridge DL, Dixon W, Forster AJ, Girard N, Haas J, Habib B, Kurteva S, Li J, Sheppard T. Multinational comparison of new antidepressant use in older adults: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019. May;9(5):e027663. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor WD. Clinical practice. Depression in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2014. Sep 25;371(13):1228–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1402180.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado M, Einarson TR. Comparison of SSRIs and SNRIs in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of head-to-head randomized clinical trials. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2010. Apr;35(2):177–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01050.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). [Online]. 2020. Data Documentation and Codebooks. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/Codebooks. [Accessed 03/2021].

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). [Online]. 2017. MCBS 2017 Data User Guide: General Information. Available from: URL: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/Codebooks.html. [Accessed 3/2021].

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). [Online]. 2010, 2012, 2016. Cost and Use / Methodology Report files. Available from: URL: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/Codebooks.html. [Accessed 03/2021].

- 17.Gray SL, Boudreau RM, Newman AB, Studenski SA, Shorr RI, Bauer DC, Simonsick EM, Hanlon JT; Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and statin use and incident mobility limitation in community-dwelling older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011. Dec;59(12):2226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03721.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R, Yu O, Crane PK, Larson EB. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015. Mar;175(3):401–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lexicomp Online [Internet]. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp Inc., 2021. Available from: http://online.lexi.com. [Accessed 03/2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganz DA, Latham NK. Prevention of Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2020. Feb 20;382(8):734–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1903252.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011. Aug;343:d4551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerse N, Flicker L, Pfaff JJ, Draper B, Lautenschlager NT, Sim M, Snowdon J, Almeida OP. Falls, depression and antidepressants in later life: a large primary care appraisal. PLoS One. 2008. Jun;3(6):e2423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002423.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarrell JL, Bailey TA, Duncan NA, Covington LP, Clifford KM, Hall RG, Blaszczyk AT. A review of citalopram dose restrictions in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders in older adults. Ment Health Clin. 2019. Jul;9(4):280–286. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2019.07.280.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration Drug Safety Communication: Revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses. 2011. Available from: URL:https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-revised-recommendations-celexa-citalopram-hydrobromide-related [Accessed 03/2021]

- 25.Rochester MP, Kane AM, Linnebur SA, Fixen DR. Evaluating the risk of QTc prolongation associated with antidepressant use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018. Jun;9(6):297–308. doi: 10.1177/2042098618772979.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, Marano C, Meinert CL, Mintzer JE, Munro CA, Pelton G, Rabins PV, Rosenberg PB, Schneider LS, Shade DM, Weintraub D, Yesavage J, Lyketsos CG; CitAD Research Group. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014. Feb 19;311(7):682–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.93.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kok RM, Nolen WA, Heeren TJ. Efficacy of treatment in older depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials with antidepressants. J Affect Disord. 2012. Dec 10;141(2–3):103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.036. Epub 2012 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010. Sep;21(5):658–68. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zivin K, Kales HC. Adherence to depression treatment in older adults: a narrative review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(7):559–71. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825070-00003.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [Online]. 2003. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). Available from: URL: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed [02/2021].

- 31.Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, Cook EA, Wright KB, Geweke JF, Chrischilles EA, Pavlik CE, Wallace RB, Ohsfeldt RL, Jones MP, Rosenthal GE, Wolinsky FD. The aftermath of hip fracture: discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2009. Nov;170(10):1290–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp266.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haddad YK, Shakya I, Moreland BL, Kakara R, Bergen G. Injury Diagnosis and Affected Body Part for Nonfatal Fall-Related Injuries in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Treated in Emergency Departments. J Aging Health. 2020. Dec;32(10):1433–1442. doi: 10.1177/0898264320932045.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson A, Xu L, Daugherty J, Breiding M Surveillance Report of Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths—United States, 2014. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/TBISurveillance-Report-508.pdf. Accessed [01/2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Lamb SE, Gates S, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. Apr;(2):CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007146.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, Hamid JS, Cogo E, Strifler L, Khan PA, Robson R, Sibley KM, MacDonald H, Riva JJ, Thavorn K, Wilson C, Holroyd-Leduc J, Kerr GD, Feldman F, Majumdar SR, Jaglal SB, Hui W, Straus SE. Comparisons of Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017. Nov;318(17):1687–1699. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15006.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999. Jul;47(7):850–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03843.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Negm A, Peters R, Wong EKC, Holbrook A. Deprescribing fall-risk increasing drugs (FRIDs) for the prevention of falls and fall-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021. Feb;11(2):e035978. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035978.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015. Mar;44(2):213–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. Erratum in: Age Ageing. 2018 May 1;47(3):489.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seppala LJ, Petrovic M, Ryg J, Bahat G, Topinkova E, Szczerbińska K, van der Cammen TJM, Hartikainen S, Ilhan B, Landi F, Morrissey Y, Mair A, Gutiérrez-Valencia M, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Mora MÁC, Denkinger M, Crome P, Jackson SHD, Correa-Pérez A, Knol W, Soulis G, Gudmundsson A, Ziere G, Wehling M, O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, van der Velde N. STOPPFall (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk): a Delphi study by the EuGMS Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs. Age Ageing. 2020. Dec 22:afaa249. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa249. Epub ahead of print.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganz DA, Higashi T, Rubenstein LZ. Monitoring falls in cohort studies of community-dwelling older people: effect of the recall interval. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005. Dec;53(12):2190–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D. Using the E-Value to Assess the Potential Effect of Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies. JAMA. 2019. Feb 12;321(6):602–603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21554.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathur MB, Ding P, Riddell CA, VanderWeele TJ. Web Site and R Package for Computing E-values. Epidemiology. 2018. Sep;29(5):e45–e47. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000864.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017. Aug 15;167(4):268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607. Epub 2017 Jul 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: a problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ. 2016. Apr 27;352:i1981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1981.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007. Mar 15;165(6):710–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. Epub 2006 Dec 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.