Abstract

In addition to their central functions in translation, ribosomes can adopt inactive structures that are fully assembled yet devoid of mRNA. We describe how the abundance of idle eukaryotic ribosomes is influenced by a broad range of biological conditions spanning viral infection, nutrient deprivation, and developmental cues. Vacant ribosomes may provide a means to exclude ribosomes from translation while also shielding them from degradation, and the variable identity of factors that occlude ribosomes may impart distinct functionality. We propose that regulated changes in the balance of idle and active ribosomes provides a means to fine-tune translation. We provide an overview of idle ribosomes, describe what is known regarding their function, and highlight questions that may clarify their biological roles.

Keywords: Idle ribosome, Vacant ribosome, Empty ribosome

Idle ribosomes

Life hinges on precise control of protein synthesis. At the core of this process is the ribosome. Ribosomes are revered as the catalysts of translation but are underappreciated as participants in translational control. The conditional formation of translationally silent ribosomes – fully assembled ribosomes devoid of mRNA – is widespread. While they were initially characterized in prokaryotes (referred to as hibernating ribosomes, see [1] for an in depth review), our understanding of their functions in eukaryotes remains tenuous [2–7]. Examining how they are controlled and what benefits they provide to cells is critical given the broad importance of translational regulation throughout biology and human disease.

Idle ribosomes are bound by an array of protein partners (Table 1), many of which prevent translation by occluding key regions of the ribosome. There is yet no universally accepted term encompassing these ribosomal species. They are commonly referred to as “hibernating,” “idle,” “vacant,” and “dormant.” For the purpose of this review, we use these terms interchangeably. Here, we first describe the eukaryotic ribosome and then discuss the current state of knowledge surrounding idle eukaryotic ribosomes and their associated inactivation factors, focusing on the most heavily studied complexes (for additional idle complexes see Box 1). We summarize their structures, examine what is known about their functions, and discuss regulatory pathways, specifically those related to nutrient stress (e.g. mTOR), that may influence their abundance. Finally, we highlight areas where further investigation is likely to yield insights into their biological roles.

Table 1:

Eukaryotic ribosome inactivating factors

| Name | Organism/s | Biological function | Ribosome binding site | Binding partners | PDB Structures | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stm1 | S. cerevisiae | Starvation recovery, translation restart | mRNA channel, LSU | eEF2 | 4V88 | [5] |

| SERBP1/VIG2/Habp4 | Human, mouse, rabbit, D. melanogaster (VIG2), Xenopus, zebrafish | mRNA binding, hormone signaling | mRNA channel, interacts with eEF2 domain IV; dependent on eEF2 | eEF2 | 7LS1, 7SL2, 7YOC, 6MTD, 6MTE, 4V6W, 4V6X | [2,3,6,33] |

| eEF2 | Human, mouse, rabbit, D. melanogaster, Xenopus, zebrafish | Ribosome translocation | A site, domain IV interacts with SERBP1; dependent on SERBP1; interacts with Habp4 in Xenopus and zebrafish | SERBP1, VIG2, Habp4 | 7LS1, 7SL2, 7OYC, 6MTD, 6MTE, 4V6W, 4V6X | [2,3,6,33] |

| Lso2 | S. cerevisiae, P. locustae | Starvation recovery, translation restart | mRNA channel, P site, GAC | none | 6Z6K, 6ZU5 | [4,33,46] |

| CCDC124 | Human | Cytokinesis | mRNA channel, P site, GAC | eRF1*/ABCE1* | 6Z6L, 6ZME | [33,46,52,108] |

| MDF1 | V. necatrix, E. cuniculi | Spore dormancy | E site | MDF2 | 6RM3, n/a** | [50,51] |

| MDF2 | V. necatrix | Spore dormancy | P site, Peptide exit tunnel | MDF1 | 6RM3 | [50] |

| Dap1b/Dapl1 | Xenopus, zebrafish | Epithelial differentiation | Peptide exit tunnel | eIF5A, Habp4, eEF2 | 7OYC | [7,109] |

| IFRD2 | Rabbit, human | Unknown | P site and mRNA exit channel | none | 6MTC | [3] |

| Nsp1 | SARS-CoV-2 | Repression of host translation | mRNA channel entry | TSR1*, CCDC124*, eRF1/ABCE 1*, LYAR*, eEF1* | 6ZM7, 6ZME, 6ZMI. 6ZMT | [52,60,62] |

Binding partners observed in an isolated instance.

PDB entries relating to E. cuniculi ribosomes bound to MDF1 are not yet available

Box 1: Poorly understood complexes.

Other forms of mammalian idle monosomes have also been observed. Brown et al. identified the protein IFRD2 as a ribosome inactivating factor in rabbit reticulocyte lysates [3]. It occupies the P site of the 80S ribosome, with a single α-helix inserted into the mRNA channel. A curious feature of this complex is a novel mode of tRNA binding to a region outside the E site dubbed the “Z” site. While the consequences of Z site tRNA are unclear, the interaction is reminiscent of certain viral internal ribosome entry sites, which can recruit ribosomes through cap-independent pathways.

In examining translational shutoff by SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1, another class of vacant 80S monosome was observed bound to LYAR [52]. The C-terminus of LYAR occupies a similar region of the 40S as the N-terminal portion of CCDC124, but no density was observed in the inter-subunit space or interacting with the LSU. It is therefore unclear how LYAR stabilizes vacant 80S ribosomes. LYAR is a nucleolar protein, suggesting it may play a role in ribosome biogenesis [106]. However, it interacts with cytoplasmic 80S ribosomes isolated from rat testes and cancer cells in which LYAR is highly expressed, though it does not associate with polysomes [107]. Thus, LYAR may bind to idle ribosomes in the absence of Nsp1. Excess recombinant LYAR also unexpectedly increased reporter translation in vitro. With little information about the functions of IFRD2 and LYAR, many questions remain about their role as ribosome silencing factors.

The translating ribosome

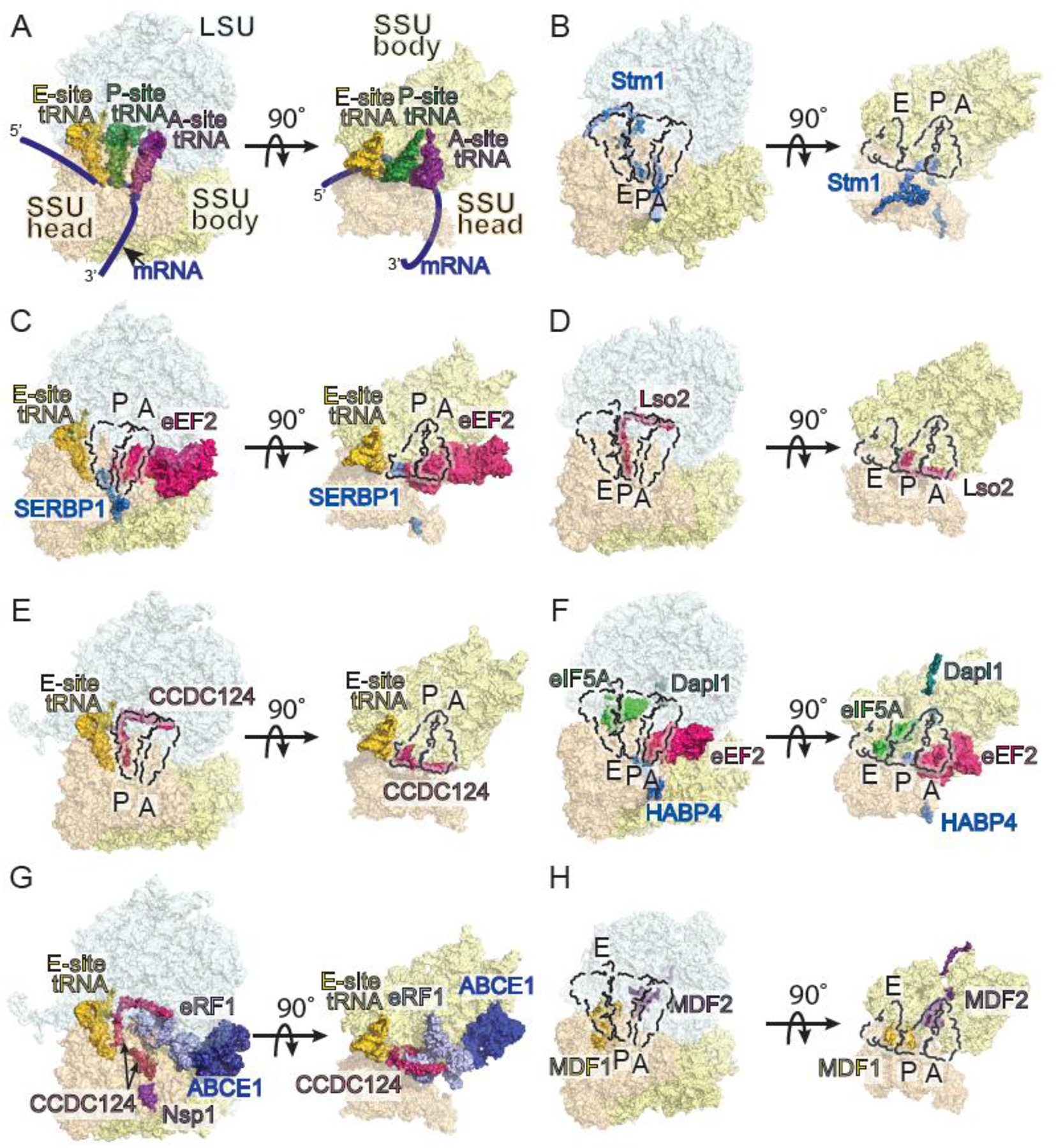

The ribosome is an enormous ribonucleoprotein complex comprised of two subunits. In eukaryotes, the large subunit (LSU, 60S) contains the site of protein synthesis, the peptidyl transferase center (PTC; see Glossary). The small subunit (SSU, 40S) possesses the mRNA decoding center. Both subunits contain tRNA binding regions designated the acceptor (A), peptidyl (P), and exit (E) sites (Fig. 1A). Collectively, they play fundamental roles in protein synthesis.

Figure 1 –

Overview of idle ribosomes. (A) Structural model of a eukaryotic 80S ribosome showing mRNA (blue) three tRNA sites: A (aminoacyl, purple), P (peptidyl transfer, forest), and E (exit, gold). The model was created by aligning two unpublished 80S ribosome structures from rabbit that contain A- and P-, and P- and E-site tRNAs, respectively. tRNA binding sites are indicated by dashed lines throughout. (B) Stm1 (marine)-bound 80S ribosome from S. cerevisiae (PDB 4V88). (C) SERBP1 (marine) and eEF2 (hot pink)-bound 80S ribosome from mouse (PDB 7LS1). (D) 80S ribosome from S. cerevisiae bound to Lso2 (warm pink, PDB 6Z6K). (E) Human 80S ribosome bound to CCDC124 (warm pink, PDB 6Z6L). (F) Xenopus 80S ribosome bound to HABP4 (marine), eEF2 (hot pink), Dapl1 (teal), and eIF5A(green). Domains of eEF2 are not present in the structure. (PDB 7OYC). (G) Human 80S ribosome bound to SARS-CoV Nsp1 (purple), CCDC124 (warm pink), eRF1 (light blue), and ABCE1 (dark blue). Note that the C-terminus of CCDC124 is visible in this model (PDB 6ZME). tRNA-binding sites are not shown for clarity. (H) Microsporidian (Vairimorpha nectarix) 80S ribosome bound to MDF1 (gold) and MDF2 (violet purple, PDB 6RM3).

Translation is divided into three separate phases: initiation, peptide-chain elongation, and termination. Initiation requires the ordered assembly of ribosomes on mRNA. The small subunit associates with several eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) to form the 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC), which can be delivered to a capped mRNA. The mRNA is loaded into the mRNA channel of the SSU – a prominent groove between the “head” and “body” domains of the subunit (Fig. 1A). The PIC then scans along the 5’ untranslated region (5’UTR) for the presence of a start codon [8–10]. Recognition of an appropriately situated start codon triggers recruitment of the 60S subunit. Departure of several initiation factors yields an 80S ribosome with the initiator peptidyl Met-tRNA in the P site and an empty A site.

During elongation, a region of the LSU known as the GTPase activation center (GAC) plays crucial roles in recruitment and activation of the GTPases, eukaryotic elongation factors 1 (eEF1) and 2 (eEF2). Aminoacyl-tRNAs are delivered to the A site by eEF1. Upon successful decoding of a cognate tRNA in the A site, the GAC promotes GTP hydrolysis by eEF1, triggering its departure [11–14]. The PTC then catalyzes transfer of the nascent peptide from the P site tRNA to the A site tRNA. Concurrently, the small and large subunits rotate with respect to one another (in a process termed inter-subunit rotation). The rotated state allows eEF2 to bind and catalyze translocation of the mRNA-tRNA module. Translocation is associated with swiveling of the 40S head domain [15–17]. Release of eEF2 is accompanied by back rotation of the subunits and return of the SSU head to its unswiveled position, leaving the previous A and P site tRNAs in the P and E site, respectively. This exposes the subsequent codon for decoding in the A site [18,19]. The elongation cycle continues until a stop codon is reached.

Termination is required to release the nascent polypeptide. Afterward, the two ribosomal subunits must be split so they may be recycled for additional rounds of translation (reviewed in depth in [20,21]). Termination is driven by eukaryotic release factors 1 (eRF1) and 3 (eRF3). When a stop codon is recognized by eRF1 it hydrolyzes the peptidyl-tRNA with the aid of eRF3. After release of the polypeptide, eRF3 dissociates and is replaced by ABCE1. ABCE1 catalyzes the dissociation of the 60S subunit from the 40S•mRNA•tRNA complex. The mRNA and tRNA are then displaced as a new 43S PIC is assembled. In contrast, idle ribosomes appear to be split by Pelo (Dom34 in yeast) and Hbs1, which are homologues of eRF1 and eRF3, respectively [22,23].

Cellular ribosome inactivation factors

SERBP1/Stm1p and eEF2

In mammals, the most abundant class of idle ribosomes contains Serpine1 mRNA binding protein (SERBP1) and eEF2 [3,24]. Similar ribosomal species exist in Drosophila, bound to eEF2 and the SERBP1 orthologue, VIG2 [2]. SERBP1 is a multifunctional RNA-binding protein linked to hormone signaling, micro RNA-mediated translational repression, and transcription [25–30]. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of SERBP1, Stm1p, is a translational repressor that enables translational restart following nutrient stress [31]. When bound to idle ribosomes, both Stm1p and SERBP1 occupy the mRNA channel from the entry tunnel through the A and P sites [2,3,5,6] (Fig. 1B, C). Stm1p promotes stable eEF2 binding, and truncations of Stm1p that impair eEF2 binding also prevent ribosome inactivation [32]. In mammals, SERBP1 has only been observed on idle ribosomes in the presence of eEF2 [2,3,6,33] (Fig. 1C). Thus, cooperative interactions between SERBP1/Stm1p and eEF2 appear to stabilize one form of inactive ribosomes.

Recent structural models have revealed unanticipated insights regarding the association of eEF2 [3,6]. During elongation, peptide transfer promotes inter-subunit rotation. The rotated state enables association of eEF2 bound to GTP. eEF2 catalyzes translocation followed by GTP hydrolysis. This interaction is normally transient [19]. Hydrolysis of GTP, as well as the conformation of the post-translocation ribosome, are thought to favor eEF2 dissociation [16]. SERBP1-eEF2-bound idle ribosomes exist in both rotated and non-rotated conformations, each with eEF2 in the GDP-bound state [3,6]. The latter would ordinarily favor departure of eEF2 from active ribosomes. The presence of GDP-bound eEF2 suggests either association with idle ribosomes does not affect GTP hydrolysis, or that SERBP1 stabilizes eEF2 in the GDP-bound state. Resolving this point is important for understanding how eEF2 remains stably associated with inactive ribosomes.

What governs the stabilization of inactive ribosomes by eEF2 and SERBP1? eEF2 associates with translating ribosomes to promote translocation. SERBP1 is also present on translating polysomes and individual 40S subunits where it binds to the solvent-exposed face of the 40S subunit [34]. This non-repressive association suggests SERBP1 may have additional translation-associated functions beyond ribosome inactivation. What triggers eEF2 and SERBP1 to stabilize inactive ribosomes? Post-translational modification sites in SERBP1 suggest a potential regulatory modality. Multiple arginine residues of SERBP1 are subject to methylation by protein arginine methyltransferase 1, which controls its localization to the cytoplasm [35]. During mitosis, phosphorylation by PKCε drives the localization of SERBP1 to cytoplasmic foci and slightly alters its binding site on the ribosome [36]. If this specific event affects translation or idle ribosome formation is unclear. SERBP1 contains several other putative post-translational modification sites with unknown functions [37–41]. Some of these sites are similar to motifs targeted by kinases such as GSK3, CK1, PKA, and CaMK2 [42,43]. These kinases participate in a broad array of cellular functions including stress responses, cell cycle, and synaptic plasticity. Additionally, eEF2 is negatively regulated by phosphorylation at a single site (discussed in detail below). It is also subject to other post-translational modifications, the effects of which are less clear [44,45]. An important question moving forward is how signaling events trigger the formation of idle ribosomes and what role post-translational modifications play in this process.

CCDC124/Lso2p

Coiled-Coil Domain Containing 124 (CCDC124) defines a distinct population of idle ribosomes in human cells [33]. The yeast homolog, Lso2p, aids in translational restart during recovery from nutrient stress [46]. Hints that Lso2p is a ribosome-binding factor emerged from the observation that it physically associates with the 60S subunit [46]. Structures have since emerged from yeast, microsporidian, and human cells that reveal almost identical binding modes of CCDC124 and Lso2p to vacant 80S monosomes [4,33] (Fig. 1D–E). Both possess two α-helices connected by a short hinge region. The N-terminal end resides in the mRNA channel near the P site. The first helix then extends into the inter-subunit space and towards the LSU, occluding the P site. The hinge makes contacts with rRNA near the PTC. The second helix extends along the inter-subunit face of the LSU from the PTC through the A site where it interacts with the GAC (the region C-terminal to this helix could not be resolved). Thus, like the SERBP1/Stm1p-eEF2 complex, CCDC124/Lso2p blocks P and A site tRNA binding as well as the mRNA channel and the GAC. CCDC124/Lso2p monosomes do not require an additional binding partner and are found exclusively on idle ribosomes in the non-rotated state. Neither is detected on polysomes, which suggests they do not interact with translating ribosomes [46]. Their association appears to be purely inhibitory. A key question moving forward is understanding what controls the assembly of CCDC124/Lso2p-bound idle ribosomes.

How are idle ribosomes disassembled? A likely fate of idle ribosomes is re-entry into the translation cycle. The recycling of starvation-induced idle ribosomes by Dom 34-Hbs1 is necessary for the resumption of translation in yeast [23]. In vitro comparisons of Stm1p- and Lso2p-inactivated ribosomes revealed that Lso2p complexes are efficiently recycled, while Stm1p ribosomes are resistant to splitting [33]. This difference likely holds true in mammals, as eEF2 occupies the binding site of Pelo-Hbs1 [6]. Ribosomes inactivated by CCDC124 lack an analogous steric hindrance [33]. Does this difference matter in cells? Upon nutrient restoration following starvation, translation resumes. Loss of either Stm1p or Lso2p impairs recovery of translation [31,46,47]. Direct comparisons of Stm1p and Lso2p are lacking in this context. Yet, differences in stability and failure to fully compensate for one another during stress recovery suggests that the two pathways are not functionally equivalent.

MDF1/MDF2

Genome reduction is a characteristic feature of obligate intracellular parasites, often resulting in the loss of metabolic and biosynthetic pathways [48,49]. making regulation of the central dogma crucial during certain stages of the parasite’s life cycle. Examinations of intracellular parasites in the phylum Microsporidia have revealed the presence of dormant ribosomes bound to microsporidian dormancy factors 1 and 2 (MDF1 and MDF2). In Vairimorpha necatrix, MDF1 appears to mimic a tRNA and occupies the E site, while MDF2 resides in the P site where it occludes the peptide exit tunnel and PTC [50] (Figure 1H). Similar ribosome inactivation strategies may be conserved across Microsporidia – structures from dormant Encephalitozoon cuniculi spores also reveal idle ribosomes bound to MDF1 [51], though it is unclear if MDF1 alone is sufficient to trigger their formation. Curiously, ribosomes isolated from spores of another microsporidian parasite, Paranosema locustae, were in an inactive state bound to Lso2 [4]. These findings implicate the formation of idle ribosomes as a potentially integral part of the life cycle of microsporidian parasites, aiding in the maintenance of dormancy when spores are outside the environment of a host cell.

Although the human MDF1 homologue shows conservation of the microsporidian MDF1 structure, it is unclear if it, too, plays a role in ribosome inactivation [50]. Homologues of MDF2 have thus far only been identified in other microsporidia. Genome reduction has altered the structure and components of microsporidian ribosomes, resulting in loss of expansion segments and alterations of ribosomal protein structures, though the key functional regions of the ribosome remain intact. It remains to be seen if MDF1 homologues play a role in ribosome silencing in “higher” eukaryotes.

Dap/Dapl1/Dap1b and eIF5A

Idle ribosomes are prominent in early developmental stages in both zebrafish and Xenopus oocytes [7]. Up to roughly 6 hours post-fertilization, zygotic translation is low and most maternal ribosomes are in a dormant state. Many are bound to eEF2 and the SERBP1 paralogue Habp4, in a manner similar to SERBP1-eEF2 complexes. Some Hapb4-eEF2 ribosomes in eggs and 1 hour post-fertilization embryos exhibit a novel addition – eIF5A between the E and P sites, and Dap or Dap1b (Dapl1 in Xenopus) in the peptide exit tunnel (Fig. 1F). Although all four factors appear to bind simultaneously, knockout experiments show the two pairs may serve distinct functions. Loss of Hapb4 resulted in a depletion of monosomes with no change to polysome fractions. Dap/Dap1b knockout yielded no change to the monosome fraction, but increased polyribosome formation. The authors propose that Dap1b attenuates translation while Hapb4 is responsible for vacant ribosome stabilization. This work underscores the tremendous value of structural analyses in a broad range of biological contexts as a means of uncovering new insights. As structural views into ribosomes in a broad range of tissues and organisms emerge, it is likely that our appreciation of the structural and functional diversity will similarly increase.

E site tRN

A ubiquitous feature of idle ribosomes is the presence of E site tRNAs [2,6,33,52]. In both CCDC124 and SERBP1-eEF2 complexes, density is present for tRNA in the E-site. The latter is intriguing given that eEF2 promotes tRNA release from the E-site on active ribosomes [53]. A tRNA normally reaches the E site via the P site during translocation, necessitating a codon-anticoding interaction. How a tRNA arrives at the E site of a ribosome lacking mRNA is unclear. The lack of bias towards any particular tRNA species may indicate this is the result of non-specific binding. If this is an artifact, it is highly consistent as they are present in samples prepared using different approaches. Alternatively, E site tRNA may be evidence of idle ribosomes forming mid-elongation. Additional experiments are required to probe the functional significance of E site tRNAs on idle ribosomes.

Viral ribosome inactivation factors

Viruses are obligate parasites dependent on their host cell for replication. While viruses often encode polymerases, and some even harbor translation factors and tRNAs, they universally lack ribosomes [54,55]. In order to co-opt the translational machinery and evade the immune system, viruses often poison host translation through a variety of mechanisms [56]. Betacoronaviruses employ the conserved non-structural protein 1 (Nsp1) to limit interferon signaling by blocking translation [57–60]. Recent investigations of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Nsp1 revealed this is accomplished through competitive binding to the mRNA channel [61]. The C-terminal domain of Nsp1 forms a pair of short α-helices that insert into the mRNA entry channel of the 40S, blocking mRNA recruitment [52,62]. Nsp1 induces a variety of inactive complexes. It is present on 43S PICs as well as 40S subunits bound to a ribosome biogenesis factor, 20S rRNA accumulation 1 (TSR1) [52]. TSR1 contributes to late stages of 40S maturation in the cytoplasm where it aids in preventing precocious recruitment of mRNA to the immature SSU [63–65]. Thus, Nsp1 may block 43S PIC recruitment as well as addition of new 40S subunits to the translating pool.

Nsp1 also binds vacant 80S ribosomes [52] Notably, two configurations containing Nsp1 and CCDC124 have been observed. In both, CCDC124 is bound as previously described [33]. However, the C-terminal region of CCDC124 was resolved. From the GAC, it extends back across the inter-subunit space, where it interacts with the mRNA channel near the A site. One complex simply contained CCDC124 and Nsp1 [52]. In the other, two recycling factors – eRF1 and ABCE1 – were observed (Fig. 1G). eRF1 adopts an unusual conformation in this complex. The N-domain of eRF1, which is responsible for stop codon recognition, is displaced by CCDC124 and rotated nearly 180° from its normal position [52,66,67]. The functional significance of this conformation is unclear. In vitro, mammalian idle ribosomes are recycled by the Pelo-Hbs1 complex, but fail to be split by eRF1-eRF3 [22]. The ability to resolve a sizeable pool of eRF1-ABCE1-bound idle ribosomes suggests that subunit splitting via the canonical recycling pathway might be impaired. Additional experiments are needed to investigate how Nsp1 affects recycling and how this ultimately impacts protein synthesis.

While the coronavirus Nsp1 is the only example (to our knowledge) of a viral factor inducing idle ribosomes, this is unlikely to be the only instance of viruses exploiting these complexes. It was recently found that mimicking the phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein, RACK1, by a vaccinia virus kinase leads to a depletion of polysomes and enhances eEF2 and SERBP1 binding to 80S monosomes [68]. Though it remains unclear if idle ribosomes are induced by vaccinia infection, the inactivation of ribosomes by either host or viral factors may be a broadly conserved strategy among viruses.

Regulation

How is the formation of idle ribosomes controlled? Important clues may reside in upstream pathways triggered by nutrient stress. Translation accounts for the plurality of energy consumption in mammalian cells [69]. Thus, its regulation in response to nutrient availability is vital. Starvation induces translational blockade through multiple factors triggered by conserved signaling pathways linked to nutrient sensing. We discuss potential implications on idle ribosomes.

mTOR

Due to the expense of their synthesis, ribosome biogenesis is tightly controlled during nutrient stress [70,71]. In yeast, starvation also leads to translational shutoff and is accompanied by a drastic accumulation of monosomes and concurrent depletion of polysomes [23,72]. Stm1p and Lso2p are critical to recovery from nutrient stress. They aid in the restart of translation after starvation-induced translational shutoff [31,46,47,73]. Loss of either has no effect on unstressed cells, but impairs growth following nutrient restriction [46,47]. These observations suggest that ribosome inactivation confers fitness advantages.

AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR; TOR in yeast) are critical sensors of nutrient availability. They govern translation in distinct ways. In non-starved conditions, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) enhances translation by inhibiting the translational repressors eIF4E binding proteins 1 and 2 (4E-BPs) and by activating p70 RPS6 kinase (RPS6K1) [74–76]. During nutrient restriction, AMPK suppresses mTOR activity [77,78]. As major links between nutrient sensing and translational control, these pathways are likely integral to the formation of idle ribosomes. Loss of the stm1 gene sensitizes yeast to the TOR inhibitor rapamycin, resulting in defective growth and reduced translation [31]. This implicates Stm1p as part of the TOR pathway, though the exact mechanism remains unclear.

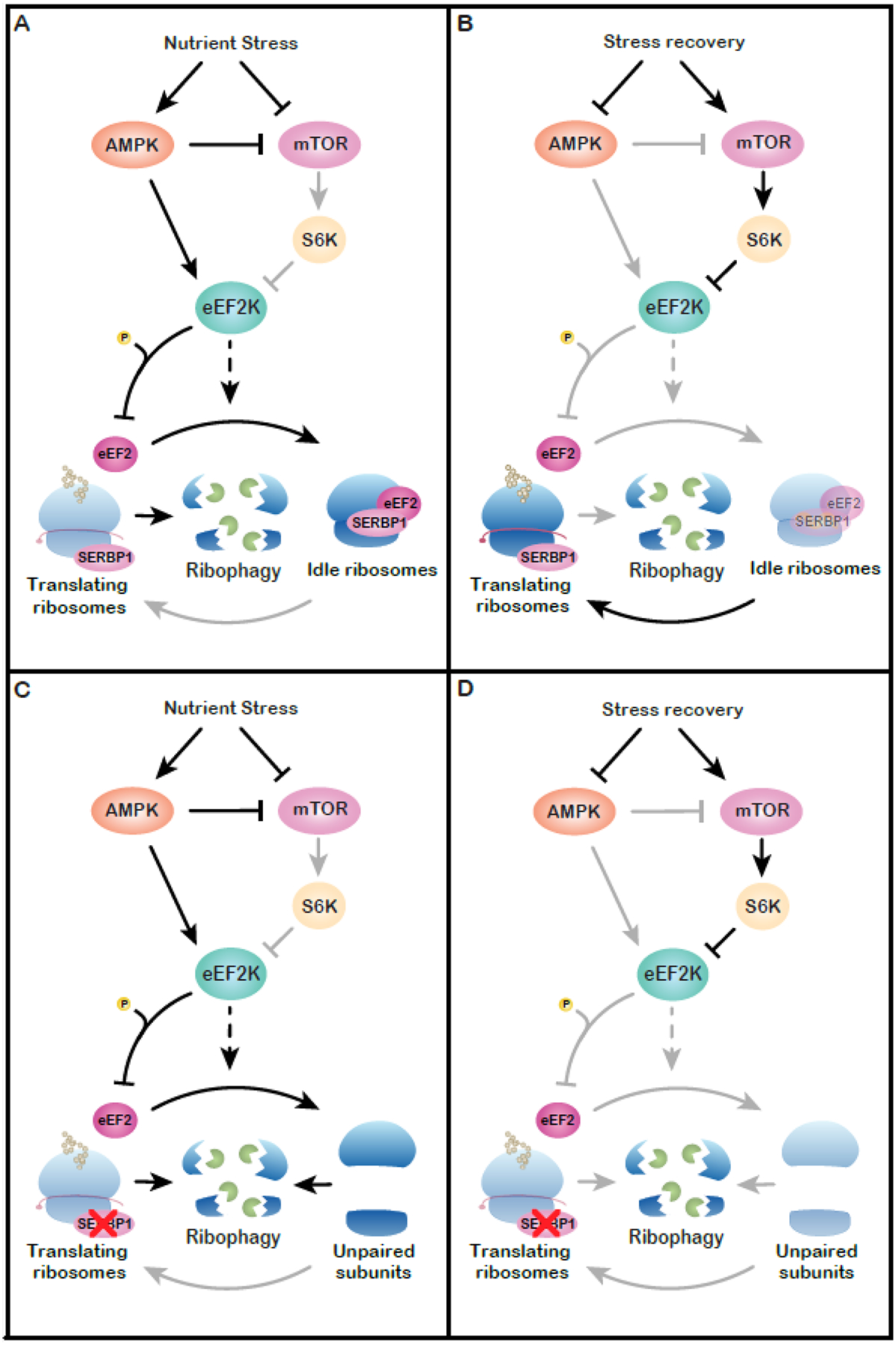

In addition to attenuating translation, mTOR inhibition enhances lysosomal degradation of ribosomal subunits through a process known as ribophagy [79]. Stm1p preserves the stability of ribosomes during nutrient stress in yeast [47]. We propose that, in addition to attenuating translation initiation and promoting ribophagy, mTOR inhibition might enhance formation of idle ribosomes (Fig. 2A, B). This would generate a pool of ribosomes shielded from elimination. Re-engagement when nutrients are once again plentiful would enable rapid adaptation. Loss of silencing factors would result in excessive ribosome degradation, impairing translational homeostasis and likely resulting in detrimental effects on cell growth (Fig. 2 C,D) [46,47].

Figure 2 –

Proposed model for regulation of idle ribosomes. (A) Nutrient stress triggers mTOR inhibition and AMPK activation. Both events lead to activation of eEF2K, which may play a role in regulating the assembly of idle ribosomes. Nutrient stress also triggers ribophagy. The formation of idle ribosomes prevents excess turnover by creating a pool of ribosomes protected from degradation. (B) During recovery from nutrient deprivation, ribophagy is inhibited and idle ribosomes re-enter the translating pool, enabling a resumption of protein synthesis. (C) Loss of a ribosome-silencing factor (e.g. SERBP1) impairs the formation of idle ribosomes, leading to excess ribophagy during nutrient stress. (D) In this case, translational recovery is impaired due to the failure to preserve ribosomes.

If mTOR signaling regulates idle ribosome abundance, this suggests additional biological contexts where their control may be critical. mTORC1 acts as a translational regulator across a range of contexts beyond nutrient homeostasis, such as stem cell fate, pain, and brain development [80–82]. One area primed for investigation is immunity. Translational regulation is critical to multiple facets of immune signaling [83]. Activation of CD4+ T cells instigates a massive increase in translation, largely driven by mTOR. Naïve T cells harbor a pool of non-translating ribosomes that are engaged following T cell activation to rapidly boost translational capacity [84]. T cell receptor stimulation induces mTOR and leads to SERBP1 phosphorylation [85,86]. Further investigation is needed to determine the state of inactive ribosomes in naïve T cells and if SERBP1 phosphorylation is relevant to their reactivation.

eEF2K

Both the mTOR and AMPK pathways converge on a critical regulator of the elongation phase of translation – eEF2 kinase (eEF2K). eEF2K attenuates elongation by phosphorylation of its sole known target, eEF2. Phosphorylated eEF2 does not bind actively translating ribosomes [87]. mTOR inhibits eEF2K activity via RPS6K1 [88,89]. AMPK activates eEF2K by two mechanisms. In the first, it acts indirectly by inhibiting mTOR [77,78]. In the second, it directly enhances eEF2K activity by multi-site phosphorylation [90]. Loss of eEF2K in mammalian cells and C. elegans impairs adaptation to nutrient deprivation [91]. Thus, eEF2K is integral to the nutrient stress response.

In mouse sensory neurons, excess eEF2K activity results in the accumulation of vacant monosomes bound to SERBP1 and eEF2 [6]. This effect was prevented by an eEF2K inhibitor. Curiously, these monosomes are capable of binding phosphorylated eEF2. 80S monosomes formed upon activation of eEF2K were resistant to splitting. Thus, eEF2K may be involved in the formation and/or stabilization of eEF2-SERBP1-inactivated monosomes (Fig. 2). This finding reveals a possible mechanism of vacant ribosome control and suggests possible biological contexts where controlling ribosome availability is critical. In addition to stress responses, eEF2K plays a crucial role in neurons where it is involved in synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis [92–94]. Additional work is needed to clarify if the contribution of eEF2K to neuronal activity is due to the control of idle ribosomes or effects on translation elongation stemming from inactivation of eEF2.

Potential functions

Despite tremendous advances in the identification of vacant ribosomes, key questions remain surrounding their physiological roles. In the following section, we provide ideas meant to stimulate discussion and experiments intended to help the field progress.

Maintenance of subunit stoichiometry

The stoichiometry of ribosomal components is tightly regulated. Changes in the balance of small and large subunits could compromise the translational landscape of the cell. Subunit stoichiometry is managed in part at the transcriptional level – all but one of the rRNAs are part of the same primary transcript and are therefore transcribed in 1:1:1 ratios [95]. Because the early phases of subunit assembly occur co-transcriptionally, ribosome biogenesis begins as a stoichiometrically balanced process. The ratio of ribosomal proteins to ribosomes is managed through the degradation of excess ribosomal proteins [96]. Perturbing the successful biogenesis of one subunit induces turnover of the other [97]. This suggests cells can also maintain their LSU:SSU ratio through degradation of excess subunits. Additionally, free subunits may be less stable than paired ones.

How do cells assess subunit stoichiometry? While the underlying mechanisms are unclear, an intriguing possibility involves vacant ribosomes. If unpaired subunits are subject to turnover, then the transient formation of vacant monosomes post-termination could serve as a de facto stoichiometry measure simply by preventing the action of degradation factors. While this idea is purely speculative, it is supported by the fact that idle ribosomes in E. coli and S. cerevisiae are protected from degradation by silencing factors [47,98]. Additional work is needed to determine if idle ribosome are indeed protected from ribophagy in mammals and to what extent the different idle complexes are involved. The recent identification of the mammalian ribosome receptor for autophagy will allow for selective perturbation of ribosome turnover, enabling controlled investigations into the question of subunit stoichiometry [99].

Control of subunit availability

Pathological mutations in ribosome components are collectively known as ribosomopathies. One proposal to explain the unexpectedly tissue-specific phenotypes of some ribosomopathies is known as the ribosome concentration hypothesis (reviewed in [100]). Simplified models of translation suggest that altering the concentration of ribosomes does not affect translation uniformly across the transcriptome. Rather, it is predicted that changes to the pool of available ribosomes affect an mRNA’s translation as a function of the initiation efficiency of the transcript. For example, constricting the number of available ribosomes will impede translation of poor initiators, while it may enhance translation of very rapidly initiating mRNAs due to the alleviation of ribosome collisions. Although the models underlying this hypothesis have been around for decades, experimental evidence is only beginning to emerge [101].

How do changes in ribosome concentration influence translation of mRNA? Reduction of 40S subunits preferentially attenuates translation from the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) compared to cellular transcripts [102]. This is consistent with the ribosome concentration hypothesis as IRES-driven initiation is substantially less efficient than cap-dependent initiation [103]. Recently, independent studies in yeast and human hematopoietic stem cells found that changes to ribosome abundance indeed have non-uniform effects on translation efficiency. In yeast, restricting subunits through knockout of ribosomal proteins resulted in altered translation efficiency of subsets of the transcriptome [104]. Transcripts showing increased translation tended to have long ORFs, while those whose translation was reduced showed a slight trend towards shorter ORFs. Modeling ribosome-depleting mutations associated with Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Khajuria et al. observed reduced translation efficiency of a subset of 525 transcripts [105]. These mRNAs tended towards shorter ORFs and 5’UTRs, fewer upstream open reading frames, and were enriched for several 5’UTR motifs. The ribosome concentration hypothesis does not account for important parameters such as relative abundance of mRNAs, elongation rates, or trans-acting factors. Therefore, changes in ribosome concentration will likely yield different outcomes depending on the cell type and biological context. Extrapolating beyond ribosomopathies, could this be employed as a mode of translational regulation? If so, the assembly and disassembly of vacant ribosomes could be a means to functionally alter ribosome concentration by controlling the number of ribosomes available for translation. Though the effect of idle ribosome formation on translation has yet to be investigated via this approach, ribosome profiling may provide critical insights into this question.

Concluding remarks

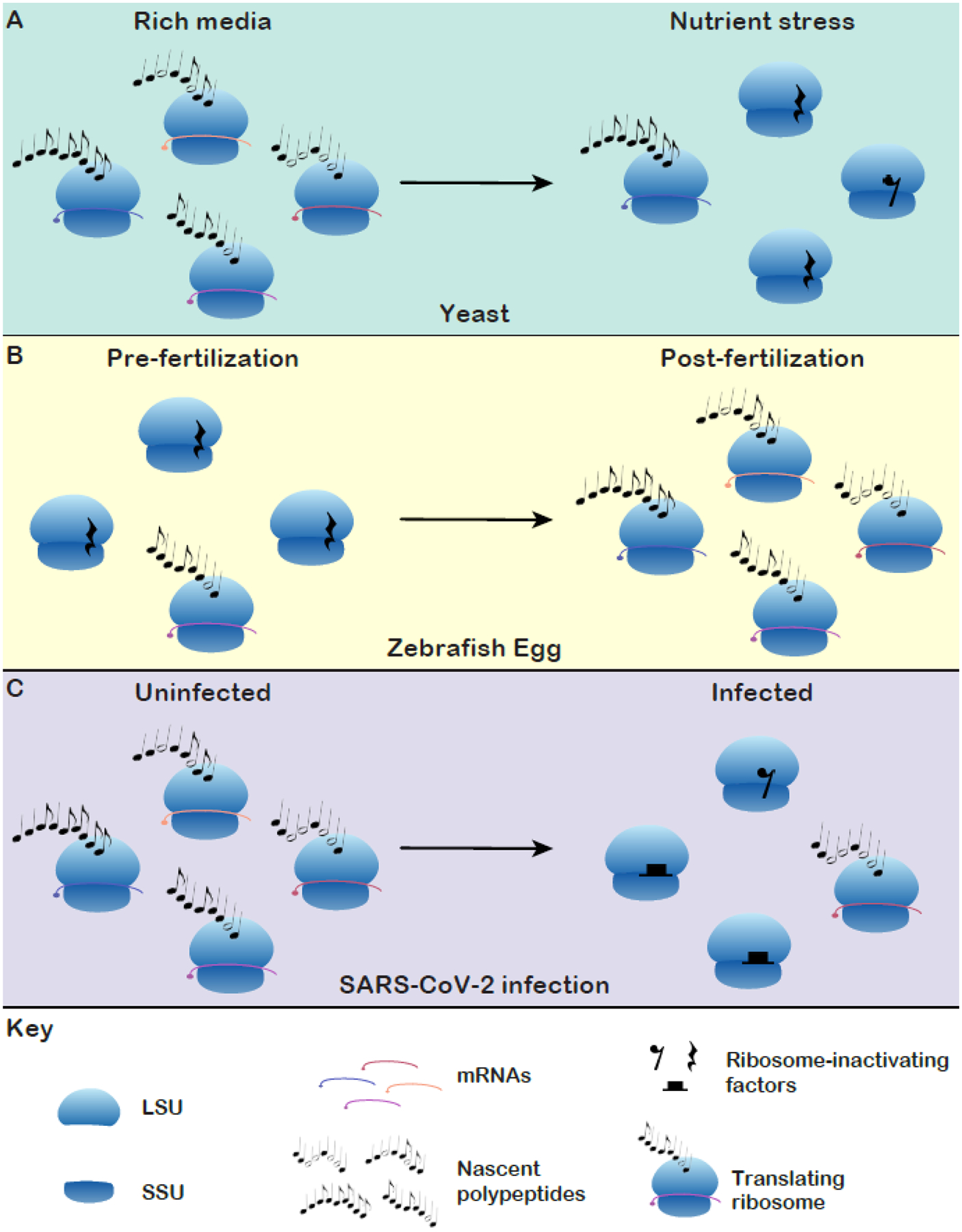

The composer Claude Debussy is credited with the expression that music is the spacing between notes. Just as spacing and silence enables beauty to emerge in music, the balance between active and translationally silent ribosomes is likely important for translational homeostasis. Indeed, this appears to be the case in yeast during nutrient stress, early post-fertilization zebrafish and Xenopus eggs, and in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells [7,31,46,47,52,62] (Figure 3, Key figure). Despite the widespread occurrence of idle ribosomes, there is a vast amount that remains to be determined about their regulation, functions, and biological roles. Ultimately, the identity of the proteins that stabilize idle ribosomes must dictate their functions. The properties of each idle species (e.g. stability, conditions where they are formed, distribution in cells etc.) must be elucidated (see Outstanding Questions) to clarify their biological functions.

Figure 3, Key Figure –

A representation of the regulation of silent ribosomes in different biological paradigms. To date, the orchestration of idle ribosomes has been shown to influence translation in three biological contexts. (A) In yeast, ribosome silencing factors preserve ribosomes during nutrient stress and enable efficient translational restart [31,46,47]. (B) Ribosomes are maintained in idle states in the pre-fertilization eggs of zebrafish and Xenopus. Idle ribosomes cease to be maintained as translation increases several hours post-fertilization [7]. (C) SARS-CoV-2 poisons host cell translation by inducing a range of idle ribosome complexes with a viral protein [52,62].

Outstanding questions box.

How are idle ribosomes assembled and how efficiently are they recycled? How variable are splitting efficiencies for different types of idle ribosome?

What are the physiologic functions of idle ribosomes? How does their loss impact adaptation and recovery from stress?

How dynamic is their assembly and recycling? What is the variation and polarity of each population within the cell? Is transport of ribosomes accomplished using idle ribosomes?

What transcripts are affected by ribosome sequestration? How is the landscape of translation altered by the presence of idle ribosomes? Does decreased ribosome availability result in increased reliance on cap-independent translation?

Highlights.

Idle, or vacant, ribosomes are broadly conserved, from prokaryotes to eukaryotes

Starvation, stress, development, and viral infection can influence the formation and elimination of vacant eukaryotic ribosomes

Recent structures reveal numerous protein factors that occlude functional sites on the ribosome, rendering them inactive

Idle ribosomes may represent means to regulate ribosome stoichiometry and subunit availability, amongst other yet-to-be determined functions potentially linked to nutrient sensing

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. David Haselbach and Andrea Pauli for providing their structure model ahead of publication. This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS100788 (ZTC) and R01NS114018 (ZTC).

Glossary

- 43S Pre-initiation complex (PIC)

The complex formed by a 40S subunit, eIF1, eIF1A, and eIF3. Association of these factors is necessary to accommodate a eukaryotic transcript in the mRNA channel. Subsequent association of the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAiMet ternary complex completes the 43S PIC

- 4E-BPs

Inhibit cap-dependent initiation by binding eIF4E and preventing it’s interaction with the m7G cap

- 5’ untranslated region (UTR)

The region of a eukaryotic mRNA upstream (5’) of the start codon

- Expansion segments

Insertions in poorly conserved regions of rRNA that have increased in size with the evolution of complex eukaryotes

- GTPase activating center (GAC)

A region of the LSU consisting of a portion of the 28S rRNA and several ribosomal proteins that form the P- stalk. This domain aids in recruitment and activation of translational GTPases

- Internal ribosome entry site

Common elements of RNA virus genomes that allow for cap-independent translation through a range of initiation factor and ribosome recruitment mechanisms mediated by complex RNA secondary structures. IRES elements also exist in cellular some mRNAs, though their mechanisms of initiation remain opaque

- P70 RPS6 kinase (RPS6K1)

Kinase downstream of mTOR that aids in the enhancing translation by targeting eEF2K, eIF4B, and eIF4A (indirectly). RPS6K1also phosphorylates the ribosomal protein S6, though the effects of this phosphorylation event are unclear

- Peptidyl transferase center (PTC)

A portion of the 28S rRNA (23S or 25S in prokaryotes and yeast, respectively) that acts as a ribozyme, catalyzing the condensation reaction between the C-terminus of the nascent polypeptide and the amino group of the incoming amino acid

- Peptide exit tunnel

The tunnel-like domain of the LSU from which the growing peptide is extruded

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

Member of the betacoronaviruses, the group that includes Middle-East respiratory syndrome virus (MERS-CoV) and all severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) related coronaviruses. SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Citations

- 1.Prossliner T et al. (2018) Ribosome Hibernation. Annu. Rev. Genet 52, 321–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anger AM et al. (2013) Structures of the human and Drosophila 80S ribosome. Nature 497, 80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown A et al. (2018) Structures of translationally inactive mammalian ribosomes. Elife 7, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenbolger K et al. (2020) Differences in structure and hibernation mechanism highlight diversification of the microsporidian ribosome. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Shem A et al. (2011) The Structure of the Eukaryotic Ribosome at 3.0 Å Resolution. Science (80-.) 334, 1524 LP–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PR et al. (2021) Functionally distinct roles for eEF2K in the control of ribosome availability and p-body abundance. Nat. Commun 12, 6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leesch F et al. (2021) A molecular network of conserved factors keeps ribosomes dormant in the egg. BioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinnebusch AG (2014) The scanning mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu. Rev. Biochem 83, 779–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinnebusch AG et al. (2016) Translational control by 5’-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science 352, 1413–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreev DE et al. (2017) Insights into the mechanisms of eukaryotic translation gained with ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 513–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voorhees RM et al. (2010) The mechanism for activation of GTP hydrolysis on the ribosome. Science 330, 835–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maracci C and Rodnina MV (2016) Review: Translational GTPases. Biopolymers 105, 463–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polacek N and Mankin AS (2005) The ribosomal peptidyl transferase center: structure, function, evolution, inhibition. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 40, 285–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voorhees RM et al. (2009) Insights into substrate stabilization from snapshots of the peptidyl transferase center of the intact 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 528–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratje AH et al. (2010) Head swivel on the ribosome facilitates translocation by means of intra-subunit tRNA hybrid sites. Nature 468, 713–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flis J et al. (2018) tRNA Translocation by the Eukaryotic 80S Ribosome and the Impact of GTP Hydrolysis. Cell Rep. 25, 2676–2688.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spahn CMT et al. (2004) Domain movements of elongation factor eEF2 and the eukaryotic 80S ribosome facilitate tRNA translocation. EMBO J. 23, 1008–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne GJ and Proud CG (2002) Regulation of peptide-chain elongation in mammalian cells. Eur. J. Biochem 269, 5360–5368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behrmann E et al. (2015) Structural snapshots of actively translating human ribosomes. Cell 161, 845–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellen CUT (2018) Translation Termination and Ribosome Recycling in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 10, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dever TE and Green R (2012) The elongation, termination, and recycling phases of translation in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 4, a013706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisareva VP et al. (2011) Dissociation by Pelota, Hbs1 and ABCE1 of mammalian vacant 80S ribosomes and stalled elongation complexes. EMBO J. 30, 1804–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Elzen AMG et al. (2014) Dom34-Hbs1 mediated dissociation of inactive 80S ribosomes promotes restart of translation after stress. EMBO J. 33, 265–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B and Qian S-B (2016) Characterizing inactive ribosomes in translational profiling. Transl. (Austin, Tex.) 4, e1138018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engmann L et al. (2006) Progesterone regulation of human granulosa/luteal cell viability by an RU486-independent mechanism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 91, 4962–4968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peluso JJ et al. (2005) Expression and function of PAIRBP1 within gonadotropin-primed immature rat ovaries: PAIRBP1 regulation of granulosa and luteal cell viability. Biol. Reprod 73, 261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Y-J et al. (2014) Localization of SERBP1 in stress granules and nucleoli. FEBS J. 281, 352–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X et al. (2020) An ortholog of the Vasa intronic gene is required for small RNA-mediated translation repression in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117, 761–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C et al. (2017) TEG-1 CD2BP2 controls miRNA levels by regulating miRISC stability in C. elegans and human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 1488–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mari Y et al. (2015) SERBP1 Is a Component of the Liver Receptor Homologue-1 Transcriptional Complex. J. Proteome Res 14, 4571–4580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Dyke N et al. (2006) Stm1p, a ribosome-associated protein, is important for protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under nutritional stress conditions. J. Mol. Biol 358, 1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi H et al. (2018) Tight interaction of eEF2 in the presence of Stm1 on ribosome. J.Biochem 163, 177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells JN et al. (2020) Structure and function of yeast Lso2 and human CCDC124 bound to hibernating ribosomes. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muto A et al. (2018) The mRNA-binding protein Serbp1 as an auxiliary protein associated with mammalian cytoplasmic ribosomes. Cell Biochem. Funct 36, 312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee Y-J et al. (2012) Protein arginine methylation of SERBP1 by protein arginine methyltransferase 1 affects cytoplasmic/nuclear distribution. J. Cell. Biochem 113, 2721–2728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martini S et al. (2021) A genetically-encoded crosslinker screen identifies SERBP1 as a PKCε substrate influencing translation and cell division. Nat. Commun 12, 6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou H et al. (2013) Toward a comprehensive characterization of a human cancer cell phosphoproteome. J. Proteome Res 12, 260–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito  et al. (2017) Human Regulatory Protein Ki-1/57 Is a Target of SUMOylation and Affects PML Nuclear Body Formation. J. Proteome Res 16, 3147–3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choudhary C et al. (2009) Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science 325, 834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huttlin EL et al. (2010) A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 143, 1174–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Needham EJ et al. (2019) Phosphoproteomics of Acute Cell Stressors Targeting Exercise Signaling Networks Reveal Drug Interactions Regulating Protein Secretion. Cell Rep. 29, 1524–1538.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballif BA et al. (2004) Phosphoproteomic analysis of the developing mouse brain. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 1093–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen JV et al. (2006) Global, In Vivo, and Site-Specific Phosphorylation Dynamics in Signaling Networks. Cell 127, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung GA et al. (2011) Methylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 induced by basic fibroblast growth factor via mitogen-activated protein kinase. Exp. Mol. Med 43, 550–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hizli AA et al. (2013) Phosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) by cyclin A-cyclin-dependent kinase 2 regulates its inhibition by eEF2 kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol 33, 596–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YJ et al. (2018) Lso2 is a conserved ribosome-bound protein required for translational recovery in yeast. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Dyke N et al. (2013) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Stm1p facilitates ribosome preservation during quiescence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 430, 745–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cuomo CA et al. (2012) Microsporidian genome analysis reveals evolutionary strategies for obligate intracellular growth. Genome Res. 22, 2478–2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corradi N (2015) Microsporidia: Eukaryotic Intracellular Parasites Shaped by Gene Loss and Horizontal Gene Transfers. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 69, 167–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barandun J et al. (2019) Evolutionary compaction and adaptation visualized by the structure of the dormant microsporidian ribosome. Nat. Microbiol 4, 1798–1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicholson D et al. (2021) “Lose-to-gain” adaptation to genome decay in the structure of the smallest eukaryotic ribosomes. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/2021.09.06.458831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thoms M et al. (2020) Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science (80-.) 369, 1249 LP–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferguson A et al. (2015) Functional Dynamics within the Human Ribosome Regulate the Rate of Active Protein Synthesis. Mol. Cell 60, 475–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zinoviev A et al. (2019) Two classes of EF1-family translational GTPases encoded by giant viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5761–5776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi KH (2012) Viral polymerases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 726, 267–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walsh D and Mohr I (2011) Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 9, 860–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vazquez C et al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 16, e0253089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lokugamage KG et al. (2015) Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus nsp1 Inhibits Host Gene Expression by Selectively Targeting mRNAs Transcribed in the Nucleus while Sparing mRNAs of Cytoplasmic Origin. J. Virol 89, 10970–10981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Narayanan K et al. (2008) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 suppresses host gene expression, including that of type I interferon, in infected cells. J. Virol 82, 4471–4479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banerjee AK et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 Disrupts Splicing, Translation, and Protein Trafficking to Suppress Host Defenses. Cell 183, 1325–1339.e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lapointe CP et al. (2021) Dynamic competition between SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 and mRNA on the human ribosome inhibits translation initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 118, e2017715118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schubert K et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 27, 959–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCaughan UM et al. (2016) Pre-40S ribosome biogenesis factor Tsr1 is an inactive structural mimic of translational GTPases. Nat. Commun 7, 11789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heuer A et al. (2017) Cryo-EM structure of a late pre-40S ribosomal subunit from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Elife 6, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strunk BS et al. (2012) A translation-like cycle is a quality control checkpoint for maturing 40S ribosome subunits. Cell 150, 111–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frolova LY et al. (2000) Translation termination in eukaryotes: polypeptide release factor eRF1 is composed of functionally and structurally distinct domains. RNA 6, 381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bertram G et al. (2000) Terminating eukaryote translation: domain 1 of release factor eRF1 functions in stop codon recognition. RNA 6, 1236–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rollins MG et al. (2021) Negative charge in the RACK1 loop broadens the translational capacity of the human ribosome. Cell Rep. 36, 109663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Buttgereit F and Brand MD (1995) A hierarchy of ATP-consuming processes in mammalian cells. Biochem. J 312 (Pt 1, 163–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mayer C and Grummt I (2006) Ribosome biogenesis and cell growth: mTOR coordinates transcription by all three classes of nuclear RNA polymerases. Oncogene 25, 6384–6391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kos-Braun IC and Koš M (2017) Post-transcriptional regulation of ribosome biogenesis in yeast. Microb. cell (Graz, Austria) 4, 179–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ashe MP et al. (2000) Glucose depletion rapidly inhibits translation initiation in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 833–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balagopal V and Parker R (2011) Stm1 modulates translation after 80S formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 17, 835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heesom KJ and Denton RM (1999) Dissociation of the eukaryotic initiation factor-4E/4E-BP1 complex involves phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by an mTOR-associated kinase. FEBS Lett. 457, 489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hay N and Sonenberg N (2004) Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 18, 1926–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Magnuson B et al. (2012) Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signalling networks. Biochem. J 441, 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang J and Manning BD (2008) The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem. J 412, 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gwinn DM et al. (2008) AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beese CJ et al. (2019) Selective Autophagy of the Protein Homeostasis Machinery: Ribophagy, Proteaphagy and ER-Phagy. Front. cell Dev. Biol 7, 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takei N and Nawa H (2014) mTOR signaling and its roles in normal and abnormal brain development. Front. Mol. Neurosci 7, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Megat S et al. (2019) Nociceptor Translational Profiling Reveals the Ragulator-Rag GTPase Complex as a Critical Generator of Neuropathic Pain. J. Neurosci 39, 393–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saba JA et al. (2021) Translational control of stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 22, 671–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Piccirillo CA et al. (2014) Translational control of immune responses: from transcripts to translatomes. Nat. Immunol 15, 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wolf T et al. (2020) Dynamics in protein translation sustaining T cell preparedness. Nat. Immunol 21, 927–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Viveka M et al. (2009) Quantitative Phosphoproteomic Analysis of T Cell Receptor Signaling Reveals System-Wide Modulation of Protein-Protein Interactions. Sci. Signal 2, ra46–ra46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hwang J-R et al. (2020) Recent insights of T cell receptor-mediated signaling pathways for T cell activation and development. Exp. Mol. Med 52, 750–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carlberg U et al. (1990) Functional properties of phosphorylated elongation factor 2. Eur. J. Biochem 191, 639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Proud CG (2015) Regulation and roles of elongation factor 2 kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans 43, 328–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Karakas D and Ozpolat B (2020) Eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase (eEF2K) signaling in tumor and microenvironment as a novel molecular target. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 98, 775–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johanns M et al. (2017) Direct and indirect activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase by AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell. Signal 36, 212–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leprivier G et al. (2013) The eEF2 kinase confers resistance to nutrient deprivation by blocking translation elongation. Cell 153, 1064–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taha E et al. (2020) eEF2/eEF2K Pathway in the Mature Dentate Gyrus Determines Neurogenesis Level and Cognition. Curr. Biol 30, 3507–3521.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beretta S et al. (2020) Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase a Pharmacological Target to Regulate Protein Translation Dysfunction in Neurological Diseases. Neuroscience DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kenney JW et al. (2014) Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase, an unusual enzyme with multiple roles. Adv. Biol. Regul 55, 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Klinge S and Woolford JL (2019) Ribosome assembly coming into focus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20, 116–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sung M-K et al. (2016) Ribosomal proteins produced in excess are degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 2642–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gregory B et al. (2019) The small and large ribosomal subunits depend on each other for stability and accumulation. Life Sci. alliance 2, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Prossliner T et al. (2021) Corrigendum to article “Hibernation factors directly block ribonucleases from entering the ribosome in response to starvation”. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wyant GA et al. (2018) NUFIP1 is a ribosome receptor for starvation-induced ribophagy. Science 360, 751–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mills EW and Green R (2017) Ribosomopathies: There’s strength in numbers. Science 358, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lodish HF (1974) Model for the regulation of mRNA translation applied to haemoglobin synthesis. Nature 251, 385–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huang J-Y et al. (2012) Attenuation of 40S ribosomal subunit abundance differentially affects host and HCV translation and suppresses HCV replication. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Licursi M et al. (2011) In vitro and in vivo comparison of viral and cellular internal ribosome entry sites for bicistronic vector expression. Gene Ther. 18, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cheng Z et al. (2019) Small and Large Ribosomal Subunit Deficiencies Lead to Distinct Gene Expression Signatures that Reflect Cellular Growth Rate. Mol. Cell 73, 36–47.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khajuria RK et al. (2018) Ribosome Levels Selectively Regulate Translation and Lineage Commitment in Human Hematopoiesis. Cell 173, 90–103.e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Su L et al. (1993) LYAR, a novel nucleolar protein with zinc finger DNA-binding motifs, is involved in cell growth regulation. Genes Dev. 7, 735–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yonezawa K et al. (2014) Lyar, a cell growth-regulating zinc finger protein, was identified to be associated with cytoplasmic ribosomes in male germ and cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem 395, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Telkoparan P et al. (2013) Coiled-coil domain containing protein 124 is a novel centrosome and midbody protein that interacts with the Ras-guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1B and is involved in cytokinesis. PLoS One 8, e69289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ma X et al. (2018) Regulation of cell proliferation in the retinal pigment epithelium: Differential regulation of the death-associated protein like-1 DAPL1 by alternative MITF splice forms. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 31, 411–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]