Abstract

Background

During Medicare home health care (HHC), family caregiver assistance is often integral to implementing the care plan and avoiding readmission. Family caregiver training delivered by HHC clinicians (nurses and physical therapists [PTs]) helps ensure caregivers' ability to safely assist when HHC staff are not present. Yet, family caregiver training needs often go unmet during HHC, increasing the risk of adverse patient outcomes. There is a critical knowledge gap regarding challenges HHC clinicians face in providing necessary family caregiver training.

Methods

Multisite qualitative study using semi‐structured, in‐depth key informant interviews with Registered Nurses (n = 11) and PTs (n = 8) employed by four HHC agencies. Participating agencies were diverse in rurality, scale, ownership, and geographic region. Key informant interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using directed content analysis to identify existing facilitators and barriers to family caregiver training during HHC.

Results

Clinicians had an average of 9.3 years (range = 1.5–23 years) experience in HHC, an average age of 45.1 years (range = 28–63 years), and 95% were female. Clinicians identified facilitators and barriers to providing family caregiver training at the individual, interpersonal, and structural levels. The most salient factors included clinician–caregiver communication and rapport, accuracy of hospital discharge information, and access to resources such as additional visits and social work consultation. Clinicians noted the COVID‐19 pandemic introduced additional challenges to providing family caregiver training, including caregivers' reduced access to hospital staff prior to discharge.

Conclusions

HHC clinicians identified a range of barriers and facilitators to delivering family caregiver training during HHC; particularly highlighting the role of clinician–caregiver communication. To support caregiver training in this setting, there is a need for updated reimbursement structures supporting greater visit flexibility, improved discharge communication between hospital and HHC, and structured communication aids to facilitate caregiver engagement and assessment.

Keywords: caregiving, home care services, home health care, Medicare, training

Key points

During home health, clinicians face a range of barriers to successfully delivering caregiver training, including factors at the individual, interpersonal, and structural levels.

The most salient factors included clinician–caregiver communication and rapport, accuracy of hospital discharge information, and access to resources such as additional visits and social work consultation.

Why does this paper matter?

To support caregiver training in this setting, and thus improve patient outcomes following hospital discharge, there is a need for updated reimbursement structures, improved hospital–home health agency communication, and tools for home health clinicians to facilitate caregiver engagement and assessment.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 18 million 1 family and unpaid caregivers (hereafter, “caregivers”) serve as a crucial resource in the care of older adults, 1 , 2 including during Medicare home health care (HHC) episodes. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 The Medicare HHC benefit provides skilled nursing, rehabilitation therapy, and personal care aide visits delivered in the patient's home. HHC is indicated for homebound older adults who experience a deterioration in health status (often following hospitalization) and require temporary skilled care and monitoring to remain safely in the community. HHC accounts for 39% of all postacute care referrals for hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries 7 and 3.4 million beneficiaries receive HHC annually. 8 HHC utilization has risen markedly in recent years, with a 59% increase in the number of episodes between 2000 and 2016. 8 This trend intensified during the COVID‐19 pandemic given concerns over high infection rates in institutional postacute care settings. 9

Due to intermittent staff presence in the home and patients' complex social and medical needs, 10 HHC clinicians (including nurses, physical, and occupational therapists) rely on caregiver assistance to implement the care plan. 5 Prior work found that clinicians reported a need for caregiver assistance in 87% of HHC episodes. 5 As HHC referral follows hospitalization and/or deterioration in the older adult's condition, caregivers often adopt new responsibilities—such as assisting with medical and self‐care tasks 5 , 11 —and more than one‐third (36%) who assist during HHC have a clinician‐identified training need. 12 In recognition of these needs, the Medicare Conditions of Participation for Home Health require agencies to provide caregiver training. 13 Addressing caregiver training needs has been linked to a range of positive outcomes during HHC, including reduced visit intensity and costs of care, 14 increased likelihood of remaining in the community rather than transitioning to institutional care, 11 and reduced hospitalization risk. 15

In recent work, HHC clinicians emphasized the importance of caregiver training to determining patient outcomes 11 and caregivers reported that training helped them safely and confidently provide care. 16 Yet, nearly half of caregivers who have a clinician‐identified training need during HHC fail to receive training 15 and caregivers report that training is often insufficient and/or misaligned with their concerns and needs 16 To our knowledge, no prior study has identified major barriers and facilitators to clinician‐led caregiver training during HHC; identifying these factors is a necessary first step toward developing strategies to enhance caregiver training and engagement in this setting. Based on semi‐structured key informant interviews with HHC clinicians from a diverse set of agencies across the United States, we present key barriers and facilitators to caregiver training, including new challenges related to COVID‐19. Findings are relevant to HHC agencies' efforts to deliver high‐quality, patient‐ and family‐centered care and to reduce unplanned healthcare utilization.

METHODS

Conceptual model

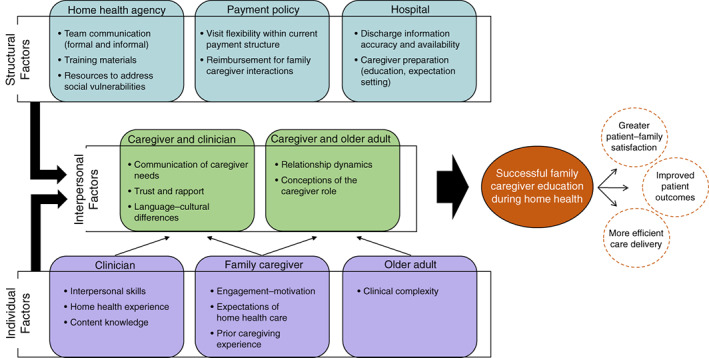

We drew on existing literature and our team's content expertise to develop a conceptual framework. 11 Prior research identified a range of factors as impactful for caregiver participation during HHC: individual factors, including older adult care needs and caregiver experience 4 , 5 , 12 , 16 , 17 ; interpersonal factors, including rapport between caregiver and clinician 18 , 19 , 20 ; and structural factors, including HHC agency resources and staffing. 6 , 17 , 21 , 22 We included these three categories as domains in our framework, which helped guide our data collection and analysis by suggesting initial areas of inquiry and related content code domains. We present a revised conceptual model, modifying our initial model based on study findings, as Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework: factors determining successful family caregiver training during home health care

Study team

The study team included two health services researchers, a practicing geriatrician, and a nurse researcher. All study team members have expertise in family caregiving and HHC and experience conducting key informant interviews and coding qualitative data. No study team member had a prior relationship with any of the key informants; the geriatrician had previously conducted unrelated research with participating agency “A.”

Participants

The study team contacted eight HHC agencies for potential inclusion in this research. Agencies were purposively selected for variation in geographic region, rurality, ownership, and scale of operations. Leaders at each agency were contacted via email to explain study aims and methods and request organizational participation. Four agencies agreed to participate, three declined by citing heightened workload due to COVID‐19, and one did not respond.

Study team members contacted individual clinicians at each participating agency to describe the study, determine their willingness to participate, and schedule interviews. Participants each received a $50 gift card following their interview. We interviewed Registered Nurses (RNs) and Physical Therapists (PTs) as these clinicians lead the HHC care team, are tasked with evaluating patients and families, and are responsible for caregiver training during HHC. Key informant enrollment was halted once we reached theoretical saturation, the point at which collection of additional data did not yield new insights related to the research question. 23 , 24 We operationalized theoretical saturation by monitoring for information redundancy 25 —once no new codes emerged from ongoing data analysis for two consecutive weeks, we concluded that theoretical saturation had been reached.

Data collection

We created a semi‐structured interview guide (Table S1) based on study team expertise, our conceptual framework, 11 and existing literature. 4 , 5 , 12 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 Interviews were conducted between August and October 2020 during the second surge of the COVID‐19 pandemic, prompting inclusion of questions regarding the pandemic's effect on interactions with caregivers. Using this guide, study team members (JB, AA) conducted semi‐structured, one‐on‐one telephone interviews (ranging in length from 30 to 54 min) with participants. We audio‐recorded and transcribed each interview verbatim. During weekly study team meetings, revisions to the interview guide were proposed, discussed, and adopted via group consensus. The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

We identified major themes using directed content analysis, in which researchers examined interview transcripts line‐by‐line and categorized each section of text by assigning a code. 23 , 26 Content codes are labels that formally catalog key concepts from qualitative research, while preserving the context in which they emerged. 23 , 26 Study team members independently coded a subset of seven interview transcripts, creating individual initial coding templates guided in part by the conceptual framework. The study team met to compare these templates and reach consensus on a single preliminary coding template.

In addition to the formal coding template, study team members practiced in vivo coding by identifying codes that emerged from the data, which had not been anticipated by the conceptual framework or initial coding template. In this way, we employed both inductive and deductive coding strategies. 27 The coding template was iteratively adjusted to incorporate new codes through team discussions at weekly meetings. Each transcript was independently coded by at least two members of the study team, and differences in coding were discussed and adjudicated, a process known as investigator triangulation, to ensure analytic rigor. 23 , 28 The audit trail for this study included interview recordings and transcripts, detailed notes from weekly team meetings during the data collection and analysis phases, and investigators' field notes (capturing reflections and reactions following each interview) and analytic memos (detailing key findings and proposed coding template revisions during data analysis). Analysis was facilitated by Atlas.ti version 8.4 (Atlas.ti, Berlin, Germany).

RESULTS

Of the participating agencies, one was rural and three were urban; one was for‐profit and three were not‐for‐profit; two operated on a local scale, one on a regional scale, and one on a national scale (Table 1). We interviewed 19 clinicians: 11 RNs and 8 PTs. Participants' average age was 45.1 years, average tenure in HHC was 9.3 years, and the majority were female (94.7%) and white (89.5%) (Table 1). Clinicians described factors that impacted their delivery of caregiver training. These factors fell into three categories: individual, interpersonal, and structural. Clinician accounts revealed that each factor could manifest as a facilitator or barrier to training. In Tables 2, 3, and 4, we define each factor and illustrate its potential as a facilitator or barrier using representative quotes from our interviews; we also present clinician perspectives on how the COVID‐19 pandemic affected each category of factors.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participating home health agencies (n = 4) and key informants (n = 19)

| Home health agency characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency identifier | Geographic region | Rurality | Ownership | Scale of operations |

| A | Mid‐Atlantic | Urban | Not‐for‐profit | Local |

| B | West | Urban | Not‐for‐profit | Regional |

| C | Southwest | Rural | For‐profit | National |

| D | Northeast | Urban | Not‐for‐profit | Local |

| Key informant characteristics | n (%) or mean (range) | |||

| Age | 45.1 (28 to 63) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 18 (94.7%) | |||

| Male | 1 (5.3%) | |||

| Race a | ||||

| White | 17 (89.5%) | |||

| Black | 1 (5.3%) | |||

| Licensure | ||||

| RN | 11 (57.9%) | |||

| PT | 8 (42.1%) | |||

| Years of home health care experience | 9.3 (1.5 to 23) | |||

| Agency of employment (study identifier) | ||||

| A | 6 (31.6%) | |||

| B | 4 (21.0%) | |||

| C | 6 (31.6%) | |||

| D | 3 (15.8%) | |||

One key informant declined to share their race.

TABLE 2.

Structural factors affecting family caregiver training in home health care

| Structural factor | Factor as facilitator | Factor as barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Formal team communication: Structures and policies guiding formal care team interactions. | “We do regular interdisciplinary phone calls… I think those help a lot.” (RN, agency D) | “In home care it's hard because you work independently a lot. You're alone a lot.” (RN, agency A) |

| Informal team communication: Organizational norms for informal care team interactions. | “We collaborate with other colleagues that go in…we do a lot of talking to each other about further teaching.” (RN, agency C) | “Some nurses are willing to help you and some nurses would just be like, ‘That's not my patient.’” (PT, agency D) |

| Training materials: Availability, quality, and scope of agency‐provided training materials. | “We have a bunch of different tools that help us help [caregivers].” (RN, agency A) | “The educational materials that we have…are definitely not very user friendly.” (PT, agency C) |

| Resources to address social vulnerabilities: Ability to connect caregivers with supports related to social needs. | “It does help to have my social work department, who we can always call and get support from.” (RN, agency B) | “It's now dealing with social work issues… something that should've been simple from a skills perspective is now so much more complicated” (RN, agency A) |

| Visit flexibility: Ability to change the number/timing of visits as needed. | “If I say, ‘They're going to take two hours for the patient and the caregiver…lighten my load a little bit’ [managers] understand.” (RN, agency B) | “Some [insurers] are really stingy with visits. And I just cannot get it done in the number of visits.” (PT, agency C) |

| Discharge information: Accuracy of information regarding prior care and ongoing needs. | “Knowing that there would be [a caregiver] there…we would hope that would be included in their referral.” (PT, agency A) | “They give us a brief background of the patient…but that's not always accurate. You kind of go in blindly…in the house can be something completely different.” (RN, agency D) |

| Caregiver preparation: Education–communication regarding their role postdischarge and the role of home health care. | “We try to do a lot of just kind of intercepting at the hospital and kind of getting them a little bit more comfortable with the idea of being on home health…they have done really well with that.” (RN, agency B) | “They did not realize until the patient was in the home… they are realizing that they are drowning and have no clue what they are doing” (RN, agency A) |

|

Impact of COVID‐19 on Structural Factors: Personal protective equipment (PPE) as an obstacle to effective communication “It does create some challenges especially with just masking in general if you have an older patient and older caregiver, sometimes they cannot hear you that well and then they cannot read your lips, so that can create a challenge as well.” (RN, agency B) “They'll say, ‘I cannot see your face. I want to see what you look like,’…we are supposed to look at each other and talk.” (RN, agency C) “People aren't willing to wear their mask, so they'll leave the room and I cannot get all of my questions answered or that super in‐depth education that's necessary.” (RN, agency B) | ||

TABLE 3.

Individual factors affecting family caregiver training in home health care

| Individual factor | Factor as facilitator | Factor as barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician interpersonal skills: Aptitude for interacting with others, reading and responding to social cues. | “I'm a people person. You have to like to engage people and talk with them, and you have to have patience, to be calm.” (RN, agency D) | “There's some people…maybe they are not really good at talking to people and that kind of dictates…if they are in patient care or not.” (RN, agency A) |

| Clinician home health experience: Tenure working in home health care, familiarity with this unique setting. | “The whole time you are in home care, you just learn something new… It's constant learning, how to properly deal with caregivers.” (PT, agency A) | “When I was a new therapist in the home, I probably just treated the patient more than looked at the entire situation. And as years go by, you think, ‘Wow. This is a bigger scenario.’”(PT, agency B) |

| Caregiver engagement/motivation: Willingness and interest in learning more related to their caregiving role. | “Really the most important thing‐‐ you can teach anyone who is willing.” (RN, agency A) | “The greatest barrier to caregiver training is that the caregiver does not want to be trained.” (PT, agency D) |

| Caregiver expectations of home health care: Expectations regarding scope of care and patient outcomes. | “Caregiver expectations certainly factor in because we need to finesse‐‐ we are not there for our goals. We're there for theirs.” (RN, agency A) | “Things that get in the way are caregiver expectations of what home care is…goals for the patient [that] are very unrealistic.” (PT, agency A) |

| Caregiver experience: Prior caregiving experience and expertise. | “There are a lot of caregivers who have been trained in range of motion… I will say “You probably already know this.” (PT, agency A) | “They say, ‘Well, we have our own way of doing it,’ and, you know, their own way may be very unsafe…But they do not want to change it.” (PT, agency D) |

|

Impact of COVID‐19 on Individual Factors: Increased severity of patient clinical needs and decreased caregiver preparation “I think the complexity of our patients have gotten so much more so that it's almost not always realistic for some of these patients to be coming to us in home care as soon as they do, and part of the problem is caregivers not wanting their family members to go to rehabs or skilled nursing facilities…because of fear regarding COVID.” (RN, agency A) “Because of COVID, a lot of our patients are opting not to go to subacute rehab. So, we are sort of seeing this skewed population right now, I think.” (PT, agency A) “COVID has undermined the caregiver and patient preparation in the hospitals horribly… the first time that the family is seeing the patient is when they pick them up at the hospital. The family wasn't included in the review of the discharge instructions…So very ill‐prepared. Unprepared. Blindsided.” (RN, agency A) “Having the caregiver in the hospital before…they maybe had some training in the hospital before they came home, or the rehab center. But now it's all on us. So it is a much harder, more complicated scene, because we are doing more than what we would normally do.” (PT, agency B) | ||

TABLE 4.

Interpersonal factors affecting family caregiver training in home health care

| Interpersonal factor | Factor as facilitator | Factor as barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician/caregiver communication regarding caregiver needs: Willingness/ability to discuss caregiver needs | “I always start with ‘What would you like from me?’… usually the caregiver can voice what they need as far as training.” (PT, agency C) | “I cannot force [a caregiver] to come downstairs…to want to take your time out to show me what you know [how] to do already.” (RN, agency A) |

| Clinician/caregiver relationship and rapport: | “Not all people get along…I think they are more willing to listen if they truly like us.” (RN, agency A) | “Sometimes I'll have another nurse go in… Because sometimes it's just a personality difference.” (RN, agency B) |

| Clinician/caregiver development of trust: | “If they feel that that nurse cares about them, they are going to open up and they are going to share what their‐‐ what's stopping them.” (RN, agency B) | “Sometimes it takes a couple of sessions to gain their confidence and acceptance of you even being there…They feel it's been forced upon them by the hospital or the doctor.” (PT, agency C) |

| Clinician/caregiver language or cultural differences: | Clinicians did not identify this factor as a potential facilitator. | “The biggest barrier that we have with anything is pretty much a language barrier.” (RN, agency B) |

| Caregiver/patient relationship dynamics: Underlying feelings and patterns of behavior attached to the relationship. | “If the caregiver shows compassion [to the patient]… then obviously that kind of sticks out.” (PT, agency C) | “What was that history between this caregiver and the woman who …was kind of a jerk to her family for 40 years? That caregiver's probably not gonna be real receptive.” (RN, agency C) |

| Caregiver/patient conceptions of the caregiver role: Degree of convergence in expectations and preferences regarding the scope of caregiver involvement. | “If they say ‘I could not do this without my daughter,’… daughter's there on every visit and she texts or calls me, I mean, then I know I have someone really engaged.” (RN, agency A) | “The caregiver's super willing but the patient is the one who's resistant. They want to be independent but it's not possible.” (RN, agency B) |

|

Impact of COVID‐19 on Interpersonal Factors: Heightened emotions for patient and caregiver “Caregivers I feel are more relieved that we are still coming to see their loved one.” (RN, agency B) “People do not want us in their home. They're afraid we are bringing the black plague in, and people have just been unkind, I think.” (RN, agency D) “You can tell people are afraid, and they are afraid of getting sick and being exposed to things, and caregivers and patients alike.” (PT, agency B) “You cannot teach somebody who's anxious. That's a block to learning…” (RN, agency A) | ||

Structural factors

Structural factors include those beyond the direct control of the clinician, patient, or caregiver, which affect the success of caregiver training (Table 2). Clinicians noted that disjointed information transfer during the hospital‐to‐home transition was a barrier to delivering training. Information included in the HHC referral regarding the family context was often inaccurate or inadequate and “if the referral says that the caregiver's gonna be such‐and‐such… and they're nowhere to be found and the number doesn't work, well, that's not very fun to find out while you're there [in the home]” (RN, agency A). Families received minimal information regarding their role in HHC or the purpose of HHC and “oftentimes they have no idea what they're actually biting off…” (RN, agency A) leading to misaligned expectations between caregiver and HHC clinician. Clinicians noted the need for payment models that allow greater visit flexibility, saying “to kind of follow‐up with that training… it requires at least a few more visits, and sometimes we don't really get those [due to payor policies]” (PT, agency C).

Clinicians identified agency‐level policies and practices that supported caregiver training, including efforts to allow visit flexibility: “Some of the insurance – the carriers tell you ‘You have four visits, and get it done in four visits’…[my agency] will fight for me if I feel I need more visits” (RN, agency C) and “My company isn't like ‘you have to be out of there by a certain time.’ It's definitely flexible…” (RN, agency B). Agency policies that encourage team communication were also reported to facilitate successful training, regardless of whether communication was formal— “encouraging communication amongst each other has been helpful, and sometimes the way you do that is by mandating it, like ‘you guys need to be sending case communications…[or] it's gonna be dinged on your review’ (RN, agency A)—or informal—“two of our offices kind of got together and…brought all of our education materials together in one room and we kind of had like a little happy hour social thing…we all just got to pick things that we liked” (PT, agency C).

Clinicians discussed how personal protective equipment (PPE), a structural change made necessary by the COVID‐19 pandemic, was an impediment to communicating with patients and caregivers. Some caregivers were unwilling to don a mask and thus could not safely remain in the room with the clinician to receive education. Masks made it more difficult for patients and caregivers with hearing impairment as “they can't hear you that well and then they can't read your lips” (RN, agency B). PPE obscured clinicians' facial expressions and “the personal relationship has changed a little bit because of that because it just feels so weird” (RN, agency C), which clinicians reported hindered their ability to communicate and build trust.

Individual factors

Clinicians cited individual factors, including their own communication skills and caregivers' motivation to learn, as determinants of successful caregiver training (Table 3). Clinicians emphasized the importance of being a “people person” (RN, agency D), “knowing how to read people” (RN, agency C), and being able to clearly communicate clinical information since caregivers “don't want to do something just because you tell them they should. They want to understand why” (PT, agency A). Clinicians also noted the importance of caregivers' personality and motivation, particularly emphasizing that “receptiveness to critique… is a big [facilitator]” (PT, agency C) and “having a caregiver that's really ready to learn and not just being the caregiver so [the older adult] can get out of the hospital quicker…the ones that are actually involved always are an asset” (RN, agency A).

Clinicians reported that the COVID‐19 pandemic led to increased patient clinical complexity due to fears over infection rates in institutional postacute care settings and hospital efforts to decrease length of stay amid rising patient volumes. As one clinician described, “Because of COVID, a lot of our patients are opting not to go to subacute rehab. So, we're sort of seeing this skewed population right now, I think”—(PT, agency A). Simultaneously, restrictions on hospital visitation meant that caregivers had limited understanding of the care received by the older adult and limited opportunity for education during the hospitalization, with the result that “COVID has undermined caregiver and patient preparation in the hospital horribly” (RN, agency A). These concurrent trends presented a significant challenge for HHC clinicians, who were tasked with caring for notably sicker patients while needing to provide a greater amount of caregiver education.

Interpersonal factors

The theme heard most frequently in our interviews was the critical importance of interpersonal factors (relational aspects between clinician, caregiver, and patient) in determining the success of caregiver training (Table 4). The clinician–caregiver relationship was particularly critical, and clinicians highlighted the importance of demonstrating concern for the caregiver's individual needs. Clinicians reported “asking [caregivers] what their struggles are with the patient so that you're engaging them in something they themselves may find beneficial…[this] may get them to buy in a little bit more” (PT, agency D). Clinicians noted the importance of building trust and rapport with caregivers—“it's almost like counseling, in a way‐ not in a way, it's always counseling” (RN, agency C)—by “[making] sure they know nothing is a test” (RN, agency D) and “saying ‘We're here for you. You are the caregiver for our patient…you're part of the puzzle piece too’” (PT, agency B).

Underlying strain or conflict in patient–caregiver relationships presented a barrier to training. Caregiver engagement “depends on the dynamics between them [caregiver and patient]” (PT, agency C) and if “they're not in the best relationship…sometimes they're just not willing to do wound care or something like that” (RN, agency C). Patients and caregivers may disagree regarding the caregiver's role, for example, “the caregiver's super willing but the patient is the one who's resistant. They want to be independent but it's not possible” (RN, agency B) or “the [caregiver's] been with this person for a long time, and the changes have happened gradually over time, and they may not have picked up on this person's needs” (RN, agency C).

Amid COVID‐19, interpersonal interactions were affected by heightened emotions associated with the pandemic. Clinicians stated that families were “afraid we're bringing the black plague in” (RN, agency D). Feelings of suspicion regarding the existence or severity of COVID‐19 led to “resistance that's met with when we're trying to educate people on [COVID‐19 precautions]… it's probably not gonna be super‐successful, because it's gonna create a drama in that teaching process” (RN, agency A).

Revised conceptual model

Figure 1 presents a novel conceptual model of successful caregiver training during HHC, informed by study findings. Structural factors (including HHC agency and hospital actions and payment policy realities) and individual factors (including caregiver expectations and experience, and clinician interpersonal skills and knowledge) create the context for interpersonal interactions. These interpersonal interactions, particularly communication and trust built between caregiver and clinician, are the most critical determining factors for successful caregiver education.

DISCUSSION

In this multisite, qualitative study, HHC nurses and PTs identified multiple factors that affected their efforts to train and prepare caregivers to safely support older adults in their homes. This is the first study to present HHC clinician perspectives on barriers and facilitators to caregiver training and findings informed the creation of a conceptual model elucidating structural, individual, and interpersonal factors affecting successful caregiver training in HHC. This model identifies target areas for policy and clinical interventions with high potential to positively impact caregiver engagement and education. Clinicians noted important barriers to their training efforts, including payment models, which incentivize providing fewer visits, caregiver resistance or lack of engagement, and poor information exchange and expectation‐setting between hospital, caregiver, and HHC agency.

Clinicians described strategies to build trust—identified as a major facilitator of successful training—including developing rapport over repeated visits, but described these efforts as hampered by existing policies. Participants reported that existing payment systems, which may constrain the number and duration of visits, 17 , 29 present a barrier to training by reducing clinician–caregiver interactions and inhibiting continuity of care (receiving multiple visits from the same provider). To mitigate these barriers, agencies could offer asynchronous, virtual training resources 30 , 31 for use when additional visits are not financially feasible. Ultimately, HHC payment system reforms are needed to reimburse time spent supporting caregivers, perhaps screening to identify high‐need caregivers and enabling reimbursement for a designated caregiver‐training visit. Given the evidence that meeting caregiver training needs reduces the number of nursing and therapy visits required during HHC14 and decreases readmission risk, 15 such reforms could prove cost‐effective.

Caregiver motivation is a critical component of successful training but may be lacking due to experiences of burden and lack of support and compensation for the caregiving role. 1 Clinicians stated that failing to tailor training to individual needs and circumstances may reduce caregiver engagement and motivation. This finding aligns with caregiver assessment best practices 32 and prior qualitative work, in which caregivers expressed frustration at HHC clinicians' perceived failure to offer support aligned to their specific needs. 16 Standardized Medicare HHC patient assessments once included designated questions regarding individual caregivers' task‐specific capacity and needs. However, these items were removed in 2018 33 and in a recent qualitative study, HHC clinicians reported having no standardized means to gather and track this information. 11 Therefore, what caregivers experience as indifference to their needs may be the result of HHC clinicians' efforts to understand and address complex support needs amid a hectic home visit without the benefit of a structured assessment instrument or supportive payment systems.

Clinicians identified inadequate information transfer during hospital discharge as a barrier to effective caregiver training. Existing research highlights the challenges HHC staff face in delivering high‐quality care without accurate and adequate referral information 6 , 34 , 35 ; the present study adds to this literature by identifying the need for information not only about the patient, but also the family context and expected supports in the home. There is growing interest in harnessing the electronic health record to gather, store, and share this information. 1 , 36 However, this work is still nascent and faces challenges, including when and how to identify caregivers, limited interoperability between care settings, and shifting caregiver involvement across the life course. 1 , 36 In the meantime, systems can adopt interventions to strengthen communication prior to HHC initiation, including embedding HHC case managers in the hospital, expanding caregiver involvement in discharge planning, and offering personal health records adapted for HHC and maintained by patients and families. 6 , 37 , 38

Participants reported that the COVID‐19 pandemic exacerbated underlying weaknesses in the hospital discharge process, describing how visitation limitations created a significant knowledge gap for caregivers who received limited information regarding acute treatments provided and what to expect following discharge. While lack of in‐person interaction and PPE‐related communication barriers presented new challenges, concerns regarding poor integration of caregivers into discharge planning and limited education and training for caregivers prior to hospital discharge predate the pandemic. 6 , 39 Our findings suggest that ongoing work aimed at screening and engaging caregivers during the discharge process 37 , 39 , 40 should consider digital communication strategies in parallel with in‐person interactions, to guard against future health shocks, which limit caregivers' physical presence in the hospital.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate facilitators and barriers to caregiver training during HHC and provide foundational evidence to support intervention development in this space. There may be meaningful differences between the HHC agencies and clinicians who chose to participate and those who did not, limiting the transferability of our findings. However, participating agencies were diverse across key characteristics, including rurality, size, and for‐profit status. Participants were primarily white and female, reflecting the demographics of the overall RN and PT workforce. 41 Clinicians of different gender or racial–ethnic backgrounds may interact differently with caregivers, and future studies may consider oversampling this population. We interviewed RNs and PTs because they are primarily responsible for the development and execution of the caregiver education plan; we did not interview social workers, administrators, or family caregivers who would also have valuable perspectives on this topic. We strengthened the reliability, rigor, and credibility of our analyses by using qualitative research strategies, including an audit trail, investigator triangulation, and thick description. 23 , 28 , 42

CONCLUSION

HHC clinicians identified a range of individual, interpersonal, and structural factors, which impacted their ability to deliver effective caregiver training to support older adults. The COVID‐19 pandemic both exacerbated the need for caregiver training in HHC and simultaneously introduced a range of new challenges to providing such training. Coordinated, evidence‐based action on the part of researchers, policymakers, hospitals, and HHC agencies is needed to address existing structural barriers and create an environment conducive to successful clinician–caregiver interactions to support older adults after hospital discharge. Study findings and the novel conceptual model lay the groundwork for future research, intervention development, and policymaking in this area by identifying areas of challenge and opportunity related to this crucial aspect of HHC care delivery meant to facilitate older adults remaining safely in their homes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Julia G Burgdorf: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and preparation. Jennifer L Wolff: study supervision, data interpretation, manuscript editing. Jo‐Ana Chase: manuscript editing. Alicia I Arbaje: study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

No sponsor had any role in study design, data analysis and interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Supporting information

Data S1. Interview guide exploring barriers and facilitators to family caregiver training during home health care.

Table S1. Interview guide.

Burgdorf JG, Wolff JL, Chase J‐A, Arbaje AI. Barriers and facilitators to family caregiver training during home health care: A multisite qualitative analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(5):1325‐1335. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17762

Select findings from this work were presented at Gerontological Society of America (GSA) 2021 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Funding informationThis work was supported by grants from the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation [no grant number] and the National Institute on Aging (T32AG066576).

REFERENCES

- 1. National Academies of Sciences . Engineering, and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America. The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL, Fried T. Family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1821‐1828. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arbaje AI, Kansagara DL, Salanitro AH, et al. Regardless of age: incorporating principles from geriatric medicine to improve care transitions for patients with complex needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):932‐939. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2729-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bradley P. Family caregiver assessment: essential for effective home care. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29(2):29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burgdorf J, Arbaje A, Wolff J. Older adult factors associated with identified need for family caregiver assistance during home health care. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2019;32:67‐75. doi: 10.1177/1084822319876608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle‐aged and older adults receiving skilled home health care services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(2):111‐120. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu Y, Stearns SC. Post‐acute care locations: hospital discharge destination reports vs Medicare claims. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):847‐851. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. March 2019 Report to the Congress . Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2019. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/ reports/mar19_medpac_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- 9. Miller G, Rhyan C, Turner A, Hempstead K. COVID‐19 Shocks The US Health Sector: A Review Of Early Economic Impacts. Health Affairs Blog. 2020. doi: 10.1377/hblog20201214.543463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Home Health Chartbook 2018:Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation & Avalere Health. Avalere Health; 2018. http://ahhqi.org/images/uploads/AHHQI_2018_Chartbook_09.21.2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgdorf JG, Arbaje AI, Chase JA, Wolff JL. Current practices of family caregiver training during home health care: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(1):218‐227. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burgdorf JG, Arbaje AI, Wolff JL. Training needs among family caregivers assisting during home health, as identified by home health clinicians. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(12):1914‐1919. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medicare and Medicaid Program: Conditions of Participation for Home Health Agencies. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2017. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/13/2017-00283/medicare-and-medicaid-program-conditionsof-participation-for-home-health-agencies [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burgdorf JG, Stuart EA, Arbaje AI, Wolff JL. Family caregiver training needs and Medicare home health visit utilization. Med Care. 2021;59(4):341‐347. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burgdorf JG, Arbaje AI, Stuart EA, Wolff JL. Unmet family caregiver training needs associated with acute care utilization during home health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(7):1887‐1895. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chase JD, Russell D, Rice M, Abbott C, Bowles KH, Mehr DR. Caregivers' experiences regarding training and support in the post‐acute home health‐care setting. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(4):561‐569. doi: 10.1177/2374373519869156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brega A, Schlenker R, Hijjazi K, et al. Study of Medicare Home Health Practice Variations: Final Report. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/72736/epic.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chase JD, Russell D, Kaplan DB, Bueno MV, Khiewchaum R, Feldman PH. Doing the right thing: family caregivers managing medical and nursing tasks in the Postacute home health care setting. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(12):1786‐1795. doi: 10.1177/0733464820961259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho E. A proposed theoretical framework addressing the effects of informal caregivers on health‐related outcomes of elderly recipients in home health care. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2007;1(1):23‐34. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(08)60006-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Russell D, Burgdorf JG, Kramer C, Chase JD. Family Caregivers' conceptions of Trust in Home Health Care Providers. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2021;14(4):200‐210. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20210526-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Irani E, Hirschman KB, Cacchione PZ, Bowles KH. The role of social, economic, and physical environmental factors in care planning for home health care recipients. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2020;13(3):130‐137. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20191210-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Irani E, Hirschman KB, Cacchione PZ, Bowles KH. Home health nurse decision‐making regarding visit intensity planning for newly admitted patients: a qualitative descriptive study. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2018;37(3):211‐231. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2018.1456997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758‐1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen K, Guest G, Namey E. Module 3: in‐depth interviews. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field Guide. Family Health International; 2005:29‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory‐based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229‐1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107‐115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldberg‐Dey J, Johnson M, Pajerowski W, Tanamor M, Ward A. Home Health Study Report. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ploeg J, Ali MU, Markle‐Reid M, et al. Caregiver‐focused, web‐based interventions: systematic review and meta‐analysis (part 2). J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):e11247. doi: 10.2196/11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ploeg J, Markle‐Reid M, Valaitis R, et al. Web‐based interventions to improve mental health, general caregiving outcomes, and general health for informal caregivers of adults with chronic conditions living in the community: rapid evidence review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e263. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caregiver Assessment: Voices and Views from the Field. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference (Vol. II). Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS‐D Guidance Manual . Washington. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/OASIS-D-Guidance-Manual-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sockolow PS, Bowles KH, Le NB, et al. There's a problem with the problem list: incongruence of patient problem information across the home care admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(5):1009‐1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones CD, Jones J, Bowles KH, et al. Quality of hospital communication and patient preparation for home health care: Results from a statewide survey of home health care nurses and staff. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(4):487‐491. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reinhard S, Young H, Choula R, Drenkard K, Suereth B. Electronic Health Record (EHR) Practices to Improve Patient and Family Engagement. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2020. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/11/electronic-health-record-practices-to-improve-patient-and-family-engagement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: the caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883‐885. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kneale L, Choi Y, Demiris G. Assessing commercially available personal health Records for Home Health: recommendations for design. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):355‐367. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2015-11-RA-0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fields B, Rodakowski J, Leighton C, Feiler C, Minnier T, James AE. Including and training family caregivers of older adults in hospital care: facilitators and barriers. J Nurs Care Qual. 2020;35(1):88‐94. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, Min SJ. Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):2‐11. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460118.60567.fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020. Accessed 2/15/22. https://www.bls.gov/cps/aa2020/cpsaat11.htm

- 42. Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120‐124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Interview guide exploring barriers and facilitators to family caregiver training during home health care.

Table S1. Interview guide.