Abstract

The peptide AS-48 is highly active on all Listeria species. It has a bactericidal and bacteriolytic mode of action on Listeria monocytogenes CECT 4032, causing depletion of the membrane electrical potential and pH gradient. The producer strain Enterococcus faecalis A-48-32, releases sufficient amounts of AS-48 into the growth medium to suppress L. monocytogenes in cocultures at enterococcus-to-listeria ratios above 1 at 37°C or above 10 at 15°C. As the temperature decreases, the bactericidal effects of AS-48 are less pronounced, but at 2.5 μg/ml it still can inhibit the growth of listeria at 6°C. AS-48 is highly active on liquid cultures, although concentrations above 0.2 μg/ml are required to avoid adaptation of listeria. AS-48-adapted cells can be selected at low (but still inhibitory) concentrations, and they can be inhibited completely by AS-48 at 0.5 μg/ml. The adaptation is lost gradually upon repeated subcultivation. AS48ad cells are cross-resistant to nisin and show an increased resistance to muramidases. Their fatty acid composition is modified: they show a much higher proportion of branched fatty acids as well as a higher C15:0 An-to-C17:0 An ratio. Resistance to AS-48 is also maintained by protoplasts from AS48ad cells. Electron microscopy observations show that the cell wall of AS48ad cells is thicker and less dense. The structure of wild-type cells is severely modified after AS-48 treatment: the cell wall and the cytoplasmic membrane are disorganized, and the cytoplasmic content is lost. Intracytoplasmic membrane vesicles are also observed when the wild-type strain is treated with high AS-48 concentrations.

In recent years, bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria have attracted great attention because of their application in food processing and preservation to control undesirable organisms such as Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium spp. (21, 23). The ingestion of products contaminated with listeriae may be a potential health threat to high-risk populations such as the immunocompromised, children, pregnant women, and senior citizens. A potential means of preserving fermented foods from outgrowth of listeriae is through the use of bacteriocin-producing starter cultures, but until now only strains of Lactococcus lactis and Pediococcus, producer strains of nisin and pediocin PA-1, respectively, have been used (29).

Nisin is undoubtedly, the most widely used bacteriocin, being used in almost 48 countries, and it has been granted the status of GRAS (generally recognized as safe) in the United States for food (5). However, nisin has several deficiencies: instability at neutral to alkaline pHs, decay in its antimicrobial activity when incorporated into complex foods, low solubility over the physiological pH range, and a spectrum of activity restricted to gram-positive bacteria. Therefore, it would be desirable to find other antimicrobial compounds which, alone or combined with nisin or other bacteriocins, could be successfully exploited as food preservatives. In this respect, enterococcal bacteriocins are under scrutiny. Although enterococci are not considered lactic acid bacteria sensu stricto, they are often isolated from dairy systems as desirable microbiota. These are the enterococci isolated from starter cultures and cheeses, where it is believed that they play a role during ripening (2, 11, 12, 19, 31). These investigations have resulted in the recognition that production of antilisterial bacteriocins is a common characteristic within this group of bacteria (19, 20, 22).

The antibacterial peptide AS-48, produced by Enterococcus faecalis S-48, is a cyclic molecule with 70 amino acid residues. It has a broad activity spectrum, being highly active against most of the gram-positive bacteria tested (6–8, 17). In contrast to other bacteriocins, AS-48 also inhibits many species of gram-negative bacteria (8). In addition to being produced by a nonhemolytic strain, AS-48 is stable over a broad range of pH values (3 to 9.5) and is sensitive to endoproteases (6). Due to these characteristics, AS-48 would be a good candidate for use as a food preservative.

In spite of the body of knowledge accumulated in recent years on the antimicrobial activity of AS-48 and its mechanism of action (8–10), its effects on food spoilage and food-borne pathogenic bacteria still remain unexplored. In this work we have chosen the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes as the target to determine the usefulness of AS-48 as a candidate to control proliferation of this bacterium, as well as the ability of the producer strain to antagonize the growth of listeriae. The bactericidal action of low AS-48 concentrations and the ability of the producer enterococcal strains to antagonize listeriae during cocultivation are outstanding. Nevertheless, we have found that listeriae can adapt to low AS-48 concentrations. AS-48-adapted cells lose this trait during repeated subcultivation and are cross-resistant to nisin. Other features of AS-48-adapted listeriae such as differences in their fatty acid composition have also been investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

E. faecalis A-48-32 was used as the AS-48 producer strain (16). E. faecalis B-48-47 (an AS-48− Bc-48− mutant derived from E. faecalis S-48) was used as the control in coculture experiments. E. faecalis S-47 from our laboratory collection was used as the standard indicator strain. The species used to determine the antilisterial activity of AS-48 are listed in Table 1 and were supplied by the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT). To study the antilisterial effects of AS-48, we chose L. monocytogenes CECT 4032, which was isolated in Colindale, United Kingdom, from a patient with meningitis associated with eating contaminated cheese. Enterococci and listeriae were grown in brain heart infusion broth (BHI broth; BBL Microbiology System, Cockeysville, Md.). When solid medium was required, BHI was supplemented with 1.5% agar (BHA). In coculture experiments, BHI broth was buffered with 0.15 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.2) (BHI-PB); Rothe azide broth (ADSA Micro, Barcelona, Spain) with 1.5% agar (RA) was used as selective medium for enterococci; the medium used for selective counting of listeriae consisted of BHA supplemented with lithium chloride at 1.5% (BHA-LC). Peptone water consisted of 0.1% peptone (by weight) in distilled water.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity of Enterococcus faecalis S-47 and different Listeria strains to peptide AS-48

| Strain | AS-48 MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| E. faecalis S-47 | 0.80 |

| L. grayi CECT 931 | 0.20 |

| L. welshimeri CECT 919 | 0.28 |

| L. murrayi CECT 942 | 0.20 |

| L. innocua CECT 4030 | 0.20 |

| L. ivanovii CECT 913 | 0.10 |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 932 | 0.10 |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 935 | 0.10 |

| L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 | 0.10 |

Antibiotic preparation and antimicrobial activity assays.

Purified preparations of the peptide AS-48 (7) were dissolved in distilled water and filter sterilized through 0.22-μm-pore-size Millipore filters. The antimicrobial activity of AS-48 against different listeria species was determined by the agar well diffusion method, and the number of arbitrary units was determined after serial dilution of samples (6, 28).

Nisaplin (kindly provided by Aplin & Barrett Ltd., Trowbridge, England) was dissolved in 20 mM HCl (pH 2.0) to give a final nisin concentration of 1000 IU/ml which corresponds to approximately 25 μg/ml according to Wilimowska-Pelc et al. (32).

Antilisterial activity tests on liquid cultures were carried out as follows. Cultures growing in BHI broth, with an absorbance at 620 nm (A620) of ca. 0.1 (approximately 108 viable cells/ml) were added to different concentrations of AS-48 or nisin. At the desired intervals, samples were removed and serially diluted into ice-cold sterile saline solution. The appropriate dilutions were plated on triplicate BHA plates, and the average number of colonies obtained after a 24-h incubation at 37°C was used to establish the growth and survival curves. Growth and lysis were monitored turbidimetrically at 620 nm by using a Spectronic-20 spectrophotometer (Bausch & Lomb, Inc., Rochester, N.Y.).

Determination of the pH gradient, membrane electrical potential, and PMF.

The effect of AS-48 on the membrane electrical potential (Δψ) and the pH gradient (ΔpH) was determined by measuring the distribution of [3H]tetraphenylphosphonium bromide and [14C]salicylic (Amersham), respectively, as described by Rottenberg (25), and the total proton motive force (PMF) was calculated by the method of Kashket et al. (14). Briefly, L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 was grown to mid-log phase (A620 = 0.4 to 0.6) in BHI broth. The cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min at 8,000 × g), washed once with 50 mM sodium N-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 6.2) containing 10 mM KCl, and resuspended in the same buffer to a cell density of ca. 0.75 mg (dry weight) per ml. The cells were energized for 15 min by adding glucose to a final concentration of 10 mM and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with increasing concentrations of AS-48 in the presence of the radiolabeled probes.

Inhibition of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 by E. faecalis A-48-32 during cocultivation.

Mixed cultures were made in BHI-PB at different enterococcus-to-listeria ratios (105:103, 105:104, and 105:105) at 6, 15, and 37°C. At the desired intervals, samples were removed for bacterial enumeration and assay of AS-48 activity in cell-free supernatants. For selective enumeration of enterococci and listeriae, appropriate dilutions were seeded on RA or BHA-LC plates, respectively. The AS-48 activity of filtered cell-free supernatants was determined by the agar well diffusion method.

Determination of the MIC.

The MIC of AS-48 for L. monocytogenes was determined by the addition of increasing concentrations (0.01 to 5 μg/ml) of the peptide to tubes containing 5 ml of BHI broth inoculated with 108 cells/ml, followed by incubation at 37°C. The lowest AS-48 concentration that prevented growth after a 24-h incubation was defined as the MIC. The cultures were incubated for further 24 h, and those showing positive growth were considered AS-48 adapted (AS48ad). The identity of the AS48ad strain with the parental strain L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 was determined with the API Listeria system (BioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Effect of cell wall-acting antibiotics on AS-48-sensitive and adapted L. monocytogenes.

Three series of eight listerial cultures grown for 24 h in BHI broth, consisting of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and the AS48ad strain (grown with or without 0.1 μg of AS-48 per ml), were transferred to fresh medium under the same conditions (with and without AS-48) and incubated for 3 h to the mid-exponential phase (A620 = 0.2-0.3). Then, ampicillin, d-cycloserine, and vancomycin (500 μg/ml each [Sigma]) were added separately to the cultures in duplicate. One of each cultures was added simultaneously of AS-48 at a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml. The A620 of the different cultures was recorded at intervals of 1 h for 9 h.

Action of lytic enzymes on AS-48-sensitive and -adapted L. monocytogenes.

Stationary-phase listeria cultures of the wild-type sensitive strain and the AS48ad strain grown without or with AS-48 (0.1 μg/ml) were transferred to fresh BHI medium under the same conditions described previously and incubated to A620 = 0.5 to 0.6. Then the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 15 min and washed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M sucrose, and either 5 mg of chicken egg white lysozyme (Sigma) per ml or 5 U of mutanolysin (Sigma) per ml, as described by Maisnier-Patin et al. (15). After 1 h or 3 h of incubation at 37°C, samples were removed from the cell suspensions, diluted in peptone water, and plated onto BHA to determine the number of remaining viable cells. The effect of muramidases was expressed as loss of viability: log CFUt0 − log CFUt’ (where CFUt0 is the CFU corresponding to the respective control without enzyme and CFUt’ is the CFU of the cells with lysozyme or mutanolysin after 1 or 3 h of incubation).

Protoplast formation.

L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and the AS48ad strain were grown for 12 h at 37°C in 100 ml of BHI medium (plus 0.1 μg of AS-48 per ml for the adapted strain), and protoplasts were prepared by the method of Ghosh and Murray (13). Protoplasts were incubated with increasing concentrations of AS-48 in protoplast buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.7], 10 mM MgCl2, 500 mM sucrose). The A620 of the protoplast suspensions was measured at regular intervals. Aliquots were removed and serially diluted in protoplast buffer before they were plated into regeneration medium consisting of BHA dissolved in protoplast buffer. Following 72 h of incubation at 37°C, the number of colonies on the plates was counted.

Lipid extraction and analysis of L. monocytogenes.

Mid-exponential-phase cultures (2 liters each) of L. monocytogenes 4032 and the AS48ad strain grown in BHI broth (with 0.1 μg of AS-48 per ml for the adapted strain) were harvested by centrifugation and washed with peptone water at room temperature. Lipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (1a) with the modifications described by Winkowski et al. (33). Briefly, the cell pellet was resuspended in chloroform–methanol–0.1 N HCl (1:2:0.8 by volume) and shaked for 2 h in the presence of glass beads (0.15 mm in diameter). Then 0.1 N HCl and chloroform were added to a final ratio of chloroform-methanol-HCl of 1:1:1 (by volume), and the mixture was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min. The organic phase was collected, and the pellet was reextracted with chloroform. The combined organic phases were neutralized with 1 N NH4OH in methanol and dried under a stream of nitrogen. Lipids were saponified and methylated as described by Smibert and Krieg (27). Briefly, the lipids were resuspended in 0.5 ml of chloroform-hexane (1:1 by volume) and saponified by adding 2 ml of 15% NaOH in 50% methanol and heating at 100°C for 30 min in Teflon-lined screw-cap tubes. The tubes were cooled to room temperature before the addition of 3 ml of 25% HCl in methanol followed by heating for 30 min and cooling. The methyl esthers of the fatty acids were extracted by adding 3 ml of ether-hexane (1:1, vol/vol) and shaking for 3 min. The tubes were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 3 min. The upper phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 2 ml of 0.5 M sodium phosphate (pH 11.0). The tube was centrifuged as above, and the organic phase was transferred to a new vial.

The fatty acid methyl esthers were separated by gas-liquid chromatography on a Carlo Erba 8060 chromatograph equipped with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm [inner diameter]) and analyzed by mass spectroscopy with a Platform II Micromass System.

TEM.

Logarithmic-phase cells in BHI broth were treated at 37°C with different amounts of purified AS-48, sufficient to induce lysis (0.1 μg/ml for 2 h or 3 μg/ml for 10 min), and then prefixed with glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for 1 h and embedded in Spurr’s resin. Embedded cells were sectioned and mounted on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed under a Zeiss 902 electron microscope.

For morphology examination of the adapted cells by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), a culture of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 plus 0.075 μg of AS-48 per ml was incubated for 24 h to allow the development and enrichment of adapted cells, and then an aliquot was removed to be processed for TEM in a similar way to that described above. Aliquots of the remaining culture were transferred to fresh BHI medium without AS-48, incubated for an additional 24 h, transferred to two tubes containing BHI medium, and incubated for 2 h. Then AS-48 (3 μg/ml) was added to one of these tubes. After 10 min, both the control and the culture plus AS-48 were prefixed with glutaraldehyde and processed for TEM as described above.

RESULTS

Antilisterial spectrum of AS-48.

Purified AS-48 samples inhibited all strains of Listeria spp. tested (Table 1). L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii were the most sensitive of those assayed. The MIC for these strains was 0.1 μg of protein/ml. This corresponded to a specific activity of 7.6 AU/μg of protein, which was much higher than that shown against the indicator strain E. faecalis S-47 (1.4 AU/μg).

Biological activity of AS-48 against L. monocytogenes CECT 4032.

Addition of AS-48 to exponentially growing cultures of listeriae at 37°C caused a decay in turbidity due to cell lysis (Fig. 1A). Simultaneously, the number of viable cells decreased rapidly after AS-48 addition (Fig. 1B). Both bactericidal and bacteriolytic effects were proportional to the amount of AS-48 added (final concentrations, 0.06 to 0.12 μg/ml). At 37°C the minimal AS-48 concentration needed to cause total lysis of cultures within the first 3 h was 0.06 μg/ml for an initial cell number of 108 CFU/ml; this was similar to the findings for the other three L. monocytogenes strains tested (CECT 911, CECT 932, and CECT 935 [data not shown]). Nevertheless, the cultures recovered and experienced normal growth after 24 h of incubation with AS-48 (data not shown). These results were surprising, since the estimated number of viable cells after 2 to 3 h incubation with bacteriocin concentrations above 0.06 μg/ml was always less than 10 CFU/ml. Culture recovery was observed after 24 h of incubation with bacteriocin up to a concentration of 0.08 μg/ml. When higher concentrations (0.1 μg/ml or above) were used, no further growth of cultures was observed even when the incubation was prolonged for 4 days. According to these data, we defined the MIC as the minimal concentration able to cause cell lysis and to avoid culture recovery after 24 h of incubation. The MIC for L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 was 0.1 μg/ml under our experimental conditions (for an initial cell concentration of 108/ml).

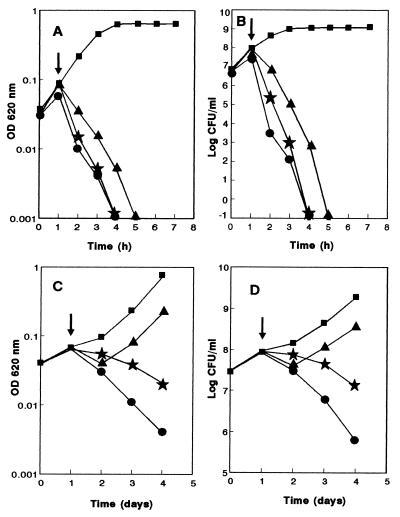

FIG. 1.

Antimicrobial effects of AS-48 on exponential-phase cultures of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032. Cultures were incubated at 37°C (A and B) with AS-48 concentrations of 0.06 (▴), 0.08 (★), or 0.12 (•) μg/ml. Cultures growing at 6°C (C and D) were treated with AS-48 at 0.1 (▴), 0.2 (★), or 2 (•) μg/ml. Controls are also shown (■). The arrows mark the moment of antibiotic addition. The optical density (OD) at 620 nm (A and C) and the number of viable cells (B and D) were determined at regular intervals.

The antimicrobial effect of AS-48 on L. monocytogenes was much lower when the incubation temperature was 6°C. At this temperature, a final concentration of AS-48 of 2 μg/ml was not sufficient to produce total lysis and loss of cell viability after 3 h incubation (Fig. 1C and D). In a separate experiment, aliquots (ca. 2 × 107 CFU) of an exponential-phase culture of listeriae were spread on plates of BHA containing increasing concentrations of AS-48 (from 0.05 to 5 μg/ml) and incubated at 6°C. After 20 days of incubation, abundant growth was observed in plates containing AS-48 concentrations of 1 μg/ml or lower but no colonies were found in plates containing 2.5 μg/ml or higher.

Influence of AS-48 on the cell bioenergetic parameters.

Addition of increasing concentrations of AS-48 to energized cells of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 equally dissipated the cell pH gradient (ΔpH) and the membrane electrical potential (Δψ) and hence the total PMF in a concentration-dependent manner. The membrane electrical potential was reduced to 43% of its initial value after 30 min of incubation with 0.5 μg of AS-48 per ml, and the pH gradient was completely depleted by 1 μg/ml. Given the higher cell concentrations used in the experiments, these data are consistent with the small amounts of AS-48 required to induce cell death in exponential-phase cultures of this strain.

Cocultivation of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and the AS-48-producing strain E. faecalis A-48-32.

When cultures of E. faecalis A-48-32 (approximately 105 CFU/ml) were incubated in BHI-PB with several listeria concentrations (approximately 103, 104, and 105 CFU/ml) at 6, 15, and 37°C, different antagonistic interactions were observed depending on the enterococcus-to-listeria ratio as well as on the temperature of incubation.

When the incubation temperature was 37°C and the initial cell ratio was approximately 100, the number of viable listeriae fell drastically to zero after 3 h of cocultivation (Fig. 2A). The decrease in the number of cells coincided with the moment in which AS-48 was detected in cell-free supernatants (Fig. 2A). Growth of the listeriae was not affected by cultivation with the AS-48-nonproducing mutant E. faecalis S-48-47 under the same conditions (data not shown). Moreover, growth of the producer enterococcal strain did not seem to be influenced by the presence of the listeria under all circumstances tested. When the initial enterococcus-to-listeria ratio was approximately 10, the decrease in the number of viable listeriae also coincided with detection of AS-48 in cell-free supernatants (Fig. 2B). In this case, however, a much longer cocultivation period (14 h at 37°C) was required to suppress the listerial population completely. When the initial ratio was approximately 1, the antagonistic effect was detected much later (after 8 h of incubation at 37°C) and no viable listeriae were detected after 14 h of incubation. However, a growing population of bacteriocin-adapted listeriae arose after 18 h of incubation, even though the levels of AS-48 in cell-free supernatants remained stable (Fig. 3C).

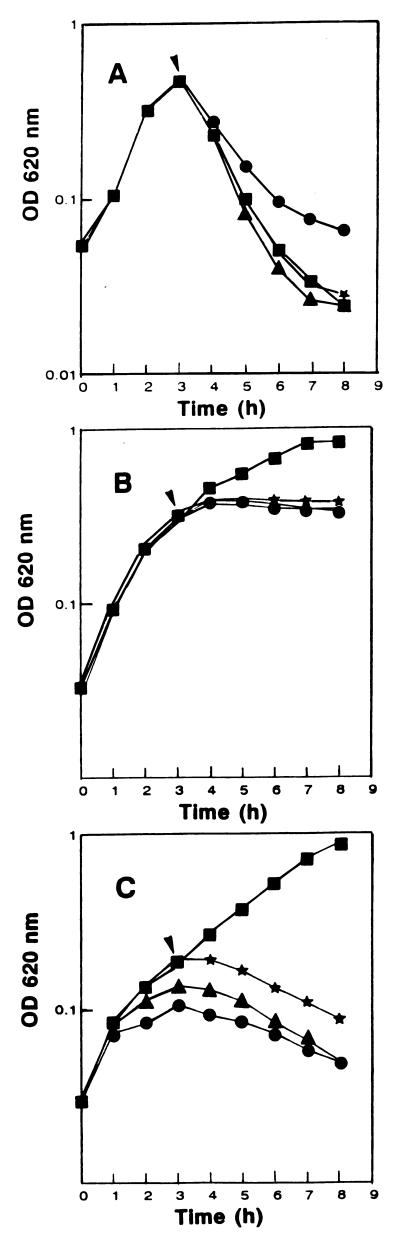

FIG. 2.

Cocultivation of the AS-48 producer strain E. faecalis A-48-32 and L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 in BHI broth at 37°C (A through C) or 15°C (D). The initial enterococcus-to-listeria ratios were 100:1 (A), 10:1 (B and D), and 1:1 (C). At regular intervals, the number of viable enterococci (▴) and listeriae (■), as well as the amount of AS-48 in cell-free supernatants (•), were determined.

FIG. 3.

Combined effects of cell wall-acting antibiotics and AS-48 on the wild-type sensitive strain L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 (A) and on the AS48ad strain previously grown without AS-48 (B) or with 0.1 μg of AS-48 per ml (C). The antibiotics ampicillin (▴), d-cycloserine (★), or vancomycin (•) were added together with AS-48 (0.1 μg/ml) at the moment marked by the arrowheads. Controls are also shown (■). OD 620 nm, optical density at 620 nm.

Cocultivation at 15°C was carried out with an enterococcus-to-listeria ratio of 10. Under these conditions, the number of viable listeriae decreased much later (after 25 h of cocultivation), probably because of the lower growth rate of the enterococci and the delay in accumulation of sufficient levels of AS-48 to inhibit Listeria (Fig. 2D). In this case, AS-48 in cell-free supernatants could not be detected before 30 h of incubation. In spite of the delay in AS-48 production, the number of viable listeriae decreased to zero and remained there even 70 h later.

Cocultivation at 6°C was not successful even at the highest ratios used, i.e., 100. Under these conditions, no inhibition of Listeria was detected, even after prolonged incubation for 7 days (data not shown). No growth of enterococci was observed at this temperature, and no bacteriocin activity could be detected in cell-free supernatants either.

Selection of AS48ad L. monocytogenes.

Upon prolonged incubation with AS-48 concentrations below the MIC, adapted cultures could be selected which now were able to grow in the presence of higher antibiotic concentrations. We selected an AS48ad strain from liquid cultures incubated at 37°C for 48 h with 0.075 μg of AS-48 per ml. Growth of this strain was not affected by 0.1 μg/ml, although it was completely inhibited by higher antibiotic concentrations. The MIC for this strain was 0.5 μg/ml, and at this concentration no growth was observed even after 5 days of incubation. Therefore, we considered this to be an adaptation rather than true resistance. The AS48ad strain underwent slower growth (both with and without AS-48) than the wild-type strain, and the time required to reach its stationary phase was 6 h (versus 4 h for the wild-type strain). This strain and the wild-type strain showed identical responses to tests with the API-Listeria system.

Resistance to AS-48 was followed by subcultivation with and without AS-48. As expected, the adapted strain remained so after repeated cultivation in presence of AS-48. Nevertheless, resistance to AS-48 was progressively lost in the absence of the antibiotic. After 11 steps of subcultivation, the AS48ad strain could be inhibited by 0.1 μg of AS-48 per ml, as shown by the total lysis of cultures observed after 4 h of treatment.

Effect of cell wall-acting antibiotics on AS-48-sensitive and -adapted L. monocytogenes CECT 4032.

The effects of ampicillin, d-cycloserine, and vancomycin on exponentially growing listeriae (sensitive or adapted) in the absence of AS-48 were almost identical, and no differences were found whether the AS48ad strain was previously grown in the presence or absence of AS-48. In all cases, addition of cell wall-acting antibiotics caused arrest of cell growth and the optical density of the cultures remained constant (results not shown).

Simultaneous addition of cell wall-acting antibiotics and AS-48 (0.1 μg/ml) induced rapid lysis of exponential-phase sensitive cells (Fig. 3A). However, addition of the same antibiotic combinations to AS-48 adapted cells, previously grown with AS-48, had no bacteriolytic effect, and the optical density of the cultures remained constant as a result of the inhibition of cell wall synthesis (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, addition of the different antibiotic combinations to exponential AS48ad cells for which the preinoculum had been grown without AS-48 caused a variable degree of cell lysis (Fig. 3C). Since cell wall-acting antibiotics were unable to induce cell lysis, this effect should be attributed to a partial loss of the AS48ad trait during growth of the preinoculum without AS-48.

Action of muramidases on AS-48-sensitive and -adapted L. monocytogenes.

To test if AS-48 adaptation induced any change in sensitivity to lytic enzymes such as muramidases, both the wild-type and the AS48ad strains were incubated with lysozyme and mutanolysin and then plated in the absence of an osmotic stabilizer. After a 1-h incubation, the viability of adapted cells (grown without AS-48) was reduced by 1.65 log units, compared with 3.3 log units in wild-type cells, indicating that adapted cells were more resistant. Similar results were obtained after 3 h of incubation (7.8 and 9.2 log units of reduction, respectively). Moreover, when AS48ad cells were previously grown in the presence of AS-48, they showed a still higher resistance to lysozyme (0.9 or 2.0 log units of reduction for 1 or 3 h of lysozyme treatment, respectively).

Resistance to mutanolysin was clearly induced by AS-48 adaptation. In this case, the viability loss of AS48ad cells after 3 h of incubation with the enzyme was 0.5 log unit, as opposed to the 2.7-log-unit reduction obtained for the wild-type strain. Adapted cells previously grown with AS-48 showed a similar degree of resistance (0.6 log unit of viability loss).

Nisin resistance of the AS48ad strain.

Exponential-phase cultures of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and strain AS48ad were treated with nisin (Nisaplin) in a range of concentrations from 2 to 100 IU/ml (Fig. 4). Growth of the wild-type strain was inhibited completely by nisin concentrations of 20 IU/ml or higher, causing total lysis within 4 h. In contrast, the AS48ad strain was able to resume normal growth after a 2-h incubation with 20 IU of nisin per ml, and it was notably much more resistant to higher nisin concentrations (Fig. 4B). The AS48ad strain was able to resume exponential growth after 4 to 5 h of treatment with 100 IU of nisin per ml.

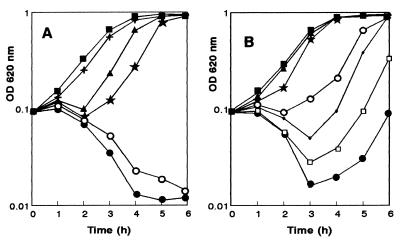

FIG. 4.

Sensitivity to nisin of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 (A) and the AS48ad strain (B). Cells were grown in BHI broth to an optical density at 620 nm (OD 620 nm) and different Nisin concentrations were added (at time zero in the graphs): 2 (+), 5 (▴), 10 (★), 20 (○), 40 (•), 80 (□), and 100 (•) IU/ml. Controls are also shown (■).

Effect of AS-48 on protoplasts from L. monocytogenes.

To test the role of the cytoplasmic membrane in AS-48 adaptation, protoplast suspensions (ca. 4 × 108 CFU/ml) of sensitive and adapted strains were incubated with increasing AS-48 concentrations (Fig. 5). As expected, the optical density of protoplast suspensions and the number of viable protoplasts of the wild-type strain decreased progressively with time and AS-48 concentration. These effects were much lower for the AS48ad strain. In this case, the protoplast viability was only reduced by 0.88 log unit (from 3.7 × 108 to 5.3 × 107 CFU/ml) under the best conditions (0.4 μg/ml of AS-48), as opposed to 3.7 log units (from 4.8 × 108 to 8 × 104 CFU/ml) for the wild-type strain.

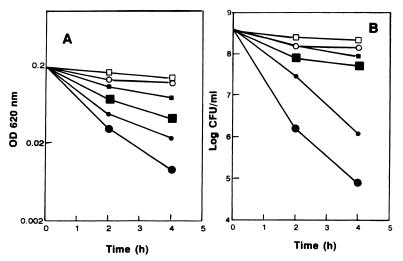

FIG. 5.

Effect of AS-48 on protoplasts of the sensitive strain L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and on the AS48ad strain. The optical density at 620 nm (OD 620 nm) (A) and the number of viable cells (B) were determined at regular intervals of incubation at 37°C. AS-48 was added to protoplast suspensions of the wild-type strain at 0 (○), 0.2 (•), or 0.4 (•) μg/ml. The same concentrations of 0 (□), 0.2 (▪), and 0.4 (■) μg/ml were also tested on the AS48ad strain.

Analysis of the fatty acid composition.

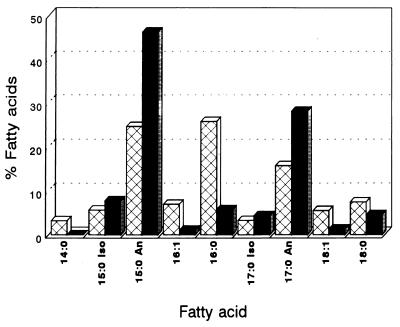

The quantitative analysis of the fatty acid composition of the wild-type L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and strain AS48ad revealed notable differences (Fig. 6). Strain AS48ad showed a comparatively higher proportion of branched C15 and C17 anteiso fatty acids and a much lower proportion of saturated C16 fatty acids. The content in C16:1 and C18:1 fatty acids was also lower for the AS48ad strain.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the fatty acid composition of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 (hatched bars) and the AS48ad strain (solid bars). The fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. An, anteiso-branched fatty acids; i, iso-branched fatty acids.

TEM.

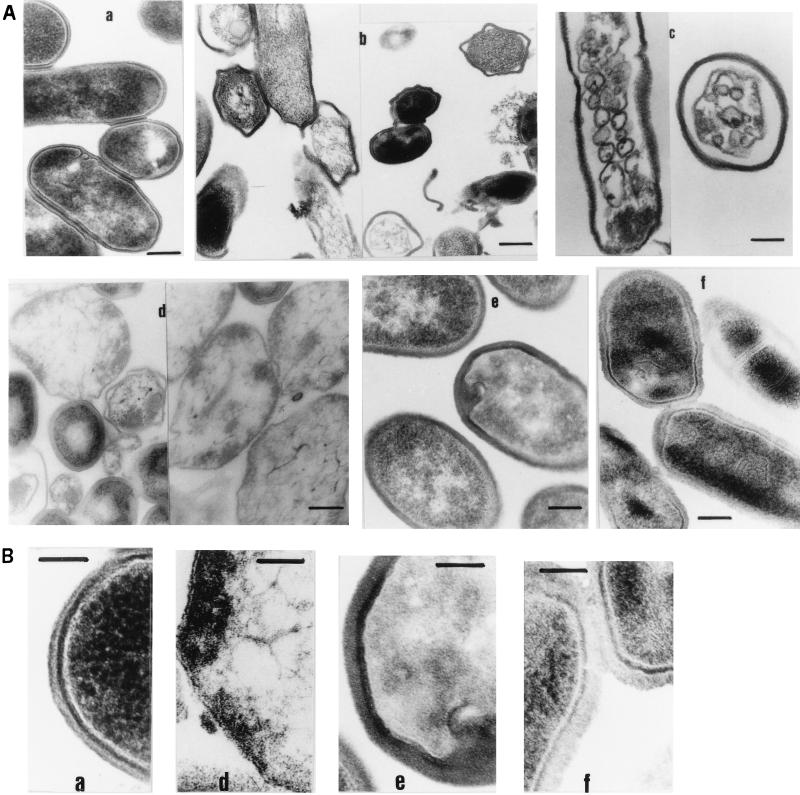

L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and AS48ad were treated at 37°C with purified AS-48 in sufficient amounts to induce lysis (0.06 μg/ml for 2 h, and 3 μg/ml for 10 min) and examined by TEM. The effects of AS-48 on sensitive cells could be easily detected even at low antibiotic concentrations (Fig. 7A, panel b). Treated cells showed a marked retraction of the cell body, with visible separation from the cell wall in some points. The cytoplasm of treated cells had a much lower density (probably due to the loss of solutes). Empty cells (ghosts) were also observed, as well as broken cell walls. A short treatment with a high peptide concentration (a 10-min incubation with 3 μg/ml) caused complete disorganization of the cell membrane, with formation of small vesicles (panel c).

FIG. 7.

TEM of cells of L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and the AS48ad strain. (A) Exponential-phase cells (a) were treated with 0.1 μg/ml of AS-48 for 2 h (b) or 3 μg/ml for 10 min (c). AS48ad cells were obtained by culturing the wild-type strain for 24 h in the presence of 0.076 μg/ml of AS-48 (d). The AS48ad cells were grown for an additional 24 h without AS-48 and incubated in fresh medium for 2 h (e); then AS-48 (3 μg/ml) was added for 10 min. (f). Bars, 150 nm in panels a and d, 200 nm in panel b, and 120 nm in panels c, e, and f. (B) Magnification (×100,000 total) of preparations a, d, e, and f described in panel A. Bar, 100 nm.

TEM examination of AS48ad listerial cells obtained after incubation of the wild-type sensitive strain in the presence of 0.075 μg of AS-48 per ml for 48 h showed a surprisingly unusual morphology. The majority of the cell population consisted of globous forms with ill-defined cell envelopes resembling sphaeroplasts or cell ghosts (Fig. 7, panels d). Since these preparations came from cultures undergoing a marked drop in A620 and for which no viable cells were obtained after plating, we must suppose that these are injured cells able to repair their damages and multiply in spite of their obviously anomalous cell wall. Further incubation of this type of cells in fresh BHI broth for 24 h allowed them to recover the typical morphology of intact Listeria, although their cell wall appeared thicker and more relaxed (Fig. 7, panels e). When AS48ad cells (after 24 h of recovery in BHI plus an additional 2 h of incubation in fresh broth to allow the onset of exponential growth) were incubated with high AS-48 concentrations (3 μg/ml) for 10 min, they showed a markedly relaxed cell wall. Interestingly, they also showed several intracytoplasmic membranous structures that were randomly arrayed but markedly different from those shown by the sensitive strain upon the same AS-48 treatment (Fig. 7, panels f).

DISCUSSION

The peptide AS-48 is highly active against the different strains of Listeria tested, which are far more sensitive to AS-48 than the rest of the gram-positive bacteria reported previously (8). In this respect, AS-48 shows its highest activity against L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii. The bactericidal effect of AS-48 on Listeria is believed to occur through interaction with the cytoplasmic membrane, causing depletion not only of the electrical potential, as was shown previously for enterococci (10), but also of the pH gradient. These effects are also followed by disorganization of the bacterial cell wall (probably mediated by autolysis induction as in E. faecalis [9]), and are common to other antagonistic cationic peptides (26).

Since L. monocytogenes is a psychrotrophic bacterium, we wanted to test the effect of AS-48 at low temperature. In this respect, a short treatment of liquid cultures at 6°C with AS-48 (even at high concentrations) followed by dilution and plating in media without AS-48 at 37°C was much less effective than a similar treatment at 37°C. Nevertheless, the growth of Listeria on solid media was completely inhibited by much lower AS-48 concentrations (2.5 μg/ml). Therefore, we must conclude that AS-48 can inhibit the growth of Listeria at low temperature efficiently, although a prolonged incubation with bacteriocin may be required. In this respect, our results differ markedly from those obtained by Maisnier-Patin et al. (15) for enterococcin EFS2 (a cyclic peptide whose reported features are almost identical to those of AS-48), who found almost no activity at 15°C on L. innocua. Loss of EFS2 activity at low temperature was attributed to a lower solubility of the bacteriocin or to the formation of inactive aggregates (15). This does not seem to be the case for AS-48, which is highly soluble at low temperature as well. Formation of aggregates has been also demonstrated for AS-48, but the different multimers do have antimicrobial activity (1). Additional data supporting the antimicrobial activity of AS-48 at low temperature come from cocultivation experiments carried out with the producer strain E. faecalis A-48-32 at 15°C as we shall discuss further on.

Cocultivation of E. faecalis A-48-32 with L. monocytogenes under various conditions indicates that the production of AS-48 was not adversely affected by the presence of Listeria. Under optimal conditions for growth of enterococci, AS-48 was produced in sufficient amounts to suppress the listeriae present in the cocultures when the initial populations (in CFU per milliliter) were set at 105 enterococci per 104 listeriae. At higher concentrations of listerial cells (e.g., 105 CFU/ml) the amount of AS-48 produced was still sufficient to induce cell death, but it allowed the development of an AS-48-adapted population after prolonged incubation. Cocultivation at a lower temperature (15°C) was less efficient, since the time required to suppress the initial population of listeriae was 52 h for a starting enterococcus-to-listeria ratio of 10. The main cause of this delay was the lower growth rate of enterococci (generation time [g] = 100 min at 15°C versus 37 min at 37°C) and hence the delayed production of AS-48, which was not detected in culture supernatants until later than 30 h of incubation. In spite of being produced much later, AS-48 reached a similar concentration to that in broths cultured at 37°C and it acted efficiently on Listeria, suppressing 5.5 × 106 CFU/ml within 28 h. Finally, we must conclude that cocultivation experiments at 6°C were unsuccessful because enterococci were unable to grow at this temperature and therefore no AS-48 was produced.

Another relevant aspect of this work is the apparently high sensitivity of Listeria to AS-48 as well as the selection of AS-48-adapted listeriae. The bacteriocin concentrations required to induce bacteriolysis of L. monocytogenes were about 50 times lower than those required to induce a similar effect on other sensitive bacteria such as Enterococcus or Bacillus (8). Nevertheless, we found that listerial cultures were able to recover after being damaged severely by bacteriocin concentrations within the range of 0.06 to 0.1 μg/ml (but not with higher bacteriocin concentrations). Those cells were now able to grow in the presence of 0.1 μg/ml but could still be inhibited very efficiently by slightly higher bacteriocin concentrations (e.g., 0.5 μg/ml), although these concentrations were still lower than those required to inhibit other gram-positive bacteria. Therefore, we called them AS-48-adapted cells rather than AS-48-resistant cells.

Both L. monocytogenes CECT 4032 and the AS48ad strain were studied for sensitivity to cell wall-acting antibiotics and enzymes. We found no differences between the strains when we used cell wall-acting antibiotics alone or in combination with AS-48. Nevertheless, AS-48-adapted cells were markedly more resistant to lysozyme and mutanolysin than the wild-type strain. These data agree well with previous observations on nisin resistance, which have been attributed at least in part to changes in the cell wall composition (4, 15). To test the role of the cell wall and the cytoplasmic membrane on AS-48 resistance, we used protoplasts of the sensitive and adapted strains. We found that protoplasts from AS48ad cells were significantly less sensitive to AS-48 than the wild-type strain, indicating that the cytoplasmic membrane plays a fundamental role in adaptation to AS-48. Further analysis of the fatty acid composition revealed substantial differences in adapted cells, which showed a much higher proportion of branched fatty acids as well as a higher C15:0 An-to-C17:0 An ratio. These changes tend to increase the fluidity of the cytoplasmic membrane and are just opposite of those described for Nisr strains (18, 30), whose fatty acid composition predicts a more rigid cell membrane. Surprisingly, the AS48ad strain showed a remarkable cross-resistance to nisin, which proved to be much less effective on this strain than was AS-48.

AS-48-adapted cells showed a distinctive aspect when observed by electron microscopy. Their cell wall was thicker, although it seemed to be less dense than that of sensitive cells. Altogether, these data indicate that resistance (or adaptation) of L. monocytogenes is a complex phenotype involving both the bacterial cell wall and the cytoplasmic membrane. In this respect, the AS48ad phenotype resembles nisin resistance (3), although the detailed mechanisms are expected to be different.

Development of bacteriocin resistance or adaptation, particularly among Listeria, is a drawback to the extensive use of bacteriocins in food preservation. In this respect, the high sensitivity of Listeria to AS-48 (in the range of nanograms per milliliter) is a clear advantage, because no adapted cells will develop when AS-48 is used at the higher concentrations needed to inhibit other gram-positive bacteria (in the range of micrograms per milliliter). The usefulness of AS-48 against Listeria seems also to be limited because these bacteria are more resistant at low temperature. We should stress, however, that the cell concentrations used in our experiments (around 108 CFU/ml) are much higher than those expected to occur in contaminated foods. Therefore, the usefulness of AS-48 to prevent the proliferation of food-borne listeria should be tested in model food systems to determine the influence of the various parameters involved (e.g., initial cell concentration, incubation temperature, pH of the sample, and food composition).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the CICYT (BIO95-0466) from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

We thank Aplin and Barrett Ltd. for the supply of Nisaplin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abriouel, H., E. Valdivia, A. Gálvez, and M. Maqueda. Submitted for publication.

- 1a.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coppola S, Parente E, Dumontet S, Peccerella A. The microflora of natural whey cultures utilized as starters in the manufacture of Mozzarella cheese from water-buffalo milk. Lait. 1988;68:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crandall A D, Montville T J. Nisin resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302 is a complex phenotype. J Bacteriol. 1998;64:231–237. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.231-237.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies E A, Falahee M B, Adams M R. Involvement of the cell envelope of Listeria monocytogenes in the acquisition of nisin resistance. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb04491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration. Nisin preparation: affirmation of GRAS status as a direct human food ingredient. Fed Regist. 1988;53:11247. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gálvez A, Maqueda M, Valdivia E, Quesada A, Montoya E. Characterization and partial purification of a broad spectrum antibiotic AS-48 produced by Streptococcus faecalis. Can J Microbiol. 1986;32:765–771. doi: 10.1139/m86-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gálvez A, Giménez-Gallego G, Maqueda M, Valdivia E. Purification and amino-acid composition of peptide antibiotic AS-48 produced by Streptococcus (Enterococcus) faecalis subsp. liquefaciens S-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:437–441. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gálvez A, Maqueda M, Martínez-Bueno M, Valdivia E. Bactericidal and bacteriolytic action of peptide antibiotic AS-48 against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and other organisms. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gálvez A, Valdivia E, Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M. Induction of autolysis in Enterococcus faecalis S-47 by peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gálvez A, Maqueda M, Martínez-Bueno M, Valdivia E. Permeation of bacterial cells, permeation of cytoplasmic and artificial membrane vesicles, and channel formation on lipid bilayers by peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:886–892. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.886-892.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatti M, Fornasari E, Giraffa G, Carminati D, Neviani E. Gli enterococchi nei formaggi italiani: attività biochemica e significato tecnologico. Ind Latte. 1994;30:11–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giraffa G, Neviani E, Torri Tarelli G. Antilisterial activity by enterococci in a model predicting the temperature evolution of Taleggio, an Italian soft cheese. J Dairy Sci. 1994;77:1176–1180. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh B K, Murray R G E. Fine structure of Listeria monocytogenes in relation to ptotoplasts formation. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:411–426. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.1.411-426.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashket E R, Blanchard A G, Metzger W C. Proton motive force during growth of Streptococcus lactis cells. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:128–134. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.128-134.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maisnier-Patin S, Forni E, Richard J. Purification, partial characterization and mode of action of enterococcin EFS2, an antilisterial bacteriocin produced by a strain of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;30:255–270. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)00950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Bueno M, Gálvez A, Maqueda M, Valdivia E. Genetic stability of the antagonistic character of Enterococcus faecalis ssp. liquefaciens and the detection of a new inhibitory bacteriocin-like substance. Folia Microbiol. 1990;35:113–123. doi: 10.1007/BF02820767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M, Gálvez A, Samyn B, Van Beeumen J, Coyette J, Valdivia E. Determination of the gene sequence and the molecular structure of the enterococcal peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6334–6339. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6334-6339.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzotta A S, Montville T J. Nisin induces changes in membrane fatty acid composition of Listeria monocytogenes nisin-resistant strains at 10°C and 30°C. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1997.tb03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKay A M. Antimicrobial activity of Enterococcus faecium against Listeria ssp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muriana P M. Bacteriocins for control of Listeria ssp. in food. J Food Prot Suppl. 1996;1996:54–63. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.13.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nettles C G, Barefoot S F. Biochemical and genetic characteristics of bacteriocins of food-associated lactic acid bacteria. J Food Prot. 1993;56:338–356. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parente E, Hill C. Characterization of enterococcin 1146, a bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium inhibitory to Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Prot. 1992;55:497–502. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piard J, Desmazeaud M. Inhibiting factor produced by lactic acid bacteria. 2. Bacteriocins and other antibacterial substances. Lait. 1992;72:113–142. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raines L J, Moss C W, Farshtchi D, Pittman B. Fatty acids of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:2175–2177. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.6.2175-2177.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rottenberg H. The measurement of membrane potential and pH in cells, organelles and vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 1979;55:547–569. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)55066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahl H G. Bactericidal cationic peptides involved in bacterial antagonism and host defense. Microbiol Sci. 1985;2:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smibert R M, Krieg N R. Phenotypic characterization. In: Gerdhardt P, Murray R G E, Woods W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. p. 634. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tagg J R, McGiven A R. Assay system for bacteriocins. Appl Microbiol. 1971;21:943. doi: 10.1128/am.21.5.943-943.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanderbergh P A. Lactic acid bacteria, their metabolic products and interference with microbial growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villani F, Salzano G, Sorrentino E, Pepe O, Marino P, Coppola S. Enterocin 226 NWC, a bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecalis 226, active against Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb05142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villani F, Salzano G, Sorrentino E, Pepe O, Marino P, Coppola S. Enterocin 226 NWC, a bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecalis 226, active against Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb05142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilimowska-Pelc A, Olichwier Z, Malicka-Blaszkiewicz M, Mejbaum-Katzenellenbogen W. The use of gel-filtration for the isolation of pure nisin from commercial products. Acta Microbiol Pol Ser A. 1976;8:71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkowski K, Ludescher R D, Montville T J. Physicochemical characterization of the nisin-membrane interaction with liposomes derived from Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1966;62:323–327. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.323-327.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]