Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of increasing estrogen doses during hormone therapy frozen embryo transfer (HT-FET) cycles on endometrial thickness and success rates compared to patients who received fixed estrogen dose.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study from a university-based fertility clinic during the years 2008–2021. We compared two groups: the fixed-dose group (i.e., received 6 mg estradiol dose daily until embryo transfer) and the increased-dose group (i.e., the initial estradiol dose was 6 mg daily, and was increased during the cycle). Primary outcome: clinical pregnancy rate.

Results

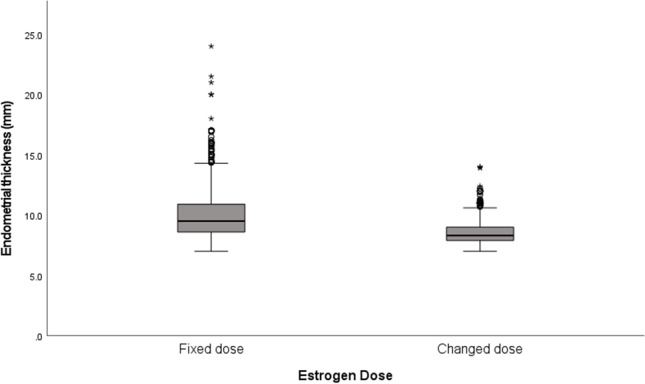

The study included 5452 cycles of HT-FET: 4774 cycles in the fixed-dose group and 678 cycles in the increased-dose group. Ultrasound scan on days 2–3 of the cycle showed endometrial thickness slightly different between the two groups (4.2 mm in the fixed-dose and 4.0 mm in the increased-dose group, P = 0.003). The total estrogen dose was higher, and the treatment duration was longer in the increased than the fixed-dose group (122 mg vs. 66 mg and 17 days vs. 11 days, respectively; P < 0.001). The last ultrasound scan done before the addition of progesterone showed that the endometrial thickness was significantly thicker in the fixed than the increased-dose group (9.5 mm vs. 8.3 mm; P < 0.001). The clinical pregnancy rates were 35.8% in the increased-group vs. 34.1% in the fixed-dose group; P = 0.401.

Conclusions

The increased-dose group had thinner endometrium despite the higher doses of estrogen and longer treatment duration than the fixed-dose group. However, the pregnancy rates were similar between the two groups.

Keywords: Embryo transfer, Frozen embryo, Estrogen, IVF, Pregnancy, Outcome

Introduction

In the era of assisted reproductive technology (ART), frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) cycles have evolved as one of the most important treatments and have increased substantially worldwide in the last two decades [1, 2]. In Japan, for example, most of the ART babies that were born in recent years were conceived in frozen rather than fresh cycles [3]. Embryo quality and endometrial receptivity are the two main factors associated with successful embryo transfer cycles [4]. Cycles in which the embryo was tested for aneuploidy show a 45–60% ongoing pregnancy rate if an euploid embryo was transferred [5–7]. Therefore, an effort is made to find other factors which would contribute to success rates, especially by optimizing endometrial receptivity [4]. The endometrial preparation and synchrony could be achieved in two main ways: natural cycles using spontaneous or triggered ovulation and cycles in which sequential estrogen and progesterone are used to artificially prepare the endometrium (hormone therapy (HT-FET cycles)). Other proposed regimens include the use of gonadotropins, letrozole, or GnRH agonist, sometimes in concomitant with the aforesaid regimens [8]. Many studies have tried to evaluate which one of these would be the best regimen for FET, with conflicting results [8–11]. Other studies have investigated what is the optimal endometrial thickness in fresh and frozen cycles [12–15]. However, almost none evaluated the effect of different doses, and changes, of estrogen in HT-FET cycles on success rates. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate the effect of increasing estrogen dose and total estrogen dose during HT-FET cycles on success rates.

Materials and methods

Our retrospective study included all HT-FET cycles that were conducted in a university-based fertility clinic of a tertiary hospital in Quebec, Canada, between the years 2008 and 2021. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from McGill University Health Centre Ethics Committee for Clinical Research (number 2021–7634). Data were obtained from the electronic medical records of the fertility clinic. First, all HT-FET cycles were identified. Subsequently, only cycles that started with an estrogen daily dose of 6 mg were included. Cycles in which the starting dose was higher or lower than 6 mg daily were excluded from the study in order to prevent any confounding effect. The HT-FET cycles were then divided into two groups: the fixed-dose group (i.e., those who had started and ended the cycle with the same dose [6 mg daily micronized estradiol (17β-estradiol)]) and the increased-dose group (i.e., those who had increased micronized estradiol dose during the cycle). Cycles with estrogen patches, letrozole, gonadotropins administration, or GnRH agonist were excluded from the study.

Variables collected included patient age at oocyte retrieval, the reason for ART, number of previous frozen embryo transfers, number of embryos transferred, developmental stage at cryopreservation (cleavage stage or blastocysts), baseline endometrial thickness on days 2–3 of the cycle (in millimeters), endometrial thickness on the last ultrasound scan done before the addition of progesterone, treatment duration in days, and total estradiol dose per each cycle. The primary outcome was the rate of clinical pregnancy, which was defined as a gestational sac on transvaginal ultrasound (Voluson S8, General Electric Corporation, USA) done between weeks 6 and 8.

Endometrial thickness was measured by using transvaginal ultrasound. First, it was measured on days 2–3 of the menstrual cycle. If no cysts, dominant follicle, or intrauterine pathology were noted, the patient could start her treatment. The endometrial preparation was achieved by administration of estradiol tablets, starting with 6 mg daily and ending with 6–24 mg daily. The tablets were given orally in the fixed group in most of the cases, and orally, transvaginally, or a combination of the two methods in the increased group. Supplementation with estrogen lasted for a maximum of 45 days, with only a few patients who received estrogen for less than 7 days. The second transvaginal ultrasound was performed on days 10–12 of the cycle. If the endometrial thickness has reached 7 mm or more, progesterone was added, and embryo transfer was planned. Embryos were obtained from either in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and they were thawed after being first cryopreserved by vitrification. We have included cycles in which the embryos were tested by preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). If the endometrium was thinner than 7 mm, the estrogen dose was increased to an extent according to the patient history and to the clinician’s decision, and another scan was set, until the desired thickness was achieved.

Cycle characteristics and outcome were compared between the fixed-dose and the increased-dose groups using chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and t-tests or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. We also examined the association between endometrial thickness and clinical pregnancy rates. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp.).

Results

Between 2008 and 2021, a total of 6249 HT-FET cycles were identified and 5452 cycles with a starting dose of 6 mg estradiol a day were included in the analysis. More than 50% of the cycles were the first cycles, without preceding any FET cycles. There were 4774 cycles (87%) in the fixed-dose group and 678 cycles (13%) in the increased-dose group. The two groups had similar baseline characteristics, including female age at oocyte retrieval day, embryo stage, and endometrial thickness at baseline (Table 1). Interestingly, the diagnosis of a male factor was less common in the increased-dose group compared to the fixed-dose group (33.2% vs 37.7%, P = 0.023). As expected, the treatment duration and the total estrogen dose were higher in the increased group: they needed a longer treatment duration (a median of 17 vs. 11 days, P < 0.001) and a higher total dose of estrogen (a median of 122 mg vs. 66 mg, P < 0.001) compared to the fixed group (Table 2). Although there was a statistically significant difference in the endometrial thickness at the end (i.e., before adding progesterone) between the two groups (9.5 mm median in the fixed-dose group and 8.3 mm median in the increased-dose group, P < 0.001), the clinical pregnancy rates were comparable (Table 2). Figure 1 displays the endometrial thickness before adding progesterone by estrogen dose groups.

Table 1.

Distributions of patients’ characteristics by estrogen dose change

| Dose-fixed N = 4774 |

Dose-increased N = 678 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients’ characteristics | |||

| Age at oocyte retrieval (median (IQR)) | 35.0 (32.0, 38.0) | 35 (32.0, 38.0) | 0.580 |

| First frozen cycle, n (%) | 2516 (52.7%) | 387 (57.1%) | 0.033 |

| Non-first frozen cycle treated with HRT, n (%) | 2231 (46.7%) | 286 (42.2%) | 0.026 |

| Indication for IVF | |||

| Male factor, n (%) | 1800 (37.7%) | 225 (33.2%) | 0.023 |

| Female factor | |||

| • None (cases in which no diagnosis is mentioned for the couple) | 2455 (51.4%) | 341 (50.3%) | 0.816 |

| • Diminished ovarian reserve | 532.0 (11.1%) | 84 (12.4%) | |

| • Unexplained infertility | 1086 (22.7%) | 167 (24.6%) | |

| • Tubal factor | 437 (9.2%) | 55 (8.1%) | |

| • Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders | 142 (3.0%) | 16 (2.4%) | |

| • Oocyte recipient/surrogate carrier | 36 (0.8%) | 4 (0.6%) | |

| • Advanced maternal age | 37 (0.8%) | 6 (0.9%) | |

| • Fertility preservation (cancer) | 33 (0.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | |

| • Fertility preservation (social) | 16 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Endometrial thickness at baseline in mm (median (IQR)) | 4.2 (3.3, 5.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 0.003 |

IQR, interquartiles range

Table 2.

Comparison of endometrial thickness and pregnancy outcomes by estrogen dose change

| Missing | Dose-fixed N = 4774 |

Dose-increased N = 678 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen days (median (IQR)) | 0/0 | 11.0 (11.0, 12.0) | 17.0 (15, 20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total estrogen dose (median (IQR)) | 0/0 | 66.0 (66.0, 72.0) | 122.0 (106.0, 146.0) | < 0.001 |

| Endometrial thickness on the day of progesterone supplementation (median (IQR)) | 0/0 | 9.5 (8.6, 10.9) | 8.3 (7.9, 9.0) | < 0.001 |

| No. of embryos transferred | 112/17 | 0.830 | ||

| 1, n (%) | 3792 (81.3%) | 543 (82.1%) | ||

| 2, n (%) | 749 (16.1%) | 103 (15.6%) | ||

| More than 2, n (%) | 121 (2.6%) | 15 (2.3%) | ||

| Developmental stage at cryopreservation: | 331/43 | |||

| Cleavage stage (days 2–4), n (%) | 403 (9.0%) | 70 (11.0%) | 0.105 | |

| Blastocyst stage (day 5 or 6), n (%) | 4060 (91.0%) | 565 (89.0%) | ||

| Clinical pregnancy, n (%) | 545/61 | 1466 (34.1) | 221 (35.8) | 0.401 |

IQR, interquartiles range

Fig. 1.

Endometrial thickness before adding progesterone by estrogen dose groups

Discussion

Improving endometrial receptivity or timing of embryo transfer remains a great challenge and is considered a key factor in increasing success rates in frozen embryo transfer cycles [4]. The goal of our study was to investigate one aspect of a key point in frozen embryo transfer — the artificial preparation of the endometrium. Optimal preparation of the endometrium is measured by the way and to what extent it is getting thicker [16], to the triple line pattern formation [17], and recently to the change in the thickness after exposure to progesterone, also called compaction [18, 19]. We were looking for a possible association between increasing estrogen doses in the middle of a cycle and pregnancy rates. It was important to investigate this specific issue since mid-cycle estrogen dose adjustments often take place in clinical practice. We found that patients who needed increasing estrogen doses had longer treatment duration and higher total estrogen dose. However, they were able to reach a median endometrial thickness above 8 mm and to have comparable clinical pregnancy rates. In a large meta-analysis from 2014, an endometrial thickness ≤ 7 mm was related to a lower probability of pregnancy [13].

In addition to the thickness per se, we investigated how increasing the dose could affect outcomes. In 2016, Madero and colleagues investigated the effect of fixed and increased estrogen dose in fresh oocyte donation cycles and found no difference between the two groups in terms of clinical pregnancy rates and live birth rates [20]. However, the increased protocol was consisting of an administration of estrogen in a fixed time frame and doses (2 mg a day from days 1 through 7, and then 4 mg a day from days 8 to 12 and so on), whereas in our study, the estrogen dose was increased during the cycle according to individual’s endometrial thickness measurements. Following the increase in the estrogen dose, the patient’s response was monitored by repeated ultrasounds. Another adjustment of the dose was made if needed. Another difference is that in our study, we investigated only frozen embryo transfer, whereas in the aforementioned study, the embryos were fresh from either fresh or frozen oocyte or sperm. Despite the differences, both studies showed that the group who needed increased estrogen dose did not show reduced pregnancy rates.

Literature in the past has also investigated the role of treatment duration in HT-FET success rates. Estrogen supplementation longer than 40 days or shorter than 11 days was found to be associated with breakthrough bleeding and miscarriages, respectively [20]. Although increasing estrogen dose in our study was associated with a longer treatment duration, pregnancy rates were similar between the increased and fixed groups. This may be attributed to the fact that only 5 patients have exceeded 40 days of treatment (up to a maximum of 45 days).

There are several limitations to our study. Due to its retrospective nature, there may be unmeasured confounding variables. For example, mean estradiol levels of the two groups on the day of their last scan before starting progesterone could add additional information. However, this test is not performed routinely; therefore, this information is lacking. Route of estrogen administration was not equally distributed between the groups, since when the estrogen dose needs to be increased, the added estrogen is given vaginally in most of the cases, and this could potentially affect the results. Furthermore, cases where estrogen was increased may represent a group with a poorer prognosis, and the fact that one group required the change in dose reveals an inherited bias, although the outcomes were similar to the fixed-dose group. Another interesting question would be whether the increasing estrogen dose can affect obstetrical outcomes that are related to placentation. Due to the retrospective design, this information could not be retrieved, and may necessitate future studies that will investigate it. Another limitation is that ultrasound scan during the treatment was performed by multiple scanners, which may present an observer bias. Lastly, diagnosis of uterine factor such as prior surgeries was not available on the computerized database, and information regarding embryo grading and live birth rates were available for only part of the cycles; therefore, these variables were not included in our results. However, our results are reassuring in that even if the estrogen dose needs to be increased due to an inherent uterine factor, the outcomes are similar to the fixed group. Another strength of our study is being a large study to evaluate the effect of increasing estrogen in HT-FET cycles, and which to the best of our knowledge was not published before.

Conclusion

Increasing estrogen dose during HT-FET cycles is not associated with decreased pregnancy rates. Most patients did not exceed the maximum recommended treatment duration despite their need for a higher estrogen dose, and endometrial thickness reached a sufficient value to proceed with embryo transfer. However, it should be noted that the group required increase of estrogen dose may represent a unique group with poorer prognosis and which may present an inherited bias. Further clinical studies are needed to investigate the influence of a mid-cycle change in estrogen dose and the influence on obstetrical outcomes that are related to placentation.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ranit Hizkiyahu, Email: ranithizk@gmail.com.

Eva Suarthana, Email: eva.suarthana@mcgill.ca.

Einav Kadour Peero, Email: einavkadour@gmail.com.

Ido Feferkorn, Email: idofeferkorn@gmail.com.

William Buckett, Email: William.buckett@muhc.mcgill.ca.

References

- 1.Groenewoud ER, Cohlen BJ, Macklon NS. Programming the endometrium for deferred transfer of cryopreserved embryos: hormone replacement versus modified natural cycles. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(5):768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European IVF-monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Wyns C, Bergh C, Calhaz-Jorge C, De Geyter C, Kupka MS, Motrenko T, Rugescu I, Smeenk J, Tandler-Schneider A, Vidakovic S, Goossens V. ART in Europe, 2016: results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(3):hoaa032. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushnir VA, Barad DH, Albertini DF, Darmon SK, Gleicher N. Systematic review of worldwide trends in assisted reproductive technology 2004–2013. Reprod Biol Endocrinol Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casper RF. Frozen embryo transfer: evidence-based markers for successful endometrial preparation. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(2):248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimadomo D, Soscia D, Vaiarelli A, Maggiulli R, Capalbo A, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L. Looking past the appearance: a comprehensive description of the clinical contribution of poor-quality blastocysts to increase live birth rates during cycles with aneuploidy testing. Hum Reprod. 2019;34:1206–1214. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munne S, Kaplan B, Frattarelli JL, Child T, Nakhuda G, Shamma FN, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy versus morphology as selection criteria for single frozen-thawed embryo transfer in good-prognosis patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1071–9.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masbou AK, Friedenthal JB, McCulloh DH, McCaffrey C, Fino ME, Grifo JA, Licciardi F. A comparison of pregnancy outcomes in patients undergoing donor egg single embryo transfers with and without preimplantation genetic testing. Reprod Sci. 2019;26:1661–1665. doi: 10.1177/1933719118820474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghobara T, Gelbaya TA, Ayeleke RO, Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Cycle regimens for frozen‐thawed embryo transfer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017(7):CD003414. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003414.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Zhou P, Lin X, Wang S, Zhang S. Endometrial preparation for frozen–thawed embryo transfer cycles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Wang H, Pan R, Li Q, Shi J, Zhang S. Comparison of the method of endometrial preparation prior to frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a retrospective cohort study from 9733 cycles. Reprod Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satwik R, Majumdar A, Mittal Gupta S, Tiwari N, Majumdar G, Kochhar M. Natural cycle versus hormone replacement cycle for transferring vitrified-warmed embryos in eumenorrhoeic women A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;10(263):94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu KE, Hartman M, Hartman A, Luo ZC, Mahutte N. The impact of a thin endometrial lining on fresh and frozen-thaw IVF outcomes: an analysis of over 40 000 embryo transfers. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1883–1888. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasius A, Smit JG, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJ, Mol BW, Opmeer BC, Broekmans FJ. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(4):530–41. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Li Y. Endometrial pattern, thickness and growth in predicting pregnancy outcome following 3319 IVF cycle. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glujovsky D, Pesce R, Sueldo C, QuinteiroRetamar AM, Hart RJ, Ciapponi A. Endometrial preparation for women undergoing embryo transfer with frozen embryos or embryos derived from donor oocytes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10(10):CD006359. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006359.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babayev E, Matevossian K, Hensley C, Zhang JX, Bulun SE. Baseline Endometrial thickness or endometrial thickness change in response to estrogen is not predictive of frozen embryo transfer success in medicated cycles. Reprod Sci. 2020;27(12):2242–46. 10.1007/s43032-020-00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Liao S, Wang R, Hu C, Pan W, Pan W, Yu D, Jin L. Analysis of endometrial thickness patterns and pregnancy outcomes considering 12,991 fresh IVF cycles. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21(1):176. 10.1186/s12911-021-01538-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kaye L, Rasouli MA, Liu A, Raman A, Bedient C, Garner FC, Shapiro BS. The change in endometrial thickness following progesterone exposure correlates with in vitro fertilization outcome after transfer of vitrified-warmed blastocysts. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(11):2947–53. 10.1007/s10815-021-02327-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Haas J, Smith R, Zilberberg E, Nayot D, Meriano J, Barzilay E, Casper RF. Endometrial compaction (decreased thickness) in response to progesterone results in optimal pregnancy outcome in frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madero S, et al. Endometrial preparation: effect of estrogen dose and administration route on reproductive outcomes in oocyte donation cycles with fresh embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(8):1755–1764. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]