Abstract

Proteasome inhibitor (PI) therapy has improved the survival of multiple myeloma (MM) patients. However, inevitably, primary or acquired resistance to PIs leads to disease progression; resistance mechanisms are unclear. Obesity is a risk factor for MM mortality. Oxidized LDL (OxLDL), a central mediator of atherosclerosis that is elevated in metabolic syndrome (co-occurrence of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and hypertension), has been linked to an increased risk of solid cancers and shown to stimulate pro-oncogenic/survival signaling. We hypothesized that OxLDL is a mediator of chemoresistance and evaluated its effects on MM cell killing by PIs. OxLDL potently suppressed the ability of the boronic acid-based PIs bortezomib (BTZ) and ixazomib, but not the epoxyketone-based PI carfilzomib, to kill human MM cell lines and primary cells. OxLDL suppressed BTZ-induced inhibition of proteasome activity and induction of pro-apoptotic signaling. These cytoprotective effects were abrogated when lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs) associated with OxLDL were enzymatically reduced. We also demonstrated the presence of OxLDL in the MM bone marrow microenvironment as well as numerous granulocytes and monocytes capable of cell-mediated LDL oxidation through myeloperoxidase. Our findings suggest that OxLDL may be a potent mediator of boronic acid-based PI resistance, particularly for MM patients with metabolic syndrome, given their elevated systemic levels of OxLDL. LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy to reduce circulating OxLDL, and pharmacologic targeting of LOOH levels or resistance pathways induced by the modified lipoprotein, could deepen the response to these important agents and offer clinical benefit to MM patients with metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, multiple myeloma, obesity, oxidized LDL, proteasome inhibitor resistance

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Proteasome inhibitor (PI) therapy has greatly improved the survival of multiple myeloma (MM) patients. Unfortunately, primary or acquired resistance to PIs leads to disease progression and death; resistance mechanisms are unclear. Inflammatory and metabolic factors associated with obesity and/or insulin resistance decrease the efficacy of chemotherapeutics for various tumor types.1 Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is vulnerable to oxidation in people with cardiovascular risk factors.2 Oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein, or oxidized LDL (OxLDL), is a central mediator of atherosclerosis that is elevated in individuals with metabolic syndrome (co-occurrence of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and hypertension that predicts high cardiovascular risk).3 OxLDL has recently been linked to an increased risk of solid cancers and shown to stimulate pro-oncogenic/survival signaling.4 Interestingly, LDL-lowering statin therapy was associated with a reduced risk of MM-specific mortality,5 and in a small study, MM patients refractory to bortezomib demonstrated a reduction in PI resistance with simultaneous statin treatment.6 Thus, OxLDL may play a role in the increased MM mortality associated with obesity.7 We hypothesized that OxLDL acts as a mediator of chemoresistance and evaluated its effects on MM cell killing by PIs. We present data that suggest OxLDL may contribute to MM resistance to boronic acid-based PIs by suppressing their ability to inhibit proteasome activity in MM cells.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. MM cells

The human MM cell lines NCI-H929 (RRID:CVCL_1600), U266B1 (RRID:CVCL_0566), RPMI 8226 (RRID:CVCL_0014), MM1.S (RRID: CVCL_8792) and MM1.R (RRID:CVCL_8794) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). MM1.S (dexamethasone-sensitive) and MM1.R (dexamethasone-resistant) are derived from the parent cell line MM.1 (RRID:CVCL_5801). MM cell lines and primary MM cells isolated from the bone marrow aspirates of patients were cultured as previously described.8 Cell lines were mycoplasma-free and authenticated using short-tandem repeat (STR) profiling within the last 3 years. The institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (protocol #HSC20190183N), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved use of the bone marrow samples.

2.2 |. Lipoproteins

Acetyl-LDL, carbamylated-LDL, native LDL (nLDL) and Cu2+-OxLDL were from Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA). To prepare minimally modified LDL (mmLDL), human LDL was first isolated as described previously,9 and then allowed to autooxidize while stored at 4°C for 2 to 6 weeks in sterile capped plastic tubes.10 To specifically reduce lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs) in oxidatively modified LDLs, 1.0 mg/mL of mmLDL or Cu2+-OxLDL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was incubated in the presence of 10 mM GSH plus ebselen (100 μM) for 1 hour at 37°C and subsequently dialyzed (Slide-A Lyzer Mini Dialysis Device, 3.5K MWCO, Thermo Scientific) into PBS containing 100 μM EDTA for 24 hours. Lipoprotein solutions were evaluated for LOOHs prior to use in experiments according to El-Saadani et al.11

2.3 |. Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the MTS (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5[3-carboxymethonyphenol]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium) solution assay CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Absorbance was measured at 490 nm on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.4 |. Flow cytometric analysis of Dil-Cu2+-OxLDL association with MM cells and apoptosis

To measure the association of Cu2+-OxLDL labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI-Cu2+-OxLDL) with MM cells, 2 × 106 cells were seeded into 24-well plates and incubated with vehicle (PBS) or 1 μg/mL DiI-Cu2+-OxLDL (Alfa Aesar) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 0 to 3 hours. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and fluorescence intensity quantified. Apoptosis was assessed using the Annexin V:PE Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) as previously described.8 Flow cytometry was performed using LSRII flow cytometry and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

2.5 |. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were generated and proteins (20 μg per lane) separated by Western blot as previously described.8 Antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) unless otherwise stated: p-MARCKS (Ser152/156), MARCKS, BCL-2, BCL-XL, phospho-eIF2α (Ser51), phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), ubiquitin, HO-1, POMP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), PSMB5 and GAPDH. Donkey anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and donkey anti-mouse HRP were from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA).

2.6 |. Proteasome activity assay

Proteasome activity was assessed using the Proteasome-Glo Chymotrypsin-like Cell-Based Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. U266 cells (3 × 104 cells per well) were seeded into solid white 96-well microtiter cell culture plates, treated as indicated in the figure legends and then incubated with proteasome Glo reagent containing the bioluminescent substrate Suc-LLVY-aminoluciferin to measure chymotrypsin-like activity. Luminescence was measured with a Synergy HT Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments).

2.7 |. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded particle sections from bone marrow specimens from patients with newly diagnosed MM for CD68 (Dako) 1:2000, CD138 (Cell Marque) Predilute and Myeloperoxidase (Dako) 1:200. IHC was performed on a Ventana XT Immunostainer with I-View DAB detection, which uses an avidin-biotin detection system. IHC was also performed for oxidized phospholipid (E06-biotinylated antibody) from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, Alabama). Tissue sections were manually stained using EDTA antigen retrieval pH 8 followed by incubation with E06-biotinylated antibody 1:25 for 2 hours. Slides were rinsed with tris-buffered saline followed by incubation in streptavidin alkaline phosphatase. Alkaline phosphatase was developed with Vulcan Fast Red (Biocare Medical). Slides were counterstained with a light hematoxylin.

2.8 |. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Student’s t test was used to evaluate statistical significance (Microsoft Excel). Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

LDL oxidation occurs at inflammatory sites that are infiltrated by neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages via reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enzymatic mechanisms such as myeloperoxidase and 12/15-lipooxygenase-derived oxidation.3 There are multiple forms of OxLDL in vivo.3 When extensively oxidized, LDL contains complex and advanced protein (eg, apolipoprotein B) and lipid oxidation products. This form of OxLDL is found in atherosclerotic plaques and other sites of oxidative stress and inflammation.12 The protein modifications render extensively oxidized LDL unable to bind the LDL receptor but able to bind a number of scavenger receptors (SRs) such as SR-A, SR-B1, CD36 and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1), through which it exerts pleiotropic effects on diverse cell types. LDL with primarily early lipid peroxidation products (eg, hydroperoxides) is termed minimally modified LDL (mmLDL) and binds the LDL receptor and TLR4. Less common forms of oxidatively modified LDL contain various protein modifications that enable binding to different scavenger receptors. Acetylated LDL (acetylated apolipoprotein B protein) binds type I and type II scavenger receptors (SR-A/B), CD36 and MARCO, and carbamylation of LDL generates a posttranslational and nonenzymatic modification in which amine-containing residues react with cyanate enabling binding to LOX-1 and SR-A.3

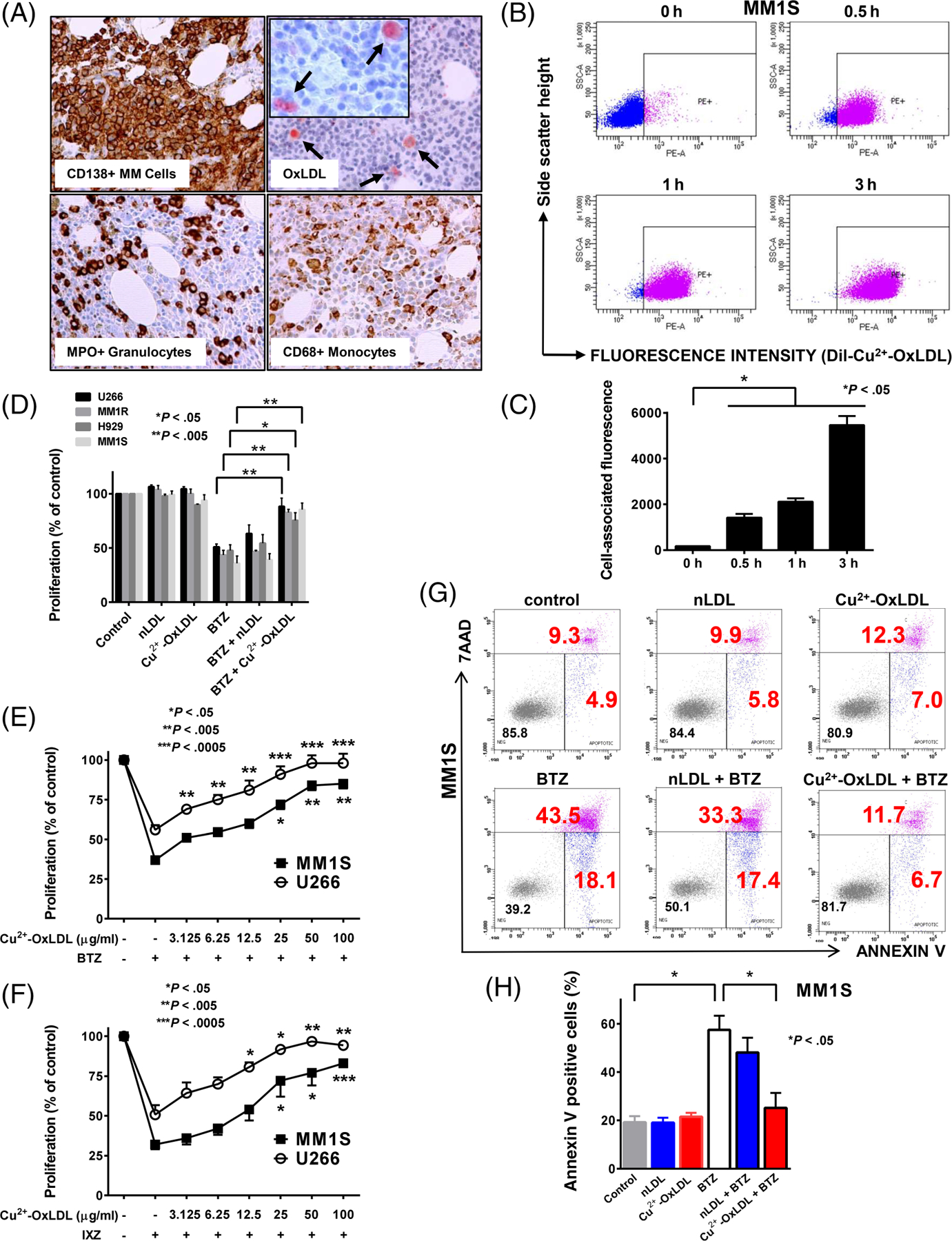

Numerous granulocytes and monocytes that express myeloperoxidase (MPO), a potent mediator of LDL oxidation,13 are present in the MM microenvironment. We evaluated bone marrow biopsies from newly diagnosed MM patients using immunohistochemical analysis and demonstrated that OxLDL is present in the MM microenvironment among CD138-positive MM cells, myeloperoxidase (MPO)-expressing granulocytic cells and CD68-positive monocytic cells (Figure 1A and S1A,B). Extensively oxidized LDL is frequently modeled by Cu2+-OxLDL (copperoxidized LDL), which is generated by exposing LDL to copper sulfate. We used Cu2+-OxLDL in our initial studies to stimulate maximum responses in MM cells. We evaluated if OxLDL was taken up by MM cells. Fluorescently labeled Cu2+-OxLDL rapidly accumulated in MM cell lines (Figure 1B,C and S2A,B). Cu2+-OxLDL suppressed the antiproliferative effects of the PI bortezomib (BTZ) and the second-generation PI ixazomib (IXZ) in a panel of MM cell lines (Figure 1D and S3A, respectively), protected against BTZ-induced time-dependent cytotoxicity (Figure S3B), and at concentrations within the range reported for circulating OxLDL in patients with metabolic syndrome (15–50 μg/mL),14,15 dose-dependently protected MM cells from BTZ and IXZ (Figure 1E,F, respectively). Native LDL (nLDL), in contrast to Cu2+-OxLDL, did not protect various MM cell lines from the antiproliferative effects of BTZ or IXZ (Figure 1D and S3A, respectively) nor its ability to induce apoptosis (Figure 1G,H and S4A,B), which strongly suggests that the oxidative modification of lipids or apolipoprotein in LDL mediate cytoprotection. Cu2+-OxLDL also suppressed the antiproliferative effect of BTZ on primary MM cells isolated from patient bone marrow samples (Figure 2A). Cu2+-OxLDL did not affect the anti-MM effects of the second-generation PI carfilzomib (CFZ) (Figure S5A) or other agents with distinct targets, including lenalidomide, the protein kinase A activator forskolin, the phosphoinositide-3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 and doxorubicin (Figure S5B).

FIGURE 1.

OxLDL is present in the MM microenvironment, associates with MM cells and suppresses the anti-MM effects of bortezomib and ixazomib. A, Immunohistochemical analysis of a bone marrow specimen from a patient with newly diagnosed MM for CD138, OxLDL, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and CD68. B, Representative plot of flow cytometric analysis of DiI-Cu2+-OxLDL association with MM1S cells incubated with 1 μg/mL DiI-Cu2+-OxLDL for 0 to 3 hours. The mean fluorescence of a 35 000 cell population was evaluated. C, Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of cell-associated fluorescence for three independent experiments. D, Proliferation of U266, MM1R, H929 and MM1S cells exposed to 6 nM bortezomib (BTZ) for 48 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL native LDL (nLDL) or Cu2+-OxLDL. Proliferation of MM1S and U266 cells exposed to 6 nM BTZ (E), or 80 and 100 nM ixazomib (IXZ), respectively (F), for 48 hours in the presence of increasing concentrations of Cu2+-OxLDL. Proliferation in (D-F) was assessed by MTS assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of the % of control from three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. G, Representative plot of flow cytometric analysis of the percentage of apoptotic (Annexin V positive highlighted in red) cells by Annexin V and 7-ADD staining following exposure of MM1S cells to 6 nM BTZ for 24 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL nLDL or 50 μg/mL OxLDL. (H) Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of the percentage of Annexin V-positive cells for three independent experiments

FIGURE 2.

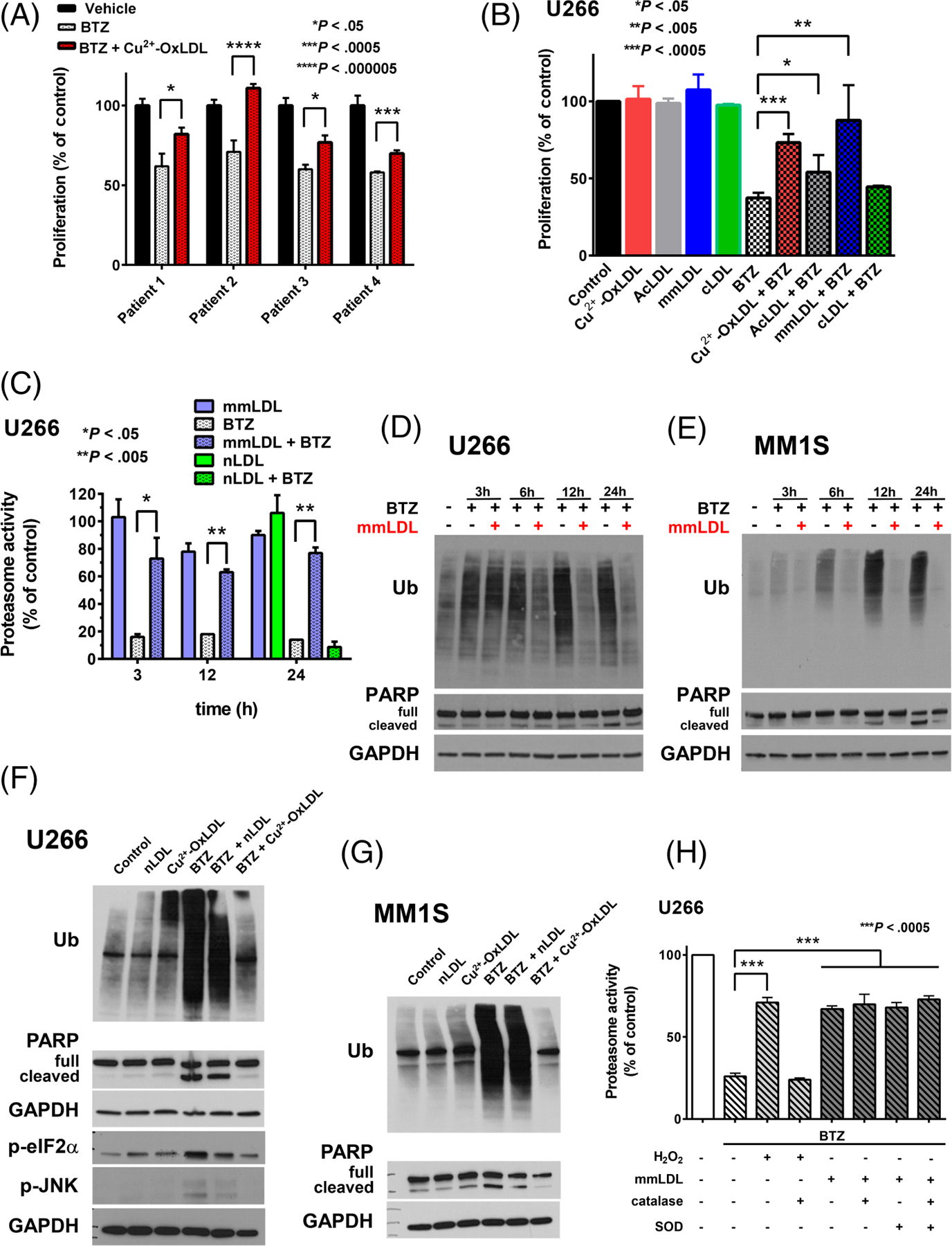

OxLDL protects primary MM cells from bortezomib-induced cytotoxicity and suppresses bortezomib-induced inhibition of proteasome activity and proapoptotic unfolded protein response signaling. A, Proliferation of primary patient MM cells exposed to 35 nM bortezomib (BTZ) for 72 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL Cu2+-OxLDL. Proliferation was assessed by MTS assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of the % of control from an assay performed in quadruplicate for each patient sample. B, Proliferation of U266 cells exposed to 6 nM BTZ for 48 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL Cu2+-OxLDL, acetylated LDL (AcLDL), minimally modified LDL (mmLDL) or carbamylated LDL (cLDL). Proliferation was assessed by MTS assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of the % of control from three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. C, Proteasome activity of U266 cells following exposure to 6 nM BTZ for 3 to 24 hours in the presence or absence of 50 μg/mL mmLDL or nLDL. Representative western blot of ubiquitin accumulation and PARP cleavage (full length and cleaved) following exposure of U266 (D) or MM1S (E) cells to 6 nM BTZ for 3 to 24 hours in the presence or absence of 50 μg/mL mmLDL. F, Representative western blot of ubiquitin (Ub) accumulation, PARP (full length/cleaved), phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), and phosphorylated eIF2alpha (p-eIF2α) following exposure of U266 cells to 6 nM BTZ for 24 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL nLDL or mmLDL. G, Representative western blot of ubiquitin (Ub) accumulation and PARP (full length/cleaved) following exposure of MM1S cells to 6 nM BTZ for 24 hours in the presence of 50 μg/mL nLDL or mmLDL. H, Proteasome activity of U266 cells following exposure of U266 cells to 20 μM H2O2 ± 500 U/mL catalase or 6 nM BTZ ± 500 U/mL superoxide dismutase (SOD) ± 500 U/mL catalase ±50 μg/mL mmLDL for 3 hours. Chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity in (C and H) was assessed as described in Section 2. Data are presented as mean ± SE of the % of control from four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate

We next evaluated the influence of other forms of OxLDL (acetylated LDL, mmLDL and carbamylated LDL) on the anti-MM effects of BTZ. We modeled mmLDL using autooxidized LDL.3,10 Similar to Cu2+-OxLDL, mmLDL potently suppressed the antiproliferative effects of BTZ but not CFZ (Figure 2B and S6A,B, respectively); acetylated LDL exhibited very mild cytoprotection against BTZ (Figure 2B). Since mmLDL does not bind scavenger receptors,3 and neither acetylated LDL nor carbamylated LDL significantly protected MM cells from BTZ, it is unlikely that scavenger receptors are involved in cytoprotection. Because extensively oxidized LDL binds scavenger receptors, it is rapidly cleared from the circulation and thus contributes very little to blood levels of OxLDL. This is in contrast to LDL with primarily lipid oxidation products (eg, mmLDL), which does not bind scavenger receptors, and comprises most of the circulating OxLDL.16 MmLDL was used for the majority of the remaining experiments.

BTZ kills MM cells by suppressing proteasome activity, which results in the accumulation of misfolded protein leading to persistent and severe endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress that triggers proapoptotic unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling through pathways such as double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK)/eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and IRE1/c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase (JNK) pathways.17 MmLDL potently, but not nLDL, suppressed BTZ-induced inhibition of proteasome activity; it restored proteasome activity to nearly control levels (approximately 70% at 3 hours) (Figure 2C). mmLDL did not suppress the accumulation of ubiquinated proteins (Figure S6C and D) or proteasome inhibition (Figure S6E) due to CFZ. Both Cu2+-OxLDL and mmLDL appeared to mildly enhance the antiproliferative effects of CFZ on MM1S cells (Figure S5A and S6B), perhaps due to the increased levels of ROS resulting from simultaneous exposure to the oxidized lipoproteins and CFZ. mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL suppressed the BTZ-induced time-dependent accumulation of ubiquinated proteins and PARP cleavage (Figure 2D,E and S7A,B, respectively), a reliable apoptotic marker generated by the caspase-mediated cleavage of the DNA damage sensor poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1).18 mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL, but not nLDL, suppressed BTZ-induced accumulation of ubiquinated proteins, proapoptotic UPR signaling and PARP cleavage (Figure S7C and Figure 2F,G, respectively). These findings indicate that both mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL mediate cytoprotection by restoring proteasome activity in MM cells exposed to BTZ.

Because boronic acid-based PIs are vulnerable to oxidative degradation,19 in contrast to the epoxyketone CFZ, we explored the possibility that mmLDL exerts its cytoprotective effect by degrading BTZ extracellularly. We evaluated the impact of ROS scavengers (catalase and/or superoxide dismutase) on mmLDL’s ability to suppress BTZ-induced proteasome inhibition. As a positive control agent of BTZ degradation, we used subtoxic concentrations of H2O2 that protect against BTZ-induced MM cell killing (Figure S8). Although the addition of catalase completely abrogated H2O2’s ability to suppress BTZ-induced inhibition of proteasome activity, neither catalase nor superoxide dismutase altered mmLDL’s suppressive effect (Figure 2H).

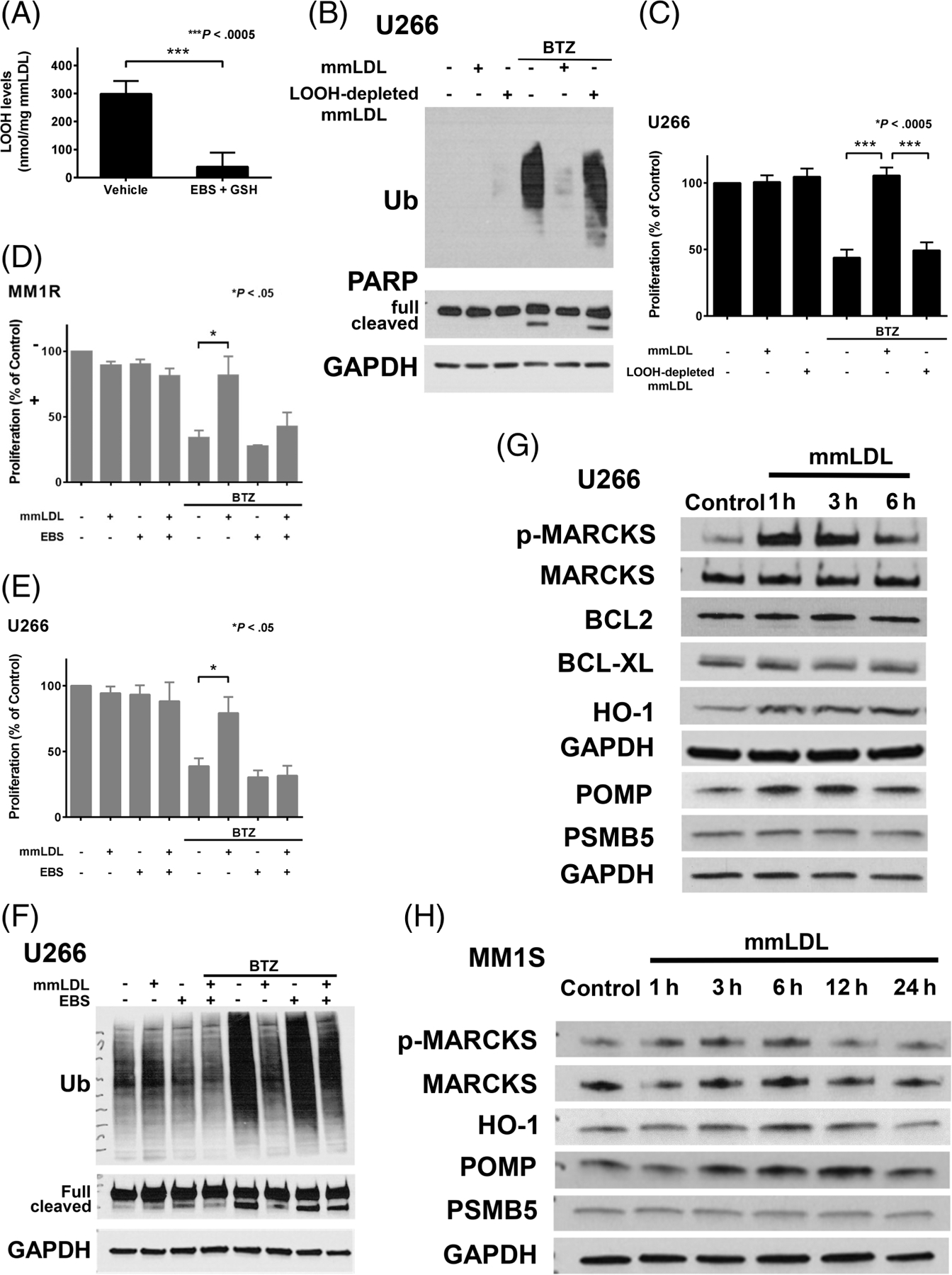

Since the oxidative modifications in mmLDL consist primarily of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs) with no changes to apolipoproteins,3,10 this raises the possibility that LOOHs are mediating the cytoprotective effects of both mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL. To test this notion, these oxidatively modified LDLs were pretreated with the glutathione-dependent selenoperoxidase mimetic ebselen and glutathione to specifically reduce LOOHs within the lipoproteins.20 The pretreatment markedly decreased LOOH levels in mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL (Figure 3A and S9A, respectively). LOOH-depleted mmLDL and Cu2+-OxLDL did not suppress BTZ-induced proteasome inhibition and apoptosis, as evidenced by the accumulation of ubiquinated protein and increase in cleaved PARP (Figure 3B and S9B, respectively), and did not inhibit the antiproliferative effects of BTZ (Figure 3C and S9C, respectively). Ebselen also potently inhibited mmLDL’s protective effects against BTZ when MM cells were simultaneously exposed to the enzyme, oxidized lipoprotein and PI (Figure 3D–F). Despite its well-known antioxidant properties, treatment with ebselen alone dose-dependently killed MM cells, and additive killing observed when it was combined with BTZ (Figure S10A,B). Ebselen can be used safely in people21 and has been demonstrated to lower plasma LOOHs.22 Thus, our findings raise the possibility that combination treatment with ebselen and boronic acid-based PIs may deepen the anti-MM response by lowering LOOHs and via direct additive killing of MM cells, and they provide a rationale for preclinical studies evaluating the feasibility, safety and efficacy of this combination of agents.

FIGURE 3.

Oxidatively modified LDLs suppress the anti-MM effects of bortezomib via associated lipid hydroperoxides. A, mmLDL was pretreated with or without ebselen (EBS) plus glutathione (GSH) to reduce lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs), as described in Section 2. LOOHs associated with the mmLDL or mmLDL pretreated with EBS + GSH (ie, LOOH-depleted mmLDL) used for the experiments in (B and C) were measured as described in Section 2. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of the LOOH levels (nmol/mg mmLDL) from four independent pretreatments. B, Representative western blot of Ub accumulation and PARP (full length/cleaved) following exposure of U266 cells for 24 hours to 6 nM bortezomib (BTZ) and 50 μg/mL mmLDL or LOOH-depleted mmLDL. (C) Proliferation of U266 cells exposed for 48 hours to 6 nM BTZ and 50 μg/mL mmLDL or LOOH-depleted mmLDL. Proliferation of MM1R (D) and U266 (E) cells simultaneously exposed for 48 hours to 25 μM EBS and/or 6 nM BTZ and/or 50 μg/mL mmLDL. Proliferation in (C-E) was assessed by MTS assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE of four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. F, Representative western blot of Ub accumulation and PARP (full length/cleaved) following exposure of U266 cells for 24 hours to 25 μM EBS and/or 6 nM BTZ and/or 50 μg/mL mmLDL. (G) Representative western blot of p-MARCKS (Ser152/156), MARCKS, BCL-2, BCL-XL, HO-1, POMP and PSMB5 following exposure of U266 cells to 50 μg/mL mmLDL for 1 to 6 hours. (H) Representative western blot of p-MARCKS (Ser152/156), MARCKS, HO-1, POMP and PSMB5 following exposure of MM1S cells to 50 μg/mL mmLDL for 1 to 24 hours

Herein, we demonstrated that extensively modified LDL (ie, Cu2+-OxLDL) and mmLDL, the most common form of circulating OxLDL, potently suppressed the ability of the boronic acid-based PIs BTZ and IXZ, but not the epoxyketone-based PI CFZ, to inhibit the proliferation of human MM cell lines and primary cells. We showed that extensively modified LDL and mmLDL protect MM cells against BTZ-induced cytotoxicity by counteracting its inhibition of proteasome activity, and provided evidence that LOOHs associated with the lipoproteins mediate cytoprotection. We further demonstrated that the bone marrow microenvironment in MM contains OxLDL as well as numerous granulocytes and monocytes capable of cell-mediated LDL oxidation through MPO.3,23 Our findings suggest that OxLDL may be a potent mediator of boronic acid-based PI resistance, particularly for MM patients with metabolic syndrome, given their elevated systemic levels of OxLDL. Since LDL is a major carrier of LOOHs in the plasma,24 LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy may be a strategy for improving the treatment response to these agents.

Because mmLDL is not recognized by scavenger receptors, it and extensively modified LDL may be exerting their cytoprotective effects through a nonreceptor-mediated mechanism. Intriguingly, it has been shown that OxLDL-associated LOOHs can trigger cellular oxidative stress responses through the direct exchange of lipids between the lipoprotein and cell membranes.25 There are several mediators of BTZ resistance, including various prosurvival signaling pathways (eg, NF-κB and AKT), members of the Bcl-2 family of antiapoptotic proteins (eg, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2 and Mcl-1), myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS), NF-E2 p45-related factor 2 (NRF2)-regulated cytoprotective proteins such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and proteasome maturation protein (POMP), and proteasomal proteins such as proteasome β5-subunit (PSMB5).26,27 We found that mmLDL (Figure 3G and H) and Cu2+-OxLDL (Figure S11) upregulated the levels of activated MARCKS, HO-1 and POMP. mmLDL produced a stronger response likely due to its increased levels of LOOHs compared with Cu2+-OxLDL (Figure 3A vs S9A). Thus, OxLDL upregulates several mediators associated with BTZ resistance that may be involved in cytoprotection.

In contrast to BTZ and IXZ, CFZ-induced MM cell cytotoxicity was not affected by OxLDL; the reason for this differential effect is unclear. BTZ and IXZ are both boronic acid-derived PIs that reversibly bind the β5 subunit of the 20S proteasome, whereas CFZ is an epoxyketone-based PI that irreversibly binds the β5 subunit.17 Because CFZ is able to overcome BTZ resistance in MM patients, some resistance mechanisms likely differ between them. Considerably more is known regarding mechanisms of BTZ resistance in MM.28 While several studies indicate that POMP, HO-1 and MARCKS are mediators of BTZ resistance,26,27 to our knowledge, their role in CFZ resistance has yet to be established. OxLDL may also be inducing the production or activity of enzymes that preferentially metabolize boronic acid-based PIs (eg, glutathione-s-transferase), or stimulating increases in intracellular ROS that degrade the PIs or LOOH-derived aldehydes (eg, 4-hydroxynonenal) that form adducts with the 20S proteasome29 that interfere with their binding.

An important ramification of the differential effect of OxLDL on MM cell killing by BTZ and IXZ vs CFZ relates to individuals with metabolic syndrome who have elevated levels of these modified lipoproteins and cardiovascular disease.3 CFZ would presumably be more effective in such patients since its activity would not be abrogated by OxLDL. However, CFZ is associated with increased cardiac toxicity compared with BTZ, which limits its use in MM patients with cardiac risk factors.30 Thus, there is a clinical need for strategies to overcome MM resistance to boronic acid-based PIs, especially in patients with cardiovascular risk factors or disease for whom CFZ may be contraindicated. Because our findings suggest that OxLDL may be potent mediator of resistance to these PIs in such patients, studies that evaluate the relationship between in vivo OxLDL levels and treatment response to PIs are warranted. Cholesterol-lowering therapy to reduce OxLDL, pharmacologic targeting of key PI resistance mediators induced by these lipoproteins, or combination treatment with ebselen, could deepen the response to boronic acid-based PIs and offer clinical benefit to obese, insulin resistant and/or dyslipidemic MM patients.

Supplementary Material

What’s new?

Circulating levels of oxidized LDL are elevated in obesity. OxLDL stimulates pro-survival signaling in different cell types and may play a role in the increased multiple myeloma (MM) mortality associated with obesity. Here, OxLDL, via associated lipid hydroperoxides (LOOHs), potently suppressed the inhibition of proteasome activity and MM cell killing by bortezomib and ixazomib. The findings suggest that OxLDL may be a mediator of resistance to these boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors. Reduction of circulating OxLDL by LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy, and pharmacological targeting of LOOH levels or OxLDL-induced resistance pathways, could potentially be used to deepen the response to proteasome inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

VC was supported by a CPRIT Research Training Award (RP140105) and IRACDA Grant K12GM 111726. This work was supported by grant RO1 AT006885 (RA) and R21 CA227414 (EAM) from the National Institutes of Health, a Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund Young Investigator Award (EAM) and an award from the San Antonio Area Foundation (EAM). Flow cytometry data were generated in the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Facility, which is supported by UT Health, NIH-NCI P30 CA054174–20 (CTRC at UT Health) and UL1 TR001120 (CTSA grant).

Funding information

Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, Grant/Award Number: Research Training Award RP140105; Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund; National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Number: R21 CA227414; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, Grant/Award Number: RO1 AT006885; National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: K12GM 111726; San Antonio Area Foundation

Abbreviations:

- AcLDL

acetylated LDL

- BCL-2

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2

- BCL-XL

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- BTZ

bortezomib

- CFZ

carfilzomib

- cLDL

carbamylated-LDL

- Cu2+-OxLDL

copper-oxidized LDL

- Dil- Cu2+-OxLDL

1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate -labeled Cu2+-OxLDL

- DOX

doxorubicin

- EBS

ebselen

- GSH

glutathione

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IRE1

inositol requiring enzyme 1

- IXZ

ixazomib

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LEN

lenalidomide

- LOOH

lipid hydroperoxide

- LOX-1

lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate

- MM

multiple myeloma

- mmLDL

minimally modified LDL

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- MTS

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5(3-carboxymethonyphenol)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- nLDL

native low-density lipoprotein

- NRF2

NF-E2 p45-related factor 2

- OxLDL

oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- p-eIF2α

phosphorylated eIF2alpha

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- PI

proteasome inhibitor

- p-JNK

phosphorylated JNK

- p-MARCKS

phosphorylated MARCKS

- POMP

proteasome maturation protein

- PSMB5

proteasome β5-subunit

- ROS

reactive oxidant species

- SRs

scavenger receptors

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UPR

unfolded protein response

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (protocol #HSC20190183N), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved use of the patient bone marrow samples.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lashinger LM, Rossi EL, Hursting SD. Obesity and resistance to cancer chemotherapy: interacting roles of inflammation and metabolic dysregulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;96:458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigurdardottir V, Fagerberg B, Hulthe J. Circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is associated with risk factors of the metabolic syndrome and LDL size in clinically healthy 58-year-old men (AIR study). J Intern Med 2002;252:440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah PV. Oxidized LDL: diversity, patterns of recognition, and pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010;13:39–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaidakov M, Mehta JL. Do atherosclerosis and obesity-associated susceptibility to cancer share causative link to oxLDL and LOX-1? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2011;25:477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanfilippo KM, Keller J, Gage BF, et al. Statins are associated with reduced mortality in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34: 4008–4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidmaier R, Baumann P, Bumeder I, Meinhardt G, Straka C, Emmerich B. First clinical experience with simvastatin to overcome drug resistance in refractory multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol 2007; 79:240–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teras LR, Kitahara CM, Birmann BM, et al. Body size and multiple myeloma mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. Br J Haematol 2014;166:667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina EA, Oberheu K, Polusani SR, Ortega V, Velagaleti GV, Oyajobi BO. PKA/AMPK signaling in relation to adiponectin’s antiproliferative effect on multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 2014;28: 2080–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asmis R, Wintergerst ES. Dehydroascorbic acid prevents apoptosis induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Eur J Biochem 1998;255:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berliner JA, Territo MC, Sevanian A, et al. Minimally modified low density lipoprotein stimulates monocyte endothelial interactions. J Clin Invest 1990;85:1260–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.el-Saadani M, Esterbauer H, el-Sayed M, Goher M, Nassar AY, Jurgens G. A spectrophotometric assay for lipid peroxides in serum lipoproteins using a commercially available reagent. J Lipid Res 1989; 30:627–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itabe H Oxidized low-density lipoprotein as a biomarker of in vivo oxidative stress: from atherosclerosis to periodontitis. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2012;51:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jerlich A, Fabjan JS, Tschabuschnig S, et al. Human low density lipoprotein as a target of hypochlorite generated by myeloperoxidase. Free Radic Biol Med 1998;24:1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holvoet P, Kritchevsky SB, Tracy RP, et al. The metabolic syndrome, circulating oxidized LDL, and risk of myocardial infarction in well-functioning elderly people in the health, aging, and body composition cohort. Diabetes 2004;53:1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamagishi S, Matsuoka H, Kitano S, et al. Elevated circulating oxidized LDL levels in Japanese subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2007;118:270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. Measuring circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein to evaluate coronary risk. Circulation 2001;103:1930–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincenz L, Jager R, O’Dwyer M, Samali A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response: targeting the Achilles heel of multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther 2013;12:831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jubin T, Kadam A, Jariwala M, et al. The PARP family: insights into functional aspects of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in cell growth and survival. Cell Prolif 2016;49:421–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labutti J, Parsons I, Huang R, Miwa G, Gan LS, Daniels JS. Oxidative deboronation of the peptide boronic acid proteasome inhibitor bortezomib: contributions from reactive oxygen species in this novel cytochrome P450 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol 2006;19:539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas JP, Geiger PG, Girotti AW. Lethal damage to endothelial cells by oxidized low density lipoprotein: role of selenoperoxidases in cytoprotection against lipid hydroperoxide- and iron-mediated reactions. J Lipid Res 1993;34:479–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azad GK, Tomar RS. Ebselen, a promising antioxidant drug: mechanisms of action and targets of biological pathways. Mol Biol Rep 2014;41:4865–4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew P, Yuen DY, Stefanovic N, et al. Antiatherosclerotic and renoprotective effects of ebselen in the diabetic apolipoprotein E/GPx1-double knockout mouse. Diabetes 2010;59:3198–3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinecke JW. Oxidants and antioxidants in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: implications for the oxidized low density lipoprotein hypothesis. Atherosclerosis 1998;141:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nourooz-Zadeh J, Tajaddini-Sarmadi J, Ling KL, Wolff SP. Low-density lipoprotein is the major carrier of lipid hydroperoxides in plasma. Relevance to determination of total plasma lipid hydroperoxide concentrations. Biochem J 1996;313(Pt 3):781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen-Hagge TE, Baumeister E, Bauer T, et al. Transmission of oxLDL-derived lipid peroxide radicals into membranes of vascular cells is the main inducer of oxLDL-mediated oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 2008;197:602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niewerth D, Jansen G, Assaraf YG, Zweegman S, Kaspers GJ, Cloos J. Molecular basis of resistance to proteasome inhibitors in hematological malignancies. Drug Resist Updat 2015;18:18–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Volti G, Tibullo D, Vanella L, et al. The heme oxygenase system in hematological malignancies. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017;27:363–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berenson JR, Hilger JD, Yellin O, et al. Replacement of bortezomib with carfilzomib for multiple myeloma patients progressing from bortezomib combination therapy. Leukemia 2014;28:1529–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohn TJ, Grune T. The proteasome and the degradation of oxidized proteins: part III-redox regulation of the proteasomal system. Redox Biol 2014;2:388–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atrash S, Tullos A, Panozzo S, et al. Cardiac complications in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma patients treated with carfilzomib. Blood Cancer J 2015;5:e272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.