Abstract

Background

The rise in mental health problems in the population directly or indirectly because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a major concern. The aim of this study was to investigate and compare independent predictors of symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Brazilians one month after the implementation of measures of social distancing.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed using a web-based survey. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) were the outcomes. Data were gathered regarding demographics, social distancing, economic problems, exposure to the news of the pandemic, psychiatric history, sleep disturbances, traumatic situations, and substance use. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test - Consumption (AUDIT-C) was also administered. The predictors of the symptoms were investigated using hierarchical multiple linear regression.

Results

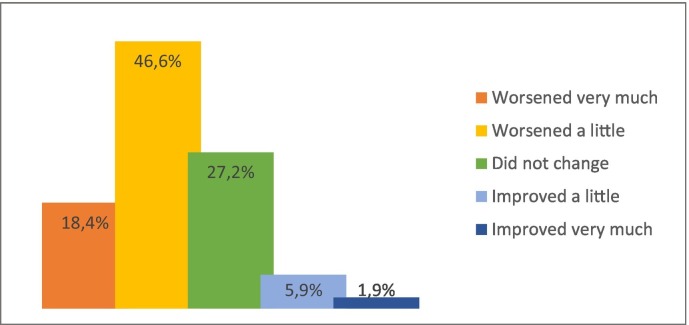

Of a sample of 3587 participants, approximately two-thirds considered that their mental health worsened after the beginning of the social restriction measures. The most important predictors of the symptoms investigated were the intensity of the distress related to the news of the pandemic, younger age, current psychiatric diagnosis, trouble sleeping, emotional abuse or violence, and economic problems.

Conclusions

These results confirmed the hypothesis that the pandemic impacted the mental health of the population and indicated that the level of distress related to the news was the most important predictor of psychological suffering.

Keywords: Stress disorders, Post-traumatic, Depression, Anxiety, Pandemic, COVID-19

Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5; AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test - Consumption

1. Introduction

The emergence and rapid spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with the potential to cause death in the elderly, adults, and even children, and substantial socioeconomic disruption prompted health authorities to call for rapid measures (Holmes et al., 2020; Kadir, 2020). Highly contagious infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, result in psychological distress in the population directly or indirectly. With the expansion of the outbreak, stress may increase concomitantly, which can trigger anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms, especially when individuals experience the possibility of death either for themselves or their loved ones (Sun et al., 2021). In addition, social restriction measures imposed during the pandemic may result in several negative consequences for mental health, leading to stress overload. High rates of symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been reported in the general populations of low-, middle-, and high-income countries during the pandemic (Xiong et al., 2020). All individuals were affected, to a small or large extent, resulting in a second pandemic of mental disorders (Choi et al., 2020).

Because of the ongoing pandemic, the world's population is facing new cultural and social rules, such as the regular use of facemasks and physical distancing. Mass quarantine has been adopted worldwide in several ways. Quarantine is conceptualized as the separation and restriction of movement of people who are exposed to a contagious disease to see if they become sick, aiming to reduce the risk of infecting others (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Duration of quarantine; fear of infection; frustration; boredom; inadequate supplies and information; feelings of helplessness; and loss of a sense of safety, security, and financial stability evoke an increasingly familiar mistrust of others, avoidance, and withdrawal from everyday activities (Brooks et al., 2020). Social distancing associated with quarantine can be a catalyst for many mental health issues, even among previously healthy individuals (Usher et al., 2020).

Despite the necessary measures to contain the rapid spread of the contagion, governmental focus has been on fighting against infection, but the increase in mental disorders is often neglected (Ornell et al., 2020). In Brazil, the prepandemic prevalence of mental disorders was 50% higher than the global prevalence, and specifically for substance use and anxiety disorders, the prevalence was twice as high (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020). This continental country has the sixth highest population in the world and is characterized by cultural heterogeneity and socioeconomic inequity. Similar to other low-and middle-income countries, with low coverage of mental health care, the increase in mental disorders and lack of treatment may achieve epidemic proportions. Because PTSD, major depression, and anxiety disorders have the potential to increase during the pandemic, monitoring the mental health of the population is imperative to plan actions on prevention, health promotion, and treatment.

Therefore, we developed the COVIDPsiq study (www.covidpsiq.org) to monitor the evolution of stress, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in Brazilians during the pandemic (www.covidpsiq.org). This article reports the main results of the first wave of the COVIDPsiq study, which was undertaken one month after the implementation of contagion measures by the Brazilian government. The aim of this study was to investigate and compare the independent effects of demographics, health-related anxiety, social distancing, exposure to the news of COVID-19 pandemic, substance use, and traumatic situations on stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a cross-sectional study nested in a prospective cohort developed to enroll participants within nine months of follow-up during the COVID-19 outbreak using a non-probabilistic convenience sample. A complete description of the methodology of this longitudinal study is available elsewhere (Calegaro et al., 2020).

2.2. Participants and context

The inclusion criterion was individuals living in Brazil aged 18 years or more. Participants with inconsistent answers or incomplete demographic questionnaire (minimal information) were excluded.

The data for the COVIDPsiq study were collected from April 22, 2020, two months after the confirmation of the first case in São Paulo (February 26, 2020) and 41 days after the Brazilian Health Ministry had declared community transmission (March 11, 2020), to May 8, 2020. At the end of this phase, Brazil had 145,328 cases and 9897 deaths (Ministério da Saúde, 2020). Within the southern region, where most of the participants were located, the spread of the contagion was still centered in the metropolitan areas. As the main portion of the sample was from the state of Rio Grande do Sul, we describe some measures adopted prior to the survey. On March 16, 2020, the public calamity was declared, and the first restrictions were implemented, for example, prohibition of interstate collective transportation, activities at the shopping centers and beaches, and big events (Rio Grande do Sul, 2020a). On April 1, 2020, more restrictive measures were adopted, prohibiting the operation of schools, universities, and most commercial establishments, except for essential services, such as drug stores, grocery stores, gas stations, and others (Rio Grande do Sul, 2020b).

2.3. Measures

The study protocol included information on demographics, occupational status (including health professionals and contact with public attendance), income and unemployment, infection by SARS-COV-2, COVID-19 infection in relatives and close contacts, information about emotional and sexual abuse, physical violence, psychiatric history, social distancing and isolation, and substance use. To assess the impact of the news about COVID-19 pandemic, the participants were asked “How do you consider the intensity with which you access information about COVID19?” and “Please indicate the degree of distress (anxiety, discomfort, fear, anger) you feel/felt related to the information during this period”. The first question enquired about the intensity of exposure to the news, with the following categorical answers: none/mild, moderate, constant, and extreme. The second question aimed to assess the perceived level of distress when exposed to the news, with responses ranging from 0 (none) to 10 (severe).

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test - Consumption (AUDIT-C), was applied to measure the level of alcohol abuse. It is a three-item test derived from the complete assessment (AUDIT) and is particularly useful for identifying heavy drinkers (Taufick et al., 2014). A score of 6–7 indicates a high risk of dependence and a score of 8 or more indicates severe dependence.

Two self-report instruments were used as the main outcomes. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) is a 21-item Likert four-point scale (0, 1, 2, and 3) that measures the symptom severity of these three domains (Vignola and Tucci, 2014). DASS-21 is derived from the concept that stress is implicated in depression and anxiety and is a common component in both. Depressive symptoms are assessed as mild when the score on the items corresponding to depression is 10–13, moderate when 14–20, severe when 21–27 and extremely severe if greater than 27. Anxiety symptoms are assessed as mild when the score on the items corresponding to anxiety are 8–9, moderate when 10–14, severe when 15–19 and extremely severe if >20. Stress symptoms are assessed as mild when the score on the corresponding items is 15–18, moderate when 19–25, severe when 26–33 and extremely severe if >34 (Vignola and Tucci, 2014). The PTSD Checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5) is a 20-item questionnaire widely used to screen and monitor the severity of symptoms over time (Lima et al., 2016). A score of 38 out of a maximum of 80 is associated with probable PTSD (Blevins et al., 2015).

2.4. Procedures

Data were collected through a web-based survey using SurveyMonkey® virtual platform. The choice of an electronic survey was based on the possibility of reaching more participants while respecting the social isolation restrictions in Brazil. To maximize the research, we implemented a structured outreach strategy, including social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn), corporate mailing lists (targeted to higher education institutions, governmental bodies, and professional councils), press media, cast news on radio and television, and popular messaging applications in Brazil (WhatsApp® and Messenger®). The disclosure stated that the research was anonymous, and participants had to provide consent to participate in the study.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were stored on the SurveyMonkey® server with access through the principal investigator's (PI) account (VC). Extensive data processing and preparation was carried out. Patients with invalid email addresses were excluded from the study. To identify possible duplicates, a rigorous process was conducted: 1) username and domain separation; 2) correcting usernames and domains by removing special characters, empty spaces, and replacing wrong domains (typing errors); 3) screening for potential duplicates using similar usernames with different domains; 4) manual verification of duplicates (sex, age, city, education, profession, etc.); and 5) merging duplicates and maintaining single confirmed cases. The database was anonymized, de-identified, and accessed upon request from the PI (VC). Continuous variables (age, AUDIT-C, DASS-21, and PCL-5) were not normally distributed; thus, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis (followed by pairwise comparisons) tests were preferred for bivariate analysis and Spearman's correlations.

Multivariate analyses were performed using hierarchical multiple linear regression models (HMLR) to estimate the contribution of each block of independent variables to the outcomes (DASS-21 stress, anxiety and depression, and PCL-5 scores). For each dependent variable, we built five models, from low to high complexity, adding blocks of related variables and testing prediction improvement (Kline, 2016). All blocks included variables using forced entry, as follows: 1) controlling variables (age, sex, and education); 2) socioeconomic data; 3) variables related to the pandemic (social distancing, traumatic situations, symptoms of COVID-19, clinical comorbidities, and distress related to the news of the pandemic); 4) psychiatric information, treatment, and sleep quality; and 5) use of substances (alcohol, tobacco, and use of anxiolytics, opioids, cannabis, and stimulant drugs at least once a month). No substantial multicollinearity was identified and the residuals were normally distributed. Outliers were excluded from the analysis. A significance level of 5% was considered for all the statistical tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS© v23. Missingness was treated using pairwise and list-wise methods in the bivariate and multivariate analyses, respectively.

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee (CONEP; CAAE: 30420620.5.0000.5346). All participants volunteered and agreed to participate in the study. Contact information for mental health care available in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) was provided at the end of the study protocol. Additionally, participants were encouraged to contact the researchers in case of emotional discomfort through the support of the participant service (SPS) available on the research website. The SPS provided medical and psychological teleattendance through email and video calls, using psychoeducation and guidance to help participants cope with stress and refer those with clinically relevant symptoms to mental health services.

3. Results

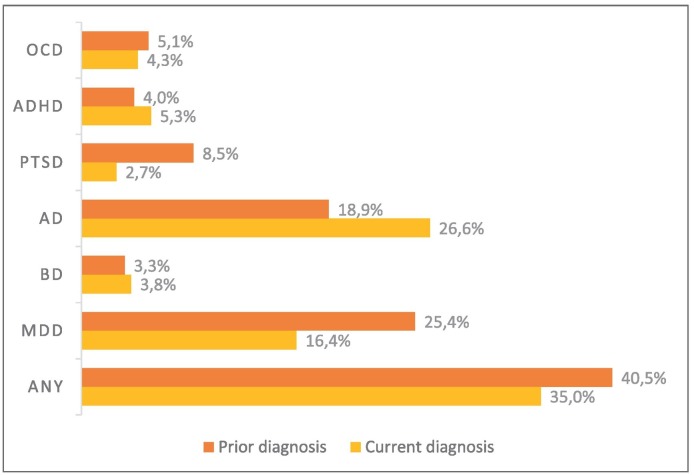

During the first wave of this study (T0), 3796 answers were obtained. Of these, 164 entries were excluded due to duplicity or missing demographics. Brazilians abroad during the study period were excluded from the analysis (38). Seven cases were excluded because of inconsistent or contradictory answers. A total of 3587 participants were included in this study. The sample compositions are listed in Table 1 . Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 849 | 23.7% |

| Female | 2738 | 76.3% | |

| Age (Median; IQI) | 29.0 | 19.0 | |

| Education | Primary or secondary | 339 | 9.5% |

| Undergraduate | 1301 | 36.3% | |

| Graduate | 665 | 18.5% | |

| Postgraduate | 1282 | 35.7% | |

| Ethnicity | White | 3069 | 85.6% |

| Non-white | 518 | 14.4% | |

| Marital status | Single. divorced or widowed | 2274 | 63.4% |

| Married or stable relationship | 1313 | 36.6% | |

| Living arrangement | With family or partner | 2647 | 73.8% |

| With other people | 413 | 11.5% | |

| Alone | 527 | 14.7% | |

| Occupation | Health worker | 653 | 18.2% |

| Worker | 1280 | 35.7% | |

| Student | 1317 | 36.7% | |

| Unemployed | 194 | 5.4% | |

| Retired | 143 | 4.0% | |

| Family income (minimum salariesa) | 1 or less | 231 | 6.4% |

| 1 to 2 | 457 | 12.7% | |

| 2 to 8 | 1667 | 46.5% | |

| 8 to 11 | 470 | 13.1% | |

| 11 or more | 762 | 21.2% | |

| Social distancing | No | 463 | 14.1% |

| Yes, alone | 328 | 10.0% | |

| Yes, accompanied | 2486 | 75.9% | |

| Financial indebtednessb | Improbable | 1226 | 37.4% |

| Possible | 1366 | 41.7% | |

| Highly probable | 434 | 13.2% | |

| Already in debt | 252 | 7.7% | |

| Clinical comorbidity of risk | Any | 989 | 29.5% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 70 | 2.1% | |

| High blood pressure | 237 | 7.1% | |

| Respiratory problems | 402 | 12.0% | |

| HIV/AIDS | 18 | 0.5% | |

| Cancer | 41 | 1.2% | |

| Cardiovascular problems | 61 | 1.8% | |

| Obesity | 341 | 10.2% | |

| Use of immune suppressor | 76 | 2.3% | |

| COVID-19 | Flu-like syndromec | 56 | 1.7% |

| Suspected or confirmedd | 60 | 1.8% | |

| COVID-related trauma | Any | 200 | 6.1% |

| Living with person that had COVID-19 | 66 | 2.0% | |

| Had distancing of close person due to COVID-19 | 54 | 1.6% | |

| Someone close was hospitalized due to COVID-19 | 67 | 2.0% | |

| Loss of relative due to COVID-19 | 17 | 0.5% | |

| Loss of close person due to COVID-19 | 26 | 0.8% | |

| Abuse/violence after the onset of pandemic | Any | 395 | 12.8% |

| Emotional abuse | 388 | 12.6% | |

| Sexual abuse | 5 | 0.2% | |

| Physical violence | 28 | 0.9% | |

| Current psychological or psychiatric treatment | No | 2258 | 67.3% |

| Treatment maintained during pandemic | 576 | 17.2% | |

| Treatment interrupted during pandemic | 523 | 15.6% | |

| Substance use | Tobacco | 279 | 8.3% |

| Benzodiazepinese | 263 | 7.3% | |

| Opioidse | 131 | 3.7% | |

| Cannabisf | 446 | 13.3% | |

| Cocaine, ecstasy or LSDf | 172 | 5.1% | |

| Risk of alcohol dependence (AUDIT-C) | No risk/low | 1859 | 55.4% |

| Moderate | 1045 | 31.1% | |

| High | 285 | 8.5% | |

| Severe | 168 | 5.0% | |

| Stress (DASS-21) | Normal | 1302 | 41.6% |

| Mild | 406 | 13.0% | |

| Moderate | 553 | 17.7% | |

| Severe | 531 | 17.0% | |

| Extremely severe | 340 | 10.9% | |

| Anxiety (DASS-21) | Normal | 1495 | 47.7% |

| Mild | 237 | 7.6% | |

| Moderate | 569 | 18.2% | |

| Severe | 269 | 8.6% | |

| Extremely severe | 562 | 17.9% | |

| Depression (DASS-21) | Normal | 1215 | 38.8% |

| Mild | 396 | 12.6% | |

| Moderate | 641 | 20.5% | |

| Severe | 337 | 10.8% | |

| Extremely severe | 543 | 17.3% | |

| PTSD (PCL-5) | Normal | 2271 | 75.5% |

| Probable PTSD | 736 | 24.5% |

Notes.

Minimum salary was R$ 1045.00 (corresponding to US$ 192.17 in 04/30/2020).

Subjective perception of the probability of financial indebtedness.

Flu-like syndrome was considered when participants presented fever plus at least one of: cough, dyspnea, sore throat, or coryza.

Suspected COVID-19 according to a medical evaluation. Confirmed COVID-19 by laboratory tests.

Use of benzodiazepines or opioids (morphine and derivates) at least once a month, without follow-up by a doctor.

Use of cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy or LSD at least once a month.

Fig. 1.

Prevalences of self-reported prior and current psychiatric diagnoses.

Notes. OCD: obsessive-compulsive disoreder. ADHD:Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. PTSD:posttraumatic stress disorder. AD: anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder). BD: bipolar disorder. MDD: major depressive disorder.

The distribution across the country was heterogeneous, with 3163 (88.2%) respondents located in the southern region, 237 (6.6%) in the southeast and 187 (5.2%) in the other regions of Brazil. The city with the highest number of participants was Santa Maria (n = 1327; 37.0%), located at the center of the state of Rio Grande do Sul (n = 2698; 75.2%). Of the total participants (n = 3587), 3132 participants completed the DASS-21 scale, and 3007, the PCL-5 scale. Considering mild to extremely severe symptoms, the sample prevalence was 58.4% for stress, 52.3% for anxiety, 61.2% for depression, and 24.5% for PTSD.

3.1. Bivariate analysis

Considering the inequity of the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil and the heterogeneity of the location of respondents, we began by analyzing the differences in the level of symptoms among regions, states, and cities. Although the Kruskal–Wallis test showed significant differences in the DASS-21 scales and PCL-5 among regions (P-values ranging from 0.017 to 0.048 from DASS-21 stress to PCL-5), these findings were not supported by pairwise comparisons. Moreover, Kruskal–Wallis test did not present significant differences in the main outcomes when comparing the city where most of the participants were in other microregions, metropolitan areas, or regions, nor did it compare Rio Grande do Sul with other states.

Fig. 2 shows that almost two-thirds of the respondents considered their mental health to have worsened after the social restriction measures were initiated. Perception of change in mental health was correlated with DASS-21 stress (rho = −0.615), anxiety (rho = −0.531), depression (rho = −0.559), and PCL-5 (rho = −0.515). In other words, negative changes corresponded to a higher level of symptoms. All correlations were significant, with p values <0.001.

Fig. 2.

Self-perceived change in mental health after the onset of the pandemic.

Table 2 presents the results of the Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests for the bivariate analyses. Most variables were statistically associated with outcomes, except for the diagnosis of COVID-19 suspected by a health professional or confirmed through laboratory tests.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of independent variables and symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

| DASS-21 Stress |

DASS-21 Anxiety |

DASS-21 Depression |

PCL-5 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn [IQI] | p | Mdn [IQI] | p | Mdn [IQI] | p | Mdn [IQI] | p | ||

| Sex | Male | 14 [16] | <0.001 | 4 [10] | <0.001 | 10 [14] | <0.001 | 15 [24] | <0.001 |

| Female | 20 [16] | 8 [12] | 14 [18] | 23 [27] | |||||

| Age | 18–25 | 22 [16] | <0.001 | 10 [14] | <0.001 | 18 [20] | <0.001 | 28 [27] | <0.001 |

| 25–35 | 18 [16] | 8 [14] | 12 [16] | 21 [27] | |||||

| 36–45 | 16 [12] | 6 [12] | 10 [14] | 18 [26] | |||||

| 46–55 | 12 [12] | 4 [10] | 8 [12] | 13 [22] | |||||

| 56–65 | 10 [10] | 2 [8] | 8 [12] | 10 [17] | |||||

| 66–80 | 8 [10] | 4 [10] | 4 [10] | 9 [17] | |||||

| Level of education | Primary or secondary | 20 [18] | <0.001 | 10 [16] | <0.001 | 16 [18] | <0.001 | 28 [27] | <0.001 |

| Undergraduate | 22 [18] | 10 [16] | 16 [20] | 27 [29] | |||||

| Graduate | 16 [14] | 8 [12] | 12 [17] | 20 [26] | |||||

| Postgraduate | 14 [14] | 6 [10] | 10 [12] | 16 [21] | |||||

| Ethnicity | White | 18 [16] | <0.001 | 8 [14] | <0.001 | 12 [16] | <0.001 | 21 [27] | <0.001 |

| Non-white | 20 [18] | 10 [14] | 16 [18] | 27 [28] | |||||

| Marital status | Single, divorced or widowed | 20 [16] | <0.001 | 8 [14] | <0.001 | 14 [16] | <0.001 | 25 [27] | <0.001 |

| Married or stable relationship | 14 [14] | 6 [10] | 8 [14] | 16 [25] | |||||

| Occupation | Health worker | 14 [14] | <0.001 | 6 [12] | <0.001 | 8 [12] | <0.001 | 16 [23] | <0.001 |

| Worker | 16 [16] | 6 [12] | 10 [16] | 19 [25] | |||||

| Student | 22 [16] | 10 [14] | 16 [20] | 27 [27] | |||||

| Unemployed | 20 [16] | 10 [14] | 16 [20] | 29 [31] | |||||

| Retired | 10 [14] | 4 [10] | 8 [14] | 10 [27] | |||||

| Family income (minimum salaries) | 1 or less | 24 [16] | <0.001 | 14 [18] | <0.001 | 20 [20] | <0.001 | 33 [27] | <0.001 |

| 1 to 2 | 22 [16] | 12 [16] | 18 [20] | 31 [29] | |||||

| 2 to 8 | 18 [16] | 8 [14] | 14 [16] | 23 [27] | |||||

| 8 to 11 | 16 [16] | 6 [12] | 10 [14] | 19 [24] | |||||

| 11 or more | 14 [16] | 4 [10] | 8 [13] | 14 [20] | |||||

| Financial indebtedness | Improbable | 14 [16] | <0.001 | 6 [10] | <0.001 | 10 [16] | <0.001 | 17 [23] | <0.001 |

| Possible | 18 [16] | 8 [14] | 12 [16] | 22 [26] | |||||

| Highly probable | 20 [16] | 10 [14] | 16 [18] | 28 [31] | |||||

| Already in debt | 22 [18] | 12 [16] | 20 [20] | 32 [33] | |||||

| Social distancing | No | 14 [14] | <0.001 | 6 [10] | <0.001 | 8 [14] | <0.001 | 17 [25] | <0.001 |

| Yes, alone | 16 [14] | 6 [14] | 14 [17] | 21 [29] | |||||

| Yes, accompanied | 18 [16] | 8 [14] | 14 [18] | 22 [27] | |||||

| Clinical diagnosis of risk | No | 18 [16] | 0.004 | 8 [12] | <0.001 | 12 [16] | 0.009 | 21 [26] | 0.001 |

| Yes | 18 [18] | 10 [16] | 14 [18] | 23 [30] | |||||

| Flu-like syndrome | No | 18 [16] | 0.0814 | 8 [14] | 0.005 | 12 [16] | 0.008 | 21 [27] | 0.087 |

| Yes | 20 [18] | 14 [18] | 18 [20] | 26 [35] | |||||

| Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 | No | 18 [16] | 0.956 | 8 [14] | 0.779 | 12 [16] | 0.518 | 21 [27] | 0.927 |

| Yes | 17 [13] | 10 [14] | 12 [16] | 21 [22] | |||||

| COVID-related trauma | No | 18 [16] | 0.010 | 8 [14] | 0.001 | 12 [16] | 0.047 | 21 [27] | 0.005 |

| Yes | 20 [16] | 10 [16] | 14 [14] | 26 [27] | |||||

| Intensity of exposure to the news of the pandemic | Mild | 16 [14] | <0.001 | 6 [10] | <0.001 | 10 [18] | <0.001 | 15 [24] | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 16 [14] | 6 [12] | 10 [16] | 20 [25] | |||||

| Constant | 18 [16] | 8 [14] | 12 [16] | 22 [26] | |||||

| Extreme | 20 [18] | 10 [14] | 16 [20] | 26 [31] | |||||

| Emotional abuse/violence | No | 16 [14] | <0.001 | 6 [12] | <0.001 | 10 [16] | <0.001 | 19 [25] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 26 [14] | 14 [16] | 22 [20] | 36 [27] | |||||

| Previous psychiatric diagnosis | No | 16 [18] | <0.001 | 6 [12] | <0.001 | 10 [18] | <0.001 | 19 [27] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 20 [14] | 10 [14] | 14 [18] | 25 [26] | |||||

| Current psychiatric diagnosis | No | 14 [14] | <0.001 | 5 [10] | <0.001 | 10 [12] | <0.001 | 16 [22] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24 [16] | 14 [14] | 20 [18] | 34 [27] | |||||

| Mental health treatment | No | 16 [16] | <0.001 | 6 [12] | <0.001 | 10 [16] | <0.001 | 19 [25] | <0.001 |

| Maintained during pandemic | 20 [14] | 10 [14] | 14 [18] | 26 [26] | |||||

| Interrupted during pandemic | 22 [16] | 12 [16] | 18 [18] | 29 [30] | |||||

| Sleep duration | > 8 h | 20 [16] | <0.001 | 8 [16] | <0.001 | 16 [20] | <0.001 | 25 [28] | <0.001 |

| 6 to 8 h | 16 [16] | 6 [12] | 10 [14] | 18 [25] | |||||

| < 6 h | 24 [14] | 14 [16] | 16 [20] | 32 [30] | |||||

| Sleep latency | < 20 min | 12 [14] | <0.001 | 4 [10] | <0.001 | 8 [14] | <0.001 | 13 [20] | <0.001 |

| 20 to 30 min | 16 [12] | 6 [10] | 10 [14] | 19 [23] | |||||

| 30 to 60 min | 20 [16] | 10 [14] | 14 [16] | 26 [25] | |||||

| > 60 min | 26 [14] | 14 [16] | 20 [20] | 37 [29] | |||||

| Use of tobacco | No | 18 [16] | 0.700 | 8 [14] | 0.344 | 12 [16] | 0.011 | 21 [27] | 0.020 |

| Yes | 18 [20] | 8 [16] | 16 [20] | 25 [32] | |||||

| Use of benzodiazepines | No | 16 [16] | <0.001 | 8 [12] | <0.001 | 12 [18] | <0.001 | 21 [27] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 24 [14] | 12 [14] | 18 [20] | 31 [28] | |||||

| Use of opioids | No | 18 [16] | 0.003 | 8 [14] | <0.001 | 12 [16] | 0.003 | 21 [27] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 20 [16] | 12 [14] | 16 [20] | 28 [29] | |||||

| Use of cannabis | No | 16 [16] | <0.001 | 6 [12] | <0.001 | 12 [18] | <0.001 | 20 [27] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 22 [16] | 12 [14] | 18 [18] | 28 [27] | |||||

| Use of cocaine, ecstasy, or LSD | No | 18 [16] | 0.001 | 8 [14] | 0.006 | 12 [16] | <0.001 | 21 [27] | <0.001 |

| Yes | 22 [16] | 10 [16] | 16 [20] | 30 [31] | |||||

Notes: Mdn: median. IQI: interquartile interval. DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale. PCL-5: Posttraumatic Checklist for DSM-5. LSD: lysergic acid. Significant values are highlighted in bold. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used.

Continuous variables were analyzed using Spearman's correlations. Age was negatively correlated with DASS-21 stress (rho = −0.333; p < 0.001), anxiety (rho = −0.273; p < 0.001), depression (rho = −0.330; p < 0.001), and PCL-5 (rho = −0.276; p < 0.001). Distress related to the news of the pandemic was correlated with DASS-21 stress (rho = 0.531; p < 0.001), anxiety (rho = 0.505; p < 0.001), depression (rho = 0.446; p < 0.001), and PCL-5 (rho = 0.485; p < 0.001). AUDIT-C was weakly correlated with DASS-21 stress (rho = 0.080; p < 0.001), anxiety (rho = 0.044; p = 0.013), depression (rho = 0.089; p < 0.001), and PCL (rho = 0.060; p = 0.001).

3.2. Multivariate analysis

Table 3 highlights the contribution of each block to explaining the variance in the outcomes. In descending order, Block 3, which included variables related to the pandemic, was the most important. Block 1 was composed of age, sex, and level of education, and block 4 was composed of psychiatric diagnoses, treatment, and sleep disturbances. Block 5 accounted for <1% of the total variance. All the models were statistically significant.

Table 3.

Hierarchical multiple linear regression model statistics.

| Outcome | Model | Block | Adjusted R2 | ∆ R2 | F change | fd1 | fd2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS-21 stress | 1 | Age, sex, and education | 0.159 | 0.160 | 187.908 | 3 | 2966 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Socioeconomic factors | 0.192 | 0.035 | 16.088 | 8 | 2958 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | COVID-related variables | 0.422 | 0.231 | 148.495 | 8 | 2950 | <0.001 | |

| 4 | Psychiatric characteristics | 0.499 | 0.078 | 65.851 | 7 | 2943 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | Substance use | 0.503 | 0.005 | 4.667 | 6 | 2937 | <0.001 | |

| DASS-21 anxiety | 1 | Age, sex, and education | 0.122 | 0.123 | 138.175 | 3 | 2963 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Socioeconomic factors | 0.165 | 0.046 | 20.265 | 8 | 2955 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | COVID-related variables | 0.356 | 0.191 | 110.169 | 8 | 2947 | <0.001 | |

| 4 | Psychiatric characteristics | 0.452 | 0.097 | 75.240 | 7 | 2940 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | Substance use | 0.454 | 0.003 | 2.552 | 6 | 2934 | 0.018 | |

| DASS-21 depression | 1 | Age, sex, and education | 0.120 | 0.121 | 136.115 | 3 | 2967 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Socioeconomic factors | 0.176 | 0.058 | 25.959 | 8 | 2959 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | COVID-related variables | 0.347 | 0.173 | 98.227 | 8 | 2951 | <0.001 | |

| 4 | Psychiatric characteristics | 0.428 | 0.082 | 60.785 | 7 | 2944 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | Substance use | 0.435 | 0.007 | 6.464 | 6 | 2938 | <0.001 | |

| PCL-5 | 1 | Age, sex, and education | 0.111 | 0.112 | 120.044 | 3 | 2851 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Socioeconomic factors | 0.177 | 0.068 | 29.555 | 8 | 2843 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | COVID-related variables | 0.372 | 0.196 | 111.603 | 8 | 2835 | <0.001 | |

| 4 | Psychiatric characteristics | 0.473 | 0.101 | 78.355 | 7 | 2828 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | Substance use | 0.477 | 0.005 | 4.284 | 6 | 2822 | <0.001 |

Notes. DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale. PCL-5: Posttraumatic Checklist for DSM-5. Statistically significant p-values are highlighted in bold. R2 represents the percentage of the outcome variable explained by the model. ∆ R2 means the amount of improve in the prediction of the outcome when a new block of variables is added to the model. F statistic indicates the ANOVA statistic for the model. fd:: freedom degrees.

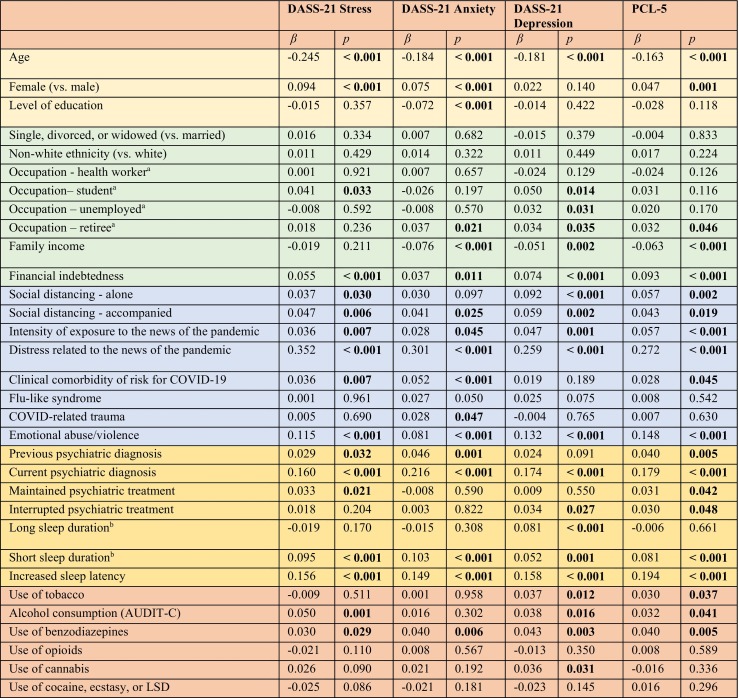

Table 4 presents the resulting coefficients of the hierarchical multiple linear regression. In block 1, age was negatively associated with stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Female sex predicted all outcomes except depression, and education level only predicted anxiety. Note that these variables had greater effects on stress and anxiety than on depression and PTSD.

Table 4.

Hierarchical multiple linear regression coefficients for DASS-21 Stress, Anxiety, and Depression, and PCL-5 scores.

aCompared with workers. b Compared with sleep duration between 6 and 8 h.

Notes: The different background colors represent each block in the hierarchical regression. Intercepts were omitted from the table. Coefficients are standardized βs, which mean the amount of change in the outcome variable (in standard deviations) when the predictor increases one unit (or, in case of dichotomous variables, change from no to yes, for example). Standardized βs are used to easily compare the effect size of each predictor. Statistically significant p-values are highlighted in bold.

In Block 2, occupation was related to depressive symptoms, specifically being a student, unemployed, or retiree. The last factor was associated with anxiety and PTSD. Greater likelihood of indebtedness was associated with greater psychological distress, lower household income, and higher levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Being a health worker did not increase symptom severity at the time of the study. The same was true for ethnicity and marital status.

All variables related more directly to the pandemic, included in block 3, were associated with the outcomes. The distress related to the news of the pandemic presented effect sizes 5 to 10 times greater than the frequency of exposure to information. Having a diagnosed clinical comorbidity of risk for COVID-19 increased anxiety, stress, and PTSD symptoms, whereas flu-like syndrome and COVID-related trauma were related only to increased anxiety. Emotional abuse or violence increased the severity of all symptoms, mostly depressive symptoms and posttraumatic stress. Social distancing was also associated with most outcomes, except social distancing alone, which was not a predictor of anxiety symptomatology. The symptoms of depression and PTSD were more influenced by being alone than by being accompanied. The opposite effect was observed for stress and anxiety.

In block 4, psychiatric disorders and sleep disturbances were important predictors of all dependent variables. Note that the current psychiatric diagnosis presented an effect size approximately four times greater than that of the previous psychiatric diagnosis. In addition, ongoing or interrupted mental health treatment is associated with symptoms of posttraumatic stress. In addition, maintenance of treatment was associated with stress, whereas interruption was associated with depression. Short sleep duration and increased sleep latency were highly associated with these outcomes. Long sleep duration was more important than short sleep duration in predicting the symptoms of depression.

Finally, in block 5, the use of benzodiazepines without medical follow-up predicted all the symptoms. The same was found for the level of alcohol consumption (AUDIT-C), except for anxiety. Moreover, tobacco use predicted the symptoms of depression, PTSD, cannabis, and depression.

4. Discussion

The current study presents the results of the baseline assessment of the COVIDPsiq study, through an Internet-based survey applied approximately one month after the declaration of community transmission of COVID-19 and the implementation of measures to contain its spread. It must be interpreted considering the context that the participants primarily faced fear of the pandemic and the diverse consequences of social distancing rather than infection, hospitalization, or loss of a close contact due to COVID-19. Two-thirds of the participants reported worsening of their mental health condition. Despite the lack of an objective measure to document this change before the pandemic, the levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD were highly correlated with this self-perception. The main predictors of these symptoms were distress related to news of the pandemic, psychiatric diagnosis, younger age, sleeping problems, emotional abuse or violence, and economic problems, which is in accordance with the previous reviews (Luo et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020).

The leading predictor of all outcomes was the level of distress related to the COVID-19 news. The findings indicated that subjective feelings raised by the information were more relevant than the frequency of exposure. Information and ways of communicating through technology may be pursued to cope with stress, as they enable maintenance of communication and social interaction, provide distraction and content, and can be used as a tool for education, work, and information dissemination (Fineberg et al., 2018). However, media excessive engagement and obsessive online activities may lead to severe problems with a significant risk of disordered and addictive use (Vismara et al., 2020). Excessive media exposure is an impairing repetitive behavior, which is highly associated with distress intensity and negative outcomes. Gao et al. (2020) showed an association between high media exposure and increased risk of anxiety and comorbid major depressive disorder compared to low exposure during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China (Gao et al., 2020). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the infodemic phenomenon can make it difficult to search for trustworthy sources and lead to misinformation and information overload, which contributes to distress (World Health Organization, 2020).

Additionally, we suggest that the impact of news on symptoms is linked similarly to the manner disasters are reported by the media. Although the coverage of this type of event is “emotional by nature, whether it focuses on the emotions of individuals directly affected by the tragic events or the collective emotions of the larger community reacting to the misfortunes of others like them” (Pantti and Wahl-Jorgensen, 2007), this aspect can be reinforced according to the used narrative strategies. The transmission of “faces, gestures, proper names, expressions of pain, images of victims (...) give a human and personal character to all catastrophes” (Franz Amaral and Lozano Ascencio, 2015). Simultaneously, with the suffering portrayed by the media, they cooperate to establish a public identification process. Thus, even those who were not directly affected by the disease imagined that they might have been victims. This is one of the pillars of the “virtual victim policy,” a narrative strategy based on the combination of suffering, fear, and risk, in which the audience is encouraged to think that “the event might happen to any individual, it may happen again, and it could have been avoided” (Vaz et al., 2013).

Another concern pointed out in this study was the vulnerability of people with psychiatric diagnoses to aggravation of their symptoms. During the period in which data were gathered, many public mental health outpatient clinics operated with closed doors, offering telephonic guidance for those seeking care. Interruption of treatment, as shown in the results, predicted the levels of symptoms of depression and PTSD. In the absence of a doctor, people may use benzodiazepines, alcohol, and other drugs to cope with stress, anxiety, and insomnia, leading to depression, chronic PTSD, substance dependence, and domestic violence (Telles et al., 2020).

Sleep disruption is clearly associated with symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. This may be because of the confinement for unknown duration and/or fear of becoming infected, as well as when facing traumatic situations. Beck et al. (2021) conducted a cross-sectional study with a representative sample of the general population in France and showed an increase of 25% in trouble sleeping compared with a prior general population survey (performed in 2017) (Beck et al., 2021). In a retrospective survey conducted in China, Li et al. (2020) found that the prevalence of insomnia significantly increased after the COVID-19 outbreak, with 13.6% of participants developing new-onset insomnia and 12.5% with worsening previous sleeping problems (Li et al., 2020). Furthermore, they also observed a significant increase in the length of time spent in bed and total sleep time, as well as a decrease in sleep efficiency. Delayed bedtimes and wake-up times were also noted. Studies have reported sleep problems during pandemics more frequently among women; young adults; unemployed people; individuals with financial problems, mental illness, media overexposure, COVID-19 related stress, increased severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms; and those spending prolonged time in bed (Beck et al., 2021; Léger et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Daytime impairment and the use of sleeping pills are common consequences of troubled sleeping, increasing the potential for drug abuse and dependence (for example, alcohol, or benzodiazepines). These results are strongly consistent with those of the present study, which found that short sleep duration and increased sleep latency were among the most important predictors of stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD, and long sleep duration predicted symptoms of depression.

Social distancing was independently associated with psychological distress, and we observed some differences between those who were alone and those who were accompanied. Loneliness exerted a greater impact on depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms, which can be explained by the deprivation of relationships, while being accompanied was more relevant than being alone regarding stress. Prati and Mancini (2021), meta-analyzed 25 recent studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population mental health and concluded that the psychological impact of social restrictions is small in magnitude and highly heterogeneous (Prati and Mancini, 2021). In our study, social distancing played a secondary role in explaining the symptoms by comparing the effect sizes with the main predictors; however, the containment measures applied may have had indirect effects, which were measured by other variables, such as economic problems and emotional abuse. For some people, staying longer with relatives or partners may flare interpersonal tension, disagreements, and, in some cases, family violence. The latter refers to threats or other forms of violent behavior in families, which can be physical, sexual, psychological, or economic, in addition to child abuse and intimate partner violence. An increase in this behavior due to forced coexistence, economic stress, and fear of the coronavirus has been observed in many countries (Bright et al., 2020; Campbell, 2020). In Brazil, between March 1 to March 25, 2020, there was an 18% increase in the number of complaints of domestic violence shown by the “call 100” and “call 1808” services recorded by the National Ombudsman for Human Rights (ONDH) from the Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights (MMFDH) (Vieira et al., 2020). According to Marques et al. (2020), during a pandemic, this type of violence is associated with an increase in the level of stress generated by the fear of falling ill, uncertainty about the future, and increased consumption of alcohol and other psychoactive substances (Marques et al., 2020). Additionally, Vieira et al. (2020) included economic stress, greater exposure to explorers, and reduced support options, such as contact with relatives and friends as risk factors (Vieira et al., 2020).

Socioeconomic factors were independently associated with many symptoms, indicating potential sources of worry, frustration, and distress. Unemployment and financial indebtedness tend to worsen during pandemics, which, in addition to low family income, can have lasting effects on people's lives. According to the Well Being Trust, an increase in deaths due to alcohol, drugs, and suicide is expected as a consequence of unemployment in the years following the outbreak of the pandemic (Peterson et al., 2020). Furthermore, our findings showed that retirees presented more symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Independent of age, retired either due to being elderly or chronic disease may deal with reduced autonomy, financial problems, free time, and deprivation of usual activities, thus becoming distressed and fearing illness and death. Notably, the students had higher levels of depression. They represented one-third of the sample and were mostly remote undergraduate or postgraduate students. Accordingly, a study conducted in Jordan during the Covid-19 pandemic by Naser et al. (2020) reported a higher prevalence of anxiety among university students (21.5%) than among health professionals (11.3%) and the general population (8.8%) (Naser et al., 2020). Auerbach et al. (2016) found a one-year prevalence of mental disorders in one-fifth of university students from 21 low-income to high-income countries (Auerbach et al., 2016). In this phase of life, young adults must usually cope with high academic demands, social pressure related to the future profession, and financial dependence. We hypothesize that concerns about possible impairments in practical learning; lack of resources to access online classes; routine disruption; and distancing from family, friends, and loved ones may raise feelings of sadness, inability, low self-esteem, abandonment, and hopelessness. Wu et al. (2020) showed that the effect of uncertainty stress on mental disorders was superior to that of life and study-related stress in a nationwide study with college students (Wu et al., 2020).

Having at least one comorbidity was associated with an increased risk of complications of COVID-19-predicted stress and PTSD in addition to anxiety symptoms. Additionally, flu-like syndrome and COVID-related trauma predicted anxiety symptoms. Notably, diagnosis or suspected COVID-19 was not associated with the outcomes. Taken together, these issues suggest a fear of contagion, despite the absence of the disease itself. Notably, when data were gathered, cases were emerging in Brazil, but most of the population had not become infected or lost a relative or friend. These findings can be explained by health anxiety, which may be associated with cyberchondria and worsening media overexposure (Jungmann and Witthöft, 2020). Health anxiety promotes preventive behaviors, such as washing hands and adhering to social distancing, but it also has a negative impact on work and family involvement (Ornell et al., 2020; Trougakos et al., 2020).

Demographics also play an important role in predicting the outcomes. The study found that the younger the age, the higher the levels of symptoms, with the effects of age being more notable on stress. This group may suffer more because of distance from friends, family, loved ones, lack of social activities, and job instability (Xiong et al., 2020). Although both sexes showed increased psychological symptoms during quarantine, women showed higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety (Jia et al., 2020). Other studies also found sex differences in symptom distribution, with women reporting significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression (Solomou and Constantinidou, 2020), and PTSD (Liu et al., 2020) than men. Despite the biological influence of sex, another hypothesis is the need to reconcile work with the care of children and domestic chores, which affects career progression and the salary of women more than that of men. Finally, we found that a low education level was associated with anxiety symptoms. In contrast, Salari et al. (2020) showed that higher levels of education were related to greater symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. The authors argued that a high level of education may lead to self-awareness of health and, therefore, health anxiety. In Brazil, low education is linked to unemployment, poor working conditions, and poor access to health services, which may cause worry and anxiety.

This study has some limitations. First, this is an internet-based survey, in which convenience sample bias may limit external validity. It does not represent the northern regions of the country and, as several surveys of similar methods show, most participants were white wealthy women. Hence, extrapolating these findings to other sociodemographic characteristics may not be applicable. Nonetheless, the sample is from an underrepresented area of the world in a country with a high impact of the pandemic, which will be useful in assessing the global mental health outcomes of COVID-19. Second, all pre-pandemic data were retrospectively collected. We attempted to minimize this by asking questions regarding current information, such as employment, living conditions, and diagnosis, which are not likely to be misled by recall bias. Third, it was not possible to evaluate whether symptoms were clinically relevant to infer an increased incidence of mental illness. The symptomatic assessment utility lies in the assessment of distress oscillation and comparability across the globe using instruments validated in similar samples and is widely used in other studies on the same topic.

Lastly, our current findings were able to highlight relevant variables that appeared to have a crucial impact on symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress, and posttraumatic stress during the initial months of COVID-19 pandemic. It was shown that self-perception of suffering was highly correlated with the outcomes in the study; self-referred level of distress related to the news of the pandemic was the most important predictor of mental soreness of all, which may indicate that subjective issues are a large part of an individual's mental health symptoms during traumatic exposure. We identified other external and internal variables that were shown to be associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, stress, and PTSD, such as age; psychiatric diagnosis; sleeping problems; emotional abuse, and violence; female sex; being a student, retiree, or unemployed; low income; probability of financial loss during quarantine; and substance use. These findings support the importance of some actions that may lead to a better event-coping strategy, such as maintaining the operation of public healthcare institutions, such that all layers of the population can have worthy access and attendance, particularly those who are already mentally ill. To avoid the risk of contagion and provide mental health support, telepsychiatry and telepsychotherapy are valuable solutions that may help patients with variable levels of disease severity (Kalin et al., 2020; Salum et al., 2020a, Salum et al., 2020b). The feasibility of online interventions, however, is dependent on technological resources, such as broadband Internet connections, availability of appropriate smartphones or computers, and the ability to use them. This applies to both patients and care providers and requires investment and time to implement. Nevertheless, economic and technological inequities must be considered, as they limit access to online interventions for older adults, children, and people with low incomes, disabilities, and cognitive impairment (Nadkarni et al., 2020). From a public health perspective, we strongly recommend that mental health services should receive investments to implement telehealth and adapt the setting to meet biosafety regulations to maintain face-to-face attendance for those without digital accessibility.

Considering that the self-referred level of distress related to media exposure was the most significant predictor of mental outcome, it is mandatory to consider controlling strategies against compulsive use of technology as a matter of mental coping (Király et al., 2020). On the other hand, media can be a powerful ally for spreading psychoeducational information using many digital resources, such as videos, podcasts, and written material. They may be useful in clarifying the risks of substance misuse, provide information on sleep hygiene, and encourage people to seek appropriate treatment when necessary, indicating how to access and where to find mental health services of reference. Moreover, attention should be paid to the specific stratum of our society, such as students and those at risk of financial loss during the COVID-19 pandemic; some actions such as financial security loans, flexibilization of study chronograms, and active search of these individuals by mental health programs should lead to a better mental health scenario in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alessandra Naimaier Bertolazi - Writing – Original Draft

Andrea Feijó de Mello - Writing – Review & Editing

Bianca Lorenzi Negretto: Investigation, Writing – Original Draft & Project Administration.

Bruna Fragoso Rodrigues: Writing - Original Draft

Fernanda Coloniese Dala Costa: Writing – Original Draft

Fernando Leite Girardi: Writing – Original Draft

Gabriel Olerich Cecatto- Original Draft

Gustavo Zoratto - Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft

Julia Köchler: Writing – Original Draft

Juliana Motta de Oliveira - Writing – Original Draft

Leonardo Rodrigues: Writing – Original Draft

Leopoldo Pompeo Weber: Writing – Original Draft

Luís Francisco Ramos-Lima: Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft

Luisa Maciel – Writing – Original Draft

Luiza Elizabete Braun: Writing – Original Draft

Maurício S. Hoffmann: Writing – Review & Editing.

Natália Kerber: Writing – Original Draft

Vitor Crestani Calegaro: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, manuscript draft, supervision & project administration.

Vitor Daniel Piccinin: Writing – Original Draft

Conflicts of interest

Vitor Crestani Calegaro worked as speaker for Libbs Pharmaceuticals. Other authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Hoffmann is supported by a research grant from the Brazilian Ministry of Health under the “Termo De Execução Descentralizada - TED 12/2019”.

References

- Auerbach R.P., Alonso J., Axinn W.G., Cuijpers P., Ebert D.D., Green J.G., Hwang I., Kessler R.C., Liu H., Mortier P., Nock M.K., Pinder-Amaker S., Sampson N.A., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Al-Hamzawi A., Andrade L.H., Benjet C., Caldas-de-Almeida J.M., Demyttenaere K., Florescu S., de Girolamo G., Gureje O., Haro J.M., Karam E.G., Kiejna A., Kovess-Masfety V., Lee S., McGrath J.J., O’Neill S., Pennell B.-E., Scott K., ten Have M., Torres Y., Zaslavsky A.M., Zarkov Z., Bruffaerts R. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016;46:2955–2970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck F., Léger D., Fressard L., Peretti-Watel P., Verger P. Covid-19 health crisis and lockdown associated with high level of sleep complaints and hypnotic uptake at the population level. J. Sleep Res. 2021;30:6–11. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins C.A., Weathers F.W., Davis M.T., Witte T.K., Domino J.L. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress. 2015;28:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright C.F., Burton C., Kosky M. Considerations of the impacts of COVID-19 on domestic violence in the United States. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calegaro V.C., Negretto B.L., Weber L.P., Kerber N., Zoratto G., Rodrigues L., Braun L.E., Kochler J., Girardi F.L., Picinin V.D., Maciel L., Labre G.S., Dala Costa F.C. Monitoring the evolution of posttraumatic symptomatology, depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazilians (COVIDPsiq). Protoc. Exch. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.pex-945/v2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Vol. 2019. 2019. COVID-19: When to Quarantine [WWW Document]. Coronavirus Dis.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/quarantine.html [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.R., Heilemann M.S.V., Fauer A., Mead M. A second pandemic: mental health spillover from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020;26:340–343. doi: 10.1177/1078390320919803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde . 2020. Coronavírus: 145.328 casos confirmados e 9.897 mortes [WWW Document]https://antigo.saude.gov.br/noticias/agencia-saude/46857-coronavirus-145-328-casos-confirmados-e-9-897-mortes [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg N.A., Demetrovics Z., Stein D.J., Ioannidis K., Potenza M.N., Grünblatt E., Brand M., Billieux J., Carmi L., King D.L., Grant J.E., Yücel M., Dell’Osso B., Rumpf H.J., Hall N., Hollander E., Goudriaan A., Menchon J., Zohar J., Burkauskas J., Martinotti G., Van Ameringen M., Corazza O., Pallanti S., Chamberlain S.R. Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the internet. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1232–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz Amaral M., Lozano Ascencio C. Palavras que dão a volta ao mundo: a personalização das catástrofes na mídia. Chasqui. Rev. Latinoam. Comun. 2015;0:243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O’Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A.K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Worthman C.M., Yardley L., Cowan K., Cope C., Hotopf M., Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;0366:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . IHME, Univ. Washingt; 2020. GBD Compare Data Visualization [WWW Document].http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare [Google Scholar]

- Jia R., Ayling K., Chalder T., Massey A., Broadbent E., Coupland C., Vedhara K. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann S.M., Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? J. Anxiety Disord. 2020;73 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir M.A. Role of telemedicine in healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Telehealth Med. Today. 2020 doi: 10.30953/tmt.v5.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin M.L., Garlow S.J., Thertus K., Peterson M.J. Rapid implementation of telehealth in hospital psychiatry in response to COVID-19. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2020;177:636–637. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20040372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Király O., Potenza M.N., Stein D.J., King D.L., Hodgins D.C., Saunders J.B., Griffiths M.D., Gjoneska B., Billieux J., Brand M., Abbott M.W., Chamberlain S.R., Corazza O., Burkauskas J., Sales C.M.D., Montag C., Lochner C., Grünblatt E., Wegmann E., Martinotti G., Lee H.K., Rumpf H.J., Castro-Calvo J., Rahimi-Movaghar A., Higuchi S., Menchon J.M., Zohar J., Pellegrini L., Walitza S., Fineberg N.A., Demetrovics Z. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: consensus guidance. Compr. Psychiatry. 2020;100:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. Fourth. ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Léger D., Beck F., Fressard L., Verger P., Peretti-watel P., <collab>Group C.</collab>. Letter to the Editor Poor Sleep Associated With Overuse of Media During the COVID-19 Lockdown. 2020. pp. 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Qin Q., Sun Q., Sanford L.D., Vgontzas A.N., Tang X. Insomnia and psychological reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020;16:1417–1418. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima E.de P., Vasconcelos A.G., Berger W., Kristensen C.H., Nascimento E.do, Figueira I., Mendlowicz M.V. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist 5 (PCL-5) and Life Events Checklist 5 (LEC-5) for the Brazilian context. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2016;38:207–215. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2015-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Zhang F., Wei C., Jia Y., Shang Z., Sun L., Wu L., Sun Z., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu W. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques E.S., de Moraes C.L., Hasselmann M.H., Deslandes S.F., Reichenheim M.E. A violência contra mulheres, crianças e adolescentes em tempos de pandemia pela COVID-19: panorama, motivações e formas de enfrentamento. Cad. Saude Publica. 2020;36 doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00074420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A., Hasler V., AhnAllen C.G., Amonoo H.L., Green D.W., Levy-Carrick N.C., Mittal L. Telehealth during COVID-19—does everyone have equal access? Am. J. Psychiatry. 2020;177:1093–1094. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser A.Y., Dahmash E.Z., Al-Rousan R., Alwafi H., Alrawashdeh H.M., Ghoul I., Abidine A., Bokhary M.A., AL-Hadithi H.T., Ali D., Abuthawabeh R., Abdelwahab G.M., Alhartani Y.J., Al Muhaisen H., Dagash A., Alyami H.S. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2020;10:1–13. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornell F., Schuch J.B., Sordi A.O., Kessler F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Braz. J. Psychiatry. 2020;42:232–235. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantti M., Wahl-Jorgensen K. On the political possibilities of therapy news: media responsibility and the limits of objectivity in disaster coverage. Estud. em Comun. 2007;1:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S., Westfall J.M., Miller B.F. Well Being Trust; 2020. Projected Deaths of Despair During the Coronavirus Recession.WellBeingTrust.org [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Mancini A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021;51:201–211. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor Shna, Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor Shabnam, Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global. Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salum G.A., Rehmenklau J.F., Csordas M.C., Pereira F.P., Castan J.U., Ferreira A.B., Delgado V.B., de Lima M.A., Blauth J.H., dos Reis J.R., Rocha P.B., Guerra T.A., Saraiva I.M., Ronchi B.R., Ribeiro B.L., Konig D.F., Grevet E.H., de Pinho L.B., Schneider J.F., Eustáquio P.R., Ramos M.Z., Marques M.F., Axelrud L.K., Baeza F.L., Lacko S.E., Gramz B.de C., Bolzan L.de M. Supporting people with severe mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for low- and middle-income countries using telehealth case management. Brazilian J. Psychiatry. 2020;42:451–452. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salum G.A., Spanemberg L., Hartmann de Souza L., Harzheim E., Teixeira D.S., Simioni A.R., Motta L.S., Kristensen C.H., de Abreu Costa M., Pio de Almeida Fleck M., Manfro G.G., Dreher C.B., Teodoro M.D., Marques M.das C. Letter to the editor: training mental health professionals to provide support in brief telepsychotherapy and telepsychiatry for health workers in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomou I., Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1–19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio Grande Do Sul . 2020. Decreto no 55.128, de 19 de março de 2020. Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Rio Grande Do Sul . 2020. Decreto no 55.154, de 1o de abril de 2020. Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Sun Z., Wu L., Zhu Z., Zhang F., Shang Z., Jia Y., Gu J., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu N., Liu W. Prevalence and risk factors for acute posttraumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;283:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taufick M.L.de C., Evangelista L.A., Silva M.da, Oliveira L.C.M.de. Alcohol consumption patterns among patients in primary health care and detection by health professionals. Cad. Saude Publica. 2014;30:427–432. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00030813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telles L.E.de B., Valença A.M., Barros A.J.S., da Silva A.G. Domestic violence in the COVID-19 pandemic: a forensic psychiatric perspective. Brazilian J. Psychiatry. 2020;00:5–6. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trougakos J.P., Chawla N., McCarthy J.M. Working in a pandemic: exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020;105:1234–1245. doi: 10.1037/apl0000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher K., Bhullar N., Jackson D. Life in the pandemic: social isolation and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29:2756–2757. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz P., Cardoso J.M., Felix C.B. Risco, sofrimento e vítima virtual: a política do medo nas narrativas jornalísticas contemporâneas. Rev. Contracampo. 2013;24–42 doi: 10.22409/contracampo.v0i25.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira P.R., Garcia L.P., Maciel E.L.N. Isolamento social e o aumento da violência doméstica: o que isso nos revela? Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2020;23 doi: 10.1590/1980-549720200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignola R.C.B., Tucci A.M. Adaptation and validation of the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) to Brazilian Portuguese. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;155:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vismara M., Caricasole V., Starcevic V., Cinosi E., Dell’Osso B., Martinotti G., Fineberg N.A. Is cyberchondria a new transdiagnostic digital compulsive syndrome? A systematic review of the evidence. Compr. Psychiatry. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV) Situation Report - 13 [WWW Document] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Yu L., Yang T., Cottrell R., Peng S., Guo W., Jiang S. The impacts of uncertainty stress on mental disorders of chinese college students: evidence from a nationwide study. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]