Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated potential role of plant-derived miRNAs in cross-kingdom species relationships by transferring into non-plant host cells to regulate certain host cellular functions. How nutrient-rich plants regulate host cellular functions, which in turn alleviate physiological and disease conditions in the host remains to be explored in detail. This computational study explores the potential targets, putative role, and functional implications of miRNAs derived from Carica papaya L., one of the most cultivated tropical crops in the world and a rich source of phytochemicals and enzymes, in human diet. Using the next-generation sequencing, -Illumina HiSeq2500, ~ 30 million small RNA sequence reads were generated from C. papaya young leaves, resulting in the identification of a total of 1798 known and 49 novel miRNAs. Selected novel C. papaya miRNAs were predicted to regulate certain human targets, and subsequent annotation of gene functions indicated a probable role in various biological processes and pathways, such as MAPK, WNT, and GPCR signaling pathways, and platelet activation. These presumptive target gene in humans were predominantly linked to various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, mental illness, and platelet disorder. The computational finding of this study provides insights into how C. papaya-derived miRNAs may regulate certain conditions of human disease and provide a new perspective on human health. However, the therapeutic potential of C. papaya miRNA can be further explored through experimental studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00438-022-01904-3.

Keywords: miRNA, Carica papaya, Next-generation sequencing, Cross-kingdom

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are one among the various classes of non-coding RNAs with a length of 18–24 nucleotides (O'Brien et al. 2018; Pirrò et al. 2021). They are evolutionarily conserved, single-stranded and extensively studied in plants, animals, insects, and viruses (Li et al. 2018). The primary function of miRNA is to regulate the expression of target genes by direct binding of miRNA to the complementary sequence in the 3' untranslated regions of the target messenger RNA (mRNA) within the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) by a mechanism called miRNA-mediated gene repression (O'Brien et al. 2018). There are two processes involved in this mechanism, viz., site-specific cleavage and translational repression (Gu and Kay 2010). The former occurs at the post-transcriptional level and involves argonaute proteins that cleave target mRNA preferentially at the 5' monophosphate via endonuclease activity, followed by mRNA degradation (Carthew and Sontheimer 2009). While the latter consists of the repression of initiation and post-initiation during translation, ribosome stalling and ribosome drop-off are also observed (Richter and Coller 2015). The process of translational repression is well established in animals, whereas there are only a few reports that indicate miRNAs' role in inhibition of translation initiation in plants (Huntzinger and Izaurralde 2011). It is estimated that miRNAs may regulate about 60% of human protein-coding genes with at least one known miRNA-binding site in their target sequences (Friedman et al. 2009). Plant and animal miRNAs regulate gene expression through subtle biogenesis mechanisms, with DROSHA in animals and DCL1 in plants carrying out the maturation process (Wang et al. 2019). miRNAs play a role in cellular processes like proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, as well as development, metabolism, immune response, and hormone signaling in animals (Libri et al. 2013; Bushati and Cohen 2007; Zhang et al. 2007). In contrast, plant-derived miRNAs are involved in stress response, homeostasis, and flowering processes (Dugas and Bartel 2004; Kruszka et al. 2012).

The first pioneering work on detection of plant-derived miRNA (miR168a) in sera and tissues stemming from food ingestion in animals, and the subsequent inhibition of lipoprotein receptor adapter protein 1, laid the foundation for the concept of cross-kingdom regulation (Zhang et al. 2012). This study opened the avenue for researchers to investigate plant-derived miRNAs as potential bioactive molecules for therapeutic interventions. Food consumption is a major route for miRNA transfer from plant to animal, allowing exogenous miRNAs from the diet to influence critical cellular processes in the animal (Samad et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021). Emerging evidence also pointed out that such exogenous miRNAs can sustain in the human gastrointestinal tract (Mar-Aguilar et al. 2020). An alternative approach is to synthesize plant-derived functional miRNAs using bioengineering techniques to readily deploy in human disease models to promote the utilization of such miRNAs in human clinical trials. For example, oral administration of plant-derived miRNA159 suppresses breast cancer growth in mice (Chin et al. 2016). Recently, an in vitro study revealed that the plant miRNA156a found in dietary green vegetables can directly regulate junction adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A), one of the up-regulated genes of atherosclerotic lesions. This miRNA in human aortic endothelial cells was found to suppress JAM-A, implying that this miRNA could be used as a clinical intervention in anti-inflammatory treatments for cardiovascular disease (Hou et al. 2018). Li et al. in 2021 published a comprehensive review on plant-derived miRNAs on cross-kingdom regulation of human target genes/diseases covering various therapeutic applications (Li et al. 2021). Research supporting the cross-kingdom miRNA-mediated gene regulation is gaining attention, while some reports challenge the effectiveness and detection of orally taken plant-derived miRNAs. One such study by Dickinson et al. showed that miR168 derived from rice exhibited had no cross-kingdom regulation in the levels of LDLRAP1 found in mouse liver which contradicted Zhang et al.'s work. However, Zhang et al. defended this, saying that the results would have been based on a biased sequencing method between plants and animals (Zhang et al. 2012; Dickinson et al. 2013). Since then, the debate has continued based on the results by different groups of scientists who has provided evidence for or against the concept, of cross-kingdom transfer of miRNAs through various dietary sources and their regulation of mammalian genes over issues, such as methodology, contamination, and detection sensitivity (Li et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2013). Scientists reviewed evidences for and against the diet-derived miRNAs from plants, meat, milk, and exosomes. They concluded that the biological relevance of plant miRNA-mediated gene regulation via cross-kingdom transfer was inconclusive due to lack of reproducibility of experimental results (Samad et al. 2021; Mar-Aguilar et al. 2020). However, there was a study that provided convincing evidence that plant miRNAs in honeybees can regulate caste development and cause similar changes when fed to Drosophila (Zhu et al. 2017). Along these lines, computer-based prediction of human targets using plant-derived miRNAs encourages the narrows down the list of miRNAs from a large pool. Subsequent studies animal cell models can be done to validate these target genes and their possible functional roles in physiological and disease conditions (Jha et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2019a, b; Gadhavi et al. 2020).

Carica papaya L. belongs to the Caricaceace family. It is a common and delicious fruit plant due to its nutritional and medicinal value attributed to the vast number of flavonoids, saponins, papain, and several vitamins (Nurowidah 2019; Yogiraj et al. 2014). Globally, it is primarily used as a traditional herbal medicine for treating various diseases (Hossain et al. 2020). Wall (2006) documented the application of C. papaya in treating several conditions, such as stomach disorders, diarrhea, skin diseases, male contraceptives, and home remedies for the common cold (Wall 2006). The extracts from C. papaya leaves, fruits, and seeds were shown to possess anti-cancer activities in colorectal, prostate, cervical, and breast cancers (Aravind et al. 2013; Lohsoonthorn and Danvivat 1995; Shahar et al. 2011; Pandey et al. 2017; Siegel et al. 2010). Moreover, few studies reported the significance of C. papaya leaves juice in increasing the platelet count among patients suffering from Dengue fever (Ahmad et al. 2011; Rajapakse et al. 2019).

With the advent of next-generation sequencing technology and advanced bioinformatics methods, research efforts were actively pursued to identify miRNAs from expressed sequence tag (EST) and small RNA sequencing datasets (Jha et al. 2021; Patel et al. 2019a; Kumar et al. 2017). In 2012, Rishi et al. reported 60 miRNAs from leaf tissues, flowers and PSRV infected leaves, by analyzing the annotated miRNA expression revealed that PRSV-infected leaves have a higher accumulation of some miRNA* (Aryal et al. 2012). It has been reported in C. papaya that miRNAs (75 conserved and 11novel) isolated from young leaves and female flowers regulate genes involved in ethylene signaling pathway that implies their role during fruit development and ripening (Liang et al. 2013). However, most studies were performed to study how miRNAs regulate their regulatory pathways, implying an inter-species analysis. Although the inter-species analysis was made to study the role of C. papaya-derived miRNAs in regulating certain physiological conditions (e.g., fruit ripening, seed storage in freeze state), this is the first-such effort addressing how C. papaya-derived miRNAs regulate human target genes with strong associations in human diseases in an intra-species (also known as cross-kingdom) manner (Liang et al. 2013). We utilized the small RNA high-throughput technology to generate sequence reads of C. papaya young leaves and subsequently, identified the known and the novel miRNAs. The predicted novel miRNAs were found to regulate certain human genes involved in platelet activation, cancer, and mental illness. The putative role of targeted human genes in relevance to disease conditions was delineated using gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis along with the literature-driven data to develop a hypothesis of miRNA-mediated gene regulation. We believe that this computational novel miRNA prediction using the cross-kingdom approach will shed light on the understanding of how C. papaya-derived miRNAs regulate human genes in disease states.

Materials and methods

Small RNA library construction of C. papaya leaves

A group of four C. papaya plants germinated from the seeds obtained from same source were grown on the grounds of Gujarat University Girls Hostel, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, at the ambient temperature of 30−37 °C. Young leaves were sampled from 2-month-old papaya plants in February 2020 and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for laboratory studies. The samples were stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation. The total RNA was isolated using ZR plant RNA miniprep Kit (Zymo Research). The quality and quantity of the isolated RNA were checked on 1% denaturing RNA agarose gel and Nanodrop/Qubit fluorometer, respectively. The small RNA sequencing libraries were prepared from the isolated total RNA using the TruSeq Small RNA library preparation kit (Eurofins Scientific, Bangalore, India) as per the manufacturer’s instruction. The protocol includes adapter ligation, reverse transcription, PCR amplification, and pooled gel purification to generate a library product. In this protocol, a RNA 3' adapter is specifically modified to target microRNAs and other small RNAs that have a 3' hydroxyl group resulting from enzymatic cleavage by Dicer or other RNA processing enzymes. The adapters are ligated to each end of the RNA molecule, and a reverse transcription reaction is used to create single-stranded cDNA. The cDNA is then PCR-amplified using a common primer and a primer containing one of the index sequences. The amplified PCR product with index sequences was size-selected and purified on a 6% TBE gel. For quantity and quality control (QC) of the library, the gel area pertaining to the average length of the library was selected and purified libraries were analyzed in the 4200 Tape Station system (Agilent Technologies) using High sensitivity D1000 Screen tape. Finally, the cluster generation and sequencing of the sample were carried out after obtaining the Qubit concentration for the libraries and the mean peak sizes from the Agilent Tape Station profile; the PE Illumina libraries were loaded onto HiSeq2500 for cluster generation and sequencing.

Bioinformatics data analysis and identification of miRNAs from C. papaya

Filtration and quality check of generated sequences

The raw reads generated by Illumina HiSeq2500 were analyzed using FastQC to check the quality of small RNA data (Andrews 2010). Cutadapt tool was utilized to remove adapters and low-quality bases. The high-quality reads were then mapped to the Rfam database (Rfam 13.0) (http://rfam.sanger.ac.uk/) (Martin 2011; Griffiths-Jones et al. 2003). Using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA) package resulted in the removal of other non-coding RNAs (rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, SnoRNA) and degraded fragments of mRNA (Li and Durbin 2009). Sequences longer than 18 nt were used as a clean read for the identification of known and novel miRNAs. The schematic workflow is shown (Supplementary Material 5, Figure S1).

Identification of known and novel miRNAs in C. papaya and phylogenetic analysis

For the identification of known miRNAs, the remaining clean reads were aligned to the publicly available miRbase (Release 22.1: October 2018) database with plant species. The 10,414 plant mature miRNA sequences were used as a query in homology searches using Blastn against the clean reads with parameters set as follows “e-value 1000; maximum targets 1000; word size 17 and maximum mismatch 2”. The MIREAP program was used to predict novel miRNAs according to the following parameters: “minimal miRNA reference sequence length of 20 nt and maximal miRNA reference sequence length of 24 nt; minimal depth of Drosha/Dicer cutting site is 3; maximal copy number of miRNAs on the reference is 20; iv) maximal free energy allowed for a miRNA precursor was − 20 kcal/mol; maximal space between the miRNA and miRNA* is 35; minimal base pairs of the miRNA and miRNA* is 14; maximal bulge of the miRNA and miRNA* is 4; maximal asymmetry of the miRNA/miRNA* duplex, 5; and flank sequence length of miRNA precursor, 100” (Li et al. 2012). The selected sequences were then folded into a secondary structure using an RNA folding program UNAfold (Markham and Zuker 2008). Additionally, we have constructed the phylogeny tree to understand the known nature of identified novel miRNAs (Kumar et al. 2016).

Target prediction of known and novel miRNAs in human

To predict the putative target genes of the identified miRNAs, the mature miRNA sequences were queried against human transcripts using the psRNATarget webserver (Dai et al. 2018). Stringent parameters used for verifying complementary and highest homology between the miRNA and complementary human transcript sequences were: “multiplicity of target sites 2; maximum expectation value 3; range of central mismatch for translational inhibition 9–11 nucleotides; maximum mismatches at the complimentary site ≤ 4 without any gaps”.

Functional enrichment and pathway analysis of identified targeted genes

The target sequences identified from the psRNATarget webserver were then annotated through similarity searches against protein databases using the BlastX tool. Further, the result file was loaded the OmicsBox package which resulted in gene ontology annotations with Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) levels based on a cut-off of p value < 0.05 (Conesa et al. 2005). To understand the complex network of regulatory pathways modulated by miRNAs, it is important to study the roles or functions of the identified miRNA target genes. Biological pathways of humans and involvement of genes were retrieved from the REACTOME database and KEGG maps p values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant (Fabregat et al. 2018; Kanehisa and Goto 2000).

Network regulatory interaction of targeted genes

To further analyze the function of predicted genes, Cytoscape software (version 3.6.1) was employed to construct and analyze the miRNA-hub gene network. Hub is the top 10% of the nodes in the high-confidence protein interactome ranked by node degree scores (the number of interactions that are associated with a given node), this high-confidence scores based on the experimental evidence (Tripathi et al. 2013). Hub nodes in these complexes were detected with several parameters, such as Degree, Bottleneck and MCC, DMNC, MNC, ECCENTRICITY and CLOSENESS, to assess its property, significance and organization using Cytohubba plugin (Chin et al. 2014).

Results

Sequencing and bioinformatics data analysis of C. papaya

The libraries were prepared from QC-passed RNA samples using Illumina TruSeq Small RNA library preparation kit and generated ~ 30 million reads (Supplementary Material 5, Figure S2). A total of 33,852,518 raw sequence reads were generated using the HiSeq2500 Illumina platform. A total of 25,092,134 (74.12%) clean reads were obtained after removing low-quality reads, short fragments, and adaptor sequences. The sequences of other non-coding RNAs leading to 23,11,591 (9.2%) reads were filtered out. In the remaining clean reads of 22,780,543 (67.3%), a length of 18–50 bp was used to identify known and novel miRNAs. The base frequency distribution of clean reads is shown in (Supplementary Material 5, Figure S3).

Identification of known miRNAs in C. papaya

A total of 1798 known miRNAs belonging to 127 families were identified from the small RNA population using BlastN homology search against mature plant miRNAs in the miRBase repository (version 22). The known miRNA families, miR156, miR166 and miR159 were identified which consisted of a maximum number of 163, 160 and 147 members, respectively while 20 miRNAs families contained only one member. The total read count of each miRNA was studied to obtain an outline of the apparent expression level of miRNA in C. papaya young leaf tissue. Our bioinformatic analysis revealed, the maximum expression was observed for the miR166 family, i.e., 147,868 reads, followed by the miR156 and miR396 families with 123,144 and 70,233 reads, respectively. 25 miRNA families were observed to have less than 10 reads (Fig. 1). Additionally, the length of the miRNAs was found in the range of 18–24 nt wherein the miRNAs containing 21 nt were the most abundant (31.45%) followed by miRNAs of length 20 nt (Supplementary Material 1).

Fig. 1.

Reads and member distribution of identified known miRNAs. MiR156 and miR166 shows the highest family members and miR157 shows the lowest

Identification of novel miRNAs in C. papaya

A total of 49 novel miRNAs were identified from the high-quality sequence reads. The maximum expression was observed for the Cpa_mir-m2262 i.e., 72,228 reads, followed by the Cpa_mir-m1481 with 72,161 reads respectively (Supplementary Material 1). The length of the putative novel miRNAs varied from 19 to 25 nt within which 51.61% were 20 nt long and the precursor length varied from 74–101 nt. Loong and co-workers have shown that miRNA precursors have lower minimum free energy (MFE) to ensure the thermodynamic stability of the hairpin loop (Loong and Mishra 2007). Here, the MFE value of the identified miRNAs was in the range of −26.3 to −53.4 kcal/mol (Table 1, Supplementary Material 2). To standardize the possible effect of sequence length and to differentiate miRNAs from other non-coding RNAs, the MFEI value was calculated and was found to be in the range of −0.64 to −1.76 indicating that the identified miRNAs were accurate. Further, the AMFE value of the predicted miRNAs was in the range of −40.41 to −64.93 kcal/mol (Table 1). Most miRNAs were located on the 3' arm of the secondary structure compared to the 5' arm. Out of 49, 36 miRNAs were in the 3'arm of secondary structure. Furthermore, (G + C) % and the (A + U) % ranged from 23.81% to 71.43% and 25% to 76.19%, respectively (Supplementary Material 3).

Table 1.

Details and characterization of identified novel miRNAs in terms of MFE = minimal folding energy, AMFE = adjusted minimal folding free energy, MEFI = minimal folding free energy index

| S. no | Novel miRNAs of Carica papaya | Mature sequences | Precursor length | MFE (− Kcal/mol) | AMFE | MFEI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cpa_mir-m0016 | GGGGCCCAGAACGCUAAAAGGUAGG | 77 | − 26.3 | − 34.16 | − 0.82 |

| 2 | Cpa_mir-m0063 | UCACUGCAGAUUUGAAUAUUCAUC | 101 | − 53 | − 52.48 | − 1.56 |

| 3 | Cpa_mir-m0233 | GGUUGGUCGGGGCUUCUGAC | 96 | − 41.9 | − 43.2 | − 0.64 |

| 4 | Cpa_mir-m0310 | AUCCGUGUGCGCAGGAACGGAUCU | 87 | − 47.2 | − 54.25 | − 0.8 |

| 5 | Cpa_mir-m0370 | CACUGAAAAACGGAGCUUACCGGC | 92 | − 42.2 | − 45.87 | − 0.75 |

| 6 | Cpa_mir-m0749 | CGCGUUGUGGACACGCUGACAUCG | 79 | − 37.7 | − 47.72 | − 0.77 |

| 7 | Cpa_mir-m0440 | AGCGGUCAGAAGUGGCUCCGGCAC | 95 | − 41.3 | − 43.02 | − 0.66 |

| 8 | Cpa_mir-m0508 | CGCACGGACGGCCUGAAUGCG | 96 | − 45.2 | − 47.58 | − 0.7 |

| 9 | Cpa_mir-m0511 | UGGAUCUUCUUCUCUGGCAAGGG | 99 | − 43.5 | − 43.94 | − 0.67 |

| 10 | Cpa_mir-m0974 | CUGCUGUGUGAACGAUGUGUGCAC | 97 | − 41.5 | − 42.78 | − 0.73 |

| 11 | Cpa_mir-m1108 | ACGAACUGGAGCACACUGCAUGGC | 74 | − 29.9 | − 40.41 | − 0.79 |

| 12 | Cpa_mir-m1192 | CACUGAAAAACGGAGCUUACCGGC | 92 | − 42.2 | − 45.87 | − 0.75 |

| 13 | Cpa_mir-m1285 | CUGACGGCGCCAUCUCUCCUG | 95 | − 46.9 | − 47.86 | − 0.85 |

| 14 | Cpa_mir-m1392 | AAUCUGGGUCGUUCGUGCGCGCGG | 84 | − 40.6 | − 48.33 | − 0.69 |

| 15 | Cpa_mir-m1403 | UGUAUAUGUAUGCACAUGCCA | 77 | − 47 | − 61.04 | − 1.74 |

| 16 | Cpa_mir-m1414 | AUAUGUAUGCACAUGCCACA | 83 | − 49.2 | − 59.28 | − 1.76 |

| 17 | Cpa_mir-m1481 | AUAGAUCAUGUGGCAGUUUCA | 98 | − 49.2 | − 50.2 | − 1.14 |

| 18 | Cpa_mir-m1488 | CUGACCGGGGCUGCUGACGUG | 73 | − 47.4 | − 64.93 | − 0.91 |

| 19 | Cpa_mir-m1566 | UCUGACCGGGCCUGCUGACGUGGC | 75 | − 43.1 | − 57.47 | − 0.83 |

| 20 | Cpa_mir-m1590 | UGCUGACUGGGCUAUUGACGUGGC | 101 | − 41.6 | − 41.19 | − 0.64 |

| 21 | Cpa_mir-m1612 | CUGUCCGAUCGCGCUCACGC | 83 | − 40.7 | − 49.04 | − 0.74 |

| 22 | Cpa_mir-m1645 | UGGACCGUCCGAUCGCGUUCACGC | 83 | − 42.4 | − 51.08 | − 0.8 |

| 23 | Cpa_mir-m1648 | UUCUCUGGCGACUGGUUUUGC | 81 | − 44.1 | − 54.44 | − 0.83 |

| 24 | Cpa_mir-m1990 | GCUUACCGGGCCUGCUGACGUGGC | 76 | − 46.9 | − 61.71 | − 0.88 |

| 25 | Cpa_mir-m2256 | UUUCGGGACAGUCCGCGUGCG | 95 | − 48.2 | − 50.74 | − 0.98 |

| 26 | Cpa_mir-m2262 | GAUCAUGUGGUAGCUUCACC | 91 | − 41.8 | − 45.93 | − 0.97 |

| 27 | Cpa_mir-m2314 | CCCGGGUCGACGUGGUUUUGCC | 75 | − 42.3 | − 46.48 | − 0.98 |

| 28 | Cpa_mir-m2379 | AGGACUUCCUGGAAUUCCGGGACU | 75 | − 42.8 | − 57.07 | − 1 |

| 29 | Cpa_mir-m2511 | GUCCGAUCGUGCGCACACGG | 67 | − 41.6 | − 62.09 | − 0.87 |

| 30 | Cpa_mir-m2749 | UGGGACGUACGCACUAUGUGC | 83 | − 45.7 | − 55.06 | − 0.88 |

| 31 | Cpa_mir-m3042 | UGUGCACGCUUGAUCUAGGCCGU | 88 | − 53.4 | − 60.68 | − 0.83 |

| 32 | Cpa_mir-m3110 | CUGACCGGGGCUGCUGACGUG | 72 | − 43.2 | − 60 | − 0.82 |

| 33 | Cpa_mir-m3128 | UAUGUCUCUGAUUCUGUCAUC | 93 | − 41.6 | − 44.73 | − 1.39 |

| 34 | Cpa_mir-m3254 | UUGGGCCAUCCGAUCGCGCGCACG | 88 | − 43 | − 48.86 | − 0.68 |

| 35 | Cpa_mir-m3258 | AGAGAUCGAUGAACCGCUGCC | 98 | − 44.4 | − 45.31 | − 0.99 |

| 36 | Cpa_mir-m3284 | AGCGACAGAUGACACAGAACGAUAGA | 81 | − 20.8 | − 25.68 | − 0.55 |

| 37 | Cpa_mir-m3400 | CACGUGCUCCCCUUCUCCAAC | 88 | − 43.5 | − 49.43 | − 0.89 |

| 38 | Cpa_mir-m3590 | UGCCAAAGGAGAGUUGCCCUG | 94 | − 46.5 | − 49.47 | − 1.01 |

| 39 | Cpa_mir-m3812 | UGACGUGCCUGCUGACGUGG | 91 | − 43.7 | − 48.02 | − 0.74 |

| 40 | Cpa_mir-m3953 | CAAGGCUAUGGAAAUUCUAA | 80 | − 21.2 | − 26.5 | − 0.56 |

| 41 | Cpa_mir-m3967 | UGGUCAGGGCUGCUGACGUG | 77 | − 40.2 | − 52.21 | − 0.82 |

| 42 | Cpa_mir-m4000 | CUGACCGGGGCUGCUGACGUG | 72 | − 43.2 | − 60 | − 0.82 |

| 43 | Cpa_mir-m4028 | CGCACGGACGGCCUGAAUGAG | 92 | − 40.2 | − 43.7 | − 0.66 |

| 44 | Cpa_mir-m4265 | UGUCCGUGUGCGUGAGAUCUGG | 92 | − 44.4 | − 48.26 | − 0.75 |

| 45 | Cpa_mir-m4113 | CUGACGUGGCUGUUGAUGUGGCGC | 101 | 41.2 | 40.79 | 0.76 |

| 46 | Cpa_mir-m4268 | UGGAUCUUCUUCUCUGGCAAGGG | 99 | − 43.5 | − 43.94 | − 0.67 |

| 47 | Cpa_mir-m4298 | CGAAUCUGAGCCGUCCGAUCGCAC | 101 | − 40.7 | − 40.3 | − 0.65 |

| 48 | Cpa_mir-m4304 | CUGACCGGGGCUGCUGACGUG | 71 | − 43.6 | − 61.41 | − 0.82 |

| 49 | Cpa_mir-m4316 | GCACGCGGAUCGCCUAUGUGGCU | 96 | − 40.8 | − 41.63 | − 0.68 |

Phylogenetic tree analysis of novel C. papaya miRNAs

Sequence alignment was developed using the T-Coffee multiple sequence alignment (MSA) server and the evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method (Kumar et al. 2016). The optimal tree was generated with the sum of branch length of 36.6. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method, expressed in units of the number of base substitutions per site. This analysis involved 130 nucleotide sequences and removed all positions containing gaps and missing data. A total of 9 out of 49 novel miRNAs (Cpa_mir-m0016, Cpa_mir-m2379,Cpa_mir-m3128,Cpa_mir-m0440,Cpa_mirm3953,Cpa_mir-m3042, Cpa_mir-m3284, Cpa_mir-m3258, Cpa_mir-m0974 belonging to families Cpa-miR398, Cpa-miR8135, Cpa-miR159a, Cpa-miR8149,Cpa-miR8138, Cpa-miR8134, Cpa-miR8144, Cpa-miR8150, Cpa-miR408 respectively) were observed to be highly conserved in papaya family. The final refined phylogenetic tree is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of C. papaya shows the relationship between novel miRNA and reported miRNA of C. papaya miRNA family. Purple diamond indicates the identified novel miRNA

Human target prediction of known and novel miRNAs of C. papaya

The human target genes were predicted using the psRNATarget webserver for 1798 known and 49 novel C. papaya miRNAs. Most of the targets indicated the inhibition function as 'cleavage' and very few were classified in the 'translation' category. A total of 1643 and 383 targets were identified from known and novel miRNAs, respectively. The novel miRNA, Cpa_miR-m1403 mapped the maximum number of 233 targets, followed by Cpa-miRm0016 with 30 targets (Table 2). Overall, target genes were predicted for ~ 73% of known and ~ 78% of novel miRNAs.

Table 2.

List of potential targets genes and their inhibition type of identified novel miRNAs

| S. no | Novel miRNAs of Carica papaya | Type of inhibition | Target human genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cpa_mir-m1403 | Cleavage |

FAM227A, LRP8, HNF4A, SLC4A8, SCN2A, SLC12A2, BCLAF1, CASZ1, DGKG, PRDM7, ISPD, PLAG1, BEX4,PWWP2A, API5, IMPA1, FKBP5, ZEB2, CSRNP3, SLITRK4, VAMP4, LYPD6, BMPR1B, TMPRSS13, UNC5B, PRMT8, HAL, KCNJ3, AHNAK, CTGF, ELK4, HMGB2, KCNJ3, KIF3C, KPNA4, LAMP2, PRKCA, NR2C2, STAM, DENR, STBD1, BTAF1, CDC23, IRS1, TSPAN2, NFATC1, SPIN1, QKI, WWP2, MTF2, CD2AP, RABGAP1, TIMM10, FHOD1, DIEXF, VENTX, SV2B, SRGAP3, WDTC1, RTF1, SMCHD1, AMMECR1, PI15, FAM46A, ZNF562, SNRK, NRDE2, BLOC1S4, PLCXD1, ASH1L, AJAP1, FAM105A, USP53, PEAK1, KIAA0226L, TAOK1, RAI1, CALD1, WDR5B,NDFIP2,FAM160B1,TSEN34,IRX3,PLA2G4A,SH3TC2,FBXO9,SLC44A1,ZNF618,BMPER,KLHL23,TMEM196, PODN, NFATC1, NLRP8, WDR17, OPN5, WDR72, ADAMTS9, LONRF2, TMEM110, RASSF6, RPAIN, IGF2BP1, C16orf52, ATXN3, CELF5, SCAMP5, ZMYM2, QKI, KIT, GRIK3, SPOPL,TPM1, ITPRIPL2, NRF1, GLRA3, UNK, RELL1, TMEM192, NCOA7, CACFD1, AKIRIN1, SLC25A22, ANKRD44, CLRN1, IFRD1, EGR3, C18orf21, C18orf21, UBE2H, WISP1, CACFD1, FAM47E, STBD1, CLRN1, ZNF248, HOMER1, XTL3, IL1RAP, MATN1, PCK1, RBP3, SORT1, SPN, TFAM, TDGF1, ZNF264, BSN, AGPS, STK17B, HOMER1, CREB5, AQP3, ATXN3, ATF1, ACTR1A, LILRB2, SMC1AWDR3, MALT1, PCGF2, ZNF146, ZNF175, CASP8AP2, PITPNB, TLL2, WDR37, LEMD3, SLC7A11, ZNF585B, PDIK1L, VGLL2, CREBRF, FAM26E, OR2L13, PSME3,ZDHHC21, IL21R, IKZF3, ZBTB41, SRC, ZC3H6, GTF2H5, FAM174B, RAPH1, C4orf40ASCC3, ACSL4, AACS, WDR82, DNAL1, IRX2, CTTNBP2, DYNLL2, GPR82, NXPE3, ZFF4, KIAA0355, STARD8, DTX4, STK36, SELT, FAM120C, RIC8B, PARVA, CCDC91, SLC35E3, CCDC93, TM9SF3, NUFIP2, ZNF248, CACNA1I |

| Translation | EMP2, AGPS, ACSL4, SSH2, PIK3R1, PHLDA1, REEP3, L1CAM, CXADR, HOOK3 | ||

| 2 | Cpa_mir-m0016 | Cleavage | GRIN2A, FLT1, CHM, GSTM3, TTLL3, WIPI2, PHACTR2, PIRT, JAKMIP3, CRY2, HOGA1, AHCY, ARPC4-TTLL3, CALU, POU2F2, CLIC5, C20orf112, KLF7, ATG12, CA5A, EGF, POU2F2, IL18R1, ATG12, TESPA1, GIPC2, CRY2, HTR5A |

| 3 | Cpa_mir-m0063 | Cleavage | PAM, TFEC, ANGPT1, DDHD1, PDK4, ZNF280D, PCDH11Y, PXT1, DNAH12 |

| 4 | Cpa_mir-m0370 | Cleavage | ZNF99, NEURL1B, TSPAN5 |

| 5 | Cpa_mir-m0233 | Cleavage | PRC1, CBFA2T3, SCARA5 |

| 6 | Cpa_mir-m0440 | Cleavage | GRM5, PTCH1, ADAM22 |

| 7 | Cpa_mir-m0511 | Cleavage | C9orf47, ADCYAP1R1, GABPA, ARL11, SERPINF2 |

| 8 | Cpa_mir-m0749 | Cleavage | GPR55 |

| 9 | Cpa_mir-m0974 | Cleavage | EIF5AL1, DCC, CCNJL, C17orf103 |

| 10 | Cpa_mir-m1108 | Cleavage | KLF9, STAC, WNK1, DSN1 |

| 11 | Cpa_mir-m1285 | Cleavage | TRAPPC9, PFKL, RGS14 |

| 12 | Cpa_mir-m1285 | Cleavage | RGS14 |

| 13 | Cpa_mir-m1392 | Cleavage | ADAMTSL1 |

| 14 | Cpa_mir-m1414 | Cleavage | GABRA6, DENND2C, SPAG7, ADAMTS4, INSIG2, FKBP14, TEAD1, CHMP4C |

| 15 | Cpa_mir-m1481 | Cleavage | MBL2, CREM, PARG, SLC16A7, GAB2, ORC4, CREM, MYOZ3, PPP3R2 |

| 16 | Cpa_mir-m1590 | Cleavage | C1orf173, FASTKD2, FAM178A, RBM27, TXNDC17 |

| 17 | Cpa_mir-m4316 | Cleavage | PDCD6IP, DCLK1, COL15A1, ZBTB43, TECPR1, CLN8, FBXL18, ITPRIP |

| 18 | Cpa_mir-m4268 | Cleavage | SFMBT2, NCALD, KCNS1, MSR1, UCP3, ZDHHC9, RALGAPB |

| 19 | Cpa_mir-m4113 | Cleavage | PPM1A |

| 20 | Cpa_mir-m3953 | Cleavage | LYSMD1, PPP1R12A, LOC729020, HOXA7, CRISPLD1, EML5 |

| 21 | Cpa_mir-m3590 | Cleavage | ITGA4, KLF6, C22orf43 |

| 22 | Cpa_mir-m3400 | Cleavage | CACNB3, MID1IP1, KLHL26, PLEKHG1, ZXDC, C17orf107, NOS1, ILF3, ST8SIA4, PCNX, HPCAL4, TTC31, ILF3, GAB1 |

| 23 | Cpa_mir-m3128 | Cleavage | TSHZ2, DYNLT3, KIAA1549L, ITIH6 |

| 24 | Cpa_mir-m1648 | Cleavage | PKNOX2 |

| 25 | Cpa_mir-m1990 | Cleavage | C19orf53 |

| 26 | Cpa_mir-m2262 | Cleavage | NAT8L |

| 27 | Cpa_mir-m2314 | Cleavage | TSPAN33 |

| 28 | Cpa_mir-m2379 | Cleavage | RBMS3, TGM4, GET4, |

| 29 | Cpa_mir-m3042 | Cleavage | SIM1, PHC3 |

Gene ontology and functional enrichment of C. papaya target genes

Functional annotation was carried out using the Blast2GO program for known and novel miRNA-identified target genes. The Gene ontology results from known miRNA target genes indicated the involvement of 38% of genes in localization (GO: 0051179), response to stimulus (GO: 0050896), immune system process (GO: 0002376) and developmental process (GO: 0032502), 16% in molecular function and 8% in cellular components. On further analysis, majority of genes were associated in the molecular functions (GO: 0008152), translation regulatory activity (GO: 0045182), binding (GO: 0005488) and catalytic activity (GO: 0003824) (Fig. 3, Section A).

Fig. 3.

The representative bar graphs illustrate the functional annotation analysis of C. papaya regulated human target genes. A Gene ontology for known miRNAs performed at level 2 for three main categories (cellular component, molecular function, and biological process). B Gene ontology for novel miRNAs performed at level 2 for three main categories (cellular component, molecular function, and biological process)

In addition, gene ontology studies were performed adapting the same procedure used for known miRNA to understand the comprehensive network of genes modulated by novel miRNAs. A total of 383 targets were annotated, out of which only 247 were found to cover various molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components. Of genes involved in biological process, 120 genes were involved in cellular process (GO: 0009987), 32 in localization (GO: 0051179), 6 in signaling (GO: 0023052) and only one gene each were annotated as genes involved in growth (GO: 0040007), reproduction (GO: 0000003) and immune system response (GO: 0002376). Similarly, transcription regulator activity (GO: 0140110; 8 genes), catalytic activity (GO: 0003824; 99 genes), and binding (GO: 0005488; 93 genes) were the most represented GO terms. Moreover, the genes from the cell part (GO: 0110165) and membrane part (GO: 0032991) were the most represented among cellular component (Fig. 3, Section B).

Pathway analysis of predicted novel miRNAs targets

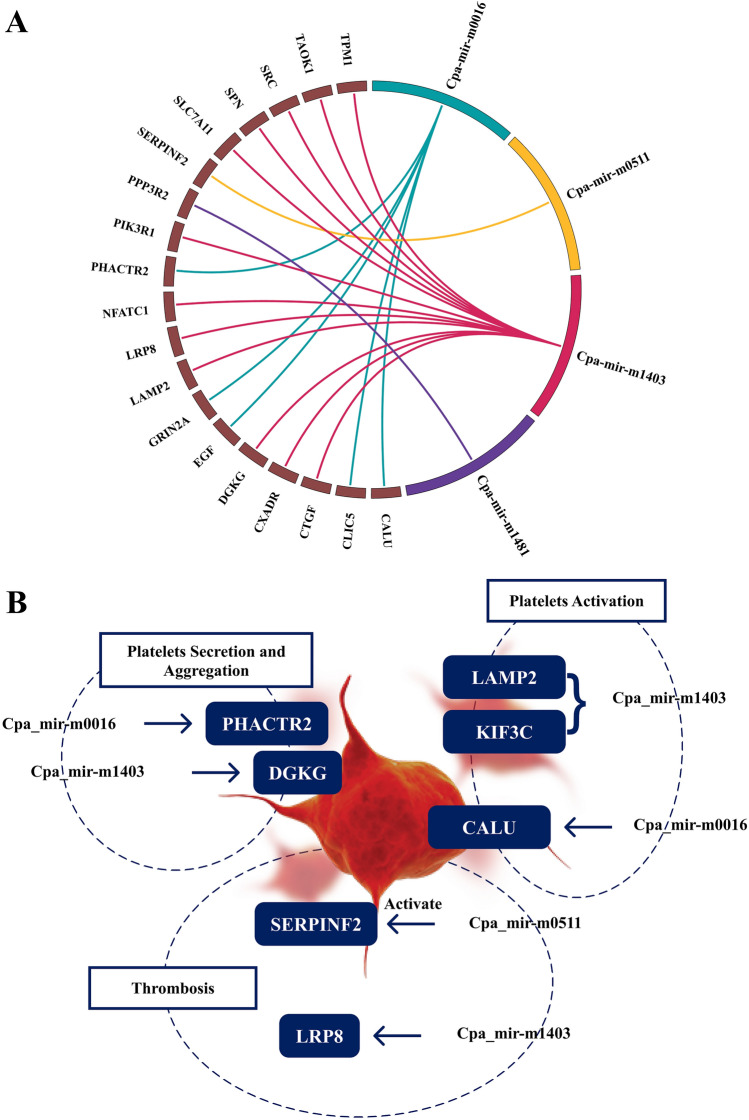

We further studied the novel miRNA targets and their potential role in functional annotation and pathways. Out of 383 gene targets, eight were related to transcription factors including TFEC, GABPA and ATF1 which are involved in ovarian cancer, breast cancer and carcinoma progression (Jin et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2016). The details of these targets are provided in Supplementary Material 4. SRC, one among the significant target genes, is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase and proto-oncogene involved in the MAPK signaling pathway and is highly activated in a wide variety of human cancers, such as pancreatic, colon, and breast cancer and Kaposi's sarcoma (Irby and Yeatman 2000). We also observed that 25% of genes were involved in various predominant pathways like WNT pathway, Nanog, ERK signaling, NF-kappa B, cAMP-dependent PKA, GPCR signaling cascade and pathways related to the response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+. Similarly, genes, such as PHACTR2, CALU, SERPINF2, LRP8, DGKG, CXADR, SPN and SLC7A11, participate in platelets activation, aggregation, and response to platelet cytosolic Ca2+.

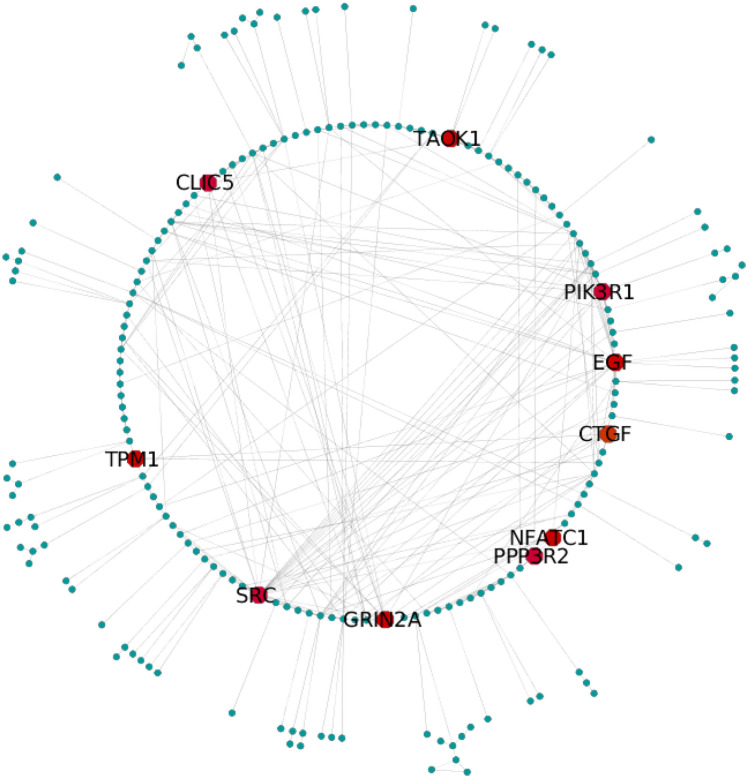

Network analysis and disease association of novel miRNA targets of C. papaya

Using cytohubba program, we could choose top ten hub genes among 383 target genes, viz. GRIN2A, CTGF, EGF, NFATC1, TAOK1, PPP3R2, PIK3R1, CLIC5, SRC and TPM1 scored 96 to 15 wherein the SRC gene secured the top rank followed by EGF (Fig. 4, Table 3). Nonetheless, these genes were participating in various downstream signaling pathways including PIP3 activation-based AKT signaling and GAB1 signalosome with a p value < 0.05. The identified genes are associated with various diseases categorized as mental illness, cancer, syndrome, diabetes, and other platelets disorder (Supplementary Material 4).

Fig. 4.

Gene network analysis showing association between significantly modulated genes. Top ten genes marked with red color have been detected from bottleneck method

Table 3.

Top hub nodes calculated through topological Analysis method

| MCC | DMNC | MNC | Degree | Bottleneck | Eccentricity | Closeness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRC | SRC | SRC | SRC | SRC | SRC | SRC |

| EGF | EGF | EGF | EGF | NFATC1 | PIK3R1 | EGF |

| CTGF | PIK3R1 | PIK3R1 | PIK3R1 | CLIC5 | NFATC1 | CTGF |

| PIK3R1 | CTGF | CTGF | CTGF | CTGF | CLIC5 | NFATC1 |

| NFATC1 | NFATC1 | NFATC1 | NFATC1 | PIK3R1 | EGF | CLIC5 |

| CLIC5 | TPM1 | TPM1 | TPM1 | TPM1 | CTGF | PIK3R1 |

| TPM1 | CLIC5 | CLIC5 | CLIC5 | EGF | GRIN2A | GRIN2A |

| PPP3R2 | PPP3R2 | PPP3R2 | PPP3R2 | PPP3R2 | TPM1 | TPM1 |

| GRIN2A | GRIN2A | GRIN2A | GRIN2A | GRIN2A | PPP3R2 | PPP3R2 |

| TAOK1 | TAOK1 | TAOK1 | TAOK1 | TAOK1 | TAOK1 | TAOK1 |

Discussion

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are well-known non-coding RNAs that play a major role in the regulation of gene expression in both plants and animals. For the first time in 2012, Zhang et al., reported that consumption of plant-derived miRNA168 regulates the expression gene in mammals (Zhang et al. 2012). Inspired by this finding, the cross-kingdom approach has drawn much attention in the scientific community regarding plant-derived miRNAs in mammals. miR2911 from honeysuckle was reported to inhibit the replication of influenza A virus, besides inhibiting the SARS-CoV-2 replication and accelerates the recovery process in the infected patients (Zhou et al. 2015, 2020). Our study employs the cross-kingdom approach to determine the prospective involvement of C. papaya-derived miRNAs in regulating human target genes that may have functional consequences in physiological and pathological situations, such as platelet disorder, cancer, and mental illnesses. Owing to its nutrient-rich fruit, enzymes, and bio-components, ethno-botanical and gene expression investigations have revealed that C. papaya is well suited for the treatment of different ailments and diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and immunomodulatory activities (Karunamoorthi et al. 2014). Researchers studied the miRNAs identified from a broad range of foods like fruit, leaves, meat, grains, and milk that regulate the gene expression in human. These miRNAs also have shown to serve as biomarkers for various pathological conditions like cardiovascular disorders, pancreatic cancer, and aid in liver cancer therapy (Khurana et al. 2021). Additionally, the bioavailability of exogenous miRNAs in the host depends on the source (Plant or Animal) and the pre-supplementation level. A number of studies have already reported that green leafy vegetables are rich in fibers, antioxidants, vitamins, and polyphenols. A similar study by Hou et al., in 2018 reported that miR156a and miR164a are abundantly expressed in green leafy veggies like spinach, lettuce and cabbage. These two miRNAs were observed to be stable in the serum when consumed orally (Hou et al. 2018). Henceforth, we hypothesized that papaya leaves which are consumed often due to their therapeutic qualities might have miRNAs that can be transferred in their stable forms into human hosts upon oral consumption. We used next-generation sequencing technology, Illumina HiSeq2500 to perform high-throughput sequencing of C. papaya young leaves, followed by bioinformatics analysis to identify known and novel miRNAs along with their putative targets in humans. Forty-nine novel miRNAs were identified that targeted 383 human genes, among which Cpa_miR-m1403 was found to regulate the highest number of target genes, i.e., 233 followed by Cpa_miR-m0016 with 30 target genes. Target annotation using the Blast2GO program unveiled that most of the targets were significantly enriched in the developmental processes, growth, localization, and signaling. Pathway analysis of these targeted human genes showed their participation in various predominant signaling cascades, including GPCR and ERK signaling, and response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+ (Supplementary Material 4). Additionally, novel miRNAs like Cpa-mir-m0016, Cpa-mir-m0511, Cpa-mir-m1403 and Cpa-mir-m1481 target genes have direct association with pathological conditions like mental illnesses, diabetes, and cancer.

In light of the primary functions of human gene targets, we investigated the probable roles of novel miRNAs (Cpa miR-m1403 and Cpa miR-m0016) in two diseases, dengue and cancer, as well as in mental disorders. Interestingly, we observed genes including PHACTR2, CALU, SERPINF2, LRP8, DGKG, CXADR, SPN, SLC7A11, and LAMP2 participate in platelets activation, aggregation, response to platelet cytosolic Ca2+. Thrombosis occurs due to blood clot formation wherein plasminogen activator inhibitor plays a leading role, and the SERPINF2 target gene acts as a potent plasmin inhibitor. It is anticipated that Cpa_miR-m1403 and Cpa_miR-m051 may regulate the expression of SERPINF2 and LRP8 genes in humans. Since SERPINF2 is one of the putative targets of Cpa_miR051, it would be interesting to explore the probability of this interaction in the activation of plasmin and subsequent reduction of circulating fragments. Variations in LRP8 gene can alter thrombosis, which presents a scenario in which clot formation could be affected in humans (Robertson et al. 2009). Similarly, PHACTR2, DGKG and SPN play a pivotal role in platelet secretion, activation and development, respectively (Fig. 5B) (Gorski et al. 2019). While, LAMP2 is a membrane glycoprotein that plays a vital role in activation-dependent platelet surface glycoprotein (Saboor et al. 2013). Che et al., 2017 showed that Mir27a is a critical regulator of autophagy in chronic brain hypo-perfusion (CBH) that affects LAMP2 protein expression at the post-transcriptional level (Che et al. 2017). SLC7A11 is a light chain subunit that can be triggered by drugs and glutamate and can cause ferroptosis (iron-dependent programmed cell death) in platelets and macrophages. However, the activity of SLC7A11 can be influenced by numerous factors that modulate GSH (glutathione), resulting in SLC7A11 suppression, which can cause ferroptosis (Fig. 5B) (Tang et al. 2020). Evidence suggests that Cpa_mir-m1403 can regulate SRC, the most predominant proto-oncogene highly expressed in distinct cancer types, such as breast, colon, pancreatic and gastric cancers (Irby and Yeatman 2000). It was demonstrated earlier that mir-23b mediated the inhibition of the SRC-AKT pathway leading to cisplatin resistance in chondrosarcoma cells (Huang et al. 2017). Further in vitro investigations are needed to better elucidate the role of novel Cpa_mir-m1403 in modulating the SRC gene expression. We also noted that 29% of the human gene targets in this study were implicated in brain diseases, which is consistent with previously established functions of miRNA-mediated gene regulation mechanisms in anxiety, schizophrenia, and psychiatric illnesses (Murphy and Singewald 2019; Hunsberger et al. 2009).

Fig. 5.

A Four novel miRNA and their human targets are depicted by circos diagram, and their connection is shown by respective color links. B Novel miRNAs and their targeted genes involved in platelet disorders

One of the noteworthy findings of this study was the top ten hub genes deduced from the interaction and significance of nodes in the network; GRIN2A, CTGF, EGF, NFATC1, TAOK1, PPP3R2, PIK3R1, CLIC5, SRC, and TPM1 constituted influential role in pathway involvement and biological processes (Fig. 4). It was reported that in breast cancer and melanoma, oncogene activation caused by GRIN2A, SRC, and TPM1 resulted in a severe reduction in patient survival (D'mello et al. 2014; Botezatu et al. 2016). It is expected that both novel C. papaya miRNAs, Cpa_mir-m0016 and Cpa_mir-m1403, will likely control the expression of activated oncogenes by inhibiting the progression of malignancy. This cross-kingdom analysis showed that the gene PIK3R1, a prominent regulator of isomer PI3K may govern the PI3K pathway, which has documented evidence of profound implications in breast cancer and as an independent prognostic marker (Cizkova et al. 2013). Few miRNAs have previously been shown to reduce PIK3R1 overexpression responsible for HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) proliferation. It will be exciting to elucidate how Cpa_mir-m1403 regulates the PIK3R1 expression, which has a significant role in the modulation of tumor growth (Huang et al. 2015), and further in vitro studies are needed in this direction to this hypothesis. Overall, top hub genes are plausible regulators of signaling pathways and responsible for modulating various downstream targets by interacting with various protein complex networks.

We earlier reported a cross-kingdom analysis to identify novel C. papaya miRNAs from EST sequences available in the NCBI database and studied their putative role in regulating various types of cancer and platelet regulatory pathways. The novel miRNAs, cpa-miR6034 and cpa-miR3629b belong to two unique miRNA families EX294530.1 and EX271034.1, and targeted 38 human targets (Nurowidah 2019). Unfortunately, these EST sequences are of mixed type and sequenced from C. papaya leaf, root, stem, flower, fruit, and seed, published as one of the sequence entries of papaya draft genome by Alam and his co-workers (2008) (Ming et al. 2008). We could not discern which plant part these two novel miRNAs belong to. Since the young leaf samples of C. papaya are sequenced in this study, we can conclusively claim that the identified novel miRNAs originate exclusively from the plant leaves. A thorough search for C. papaya leaf sequence reads in the NCBI SRA database linked to 3 Bio Projects (as of 28/10/2021) dealing with the study of gene expression patterns in freeze–thaw treated C. papaya leaves, gene expression profiling for immune response infected with Papaya leaf-distortion mosaic virus, and effect of miRNAs in leaf juice for blood platelet count (An et al. 2020). Although numerous C. papaya SRA sequence reads are publicly available, a single study on miRNA identification has been published so far, which reported C. papaya-specific miR-c4, which was predicted to regulate the ethylene signaling pathway (Liang et al. 2013). On the other hand, C. papaya-derived miRNAs from fruit parts obtained from high-throughput sequencing were investigated for their role in the ripening and developmental stages of the fruit but not devoted to human disease association (Cai et al. 2021). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first such effort made to derive miRNAs from small RNA sequencing data and explore their role in human gene regulations using a cross-kingdom approach. The present study also augments the knowledge of novel C. papaya miRNAs that can be exploited further in biochemical and clinical studies. Although this cross-kingdom analysis utilizes sequence homology techniques and literature-driven data to sketch the possible regulatory mechanism of selected novel C. papaya miRNAs in certain human target genes, it is critical to validate these research hypotheses through wet-lab experiments to thoroughly comprehend the role of C. papaya miRNAs in controlling or alleviating disease conditions, with implications in dengue, cancer, and mental illness as our study lacks more in vivo and in vitro evidence.

Conclusion

Over 30 million sequence reads were generated from a small RNA library to explore the role of miRNA from C. papaya young leaf and effectively identify the known and novel miRNAs. A total of 1798 known and 49 novel C. papaya miRNAs were identified, which were further assessed for their cross-kingdom regulation in human gene targets. Novel miRNAs, such as Cpa_miR-m1403 and Cpa_miR-m0016, are predicted to target 70% of genes out of 383 predicted human targets. The identified target genes engaged in various signaling pathways viz. WNT, Nanog, MAPK-AKT, ERK signaling, platelet activation and aggregation. The network interaction study revealed top hub genes, namely GRIN2A, CTGF, EGF, NFATC1, TAOK1, PPP3R2, PIK3R1, CLIC5, SRC, and TPM1, which were involved in various signaling pathways and acted as oncogenes. This cross-kingdom study elucidates possible gene target-disease association in diabetes, numerous types of cancers, mental illnesses, and platelet disorders. Collectively, the human genes targeted by C. papaya-derived novel miRNAs may unravel the biological role of these miRNAs in regulating numerous downstream signaling cascades. However, further in vitro validation using techniques such as RNA interference is required to promote the application of the cross-kingdom approach in clinical interventions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge GSBTM, DST, and Government of Gujarat for providing Bioinformatics Node facility. We acknowledge GUJCOST, DST, and Government of Gujarat for super-computing facility. We also like to acknowledge Sukanya Rawal for her technical support and Dr. Prasanth Kumar for proof-reading the manuscript. We also like to acknowledge Kaval Reddy Prassavi from IISc, Bangalore for helping us with grammatical errors and Naman Mangukia acknowledges the Prime Minister's Fellowship award from Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), Department of Science and technology (DST), Government of India and the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII).

Abbreviations

- C. papaya

Carica papaya

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- MFE

Minimal free energy

- MFEI

Minimal free energy index

- AMFE

Adjust minimal free energy

- MCC

Maximal clique centrality

- DMNC

Density of maximum neighborhood component

- MNC

Maximum neighborhood component

- PHACTR2

Phosphatase and actin regulator 2

- CALU

Calumenin

- SERPINF2

Serpin family F member 2

- LRP8

LDL receptor-related protein 8

- DGKG

Diacylglycerol kinase gamma

- CXADR

Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor

- SPN

Sialophorin

- SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member

- LAMP2

Liposomal-associated membrane protein 2

- GRIN2A

Glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2A

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- NFATC1

Nuclear factor of activated T cells 1

- TAOK1

TAO kinase 1

- PPP3R2

Protein phosphatase 3 regulatory subunit B, beta

- PIK3R1

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1

- CLIC5

Chloride intracellular channel 5

- SRC

Non-receptor tyrosine kinase

- TPM1

Tropomyosin 1

- WNT

Wingless-related integration site

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Financial Assistance Programme—Gujarat State Biotechnology Mission, Gujarat, India [grant number GSBTM/FAP/1443] and Department of Science and Technology [grant number GSBTM/MD/JDR/1409/2017-18].

Availability of data and material

The supplementary data are provided in Supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors approval

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

The manuscript does not contain experiments using animals and human.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad N, Fazal H, Ayaz M, Abbasi BH, Mohammad I, Fazal L. Dengue fever treatment with Carica papaya leaves extracts. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1(4):330–333. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An N, Lv J, Zhang A, Xiao C, Zhang R, Chen P. Gene expression profiling of papaya (Carica papaya L.) immune response induced by CTS-N after inoculating PLDMV. Gene. 2020;755:144845. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S (2010) FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

- Aravind G, Bhowmik D, Duraivel S, Harish G. Traditional and medicinal uses of Carica papaya. J Med Plants Stud. 2013;1(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aryal R, Yang X, Yu Q, Sunkar R, Li L, Ming R. Asymmetric purine-pyrimidine distribution in cellular small RNA population of papaya. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botezatu A, Iancu IV, Popa O, Plesa A, Manda D, Huica I, Badiu C (2016) Mechanisms of oncogene activation. In: New aspects in molecular and cellular mechanisms of human carcinogenesis. InTech, London

- Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Wu Z, Hao Y, Liu Y, Song Z, Chen W, Zhu X. Small RNAs, degradome, and transcriptome sequencing provide insights into papaya fruit ripening regulated by 1-MCP. Foods. 2021;10(7):1643. doi: 10.3390/foods10071643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che H, Yan Y, Kang XH, Guo F, Yan ML, Liu HL, Ai J. MicroRNA-27a promotes inefficient lysosomal clearance in the hippocampi of rats following chronic brain hypoperfusion. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(4):2595–2610. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zen K, Zhang CY. Reply to Lack of detectable oral bioavailability of plant microRNAs after feeding in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(11):967–969. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Yen MC, Chen FW, Wu LY, Yang SJ, Kuo PL, Hsu YL. Knockdown of GA-binding protein subunit β1 inhibits cell proliferation via p21 induction in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2018;53(2):886–894. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8(4):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S4-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin AR, Fong MY, Somlo G, Wu J, Swiderski P, Wu X, Wang SE. Cross-kingdom inhibition of breast cancer growth by plant miR159. Cell Res. 2016;26(2):217–228. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizkova M, Vacher S, Meseure D, Trassard M, Susini A, Mlcuchova D, Bièche I. PIK3R1 underexpression is an independent prognostic marker in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization, and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’mello SAN, Flanagan JU, Green TN, Leung EY, Askarian-Amiri ME, Joseph WR, Kalev-Zylinska ML. Evidence that GRIN2A mutations in melanoma correlate with decreased survival. Front Oncol. 2014;3:333. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Zhuang Z, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W49–W54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson B, Zhang Y, Petrick JS, Heck G, Ivashuta S, Marshall WS. Lack of detectable oral bioavailability of plant microRNAs after feeding in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(11):965–967. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas DV, Bartel B. MicroRNA regulation of gene expression in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7(5):512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, D’Eustachio P. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D649–D655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadhavi H, Patel M, Mangukia N, Shah K, Bhadresha K, Patel SK, Pandya HA. Transcriptome-wide miRNA identification of Bacopa monnieri: a cross-kingdom approach. Plant Signal Behav. 2020;15(1):1699265. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1699265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski MM, Lecchi A, Femia EA, La Marca S, Cairo A, Pappalardo E, Peyvandi F. Complications of whole-exome sequencing for causal gene discovery in primary platelet secretion defects. Haematologica. 2019;104(10):2084. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.204990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):439–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Kay MA. How do miRNAs mediate translational repression? Silence. 2010;1(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MA, Hitam S, Ahmed SHI. Pharmacological and toxicological activities of the extracts of papaya leaves used traditionally for the treatment of diarrhea. J King Saud Univ-Sci. 2020;32(1):962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou D, He F, Ma L, Cao M, Zhou Z, Wei Z, Jiang X. The potential atheroprotective role of plant MIR156a as a repressor of monocyte recruitment on inflamed human endothelial cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;57:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XP, Hou J, Shen XY, Huang CY, Zhang XH, Xie YA, Luo XL. Micro RNA-486-5p, which is downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, suppresses tumor growth by targeting PIK3R1. FEBS J. 2015;282(3):579–594. doi: 10.1111/febs.13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GL, Liao D, Chen H, Lu Y, Chen L, Li H, He Z. The protein level and transcription activity of activating transcription factor 1 is regulated by prolyl isomerase Pin1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(12):e2571–e2571. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Chen J, Yang MS, Tang YJ, Pan F. Inhibition of Src by microRNA-23b increases the cisplatin sensitivity of chondrosarcoma cells. Cancer Biomark. 2017;18(3):231–239. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger JG, Austin DR, Chen G, Manji HK. MicroRNAs in mental health: from biological underpinnings to potential therapies. NeuroMol Med. 2009;11(3):173–182. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(2):99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19(49):5636–5642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha N, Mangukia N, Patel MP, Bhavsar M, Gadhavi H, Rawal RM, Patel SK. Exploring the MiRnome of Carica papaya: a cross kingdom approach. Gene Rep. 2021;23:101089. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Shang Y, Yan H, Hao J. High levels of TFEC expression associated with aggressive clinical features in ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018;11(10):10692–10702. [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunamoorthi K, Kim HM, Jegajeevanram K, Xavier J, Vijayalakshmi J. Papaya: a gifted nutraceutical plant-a critical review of recent human health research. Cellmed. 2014;4(1):2–1. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana P, Gupta A, Varshney R (2021) Diet-derived exogenous miRNAs as functional food components: facts and new perspectives. 10.20944/preprints202102.0541.v1

- Kruszka K, Pieczynski M, Windels D, Bielewicz D, Jarmolowski A, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Vazquez F. Role of microRNAs and other sRNAs of plants in their changing environments. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(16):1664–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Kumar S, Ayachit G, Bhairappanavar SB, Ansari A, Sharma P, Das J. Cross-kingdom regulation of putative miRNAs derived from happy tree in cancer pathway: a systems biology approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1191. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang Z, Liu F, Vongsangnak W, Jing Q, Shen B. Performance comparison and evaluation of software tools for microRNA deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(10):4298–4305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Xu R, Li N. MicroRNAs from plants to animals, do they define a new messenger for communication? Nutr Metab. 2018;15(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12986-018-0305-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Yang J, Yang Y, Liu J, Li H, Li R, He K. A timely review of cross- kingdom regulation of plant-derived microRNAs. Front Genet. 2021;12:702. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.613197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, Li Y, He H, Wang F, Yu D. Identification of miRNAs and miRNA-mediated regulatory pathways in Carica papaya. Planta. 2013;238(4):739–752. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1929-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libri V, Miesen P, van Rij RP, Buck AH. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and turnover by animals and their viruses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(19):3525–3544. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohsoonthorn P, Danvivat D. Colorectal cancer risk factors: a case-control study in Bangkok. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1995;8(2):118–122. doi: 10.1177/101053959500800211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loong SNK, Mishra SK. Unique folding of precursor microRNAs: quantitative evidence and implications for de novo identification. RNA. 2007;13(2):170–187. doi: 10.1261/rna.223807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar-Aguilar F, Arreola-Triana A, Mata-Cardona D, Gonzalez-Villasana V, Rodríguez-Padilla C, Reséndez-Pérez D. Evidence of transfer of miRNAs from the diet to the blood still inconclusive. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9567. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham NR, Zuker M. UNAFold. In: Keith JM, editor. Bioinformatics. Totowa: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cut adapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Embnet J. 2011;17(1):10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ming R, Hou S, Feng Y, Yu Q, Dionne-Laporte A, Saw JH, Alam M. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus) Nature. 2008;452(7190):991–996. doi: 10.1038/nature06856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CP, Singewald N. Behavioral neurogenomics. Cham: Springer; 2019. Role of microRNAs in anxiety and anxiety-related disorders; pp. 185–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurowidah A (2019) The potency of Carica papaya L. seeds powder as anti-obesity ‘coffee’ drinks. In: IOP conference series: materials science and engineering, vol 515(1), p 012098. IOP Publishing. 10.1088/1757-899X/515/1/012098

- O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Walpole C, Cabot PJ, Shaw PN, Batra J, Hewavitharana AK. Selective anti-proliferative activities of Carica papaya leaf juice extracts against prostate cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;89:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Mangukia N, Jha N, Gadhavi H, Shah K, Patel S, Rawal R. Computational identification of miRNA and their cross-kingdom targets from expressed sequence tags of Ocimum basilicum. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(3):2979–2995. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Patel S, Mangukia N, Patel S, Mankad A, Pandya H, Rawal R. Ocimum basilicum miRNOME revisited: a cross kingdom approach. Genomics. 2019;111(4):772–785. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrò S, Matic I, Colizzi V, Galgani A. The microRNA analysis portal is a next-generation tool for exploring and analyzing miRNA-focused data in the literature. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapakse S, de Silva NL, Weeratunga P, Rodrigo C, Sigera C, Fernando SD. Carica papaya extract in dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2678-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Coller J. Pausing on polyribosomes: make way for elongation in translational control. Cell. 2015;163(2):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JO, Li W, Silverstein RL, Topol EJ, Smith JD. Deficiency of LRP8 in mice is associated with altered platelet function and prolonged time for in vivo thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2009;123(4):644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboor M, Ayub Q, Samina Ilyas M. Platelet receptors; an instrumental of platelet physiology. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(3):891. doi: 10.12669/pjms.293.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad AFA, Kamaroddin MF, Sajad M. Cross-kingdom regulation by plant microRNAs provides novel insight into gene regulation. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(1):197–211. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar S, Shafurah S, Hasan Shaari NS, Rajikan R, Rajab NF, Golkhalkhali B, Zainuddin ZM. Roles of diet, lifetime physical activity and oxidative DNA damage in the occurrence of prostate cancer among men in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(3):605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel EM, Salemi JL, Villa LL, Ferenczy A, Franco EL, Giuliano AR. Dietary consumption of antioxidant nutrients and risk of incident cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118(3):289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi LP, Kambara H, Chen YA, Nishimura Y, Moriishi K, Okamoto T, Mizuguchi K. Understanding the biological context of NS5A–host interactions in HCV infection: a network-based approach. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(6):2537–2551. doi: 10.1021/pr3011217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MM. Ascorbic acid, vitamin A, and mineral composition of banana (Musa sp.) and papaya (Carica papaya) cultivars grown in Hawaii. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19(5):434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2006.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Mei J, Ren G. Plant microRNAs: biogenesis, homeostasis, and degradation. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:360. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogiraj V, Goyal PK, Chauhan CS, Goyal A, Vyas B. Carica papaya Linn: an overview. Int J Herbal Med. 2014;2(5):01–08. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Wang Q, Pan X. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in animals and plants. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(2):279–289. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hou D, Chen X, Li D, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Zhang CY. Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 2012;22(1):107–126. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Li X, Liu J, Dong L, Chen Q, Liu J, Zhang CY. Honeysuckle-encoded atypical microRNA2911 directly targets influenza A viruses. Cell Res. 2015;25(1):39–49. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou LK, Zhou Z, Jiang XM, Zheng Y, Chen X, Fu Z, Yi Y. Absorbed plant MIR2911 in honeysuckle decoction inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and accelerates the negative conversion of infected patients. Cell Discov. 2020;6(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00197-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K, Liu M, Fu Z, Zhou Z, Kong Y, Liang H, Chen X. Plant microRNAs in larval food regulate honeybee caste development. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(8):e1006946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The supplementary data are provided in Supplementary material.