Abstract

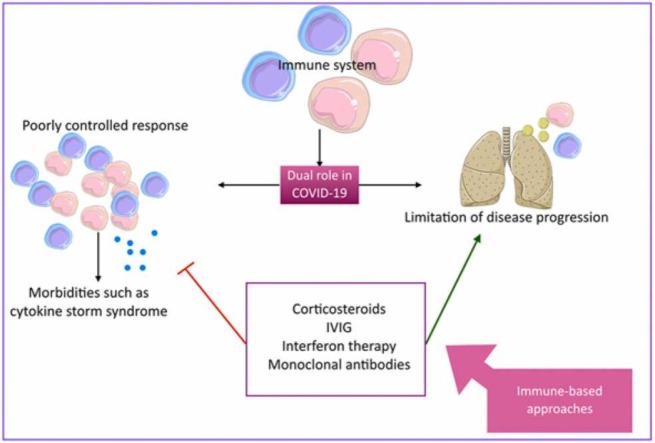

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a member of the Coronaviridae family. On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) has named the newly emerged rapidly-spreading epidemic as a pandemic. Besides the risk-reduction measures such as physical and social distancing and vaccination, a wide range of treatment modalities have been developed; aiming to fight the disease. The immune system is known as a double-edged sword in COVID-19 pathogenesis, with respect to its role in eliminating the pathogen and in inducing complications such as cytokine storm syndrome. Hence, immune-based therapeutic approaches have become an interesting field of COVID-19 research, including corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), interferon therapy, and more COVID-19-specific approaches such as anti-SARS-CoV-2-monoclonal antibodies. Herein, we did a comprehensive review on immune-based therapeutic approaches for COVID-19.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS, Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, ARDS, Pandemic, Pneumonia, Immune, Immunotherapy, Corticosteroids, IVIG, Interferon, Monoclonal antibody

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a viral disease caused by a member of the Coronaviridae family, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), has caused one of the greatest global pandemics, as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 [1]. Lung epithelium damage, hypercoagulability, and vascular leak lead to an important clinical manifestation, named acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Patients with previously diagnosed hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes are highly susceptible to ARDS [2]. As of 20 March 2022, more than 468 million confirmed cases and more than 6 million deaths have been reported [3]. As the main route of COVID-19 transmission is via respiratory droplets, social distancing is one of the most important measures for controlling the spread of the virus [4]. In addition to social distancing, developing effective vaccines could be a potent tool in limiting the disease spread and lowering the disease burden [1]. Amongst a variety of treatment approaches, immunotherapy has become an interesting option for COVID-19, although, the treatment results closely depend on choice of the right patient and right timing of drug administration [5]. Herein, we did a comprehensive review on immune-based therapeutic approaches for COVID-19.

2. COVID-19

Coronaviruses, a genus from Coronaviridae family, are pleomorphic, enveloped, positive sense ssRNA viruses, involved in respiratory tract infections [6], [7]. Members of this genus cause a wide range of respiratory complications ranging from mild respiratory illnesses, as in HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1 infections, to more severe diseases, such as SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2, and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [8].

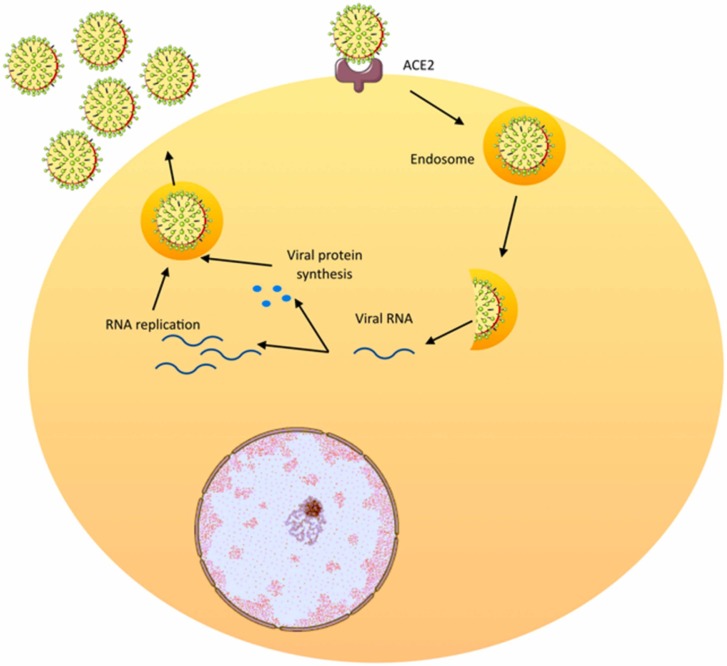

The viral genome and its surrounding nucleoprotein are wrapped by the viral envelope. The envelope contains structural proteins, matrix protein and spikes [6]. Attachment of SARS-CoV-2 to the cell surface is mediated via interactions between the spike protein and the angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) on the host cell’s surface [9]. The mechanism of viral pathogenesis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cellular mechanism of coronavirus pathogenesis.

The pathophysiology of COVID-19 is divided into four stages; asymptomatic stage, upper respiratory tract involvement, lower respiratory tract involvement, and ARDS/ multi organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [7]. The pathophysiological, clinical, and immunological characteristics of these stages are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and immunological characteristics of COVID-19 disease stages( IP-10 =interferon-inducible protein 10, MIG=monokine induced by interferon-γ, IL-8 =interleukin-8, MCP=Monocyte chemoattractant protein, IL-6 =interleukin 6, TNF=tumor necrosis factor, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, CRP=c-reactive protein).

| Stage | Pathophysiology | Clinical manifestations | Immunological characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic stage | Virus enters the nasal ciliated epithelial cells via ACE2 and TMPRSS2 | Asymptomatic | Mild innate response | [7], [11], [12], [13] |

| Upper respiratory tract involvement | Presence of virus in sputum | Cough, sore throat | Strong innate response, higher levels of IP-10, MIG, IL-8, MCP | [7], [14], [15] |

| Lower respiratory tract involvement | Virus-associated damage in alveolar cells (mostly pneumocyte II), apoptosis and death in pneumocytes. Alveolar macrophages are also targeted by viruses. | histological findings including hyaline membrane, alveolar damage, pneumocyte II hyperplasia, consolidation | Aggravated immune response (especially T cells), cytokine storm, higher levels of IL-6, TNF | [7], [16], [17], [18], [19] |

| ARDS/MODS | hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like cytokine storm | High cytokine levels, unremitting fever, high ferritin levels, cytopenia, multi-organ damage | Higher levels of ferritin, IL-6, LDH, D-dimer, CRP | [7], [17] |

Also, Turk et al. categorized clinicobiological aspects of the disease into three phases; asymptomatic/pre-symptomatic phase, propagating phase (mild/moderate/severe), and complicating phase (impaired/disproportionate and/or defective immunity) [10].

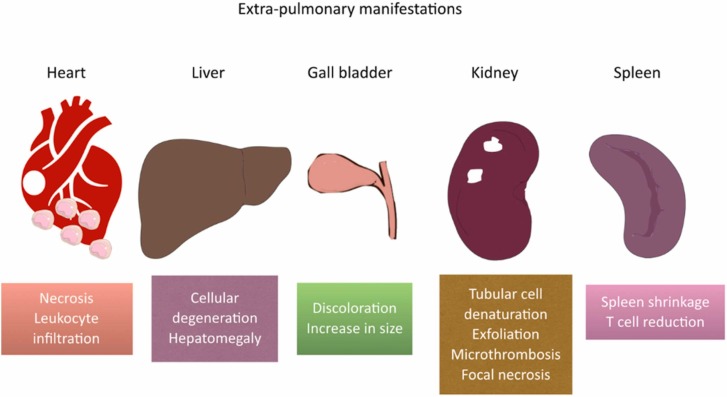

The pathological manifestations of the disease are mostly noticeable in the lung tissue, including hyaline membrane formation, accumulation of serous, exudate (mostly monocytes and macrophages), and fibrin in alveoli, and hemorrhagic infarction [20], [21]. Moreover, inclusion bodies, proliferation, and detachment has been spotted in pneumocyte II cells [22]. Studies on the alveolar septa shows edema, hyperemia, mononuclear cell infiltration, and hyaline thrombose formation [20]. On the other side, some extrapulmonary manifestations have been spotted in spleen (shrinkage, fewer number of T cells), heart (necrosis, leukocyte infiltration), liver (cellular degeneration, hepatomegaly), gall bladder (discoloration to dark-red, volume increase), and kidneys (tubular cell denaturation, and exfoliation, microthrombi, focal necrosis) [8]. Fig. 2 illustrates these extrapulmonary manifestations.

Fig. 2.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19.

The extent of abnormalities in chest X-ray (CXR) imaging is of diagnostic and prognostic importance and indicates the severity of the disease [23]. In more than 80% of the cases, the early stage of the disease is characterized by a bilateral multi-lobar ground-glass opacity, mainly distributed in middle-lower lungs [24], [25], [26]. In progressive and peak phases, these abnormalities increase in size, along with the appearance of interlobar septal thickening and consolidations. After the 14th day of illness, the radiological abnormalities gradually disappear [23]. In some cases, despite the viral clearance and resolution of the symptoms, some long-term sequelae such as progressive fibrotic abnormalities develop [27].

Laboratory indicators such as serological and molecular indices could be helpful in COVID-19 diagnosis, which are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Molecular and serological findings in COVID-19 (AST=aspartate amino transferase, ALT=alanine amino transferase, LDH=lactate dehydrogenase, ESR=erythrocyte sedimentation rate, RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction). * Cytokines including: IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, GM-CSF, MCP-1, MIP-1 α, TNF-α, and basic FGF.

| Tests | Findings in patients | References |

|---|---|---|

| Blood leukocyte count | Normal / decreased | [28] |

| Blood lymphocyte count | Decreased | [28] |

| Liver function tests (AST and ALT levels) | Decreased (in half the cases) | [29] |

| Creatine kinase | Decreased | [29] |

| LDH | Decreased | [29] |

| CRP | Increased | [30] |

| ESR | Increased | [30] |

| Cytokine levels * | Increased | [8] |

| RT-PCR | Presence of virus in pharyngeal swabs, blood, stool | [31] |

Management of COVID-19 patients involves both general supportive care and pharmacological treatment [8]. Supportive measures include, bed rest and temperature control in patient’s environment. Furthermore, monitoring oxygen saturation, liver and kidney function, electrolyte balance, and blood analyses such as complete blood count, c-reactive protein (CRP), and coagulation state are carried out [32]. In some cases, high-flow oxygen or oxygen-hydrogen mixtures (H2/O2: 66.65/33.39%) and rehydration therapy including IV fluid administration could be helpful [8], [33].

The effectiveness of some antiviral drugs such as lopinavir/ritonavir, oseltamivir, and ribavirin have been reported [34], [35], [36]. Arbidol, chloroquine, and interferon (IFN)-α had been used in Wuhan outbreak and in vitro studies demonstrated their effect on viral load reduction [37], [38], [39]. Management of critically ill patients, include respiratory and circulatory supportive care, oxygen therapy and intubation in some cases, besides the preventive and therapeutic measures for secondary complications and infections [8].

3. Corticosteroids

3.1. Mechanism of action

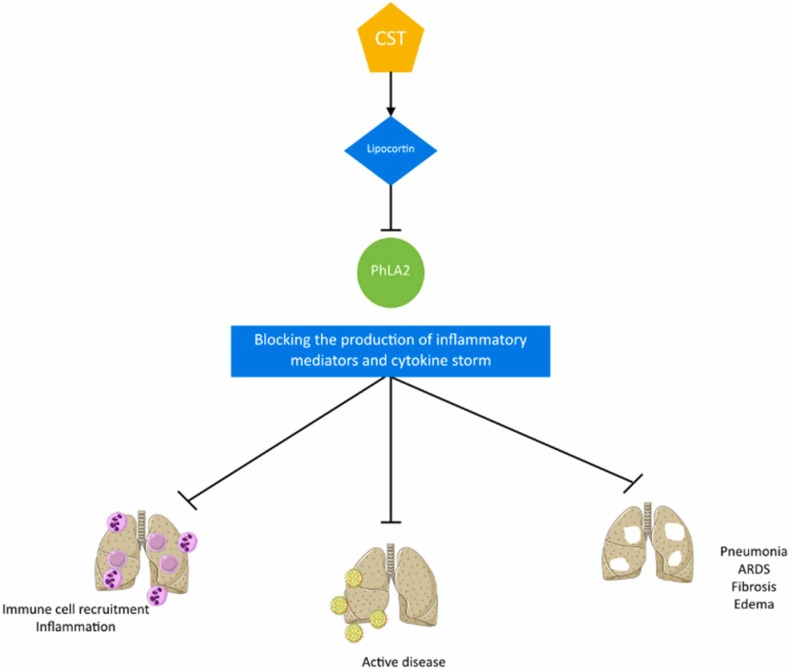

Corticosteroids are a class of substances, either synthetic or naturally expressed in adrenal cortex, which have a wide range of effects on the immune system, inflammation, stress response, metabolism, body fluids, and electrolytes [41]. Corticosteroids induce the production of lipocortin, which inhibits phospholipase A2, an essential enzyme for the production of inflammatory mediators [42].

In most COVID-19 cases, mortality is a result of exaggerated immune response against the infection. Corticosteroids control such responses and subsequently, decrease the time on mechanical ventilations, period of residence in intensive care unit (ICU), and mortality rate in COVID-19 patients [43].

Fig. 3 illustrates the mechanism of corticosteroids’ effect of COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of corticosteroids' effect on COVID-19 (CST=corticosteroid, PhLA2 =phospholipase A2, ARDS= acute respiratory distress syndrome).

3.2. Administration indications and clinical findings

During the SARS outbreak in 2003, corticosteroids, alone or in combination with ribavirin, were extensively used [44], [45]. In the current pandemic, a variety of studies have shown the efficacy of corticosteroids in different stages of COVID-19 infection; the results of these studies are summarized in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Recent studies on efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in COVID-19 patients. (MP=methylprednisolone, DX=dexamethasone, CI=confidence interval).

| Intervention | Dosage | Population | Study design | Primary outcome | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylprednisolone/methylprednisolone + tocilizumab | MP 250 mg day 1, 80 mg days 2–5 tocilizumab 8 mg/kg single dosage | Severe COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome | Controlled clinical trial (CHIC study) | > =2 stages improvement on a 7 item WHO endorsed scale for trials in patients with severe influenza pneumonia, or discharge from hospital | 79% more probability of reaching primary outcome, 65% less mortality, and 71% less invasive mechanical ventilation in treatment group in comparison with controls | [48] |

| Hydrocortisone | 200 mg daily for 7 days | COVID-19 patients receiving > =10 L/min oxygen or on mechanical ventilation | Randomized controlled clinical trial (COVID STEROID study) | days without life support at day 28 | Number of days alive without life support at day 28 in treatment and controls groups were 7 and 10 days respectively mortality rate in treatment and controls groups were 6/16 and 2/14 respectively | [49] |

| Methylprednisolone | 0.5 mg/kg | Hospitalized COVID-19 patients ages> =18 | Randomized controlled phase IIb clinical trial (Metcovid study) | 28-day mortality | No substantial difference in primary outcome between two groups, lower mortality rate at day 28 in > =60 years old patients in treatment group | [50] |

| Dexamethasone | Group 1: 6 mg/24 h for 10 days (+routine ICU support) Group 2: 16 mg/24 h for 5 days+ 8 mg/24 h for 5 days (+routine ICU support) |

Patients with ARDS secondary to COVID-19 infection | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Ventilator-free days at day 28 | Trial terminated due to low rate of recruitment | [51] |

| Hydrocortisone | 200 mg/d for 7 days+ 100 mg/d for 4 days+ 50 mg/d for 3 days | Patients admitted to ICU for acute respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 | Multi-center randomized double blind sequential trial | Treatment failure (death, persistent dependence on ventilators or high-flow oxygen therapy) on day 21 | Primary outcome occurred in 42.1% in treatment group in comparison with 50.7% in controls | [52] |

| Hydrocortisone | Fixed 7-day course 100 mg or 50 mg every 6 h, shock dependent course 50 mg every 6 h in case of evident shock | Severe COVID-19 | Randomized, controlled trial (REMAP-CAP study) | Organ support-free days in 21 days | Primary outcome median 0 days in all three groups, 30% (fixed-dose), 26% (shock dependent), and 33% (controls) mortality rate, median organ support-free days among survivors 11.5, 9.5, and 6 days, respectively | [53] |

| Methylprednisolone | 250 mg/day, 3 days | Early pulmonary phase COVID-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Time of clinical improvement/death (whichever sooner) | Patients improvement 94.1% (treatment) and 57.1% (control), mortality rate 5.9% (treatment) and 42.9% (controls) | [54] |

| Dexamethasone | 20 mg daily for 5 days, 10 mg daily for 5 days (or until ICU discharge) | COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe ARDS | Randomized controlled clinical trial (CoDEX trial) | Ventilator-free days at day 28 | 6.6 ventilator-free days in dexamethasone group versus 4 ventilator-free days in control group | [55] |

| Corticosteroids | Corticosteroids regardless of type, dose, and treatment duration | Severe ARDS secondary to COVID-19 | Retrospective observational study | 28-day all-cause mortality | primary outcome 44.3% (corticosteroids) versus 31% (controls) | [56] |

| Corticosteroids | Systemic prednisone starting with 1 mg/kg/day and tapering the dose for 15 days + nasal irrigation with betamethasone, ambroxol, and rinazine | > 30 days anosmia or severe hyposmia secondary to COVID-19 infection | Randomized case-control study | – | Higher improvement from baseline in median olfactory score in treatment groups at both 20-day and 40-day checkpoints | [57] |

| Methylprednisolone | 1 mg/kg/day | COVID-19 pneumonia | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Presence of clinical deterioration after 14 days | No substantial difference in primary outcome between two groups, prolonged viral shedding in treatment group | [58] |

| Methylprednisolone | 40 mg bid, 3 days + 20 mg bid, 3 days | COVID-19 pneumonia | Randomized controlled clinical trial (GLUCOCOVID trial) | Death, admission to ICU, requirement for non-invasive ventilation | 40% (treatment) versus 48% (control) reached endpoint in intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis | [59] |

| Dexamethasone | 20 mg/day; day 1–5, 10 mg/day; day 6–10 | Mild to moderate ARDS secondary to COVID-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Need for invasive mechanical ventilation and heath rate | Treatment group: non-invasive ventilation 92%, invasive ventilation 52%, death 64% control group: non-invasive ventilation 96%, invasive ventilation 44%, death 60% |

[60] |

| Methylprednisolone, dexamethasone | MP= 2 mg/day, DX= 6 mg/day | Hospitalized COVID-19 patients | Randomized controlled clinical trial | All-cause mortality in 28 days, clinical status after 5 days and 10 days with 9-point WHO ordinal scale | MP group: clinical status day 5 = 4.02, at day 10 = 2.90, overall mean score= 3.909, mean length of hospital stay 7.43 ± 3.64 days, need for a ventilator= 18.2% DX group: clinical status day 5 = 5.21, at day 10 = 4.71, overall mean score= 4.873, mean length of hospital stay 10.52 ± 5.47 days, need for a ventilator= 38.1% | [61] |

| Corticosteroids | – | Mild to critically-ill COVID-19 patients | Retrospective study | Odds ratio for improvement on a 7-point ordinal score on day 15 | Primary outcome significantly lower in treatment group (OR, 0.611;95% CI), shorter time to improvement in radiological findings (HR,1.758;95% CI), shorter duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (HR,1.466;95% CI) in treatment group | [62] |

| Methylprednisolone, dexamethasone | DX 6 mg QD 7–10 days MP 250–500 mg/day, 3 days; then oral prednisone 50 mg for 14 days |

Severe COVID-19 pneumonia | Cohort study | Clinical outcome and laboratory differences between two groups (MP and DX) | Lower rate of severe ARDS (17.1% versus 26.1%), more reduction in levels of severity biomarkers such as CRP (2.85 versus 7.2) and D-dimer (691 versus 1083), lower rate of transferring to ICU (4.8% versus 14.4%) and death (9.5% versus 17.1%) in the group receiving MP in comparison with DX group | [63] |

| Momentsone furoate | 100 mcg bid | Non-hospitalized COVID-19 adult patients with severe microsmia or anosmia within 2 weeks | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Improvement of olfactory score | Higher improvement in severe chronic anosmia in comparison with olfactory training | [64] |

| Methylprednisolone/methylprednisolone + tocilizumab | MP 40 mg bid 7 days, toilizumabsingle dose 400 mg | Severe COVID-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | All-cause mortality in 45 days, rate of admission to ICU, length of ICU stay, days on ventilators, length of hospital stay | Rates of ICU admission and invasive mechanical ventilation lowest in MP only group, time on ventilator lowest in MP group, highest in controls, days in ICU in MP group lower than both controls and MP+tocilizumab, mortality 4.3% in MP group and 18.5% in control group | [65] |

Based on the WHO guidelines on the administration of corticosteroids, there are two recommendations. First recommendation states that systemic corticosteroids are favored in comparison to non-systemic corticosteroids, which is the choice in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients regardless of their hospitalization status [46]. Severe COVID-19 infection applies to patients with SpO2 < 94% on room air at sea level, respiratory rate of > 30 breaths per minute, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mm Hg, or pulmonary infiltrates > 50%. Critical COVID-19 infection applies to patients with conditions requiring life-sustaining procedures (mechanical ventilation, etc.) such as ARDS, multiple organ failure, cardiac failure, exaggerated inflammation, and septic shock [47].

The second recommendation states that it is better not to use corticosteroids in treatment of non-severe COVID-19 patients. Though, in cases of previously initiated treatment for other clinical conditions, corticosteroids should not be discontinued. Corticosteroid therapy, though beneficial in some cases, can cause susceptibility to complicated infections and should be taken into consideration while using this modality [46].

3.3. Challenges

Although the short-term use of corticosteroids has been helpful, high-dose corticosteroids can delay the viral clearance [40]. Based on the current guidelines, the administration of corticosteroids should be limited due to their wide range of side effects. Some of these include increase in mortality rates, diabetes, avascular necrosis, femoral head osteonecrosis, psychosis, and induction of lung injury and shock [66].

4. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

4.1. Mechanism of action

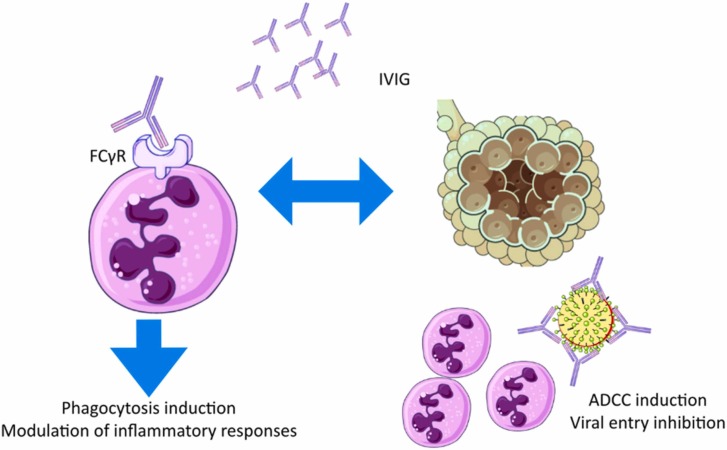

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a mixture of human immunoglobulins against microbial infections obtained from the recovered patients; it is administered as an immunomodulatory agent in autoimmune diseases and infections, and as replacement therapy in immunodeficiencies. In viral infections, administration of IVIG induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) through binding to viruses and inducing phagocytosis via binding to FCγR receptors; IVIG prevents the viral entry to the host cell via blocking viral surface proteins and modulates inflammatory reactions following the blockage of FCγR IIa and FCγR IIIb on leukocytes [67]. Fig. 4 summarizes these mechanisms.

Fig. 4.

IVIG mechanism of action in COVID-19.

4.2. Administration Indications and Clinical Findings

IVIG administration in SARS patients has improved patient’s survival, shortened the viremia period, and led to early discharge [68]. In addition, IVIG can reduce the mortality rate in patients affected with MERS-CoV [69].

Several studies have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of IVIG for COVID-19, which are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the results of studies on administration of IVIG in COVID-19 patients. (RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction).

| Intervention | Dosage | Population | Study design | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVIG | 4 vials daily for 3 days | Severe covid-19 with no response to initial treatments | Randomized placebo-controlled trial | In-hospital mortality rate lower in treatment group (20% versus 48.3%) | [71] |

| IVIG | 400 mg/kg daily, 3 days | Severe covid-19 | Randomized placebo-controlled trial | Length of hospital stay lower in control group (p = 0.003), though a positive correlation between the amount of time between admission to hospital and IVIG administration and length of hospital and ICU stay (p < 0.001 and p = 0.01 respectively), no significant difference between mortality rates (p = 0.8) and need for mechanical ventilation (p = 0.39) between two groups | [72] |

| IVIG | 0.4 g/kg daily, 5 days | Covid-19 patients with moderate pneumonia | Randomized placebo-controlled trial, phase II | Shorter hospital stay in treatment group (7.7 vs. 17.5 days), shorter median time to RT-PCR negative results in IVIG group (7 vs. 18 days), no significant differences in percentage of mechanical ventilation (24% vs. 38%) | [73] |

| IVIG | 2 g/kg | Severe covid-19 | Retrospective | Lower 28-day mortality (more prominently in patients with no other co-morbidities or treated in earlier stages) and lower time to inflammatory biomarker normalization in IVIG group, | [74] |

| IVIG | – | Covid-19 | Meta-analysis | Mortality significantly reduced in critical patients in comparison with controls (RR=0.57), no significant change in mortality of severe and non-severe cases | [75] |

| High dose polyclonal IVIG | – | Covid-19 | Systematic review | No significant reduction in risk of death (RR=0.5), significant reduction in length of hospitalization (only in studies on moderate covid-19) | [76] |

| IVIG + methylprednisolone | 0.5 g/kg/day IVIG, methylprednisolone 40 mg | Covid-19 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Lower need to mechanical ventilation (2/14 vs. 7/12), shorter median length of hospital stay (11 vs. 19 days), shorter length of ICU stay (2.5 vs. 12.5 days), greater improvement in PaO2/FiO2 in 7 days (+131 vs. +44.5) | [77] |

| IVIG | – | Non-severe covid-19 | Retrospective cohort study | Lower progression to severe disease (3.3% vs. 6.6%) and death (0 vs. 2.2%) in IVIG group in comparison with controls | [78] |

| IVIG | IVIG 5% 30 g/day, 5 days | Critically ill covid-19 | Retrospective cohort study | Higher survival rate (61% vs. 38%), longer median survival time (68 vs. 18 days) in IVIG group in comparison with controls | [79] |

| IVIG | 0.1–0.5 g/kg/day, 5–15 days | Critically ill covid-19 | Retrospective cohort study | Improvement in 28-day mortality and length of hospital stay in IVIG patients | [80] |

High dose IVIG is indicated in all acute severe COVID-19 patients (aimed to reduce post-infection cytokine storm and prevent thrombosis), all patients presented with or developed autoimmune disorders such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome, and patients with primary and secondary immunodeficiencies succumbing to acute COVID-19. Low dose IVIG is indicated in unvaccinated patients with autoimmune disorders or primary and secondary immunodeficiencies for protection against exposure to the virus. IVIG is also helpful in neurological disorders as a result of COVID-19’s inflammatory sequelae, including cognitive dysfunction, neuralgia, insomnia, and autonomic nervous system involvement [70].

4.3. Challenges

Some serious adverse effects such as hemolytic anemia, acute lung injury, thrombosis, cardiac arrhythmia, meningitis, and renal impairment and lack of sufficient data concerning this therapeutic method have restricted its use in COVID-19 patients; therefore, more studies are necessary in this regard [67].

5. Interferons

5.1. Mechanism of action

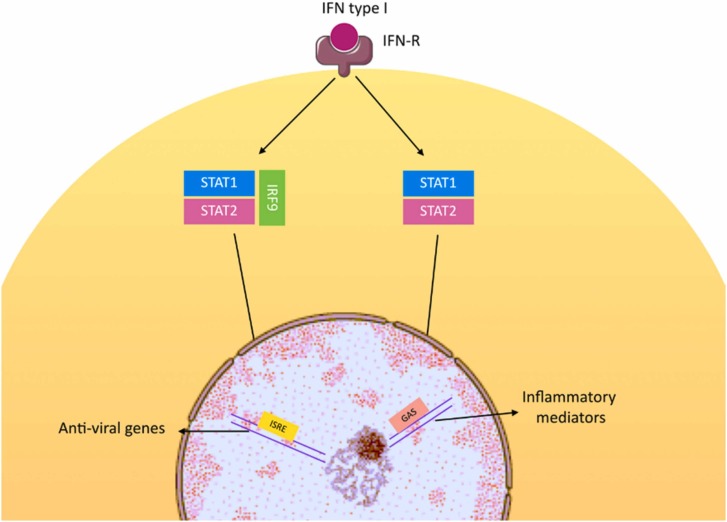

Expression of interferon-I (IFN-I) family, including IFN-α and IFN-β, is upregulated following the viral attachment to cell surface receptors and induction of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Higher levels of IFN-α and IFN-β, subsequently induce Janus kinase (JAK) signaling pathway and interferon-stimulated genes, providing the first line of antiviral defense [81]. In comparison to other coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2 shows higher efficacy in proliferation and infection with shorter duration to peak levels and higher number of viral particles at the time of peak, which can be a result of insufficient IFN-I response [82], [83], [84]. In addition, disease severity can be associated with insufficient innate IFN-I levels, which results in reduction in IFN-stimulated genes expression. Therefore, patients with low IFN-I signaling levels have a poor prognosis [85]. A study by Hadjadj et al. demonstrated that expression of IFN-stimulated genes is upregulated when patients are subjected to IFN-α stimulation, stating that the downstream components of the signaling pathway are not impaired [86]. Fig. 5 illustrates these mechanisms.

Fig. 5.

Interferons in COVID-19.

5.2. Administration indications and clinical findings

Administration of IFN-I in earlier stages of the disease can reduce the later-coming immunopathologies. Although administration of IFN-I can improve disease outcomes, it can over-activate inflammatory responses, exacerbating the condition. Therefore, IFN-III can be a substitute for IFN-I with similar antiviral characteristics and less toxicity [87]. A study by Jagannathan et al. on administration of pegylated (PEG) IFN-λ1a in mild to moderate COVID-19 patients showed that it can shorten viral shedding and duration of the symptomatic phase, if administered in a period of 72 h after diagnosis [88]. IFN-λ can inhibit the tissue repair as well as the damaging effects of neutrophils on lungs; of note, outcomes of using IFN-λ depend on location, timing, and duration of administration [89].

There is evidence on early administration of interferon in patients receiving glucocorticoids that shorten the duration of hospital stay and symptomatic stage, suggesting a therapeutic synergy [90].

Several studies have been conducted on administration of interferons in COVID-19 patients, some of the most recent of which are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of the results of studies on administration of interferons in COVID-19 patients.

| Intervention | Dosage | Population | Study design | Primary outcome | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-β1b, lopinavir, ritonavir, Ribavirin | IFN-β1b 3 doses 8 million IU, lopinavir 400 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, Ribavirin 400 mg bid, 14 days | COVID-19 patients | Phase II clinical trial | Time to negative nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test | Shorter time from start of study to a negative RT-PCR test in treatment group in comparison with controls (receiving Lopinavir+ritonavir (7 vs. 12 days) | [91] |

| IFN-β1a | 44 µg SC, every other day, up to 10 days | COVID-19 patients | Prospective non-controlled trial | – | Fiver resolved in 7 days, extension virological clearance in 10 days, recovery in imaging findings in 14-days in all patients | [92] |

| IFN-α2b, arbidol, IFN-α2b+arbidol | IFN-α2b 5 million IU bid, arbidol 200 mg did | COVID-19 patients | Uncontrolled clinical trial | – | Reduction of the duration of virus detection in upper respiratory tract and elevated blood inflammatory markers in treatment with IFN-α2b with or without arbidol | [93] |

| IFN-β1a | 12 million IU/ml, 3 times a week | Severe covid-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Time to reach clinical response | Primary outcome no significantly different, hospital discharge on day 14, 66.7% in treatment group vs. 43.6% in controls, lower 28-day mortality in treatment group (19% vs. 43.6%) | [94] |

| IFN-β1b | 250 µg/day SC, 2 weeks | Severe covid-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Time to clinical improvement | Shorter time to clinical improvement (9 vs. 11 days), higher percentage of hospital discharge at day 14 (78.79% vs. 54.55%), lower 28-day mortality (6.06% vs. 18.18) | [95] |

| IFN-β1b + favipiravir | IFN-β1b 8 million IU bid 5 days favipiravir 1600 mg day 1 + 600 mg bid maximum of 10 days | Moderate to severe covid-19 pneumonia | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Time to clinical recovery, normalization of inflammatory biomarkers, improvement of oxygen saturation, maintained for at least 72 h | No significant difference between length of hospital stay, levels of inflammatory biomarkers, transfer to ICU, discharges, and mortality between two groups | [96] |

| IFN-β1a | 12 million IU | Mild to moderate pneumonia in COVID-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial (INTERCOP) | Time to negative conversion of nasopharyngeal swabs | – | [97] |

| IFN-α, recombinant super compound IFN-α (rSIFN-co) | IFN-α (2a or 2b) 5 million IU bid, rSIFN-co 12 million IU bid until discharge from hospital | Moderate to severe covid-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Time to clinical improvement | Shorter time to clinical improvement (11.5 vs. 14), time to radiological improvement (8 vs. 10 days), and time to virus RNA negative conversion (7 vs. 10 days), higher rate of clinical improvement on day 28 (93.5% vs. 77.1%) in rSFN-co group | [98] |

| PEG IFN-α2b | 1 μg/kg SC single dose | Moderate covid-19 | Phase II clinical trial | Clinical status improvement on day 15 (WHO 7-point ordinal scale) | Higher percentage of negative RT-PCR on day 7 (80% vs. 63%) and 14 (95% vs. 68%) and higher percentage of clinical improvement on day 15 (95% vs. 68.42%) in treatment group in comparison with controls | [99] |

| IFN-β1a, IFN-β1b | IFN-β1a 12,000 IU, IFN-β1b 8 million IU | Severe covid-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial (COVIFERON) | Time to clinical improvement | Significant difference in primary outcome between IFN-β1a group and controls (HR 2.36), no Significant difference in primary outcome between IFN-β1b group and controls (HR 1.42), lower mortality in treatment groups vs. controls (20% IFN-β1a, 30% IFN-β1b, 45% controls) | [100] |

| Recombinant human IFN-α nasal drop (rhIFN-α) | Nasal drops in low risk group, nasal drops + thymosinα1 in high risk group for 1 month | Medical staff | Prospective clinical trial | New outset of COVID-19 diagnosed by chest CT in 30 days | Negative CT scan in both groups after 1 month | [101] |

| IFN-based therapy (IFN-β1b+ritonavir/lopinavir+ribavirin) vs. favipiravir | IFN-β1b 8 million IU, lopinavir 400 mg, ritonavir 100 mg, Ribavirin 400 mg bid, favipiravir 1800 mg/dose bid day 1 + 800 mg/dose bid 7–10 days | Non-critical covid-19 | Cohort study | All-cause mortality in 28 days | Lower 28-day mortality (9% vs. 12%), less use of systemic corticosteroids (57% vs. 77%) in IFN-based therapy group in comparison with favipiravir group, no significant different in hospitalization duration between two groups | [102] |

| IFN-β1a low dose vs. high dose | Low dose 24 million IU, high dose 12 million IU | Severe covid-19 | Randomized controlled clinical trial (COVIFERON II) | Time to clinical improvement | Shorter time to clinical improvement in low dose group in comparison with high dose group (6 vs. 10 days), insignificantly higher mortality rate in low dose group (41% vs. 36.5%) | [103] |

| PEG IFN-α2b | 1 μg/kg SC single dose | Moderate covid-19 | Phase III clinical trial | Two-point improvement in clinical status on day 11 (WHO 7-point ordinal scale) | Early viral clearance, improved clinical status and reduction of duration of oxygen supplementation in PEG IFN-α2b group | [104] |

| IFN-β1a + remdesivir vs. remdesivir | IFN-β1a 44 μg, remdesivir 200 mg loading dose day 1, 100 mg/day maintenance dose up to 9 days | Hospitalized covid-19 patients | Phase III clinical trial | recovery (the first day that a patient had a category 1, 2, or 3 score on the eight-category ordinal scale within 28 days) | Time of recovery of 5 days in both groups, no significant difference in 28-day mortality | [105] |

| IFN-β1a vs. IFN-β1b | IFN-β1a 12 million IU, IFN-β1b 8 million IU | Hospitalized covid-19 patients | Clinical trial | Clinical improvement (rate of hospital discharge) | No significant difference in discharge time, mortality, ICU length of stay, and frequency of mechanical ventilation between the two groups | [106] |

According to the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, based on the results from clinical trials, and with respect to the lack of thorough evidence on the occurrence of adverse effects in some patient groups, the Panel recommend against the administration of interferons (α, β, and λ) in hospitalized patients unless in the setting of a clinical trial [33].

5.3. Challenges

The immune system imbalance and the resulting immunopathology has restricted the administration of interferons in COVID-19 patients; in patients receiving interferons, careful patient monitoring during the treatment is crucial [87].

6. Monoclonal antibodies

6.1. Mechanism of action

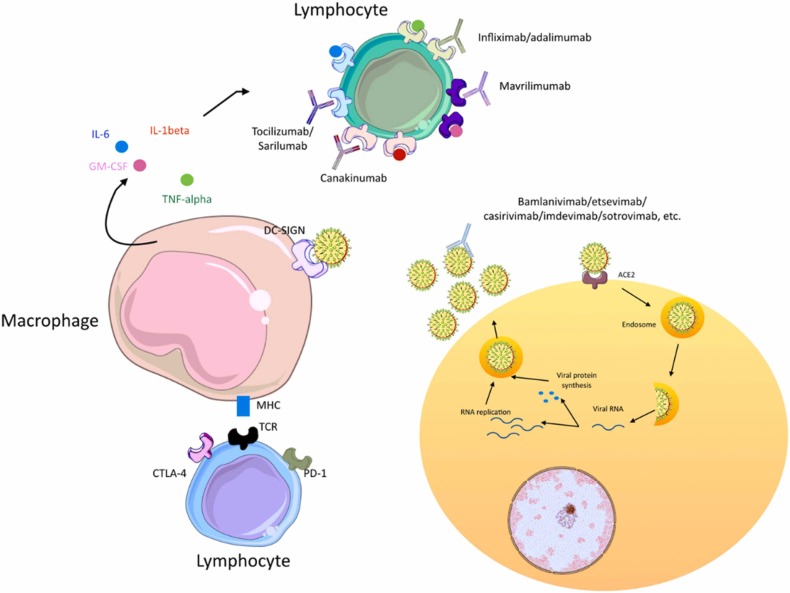

Monoclonal antibodies target different molecules that are involved in COVID-19 pathogenesis; amongst which there are some of the viral surface proteins such as spike (S) protein and contributors to the cytokine storm syndrome (CSS) such as IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β [107]. The S protein has two subunits; S1 is involved in attachment to ACE2 by means of a receptor binding domain (RBD) and help of the N-terminal domain (NTD) through recognition of sugar moieties, and S2 is involved in fusion of the viral particle. Neutralizing any of these targets can be helpful for the prevention of viral infection [107], [108], [109]. CSS is an uncontrolled inflammation especially in critical COVID-19 patients, leading to fever, ARDS, multiple organ failure, and death. Targeting the inflammatory factors involved in CSS can reduce the COVID − 19 mortality rate [110], [111], [112], [113].

Fig. 6 illustrates these mechanisms.

Fig. 6.

Monoclonal antibodies in COVID-19.

6.2. Administration indications and clinical findings

Monoclonal antibodies can be beneficial in the treatment as well as pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis [33]. Administration of monoclonal antibodies cause a better overall survival in hospitalized patients [114]. A variety of clinical and preclinical studies have been carried out to evaluate the effect of administration of monoclonal antibodies in different stages of COVID-19 infection. Table 6 summarizes results of recently conducted clinical trial in this regard.

Table 6.

Recent clinical trials on use of monoclonal antibodies in COVID-19.

| Monoclonal antibody | Target molecule | Disease stage | Clinical trial number | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tocilizumab | IL-6R | Moderate to severe | NCT04331808, NCT04356937 NCT04317092 (TOCIVID-19) NCT04331795 (COVIDOSE) NCT04372186 CTRI/2020/05/025369 (COVINTOC) ChiCTR2000029765 NCT04381936 (RECOVERY) NCT04346355 | Reduction in risk of death, mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, improvement in clinical and laboratory markers of hyper inflammation, reduction in time to negative virus load, though not beneficial in some studies | [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123] |

| Severe / critical | IRCT20150303021315N17 NCT04403685 NCT04320615 NCT04409262 (REMDACTA) NCT04779047 | Improvement in risk of death, O2 saturation, required level of oxygenation, respiratory rate, though not beneficial in some studies, | [124], [125], [126], [127], [128] | ||

| Itolizumab | CD6 | Moderate | RPCEC00000311 (VICTORIA) | Improvement in clinical (lower ICU admission), laboratory (reduction in IL-6 levels), and mortality | [129] |

| Sarilumab | IL-6R | Severe / critical | NCT04327388 | Not significantly beneficial | [130] |

| Bamlanivimab | S protein | Prophylaxis in medical staff | NCT04497987 | Reduction in incidence of COVID-19 infection | [131] |

| Mild to moderate | NCT04427501 (BLAZE-1) | Not significantly beneficial, slight reduction in neutralizing activity of day 29 serum | [132], [133] | ||

| Hospitalized (no organ failure) | NCT04501978 | Not significantly beneficial | [134] | ||

| Etesevimab | S protein | Healthy adults | NCT04441918 | Well-tolerated | [135] |

| Bamlanivimab+Etesevimab | S protein | Mild to moderate | NCT04427501 (BLAZE-1) NCT04634409 (BLAZE-4) | Reduction in viral load, hospitalization, death, | [132], [133], [136], [137] |

| REGEN-CoV (casirivimab+imdevimab) | S protein (RBD) | Outpatients | NCT04425629 | Reduction in viral load | [138], [139], [140] |

| Hospitalized | NCT04426695 | Ongoing trial | |||

| MW33 | S protein (RBD) | Healthy adults | NCT04533048 | Well-tolerated | [141] |

| Mild to moderate | NCT04627584 | Ongoing trial | |||

| SCTA01 | S protein | Healthy adults | NCT04483375 | Well-tolerated | [142] |

| Regdanvimab (CT-P59) | S protein | Healthy adults | NCT04525079 | Well-tolerated | [143] |

| Mild infection | NCT04593641 | More reduction in viral load, shorter duration to recovery | |||

| Sotrovimab | S protein | Mild to moderate | NCT04545060 (COMET-ICE) | Reduction in risk of disease progression | [144] |

Among these antibodies, some have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab and casirivimab plus imdevimab combination therapies are two of the approved treatment regimens. Though, administration of these products has been paused in the US due to lower susceptibility of the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. Sotrovimab is also authorized for administration in both SARS-CoV-1 and different variants of SARS-CoV-2. Combination therapy using tixagevimab plus cilgavimab has also been approved and is used in different variants of COVID-19, including the Omicron variant. This combination can also be used as a pre-exposure prophylaxis and has received an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the FDA in this matter.

The COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines panel recommends administration of single dose sotrovimab 500 mg IV in non-hospitalized mild to moderate infection as soon as possible. Administration of bamlanivimab plus etesevimab and casirivimab plus imdevimab combination therapy is not recommended in omicron variant outbreaks. The panel also recommends against the use of monoclonal antibodies in cases of hospitalized severe infection, and also in immunocompromised patients (due to risk of resistance) [33].

6.3. Challenges

The rapid emergence of various SARS-CoV-2 new variants calls for the need to developing antibodies against the new epitopes and developing tools for timely prediction of the emergence of new variants [107].

7. Cell-based therapy: mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

7.1. Mechanism of action

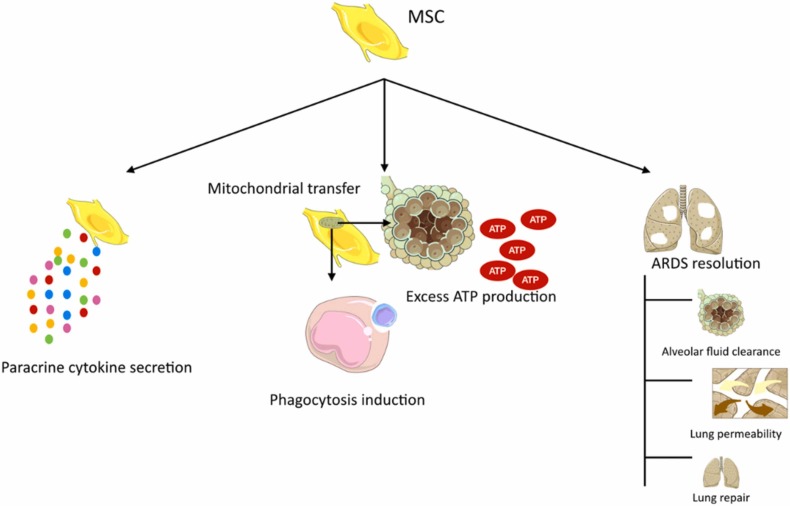

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are plastic-adherent stem cells with an in vitro differential potential and an ability to express a variety of markers such as CD105, CD90, and CD73, and lack of CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD34, CD45, CD79α, and HLA-DR [145]. MSCs could be an appropriate treatment candidate due to the easy isolation from the donor tissue, as well as lack of expression of HLA markers, rapid proliferation, proper homing capacity of the target site, and persistence in the target lung tissue [146].

The mechanisms involving these cells include immunomodulation and paracrine secretion of cytokines such as, IL-37, keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), lipoxin A4, and angiopoietin-1. In addition, they can induce ATP production in alveoli and enhance phagocytosis by means of mitochondrial transfer. In ARDS cases, it can improve the condition by inducing lung permeability, fluid clearance in alveoli, and lung repair in both epithelial and endothelial tissues [146]. Fig. 7 illustrates these mechanisms.

Fig. 7.

MSCs mechanism of action.

7.2. Administration indications and clinical findings

Since MSCs express low levels of ACE2 and transmembrane protease serine type 2 (TMPRSS2), they are resistant to SASRS-CoV-2 infection regardless of their source [147]. This therapeutic approach has been well tolerated in COVID-19 patients according to the results of the clinical trials. Table 7 summarizes the results of recent studies in this field.

Table 7.

Safety and efficacy data regarding administration of MSCs in COVID-19 patients.

| Source of MSCs | Population | Study design | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umbilical cord | Hospitalized COVID-19 patients | Phase 1 clinical trial | Safe and well tolerated | [148] |

| Wharton Jelly | Moderate and critical COVID-19 patients | Prospective double-controlled trial | Significant levels of pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and growth factors and significant reduction in ferritin, fibrinogen, and CRP levels in MSC receiving group, | [149] |

| Umbilical cord | Severe/critical COVID-19 patients | Uncontrolled clinical trial | Discharge from ICU 52.5%, mortality 47.5% among critically severe intubated patients, Discharge from ICU 77.5%, mortality 22.5% among critically severe non-intubated patients, higher survival in cases of pre-intubation MSC administration (OR=1.475) | [150] |

| Umbilical cord | ARDS secondary to COVID-19 | Pilot study | Constant rise of PaO2/FiO2 in first 7 days, 3 of the 5 patients survived and were extubated on day 9, the method was relatively well-tolerated | [151] |

| Perinatal tissue | ARDS secondary to COVID-19 | Case series | 7 patients showed clinical improvement, 6 of the 7 patients enrolled survived, reduction in levels of TNF-α, IL-8, CRP, IFN-γ, and IL-6, and remarkable signs of radiologic recovery was observed | [152] |

| Umbilical cord | Severe COVID-19 | Randomized controlled trial | Lower incidence of progression, mortality, shorter time to clinical improvement in treatment group, reduction in levels of IL-6 and CRP | [153] |

| Menstrual blood | Severe/critical COVID-19 patients | Exploratory clinical trial | Lower mortality (7.69% vs. 33.33%) in treatment group in comparison with controls, improvement in SpO2, dyspnea and radiological findings | [154] |

| Umbilical cord | Severe/critical COVID-19 patients | Pilot study | Improvement in oxygenation index, radiological findings, and lymphocyte count, lower mortality in comparison with historical rate (6.25% vs. 45.4%) | [155] |

| N/A (ACE2- MSCs) | Severe COVID-19 pneumonia | Pilot study | Clinical improvement, reduction in levels of CRP, over-activated cytokine secreting cells, TNF-α, and increase in levels of peripheral lymphocyte, regulatory DC, IL-10 | [156] |

| Umbilical cord | Critical COVID-19 | Randomized controlled trial | 2.5 times higher survival rate in treatment group in comparison with controls, no significant difference in length of stay in ICU and ventilator usage, reduction in IL-6 levels | [157] |

| Umbilical cord | Severe COVID-19 | Randomized controlled phase 2 trial | Improvement in radiological findings | [158] |

| Umbilical cord | ARDS secondary to COVID-19 | Randomized controlled phase 1/2a trial | Significant reduction I. Inflammatory cytokines, improvement in patient survival (91% vs. 42%) and time to recovery (P = 0.03) | [159] |

Though promising results have been observed regarding this treatment modality, the COVID-19 Treatment Guideline Panel recommends against the administration of MSCs, unless it is in a clinical trial setting, due to limitation of data [33].

7.3. Challenges

Although recent studies have shown promising results for using MSCs, we still face some problems. Some of such barriers include variability of MSC sources and the need to identify the most suitable source and standardization of the methods of handling MSCs, both in preparation and administration [146].

8. Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic has caused considerable morbidities and mortalities over the past couple of years. Involvement of the immune system as a double-edged sword, both in constraining the disease and in causing complications such as CSS, has made immune-based approaches a great candidate in combating the disease, amongst which corticosteroids, IVIG, interferon therapy, and monoclonal antibodies are reviewed in this article. Each of these therapeutic approaches are beneficial in specific clinical settings and disease stages to gain the most improvement in clinical conditions with the least adverse effects (susceptibility to infections, etc.). Corticosteroids are advised to be considered in severe or critically ill patients due to their variety of potential side effects. IVIG has shown promising results in trials, though its use is limited and more studies need to be conducted due to the risk of multisystem adverse events. Interferon therapy though considered beneficial in a variety of infectious diseases, including COVID-19, it can cause a range of immune system imbalances; therefore, its usage is currently limited. Monoclonal antibodies are a targeted therapeutic modality and have shown promising results in patients in a variety of disease stages. Nevertheless, due to the rapid emergence of new variants they might lose their efficacy in different outbreaks based on the prevalent variants, hence, it is important to develop antibodies against new epitopes. Overall, in each clinicobiological phase in COVID-19 pathogenesis, some therapeutic agents are indicated. In the asymptomatic phase, monoclonal antibodies can be used; for instance, as mentioned before, bamlanivimab has been used in medical staff as a prophylaxis agent (Table 6). In the propagating phase, different agents can be suitable depending on disease severity. Patients with mild disease, respond to monoclonal antibodies such as bamlanivimab, the combination of bamlanivimab plus etesevimab, MW33, regdanvimab, and sotrovimab (Table 6). In moderately ill patients, monoclonal antibodies (e.g, tocilizumab, itolizumab, bamlanivimab, the combination of bamlanivimab plus etesevimab, MW33, and sotrovimab [Table 6]), interferon therapy (Table 5), and based on results of some trials (Table 4), IVIG can be beneficial. In severely ill patients and patients in complicating phase of the disease, corticosteroids, IVIG, interferons, and monoclonal antibodies can be beneficial. For the administration of monoclonal antibodies, the virus strain is an important factor and it should be taken into consideration in deciding the drug of choice. Although a wide range of pre-clinical and clinical studies have been conducted regarding immune-based approaches, more studies are needed in order to improve both efficacy and safety of these modalities and the choice of drugs vary based on a wide range of factors including disease stage and availability of agents of choice.

Funding

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aysan Moeinafshar: Conceptualization, Roles/Writing − original draft, Writing − review & editing. Niloufar Yazdanpanah: Conceptualization, Roles/Writing − original draft, Writing − review & editing. Nima Rezaei: Conceptualization, Writing − review & editing, Supervision. All the authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Authors Contribution

AM conceptualized the title and prepared the first draft. NY conceptualized the title, edited and revised the manuscript and finalized the draft. NR conceptualized the title, critically revised the manuscript, finalized the draft, and supervised the project. All the authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Kumar M., Al Khodor S. Pathophysiology and treatment strategies for COVID-19. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02520-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollard C.A., Morran M.P., Nestor-Kalinoski A.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol. Genom. 2020;52(11):549–557. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00089.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 22 March 2022. (Edition 84). Available from: 〈https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---22-march-2022〉.

- 4.Wiersinga W.J., Rhodes A., Cheng A.C., Peacock S.J., Prescott H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324(8):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha P., Calfee C.S. Immunotherapy in COVID-19: why, who, and when? Lancet Respir. Med [Internet] 2021;9(6):549–551. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park S.E. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome -coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; Coronavirus Disease-19) Clin. Exp. Pedia. 2020;63(4):119–124. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilip Pandkar P., Sachdeva V. Pathophysiology of COVID-19 and Host centric approaches of Ayurveda. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Q., Xu W., Wang P.-F., Ji H.-Y., Zhang X.-L., Wang K., et al. Facing coronavirus disease 2019: What do we know so far? (Review) Exp. Ther. Med. 2021;21(6):658. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.10090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turk C., Turk S., Malkan U.Y., Haznedaroglu I.C. Three critical clinicobiological phases of the human SARS-associated coronavirus infections. Eur. Rev. Med Pharm. Sci. 2020;24(16):8606–8620. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202008_22660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sims A.C., Baric R.S., Yount B., Burkett S.E., Collins P.L., Pickles R.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of human ciliated airway epithelia: role of ciliated cells in viral spread in the conducting airways of the lungs. J. Virol. 2005;79(24):15511–15524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15511-15524.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Intern Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata-Yoshikawa N., Okamura T., Shimizu Y., Hasegawa H., Takeda M., Nagata N. TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 2019;93(6) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01815-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong C.K., Lam C.W.K., Wu A.K.L., Ip W.K., Lee N.L.S., Chan I.H.S., et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004;136(1):95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y., Shen C., Li J., Yuan J., Wei J., Huang F., et al. Plasma IP-10 and MCP-3 levels are highly associated with disease severity and predict the progression of COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146(1):119–127.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian Z., Travanty E.A., Oko L., Edeen K., Berglund A., Wang J., et al. Innate immune response of human alveolar type II cells infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;48(6):742–748. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0339OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (Lond., Engl. ) 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian S., Xiong Y., Liu H., Niu L., Guo J., Liao M., et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod. Pathol. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2020;33(6):1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tse G.M.-K., To K.-F., Chan P.K.-S., Lo A.W.I., Ng K.-C., Wu A., et al. Pulmonary pathological features in coronavirus associated severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) J. Clin. Pathol. 2004;57(3):260–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L., Wang Y., Ye D., Liu Q. Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence. Int J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55(6) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;Vol. 8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian S., Hu W., Niu L., Liu H., Xu H., Xiao S.-Y. Pulmonary Pathology of Early-Phase 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia in Two Patients With Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. Publ. Int Assoc. Study Lung Cancer. 2020;15(5):700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larici A.R., Cicchetti G., Marano R., Bonomo L., Storto M.L. COVID-19 pneumonia: current evidence of chest imaging features, evolution and prognosis. Chin. J. Acad. Radio. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42058-021-00068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salehi S., Abedi A., Balakrishnan S., Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review of Imaging Findings in 919 Patients. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):87–93. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao C., Liu X., Zhang H., Li Y., Liu J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) CT Findings: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Radio. 2020;17(6):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams H.J.A., Kwee T.C., Yakar D., Hope M.D., Kwee R.M., Chest C.T. Imaging Signature of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection: In Pursuit of the Scientific Evidence. Chest. 2020;158(5):1885–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spagnolo P., Balestro E., Aliberti S., Cocconcelli E., Biondini D., Della Casa G., et al. Pulmonary fibrosis secondary to COVID-19: a call to arms? Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(8):750–752. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet (Lond., Engl. ) 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P., et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect. Dis. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y., Li T., Han M., Li X., Wu D., Xu Y., et al. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J. Med Virol. 2020;92(7):791–796. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eur. Surveill. Bull. Eur. sur Les. Mal. Transm. = Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binnicker M.J. Emergence of a Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Importance of Diagnostic Testing: Why Partnership between Clinical Laboratories, Public Health Agencies, and Industry Is Essential to Control the Outbreak. Clin. Chem. 2020;66(5):664–666. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines [Internet]. National Institutes of Health. [cited 2022 Mar 17]. Available from: 〈https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/〉.

- 34.Guo Y.-R., Cao Q.-D., Hong Z.-S., Tan Y.-Y., Chen S.-D., Jin H.-J., et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil. Med Res. 2020;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahase E. China coronavirus: what do we know so far? BMJ. 2020;368:m308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitjà O., Clotet B. Use of antiviral drugs to reduce COVID-19 transmission. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;Vol. 8:e639–e640. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo H., Tang Q.-L., Shang Y.-X., Liang S.-B., Yang M., Robinson N., et al. Can Chinese Medicine Be Used for Prevention of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A Review of Historical Classics, Research Evidence and Current Prevention Programs. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020;26(4):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11655-020-3192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Touret F., de Lamballerie X. Of chloroquine and COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020;177 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khamitov R.A., Loginova S.I., Shchukina V.N., Borisevich S.V., Maksimov V.A., Shuster A.M. [Antiviral activity of arbidol and its derivatives against the pathogen of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the cell cultures] Vopr. Virus. 2008;53(4):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arabi Y.M., Mandourah Y., Al-Hameed F., Sindi A.A., Almekhlafi G.A., Hussein M.A., et al. Corticosteroid Therapy for Critically Ill Patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197(6):757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nussey SS, Whitehead SA. Endocrinology: an integrated approach. 2001; [PubMed]

- 42.Ericson-Neilsen W., Kaye A.D. Steroids: pharmacology, complications, and practice delivery issues. Ochsner J. 2014;14(2):203–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen M.W., Meyhoff T.S., Helleberg M., Kjaer M.-B.N., Granholm A., Hjortsø C.J.S., et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone in patients with COVID-19 and severe hypoxia (COVID STEROID) trial-Protocol and statistical analysis plan. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020;64(9):1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/aas.13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. Vol. 3. 2006. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. (PLoS Med). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu W.C., Hui D.S.C., Chan-Yeung M. Antiviral agents and corticosteroids in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Thorax. 2004;Vol. 59:643–645. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.017665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agarwal A., Rochwerg B., Siemieniuk R.A.C., Agoritsas T., Lamontagne F., Askie L., et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ [Internet] 2020;370:m3379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379. 〈http://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3379.abstract〉 (Available from) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Institute of Health. Therapeutic management of hospitalized adults with COVID-19. 2021;(Accessed 13 July 2021). Available from: 〈https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/hospitalized-adults--therapeutic-management/〉.

- 48.Ramiro S., Mostard R.L.M., Magro-Checa C., van Dongen C.M.P., Dormans T., Buijs J., et al. Historically controlled comparison of glucocorticoids with or without tocilizumab versus supportive care only in patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome: results of the CHIC study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020;79(9):1143–1151. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munch M.W., Meyhoff T.S., Helleberg M., Kjaer M.-B.N., Granholm A., Hjortsø C.J.S., et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone in patients with COVID-19 and severe hypoxia: The COVID STEROID randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2021;65(10):1421–1430. doi: 10.1111/aas.13941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeronimo C.M.P., Farias M.E.L., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C., et al. Methylprednisolone as Adjunctive Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19; Metcovid): A Randomized, Double-blind, Phase IIb, Placebo-controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021;72(9):e373–e381. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maskin L.P., Olarte G.L., Palizas F.J., Velo A.E., Lurbet M.F., Bonelli I., et al. High dose dexamethasone treatment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome secondary to COVID-19: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;Vol. 21:743. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dequin P.-F., Heming N., Meziani F., Plantefève G., Voiriot G., Badié J., et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone on 21-Day Mortality or Respiratory Support Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1298–1306. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angus D.C., Derde L., Al-Beidh F., Annane D., Arabi Y., Beane A., et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone on Mortality and Organ Support in Patients With Severe COVID-19: The REMAP-CAP COVID-19 Corticosteroid Domain Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1317–1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edalatifard M., Akhtari M., Salehi M., Naderi Z., Jamshidi A., Mostafaei S., et al. Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse as a treatment for hospitalised severe COVID-19 patients: results from a randomised controlled clinical trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56(6) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02808-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomazini B.M., Maia I.S., Cavalcanti A.B., Berwanger O., Rosa R.G., Veiga V.C., et al. Effect of Dexamethasone on Days Alive and Ventilator-Free in Patients With Moderate or Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19: The CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J., Zhang S., Dong X., Li Z., Xu Q., Feng H., et al. Corticosteroid treatment in severe COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130(12):6417–6428. doi: 10.1172/JCI140617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaira L.A., Hopkins C., Petrocelli M., Lechien J.R., Cutrupi S., Salzano G., et al. Efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of long- lasting olfactory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Rhinology. 2021;59(1):21–25. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang X., Feng Y.-M., Ni J.-X., Zhang J.-Y., Liu L.-M., Hu K., et al. Early Use of Corticosteroid May Prolong SARS-CoV-2 Shedding in Non-Intensive Care Unit Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Multicenter, Single-Blind, Randomized Control Trial. Respiration. 2021;100(2):116–126. doi: 10.1159/000512063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corral-Gudino L., Bahamonde A., Arnaiz-Revillas F., Gómez-Barquero J., Abadía-Otero J., García-Ibarbia C., et al. Methylprednisolone in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: An open-label randomized trial (GLUCOCOVID) Wien. Klin. Woche. 2021;133(7–8):303–311. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jamaati H., Hashemian S.M., Farzanegan B., Malekmohammad M., Tabarsi P., Marjani M., et al. No clinical benefit of high dose corticosteroid administration in patients with COVID-19: A preliminary report of a randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Pharm. 2021;897 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ranjbar K., Moghadami M., Mirahmadizadeh A., Fallahi M.J., Khaloo V., Shahriarirad R., et al. Methylprednisolone or dexamethasone, which one is superior corticosteroid in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):337. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ikeda S., Misumi T., Izumi S., Sakamoto K., Nishimura N., Ro S., et al. Corticosteroids for hospitalized patients with mild to critically-ill COVID-19: a multicenter, retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):10727. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pinzón M.A., Ortiz S., Holguín H., Betancur J.F., Cardona Arango D., Laniado H., et al. Dexamethasone vs methylprednisolone high dose for Covid-19 pneumonia. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kasiri H., Rouhani N., Salehifar E., Ghazaeian M., Fallah S. Mometasone furoate nasal spray in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction: A randomized, double blind clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;98 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamed D.M., Belhoul K.M., Al Maazmi N.A., Ghayoor F., Moin M., Al Suwaidi M., et al. Intravenous methylprednisolone with or without tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring oxygen support: A prospective comparison. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(8):985–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel V.K., Shirbhate E., Patel P., Veerasamy R., Sharma P.C., Rajak H. Corticosteroids for treatment of COVID-19: effect, evidence, expectation and extent. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2021;10(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s43088-021-00165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moradimajd P., Samaee H., Sedigh-Maroufi S., Kourosh-Aami M., Mohsenzadagan M. Administration of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of COVID-19: A review of available evidence. J. Med Virol. 2021;93(5):2675–2682. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mo Y., Fisher D. A review of treatment modalities for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71(12):3340–3350. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mustafa S., Balkhy H., Gabere M.N. Current treatment options and the role of peptides as potential therapeutic components for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS): A review. J. Infect. Public Health. 2018;11(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Younger S. D. Preliminary Guidelines for the Use of IVIg during COVID-19. World J. Neurosci. [Internet] 2021;11:211–220. 〈https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=109645〉 (Available from) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gharebaghi N., Nejadrahim R., Mousavi S.J., Sadat-Ebrahimi S.-R., Hajizadeh R. The use of intravenous immunoglobulin gamma for the treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20(1):786. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05507-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tabarsi P., Barati S., Jamaati H., Haseli S., Marjani M., Moniri A., et al. Evaluating the effects of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIg) on the management of severe COVID-19 cases: A randomized controlled trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raman R.S., Bhagwan Barge V., Anil Kumar D., Dandu H., Rakesh Kartha R., Bafna V., et al. A Phase II Safety and Efficacy Study on Prognosis of Moderate Pneumonia in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients With Regular Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223(9):1538–1543. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cao W., Liu X., Hong K., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Lin L., et al. High-Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Multicenter Retrospective Study in China. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.627844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiang H.-R., Cheng X., Li Y., Luo W.-W., Zhang Q.-Z., Peng W.-X. Efficacy of IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) for corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Focosi D., Franchini M., Tuccori M., Cruciani M. Efficacy of High-Dose Polyclonal Intravenous Immunoglobulin in COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Vaccines. 2022;10(1) doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sakoulas G., Geriak M., Kullar R., Greenwood K.L., Habib M., Vyas A., et al. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) Significantly Reduces Respiratory Morbidity in COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Prospective Randomized Trial. medRxiv [Internet] 2020 〈http://medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/07/25/2020.07.20.20157891.abstract〉 (Available from) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang C., Fei L., Li W., Xu W., Xie X., Li Q., et al. Efficacy evaluation of intravenous immunoglobulin in non-severe patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study based on propensity score matching. Int J. Infect. Dis. IJID Publ. Int Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021;105:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Esen F., Özcan P.E., Orhun G., Polat Ö., Anaklı İ., Alay G., et al. Effects of adjunct treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins on the course of severe COVID-19: results from a retrospective cohort study. Curr. Med Res Opin. 2021;37(4):543–548. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1856058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shao Z., Feng Y., Zhong L., Xie Q., Lei M., Liu Z., et al. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in critical ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020;9(10) doi: 10.1002/cti2.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin F., Shen K. Type I interferon: From innate response to treatment for COVID-19. Pedia Invest. 2020;4(4):275–280. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chu H., Chan J.F.-W., Wang Y., Yuen T.T.-T., Chai Y., Hou Y., et al. Comparative Replication and Immune Activation Profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in Human Lungs: An Ex Vivo Study With Implications for the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2020;71(6):1400–1409. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.-C., Uhl S., Hoagland D., Møller R., et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181(5):1036–1045.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trouillet-Assant S., Viel S., Gaymard A., Pons S., Richard J.-C., Perret M., et al. Type I IFN immunoprofiling in COVID-19 patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;Vol. 146:206–208.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hadjadj J., Yatim N., Barnabei L., Corneau A., Boussier J., Smith N., et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369(6504):718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lyubavina N.A., Saltsev S.G., Menkov N.V., Tyurikova L.V., Plastinina S.S., Shonia M.L., et al. Immunological Approaches to the Treatment of New Coronavirus Infection (Review) Sovrem. tekhnologii V. meditsine. 2021;13(3):81–99. doi: 10.17691/stm2021.13.3.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jagannathan P., Andrews J.R., Bonilla H., Hedlin H., Jacobson K.B., Balasubramanian V., et al. Peginterferon Lambda-1a for treatment of outpatients with uncomplicated COVID-19: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1967. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Broggi A., Ghosh S., Sposito B., Spreafico R., Balzarini F., Lo Cascio A., et al. Type III interferons disrupt the lung epithelial barrier upon viral recognition. Science. 2020;369(6504):706–712. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lu Y., Liu F., Tong G., Qiu F., Song P., Wang X., et al. Clinical evidence of an interferon-glucocorticoid therapeutic synergy in COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. [Internet] 2021;6(1):107. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00496-5. 〈https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33658482〉 (Available from) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hung I.F.-N., Lung K.-C., Tso E.Y.-K., Liu R., Chung T.W.-H., Chu M.-Y., et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet (Lond., Engl. ) 2020;395(10238):1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dastan F., Nadji S.A., Saffaei A., Marjani M., Moniri A., Jamaati H., et al. Subcutaneous administration of interferon beta-1a for COVID-19: A non-controlled prospective trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;85 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou Q., Chen V., Shannon C.P., Wei X.-S., Xiang X., Wang X., et al. Interferon-α2b Treatment for COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1061. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davoudi-Monfared E., Rahmani H., Khalili H., Hajiabdolbaghi M., Salehi M., Abbasian L., et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Interferon β-1a in Treatment of Severe COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64(9) doi: 10.1128/AAC.01061-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rahmani H., Davoudi-Monfared E., Nourian A., Khalili H., Hajizadeh N., Jalalabadi N.Z., et al. Interferon β-1b in treatment of severe COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khamis F., Al Naabi H., Al Lawati A., Ambusaidi Z., Al Sharji M., Al, Barwani U., et al. Randomized controlled open label trial on the use of favipiravir combined with inhaled interferon beta-1b in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Int J. Infect. Dis. IJID Publ. Int Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021;102:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bosi E., Bosi C., Rovere Querini P., Mancini N., Calori G., Ruggeri A., et al. Interferon β-1a (IFNβ-1a) in COVID-19 patients (INTERCOP): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):939. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04864-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li C., Luo F., Liu C., Xiong N., Xu Z., Zhang W., et al. Effect of a genetically engineered interferon-alpha versus traditional interferon-alpha in the treatment of moderate-to-severe COVID-19: a randomised clinical trial. Ann. Med. 2021;Vol. 53:391–401. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1890329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pandit A., Bhalani N., Bhushan B.L.S., Koradia P., Gargiya S., Bhomia V., et al. Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2b in moderate COVID-19: A phase II, randomized, controlled, open-label study. Int J. Infect. Dis. IJID Publ. Int Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021;105:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]