Abstract

Inflammation observed in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients suggests that inflammasomes, proinflammatory intracellular complexes, regulate various steps of infection. Lung epithelial cells express inflammasome-forming sensors and constitute the primary entry door of SARS-CoV-2. Here, we describe that the NLRP1 inflammasome detects SARS-CoV-2 infection in human lung epithelial cells. Specifically, human NLRP1 is cleaved at the Q333 site by multiple coronavirus 3CL proteases, which triggers inflammasome assembly and cell death and limits the production of infectious viral particles. Analysis of NLRP1-associated pathways unveils that 3CL proteases also inactivate the pyroptosis executioner Gasdermin D (GSDMD). Subsequently, caspase-3 and GSDME promote alternative cell pyroptosis. Finally, analysis of pyroptosis markers in plasma from COVID-19 patients with characterized severe pneumonia due to autoantibodies against, or inborn errors of, type I interferons (IFNs) highlights GSDME/caspase-3 as potential markers of disease severity. Overall, our findings identify NLRP1 as a sensor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in lung epithelia.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, 3CL proteases, NLRP1 inflammasome, epithelial cells, Gasdermins, pyroptosis

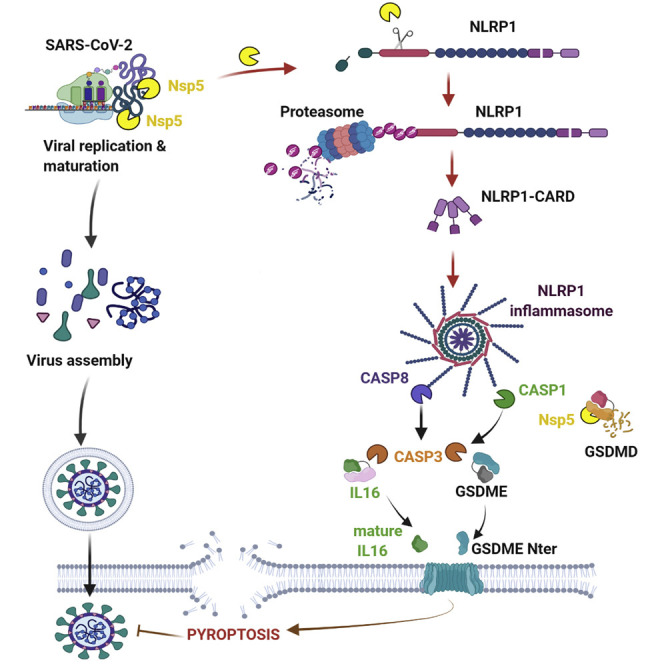

Graphical abstract

Planès et al. identify human NLRP1 as an immune sensor of SARS-CoV2 3CL protease.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has infected more than 219 million people worldwide. SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce multiorgan failure-associated sepsis with an increased risk in immune-deficient individuals and patients with particular pre-existing comorbidities (Al-Samkari et al., 2020; Cao, 2020; Carvalho et al., 2021; Berlin et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). Given SARS-CoV-2 initially infects nasal, bronchial, and lung epithelial cells, the host response in these cells can potentially control infection or may result in a response to SARS-CoV-2 that leads to excessive inflammation (Liu et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021).

Inflammasomes comprise an important response to viral infection. These cytosolic multiprotein complexes are composed of a receptor/sensor, the adaptor protein ASC (at the noticeable exception of the CARD8 inflammasome), and the proinflammatory protease caspase-1 (Broz and Dixit, 2016). Upon inflammasome assembly, caspase-1 autoactivates and processes proinflammatory cytokines of the interleukin (IL)-1 family, IL-1β and IL-18, as well as Gasdermin D (GSDMD) (Broz and Dixit, 2016). GSDMD cleavage activates a type of lytic cell death, pyroptosis, that also triggers the release of the cellular content (Broz and Dixit, 2016; Kayagaki et al., 2021). Although pyroptosis and IL-1-related cytokines are important defenses against a range of microbial infections, dysregulation of the inflammasome promotes excessive inflammation (Kayagaki et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2021). Specifically, IL-1-related cytokines are detected in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and are suspected to directly and indirectly contribute to severe COVID-19-linked sepsis (Cauchois et al., 2020; Cavalli and Dagna, 2021; Junqueira et al., 2021; Lucas et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2021; Yap et al., 2020).

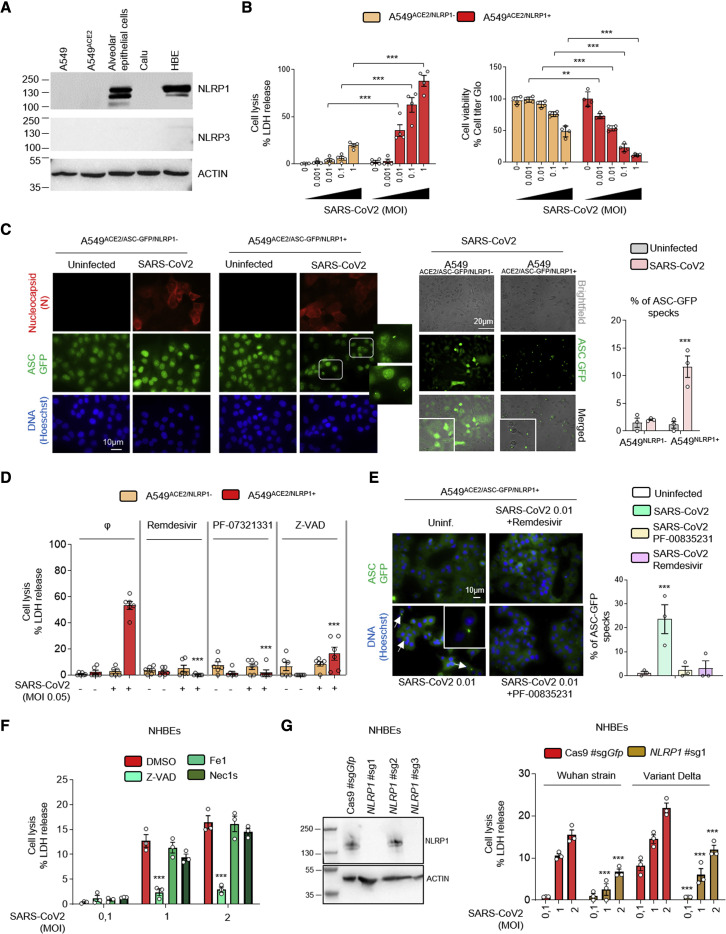

As previously described, immunoblotting analysis of the expression of inflammasome-forming sensors in human primary epithelial and cell lines highlights that primary bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells specifically express the inflammasome-forming sensor NLRP1 (Figures 1 A and S1A) (Bauernfried et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

NLRP1 is an innate immune sensor of SARS-CoV-2 infection

(A) Western blot examination of NLRP1, NLRP3, and ACTIN in various human epithelial cells and cell lines.

(B) Cell death (LDH) and viability (ATP Glo) evaluation in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and A549ACE2/NLRP1− airway epithelial cell lines infected with various multiplicity of infection (MOI) of SARS-CoV-2 for 24 h.

(C) Florescence microscopy and associated quantifications of ASC-GFP specks in A549ACE2/NLRP1+/ASC-GFP and A549ACE2/NLRP1−/ASC-GFP airway epithelial cell lines infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h. Nucleus was stained with Hoechst (blue), and nucleocapsid (N) was stained in red after fixation. Brightfield/ASC-GFP pictures were taken in dish during cell infection. Images shown are from one experiment and are representative of n = 3 independent experiments. For quantifications, the percentage of cells with ASC complexes was determined by determining the ratios of cells positives for ASC speckles on the total nuclei. At least 10 fields from n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(D) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549NLRP1+ and A549NLRP1− airway epithelial cell lines infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h in the presence/absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (25 μM), NSP5 protease inhibitor PF-00835231 (10 μM), or the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitor remdesivir (5 μM).

(E) Florescence microscopy and associated quantifications of ASC-GFP specks in A549ACE2/NLRP1+/ASC-GFP and A549ACE2/NLRP1−/ASC-GFP airway epithelial cell lines infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h. Nucleus was stained with Hoechst (blue). Brightfield/ASC-GFP pictures were taken in dish during cell infection. Images shown are from one experiment and are representative of n = 3 independent experiments; scale bars, 10 μm. For quantifications, the percentage of cells with ASC complexes was determined by determining the ratios of cells positives for ASC speckles on the total nuclei. At least 10 fields from n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(F) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in NHBE airway epithelial cells infected with various multiplicity of infection (MOI) of SARS-CoV-2 for 36 h in the presence/absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (25 μM), Necroptosis inhibitor Necrostatin-1s (Nec1s, 30 μM), or the Ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 (Fe1, 10 μM).

(G) Western blot characterization of genetic invalidation of NLRP1 in NHBE population using CRISPR-Cas9 and measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in NHBEWT and NHBENLRP1−/− airway epithelial cells infected with various multiplicity of infection (MOI) of Wuhan or Delta variant SARS-CoV-2 for 36 h. Efficiency of genetic invalidation by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs were evaluated at the whole cell population.

Data information: western blot (A and G) images are from one experiment performed 3 times. Graphs (B), (D), (F), and (G) show data presented as means ± SEM from n = 3 (F and G), n = 4 (B) and n = 6 (D) independent pooled experiments; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 for the indicated comparisons with t test. Images (C and E) are representative of one experiment performed 3 times.

NLRP1, a NOD-like receptor (NLR), exhibits a domain FIIND (function-to-find domain) that autocleaves NLRP1 into two proteins noncovalently connected (Chavarría-Smith et al., 2016; Chui et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2019; Okondo et al., 2018; Sandstrom et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2018). In this process, the proteases DPP8/DPP9 keep the C-Term CARD in an inactive conformation.

Pathogen-driven activation of the NLRP1 inflammasome can occur in the following different ways. First, cleavage of NLRP1 close to the N-terminal PYRIN domain can send N-terminal NLRP1 to the proteasome, thus allowing the C-terminal CARD domain to oligomerize and activate caspase-1 (Mitchell et al., 2019). This mechanism occurs when murine NLRP1B is exposed to the anthrax lethal factor (LF) protease (Chavarría-Smith et al., 2016; Chui et al., 2019; Sandstrom et al., 2019) and also in humans in response to enterovirus 3C cysteine proteases (Robinson et al., 2020; Tsu et al., 2021). Another mechanism that activates NLRP1 is binding of long double-stranded RNA detection to its NACHT- (NAIP [neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein], C2TA [MHC class 2 transcription activator], HET-E [incompatibility locus protein from Podospora anserina] and TP1 [telomerase-associated protein]) LRR (Leucine-Rich Repeats) domain. This mechanism also promotes inflammasome signaling in keratinocytes and bronchial epithelial cells infected with the RNA-positive (+RNA) strand Semliki Forest Virus (Bauernfried et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 is a +strand RNA virus that expresses two proteases, a 3CL-(3C-like) protease, namely NSP5, and a chymotrypsin protease, NSP3. Thus, here, we evaluate the ability of NLRP1 to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

NLRP1 triggers an inflammasome response upon SARS-CoV-2 infection of epithelial cells

NLRP1 is expressed in primary airway epithelial cells, but its expression is lost in various human tumor cell lines (Figures 1A, S1A, and S1B), limiting the ability to use these cells to analyze the innate immune response to viral infection. Therefore, we expressed hNLRP1 in the alveolar epithelial cell line A549ACE2. This cell line expresses endogenous ASC, caspase-1, and GSDMD (Figure S1A). Fluorescent (GFP)-tagged ASC was coexpressed in some experiments, allowing us to monitor inflammasome assembly upon NLRP1 activation and ASC polymerization (Figure S1B; Dick et al., 2016; Franklin et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2014). We activated NLRP1 using poly(I:C) or the pharmacological agent Val-boroPro (Val-boro) to evaluate the efficacy of our cell lines (Figures S1C–S1F; Johnson et al., 2018; Okondo et al., 2018). Transfection of poly(I:C) or treatment with various doses of Val-boro only triggered cell lysis in NLRP1-expressing cells (Figures S1C–S1E). In addition, only NLRP1-expressing cells contained ASC-GFP specks upon Val-boro treatment, indicating that this fusion protein can be used to monitor inflammasome assembly (Figure S1F).

Next, we infected A549ACE2/NLRP1+ or A549ACE2/NLRP1− cells with various multiplicity of infection (MOI) of SARS-CoV-2 and monitored for cell lysis (LDH release), cell viability (ATP levels), and inflammasome activation (ASC-speck formation) over time (Figures 1B–1D). We observed that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered a dose-dependent cell death of epithelial cells, a process that was dependent on the NLRP1 expression (Figures 1B and 1C). In addition, only cells expressing NLRP1 exhibited active inflammasome complexes upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, hence suggesting that NLRP1 is an innate immune sensor of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 1C). In addition, we observed that such process occurred in the presence of various SARS-CoV-2 variants, suggesting that NLRP1-driven response is not directly impacted by the appearance of those viral mutations (Figure S1G). Although primary bronchial epithelial cells and A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells do not express detectable levels of NLRP3, we controlled that NLRP3 was not involved in triggering this process by treating NHBEs and A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells with an inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome, namely MCC950 (Figures S1H and S1I). We observed no impact of MCC950 in the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to promote cell death or ASC-speck formation in either NLRP1+ or NLRP1− cells (Figure S1H). The efficacy of MCC950 was also tested in THP1 human monocyte cell line, which express detectable levels of NLRP3 and inhibited the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome upon exposure with the well-known toxin nigericin (Figure S1I).

Next, we explored the viral steps that were required for efficient NLRP1 inflammasome activation upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. We used two inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication, namely remdesivir that targets SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase and PF-00835231 that inhibits the activity of the 3CL NSP5 protease. Both inhibitors efficiently inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells as measured by the lack of appearance of the nucleocapsid (N) protein (Figure S1J). When we addressed the ability of both compounds to modulate SARS-CoV-2-dependent NLRP1 activation, we found that cell lysis (LDH release) levels as well as ASC-specks did not appear in presence of those inhibitors (Figures 1D and 1E). As control, those inhibitors did not show any effect in inhibiting NLRP1 inflammasome activation when cells were exposed to Val-boro (Figure S1K). Furthermore, the use of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD potently inhibited SARS-CoV-2-induced NLRP1-dependent cell death both in primary and in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells, suggesting that caspases are important regulators of this process (Figures 1D and S1J).

Finally, we aimed at determining the reproducibility of our observations in primary human epithelial cells. Hence, we used normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBEs) and evaluated the importance of NLRP1 in SARS-CoV-2-driven epithelial cell death. Infection of NHBE with various SARS-CoV-2 strains led to the induction of cell death, a process that was strongly impaired in presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD but not in presence of Necroptosis inhibitor Nec1s or the ferroptosis inhibitor Fe1 (Figures 1F and S1L), suggesting a critical function of caspases in SARS-CoV-2-driven epithelial cell death. Next, we generated genetic invalidation of NLRP1 gene expression using CRISPR-Cas9 in NHBE cells (Figure 1G). Infection of NHBEWT and NHBENLRP1−/− epithelial cells with SARS-CoV-2 showed a significant involvement of NLRP1 expression in NHBE cell lysis after 36 h of infection (Figure 1G), hence confirming that NLRP1-dependent cell death occurs both in cell lines and in primary epithelial cells.

Altogether, our results suggest that in airway epithelial cells, NLRP1 behaves as a sensor of SARS-CoV-2, a process that requires viral replication.

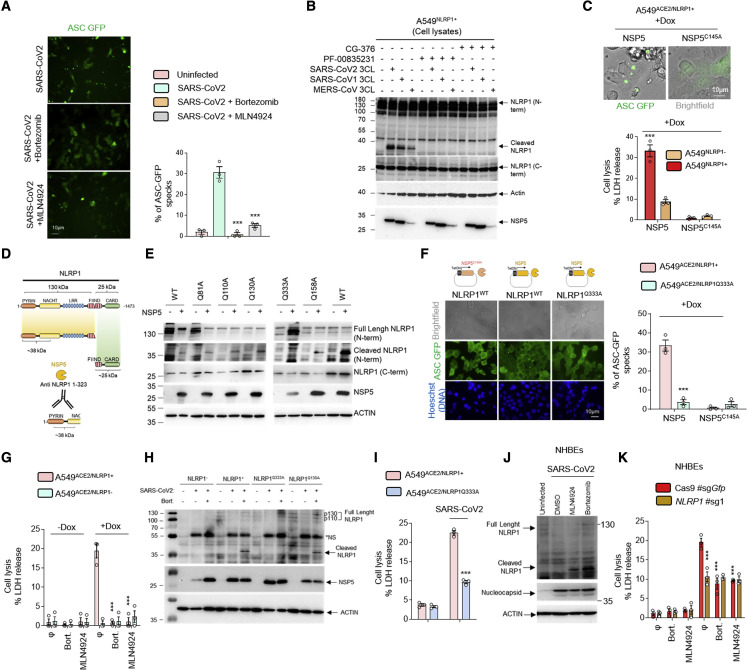

SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease-cleaved NLRP1 triggers inflammasome assembly

Next, we wondered about the viral effectors able to drive NLRP1 activation. Both dsRNA and HRV 3C proteases promote NLRP1 degradation by the proteasome system that induces an efficient inflammasome response, a process we also observed upon SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure S2A) (Bauernfried et al., 2021; Hollingsworth et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020; Sandstrom et al., 2019). However, 3C protease cleaves NLRP1 between Glutamine Q130 and Glycine G131 sites, which generates a free Nter 131Glycine. This allows the recruitment of the Ubiquitin-processing complex Cullin ZER1/ZYG11B and the targeting of ubiquitinated-NLRP1 for proteasome degradation and subsequent release and activation of the Cter UPA-CARD domain (Robinson et al., 2020). Consequently, we infected A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells with SARS-CoV-2 in the presence or absence of MLN4924, an inhibitor of the Cullin ZER1/ZYG11B complex, and evaluated the ability of cells to undergo cell lysis (Figure 2 A; Eldeeb et al., 2019). The use of MLN4924 markedly inhibited SARS-CoV-2-induced NLRP1-dependent ASC-speck formation (Figure 2A). This suggested us that a SARS-CoV-2-dependent proteolytic cleavage of NLRP1 might be of importance in triggering inflammasome response in epithelial cells. As SARS-CoV-2 expresses both a 3CL protease NSP5 and a chymotryspin protease NSP3, we hypothesized that one of those two proteases might cleave NLRP1 and generates a Glycine fragment accessible for Ubiquitination-driven NLRP1 degradation. Hence, we incubated NLRP1+ and NLRP1− cell lysates with recombinant NSP3 or NSP5 proteases and analyzed by immunoblotting their ability to process NLRP1 by using an anti-NLRP1 N-terminal antibody (generated with the NLRP1 N-term peptide 1–323 aa) (Figures 2B and S2B–S2E). We observed that NSP5 protease cleaved NLRP1 and generated a 38 kDa Nterm-sized peptide, a process that was inhibited by the 3CL protease inhibitor PF-00835231 (Figures 2B, and S2B–S2D). As other coronaviruses also express 3CL proteases, we also incubated lysates of NLRP1-expressing cells with the MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-1 3CL proteases. As for NSP5, both proteases also cleaved NLRP1 and generated an Nter fragment of similar sizes, suggesting a conserved ability of coronaviruses 3CL proteases to cleave NLRP1 (Figure 2B). Such process was also seen using recombinant NLRP1 protein in the presence of recombinant NSP5 proteases from pathogenic coronaviruses, hence suggesting that NSP5 alone is sufficient to mediate this process (Figures S2B and S2C). To further determine if NSP5 catalytic activity accounts at activating the NLRP1 inflammasome, we expressed doxycycline-inducible NSP5 or its catalytically inactive mutant (NSP5C145A) in NLRP1+ and NLRP1− cells. Monitoring for cell death and ASC-speck formation, we observed a strong ability of the WT NSP5 protease, but not its catalytically dead mutant, to promote both NLRP1-dependent cell death (LDH release) and GFP-ASC-speck formation, suggesting that NSP5 protease activity is required to nucleate an active NLRP1 inflammasome complex (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 protease-cleaved NLRP1 at the Q333 site nucleates NLRP1 inflammasome

(A) Florescence microscopy and associated quantifications of ASC-GFP specks in A549NLRP1+/ASC-GFP and A549NLRP1−/ASC-GFP airway epithelial cell lines infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (0.1 μM) or inhibitor of the glycine N-degron pathway MLN4924 (1 μM). Images shown are from one experiment and are representative of n = 3 independent experiments; scale barss 10 μm. For quantifications, the percentage of cells with ASC complexes was determined by determining the ratios of cells positives for ASC speckles on the total cells presents in the wells. At least 10 fields from n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(B) Western blot examination of NLRP1 cleavage using an anti-NLRP1 N-terminal antibody (aa 1–323) upon coincubation of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, or MERS-CoV 3CL (NSP5) proteases (5 μM) with A549NLRP1+ airway epithelial cell lysates in presence or absence of the 3CL inhibitors GC-376 (10 μM) or PF-00835231 (10 μM). NLRP1 N-terminal, NLRP1 C-terminal, NSP5, and ACTIN were immunoblotted.

(C) Florescence microscopy and associated quantifications of ASC-GFP specks in A549NLRP1+/ASC-GFP airway epithelial cell lines transduced with a doxycycline (dox)-inducible plasmid encoding NSP5 or its catalytically inactive mutant NSP5C145A. Images shown are from one experiment and are representative of n = 3 independent experiments; scale bars, 10 μm. For quantifications, the percentage of cells with ASC complexes was determined by determining the ratios of cells positives for ASC speckles on the total cells presents in the wells. At least 10 fields from n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(D) Schematic representation of the approximate NLRP1 N-terminal fragment generated by NSP5 protease cut.

(E) Western blot examinations of the ability of NSP5 to cleave various NLRP1 constructs mutated in glutamine (Q) at various sites. Immunoblots show anti-N-terminal NLRP1, ACTIN, and NSP5.

(F) Florescence microscopy and associated quantifications of ASC-GFP specks in A549NLRP1+/ASC-GFP or A549NLRP1Q333A/ASC-GFP airway epithelial cell lines transduced with a doxycycline (dox)-inducible plasmid encoding NSP5 or its catalytically inactive mutant NSP5C145A. Images shown are from one experiment and are representative of n = 3 independent experiments; scale bars, 10 μm. For quantifications, the percentage of cells with ASC complexes was determined by determining the ratios of cells positives for ASC speckles on the total nuclei (Blue). At least 10 fields from n = 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(G) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549NLRP1+ and A549NLRP1− airway epithelial cell lines expressing a doxycycline (dox)-inducible plasmid encoding NSP5 in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (0.1 μM) or inhibitor of the glycine N-degron pathway MLN4924 (1 μM).

(H) Western blot examination of NLRP1 cleavage using an anti-NLRP1 N-terminal antibody (aa 1–323) after infection of A549NLRP1−, A549NLRP1+ A549NLRP1Q333A, or A549NLRP1Q130A airway epithelial cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h in the presence/absence of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (0.1 μM, Bort.). NLRP1 N-terminal, NSP5, and ACTIN were immunoblotted. ∗NS: prominent nonspecific bands, not specific.

(I) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549NLRP1+ and A549NLRP1Q333A airway epithelial cell lines infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h.

(J) Western blot examination of NLRP1 cleavage using an anti-NLRP1 N-terminal antibody (aa 1–323) after infection of NHBEWT airway epithelial cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 1) for 36 h in the presence/absence of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (0.1 μM) or inhibitor of the glycine N-degron pathway MLN4924 (1 μM). NLRP1 N-terminal, nucleocapsid, and ACTIN were immunoblotted.

(K) Measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in NHBEWT and NHBENLRP1−/− airway epithelial cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 1) for 36 h in the presence/absence of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (0.1 μM) or inhibitor of the glycine N-degron pathway MLN4924 (1 μM).

Data information: images (A, C, and F) show one experiment performed 3 times. Western blot (B, E, H, and J) images are from one experiment performed 3 times. Graphs (C, G, I, and K) show data presented as means ± SEM from n = 3 independent pooled experiments; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 for the indicated comparisons with t test.

Next, we determined where NSP5 cleaves NLRP1. The 3CL protease NSP5 is predicted to cleave after Glutamine (Q) in the amino acid triad LQA, LQS, LQN, or LQG (Anand et al., 2003; Kiemer et al., 2004). In addition, our observation that the anti-NLRP1 Nter antibody (aa 1–323) detected a fragment of approximately 38 kDa allowed us to map cleavage to a region in the NLRP1 NACHT domain that contains the sequence 332LQG334 (Figures 2B–2D and S2D). Interestingly, protein alignments showed that this sequence is not conserved in murine Nlrp1B isoforms, suggesting that the NSP5-cleavage site in NLRP1 might be species specific (Figure S2D).

Therefore, we generated NLRP1-expressing constructs where Q333 is mutated to an Alanine (NLRP1Q333A). We also used previously generated NLRP1 constructs that carry various mutations in Glutamine (Q) at different positions in the Nter domain (Robinson et al., 2020). Lysates from cells expressing the different NLRP1 mutants were incubated with NSP5. The SARS-CoV-2 protease cleaved NLRP1 and generated 38 kDa fragments from all constructs with the exception of NLRP1Q333A (Figure 2E). To determine if the NLRP1Q333 site is important for NSP5-mediated NLRP1 inflammasome nucleation, we transduced ASC-GFP expressing cells with the NLRP1WT or the NLRP1Q333A construct and monitored for NSP5-induced ASC-speck formation and cell death. Cells expressing NLRP1WT exhibited ASC-GFP specks, cell death induction, and proteasome/Cullin ligase-dependency upon NSP5 expression (Figures 2F and 2G). In contrast, NLRP1Q333A-expressing cells did not show ASC-GFP specks or robust cell death upon NSP5 induction. We verified that the NLRP1Q333A construct was still functional using nonprotease activators of NLRP1. Hence, Val-boro treatment induced NLRP1WT- and NLRP1Q333A-dependent cell lysis, suggesting that the NLRP1Q333 site is specifically required for efficient NLRP1-dependent cell death upon NSP5 exposure (Figure S2E).

Then, we aimed at determining if SARS-CoV-2-infected epithelial cells also engage NSP5-dependent NLRP1 cleavage. We infected A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells with SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of bortezomib. Indeed, as NLRP1 cleavage leads to proteasomal degradation of the cleaved fragments, the used proteasome or Cullin ligase inhibitors allows cleaved fragment of NLRP1 accumulation and their putative observation by immunoblotting approaches. Thus, immunoblotting experiments against NLRP1 showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection in the absence of bortezomib did not allow detecting NLRP1 cleaved fragments (Figure 2H). However, treatment with bortezomib led to the detection of a cleaved NLRP1 fragment in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and A549ACE2/NLRP1Q130A cells, which was not seen in A549ACE2/NLRP1Q333A cells, hence suggesting that the NLRP1Q333 site is important for cleavage upon SARS-CoV-2 infection and can be significantly revealed when inhibiting proteasome-driven degradation (Figure 2H). Furthermore, A549ACE2/NLRP1Q333A cells showed greater resistance to cell death than A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells upon SARS-CoV2 infection, arguing that the Q333 site is important for efficient NLRP1 activation during viral infection (Figure 2I).

Finally, we performed NLRP1 immunoblotting in NHBE-infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 and also observed the accumulation of cleaved NLRP1 fragments in the presence of bortezomib or MLN4924 inhibitors (Figure 2J). Both bortezomib and MLN4924 inhibited SARS-CoV-2-dependent cell death in NHBEWT (Figure 2K). Altogether, our results suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 protease NSP5 activates the NLRP1 inflammasome by cleavage at the NLRP1Q333 site, a process that depends on a functional degradation pathway (Figure S2F).

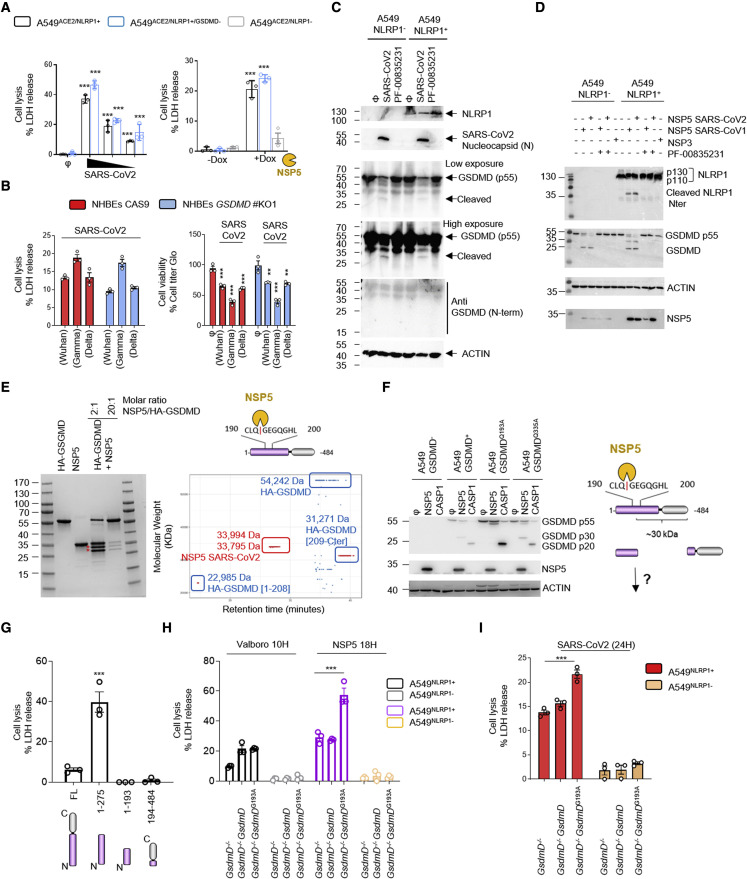

SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease dampens inflammasome signaling by inactivating Gasdermin D

In order to further understand the mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 infection impacts cells, we next examined NLRP1 downstream effectors that promote cell death. Once an inflammasome is nucleated, it licenses caspase-1 autoactivation. Subsequent cleavage of the pyroptosis executioner GSDMD activates this pathway. Using CRISPR-Cas9 editing, we generated GSDMD KO lines in NHBE and A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells and infected them with SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 3 A, 3B, and S3A). However, we failed to detect a reliable involvement of GSDMD at regulating NLRP1-dependent cell death upon SARS-CoV-2 infection or NSP5 induction (Figures 3A and 3B). Similarly, immunoblots of infected cell samples (combined supernatants and cell extracts) showed a decrease in the proform of GSDMD (antibody anti-GSDMD-Cter) but also intermediate cleavage bands of GSDMD (25–30 kDa) that do not correspond to the size of active GSDMD (N.B. When using the anti-GSDMD Cter antibody, the expected size of caspase-1-processed GSDMD is around 20 kDa) (Figure 3C). In addition, the use of an antibody that specifically recognizes the active Nter GSDMD fragment failed to detect any active GSDMD (Figure 3B). This result was consistent in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and A549ACE2/NLRP1− cells, suggesting that some protease-based, but inflammasome-independent, mechanism mediates this distinct processing of GSDMD (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

NSP5 protease cleaves Gasdermin D in its pore-forming domain

(A) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549NLRP1+, A549NLRP1−, or A549NLRP1+/GSDMD− airway epithelial cell lines infected for 24 h with SARS-CoV-2 (MOIs 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001) or stimulated with doxycycline (dox)-induced NSP5 expression.

(B) Measure of cell lysis (LDH release) and cell viability (Cell titer Glo) in NHBEWT and NHBEGSDMD−/− airway epithelial cells infected with various SARS-CoV-2 viral strains (MOI 1) for 36 h.

(C) Western blot examination of Gasdermin D (GSDMD) processing in A549NLRP1+ cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 at MOI of 0.1 for 24 h. GSDMD was immunoblotted using an anti-C-terminal antibody (recognizes full-length and C-terminal cleaved forms of GSDMD) or with an anti-GSDMD active N-terminal fragment (30 kDa) specific antibody. NLRP1, ACTIN, and SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid were also evaluated.

(D) Western blot examination of GSDMD and NLRP1 cleavages upon coincubation of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 protease or SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV1 3CL (NSP5) proteases (5 μM) with A549NLRP1+ or A549NLRP1− cell lysates in the presence or absence of the 3CL inhibitor PF-00835231 (10 μM). GSDMD (anti C-terminal), NLRP1 N-terminal, NSP5, and ACTIN were immunoblotted.

(E) Coomassie observation of recombinant GSDMD cleavage by various amounts of SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 protease and top-down mass-spectrometry identification of GSDMD-cleaved fragments. In blue are represented the various GSDMD fragments identified upon NSP5 coincubation. In red is the NSP5 protease detected by mass spectrometry.

(F) Western blot examination and schematic representation of GSDMD cleavage by SARS-CoV-2 3CL (NSP5) or recombinant human caspase-1 (CASP1) proteases in cell lysates from A549 expressing WT GSDMD or GSDMD193A constructs. GSDMD (anti-C-terminal), NSP5, and ACTIN were immunoblotted.

(G) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549 cells expressing doxycycline-inducible GSDMD fragments, including GSDMD full-length (FL), caspase-1-generated active GSDMD (1–275), or NSP5-generated 1–193 and 194–484 GSDMD fragments. Cell lysis was determined 18 h after doxycycline (dox) addition in the culture medium.

(H and I) Cell death (LDH) evaluation in A549NLRP1+/GSDMD− cells complemented or not with constructs coding for WT GSDMD or GSDMD193A. Cells were transduced with dox-inducible NSP5 plasmids, treated with the NLRP1 activator Val-boro (10 μM) or infected (I) with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.01). Cell lysis was determined 18 h after doxycycline (dox) addition, 10 h after Val-boro addition in the culture medium, or 24 h after infection.

Data information: graphs (A, B, G, H, and I) show data presented as means ± SEM from n = 3 independent pooled experiments; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 for the indicated comparisons with t test. Western blot (C, D, and F) images are from one experiment performed 3 times. Images (E) show one experiment performed 3 times.

In order to determine whether SARS-CoV-2-encoded enzymes influence GSDMD activation independently of NLRP1, we tested the hypothesis that the GSDMD intermediate bands are generated by a viral protease. Therefore, we checked whether NSP3 and NSP5 directly or indirectly cleave GSDMD. Coincubation of NSP3 and NSP5 proteases with cell lysates led to GSDMD cleavage at distinct sites from caspase-1, suggesting that the SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 protease can cleave GSDMD (Figures 3D and S3B). We also analyzed the ability of NSP5 to cleave other Gasdermins, including GSDME and GSDMB, both expressed in epithelial cells. However, although NSP5 can cleave GSDMD, the viral protease was unable to cleave GSDMB or GSDME (Figure S3B). Next, we checked whether NSP5-cleaved GSDMD is active. GSDMD was incubated with NSP5, and the resulting mixture was subjected to proteomic analysis. This approach detected GSDMD fragments corresponding to the Nter of GSDMD 1-Q193 (Figure 3E). In order to determine if NSP5 effectively cleaves at the Q193 site of GSDMD, we expressed GSDMDWT, GSDMD193A, or GSDMD335A encoding constructs in A549GSDMD cells. This approach was previously used to detect enterovirus EV71 3C protease-mediated cleavage at this site (Lei et al., 2017). Incubation of cell lysates with either NSP5 or recombinant human caspase-1 (CASP1) showed that CASP1 efficiently cleaved all GSDMD constructs (Figures 3F and S3C). However, we observed that NSP5 was unable to process GSDMDQ193A, suggesting that NSP5 cleaves GSDMD at the Q193 site (Figures 3F and S3C).

Next, we transfected plasmids encoding for NSP5-generated GSDMD fragments (1–193, 194–484) in A549 cells and monitored for their pore-forming activity by measuring cell lysis induction. Although caspase-1-generated GSDMD1–275 fragment showed strong lytic activity in A549 cells, none of the NSP5-generated fragments showed pore-forming activity, suggesting that NSP5-cleaved Nterm GSDMD inhibits GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis (Figure 3G). To test our hypothesis, we generated cell expressing GSDMD mutated in the NSP5 cleavage site. Expression of NSP5 protease in cells expressing NSP5-uncleavable GSDMD (GSDMD193A) exhibited enhanced cell death, a process that was lowered in cells expressing WT GSDMD (Figure 3H). To the contrary, Val-boro-induced cell lysis was not altered by the presence of GSDMD193A (Figure 3H). Finally, SARS-CoV-2 infection also induced higher cell death levels in GSDMD193A-expressing cells than that in parental cells, suggesting that GSDMD cleavage by NSP5 might lower the efficiency of GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis upon inflammasome activation in epithelial cells (Figure 3I). Those results suggest that NSP5 can also counteract the inflammasome signaling by directly targeting and inactivating GSDMD.

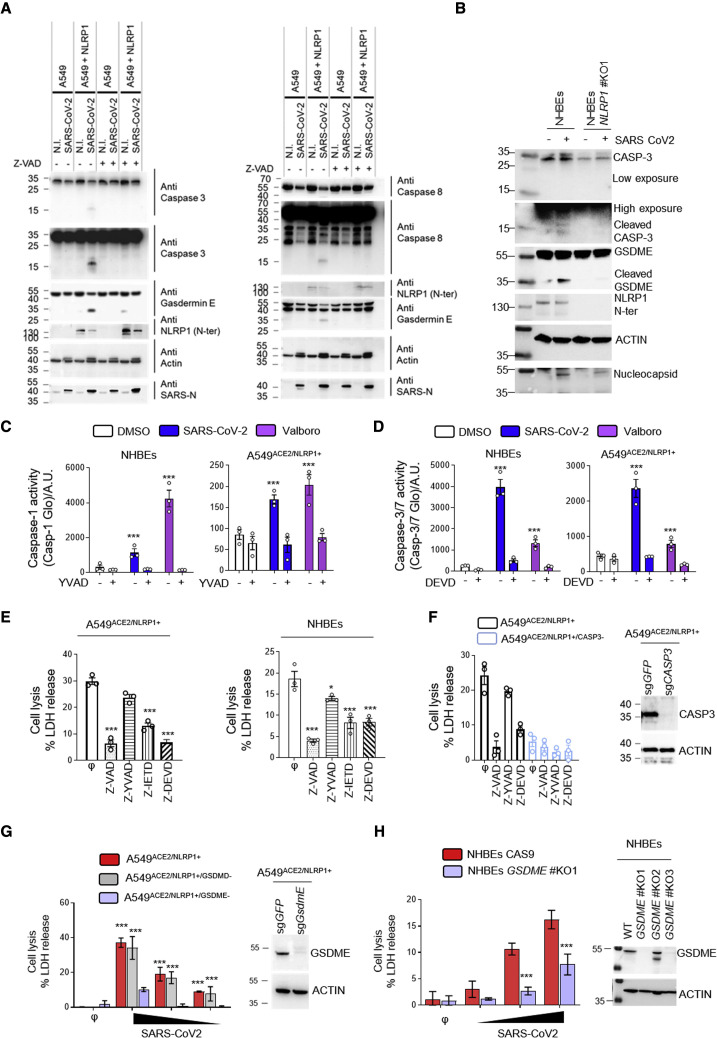

NLRP1-driven caspase-3 activation promotes Gasdermin E-dependent pyroptosis of airway epithelial cells

The ability of epithelial cells to undergo NLRP1-dependent cell death, even in the absence of GSDMD activation, suggests that additional cell death effectors might be activated by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Previous studies revealed that caspase-1 and/or caspase-8 are important for activating caspase-3 (CASP3)/Gasdermin E (GSDME)-dependent cell death in the absence of GSDMD expression (Heilig et al., 2020; Orzalli et al., 2021; Taabazuing et al., 2017; Tsuchiya et al., 2019; Zhou and Abbott, 2021). Depending on the cell type, CASP3/GSDME activation can trigger apoptosis, lytic apoptosis, or pyroptosis. We hypothesized that NLRP1 uses a distinct pathway involving caspase-3 and GSDMD to promote cell death upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. We tested for the presence of active caspase-8, active caspase-3, and cleaved GSDME in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells using immunoblotting. We observed the appearance of caspase-8 and caspase-3 active fragments as well as processed GSDME fragment in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and HBEWT but not in A549ACE2/NLRP1− or NHBENLRP1−/− cells (Figures 4A and 4B). In addition, the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD strongly impaired GSDME cleavage, suggesting that NLRP1-dependent caspase-8 and caspase-3 activation licenses GSDME cleavage (Figure 4A). Furthermore, quantitation of caspase-1 or caspase-3/7 activities in SARS-CoV-2-infected A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and NHBEWT cells revealed that the activity of both caspases is increased (Figures 4C and 4D). However, we noticed that the levels of caspase-1 activity in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells were extremely low (10 times lower) compared with those observed in NHBEWT cells (Figures 4C and 4D). Thus, to definitively determine if caspase-1 plays a role in SARS-CoV-2-driven epithelial cell death, we used specific inhibitors of caspase-8, caspase-1, and caspase-3 and monitored their ability to block NLRP1-dependent cell death upon SARS-CoV-2 infection both in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and in HBEWT cells. Although caspase-1 inhibition showed a negligible reduction in cell death both in A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and in NHBEWT cells, the most striking inhibition was observed in the presence of Z-VAD as well as the caspases-8 (Z-IETD)-specific and caspases-3 (Z-DEVD)-specific inhibitors (Figures 4E and 4F). These data suggest that in the absence of efficient GSDMD activation, NLRP1 triggers a compensatory pathway involving caspase-8 and caspase-3 in epithelial cells. As caspase-3 can cleave and activate GSDME, which generates pyroptosis in human keratinocytes (Orzalli et al., 2021), but not in macrophages or monocytes (Taabazuing et al., 2017), we explored whether the cell death we observed was caspase-3 and/or GSDME dependent. Hence, we generated A549ACE2/NLRP1+ cells deficient for either caspase-3 or GSDME and infected them with SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 4G). Analysis of cell death levels (LDH release) showed that both genetic removal caspase-3 and GSDME improved cell survival upon SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figures 4G and 4H). Finally, SARS-CoV-2 infection of primary NHBE cells in which GSDME was knocked out supported the hypothesis that GSDME is involved in NHBE lysis upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. In short, our data argue that both caspase-3 and GSDME initiate lytic cell death in airway epithelial cells upon SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 4I).

Figure 4.

NLRP1 engages a caspase-3/Gasdermin E-dependent pyroptosis pathway upon SARS-CoV-2 infection

(A) Western blot examination of Gasdermin E, caspases-3, and caspases-8 processing in A549NLRP1+ and A549NLRP1− cells after 24 h of infection with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) in the presence or absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (25 μM). Immunoblots were performed against full-length and processed forms of Gasdermin E (p55 and p30), caspase-8 (p54 and p15), caspase-3 (p35 and p17/19), SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (p40), NLRP1 N-terminal (p130/110), and ACTIN (p40).

(B) Western blot examination of Gasdermin E and caspases-3 processing in NHBEWT and NHBENLRP1−/− cells after 36 h of infection with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 1). Immunoblots were performed against full-length and processed forms of Gasdermin E (p55 and p30), caspase-3 (p35 and p17/19), SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (p40), NLRP1 N-terminal (p130/110), and ACTIN (p40).

(C and D) Measure of caspase-1 (C) and caspase-3/-7 (D) activities in SARS-CoV-2-infected (MOI 0.5) NHBEWT or A549NLRP1+ cells for 36 h in the presence or absence of inhibitors of caspase-1 (Z-YVAD, 40 μM) or caspase-3/-7 (Z-DEVD, 30μM). Val-boro (5 μM) was used a positive control of NLRP1-driven caspase activity for 10 H.

(E) Measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in A549NLRP1+ or NHBE-infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05 and 1, respectively) for 24 h in the presence/absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (25 μM), the caspase-1 inhibitor Z-YVAD (40 μM), the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD (40 μM), or the caspase-3 inhibitor Z-DEVD (30 μM).

(F) Western blot characterization of genetic invalidation of CASP3 in A549 population cells using CRISPR-Cas9 approaches and measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in A549NLRP1+ or A549NLRP1+/CASP3−-infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 0.05) for 24 h in the presence/absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (25 μM), the caspase-1 inhibitor Z-YVAD (40 μM), or the caspase-3 inhibitor Z-DEVD (30 μM). Efficiency of genetic invalidation by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting GFP or caspase-3 was evaluated at the whole cell population.

(G) Western blot characterization of genetic invalidation of GSDME in A549 population cells using CRISPR-Cas9 approaches and measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in A549NLRP1+, A549NLRP1+/GSDMD−, or A549NLRP1+/GSDME−-infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOIs 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1) for 24 h. Efficiency of genetic invalidation by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting GFP or GSDME was evaluated at the whole cell population.

(H) Western blot characterization of genetic invalidation of GSDME in NHBE population cells using CRISPR-Cas9 approaches and measure of cell lysis (LDH release) in NHBEWT or NHBEGSDME−/−-infected cells with SARS-CoV-2 (MOIs 0.1, 0.5, and 1) for 36 h. Efficiency of genetic invalidation by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting GFP or GSDME was evaluated at the whole cell population.

Data information: western blot (A, B, and E–G) images are from one experiment performed 3 times. Graphs (C–G) show data presented as means ± SEM from n = 3 independent pooled experiments; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 for the indicated comparisons with t test.

Altogether, our results underline the crucial function of apoptotic caspase-3 and pyroptotic GSDME as sentinels that trigger efficient epithelial cell death induction during SARS-CoV-2 infection if the canonical pyroptosis executioner GSDMD is inactive.

NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis restricts the generation of viral infectious particles and promotes the release of alarmins/DAMPs

Next, we wondered about the immunological and microbicidal importance of SARS-CoV-2-induced NLRP1 inflammasome activation in epithelial cells. We monitored the viral titers in A549ACE2/NLRP1+, A549ACE2/NLRP1−, or NHBEWT/NHBENLRP1−/− cells. Measuring the production of infectious particles by the TCID50 method, we observed that NLRP1-deficient cells were significantly more prone at generating SARS-CoV-2 viral particles (Figures S4A and S4B). However, we failed to see a robust involvement of NLRP1 at controlling SARS-CoV-2 replication as measured by the appearance of genes encoding SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase (Figure S4C). This suggested to us that pyroptosis might be a good mean to restrict the generation of mature and infectious viral particles but does not account as a direct replication inhibitory mechanism.

As pyroptosis is a very well-known process able to promote the release of specific caspase-associated inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1B/IL-18) but also various alarmins and DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), we next aimed at determining the importance of NLRP1 at regulating alarmins/DAMPs release upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. We specifically dedicated our analysis on already know alarmins and pyroptosis markers such as HMGB1, IL-18, and IL-1B, but also the caspase-3-derived alarmin interleukin-16 (IL-16). IL-16 is not an inflammasome-derived alarmin; however, its cleavage by caspase-3 allows its maturation and release. Hence, given the strong involvement of the caspase-3/GSDME axis in SARS-CoV2-dependent cell death, we also included IL-16 in our analysis as a read out of caspase-3-driven cytokine maturation and release. At the exception of IL-1B, all other alarmins/cytokines tested showed an NLRP1-dependent enrichment in the supernatant of infected A549ACE2/NLRP1+ and NHBEWT cells, hence confirming that NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis in epithelial cells generates robust alarmin and DAMP responses (Figures S4D and S4E).

Plasmatic levels of caspase-3/IL-16 and Gasdermin E are associated with COVID-19 severity

Intriguingly, a recent report unveiled that IL-18 and IL-16 are enriched in plasma from severe COVID-19 pneumonia patients, suggesting that the inflammasome route might contribute to the development of the pathology in sensitive patients (Lucas et al., 2020). However, our results suggest that at least in 2D epithelial cell cultures, NLRP1 exhibits some protective function against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure S4A). Regarding this, about 20% of patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia exhibit strong defect either in IFN response or in IFN production, suggesting that the IFN/inflammasome balance might be key in the regulation of COVID-19 severity (Asano et al., 2021; Bastard et al., 2020, 2021a, 2021b; Koning et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, to test this hypothesis, we expressed NLRP1 in A549ACE2 cells deficient for the expression of MAVS, a central modulator of interferon production upon SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figures S5A–S5C). We next infected A549ACE2/NLRP1−/MAVS+, A549ACE2/NLRP1+/MAVS+, A549ACE2/NLRP1−/MAVS−, and A549ACE2/NLRP1+/MAVS− cells with SARS-CoV-2 and monitored for cell death. We observed a very strong induction of NLRP1-dependent cell lysis in MAVS-deficient cells, when compared with MAVS-expressing cells after 24 h of infection, suggesting that in absence of a proper IFN response, SARS-CoV-2 hyper replication triggers NLRP1 over activation (Figure S5A). As consequence, the release of the caspase-3-derived alarmin IL-16 as well as IL-18 in the supernatant of MAVS-deficient cells was strongly increased in response to SARS-CoV-2 (Figure S5B). Relying on those observations, we hypothesized that in healthy patients, where the IFN and inflammasome responses are well balanced, NLRP1 might actually be protective, a process completely lost in absence of a proper IFN response.

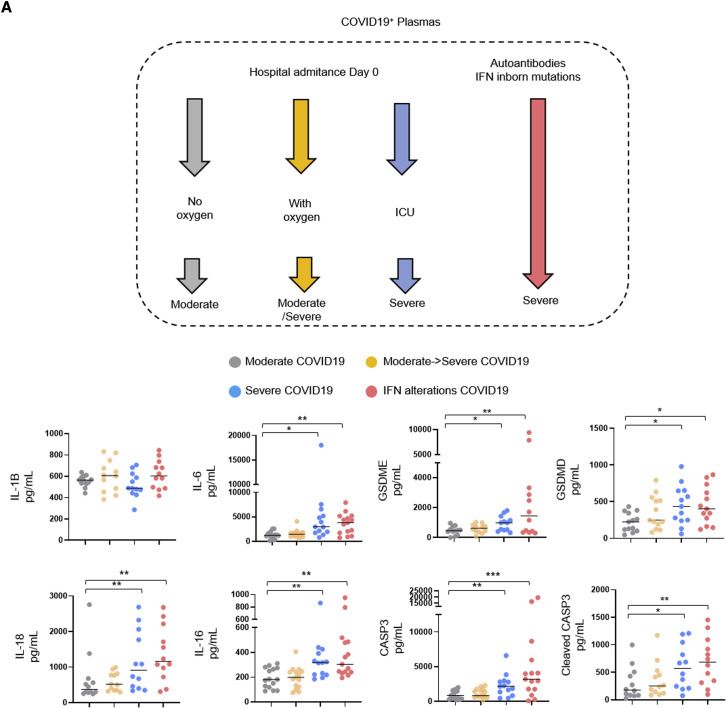

We obtained plasma samples from SARS-CoV-2 patients admitted at the hospital who exhibited three different profiles (WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterization and Management of COVID-19, 2020). First, patients with moderate (non-hypoxemic) COVID-19 pneumonia on admission and throughout their stay at the hospital (group “Moderate” with a WHO score of 5); second, patients with moderate COVID-19 on admission with subsequent clinical worsening and severe COVID-19 (WHO score >5) requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission (group “Moderate → Severe”); and third, patients with severe disease requiring ICU already on admission (group “Severe”) (Figures 5 A and S5D).

Figure 5.

Caspase-3/IL-16 and GSDME as potential markers of COVID-19 severity

(A) Measure of the presence of various inflammatory mediators in plasmas from hospitalized patients presenting COVID-19 disease and analyzed according to their disease severity degree (n = 60 patients, including 15 with moderate COVID-19, 15 with moderate COVID-19 on admission, 15 with severe COVID-19 on admission, and 15 IFN alterations with severe COVID-19). Samples were prepared at day 0 posthospitalization.

Data information: data shown as means from n = 12 different donors per category (moderate/moderate → severe/severe/IFN alterations); each category is represented with a colored circle; ∗ p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 for the indicated comparisons using t test with Bonferroni correction.

We sampled 10–15 patients from each category, and already in this small cohort, we were able to distinguish significant trends in the levels of various pyroptosis markers, including a strong correlation between increased levels of plasma caspase-3 (CASP3), cleaved caspase-3, IL-18, IL-16, GSDMD, and GSDME with the severity status of patients (Figure 5A). IL-6 also showed deep correlation with COVID-19 severity as previously described; however, we failed to detect significant differences in IL-1B levels among the different type of patients we assayed (Figure 5A). As genetic or acquired alterations in IFN signaling pathways account for patient sensitivity to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we also analyzed plasma from patients with critical disease due to either genetic inactivating mutations of type I IFN signaling (TBK1, IFNAR1, and IRF7) or developing high titers of autoantibodies against type IFNs (Bastard et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). As control, plasma from low/mid/severe patients were used to determine the relative differences of pyroptosis markers between those patients. All patients with IFN alterations showed a strong enrichment of IL-16, IL-18, CASP3, cleaved CASP3, GSDMD, and GSDME as previously seen with patients exhibiting severe COVID-19 (Figure 5A; Lopez et al., 2021; Wijst et al., 2021). Should NLRP1 specifically be involved will however require the development of more complex models such as humanized mouse for NLRP1. Nevertheless, our findings support a model between pyroptosis-associated markers and COVID-19 severity either in severe COVID-19 or in IFN-altered patients.

Discussion

Our study identifies NLRP1 as a central sensor of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease NSP5 but also highlights NSP5 as a virulence factor against GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis. In line with pioneering studies on the ability of picornavirus 3C proteases to cleave human NLRP1 at a different site (Q130-G131) and promote its activation, our study suggests that human NLRP1 is a broad protease sensor that carries evolutionary conserved decoy capabilities (Robinson et al., 2020; Tsu et al., 2021). Since human exposure to pathogenic coronavirus is relatively recent, how NLRP1 and GSDMD are so specifically targeted by viral proteases remains puzzling. Answers may come from future studies that test whether NLRP1 and GSDMD are targets of viral proteases from nonpathogenic coronaviruses. Regarding this, the 3C protease from EV71 enterovirus was shown to cleave and inactivate GSDMD at the 193Q site (Lei et al., 2017). It is tempting to speculate that 3C and the closely related 3CL proteases might share conserved targets. Beyond this, two recent studies showed a particular ability of the bacterial pathogen Shigella flexneri to ubiquitinate both GSDMD and GSDMB and target them for proteasomal degradation, thereby allowing Shigella to establish a replicative niche in human cells (Hansen et al., 2021; Luchetti et al., 2021).

Beyond epithelial detection of pathogenic coronavirus proteases by NLRP1, the cytokine storm observed in SARS-CoV-2 associates with a NLRP3 inflammasome signature mostly driven by myeloid cells. Whether exaggerated NLRP1 inflammasome activation or a lack of NLRP1 response directly or indirectly promotes an NLRP3-dependent response in patient myeloid cells is an important future question to pursue. Similarly, recent findings from Bhaduri-McIntosh lab identified SARS-CoV-2 Orf3a as a trigger of the NLRP3 inflammasome in epithelial cells (Xu et al., 2022). In our epithelial cell models, we failed to detect robust NLRP3 expression; however, we always worked in the absence of priming. Whether, priming with various PRR ligands might promote NLRP3 expression in epithelial cells warrants further investigations.

Induction of a well-balanced innate immune response is central to controlling microbial infections, including those triggered by pathogenic coronaviruses (Broggi et al., 2019; Schultze and Aschenbrenner, 2021; Tay et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). Consequently, any delay in a robust type I interferon production/response exposes the host to robust viral replication and exacerbated inflammation, leading to heavy organ damage (Asano et al., 2021; Bastard et al., 2020, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c; Galani et al., 2020; Hadjadj et al., 2020; Koning et al., 2021; Zanoni, 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Our insights into NLRP1 inflammasome activation upon SARS-CoV-2 infection of epithelial cells in vitro suggest that NLRP1-driven inflammation might be both beneficial and detrimental in COVID-19 patients.

Overall, our results place the NLRP1 inflammasome as an innate immune sensor of the SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease but also highlight the virulence mechanisms by which this devastating virus counteracts cell intrinsic immunity.

Limitations of the study

The lack of conservation of the NLRP1 proteins between mice and humans strongly limits the physiopathological translation of our results into a broader and more complex model such as mice. The generation of humanized models in the future should help to determine the importance of the NLRP1 inflammasome in pathogenic coronavirus infections. Finally, although NLRP1 might be of importance to generate proinflammatory mediators at the epithelial barrier level, its role in the development of a cytokine storm observed in patients exhibiting severe COVID-19 has not been formally demonstrated in our study, which will require further investigations.

Consortia

The members of the COVID Human Genetic Effort are Tayfun Ozcelik, Nevin Hapitoglu, Filomeen Haerynck, Sevgi Keles, Ahmed A. Bousfiha, and Rafael Leon Lopez. For affiliation information, see the supplemental information.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti- Gasdermin D (N-terminal), 1: 1000 | ab215203;RRID: AB_2916166 | Abcam |

| Anti- Gasdermin D (C-terminal), 1: 1000 | ab210070;RRID: AB_2893325 | Abcam |

| Anti- NLRP1 (N-terminal), 1: 1000 | AF6788-SP;RRID: AB_2916167 | R&D system |

| Anti- NLRP1 (C-terminal), 1: 1000 | ab36852;RRID: AB_776633 | Abcam |

| Anti -ACE2, 1: 1000 | ab108252;RRID: AB_10864415 | Abcam |

| Anti -TMPRSS2, 1: 1000 | ab92323;RRID: AB_10585592 | Abcam |

| Anti-actin 1: 5000 | A1978;RRID: AB_476692 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| anti-Sheep igG HRP (1/4000) | HAF016;RRID: AB_562591 | R&D |

| Goat anti-mouse HRP (1/4000) | 1034-05;RRID: AB_2794340 | SouthernBiotech |

| Goat-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), HRP conjugate (1/4000) | R-05072-500;RRID: AB_10719218 | Advansta |

| Rabbit anti-Goat IgG (H+L) Secondary Antibody, HRP (1/4000) | 81-1620;RRID: AB_2534006 | Invitrogen |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H&L) - Affinity Pure, DyLight®550 Conjugate (1/1000 IF) | DkxRb-003-D550NHSX;RRID: AB_2916168 | ImmunoReagents |

| Anti Caspase 8 (1: 1000) | ALX-804-242-C100;RRID: AB_2050949 | Enzo Life |

| Anti Caspase 1 (1: 1000) | AG-20B-0048-C100;RRID: AB_2916169 | Adipogen |

| Anti Caspase 3 (1: 1000) | 9662S;RRID: AB_331439 | Cell Signaling |

| Anti gasdermin E (1: 1000) | Ab215191;RRID: AB_2737000 | Abcam |

| Anti SARS NSP5 (1: 1000) | NBP3-07061;RRID: AB_2916170 | Novusbio |

| Anti SARS Nucleocapsid (1: 1000) | NB100 56683;RRID: AB_838841 | Novusbio |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| BetaCoV/France/IDF0372/2020 | Sylvie van der Werf and the National Reference Centre for Respiratory Viruses | Institut Pasteur (Paris, France) |

| hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021 (Delta Variant) | BEI | |

| hCoV-19/USA/OR-OHSU-PHL00037/2021 (Alpha Variant) | BEI | |

| hCoV-19/Japan/TY7-503/2021 (Gamma Variant) | BEI | |

| Biological samples | ||

| Plasma from Covid patients | Covid Biotoul cohort/Toulouse, France | Hospital of Toulouse |

| Plasma from patients with inborn mutations or autoantibodies | Institut Imagine/Covid genetic effort | Institut Imagine, Paris/France |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Z-VAD: 40 μM | tlrl-vad | Invivogen |

| Y-VAD: 40 μM | inh-yvad | Invivogen |

| Z-DEVD: 40 μM | S7312 | Selleck Chemicals |

| Z-IETD: 40 μM | inh-ietd | Invivogen |

| MCC950: 10 μM | inh-mcc | Invivogen |

| VX765: 10 μM | inh-vx765i-1 | Invivogen |

| DMF: 10 μM | S2586 | Selleck Chemicals |

| MLN4924: 1 μM | 6499 | Tocris |

| Remdesivir: 5 μM | 282T7766 | Tebubio |

| Bortezomib: 0,1 μM | S1013 | Selleck Chemicals |

| PF-00835231: 10 μM | S9731 | Selleck Chemicals |

| CG-376 | SE-S0475 | Euromedex |

| Nigericin | tlrl-nig-5 | Invivogen |

| Hoescht | 62249 | Invitrogen |

| Poly(I:C) HMW | tlrl-pic | Invivogen |

| Nate | lyec-nate | Invivogen |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | 11668030 | Invitrogen |

| Lipofectamine LTX | 15338030 | Invitrogen |

| Doxycycline | S5159 | Selleck chemicals |

| Recombinant human IL-18 | (rcyec-hil18) | Invivogen |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| IL-1B | 88-7261-77 | Fisher Scientific |

| IL-6 | 555220 | BD |

| IL-16 | DY316 | R&D |

| Caspase 3 | BMS2012INST | Invitrogen |

| Gasdermin E | AG-45B-0024-KI01 | Adipogen |

| HMGB1 | NBP2-62766 | Novusbio |

| Deposited data | ||

| Original blots and microscopy images | https://doi.org/10.17632/nwhd3w9w5x.1 | Mendeley dataset |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| THP1 KO NLRP3 | Thp-konlrp3z | Invivogen |

| THP1 | Thp-null | Invivogen |

| A549 | A549d-nfis | Invivogen |

| A549-Dual™ ACE2 & TMPRSS2 | a549d-cov2r | Invivogen |

| A549-Dual™ KO-MAVS Cells | a549d-komavs | Invivogen |

| A549 ACE2 & TMPRSS2 Cells | a549-hace2tpsa | Invivogen |

| IL-18 Reporter HEK 293 Cells | (hkb-hmil18) | Invivogen |

| Lonza, B-ALI kit 00193514 | 00193514 | Lonza |

| Corning HTS Transwell-24 well permeable supports | CLS3379 | Corning |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| LentiCas9-Blast | addgen ref 52962 | (Sanjana et al., 2014) |

| p8.91 | Didier Trono lab | Didier Trono lab |

| pMD.2G | addgene ref 12259 | Didier Trono lab |

| LentiGuide-Puro | addgen ref 52963 | (Sanjana et al., 2014) |

| Vector pLVX-EF1α-IRES-Puro Containing the SARS-CoV-2, USA-WA1/2020 3C-Like Protease Gene, C145A Mutant | BEI NR-52953 | BEI |

| pLEX307-SARS-CoV-2-3CL (NSP5) | addgene #160278 | (Resnick et al., 2021) |

| pSC2+ NLRP1 constructs | (Robinson et al., 2020) | |

| pLV-72-Cas9-GFP | N/A | Invivogen |

| pLVB-Tet ON | N/A | Invivogen |

| pLVB-TetR | N/A | Invivogen |

| pBRGEN | N/A | Invivogen |

| pMSCV-puro | Addgene plasmid # 68469 | (Akama-Garren et al., 2016) |

| pMSCV-GsdmB | GeneScript | N/A |

| pMSCV-GsdmE | GeneScript | N/A |

| pMSCV-GsdmD | GeneScript | N/A |

| pCW57-RFP- P2A-MCS | Addgene #89182 | (Barger et al., 2021) |

| LENTI V2 plasmid | Addgene 52961 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin E (Exon 2) | CAGTTTTTATCCCTCACCCT | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin E (Exon 2) | TAAGTTACAGCTTCTAAGTC | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin E (Exon 3) | GTCGGACTTTGTGAAATACG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Casp1 (Exon 2) | TTGTGAAGAAGACAGTTACC | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Casp1 (Exon 4) | AAGGATATGGAAACAAAAGT | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin D (Exon 5) | TTAGGAAGCCCTCAAGCTCA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin D (Exon 6) | GAATGTGTACTCGCTGAGTG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Gasdermin D (Exon 5) | AGGTTGACACACTTATAACG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Caspase 3 (Exon 4) | CATACATGGAAGCGAATCAA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting Caspase 3 (Exon 5) | TGTCGATGCAGCAAACCTCA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting MAVS | ACCTCAGCAGATGATAGGCTCGGCC | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting MAVS | ACCTCGCCCATCAACTCAACCCGTGC | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting NLRP1 (Exon 2) | GCTCAGCCAGAGAAGACGAG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting NLRP1 | GATAGCCCGAGTGACATCGG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting NLRP1 | AGCCCGAGTGACATCGGTGG | Sigma-Aldrich |

| sgRNA targetting GFP | GGAGCGCACCATCTTCTTCA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Fwd Q333A | GAACCTCGCATAGTCATACT GGCGGGGGCTGCTGGAATTGGGAAG |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| Rev Q333A | CTTCCCAATTCCAGCAGCCCCCGCCA GTATGACTATGCGAGGTTC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q335A fwd2 | GGCGCTGGAGgccGGCCAGAGCCTT GGGCC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q335 rev2 | cgcaaccccaaccccggatccCTAGTGGGG CTCCTGGCTC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q193 fwd | cagatcgcctggagaattggctagcATGTACCCA TACGATGTTCCA |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q193 rev | cgcaaccccaaccccggatcctcaCTGCAAGC ACGTGGCTC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD N-ter fwd | cagatcgcctggagaattggctagcATGTACCC ATACGATGTTCC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD N-ter rev | cgcaaccccaaccccggatcctcaATCTGTCA GGAAGTTGTGG |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q193 fwd1 | aggcgccggaattagatctctcgagatggactaca aagacgatgacgacaagGGTGGAGGTGGA GGTGGA |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q193A rev1 | GGCCCTCACCggcCAAGCACGTGGC TCCGG |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q193A fwd2 | CACGTGCTTGgccGGTGAGGGCCAG GGCCAT |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q193 rev2 pMSCV | ctcccctacccggtagaattcCTAGTGGGGC TCCTGGCTC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q335 fwd1 | aggcgccggaattagatctctcgagatggacta caaagacgatgacgacaagGGTGGAGG TGGAGGTGGAG |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q335A rev1 | GGCTCTGGCCggcCTCCAGCGCC TCCTCCAA |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| HA-GsdmD Q335A fwd2 | GGCGCTGGAGgccGGCCAGAGC CTTGGGCC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| GsdmD Q335 rev2 pMSCV | ctcccctacccggtagaattcCTAGT GGGGCTCCTGGCTC |

Sigma-Aldrich |

| Recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant SARS-COV 3CL | E-718-050 | Novusbio |

| Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 3CL | E-720-050 | Novusbio |

| Recombinant MERS-CoV 3CL | E-719-050 | Novusbio |

| Recombinant human caspase-1 protein (active) | Ab39901 | Abcam |

| Nsp3, peptidase C16 of PLpro | PX-COV-P004 | proteogenix |

| HRV3C Protease | SAE0045 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Snapgene | GSL Biotech LLC, Chicago, U.S.A. | N/A |

| Fiji (Image J) | N/A | |

| Benchling Software | N/A | |

| Image Lab 6.1 (Biorad) | N/A | |

| Biorender.com | N/A | |

| Graphpad 8.0a | N/A | |

| Uniprot database | N/A | |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents listed in method details and key resources table sections should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Etienne Meunier, Etienne.meunier@ipbs or Emmanuel Ravet, e.ravet@invivogen.com

Regarding the experimental model and subject details that relate to medical aspects of this study, request of information must be sent to jean-laurent.casanova@inserm.fr and Guillaume-martin.blondel@chu-tlse.fr

Materials availability

Plasmids generated in this study are freely accessible upon request.

Cell lines generated in this study are freely accessible upon request and a completed Material Transfer Agreement (MTA).

Experimental model and subject details

Safety procedures

All described experiments involving SARS-CoV-2 infections (Microscopy of infected cells, Cell death assays, ELISA, sample preparation for Immunoblotting, virus production, TCDI50, RNA extraction) have been entirely performed and processed in a Biosafety Level 3 facility.

Ethical approvals of human studies

COVID-BioToul

Clinical data and blood samples for plasma isolation and cryopreservation were collected at the Toulouse University Hospital, France, in the frame of the COVID-BioToul biobank (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04385108). All donors had given written informed consent and the study was approved by the ethical review board “Comité de Protection des Personnes Est-III” (ID-RCB 2020-A01292-37). Plasma samples were collected on admission to the hospital for COVID-19 proven by a positive PCR performed on respiratory samples. COVID-19 patients were graded according to the severity on admission and on maximum severity during their hospitalization based on The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ordinal scale (WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19, 2020). Patients were considered as having moderate disease when they required oxygen by mask or nasal prongs (WHO grade 5), and severe disease when they required high flow oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, or extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (WHO grade >5). Three groups of non-immunocompromised patients were identified for the purpose of this study: patients with moderate COVID-19 on admission and throughout their stay at the hospital (group “Moderate”); patients with moderate COVID-19 on admission with subsequent clinical worsening and severe COVID-19 requiring ICU admission (group “Moderate/Severe”); and patients with severe disease requiring ICU already on admission (group “Severe”). Mean age of COVID-19 patients was 60.8 ± 12 years, the percentage of females was 24.4.

Plasma from patients with interferon alterations

15 plasmas from patients with life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia who developed critical disease (Bastard et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020) were obtained. Specifically, 3 patients exhibited inborn autosomic recessive (AR) or autosomic dominant (AD) mutation in genes encoding for interferon production/response, including AD TBK1 (MB019430), AR IRF7 (MB019096) and AR IFNAR1 (MB019091) (Zhang et al., 2020). The 12 other plasma samples came from COVID-19 patients with proven auto-antibodies to IFNα2/IFNw (Figure S5D; Bastard et al., 2020).

All donors had given written informed consent and the study was approved by local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

COVID-19 disease severity was assessed in accordance with the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. The term life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia describes pneumonia in patients with critical disease, whether pulmonary, with mechanical ventilation [continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP), intubation, or high-flow oxygen], septic shock, or damage to any other organ requiring admission in the intensive care unit (ICU) (Bastard et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Plasma and serum samples from the patients were frozen at −20°C immediately after collection.

Cell culture

Vero E6, Calu, THP1, HEK 293FT, THP1Nlrp3-/- and A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine.

Primary airway epithelial cells were from Epithelix and NHBE cells were from Lonza (CC-2540 and CC-2541).

Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial (NHBE) cell Air-Liquid interface (ALI) culture

NHBE cell culture was performed as suggested by the manufacturer (Lonza, B-ALI kit 00193514). Briefly, cells were seeded onto collagen-coated (0.03mg/mL) HTS Transwell-24 well permeable supports (Corning, CLS3379) at a density of 5. 104 cells per insert for three days in B-ALI Growth Medium (Lonza, B-ALI kit 00193514). Cells were then cultured at the air-liquid interface in B-ALI Differentiating Medium (Lonza, B-ALI kit 00193514) at 37°C/5%CO2 for 20 days, with a medium change every two days.

For SARS infections, 100μL of 5.104 (MOI 0.5), 1. 105 (MOI 1) or 2.105 (MOI 2) viral inoculum were added on cells for 3 hours. After washing two times the cells, medium was then replaced by B-ALI Differentiating Medium and cells were incubated for 24-36 hours before cell processing for further experiments.

For histological experiments, primary NHBEs were fixed for 30 minutes then processed using a Tissue-Tek VIP 6 and embedded using a Tissue-Tek TEC 5 (Sakura). Transwells were bisected and embedded vertically before sectioning. Serial paraffin sections (4 μm) were prepared using a RM2135 rotary microtome (Leica), then deparaffinised with xylene and rehydrated with graded ethanols and water. For immunohistochemical staining, sections were heated for 15 minutes at 98°C in a citrate acid-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories), then endogenous peroxidase activity blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes. Slides were stained in goat serum (1:5; G9023, Sigma) containing mouse monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike (1:1000; GTX632604, GeneTex) for 90 minutes at 37°C. Following washing with TBS, sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins/HRP (1:100; Dako) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Staining was visualised by application of diaminobenzidine for five minutes. For Alcian blue/periodic acid – Schiff (AB-PAS) staining, slides were stained in 1% Alcian blue in 3% acetic acid (Pioneer Research Chemicals) for five minutes, washed with water, then oxidised in 1% aqueous periodic acid (Acros Organics) for five minutes. Following another washing step, sections were stained in Schiff reagent (Thermo Fisher) for 10 minutes. All slides were counterstained with haematoxylin to stain the nuclei and mounted in DPX Mountant (Sigma-Aldrich) using a CV5030 fully automated glass coverslipper (Leica), then digitally scanned using a Nanozoomer 2.0HT at 40x objective (Hamamatsu).

Method details

Cell engineering

To reconstitute the NLRP1 inflammasome pathway in A549, cells were transduced with VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral vector carrying the NLRP1 gene (NCBI accession NP001028225.1) and/or asc (NCBI accession NP037390.2) fused to gfp. To render cells permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infections cells were transduced with VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral vector carrying the ace2 (NCBI accession NP068576.1) and tmprss2 (NCBI accession NP001128571.1) genes. Engineered A549 cell lines were characterized for NLRP1, ASC-GFP, ACE-2 and TMPRSS2 expression by q-RT-PCR, immunoblot and flow cytometry.

To generate cells stably expressing GSDMD gene mutated for protease cleavage sites (GSDMDQ193A and GSDMDQ335A) we reconstituted GSDMD deficient cells with full length or mutated GSDMD constructs (GSDMDQ193A and GSDMDQ335A). Cells were transduced with VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral vector carrying different GSDMD constructs in presence of 8μg/ml polybrene and centrifugated for 2h at 2900 rpm at 32°C. 48 h later, medium was replaced and Puromycin selection (1μg/mL) was applied to select positive clones for two weeks.

Generation of mutations in Gasdermin D gene

To express the N- terminal and C-terminal fragments of GSDMD generated following cleavage by Sars-CoV-2 3CL protease we used the following strategy: 1) nucleotide sequence coding for the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of GSDMD peptides were generated following proteases cleavage by using SnapGene software; 2) N-terminal and C- terminal GSDMD coding sequence were generated by PCR with the addition of a 5’ Start codon ATG and 3’ Stop codon TGA; 3) Amplified PCR fragments were cloned into pCW57-RFP- P2A-MCS lentiviral vector plasmid between BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. This system allows ectopic expression of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of GSDMD in order to study their activity.

To generate cells stably expressing Gsdmd gene mutated for protease cleavage sites (mutations GSDMDQ193A and GSDMDQ335A) we introduced point mutations in the GSDMD coding sequence by overlapping PCR and cloned mutated GSDMD in pMSCV-puro vector between BamHI and NotI restriction sites. Restriction enzymes were all from New England BioLabs. All the construct generated were verified by DNA sequencing (Eurofins genomics). Primers of the different constructions are listed in key resources table.

Generation of mutations in NLRP1 gene

The transient expression plasmid of NLRP1Q333A was cloned into the pCS2+ vector using standard restriction cloning using ClaI and XhoI flanking the open reading frames. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out with QuickChangeXL II (Agilent #200522) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers:

Rev Q333A: CTTCCCAATTCCAGCAGCCCCCGCCAGTATGACTATGCGAGGTTC

Fwd Q333A: GAACCTCGCATAGTCATACTGGCGGGGGCTGCTGGAATTGGGAAG

Generation of doxycycline-inducible plasmids

To generate doxycycline-inducible SARS-CoV-2 3-CL protease (NSP5) constructs, WT NSP5 or NSP5C145A were amplified by PCR from pLEX307-SARS-CoV-2-3-CL and pLVX-EF1α-IRES-Puro 3CLC145A template respectively. PCR products were digested with AgeI and NheI restriction ezymes and digested insert were ligated in pLVB-TetON vector between AgeI and NheI restriction sites. To generate cell lines nsp5-inducible A549 cell lines, cells were transduced with both pLVB-nlr-TetR and pLVB-TetON-NSP5.

Primer1 (44-mer): ATTTATATTAACCGGTATGAGTGGTTTTAGAAAAATGGCATTCC

Primer2(45-mer): AATTATAATGCTAGCTTATTGGAAAGTAACACCTGAGCATTGTC

Cell transfection/transduction

A549 transfected with NLRP1 mutated plasmids

The day prior to the transfection, 2 x 105 A549 cells were plated in 6 well plate in 10% FBS DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The day after, cells were treated with Nate 1X (Invivogen) for 30 min. DNA-lipids complexes were prepared with 1μg of pCS2+ NLRP1 mutated plasmids (Robinson et al., 2020) or pCS2+ NLRP1Q333A, lipofectamine LTX and PLUS reagent diluted in Opti-MEM and incubated for 30 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). DNA-lipid complexes were added to cells and incubated O/N at 37°C in 10% FBS DMEM.

A549 transfected with Gasdermin d plasmids

The day prior to the transfection, 2 x 105 A549 dual cells were plated in 6 well plate in 10% FBS DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The day after, DNA-lipids complexes were prepared with 1μg of GSDMDNT pcW57 plasmids and polyethylenimine (PEI) diluted in Opti-MEM. DNA-lipid complexes were added to cells and incubated for 48h at 37°C in Opti-MEM (Fischer Scientific).

SARS-CoV-2 production and infection

Experiments using SARS-CoV-2 virus were performed in BSL-3 environment. The BetaCoV/France/IDF0372/2020 isolate was supplied by Sylvie van der Werf and the National Reference Centre for Respiratory Viruses hosted by Institut Pasteur (Paris, France). The patient sample from which strain BetaCoV/France/IDF0372/2020 was isolated was provided by X. Lescure and PY. Yazdanpanah from the Bichat Hospital, Paris, France. The mNeonGreen (mNG) (Xie et al., 2020) reporter SARS-CoV-2 were based on 2019-nCoV/USA_WA1/2020 isolated from the first reported SARS-CoV-2 case in the USA, and provided through World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA), and UTMB investigator, Dr. Pei Yong Shi. SARS-CoV-2. Isolate hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021 (Delta Variant), SARS-CoV-2, Isolate hCoV-19/USA/OR-OHSU-PHL00037/2021 (Alpha Variant) and SARS-CoV-2, Isolate hCoV-19/Japan/TY7-503/2021 (Gamma Variant) were obtained from BEI.

SARS-CoV-2 isolates were amplified by infecting Vero E6 cells (MOI 0.005) in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10mM HEPES and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The supernatant was harvested at 48 h post-infection when cytopathic effects were observed, cell debris were removed by centrifugation, and aliquots were frozen at −80°C. Viral stocks were titrated by plaque assays in Vero E6 cells. Typical titers were 5 to 10× 106 PFU/ml.

The day prior to infection, 50,000 or 250,000 A549-ACE2-TMPRSS2, expressing or not NLRP1, cells were seeded in 96-well or 24-well tissue culture plates respectively in 10% FBS DMEM supplemented with 10mM HEPES (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and then incubated overnight at 37 ◦C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere-enriched chamber. The day after, cells were infected with mNeonGreen SARS-CoV-2 or the BetaCoV/France/IDF0372/2020 strains at indicated MOI in 50 μl DMEM supplemented with 10mM Hepes, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-Glutamine for 1h at 37°C. Then, culture medium was completed up to 200 μl with DMEM or Opti-MEM.

Virus titration by TCID50 calculation

The day prior to infection, 50,000 VeroE6 cells per well were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates using 10% FBS DMEM, and then incubated overnight at 37 ◦C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere-enriched chamber. On the day of infection, serial 2.5-fold dilutions (from 10−1 to 10−6.5) of the A549 cell culture supernatant were prepared in DMEM and used to infect Vero E6 cells; each dilution was tested in four replicates. The plates were incubated for at least 96 h and observed to monitor the development of cytopathic effect (CPE) using an EVOS Floid microscope (Invitrogen). Viral titers, expressed as TCID50/mL, were calculated according to both Reed and Muench and Karber methods based on three or four replicates for dilution (Reed and Muench, 1938).

Viral replication determination by qRT-PCR

The day prior to infection, 100,000 NHBE, A549-ACE2-NLRP1- or A549-ACE2-NLRP1+ cells per well were seeded in 48-well plates. As previously described (Rebendenne et al., 2021), cells were infected or not with SARS-CoV-2 at the indicated MOI and harvested 24 h and 48 h later, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) employing on-column DNase treatment, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 125 ng of total RNAs were used to generate cDNAs. To quantify SARS-CoV-2 RNAs, the cDNAs were analyzed by qPCR using published RdRp primers and probe (Corman et al., 2020), as follow: RdRp_for 5’-GTGARATGGTCATGTGTGGCGG-3’, RdRp_rev 5’-CAAATGTTAAAAACACTATTAGCATA-3’, and RdRp_probe 5’-FAM-CAGGTGGAACCTCATCAGGAGATGC-TAMRA-3’. A standard curve was used in parallel to calculate relative cDNA copy numbers and confirm the assay linearity. qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate, in universal PCR master mix using 900 nM of each primer and 250 nM probe or the indicated Taqmans. After 10 min at 95°C, reactions were cycled through 15 s at 95°C followed by 1 min at 60°C for 40 repeats. Triplicate reactions were run according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a ViiA7 Real Time PCR system (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Cell death

Cell death was measured by quantification of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into the cell supernatant using LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Takara). Briefly, 50 μL cell supernatant were incubated with 50 μL LDH substrate and incubated for 15 min. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of stop solution. Maximal cell death was determined with whole cell lysates from unstimulated cells incubated with 1% Triton X-100.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured by quantification of intracellular ATP using CellTiter-Glo® One Solution Assay (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokins/Alarmins quantification

Human cytokines secretion were quantified by ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, IL-1B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, (88-7261-77), IL-6 (BD, 555220), IL-16 (R&D, DY316), Caspase 3 (Invitrogen, BMS2012INST), Gasdermin E (AG-45B-0024-KI01), Gasdermin D (Abcam, ab272463), Cleaved Caspase-3caspase-3 (Abcam, ab220655). Before use, the samples were diluted 1/3 to 1/5 with their respective assay diluents. IL-18 was quantified using IL-18 Reporter HEK 293 Cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions (InvivoGen). HMGB1 was quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Novus Biologicals).

Caspase activities

Caspase (G8090, G9951, Promega) activity were addressed in cells after 24 hours treatment or infection according to the manufacturer instructions.

Top-down LC-MSMS

Nano-LC-MSMS analyses of Gasdermin-D were performed on a nanoRS UHPLC system (Dionex) coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, a total of 5 μL of sample at ∼1-5 μM was loaded onto a reverse-phase C4-precolumn (300 μm i.d. × 5 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 20 μL/min in 2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.2% formic acid (FA). After 5 minutes of desalting, the precolumn was switched online with an analytical C4 nanocolumn (75 μm i.d. × 15 cm; in-house packed with C4 Reprosil) equilibrated in 95% solvent A (5% ACN, 0.2% FA) and 5% solvent B (0.2% FA in ACN). Proteins were eluted using a binary gradient ranging from 5% to 40% (5 minutes) and then 40% to 99% (33 minutes) of solvent B at a flow rate of 300 nL/min.

The Fusion Tribrid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was operated in positive mode with the Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The spray voltage was set to 1900 V, the ion transfer tube temperature to 350°C, the RF lens to 60%, and no in-source dissociation was applied.

MS scans were acquired in the 1000-2000 m/z range, in the Orbitrap at 7500 resolution with the following parameters: 10 μscans for averaging, AGC target set to 3e5 and maximum injection time to 50 ms. 3 second MSMS cycles were used, with the following parameters: HCD activation was done with 25% activation energy, MSMS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap at 60000 resolution. The AGC target was set to 1e6 and the maximum injection time to 400 ms. Dynamic exclusion for 60 s was used within 30 s to prevent repetitive selection of the same precursor (selection tolerance: ±20ppm) and improve the number of identified proteins. LC-MSMS.raw files were automatically deconvoluted with the rolling window deconvolution software RoWinPro and the proteoform footprints were visualized with VisioProt-MS v2.0. Spectra identification was done in Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) v.2.3, using a three Tier seach including an Absolute Mass Search (precursor mass tolerance - 100 Da, fragment mass tolerance - 10ppm) followed by a Biomarker Search (no enzyme precursor tolerance – 100 ppm, fragment mass tolerance – 50 ppm) and a last Absolute Mass Search (precursor mass tolerance – 1000 Da, fragment mass tolerance – 10 ppm). The identified truncated proteoforms were then manually validated. The search database was generated using a custom made.fasta file containing the sequences of GSDMD and the 3CL protease.

Human recombinant Gasdermin D production and purification