Abstract

Background

The economic crisis in Lebanon, a middle-income eastern Mediterranean country, has been threatening the health of the local population. This review will look at the impact of the economic crisis and COVID-19 on health and healthcare in the country, discussing food insecurity and water shortages, and the hospital crisis for what concerns medications, electricity shortages and workforce issues.

Methodology

Peer Reviewed Literature produced between 2015 and 2021, indexed in Pubmed, Scopus and Google Scholar was used to compile this short report. News and governmental reports, alongside reports of NGOs like Médicins sans frontières were also collected; these were analysed for the production of this short report.

Results

The challenges and public health consequences caused by the economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in Lebanon were identified and commented upon. From food insecurity and water shortages, to the Beirut port explosion and the 2021 lack of fuel and electricity, it was found that the health and well-being of the Lebanese population is currently being threatened from many points of view. With food inflation rates rapidly escalating in 2020 and peaking at 441% in October, new-born and infant milk being non-existent and 20 hour power cuts daily, the situation in Lebanon does not seem to be improving. The country needs to receive international help to relief the population from these synergetic crises.

Conclusion

Long-term economic reforms with an emphasis on employment should be at the forefront of the government's priority list. International help should also be provided to prevent disasters like food insecurity and electricity shortages from posing threats to the lives and the wellbeing of the people in Lebanon again.

Keywords: COVID-19, Economic crisis, Food insecurity, Lebanon, Public health

Introduction

The economic crisis in Lebanon (a Middle-income Eastern Mediterranean country) has been threats to the local population's health. This review will look at the impact of the financial crisis and COVID-19 on health and healthcare in the country, discussing food insecurity and water shortages, the hospital crisis, electricity shortages, and workforce issues.

Methods

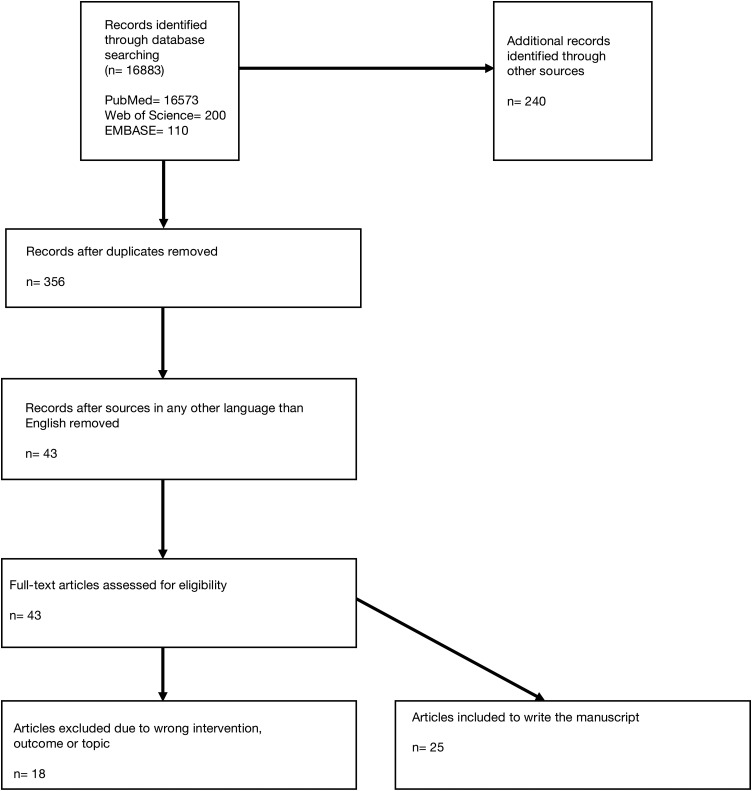

This research study is a scoping review that contains contents extracted through searches from reputable sources and databases from SCOPUS, Google Scholar, Semantic Scholars, Cochrane, EMBASE, Pubmed, Medline, and Newsletters from UNICEF, Reliefweb, and Action Against Hunger. The keywords used during the searches include “Impact”, “COVID-19”, “Economic crisis”, “Public health disintegration”, “Food insecurity”, and “Lebanon.” All the sources extracted were published between 2015 and 2021. A Prisma flow chart has been drawn and is presented as Fig. 1 to summarise the article inclusion and exclusion process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for Accuracy Narrative Review.

The economic crisis

Since late 2019, Lebanon's economic crisis has dramatically expanded. This resulted in the October revolution, which sparked almost immediately after the government announced a WhatsApp fee to cover the economic burden of the crisis mentioned above [1]. During the first week, all national Banks closed their doors due to financial bankruptcy; thus, residents could not access their money to pay for necessities such as housing, food, water, and other bills. Food prices began to increase due to shortages in imports and availability. This has affected the residents and the refugee community in the country, especially the Syrian refugees that have become more vulnerable to this threat [2].

The rapid deterioration Lebanon is experiencing affects not only the Lebanese people but also the refugee population – especially Syrian refugees. Several agencies invested in the cause, such as UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), are worried that the refugee population will not be able to afford the survival minimal expenditure basket [3].

Furthermore, in 2021, the Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon (VASyR) confirmed that nine out of ten Syrian refugees are still extremely poor – ensuring their increased susceptibility to the economic crisis [3].

In 2021, a survey was done among the refugees. It showed that to survive the crisis, people are borrowing money, home-schooling, having delays with payments, and cannot afford primary healthcare and medications due to the poor pay of their jobs. Overall, these negative coping strategies make them more vulnerable to malnutrition and more reliant on charities and donations [3].

During this time, an overall increase in rent and eviction has been seen. A study showed that 60% of Syrian refugees live in overcrowded and dangerous shelters due to the inability to pay for more spacious accommodation [3].

Due to the inflation of food costs, in June 2021, it was found that 49% of Syrian refugees were food insecure. Furthermore, in 2021, 30% of Syrian refugee children currently living in Lebanon (ages 6–17) have never attended school [3]. Child labour has become a common aspect of life, with 20% of girls aged 15–19 being married and 56% of children aged 1–14 have experienced domestic violence [3].

The UN agencies [(UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)] are struggling to provide support to the community, which included both Lebanese and refugees in need [3].

Lebanese banks struggled before 2019 as the Syrian population relied on them during the local civil war. However, as the Lebanese economic crisis worsened, funds became inaccessible to Lebanese and Syrian people [4]; the number of struggling individuals has thus grown and continues to expand to this day.

Lebanon is now facing an economic crisis that rivalled the 1975–1990 civil war [4]. As the dollar currency became non-existent and the Lebanese pound collapsed, the Syrian pound plummeted by 30% in 2019 [4].

Another threat emerged in October 2019 when unprecedented wildfires took hold over the western mountains. These fires raged on for several days and some for weeks due to the unavailability of firefighting aircraft resulting directly from no maintenance of said aircraft. International help was brought in to tide the fires [5].

Riots and protests against the regime have been an on-off phenomenon in Lebanon. However, the protests seen in 2019 have been some of the biggest the country has recently experienced. At that time, the country recorded a 150% debt-to-gross domestic product ratio, 37% youth unemployment rate, and 27% of the population was living under the poverty line [5]. Furthermore, the country also had a 25% overall unemployment rate [5]. These numbers have now increased due to the growth of the economic crisis and the impact of COVID-19.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

On 21 February 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was registered in Lebanon [6]. Despite the imposed lockdown and the strict safety measures, mass protests continued due to the Lebanese populations’ lack of faith and trust in the government and its ability to contain the pandemic. This intensified the already severe financial crisis discussed above, adding to the Lebanese banking system [6].

The rise in cases of COVID-19 extensively interacted with the vulnerability of the people, with hunger, and with the decline of the privatized and expensive healthcare system in Lebanon [6]. COVID-19 has negatively impacted many vulnerable families as they are running out of food, and hunger becomes the order of the day. Anxiety-related food availability has caused modifications in eating habits among people experiencing food insecurity. Findings have shown that in every 16 households, 9 ate less than two meals each day and more than 70% of them skipped their meals to save food [7].

The first wave of COVID-19 in Lebanon (Feb 2020–June 2020) was very mild. The surge experienced in September–October 2020 coincided with the Delta variant spread across the globe. It may be indirectly linked to the Port explosion, given that significant numbers of Lebanese expatriates rushed back to the country in the weeks that followed. The August 2020 Beirut explosion magnified the country's financial crisis as well, enhancing people's vulnerability and economic insecurity.

Despite the riots, COVID-19 infections were somewhat contained until Beirut's port exploded; the explosion sent the entire nation into panic mode in search of missing loved ones, and hospitals all over were overwhelmed with the injured, skyrocketing the COVID infection rate [8].

The impact of the economic crisis on food insecurity

Food insecurity in Lebanon has created another crisis amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a high increase in panic buying, a rise in food price, a reduction in food deliveries, and the availability of essential food items. Families are grappling with the pandemic and, at the same time, with the high constant hunger, which has dramatically affected the most vulnerable, especially the elderly, children, and people with disabilities, as there are little help and support available to them [9].

Food insecurity and hunger increase the risks of COVID-19 contraction in the local population and the refugee population. People are less likely to follow the standard guidelines and public health practices to secure food for their families. The poor sanitation, overcrowded places, and going from house to house further expose many people to enormous health risks [10].

Food inflation rates rapidly escalated in 2020, peaking at 441% in October [11]. Bread that usually costs a nominal fee has become rich man's gain. Fruits and vegetables once sold in kilograms at the same price as juice are now being sold in singles. Milk also took a massive hit in the market. Newborn and infant milk were and still are non-existent. During the pandemic, milk products were not made available to the public, but after the Beirut explosion, these products disappeared from shelves; this poses many health risks for infants and newborns, who are now incredibly hard to feed healthily.

Many families are in a devastating situation as their children, and loved ones are affected by food shortages and hunger, directly affecting their lives; with low resources available to quench the issue and low availability of social support, the situation becomes more and more unsustainable [12].

Apart from consequences on the mental health of the Lebanese population, food insecurity poses many threats to physical health as well; previous literature has indeed associated food insecurity with chronic diseases such as hypertension and types two diabetes [13] as well as decreased immunity posing patients at higher risks of opportunistic infections [14] and COVID-19. Food insecure children have also previously been found to be twice as likely to be in poorer health compared to average, as well as 1.4 times more likely to develop a respiratory disease such as asthma [15], which poses patients at greater risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes, such as hospitalization and intensive care unit admission [16].

Nowadays, as the population grows poorer, people are taking more and more risks in trying new products based on affordability. This does not only apply to the food sector but every item on the supermarket shelf. The struggle between buying a recognizable brand and affordability is quotidian.

Furthermore, the recent crisis affecting fuel and electricity in the country has posed further challenges on the security and provision of food, as well as on healthcare and drinkable water access, as UN officials have declared [17]. Due to 20-hour power cuts daily on average, refrigerators have lost their usefulness. Now, every item stored inside cannot be cooled, and this crisis also happened to coincide with the summer months of 2021 when humidity and high temperatures prevail. Gastroenteritis cases seem to have climbed as reported by ER residents unofficially in various Lebanese hospitals.

Millions have been left without water and hospitals have been forced to reduce their electricity consumption due to the shortages; overall, this has further worsened food insecurity. People are finding other barriers to food acquisition, such as reaching the supermarkets by car. It is even more complicated to store and cook food without electricity upon which household supplies rely. This is the last challenge affecting the people of Lebanon, their health, and food security, and it must be solved immediately to provide some relief and protection to the local population.

In a similar situation, it is fundamental to encourage people to follow public health guidelines; state-sponsored food programs that can momentarily relieve the population from this crisis are also necessary. A study highlighted that promoting healthy, affordable, and culturally acceptable diets through sustainable food-based dietary guidelines could significantly decrease food insecurity in Lebanon [18]. However, there is a need to understand that the burden to solve the multiple crises affecting Lebanon must not only be placed on the Lebanese population. It is not realistic to think that with more affordable and healthier diets, the problem of malnutrition and insecurity will be solved; international help is indeed needed to support these populations, as well as economic support.

The impact of the economic crisis on healthcare

Lebanon is also facing healthcare disintegration. Hospitals have had to ration their supplies or risk shutting down [19]. One of the problems that hospital staff is facing is going to work. Several staff members have resigned due to the inability to reach the hospital without spending their entire salary on fuel. Another reason for causing trouble for healthcare workers is their monthly wage, which has now become a very negligible sum. Thus, for many healthcare workers, staying home is more economically convenient than working.

Fuel shortages have also affected the hospitals. Some hospitals have run out of fuel, and others pleaded to the public for fuel donations in response to imminent closure [20], [21]. These crises have caused a massive increase in Lebanese migrants, as more people than usual are trying to emigrate abroad to find better living conditions [22], [23]. This has also caused staff shortages in all areas of expertise, including the healthcare system.

Another issue is the availability of medications both in hospitals and at pharmacies around the country – both due to shortages and increased prices, as the government recently lifted its subsidies on medication prices [24], [25]. For instance, some hospitals like Makassed General Hospital in Beirut have had to cut non-life-threatening surgical operations due to the unavailability of anaesthetic medications. From Aspirin and Paracetamol to cancer drugs, shortages have been recorded in all areas of medicine. To obtain a prescription, the population has to search through the entire country for a pharmacy with the desired treatment. People that have relatives living outside Lebanon are sending bags full of essential medicines to treat loved ones.

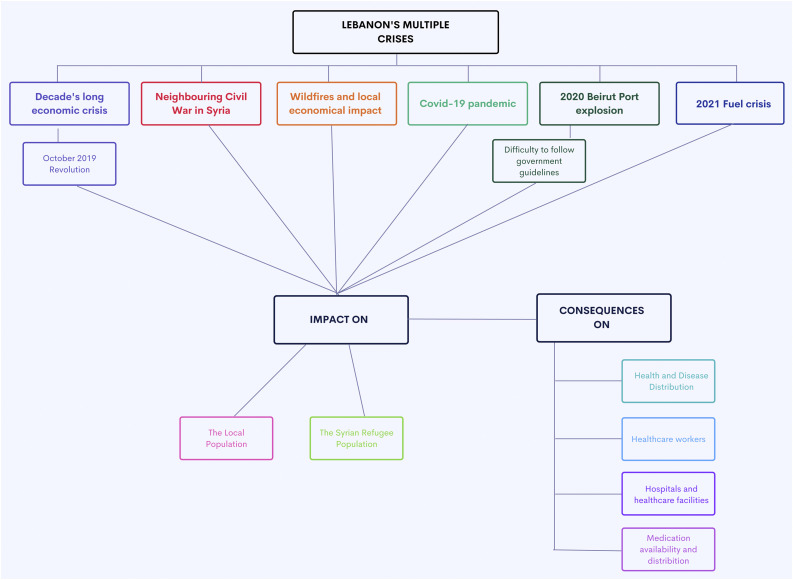

A figure explaining the interaction of the different social and medical issues explained in this review has been presented as Fig. 2 .

Figure 2.

Summary of the interactions of Lebanon's Multiple Crises.

Conclusion

In conclusion, long-term economic reforms with an emphasis on employment should be at the forefront of the government's priority list; this should be done to prevent disasters like food insecurity and electricity shortages from posing threats to the lives and the wellbeing of the people in Lebanon again. Through this report, the authors hope to have shed light on the different issues devastating the Lebanese population and to have proposed tangible recommendations to relieve these issues. The authors call on the international community and international organizations like WHO, Médecins sans frontières, and the United Nations World Food Program to contribute to the relief of the Lebanese population from a nutritional and overall public health emergency.

Informed consent and patient details

The authors declare that the work described does not involve patients or volunteers.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

This work did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

All authors attest that they meet the current International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for Authorship. Individual author contributions are as follows: Anna and Aborode thought of the concept; Anna, Aborode, Matilde and Noha contributed to manuscript writing and initial review; Anna and Aborode contributed to the final review; Anna proceeded with the submission.

References

- 1.BBC News Lebanon scraps the WhatsApp tax as protests rage. BBC News. 2019 [Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50095448. Accessed on August, 18 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Action Against Hunger . 2021. Lebanon and Covid-19 exacerbate impossible living situation of Syrian refugees. [Available on: https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/story/lebanon-covid-19-exacerbates-already-impossible-living-situation-syrian-refugees. Accessed on 5th May, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNHCR . 2021. UN: Syrian refugees in Lebanon struggle to survive amid worst socioeconomic crisis in decades. [Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2021/9/615430234/un-syrian-refugees-lebanon-struggle-survive-amid-worst-socioeconomic-crisis.html. Accessed on 26th September, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuters . 2019. Lebanon crisis wreaks havoc on Syria's war-torn economy. [Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-economy-lebanon-idUSKBN1Y31I7. Accessed on 29th November, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BBC News Lebanon protests: how WhatsApp tax anger revealed a much deeper crisis. BBC News. 2019 [Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50293636. Accessed on June 15, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shallal A., Lahoud C., Zervos M., Matar M. Lebanon is losing its front line. J Glob Health. 2021;11:03052. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.03052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoteit M., Al-Atat Y., Joumaa H., Ghali S.E., Mansour R., Mhanna R., et al. Exploring the impact of crises on food security in Lebanon: results from a national cross-sectional study. Sustainability. 2021;13:8753. doi: 10.3390/su13168753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Project Hope. 2021. Lebanon's health system collapse could threaten millions of lives. [Available at: https://www.projecthope.org/lebanons-health-system-collapse-could-threaten-millions-of-lives/12/2020. Accessed on August 19, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumena W. Impact of Covid-19 curfew on eating habits, eating frequency, and weight according to food security status in Saudi Arabia: a retrospective study. Progr Nutr [Internet] 2021;22(4):e2020075. [cited 2021 Aug. 22. Available from: https://www.mattioli1885journals.com/index.php/progressinnutrition/article/view/9883] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Relief Web . 2021. COVID-19 cases increase 220% in month since Beirut explosion. [Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/covid-19-cases-increase-220-month-beirut-explosion. Accessed on September 2 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Relief Web. 2021. Lebanon: families face running out of food in new COVID-19 lockdown. [Available on: https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-families-face-running-out-food-new-covid-19-lockdown. Accessed on July 5 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNICEF . 2021. Lebanon escalate crisis out children and families at risk. [Available on: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/lebanon-escalating-crisis-puts-children-risk-majority-families-cannot-afford-meet. Accessed on: July 5 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trading Economics . 2021. Lebanon food inflation. [Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/lebanon/food-inflation. Accessed on September 7 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linda N. Pandemic of hunger. Nature. 2021 [ https://www.nature.com/immersive/d41586-020-02848-7/index.html] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira M., Oliveira A.M. Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23:3236–3240. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020003493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aceves-Martins M., Cruickshank M., Fraser C., Brazzelli M. NIHR Journals Library; Southampton (UK): 2018. Child food insecurity in the UK: a rapid review. [PMID: 30475559] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gundersen C., Ziliak J.P. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1830–1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [PMID: 26526240] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang B.Z., Chen Z., Sidell M.A., Eckel S.P., Martinez M.P., Lurmann F., et al. Asthma disease status, COPD, and COVID-19 severity in a large multi-ethnic population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.030. [S2213-2198(21)00834-5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Nations . 2021. Fuel crisis in Lebanon potential catastrophe for thousands: senior UN official. [Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/08/1097962. Accessed on August 21 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health . 2021. Promoting sustainable and healthy diets to mitigate food insecurity amidst economic and health crises in Lebanon. [Available at: nih.gov. Accessed on August 21 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Médecins Sans Frontières . 2021. Healthcare system in Lebanon disintegrates as political vacuum persists. [Available at: https://www.msf.org/healthcare-system-lebanon-crumbles-amidst-political-and-economic-crisis. Accessed on September 7, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 22.THE NATIONAL . 2021. The last call: Lebanon's fuel crisis threatens hospitals with closure. [Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/2021/08/11/this-is-the-last-call-lebanons-fuel-crisis-threatens-hospitals-with-closure/. Accessed on September 6 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The New Humanitarian . 2021. A year after the Beirut blast, subsidy cuts compound Lebanon's desperation. [Available at: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2021/8/4/a-year-after-the-beirut-blast-subsidy-cuts-compound-lebanons-desperation. Accessed on September 5, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 24.France 24 . 2021. Pharmacies go on strike in crisis-hit Lebanon over medicine shortages. [Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20210709-pharmacies-go-on-strike-in-crisis-hit-lebanon-over-medicine-shortages. Accessed on August 29, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 25.BBC News Lebanon faces disastrous medicine shortages. BBC News. 2021 [Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-57714304. Accessed on August 30, 2021] [Google Scholar]