Abstract

Objective

To describe the design and impact of a systematic, enterprise‐wide process for engaging US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) leadership in prioritizing scarce implementation and evaluation resources.

Data Sources

From 2017 to 2021, the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) identified priorities from local, regional, and national leaders through qualitative discussions and a national survey and tracked impacts via reports generated from competitively funded initiatives addressing these priorities.

Study Design

Guided by the Learning Health System framework and QUERI Implementation Roadmap, QUERI engaged stakeholders to nominate and rank‐order priorities, peer‐reviewed and funded initiatives to scale up and spread evidence‐based practices (EBPs) using theory‐based implementation strategies, and evaluated the impact of these initiatives using the QUERI Impact Framework.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

QUERI collected priority nominations through qualitative discussions and a web‐based survey, and live voting was used to rank‐order priorities. QUERI‐funded teams regularly submitted progress reports describing the key activities, findings, and impacts of the quality improvement (QI) initiatives using a standardized form created in the VA Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).

Principal Findings

QUERI launched five QI initiatives to address priorities selected by VA leadership. In partnership with 28 health system leaders, these initiatives are implementing 10 EBPs across 53 sites, supporting 1055 VA employees in delivering evidence‐based care. The success of these initiatives led to an expansion of QUERI's process to address 2021 VA leadership priorities: virtual care, health disparities, delayed or suppressed care due to COVID‐19, employee burnout, long‐term and home care options, and quality and cost of community care.

Conclusions

QUERI, a unique program embedded in a national integrated health system, deployed a novel approach to inform policy making and enhance the real‐world impact of research through prioritization of limited resources, rigorous peer‐review, and assessment of impacts on the health system, employees, and Veterans.

Keywords: evidence‐based policy, evidence‐based practice, implementation science, knowledge translation, Learning Health System, quality improvement, veterans

What is known on this topic

Research evidence needs to be used more effectively to solve health care challenges and benefit end‐users.

Little guidance exists on how to prioritize scientific investments that address health care challenges and inform policy in resource‐constrained federal agencies.

What this study adds

A novel, enterprise‐wide approach to match scientific investments with emerging health system needs and national policy (e.g., Evidence Act) goals.

Prioritization of scientific investments, informed by the Learning Health System framework and based on a multilevel stakeholder approach and rigorous peer review and implementation processes, to ensure that Veterans benefit from research discoveries.

1. INTRODUCTION

Implementation, evaluation, and quality improvement (QI) initiatives rooted in scientific evidence and methods are crucial for addressing complex health care challenges and enhancing quality, efficiency, equity, experience, and outcomes of care. Yet, there is a 17‐year lag in the adoption of research discoveries into clinical practice. 1 Although some time is needed to ensure the effectiveness and safety of a new innovation, this research‐to‐practice gap wastes scarce resources by preventing effective programs and practices from quickly reaching those who could benefit the most. 2 At the same time, sometimes programs or policies are rapidly deployed with little research evidence to support them.

A variety of theory‐based implementation and QI strategies have been developed to support the implementation of research‐informed innovations, interventions, programs, and practices (hereafter collectively referred to as evidence‐based practices [EBPs]). Implementation/QI strategies can be used to help narrow the research‐to‐practice gap, reduce waste, and enhance population health by re‐directing investments to support and optimize the implementation of EBPs. 3 Implementation/QI strategies promote the uptake of EBPs at the provider level (e.g., training, consultation), organization level (e.g., infrastructure, resources, ongoing leadership support), and policy level (e.g., regulation, reimbursement options). 4 Multifaceted strategies are essential to sustain EBPs and ensure individuals and communities continue to benefit from research discoveries after external support ends.

The Foundations for Evidence‐based Policy making Act of 2018 (Evidence Act; US Public Law (PL) 115‐435) has enormous potential to further strengthen these efforts to reduce the research‐to‐practice gap and enhance the impact of research investments. Specifically, as an update to the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Modernization of 2010 (US PL 111‐352) and the Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996 (US PL 104‐106), the Evidence Act aligns leadership support, resources, and multistakeholder input (e.g., researchers, organizational leaders, policy makers, members of the public) to promote a learning organization culture that utilizes evidence and evaluation to inform uptake of effective programs and policies. Signed into law in January 2019, the Evidence Act requires cabinet‐level agencies, including the US Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Health and Human Services, to justify program budgets using evidence and evaluation. 5 In particular, Title I of the Evidence Act requires VA to produce a quadrennial learning agenda that describes how the agency develops and uses evidence to inform programs and policies, how that evidence is generated and strengthened through annual evaluation plans that include implementation evaluations of EBPs, and how the agency is regularly assessing its capacity for evidence‐building activities. 5 These deliverables are made public and are expected to inform program decisions throughout the agency (e.g., determining the programs to be continued based on evidence of ongoing effectiveness).

The Evidence Act lays the foundation for federal agencies to make evidence‐informed decisions in light of competing priorities and increasing demands for scarce resources. As both a federal agency and a large, integrated health system with an embedded research program, VA is uniquely poised to leverage a Learning Health System approach—which integrates health system performance data and evidence to enhance health care delivery and provide safer, more efficient care to consumers—to optimize programs and policies in alignment with Evidence Act goals and ultimately improve population health. 6

In support of VA's transformation to a Learning Health System, the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), a national knowledge translation program located in the VA Office of Research and Development, created an enterprise‐wide, systematic process for prioritizing, resourcing, and monitoring implementation, evaluation, and QI initiatives to address time‐sensitive health care challenges and inform VA's implementation of the Evidence Act. The process is guided by the QUERI Implementation Roadmap, which is based on previously established implementation, QI, and Learning Health System frameworks. The Roadmap outlines core strategic methods that can be used to identify health care priorities, implement EBPs that address these priorities, and evaluate EBPs and implementation/QI strategies to ultimately inform the sustainment of the EBPs. 7 QUERI's process for prioritizing scientific investments aligns top‐down VA leadership priorities with the needs for population health improvement at the clinic level (bottom‐up) to ensure meaningful and timely care improvements for Veterans and their families. Like other priority setting approaches, QUERI's process considers criteria that the National Academy of Medicine has outlined to be the Quintuple Aim, focused on the effective use of resources and taking into account health benefit, consumer and provider experiences, population needs and impact, equity, and cost‐effectiveness. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

This paper describes the QUERI process for engaging health system leaders in prioritizing, resourcing, and monitoring impacts of scientific investments with the goal of informing a rigorous response to the Evidence Act and investing in system‐wide, sustainable care improvements. Incorporating QUERI's decades of experience with implementation science, stakeholder engagement, integration of scientific expertise within health systems, and scientific peer review, this novel process aligns agency priorities with implementation, evaluation, and QI investments to fulfill national health system performance goals.

2. METHODS

The following methods describe how QUERI evolved its approach to QI to address policy making goals through an iterative process of implementation, evaluation, and sustainment of QI investments at the national and regional levels. Methods and data ascertainment for analyses were considered nonresearch and did not require institutional review board approval per the updated Common Rule and the VA Office of Research & Development Program Guide: 1200.21 VHA Operations Activities That May Constitute Research.

2.1. QUERI's strategic methodology and evolving alignment of QI with evidence‐based policy

In 1998, VA established QUERI as a national program to accelerate the adoption of research evidence into clinical practice with the mission of improving Veteran health and well‐being. Over the years, QUERI has grown to support a national network of more than 200 health services, implementation, evaluation, and QI experts across the US and has funded over 500 scientifically peer‐reviewed initiatives focused on applying robust methods to enhance the quality and delivery of care provided to Veterans.

Initially, QUERI‐funded activities focused on partnering locally with providers and facility leadership to develop and disseminate strategies and practices that improve Veteran outcomes for high priority conditions (e.g., cancer, diabetes, spinal cord injury). 17 These strategies typically focused on improving provider uptake of EBPs and were less tied to national policies. In 2015, VA leadership asked QUERI to evaluate the impact of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (VACAA, or “Choice Act” US PL 113‐146) on cross‐cutting outcomes, including quality and Veteran access to care. 18 The Choice Act expanded options for Veterans to receive care from community non‐VA providers in certain situations. 19 QUERI funded several national peer‐reviewed evaluations to examine Choice Act implementation, and these evaluations identified challenges that affected policy uptake, specified strategies that may improve implementation, and highlighted the importance of evaluating policy impacts at the clinic level. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 In 2016, QUERI's goals were updated to include policy as a mission‐critical priority, in part based on the Choice Act evaluation experience, the US Office of Management and Budget's (OMB's) directive requesting a more rigorous evaluation to inform programs and policies in the VA, and the passage of the Evidence‐Based Policy making Commission Act of 2016 (US PL 114‐140), a progenitor to the Evidence Act establishing the Commission on Evidence‐based Policy making. 26

Seeking to align with changes in VA priorities after the passage of the Choice Act and similar legislative mandates, QUERI transformed its disease‐specific centers and funding mechanisms to address cross‐cutting VA priorities—particularly decreasing unwanted clinical variation and enhancing Veteran access to care—and promote bi‐directional national partnerships. QUERI launched 15 Programs—interdisciplinary, field‐based centers committed to partnering with VA health system leaders to develop multilevel implementation and QI strategies and tools to support the uptake of EBPs that address major health care challenges. 18 QUERI also expanded evaluation support, funding evaluations of time‐sensitive VA programs and policies, and a national center devoted to policy evaluation, the Partnered Evidence‐based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC).

2.2. QUERI‐VISN Partnered Implementation Initiative priority nomination process to inform QI investments

To support the implementation of VA priorities across different geographic regions, QUERI established the QUERI‐VISN Partnered Implementation Initiatives (PIIs) in 2017–2018. The purpose of the PIIs was to partner with leaders of Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) to improve the quality of care at the regional level. The PII process included the identification of top health care priorities based on multilevel stakeholder input. Using a web‐based survey, QUERI collected priority nominations from national (e.g., VA Program Office Directors), regional (e.g., Chief Medical Officers), and local (e.g., Medical Center Directors) health system leaders across the US. During a live voting session, VISN Directors selected their three highest priorities from a list of the 10–15 top nominations.

The selected priorities were incorporated into the PII Request for Applications (RFA), which called for proposals from implementation teams co‐led by a VA investigator and VISN leader (e.g., Chief Medical Officer). In the first phase of the RFA, teams applied for start‐up (1‐year) funding to implement an EBP in at least one VA facility and measure changes in quality of care and other health system performance metrics. As part of the application, teams worked with diverse stakeholders to select a priority from the RFA, identify an EBP to address the priority, describe metrics for benchmarking success, and specify an implementation/QI strategy to support the uptake of the EBP. Applications were scientifically peer‐reviewed, and the highest quality applications were selected for funding. In the second phase, PII start‐ups that successfully demonstrated improvements in quality of care were invited to apply for multiyear funding to implement and evaluate the EBP across multiple VISNs. QUERI teams submitted progress reports twice a year describing key activities and cumulative PII impacts, and these impacts were conveyed to national, regional, and local leadership to ensure QUERI efforts aligned with health system priorities, standards, and metrics.

2.3. Alignment of QUERI QI and evaluation experiences to fulfill Evidence Act goals

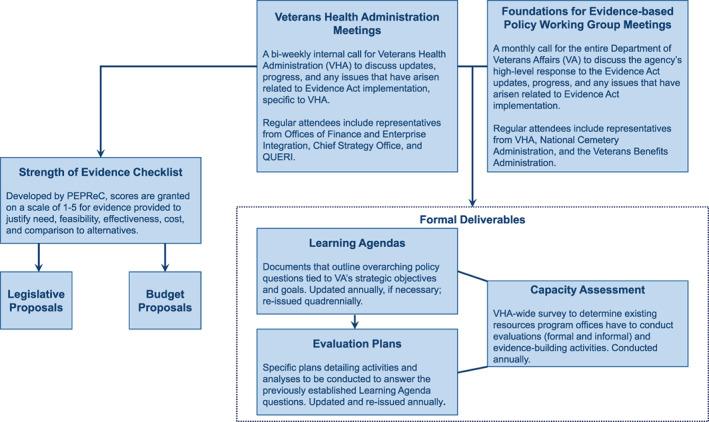

The passage of the Evidence Act elucidated the need for an enterprise‐wide process to prioritize evaluation investments in order to fulfill the core requirements of this legislation. In 2019, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Office of the Undersecretary for Health delegated the completion of core requirements of the Evidence Act to QUERI. To accomplish this, QUERI leveraged the existing PII priority nomination process to inform Evidence Act implementation in VA. QUERI's policy resource center, PEPReC, worked with partners across VA to create required documents for the Evidence Act, including quadrennial learning agendas based on VA and VHA strategic priorities, annual evaluation plans to inform policies related to key priorities, and annual evaluation capacity assessments to determine breadth and depth of evaluation activities throughout VA. 27 Figure 1 illustrates VHA's overall implementation of the Evidence Act, which included regular meetings with key stakeholders to discuss VHA's response and progress on Evidence Act tasks and deliverables. The learning agendas were directly linked to agency strategic goals and objectives and provided a summary of relevant evaluations, which were further detailed in the annual evaluation plans. Annual evaluation plans described the importance of the evaluation and its planned analyses and activities. Evaluation plans underwent standardized peer review processes managed by QUERI to ensure that high‐quality evaluation standards were met and that there was the independence of evaluation methods from a sponsoring VA Program Office or other entity.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of VHA's implementation of the Evidence Act [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Agency priorities for the VHA Evidence Act fiscal year (FY) 2022 learning agenda and evaluation plans were identified based on feedback from VA senior leadership. Policy priorities included those that QUERI had previously elicited as part of the PII process (e.g., suicide prevention, opioid use disorder [OUD] and pain treatment). COVID‐19 long‐term effects were added to the FY2023 learning agenda based on feedback from VHA leadership. Once the priorities were established, QUERI's PEPReC assessed VHA's current evaluation efforts in these areas—as research and evaluation have been a core part of VHA's mission for decades—and linked existing work to the learning agendas and evaluation plans. Working closely with researchers and health system leadership, PEPReC drafted the learning agendas and evaluation plans based on OMB's requirements. After several iterations, VHA submitted final drafts to OMB. The VA FY2022 Annual Evaluation Plan is publicly available, and the final version of the learning agenda is forthcoming. 28

The annual capacity assessment examined the VA Program Office's ability to conduct evaluation activities. Questions varied from year to year; the premiere survey established a baseline, while the more recent iterations included questions about the formality or informality of evaluation processes and the impact of current events (e.g., COVID‐19) on evaluation capacity and activities. VA senior leadership intends to use the findings to guide future evaluation work related to specific priorities and expand overall evaluation capacity.

In addition to supporting these mandated Evidence Act deliverables, PEPReC assessed the quality of evidence of new programs and policies submitted as VHA legislative and budget proposals using a novel strength of evidence checklist. PEPReC developed the checklist based on several existing, validated strength of evidence methodologies. Once in use, PEPReC continued to refine it and its associated guidance documentation based on lessons learned. PEPReC briefed several VA Program Offices on the checklist and its methodology so they can adopt the approach, or a variation of it, for their legislative, budget, and other proposal processes.

2.4. Expansion of QUERI evaluation capacity to sustain alignment of Evidence Act priorities with VA QI goals

During 2018–2020, QUERI conducted a strategic analysis and program evaluation to identify new opportunities to support VHA and Veteran needs and refine existing QUERI processes, such as the PII process. Using mixed methods analyses, QUERI staff gathered feedback from more than 150 stakeholders across VA. Results of the strategic planning process highlighted successes of the PII process and elucidated opportunities for QUERI to expand its support for aligning Evidence Act and VHA QI goals.

In response to stakeholder feedback, QUERI expanded its Programs, adding Rapid Response Teams to enhance VA's capacity to respond quickly to national and regional developments and Evidence Act evaluation needs. To build VA's long‐term evaluation capacity, QUERI established Mentoring Cores within the Programs to help grow a pipeline of implementation, evaluation, and QI expertise. 29 Recently, QUERI also created the Advancing Diversity in Implementation Leadership program to support the development of future leaders in implementation, QI, and evaluation science.

In 2020–2021, based on VA leadership input, the PII process transitioned to a more formal, systematic process to support VHA's fulfillment of Evidence Act requirements and inform enterprise‐wide QUERI investments in implementation and evaluation initiatives. As illustrated in Figure 2, this process is based on the Learning Health System framework and involves engaging local, regional, and national health system leaders and multiple enterprise‐wide VA governance and strategic committees throughout the process. During the 2020 QUERI Annual Strategy meeting, which brought together a geographically and clinically diverse group of VA Program Office, VISN, and facility leaders, VA investigators, and external stakeholders (e.g., federal agency research representatives) to provide input on QUERI's overall strategic direction, VA leaders discussed the issues that “keep them awake at night.” Common priority themes from these discussions were captured and included as multiple‐choice options in the annual web‐based priority nomination survey, with additional space for write‐in nominations. From November 2020 to January 2021, health system leaders across VA were invited to participate in the survey. QUERI presented the results of the survey to the VA Governance Board and Strategic Directions Committee—enterprise‐wide committees comprised of senior leadership—and they selected their highest priorities from a list of the top 10 priority nominations and added any additional priorities not already captured.

FIGURE 2.

QUERI's process for prioritizing implementation, evaluation, and quality improvement investments [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The top‐ranking health care priorities were presented to VISN Directors for additional feedback and vetting. Selected priorities were added to all QUERI Requests for Applications (RFAs) and mechanisms, including the QUERI Program Rapid Response Team and Advancing Diversity in Implementation Leadership opportunities, to foster immediate capacity‐building in QI and evidence‐based policy. Interdisciplinary teams, co‐led by a health system leader and investigator, submitted applications to address the updated priorities. Using the VA Office of Research and Development scientific peer review process, applications were reviewed, and QUERI funded the highest quality proposals that addressed Evidence Act and VHA QI priorities. Over the course of the FY, QUERI provided regular updates to VA leadership, describing the overall direction and impacts of these QUERI‐funded initiatives.

2.5. Assessment of QUERI impacts

QUERI assessed the impacts of funded initiatives using data from progress reports, which are structured around the QUERI Impact Framework and submitted by QUERI‐funded teams biannually. The QUERI Impact Framework emphasizes impacts on Veterans, employees, and the health system, and QUERI collected information on the progress, findings, and impacts of funded initiatives using a standardized form. 30 Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the VHA. 31 , 32 REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. 31 , 32

QUERI national program office staff used descriptive statistics to summarize QUERI‐funded initiative impacts based on FY2021 report data, which captured cumulative qualitative and quantitative impacts from the start of the initiative through September 30, 2021.

3. RESULTS

Since 2017, QUERI has completed four cycles of the annual priority nomination process. Table 1 lists the priorities selected by VA leadership each year. In the second year of the priority nomination process, VA leaders provided feedback about the care coordination priority, splitting it into two priorities based on whether coordination was internal to VA or involved community providers.

TABLE 1.

Priorities selected by VA leadership

| Fiscal year |

|

| 2018 priorities | |

| Selected by VISN Directors | |

| Fiscal year |

|

| 2019 priorities | |

| Selected by VISN Directors | |

| Fiscal year |

|

| 2020 priorities | |

| Selected by VISN Directors | |

| Fiscal year |

|

| 2021 priorities | |

| Selected and vetted by multiple VA governance and strategic groups |

The care coordination priority was broad and split into two priorities the subsequent cycle: (A) promote effective use and management of community care services external to VA; (B) enhance care coordination within VA.

QUERI is currently funding five PIIs—three second‐phase (i.e., multi‐VISN, large‐scale) and two first‐phase initiatives—to promote the uptake of EBPs that address the priorities of pain and OUD, suicide prevention, care coordination and health disparities, primary care efficiency, and delayed or suppressed care due to COVID‐19. Table 2 summarizes the activities and impacts of the five PIIs. These initiatives have partnered with 28 health system leaders to implement 10 EBPs across 53 sites, reaching 1055 VA employees.

TABLE 2.

Summary of QUERI‐VISN Partnered Implementation Initiative (PII) impacts

| Domain and degrees of impact | Key QUERI PII reported impacts |

|---|---|

| Alignment with multilevel priorities: how is the initiative directly linked to health system operations and research priorities? | 10 Evidence‐based practices (EBPs)

|

| Commitment: how effective is the research‐operations partnership? |

Operations partner resources

Implementation strategies and products

|

| Tailoring to local context: to what extent were specific strategies and tools adopted into routine practice? | Implementation impacts

|

| Informing the field: how are the project results being communicated to key stakeholders and organizations? | Dissemination efforts

|

| Observing health care changes and generating new questions/projects: What improvements in quality of care and health outcomes, policy, and/or culture were observed? Were new analyses/projects launched as a result of the effort? | Sustainability, quality of care and health outcomes, policy, culture

|

For the pain and OUD priority, six first‐phase PII proposals—five focused on expanding Veteran access to medications for OUD (MOUD) and one supporting the implementation of virtual interdisciplinary pain care teams (TelePain)—were selected for funding after peer review. In the second phase, the five QUERI‐funded teams with the shared goal of implementing EBPs for MOUD across various settings came together to form the Consortium to Disseminate and Understand Implementation of Opioid Use Disorder Treatment (CONDUIT) and coordinate resources, methods, metrics, and learnings through their Veteran Engagement, Implementation, and Quantitative/Economic Cores. Due to the rapid onset of COVID‐19 and the major shift to virtual care delivery, the sixth first‐phase PII team focused on implementing TelePain, which utilizes telehealth to deliver interdisciplinary pain care to low‐resource settings, grew into a separate partnered evaluation with a co‐sponsoring National Program Office to support the uptake of TelePain across VA.

To address the suicide prevention priority, PII teams are partnering with 10 Program Offices and VISNs to deploy and evaluate Caring Contacts, a simple, low‐cost EBP that involves sending out brief messages (e.g., cards) of caring concern and support to Veterans at risk of suicide, in emergency departments and urgent care settings. 33

In support of priorities related to care coordination and health disparities, PII teams are partnering with seven VISNs to implement a Critical Time Intervention to support homeless‐experienced Veterans in the transition from VA Grant and Per Diem residential programs to living independently.

Most recently, two new first‐phase PII teams were funded to enhance primary care efficiency and expand endoscopy access to address delayed/suppressed care due to COVID‐19 by supporting pharmacist‐led medication management for Heart Failure in Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs) and replacing colonoscopy with stool‐based fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) for average‐risk colorectal cancer screening, respectively.

The PIIs are utilizing a variety of multifaceted implementation/QI strategies to support providers and medical facilities in delivering high‐quality care across different settings. Two large‐scale PIIs are engaging frontline staff in learning collaboratives to promote the adoption of these EBPs, and all three large‐scale PIIs are gathering feedback from Veterans.

Table 3 summarizes how the 2021–2025 QUERI Programs, Evidence Act learning agenda goals, and annual evaluation plans are connected to agency goals and objectives. Learning agenda goals and evaluation plans were based on the VA FY2022‐2028 Strategic Plan and input from VA leadership and were in part derived from foundational work that was supported through the PIIs. The 2021–2025 QUERI Programs address a broad range of VA priorities, including quality and safety, access to care, mental health, and health equity. The Programs have expertise in more than 25 implementation and QI strategies and are partnering with over 45 national and regional health system leaders to scale up and spread 38 EBPs across VA. The Programs are tailoring EBPs to meet the needs of high‐priority populations, including homeless Veterans, Veterans residing in rural areas, women Veterans, older Veterans, Veterans at risk of developing a disability, Veterans with complex conditions, Veterans with substance use disorders, Veterans affected by social determinants of health, and dual‐use Veterans who receive care in both VA and community settings. Currently, QUERI Programs are supporting a range of evaluation topics to fulfill both clinical priorities and Evidence Act goals. For example, three Program Rapid Response Teams are informing VA's rollout of the COVID‐19 vaccine by examining VA employee and Veteran perspectives of COVID‐19 vaccines, Veteran reasons for COVID‐19 vaccination or hesitancy, patient‐provider discussions about the COVID‐19 vaccine, and Veterans' trusted sources of information about COVID‐19 vaccines.

TABLE 3.

QUERI alignment with FY2022 Evidence Act learning agenda priorities

|

Agency strategic goal 1: Veterans choose Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for easy access, greater choice, and clear information to make informed decisions Agency objective 1.1: US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) understands Veterans' needs throughout their lives to enhance their choices and improve customer experiences |

2021–2025 QUERI programs aligned with agency strategic goals

|

||

|

Evidence Act FY22 learning agenda business question How can VA ensure that Veterans have access to timely care in their preferred setting? |

FY22 annual evaluation plan question How effective are the underserved scores and subsequent mitigation strategies in addressing underserved facilities? How do medical scribes affect clinic function and patient satisfaction? |

QUERI initiative addressing the evaluation question Partnered Evidence‐Based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) |

|

|

Agency strategic goal 2: Veterans receive highly reliable and integrated care and support and excellent customer service that emphasizes their well‐being and independence throughout their life journey Agency objective 2.2: VA ensures at‐risk and underserved Veterans receive what they need to end Veteran suicide, homelessness, and poverty |

2021–2025 QUERI programs aligned with agency strategic goals

|

||

|

Evidence Act FY22 learning agenda business question What strategies work best to prevent suicide among Veterans? How can VHA provide clinically appropriate treatment for opioid use disorders for Veterans? |

FY22 annual evaluation plan question Are Caring Letters an effective and sustainable intervention to reduce suicide behaviors among Veterans? Does the VA Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train‐the‐Trainer (SCOUTT) program improve access to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment and prevent intentional overdose deaths? How did the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) improve opioid safety? How can the information obtained be used by leadership to refine opioid prescription related policy and practice? |

QUERI initiative addressing the evaluation question Implementing Caring Contacts for Suicide Prevention in Nonmental Health Settings Randomized Evaluation of a Caring Letters Suicide Prevention Campaign Consortium to Disseminate and Understand Implementation of Opioid Use Disorder Treatment (CONDUIT) Facilitation of the Stepped Care Model and Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Evaluating the Implementation of the VA SCOUTT Program Partnered Evidence‐Based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) |

|

4. DISCUSSION

Increasing the real‐world impact of research to ensure individuals and communities benefit from research discoveries requires the alignment of evidence and scientific methods to meet the needs of consumers, health systems, and policy makers. As a national program committed to leveraging evidence and scientific methods to improve the care provided to Veterans, QUERI is deploying a Learning Health System approach to prioritize implementation, evaluation, and QI investments and sustain local, regional, and national leadership support for these initiatives by leveraging legislative mandates, notably the Evidence Act. Rooted in implementation and QI science, QUERI's priority nomination process emphasizes a participatory approach and involves systematically collecting multilevel priorities, funding scientifically peer‐reviewed initiatives to address priorities for short‐term (e.g., Rapid Response Team requests), medium‐term (e.g., PIIs, Advancing Diversity in Implementation Leadership program, Evidence Act evaluation plans), and long‐term (e.g., QUERI Programs, Evidence Act learning agendas) initiatives, and conveying impacts to stakeholders across VA.

QUERI's process has a number of strengths that support Evidence Act goals and health system priorities and needs. First, QUERI gathers input on priorities from diverse stakeholders across multiple levels of VA. In contrast to other priority‐setting approaches that use modeling or weighting techniques, QUERI's approach leverages multistakeholder engagement without weighing criteria or feedback from different groups but by balancing top‐down and bottom‐up perspectives to ensure that national policies are relevant to local clinical needs. 15 , 37 Second, QUERI initiatives are led by field‐based scientists who gather input from end‐users (e.g., consumers, providers), managers, and leaders and utilize rigorous implementation, evaluation, and QI strategies and tools (e.g., QUERI Implementation Roadmap) to ensure EBP relevancy, effectiveness, and optimal impact. Third, QUERI utilizes a competitive scientific merit review process that mirrors the National Institutes of Health's process to ensure that selected evaluations are independent, rigorous, and led by skilled teams. Applicants submit proposals describing their implementation/evaluation plans and receive scores and feedback from an expert panel comprising VA providers, health services research investigators, and implementation scientists. The strongest applications addressing these priorities are funded by QUERI, and investigators receive VA research resources and administrative support to carry out the implementation/evaluation initiatives. Fourth, QUERI's process emphasizes transparency and dissemination of results to internal and external stakeholders by benchmarking VHA performance metrics and encouraging scientific publication of results. QUERI follows standardized VA governance processes to communicate evaluation results to inform policy recommendations, and Evidence Act evaluation plans and other deliverables are made public. QUERI‐funded investigators are encouraged to publish evaluation results in peer‐reviewed scholarly journals, and the number of publications is a metric captured as part of the QUERI Impact Framework. 30

Furthermore, QUERI's process is flexible to support short‐, medium‐, and long‐term priorities and how these may change over time. For example, recent events have brought to the forefront the persistent health disparities among vulnerable and marginalized patient populations. Reducing disparities was a top priority selected by VA leadership in 2021, and QUERI is addressing this priority through multiple mechanisms, including the Rapid Response Teams and PIIs. In addition to being a short‐ and medium‐term priority, health equity has become a core component of QUERI's overall strategy and Impact Framework, which includes assessing provider and Veteran experiences when considering equity. Furthermore, QUERI's 2021–2025 Strategic Plan highlights QUERI's commitment to empowering all VA employees to make care improvements by expanding implementation and QI training opportunities and increasing the diversity of implementation leaders through the QUERI Advancing Diversity in Implementation Leadership program. 29

Nonetheless, there are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. Although QUERI deployed a multifaceted, systematic process—which includes a series of qualitative discussions and an online survey—to ensure geographic and clinical representation across VISNs and Program Offices, health system leaders familiar with QUERI may have been more likely to respond to the survey. To maintain anonymity, the survey provided broad category options when asking respondents for their location (by VISN) or office (by organizational unit), thus we are unable to assess the representativeness of responses by facility or Program Office. With organizational changes and leadership turnover, the specific individuals and the total number of individuals surveyed may change from year to year. Identification and contact information for health system leaders were derived from multiple sources, including VA email distribution lists and websites, and changing leadership roles may limit the completeness of the survey group.

Health care organizations and federal agencies have competing priorities and increasing demands for limited implementation, evaluation, and QI investments. Generally, less than $1 out of every $100 of government spending is supported by evidence, making investments in rigorous evaluations paramount for agencies to successfully fulfill Evidence Act requirements. 38 The Evidence Act promotes the optimal use of resources by enhancing evaluation capacity across government and engaging diverse stakeholders—including policy makers, researchers, and members of the public—in using evidence to inform legislative proposals, budgets, programs, and policies. A sustainable process for capturing priorities and feedback from various stakeholders across a health care organization is crucial for designing and executing effective strategies and tools that address the most salient priorities for consumers, health care workers, and medical facilities. QUERI's novel, enterprise‐wide process aligns best practices in QI and evidence‐based policy making, notably by strategically engaging diverse stakeholders (e.g., leadership, end users) and applying strong scientific methods to evaluation and QI efforts. QUERI's process recognizes that priority setting is a continuous, evolving process, and QUERI follows a cyclical approach and refreshes priorities each year. Other health systems, research organizations, or federal agencies may find this flexible, participatory approach helpful in promoting the use of evidence and implementation, evaluation, and QI methods to solve complex challenges, inform programs and policies, and/or justify program budgets.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Service. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Braganza MZ, Pearson E, Avila CJ, Zlowe D, Øvretveit J, Kilbourne AM. Aligning quality improvement efforts and policy goals in a national integrated health system. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(Suppl. 1):9‐19. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13944

Funding information Health Services Research and Development

REFERENCES

- 1. Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearb Med Inform. 2000;1:65‐70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . World Report on Knowledge for Better Health: Strengthening Health Systems. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43058

- 3. Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non‐specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.H.R.4174 ‐ 115th Congress (2017‐2018): Foundations for Evidence‐Based Policymaking Act of 2018. January 14, 2019. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4174

- 6. Institute of Medicine; Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America . In: Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, Michael McGinnis J, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. National Academies Press (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Miake‐Lye I, Braganza MZ, Bowersox NW. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative implementation roadmap: toward sustainability of evidence‐based practices in a Learning Health System. Med Care. 2019;57 Suppl 10 Suppl 3(10 Suppl 3):S286‐S293. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matheny M, Thadaney Israni S, Ahmed M, Whicher D. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, The Hype, The Promise, The Peril. NAM Special Publication. 2019. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/AI-in-Health-Care-PREPUB-FINAL.pdf

- 9. Ottersen T, Førde R, Kakad M, et al. A new proposal for priority setting in Norway: open and fair. Health Policy. 2016;120(3):246‐251. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitton C, Donaldson C. Health care priority setting: principles, practice and challenges. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2004;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-2-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birch S, Chambers S. To each according to need: a community‐based approach to allocating health care resources. CMAJ. 1993;149(5):607‐612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dixon J, Welch HG. Priority setting: lessons from Oregon. Lancet. 1991;337(8746):891‐894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cromwell I, Peacock SJ, Mitton C. 'Real‐world' health care priority setting using explicit decision criteria: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:164. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0814-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Health Information Technology, Evaluation, and Quality Center . Prioritization Matrix. February 24, 2017. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://hiteqcenter.apps.plantanapp.com/Resources/HITEQ‐Resources/prioritization‐matrix

- 15. Minnesota Department of Health . Prioritization Matrix. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/resources/phqitoolbox/prioritizationmatrix.html

- 16. Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative . Quality Improvement (QI) Prioritization Matrix Template Overview. Accessed June 16, 2021. https://malnutritionquality.org/wp-content/uploads/MQii-Project-Prioritization-Matrix.docx

- 17. Feussner JR, Kizer KW, Demakis JG. The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): from evidence to action. Med Care. 2000;38(6 Suppl 1):I1‐I6. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006001-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kilbourne AM, Elwy AR, Sales AE, Atkins D. Accelerating research impact in a Learning Health Care System: VA's Quality Enhancement Research Initiative in the Choice Act Era [published correction appears in Med Care. 2019 Nov;57(11):920]. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1(7 Suppl 1):S4‐S12. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.H.R.3230 ‐ 113th Congress (2013‐2014): Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. August 7, 2014. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/3230

- 20. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7(Suppl 1):S71‐S75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Finley EP, Noël PH, Mader M, et al. Community clinicians and the Veterans Choice Program for PTSD care: understanding provider interest during early implementation. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7(Suppl 1):S61‐S70. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gellad WF, Cunningham FE, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy use in the first year of the Veterans Choice Program: a mixed‐methods evaluation. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7(Suppl 1):S26‐S32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vanneman ME, Harris AHS, Asch SM, Scott WJ, Murrell SS, Wagner TH. Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans' use of Veterans Health Administration and purchased care before and after veterans choice program implementation. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7(Suppl 1):S37‐S44. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, Sulc CA, Au DH, Michael Ho P. Accessing care through the Veterans Choice Program: the Veteran experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1714‐1720. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quinn M, Robinson C, Forman J, Krein SL, Rosland AM. Survey instruments to assess patient experiences with access and coordination across health care settings: available and needed measures. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1(Suppl 7 1):S84‐S91. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.H.R.1831 ‐ 114th Congress (2015‐2016): Evidence‐Based Policymaking Commission Act of 2016. March 30, 2016. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1831

- 27. Ndugga N, Avila C, Pearson E, Pizer S, Garrido M. Partnered Evidence‐based Policy Resource Center Brief: Foundations for Evidence‐based Policy Making Act. September 2020. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://www.peprec.research.va.gov/PEPRECRESEARCH/docs/Policy_Brief_9_EBP.pdf

- 28.Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2022 Annual Evaluation Plan 2021. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/va2022-annual-evaluation-plan.pdf

- 29. Kilbourne AM, Braganza MZ. United States Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration Office of Research and Development Health Services Research and Development. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) 2021‐2025 Strategic Plan 2020. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.queri.research.va.gov/about/strategic_plans/default.cfm

- 30. Braganza MZ, Kilbourne AM. The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Impact Framework: measuring the real‐world impact of implementation science. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):396‐403. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06143-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)‐‐a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377‐381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paris BL, Hynes DM. Diffusion, implementation, and use of Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) in the Veterans Health Administration (VA). JAMIA Open. 2019;2(3):312‐316. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Landes SJ, Kirchner JE, Areno JP, et al. Adapting and implementing Caring Contacts in a Department of Veterans Affairs emergency department: a pilot study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:115. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0503-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chang ET, Oberman RS, Cohen AN, et al. Increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder and complementary and integrative health services in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(Suppl 3):918‐926. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06255-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brunet N, Moore DT, Lendvai Wischik D, Mattocks KM, Rosen MI. Increasing buprenorphine access for Veterans with opioid use disorder in rural clinics using telemedicine. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):39‐46. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1728466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kelley AT, Dungan MT, Gordon AJ. Barriers and facilitators to buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder in the Veterans Health Administration during COVID‐19. J Addict Med. 2021;15(5):439‐440. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Farrar S, Ryan M, Ross D, Ludbrook A. Using discrete choice modelling in priority setting: an application to clinical service developments. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(1):63‐75. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayotte K, Warner M, Hubbard G, et al. Moneyball for Government. Disruption Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]