Abstract

Objective

To explore the feasibility of a rapid, community‐engaged strategy to prioritize health equity policy options as informed by research evidence, community‐voiced needs, and public health priorities.

Data Sources

Data came from residents in a midsized, demographically, and geographically diverse county over a period of 8 months in 2020 and an evidence review of the health equity policy literature during the same time period.

Study Design

A descriptive case study is used to explore the feasibility and potential value of a community codesigned approach to establish community priorities for health equity policy.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Evidence synthesis of health equity policy was conducted parallel to 15 community listening sessions across the county to elicit information on health needs. We used scoping review methods to obtain literature from academic databases and scholarly public health and policy organizations. This information was cross walked with themes from the listening sessions to identify 10 priority policy areas, which were taken back to the community for 15 participatory discussion and ranking sessions.

Principal Findings

The process appeared to authentically engage the input of 200 community members representative of minoritized groups while identifying 99 evidence‐informed policy levers to promote health equity. Discussion and ranking activities were successful in facilitating community discussion and policy decision making. Remote platforms may have limited the engagement of some residents while promoting the participation of others. Conducting information integration within the research team prior to community policy ranking sessions limited the community ownership over how policies were interpreted and communicated.

Conclusions

A combination of information integration and community ranking activities can be used to achieve community‐engaged policy prioritization of options in a fairly rapid period of time. While this process provides an example of authentic community ownership of policy prioritization, the compressed timeline limited the community's engagement in the information integration phase.

Keywords: codesign, community health, community participatory design, health equity, policy making

What is known on this topic

Communities of color and those in rural areas experience poorer health outcomes than White populations and suburban/urban areas.

Poor health outcomes in communities of color are in part due to reduced political influence over policies affecting health.

Community‐engaged policy making and research is a growing area of interest in public health practice.

What this study adds

A community‐engaged approach to policy prioritization (termed policy codesign in this project) was feasible to conduct over 8 months.

The process appeared to authentically engage community voices in two of the three key activities needed to produce policy priorities in a compressed timeframe.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coproduction and other co‐ownership methods of system and policy planning aspire to power sharing between community and government. 1 As a policy strategy, coproduction emerged in the 1970s with the aim of increasing democratic participation, as well as the fit and operation of government programs resulting from increased community input. This ideology is experiencing a resurgence. Palmer et al., in a 2018 article, referred to this last decade as a “participatory zeitgeist,” in which community involvement in the process of systems improvement is becoming a routine, and perhaps soon ubiquitous, approach to community health improvement efforts. 2 , 3 , 4

Equity‐focused health policy making requires attention to process, as well as product. As noted by Whitehead, 5 equity in health policy is not simply a matter of ensuring that policies benefit those most affected by health disparities. Rather, communities marginalized by racism and other identities should lead agenda‐setting and design in determining that policies to be developed and enacted. Such involvement is expected to produce multiple benefits, including policies that fit local needs, as well as increased community mobilization and empowerment. Community‐led policy making includes efforts such as People's Movement Assemblies, which are often facilitated by community organizer nonprofits and include large community meetings to move new policy proposals forward. 6 These community organizing efforts are often explicitly centered in a community vision of change and de‐colonization in which the gathering of people seeks “to practice power through participatory governance and to determine action plans for systemic change.” 7 The process by which research evidence may be used by these approaches to community‐led policy making is not well understood as information arising from elite institutions, such as universities, is sometimes viewed with skepticism. 8

Knowledge of what has worked to improve health equity in regions outside the local context is, however, valuable for achieving the second aim of equity‐focused health policy making, which is to effectively reduce health inequities. 5 A number of policies and policy‐enabled community programs are effective in improving community health among communities that traditionally experience health disparities, 9 , 10 , 11 and it is reasonable to presume that incorporating information about these efforts will benefit local health equity policy formation. As noted, it is unclear how this information is typically viewed or used in community‐led initiatives, 12 or much of government‐led policy making. Those advocating for more evidence‐informed policy making promote methods that bring research evidence into discussions in formal ways, including evidence syntheses or research‐practice partnerships. 12 , 13 , 14 Government may also commission forecasts to predict the effects of hypothesized policies using system modeling or policy analysis to attempt to approximate a precision approach to policy selection and design. 15 , 16 These latter approaches value specialist knowledge and expertise, values that potentially conflict directly with People's Movement Assemblies and the de‐colonization of decision making. Inherent in health equity policy making is a tension between the claims of community and those of researchers to authoritative knowledge. Community knowledge emphasizes process and the delegation of decision making and information gathering to those affected by policies, and research‐based knowledge emphasizes the selection and application of policies shown to be effective in reducing health inequities as identified in the scholarly literature.

1.1. Codesign and evidence‐informed policy making

Codesign and other collaborative planning models in health sciences research are recommended as methods suited for addressing complexity, of which policy formulation is one type. 17 In their review of cocreative research methods, Greenhalgh et al. note the potential for these efforts to achieve higher social impact than investigator‐led research efforts due to the greater buy‐in from community stakeholders, as well as the crafting of research ideas more proximally relevant to health services. 3 They term this process “Value Cocreation,” and identify four features common to cocreative model arising from diverse disciplines (e.g., business, digital health, participatory research). These include a systems perspective, individual creativity, collaborative process, and better fit and sustainability.

Similarly, cocreative methods are well‐suited to reconcile the tensions of knowledge authority in policy prioritization because they are an effective vehicle for moving decision making through a structured process while allowing for individual and collective creativity. 18 The growth of interest in cocreative models is signaling a shift in society's relationship with science, particularly in Europe and the Anglosphere countries (UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand). These countries and others, including Norway and the European Union, have well‐funded centers devoted to strengthening alliances between research, community, and health systems that value equal expertise and contribution. 19

To date, most of the work in cocreation focuses on knowledge production, that is, how to engage health care recipients and providers in the study of health care innovation. Applying cocreation in knowledge translation, that is, how is knowledge from research brought into real‐world decision making, raises a different set of interesting questions around power and equity than those raised in knowledge production alone. 20 Existing models of policy planning, even those adopting a participatory frame, do not always describe the methods of decision making clearly. Cocreative methods can be used to enhance the transparency of decision making process while also centering the creativity and participation of the individual. 21 For policy, this means various sources of information can be woven into the design process, including community input and pre‐existing research evidence relevant to the topic.

In this paper, we present a case study of the first phase of an approach to policy codesign (prioritization) that sought to partially reconcile the goals of community ownership and evidence‐informed policy making. We provide an overview of the conceptual grounding of the approach, which we term policy codesign. We then discuss what is gained and lost in this type of participatory enterprise and how the field might move forward to expand the study of similar approaches.

1.2. Conceptual frameworks informing the design approach

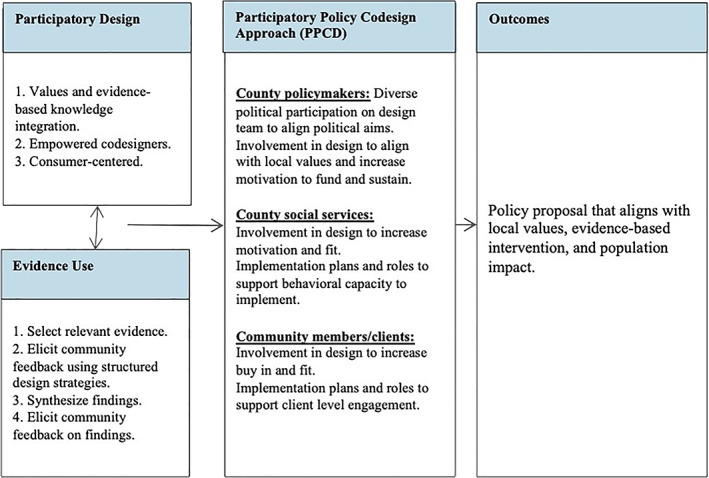

The approach to participatory policy codesign used in this effort was informed by participatory action research, Kingdon's policy streams theory, 22 and codesign methods in health services research. We also note the similarities in approach to emerging models of public policy codesign that reference systems theory, complexity theory, and design thinking in social innovation. 20 (Figure 1)

FIGURE 1.

Policy prioritization stage of policy codesign [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Participatory action research (PAR) is a reflective approach to sources of knowledge. It is skeptical of truth claims and is mindful of the extent to which knowledge is used to represent the interests of powerful institutions and people, thus reinforcing their positions in society. 23 It is a method inextricable from the intent to improve the conditions of under‐resourced individuals and groups. PAR is a knowledge production method that serves as an alternative to positivist methods, and the concepts of power, truth claims, and action can be readily applied to knowledge transfer efforts. 24

Kingdon's policy streams theory is widely used for its simplicity and explanatory power. 22 Policy streams theory proposes that three conditions must occur simultaneously for a policy to be supported (i.e., the law passed, the resolution adopted). These streams include (1) the problem stream, which indicates agreement among multiple sectors about a problem that needs to be solved; (2) the policy stream in which a viable solution to the problem appears to be available; and (3) the political stream in which the political will among the voters or other necessary constituents is organized around the solution. In addition to these three conditions, the theory proposes that the existence of a policy champion, someone or an organization, is critical for shepherding the policy through revisions, iterations, and the unpredictable conditions of policy making. 22

Cocreation is a quickly expanding and evolving field. 23 , 24 The differing approaches and emerging schools of cocreation, and codesign in particular, provide a number of methods that could be applied within policy coproduction. These efforts generally proceed in four stages: Setting the design question, Information gathering/integration, Prototyping, and Beta‐testing. 25 , 26 , 27 In health services innovation, the design question often comes from the investigator team (e.g., how can we improve the use of clinical guidelines by primary care physicians). In policy making, the design question is more likely to arise from negotiations between the government and stakeholders. This may begin with a broad area of interest (e.g., how can better land use support health in this community) that is narrowed over time with community input. 27 This case study focuses on the use of codesign methods to identify community‐directed policy priorities. We describe methods used in the first two phases of codesign, which included (1) setting a design question and (2) information gathering/integration.

2. METHODS

2.1. Setting and guiding frameworks

2.1.1. Community setting

We use a narrative approach in presenting an instrumental case study, guided by the approach outlined by Stake, 28 in order to examine the value of codesign methods for engaging the community in the prioritization stage of a policy codesign initiative. The project included two phases, a community listening phase and a community policy prioritization phase, and was carried out in a mid‐sized, Pacific Northwest county in the United States, Pierce County, Washington. Pierce County has a population of about 900,000 residents, encompassing 15 cities and five towns, and is predominantly White, non‐Latinx (65.7%), followed by Latinx (11.4%), Black/African‐American (7.7%), Asian (7.1%), mixed‐race (7.4%), American Indian/Alaska Native (1.8%), and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (1.8%). According to the US Census Bureau, about 9.4% of the population lives in poverty. 29 The policy codesign effort was a collaboration between the local health department (Tacoma‐Pierce County Public Health Department, TPCPHD) and a university‐based team through a subcontract from the county to the university using funds from the United States Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The methods used to gather information from this study were conducted as part of a local public health department activity and intended to inform local policy making rather than generalizable research. Community residents participating in these meetings were informed that their responses would be publicly shared as aggregated data. The methods of collecting data adhered to ethical standards and no identifying individual information was collected or stored as part of community listening and ranking sessions. The data presented in this paper are publicly available in two documents published by the Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department. 30 , 31 Because the data used in this case study is publicly available and the participants were informed that it would be aggregated and shared in public reports, the activities did not fall under human subjects review. 30 , 31

2.2. Case study and phases of policy codesign

2.2.1. Design question and team

The design question guiding the project was intentionally broad and focused on eliciting community health policy priorities under the general goal of health equity. The parameters for the policy effort set by the county required a focus on health inequity, policy, and participatory process. The TPCHD was already using the term “health equity” in multiple forums, including the facilitation of a multi‐sector “Equity Action Network,” in which equity was defined as “opportunity for all,” and focused efforts on communities with lower indices of social advantage and health. 32 Consequently, the design question guiding the subsequent activities to elicit community input was phrased as, “What health equity policies will build community health resilience, reflect community‐state health needs and reflect community priorities?” The core team leading the work included the TPCHD health equity manager, TPCHD government relations and health policy coordinator, and the university staff (lead investigator, operations specialist, research scientist). The advisory group included the TPCHD director of health, two PhD public health faculty, and a diverse group of business, health, government, and community members involved in the county's Equity Action Network (about 50 participants).

2.2.2. Information gathering and integration

To identify the most relevant and likely effective health equity policies for the county, we gathered information using two methods, (1) a scholarly review of the literature and (2) thematic coding of community listening sessions. The scholarly review required 4 months from the point of identifying search terms through the coding of policy areas and another 2 months for writing up findings. The community listening sessions occurred over 6 months and required a month of consensus coding. Collectively, these activities occurred over 8 months.

A rapid scoping review was conducted to identify policies with demonstrated effectiveness in promoting health equity or policies that addressed a need known to contribute to health equity. The terms used in the rapid scoping review were selected to follow the TPCHD's definitions of health equity, described above as “opportunity for all.” We followed guidance for rapid evidence reviews, 33 including restricting our search to the last 10 years of published scholarly work and searching primarily for systematic or conceptual reviews of health equity policies (see Appendix A). The review was supported by two PhD level public health research and practice experts with broad knowledge of the field, an MPH scholar who conducted the review, and a PhD level translational researcher with experience conducting scoping reviews. The experts reviewed terms and suggested additional gray literature sources to identify relevant policies. The search terms for the scholarly literature included “health equity policy,” “health in all policies,” “health equity impact,” “health inequity,” “health inequality,” “social determinants of health policy,” and “public policy and health” and “review.” Given the goal to conduct this review rapidly, we selected papers that explicitly referenced health equity (and related terms) in a title or keyword. This excluded papers that focused on a policy area likely related to health equity (e.g., housing affordability) but did not use eligible terms.

In addition to the academic literature search, eight professional organizations were identified for a gray literature search (Table 1). The two searches yielded 19 documents that were coded to extract policy recommendations with an impact on health equity. Coding involved a description of the policy, the specific policy lever (e.g., regulation, ordinance, tax, funding for a program), the effectiveness of the policy as described by the authors, and the evaluation or research method referenced in the study. Three individuals, two PhD level researchers, and one MPH evidence synthesis expert, established coding reliability by separately coding three articles and discussing minor discrepancies. An MPH coder then primary‐coded the remaining articles, all of which were reviewed by one of the PhD researchers, and spot‐checked by the second PhD researcher. Coding extracted 62 healthy equity‐related policies from these documents. Documents from the Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department and community listening sessions were also reviewed to identify additional health equity policies. An additional 37 policies from this search were added to the health equity policy list. This resulted in a final list of 99 health equity policies.

TABLE 1.

Examples of health equity policy areas, policy, policy lever, and source

| Policy area | Policy | Lever | Source (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Built environment | Fund the development of green spaces | Funding | NASEM, NACCHO |

| Regulate signage | Regulation | NACCHO | |

| Design traffic calming measures | Regulation | BMC Public Health Journal | |

| Chronic disease prevention | Pass a soda tax | Tax | NASEM |

| Pass a cigarette, tobacco tax | Tax | BMC Public Health Journal | |

| Pass an unhealthy food tax | Tax | BMC Public Health Journal | |

| Criminal justice | Fund treatment alternatives to incarceration/justice involvement | Funding | NASEM |

| Reduce police presence in schools | Relax current policies | TPCHD Internal Priority Document | |

| Fund reentry and support services for individuals released from jails | Funding | NASEM | |

| End zero‐tolerance policies in schools | Organizational | APHA | |

| Reduce over‐policing in areas with predominately BIPOC populations | Relax current policies | TPCHD Internal Priority Document | |

| Dispatch mental health workers instead of the police force | Funding | TPCHD Internal Priority Document |

Note: Additional policy areas are listed in Appendix A.

Abbreviations: APHA, American Public Health Association; BARHII, Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative; NACCHO, National Association of County and City Health Officials; NASEM, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; PICA‐WA Pacific Islander Community Association of Washington; TPCHD, Tacoma Pierce County Health Department.

Simultaneously, the Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department organized community listening sessions with the input and support of the Pierce County Equity Action Network (EAN). The listening sessions were intended to capture community social and health needs arising from or exacerbated by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Community leaders in the EAN were recruited to lead listening sessions and were identified as recognized representatives of cultural (e.g., Latinx) or geographic populations (e.g., regions of the county). Participants were recruited into listening sessions using email, text, and posted virtual flyers. Participant recruitment prioritized health vulnerable groups. Fifteen listening groups were eventually held with 214 community members from four regional areas, racial/ethnic groups (Black, Latinx, Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander), and youth/young adults. This resulted in 26 Black/African American community members, 34 youth and young adults, 27 Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander community members, and 95 Hispanic/Latinx community members, as well as 32 members from six communities of focus, which are areas that have poorer health outcomes due to various factors such as lower socio‐economic status, experiences with racism/discrimination, or rural location. 30

To promote consistency across listening sessions, the TPCHD provided three types pf facilitation training for community leaders and provided facilitators with a moderator/facilitator guide. Listening sessions were 60–90 min with 4–10 participants in each group. Each group had one facilitator and one note taker. Sessions were virtual using zoom and recorded with participant consent for note‐taking purposes. Participants gave consent to confidentially share their experiences with the Equity Action Network. Community members and facilitators reviewed and approved session notes before sharing them with Health Department analysts. The listening sessions were semi‐structured and included questions related to health and social needs broadly and specifically related to COVID‐19.

An inductive approach was taken to analyze qualitative data. Analysts from the Health Department's COVID‐19 Data & Surveillance branch reviewed transcriptions of audio/video files and performed qualitative analysis manually and with nVivo software to determine emerging themes. Analysts transcribed audio recordings into text and used open and axial coding to discover patterns and recurring themes across all focus groups. The university team and the qualitative analysis team from the Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department met to discuss the codebook for identifying policy areas from the listening sessions. Both teams independently reviewed transcripts to identify themes and jointly reviewed results to resolve any areas of disagreement using a consensus approach. The joint coding resulted in 100% agreement.

Coding involved assigning a score of “1” for each policy area (of the final 28) mentioned in each session. Separate listening sessions were grouped by community type (e.g, Latinx, Native American, Community of Focus), and summed policy areas scores across each community type. From these totals, the policy areas with the highest scores (e.g., mentioned across multiple community types) were selected as a high priority. These high‐priority policy areas were compared to health priorities previously identified and published by the TPCHD. 30 Policies identified on both lists were selected, as well as the next highest ranked policies from the community listening sessions, in order to identify 10 final policies (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Community ranking sessions and policy area ranking results

| Policy area ranking results | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking session | N value | Housing affordability and accessibility | Economic stability | Behavioral and physical health care access | COVID specific care | Food affordability and accessibility | Education access | Youth behavioral health | Healthy community planning and built environment | Early childhood development | Youth behavioral health |

| November 9: Group 1 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 6 |

| November 16: Group 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 10 |

| November 18: Group 3 | 30 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| November 20: Group 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 9 |

| Group 4 Absentee Vote | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 8 |

| November 23: Group 5 | 31 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 9 |

| November 24: Group 6 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 3 |

| November 24: Group 7 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| November 24: Group 8 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| December 2: Group 9 | 21 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 8 |

| December 4: Group 10 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| December 5: Group 11 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 10 |

| December 7: Group 12 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 2 |

| December 14: Group 13 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| January 7, 2021: Group 14 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| Average | 2.4 | 3.27 | 3.93 | 4.80 | 4.87 | 6.33 | 7.53 | 7.73 | 7.73 | 7.53 | |

Note: The table above shows 14 groups and how they ranked each policy area from 1 through 10, with 1 being the most important and 10 the least important. The average was then taken for each policy area, and the top three policy areas had the lowest averages.

2.2.3. Community policy discussion and ranking

Following the identification of the 10 priority policy areas, the design team facilitated community participatory discussion and ranking exercises to engage broad‐based (horizontal) engagement with the community, including and extending beyond community groups involved in the EAN listening sessions. The participatory ranking is a strategy used in low resource areas and, increasingly, high‐income countries to engage the community directly in making policy‐level decisions. We adapted a process used by the CPC Learning Network. 34 In its original form, the participatory ranking exercise involved community members placing objects in physical locations to vote on different community priorities. Our adaptation used web‐based video (Zoom) and ranking (Mentimeter) primarily because the codesign project occurred during the COVID‐19 pandemic and in‐person meetings were not an option. In two sessions, real‐time language translation was provided in Spanish. All other ranking sessions were conducted in English.

A total of 14 community groups, largely organized around race/ethnicity cultural identification, participated in the participatory ranking sessions, and a total of 163 community members participated in the ranking (Table 2). The ranking sessions began with a short presentation of the participatory policy codesign initiative, the process for narrowing policy options down to the 10 priority areas, and a brief discussion along with a definition of each policy area. Following this overview, participants were asked to rank the options from 1 to 10 by navigating to a weblink pasted into the video‐call chat‐box. Those who could not access the weblink were asked to share their rankings in the chat or raise their hand to verbalize their rankings. Following the first ranking, the group reviewed live results, and the facilitators prompted a discussion with reflective questions, including “what influenced your choice to rank behavioral health policy more highly than affordable housing?” In larger meetings, participants were placed in breakout rooms for discussion. After a period of discussion, the group was given the option to re‐rank their choices using a new poll.

The numeric rank‐order scores from each session were averaged to produce an average ranking score for each policy area. The top three policies (Economic equity, Housing affordability, Behavioral and physical health care access) were selected for inclusion in a second phase of codesign that is still ongoing. The currently ongoing second phase of the PPCD process involves bringing a community and policy design team together to prototype out a specific policy to address the top three priorities identified in the first phase of the project.

3. RESULTS

This case study is provided to illustrate the methods used to execute a fairly rapid community engagement and knowledge synthesis process to guide health equity policy priority setting across a mid‐sized county, with the goal of achieving geographical and cultural representation. The questions asked by this case study are guided by concerns in the relevant literature about the possibility of authentic representation of the community in public policy codesign, and how scientific evidence is integrated with other forms of knowledge in the policy prioritization stage.

In this effort, authentic representation was viewed as demographic representativeness within a target population (those with health vulnerabilities) and participatory representativeness in decision making. Outreach strategies successfully engaged residents from under‐resourced groups (rural, minoritized individuals, communities with poorer health metrics). The volume of participation was low relative to the total population (0.03%), and within each demographic, due to the compressed time frame. Participatory representativeness appeared to be achieved as the approach was successful in communicating complex policy options to community members. A relatively reliable indicator of whether participants understand the material is if they will discuss it in group situations. The facilitators reported good engagement from participants, suggesting that community members were able to understand the options well enough to ask for clarifying information and state preferences in a group discussion. Early facilitation also suggested the need to add short, written definitions in addition to policy titles on materials presented during ranking sessions. However, COVID‐19 restrictions also limited community engagement to zoom. This likely reduced the involvement of residents without access tothe Internet or familiarity with the video platform and may have impacted the priorities chosen in the ranking sessions.

The codesign approach provided scholarly information in a manner that followed community‐grounded preferences by using a “pull” rather than “push” approach to information‐gathering. 35 Of 99 individual policies and 28 policy areas identified by the investigators, only 10 areas were brought back into the second set of community sessions where they ranked policy areas based on their top priorities. This could potentially be viewed as a wasteful scholarly effort, as less than 50% of the information gathered by the design team was brought back into community sessions. At the same time, this ensured that important framing arguments were not overlooked when compiling the research literature and helped the investigator team conceptually connect ideas between the community listening session comments and the health equity policy areas. 36 , 37 In this effort, the design team integrated information (compared and coded the scholarly literature and community listening sessions) given the short timeframe. A more robust community‐engaged approach would either include or entirely defer information integration to community residents, and this might also yield different interpretations and findings than what emerged using the present approach.

4. DISCUSSION

This paper has described, with a conceptual framework and case study, the key considerations in the community priority setting the stage of a health equity policy codesign initiative. We use this case study to reflect on the capacity of codesign to address power, transparency, appropriate use of scholarly knowledge, and authentic community engagement in policy formation.

This approach to policy prioritization was particularly concerned with whether the separate goals of evidence‐informed policy making and community ownership could be reconciled. As noted by Greenhalgh et al., the field has yet to develop a coherent scientific paradigm for how cocreation intersects with the science of research use in public policy. 3 The field of “research use,” “use of research,” “evidence‐informed policy making,” and increasingly, “policy implementation science,” begin from the values stance that research evidence has something to offer public policy formation in the individual (federal, state, county, city) case. This may include epidemiological evidence that specific groups have poor health outcomes that should be the focus of policy making efforts (e.g., Black maternal mortality) or evidence showing that specific policies can affect population‐level health (e.g., soda tax and obesity). To the extent the current field offers prescriptive guidance for policy formation, it is either to select the optimal policy levers to promote other evidence‐based practices or programs, such as funding mechanisms, 38 , 39 or to identify the communication and planning strategies needed to implement an identified policy. 40

Our case study presents an alternative method for the selection of evidence‐informed policies that achieved a meaningful integration of community‐engaged decision making and scholarly information with some limitations. This approach still imposed limits on community ownership, largely due to the pressure to work within a compressed timeframe. A participatory stance views the facilitator (often a researcher or content expert intermediary) as a holder rather than the intellectual owner of a design process. 41 This stance was adopted in the TPCHD project by deferring all decision making to a transparent process that engaged two levels of community voice (Equity Action Network representation and individual community participants). The only constraint placed upon community decision making was the lack of participation in integration information from the community listening session and evidence review. This gave the core team control over interpretation, as well as how policy options were defined and communicated, which generally adopted language common in the scholarly area (e.g., built environment).

A more transparent and community‐engaged process would share or entirely delegate interpretation to community representatives. Such an approach would be better aligned with Participatory Action Research (and CBPR) values and would likely have served to (1) More broadly engage the community in feeling ownership over the identifies policy priorities; and (2) Build capacity among the community to interpret and use policy‐relevant knowledge. It is also possible that including community members in synthesis and interpretation would have strengthened interpretation and made the prioritization process more accurately reflect community strengths and needs. The core team made the choice to keep synthesis internal at this phase because the core team planned to engage more active community participation in interpreting knowledge in the prototyping phase. The next phases of the codesign approach (Prototyping and Beta‐testing) will involve bringing a new design team together to prototype a specific policy as guided by the prioritization process. The design team will be structured to capitalize on existing relationships and political sway so that the policy developed by the team will be championed by those who are positioned to take it forward through implementation.

The approach and data used in this case study analysis include some limitations. The political climate in Pierce County is friendly to community‐engaged approaches and friendly to the use and application of the term “health equity.” These two orientations will vary by county. Some county political climates may be highly responsive to populace concerns, while others may prefer to more tightly manage knowledge and decision making. Given this, it is likely that not all communities will be good candidates for health equity‐focused policy design, and not all counties will be ready to apply participatory strategies.

5. CONCLUSION

This case study presents codesign methods used to integrate three sources of knowledge, the evidence‐based, public health priorities, and community‐expressed needs, in a way that engaged community decision making in setting public health policy priorities. By leveraging existing processes and relationships, the public health department was able to rapidly mobilize community groups to contribute to policy priority setting through listening sessions and participatory ranking sessions. Similarly, the core team was able to rapidly glean key policies from the academic literature using rapid review methods and integrate these with community information using thematic coding and quantitative summaries. More study is needed to assess how well community members authentically grasped policy options in community ranking exercises and how the policy priorities emerging from these methods compare to priorities that may have emerged from lengthier community engagements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the contributors of this report, including other staff at the Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department and the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice at the University of Washington. We also would like to especially thank the Health Department community partners who helped to facilitate the listening sessions, as well as reviewing and approving results with community members: Asia Pacific Cultural Center, Compact of Free Association (COFA), Alliance National Network of Washington, Odilia Campos‐Estrada, Community Health Worker (CHW), Catherine's Place, Centro Latino, College Success Foundation, Leonila Correa, (CHW)‐Faith, Health and Action Latinx Health Ministers, Grupo San Miguel de San Frances de St Cabrini in Lakewood, Harvest Pierce County/Pierce Conservation District, Latinx en Accion, Latinx Unidos of the South Sound, Key Peninsula Partnership for a Healthy Community, The Multicultural Child and Family Hope Center, Power of Two, Springbrook Connections, The Tacoma Women of Color Collective, United Way of Pierce County. In addition, we would also like to thank the Health Department staff and community partners who helped facilitate the policy ranking sessions and approve results with community members: Asian Pacific Cultural Center (APCC), Equity Action Network, Compact of the Free Association Alliance National Network of Washington (CANN‐WA), the Pacific Islander Task Force, Communities of Focus: Parkland, Springbrook, and White River, Black/African American Partners, Latinx en Accion, Latinx Unidos of the South Sound (LUSS), and the Black Collective: Health Committee.

APPENDIX A. DESCRIPTION OF THE HEALTH EQUITY SCOPING REVIEW CONDUCTED FOR THE COMMUNITY‐ENGAGED, POLICY PRIORITIZATION EFFORT

A scoping approach was selected as the method used for the review of evidence and best practices, given the focus of scoping reviews on broad questions. Scoping reviews are typically interested in how the scholarly literature addresses a topic and summarizes descriptive details of the research approaches, including, for example, the location of the research studies, the conceptual frameworks used in the studies, the variables and constructs in the research, and in some cases, general summaries of the strength of evidence or direction of results. Scoping reviews can also be used to describe the breadth of literature, the strength of evidence or trends in effects, and is often used to describe gaps in the literature. Our scoping review most closely resembled the aims of the second approach with a goal of extracting policy approaches from the literature and describing their mechanism (lever) and effectiveness.

The focus of the scoping review was dictated by the county public health department and a department's interest in improving health equity. As described in the manuscript, the Tacoma Pierce County Public Health Department had previously defined health equity as “opportunity for all,” and the researchers involved in the scoping review worked closely with TPCPH staff in identifying search terms. We followed guidance for rapid evidence reviews, 33 including restricting our search to the last 10 years of published scholarly work and searching primarily for systematic or conceptual reviews of health equity policies. The review was supported by two PhD level public health research and practice experts with broad knowledge of the field, an MPH scholar who conducted the review, and a PhD level translational researcher with experience conducting scoping reviews. The experts reviewed terms and suggested additional gray literature sources to identify relevant policies. Given the rapid nature of the review, the team did not register the protocol as a scoping review.

To be eligible for further review, the title or subtitle of the document needed to include one of our search strings related to “health equity” (see below), and the abstract, title page, or table of contents needed to reflect a focus on reviewing specific policies and their relationship to health equity.

The search terms for the scholarly literature included “health equity policy,” “health in all policies,” “health equity impact,” “health inequity,” “health inequality,” “social determinants of health policy,” and “public policy and health” and “review.” Given the goal to conduct this review rapidly, we selected papers that explicitly referenced health equity (and related terms) in a title or keyword. This excluded papers that focused on a policy area likely related to health equity (e.g., housing affordability) but did not use eligible terms. Search databases included PubMed, Academic Search Complete, and Web of Science for the scholarly literature restricted to review articles. We did not identify any review articles (systematic, scoping, umbrella) summarizing the evidence of health equity policies. We did identify review articles addressing approaches to developing health equity policy, but did not provide a review of the policies developed. Thus, these articles did not meet our eligibility requirements. Given the lack of peer‐reviewed literature summarizing health equity policy, broadly, we turned to publications from highly regarded institutions. With the input of two PhD public health researchers, the review included searching the websites of eight different organizations for a gray literature search. These organizations included the American Public Health Association (APHA), the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII), the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the Community Guide from the Community Preventative Services Task Force (CPSTF), the National Academy of Science and Medicine (NASEM), the National Association of County and City Officials (NACCHO), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Following the search for health equity, broadly, a secondary search was conducted to identify health equity policies in the area of youth behavioral health, specifically. This search was conducted at the request of the Equity Action Network and TPCPH given a strong interest in addressing behavioral health in the region. The search terms included “behavioral health policy,” “youth behavioral health policy,” “mental health policy,” “youth mental health policy,” and “public policy on mental health” and “review.” We conducted this search using PubMed, Google, Google Scholar, and the University of Washington Library. This search resulted in seven articles that met our eligibility criteria.

The above searches (two scholarly reviews, one gray literature search) yielded 13 documents from which we extracted 62 unique policies recommended by the scholarly field. Each policy was coded using a framework developed by the researcher team with input from two PhD public health researchers and the TPCPHD. This included the policy area (“built environment”), the policy aim (“design traffic calming measures”), the policy lever (“municipal regulation”), the evidence cited for the policy in the document (cited/not cited), and the strength of the evidence (mixed, weak, strong, counterindicated). An MPH researcher and PhD research double‐coded policies and reviewed inconsistencies to come to a shared understanding of coding until double‐coding was 100% in agreement. The MPH researcher then coded the remaining policies, and the second coder spot‐checked the results. The review did not use a formal critical appraisal of evidence checklist given the range of study types; rather, a coding was informed by hierarchies of evidence used by evidence clearinghouses: Weak (noncontrolled, descriptive studies or randomized/quasi‐experimental studies with low effects), Strong (randomized/quasi‐experimental studies with moderate to strong effects), Mixed (some outcomes were supported and others were unclear or not supported), Counter‐indicated (the policy increased negative health outcomes overall or in subpopulations).

The synthesis categorized 99 policies under 28 policy areas (37 policies were identified from the listening sessions and public health documents and were added to the 62 policies arising from the scholarly review). Most policies were not evaluated sufficiently to draw conclusions about effectiveness. We were only able to code “Mixed” effects for two policies, both taxes, one on food and one on soda. A little over half of the policies identified in the review cited epidemiological evidence in support of the policy but had no evidence of the policy's effectiveness. Given the limited evaluations of health equity‐related policies, we omitted this from our tables summarizing the results of the review.

We also describe here the process for selecting the 10 policies that were taken back to the community in policy prioritization, ranking, sessions. The list of policies being considered for the Long List was generated with three sources of input: Policy suggestions presented by community listening sessions not already identified by scholarly review; Scholarly reviews of policies shown to have an influence on reducing health inequities; Policy suggestions presented by public health department input not already identified by the scholarly review.

Below is the specific process used to develop the Long List:

- Select policy areas that match identified priorities from community listening sessions

- Four groups: Latinx, NHOPI, Youth, and Black/African American Coalition

- All policies matching identified priorities for at least three groups ( ~>75%) are selected

- Select policy areas that match identified priorities from Communities of Focus.

- Six groups: East Tacoma, Key Peninsula, Parkland, South Tacoma, Springbook, and White River

- All policies matching identified priorities for at least four groups (~>66%) are selected

- Select policy areas relevant to Tacoma‐Pierce County's “2 Bold Asks”:

- Maternal smoking cessation and youth behavioral health

- At least one of the bold asks (youth behavioral health) will be represented on the final list (~>50%) until the Long List reaches 10.

- Select policy areas that have rigorous evidence support for reducing health inequities

- All policies meeting “recommended (strong evidence)” by the community guide (thecommunityguide.org) are selected until the Long List reaches 10.

- All policies rated as having strong evidence by research expert on the team using original sources are selected until the Long List reaches 10.

- Select policy areas that match both CHA and CHIP 2019 priorities

- Add any policy areas that match CHA and CHIP priorities until the Long List reaches 10.

- Use list of identified policy areas and cross‐check with TPCHD health equity indicators

- 10 health indicators:

- Percentage of registered to vote (sources: WA State Secretary of State and ACS)

- Percentage of children ages 0–7 for whom there dependency filings (source: WA State Dept. of Children, Youth, and Families)

- Percentage of residents who are persons of color (sources: OFM and ACS)

- % of adults with any college (source: ACS)

- Percentage of persons ages 5 and older with limited ability to speak English (source: ACS)

- Percentage of kids ready for kindergarten (source: WA State OSPI)

- Median household income (source: ACS)

- Percentage of households paying more than 30% of income towards housing (source: ACS)

- Percentage of health insurance (sources: BRFSS and ACS)

- Percentage of those who have a primary care provider (sources: BRFSS)

- Identified Long List of policy area must be connected to at least one of these indicators

Walker SC, White J, Rodriguez V, et al. Cocreating evidence‐informed health equity policy with community. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(Suppl. 1):137‐148. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13940

Funding information Tacoma‐Pierce County Health Department; United States CARES Act

REFERENCES

- 1. Goodwin G. The problem and promise of coproduction: politics, history, and autonomy. World Dev. 2019;122:501‐5132. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palmer VJ, Weavell W, Callander R, et al. The participatory zeitgeist: an explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Med Humanit. 2019;45:247‐257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through Cocreation in community‐based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicholson RA, Kreuter MW, Lapka C, et al. Unintended effects of emphasizing disparities in cancer communication to African‐Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(11):2946‐2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Copeland D. What is the people's movement assembly process? The Michigan Citizen. 2011. 33(23).

- 7. Project South . The peoples movement assemblies offer spaces for us to practice community governance and to coordinate together across multiple strategies and multiple geographies. 2015. https://projectsouth.org/global-movement-building/peoples-movement-assemblies/

- 8. Bherer L. Successful and unsuccessful participatory arrangements: why is there a participatory movement at the local level? J Urban Aff. 2010;32(3):287‐303. [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. The National Academies Press (US); 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomson K, Hillier‐Brown F, Todd A, McNamara C, Huijts T, Bambra C. The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high‐income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alegria M, Perez D, Williams S. The role of public policies in reducing mental health status disparities for people of color. Health Aff. 2003;22(5):51‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence‐based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576‐1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armstrong R, Waters E, Moore L, et al. Understanding evidence: a statewide survey to explore evidence‐informed public health decision‐making in a local government setting. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):188‐188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, et al. Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: intervention design and implementation plan. Implement Sci. 2013;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2010;37(1–2):15‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lempert RJ, Groves DG. Identifying and evaluating robust adaptive policy responses to climate change for water management agencies in the American west. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2010;77(6):960‐974. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(95):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen R. Design thinking: a unified framework for innovation. 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/reuvencohen/2014/03/31/design-thinking-a-unified-framework-for-innovation/?sh=119824fe8c11.

- 19. José G. Policy Initiatives to Enhance the Impact of Public Research: Promoting Excellence, Transfer and Co‐Creation. OECD Publishing; 2019:81. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blomkamp E. The promise of co‐design for public policy. Aust J Public Adm. 2018;77(4):729‐743. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Co‐creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDes Int J CoCreation Des Arts. 2008;4(1):5‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, Update Edition, with an Epilogue on Health Care. 2nd ed. Pearson (US); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854‐857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koning KD, Martin M. Participatory Research in Health: Issues and Experiences. Zed Books (UK); 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verbiest MEA, Corrigan C, Dalhousie S, et al. Using codesign to develop a culturally tailored, behavior change mHealth intervention for indigenous and other priority communities: a case study in New Zealand. Transl Behav Med. 2018;9(4):720‐736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co‐design pilot. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):785‐801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walker SC, Weil L, Gilbert E, Baquero B. A scoping review of codesign approaches for evidence‐informed public health improvement: revisiting design for, with, and by community. In review.

- 28. Stake RE. A personal interpretation. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1985;7(3):243‐244. [Google Scholar]

- 29. United States Census Bureau . Quick Facts Pierce County, Washington. 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/piercecountywashington.

- 30. Tacoma Pierce County Health Department . Pierce County COVID‐19 health equity assessment. 2020. https://www.tpchd.org/home/showpublisheddocument/8213/637538139761730000

- 31. CoLab for Community and Behavioral Health Policy . Policies to advance health equity. 2020. https://www.tpchd.org/home/showpublisheddocument/8357/637469051767170000

- 32. Tacoma Pierce County Health Department . Equity action network. n.d. https://www.tpchd.org/healthy-people/health-equity/equity-action-network

- 33. Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A Practical Guide. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258698/9789241512763-eng.pdf;jsessionid=37CA408E4F4AA512E634DB5CBB417055?sequence=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34. Ager A, Stark L, Potts A. Participative ranking methodology: a brief guide. 2010. http://www.cpcnetwork.org/resource/prm-a-brief-guide/

- 35. Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):171‐181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore G, Redman S, Haines M, Todd A. What works to increase the use of research in population health policy and programmes: a review. Evid Policy. 2011;7(3):277‐305. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moore G, Redman S, Rudge S, Haynes A. Do policy‐makers find commissioned rapid reviews useful? Health Res Pol Syst. 2018;16(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raghavan R, Bright CL, Shadoin AL. Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence‐based practices in public mental health settings. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoagwood KE, Purtle J, Spandorfer J, Peth‐Pierce R, Horwitz SM. Aligning dissemination and implementation science with health policies to improve children's mental health. Am Psychol. 2020;75(8):1130‐1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Collie A, Zardo P. Predicting research use in a public health policy environment: results of a logistic regression analysis. Implement Sci. 2014;9:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaethler M, De Blust S, Devos T. Ambiguity as agency: critical opportunists in the neoliberal city. CoDes Int J CoCreation Des Arts. 2017;13(3):175‐186. [Google Scholar]