Abstract

Oligomannose-type glycans on the spike protein of HIV-1 constitute relevant epitopes to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs). Herein we describe an improved synthesis of α- and β-linked hepta- and nonamannosyl ligands that, subsequently, were converted into BSA and CRM197 neoglycoconjugates. We assembled the ligands from anomeric 3-azidopropyl spacer glycosides from select 3-O-protected thiocresyl mannoside donors. Chain extensions were achieved using [4+3] or [4+5] block synthesis of thiocresyl and trichloroacetimidate glycosyl donors. Subsequent global deprotection generated the 3-aminopropyl oligosaccharide ligands. ELISA binding data obtained with the β-anomeric hepta- and nonamannosyl conjugates with a selection of HIV-1 bnAbs showed comparable binding of both mannosyl ligands by Fab fragments yet lesser binding of the nonasaccharide conjugate by the corresponding IgG antibodies. These results support previous observations that a complete Man9 structure might not be the preferred antigenic binding motif for some oligomannose-specific antibodies and have implications for glycoside designs to elicit oligomannose-targeted HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies.

Keywords: Synthesis, Glycosylation, Oligomannoside, HIV/AIDS, Glycoconjugate

Graphical Abstract

Anomeric hepta- and nonamannoside 3-aminopropyl derivatives were prepared in good overall yields using a block-wise assembly followed by conversion into neoglycoconjugates. CRM197 conjugates of the β-variants showed comparable binding to Fabs of HIV-1 neutralizing PGT antibodies, but stronger binding of the heptamannosides by the corresponding IgG antibodies.

Introduction

Developing an effective vaccine against HIV-1 has not been successful despite many years of intense efforts.[1,2] The HIV-1 envelope spike (Env) harbors a dense array of glycans that may serve as targets for vaccine development, given their potential to generate broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs).[3] Among the heavily glycosylated patches of gp120, oligomannose-type glycan clusters constitute neo-epitopes suitable for eliciting bnAbs, as exemplified by the prototype PGT125–131 family of antibodies.[4,5] Previous attempts to produce oligomannose-specific bnAbs used glycoconjugates with dense oligomannosyl clusters, but these attempts have only modestly been successful.[6] The reasons for the lack of success are not clear. One hypothesis, reviewed elsewhere[7], is that, due to the similarity of synthetic oligomannosides to self-antigens, tolerance mechanisms may prevent the development of proper cross-reactive B cells. Another hypothesis, suggested by recent findings, is that serum mannosidases, first reported some time ago,[8] rapidly degrade oligomannose-containing ligands and thus prevent B cell recognition.[9,10] Preferential B cell recognition of only select parts of the neoglycosides, rather than the whole moiety, cannot be ruled out entirely either.[11]

We have previously shown that a bacterial oligomannoside mimetic[12] elicits modest neutralizing activity, with binding specificities comparable to those of the PGT125–131 bnAb family members.[13,14] The lead mimetic comprised the so-called “D1” and “D3” arm of the Man9 epitope and was equipped with a β-linked 3-propylamino aglycon for conjugation to a protein carrier (e.g., bovine serum albumin or the diphtheria-derived CRM197).[15] No HIV peptide sequence is included because of reports showing that glycopeptides elicit nearly exclusively anti-peptide, rather than anti-glycan antibodies.[16] During the previous synthesis, the β-anomeric spacer derivative 2 had been prepared from the commonly used thioglycoside pentamannosyl donor 1, albeit as the minor anomer (α/β ratio 2.5:1) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Previously used route to introduce the β-anomeric spacer group.[13]

We set out to improve the overall yield for the preparation of the lead β-heptamannoside antigen, based on an early introduction of the spacer unit and to synthesize additional building blocks to access the complete Man9 nonasaccharide. The α-configured heptamannoside had successfully been used in crystallographic studies with the PGT128 bnAb and since the corresponding BSA conjugates were also bound – albeit with lower avidity- to PGT128 and the 2G12 Ab, we include the synthesis of the α-nonasaccharide.[13,17] We also report on the preparation of the corresponding neoglycoproteins as bovine serum albumin (BSA) and CRM197 conjugates and ELISA binding studies with select members of the PGT125–131 bnAb family.

Results and Discussion

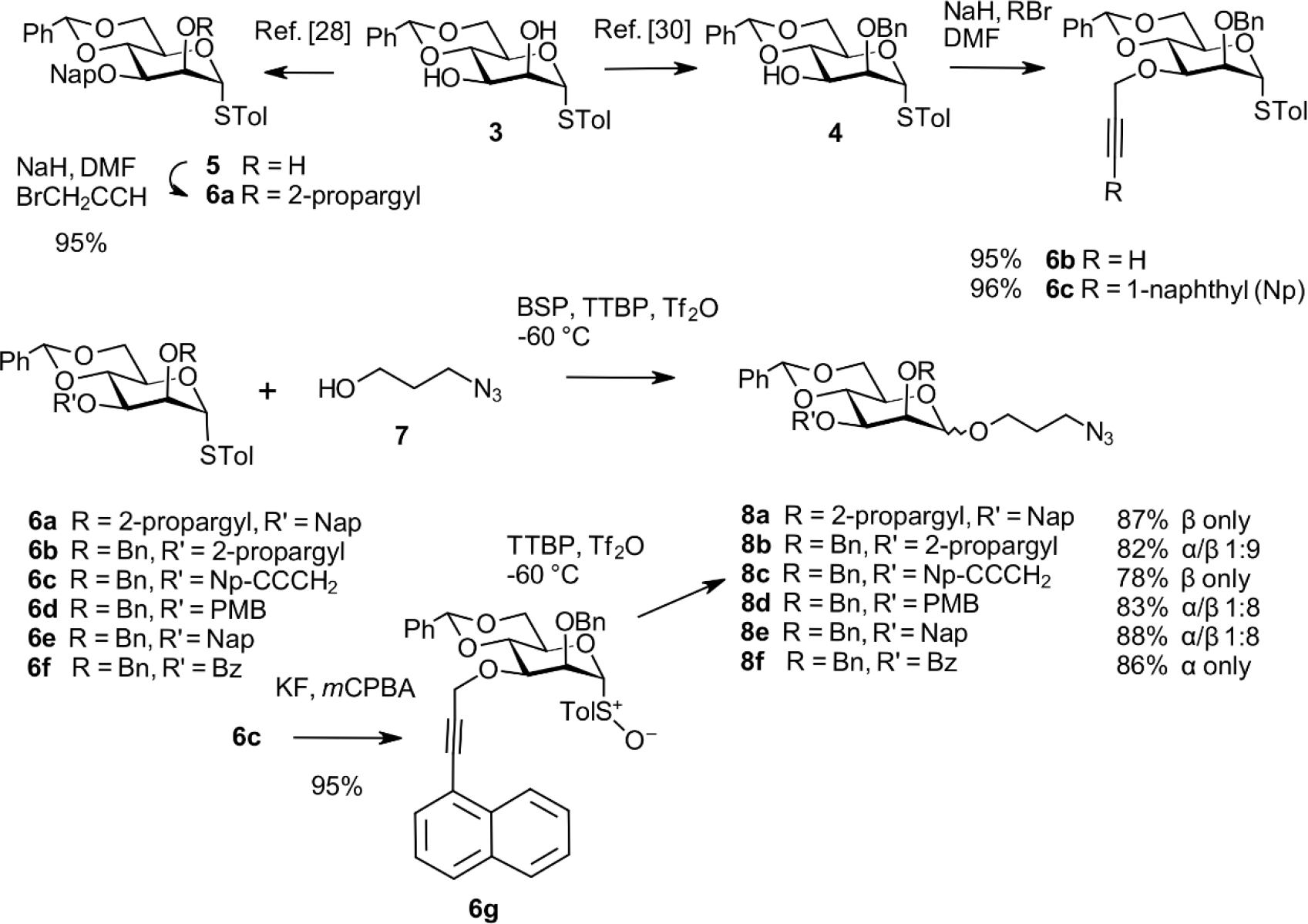

To improve the overall yield of the β-configured ligands, we first investigated the challenging synthesis of the 1,2-cis connected spacer aglycon at the monosaccharide stage. We based our investigation on torsionally disarmed 4,6-O-benzylidene mannopyranosyl thioglycosides, as investigated thoroughly by Crich and others.[18–20] Additional approaches towards β-selective mannopyanosides have been reported. Notable examples are intramolecular (IAD)[21] and hydrogen-bond-mediated aglycon delivery,[22] C-2 inversion of β-glucopyranosides,[23] anhydro derivatives,[24] and anomeric alkylation.[25] The 4,6-O-benzylidene protocol provides a versatile intermediate for the late introduction of the 1→6 mannosyl arm and several options for introducing orthogonal protecting groups. Furthermore, installing ether-type protecting groups with low sterical impact at the 2-O- and 3-O-positions has been beneficial for exquisite β-selective properties in the respective glycosyl donors.[26] Since we aimed for a robust and scalable method to efficiently synthesize anomeric spacer mannosides, a series of thiocresyl 4,6-O-benzylidene mannosides, protected differently at positions 2 and 3, were prepared. This alternate method also optimizes the protecting group strategy to synthesize both anomeric glycosides efficiently. Starting from the known[27] S-tolyl mannoside 3, a 3-O-(2-naphthalenylmethyl) group was installed as described,[28] followed by alkylation of 5 with propargyl bromide in the presence of NaH in DMF to afford 6a in 95% yield (Scheme 2).[29] The 3-O-(1-naphthylpropargyl) derivative 6c was synthesized from 3 via the known[30] 2-O-benzyl thioglycoside 4 followed by subsequent alkylation in 95% yield.[31] Donors 6b, 6d, 6e, and 6f were prepared as described.[32–35] Sulfoxide 6g was obtained by oxidizing thioglycoside 6c with m-chloroperpenzoic acid. Glycosylation of these donors with 3-azido-1-propanol 7 was performed at −60 °C with 1-benzene-sulfinyl piperidine (BSP), tri-tertbutylpyrimidine (TTBP), and triflic anhydride (Tf2O) as described by Crich et al.[36] All glycosylation reactions were conducted under identical conditions, yielding the spacer glycosides 8a–8f in good yields (78–88%). The 2-propargyl derivatives 8a and 8c were formed as single β-anomers, whereas the 3-O-propargyl donor 6b afforded 8b as a 1:9 α/β mixture. A comparable outcome was obtained with the 3-O-para-methoxybenzyl and 3-O-(2-naphthalenylmethyl) donors, providing the spacer glycosides 8d and 8e as 1:8 α/β mixtures, respectively. In contrast, the 3-O-benzoyl product 8f was isolated as the single anomeric α-glycoside in high yield. The stereodirecting group of an ester group at C-3 has been reported to form α-mannosidic C- and O-glycosides [36–38] and α-L-rhamnopyranosides.[22a] The anomeric configuration of the spacer glycosides was verified by measuring the heteronuclear JC1,H1 coupling constants.[39]

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the anomeric spacer glycoside derivatives 8a–8f.

Synthesis of hepta- and nonasaccharides containing the α-linked spacer group

We synthesized the oligosaccharides once selective access towards both anomeric spacer mannosides was established. Assembly was first elaborated for the α-series starting from 8f. The 3-O-benzoyl ester was removed under Zemplén conditions to give the glycosyl acceptor 9 in 94% yield (Scheme 3). For assembly of the D1 arm comprising the α-(1→3)-linkage to the reducing mannose unit, the trichloroacetimidate glycosylation approach was selected.[40] Coupling of the previously described[41] trisaccharide donor 10 to the acceptor 9 thus proceeded smoothly with the help of TMSOTf within 1 h at room temperature. It afforded the α-(1→3)-linked tetrasaccharide 11 in excellent yield (91%). Regioselective reductive opening of the 4,6-O-benzylidene acetal using triethylsilane and PhBCl2 at low temperature produced the primary alcohol 12 in 96% yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the tetrasaccharide acceptor 12.

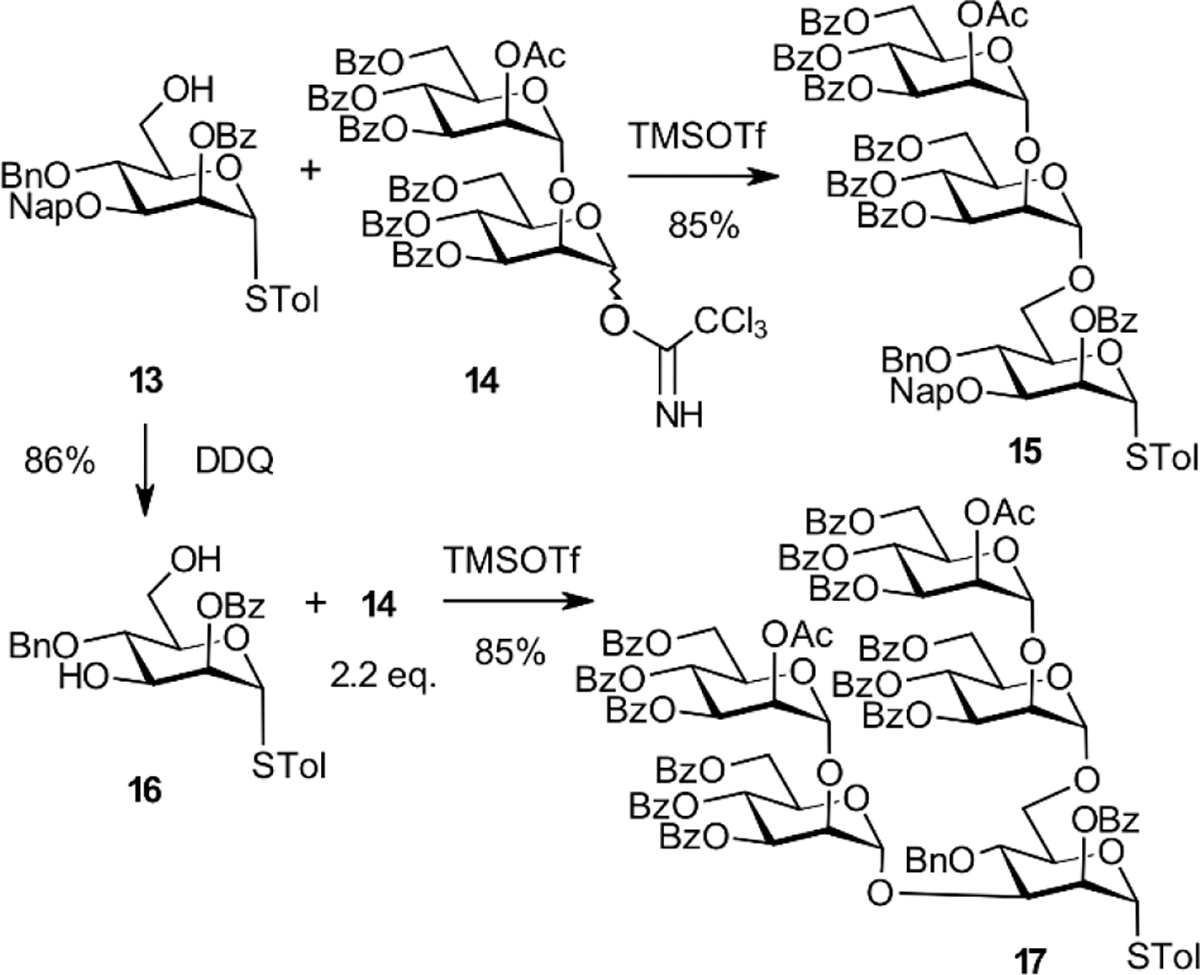

The previously described[42] primary alcohol 13 was glycosylated with the disaccharide trichloroacetimidate donor 14[43] to obtain the linear trimannosyl donor 15. TMSOTf was used to promote glycosylation, thus producing the α-(1→6)-extended thioglycoside donor 15 in 85% isolated yield (Scheme 4).[42] The3-O-Nap derivative 13 was subjected to DDQ-oxidation to generate diol 16 in an 86% yield to access the branched pentasaccharide donor 17. Simultaneous introduction of the D2 and D3 arms was then achieved by glycosylation of this diol acceptor with the disaccharide donor 14.[43] Assignment of the α-anomeric configurations was supported by the heteronuclear coupling constants JC-1,H-1.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of tri- and pentasaccharide glycosyl donors 15 and 17.

Next, the protected heptasaccharide 18 was synthesized by glycosylation of the primary alcohol 12 with the trisaccharide thioglycoside donor 15. NIS/triflic acid promoted the reaction, and an 82% yield was achieved. Due to the 2-O-participating benzoyl group in donor 15, the reaction proceeded with full stereocontrol, leading to the α-(1→6)-linked heptasaccharide 18. Global deprotection was carried out by transesterifying the acyl groups and hydrogenolysis of the benzyl and Nap ether groups, as described previously.[13] Deprotection was done under microflow conditions and with concomitant reduction of the terminal azide group. Final purification by chromatography on Sephadex LH-20 gave the previously reported α-heptasaccharide 19 as an acetate salt with a 95% yield.[13] NMR data were in agreement with an authentic sample.

Proceeding towards the nonamannoside derivative 21, we followed a straightforward strategy using a [4+5] blockwise assembly.[44] Indeed, coupling the branched pentasaccharide donor 17 to the tetrasaccharide glycosyl acceptor 12 promoted by NIS/TfOH worked equally well and afforded the protected nonasaccharide derivative 20 in 73% isolated yield. Deprotection as described for the heptasaccharide 19 furnished the nonasaccharide 21 in 81% yield. NMR analysis of 21 based on COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, and HMBC measurements confirmed the structural assignments. Signals for the anomeric carbons of the three distal mannopyranosyl residues were observed as overlapping singlets between 102.3–102.2 ppm. The anomeric carbon signals of the two units engaged in the α-(1→3)-linkages at 100.75/100.77 ppm could also not be resolved, whereas the remaining anomeric signals were well separated and individually assigned (for full labeling of the nonasaccharide units see Supporting Information). Glycosylation shifts were observed for carbon 2 of four mannose residues as well as for the fully assigned signals for carbon 3 and carbon 6, respectively, for the four innermost mannose units.

Synthesis of hepta- and nonasaccharides containing the β-linked spacer group

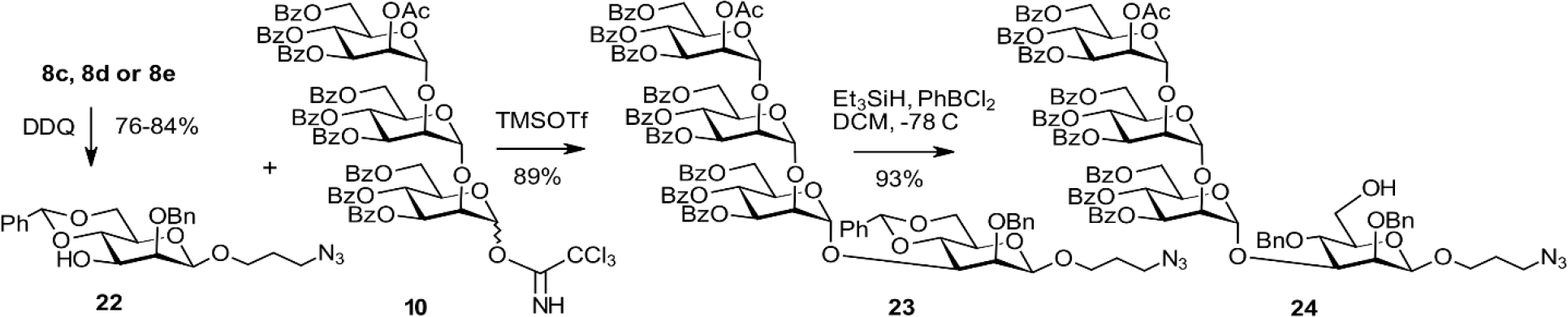

The β-spacer monosaccharide derivatives had been obtained with high stereoselectivity, providing several options for generating the glycosyl acceptor 22. Removal of the 3-O-propargyl group of 8b using KOtBu/OsO4 in the presence of NMMO worked well, but we did not pursue this at a larger scale due to toxicity concerns. Instead, DDQ-oxidation of the Nap and PMB groups of 8c, 8d, and 8e was carried out in good yields, allowing for isolation of the pure β-anomers when using the anomeric mixtures of 8d and 8e, respectively (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the tetrasaccharide acceptor 24

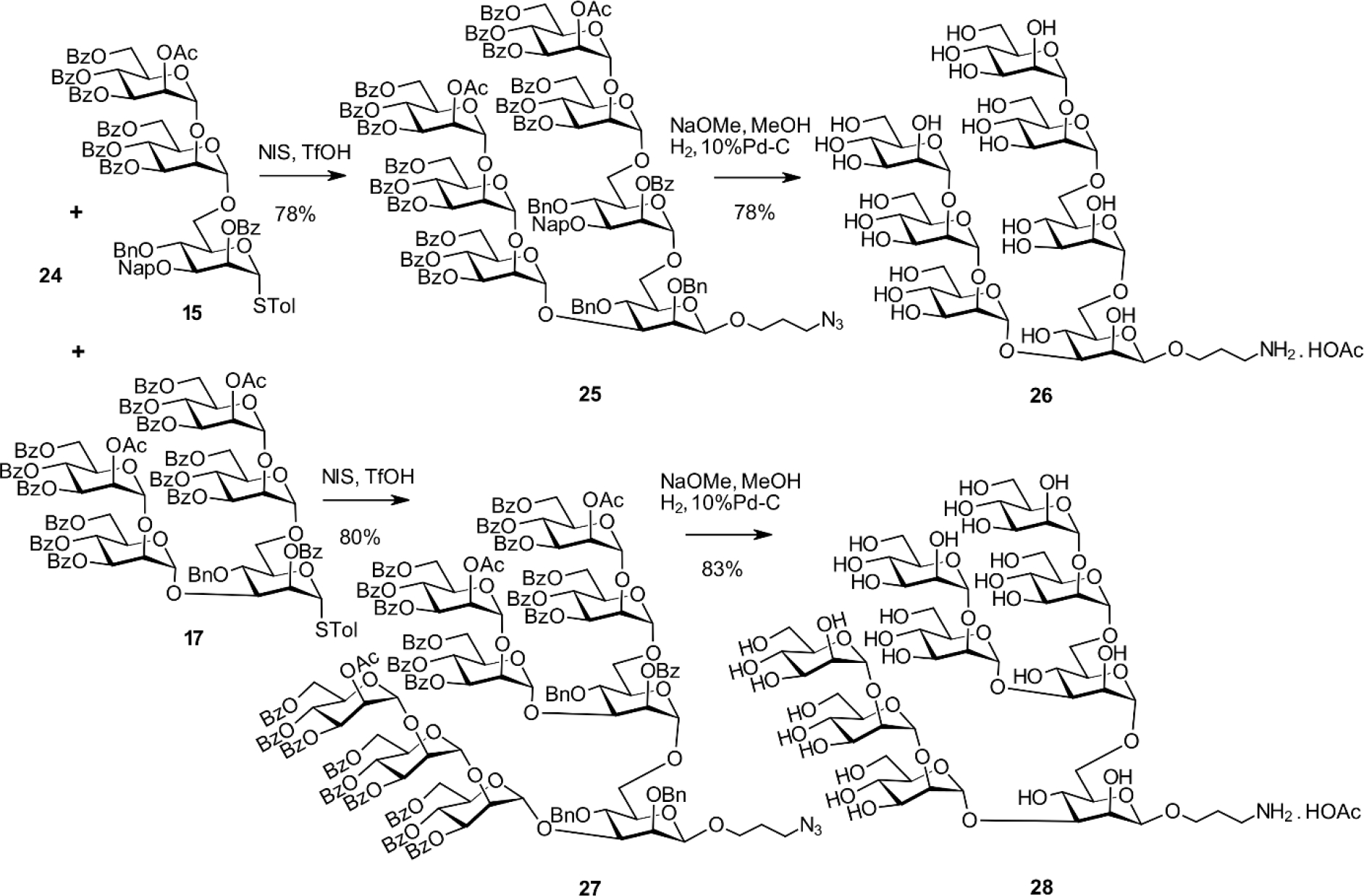

Following the conditions elaborated for the α-spacer derivative, glycosylation of 22 with the trichloroacetimidate donor 10 promoted by TMSOTf proceeded smoothly. This reaction gave the α-(1→3)-linked tetrasaccharide 23. Subsequent regioselective reductive opening of the 4,6-O-benzylidene group afforded the primary alcohol 24. This alcohol was ready for elongation with the trisaccharide and pentasaccharide building blocks 15 and 17. Coupling the thioglycoside donor 15 with 24 in the presence of NIS/TfOH was uneventful and provided the protected heptasaccharide 25 in 78% yield (Scheme 7). Deprotection of 25 and reduction of the terminal azide afforded the previously described[13] heptasaccharide ligand 26 in 78% yield. Similarly, the reaction of 24 with the pentasaccharide donor 17 led to the nonasaccharide derivative 27 in 80% yield followed by processing as described for 26 to afford the nonasaccharide target derivative 28 in 83% yield. The NMR data of 28 were in excellent agreement with the fully assigned signals of Man9GlcNAc2, except for the different reducing end mannosyl residue due to a different chemical environment at the reducing end of the oligomannose glycan.[45] The overall yield in the preparation of the β-spacer heptasaccharide 26 involving five steps calculated from the [3+1] coupling and the subsequent elongation of the tetrasaccharide 23 is 42%. In our previous approach with a late-stage introduction of the spacer group, seven steps were needed that gave an overall yield (again based on the first [3+1] glycosylation) of 8.5%.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of the β-anomeric hepta- and nonamannoside derivatives 26 and 28.

Synthesis of BSA and CRM197 neoglycoconjugates and definition of their antigenicity

For consistency with previously made conjugates,[13] neoglycoconjugates were prepared with an intended loading of 4–6 ligands per protein using optimized reaction conditions (Scheme 8). First, the terminal amino group of the β-anomeric spacer glycosides 26 and 28 were activated by thiophosgenetreatment to obtain intermediate isothiocyanates.[46] This was followed by coupling to the ε-amino groups of lysine residues on bovine serum albumin (BSA) and the diphtheria-derived cross-reactive material CRM197, respectively. The resulting neoglycoconjugates 29–32 were separated from their oligosaccharide ligands by spin filtration and kept as aqueous solutions. MALDI-TOF analysis of the neoglycoconjugates indicated copy numbers of 8.6, 5.6, 3.4 and 1.9 ligands/protein for conjugates 29, 30, 31, and 32, respectively

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of the hepta- and nonamannosyl BSA and CRM197 conjugates 29–32.

The antigenicity of the hepta- and nanomannosyl CRM197 conjugates was determined by ELISA using Fab and IgG versions of the PGT125, PGT126, PGT128, and PGT130 bnAbs. The specificity of these antibodies is fairly well-defined [4,5,47], and we have used these antibodies in the past to characterize neoglycoconjugates.[13,42] We included a CRM197 conjugate prepared according to previous methods[14] and with an average of 2.6 heptamannosyl ligands per CRM197 for comparison (NIT211–6). As shown in Fig. 1, all four Fabs bind greater to the heptasaccharide conjugate 30 (MAC093) than the previously made glycoconjugate. This difference is possibly due to the higher carbohydrate/protein ratio (5.6 ligands/protein) on the current heptasaccharide conjugate compared to the earlier glycoconjugate (2.6 ligands/protein). All four Fabs bound the nonasaccharide conjugate 32 (1.9 ligands/protein) with an apparent affinity similar to the NIT211–6 conjugate. The absence of binding preference by the Fabs for conjugated hepta- or nonamannosyl ligands confirms that these ligands are antigenically equivalent.

Fig. 1.

Binding of Fab fragments of bnAb PGT125, PGT126, PGT128, and PGT130 to the β-heptamannosyl conjugates 30 (MAC093 and NIT211–6) as well as the nonamannosyl conjugate 32 (MAC095). The two β-heptamannosyl and nonamannosyl conjugates were coated as solid-phase antigens onto ELISA plates at 76, 81, and 81 nM concentration.

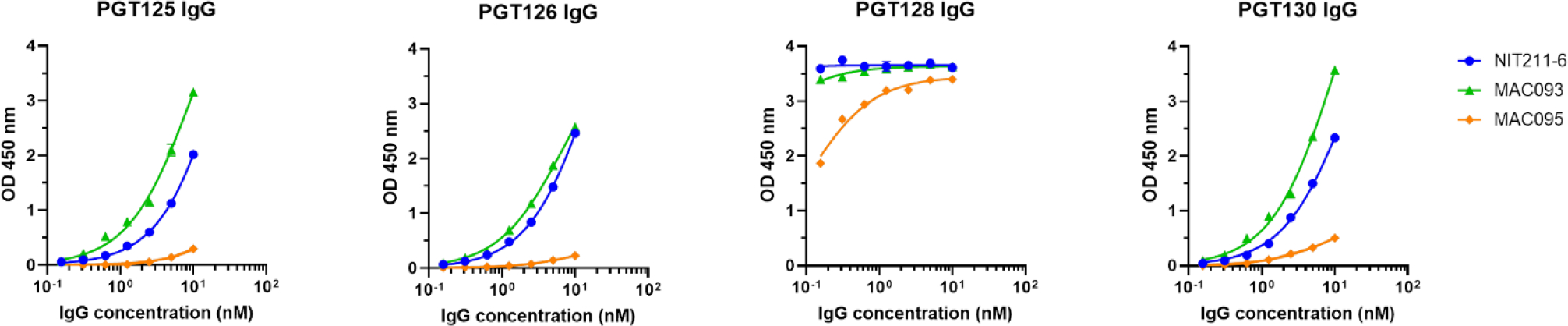

In contrast to the Fabs, a distinct preference in binding for both heptasaccharide conjugates (MAC093, NIT211–6) relative to the nonasaccharide conjugate (MAC095) was observed with IgG versions of the antibodies (Fig. 2). One possible explanation is that the ligands on the nonasaccharide are spaced too far apart to allow bivalent IgG binding; follow-up studies with nonasaccharide conjugates loaded at higher density will help to address this possibility. Another possibility is that the D2 arm in the nonasaccharide, absent in the heptasaccharide, hinders bivalent IgG engagement in the context of the neoglycoconjugate. This possibility agrees with observations from the first studies on the glycan specificity of these PGT antibodies, which showed that they bind poorly to Man9 connected to the relatively rigid chitobiose core;[48] the antibodies bound Man9 only when the ligand was attached to a flexible linker (-(CH2)5-NH-). If correct, then the relatively poor binding of the IgGs to the nonasaccharide conjugate here suggests that the isothiocyanate linker does not afford sufficient flexibility to allow antibody binding to Man9. The observation [5] that the PGT IgGs bind relatively strongly to chitobiose core-conjugated Man8, which has a shortened D2 arm, supports the influential role of the D2 arm.

Fig. 2.

Binding assay of PGT IgG bnAbs to the β-heptamannosyl conjugates 30 (MAC093 and NIT211–6) and the nonamannosyl conjugate 32 (MAC095). The coating concentration of the conjugates is the same as in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

We successfully prepared anomeric 3-azidopropyl mannosides from 4,6-O-benzylidene protected thiocresyl glycosyl donors under Crich conditions. High yields and excellent stereoselectivities were achieved. Depending on the availability of an electron-withdrawing ester group or electron-donating arylalkyl or propargyl group at O-3, the glycosylation reaction with 3-azido-1-propanol afforded the α-glycoside or the β-linked product, respectively. Selective removal of the orthogonal 3-O-protecting group followed by coupling with an α-(1→2)-linked trimannosyl trichloroacetimidate donor gave the respective anomeric tetrasaccharides in high yields. Reductive opening of the benzylidene acetal provided the corresponding primary alcohols for ensuing [4+3] and [4+5] blockwise elongation with thioglycoside donors. Global deprotection afforded the anomeric hepta- and nonamannoside ligands featuring the D1 and D3 arm as a mimetic and the D1, D2, and D3 arms of the native glycan. These ligands were conjugated to BSA and CRM197 carrier proteins. The β-series of the hepta- and nonamannosyl containing CRM197 conjugates were assayed by ELISA using HIV-bnAbs PGT125, PGT16, PGT128, and PGT130. Whereas the binding of all four PGT Fabs was comparable, the binding of the corresponding IgGs was substantially higher for the heptasaccharide than for the nonamannosyl conjugate. These results suggest that synthetic conjugates with a short or missing D2 arm, such as represented by the heptamannosides described here and previously, might serve as better lead immunogens for activating naïve B cells with capacity to produce oligomannose-specific nAbs to HIV-1 in vivo. This notion is consistent with success of our previous glycoconjugates in evoking modest levels of neutralizing antibodies (in transgenic rats) and antibodies that bind native-like HIV glycoproteins following immunization of transgenic mice with human-like antibody repertoire.[13,14] Analogous to immunization strategies with sequential antigens for eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies to other sites on HIV, our efforts contribute to the development of an immunization strategy to shepherd the elicitation of the desired oligomannose-targeting antibodies.

Experimental Section

General Methods.-

All purchased chemicals were used without further purification unless stated otherwise. Solvents were dried over activated 4 Å (CH2Cl2, N,N-dimethylformamide, pyridine) molecular sieves. Dry MeOH (Merck) was purchased. Cation exchange resin DOWEX 50 H+ was regenerated by washing with HCl (3 M), water, and dry MeOH. Aqueous solutions of salts were saturated unless stated otherwise. The concentration of organic solutions was performed under reduced pressure < 40 °C. Optical rotations were measured with an Anton Paar MCP100 polarimeter. [α]D20 values are given in units of 10−1deg cm2g−1. Thin-layer chromatography was performed on Merck precoated plates: 5 × 10 cm, layer thickness 0.25 mm, Silica Gel 60F254; alternatively on HPTLC plates with 2.5 cm concentration zone (Merck). Spots were detected by dipping reagent (anisaldehyde-H2SO4). Silica gel (0.040 – 0.063 mm) was used for column chromatography. HP-column chromatography was performed on pre-packed columns (YMC-Pack SIL-06, 0.005 mm, 250 × 10 mm and 250 × 20 mm). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 600 instrument (600.2 MHz for 1H, 150.9 MHz for 13C) using standard Bruker NMR software. 1H spectra were referenced to δ = 0 using the TMS signal for solutions in CDCl3 and CD2Cl2 and DSS for solutions in D2O (external calibration to 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid). 13C spectra were referenced to 77.00 (CDCl3), 54.00 (CD2Cl2) and 67.40 (D2O, external calibration to 1,4-dioxane) ppm. Assignments were based on COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and TOCSY spectra. ESI-MS data were obtained on a Waters Micromass Q-TOF Ultima Global instrument. MALDI data were obtained on a Bruker Autoflex MALDI TOF/TOF instrument using 2,5-dihydroxy acetophenone as the matrix. Synthetic procedures are described in the Supporting Information.

Neoglycoconjugate 29:

A solution of thiophosgene (8 μL, 0.11 mmol) in CHCl3 (1.5 mL) was added to a solution of 26 (2.0 mg, 0.002 mmol) in 0.1 M aqueous NaHCO3 (1.0 mL), and the solution was vigorously stirred for 4 h at rt. The organic phase was removed, and the aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 2 mL). Traces of CHCl3 were removed by bubbling air through the solution until a clear phase was obtained. Next, a solution of BSA (2 mg, 0.3 μmol) in 0.3 M NaCl / 0.1 M NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was added and the solution was stirred for 72 h at rt. The reaction mixture was centrifuged and subjected to spin filtration (Amicon 0.5 M, 30 kDa) for 10 min (14000 × g). The filtered compound was dissolved in pure water to obtain a 1 mg/mL solution of the desired conjugate. MALDI-TOF data of 29 showed an average copy number of ~8.6 ligands per BSA.

Neoglycoconjugate 30:

A solution of 26 (3.5 mg, 0.003 mmol) in 0.1 M aqueous NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was activated with a solution of thiophosgene (11 μL, 0.15 mmol) in CHCl3 (0.5 mL) and processed as described for 29. Then a solution of CRM197 (2.5 mg, 0.43 μmol) in 0.3 M NaCl / 0.1 M NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was added, stirred for 72 h at rt, and processed as described above. A 1 mg/mL solution of the desired conjugate was obtained by dissolving the spin-filtered compound in pure water. MALDI-TOF data of 30 showed a ligand density of ~5.6 ligands/protein.

Neoglycoconjugate 31:

A solution of 28 (3.0 mg, 0.002 mmol) in 0.1 M aqueous NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was activated with a solution of thiophosgene (9 μL, 0.12 mmol) in CHCl3 (1.0 mL) and processed as described for 29. Then a solution of BSA (2.0 mg, 0.34 μmol) in 0.3 M NaCl / 0.1 M NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was added, stirred for 72 h at rt and processed as described above. The spin-filtered compound was dissolved in pure water, yielding a 1 mg/mL solution of the desired conjugate. MALDI-TOF data of 31 showed a ligand density of ~3.4 ligands/protein.

Neoglycoconjugate 32:

A solution of 28 (3.2 mg, 0.002 mmol) in 0.1 M aqueous NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was activated with a solution of thiophosgene (9 μL, 0.15 mmol) in CHCl3 (0.5 mL) and processed as described for 29. Then a solution of CRM197 (2.0 mg, 0.34 μmol) in 0.3 M NaCl / 0.1 M NaHCO3 (0.5 mL) was added, stirred for 72 h at rt and processed as described above. The spin-filtered compound was dissolved in pure water, yielding a 1 mg/mL solution of the desired conjugate. MALDI-TOF data of 32 showed a ligand density of ~1.9 ligands/protein.

Recombinant antibody expression and purification

PGT125, PGT126, PGT128 and PGT130 Fabs were expressed in 293S (ATCC) or FreeStyle 293F cells (Life Technologies) grown in suspension. The cells were transfected at a 1:1 ratio of plasmids encoding the respective antibodies’ light and heavy chains (truncated at AspH234). Supernatants were harvested six days after transfection, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Antibody was purified from the clarified supernatant using an anti-human lambda affinity matrix (CaptureSelect LC-lambda (hu); Thermo Scientific) equilibrated in PBS. Fab fragments were eluted with 0.1 M glycine, pH 3, and the eluate neutralized with concentrated PBS. Recombinant IgGs were expressed in FreeStyle 293F cells and purified on a protein A resin (Thermo Scientific) as described elsewhere.[13]

ELISA

ELISAs were performed as described previously.[14] Briefly, neoglycoconjugates were absorbed onto 96-well polystyrene ELISA plates (Corning) at 5 μg/mL in PBS overnight at 4°C. After washing, the plates were blocked with PBS supplemented with 3% (w/v) BSA (PBS-B). Antibodies serially diluted in PBS supplemented with 1% (w/v) and 0.02% (v/v) Tween-20 (PBS-BT) were then added. After washing, bound Fab was detected with biotin anti-IgG-CH1 conjugate (Thermo Scientific) and IgG with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch). 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (Ultra TMB, Thermo Scientific) was used as the substrate for assay development.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of α-anomeric hepta- and nonasaccharide spacer derivatives 19 and 21.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AI134299 (to RP). The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Alexandra Arezina for technical support, Shi Yan and Jorick van Beselaere for recording MALDI and Thomas Grasi for measuring HRMS spectra.

References

- [1].Gray GE, Laher F, Doherty T, Abdool Karim S, Hammer S, Mascola J, Beyrer C, Corey L, L. PLoS Biology 2016, 14, e1002372 (DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002372). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Corey L, Gray GE and Buchbinder SP, J Int AIDS Soc 2019, 22, e25289 (DOI: 10.1002/jia2.25289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Walker LM, Simek MD, Priddy F, Gach JS, Wagner D, Zwick MB, Phogat SK, Burton DR, PLoS Pathog 2010, 6, e1001028 (DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001028); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jacob RA, Moyo T, Schomaker M, Abrahams F, Pujola BG, Dorfman JR, J. Virol. 2015, 89, 5264–5275; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ditse Z, Muenchhoff M, Adland E, Joosteg P, Goulder P, Moore PL, Morris L, J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00878 (DOI: 10.1128/jvi.00878-18); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tomaras GD, Binley JM, Gray ES, Crooks ET, Osawa K, Moore PL, Tumba N, Tong T, Shen X, Yates NL, Decker J, Wibmer CK, Gao F, Alam SM, Easterbrook P, Karim SA, Kamanga G, Crump JA, Cohen M, Shaw GM, Mascola JR, Haynes BF, Montefiori DC, Morris L, J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11502–11519; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Landais E, Huang X, Havenar-Daughton C, Murrell B, Price MA, Wickramasinghe L, Ramos A, Bian CB, Simek M, Allen S, Karita E, Kilembe W, Lakhi S, Inambao M, Kamali A, Sanders EJ, Anzala O, Edward V, Bekker L-G, Tang J, Gilmour J, Kosakovsky-Pond SL, Phung P, Wrin T, Crotty S, Godzik A, Poignard P. PLOS Path. 2016, 12, e 1005369 (DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005369); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Moore PL, Gray ES, Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Nonyane M, Sheward DJ, Hermanus T, Bajimaya S, Tumba NL, Abrahams M-R, Lambson BE, Ranchobe N, Ping L, Ngandu N, Karim QA, Karim SA, Swanstrom RI, Seaman MS, Williamson C, Morris L, Nat Med 2012, 18, 1688–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Doores KJ, Kong L, Krumm SA, Le KM, Sok D, Laserson U, Garces F, Poignard P, Wilson IA, Burton DR, J. Virol. 2015, 89, 1105–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien J-P, Wang S-K, Ramos A, Chan-Hui P-Y, Moyle M, Mitcham JL, Hammond PW, Olsen OA, Phung P, Fling S, Wong C-H, Phogat S, Wrin T, Simek MD, Koff WC, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P, Nature 2011, 477, 466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Astronomo RD, Lee H-K, Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Huang C-Y, Wilson IA, Blixt O, Dwek RA, Wong C-H, Burton DR, J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6359–6368; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Joyce JG, Krauss IJ, Song HC, Opalka DW, Grimm KM, Nahas DD, Esser MT, Hrin R, Feng M, Dudkin VY, Chastain M, Shiver JW, Danishefsky SJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2008, 105, 15684–15689; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li H, Wang LX, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 483–488; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kabanova A, Adamo R, Proietti D, Berti F, Tontini M, Rappuoli R, Costantino P, Glycoconj. J. 2010, 27, 501–513; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ni J, Song H, Wang Y, Stamatos NM, Wang L-X, Bioconjugate Chem. 2006, 17, 493–500; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhang H, Fu H, Luallen RJ, Liu B, Lee F-H, Doms RW and Geng Y, Vaccine 2015, 33, 5140–5147; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Astronomo RD, Kaltgrad E, Udit AK, Wang SK, Doores KJ, Huang CY, Pantophlet R, Paulson JC, Wong CH, Finn MG, Burton DR, Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 357–370; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Cai H, Orwenyo J, Giddens JP, Yang Q, Zhang R, LaBranche CC, Montefiori DC, Wang L-X, Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 1513–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Seabright GE, Doores KJ, Burton DR, Crispin M, J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2223–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Porwoll S, Fuchs H, Tauber R, FEBS Lett 1999, 449, 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nguyen DN, Redman RL, Horiya S, Bailey JK, Xu B, Stanfield RL, Temme JS, LaBranche CC, Wang S, Rodal AA, Montefiori DC, Wilson IA, Krauss IJ, ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 789–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bruxelle J-F, Kirilenko T, Qureshi Q, Lu N, Trattnig N, Kosma P, Pantophlet R, Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7582 (DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-64500-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shivatare SS, Cheng T-JR, Cheng Y-Y, Shivatare VS, Tsai T-I, Chuang H-Y, Wu C-Y, Wong C-H, ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 2016–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Clark BE, Auyeung K, Fregolino E, Parrilli M, Lanzetta R, De Castro C, Pantophlet R, Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pantophlet R, Trattnig N, Murrell S, Lu N, Chau D, Rempel C, Wilson IA, Kosma P, Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1601 (DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-01640-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bruxelle J-F, Kirilenko T, Trattnig N, Yang Y, Cattin M, Kosma P, Pantophlet R, Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4637 (DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-84116-w). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Giannini G, Rappuoli R, Ratti G, Nucleic Acids Res 1984, 12, 4063–4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saunders KO, Nicely NI, Wiehe K, Bonsignori M, Meyerhoff RR, Parks R, Walkowicz WE, Aussedat B, Wu NR, Cai F, Vohra Y, Park PK, Eaton A, Go EP, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Barouch DH, Zhang R, Holle TV, Overman RG, Anasti K, Sanders RW, Moody MA, Kepler TB, Korber B, Desaire H, Santra S, Letvin NL, Nabel GJ, Montefiori DC, Tomaras GD, Liao H-X, Alam SM, Danishefsky SJ, Haynes BF, Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2175–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trattnig N, Mayrhofer P, Kunert R, Mach L, Pantophlet R, Kosma P, Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].(a) For recent reviews seeCrich D, Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1144–1153; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sasaki K, Tohda K, Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 496–503. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dudkin VY, Miller JS, Danishefsky SJ, Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 1791–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 20].Abdel-Rahman AA-H, Jonke S, El Ashry ESH, Schmidt RR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2971–2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].(a) Ito Y, Ogawa T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1994, 33, 1765–1767; [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishiwata A, Munemura Y, Ito Eur Y. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 4250–4263; [Google Scholar]; (c) Barresi F, Hindsgaul O, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9376–9377. [Google Scholar]

- [22].(a) Lei J-C, Ruan Y-X, Luo S, Yang J-S, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 6377–6382; [Google Scholar]; (b) Pistorio SG, Yasomanee JP, Demchenko AV, Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].(a) Ratner DM, Plante OJ, Seeberger PH, Eur. J.Org. Chem. 2002, 826–833; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kunz H, Günther W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1988, 27, 1086–1087; [Google Scholar]; (c) David S, Malleron A, Dini C, Carbohydr. Res. 1989, 188, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nguyen H, Zhu D, Li X and Zhu J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4767–4771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tanaka M, Nashida J, Takahashi D, Toshima K, Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2288–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Boltje TJ, Li C, Boons GJ, Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4636–4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Patil PS, Lee C-C, Huang Y-W, Zulueta MML, Hung S-C, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2605–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mong K-KT, Shiau K-S, Lin YH, Cheng K-C, Lin C-H, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 11550–11560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Crich D, Jayalath P, Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 2277–2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cendret V, François-Heude M, Méndez-Ardoy A, Moreau V, Fernández JMG, Djedaini-Pilard F, Chem. Commun, 2012, 48, 3733–3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Crich D, Wu B, Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4879–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Crich D, Wu B, Jayalath P, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6806–6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Crich D, Jayalath P, Hutton TK, J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3064–3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou J, Lv S, Zhang D, Xia F, Hu W, J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2599–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gucchait A, Shit P, Misra AK, Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131412 (DOI: 10.1039/c9ob00670b). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Crich D, Sharma I, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 8383–8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Crich D, Picard S, J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9576–9579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Crich D, Cai W, Dai Z, J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 1291–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bock K, Pedersen C, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 2, 1974, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schmidt RR, Michel J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1980, 19, 731–732. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Meng B, Wang J, Wang Q, Serianni AS, Pan Q, Carbohydr. Res. 2017, 73, 3932–3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Trattnig N, Blaukopf M, Bruxelle J-F, Pantophlet R, Kosma P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7946–7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].(a) Zhu Y, Kong F, F. Synth. Comm. 2002, 32, 1219–1226; [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma Z, Zhang J, Kong F, Carbohydr. Res. 2004, 339, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].(a) Ramos-Soriano J, de la Fuente MC, de la Cruz N, Figueiredo RC, Rojo J, Reina JJ, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 8877–8882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang L, Chan TH, Can. J. Chem. 2005, 83, 693–701; [Google Scholar]; (c) Grice P, Ley SV, Pietruszka J, Osborn HMI, Priepke HWM, Warriner SL, Chem. Eur. J. 1997, 3, 431–440; [Google Scholar]; (d) Meng B, Wang J, Wang Q, Serianni AS, Pan Q, Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 3032–3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shahzad-ul-Hussan S, Sastry M, Lemmin T, Soto C, Loesge S, Scott DA, Davison JR, Lohith K, O’Connor R, Kwong PD, Bewley CA, ChemBioChem. 2017, 18, 764–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Smith DF, Ginsburg V, J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, Depetris R, Katpally U, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Maloveste S, Liu Y, McBride R, Ito Y, Sanders RW, Ogohara C, Paulson JC, Feizi T, Scanlan CN, Wong CH, Moore JP, Olson WC, Ward AB, Poignard P, Schief WR, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Science 2011, 334, 1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Barry CS, Cocinero EJ, Çarçabal P, Gamblin DP, Stanca-Kaposta EC, Remmert SM, Fernández-Alonso MC, Rudić S, Simons JP, Davis BG, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16895–16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.