Abstract

Background

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are commonly observed during pre-participation cardiac screening in elite athletes. There is an ongoing debate about the clinical significance of PVCs in athletes and whether burden, morphology, or both should be used to differentiate benign PVCs from PVCs suggestive of cardiac disease.

Case summary

A 28-year-old male athlete was evaluated as part of the pre-participation screening programme. He was asymptomatic, without specific cardiac signs and symptoms. A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed bigeminy PVCs with infundibular morphology and left ventricular outflow tract origin. Left ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction without valvular lesions was detected on echocardiography. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed biventricular dilatation and dysfunction without evidence of myocardial fibrosis or fatty infiltration. A 48 h Holter monitoring showed 75191 PVCs (35% of total beats). Radiofrequency ablation was performed, and post-ablation assessments showed no PVCs with normalized ventricular function and dimension.

Discussion

This case demonstrated that a high PVC burden of common morphology does not also represent a benign finding and requires a comprehensive evaluation to rule out any pathological condition. Furthermore, the present case highlights the critical role of pre-participation cardiac evaluation in identifying cardiac disease in asymptomatic athletes.

Keywords: PVC-induced cardiomyopathy, Premature ventricular contractions, Pre-participation cardiac evaluation, Case report, Ablation

Learning points.

The burden of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) remains an important feature as a high burden might carry the risk of PVC-induced cardiomyopathy and may require treatment even in asymptomatic athletes.

A high PVC burden of ‘benign’ morphology does not necessarily represent a benign finding, and a comprehensive cardiac assessment is required to detect underlying heart disease.

The present case highlights the significant role of electrocardiogram-based cardiac screening in the identification of asymptomatic athletes at risk of sudden cardiac death.

Introduction

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) seen on an athlete’s electrocardiogram (ECG) could indicate an increased risk of fatal arrhythmia during exercise.1 Premature ventricular contraction characteristics such as burden and morphology are essential criteria for risk stratification of PVCs in athletes.2,3 Recent studies have suggested that the morphology of PVCs may be the key feature rather than the frequency.2 However, there is a debate regarding the clinical outcome of PVCs in athletes and which features of PVCs should be utilized to differentiate benign PVCs from PVCs suggestive of cardiac disease, which may predispose to sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Timeline

| Time | Description |

|---|---|

| May 2019 |

|

| June 2019 |

|

| July 2019 |

|

| September 2019 |

|

| October 2019 |

|

Case summary

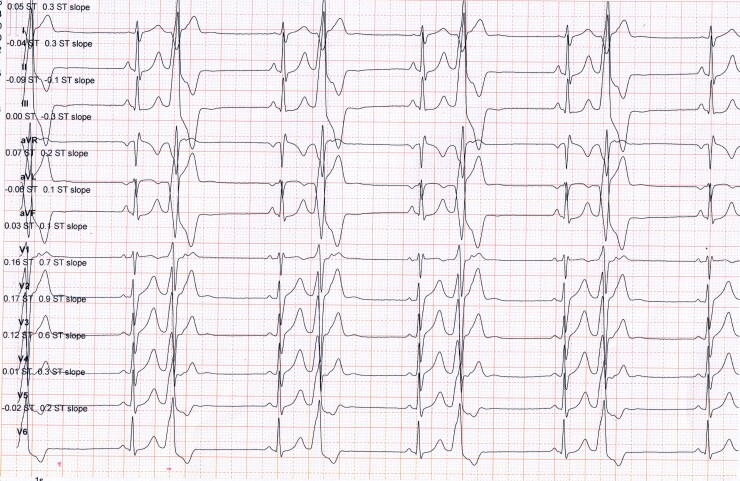

A 28-year-old elite CrossFit male Persian athlete was referred by his coach to undergo the pre-participation screening prior to the competition. For the last 6 months, he trained for ∼16 h/week divided into 6 bouts of high-intensity CrossFit (a high-static and low-dynamic components activity, Class IIIA). He was asymptomatic, without cardiac signs and symptoms such as palpitation, chest pain, and shortness of breath at rest, but stated that his exercise tolerance had recently declined. His past medical history was unremarkable. There was no history of SCD in close relatives, and the family history was negative for underlying cardiac disease. He denied using anabolic steroids, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, or using recreational drugs. Physical examination demonstrated a regular heart rhythm of 42 beats per minute with a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. On auscultation, he had normal heart sounds with no additional murmurs. There were no abnormal lung sounds and no peripheral oedema. A 12-lead ECG revealed frequent PVCs in a bigeminy pattern (Figure 1). Premature ventricular contractions displayed left bundle branch block and inferior QRS axis morphology (also referred to as an infundibular pattern), with small R-waves in V1 and an early QRS transition before V3, indicating a left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) ectopic focus. The athlete was referred for a 48 h Holter monitoring and was mandated to keep exercising throughout ambulatory monitoring. Holter monitoring showed an absolute number of 75191 PVCs (a total burden of 35% of the total monitored beats) mostly in a monomorphic ventricular bigeminy pattern. Sporadic episodes of ventricular couplets were seen, and no sustained or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) was detected. During the exercise, the morphology of the PVCs did not change, and no NSVT or couplets were identified. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed markedly increased left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic diameters (63 mm), which was higher than the accepted normal limits (≤54 mm),4 with moderate-to-severe global systolic dysfunction, (LV ejection fraction was 35%). There was no regional wall motion abnormality, and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion was within normal limits (17 ≤ mm).5 Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging showed biventricular dilatation [LV end-diastolic volume was 232 mL and right ventricular (RV) end-diastolic volume was 225 mL] and moderate-to-severe dysfunction (LV and RV ejection fraction were 34% and 41%, respectively) (Supplementary material online, Video S1). Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) diameter in parasternal long-axis was 25 mm, which was within normal limits (20–30 mm),5 and there was no evidence of myocardial fibrosis or fatty infiltration (Supplementary material online, Video S2). There was no evidence of endocrine disorder on a comprehensive blood test in terms of endocrine hormonal screenings.

Figure 1.

The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram of a 28-year-old male asymptomatic CrossFit athlete shows bigeminy premature ventricular contractions with an infundibular pattern, characterized by a typical left bundle branch block, inferior ORS axis morphology with small R-waves in V1, and earlier QRS transition before V3, indicative of an left ventricular outflow tract ectopic focus. PVCs, premature ventricular contractions; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract.

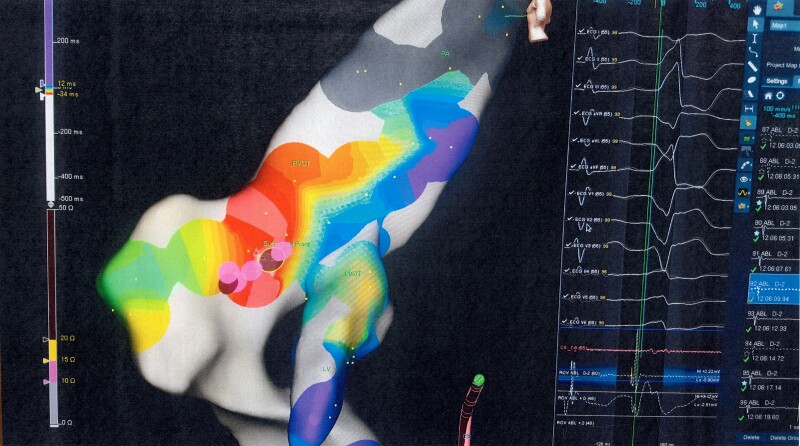

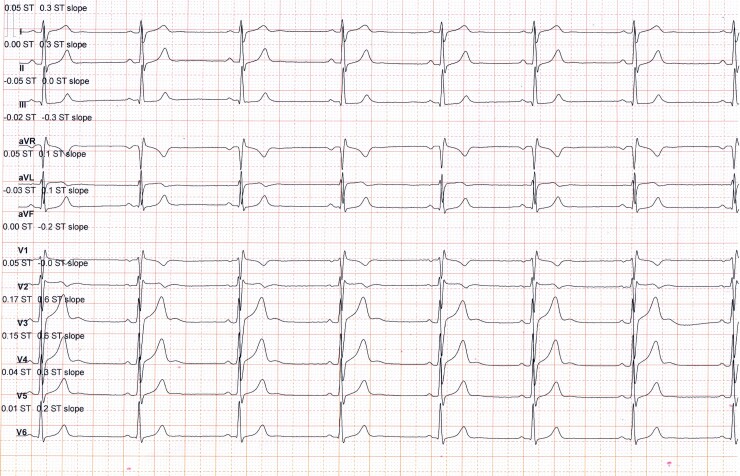

The athlete was advised against competitive sports activities and directly referred for an electrophysiological study with a view to proceeding with radiofrequency ablation (RFA). An electrophysiological study confirmed the origin of the PVCs seen on surface 12-lead ECG (Figure 2). Electroanatomical mapping confirmed the absence of a scar. After localizing the origin of PVCs by activation sequence mapping and pace mapping approach, targeted ablation of the region was performed. Post-ablation 12-lead ECG showed sinus rhythm without PVCs (Figure 3). No PVCs were detected in the 48 h Holter monitor at 1 and 3 months after ablation. Echocardiography and CMR, 1 and 3 months after ablation showed that the function and dimensions of the LV and RV gradually returned to the accepted normal limits (≤54 mm)4 (Table 1). The athlete resumed competitive sports activities 4 months after the ablation.

Figure 2.

3D mapping by Navx confirmed the left ventricular outflow tract origin of premature ventricular contractions. LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; PVCs, premature ventricular contractions.

Figure 3.

Post-ablation 12-lead electrocardiogram shows sinus rhythm without premature ventricular contraction. PVCs, premature ventricular contractions.

Table 1.

Parameters before and after the radiofrequency ablation

| Before RFA | 1 month after RFA | 3 months after RFA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PVCs by 48 h Holter monitoring | 75 191 | 0 | 0 |

| Burden of PVCs by 48 h Holter monitoring (%) | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| LVEF (%) by echocardiogram | 35 | 45 | 60 |

| LVFS (%) by echocardiogram | 25 | 32 | 39 |

| LVEDD (mm) by echocardiogram | 63 | 56 | 53 |

| LVESD (mm) by echocardiogram | 43 | 42 | 32 |

| RVEDD (mm) by echocardiogram | 25 | 23 | 20 |

| LVEF (%) by CMR | 34 | 43 | 57 |

| RVEF (%) by CMR | 41 | 52 | 58 |

| LVEDV (mL) by CMR | 232 | 185 | 162 |

| LVESV (mL) by CMR | 152 | 85 | 62 |

| RVEDV (mL) by CMR | 225 | 215 | 205 |

| RVESV (mL) by CMR | 130 | 108 | 98 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fraction shortening; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameters, LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic diameters; RVEDD, right ventricular end-diastolic diameters; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; RVEDV, right ventricular end-diastolic volume; RVESV, right ventricular end-systolic volume.

Discussion

In this case, we observed that a PVC burden of 35% with an infundibular pattern in an athlete without structural cardiac disease is associated with the development of the PVC-induced cardiomyopathy (PICM), which was characterized by LV and RV dilatation and dysfunction. Although Pelliccia et al.4 reported that a small proportion of highly trained athletes have a significant LV dilatation, it is important to note that all of those athletes participated in endurance sports disciplines.. Therefore, LV dilatation, in this case, may not be attributed to physiological adaptation to sports with high-static and low-dynamic components, such as CrossFit. Furthermore, an LV end-diastolic diameter ≥60 mm combined with an LV ejection fraction ≤45% should raise suspicion of dilated cardiomyopathy. Moreover, it has been suggested that prolonged and intense exercise may also cause arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) in the absence of gene mutations, known as exercise-induced ACM.6 However, based on the ACM task force criteria 2010,7 we rule out the possibility of exercise-induced ACM in this case. Despite RV dilatation and dysfunction, there was no evidence of myocardial fibrosis on CMR, and RVOT size was normal. In addition, the LV is typically involved in advanced cases of ACM, where disease manifestations such as palpitations and syncope are expected; however, the present case was asymptomatic; therefore, LV dysfunction that was observed in this case may be attributed to exercise-induced ACM. Furthermore, there was also no evidence of ECG abnormalities, such as deep negative T-waves and epsilon wave in the right precordial leads, which are electrical signs of ACM.

The possible mechanism for explaining idiopathic PVCs in athletes is assumed to be either bradycardia- or tachycardia-induced.8 However, in this case, PVCs were more likely to be tachycardia-induced because the athlete had sinus bradycardia after ablation, and no PVCs were detected on post-ablation ECG. A shift from parasympathetic to sympathetic predominance as a result of an intensive exercise training may have predisposed the athlete to electrical instability.9 Furthermore, the possible impact of the hormonal alteration (especially cortisol and adrenaline) induced by prolonged and intensive training on myocardial irritability should be considered.9

Management strategies in athletes with frequent PVCs include detraining, pharmacotherapy, and ablation. In this case, a high PVC burden caused LV dysfunction, so we performed RFA in accordance with the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology, which was successful in eliminating the arrhythmia and reversing the LV dysfunction.10 There is conflicting evidence regarding the effects of detraining on PVC frequency reduction.11,12 Moreover, elite athletes with bradycardia experience minimal efficacy from pharmacotherapy, and frequent PVCs might be resistant to anti-arrhythmic medications.13

The significance of PVCs is highly variable and depends on their characteristics, including frequency and morphology.3 Baman et al.14 demonstrated that a frequency of 10 000 PVCs over 24 h or a PVCs burden of 24% suffices to cause PICM. Furthermore, Biffi et al.15 showed that a higher frequency of PVCs (>2000/24 h) should raise suspicion of structural cardiac disease. Recently, more focus has been placed on the morphological pattern of PVCs, and it has been suggested that PVCs with a common pattern (infundibular or fascicular) in the absence of underlying heart disease (idiopathic PVCs) have been thought to be relatively benign.3 In this regard, Pelliccia et al.2 reported that cardiac diseases were detected in 1% and 12% of athletes with common and uncommon (other morphologies and/or multifocal or repetitive) patterns, respectively. However, this case indicates that a high PVC burden of common morphology does not also represent a benign finding and requires further evaluation to rule out a pathological condition.

Conclusion

This case suggested that the burden of PVCs remains an important feature for risk stratification in athletes, as a high burden might carry the risk of PICM and may require treatment even in asymptomatic athletes. This case demonstrates that a high PVC burden of benign morphology does not represent a benign finding, and a comprehensive cardiac assessment is required to detect underlying heart disease. The present case highlights the important role of pre-participation cardiac screening even in asymptomatic athletes.

Lead author biography

Dr Javad Norouzi is a cardiovascular exercise physiologist and member of the Sports Cardiology Department of the National Olympic Committee of Iran with expertise in the cardiac assessment of athletes. During his PhD at the University of Tehran/Iran, he completed a training course in sports cardiology at the Institution of Sports Medicine and Science of the National Committee of Italy under the direct supervision of Prof. Antonio Pelliccia. He is the director of the Oxygen Sports Cardiology Center. His research focuses on developing innovative strategies for preventing and predicting cardiac disease in elite athletes and young people.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal—Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Mont L, Pelliccia A, Sharma S, Biffi A, Borjesson M, Terradellas JB, Carré F, Guasch E, Heidbuchel H, Gerche AL, Lampert R, McKenna W, Papadakis M, Priori SG, Scanavacca M, Thompson P, Sticherling C, Viskin S, Wilson M, Corrado D, ESC Scientific Document Group . Pre-participation cardiovascular evaluation for athletic participants to prevent sudden death: position paper from the EHRA and the EACPR, branches of the ESC. Endorsed by APHRS, HRS, and SOLAECE. Europace 2017;19:139–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pelliccia A, De Martino L, Borrazzo C, Serdoz A, Lemme E, Zorzi A, Corrado D. Clinical correlates and outcome of the patterns of premature ventricular beats in Olympic athletes: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrado D, Drezner JA, D’Ascenzi F, Zorzi A. How to evaluate premature ventricular beats in the athlete: critical review and proposal of a diagnostic algorithm. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1142–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pelliccia A, Culasso F, Di Paolo FM, Maron BJ. Physiologic left ventricular cavity dilatation in elite athletes. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D’Ascenzi F, Pisicchio C, Caselli S, Di Paolo FM, Spataro A, Pelliccia A. RV remodeling in Olympic athletes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. La Gerche A, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, Inder WJ, Taylor AJ, Bogaert J, MacIsaac AI, Heidbüchel H, Prior DL. Exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction and structural remodelling in endurance athletes. Eur Heart J 2012;33:998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MGPJ, Daubert JP, Fontaine G, Gear K, Hauer R, Nava A, Picard MH, Protonotarios N, Saffitz JE, Sanborn DMY, Steinberg JS, Tandri H, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Tsatsopoulou A, Wichter T, Zareba W. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Circulation 2010;121:1533–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. He W, Lu Z, Bao M, Yu L, He B, Zhang Y, Hu X, Cui B, Huang B, Jiang H. Autonomic involvement in idiopathic premature ventricular contractions. Clin Res Cardiol 2013;102:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iellamo F, Legramante JM, Pigozzi F, Spataro A, Norbiato G, Lucini D, Pagani M. Conversion from vagal to sympathetic predominance with strenuous training in high-performance world class athletes. Circulation 2002;105:2719–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding Christian, Van Veldhuisen Dirk J., et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J 2015;36:2793–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biffi A, Maron BJ, Culasso F, Verdile L, Fernando F, Di Giacinto B, Di Paolo FM, Spataro A, Delise P, Pelliccia A. Patterns of ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with training, deconditioning and retraining in elite athletes without cardiovascular abnormalities. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delise P, Lanari E, Sitta N, Centa M, Allocca G, Biffi A. Influence of training on the number and complexity of frequent VPBs in healthy athletes. J Cardiovasc Med 2011;12:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Penela D, Fernández-Armenta J, Aguinaga L, Tercedor L, Ordoñez A, Bisbal F, Acosta J, Rossi L, Borras R, Doltra A, Ortiz-Pérez JT, Bosch X, Perea RJ, Prat-González S, Soto-Iglesias D, Tolosana JM, Vassanelli F, Cabrera M, Linhart M, Martinez M, Mont L, Berruezo A. Clinical recognition of pure premature ventricular complex-induced cardiomyopathy at presentation. Hear Rhythm 2017;14:1864–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baman TS, Lange DC, Ilg KJ, Gupta SK, Liu TY, Alguire C, Armstrong W, Good E, Chugh A, Jongnarangsin K, Pelosi F, Crawford T, Ebinger M, Oral H, Morady F, Bogun F. Relationship between burden of premature ventricular complexes and left ventricular function. Hear Rhythm 2010;7:865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Biffi A, Pelliccia A, Verdile L, Fernando F, Spataro A, Caselli S, Santini M, Maron BJ. Long-term clinical significance of frequent and complex ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.