Abstract

The effects of microcystins on Daphnia galeata, a typical filter-feeding grazer in eutrophic lakes, were investigated. To do this, the microcystin-producing wild-type strain Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806 was compared with a mcy− PCC7806 mutant, which could not synthesize any variant of microcystin due to mutation of a microcystin synthetase gene. The wild-type strain was found to be poisonous to D. galeata, whereas the mcy− mutant did not have any lethal effect on the animals. Both variants of PCC7806 were able to reduce the Daphnia ingestion rate. Our results suggest that microcystins are the most likely cause of the daphnid poisoning observed when wild-type strain PCC7806 is fed to the animals, but these toxins are not responsible for inhibition of the ingestion process.

Several species of cyanobacteria, including the bloom-forming freshwater species Microcystis aeruginosa, are able to produce several variants of microcystin, the most common cyanotoxin, which has been implicated in livestock poisoning and human poisoning (4, 5, 23). Recently, it was shown that these small cyclic peptides are synthesized nonribosomally by peptide synthetases (8). Numerous studies have been carried out in order to determine the ecological significance of the microcystins. The results obtained, however, are inconsistent (11).

One possible function of microcystins is that they play a role in the defense of M. aeruginosa cells against zooplankton grazing. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that exposure to Microcystis cells reduces the life span of daphnids (3, 10, 13, 18, 24). However, the problem seems to be more complex. The data of Jungmann (13) and Jungmann and Benndorf (14), for example, suggested that an unidentified metabolite of Microcystis sp. rather than microcystins was responsible for toxicity to Daphnia. Moreover, Nizan et al. (24) found no correlation between acute toxicity of various M. aeruginosa strains to daphnids and their quantitative microcystin contents. In other cases, daphnids could feed on microcystin-containing M. aeruginosa without suffering any harmful effects (22).

Experiments on Microcystis toxicity have usually been performed by comparing strains which differ in microcystin content. However, other strain-specific properties could be the source of the striking variation in the results obtained in different investigations. For example, M. aeruginosa strains differ in their content of potential toxic oligopeptides (25), which could strengthen or mask a toxic effect of microcystins. Also strain-specific differences in ingestibility of M. aeruginosa cells by daphnids may influence the dose of an endotoxin, which is determined by the ingestion rate (amount of food taken in per time unit) and by the toxin content of the cells. Indeed, the ingestion rate of daphnids depends to a large extent on the M. aeruginosa strain offered as food. Some strains affect the ingestion rate of the animals, whereas others do not (10, 12, 15, 18, 19). Some authors (12, 19) have hypothesized that a perceptible factor (“bad taste”) is responsible for this effect. However, the possibility that microcystins themselves are involved in the inhibition of ingestion cannot be ruled out.

The experiments described in this paper were designed to study the role of microcystins in the effect of M. aeruginosa on Daphnia galeata; both Microcystis toxicity and strain-dependent inhibition of ingestion were studied. To do this, we compared an M. aeruginosa PCC7806 mutant which was genetically engineered to knock out the production of microcystins with the microcystin-synthesizing wild-type strain. The two variants of strain PCC7806 used have the same genotype except that the mutant (mcy−) cells have an insertional mutation in a microcystin synthetase gene (8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description and origins of the cyanobacterial strains used.

The unicellular strain M. aeruginosa PCC7806 (from Braakman Reservoir, The Netherlands) was provided by J. Weckesser (Albert-Ludwigs-University, Freiburg, Germany). This strain contains mainly microcystin MCYST-LR, (d-Asp3)MCYST-LR (7), and cyanopeptolin depsipeptides (21). The derived mutant cell line (mcy−) which was used in this study was obtained by performing homologous recombination. A peptide synthetase gene (mcyB), which occurs only in microcystin-producing Microcystis strains, was insertionally inactivated with a chloramphenicol resistance cartridge. Cells of the mutant cell line lacked microsystins but not cyanopeptolins (8). The unicellular organism M. aeruginosa HUB 5-3, which was used as a reference strain in the ingestion rate analyses, was originally isolated from a water bloom on Lake Pehlitzsee (Brandenburg, Germany) in 1978. Extensive analyses of the interactions of this strain with daphnids showed that it did not have any adverse or harmful effects (12). In contrast to wild-type strain PCC7806, M. aeruginosa HUB 5-3 lacked microcystins. On the other hand, strains HUB 5-3 and PCC7806 (including the mutant cell line of PCC7806) did not differ significantly in cell diameter or cell ultrastructure (as determined by electron microscopic analyses performed by W. Bleiß and A. Marko, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany).

Culturing of cyanobacterial strains and D. galeata.

The different M. aeruginosa strains were cultured semicontinuously by using a synthetic medium as described previously (26). All of the cultures used in the experiments grew in the logarithmic phase under a light regime consisting of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness at 20°C. The densities of the Microcystis suspensions were measured by using a photometric diaphragm method (16). For 14C-labelling, a NaH14CO3 solution (0.18 MBq per 50 ml) was added to the M. aeruginosa cultures, and then the cultures were incubated for 3 days. Before the ingestion rate experiments were started, the Microcystis cells were washed by centrifugation at 1,500 × g.

The D. galeata culture used was descended from a laboratory clone culture (Humboldt University). The animals were raised on Chlorella cf. minutissima cells suspended in filtered (pore size, 0.2 μm; membraPure) lake water. The temperature was adjusted to 20°C. Only adult females having similar body lengths were used in this study. Before the experiments were started, the test animals were washed carefully with filtered lake water to remove all Chlorella cells.

DNA isolation and PCR.

Genomic DNA of M. aeruginosa PCC7806 was isolated as described previously (9). A PCR was performed by using Goldstar thermostable DNA polymerase (Eurogentec) and primers Tox2p (5′GGAACAAGTTGCACAGAATCCGC3′) and Tox2m (5′CCAATCCCTATCTAACACAGTAACTCGG3′). The PCR procedure was initiated by a denaturation step (2 min, 95°C), which was followed by 30 cycles consisting of 20 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C and by a final elongation step (5 min, 72°C).

Determination of ingestion rates.

Ingestion rates were determined by using a standard radioisotope technique and 14C-labelled Microcystis cells (12). Up to 20 daphnids were placed into 210-ml incubation vessels filled with filtered (pore size, 0.2 μm; membraPure) lake water containing the desired cyanobacteria at a concentration of 20 mm3 liter−1 (incipient limiting level of D. galeata, 4 mm3 liter−1). The temperature was adjusted to 20°C. After a 50-min adaptation period, 14C-labelled M. aeruginosa cells were added at a ratio of 1:10 to the unlabelled cyanobacteria. After 15 min of feeding the animals were washed with filtered lake water and anesthetized with carbonated water. Then the body lengths were measured as a biovolume-related parameter (1). All of the animals in an incubation vessel were transferred together into a scintillation vial before a tissue solubilizer was added. The radioactivities of the Microcystis suspensions and the test animals were determined with a liquid scintillation analyzer (Tri-Carb; Packard). The whole experiment was repeated seven times (wild-type and mutant PCC7806) or nine times (HUB 5-3). The ingestion rates were calculated by determining the biovolume of cyanobacteria ingested (cubic millimeters) per biovolume of Daphnia (cubic millimeters) per day. To test whether the Microcystis cultures were able to affect the ingestion rate, the microcystin-producing wild type and the nonproducing mcy− mutant of strain PCC7806 were compared with the easily ingestible standard strain HUB 5-3, which did not have any inhibitory or toxic effects on Daphnia in previous studies (12).

Life table experiments.

Survival tests were carried out in 100-ml Plexiglas tubes that could be closed at both ends with gauze. These tubes were placed into 1.0-liter glass bottles that were completely filled with filtered (pore size, 0.2 μm; membraPure) lake water containing the desired cyanobacteria at a density of 20 mm3 liter−1. The temperature was adjusted to 20°C. Ten daphnids were transferred into each tube. The suspensions were shaken moderately. Living animals were counted and then transferred into freshly prepared M. aeruginosa suspensions every 24 h. In this way wild type strain PCC7806 and the strain PCC7806 mutant were tested and compared to a nonfood control (filtered lake water alone). For both strain variants (wild type and mutant) the whole procedure was repeated four times. The experiments were terminated after 5 days.

Statistical analyses.

To compare the means of the ingestion rates obtained, Student’s t test at the 99% level of significance was used. The microcystin toxicity experiments resulted in survival functions, which were, as usual, compared with the log rank test. For the M. aeruginosa cultures which were poisonous to D. galeata, the time needed to kill 50% of the animals was calculated as median of the Kaplan-Meier survival function estimation.

RESULTS

Characterization of the mcy− mutant.

As cyanobacteria are known to contain several genome copies (2) and even apparently homozygous mutant clones may contain a few wild-type copies, it was necessary to maintain the mutant under selective pressure with chloramphenicol. Therefore, the homozygous genotype of the mutant was proven before the experiments performed to study feeding and survival of D. galeata were started without chloramphenicol in the medium. The presence of the chloramphenicol resistance cartridge was checked by using primers that bound upstream and downstream of the insertion region. No wild-type gene copy was detected in the mutant cell line investigated (8). In addition, the microcystin contents of the wild type and mutant were monitored by high-performance liquid chromatography during the experiments described below (data not shown). The lack of any microcystin in the mcy− mutant was evident over the whole period studied.

Ingestion rate experiments.

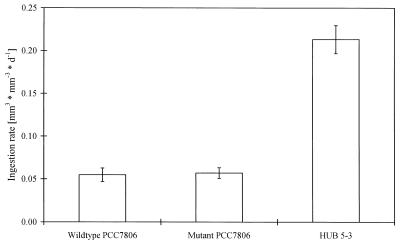

Wild-type PCC7806 was ingested by D. galeata at a very low rate (Fig. 1); the ingestion rate was 75% less than the ingestion rate of HUB 5-3. In contrast, no significant difference was found between the ingestion rates of the wild type and the mcy− mutant. Both variants of PCC7806 were ingested by D. galeata at nearly the same low rate.

FIG. 1.

Ingestion rates of the strains investigated (means ± standard errors; n = 7 for wild-type PCC7806 and the mcy− mutant of PCC7806; n = 9 for HUB 5-3). d, day.

Life table experiments.

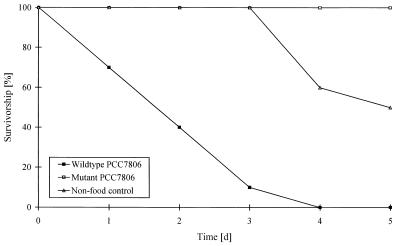

Life table experiments were carried out to study the toxicity of the variants of PCC7806 investigated to D. galeata. An M. aeruginosa culture was considered toxic if the animals died faster than they died due to starvation. Therefore, both variants of PCC7806, the wild type and the mcy− mutant, were compared four times to nonfood controls. Figure 2 shows the results of a typical experiment. The results obtained in the replicate experiments were always comparable.

FIG. 2.

Survival of D. galeata in suspensions containing wild-type PCC7806, the mcy− mutant of PCC7806, and the nonfood control (results of one of the four replicate experiments). d, day.

In all cases wild-type of M. aeruginosa strain PCC7806 was toxic to Daphnia. Thus, the survival functions observed in experiments performed with the wild type always differed significantly from the survival functions of the nonfood controls (P < 0.001, as determined by the log rank test). The time needed to kill 50% of the animals varied from 1.2 to 2.0 days. In striking contrast, no animals died in the experiments performed with the mcy− mutant of PCC7806. Consequently, the survival functions of this variant differed significantly from those of the nonfood controls (P < 0.025) and those of wild-type M. aeruginosa strain PCC7806 (P < 0.001).

Interestingly, the animals exposed to wild-type strain PCC7806 exhibited a significant change in their swimming behavior. Approximately 5 h after they were transferred into the suspensions containing the wild-type strain, the swimming activity of the animals decreased and the animals stayed at the bottoms of the vessels. In contrast, the daphnids fed the mcy− mutant exhibited the normal swimming behavior.

DISCUSSION

The results of the life table experiments performed with the original wild-type strain PCC7806 demonstrate that cells of this strain are able to poison D. galeata and cause the death of the animals in a comparably short time. Therefore, it is evident that there is a toxic compound in the cells. Wild-type M. aeruginosa PCC7806 synthesizes relatively large amounts of two microcystin variants, which are known to be potential inhibitors of Daphnia protein phosphatases 1 and 2A (6). Inhibition of these enzymes by microcystins plays an important role in poisoning of warm-blooded animals (20), which supports the idea that microcystins are the toxins which cause the death of daphnids. However, there has been no unequivocal evidence which supports this hypothesis until now (11). The availability of the mcy− mutant of PCC7806 made it possible to analyze more precisely the role of microcystins in Daphnia poisoning by comparing two clones of M. aeruginosa which have identical genotypes except for a specific mutation in a microcystin synthetase gene which leads to the inability of mcy− cells to synthesize microcystins (8).

While the animals fed with microcystin-containing wild-type strain PCC7806 died quickly, the Daphnia sp. remained alive when the mcy− mutant was offered as food. Therefore, we concluded that the microcystins were the most probable cause of Daphnia poisoning when wild-type strain PCC7806 was fed to the animals. In addition, the toxins may also have caused the significant reduction in Daphnia swimming activity observed some hours after the animals were transferred into the suspension containing wild-type strain PCC7806. Overall, we concluded that microcystins may be formed in order to eliminate zooplankton species, which feed on Microcystis spp., as previously suggested (18). The data reported here also indicates that the cyanopeptolin depsipeptides found in both the wild type and the mcy− mutant of PCC7806 are not responsible for the daphnid poisoning observed.

Another effect of M. aeruginosa PCC7806 on D. galeata was the inhibition of the ingestion process. Compared to the easily ingestible strain HUB 5-3, the ingestion rate of the animals was 75% lower when they were fed wild-type strain PCC7806. Interestingly, in spite of the absence of all microcystin variants, the mcy− mutant of PCC7806 was ingested by Daphnia at the same low rate as the microcystin-containing wild-type strain. Thus, there was no relationship between the presence of microcystins in the cells and the inhibition of ingestion. This means that the poisoning of Daphnia and the inhibition of ingestion are caused by different Microcystis factors.

In conclusion, our data indicates that microcystins are the cause of the toxic effects of M. aeruginosa on daphnids, whereas these compounds are not responsible for ingestion inhibition. Furthermore, our results support the hypothesis that one function of microcystins could be to eliminate grazers of Microcystis spp.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to Marion Dewender for her analyses of microcystins, as well as for her excellent laboratory assistance.

This study was supported by grant BMBF 0339547 from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and by a grant from the Fazit Foundation to J.-G.K. and T.R., respectively, and by a grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG) to T.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balushkina E W, Winberg G G. Relation between length and body weight of plankton crustacean. In: Winberg G G, editor. Biological base in lake productivity determination. Leningrad, USSR: Zoological Institute Press; 1979. pp. 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry B A, Boerner R J, de Paula J C. The use of cyanobacteria in the study of the structure and function of photosystem II. In: Bryant D A, editor. The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 217–257. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benndorf J, Henning M. Daphnia and toxic blooms of Microcystis aeruginosa in Bautzen reservoir (GDR) Int Rev Gesamten Hydrobiol. 1989;74:233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmichael W W. Cyanobacteria secondary metabolites—the cyanotoxins. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:445–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codd G A. Cyanobacterial toxins: occurrence, properties and biological significance. Water Sci Technol. 1995;32:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMott W R, Dhawale S. Inhibition of in vitro protein phosphatase activity in three zooplankton species by microcystin-LR, a toxin from cyanobacteria. Arch Hydrobiol. 1995;134:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dierstein R, Kaiser I, Weckesser J, Matern U, König W A, Krebber R. Two closely related peptide toxins in axenically grown Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittmann E, Neilan B A, Erhard M, von Döhren H, Börner T. Insertional mutagenesis of a petide synthetase gene that is responsible for hepatotoxin production in the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:779–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6131982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franche C, Damerval T. Tests on nif probes and DNA hybridizations. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:803–808. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulton R S, III, Paerl H W. Toxic and inhibitory effects of the blue-green alga Microcystis aeruginosa on herbivorous zooplankton. J Plankton Res. 1987;9:837–855. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanazato T. Toxic cyanobacteria and the zooplankton community. In: Watanabe M F, Harada K, Carmicheal W W, Fujiki H, editors. Toxic Mycrocystis. New York, N.Y: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henning M, Hertel H, Wall H, Kohl J-G. Strain-specific influence of Microcystis aeruginosa on food ingestion and assimilation of some cladocerans and copepods. Int Rev Gesamten Hydrobiol. 1991;76:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jungmann D. Toxic compounds isolated from PCC7806 that are more active to Daphnia than two microcystins. Limnol Oceanogr. 1992;37:1777–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jungmann D, Benndorf J. Toxicity to Daphnia of a compound extracted from laboratory and natural Microcystis spp., and the role of microcystins. Freshwater Biol. 1994;32:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jungmann D, Henning M, Jüttner F. Are the same compounds in Microcystis responsible for toxicity to Daphnia and inhibition of its filtering rate? Int Rev Gesamten Hydrobiol. 1991;76:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohl J-G, Nicklisch A. Ökophysiologie der Algen. Berlin, Germany: Akademie-Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampert W. Inhibitory and toxic effects of blue-green algae on Daphnia. Int Rev Gesamten Hydrobiol. 1981;66:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampert W. Further studies on the inhibitory effect of the toxic blue-green Microcystis aeruginosa on the filtering rate of zooplankton. Arch Hydrobiol. 1982;95:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKintosh C, Beattie K A, Klump S, Cohen P, Codd G A. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1990;244:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin C, Oberer L, Ino T, König W A, Busch M, Weckesser J. Cyanopeptolins, new depsipeptides derived from the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1550–1556. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matveev V, Matveeva L, Jonez G J. Study of the ability of Daphnia carinata King to control phytoplankton and resist cyanobacterial toxicity: implications for biomanipulation in Australia. Aust J Mar Freshwater Res. 1994;45:889–904. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore R E. Cyclic peptides and depsipeptides from cyanobacteria: a review. J Ind Microbiol. 1996;16:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01570074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nizan S, Dimentman C, Shilo M. Acute toxic effects of cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa on Daphnia magna. Limnol Oceanogr. 1986;31:497–502. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weckesser J, Martin C, Jakobi C. Cyanopeptolins, depsipeptides from cyanobacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zehnder A, Gorham P R. Factors influencing the growth of Microcystis aeruginosa Kütz. emend. Elenkin. Can J Microbiol. 1960;6:645–660. doi: 10.1139/m60-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]