Abstract

Aim and objective

To assess the systematic reviews and meta-analyses investigating the dental caries experience in children with cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P).

Study design and methodology

A systematic search was carried out from MEDLINE Via PubMed, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, EMBASE, OVID, Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, and Epistemonikos databases. Two independent reviewers carried out the collection and analysis of the study data. Methodological quality was assessed by ROBIS (Risk of bias assessment in systematic review) tool.

Review results

An initial search of electronic databases yielded a total of 25 relevant reviews, of which only three systematic reviews were taken into consideration for qualitative synthesis. The total number of unique primary studies among the three included systematic reviews were 25, of which overlap of the studies was calculated using citation matrix. The corrected covered area (CCA) was estimated to be 0.26. Based on the ROBIS tool, only one systematic review reported with low risk of bias.

Conclusion

Individuals with CL/P report more decayed, missing, or filled teeth/surfaces than those without CL/P in primary, mixed, and permanent dentition. Future studies should focus on the factors which could modify the caries risk of an individual with CL/P.

Clinical significance

This umbrella review offers a more reliable and balanced view regarding the dental caries experience among individuals with cleft lip and/or palate. This paper also highlights the important role of pediatric dentist in multidisciplinary health care team in implementing first dental visit and anticipatory guidance to consider early diagnosis and specific preventive interventions for Early Childhood Caries (ECC) in individuals with CL/P.

How to cite this article

Abirami S, Panchanadikar NT, Muthu MS, et al. Dental Caries Experience among Children and Adolescents with Cleft Lip and/or Palate: An Umbrella Review. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2022;15(S-2):S261-S268.

Keywords: Children and adolescents, Cleft lip and/or palate, Dental caries, Umbrella review

Introduction

The most common craniofacial condition is cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P), affecting 500-1,000 live births worldwide. The highest incidence rate among Asian populations was between 0.82 and 4.04 per 1,000 live births.1 Birth prevalence rates of CL/P follow distinct ethnic distribution patterns.2 Early childhood caries (ECC) is a serious public health problem and still possess a big challenge to oral health for children with CL/Pt.3 Early detection should therefore be an important aspect of the multidisciplinary management of CL/P patients needing healthy dentition for good oral function and orthodontic care.4–6

Studies reported that—CL/P patients have compromised oral hygiene, which is attributed to the fear of toothbrushing, limited access in the cleft area, scarring of the oral tissues, followed by surgical repair, crowding in the dentition, and prolonged oral clearance by the action of saliva and the tongue.6–8 Hasslöf P and Twetmen S systemically assessed the case control studies and found that—there are no variations in the prevalence of caries between CL/P and control patients, and a further systematic review by Antonarakis GS et al., found increased prevalence rate for dental caries in patients with CL/P.9 A recent meta-analysis published by Worth V et al., concluded that the occurrence of dental caries in both the primary and permanent dentition was significantly higher in children with clefts than in children without cleft.10 The discrepancies observed in different studies may be due to abundant factors such as the multifactorial existence of dental caries, methodological variations, limited sample sizes, various age groups, severity of cleft type, inclusion of syndromes, cultural differences, and incidence levels with inhomogeneous study designs. In conflict with the results and the numbers of systematic reviews in this field illustrate the need for an umbrella review, which would combine the results of the available systematic reviews to arrive at a conclusion.11–13 Therefore, the aim of this umbrella review was to systematically assess the reviews and meta-analyses investigating the dental caries experience in children with CL/P. It is anticipated that this umbrella review will be significant in defining the degree of adequacy in the methodological quality and reporting of systematic reviews.

Materials and Methods

This study protocol was registered and accepted in International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 15th October 2019 (PROSPERO Registration ID-CRD 420,201 50,656).

Selection Criteria

Systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses that assessed the incidence and prevalence of dental caries under the age group of 18 were included. No time restriction was applied, and all the published systematic reviews carried out up to October 2019 were taken into consideration. Due to the limitations of available resources, searches were limited to English. Caries experience was measured by change in the baseline value in any form of dental caries indices, including number of decayed, missing, and filled permanent teeth/surfaces (DMFT/S), and decayed, missed, and filled primary teeth/surfaces (dmft/s) and International Caries Detection and Assessment System, World Health Organization, Pulpal Involvement, Ulcerations, Fistula, and Abscess were used for study outcomes measures.

Exclusion Criteria

In this umbrella study, no attention was given to primary research, narrative reviews conference proceedings, and letters to editors and reviews which did not adopt the methodological approach for conducting the systematic reviews.

Search Strategy

The identification of included studies was completed in November 2019, from the following database, MEDLINE Via PubMed, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, EMBASE, OVID, Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, and Epistemonikos. Three groups of keywords were applied:1 population/condition: CL/P, craniofacial disorder, children, adolescents;2 types of studies, that is, systematic reviews, meta-analyses; and3 types of outcome measures, that is, dental caries, ECC. Search strategy used in MEDLINE is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

MEDLINE via PubMed search strategy

| Set | Search terms |

|---|---|

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 NOT # 5 |

| #5 | (“addresses” [Publication Type] OR “biography” [Publication Type] OR “case reports” [Publication Type] OR “comment” [Publication Type] OR “directory” [Publication Type] OR “editorial” [Publication Type] OR “festschrift” [Publication Type] OR “interview” [Publication Type] OR “lectures” [Publication Type] OR “legal cases” [Publication Type] OR “legislation” [Publication Type] OR “letter” [Publication Type] OR “news” [Publication Type] OR “newspaper article” [Publication Type] OR “patient education handout” [Publication Type] OR “popular works” [Publication Type] OR “congresses” [Publication Type] OR “consensus development conference” [Publication Type] OR “consensus development conference, nih” [Publication Type] OR “practice guideline” [Publication Type]) |

| #4 | ((systematic review [Title/Abstract]) OR (meta-analysis [Title/Abstract])) |

| #3 | (((children [Title/Abstract]) OR (child [Title/Abstract])) OR (adolescents [Title/Abstract]))) |

| #2 | (((((((“dental caries”[Title/Abstract]) OR (caries [Title/Abstract])) OR (tooth decay [Title/Abstract])) OR (nursing bottle caries[Title/Abstract])) OR (early childhood caries[Title/Abstract])) OR (dental caries[MeSH Terms])) OR (decayed, missing, and filled teeth[MeSH Terms]))) |

| #1 | ((((((((((((cleft lips*[Title/Abstract]) OR (cleft palate*[Title/Abstract])) OR (cleft lip/palate [Title/Abstract])) OR (craniofacial deformity [Title/Abstract])) OR (oro-facial clefts [Title/Abstract])) OR (cleft lip[MeSH Terms])) OR (cleft palates[MeSH Terms])) OR (cleft lip[MeSH Terms])) OR (cleft palate[MeSH Terms])) OR (craniofacial abnormalities[MeSH Terms])) |

Note: Filters: systematic review and meta-analysis and English.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

An initial search of electronic databases yielded 25 relevant reviews. The publications were retrieved from the searches, combined into one database, and duplicates were removed. Independent screening of the titles and abstracts was done by two trained authors (AS and NP). Full texts articles were assessed independently by two authors (AS and NP) and in duplicates to assess potentially eligibility of the study for inclusion. Where there were discrepancies, a third investigator (MSM) was consulted. The reference lists of all included studies were then evaluated. In total, three reviews were considered eligible for this umbrella review. To mitigate the bias, two reviewers (AS and NP) collected data from the selected reviews. The data collected for this review includes—the number of primary studies included in the reviews, number of participants of the included studies eligible for the current umbrella review, and age ranges of study populations, outcome indicators, as well as their overall performance, drawbacks, and recommendations. Table 2 shows the overlap of the systematic reviews in the present study, citation matrices were created and “corrected covered areas” (CCA) were calculated.17

Table 2.

Citation matrix and corrected covered area

| S. no. | Primary studies | Overlapping of primary studies in included systematic review | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hasslof P and Twetman S, 2007 | Antonarakis GS et al., 2013 | Worth V et al., 2017 | ||

| 1. | Al-Wahandni A et al., 2005 | X | X | X |

| 2. | Boukhout B et al., 1996 | X | X | |

| 3. | Dahllof G et al., 1989 | X | X | |

| 4. | Hewson AR et al., 2001 | X | X | |

| 5. | Lausterstein AM and Mendelsohn M, 1963 | X | X | |

| 6.. | Lucas JR et al., 2000 | X | X | |

| 7. | Al Dajani M, 2009 | X | X | |

| 8. | Fretias AB et al., 2012 | X | X | |

| 9. | Hazza AM et al., 2011 | X | X | |

| 10. | King NM et al., 2012 | X | X | |

| 11. | Lucas JR et al., 2000 | X | X | |

| 12. | Mutari T et al., 2008 | X | X | |

| 13. | Pisek A et al., 2014 | X | ||

| 14. | Chopra A et al., 2014 | X | ||

| 15. | Kirchberg A et al., 2013 | X | ||

| 16. | Tannure PN et al., 2012 | X | ||

| 17. | Rawashdeh MA et al., 2011 | X | ||

| 18. | Britton KF et al., 2010 | X | ||

| 19. | Zhu WC et al., 2010 | X | ||

| 20. | Parapanisiou V et al., 2009 | X | ||

| 21. | Ahulwalia M et al., 2004 | X | ||

| 22. | Kirchberg A et al., 2004 | X | ||

| 23. | Budai M et al., 2001 | X | ||

| 24. | Houchstein U and Houchstein HJ, 1970 | X | ||

| 25. | Bethmann W et al., 1967 | X | ||

Corrected covered area (CCA) calculated by:

CCA = N-r

rc-r

N = Number of included publication (Sum of X); r = Rows (index publication); c = Columns (included reviews)

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The ROBIS (“Risk of Bias Evaluation in Systematic Reviews”) tool was used for assessing the methodological quality of the included systematic reviews.14–16 Each review was scored in three phases: assessment of relevance—Phase 1 (optional); identification of concerns with the review process—Phase 2 with four domains (study eligibility criteria, identification and selection of studies, data collection and study appraisal, and synthesis and findings); and judgment of risk of bias—Phase 3. Signaling questions from each domain were answered appropriately (Y = Yes, PY = Probably Yes, PN = Probably No, N = No, NI = No Information) in Phases 2 and 3 to define clear concerns about potential bias in the analysis. Review authors (AS, NP, and MSM) had completed both Cochrane systematic review protocol development and completion workshop conducted by Cochrane South Asia, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India. During the protocol completion workshop, review authors were trained for ROBIS tool assessment. All three reviewers (AS, NP, and MSM) had completed online certified course on “Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis” by John Hopkins University (Coursera Inc.) and attended an online training webinar on ROBIS tool presented by the University of Bristol. The third investigator (MSM) has been trained to perform systematic reviews since 2012. The risk of bias for the individual studies rated by two reviewers (AS and NP) as low/unclear/high. Disagreements between the reviewers over individual domains were established and resolved during a consensus meeting with the assistance of an experienced reviewer. (MSM) Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews

| S. No. | Context | Author/year | Hasslof P and Twetman S, 2007 | Antonarakis GS et al., 2013 | Worth V et al., 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Study Details | Objectives | To find evidence of increased dental caries prevalence in children with cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P)† | To determine the prevalence of caries in non-syndromic patients with cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P) relative to a non-CL/P matched population | To assess whether children born with an orofacial cleft are at greater risk of dental caries than non-cleft individuals. |

| Participants (characteristics) | CL/P Children0-16 years | Nonsyndromic cleft patients: 1.5-25 years | Nonsyndromic CL/P (any age, gender, socioeconomic status or geographical location) | ||

| Setting/context | Caries prevalence expressed as DMFT/S‡ dmft/s§ index in both primary and permanent dentition | Caries prevalence in CL/P at any given timepoint in comparison with matched noncleft control group | Caries prevalence expressed as DMFT/S‡ dmft/s§ index in primary, mixed, and permanent dentition | ||

| Description of interventions | NA¶ | NA¶ | NA¶ | ||

| Phenomena of interest | CL/P with age and sex-matched control | CL/P with sex-matched control | Comparison group of any size including national data was appropriate | ||

| 2. | Search details | Source. searched | PubMed database conducted through May, 2006 | PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web od Science, CINAHL, Cochrane Library | MEDLINE, EMBASE, OVID, Cochrane library, Proquest, CINAHL, HMIC, PsychINFO, and Google scholar |

| Range (years) of included studies | 1963-2005 | 2000-2012 | 1964-2017 | ||

| Number of studies included | 6 | 7 | 24 | ||

| Types of studies included | Case control studies (age and sex matched) | Case control studies (sex matched)—cross-sectional | Case control study | ||

| Country of origin of included studies | Jordan, Sweden, Holland, England, USA, and Ireland | Syria, Thailand, Jordan, Hong Kong, UK, and Brazil | Europe, Asia, South America, and North America | ||

| 3. | Appraisal | Appraisal instruments used | Healthcare assessment by Swedish council | Agbaje et al., 2012 | Agbaje et al., 2012 |

| Appraisal rating | Evidence levelA—highB—moderateC—low | 0-4 poor quality, 5-8 medium quality, 9-12 good quality | 0-4 poor quality, 5-8 medium quality, 9-12 good quality, | ||

| 4. | Analysis | Method of analysis | Difference in the incidence of caries between cases and controls | Mean differenceCL/P with matched control Meta-analysis performed using random effects model. | Mean difference CL/P compared matched control. Random effect multianalysis using Dersimonian and Liard estimator |

| Outcome assessed | Primary caries prevalence—N% of dmft/s§ | Mean percentage difference of DMFT/S§, dmft/s‡ | Mean percentage difference of DMFT/S§, dmft/s‡ | ||

| Results/findings | Mean percentageCL/P—41%Noncleft—7% | Mean percentage DMFT/S‡—1.38 % dmft/s§ 1.51% | Mean difference—CL/P primary dentition 0.63%Mixed dentition 0.28%Permanent dentition 1.72% | ||

| Significance/direction | No firm evidence that children with CL/P exhibit more caries than noncleft children (evidence level 4) | Study reported in the individual studies—not transparent | Sensitivity analysis using conservative estimate of SD AND Publication bias in both DMFT/S‡ /dmft/s DMFT/S‡ is higher among CL/P patients. | ||

| Heterogeneity | NA¶ | Visual (confidence interval) and statistical (ƛ2 test, tau2 and calculation of I2 − substantial heterogeneity | Substantial heterogeneity Dmft/s§—80.9% and I2 statistics—70.1% |

CL/P—cleft lip and/or palate

DMFT/S—decayed, missed, filled teeth or surface in permanent dentition

Dmft/s—decayed, missed, filled teeth or surface in primary dentition

Not applicable

Results

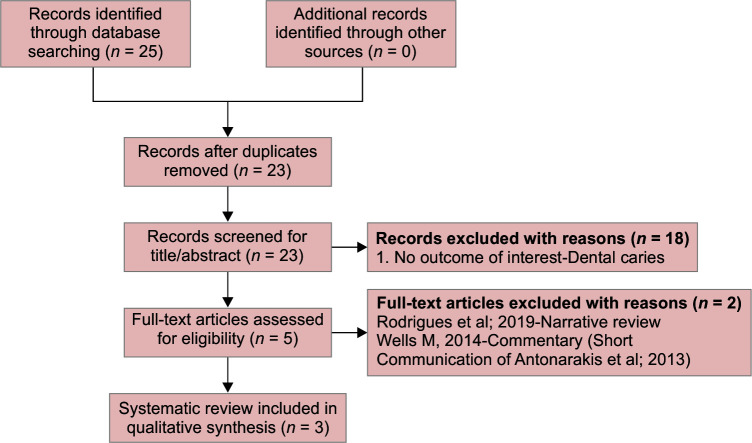

An initial analysis of the electronic database provided a total of 25 systematic reviews, five of which were considered eligible for full-text screening. Of the five, two reviews were excluded. Rodrigues R et al., presented a narrative review, where the outcome measures were not directly related to dental caries.11 Another review by Wells M got excluded because it is a commentary on one of the included systematic reviews.12 Finally, three studies were included for the qualitative synthesis of this umbrella review. The total number of unique primary studies included was 25, of which one study was included three times, 11 studies were included two times, and 13 studies were included once in the systematic review included. Thus, CCA was estimated to be 0.26. Flowchart 1 shows the flowchart of identification and selection of systematic review with the reason for exclusion at each stage.

Flowchart 1.

Identification and selection of systematic reviews, with reasons for exclusion at every stage

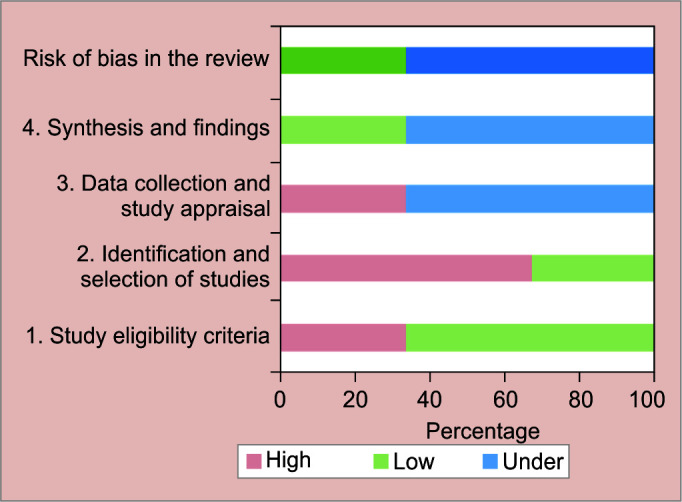

Among the three included systematic reviews, the most recent study by Worth V et al. was published in 2017.10 For the included studies, the ages of the patients ranged from birth to 25 years. Table 4 presents the total risk of bias of eligible studies considering each domain of phase 2 from the ROBIS tool.14 Two of the three included systematic reviews suggested unclear risk of bias. Figure 1 represents the summary of ROBIS assessments across three included reviews (each domain rating which is mentioned as lighter color: pink—high risk of bias, blue—unclear risk of bias, and green—low risk of bias and overall rating for the risk of bias was mentioned as darker shade of the same color. Dark pink—high risk of bias, dark green—low risk of bias, and dark blue—unclear risk of bias). This graph was generated with the help of ROBIS excel spread sheet from the Bristol university online resources.

Table 4.

Assessment of risk of bias of systematic review using ROBIS tool

| S. No. | Study ID | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study eligibility criteria | Identification andselection of studies | Data collection andstudy appraisal | Synthesis andfindings | Risk of bias inthe review | ||

| 1. | Hasslöf P and Twetman S, 20078 | High ☹ | High ☹ | Unclear? | Unclear? | Unclear? |

| 2. | Antonarakis GS et al., 20139 | Low ☺ | Low ☺ | Unclear? | Unclear? | Unclear? |

| 3. | Worth V et al., 201710 | Low ☺ | High ☹ | High ☹ | Low ☺ | Low ☺ |

☹ = High Risk of Bias ? = Unclear Risk of Bias ☺ =Low Risk of Bias

Fig. 1.

Summary of concerns from the ROBIS tool

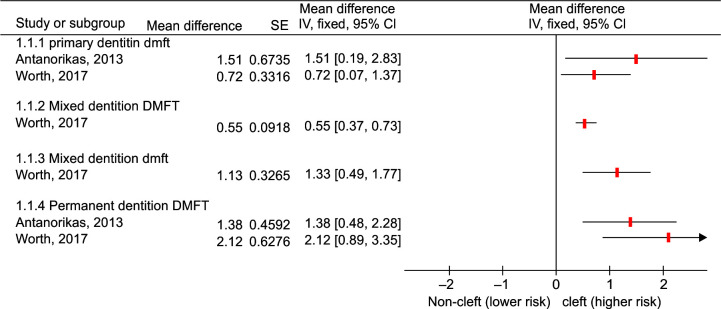

It is possible to comparable analyses across reviews if different populations or subgroups are analyzed. We summarized the outcome of effect measures given in the meta-analysis of the included studies considering dentition status of the study population (primary, mixed, and permanent). We used the estimate measures as mean difference, or standard mean of difference, with the respective confidence intervals (CI) of outcome measures and summarized using RevMan 5 software (Fig. 2). The mean difference between DMFT/S and dmft/s supports the higher risk of caries in CL/P relative to noncleft individuals.

Fig. 2.

Graphical summary of dental caries experience among children with cleft lip and/or palate in primary, mixed, and permanent dentition

Discussion

This umbrella review was aimed at offering a comprehensive assessment of dental caries experience among CL/P patients across published systematic review and meta-analysis by applying predefined methodological criteria. We identified three systematic reviews that showed substantial heterogeneity in terms of cleft type, age range, and geographical area. According to the findings, two reviews suggested unclear risk of bias and one review, published by Worth V et al., reported with low risk of bias10 (Table 4).

The Strict inclusion criteria regarding age- and sex-matched control groups and restriction of language to English and database to PubMed have led to a limited number of studies in the systematic review by Hasslöf P and Twetman S, 2007. The generalizability of the results may be questioned since the control group children were selected from a trauma clinic. There was no clear methodology pertaining to data collection and scoring criteria by Swedish council on technology assessment in healthcare for methodological quality assessment. The limited number of included studies and inconsistent finding resulted in inconclusive evidence for increased prevalence of caries in children with CL/P.

Antonarakis GS et al.9, assessed the prevalence of caries in non-syndromic CL/P patients in comparison with matched non-cleft control group at any given point in time had raised the concern of selection and publication bias. Absence of a priori protocol in PROSPERO made the comparison between planned and executed methodology impossible. Methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the checklist given by Agbaje JO et al.20, 2012 assessing caries experience. The standard of reporting in individual studies and the information given in each analysis regarding the methodology were often inadequate during the review of epidemiological surveys.20 It was proposed that a report should provide adequate and detailed details to make judgment on the validity of the results and conclusions. In the event of inadequate reporting and assumptions, conclusions are made that may lead to a false interpretation.

Review by Worth V et al., reported with a priori protocol registration in PROSPERO database with appropriate literature search having no restrictions on time and language.10 However, the limitation of the study reported that—not all articles could be translated due to limited funds. The selection criteria for cases which comprise < 20% syndromic CL/P and control group with any size including national data can theoretically lead to the potential bias and weakened results. In most of the included systematic reviews, the caries prevalence of CL/P patients’ data was pooled into one group, irrespective of type and severity of the cleft. This fails to provide a precise assessment of caries prevalence in individual cleft types. The standard of dental caries reporting may have contributed to random error, which could restrict direct comparisons of the absolute risk differences. The problem with the caries assessment involves predetermined light conditions, clinical examination, radiographic assessment, and caries detection rates and documentation. However, attempts were made for the methodological quality assessment to ensure accuracy. Hence, this review was reported with the low risk of bias using ROBIS tool.

The observation of summary estimate measures for primary, mixed, and permanent dentitions was similar, indicating increased risk of caries in patients with CL/P. The dmft/s and DMFT/S scoring methods are cumulative, which may lead to increased scores through childhood, then decline as the deciduous teeth are exfoliated and replaced with permanent dentition.18,19 This scoring system is commonly recorded as a mean value and may not be adequate as it sometimes skews distributions.

The frequency of developmental abnormalities in people with CL/P is greater as compared to the general population, with regards to the tooth shape (dental fusion, geminations, and peg-shaped lateral incisors), the enamel structure (dental hypoplasia), and tooth number (agenesis or supernumeraries).22 Infants with CL/P must be considered to be high caries risk group based on the microbiological changes, which could be significantly associated and correlated to their mothers’ microbiological data and caries level in comparison with noncleft infants.21,23 In addition, the presence of healing tissues facilitates the retention and/or hinders the control of bacterial plaque and poor oral hygiene following surgical procedures and orthodontic treatment.7 The parents’ understanding of the value of oral hygiene is shown to have major limitations to perform routine preventive dental home care for their children with CL/P.5 Enhanced help to continue and prioritize their intention to carry out daily toothbrushing within the context of their socioeconomic and educational status is utmost important. Therefore, pediatric dentist in cleft team should provide continuous support and educational programs for parents on oral hygiene, highlighting their importance to oral health and successful rehabilitation of CL/P patients.

We deviated from the protocol by searching additional databases of OVID and Epistemonikos database, which was not planned at the protocol stage. Repeated studies in any meta-analysis will involuntarily have a stronger weighting. The citation matrix for this review with the CCA was 0.26 (26% overlap). Quality appraisal of primary study level data was beyond its limits for this umbrella review. The authors’ findings therefore depend on interpretation of the included systematic review. Though this umbrella review does not focus on risk factors associated with the dental caries, there are various factors that may modify the caries risk that includes—cleft type, age and dentition of the child, gender, socioeconomic status, parents/caregiver educational status, and greater concern with corrective surgery than with the prevention or early treatment of caries that justify further investigation, considering all these as risk factors.

This umbrella review gives a narrative description for a better understanding of dental caries experience in CL/P patients. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no studies which reported caries measurement using International Caries Detection and Assessment System, which could assist the clinician to screen the patients at initial stages of the disease progression in cleft population. Early detection and prevention should be a key aspect of the multidisciplinary management of patients with CL/P. Implementing comprehensive preventive approaches addressing education, support, and compliance of parents/caregivers can lead to improved oral health, thus reducing the risk of caries in children with CL/P.

Conclusion

The following conclusions have been drawn, based on the findings of this umbrella review:

Dental caries experience of individuals with CL/P in primary, mixed, and permanent dentition is comparatively higher than those with the noncleft individual.

Two of the three included systematic reviews showed unclear risk of bias and their findings and recommendations need to be carefully examined.

Clinical Significance

This umbrella review gives the detailed review on dental caries experience among children and adolescents with CL/P. This study evinces the higher prevalence of dental caries among cleft population and highlights the important role of pediatric dentist in multidisciplinary healthcare team in implementing first dental visit and anticipatory guidance to prevent ECC in individuals with CL/P. The authors also recommend that the future research should focus on the implementation of infant oral care, and preventive strategies to raise caries-free children with CL/P.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Selvakumar H and Dr Kirthika M for proofreading the final manuscript. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. This was a self-funded project. The research submitted is original and conducted on data available in the public domain for systematic reviews or meta-analysis and not involves human or animal subjects. Hence, this paper is exempt from ethical committee approval. The research is original, not under publication consideration elsewhere. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Orcid

KC Vignesh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7117-7925

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Mossey PA, Shaw WC, Munger RG, et al. Global oral health inequalities: challenges in the prevention and management of orofacial clefts and potential solutions. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23(02):247–258. doi: 10.1177/0022034511402083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong FWL, King NM. The oral health of children with clefts - a review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998;35:248–254. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1998_035_0248_tohocw_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghazal T, Levy SM, Childers NK, et al. Factors associated with early childhood caries incidence among high caries-risk children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:366–374. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bokhout B, Hofman FXWM, van Limbeek J, et al. Incidence of dental caries in the primary dentition in children with a cleft lip and/or palate. Caries Res. 1997;31:8–12. doi: 10.1159/000262366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng LL, Moor SL, Ho CT. Predisposing factors to dental caries in children with cleft lip and palate: a review and strategies for early prevention. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44:67–72. doi: 10.1597/05-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnsen DC. Characteristics and backgrounds of children with nursing caries. Pediatr Dent. 1982;4:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahllöf G, Ussisoo-Joandi R, Ideberg M, Modéer T. Caries, gingivitis, and dental abnormalities in preschool children with cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft Palate J. 1989;26:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasslöf P, Twetman S. Caries prevalence in children with cleft lip and palate? A systematic review of case-control studies. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonarakis GS, Palaska PK, Herzog G. Caries prevalence in non-syndromic patients with cleft lip and/or palate: a meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2013;47:406–413. doi: 10.1159/000349911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worth V, Perry R, Ireland T, et al. Are people with an orofacial cleft at a higher risk of dental caries? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BDJ. 2017;223:37–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigues R, Fernandes MH, Bessa Monteiro A, et al. Are there any solutions for improving the cleft area hygiene in patients with cleft lip and palate? A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2019;17(02):130–141. doi: 10.1111/idh.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells M. Review suggests that cleft lip and palate patients have more caries. Evid Based Dent. 2014;15:79. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, et al. Chapter 10: Umbrella Reviews. Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual, 2017 In: (Eds). [online] Available from https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. [Last accessed November, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins J, Lane PW, Anagnostelis B, et al. A tool to assess the quality of a meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4:351–366. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane. 2019 [online] Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. [Last accessed November, 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, et al. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smallridge J, Hall AJ, Chorbachi R, et al. Functional outcomes in the Cleft Care UK Study. Part 3: oral health and audiology. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2015;18:25–35. doi: 10.1111/ocr.12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khoun T, Malden PE, Turton BJ. Oral health-related quality of life in young Cambodian children: a validation study with a focus on children with cleft lip and/or palate. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28:326–334. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agbaje JO, Lesaffre E, Declerck D. Assessment of caries experience in epidemiological surveys: a review. Community Dent Health. 2012;29:14–19. 22482243 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durhan MA, Topcuoglu N, Kulekci G, et al. Microbial profile and dental caries in cleft lip and palate babies between 0 and 3 years old. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018;56:349–356. doi: 10.1177/1055665618776428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirthiga M, Muthu MS, Ankita S, et al. Risk factors for early childhood caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case control and cohort studies. Pediatr Dent. 2019;41:95–106. 30992106 journal. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henry JA, Muthu MS, Saikia A, et al. Prevalence and pattern of early childhood caries in a rural South Indian population evaluated by ICDAS with suggestions for enhancement of ICDAS software tool. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2016;27:191–200. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]