Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to find evidence to determine which strategies are effective for improving hospitalised patients’ perception of respect and dignity.

Methods

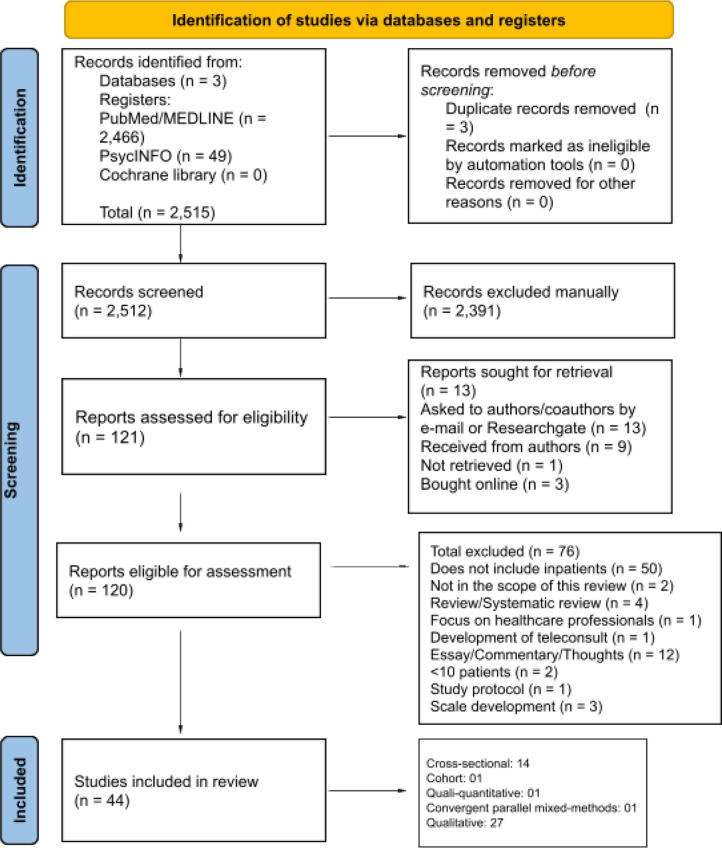

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines. The MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library databases were searched on 9 March 2021. Observational studies, prospective studies, retrospective studies, controlled trials and randomised controlled trials with interventions focused on improving respect for patients and maintaining their dignity were included. Case reports, editorials, opinion articles, studies <10 subjects, responses/replies to authors, responses/replies to editors and review articles were excluded. The study population included inpatients at any health facility. Two evaluators assessed risk of bias according to the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions criteria: allocation, randomisation, blinding and internal validity. The reviewers were blinded during the selection of studies as well as during the quality appraisal. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results

2515 articles were retrieved from databases and 44 articles were included in this review. We conducted a quality appraisal of the studies (27 qualitative studies, 14 cross-sectional studies, 1 cohort study, 1 quali-quantitative study and 1 convergent parallel mixed-method study).

Discussion

A limitation of this study is that it may not be generalisable to all cultures. Most of the included studies are of good quality according to the quality appraisal. To improve medical and hospital care in most countries, it is necessary to improve the training of doctors and other health professionals.

Conclusion

Many strategies could improve the perception of respect for and the dignity of the inpatient. The lack of interventional studies in this field has led to a gap in knowledge to be filled with better designed studies and effect measurements.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021241805.

Keywords: mental health, medical ethics, medical education & training, psychiatry, public health, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were followed in this systematic review.

A comprehensive search strategy was employed to locate studies related to the respect and dignity of inpatients, reaching many countries around the world on virtually every continent.

The data were not homogeneous enough to perform a meta-analysis, which could enrich the results.

One study could not be retrieved, and it might have data that could be important to the results of this study.

Some studies presented qualitative data which were difficult to determine their validity in different cultures.

Introduction

Dignity is a fundamental human right,1 and its maintenance is an ethical goal of care.2 The Brazilian Code of Medical Ethics3 states that physicians must respect and act in patients’ benefit. The Declaration on the Promotion of Patients’ Rights in Europe,4 states that one of its objectives is ‘to reaffirm fundamental human rights in health care’.

The concept of dignity is still not clearly defined,5 and it can be affected during hospitalisation.6 Hospital routines are needed to promote and protect patient health, but they can be harmful when patients experience stigma,7 violation of rights, privacy, integrity, disrespect and breaches in confidentiality, and when facing unprepared and insecure professionals who cannot provide clear explanations about diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. All of these can lead to complaints, which can be used as a tool for improving patient care.8

One may think that dignity and respect violations are restricted to low-income countries or to people of low socioeconomic status, but it is a worldwide phenomenon, and it is not directly related to wealth, but to culture and professional education. Several studies suggest that patients’ rights are violated daily in practically all scenarios of practice of health-related activities. However, its results are sparse and there is no systematisation of what can improve patients’ perception of receiving respectful and dignified care.

Published studies, as we will see later, address specific specialties in isolation and few address this important topic comprehensively. The strategies used to improve the quality of care and the perception of respect and dignity from the patients’ point of view may seem obvious, but they are not observed in practice in several countries and continents. Thus, it is necessary to review the current literature in search of strategies that can positively impact patients’ perception of respect and dignity.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate worldwide evidence to determine which strategies can be used to improve inpatient patients’ perception of respect and dignity.

Study design

A systematic review with the aim of identifying, analysing, extracting and evaluating data from the literature related to respect for and maintenance of the dignity of hospitalised patients. It also aims to identify knowledge gaps and relate the findings to clinical practices to improve the quality of care for all hospitalised patients worldwide.

Methods

This study was registered at PROSPERO and conducted following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.9 Articles were identified by searching electronic records, including the MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library databases. The quoted search terms used were as follows: Patient human rights violation OR Patient disrespect OR Patient violation of dignity OR Patient rights protection OR patient intimacy violation OR patient confidentiality violation OR ethical violation OR ethics violation OR hospital violation of patients’ rights OR patients’ perception of rights violation OR patients’ perception of disrespect. There were no restrictions on year or language of publication, and no automation tool was used. The main objective was to find any interventions and multifaceted interventions aimed at improving inpatients’ perception of respect and dignity and decreasing disrespect or human/inpatient rights violations, intimacy violations, confidentiality violations, autonomy violations, etc. The search included interventions conducted in hospitals, day hospitals, clinics, emergency departments, psychiatric emergencies, psychiatric hospitals, asylums and any other places where there are inpatients. The inclusion criteria were full text, observational studies, prospective studies, retrospective studies, controlled trials and randomised controlled trials. The exclusion criteria were case reports, editorials, opinion articles, studies <10 subjects, responses/replies to authors and responses/replies to editors.

The first author (PEPD) screened the titles and abstracts of the articles and manually excluded those articles that did not fit the inclusion criteria.

After that, two reviewers (PEPD and LAQ) independently assessed the full texts of the remaining articles for eligibility in a standardised manner: data extraction was performed independently, and disagreements between reviewers regarding the study selection or data extraction were resolved by consensus. If a consensus was not reached, the third reviewer (AEN) was consulted.

The following information was extracted from the full-text articles using an Excel spreadsheet: authors, place/year of publication, sample size, type of samples, study design, analysis, data/measure, strategies, interventions to achieve improvements and limitations.

Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias using the following criteria from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2.10 Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third reviewer. The minimum number of studies for data to be pooled was 10, including any intervention that would be effective for improving the perception of respect and dignity among inpatients.

A quality appraisal of the articles was performed using the CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist,11 Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE) 2018,12 CASP Cohort Study Checklist13 and Mays and Pope Qualitative research in healthcare.14

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Quality appraisal

A critical appraisal of the included studies was performed, but no study was excluded based on its score, although this approach makes their analysis more robust. The instruments used for it were: CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist11 (online supplemental table 1); SURE—questions to assist with the critical appraisal of cross-sectional studies12 (online supplemental table 2); CASP Cohort Studies Checklist13 (online supplemental table 3) and the criteria put forth by Mays and Pope14 (online supplemental table 4).

bmjopen-2021-059129supp001.xlsx (31.5KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp002.xlsx (24.7KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp003.xlsx (12.1KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp004.xlsx (12.2KB, xlsx)

They were scored as follows: 0=not or inadequately addressed, 1=partially addressed and 2=fully addressed criterion. Critical appraisal scores are described in each table.

The quality assessment of the studies and of the systematic review was performed by two reviewers independently (PEPD and LAQ), who then discussed and agreed to the final rating. No study was excluded for quality reasons, but this assessment enabled a more robust review of the studies.

Risk of bias

To minimise bias, two reviewers assessed the risk of bias using the following criteria from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.210: methods for allocation, methods for randomisation, blinding and evaluation of internal validity. The reviewers were blinded during the selection of studies to be included and excluded as well as during the quality appraisal. Disagreements were resolved by consensus after the reviewers’ judgement.

Results

Three databases were searched on 9 March 2021: PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library. Of the 2515 results, no article was excluded by automation tools, 3 were excluded after searching for duplicate studies using the EndNote Web tool and 2375 were excluded after title and abstract screening by the first reviewer (PEPD). In the second step, two reviewers (PEPD and LAQ) independently assessed the 121 articles for eligibility.

Thirteen references were not found. The first reviewer (PEPD) contacted by email and/or via ResearchGate—more than once—authors, coauthors and journals where they were published to try to retrieve them. Up to 5 August 2021, nine articles were retrieved, three were bought online from publishers and one was not retrieved and excluded. A total of 76 articles were excluded: 50 did not include inpatients, 2 were not in the scope of this review, 4 were review/systematic review, 1 focused on healthcare professionals, 1 focused on the development of telehealth, 12 were essay/commentary/thoughts, 2 included less than 10 patients, 1 was a study protocol and 3 were scale developments.

Forty-four articles were included, according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines9 (figure 1): 14 cross-sectional studies, 1 cohort study, 1 quali-quantitative study, 1 convergent parallel mixed-method study and 27 qualitative studies.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

The results of articles classified as high-quality in the quality assessment receive more emphasis than those with a lower classification. They were divided according to the main themes.

Religion, emergency, psychiatric and paediatric patients

Violations of patients’ dignity and privacy are almost routine. The simple act of providing a patient list to third parties for religious visits without consent is considered a violation of privacy.15 Likewise, the seclusion to which psychiatric patients in agitation are subjected, often as a form of punishment, also constitutes a violation of dignity, as they are often not offered liquids and food, which makes them feel humiliated.16 17

In all cases, there is a fundamental element missing, communication. In paediatrics, for example, the lack of communication between doctors and parents and patients produces anxiety and confusion,18 which could be avoided if the professional talked to families in an open and understanding way, demonstrating knowledge and security in their work. This same feeling of vulnerability and powerlessness is experienced by emergency patients, considered of low priority, as they feel insecure, exposed and violated in their self-esteem, as they wait for professional attention for several hours in some cases.19 When the patient is of a different ethnicity from that of the doctor, this feeling of inferiority increases, as patients feel the need to be treated as equals, as people, as being important and want to have their complaints heard, receive polite, timely and with clear explanations.20

Obstetric patients

The feeling of invasion of privacy and lack of respect and dignity is common among obstetric patients from the first contact with obstetricians, as there is a lack of training in respectful maternity care (RMC), counselling skills, in building a good physician–patient relationship.21 Professionals allege overwork, low and inadequate remuneration, lack of training, precarious and inadequate working conditions, overload due to lack of professionals,22 which can improve with investment in training, in more dignified working conditions, in improving of remuneration, in the availability of contact with other professionals for learning and consultations, as well as with a better understanding of the cultural context of the patient and the professional.23 24 Better communication between professionals and pregnant women and mothers can contribute to building a relationship of trust, promoting their engagement in breast feeding and baby care.25

The female body undergoes several transformations during pregnancy, such as weight gain. Some pregnant women feel embarrassed by their doctors, due to stigma related to their weight gain, which can undermine the doctor–patient relationship.26 In Jordan, for example, women end up seeking private assistance in search of a little more respect for their privacy, since public hospitals lack sheets to cover themselves, leaving their bodies and intimacy exposed.27

The promotion of RMC among women and health professionals can improve the quality of care provided,28 reduce social stigma, as women with lower levels of education and lower socioeconomic status feel stigmatised and perceive that they are treated with less quality than others with better economic and social status.29 Disrespectful, unkind, rude and negativistic behaviours only contribute to increase the level of stress and generate distrust in the parturient, who has often denied her right to a companion, feeling uninformed, abandoned, neglected and objectified during childbirth and post partum.30–34

In rural Afghanistan, the training of professionals had a positive impact on the satisfaction of pregnant women in relation to health services, although there are still complaints,35 related to disrespect, low quality of services, maltreatment and disagreements between doctors and patients,36 as well as in Peru, where most research participants had already suffered at least one episode of disrespect and abuse during pregnancy and childbirth.37 The WHO recommends improvements in the quality of treatment and care for women to reduce stigma and poor care and to promote respect and dignity.38 39

General hospital patients

Cultural and ethnic differences between nurses and patients can contribute to negative perceptions of disrespectful and unfair treatment, particularly among ethnic minorities.40 41 Thus, it is necessary for health professionals to be attentive to recognise factors that violate or preserve dignity from the patient’s point of view,42 such as interpersonal problems, professional availability and lack of empathy in communication,43 even when the patient does not actively complaint, the professional must take a more proactive stance to identify and respond to the patient’s needs in a timely manner, with strategies to improve patient safety, promoting their involvement in the care of their health.44 45 To this end, managers need to be sensitised to invest in professional education, to keep professionals attentive to patients’ rights, reducing treatment inequities that lead patients to pilgrimage through health services in search of more dignified treatment.46 47

Professional development should also promote strategies that ensure patients’ privacy, not only of their personal and health information,48 since a leak can undermine the reputation of a health facility, as patients bring to the hospital expectations of receive security, respect, dignity, information and care.49 Touching patients’ personal objects or moving them can be perceived as an invasion of territory and privacy, causing discomfort,50 reinforcing the need to provide information about privacy and confidentiality before and during hospitalisation.51 A Greek study showed that patients had little idea of their rights52 and nursing has a very important role in disseminating this knowledge and ethical principles, establishing a relationship of respect for patients’ rights and privacy.53–55 Intensive care unit patients often have memories of the environment as hostile and stressful, generating negative feelings of violation of their rights to dignity and privacy, lack of empathy, not being understood, delay in getting help and being subject to full control by health professionals.56

Most patients are unaware of their rights57; a study with the distribution of information cards to patients with methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection, which should be presented to the professionals with whom they would consult, showed that these patients are subject to discrimination and lack of knowledge, which makes its use questionable.58 It is therefore imperative that healthcare professionals keep the concept of integrity in mind and that this knowledge is used to train healthcare professionals with more professionalism, communication skills and practice-based learning.59 60 In an increasingly digital age, resources for preserving information and privacy are essential, since patients’ autonomy is closely intertwined with their dignity,61–63 which can positively impact the quality of empathic, non-possessive care, authentic and respectful, with positive results in treatment outcomes.64

Discussion

These studies reveal that there are several strategies that can improve the quality of care provided to inpatients, thus improving their perception of respect for and the maintenance of their dignity. There is a Hippocratic principle that guides the medical profession, ‘first, do no harm’ and that must be considered in all spheres not only of the doctor–patient relationship, but of any relationship between health professionals and patients. Therefore, although we did not find studies with statistically calculated interventions and effect size measurements, the quality of the studies included in this systematic review allows us to point out some strategies that can help improve patients’ perceptions regarding respect for and maintenance of their dignity. Patients and health professionals around the world express the same interests and desires to have the quality of care raised to the level of excellence and the rights of patients respected.

It is necessary to keep in mind that minor violations of patients’ rights happen daily, even when it is considered to have good intentions, as in the case of visits by religious to patients. Their names cannot be placed on a list without consent, as this constitutes an invasion of privacy. Likewise, when a patient needs mechanical restraint or seclusion due to aggressiveness, it is necessary to offer fluids, food and attention, to understand why the patient acted that way, as many see this attitude as a violation of human rights or as punishment, so that the experience fulfils its therapeutic goals and does not become a source of trauma for the patient or a painful psychic experience.

One of the keys to good relationships with patients is communication. Parents of paediatric patients, as well as patients themselves, need clear information, which gives them a sense of confidence and security. Professionals need to demonstrate skill, knowledge and confidence during their interventions, to guarantee the best treatment for their patients and to allow patients and their parents to make the best decisions for the quality of life of their children.

Feelings of humiliation, impotence and being ‘left aside’ affect emergency patients, with lower risk conditions, which makes them wait for care for long periods. These patients need to receive information about their conditions and the functioning of the emergency department, they must receive information and attention from the nursing staff, as their condition can progress to more serious situations or death, if they are not checked frequently. When patients have different ethnicities than professionals, the asymmetry of the relationship seems to be exacerbated by the behaviour of some professionals, leading patients to feel discriminated against, treated in a dehumanised and disrespectful way. Allowing the patient to speak, listening to the patient carefully and valuing their complaints and opinions gives them the feeling of being respected and seen as an equal person. Professionals must be aware of these subtleties of human behaviour and spend more time assisting these patients in a way that makes them feel more respected and welcomed. These small actions can make a difference when a patient seeks treatment or professional help.

The field of obstetrics is one of the fields that has more studies on the respect and dignity of patients, including the prepartum, pregnancy and postpartum periods. It is necessary for professionals in the field to be trained regarding RMC. It is a woman’s right to receive clear information; respectful and dignified treatment; to hug and breast feed her child in the immediate postpartum period; to have her intimacy and privacy preserved; not being subjected to episiotomy without consent or without anaesthesia; having a family member accompanying them; not being discriminated against because of their weight, ethnicity, colour, race, sexuality, religion, socioeconomic status, place of residence, state or country of origin; to have a companion during childbirth, whether a family member or friend; the right not to be verbally or physically abused (not to be cursed or verbally humiliated; not to be slapped during childbirth, for example); the right not to have their bodies exposed in a hospital environment, where there is a large circulation of professionals (to be covered by a sheet); the right not to have their bodies invaded by several individuals (not being exposed to frequent vaginal examinations by various professionals, especially in teaching hospitals); the right to receive information about prenatal care, pregnancy, childbirth, post partum, breast feeding, contraception, vaccination and infectious-contagious diseases that can affect the mother and baby; the right to have quality and humanised care in any device in the care network, whether public or private; the right to receive analgesia or anaesthesia; and the right to have less prolonged care, whether public or private.

Obstetric violence is present in several fields of action, among the various health professionals who work in this area, from harshly speaking to or yelling at, to physically or sexually assaulting a woman. Considering the most diverse studies on the subject, this practice is widespread in several countries around the world, from the USA to Asian countries, and there needs to be a large investment in education and training of health professionals so that women of childbearing age can be assisted with dignity and respect.

Professionals should be aware of the cultural subtleties of the patients they serve, as many behaviours may seem inappropriate in multicultural contexts, as the patient’s education, culture, socioeconomic level and religion produce different perceptions about the professionals’ conduct. This can lead to negative perceptions and complaints, for example, regarding discrimination and quality of care.

A conciliatory and more proactive attitude towards avoiding conflicts can improve patients’ perception of the professional and the health facility during the hospitalisation period. The investment in training and education of health professionals is the best solution to improve the quality of care, bringing patients to a more active position in their treatment, promoting information and autonomy, aiding in a timely manner, respecting rights, maintaining vigilance in cases of disrespect and violations of dignity, encouraging the acceptance of differences, reducing all types of prejudice and stigma, and allowing professionals and patients to act together.

Small attitudes of health professionals can turn into big problems: touching personal belongings without authorisation, moving objects, exposing the patient and making inappropriate comments, even though it may seem like just an innocent joke. One of the solutions may be to ask patients and family members to carry out assessments about the service, analyse complaints in the ombudsman’s office, and use these data as important tools to improve the quality of the service provided. Patient concern regarding the confidentiality of their medical information is another point that deserves attention. The right to privacy and confidentiality is directly related to the respect and dignity of patients. Violations of confidentiality, in addition to being unethical, can cause moral and financial damage to patients and their families, leading to legal actions against professionals and hospitals. Another way to give patients more freedom and autonomy is to guarantee them access to their medical information, either through direct access to the system or through applications. Thus, managers and government officials must invest in information security systems, since the world is increasingly digital and the trend is to reduce the use of printed documents, ensuring the protection of data for patients and professionals. Patients must receive information about current legislation in terms of information security, their rights to privacy and confidentiality, and nursing has a fundamental role in the dissemination of ethical principles in the work environment.

The results found in the articles included in this systematic review show that there is still a long way to go in promoting more dignified and respectful care for patients admitted to healthcare units around the world. The innovation is in the synthesis and enumeration of these practices, which can bring a new way of dealing with information and profoundly change the way we serve and think about the care provided to hospitalised patients. Regardless of culture and nationality, studies show that there is a need to improve the quality of care, whether through improvements in education during graduation, in student training, in the use of reality data to refine professional practice, or through training of professionals when entering the labour market, offering refresher courses, recycling professionals and promoting the availability of safe means by which professionals can discuss cases and share knowledge without breaching professional secrecy.

Strengths of this study

Our study covers a wide range of topics related to the respect and dignity of inpatients, reaching many countries around the world on virtually every continent. In addition, this systematic review fills a knowledge gap in an area that has not yet been studied, which, although gaining prominence in recent years, lacks more research and development. The fact that there is no limitation on the time researched and, on the language, allowed us to reach from the most recent to the oldest studies on this topic.

Limitations

Although we have tried to reach as many studies as possible, its results cannot be generalised to all cultures and countries of the world, and it does not include all specialties and their peculiarities. One study could not be retrieved, and it might have data that could be important to the results of this study. The data were not homogeneous enough to perform a meta-analysis, which would enrich the results. More studies with controlled interventions and outcomes should be carried out to measure the effect on the perception of respect for and maintenance of the dignity of hospitalised patients.

Statement of findings

Regarding clinical practice, our study brings several collaborations based on the findings of the reviewed articles. Actions to promote dignity include: providing information correctly and clearly about procedures and treatments, serving with politeness and kindness, avoiding gestures and comments that might be perceived as disrespectful, putting aside prejudices (you are not there to judge but to serve to the best of your ability and professional ethics), taking as much time to serve as necessary, adhering to confidentiality when sharing information with team members, listening to complaints and trying to resolve them, responding to timely calls, using patient complaints made as a way to improve the hospital routine, promoting improvements in the quality of the environment (including cleaning, lighting and noise control), allowing pregnant women to have companions, avoiding yelling at patients or using physical touch as a form of reprimand (which can be understood as physical aggression), avoiding unnecessary exposure of the patient’s body, avoiding intimate examination by various professionals (especially in teaching hospitals), obtaining consent for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, informing patients about the drugs that will be applied (name and what they are used for), introducing oneself to the patient, asking if the patient wants to receive visits and from whom, asking who the patient would like to share information with, calling the patient by his or her name (avoiding colloquial or derogatory language), demonstrating knowledge, showing security and professional skills, and using setbacks as opportunities for your own and for your team’s collective learning.

Implications for practice

Our findings provide perspectives that could and should be used to improve patient care and education in different areas of health around the world.

Implications for research

Virtually all studies related to the quality of care, respect, dignity, confidentiality and privacy of hospitalised patients, have a qualitative or cross-sectional design. It is necessary that future research be designed with controlled interventions and effect size measurement to bring more robustness to the findings, since this subject is gaining prominence in daily practice. Furthermore, regardless of the country, respect and dignity are universal and fundamental rights of every human being and must, therefore, be put into practice wherever patients are.

Conclusion

Our systematic review touches on important points of care during professional practice, with the aim of delivering truly patient-centred care to patients.

Professional practice is regulated by legal means and by professional education, but it is observed that there is a lack of training so that various everyday conflicts can be mitigated and resolved locally without harming the patient. It is inconceivable that patients need to look for another health facility because they feel mistreated at a place that should provide care. Likewise, it is unacceptable for a health professional not to be able to handle situations in their professional routine without resorting to violence or verbal aggression. When a patient goes to a health unit, he or she seeks care; therefore, we have the obligation to provide care, without prejudice, without discrimination and to the best of our technical capacity, with respect and dignity. This is the wish of all patients around the world.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The study concept was developed by PEPD. The manuscript of the protocol was drafted by PEPD and critically revised by LAQ and AEN. PEPD developed and provided feedback for all sections of the review protocol and approved the final manuscript. The search strategy was developed by PEPD and LAQ. Study selection was performed by PEPD and LAQ. Data extraction and quality assessment was performed by PEPD and LAQ, with AEN as a third party in case of disagreements. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. PEPD - Guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.United Nations . Universal Declaration of human rights. Available: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights [Accessed 08 Jun 2021].

- 2.Ferri P, Muzzalupo J, Di Lorenzo R. Patients' perception of dignity in an Italian General Hospital: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:41–8. 10.1186/s12913-015-0704-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicina CFde. Código de Ética Médica [Internet]. Conselho Federal de Medicina, 2019. Available: https://portal.cfm.org.br/images/PDF/cem2019.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2021].

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) . A Declaration on the Promotion of Patients Rights in Europe. [Internet], 1994. Available: https://www.who.int/genomics/public/eu_declaration1994.pdf [Accessed 08 Jun 2021].

- 5.Bagheri A. Elements of human dignity in healthcare settings: the importance of the patient's perspective. J Med Ethics 2012;38:729–30. 10.1136/medethics-2012-100743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campillo B, Corbella J, Gelpi M, et al. Development and validation of the scale of perception of respect for and maintenance of the dignity of the inpatient [CuPDPH]. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 2020;15:100553. 10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, et al. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev 2015;16:319–26. 10.1111/obr.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirzoev T, Kane S. Key strategies to improve systems for managing patient complaints within health facilities - what can we learn from the existing literature? Glob Health Action 2018;11:1458938. 10.1080/16549716.2018.1458938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021;10:89. 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane.org . Chapter 7: Considering bias and conflicts of interest among the included studies [Internet]. Available: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-07 [Accessed 08 Jun 2021].

- 11.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [Internet]. B-cdn.net. Available: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf [Accessed 06 Jul 2021].

- 12.Cardiff.ac.uk . Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE). Questions to assist with the critical appraisal of cross-sectional studies [Internet], 2015. Available: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/212775/SURE_Qualitative_checklist_2015.pdf [Accessed 09 Jul 2021].

- 13.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . CASP Cohort Study Checklist [Internet]. B-cdn.net. Available: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf [Accessed 26 Jul 2021].

- 14.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erde E, Pomerantz SC, Saccocci M, et al. Privacy and patient-clergy access: perspectives of patients admitted to hospital. J Med Ethics 2006;32:398–402. 10.1136/jme.2005.012237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faschingbauer KM, Peden-McAlpine C, Tempel W. Use of seclusion: finding the voice of the patient to influence practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2013;51:32–8. 10.3928/02793695-20130503-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robins CS, Sauvageot JA, Cusack KJ, et al. Consumers' perceptions of negative experiences and "sanctuary harm" in psychiatric settings. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:1134–8. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao JL, Evan EE, Zeltzer LK. Parent and child perspectives on physician communication in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2007;5:355–65. 10.1017/S1478951507000557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahlen I, Westin L, Adolfsson A. Experience of being a low priority patient during waiting time at an emergency department. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2012;5:1–9. 10.2147/PRBM.S27790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beach MC, Branyon E, Saha S. Diverse patient perspectives on respect in healthcare: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:2076–80. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burrowes S, Holcombe SJ, Jara D, et al. Midwives' and patients' perspectives on disrespect and abuse during labor and delivery care in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:263–74. 10.1186/s12884-017-1442-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dynes MM, Twentyman E, Kelly L, et al. Patient and provider determinants for receipt of three dimensions of respectful maternity care in Kigoma region, Tanzania-April-July, 2016. Reprod Health 2018;15:41–64. 10.1186/s12978-018-0486-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebremichael MW, Worku A, Medhanyie AA, et al. Mothers' experience of disrespect and abuse during maternity care in northern Ethiopia. Glob Health Action 2018;11:1465215. 10.1080/16549716.2018.1465215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebremichael MW, Worku A, Medhanyie AA, et al. Women suffer more from disrespectful and abusive care than from the labour pain itself: a qualitative study from women's perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:392–7. 10.1186/s12884-018-2026-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwood C, Haskins L, Luthuli S, et al. Communication between mothers and health workers is important for quality of newborn care: a qualitative study in neonatal units in district hospitals in South Africa. BMC Pediatr 2019;19:496–508. 10.1186/s12887-019-1874-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Smieszek SM, Nippert KE, et al. Pregnant and postpartum women's experiences of weight stigma in healthcare. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:499–508. 10.1186/s12884-020-03202-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussein SAAA, Dahlen HG, Ogunsiji O, et al. Uncovered and disrespected. A qualitative study of Jordanian women's experience of privacy in birth. Women Birth 2020;33:496–504. 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jolly Y, Aminu M, Mgawadere F, et al. "We are the ones who should make the decision" - knowledge and understanding of the rights-based approach to maternity care among women and healthcare providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:42–9. 10.1186/s12884-019-2189-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanengoni B, Andajani-Sutjahjo S, Holroyd E. Women's experiences of disrespectful and abusive maternal health care in a low resource rural setting in eastern Zimbabwe. Midwifery 2019;76:125–31. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khresheh R, Barclay L, Shoqirat N. Caring behaviours by midwives: Jordanian women's perceptions during childbirth. Midwifery 2019;74:1–5. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Freedman LP, et al. Association between Disrespect and abuse during childbirth and women's confidence in health facilities in Tanzania. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2243–50. 10.1007/s10995-015-1743-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, et al. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:268–80. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millicent Dzomeku V, van Wyk B, Lori JR. Experiences of women receiving childbirth care from public health facilities in Kumasi, Ghana. Midwifery 2017;55:90–5. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A, Rodríguez-Almagro D, et al. Women’s perceptions of living a traumatic childbirth experience and factors related to a birth experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:1654–66. 10.3390/ijerph16091654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thommesen T, Kismul H, Kaplan I, et al. “The midwife helped me … otherwise I could have died”: women’s experience of professional midwifery services in rural Afghanistan - a qualitative study in the provinces Kunar and Laghman. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:140–56. 10.1186/s12884-020-2818-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The giving voice to mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health 2019;16:77–94. 10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montesinos-Segura R, Urrunaga-Pastor D, Mendoza-Chuctaya G, et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in fourteen hospitals in nine cities of Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;140:184–90. 10.1002/ijgo.12353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Healthpolicyproject.com . The White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women [Internet]. Available: http://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/46_FinalRespectfulCareCharter.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug 2021].

- 39.WHO Statement . The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth [Internet]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug 2021].

- 40.Asmaningrum N, Kurniawati D, Tsai Y-F. Threats to patient dignity in clinical care settings: a qualitative comparison of Indonesian nurses and patients. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:899–908. 10.1111/jocn.15144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract 2004;53:721–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebrahimi H, Torabizadeh C, Mohammadi E, et al. Patients' perception of dignity in Iranian healthcare settings: a qualitative content analysis. J Med Ethics 2012;38:723–8. 10.1136/medethics-2011-100396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King JD, van Dijk PAD, Overbeek CL, et al. Patient complaints emphasize non-technical aspects of care at a tertiary referral hospital. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2017;5:74–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howard M, Fleming ML, Parker E. Patients do not always complain when they are dissatisfied: implications for service quality and patient safety. J Patient Saf 2013;9:224–31. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182913837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hrisos S, Thomson R. Seeing it from both sides: do approaches to involving patients in improving their safety risk damaging the trust between patients and healthcare professionals? an interview study. PLoS One 2013;8:e80759. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khademi M, Mohammadi E, Vanaki Z. On the violation of hospitalized patients' rights: a qualitative study. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:576–86. 10.1177/0969733017709334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleury S, Bicudo V, Rangel G. Reacciones a la violencia institucional: estrategias de Los pacientes frente al contraderecho a la salud en Brasil. Salud Colect 2013;9:11–25. 10.1590/S1851-82652013000100002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuo K-M, Ma C-C, Alexander JW. How do patients respond to violation of their information privacy? Health Inf Manag 2014;43:23–33. 10.1177/183335831404300204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee AV, Moriarty JP, Borgstrom C, et al. What can we learn from patient dissatisfaction? an analysis of dissatisfying events at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med 2010;5:514–20. 10.1002/jhm.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marin CR, Gasparino RC, Puggina AC. The perception of Territory and personal space invasion among hospitalized patients. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198989. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohammadi M, Larijani B, Emami Razavi SH, et al. Do patients know that physicians should be Confidential? study on patients' awareness of privacy and confidentiality. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2018;11:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merakou K, Dalla-Vorgia P, Garanis-Papadatos T, et al. Satisfying patients' rights: a hospital patient survey. Nurs Ethics 2001;8:499–509. 10.1177/096973300100800604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ming Y, Wei H, Cheng H, et al. Analyzing patients' complaints: awakening of the ethic of belonging. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2019;42:278–88. 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Öztürk H, Torun Kılıç Çiğdem, Kahriman İlknur, et al. Assessment of nurses' respect for patient privacy by patients and nurses: a comparative study. J Clin Nurs 2021;30:1079–90. 10.1111/jocn.15653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pupulim JSL, Sawada NO. Percepção de pacientes sobre a privacidade no Hospital. Rev Bras Enferm 2012;65:621–9. 10.1590/S0034-71672012000400011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanson G, Lobefalo A, Fascì A. "Love Can't Be Taken to the Hospital. If It Were Possible, It Would Be Better": Patients' Experiences of Being Cared for in an Intensive Care Unit. Qual Health Res 2021;31:736–53. 10.1177/1049732320982276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santos LR, Beneri RL, Lunardi VL. [Ethical questions in the work of the health team: the (dis)respect to client's rights]. Rev Gaucha Enferm 2005;26:403–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skyman E, Bergbom I, Lindahl B, et al. Notification card to alert for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is stigmatizing from the patient's point of view. Scand J Infect Dis 2014;46:440–6. 10.3109/00365548.2014.896029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Widäng I, Fridlund B. Self-respect, dignity and confidence: conceptions of integrity among male patients. J Adv Nurs 2003;42:47–56. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wofford MM, Wofford JL, Bothra J, et al. Patient complaints about physician behaviors: a qualitative study. Acad Med 2004;79:134–8. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kayaalp M. Patient privacy in the era of big data. Balkan Med J 2018;35:8–17. 10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.0966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodríguez-Prat A, Monforte-Royo C, Porta-Sales J, et al. Patient perspectives of dignity, autonomy and control at the end of life: systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151435. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kisvetrová H, Tomanová J, Hanáčková R, et al. Dignity and predictors of its change among inpatients in long-term care. Clin Nurs Res 2022;31:274–83. 10.1177/10547738211036969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kallergis G. [The contribution of the relationship between therapist-patient and the context of the professional relationship]. Psychiatriki 2019;30:165–74. 10.22365/jpsych.2019.302.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-059129supp001.xlsx (31.5KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp002.xlsx (24.7KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp003.xlsx (12.1KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059129supp004.xlsx (12.2KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.