Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Vertical integration is increasingly common among surgical specialties in the US; however, the effect of vertical integration on access to care for low-income populations remains poorly understood. We explored the characteristics of surgical practices associated with vertical integration and the effect of integration on surgical access for Medicaid populations.

STUDY DESIGN:

Using a survey of US office-based physician practices, we examined characteristics of 15 surgical subspecialties from 2007 to 2017, including provider sex and specialty, practice payer mix, surgical volume, and county socioeconomic status. Using multivariable logistic regression and time-series analysis, we evaluated practice and provider characteristics associated with vertical integration—our primary outcome—and practice Medicaid acceptance rates—our secondary outcome.

RESULTS:

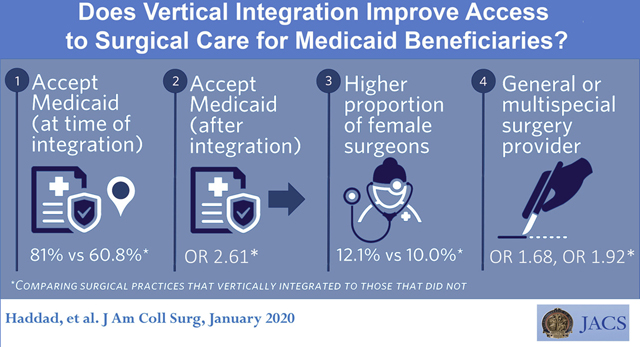

Our analysis included 84,795 unique surgical practices (303,903 practice-years). The rate of vertical integration during the 10-year period was 18.0%, with 72.1% of surgical practices never integrating. Practices that integrated were more likely to accept Medicaid patients than practices that did not (81.0% vs 60.8%, p < 0.001). Accepting Medicaid increased the likelihood of vertical integration relative to practices that did not (odds ratio [OR] 4.20, 95% CI 3.93 to 4.49). Practices that integrated were more likely to accept Medicaid in the future (OR 2.61, 95% CI 2.40 to 2.83), even after adjusting for previous Medicaid acceptance and hospital and time fixed effects.

CONCLUSIONS:

Surgical practices caring for the underinsured are more likely to join larger health care systems, driven by market characteristics. Vertical integration is associated with future increased rates of Medicaid acceptance among practices, allowing for increased access to surgical care for vulnerable, low-income patients. The potential benefit of increased surgical access for low-income beneficiaries from vertical integration must be balanced with the potential for increased prices.

An increasing number of surgical practices in the US are vertically integrating—associating financially and administratively with hospitals or large physician groups rather than smaller, independent practice arrangements.1–5 Multiple factors contribute to observed consolidation, including increasing administrative complexity of health care delivery and mounting financial pressures regarding changing reimbursement.2–4,6 This increase in consolidation affects both patient access to care and health care costs.

Vertical integration has the potential to improve coordination of care by combining primary care services with acute care needs, and eliminating duplication of services.7,8 Improved coordination may improve the quality of care by reducing unnecessary spending,8,9 such as decreasing hospital readmission rates.10 In addition, physician hospital consolidation has the potential to increase patient access to providers, especially for low income Medicaid populations.8,11,12 Large health systems have been found to accept a wider variety of insurance plans, such as Medicaid, than smaller practices.11

Despite the potential for improving quality, vertical integration has been found to consistently raise health care prices.13–17 Vertical integration is associated with higher commercial health care prices and spending for outpatient care, in part due to the transition of care settings from the outpatient office to hospital outpatient department,15,18,19 as well as enhanced market power of provider organizations.16 The drivers influencing the decision of surgical practices to vertically integrate with hospital systems have not yet been explored. We aimed to identify characteristics of surgical practices that vertically integrate with larger health care systems and to explore the effect of integration on access to care for low-income populations. We hypothesized that vertical integration is associated with increased access to surgical care for Medicaid beneficiaries.

METHODS

Using survey data from SK&A, a commercial marketing database that annually compiles information on 75% of all US-office based physician practices, we examined practice and provider characteristics of 15 surgical and procedural practices (eTable 1). Information including self-reported practice specialty, patient volume, and ownership or affiliation with a hospital system is collected by SK&A via annual phone interview with physician practices, as previously validated.20 SK&A tracks physician and practice patterns, including hospital affiliations and ownerships and has been used by our group to evaluate trends in integration of medical and surgical practices.1,11,21 We obtained practice information from 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017 at the National Provider Identification (NPI) level and linked to the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) for further provider characteristics, as previously described.1

To evaluate our primary outcome, vertical integration, we created a binary variable characterizing surgical practices as 1 if owned by hospital or health care system and 0 if not, based on SK&A self-report.1 We generated 3 groups of practices: those that remained independent and never vertically integrated during our observed time period (2007 to 2017), those that were integrated with a hospital in 2007 at the start of our observation period, and those that integrated over this decade of observation. We used practice self-reported Medicaid acceptance from SK&A as a binary variable to assess access to care for low-income individuals over time. Self-reported acceptance of Medicaid and Medicare were not reported in SK&A data files in 2007 and 2017, limiting our full assessment to 2009 to 2015.

We evaluated the effects of practice and provider characteristics using SK&A self-reported sex, specialty, practice size, and patient volume, with missing sex data from SK&A retrieved from the NPPES. In order to capture provider years of experience, we used date of NPI enumeration; however, these were not mandatory until 2007, limiting our assessment of provider experience.22 We defined market characteristics, including rurality, by Metropolitan Statistical Areas, and health care use by region from the Dartmouth Atlas Project. We calculated the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure of market power, annually at the service area level. We adjusted for patient characteristics, including age structure from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program and county level markers of socioeconomic status from the US Census Bureau. We included evaluation of payer mix with time-lagged characteristics to quantify the effects of vertical integration on patient access to procedural subspecialty physician services.

We assessed differences in practice and provider characteristics across practice integration status as never integrated, always integrated, and became integrated over our study period. We used chi-square analysis for categorical variables, one-way ANOVA for continuous parametric variables, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous nonparametric variables. In our primary analyses, we estimated the relationship between practice and provider characteristics and vertical integration using multivariable logistic regression. Leveraging the panel nature of the SK&A data, all variables were measured with a 2-year lag to reflect characteristics that would precede possible integration. Variables in our models include factors under practice control, such as provider and payer characteristics, and factors outside of practice control, such as market characteristics and patient characteristics. We adjusted for year fixed effects to control for secular time trends, such as the economic recession (2007 to 2009) that may have influenced practice integration,23 and finally, hospital and state fixed effects with a binary interaction term for Medicaid expansion to control for Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states, as well as unobserved preferences across practices.

In secondary analyses, we fit multivariable logistic regression to estimate the relationship between integration and future Medicaid acceptance using the same models as our primary analysis. We used Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) to assess model fit using maximum values of the likelihood function. Standard errors were all clustered at the practice level. All analysis was completed using Stata/IC version 15.1.

RESULTS

We identified 84,795 unique surgical practices that were composed of 146,677 surgeons and represented 303,903 practice-years from 2007 to 2017. Eighteen percent of practices integrated during this time period and the majority (72.1%) remaining independent. Twelve percent of independent practices reported general surgery as their primary specialty; practices that were always consolidated were 23.7% primarily general surgery (p < 0.001). Conversely, 13% of independent practices reported plastic surgery as their primary specialty, while less than 5% of practices that became integrated during our time period were primarily plastic surgery (p < 0.001). Other significant differences between integrating and nonintegrating practices include higher proportions of female surgeons (12.1% vs 10.0%, p < 0.001), lower proportions of physicians with more than 10 years of experience (12.5% vs 22.0%, p < 0.001), and higher rates of Medicaid acceptance (81.0% vs 60.8%, p < 0.001). Table 1 shows full descriptive characteristics.

Table 1.

Practice Characteristics of Surgical Specialties in SK&A Data, 2007 to 2017

| Characteristic | Total | Never integrated | Always integrated | Become integrated | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total practice years, n (%) | 303,930 (100) | 219,252 (72.1) | 30,077 (9.9) | 54,601 (18.0) | |

| Total provider years, n (%)* | 923,172 (100) | 568,170 (61.6) | 146,673 (15.9) | 208,329 (22.6) | |

| Provider characteristic† | |||||

| Male sex, n (%) | 815,082 (88.7) | 508,587 (90.0) | 123,653 (84.7) | 182,562 (87.9) | <0.001 |

| Missing, n | 4,120 | ||||

| Provider with NPI in 2007, n (%)‡ | 232,782 (0.765) | 166,723 (0.76) | 0.732 (0.362) | 54,481 (0.801) | <0.001 |

| Practice characteristic | |||||

| General surgery primary specialty, n (%) | 46,403 (15.3) | 27,297 (12.5) | 7,121 (23.7) | 11,985 (22.0) | <0.001 |

| Multispecialty surgical practice, n (%) | 20,534 (6.8) | 10,995 (5.0) | 4,099 (13.6) | 5,440 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Plastic surgery primary specialty, n (%) | 32,584 (10.7) | 28,529 (13.0) | 1,473 (4.9) | 2,582 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Physicians/practice, median (IQR) | 1 (1,3) | 1 (1,3) | 2 (1,5) | 2 (1,4) | <0.001 |

| Patient volume/d, median (IQR) | 40 (20, 120) | 35 (20, 100) | 60 (20, 200) | 50 (20, 150) | <0.001 |

| Payer mix | |||||

| Accepts Medicare, n (%)§ | 165, 911 (90.2) | 116,529 (88.7) | 16,370 (94.0) | 33,012 (93.8) | <0.001 |

| Accepts Medicaid, n (%)§ | 124,102 (67.5) | 79, 855 (60.8) | 15,742 (90.4) | 28,505 (81.0) | <0.001 |

| Missing, n | 12,397 | ||||

| Medicaid expansion, n (%) | 193,287 (63.6) | 138,343 (63.1) | 19,682 (65.4) | 35,262 (64.6) | <0.001 |

| Market characteristic, n (%) | |||||

| Rural | 29,244 (16.1) | 19,129 (15.4) | 3,057 (14.4) | 7,058 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Market concentration | <0.001 | ||||

| Unconcentrated | 84,750 (27.9) | 65, 622 (29.9) | 6,857(22.8) | 12,271 (22.5) | |

| Moderately concentrated | 44, 501 (14.9) | 34,233 (15.6) | 4,078 (13.6) | 6,908 (12.7) | |

| Highly concentrated | 173, 961 (57.3) | 119,397 (54.5) | 19,142 (63.6) | 35,422 (64.9) | |

| Medicare use, mean (SD) | |||||

| Surgical discharges/1,000 enrollees | 82.93 (14.0) | 83.25 (14.1) | 79.88 (13.4) | 83.23 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Surgical inpatient days/enrollees | 0.503 (0.11) | 0.508 (0.11) | 0.475 (0.11) | 0.496 (0.11) | <0.001 |

| Patient characteristic | |||||

| Percent uninsured, mean (SD) | 0.188 (0.073) | 0.193 (0.074) | 0.169 (0.070) | 0.176 (0.071) | <0.001 |

| Missing, n | 52,820 | ||||

From SK&A provider files.

From SK&A provider files and National Plan & Provider Enumeration System (NPPES).

Provider experience obtained from provider NPI enumeration date from the NPPES. NPI numbers were not required before 2007, so we report percentage of providers with an NPI enumeration date in or before 2007.

Excludes 2007, 2017 data.

IQR, interquartile range; NPI, National Provider Identification number.

In our primary analysis, general surgery practices (odds ratio [OR] 1.68, 95% CI 1.58 to 1.78), multispecialty surgery practices (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.77 to 2.07), and practices that accepted Medicaid (OR 4.20, 95% CI 3.93 to 4.49) were more likely to integrate over time; practices with a higher proportion of male providers (OR 0.816, 95% CI [0.75 to 0.89]) and primarily plastic surgery practices (OR 0.615, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.69) were less likely to integrate over time (Table 2). Adjusting for factors outside of the practice’s short-term control, practices in highly concentrated markets (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.27) were more likely to integrate, while practices in areas with higher uninsurance (OR 0.0669, 95% CI 0.0466 to 0.0962) were less likely to integrate (Table 2). When adjusting for secular trends, these provider, payer, and area-level characteristics all remained significant, with significant association of higher regional surgical volume with integration (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.35) (eTable 2). Adjusting for time-invariant differences in practices with a hospital fixed-effect, we demonstrated that high regional surgical volume is associated with integration of surgical practices (OR 16.6, 95% CI 2.27 to 122), while area uninsurance rate is negatively associated with integration (OR 0.0041, 95% CI 0.00015 to 0.11) (eTable 3), even after adjusting for Medicaid expansion with state-time policy effects (eTable 4).

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression to Determine Association of Vertical Integration of Surgical Practices with Practice and Provider Characteristics with Time-Lagged Variables from SK&A, 2005 to 2015

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Provider characteristic | |

| Male provider | 0.816* (0.747–0.891) |

| Practice characteristic | |

| General surgery as primary specialty | 1.68* (1.58–1.78) |

| Multispecialty surgical practice | 1.92* (1.77–2.07) |

| Plastic surgery as primary specialty | 0.615* (0.549–0.688) |

| Practice size | 1.03* (1.02–1.04) |

| Patient volume | 0.998* (0.997–0.999) |

| Payer mix | |

| Accept Medicaid† | 4.20* (3.93–4.49) |

| Accept Medicare† | 0.569* (0.515–0.630) |

| Market characteristic | |

| Rural | 1.04 (0.973–1.12) |

| Market concentration | 1.23* (1.20–1.27) |

| Discharge rate | 0.993* (0.990–0.996) |

| Inpatient rate | 0.686* (0.482–0.979) |

| Uninsurance rate | 0.0669* (0.0466–0.0962) |

Statistically significant.

2007 to 2013 only.

In our secondary analysis, we explored the relationship between vertical integration and future acceptance of Medicaid. We found that practices were more likely to accept Medicaid patients after vertical integration, even after controlling for past Medicaid acceptance, as well as other practice and market characteristics, and time trends (OR 2.61, 95% CI 2.40 to 2.83) (Table 3). We applied our hospital fixed-effects model to assess for unobserved time-invariant differences and found that vertical integration was still significantly associated with practice future acceptance of Medicaid (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.20) (eTable 5).

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression to Determine Association of Practice Medicaid Acceptance and Vertical Integration and Other Practice Characteristics with Time-Lagged Variables from SK&A, 2007 to 2017

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Provider characteristic | |

| Male provider | 0.965 (0.868–1.073) |

| Practice characteristic | |

| Vertical integration | 2.61* (2.40–2.83) |

| General surgery as primary specialty | 1.49* (1.37–1.61) |

| Multispecialty surgical practice | 0.950 (0.868–1.07) |

| Plastic surgery as primary specialty | 0.365* (0.335–0.398) |

| Practice size | 1.05* (1.03–1.07) |

| Patient volume | 1.00 (0.999–1.00) |

| Payer mix | |

| Past Medicaid acceptance† | 64.4* (60.6–68.4) |

| Past Medicare acceptance† | 0.393* (0.361–0.428) |

| Market characteristic | |

| Rural | 1.50* (1.38–1.62) |

| Market concentration | 1.17* (1.13–1.21) |

| Discharge rate | 1.01* (1.01–1.02) |

| Inpatient rate | 0.298* (0.205–0.432) |

| Uninsurance rate | 0.288* (0.189–0.440) |

Statistically significant.

2009 to 2015 only.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous work, we demonstrated an 18% increase in vertical integration across all surgical subspecialties over a 10-year period. Specifically, we found that general surgery practices, multispecialty surgical practices, and those with a greater proportion of female surgeons were more likely to vertically integrate over the observation period. Our study identified regional surgical volume to be a strong, time-invariant driver of vertical integration of surgical practices, with county uninsurance rates negatively associated with vertical integration, even after adjusting for state Medicaid expansion. These associations could result from either hospital systems attempting to acquire practices with higher surgical volume or surgical practices in higher volume areas securing privileges at local hospitals. Practices that accept Medicaid were more likely to integrate and similarly, surgical practices that integrate were more likely to accept Medicaid in the future, which improves access to surgical specialty services for low-income populations.

Other studies have similarly reported that practices with younger surgeons and female surgeons were more likely to be employed by hospital systems or large physician groups.2,24,25 Previous work by our group also identified high rates of vertical integration in multispecialty and general surgical practices.1 Reasons for integration include provider lifestyle preference and increasing specialization of practice, as well as increasing financial and administrative complexity of care delivery.2–4,6,26 The drive toward vertical integration is also influenced by the current landscape shift to value-based health care delivery. Accountable care organizations and bundled payments incentivize the formation of vertically integrated organizations more suited to coordinate care and reap the financial benefits.3,6,27 Other research, however, has demonstrated that vertical integration preceded initiation of alternative payment models.28

The increased likelihood of physician practices to accept Medicaid after vertical integration has been previously demonstrated.8,11,12 Hospitals that consolidate are more likely to be large or major teaching hospitals and less likely to be for-profit institutions,29 and large hospital systems are required to treat all acute patients due to regulations such as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986. Hospital-affiliated physicians are more likely to accept referrals from community health centers serving low-income patients than independent providers.12,30 The challenges of uncompensated care, especially in emergency acute care surgery, may lead surgical practices with hospital affiliations to accept Medicaid services,31,32 while predominantly elective practices, such as plastic surgery, have more selection over their patient population.

With vertical integration, however, this increased access to surgical specialists for Medicaid populations is accompanied by higher costs. Vertical integration has consistently been associated with higher prices of care delivery due to large, integrated health care systems exploiting their greater market power.13,14,16,17 These increased prices after vertical integration are not associated with significant improvement in quality metrics, such as hospital length of stay or patient satisfaction,29,33 leading some to argue that vertical integration threatens the affordability of health services.27 The high prices set by integrated health systems will prevent sustainable access to surgical specialists for low-income populations. Despite practice acceptance of Medicaid, the financial vulnerability of many state Medicaid systems may limit low-income populations from accessing nonacute surgical care in these large networks.

Our study has several limitations. First, our definition of vertical integration is a binary characterization that relies on self-reported practice financial affiliation, not accounting for the varying degrees of integration that can exist between physician practices and hospital systems.26,27 Similarly, our definition did not assess for practices that “de-integrated” over time, although these rates are significantly lower than integration rates.34 The SK&A survey also did not collect Medicaid acceptance data in 2007 or 2017, limiting our analysis of these time periods. Due to these omitted variables being not missing at random, we could not apply imputation to address the missingness; however, our analysis yielded robust findings despite a limited time period. We were also unable to assess the influence of provider experience on integration trends and Medicaid acceptance given the lack of reliable data in both the SK&A and NPPES, but our fixed effects analyses adjusted for such observed provider characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

As more procedural practices integrate with large health systems, it is important to understand the effects of vertical integration on access to care. An increase in value-based health care with alternative bundled payment models in procedural practices may incentivize practices in high volume surgical areas to integrate with hospital systems. The potential benefit of increased access for low-income beneficiaries with vertical integration of surgical practices must be balanced with the potential for increased health care prices. Policymakers must consider the sustainability of both access and affordability of these integrated health care systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this study: Dr Haddad is supported by NIH grant #T32 CA106183-15. Dr Nikpay is supported by NIH grant #CA106183-15. Dr Resnick is supported by American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant #MSRG-15-103-01-CHPHS and American Urological Association/Urology Care Foundation Rising Stars in Urology Research Program.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- NPI

National Provider Identification

- NPPES

National Plan and Provider Enumeration System

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Presented at the American College of Surgeons 105th Annual Clinical Congress, Scientific Forum, San Francisco, CA, October 2019.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclosures outside the scope of this work: Dr Resnick is a consultant to Embold Health and Photocure and holds stock in Embold Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nikpay SS, Richards MR, Penson D. Hospital-Physician Consolidation Accelerated In The Past Decade In Cardiology, Oncology. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charles AG, Ortiz-Pujols S, Ricketts T, et al. The employed surgeon: a changing professional paradigm. JAMA Surg 2013;148:323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napolitano LM. Surgeons as hospital employees. Good, bad, or indifferent? JAMA Surg 2013;148:329–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Updated Physician Practice Acquision Study: National and Regional Changes in Physician Employment: 2012–2018. Available at: 2019. http://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/021919-Avalere-PAI-Physician-EmploymentTrends-Study-2018-Update.pdf?ver=2019-02-19-162735-117. Accessed May 8, 2019.

- 5.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Royalty AB, Levin Z. Physician practice competition and prices paid by private insurers for office visits. JAMA 2014;312:1653–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zenilman ME, Freischlag JA. The changing paradigm in surgery is system integration: How do we respond? Am J Surg 2018;216:2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih A, Davis K, Schoenbaum S, et al. Organizing the US Health Care Delivery System for High Performance. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller ME. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system 2014. Available at: http://67.59.137.244/documents/20140618_WandM_June2014report_testimony.pdf, Accessed November 12, 2019.

- 9.Enthoven AC. Integrated delivery systems: the cure for fragmentation. Am J Managed Care 2009;15:S284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes S, Fernandes OB, Marques AP, et al. Can vertical integration reduce hospital readmissions? A difference-indifferences approach. Med Care 2017;55:506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards MR, Nikpay SS, Graves JA. The growing integration of physician practices: with a Medicaid side effect. Med Care 2016;54:714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berenson RA. A physician’s perspective on vertical integration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1585–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33: 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neprash HT, Chernew ME, Hicks AL, et al. Association of financial integration between physicians and hospitals with commercial health care prices. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175: 1932–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch TG, Wendling BW, Wilson NE. How vertical integration affects the quantity and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries. J Health Econ 2017;52:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capps C, Dranove D, Ody C. The effect of hospital acquisitions of physician practices on prices and spending. J Health Econ 2018;59:139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Delivery system integration and health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173: 1447–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cassidy A Health policy brief: site neutral payments. Health Affairs 2014;24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reschovsky JD, White C. Location, Location, Location: Hospital Outpatient Prices Much Higher than Community Settings for Identical Services. Washington, DC: National Institute for Health Care Reform; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Devlin AM, Kessler DP. Hospital ownership of physicians: hospital versus physician perspectives. Med Care Res Rev 2018;75:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards MR, Smith CT, Graves AJ, et al. Physician competition in the era of accountable care organizations. Health Serv Res 2018;53:1272–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HIPAA administrative simplification: standard unique health identifier for health care providers. Final rule. Fed Regist 2004;69:3433–3468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Thomas SB. Using quantile regression to examine health care expenditures during the great recession. Health Serv Res 2014;49:705–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kash B, Tan D. Physician group practice trends: a comprehensive review. J Hosp Med Manag 2016;1:8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocher R, Sahni NR. Hospitals’ race to employ physicians d the logic behind a money-losing proposition. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1790–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satiani B, Vaccaro P. A critical appraisal of physician-hospital integration models. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Post B, Buchmueller T, Ryan AM. Vertical integration of hospitals and physicians: economic theory and empirical evidence on spending and quality. Med Care Res Rev 2018;75: 399–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neprash HT, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Little evidence exists to support the expectation that providers would consolidate to enter new payment models. Health Aff 2017;36: 346–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott KW, Orav EJ, Cutler DM, Jha AK. Changes in hospitalephysician affiliations in U.S. hospitals and their effect on quality of care. Ann Int Med 2017;166:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enhancing the capacity of community health centers to achieve high performance: Findings from the 2009 Commonwealth Fund National Survey of Federally Qualified Health Centers. Available at: 2010. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2010/may/enhancing-capacitycommunity-health-centers-achieve-high. Accessed June 18, 2019.

- 31.Maa J, Carter JT, Gosnell JE, et al. The surgical hospitalist: a new model for emergency surgical care. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 205:704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sweeting RS, Carter JE, Meyer AA, Rich PB. The price of acute care surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74: 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Short MN, Ho V. Weighing the effects of vertical integration versus market concentration on hospital quality. Med Care Res Rev 2019:1077558719828938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Short M, Ho V, McCracken A. The integration and deintegration of physicians and hospitals over time. Houston: James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.